Abstract

Recent studies have compiled all records of new fish species discovered between 2017 and 2025 in two regions of Spanish Mediterranean waters: the Strait of Gibraltar–Alboran Sea (ESAL) and the Levantine–Balearic Sea (LEBA). These studies compared the mean temperatures and thermal ranges (minimum and maximum temperatures) at which these newly recorded species lived in their original distribution zones with the preferred temperature ranges of native species present in Spanish Mediterranean waters prior to 2017. In order to characterize the thermal preferences of Mediterranean native species, previous works used the temperature of waters corresponding to the complete geographical distribution of such species. This comparison identified a tropicalization process in the ESAL region, but not in the LEBA. To further explore and refine these findings, the present work provides a new estimation of the thermal ranges of Mediterranean species occurring in these two regions. This estimation is based on existing temperature climatologies from both international and local databases. However, in the present work, we only use the temperature of waters within the ESAL and LEBA regions, instead of using those of the complete geographical distribution of Mediterranean native fish species. This new comparison offers a more accurate characterization of the thermal conditions under which Mediterranean species live. This updated comparison reveals a surprising result: the Mediterranean species recorded in the LEBA up to 2017 exhibit higher thermal preferences than those reported after this year, a difference that exceeds what had been observed in previous analyses. In contrast, in the ESAL region, the newly recorded species still display higher thermal affinities than native ones, although the differences are smaller than those found in earlier studies. A more detailed analysis, considering both the depth ranges and geographical origins of the new species, reveals a complex scenario. While some species are indeed of tropical origin, contributing to the ongoing tropicalization of the Western Mediterranean, others originate from more northern latitudes or even Mediterranean regions. This suggests that the arrival of invasive species in this part of the Mediterranean is not solely, (or even primarily) driven by the intense warming of the basin, but also by other anthropogenic factors.

1. Introduction

Global warming is widely recognized as a primary threat to contemporary marine ecosystems [1,2,3]. A significant consequence of ocean warming is the tropicalization of temperate seas [4,5], characterized by the poleward expansion of tropical species. This process involves the extension of a species’ cold-edge (leading) range limit and the contraction of its warm-edge (trailing) limit. Tropicalization can profoundly alter marine ecosystems through novel biotic interactions between non-indigenous and native species. These interactions can lead to changes in community composition (taxocoenosis), potentially resulting in biodiversity loss, community collapse, and local extinctions [6,7].

The Mediterranean Sea is particularly vulnerable to global warming. Despite its small size (0.32% of global ocean volume), it harbors between 4% and 18% of the world’s known macroscopic marine species, with a high degree of endemism [8,9,10]. Furthermore, this region is warming at an accelerated rate, with sea surface temperature trends reported to be double or triple the global average [11]. This intense warming, coupled with an increase in the frequency, intensity, and duration of Marine Heatwaves (MHWs) in recent decades [12], has been linked to several documented Massive Mortality Events (MMEs) within the basin [10,13].

As in other oceans, ocean warming is driving a shift in the geographical distribution of marine species in the Mediterranean and the arrival of exotic species [8,9,14,15,16], inducing changes in community structure mediated by biotic interactions [17]. However, the analysis of this process in the Mediterranean is complex due to several unique factors.

First, alongside the northward expansion of thermophilic species, other anthropogenic vectors, such as ballast water discharge and hull biofouling from cargo ships, contribute to the arrival of non-indigenous species, some of tropical origin. Besides this, a pivotal event in the Mediterranean’s biogeography was the opening of the Suez Canal in the nineteenth century, which introduced hundreds of tropical species from the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean (a process known as Lessepsian migration). This is arguably one of the most significant biogeographic shifts in the modern world [18].

Second, the semi-enclosed nature of the Mediterranean imposes a physical limit on the northward expansion of cold-water species. Consequently, these species face a heightened risk of local extinction if unable to adapt to the shifting climate niche [19].

Third, this semi-enclosed geography, combined with the presence of a 2000 km-long upwelling system along the northwestern African shelf, acts as a natural barrier that impedes the arrival of tropical African species [20]. The confluence of intense warming, limited scope for latitudinal range shifts, and low connectivity raises concerns about a potential diversity collapse in the region [20,21]. Supporting this, Chust et al. [22] analyzed the Community Temperature Index (CTI) across European waters and found a significant increase in the North Eastern Atlantic and Baltic Sea, indicating tropicalization. In contrast, the CTI increase in the Mediterranean was not significant, likely due to its enclosed nature and low connectivity. Similarly, Bianchi & Morri [9] concluded that Mediterranean ecosystems were not acquiring a tropical physiognomy, at least in terms of the proliferation of bio-constructor organisms.

Despite these specific findings, there is a consensus on the need for further research, including coordinated efforts to monitor marine species shifts [23] and MMEs [10].

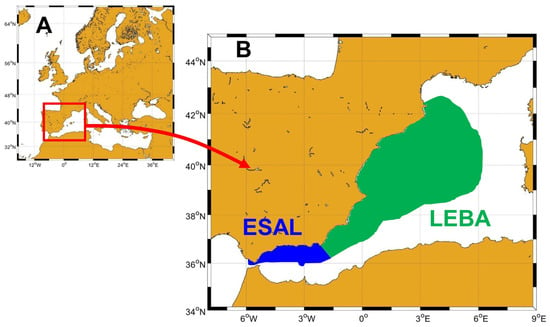

Focusing on the Spanish Mediterranean waters (Figure 1), Torreblanca and Báez [24] (hereafter T&B25) recently analyzed and compared the thermal preferences of species newly recorded since 2017 with those of native species listed by [25] up to that year. The present study builds upon the work of T&B25, aiming to refine their methodology to better determine the extent to which the Spanish Mediterranean is undergoing tropicalization and the role of water warming in driving this process.

Figure 1.

(A) Situation of the Mediterranean Sea. The red rectangle shows the westernmost sector of the Mediterranean Sea, where the Spanish waters are located. (B) Location of the Strait–Alboran Sea (ESAL) and Levantine–Balearic (LEBA) demarcations within the Spanish Exclusive Economic Zone in the Western Mediterranean.

Our methodological improvements are twofold. First, T&B25 assessed the thermophilic character of new species by comparing their preferred temperature ranges to those of native Mediterranean species. However, for native species, they used temperature ranges corresponding to the species’ full global distribution. Given that many Mediterranean fishes are cosmopolitan, these global ranges may not accurately reflect the thermal conditions they experience within the basin. Second, T&B25′s analysis did not account for species’ vertical (depth-related) distribution or their geographical origin.

In this study, we estimate updated temperature ranges for native Mediterranean fish species using a comprehensive temperature database from the Met Office Hadley Centre and compare these results with those obtained by T&B25. Additionally, we examine the influence of species-specific depth ranges and the geographical origin of these species on our analysis.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Mediterranean Species and New Records

Báez et al. [25] (hereafter B19) produced a comprehensive inventory of marine fish species within the Spanish Exclusive Economic Zone, commissioned by the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food. Building on this work, T&B25 [24] examined species inhabiting two specific demarcations: the Strait of Gibraltar and Alboran Sea (ESAL) and the Levantine–Balearic (LEBA) regions (see Figure 1 for their positions within the Western Mediterranean). Their study characterized the thermal preferences of native Mediterranean species, expanding the original dataset by incorporating minimum and maximum temperatures derived from each species’ full geographic and depth distributions, together with their preferred mean temperature. This thermal information, obtained from FishBase (https://www.fishbase.se/search.php, accessed on 2 June 2025) and published literature, was provided as an Excel file in the Supplementary Materials of that work and serves as the foundation of the present study.

In addition, T&B25 [24] reported an updated list of new marine fish species recorded in Spanish Mediterranean waters since 2017, which had not been included in the 2019 inventory. For these new records, they also provided the associated minimum, maximum, and preferred mean temperatures.

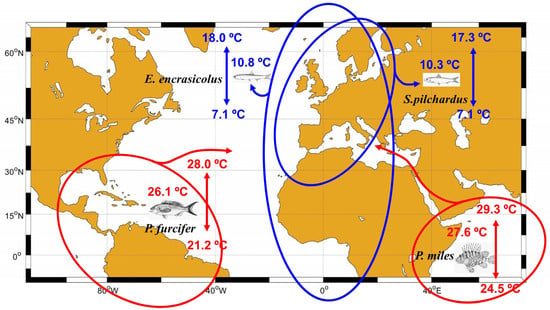

Figure 2 illustrates the methodology followed in these previous works for the sake of completeness and for comparison with the present study. Blue lines encircle the geographical distribution for two of the native fish species present in the ESAL and LEBA regions (Sardina pilchardus and Engraulis encrasicolus) and blue figures are the temperature range and preferred mean temperatures for these two species. These data were obtained from Supplementary Material in T&B25 [24] and have been included too in an updated Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials of the present work. The red lines and red figures show the geographical distribution, temperature range, and preferred mean temperatures for two of the new records of fish species (Paranthias furcifer and Pterois miles) found in the ESAL region after 2017 (see Table 1, adapted from Table 1 in T&B25). These authors averaged the preferred mean temperatures for all the native species and for the new records for each of the two Spanish demarcations. It is important to note that temperature ranges and preferred mean temperatures were analyzed for 461 native species and 10 new records in the ESAL region, and for 495 native species and 15 new ones in the LEBA region. However, and just in order to illustrate the methodology, Figure 2 shows the case of just two species. If S. pilchardus and E. encrasicolus were the only native species present in the ESAL up to 2017, and both P. furcifer and P. miles were the only new records found in this region after 2017, we would conclude that the preferred mean temperature for native species was (10.8 + 10.3)/2 = 10.6 °C, whereas the preferred mean temperature of the new species arriving to this region was (26.1 +27.6)/2 = 26.9 °C. We emphasize that this analysis was carried out for all the native and new records found in each region. Furthermore, it was checked whether or not the set of preferred mean temperatures for native and alien species followed a normal distribution. Then, both distributions (temperatures for native species and new records) were compared by means of a Mann-Whitney test. This test revealed that, in the case of the ESAL region, preferred temperatures for new species were higher than those corresponding to native ones.

Figure 2.

Example of the methodology followed in T&B25 [24]. Blue lines encircle the geographical distribution of two native fish species of the ESAL and LEBA regions. Red lines show the geographical distribution of two new species found in the ESAL region after 2017. Blue and red figures show the temperature ranges and preferred mean temperatures for these species in their complete geographical distribution.

Table 1.

Adapted from T&B25. Minimum, maximum and mean temperature for the fish species recorded in the ESAL and LEBA regions since 2017. The minimum and maximum depth ranges preferred by these species have been added from FishBase and the existent literature.

2.2. New Approach and Temperature Data

The methodology described above allows a comparison of thermal affinities of allocthonous species with those of Mediterranean native species, considering those temperatures to which each species is adapted throughout the world ocean. However, some temperatures, as those shown in the example of Figure 2, are not found in the Mediterranean Sea, where minimum temperatures at the bottom waters can only be a few tenths below 13 °C [26]. The temperatures considered in T&B25 [24] for characterizing the thermal affinity of Mediterranean species were sometimes as low as 2.8 °C, very far from the coldest Mediterranean waters (around 13 °C).

The new approach in the present work is to repeat the analysis carried out by T&B25, but comparing the temperature ranges and mean temperature preferences of the new species with the mean temperatures and temperature ranges of the Mediterranean waters inhabited by species present in the ESAL and LEBA regions.

In order to determine such thermal preferences, we checked the preferred depth ranges for the native species in the ESAL and LEBA demarcations. For allowing comparison with previous works and for consistency, we used FishBase for obtaining this information. These depth ranges have been included in Table S1 in Supplementary Material as columns named Dmin and Dmax for the minimum and maximum depth levels, completing T&B25′s table. Once we know the depth range where a certain species lives, we have to determine the temperatures prevailing at such depth levels within the ESAL and LEBA regions.

For this purpose, temperature profiles were obtained from the Met Office Hadley Centre EN4 dataset (https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/en4/, accessed on 2 June 2025; [27]). We used Version 4.2.2 of the objective analysis product, which includes the g10 correction [28,29]. This dataset provides monthly vertical temperature and salinity profiles on a 1° × 1° grid (only temperature data were used in this work).

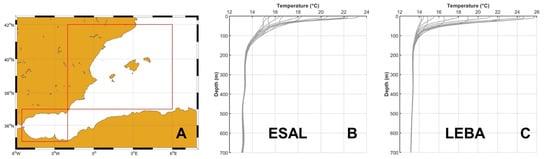

For the ESAL region, we extracted all available monthly temperature profiles from January 1993 to December 2024 within the geographical bounds 5.5° W–2° E and 35° N–37° N. Similarly, for the LEBA region, we compiled all monthly profiles for the same period within the area defined by 2° W–6° E and 37° N–42° N (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) Red rectangles show the limits of the two regions used for collecting temperature profiles for the ESAL and LEBA regions. (B) shows the 12 average temperature profiles corresponding to ESAL and (C) is the same for the LEBA region.

To characterize the mean thermal structure of each region across depth, we constructed 12 climatological profiles, one for each month of the year. These were obtained by averaging all available profiles corresponding to each calendar month within each region (i.e., all January profiles, all February profiles, etc.). The resulting climatological profiles for the ESAL and LEBA regions are shown in Figure 3B,C, respectively. In addition, we calculated the standard deviation at each depth level for every month, generating 12 standard deviation profiles per region to describe inter-annual variability. Monthly mean temperature (mean) and standard deviations (STD) profiles are provided for ESAL and LEBA in Tables S2 and S3, respectively, in the Supplementary Materials.

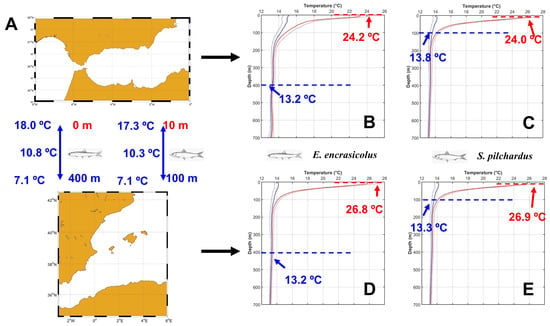

One example will illustrate the way in which we proceeded to determine the new temperature preferences for native species. For instance, in the case of E. encrasicolus, this species dwells between 0 and 400 m (see Dmin and Dmax in Table S1 and Figure 4A). The maximum temperature was reached in August, in both the ESAL and LEBA regions. In the ESAL, this temperature was 23.4 °C. The standard deviation for August at the sea surface of the ESAL region was 1 °C (see Tables S2 and S3). Temperatures in August, as in any other month, are very likely to oscillate around the mean value. Therefore, we considered that temperatures as high as the mean value plus one standard deviation were very likely to be observed at the ESAL sea surface and this is the maximum temperature value corresponding to E. encrasicolus in the ESAL (23.2 °C + 1 °C; Figure 4B). The lowest temperatures where this species would live correspond to its maximum depth level. At 400 m, the temperature is quite homogeneous all the year round in the Mediterranean Sea (see Figure 3B,C). However, we determined the minimum average temperature, which was observed in July. This temperature was 13.27 °C. We considered that the yearly minimum minus the standard deviation of this depth and month was the lower temperature limit for this species in this region (13.27–0.11 °C; Figure 4B). For comparison of the methodology used in T&B and the one proposed in this work, Figure 4 illustrates this procedure for the same two species considered in Figure 2.

Figure 4.

(A) ESAL region (upper panel) and LEBA region (lower panel). Depth ranges for S. pilchardus and E. encrasicolus from FishBase have been included for comparison with Figure 2. (B,C) show the temperature ranges corresponding to the depth ranges of E. encrasicolus and S. pilchardus in the ESAL region, respectively. (D,E) show the temperature ranges for the same species in the LEBA region. Red colors are used for the upper ranges of temperature and depth and blue colors for the lower range.

For the sake of clarity, and in order to illustrate the procedure, Figure 4 only shows the case of two Mediterranean native species. However, once again, we have to note that this methodology was applied to all the species present in the ESAL and LEBA demarcations. Tables S4 and S5 in Supplementary Materials show the minimum, maximum and preferred mean temperatures for each of the 461 fish species present in the ESAL region and the 495 species present in the LEBA, respectively. These tables include the temperature values previously used and those obtained in the present study from the Met Office climatology.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

After the compilation of data from T&B25 and the estimation of climatological temperature profiles for the Spanish Mediterranean waters, we had three sets of minimum temperatures for each of the two regions (ESAL and LEBA). These sets corresponded to the minimum temperatures of the newly recorded species, the native species’ minimum temperatures calculated according to the T&B25 method (using the complete geographical distribution of such species), and the minimum temperatures calculated by means of the new method proposed in this work and based on the Mediterranean temperature climatology. We also have for each region three sets of maximum temperatures (new and native species) and three sets of mean temperatures. We checked the normality of these distributions or data sets by means of Lilliefors tests and compared the distributions of new records and native species as well as the distributions of Mediterranean temperatures calculated by means of different methodologies. We used Mann-Whitney tests for these comparisons.

2.4. Comparison by Depth Ranges

In order to compare the thermal affinities of species dwelling at the same depth levels, we searched for the depth range of each of the new species recorded in the ESAL and LEBA regions. This information is provided in Table 1, completing the corresponding table in T&B25.

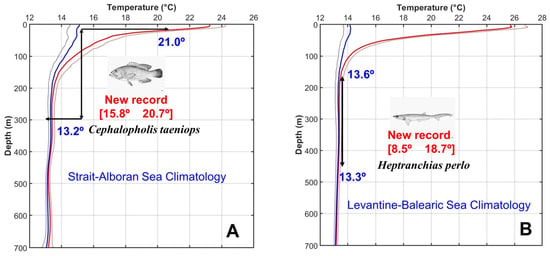

For comparison of the temperature of the original habitat of these species, and the temperatures they would find in the Mediterranean Sea (in case they do not experience a vertical migration), we compared the temperature values of these species with those corresponding to the same depth level both in the ESAL and LEBA regions (see Section 3). This methodology is illustrated by Figure 5.

Figure 5.

(A) Continuous red line and dashed red line show the maximum temperature and maximum temperature plus one standard deviation for the ESAL region. Continuous blue line and dashed blue line correspond to the minimum temperature and minimum minus one standard deviation. Red figures are the minimum and maximum temperature limits for C. taeniops, which was found in the ESAL region after 2017. Black arrows show the original depth range for this species and blue figures correspond to the minimum and maximum temperatures that this species would find at the same depth levels at the ESAL region. (B) is the same for the LEBA region and the species H. perlo, found in this region after 2017.

3. Results

3.1. Temperature Comparison

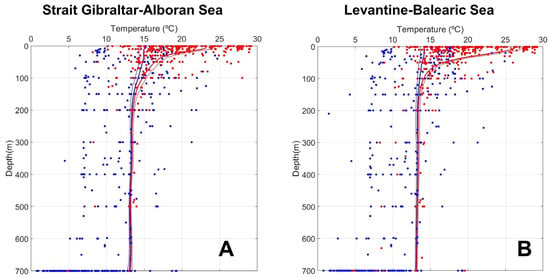

Our results show that the temperature of waters where fish species live in the Spanish Mediterranean waters and the temperature of those waters where these same species inhabit in their complete geographical distribution are quite different. Figure 6 shows the minimum (continuous blue line) and maximum (continuous red line) temperatures for each depth level throughout the seasonal cycle in the ESAL (Figure 6A) and LEBA (Figure 6B) regions. In order to take into account the inter-annual variability, blue dashed and red dashed lines show such minimum and maximum temperatures, minus and plus one standard deviation, respectively. Blue and red dots are the minimum and maximum temperatures corresponding to each of the native fish species in the ESAL (Figure 6A) and LEBA (Figure 6B) regions and calculated from FishBase, considering the broader geographical distribution of such species used in T&B25. It should be taken into account that the temperature ranges compiled from FishBase and presented in Table S1 in Supplementary Materials correspond to each species. In order to associate a depth level to these temperature values, we considered that the minimum temperature where each species lives corresponds to its maximum depth (Dmax in Table S1) and the maximum temperature corresponds to the minimum depth (Dmin in Table S1). Figure 6 shows that if we consider the temperature range of fish species in their complete geographical distribution, these values are frequently out of the real temperatures that these species find in the Spanish Mediterranean waters, especially when minimum temperatures are considered.

Figure 6.

Minimum temperatures (continuous blue line) and maximum temperatures (continuous red line) throughout the seasonal cycle for each depth level in the ESAL (A) and LEBA (B) regions estimated from Metofice EN4 gridded climatology. Dashed blue and red lines show the minimum and maximum temperatures minus and plus one standard deviation. Blue and red dots are the minimum and maximum temperatures for the species in both regions, according to FishBase and their complete geographical distribution.

In the ESAL region, Lilliefors tests allowed us to reject the normality of minimum, maximum and mean temperatures estimated from the FishBase data and from the Mediterranean waters (using Met Office database) at the 0.05 significance level. The normality of the mean and maximum temperatures of new species was also rejected at the 0.05 and 0.1 significance levels, respectively. In the case of the LEBA region, the normality was rejected at the 0.05 significance level for the minimum, maximum and mean temperatures estimated from FishBase and the Met Office, and for the minimum temperature of new species at the 0.1 significance level, supporting the use of non-parametric tests for the comparison of the different temperature distributions.

Mann-Whitney tests confirmed the visual results of Figure 6. In the case of both the ESAL and LEBA regions, minimum, maximum and mean temperatures estimated from FishBase (broader geographical distribution) and from the Met Office climatology were statistically different, supporting the use of temperatures corresponding to the Mediterranean waters for defining the thermal preferences of native Mediterranean species.

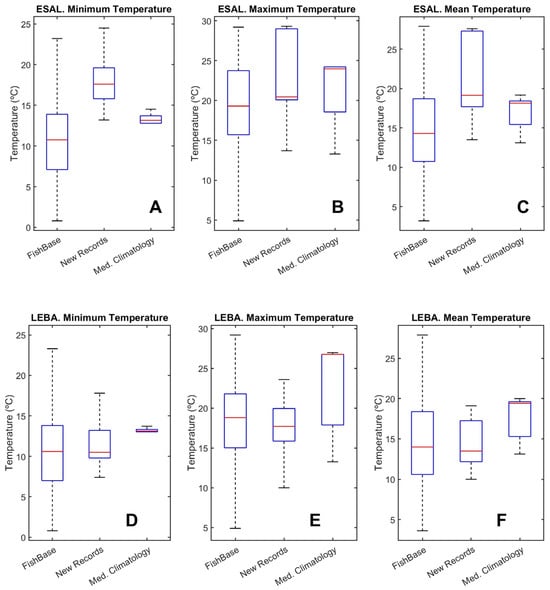

Figure 7A–C show a box-whisker plot for the minimum, maximum and mean temperatures in the ESAL regions. For each figure, the three boxes correspond, from left to right, to native species (using FishBase), new species (from FishBase), and native species (using the Mediterranean climatology from Met Office EN4). Figure 7D–F show the same results for the LEBA region.

Figure 7.

Box-Whisker plots for minimum, maximum and preferred mean temperatures for the ESAL region (A–C) and for the LEBA one (D–F). Within each panel, the left box corresponds to the FishBase temperatures for native species, the middle box is for the new species temperatures from FishBase and the right box is for the native species using the Mediterranean temperatures from Met Office climatology.

The minimum, maximum and mean temperatures of the new records were higher than those of the native species in the ESAL region, but these differences were lower when the Met Office climatology was used and this difference was not significant for the maximum temperatures. In the case of the LEBA region, temperatures were always significantly different, but the temperatures from Mediterranean waters estimated from the Met Office climatology were always higher than those corresponding to the new records (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Values of the statistic U and their p values from Mann–Whitney tests. Columns #2 and #3 correspond to ESAL region and columns #4 and #5 to the LEBA one. Rows 3, 4 and 5 correspond to the comparison of the minimum, maximum and mean temperatures of waters inhabited by new species in their original geographical distribution and the temperatures of waters inhabited by Mediterranean native species, using Mediterranean temperatures from Met Office climatology.

3.2. Dependence of Temperature Comparison on the Depth Level

When we consider the whole distribution of preferred mean temperatures and temperature ranges for both new and native species, we are grouping species with very different vertical distributions along the water column. We analyzed a very large data set in the case of ESAL and LEBA native fish species, with 461 species in the ESAL and 495 in the LEBA. Therefore, they were expected to cover the whole depth range, from surficial species to abyssal ones. On the contrary, the new records considered in this study are not numerous (10 in the ESAL and 15 in the LEBA) if compared with the number of native species. In case the depth range where these species inhabit had a bias (to surface or deep layers), this could introduce spurious results.

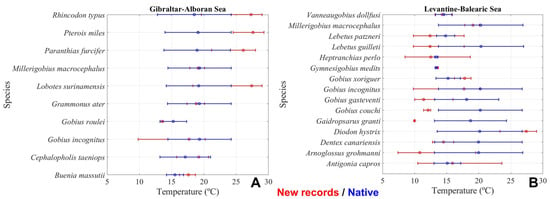

Following the methodology described in Section 2.4, we searched for the depth range occupied by new species in their original geographical region. Then, we obtained the minimum, maximum and mean temperature that these species would find in the Mediterranean waters in the case that they maintained the same vertical distribution. Figure 8 shows the minimum, maximum and mean temperature of waters to which new species are native (red symbols and bars), and those temperatures corresponding to their depth preferences in the Mediterranean regions. Figure 8A corresponds to ESAL and Figure 8B to LEBA.

Figure 8.

Red circles and bars show the mean temperatures and temperature ranges for each of the new species found in the ESAL region (A) and LEBA (B) after 2017. Blue circles and bars show the mean temperatures and temperature ranges of the Mediterranean waters ((A) for ESAL and (B) for LEBA) occupying the preferred depth levels of such newly recorded species.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

There is evidence of a tropicalization process in the Mediterranean Sea. Some species have experienced northward shifts in their geographical distribution, as documented for S. aurita in the northwestern Mediterranean [14], while other studies have reported the presence of allochthonous species on a Mediterranean-wide scale through systematic surveys among fishermen [15]. The significant concern regarding the potential changes that invasive species could induce in Mediterranean marine ecosystems has led to the creation of several monitoring projects [23], including those based on citizen science. Notable examples are the MedMIS project, focused on Marine Protected Areas [30], and “Observadores del Mar”, centered in the northwestern Mediterranean [31].

To our knowledge, the only attempt to analyze the possible tropicalization of the Strait of Gibraltar, Alboran Sea, and the Levantine–Balearic Sea (the westernmost sector of the Mediterranean) is that of T&B25 [24]. The continuous monitoring of these Spanish waters under the framework of the MEDITS and INDEMARES projects, carried out by the Instituto Español de Oceanografía (IEO), and a thorough review of the existent literature allowed B19 [25] to compile a comprehensive list of fish species for these regions. This list serves as a baseline for detecting the occurrence of allochthonous species. T&B25 [24] conducted an exhaustive search of the scientific and grey literature to compile a list of fish species newly recorded in Spanish Mediterranean waters after the baseline established by [25].

Tropicalization implies that non-indigenous species have a preference for higher temperatures compared to native ones. This can be investigated, for instance, by analyzing changes in the Community Temperature Index [22]. Calculating this index requires not only knowledge of changes in species composition and their temperature preferences, but also data on the relative abundance of native and new species. Such abundant information was unavailable to us, as it was to T&B25. Therefore, following the methodology of previous works, we limited our analysis to comparing the temperature preferences of the fish species present in the established baseline with those of the new records.

However, an analysis of 30 years of temperature data from the Met Office Hadley Center for Spanish Mediterranean waters revealed that the temperatures used by T&B25 to characterize the thermal range (minimum and maximum limits) and preferred mean temperatures in the Spanish Mediterranean did not accurately represent the actual conditions (see Figure 6). This discrepancy was consistent regardless of the temperature climatology used, as averages and standard deviations for each of the 12 calendar months from the Met Office dataset showed no significant differences when compared to a local database from the IEO’s RADMED multidisciplinary monitoring project [32].

The previous work by T&B25 already indicated that the temperature preferences of native species in the LEBA region were higher than those of non-indigenous ones. However, as Figure 6 illustrates, the temperatures used in T&B25′s study were, in many cases, considerably lower than those actually observed in the Mediterranean Sea across the complete seasonal cycle. Using the more accurate temperature values from the present work showed that the differences between native species and new records were even larger than previously estimated (i.e., native Mediterranean species preferred warmer waters). This is evidenced, for example, by the median values (red lines) of the minimum, maximum, and mean temperatures preferred by the new versus native species in the LEBA region (see Figure 7D–F).

This result could be considered counter-intuitive, primarily because the Balearic Sea is one of the regions in the western Mediterranean with the most intense warming trends reported in recent decades [11,32], and thus, where tropicalization would be more likely to occur. The explanation for this apparent contradiction lies in the methodology used. For the sake of discussion, let us focus on the preferred mean temperature (Figure 7F and the fourth column in Table 1). We considered the mean preferred temperature for the 15 species recorded in the LEBA region after 2017. To compare with T&B25, we calculated the median of these 15 values to characterize the preferred temperature of the new species and compared it to the median calculated for the 495 native species from B19′s list. However, this comparison does not account for the depth distribution or origin of the species, indicating that a more detailed analysis is warranted.

Figure 8B shows that the temperature range and mean preferred temperature of Diodon hystrix are higher than the temperatures of the Mediterranean waters at the same depth of its original distribution. According to FishBase, D. hystrix is native to the Red Sea, Indian Ocean, and Caribbean Sea. Therefore, this species contributes to the tropicalization of the LEBA region, a fact confirmed by our temperature calculations (Figure 8B). In contrast, some species in Table 1 were already present in the LEBA region, and hence, their temperature range is that of the Mediterranean Sea. They appear as new records because they were discovered by science during any of the annual MEDITS surveys carried out after 2017 (e.g., Gymnesigobius medits, [33]), or simply because they had not been previously identified, as could be the case of Gobius incognitus [34] or Gobius xoriguer [35].

In some cases, species found in the LEBA region have an original distribution in seas colder than the Mediterranean, such as Gobius couchi, native to the Northern Sea [36]. In this case, the temperature range of this new species is much lower than that of the Mediterranean waters at its corresponding depth range (see Figure 8B).

These results underscore a well-known fact, as mentioned in the introduction: the arrival of allochthonous species is driven not only by global warming and the poleward migration of thermophilic species but also by other anthropogenic factors. This is likely the case for most species analyzed in the LEBA region, where, based on the available data, a clear tropicalization of its fish communities cannot be asserted. Nevertheless, the importance of the arrival of new species to the LEBA region should not be underestimated. Whether they originate from colder or warmer waters, alien species can introduce new biotic interactions with native fauna and have unpredictable impacts on ecosystem functioning.

In the ESAL region, T&B25′s comparison of mean preferred temperatures for native species and new records suggested a trend towards tropicalization (see left and central boxes in Figure 7C). Using the new temperature dataset confirmed that the mean temperatures preferred by species found in the ESAL after 2017 were higher than those of the native Mediterranean species, although the differences were substantially reduced (see right box in Figure 7C). The same result was obtained for minimum temperatures. Conversely, the median calculated for the upper thermal limit in the ESAL region was higher for native species than for the new ones. Despite the reduced temperature differences when using appropriate regional data, a certain degree of tropicalization in this region can still be considered.

The Alboran Sea and the Strait of Gibraltar are warming at a slower rate than other parts of the Spanish Mediterranean [11,12,32]. It might therefore seem surprising that the ESAL region appears to be undergoing tropicalization while the LEBA region, with a more intense warming, is not (comparing temperature preferences estimated from the Mediterranean climatology with temperature preferences of new records estimated from FishBase). However, it is important to note that warming trends in the ESAL region, although lower, still exceed 2 °C per century, which is above the global ocean average [11,12,32]. Once again, the explanation lies in the detailed composition of the newly recorded fish species in the ESAL region.

Figure 8A shows that the mean temperature and thermal range of the waters preferred by four of the new species in the ESAL region are clearly above the temperatures of the Mediterranean waters at their respective depth ranges. These species are: Lobotes surinamensis, Paranthias furcifer, Pterois miles, and Rhincodon typus (Figure 8A and Table 1, [37,38]). P. miles is originally from the Red Sea and Indian Ocean, P. furcifer is distributed in African and American tropical waters (including the Caribbean Sea), L. surinamensis is found in tropical and subtropical waters worldwide, and R. typus is a warm-water species distributed globally in tropical waters. The influence of these species on the calculation of the median of the temperature distributions is responsible for the higher values compared to those of native species. In contrast, other species, such as M. microcephalus [39], B. massutti [40], and G. incognitus [34], are originally from the Mediterranean, and G. roulei is native to the North Atlantic and does not contribute to the tropicalization of the ESAL region.

The results discussed above, along with the species lists compiled by T&B25 [24] and B19 [25], confirm the presence of fish species of tropical origin in the Spanish Mediterranean. However, the present analysis highlights the critical importance of accurate environmental monitoring to properly characterize marine habitats. The calculation of average temperature ranges and preferred mean temperatures suggests that the tropicalization of the Levantine and Balearic Sea in the Spanish Mediterranean is not clearly evident. While some species of tropical origin contribute to the tropicalization of the Strait and Alboran Sea, the results are less conclusive when the temperatures of all new species are considered. The primary reason for this lack of conclusive evidence is that many new records in both regions correspond either to native Mediterranean species not previously identified or to the introduction of species from cold waters. This reflects the complexity of species introduction, a process involving not only the tropicalization of temperate waters due to global warming but also introductions via other means, such as ballast water in cargo ships, aquaculture, etc. [8,9].

A final question that cannot be resolved with the available data is whether these new species will naturalize and establish stable populations or if the records are merely occasional or sporadic, as might be the case for R. typus [41]. Monitoring programs and international networks and projects dedicated to studying fish stocks and detecting exotic species are of paramount importance for addressing these unresolved questions [15,25,30,31]. This objective could also be pursued by means of reproduction studies or ichthyoplanktonic surveys oriented toward the detection of eggs and/or larvae of allochthonous species, which would support the possibility of their naturalization in the Spanish Mediterranean waters.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jmse13122325/s1. Table S1: List of native species in the ESAL and LEBA regions updated after T&B25. Depth ranges for each species have been added as Dmin and Dmax; Table S2: Mean temperature profiles and standard deviation profiles (STD) for each calendar month for the ESAL region; Table S3: Mean temperature profiles and standard deviation profiles (STD) for each calendar month for the LEBA region; Table S4: Depth ranges (minimum and maximum) and temperature ranges (minimum, maximum and mean) for ESAL native species, from T&B25 and Met Office climatology data; Table S5: Depth ranges (minimum and maximum) and temperature ranges (minimum, maximum and mean) for LEBA native species, from T&B25 and Met Office climatology data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V.-Y., J.W.L., C.C. and E.V.-G.; methodology, M.V.-Y., J.W.L., C.C. and E.V.-G.; software, M.V.-Y., J.W.L., C.C. and E.V.-G.; validation, M.G. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, M.V.-Y.; investigation, M.V.-Y., J.W.L., C.C., E.V.-G., M.C.G.-M., E.B., C.A. and Y.Z.; resources, J.C.B. and D.T.; data curation, M.V.-Y., J.W.L., C.C., E.V.-G., J.C.B. and D.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.V.-Y.; writing—review and editing, M.V.-Y., J.W.L., C.C., E.V.-G., E.B., C.A., F.M., M.C.G.-M., J.C.B. and D.T.; visualization, M.V.-Y., E.B., M.G. and Y.Z.; supervision, F.M. and M.C.G.-M.; project administration, F.M. and M.C.G.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Temperature data were downloaded from the Met Office Hadley Centre EN4 dataset (https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/en4/, accessed on 6 August 2025) and are freely available at this website. The complete list of native species in the ESAL and LEBA demarcations was adapted from B19 and has been provided in Table S1 in Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of temperature climatology compiled by the Met Office Hadley Center www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs, accessed on 2 June 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| T&B25 | Torreblanca and Báez, 2025 [24] |

| B19 | Báez et al., 2019 [25] |

| ESAL | Estrecho–Alborán |

| LEBA | Levantino–Balear |

References

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Brno, J.F. The Impact of Climate Change on the World’s Marine Ecosystems. Science 2010, 328, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate; Pörtner, H.-O.D.C., Roberts, V., Masson-Delmotte, P., Zhai, M., Tignor, E., Poloczanska, K., Mintenbeck, A., Alegría, M., Nicolai, A., Okem, J., et al., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, C.M.; Agusti, S.; Barbier, E.; Britten, G.L.; Castilla, J.C.; Gattuso, J.-P.; Fulweiler, R.W.; Hughes, T.P.; Knowlton, N.; Lovelock, C.E.; et al. Rebuilding marine life. Nature 2020, 580, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergés, A.; Steinberg, P.D.; Hay, M.E.; Poore, A.G.B.; Campbell, A.H.; Ballesteros, E.; Heck, K.L., Jr.; Booth, D.J.; Coleman, M.A.; Feary, D.A.; et al. The tropicalization of temperate marine ecosystems: Climate-mediated changes in herbivory and community phase shifts. Proc. R. Soc. B 2014, 281, 20140846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osland, M.J.; Stevens, P.W.; Lamont, M.M.; Brusca, R.C.; Hart, K.M.; Waddle, J.H.; Langtimm, C.A.; Williams, C.M.; Keim, B.D.; Terando, A.J.; et al. Tropicalization of temperate ecosystems in North America: The northward range expansion of tropical organisms in response to warming winter temperatures. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 27, 3009–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, J.J. Climate-Related Local Extinctions Are Already Widespread among Plant and Animal Species. PLOS Biol. 2016, 14, e2001104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, C.; Katsanevakis, S. Marine extinctions and their drivers. Reg. Environ. Change 2023, 23, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.N.; Morri, C. Marine Biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: Situation, Problems and Prospects for Future Research. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2000, 40, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.N.; Morri, C. Global sea warming and “tropicalization” of the Mediterranean Sea: Biogeographic and ecological aspects. Biogeogr.—J. Integr. Biogeogr. 2003, 24, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrabou, J.; Gómez-Gras, D.; Ledoux, J.-B.; Linares, C.; Bensoussan, N.; López-Sendino, P.; Bazairi, H.; Espinosa, F.; Ramdani, M.; Grimes, S.; et al. Collaborative Database to Track Mass Mortality Events in the Mediterranean Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juza, M.; Tintoré, J. Multivariate Sub-Regional Ocean Indicators in the Mediterranean Sea: From Event Detection to Climate Change Estimations. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 610589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juza, M.; Fernández-Mora, A.; Tintoré, J. Sub-Regional Marine Heat Waves in the Mediterranean Sea from Observations: Long-Term Surface Changes, Sub-Surface and Coastal Responses. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 785771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrabou, J.; Gómez-Gras, D.; Medrano, A.; Cerrano, C.; Ponti, M.; Schlegel, R.; Bensoussan, N.; Turicchia, E.; Sini, M.; Gerovasileiou, V.; et al. Marine heatwaves drive recurrent mass mortalities in the Mediterranean Sea. Glob. Mar. Biol. 2022, 28, 5708–5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatés, A.; Martín, P.; Lloret, J.; Raya, V. Sea warming and fish distribution: The case of the small pelagic fish Sardinella aurita in the western Mediterranean. Glob. Change Biol. 2006, 12, 2209–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzurro, E.; Sbragaglia, V.; Cerri1, J. Climate change, biological invasions, and the shifting distribution of Mediterranean fishes: A large-scale survey based on local ecological knowledge. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 2779–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golani, D.; Azzuro, E.; Dulcic, J.; Massuti, E.; Orsi-Relini, L. Atlas of Exotic Fishes in the Mediterranean Sea, 2nd ed.; Briand, F., Ed.; IESM Publishers: Paris, France, 2021; p. 365. [Google Scholar]

- Farré, M.; Lombarte, A.; Tuset, V.M.; Salmerón, F.; Vivas, M.; Abelló, P. Tropicalization induced by non-native species in the western Mediterranean Sea: Effects on decapod crustacean taxocoenoses. Estuarine Coast. Shelf Sci. 2024, 313, 109114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.N.; Boero, F.; Fraschetti, S.; Morri, C. La fauna del Mediterrán eo. In La fauna in Italia; Argano, R., Chemini, C., Laposta, S., Minelli, A., Ruffo, S., Eds.; Touring Editore; Milano e Ministero dell’Ambiente e la Tutela del Territorio: Roma, Italy, 2002; pp. 247–335. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz Meyer, A.; Pigot, A.L.; Merow, C.; Kaschner, K.; Garilao, C.; Kesner-Reyes, K.; Trisos, C.H. Temporal dynamics of climate change exposure and opportunities for global marine biodiversity. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, P.G.; Steger, J.; Bošnjak, M.; Dunne, B.; Guifarro, Z.; Turapova, E.; Hua, Q.; Kaufman, D.S.; Rilov, G.; Zuschin, M. Native biodiversity collapse in the eastern Mediterranean. Proc. R. Soc. B 2021, 288, 20202469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, P.G.; Schultz, L.; Wessely, J.; Taviani, M.; Dullinger, S.; Danise, S. The dawn of the tropical Atlantic invasion into the Mediterranean Sea. PNAS 2024, 121, e2320687121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chust, G.; Villarino, E.; McLean, M.; Mieszkowska, N.; Benedetti-Cecchi, L.; Bulleri, F.; Ravaglioli, C.; Borja, A.; Muxika, I.; Fernandes-Salvador, J.A.; et al. Cross-basin and cross-taxa patterns of marine community tropicalization and deborealization in warming European seas. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzurro, E.; Ballerini, T.; Antoniadou, C.; Aversa, G.D.; Ben Souissi, J.; Blašković, A.; Cappanera, V.; Chiappi, M.; Cinti, M.-F.; Colloca, F.; et al. ClimateFish: A Collaborative Database to Track the Abundance of Selected Coastal Fish Species as Candidate Indicators of Climate Change in the Mediterranean Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 910887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torreblanca, D.; Baez, J.C. Tropicalization of the Mediterranean Sea Reflected in Fish Diversity Changes: A Case Study from Spanish Waters. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Báez, J.C.; Rodríguez-Cabello, C.; Bañón, R.; Britos, A.; Falcón, J.M.; Maño, T.; Baro, J.; Macías, D.; Meléndez, M.J.; Camiñas, J.A.; et al. Updating the national checklist of marine fishes in Spanish waters: An approach to priority botspots and lessons for conservation. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2019, 20, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, K.; BEN Ismail, S.; Bensi, M.; Bosse, A.; Chiggiato, J.; Civitarese, G.M.F.F.; Fusco, G.; Gačić, M.; Gertman, I.; KUBIN, E.; et al. A consensus-based, revised and comprehensive catalogue for Mediterranean water masses acronyms. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2024, 25, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, S.A.; Martin, M.J.; Rayner, N.A. EN4: Quality controlled ocean temperature and salinity profiles and monthly objective analyses with uncertainty estimates. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2013, 118, 6704–6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouretski, V.; Reseghetti, F. On depth and temperature biases in bathythermograph data: Development of a new correction scheme based on analysis of a global ocean database. Deep-Sea Res. I 2010, 57, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouretski, V.; Cheng, L. Correction for Systematic Errors in the Global Dataset of Temperature Profiles from Mechanical Bathythermographs. J. Atmos. Technol. Ocean. Res. 2020, 37, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, M.; Cebrian, E.; Francour, P.; Galil, B.; Savini, D. Monitoring Marine Invasive Species in Mediterranean Marine Protected Areas (MPAs): A strategy and practical guide for managers; IUCN: Malaga, Spain, 2013; p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- Figuerola-Ferrando, L.; Linares, C.; Zentner, Y.; López-Sendino, P.; Garrabou, J. Marine Citizen Science and the Conservation of Mediterranean Corals: The Relevance of Training, Expert Validation, and Robust Sampling Protocols. Environ. Manag. 2024, 73, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Yáñez, M.; Moya, F.; Serra, M.; Juza, M.; Jordà, G.; Ballesteros, E.; Alonso, C.; Pascual, J.; Salat, J.; Moltó, V.; et al. Observations in the Spanish Mediterranean Waters: A Review and Update of Results of 30-Year Monitoring. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacic, M.; Ordines, F.; Ramírez-Amaro, S.; Schliewen, U.K. Gymnesigobius medits (Teleostei: Gobiidae), a new gobiid genus and species from the western Mediterranean slope bottoms. Zootaxa 2019, 4651, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacic, M.; Renoult, J.P.; Pillon, R.; Bilecenoglu, M.; Tiralongo, F.; Bogorodsky, S.V.; Engin, S.; Kovtun, O.; Louisy, P.; Patzner, R.A. The Delimitation of Geographic Distributions of Gobius bucchichi and Gobius incognitus (Teleostei: Gobiidae). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglésias, S.P.; Vukić, J.; Sellos, D.Y.; Soukupová, T.; Šanda, R. Gobius xoriguer, a new offshore Mediterranean goby (Gobiidae), and phylogenetic relationships within the genus Gobius. Ichthyol. Res. 2021, 68, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanda, R.; Kovaciv, M. First record of Gobius couchi (Gobiidae) in the Ionian Sea. Cybium 2009, 33, 249–250. [Google Scholar]

- Kondylatos, G.; Theocharis, A.; Mandalakis, M.; Avgoustinaki, M.; Karagyaurova, T.; Koulocheri, Z.; Vardali, S.; Klaoudatos, D. The Devil Firefish Pterois miles (Bennett, 1828): Life History Traits of a Potential Fishing Resource in Rhodes (Eastern Mediterranean). Hydrobiology 2024, 3, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowat, D.; Brooks, K.S. A review of the biology, fisheries and conservation of the whale shark Rhincodon typus. J. Fish Biol. 2012, 80, 1019–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Béarez, P.; Pruvost, P.; Feunteun, E.; Iglésias, S.; Francour, P.; Causse, R.; Mazieres, J.D.; Tercerie, S.; Bailly, N. Checklist of the marine fishes from metropolitan France. Cybium 2017, 41, 351–371. [Google Scholar]

- Kovačić, M.; Ordines, F.; Schliewen, U.K. A new species of Buenia (Teleostei: Gobiidae) from the western Mediterranean Sea, with the description of this genus. Zootaxa 2017, 4250, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, C.; Gurlek, M.; Erguden, D.; Hakan Kabaskal, H. A new record for the shark fauna of the Mediterranean Sea: Whale shark, Rhicodon typus (Orectolobiformes: Rhincodontidae). Ann. Ser. Hist. Nat. 2021, 31, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).