Abstract

In coastal regions, the interaction between freshwater and seawater creates a dynamic system in which the spatial distribution of salinity critically constrains the use of freshwater for human consumption. Although saline intrusion is a globally widespread phenomenon, its inland extent varies significantly with hydrological conditions, posing a persistent threat to groundwater quality and sustainability. This study aimed to characterize salinity distribution using an integrated karst-watershed approach, thereby enabling the identification of both lateral and vertical salinity gradients. The study area is in the northwestern Yucatan Peninsula. Available hydrogeological data were analyzed to determine aquifer type, soil texture, evidence of saline intrusion, seawater fraction, vadose zone thickness, and field measurements. These included sampling from 42 groundwater sites (open sinkholes and dug wells), which indicated a fringe zone approximately 5 km in size influenced by seawater interaction, in mangrove areas and in three key zones of salinity patterns: west of Mérida (Celestun and Chunchumil), and northern Yucatan (Sierra Papacal, Motul, San Felipe). Vertical Electrical Sounding (VES) and conductivity profiling in two piezometers indicated an apparent seawater influence. The interface was detected at a depth of 28 m in Celestun and 18 m in Chunchumil. These depths may serve as hydrogeological thresholds for freshwater abstraction. Results indicate that saltwater can extend several kilometers inland, a factor to consider when evaluating freshwater availability. This issue is particularly critical within the first 20 km from the coastline, where increasing tourism exerts substantial pressure on groundwater reserves. A coastal-to-inland salinity was identified, and an empirical equation was proposed to estimate the seawater fraction (fsea%) as a function of distance from the shoreline in the Cenote Ring trajectory. Vertically, a four-layer model was identified in this study through VES in the western watershed: an unsaturated zone approximately 2.6 m thick, a confined layer in the coastal Celestun profile about 9 m thick, a freshwater lens floating above a brackish layer between 8 and 25 m, and a saline interface at 37 m depth. The novelty of this study, in analyzing all karstic water surfaces together as a system, including the vadose zone and the aquifer, and considering the interactions with the surface, is highlighted by the strength of this approach. This analysis provides a better understanding and more precise insight into the integrated system than analyzing each component separately. These findings have significant implications for water resource management in karst regions such as Yucatan, underscoring the urgent need for sustainable groundwater management practices to address seawater intrusion.

1. Introduction

In coastal areas, proximity to the sea results in three-dimensional interactions between freshwater and saltwater that vary with the movement patterns of saline water. These interactions occur through three primary, interrelated mechanisms. The first and most common is marine intrusion, characterized by the horizontal inland advance of saline water, forming a saline wedge whose extent depends on the hydraulic balance between freshwater and seawater. The second mechanism is pumping-induced intrusion, marked by the upward vertical migration of saline water when excessive freshwater extraction reduces hydrostatic pressure, allowing deep saline water to reach the abstraction points. The third mechanism is saline recharge, defined as the downward vertical infiltration of saline water from surface aquatic systems such as streams, coastal marine channels, and marshes [1,2].

This spatial distribution of salinity imposes a critical constraint on the use of freshwater for human consumption and productive activities. Although marine intrusion and aquifer salinization have been studied for over five decades, contemporary pressures, including population growth, land-use change, tourism-driven demand, sea-level rise, and anthropogenic pollution [3,4,5,6,7]. Hydrogeological studies across various countries demonstrate that saltwater intrusion worsens when groundwater extraction exceeds recharge rates and population density increases. For instance, Ref. [2] reported that coastal areas with large human settlements and excessive pumping are at high risk of saltwater contamination, threatening their groundwater supplies. Research conducted across diverse latitudes has shown that deep well drilling can induce downward migration of saltwater, compromising potable water sources. These findings contribute to the broader understanding of saltwater intrusion as a process driven by both natural dynamics and human disturbances.

The Ghyben–Herzberg principle provides a foundational theoretical framework for understanding freshwater–seawater interactions in coastal aquifers. According to this model, for every meter of freshwater above sea level, approximately 40 m of freshwater exists below the saline interface, assuming a sharp interface [8]. However, this approximation oversimplifies natural conditions, as sharp interfaces are rarely observed. More realistic models recognize a diffuse transition zone where water density changes gradually, producing a salinity gradient between freshwater and seawater [9,10]. The thickness of the transition zone can range from a few meters to several kilometers, depending on local hydrodynamics, aquifer properties, and temporal patterns of extraction and recharge.

In karst systems, groundwater flow capacity is governed by site-specific characteristics, including fracture density, dual permeability (matrix and conduit flow), the presence of confining units, and freshwater–seawater dynamics [11,12]. These systems are further complicated by spatial heterogeneity in hydraulic properties and preferential flow paths, which can accelerate saltwater intrusion into the continental interior [13]. In coastal aquifers such as those in the Yucatan Peninsula, salinity distribution is not only a geological concern but also a socioeconomic one. Freshwater availability is essential for agriculture, industry, tourism, and domestic use [14,15,16]. In this region, the economy depends heavily on groundwater quality and quantity, with tourism and agriculture generating thousands of jobs and contributing significantly to the regional Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Salinization of these resources could have severe consequences, including population displacement, reduced agricultural productivity, and the degradation of ecologically valuable coastal ecosystems.

The Yucatan Peninsula serves as the primary site for hydrogeochemical research, which uses 1500 samples to perform statistical clustering and multivariate data analysis, showing that seawater intrusion, gypsum dissolution, and human-made nitrate pollution result in groundwater salinization [17]. The Ghyben–Herzberg model successfully explains seawater intrusion in this karst system through electromagnetic data collection [17,18]. Scientists use ion-ratio analysis, strontium isotope analysis, and geochemical modeling to distinguish between marine intrusion and water–rock interactions in Mediterranean coastal aquifers, according to a worldwide review [19]. The assessment of aquifer salinization risk requires predictive hydrogeological models to examine different extraction, recharge, and sea-level rise scenarios for resource management [20]. A third of wells in Yucatan exhibit severe salinization, requiring immediate implementation of integrated monitoring systems and complex models to protect groundwater resources from human activities and climate change [17,19,20].

Research studies on coastal karst aquifers have employed multiple testing methods to determine how salinity affects the positions of hydrogeological boundaries. The research by [6] on the Ring of Cenotes showed electrical conductivity values ranging from 0.5 mS/cm to 55 mS/cm. The research data showed that water chemistry patterns changed significantly due to natural seasonal variations and human activities. Likewise, Ref. [21] studied the regionalization of water chemistry and isotope analysis to identify three hydrogeochemical regions within the Yucatan aquifer. Their results demonstrate that sulfate-rich waters, formed by mineral dissolution, travel along major structural routes. The study revealed that freshwater depths in coastal areas range from 8 to 12 m, but the deepest point in the country reaches 55 m before saltwater contamination begins at depths between 55 and 70 m. Moreover, the recent investigation by [22] applied inverse geochemical modeling to define the regional hydrogeochemical evolution of groundwater in the Ring of Cenotes. This work reinforces the identification of specific hydrogeochemical zones and clarifies the processes that control solute transport in this coastal karst environment. However, the complexity of karst areas requires continued research on these topics. In this context, a complete understanding of salinity distribution in coastal karst watersheds requires an integrated approach that combines hydrogeochemical characterization, isotopic analysis, geophysical surveying, statistical techniques, and process-based numerical modeling within a comprehensive research framework.

Climatic factors, such as sea-level rise and storm surge flooding, can disrupt the natural freshwater–seawater balance [23]. Griggs and Reguero [18] reported that the increasing frequency and intensity of coastal flooding events may enhance the risk of saline intrusion. Recent studies by Bosserelle et al. [24] and Zamrsky et al. [25] have documented how these extreme climatic events worldwide—whose frequency is increasing due to climate change—can cause acute saline intrusions, with aquifers requiring years to recover.

In México, saline intrusion into coastal aquifers has been recognized as a critical issue since the 1970s, particularly in Baja California, Sonora, and the Yucatan Peninsula. Ref. [3] developed vulnerability indices for the Yucatan karst aquifer, revealing a high risk of contamination due to its unique hydrogeological features. Ref. [4] examined the impact of anthropogenic activities on groundwater salinity in cenotes. The causes of salinization included aquifer overexploitation, declining freshwater levels, and climate change. The Yucatan Peninsula is particularly vulnerable due to its karstic nature, characterized by highly permeable limestone formations and extensive subterranean conduits that facilitate the inland migration of saltwater [23,26]. Additional pressures stem from tourism and urban expansion [23]. For example, Ref. [27] identified intensive tourism in the Riviera Maya as a source of groundwater pollution, while [18] highlighted aquifer stress from rapid urban growth in Cancún and Playa del Carmen. Additionally, Ref. [27] reported fecal contamination of drinking water in Tulum linked to human activities. Groundwater is the primary freshwater source in the Yucatan Peninsula, yet it is highly susceptible to contamination due to the karst terrain [4,5,6,26]. The region exhibits complex salinity patterns with both lateral and vertical variability [28,29,30,31], posing significant challenges for sustainable groundwater management.

Given the critical role of salinity distribution in constraining freshwater use, this study aimed to characterize its spatial variability using an integrated karst watershed approach, analyzing the vadose zone and the aquifer together with the surface, and considering interactions with the surface. This is the strength of this approach. This analysis provides a better understanding and more precise insight into the integrated system than analyzing each component separately.

This methodology enables the detection of both horizontal and vertical salinity gradients. The findings are expected to inform regional water planning in three key areas: delineating zones suitable for water use, establishing public water supply protection areas, and developing adaptation strategies for climate change. The study investigates both the natural occurrence of salinity in marine-influenced environments and the role of pumping in exacerbating saltwater intrusion, offering new insights into the hydrogeological processes in coastal karst systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

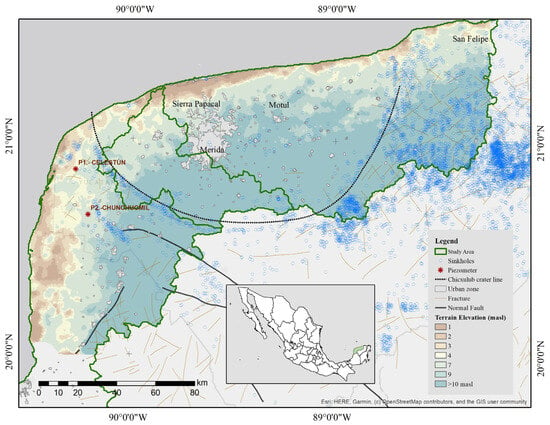

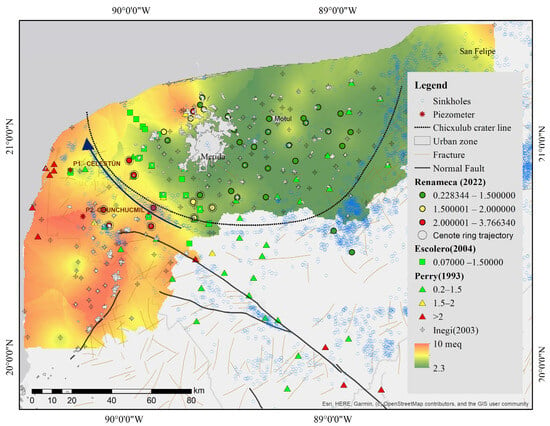

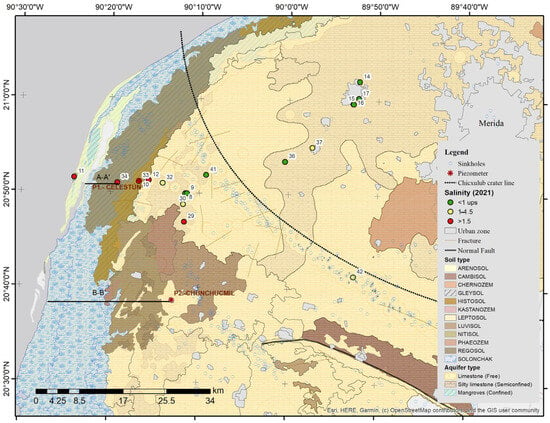

The study area is in the northwestern region of the Yucatan Peninsula and spans approximately 22,990 km2. It lies between latitudes 19°59′01″ N and 21°34′30″ N, and longitudes 90°29′39″ W and 88°12′15″ W. It is bordered to the north and west by the Gulf of Mexico; to the south by the municipalities of Santa Elena, Ticul, Chapab, Tecoh, Tekit, Sotuta, and Dzitás; and to the east by the municipalities of Río Lagartos and Tizimín (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study zone. This limit represents a Karstic watershed. P1 and P2 are the piezometers of the CONAGUA piezometric network selected for salinity profiling and VES.

In this region, sinkholes—locally known as cenotes—are water-filled caves connected by subterranean conduits. Many cenotes are concentrated within the “Cenote Ring”, which defines the direction of groundwater flow toward the ocean. Although surface rivers are absent, groundwater flows from higher to lower elevations [29]. Cenotes are closely associated with the buried margin of the Chicxulub crater, suggesting a link between the formation of the crater and the development of karst features. Cenote morphology results primarily from selective dissolution along structural discontinuities in carbonate rocks during groundwater movement [31].

From a hydrogeological perspective, cenotes play a critical role in recharging the peninsula’s phreatic aquifer system. Groundwater flow is regulated by the geomorphology of the Cenote Ring, which governs water movement at a regional scale. Due to their direct hydraulic connectivity, cenotes also serve as natural indicators of aquifer vulnerability to contamination, particularly from anthropogenic sources [22,26].

The Yucatan Peninsula has a tropical climate, classified as subhumid under the Köppen–Geiger system (Aw and Ax′(w)). Temperatures remain high year-round, with a rainy season extending from May to October. Average temperatures range from 25 °C to 35 °C, and relative humidity is consistently elevated [32]. Over the past 30 years, the region has experienced a decline in total annual precipitation, despite an increase in rainfall intensity [29]. Evapotranspiration is closely linked to vegetation cover and varies according to climate conditions and extreme weather events [33].

The study area is representative of the hydrographic basin, as defined by Grill et al. [34] as the surface boundary where interactions occur between the surface and subsoil systems. The aquifer system lies within karst terrain exhibiting a strong marine influence.

According to the National Water Law [35], the following definitions apply:

- Aquifer: “A geological formation or a group of hydraulically interconnected geological formations through which water flows or is stored with the possibility of its use for development, consumption, or extraction, and the lateral and vertical limits of which are conventionally specified for evaluation, management, and administration of the national groundwater resources” [35].

- Hydrographic watershed: “It is the unit of the territory, which is separate from other areas, which are usually delimited by a watershed line; a polygonal line formed by the points of highest elevation, where water occurs in different forms, which are stored or flow to an outlet point that may be the sea or another inland receiving body, through a hydrographic network of channels that converge in a main one, or the territory where waters form an autonomous system or are distinguishable from other areas even if they do not flow into the sea. Water, soil, flora, fauna, and other resources can be found together in this space: topographic diversity defines the delimiting space” [35].

Watersheds and aquifers are appropriate spatial units for managing water resources. As stated in the National Water Law [35], Batllori-Canto [36] proposed using Planning Units for water-balance assessments in the Yucatan Peninsula, based on territorial characteristics and municipal boundaries.

For this study, the concept of a “karst watershed” was adopted as a natural surface boundary, delineated using Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) data and processed following the methodology of Grill et al. [34]. The study area is illustrated in Figure 1, with topographic elevations ranging from 40 m to 1 m above sea level. Geomorphological features such as sinkholes and fractured faults influence preferential groundwater flow. The data compiled for this analysis includes information from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography [37,38] and the national piezometric network maintained by the National Water Commission [39].

Anthropogenic activities, particularly tourism and increasing visitor numbers, have been associated with elevated fecal contamination [4]. Additionally, various human activities can alter the chemical composition of groundwater, creating imbalances in aquatic systems that support regional biodiversity, which is highly dependent on groundwater availability [40].

2.2. Hydrogeological Data

Hydrogeological studies require integrating multiple datasets, including geology, hydrology, geomorphology, soil characteristics, climate, land use, topography, and anthropogenic features. This data must be analyzed in conjunction with existing databases and field measurements. Conceptualizing the groundwater system is the initial step in modeling, providing a comprehensive overview of system boundaries, properties, and processes [41].

Aquifer Type: The type of aquifer influences the extent and vulnerability of saline intrusion. For example, unconfined aquifers under natural conditions are more susceptible to saline intrusion because they lack protective confining layers. According to Kachadourian et al. [42], superficial evidence of groundwater flow systems refers to the “manifestations of groundwater in soil, vegetation, and/or topographic forms.” In this study, the aquifer was classified as confined, particularly in areas adjacent to mangrove fringes, where a low-permeability layer known as “caliche” is present [43].

Soil Texture: Soil texture was used to classify permeability by hydrologic type and rainfall–runoff patterns. For instance, hydrologic type A exhibits very high permeability; leptosol type B, moderate permeability; and solonchak type D, low permeability [41]. Accordingly, soil texture data from INEGI (scale 1:250,000) and the Mayan soil classification system were incorporated [44].

Evidence of Saline Intrusion: The chloride-to-bicarbonate (Cl/HCO3) ratio was employed to detect saline intrusion. It is important to note that the study area exhibits variable conditions, including climatic factors that influence the natural balance between saltwater and freshwater. Chloride ions are predominant in seawater and occur in low concentrations in groundwater, whereas bicarbonate ions are typically dominant in freshwater systems [45]. Groundwater data were obtained from the National Geographic Database [46]. The seawater fraction (fsea%) in groundwater samples was estimated using Equation (1), as proposed by Frollini et al. [19]:

where mcl represents the chloride concentration of the sample, mcl,FW denotes the chloride concentration of the freshwater endmember. For this study, a value of 250 mg/L was used, corresponding to the freshwater chloride salinity threshold. mcl,SW refers to the chloride concentration in seawater, which was 19,500 mg/L.

Vadose Zone Thickness: Aquifer thickness influences the extent of the saline intrusion wedge; thinner aquifers are associated with more profound and more extensive intrusion. The vadose zone was delineated using data from the CONAGUA piezometric network by subtracting the average water table elevation (based on piezometric records from 1997 to 2021) from the terrain elevation [41].

2.3. Field Methodology

- A field survey was conducted along a transect from Mérida to Celestun in 2021 to record salinity levels using a Hanna HI9828 multiparametric system, previously calibrated according to the manufacturer’s specifications.

- Monitoring of the freshwater–saltwater interface was performed by measuring conductivity, temperature, and depth using a CTD Diver (VanEssen), with readings ranging from 0 to 120 mS/cm in two piezometers located in Celestun and Chunchumil (see Figure 1).

- Vertical Electrical Sounding (VES) was carried out using the SuperSting R8 system (Advanced Geosciences) with a Schlumberger array configuration (AB/2 = 100 m). Data was processed using the Ipi2Win software (free version 3.01) for both piezometers.

Spatial representation of GIS data was performed in ArcGIS 10.5 using Ordinary Kriging interpolation with a spherical semivariogram model, a commonly used geostatistical approach. The output cell size was set to 500 m using the Spatial Analyst module. The mapping scale was 1:250,000.

3. Results

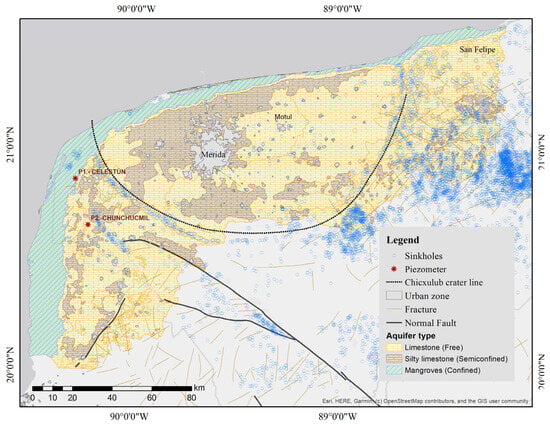

3.1. Aquifer Type

Analysis of aquifer type indicates that the unconfined aquifer is located within the recharge–transit zone, coinciding with the ring of sinkholes (Figure 2). Urban areas were excluded from this classification.

Figure 2.

Aquifer type (confined, semi-confined, and unconfined) is based on surface evidence of the groundwater flow system [39].

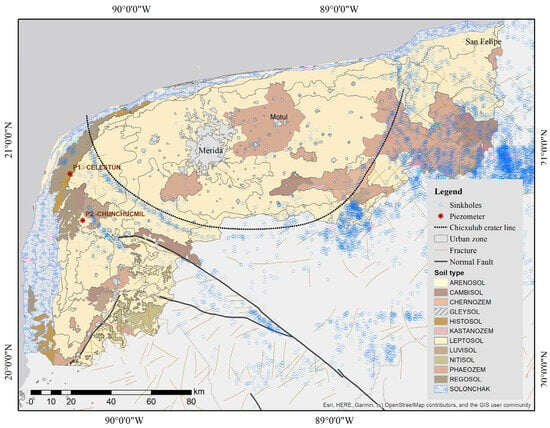

3.2. Soil Type

Twelve soil types were identified within the study area [46] (Figure 3). Solonchak soils occur near coastal mangrove zones and are characterized by saline conditions. The dominant soil type is leptosol. In the western region, where piezometers are located, regosol is present—a mineral soil shaped by lowland topography. Beach zones are classified as arenosol [47].

Figure 3.

Soil type in the study zone according to INEGI [44]. The main soil types in the coastal zone are classified as solonchak and leptosol.

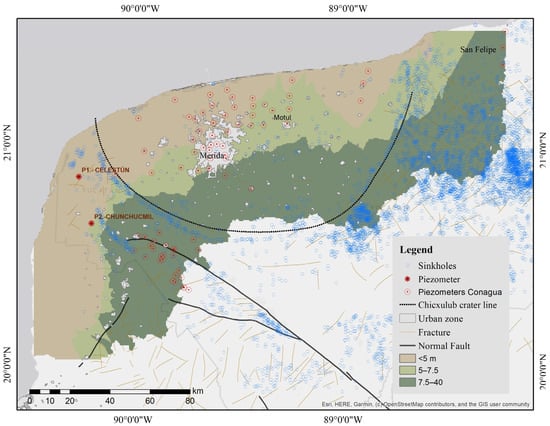

3.3. Thickness of the Vadose Zone

Figure 4 illustrates the vadose zone, representing the thickness of the unsaturated layer measured from terrain elevation to the average depth of the piezometric surface. Three thickness ranges were identified: <5 m, 5–7.5 m, and 7.5–40 m. For example, in Celestun and Chunchumil, the vadose zone is <5 m, whereas in the southern portion of the watershed, groundwater depths reach up to 40 m.

Figure 4.

The vadose zone represents the thickness of groundwater from terrain elevation to the piezometer’s average depth, which is the mean groundwater depth level.

Piezometric data were obtained from CONAGUA, based on 89 piezometers distributed across three monitoring networks: Opichén (26 wells), Metropolitana (32 wells), and Costera Campo (31 wells). Annual measurements were recorded from 1997 to 2021.

- In the Opichén network, the average water table depth is 28.5 m, with a minimum of 8.6 m and a maximum of 51.1 m.

- In the Metropolitana network, the average depth is 5.3 m (range: 0.05–13.56 m).

- In the Costera network, the average depth is 4.4 m (range: 0.10–9.11 m).

Specifically, in Celestun, vadose thickness is 0.5 ± 0.3 m, and in Chunchumil it is 1.9 ± 0.5 m—both <5 m. In the southern watershed, groundwater depths exceed 40 m [39].

3.4. Ratio Cl/HCO3

Figure 5 presents the Cl/HCO3 ratio as an indicator of seawater intrusion (SWI), where chloride (Cl−) represents marine input and bicarbonate (HCO3−) reflects groundwater output. Higher ratios on the western side suggest greater SWI.

Figure 5.

Relation Cl−/HCO3− as an indicator of seawater intrusion, considering data of INEGI [48], Perry [28], Escolero [49], and RENAMECA [39].

Interpolation was performed using the GALDIT methodology [45]:

- <1.5 epm (meq/L) indicates freshwater;

- 1.5–2 epm indicates brackish water;

- >2 epm indicates saltwater.

Among 320 data points, the Cl/HCO3 ratio ranged from a minimum of 0.12 at San Antonio Tedzidz (42 km from the coast) to a maximum of 140.72 in an ojo de agua (submarine groundwater discharge) in the western watershed. Salinity fronts were identified at Sierra Papacal, Motul, and San Felipe.

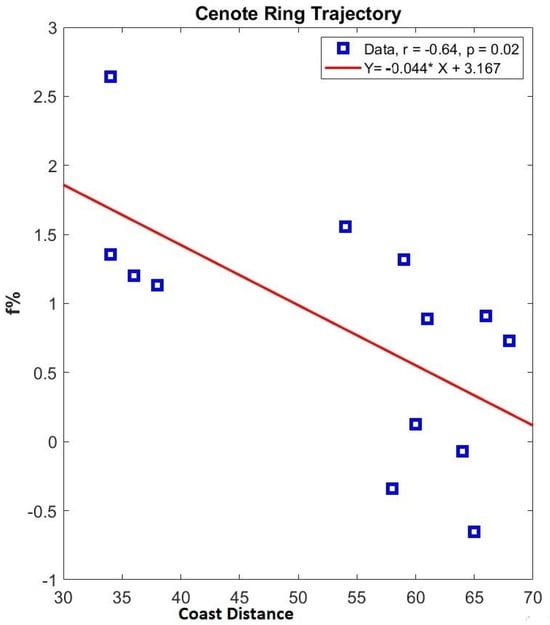

3.5. Seawater Fraction (Fsea%)

Using recent data [39], the seawater fraction (fsea%) was calculated as a function of coastline distance. Chloride concentrations ranged from 36.2 to 758.3 mg/L, with an average of 250 mg/L. Sampling distances from the coastline ranged from 10 to 94 km.

Figure 6 shows that sites within 20 km exhibit fsea% >1, indicating significant seawater influence. Negative values represent freshwater sites, whereas positive values indicate salinity. The proposed equation is based on a linear approximation (r = −0.64, p = 0.02), suggesting a correlation between these variables in the context of groundwater flow from inland toward the sea [28,29]. Selected sites are shown in Figure 5 along the Cenote Ring trajectory.

Figure 6.

Relationship between fsea (%) and distance to the nearest coastline (km).

This study found that the salinity mixing extends up to 20 km inland. Sites with Cl/HCO3 ratios > 2 epm were identified near Chunchumil and Celestun.

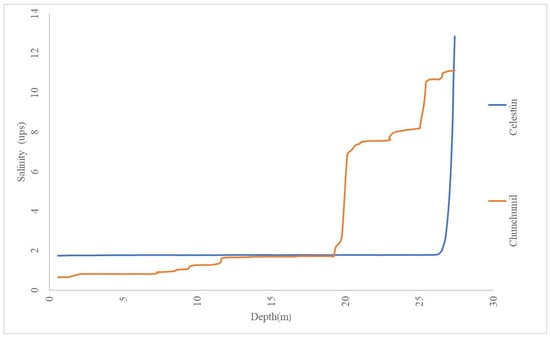

3.6. Freshwater–Seawater Interface

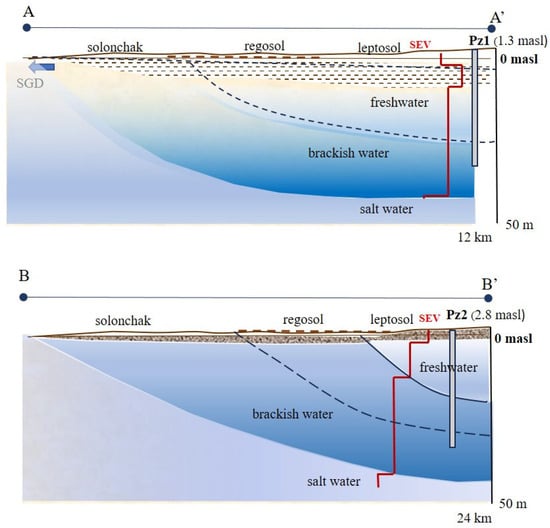

In February 2022, the freshwater–seawater interface was measured at piezometers Pzp1 (Celestun, 12 km from the coastline) and Pzp2 (Chunchumil, 24 km inland). CTD measurements (Figure 7) revealed a depth-dependent salinity variation. The interface was detected at 28 m in Celestun and 18 m in Chunchumil, exhibiting a stepped profile.

Figure 7.

Freshwater–saltwater interface in the piezometers Celestun (P1) and Chunchumil (P2), based on measurement with a CTD diver. The figure displays a salinity profile.

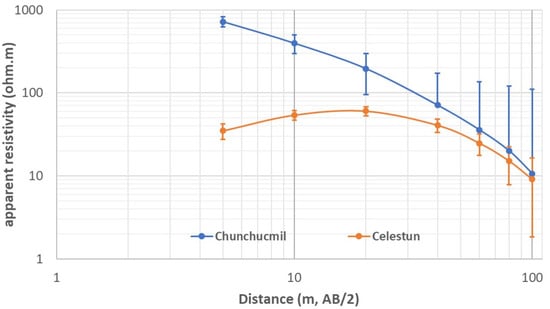

A geophysical survey was conducted using Vertical Electrical Sounding (VES) with a Schlumberger electrode array (AB/2 = 100 m), reaching depths of ~30 m. Raw data (Figure 8, logarithmic scale) show apparent resistivity values ranging from 10 to 1000 Ω·m, consistent with limestone formations. As AB/2 spacing increased, apparent resistivity decreased, diverging from the mean.

Figure 8.

Apparent resistivity graph of VES in Celestun and Chunchucmil applying the Schlumberger array.

Layer models generated using the Ipi2win software yielded error margins of 0.1% for Chunchumil and 1.2% for Celestun. In both soundings, a marked resistivity drop was observed between 25 and 30 m, with values decreasing by 2–3 ohm·m, interpreted as a saline layer. Stratigraphy suggests a freshwater layer overlying brackish water, which in turn overlies a saline layer.

Table 1 presents four-layer geological configurations for Celestun and Chunchumil. In Celestun, the surface layer consists of compact limestone (unsaturated zone), followed by a 5.6 m-thick low-permeability layer, a 28 m-thick high-permeability freshwater lens, and a saline karstic zone. In Chunchumil, the surface layer is approximately 2.7 m thick and underlain by limestone that transitions from freshwater to brackish water. At a depth of 37 m, a marked resistivity contrast indicates the presence of a saline limestone layer.

Table 1.

Resistivity model.

3.7. Horizontal and Vertical Distribution of Salinity

Groundwater sampling from dug wells and open sinkholes (Figure 9) highlights a coastal fringe zone approximately 5 km from the shoreline, influenced by seawater interaction, particularly in mangrove areas. Field verification (Table 2) indicates horizontal salinity patterns in three key zones: west of Mérida (Celestun and Chunchumil), and in northern Yucatan (Sierra Papacal, Motul, and San Felipe), where structural fractures may enhance seawater intrusion.

Figure 9.

Salinity sampling in the field of groundwater sources (dug wells and open sinkholes). The piezometers are where the electrical soundings were realized.

Table 2.

Sampling sites in shallow wells and open sinkholes in 2021.

Figure 10 presents two conceptual west–east hydrogeological cross-sections that integrate geophysical and CTD data to delineate vadose and aquifer zones, subsurface layering, and salinity gradients. Saltwater can extend several kilometers inland, and this distribution must be considered when evaluating freshwater availability. Section A–A′ reveals an aquitard layer, supporting evidence of submarine groundwater discharge, as previously documented by Valle et al. [50], where aquifer freshwater discharges into the coastal ocean via springs.

Figure 10.

Hydrogeological section A–A’ (upper) and B–B’ (lower) oriented W-E according to geophysical and CTD interpretations. It shows the subsoil geometry and the salinity gradient (the red line indicates the geoelectric model). The water table is represented. Note. Pz: piezometer; SEV: Vertical Electrical Sounding; SGD: submarine groundwater discharge; masl: meters above sea level.

4. Discussion

The geology of the study area is predominantly composed of limestone formations ranging from the Eocene (55 Ma) to the Holocene (0.01 Ma). The city of Mérida lies within the Carrillo Puerto Formation of the Pliocene (5.1–1.68 Ma), which contains fossil evidence [51]. Coastal mangrove zones are classified as confined areas due to their low permeability and the presence of surface-weathered limestone, commonly referred to as “caliche” [43]. Semi-confined zones are defined as groundwater transit areas characterized by silty limestone.

Palma and Bautista [44] developed an application for Maya soil classification based on the World Reference Base, categorizing soils as modified, organic, or mineral. According to this system, leptosol covers approximately 12,905 km2, representing 65% of the study area, and is locally referred to as Chaltún lu’um (Maya), characterized by rocky, medium-textured soils (Figure 3).

Hydraulic conductivity in the region is approximately 0.064 m/s based on model calibration, ranging from 9 × 10−4 to 1 × 10−1 m/s in pumping tests [29]. In the northern watersheds, where the aquifer is classified as a coastal confined system, the hydraulic gradient is approximately 0.03 m/km. Under a projected sea-level rise scenario of 0.40 m, aquifer discharge may decrease, and the freshwater–saltwater interface could extend up to 18 km inland [52].

These publicly available data [28,39,48,49] were collected during the main hydrological seasons (dry: April–May; rainy: August–September) between 1998 and 2003 from wells with depths ranging from 3 to 100 m. Although groundwater salinity varies seasonally and interannually, monitoring is typically conducted once per year, mainly during the dry season; thus, this dataset was considered representative.

Comparison with Perry [28] and Escolero [49] revealed discrepancies, likely due to differences in sampling dates. Perry’s 1993 monitoring sites align with INEGI’s zoning. Escolero [49] reported freshwater conditions based on Cl/HCO3 ratios, differing from INEGI’s findings—possibly due to differences in sampling dates. More recent data from RENAMECA [39] show values exceeding 2 epm in the western zone, indicating stronger seawater connectivity.

In Quintana Roo and Yucatan, Trejo-Canul [18] applied the GALDIT index to assess SWI, using electrical conductivity (EC) as a classification metric. Values below 1000 μS/cm were assigned a score of 2.5. Based on EC, water types are classified as follows: freshwater (<2500 μS/cm), brackish water (2500–15,000 μS/cm), saline water (15,000–50,000 μS/cm), and seawater (>50,000 μS/cm) [53]. In May 2022, P1 (Celestun) recorded a surface EC of 3700 μS/cm (brackish water), while Pz2 recorded 1508 μS/cm (freshwater).

Narváez et al. [17] analyzed 1,528 water samples and identified seawater intrusion, gypsum dissolution, and nitrate contamination. These results suggest that while seawater–freshwater dynamics are naturally occurring, they can be exacerbated by surface pollution. The saltwater lens can be considered a hydrogeological boundary, and the freshwater lens must be precisely delineated to prevent degradation. For instance, Stalker et al. [54] applied geochemical tracers in Celestun and found that freshwater discharges play a critical role along the lagoon’s eastern boundary. In contrast, brackish groundwater predominates in the northern portion, while seawater is more prevalent in the southern part. Groundwater extraction in Celestun, including withdrawals by local hotels, further complicates resource management and intensifies pressure on the aquifer system.

The results shown in Figure 6 are consistent with those of Frollini et al. [19], who examined the evolution of inland-to-coast groundwater chemistry using major ions, trace elements, DOC, Sr isotope ratios, and geochemical modeling.

Ion ratios (Na/Cl, Cl/HCO3, and Ca/HCO3) are valuable indicators of salinity sources. Frollini et al. [19] observed that chloride is concentrated near the coast. Additional factors include anisotropy in zones of high hydraulic conductivity and seawater intrusion driven by sea-level fluctuations.

In a study combining Rare Earth Element (REE) analysis with a DRASTIC vulnerability assessment across 60 sinkholes in the Yucatan Peninsula, Gómez-Hernández et al. [55] identified the dominant water type as Ca-Mg-HCO3, indicating that carbonate dissolution is the prevailing geochemical process. They also observed a hydrogeochemical evolution toward Ca-Mg-Cl-SO4 facies. Notably, two deep-water samples exhibited a Na-Cl composition, suggesting a saline influence. Gibbs diagrams placed these samples outside the precipitation domain, further confirming that carbonate weathering is the predominant geochemical mechanism.

The results of Figure 7 suggest that interface depth does not correlate directly with distance from the coast, supporting the applicability of a diffusive model. Rocha et al. [53], in their study of the Merida–Progreso corridor, concluded that the Ghyben–Herzberg model is inadequate for determining the position of the freshwater–saltwater interface. They reported freshwater thicknesses ranging from 26 to 33 m in the Mérida urban zone, approximately 15 km from the coast.

The karst watershed approach enabled regional zoning of the western Yucatan Peninsula, where the Chunchumil and Celestun piezometers are located. Salinity profiles indicate an apparent seawater influence, with the freshwater–saline interface situated at 18 m in Chunchumil and 28 m in Celestun. These depths may serve as hydrogeological thresholds for freshwater abstraction, although they are subject to temporal variability driven by recharge dynamics and anthropogenic pressures [17].

Understanding the subsurface geometry is essential for delineating hydrogeological boundaries and improving assessments of groundwater availability. Geophysical studies of the Ring of Cenotes by Andrade-Gómez et al. [56] proposed a conceptual aquifer model comprising two primary hydrogeological units: an unsaturated zone approximately 10 m thick and a saturated fracture–cavern system containing freshwater, approximately 20 m thick, that overlaps the saline interface. This fractured zone suggests high hydraulically facilitating subsurface flow from the Cenote Ring toward the coast [29,56].

Moreno et al. [12] developed a flow model incorporating theoretical conduit scenarios and identified a vertically decreasing hydraulic conductivity (K) profile. Their four-layer model includes a conductive upper layer, a sandy-clay limestone layer, calcarenite, and reef limestone, extending to a depth of 80 m. These conduits may significantly influence groundwater flow from inland areas to the coast. These findings align with the four-layer model identified in this study through VES in the western watershed: an unsaturated zone approximately 2.6 m thick, a confined layer in the coastal Celestun profile about 9 m thick, a freshwater lens floating above a brackish layer between 8 and 25 m, and a saline interface at 37 m depth.

This study aimed to characterize salinity distribution using an integrated karst-watershed approach, thereby enabling the identification of both lateral and vertical salinity variations. Coastal aquifers are more vulnerable to groundwater extraction than to sea-level rise projections from global climate models [57], making them particularly susceptible to seawater intrusion. This issue is especially critical within the first 20 km from the coast, where tourism-driven water demand places significant pressure on freshwater resources. [2,3]. For example, the urban coastal zone of Celestun requires pumping water from 16 km inland to secure a freshwater supply [6,28].

These findings have important implications for water resource management in Yucatan and other karst regions [13,14,15], including the delineation of freshwater protection zones and restrictions on pumping within the 20 km coastal fringe. The interaction between freshwater availability and seawater intrusion underscores the need for sustainable practices that address both current demand and future climate change scenarios. An annual volume of 16.6 million m3 is extracted, representing 96% of the allocation designated for human use. Exceeding this threshold could compromise ecosystem sustainability and exacerbate saline intrusion [36,58]. As tourism continues to expand in coastal areas, it is essential to implement strategies that protect freshwater resources while balancing economic development with environmental sustainability [4,6,26,36].

5. Conclusions

A watershed-based approach was applied to northwestern Yucatan, identifying two northern watersheds within the sedimentary basin influenced by the Ring of Cenotes—where the metropolitan area of Mérida is located—and a western watershed shaped by a normal fault, encompassing the Ría Celestun Biosphere Reserve. The coastal mangrove zones are classified as confined areas due to their low permeability; semi-confined zones are defined as groundwater transit areas characterized by silty limestone. The unconfined aquifer is located within the ring of sinkholes and is concentrated. In the study area, the leptosol covers 65% of the area and is characterized by rocky coils with a medium texture. The vadose zone was identified into three zones: less than 5 m, 5–7.5 m, and 7.5–40 m.

This framework enabled the identification of lateral and vertical salinity variations. A linear equation was proposed along a selected trajectory of the Cenote Ring, indicating elevated salinity in this zone.

Marine intrusion, defined as the entry of seawater into the aquifer, can be detected using the Cl/HCO3 ratio in groundwater, which has proved to be a reliable indicator of salinity distribution. Groundwater sampling revealed a coastal fringe zone about 5 km from the shoreline and three horizontal salinity patterns: west of Mérida (Celestun, Chunchumil), and northern Yucatan (Sierra Papacal, Motul, San Felipe). The Cl/HCO3 ratio ranged from a minimum of 0.12 at San Antonio Tedzidz (42 km from the coast) to a maximum of 140.72 in an “ojo de agua” (submarine groundwater discharge) in the western watershed. This study found that the salinity mixing extends up to 20 km inland. Sites with Cl/HCO3 ratios > 2 epm were identified near Chunchumil and Celestun, according to the field verification.

CTD monitoring in wells is recommended to delineate the freshwater–saltwater interface. Saline intrusion refers to the penetration of saltwater into freshwater zones, as evidenced by CTD logs and geophysical data. Saltwater can extend several kilometers inland. The interface was detected at 28 m in Celestun and 18 m in Chunchumil; these results suggest that interface depth does not correlate directly with coastal proximity. This boundary should be closely monitored, as excessive pumping can induce bottom-up saline intrusion.

This study presents a four-layer model: (1) a vadose zone, (2) a low-permeability layer, (3) a permeable layer containing the freshwater–brackish water interface, and (4) a low-permeability saline layer. Hydrogeological cross-sections delineate a vadose zone near the surface. In Celestun, the water table depth was 0.5 m, and in Chunchumil, it was 1.8 m, calculating a hydraulic gradient of 1 × 10−4, with salinity in deep freshwater, brackish water, and saltwater. Geophysical techniques such as Vertical Electrical Sounding and Electrical Resistivity Tomography are practical tools for characterizing subsurface salinity distribution.

The results of this research will contribute to regional water planning by supporting the delineation of suitability zones for various water uses, the establishment of protection zones for public water supply catchments, and the development of adaptive management strategies in response to climate change.

The findings emphasize the urgent need for sustainable groundwater management. Effective practices, real-time water quality monitoring, and appropriate regulation are essential to mitigate the risks posed by saltwater intrusion—especially in tourism-intensive coastal zones like Celestun, where increasing visitor numbers have strained limited freshwater resources.

Future research should include uncertainty analysis and geochemical modeling of major elements to refine the system’s understanding. These efforts will improve predictive capabilities and support communication with stakeholders and local communities regarding freshwater vulnerability. Salinity distribution must be recognized as a hydrogeological constraint on freshwater utilization.

Overall, this study provides a robust foundation for understanding salinity dynamics in karst environments. The integration of geophysical and hydrochemical data revealed natural recharge processes and the complexity of near-surface aquifer systems, offering insights into groundwater availability in shallow coastal aquifers. Considering ongoing threats from climate change and increasing human activity, urgent action is needed to ensure the sustainable management of these vital water resources. With a commitment to sustainability and continued research, we can protect these essential freshwater reserves for future generations.

Author Contributions

I.N.-F., conceptualization, visualization, writing the original draft, reviewing, and editing. O.R.M.-P., conceptualization, writing the original draft, reviewing, and editing. F.A.-C., writing the original draft, reviewing, and editing. I.M.-T., writing, reviewing, and editing. C.C.-M., reviewing and editing. P.A.R.-A. reviewing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica (PAPIIT) of UNAM, grant number IA104722, “Límites ambientales hidrogeológicos en cuencas cársticas,” 2022–2023. Additionally, P.R.-A., thanks to Project PROTEO 2998/202 for providing funding for publication.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors (omedrano@secihti.mx(O.R.M.-P.); pa.robledo@igme.es (P.R.-A.)).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank CONAGUA and Engineer Raúl Palomo for the facilities provided for the analysis of the piezometric network and monitoring of the Chunchumil and Celestun piezometers. To the owners of the dug wells for allowing us to take the measurements. To technician M.C. Jesús Aragón for his support in the field work. To Ing. Ricardo Ibarra from “Aurora Geofísica” and Angel Cortés García, for the support with the VES. Authors appreciate the help of the anonymous reviewers; also, all authors agree on the expressions in this section.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fitts, C.R. Groundwater Science, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-12-384705-8. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, A.D.; Bakker, M.; Post, V.E.A.; Vandenbohede, A.; Lu, C.; Ataie-Ashtiani, B.; Simmons, C.T.; Barry, D.A. Seawater Intrusion Processes, Investigation and Management: Recent Advances and Future Challenges. Adv. Water Resour. 2013, 51, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Duarte, Y.; Bautista, F.; Mendoza, M.E.; Frausto, O.; Ihl, T.; Delgado, C. Ivaky: Índice De La Vulnerabilidad Del Acuífero Kárstico Yucateco a La Contaminación. Rev. Mex. De Ing. Química 2016, 15, 913–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcega-Cabrera, F.; León-Aguirre, K.; Enseñat-Soberanis, F.; Gíacoman-Vallejos, G.; Rodríguez-Fuentes, G.; Oceguera-Vargas, I.; Lamas-Cosío, E.; Simoes, N.D. Use of Microbiological and Chemical Data to Evaluate the Effects of Tourism on Water Quality in Karstic Cenotes in Yucatan, Mexico. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2023, 111, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcega-Cabrera, F.; Reyes-Larriva, D.; Casillas, T.A.D.; Vadillo, I. Overview on the impacts of CO2 acidification in a very sensible and complex system: The cenotes, Yucatan, Mexico. In CO2 Acidification in Aquatic Ecosystems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 199–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcega-Cabrera, F.; Sickman, J.O.; Fargher, L.; Herrera-Silveira, J.; Lucero, D.; Oceguera-Vargas, I.; Lamas-Cosío, E.; Robledo-Ardila, P.A. Groundwater Quality in the Yucatan Peninsula: Insights from Stable Isotope and Metals Analysis. Groundwater 2021, 59, 878–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elhamid, H.; Abdelaty, I.; Sherif, M. Evaluation of potential impact of Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on Seawater Intrusion in the Nile Delta Aquifer. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 2321–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeze Allen, R.; Cherry, J.A. Grounwater; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1979; ISBN 978-0-13-365312-0. [Google Scholar]

- Saqr, A.M.; Abd-Elmaboud, M.E. Management of Saltwater Intrusion in Coastal Aquifers: A Review and Case Studies from Egypt. Online J. Eng. Sci. 2024, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Luo, J. Steady-state freshwater–seawater mixing zone in stratified coastal aquifers. J. Hydrol. 2013, 505, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylroie, J.R.; Mylroie, J.E. Development of the carbonate island karst model. J. Cave Karst Stud. 2007, 69, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Gómez, M.; Kavousi, A.; Martínez-Salvador, C.; Reimann, T. Evaluation of inferred conduit configurations in the Yucatan karst system (Mexico) from gravity and aeromagnetic anomalies, using MODFLOW-CFPv2. Hydrogeol. J. 2024, 32, 1363–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, A.; Goldscheider, N.; Wagener, T.; Lange, J.; Weiler, M. Karst water resources in a changing world: Review of hydrological modeling approaches. Rev. Geophys. 2014, 52, 218–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizi, E.; Hosseini, S.M.; Ataie-Ashtiani, B.; Simmons, C.T. Vulnerability mapping of coastal aquifers to seawater intrusion: Review, development and application. J. Hydrol. 2019, 570, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2021: Valuing Water; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000375724 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Li, M.; Najjar, R.G.; Kaushal, S.; Mejia, A.; Chant, R.J.; Ralston, D.K.; Burchard, H.; Hadjimichael, A.; Lassiter, A.; Wang, X. The Emerging Global Threat of Salt Contamination of Water Supplies in Tidal Rivers. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2025, 12, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narvaez-Montoya, C.; Bonilla, R.M.; Goldscheider, N.; Mahlknecht, J. Groundwater salinization patterns in the Yucatan Peninsula reveal contamination and vulnerability of the karst aquifer. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo-Albuerne, A.; Canul-Macario, C. Saline intrusion assessment using the GALDIT index on the northern coast of Quintana Roo, Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. AQUA Water Infrastruct. Ecosyst. Soc. 2024, 73, 1683–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frollini, E.; Parrone, D.; Ghergo, S.; Masciale, R.; Passarella, G.; Pennisi, M.; Salvadori, M.; Preziosi, E. An Integrated Approach for Investigating the Salinity Evolution in a Mediterranean Coastal Karst Aquifer. Water 2022, 14, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S.; Shalev, E.; Sivan, O.; Yechieli, Y. Correction: Challenges and approaches for management of seawater intrusion in coastal aquifers. Hydrogeol. J. 2023, 31, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Ceballos, R.; Pacheco-Avila, J.; Euan-Avila, J.; Hernandez-Arana, H. Regionalization based on water chemistry and physicochemical traits in the ring of cenotes, Yucatan, Mexico. J. Cave Karst Stud. 2012, 74, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ceballos, R.; Canul-Macario, C.; Pacheco-Castro, R.; Pacheco-Ávila, J.; Euán-Ávila, J.; Merino-Ibarra, M. Regional Hydrogeochemical Evolution of Groundwater in the Ring of Cenotes, Yucatán (Mexico): An Inverse Modelling Approach. Water 2021, 13, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.; Anguiano, J.H.H.; Benítez, F.P.; Cruz-Falcón, A.; Miranda-Avilés, R.; Cantú, M.E.M.; Li, Y. Status of seawater intrusion in Mexico: A review. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 57, 102189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosserelle, A.L.; Morgan, L.K.; Hughes, M.W. Groundwater rise and associated flooding in coastal settlements due to sea-level rise: A review of processes and methods. Earth’s Futur. 2022, 10, e2021EF002580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamrsky, D.; Essink, G.H.P.O.; Bierkens, M.F.P. Global impact of sea level rise on coastal fresh groundwater resources. Earth’s Futur. 2024, 12, e2023EF003581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera-Burgos, J.A.; Alvarado-Izarraras, L.G.; Mixteco-Sánchez, J.C.; Canul-Macario, C.; Acosta-González, G.; González-Calderón, A.; Hernández-Anguiano, J.H.; Li, Y. Hydrogeophysical Evaluation of the Karst Aquifer near the Western Edge of the Ring of Cenotes, Yucatán Peninsula. Water 2024, 16, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Bautista, R.M.; Lenczewski, M.; Morgan, C.; Gahala, A.; McLain, J.E. Assessing Fecal Contamination in Groundwater from the Tulum Region, Quintana Roo, Mexico. J. Environ. Prot. 2013, 4, 1272–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.; Velazquez-Oliman, G.; Marin, L. The hydrogeochemistry of the karst aquifer system of the northern yucatan peninsula, Mexico. Int. Geol. Rev. 2002, 44, 191–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer-Gottwein, P.; Gondwe, B.R.N.; Charvet, G.; Marín, L.E.; Rebolledo-Vieyra, M.; Merediz-Alonso, G. Review: The Yucatán Peninsula karst aquifer. Hydrogeol. J. 2011, 19, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, H.E.; Osornio, J.J.J.; Álvarez-Rivera, O.; Medina, R.C.B. El karst de Yucatán: Su origen, morfología y biología. Acta Univ. 2019, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Borges, J.A.; Viveros-Jiménez, F.; Rodríguez-Mata, A.E.; Lizardi-Jiménez, M.A. Hydrocarbon Contamination Patterns in the Cenotes of the Mexican Caribbean: The Application of Principal Component Analysis. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2020, 105, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, D.; Alfaro, E.J. Spatiotemporal variability of the rainy season in the Yucatan Peninsula. Int. J. Clim. 2024, 44, 2561–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uuh-Sonda, J.M.; Gutiérrez-Jurado, H.A.; Figueroa-Espinoza, B.; Méndez-Barroso, L.A. On the ecohydrology of the Yucatan Peninsula: Evapotranspiration and carbon intake dynamics across an eco-climatic gradient. Hydrol. Process. 2018, 32, 2806–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grill, G.; Lehner, B.; Thieme, M.; Geenen, B.; Tickner, D.; Antonelli, F.; Babu, S.; Borrelli, P.; Cheng, L.; Crochetiere, H.; et al. Mapping the world’s free-flowing rivers. Nature 2019, 569, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOF. Ley de Aguas Nacionales Cámara de Diputados del H. Congreso de la Unión Ultima Reforma; DOF: Mexico City, Mexico, 2023; pp. 1–91. [Google Scholar]

- Batllori-Sampedro, E.; Canto-Mendiburu, S.A. Water Balance by Planning Units in the Yucatán Peninsula. J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI. Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales Geológicos. Continuo Nacional. Fallas Fracturas. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825267605 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- INEGI. Continuo de Elevaciones Mexicano y Modelos Digitales de Elevación. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/geo2/elevacionesmex/ (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- CONAGUA. Resultados de la Red Nacional de Medición de Calidad del Agua (RENAMECA). Available online: http://www.gob.mx/conagua/articulos/resultados-de-la-red-nacional-de-medicion-de-calidad-del-agua-renameca?idiom=es (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Vizcaino-Rodriguez, L.A.; Ravelero-Vazquez, V.; Lujan-Godinez, R.; Canul-Garrido, D.M. Cenote Chen ha, and water quality indicators. Ecorfan J. Repub. Nicar. 2022, 8, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogu, R.; Carabin, G.; Hallet, V.; Peters, V.; Dassargues, A. GIS-based hydrogeological databases and groundwater modelling. Hydrogeol. J. 2001, 9, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachadourian-Marras, A.; Alconada-Magliano, M.M.; Carrillo-Rivera, J.J.; Mendoza, E.; Herrerías-Azcue, F.; Silva, R. Characterization of Surface Evidence of Groundwater Flow Systems in Continental Mexico. Water 2020, 12, 2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villasuso-Pino, M.J.; Sánchez y Pinto, I.A.; Canul-Macario, C.; Casares-Salazar, R.; Baldazo-Escobedo, G.; Souza-Cetina, J.; Poot Euán, P.; Pech Argüelles, C. Hydrogeology and conceptual model of the karstic coastal aquifer in Northern Yucatan State, Mexico. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosystems 2011, 13, 243–260. [Google Scholar]

- Palma-López, D.J.; Bautista, F. Technology and local wisdom: The Maya soil classification app. Bol. Soc. Geol. Mex. 2019, 71, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chachadi, A.G.; Ferreira, J.P.L. Assessing aquifer vulnerability to seawater intrusion using GALDIT method: Part 2—GALDIT Indicators Description. IAHS-AISH Publ. 2007, 310, 172–180. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI. Edafología. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/edafologia/ (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- FAO. 2009. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/as360s/as360s.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- INEGI. Continuo Nacional de Aguas Subterráneas; Escala 1:250 000 Serie II; INEGI: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2003; Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=889463598411 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Escolero, O.A.; Marin, L.E.; Steinich, B.; Pacheco, A.J.; Cabrera, S.A.; Alcocer, J. Development of a Protection Strategy of Karst Limestone Aquifers: The Merida Yucatan, Mexico Case Study. Water Resour. Manag. 2002, 16, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle-Levinson, A.; Mariño-Tapia, I.; Enriquez, C.; Waterhouse, A.F. Tidal variability of salinity and velocity fields related to intense point-source submarine groundwater discharges into the Coastal Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2011, 56, 1213–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Ramos, E. Estudio Geológico de la Península de Yucatán; Superintendencia de Geología Regional: Mexico City, Mexico, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Canul-Macario, C.A. Dinámica de la Interfase Salina del Acuífero de la Costa Noroeste de Yucatán y Escenarios Frente al Incremento del Nivel Medio del Mar. Posgrado en Ingeniería Civil-Ingeniería de Costas y Ríos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), Mexico City, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, H.; Cardona, A.; Graniel, E.; Alfaro, C.; Castro, J.; Rüde, T.; Herrera, E.; Heise, L. Interfases de agua dulce y agua salobre en la región Mérida-Progreso, Yucatán. Tecnol. Cienc. Agua 2015, 6, 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Stalker, J.C.; Price, R.M.; Rivera-Monroy, V.H.; Herrera-Silveira, J.; Morales, S.; Benitez, J.A.; Alonzo-Parra, D. Hydrologic Dynamics of a Subtropical Estuary Using Geochemical Tracers, Celestún, Yucatan, Mexico. Estuaries Coasts 2014, 37, 1376–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Hernández, A.; Leyte-Vidal, J.J.P.; Romero-Guzmán, E.T.; Rios-Lugo, M.J.; Mondragón-Bonilla, R.; Martínez-Vargas, M.; Martínez-Villegas, N.; Hernández-Mendoza, H. Hydrogeochemical processes and groundwater vulnerability in Yucatán Peninsula cenotes: Insights from Rare Earth Elements and Yttrium (REY) and the DRASTIC model. Sci. Total. Environ. 2025, 995, 180072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade-Gómez, L.; Rebolledo-Vieyra, M.; Andrade, J.L.; López, Z.P.; Estrada-Contreras, J. Karstic aquifer structure from geoelectrical modeling in the Ring of Sinkholes, Mexico. Hydrogeol. J. 2019, 27, 2365–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, G.; Gleeson, T. Vulnerability of Coastal Aquifers to Groundwater Use and Climate Change. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 342–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONAGUA. 2020–2024. In Diario Oficial de la Federación; DOF: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).