Abstract

Ocean acidification (OA) is considered a relevant additional threat to marine biodiversity and is linked to the increasing CO2 concentration in the atmosphere. Here, we provide a synthesis on the loss of both taxonomic and functional biodiversity, in the up to date best studied CO2 vents in the world, the Castello Aragonese of Ischia (Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy), analyzing a large data set available at this site and reporting qualitative taxonomic data along a gradient of OA from ambient normal conditions outside the vents (pH 8.1) to low pH conditions (pH 7.8–7.9) and extreme low pH conditions (pH < 7.4). A total of 618 taxa were recorded (micro- and macrophytes, benthic invertebrates, and fishes). A relevant loss of biodiversity (46% of the species) was documented from control/normal pH conditions to low pH, and up to 56% species loss from control of extreme low pH conditions. Functional groups analysis on the fauna (calcification, size, motility, feeding habit, and reproduction/development) allowed us to draw an identikit of the species which is able to better thrive under OA conditions. These are motile forms, small- or medium-sized, generalist feeders, at the low level of the food web (herbivores or detritivores), mainly brooders, or with indirect benthic development, and without calcification or weakly calcified.

1. Introduction

As the ocean continues to take up carbon dioxide (CO2), the marine water is progressively altering the complex carbonate chemistry, decreasing their mean pH and increasing pCO2 and pH temporal variability, an overall phenomenon known as ocean acidification (OA) []. Experimental studies assessing the potential impacts of ocean acidification on marine organisms have rapidly expanded and produced a wealth of empirical data, and evaluation of the potential risks for the marine biota and society related to this stressor [,,]. Although it is difficult to predict the future impact on marine species, and the modification of communities and ecosystems, since the first reviews and meta-analyses on OA, based initially mainly on laboratory and mesocosm studies (e.g., [,]), the negative effects of this stress forcing factor on the basic life processes of marine organisms, with the exception of the photosynthesis, were clear. From the research, which was mainly conducted under mesocosm experiments, OA negatively affected processes related to calcification, such as reduction in calcareous structures, reduction in calcification rates, and skeletal dissolution, while the other physiological processes involved were metabolic depression, reduction in metabolic activity, interference with oxygen transport to tissue, cellular acid/base equilibrium, reduction in somatic growth, and decreased thermal tolerance. In addition, several influences of reproductive biology were observed, such as a reduction in fertilization and hatching success and an impact on larval development and larval survival [,].

From the late 2000s, naturally acidified systems, such as CO2 vents, started to take a major role in the research scenario assessing the effects of OA at different hierarchical scales of biological complexity, and various reviews have been published summarizing approximately the first 10 years of this in situ research [,,]. Natural CO2 vent systems are shallow areas (above 200 m depth) affected by the emission of gases of volcanic origin, and they are generally rich in CO2, although other gasses can be present (e.g., sulphur, methane). They can be found in areas characterized by underwater volcanic activity, such as mid-oceanic ridges or island arcs, or intra-plate magmatism []. The Mediterranean Sea is rich in different hydrothermal vents systems, including shallow CO2 vents [,]. Here, the pH is generally highly fluctuating, often from normal (8.1) to very acidic conditions, below 6.0 units, and CO2 concentration can reach over 1000–1300 ppm [].

The first vent system studied in the world as regards the effects of OA on the macrobenthic biota has been the Castello Aragonese islet off the island of Ischia [,]. Since this first study, up to date many other CO2 vent systems have been studied in the Mediterranean [,,,,,], as well as around the world (e.g., []), and a few reviews on the research conducted in these systems have been provided as regards the Castello of Ischia [], the boreal northern areas [], the Mediterranean Sea [,], and other zones [].

Natural CO2 vent sites can mimic near-future scenarios of OA and the variability of the pH and carbonate chemistry alterations, often providing a pH gradient that can be considered as a proxy to investigate the ecological effects of ocean acidification []. As natural laboratories, CO2 vent sites incorporate a range of environmental factors, such as gradients of nutrients, water currents, and species interactions, that cannot be replicated in the laboratory or mesocosms, with the caveat that some vent systems may have confounding factors such as hydrogen sulphide and/or metals (e.g., []). The effects of pH decreasing can be assessed at increasing levels of organization, analyzing responses from species to populations, communities, and ecosystems. Biodiversity, both expressed as taxonomic diversity and the functions of such species, is an intrinsic property and value of the natural communities and largely contributes to the main services that ecosystems provide to human beings and society. From research up to date conducted in various vents systems, since OA is deeply altering habitat health [], a general decrease in taxonomic biodiversity has been highlighted in various vents systems, in temperate as well as tropical systems [,,,,]. The biodiversity loss is mainly due to the reduction in heavy calcified taxa, such as coralline algae, hard corals, mollusks, and echinoderms, while macrophytes, especially seagrasses and fleshy algae, seem less affected and somehow favoured by OA conditions [].

As regards the functional aspects, a few studies at the Castello and other vents systems have attempted an analysis of functional features, although these studies were limited to specific groups (e.g., polychaetes, []) or address only a specific trait such as the type of reproduction and egg development (e.g., []), adult size (e.g., []), or trophic relationships (e.g., [,]). To this respect, a recent seminal study was conducted at the Castello vents system by [], focusing on the functional traits approach [] of benthic organisms of the rocky shallow bottom (mainly macroalgae and a few sessile invertebrates). The functional diversity of sessile benthic assemblages was assessed using 15 traits in 72 species, resulting in 68 unique functional combinations. The research highlighted that the functional loss is more pronounced than the corresponding decrease in taxonomic diversity. Moreover, most organisms accounted for a few functional entities (i.e., unique combination of functional traits) and the consequent low functional redundancy under acidified conditions. This kind of study and approach was recently applied to other vents systems off the Ischia Island [], still considering the hard bottoms assemblages. This study revealed a common trend, as regards to the reduction in calcified taxa, and habitat simplification by reduction in habitat forming species (e.g., gorgonians, bryozoans), but also a different importance of grazing and grazers, which is more represented in algal dominated vents, with respect to the filter feeders which are more relevant instead in animal dominating vents, such as the Coralligenous outcrops [].

In addition, the Castello vents system allowed us also to pioneer new approaches to study the effects of this climate-related stressor on the eco-physiology of Mediterranean species and their acclimation and adaptation mechanisms to the unique acidified conditions (reviewed in []). The paper of [], in particular, provides not only a general overview of the research carried out in the Castello vents in the past years, but includes also a first check-list of the species recorded in this naturally acidified area, and also the nearby control zones prior to the start of vents studies, allowing a census of more than 600 species, considering micro- and macrophytes, motile and sessile invertebrates, and fishes. However, a general assessment of the trend of this whole and large data set was never performed, and published information is related to single benthic plant or animal components/groups, or a single habitat, giving a partial view of the whole diversity of the vents system. Although the Castello vents show limited geographic and spatial extension, they host habitats such as shallow hard bottoms and Posidonia oceanica seagrass meadows, which represent among the most common and extended ecosystems of the Mediterranean Sea, so that the effects of OA observed in the species inhabiting these habitats may have a far-reaching significance. The aim of the present work is to perform a general assessment and synthesis of the trends of both taxonomic and functional biodiversity, along the gradient of OA occurring on both sides of the Castello vents system, and in the two main habitats inhabiting the vents, considering the whole set of species recorded in the area during various studies, to quantify the overall loss of biodiversity as well as highlight some general functional traits patterns, across different taxa, which may have positive, neutral, or negative adaptive significance under future OA conditions of the oceans. A check-list of species occurring in the area, updated to 2024, together with their location along the gradient, their habitat occurrence, and the study reference where they have been collected, is also provided.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

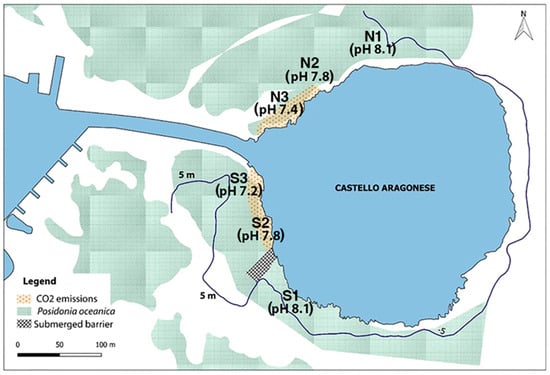

A good description of the CO2 vent system around the Castello Aragonese off Ischia (40°43′53.31″ N; 13°57′46.93″ E) is available in previous papers [,,]. To synthesize the main features of this vents system, it is worth mentioning that 95% of the gas is composed of CO2 and no toxic gases are present [] and also that there is no metal contamination since their concentration is within the natural surrounding background of the Ischia Island [,]. The pCO2 in the most intense venting areas is above 1300 ppm. Both in the north and south side of the Castello islet (Figure 1), a clear gradient of pH is formed by different CO2 venting intensities which provoke a different lowering and variability of the pH. Three pH areas were defined as follows: extreme low pH zones (mean pH < 7.4) (indicated as stations S3 south and N3 north in previous papers, e.g., []), low pH zone (pH at 7.8–8.0) (indicated as S2 south and N2 north stations in previous papers), and ambient areas with no bubbling and normal pH conditions (mean pH 8.1) (indicated as S1 south and N1 north stations in previous papers). The vents and the control area are distributed, both on the north and south sides, from 2 to 3 m depth, along about 200 m coastline on the north and 150 m on the south side. The OA gradient is continuous and therefore no clear boundaries or discontinuity between the three areas can be traced and defined, so that the three zones are established based on the more uniform conditions, and are separated by approx. 20 m gaps from each other.

Figure 1.

Map of the Castello Aragonese islet (island of Ischia; 40°43′53.31″ N; 13°57′46.93″ E) in which are indicated the pH zones on the north and south side. N1–S1 normal pH zone out of the venting areas; N2–S2 low pH zone, intermediate venting areas; N3–S3 very low pH zone, high venting area. The blue line represents the 5 m depth bathymetry.

2.2. Methods

In order to estimate the overall species richness recorded in each zone, we synthesized available data containing taxonomic and ecological information on species occurrence in the Castello Aragonese area, and nearby zones (approx. 300 m from the Castello islet) from 1950 to 2007 (31 papers), and in studies conducted on the vents from 2008 to 2024 (38 papers) (see Table S1 for the whole reference list). The publications examined include regular scientific papers, grey literature such as PhD theses, master theses, and data reports, as well some unpublished personal data (e.g., on polychaetes), for a total of 69 documents (Table S1). Each study containing taxonomic information (qualitative or quantitative) was considered regardless of the period of collection of the data, and the sampling methods adopted, so that only the spatial information on taxa occurrence and distribution is here considered to evaluate the overall biodiversity recorded in each of the considered pH areas over the years. The taxonomic information on which we base our analyses consists of various quantitative studies on different habitats, mainly vegetated hard bottoms and seagrass beds, adopting different sampling methods, e.g., hard bottoms by scraping [,] or seagrass beds by using an air-lift sampler []. Studies considering artificial substrates (floating artificial collectors or mimics of Posidonia oceanica shoots) in both hard bottoms ([,]) and seagrasses [,] were also part of the data set, as well as qualitative studies where only species presence/absence is reported in one or more of the different pH zones and vents sides (e.g., [,]). We are aware that this may have some bias due to differential sampling efforts exerted in various habitats (hard bottoms more sampled than seagrasses), or taxonomic groups (polychaetes more studied than other invertebrates), and to seasonality (many algal species occurrence related to different time of the year); however, our goal was to census and list in each of the pH areas considered the species that at least once have been documented, to highlight to maximum potential species richness of that area.

When in a document a species was recorded but its exact location in the Castello area was not indicated, the species were not included in the check-list and in the further statistical analyses related to the OA gradient. This is the case of 11 species of Mysidacea (Crustacea, Arthropoda), considered, however, in the check-list provided by []. With respect to this previous check-list prepared in 2018 [,], we have updated the data set with more recent studies; however, we have also emended in the list most of the not well identified species, so that our final result consists of 618 taxa, with respect to the 633 listed in previous versions [,]. We have also updated the species names according to the WoRMS: World Register of Marine Species 2020 []. Finally, we have performed an analysis based on the two main habitats of the area, and documented in the available literature: seagrass meadows (Posidonia oceanica and a nearby Cymodocea nodosa) and shallow vegetated rocky reefs around the Castello coast. Various species records arising from artificial settlement structures, such as scouring pads and mimics of Posidonia oceanica shoots, have been assimilated to hard bottoms and Posidonia meadows, respectively. The few data related to soft bottoms are limited to Foraminifera ([], see Table S2), and to a single study conducted in a Cymodocea nodosa bed [], so that the analysis of this habitat was not performed.

Species records were evaluated in three pH zones: normal/ambient conditions (pH = 8.10–8.12) (outside/far from the CO2 bubbling areas, approx. 150–200 m from the more intense venting areas), low pH (mean pH 7.9–7.6) (modest CO2 bubbling), and extreme low pH (mean pH 7.4–6.9) (intense CO2 bubbling) (Figure 1), and for each pH zone the species’ records on the north and/or south side of the Castello were distinguished.

As for the functional analyses, only the fauna was considered since a functional traits analysis on phytobenthos of the hard bottoms, and a few sessile invertebrates (for a total of 72 taxa), has been already made available by []. While polychaetes have been previously studied at the vents in their functional make up [], for all the other invertebrate groups this represents the first analysis and a first attempt to summarize functional aspects on such a wide taxonomic range. Each invertebrate and fish species was defined within the feeding category considering the type of food consumed and the modality of feeding. This was accomplished according to the knowledge on the species ecology based on the literature and for some groups by verifying this information with the opinions of experts of the taxonomic groups considered (see Acknowledgments). As a whole, 8 trophic categories were considered: herbivores both feeding on micro- and macroalgae (many mollusks and polychaetes), detritivores (many peracarid crustaceans, polychaetes, and decapods), omnivores (some polychaetes), suspension feeders (sponges, bryozoans, tunicates, and various polychaetes), detritivores/suspension feeders (organisms with a mixed strategy, such as various amphipods), carnivores (mollusks, polychaetes, most fishes), and parasites. We assumed that the trophic habit of each species remained unchanged along the OA gradient. According to the motility, taxa were grouped in three categories: vagile/motile (e.g., small peracarid crustaceans, mollusks, and polychaetes), sedentary forms (e.g., limpets), and sessile (e.g., serpulid polychaetes, barnacles, bryozoans). The species were also divided according to their size ranges based on the adult maximum size recorded in the literature: less than 1 cm (small), between 1 and 5 cm (medium), and larger than 5 cm (large); in addition, the main reproductive and developmental modes were scored as “indirect planktic”, when external fertilization and free spawning is involved and a larva with a variable duration in the plankton or near the bottom is present; “indirect benthic”, when the development is including a larval stage with some pelagic life period, but the eggs are deposited in the benthic environment as capsules (e.g., many mollusks) or gelatinous masses (mollusks, fishes) or are incubated for a period inside the adult body (e.g., various sponges and bryozoans); and “direct” when a species is incubating the broods and a juvenile is directly coming out of the eggs (e.g., many brooders’ polychaetes).

Lastly, the species were also grouped according to degree of calcification in three main categories: calcified (mollusks, echinoderms), weakly calcified (crustaceans), and not calcified (most polychaetes).

2.3. Data Analyses

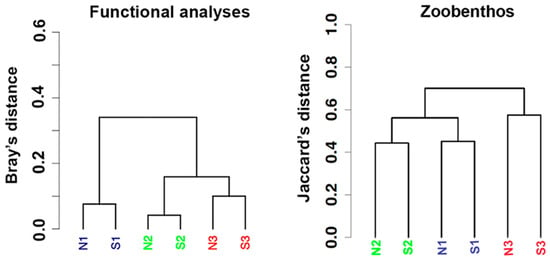

Number of taxa of each taxonomic group or functional guild was plotted along the northern and southern OA gradients in order to show relative reduction or increase in each group in the different pH zones. The same was carried out with the species belonging to the various functional categories considered. Count tables (visualized as bar plots) and distance in terms of species diversity analyses (dendrograms based on Jaccard distance on species presence/absence matrices per site) were used to summarize the taxonomic data set and to compare the different stations along the OA gradient. As for the analysis of functional groups, we used the number of species of each of the functional groups (8) and their different states (20) that have been counted in each of the stations, building the cluster based on the Bray–Curtis distance, instead of Jaccard distance, as this analysis targeted the number of species belonging to each guild for each station, rather than their presence/absence. The patterns of similarity among samples obtained with the cluster analysis were verified with the PERMANOVA to statistically test whether the resulting groups differed significantly in their multivariate composition [].

All analyses were performed in the free software environment R (R version 4.5.2, released 2025-10-31), using the base and stats packages [].

3. Results

3.1. Taxonomic Analyses

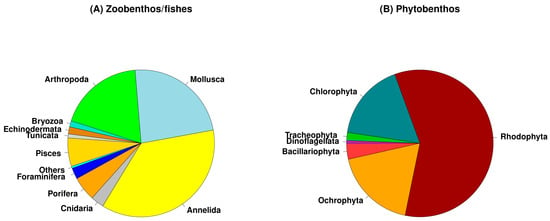

Taxonomic information on the Castello area was collected from 69 papers, listed in Table S1, for a total of 618 species recorded in the whole area: 416 zoobenthic species (including Foraminifera), 32 fishes, and 170 micro- and macrophytes (Figure 2). Overall, among the animal organisms, Mollusca and Annelida (polychaetes) are the most represented group followed by Arthropoda (various classes of crustaceans) in the zoobenthos (Figure 2A), while the phytobenthos was characterized by a clear dominance of Rhodophyta followed by Chlorophyta and Orchophyta (Phaeophycee) with a similar species richness (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Taxonomic composition of higher groups of the zoobenthos (A) and phytobenthos (B) recorded in whole Castello vents and off vents areas. The percentages represent the number of species of each taxonomic group occurring in the whole data set (448 taxa for zoobenthos and fishes; 170 taxa for phytobenthos).

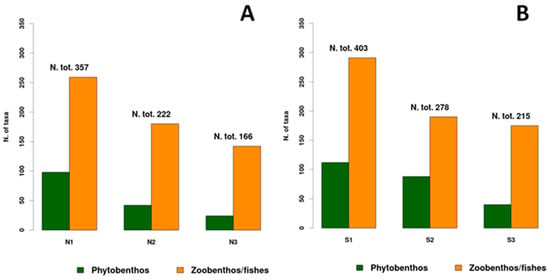

Proceeding along the OA gradient, it is possible to observe a decrease in total species richness. In particular, the ambient area (N1 and S1) includes 505 taxa (81% of the whole data set of 618 species), the intermediate area (N2–S2) includes 336 species, corresponding to 54% of the whole data set, while the extreme low pH area (N3 and S3) includes 275 taxa (44%). Therefore, there is a loss of biodiversity of about 46% passing from ambient to low pH and of about 56% from ambient to extreme low pH.

This trend is present in both the zoo- and phytobenthos which showed a decrease in the number of taxa, higher in the phytobenthos (Figure 3). Analyzing separately the northern and southern areas, both the components showed a higher diversity in the southern area, especially the zoobenthic/fish taxa. Moreover, the trend of species richness which decreases proceeding from the ambient to the extreme low pH conditions is highest in the phytobenthos, especially in the northern area (Figure 3). The decrease in both zoobenthos/fish and phytobenthos biodiversity is evident both in the north and south stations, proceeding towards the low pH areas (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A trend of number of taxa of phytobenthos and zoobenthos/fishes on the north (A) and south (B) stations along the OA gradient: N1–S1 ambient pH zones; N2–S2 low pH zones; N3–S3 extreme low pH zones.

Among the animals, it is worth mentioning the occurrence of new species first described in the Castello vents areas, including an acoel worm (Philactinioposthia ischiae, []), two fabriciid polychaetes (Brifacia aragonensis, Fabrikinkia mazzellae; []), and one sabellidae (Amphiglena aenariensis, []), and a P. oceanica boring isopod (Limnoria mazzellae, []). In addition, eight aliens, introduced species, have been recorded at the vents, as a toxic dinoflagellate Ostreopsis ovata [], two macroalgal species (Caulerpa cylindracea and Asparagopsis taxiformis), three polychaetes (Lysidice collaris, Branchiomma boholensis, and Novafabricia infratorquata), and two crustaceans (Mesanthura sp. and Percon gibbesi) ([], Tables S2 and S3).

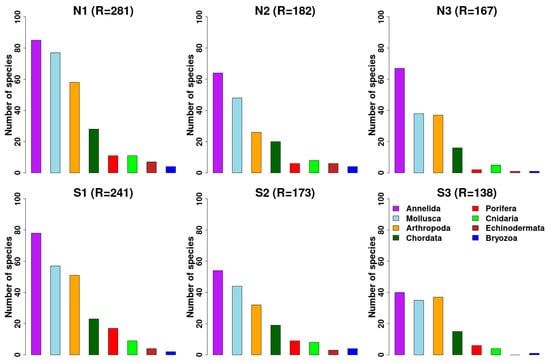

3.2. Zoobenthos and Fishes

A total of 448 taxa were recorded in the zoobenthos and fishes: Mollusca (105), Annelida (164), Crustacea (Arthropoda) (84), of which Amphipoda and Decapoda are the most speciose groups with 46 and 22 taxa, respectively, Porifera (24), Cnidaria (13), Foraminifera (11), Bryozoa (6), Echinodermata (7), Chordata (fishes) (32), and a single taxon for Entroprocta and Acelomata (Table S2). The species diversity reduction is different in the different groups from 27% of taxa lost in Peracarida crustaceans (amphipods, isopods, tanaids) to 78% for echinoderms. Although the trend of decreasing species is observed in all groups, the north side area is richer especially in the groups of annelids, mollusks, and arthropods. The other groups show relatively low biodiversity to highlight a clear pattern, except for sponges and bryozoans which show a strong decrease from ambient to extreme low conditions especially on the north side (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Trend of the number of species of various zoobenthic taxonomic groups in the north and south side stations along the gradient of OA: N1–S1 ambient pH zones; N2–S2 low pH zones; N3–S3 extreme low pH zones.

Among the most abundant groups (Annelida, Mollusca, and Crustacea), showing the least decrease, the annelid polychaetes remain the most abundant group even in conditions of extreme acidification especially in the southern area (Figure 4). By contrast, Crustacea (Artropoda) show a decrease in the intermediate areas and a new increase in the most acidified ones. Annelida are also one of the best studied groups concerning the distribution of the species along the gradient [,,].

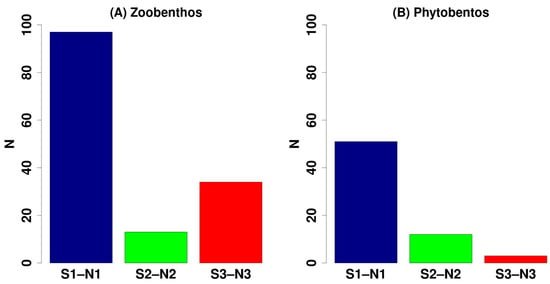

As a whole, the differences among the ambient areas and the acidified ones were due especially to the disappearance of taxa proceeding along the OA gradient, even if 38 animal species were exclusive of the most acidified areas, representing 6% of the total biodiversity (Table S2). In Figure 5 is shown the number of taxa exclusive of the different areas. The highest number of exclusive animal species, 98, is found in the ambient area, 16 species in the intermediate area, and 37 taxa occurred only in the most acidified zone. In particular, most of these exclusive taxa of the most acidified area are polychaetes (24 taxa) among which several Fabriciidae species were exclusive of the acidified areas, including the taxa news for the sciences: Brifacia aragonensis and Fabrikirkia mazzellae, but also Pseudofabricia aberrans, Pseudofabriciola analis, and Rubifabriciola tonerella, normally present in hard bottom communities and not linked to a specific habitat. Other exclusive taxa of the most acidified zones belong to mollusks (6 taxa) and amphipods (8 taxa). No exclusive fish species were observed in the most acidified areas.

Figure 5.

Number of species which have been exclusively found only in one of the 3 pH zones of the Castello vents pooling data from the north and south sides: (A) zoobenthos; (B) phytobenthos; S1–N1: control stations; S2–N2: low pH stations; S3–N3: extreme low pH stations.

3.3. Phytobenthos

A total of 170 taxa of phytobenthic species were found: Rhodophyta (100), Ochrophyta (31), Chlorophyta (29), Bacillariophyta (6), Tracheophyta (3), and Myzozoa (1); see Table S3 for the whole data set.

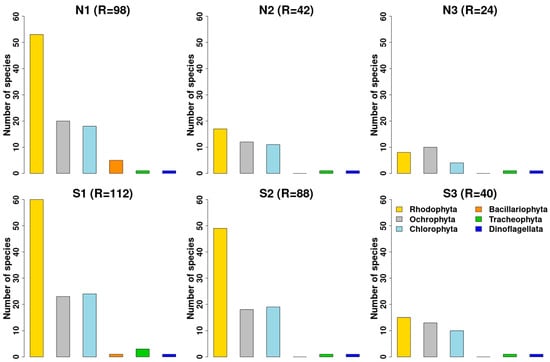

As occurs for zoobenthos, the phytobenthos show a general decrease in all the different groups from ambient to extreme low pH conditions (Figure 6). The ambient areas off the vents (N1 and S1) host 149 taxa (88% of the whole data set), the N2 and S2 stations host 96 taxa (56%), while the extreme low pH area (N3 and S3) host 49 taxa (29%).

Figure 6.

Trend of the number of species of various taxonomic groups of phytobenthos in the north and south stations along the gradient of OA: N1–S1 ambient pH zones; N2–S2 low pH zones; N3–S3 extreme low pH zones.

The Phaeophyceae (brown algae, Ochrophyta) are proportionally more represented in the most acidified zone (where some species are exclusive, e.g., Sargassum vulgare), especially in the northern area. The Rhodophyta (red algae) are dominating the ambient conditions in both northern and southern sides and also the category that shows a more pronounced decrease (82%) towards the extreme low pH conditions, and this is surely related to the dominance in this taxon of calcareous forms (e.g., Jania rubens, Corallinales). The Chlorophyta (green algae) are relatively constant along the OA gradient, and the Bacillariophyta (diatoms) are represented especially in N1 and exclusively found as epiphytes on Posidonia oceanica leaves (Figure 6).

As concerns the taxa exclusive of the different areas along the gradient, the phytobenthos show a constant decrease proceeding from ambient to acidified conditions (Figure 5B), and only four species are exclusive of the extreme low pH zone: Sargassum vulgare, Chondracanthus acicularis, Ethelia vanbosseae, and Gelidium pusillum.

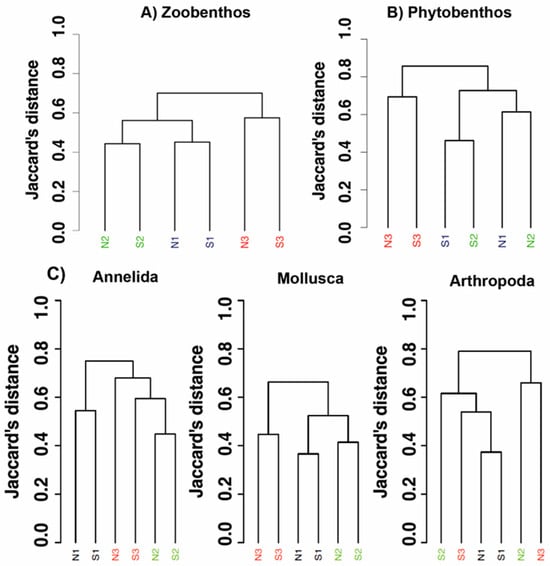

The cluster analysis conducted on the assemblages, cumulative for the north and south side stations, shows for the zoobenthos a sharp separation between the most acidified zone (N3–S3) and the cluster containing low and ambient pH sites (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Dendrograms of station similarity (based on Jaccard’s distance) related to the analyses of the zoobenthos/fishes (A), phytobenthos (B), and of some speciose groups of the zoobenthos: Annelida, Mollusca and Arthropoda (crustaceans) (C). black: N1–S1 ambient pH zones; green: N2–S2 low pH zones; red: N3–S3 extreme low pH zones.

However, even in this latter cluster a clear separation between low pH and ambient conditions is observed (PERMANOVA pseudo-F = 1.9, p-value: 0.07). The dendrogram relative to the analysis of the phytobenthos (Figure 7B) reveals still a strong separation of the extreme low pH zones (N3–S3) from the other areas, while the sites N1–S1 and N2–S2 show a separation among the two sides, north vs. south sites, rather than among pH conditions (PERMANOVA pseudo-F = 4.6, p-value: 0.11). Dendrograms obtained from the analysis of some zoobenthic groups, separately, revealed that Mollusca mirrored exactly the same pattern obtained with the analysis of the whole benthic community (PERMANOVA pseudo-F = 3.6, p-value: 0.07), while Annelida showed the ambient stations separated while low and extreme low pH stations are more similar (PERMANOVA pseudo-F = 1.5, p-value: 0.13). Finally, the Crustacea (Arthropoda) showed ambient stations closer to the south side acidified stations, and north side stations separated (PERMANOVA pseudo-F = 2.4, p-value: 0.07) (Figure 7C).

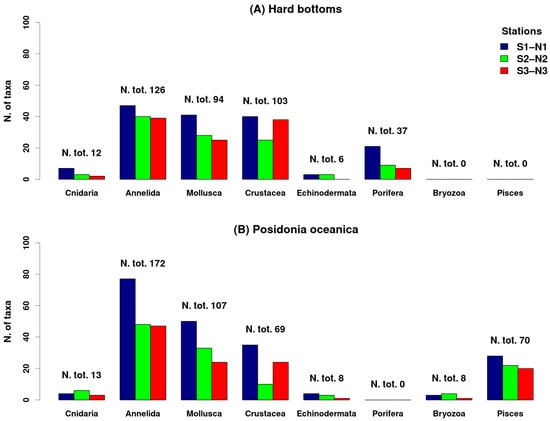

An ecological comparison was performed between the two main habitats occurring in the Castello area, the hard vegetated bottoms and the Posidonia oceanica seagrass (Figure 8). We compared only the trend of the zoobenthos/fish, excluding the phytobenthos, since only 15 plant taxa were recorded in the seagrass (mainly diatoms epiphyte on the seagrass leaves), while most of the phytobenthic species (155) occurred only in the hard bottoms.

Figure 8.

Trend species richness of various groups of zoobenthos/fishes in the two main habitats of the Castello vents: vegetated hard bottoms (A), and seagrass Posidonia oceanica beds (B). N1–S1 ambient pH zones; N2–S2 low pH zones; N3–S3 extreme low pH zones.

As concerns animals, Porifera occurred only in the hard bottoms, Bryozoa and Pisces were studied, and therefore recorded, only in the seagrass, while all the other animal groups occurred in both habitats.

Posidonia oceanica seagrass beds support higher animal diversity with respect to hard bottoms; in fact, in N1–S1 we have 159 species in hard bottoms vs. 201 in seagrass, in N2–S2 108 vs. 126, and in N3–S3 111 vs. 120. In both habitats, dominated by Polychaeta, Crustacea, and Mollusca (Figure 8), the biodiversity decreases along the gradient from ambient to extreme low pH areas; however, between low and extreme low pH areas there is not much difference in species richness. On the contrary, in both habitats Crustacea increase in biodiversity between low and extreme low pH conditions (Figure 8).

3.4. Zoobenthos Functional Analyses

Here, we report the outputs of the analysis of each of the five functional categories studied: calcification, feeding guilds, motility, size, and reproductive/development mode.

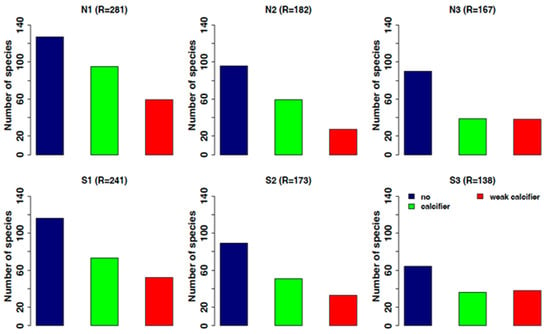

3.4.1. Calcification

Among the examined functional features, the calcification is probably the most important as regards the responses to OA. Calcified and weakly calcified organisms are showing a decrease in the most acidified stations, especially in the north side station (N2–N3) with 60% of the species disappearing in N3, against the 30% of non-calcified organisms (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Trend of species distribution according to their degree of calcification: in blue, non-calcifiers; in green, calcifiers; in red, weak calcifiers. N1–S1 ambient pH zones; N2–S2 low pH zones; N3–S3 extreme low pH zones.

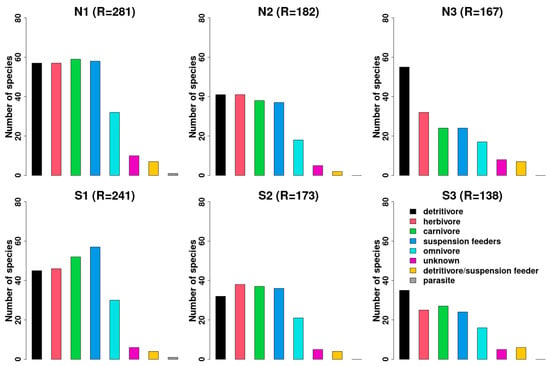

3.4.2. Feeding Guilds

A complex trophic organization is present when examining the feeding categories (Figure 10). All the main categories (suspension feeders, detritivores, herbivores, and carnivores) are well represented in “ambient” conditions in both the north and south sides, even if suspension feeders are the dominant group, especially in the south side. In both sides, all the categories decrease with the decreasing pH, although detritivores remain quite constant and around 25–30%.

Figure 10.

Trend of number of species according to the different feeding guilds identified. N1–S1 ambient pH zones; N2–S2 low pH zones; N3–S3 extreme low pH zones.

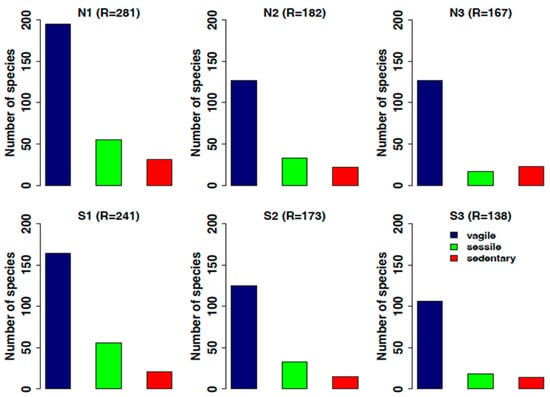

3.4.3. Motility

Considering motility, the motile organisms are always the best represented category in all stations (Figure 11). All the categories tend to decrease in number of species both in the north and south sides from ambient to extreme low pH, especially sedentary and sessile organisms, and considering the calcifiers’ forms, which reduce by 80% if sessile.

Figure 11.

Trend of species distribution according to the different motility categories identified: in blue, vagile/motile organisms; in green, sessile forms; in red, sedentary forms. N1–S1 ambient pH zones; N2–S2 low pH zones; N3–S3 extreme low pH zones.

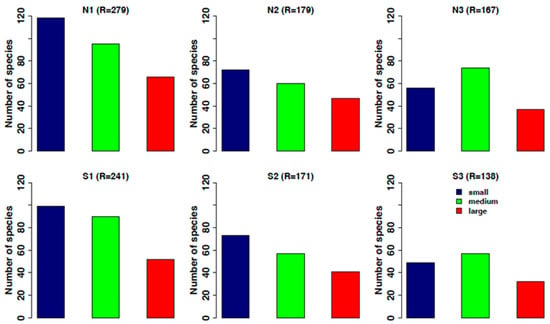

3.4.4. Size

The small-sized species are best represented in the whole data set. All size classes decrease along the gradient of OA from ambient to extremely low pH, and in the most acidified zones both on the north and south sides, the medium-size class is slightly higher than the small-size one (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Trend of species distribution according to the different size categories identified: in blue, small-sized organisms; in green, medium-sized; in red, large sized. N1–S1 ambient pH zones; N2–S2 low pH zones; N3–S3 extreme low pH zones.

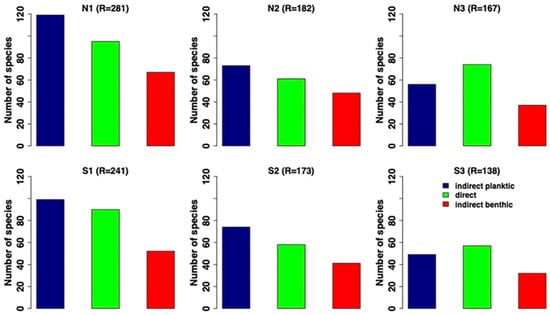

3.4.5. Reproductive/Development Mode

The examination of reproductive features, highly related to the size of the organisms [], showed that the taxa having indirect development diminished toward the acidified conditions. By contrast, direct development (brooding), that usually is linked to a smaller size, seems to be favoured in the acidified conditions in both the south and north sides (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Trend of species distribution according to the different reproductive categories identified: in blue, indirect planktic; in green, direct/brooders; in red, indirect benthic. N1–S1 ambient pH zones; N2–S2 low pH zones; N3–S3 extreme low pH zones.

Examining the trend of all the functional traits pooled together, the dendrogram shows the low and extreme low pH stations clustering closer to each other and well separated from the ambient ones (N1–S1) (PERMANOVA pseudo-F = 7.8, p-value: 0.07). This pattern is slightly different to that obtained examining the whole zoobenthic assemblage from a taxonomic point of view (PERMANOVA pseudo-F = 1.9, p-value: 0.07) where ambient and low pH stations were closer and separated from the extreme low pH ones (Figure 14 vs. Figure 7A).

Figure 14.

Cluster analyses based on all zoobenthic functional groups (left), compared with cluster analysis based on zoobenthic species’ presence/absence (right) as reported in Figure 7A. black: N1–S1 ambient pH zones; Green: N2–S2 low pH zones; red: N3–S3 extreme low pH zones.

4. Discussion

This study represents a synthesis on the distribution of benthic organisms and fish along a gradient of ocean acidification, considering a large bibliographic and unpublished data set of species recorded in the well-studied area of the CO2 vent system of the Castello Aragonese at Ischia. This area has been studied even before the start of the studies on the vents (from 2006; []), which in the early 1980s and up to the middle of the 1990s showed modest bubble emission on the south side, and no bubbles on the north side []. Therefore, the pattern we see both on the intermediate (low pH) and highly acidified areas (extreme low pH) is the result of approx. 25–30 years of more extended and intense bubbling.

Our overall results show how the assemblages, as the pH decreases, are characterized by an overall reduction in the number of species in all the taxonomic components of zoo- and phytobenthos. This trend is similar when considering the two main habitats occurring in the area, vegetated hard bottoms and Posidonia seagrass meadows. The decrease in the number of species along the OA gradient (both north and south sides) concerns 46% from the control/ambient area to low pH and of 56% from the control/ambient area to extreme low pH zones. The cluster analyses highlight a clear separation among pH areas, although this pattern may be influenced by those species occurring only in a single station/area. In the zoobenthos, the ambient area was characterized by the highest number of species exclusively found in this zone (120), while the intermediate area was characterized by the lesser number of exclusive species (20), as well as by taxa able to survive and thrive under moderate OA conditions, while in the extreme low pH zone only the more robust taxa are not selected against the OA conditions, 38 of which are exclusively found here.

The disappearance of taxa proceeding along the OA gradient is interpreted as a selection against the acidification stress. However, the vents are open systems and therefore species from the surrounding control areas can potentially colonize such zones. Many species, in fact, are common between the acidified and the control areas, while some occurred only in the acidified areas and not in the controls. However, these numbers represent a modest proportion and are not relevant to make up a different assemblage, so that the community in the vents can be considered a simplified version of that occurring in the control areas, without a species replacement. We may hypothesize that if bubbling intensity reduces, and consequent acidification decreases, more species may be able to colonize such areas. On the contrary, an intensification of bubbling may lead to lower pH, a more critical condition that may further select the range of species able to survive up to the potential desertification of the area.

Among animal organisms, the mollusks are those showing a pattern more similar to that obtained examining all the zoobenthos, and have been mainly recorded as associated with Posidonia both in natural meadows [], as well as in artificial structures placed in the meadows []. Although they are strong calcifiers, often presenting corrosion of the shells [,,], they are relatively present in the most acidified zones, probably due to the buffer effects on the low pH due to plant photosynthesis, especially in Posidonia []. The buffering action of Posidonia, as well as other seagrasses, on the low pH has been recently highlighted [,].

The polychaete annelids were the more speciose group, remaining quite diverse also in the most acidified areas especially on the south side, where the cover of the macrophytes is higher due to more favourable light conditions [], and they also showed a pattern quite similar to that of the whole zoobenthic fauna. Annelid polychaetes were the better studied group of invertebrates in the Castello vents [,,,] underlined as most taxa were represented with few individuals, and only 15 of the 83 taxa exceeded 1% of the total abundance. Overall, abundances also appeared lower in extreme low pH zones, although this trend was less marked than that of species richness []. This is because some taxa responded differentially, due to an increased competitive ability under these extreme conditions. The Serpulidae, having calcified tubes, were less abundant in low pH and absent in the extreme low pH zones, except in Posidonia []. Conversely, some of the remaining dominant taxa showed relatively high, uniform abundances along the pH gradient, including the most acidified areas, thus demonstrating some degree of tolerance to OA. The Crustaceans, mainly represented by Amphipods and Decapods, show an interesting pattern, being the organisms that seem more robust to OA, and showed a higher number of species in the extreme low pH (N3–S3) than in low pH areas (N2–S2), both in the hard bottoms and in Posidonia (Figure 8). To explain this pattern, we may consider that crustaceans are weakly calcified and highly motile, more than mollusks or polychaetes, so they can be more tolerant to the effects of OA as pointed out also by some transplant experiments conducted with isopods in the vents []. Therefore, their higher biodiversity and abundance in the extreme low pH zones can be due to reduced competition with other taxa and higher availability of food resources (macrophytes), since most species are herbivores or detritivores.

The pattern of distribution of the main animal taxonomic groups observed at the Castello vents is similar to that observed in other vents systems off the island of Panarea, characterized by vegetated hard bottoms (brown algae), where a similar general reduction was observed in mollusks and polychaetes moving from control to low pH zones [].

Within phytobenthos, the Rhodophyceae, the most represented group in the ambient area, is the most sensitive group to OA due to the presence of various calcified species (e.g., Jania rubens and various Corallinales epiphytes on Posidonia leaves), as stressed by [].

Both zoobenthic and phytobenthic components were highly descriptive of the OA gradient; however, while animals show a separation among different pH zones, the phytobenthos show in the acidified stations a side-effect distinguishing north and south stations rather than pH zones. This can originate from the different light regimens of the two Castello sides; the south side of the Castello is more exposed to day light than the north side, so plants respond primarily to light conditions rather than to pH ones.

When the whole animal data set was analyzed according to distribution in the two main habitat types occurring in the area, seagrasses and vegetated rocky reefs, the analyses indicate a higher biodiversity on Posidonia meadows, although hard bottoms have been more intensively studied. This is probably also due to the higher habitat complexity and the higher buffer effect exerted by the Posidonia canopy, with respect to macroalgae [].

As regards the functional traits analyzed, although various strong and weak calcifiers are still able to thrive under OA conditions, calcification seems to be one of the factors selecting against the low pH conditions. A reduction was in fact observed in all groups containing calcifying species, confirming what has been recorded in previous studies [,,,], as well as in various other vent systems [,,,]. A functional selection is also evidenced considering the feeding analysis, although all feeding categories were represented along the whole gradient. We observed a general decrease in all categories, meaning that the functional redundancy is much reduced under acidified conditions, so that the whole food web is reduced in complexity. The assemblages under OA conditions seem to be dominated by herbivores linked to the vegetated cover and abundant epiphytes on the Posidonia leaves, and generalist detritivores. The reduction in carnivores observed under OA conditions indicates a less structured community and a simplified food web in the low pH zone, as observed in polychaetes [] and in the vent system off Vulcano []. The lower redundancy and trophic simplification observed under OA conditions are negatively altering the potential resilience of the assemblages, especially coupled with the occurrence of other potential stressors acting in this area, such as warming (heat-waves), or eutrophication. Heat-waves have been documented often at the island of Ischia [], and their effects on some organisms in the vents were observed during transplant experiments with bryozoans [] and mollusks []. The effects of “induced” eutrophication (nutrient enrichment) were investigated only as regards the production of Posidonia oceanica []; therefore, the influence of other potential stressors, besides OA, has been yet scarcely addressed in this vents system and surely deserve specific investigations.

The reproductive mode shows a clear trend with the relative increase in direct brooders from ambient to extreme low pH, that together with the indirect benthic/brooder constitutes approx. 75% of the species in the area. The size also shows a clear pattern with the prevalence of medium- and small-sized species towards the extreme low pH zone, where they constitute approximately 3/4 of the total. Small and medium size can be related to the occurrence of macroalgae and Posidonia seagrass in the vents, where small organisms can better find shelter and a cryptic habitat. In addition, reduced sizes in various species (dwarfism) have been observed at the Castello [], including Posidonia shoots ([,], as well as in other vents systems such as at Vulcano at species level [,] and at community level in the vents of Panarea and La Palma (Canary Islands) [,].

Reproductive mode is highly correlated with size, with small size not allowing the production of many small eggs typical of the pelagic development []. The pattern arising from the Castello vents system confirms what is reported, in general, for life under OA conditions. It is suggested that the impact of ocean acidification will be more relevant for the earlier life history stages than for the later life history stages and adults, influencing dispersal, settlement, and post-settlement survival, especially for mollusks and echinoderms [].

Finally, motile species dominate all along the gradient, and sedentary and sessile species tend to decrease more than motile species under OA conditions, especially when considering sessile calcifiers, which are reduced by 80% under extreme low pH conditions. So, high motility, as suggested also by the distribution of small crustaceans and also fishes in extreme low pH areas, seems to be an important trait to thrive under OA conditions. Since most sessile animals are often habitat formers, arborescent, or massive (e.g., gorgonians, sponges, and bryozoans), the reduction in such forms implies a reduction in habitat complexity and loss of micro-niches for associated organisms.

When analyzed together, all the functional traits show a clearer separation of the ambient areas (N1–S1) vs. the acidified stations, which are functionally more similar. This means that functional traits undergo a higher change than taxonomic diversity, under OA conditions, although the traits and their states here analyzed are fewer than the overall species recorded.

Similar results have been highlighted considering only the sessile phyto- and zoobenthos of vegetated hard bottoms, by [], where the functional space considering 15 traits resulted in 68 unique combinations, over the 72 total species recorded, and showed a stronger functional space reduction from ambient to extreme low pH areas, with respect to the taxonomic loss.

The above functional analyses allowed us to draw an identikit of the traits that can be favoured to thrive under future OA conditions at least for invertebrates: small and/or medium adult sizes, motile, generalist feeders (detritivores, omnivores) or herbivores, with no or weak calcification, and brooding the eggs (direct development) or deposing and protecting them in the bottoms (benthic indirect) are the traits dominating in the low and extreme low pH zones. So, species possessing one or more of such traits (some co-varying such as small size and brooding) could be pre-adapted to live and survive under the future threat of OA.

There are multiple ecological implications related to the pattern highlighted above, as regards the potential impairment of the ecosystem structure and functioning, and that have been already highlighted in previous research [,,]. However, our results are based only on qualitative data on species occurrence, and limited to quite shallow vegetated reef and seagrass habitats, so their generalization needs to take into account such intrinsic limitations.

Natural CO2 vents, such as those of the Castello at Ischia, in fact, cannot be considered precise analogues to study all the complex aspects of the effects of the ocean acidification problem, especially when projected at a large and global scale, due to their limited extension and depth and to variability in space and time in pH/carbonate chemistry. However, they provide useful insights to identify winner (surviving) and loser (selected) organisms, to analyze their life traits, physiology and genetics, and to identify changes in major species’ ecological features and interactions along gradients of high pCO2/low pH that are precious and indicative to predict the effects of this stressor at least at a local scale, and help to hypothesize future changes in community taxonomic and ecological set-ups and functions in the future oceans of the Anthropocoene.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jmse13122281/s1, Table S1: Reference list papers used to build the species check-list at the Castello vents in Table S2 and Table S3; Table S2: check-list of the animal species censused in the Castello vents; Table S3: check-list of the phytobenthic species censused in the Castello vents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.G.; Methodology, M.C.G. and C.G.; Validation, M.C.G., C.G. and A.G.; Formal analysis, F.C.; Data curation, C.G., F.C. and A.G.; Writing—original draft, M.C.G.; Writing—review & editing, M.C.G., C.G., F.C. and A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the following colleagues who provided information, literature, and advice for the definition of the trophic categories and reproductive/developmental modes of some of the groups in the check-list: Laura Nunez Pons and Renata Manconi (sponges); Valerio Zupo (decapods); Marco Oliverio, Luigia Donnarumma, and Francesco Paolo Patti (mollusks); Silvia Cocito (bryozoans); Alice Mirasole (fishes). We wish also to thank Silvia Mecca, who contributed to a partial update of the species check-list of the Castello vents system.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Maria Cristina Gambi was also associated to the company Social Cooperative Hesperia Terrae. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Caldeira, K.; Wickett, M.E. Ocean model predictions of chemistry changes from carbon dioxide emissions to the atmosphere and ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 2005, 110, C09S04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinotte, J.M.; Fabry, V.J. Ocean acidification and its potential effects on marine invertebrates. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1134, 320–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattuso, J.-P.; Magnan, A.; Billé, R.; Cheung, W.W.L.; Howes, E.L.; Joos, F.; Allemand, D.; Bopp, L.; Cooley, S.R.; Eakin, C.M.; et al. Contrasting futures for ocean and society from different anthropogenic CO2 emissions scenarios. Science 2015, 349, aac4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doney, S.C.; Busch, D.S.; Cooley, S.R.; Kroeker, K.J. The Impacts of Ocean Acidification on Marine Ecosystems and Reliant Human Communities. Ann. Rev. Environ. Res. 2020, 45, 83–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabry, V.J.; Seibel, B.A.; Feely, R.A.; Orr, J.C. Impacts of ocean acidification on marine fauna and ecosystem processes. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2008, 65, 414–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroeker, K.J.; Kordas, R.L.; Crim, R.; Hendriks, I.E.; Ramajo, L.; Singh, G.S.; Duarte, C.M.; Gattuso, J.-P. Impacts of ocean acidification on marine organisms: Quantifying sensitivities and interaction with warming. Glob. Change Biol. 2013, 19, 1884–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foo, S.A.; Byrne, M.; Ricevuto, E.; Gambi, M.C. The carbon dioxide vents of Ischia, Italy, a natural laboratory to assess impacts of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems: An overview of research and comparisons with other vent systems. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Ann. Rev. 2018, 56, 237–310. [Google Scholar]

- Rastrick, S.; Graham, H.; Azetsu-Scott, K.; Calosi, P.; Chierici, M.; Fransson, A.; Hop, H.; Hall-Spencer, J.M.; Milazzo, M.; Thor, P.; et al. Using natural analogues to investigate the effects of climate change and ocean acidification on Northern ecosystems. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2018, 75, 2299–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Delgado, S.; Hernandez, J.C. The importance of natural acidified systems in the study of Ocean Acidification: What have we learned? Adv. Mar. Biol. 2018, 80, 57–99. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasov, V.G.; Gebruk, A.V.; Mironov, A.N.; Moskalev, L.I. Deep-sea and shallow-water hydrothermal vent communities: Two different phenomena? Chem. Geol. 2005, 224, 5–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.; Sciutteri, V.; Consoli, P.; Manea, E.; Manini, E.; Andaloro, F.; Romeo, T.; Danovaro, R. Volcanic-associated ecosystems of the Mediterranean Sea: A systematic map and an interactive tool to support their conservation. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiuppa, A.; Hall-Spencer, J.M.; Milazzo, M.; Turco, G.; Caliro, S.; Di Napoli, R. Volcanic CO2 seep geochemistry and use in understanding ocean acidification. Biogeochemistry 2020, 152, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, G.E.; Smith, J.E.; Johnson, K.S.; Send, U.; Levin, L.A.; Micheli, F.; Paytan, A.; Price, N.N.; Peterson, B.; Takeshita, Y.; et al. High-frequency dynamics of ocean pH: A multi-ecosystem comparison. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Spencer, J.M.; Rodolfo-Metalpa, R.; Martin, S.; Ransome, E.; Fine, M.; Turner, S.M.; Rowley, S.J.; Tedesco, D.; Buia, M.C. Volcanic carbon dioxide vents show ecosystem effects of ocean acidification. Nature 2008, 454, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizzini, S.; Di Leonardo, R.; Costa, V.; Tramati, C.D.; Luzzu, F.; Mazzola, A. Trace element bias in the use of CO2 vents as analogues for low pH environments: Implications for contamination levels in acidified oceans. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2013, 134, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizzini, S.; Martinez-Crego, B.; Andolina, C.; Massa-Gallucci, A.; Connell, S.D.; Gambi, M.C. Ocean acidification as a driver of community simplification via the collapse of higher-order and rise of lower-order consumers. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, V.; Andaloro, F.; Canese, S.; Bortoluzzi, G.; Bo, M.; Di Bella, M.; Italiano, F.; Sabatino, G.; Battaglia, P.; Consoli, P.; et al. Exceptional discovery of a shallow-water hydrothermal site in the SW area of Basiluzzo islet (Aeolian Archipelago, South Tyrrhenian Sea): An environment to preserve. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, V.; Auriemma, R.; De Vittor, C.; Relitti, F.; Urbini, L.; Kralj, M.; Gambi, M.C. Structural and functional analyses of motile fauna associated to Cystoseira brachycarpa along a gradient of ocean acidification in a CO2 vent system off Panarea island (Aerolian Islands, Italy). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnarumma, L.; Appolloni, L.; Chianese, E.; Bruno, R.; Baldrighi, E.; Guglielmo, R.; Russo, G.F.; Zeppilli, D.; Sandulli, R. Environmental and benthic community patterns of the shallow hydrothermal area of Secca delle Fumose (Baia, Naples, Italy). Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, M.; Gambi, M.C.; Bazzarro, M.; Caruso, C.; Di Bella, M.; Esposito, V.; Gattuso, A.; Giacobbe, S.; Kralj, M.; Italiano, F.; et al. Characterization of an undocumented CO2 hydrothermal vent system in the Mediterranean Sea: Implications for ocean acidification forecasting. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0292593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabricius, K.E.; Langdon, C.; Uthicke, S.; Humphrey, C.; Noonan, S.; De’ath, G.; Okazaki, R.; Muehllehner, N.; Glas, M.S.; Lough, J.M. Losers and winners in coral reefs acclimatized to elevated carbon dioxide concentrations. Nat. Clim. Change 2011, 1, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Spencer, J.M.; Harvey, B.P. Ocean acidification impacts on coastal ecosystem services due to habitat degradation. Emerg. Topics. Life Sci. 2019, 3, 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Kroeker, K.J.; Micheli, F.; Gambi, M.C.; Martz, T.R. Divergent ecosystem responses within a benthic marine community to ocean acidification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 14515–14520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabricius, K.E.; De’ath, G.; Noonan, S.; Uthicke, S. Ecological effects of ocean acidification and habitat complexity on reef-associated macroinvertebrate communities. Proc. R. Soc. B 2014, 281, 20132479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambi, M.C.; Musco, L.; Giangrande, A.; Badalamenti, F.; Micheli, F.; Kroeker, K.J. Distribution and functional traits of polychaetes in a CO2 vent system: Winners and losers among closely related species. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2016, 550, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucey, N.M.; Lombardi, C.; DeMarchi, L.; Schulze, A.; Gambi, M.C.; Calosi, P. To brood or not to brood. Are marine organisms that protect their offspring more resilient to ocean acidification? Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garilli, V.; Rodolfo-Metalpa, R.; Scuderi, D.; Brusca, L.; Parrinello, D.; Rastrick, S.P.S.; Foggo, A.; Twitchett, R.J.; Hall-Spencer, J.M.; Milazzo, M. Physiological advantages of dwarfing in surviving extinctions in high-CO2 oceans. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixido, N.; Gambi, M.C.; Parravicini, V.; Kroeker, K.; Micheli, F.; Villeger, S.; Ballesteros, E. Functional biodiversity loss along natural CO2 gradients. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouillot, D.; Graham, N.A.J.; Villéger, S.; Mason, N.W.H.; Bellwood, D.R.A. functional approach reveals community responses to disturbances. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013, 28, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixidó, N.; Carlot, J.; Alliouane, S.; Ballesteros, E.; De Vittor, C.; Gambi, M.C.; Gattuso, J.-P.; Kroeker, K.; Micheli, F.; Mirasole, A.; et al. Functional changes across marine habitats due to ocean acidification. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancora, S.; Bianchi, N.; Butini, A.; Buia, M.C.; Gambi, M.C.; Leonzio, C. Posidonia oceanica as a biomomitor of trace elements in the Gulf of Naples: Temporal trends by lepidochronology. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2004, 23, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirasole, A.; Di Franco, A.; Andolina, C.; Gambi, M.C.; Gillanders, B.M.; Pecoraino, G.; Reis-Santos, P.; Scopelliti, G.; Somma, E.; Vizzini, S.; et al. Submitted. Ocean acidification influences site fidelity and seagrass habitat use by an herbivorous fish. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, under review. [Google Scholar]

- Ricevuto, E.; Kroeker, K.J.; Ferrigno, F.; Micheli, F.; Gambi, M.C. Spatio-temporal variability of polychaete colonization at volcanic CO2 vents (Italy) indicates high tolerance to ocean acidification. Mar. Biol. 2014, 161, 2909–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porzio, L.; Buia, M.C.; Hall-Spencer, J.M. Effects of ocean acidification on macroalgal communities. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2011, 400, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrard, S.L.; Gambi, M.C.; Scipione, M.B.; Patti, F.P.; Lorenti, M.; Zupo, V.; Paterson, D.M.; Buia, M.C. Indirect effects may buffer negative responses of seagrass invertebrate communities to ocean acidification. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2014, 461, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricevuto, E.; Lorenti, M.; Patti, F.P.; Scipione, M.B.; Gambi, M.C. Temporal trends of benthic invertebrate settlement along a gradient of ocean acidification at natural CO2 vents (Tyrrhenian Sea). Biol. Mar. Mediter. 2012, 19, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Donnarumma, L.; Lombardi, C.; Cocito, S.; Gambi, M.C. Settlement pattern of Posidonia oceanica epibionts along a gradient of ocean acidification: An approach with mimics. Mediter. Mar. Sci. 2014, 15, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barruffo, A.; Ciaralli, L.; Ardizzone, G.; Gambi, M.C.; Casoli, E. Ocean Acidification and Molluscs Settlement in Posidonia oceanica Meadows: Does the Seagrass Buffer Low pH Effects at CO2 Vents? Diversity 2021, 13, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, K.S.; Wallberg, A.; Jondelius, U. New species of Acoela from the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and the South Pacific. Zootaxa 2011, 2867, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglioti, M.; Ricevuto, E.; Gambi, M.C. Pattern and map of biodiversity related to ocean acidification in CO2 vents of Ischia. Biol. Mar. Mediter. 2018, 25, 235–236. [Google Scholar]

- WoRMS: World Register of Marine Species 2000. Available online: https://www.marinespecies.org/ (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Lanera, P.; Gambi, M.C. Polychaete distribution in some Cymodocea nodosa meadows around the island of Ischia (Gulf of Naples, Italy). Oebalia 1993, 19, 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austr. Ecol. 2001, 26, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R version 4.5.2, released 2025-10-31; Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Giangrande, A.; Gambi, M.C.; Micheli, F.; Kroeker, K.J. Fabriciidae (Annelida, Sabellida) from a naturally acidified coastal system (Italy) with description of two new species. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2014, 94, 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giangrande, A.; Putignano, M.; Licciano, M.; Gambi, M.C. The Pandora’s box: Morphological diversity within the genus Amphiglena Claparède, 1864 (Sabellidae, Annelida) in the Mediterranean Sea with the description of nine new species. Zootaxa 2021, 4949, 201–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cookson, L.J.; Lorenti, M. A new species of Limnoriid seagrass borer (Isopoda) from the Mediterranean. Crustaceana 2001, 74, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cioccio, D.; Buia, M.C.; Zingone, A. Ocean acidification will not deliver us from Ostreopsis. In Harmful Algae 2012. Proceedings ISSHA Conference. Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Harmful Algae, Changwon, Korea, 29 October–2 November 2012; Kim, H.G., Reguera, B., Hallegraeff, G., Lee, C.K., Han, M.S., Choi, J.K., Eds.; International Society for the Study of Harmful Algae: Changwon, Republic of Korea, 2015; pp. 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gambi, M.C.; Lorenti, M.; Patti, F.P.; Zupo, V. An annotated list of alien marine species of the Ischia Island. Not. della Soc. Ital. di Biol. Mar. 2016, 70, 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Calosi, P.; Rastrick, S.P.S.; Lombardi, C.; de Guzman, H.J.; Davidson, L.; Jahnke, M.; Giangrande, A.; Hardege, J.D.; Schulze, A.; Spicer, J.I.; et al. Adaptation and acclimatization to ocean acidification in marine ectotherms: An in situ transplant experiment with polychaetes at a shallow CO2 vent system. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 2013, B368, 20120444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giangrande, A. Polychaete reproduction patterns, life cycles and life histories: An overview. Ocean Mar. Biol. Ann Rev. 1997, 35, 323–386. [Google Scholar]

- Garrard, S.L. The Effect of Ocean Acidification on Plant-Animal Interactions in a Posidonia oceanica Meadow. Ph.D. Thesis, Open University, Milton Keynes, UK, 2013; p. 143. [Google Scholar]

- Rodolfo-Metalpa, R.; Houlbrèque, F.; Tambutté, É.; Boisson, F.; Baggini, C.; Patti, F.P.; Jeffree, R.; Fine, M.; Foggo, A.; Gattuso, J.P.; et al. Coral and mollusc resistance to ocean acidification adversely affected by warming. Nat. Clim. Change 2011, 1, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, I.E.; Olsen, Y.S.; Ramajo, L.; Basso, L.; Steckbauer, A.; Moore, T.S.; Howard, J.; Duarte, C.M. Photosynthetic activity buffers ocean acidification in seagrass meadows. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricart, A.M.; Ward, M.; Hill, T.M.; Sanford, E.; Kroeker, K.J.; Takeshita, Y.; Merolla, S.; Shukla, P.; Ninokawa, A.T.; Elsmore, K.; et al. Coast-wide evidence of low pH amelioration by seagrass ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 2580–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucey, N.L.; Lombardi, C.; Florio, M.; DeMarchi, L.; Nannini, M.; Rundle, S.; Gambi, M.C.; Calosi, P. No evidence of local adaptation to low pH in a calcifying polychaete population from a shallow CO2 vent system. Evol. Appl. 2016, 9, 1054–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, L.M.; Ricevuto, E.; Massa-Gallucci, A.; Lorenti, M.; Gambi, M.C.; Calosi, P. Metabolic responses to high pCO2 conditions at a CO2 vent site in the juveniles of a marine isopod assemblage. Mar. Biol. 2016, 163, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambi, M.C.; Barbieri, F.; Signorelli, S.; Saggiomo, V. Mortality events along the Campania coast (Tyrrhenian Sea) in summers 2008 and 2009 and relation to thermal conditions. Biol. Mar. Mediter. 2010, 17, 126–127. [Google Scholar]

- Rodolfo-Metalpa, R.; Lombardi, C.; Cocito, S.; Hall-Spencer, J.; Gambi, M.C. Effects of ocean acidification and high temperatures on the bryozoan Myriapora truncata at natural CO2 vents. Mar. Ecol. 2010, 31, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaglioli, C.; Lauritano, C.; Buia, M.C.; Balestri, E.; Capocchi, A.; Fontanini, D.; Pardi, G.; Tamburello, L.; Procaccini, G.; Bulleri, F. Nutrient Loading Fosters Seagrass Productivity Under Ocean Acidification. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambi, M.C.; Esposito, V.; Marin Guirao, L. Posidonia bonsai: Dwarf Posidonia oceanica shoots associated to hydrothemal vent systems (Panarea island, Italy). Aquat. Bot. 2023, 185, 103611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambi, M.C.; Iacono, C.; Miccio, A.; Esposito, V.; Procaccini, G.; Marin Guirao, L. Posidonia bonsai: Dwarf morphotypes of Posidonia oceanica in CO2 vents and no vents areas, suggest a novel growth strategy. Aquat. Bot. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Delgado, S.; Wangensteen, O.S.; Sangi, C.; Hernández, C.A.; Alfonso, B.; Soto, A.Z.; Pérez-Portela, R.; Mariani, S.; Hernández, J.C. High taxonomic diversity and miniaturization in benthic communities under persistent natural CO2 disturbances. Proc. R. Soc. B 2023, 290, 20222417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, P.M.; Parker, L.; O’Connor, W.A.; Bailey, E.A. The Impact of Ocean Acidification on Reproduction, Early Development and Settlement of Marine Organisms. Water 2011, 3, 1005–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).