Port Resilience Assessment for Misdeclaration Induced Disasters Using a Hybrid LLM-GNN Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A hybrid LLM-STGNN framework that addresses the data scarcity challenge in dynamic disaster resilience assessment. By synthesizing training data from sparse real incidents through multimodal LLMs, the framework enables spatiotemporal propagation modeling in scenarios where traditional probability-based methods struggle to obtain sufficient historical records or expert knowledge. Validation on misdeclaration-induced disasters demonstrates its effectiveness in low-frequency, high-consequence events.

- (2)

- A systematic methodology for multimodal data extraction and DHSG construction, providing a structured representation for complex system dynamic modeling that explicitly characterizes multi-dimensional coupling relationships among port entities across physical, functional, and environmental dimensions.

- (3)

- An STGNN architecture that integrates spatiotemporal dependency learning with intervention simulation capabilities, enabling controllable evaluation of emergency strategies and supporting the quantitative assessment of different recovery policies.

- (4)

- Comprehensive sensitivity analyses based on real port accident scenarios, quantifying the impact of intervention strategies, environmental conditions, and management policies on system resilience, and providing actionable decision support for port operators and regulatory authorities.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Network Structure-Based Resilience Analysis

2.2. Indicator System-Based Resilience Analysis

2.3. Probability-Based Resilience Analysis

2.4. Simulation/AI-Based Resilience Analysis

2.5. Summary and Positioning of This Study

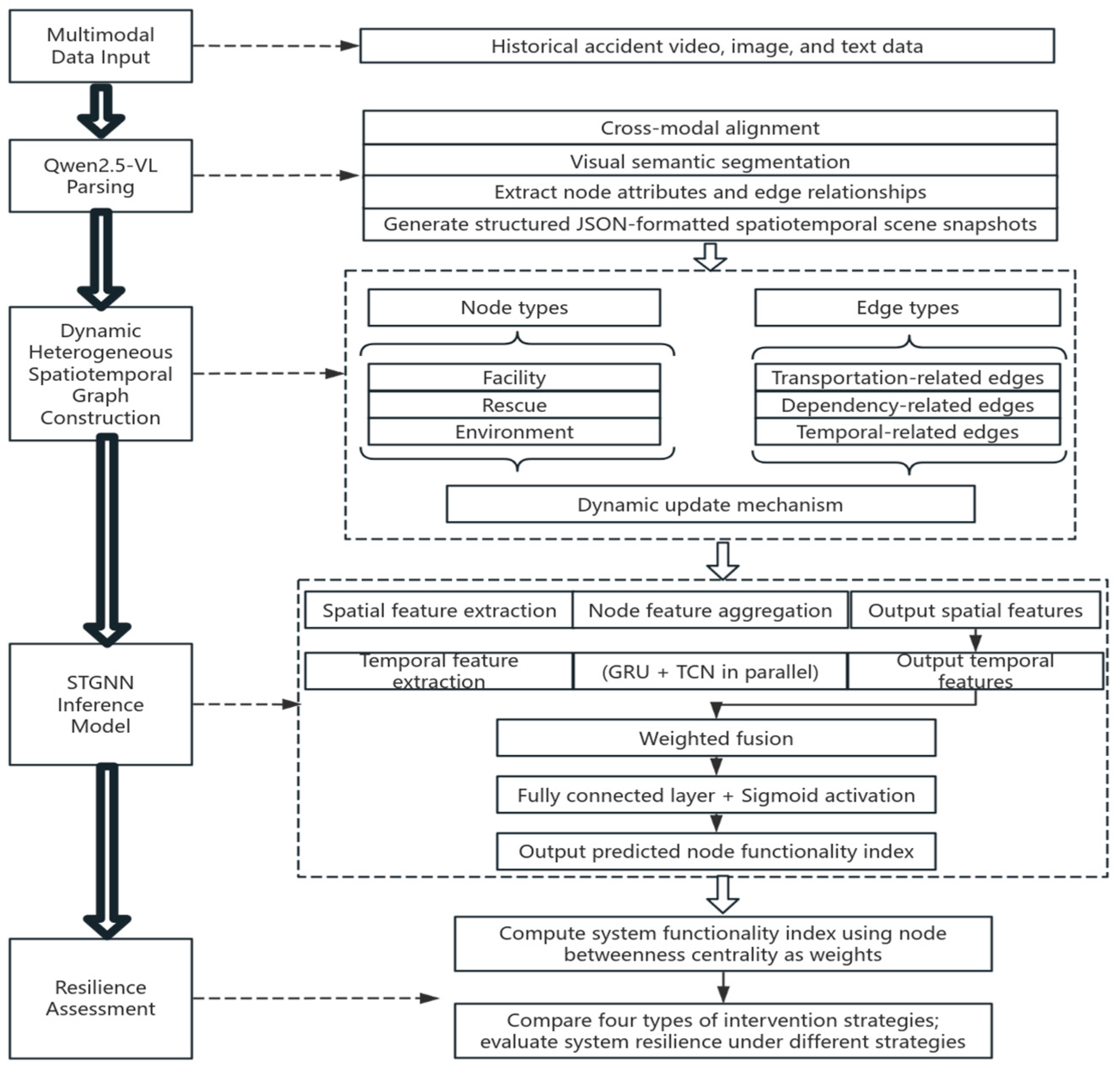

3. Methods

- (1)

- LLM-Driven Multimodal Data Synthesis: Multimodal data from historical accident incidents, including surveillance videos, satellite imagery and textual investigation reports, are processed through the Qwen2.5-VL model to extract structured spatiotemporal information. The LLM performs cross-modal alignment, visual semantic segmentation, and state quantification to generate JSON-formatted scene snapshots at each time step. Beyond extraction, the LLM leverages its generalizable world knowledge to augment the limited real-world cases (Ningbo, Tianjin, Beirut ports) into 97 diversified simulation scenarios, ensuring sufficient training data while maintaining physical consistency and disaster evolution fidelity.

- (2)

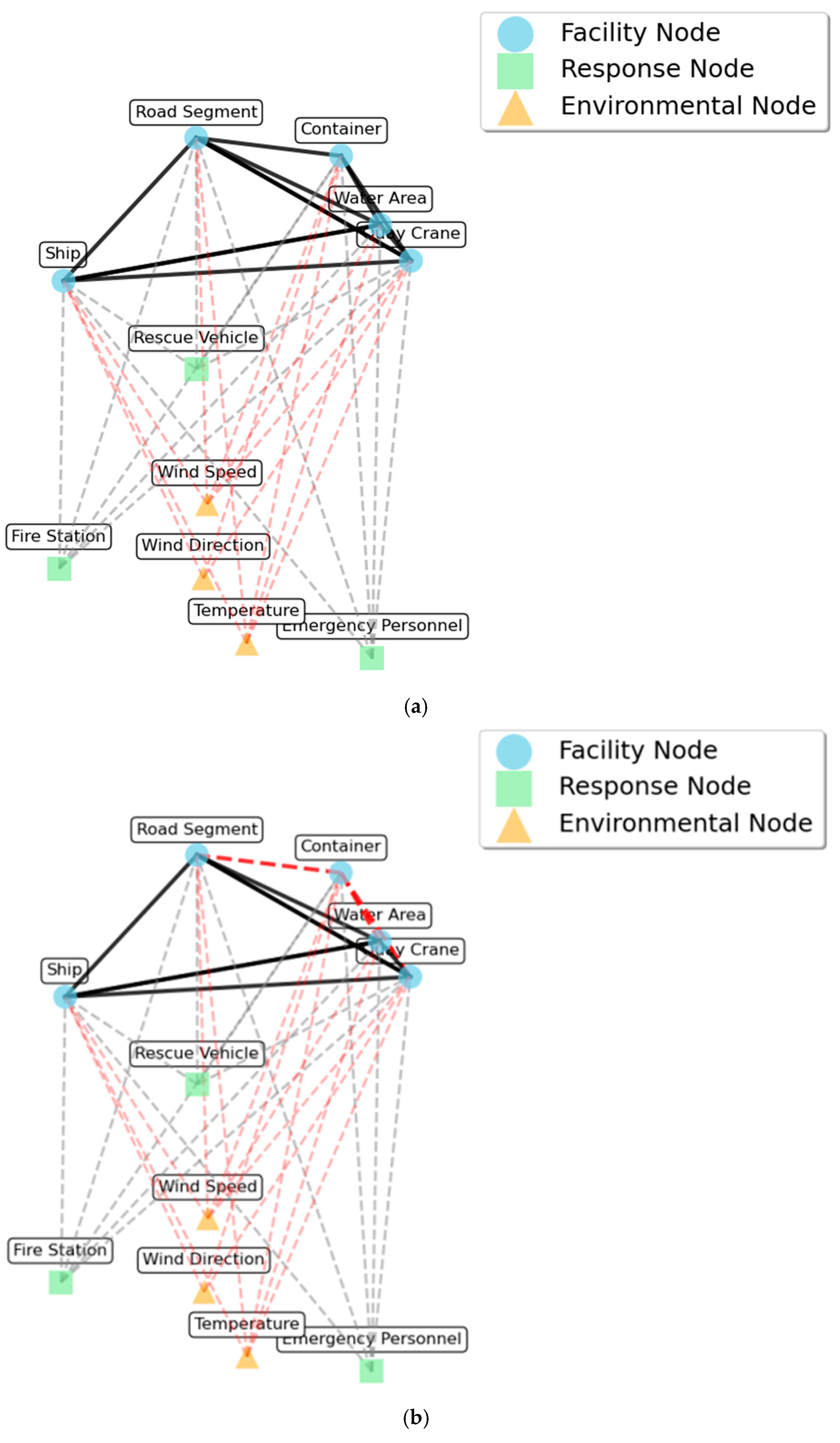

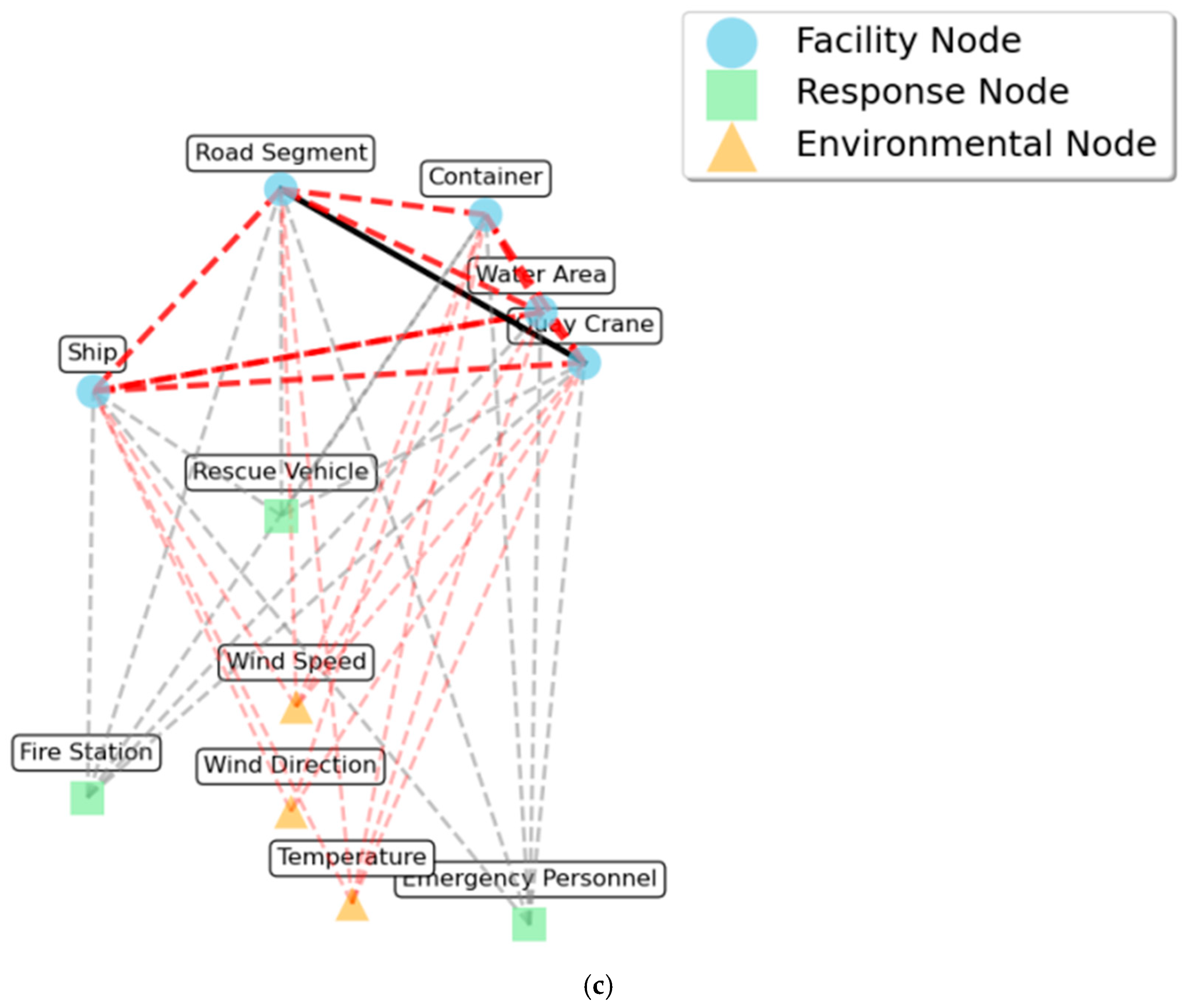

- DHSG Construction: The extracted and augmented data are transformed into a unified graph representation where port facilities, emergency response units, and environmental factors are abstracted as heterogeneous nodes, while their physical connections, functional dependencies, and temporal associations form typed edges. The DHSG employs a dynamic update mechanism that captures the complete disaster lifecycle from initial disturbance and risk propagation to emergency intervention by adjusting edge existence and weights over 24 hourly time steps, thereby providing a high-fidelity structured input for subsequent spatiotemporal learning.

- (3)

- STGNN for Disaster Evolution Modeling: A specialized STGNN architecture integrates heterogeneous graph convolution for spatial dependency extraction with a parallel GRU-TCN temporal module that simultaneously captures long-term trends and abrupt anomalies. The model incorporates a risk attention mechanism that dynamically weights propagation pathways based on dependency intensity, enabling accurate prediction of node-level functional degradation. Critically, the framework treats emergency interventions as controllable external signals by encoding repair actions and recovery rates as additional node features, allowing the trained model to autonomously simulate system evolution under different response strategies.

- (4)

- Resilience Quantification and Intervention Evaluation: Node-level predictions are aggregated into system functionality indices using topology-based weighting, from which three core resilience metrics are computed: Peak Resilience Loss, Recovery Time, and Resilience Area. The framework supports “what-if” simulation with four intervention strategies, which are no intervention, random allocation, centrality-priority and path-blocking, enabling comparative evaluation and optimization of emergency resource deployment before actual implementation.

3.1. Data Extraction and Preprocessing

- (1)

- Data Sources. The study integrates four complementary categories of disaster-related information: historical accident investigation reports obtained through online searches provide causal mechanisms, event timelines, system failures, and regulatory findings; surveillance videos supplied by port authorities and self-media accounts cover critical facilities including container yards, quay crane zones, and road networks, enabling reconstruction of fire spread trajectories, equipment damage progression, and emergency response deployment patterns; satellite imagery covering affected port regions to observe spatial layouts, explosion impact zones, plume dispersion, and structural deformation across multiple time points; public news releases issued by maritime safety agencies offer supplemental information on event triggers, emergency level escalation, casualty updates, and official situational assessments.

- (2)

- Data Cleaning Procedures. All multimodal inputs underwent a unified preprocessing pipeline to ensure consistency and analytical validity through four key steps: text deduplication via human reading; temporal normalization converted all timestamps from reports, videos, and imagery into a standardized accident-centered timeline with t = 0 marking the initial event, using interpolation to align video frame timestamps with satellite image acquisition times; complete environmental parameter records including wind speed and temperature, and explicit causality descriptions linking sequential events.

- (3)

- Vectorization. To transform heterogeneous multimodal data into unified machine-readable representations, the Qwen2.5-VL-72B [33] model processes all inputs through its integrated multimodal architecture: visual inputs including video frames and satellite imagery are analyzed to extract semantic descriptions of spatial layouts, damage patterns, and temporal dynamics; textual inputs including investigation reports, news narratives, and visual observations are processed to identify causal relationships and operational context; numerical attributes including spatial coordinates, meteorological variables, and equipment categories are extracted and normalized into continuous feature values. Through carefully designed prompts, the model outputs structured JSON snapshots where each node is described by its functional state, operational status, and spatial attributes, while edges are characterized by their relationship types and weights. These JSON-formatted outputs are then directly parsed into numerical arrays to form the feature matrix and adjacency tensor of the DHSG, with each node represented by a feature vector containing its functional index, status indicators, and static attributes.

- (4)

- No Additional Training on the LLM. It is emphasized that no fine-tuning or additional training is performed on the large language model itself, as all multimodal extraction, state inference, and scenario synthesis are achieved solely through structured prompts and constraint-based reasoning that leverage the pretrained capabilities of Qwen2.5-VL-72B. This zero-shot approach preserves the generalizable world knowledge of the pretrained model and enhances framework transferability across different ports and disaster types without requiring domain-specific model retraining.

3.1.1. Real Incident Data Acquisition

- (1)

- Ningbo Port (2023): Class 5.2 organic peroxides declared as general cargo, triggering spontaneous combustion under high temperature.

- (2)

- Tianjin Port (2015): Concealed quantities of nitrocellulose and other hazardous materials causing chain explosions.

- (3)

- Beirut Port (2020): Long-term undeclared ammonium nitrate storage culminating in catastrophic explosion.

3.1.2. LLM-Based Multimodal State Extraction

- (1)

- Cross-modal Semantic Alignment: Video frames, satellite imagery and textual descriptions are semantically aligned to establish spatiotemporal consistency.

- (2)

- Visual Semantic Segmentation: The LLM performs pixel-level segmentation of critical infrastructure including containers, vessels, quay cranes, roads, and water areas. Damaged regions are identified through visual anomaly detection.

- (3)

- Damage State Quantification: The damage ratio of each facility node is calculated as:

3.1.3. Attribute and Relationship Extraction

3.1.4. LLM-Guided Scenario Augmentation

- (1)

- Exemplar scenes from real incidents formatted as JSON snapshots with node states, edge relationships, and temporal sequences.

- (2)

- Physical constraints including causality rules (e.g., “fire propagates through transportation edges to adjacent flammable nodes”), environmental effects (e.g., “wind speed > 8 m/s accelerates lateral fire spread by factor 1.5”), and operational dependencies (e.g., “road blockage prevents rescue vehicle access”).

- (3)

- Variation parameters specifying controllable dimensions: misdeclaration type (category/weight/temperature-control), deviation rate (10–50%), environmental conditions (temperature 20–35 °C, wind speed 3–12 m/s), and regulatory intensity (0.3–0.7).

3.2. Dynamic Heterogeneous Spatiotemporal Graph Construction

3.2.1. Heterogeneous Node Abstraction

3.2.2. Typed Edge Semantics and Dynamic Weighting

3.2.3. Dynamic Evolution and Multi-Scale Coupling

3.3. STGNN for Disaster Evolution Modeling

3.3.1. Heterogeneous Graph Convolution with Risk Attention

3.3.2. Parallel GRU-TCN Temporal Architecture

3.3.3. Spatiotemporal Fusion and Intervention Encoding

3.3.4. Training Optimization

3.4. Resilience Quantification and Intervention Evaluation

3.4.1. Node Functional Index

3.4.2. System Functionality Aggregation

3.4.3. Core Resilience Metrics

3.4.4. Intervention Strategy Simulation

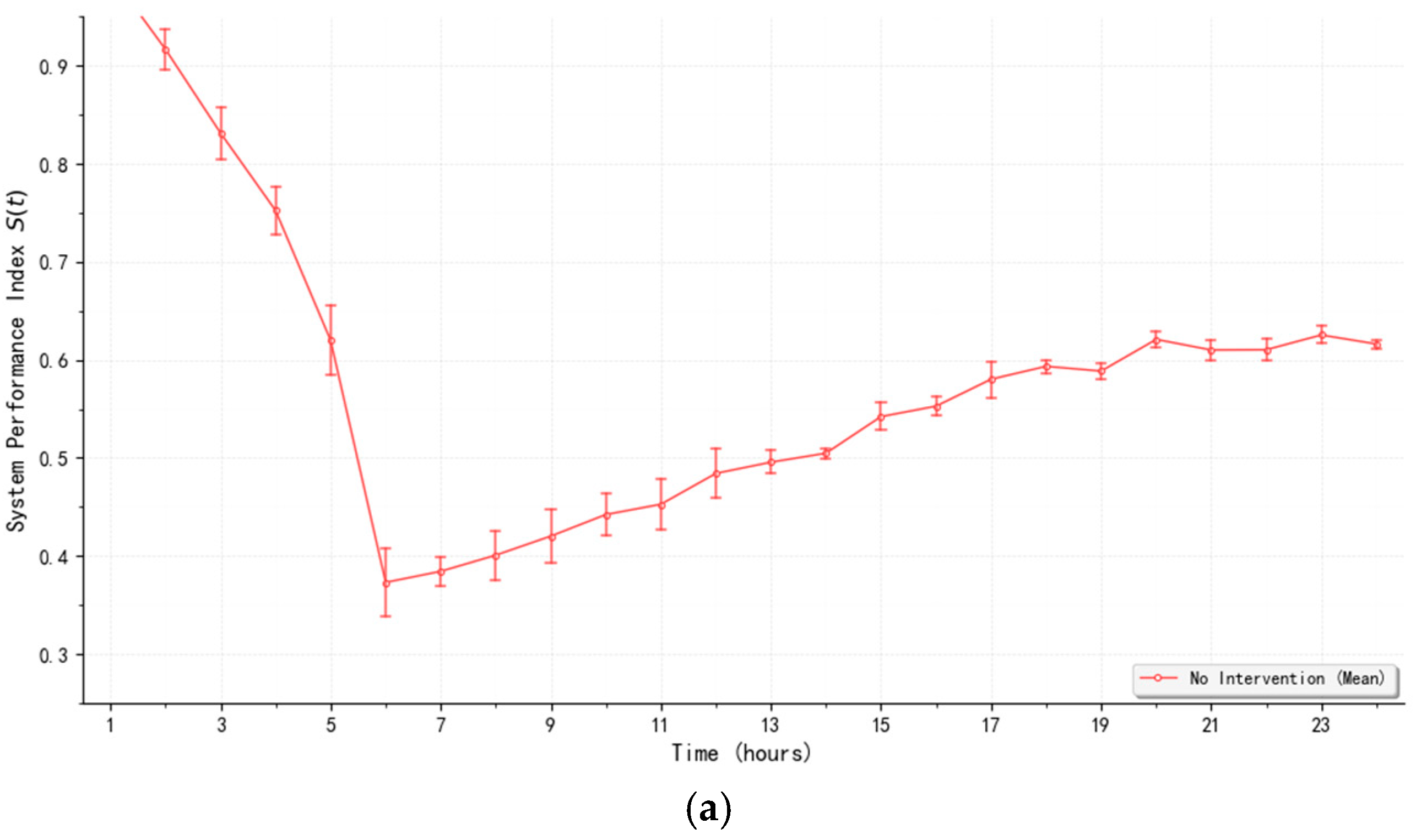

- (1)

- No Intervention: No repair actions are taken; the system relies on natural recovery.

- (2)

- Random Intervention: A node is randomly selected from the set of degraded nodes for repair.

- (3)

- Centrality-Priority: Nodes are prioritized for repair in descending order of betweenness centrality weight wi.

- (4)

- Path-Blocking: Nodes located on high-risk propagation paths are prioritized to disrupt cascading failures. The high-risk paths are determined by weighted out-degree of dependency edges.

4. Case Study

4.1. Experimental Setup

- (1)

- Emergency resource allocation strategies;

- (2)

- Environmental risk levels;

- (3)

- Types and deviation magnitudes of false declarations;

- (4)

- Initial regulatory intensity and emergency response levels.

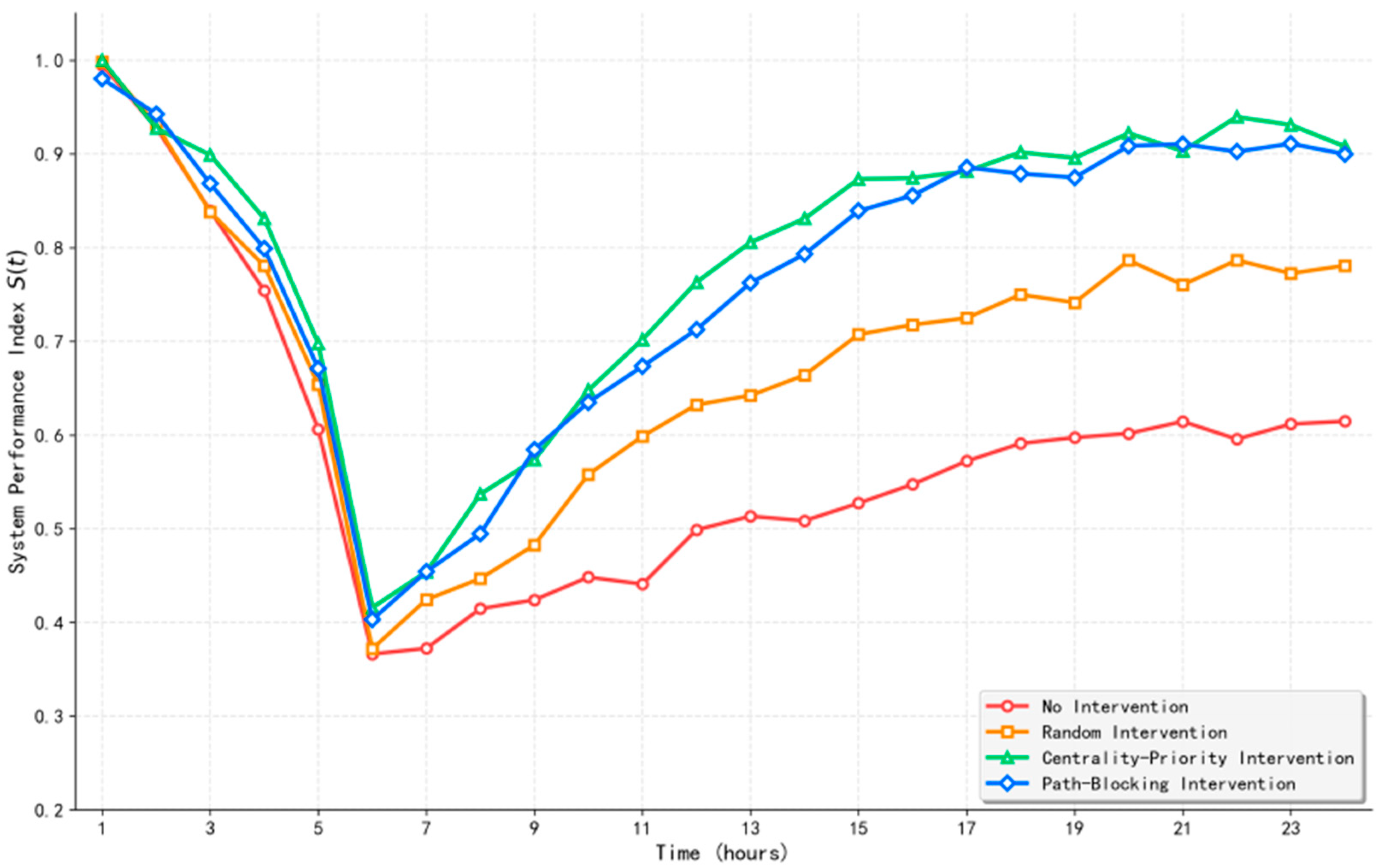

4.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Intervention Strategies

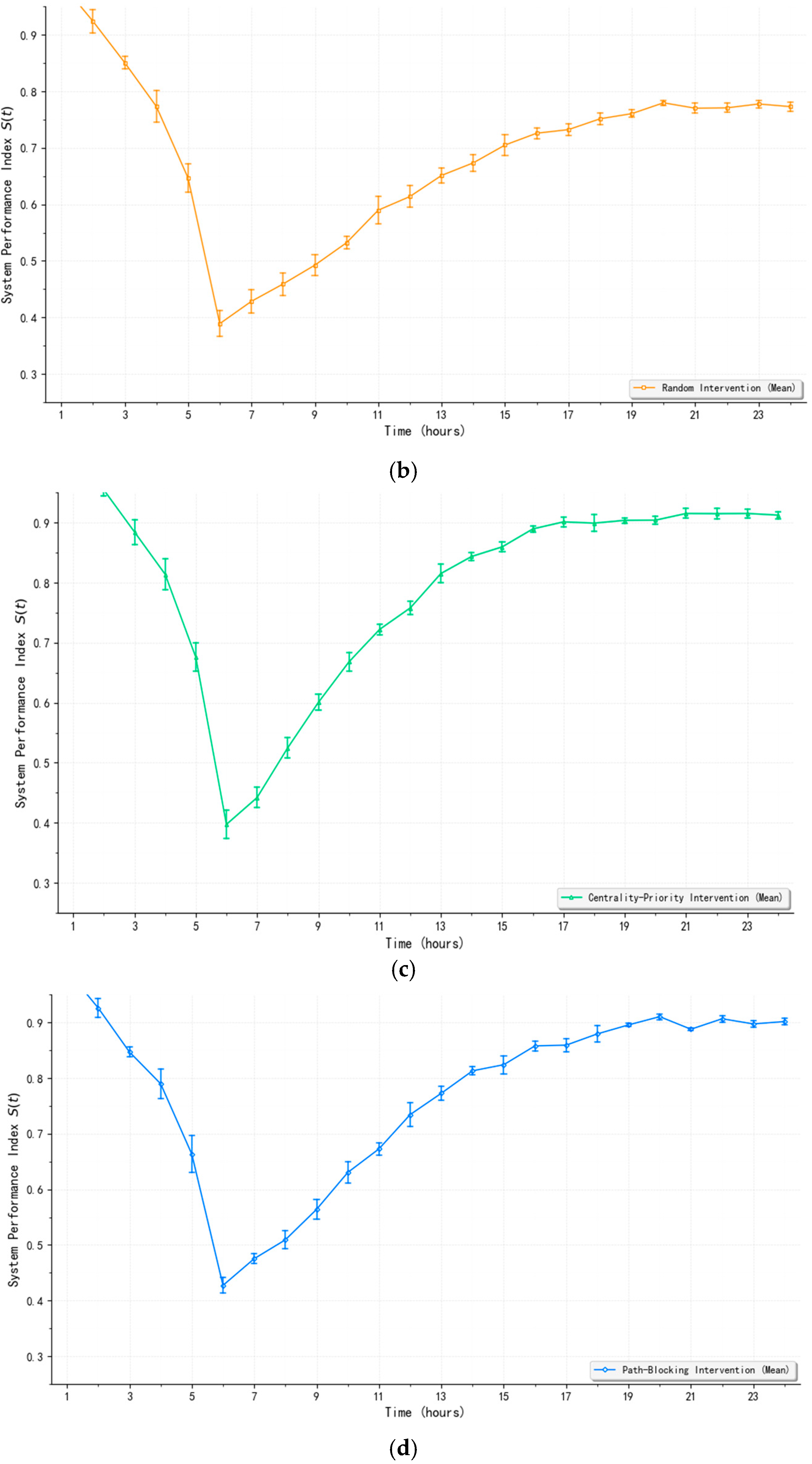

4.3. Environmental Factor Sensitivity Analysis

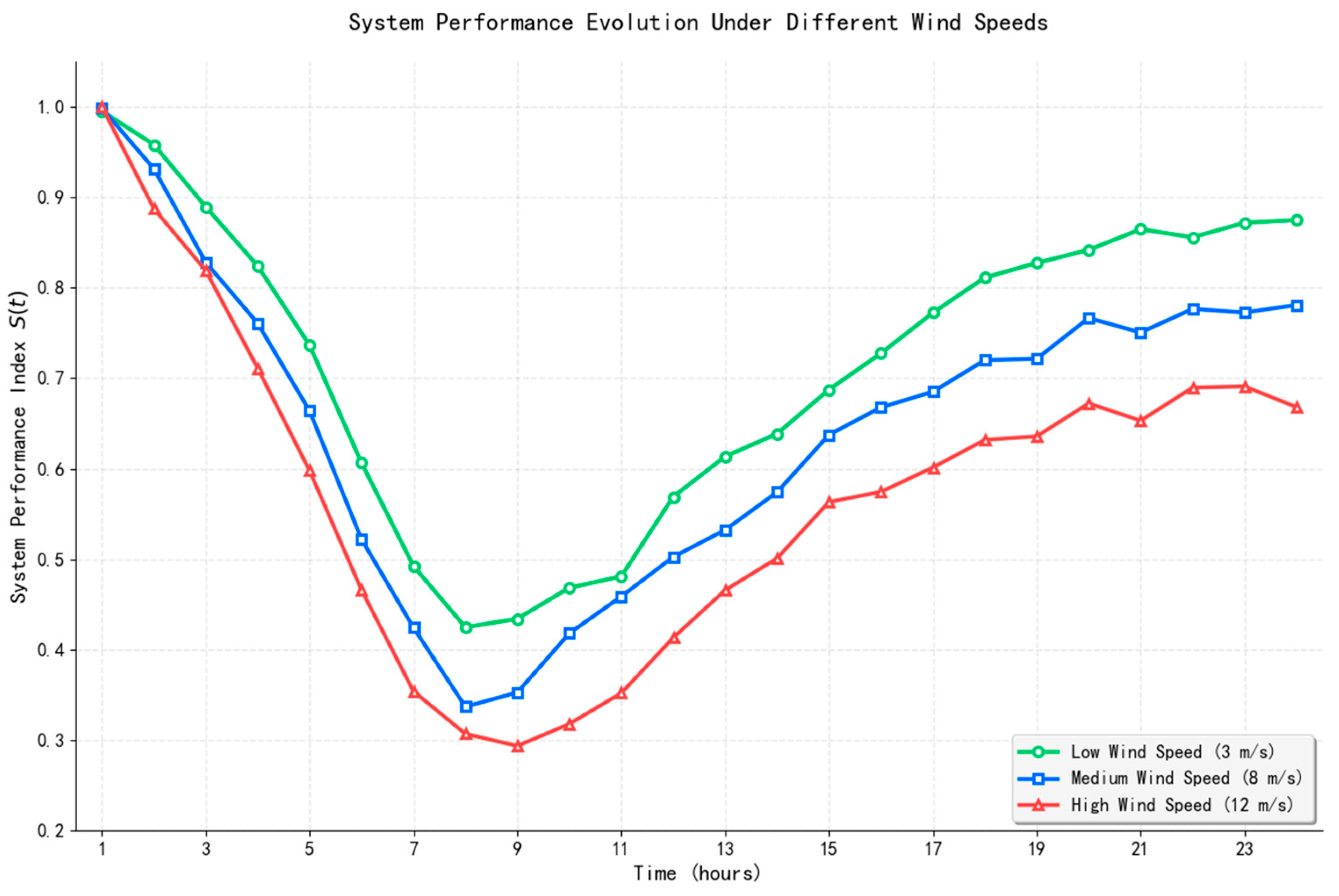

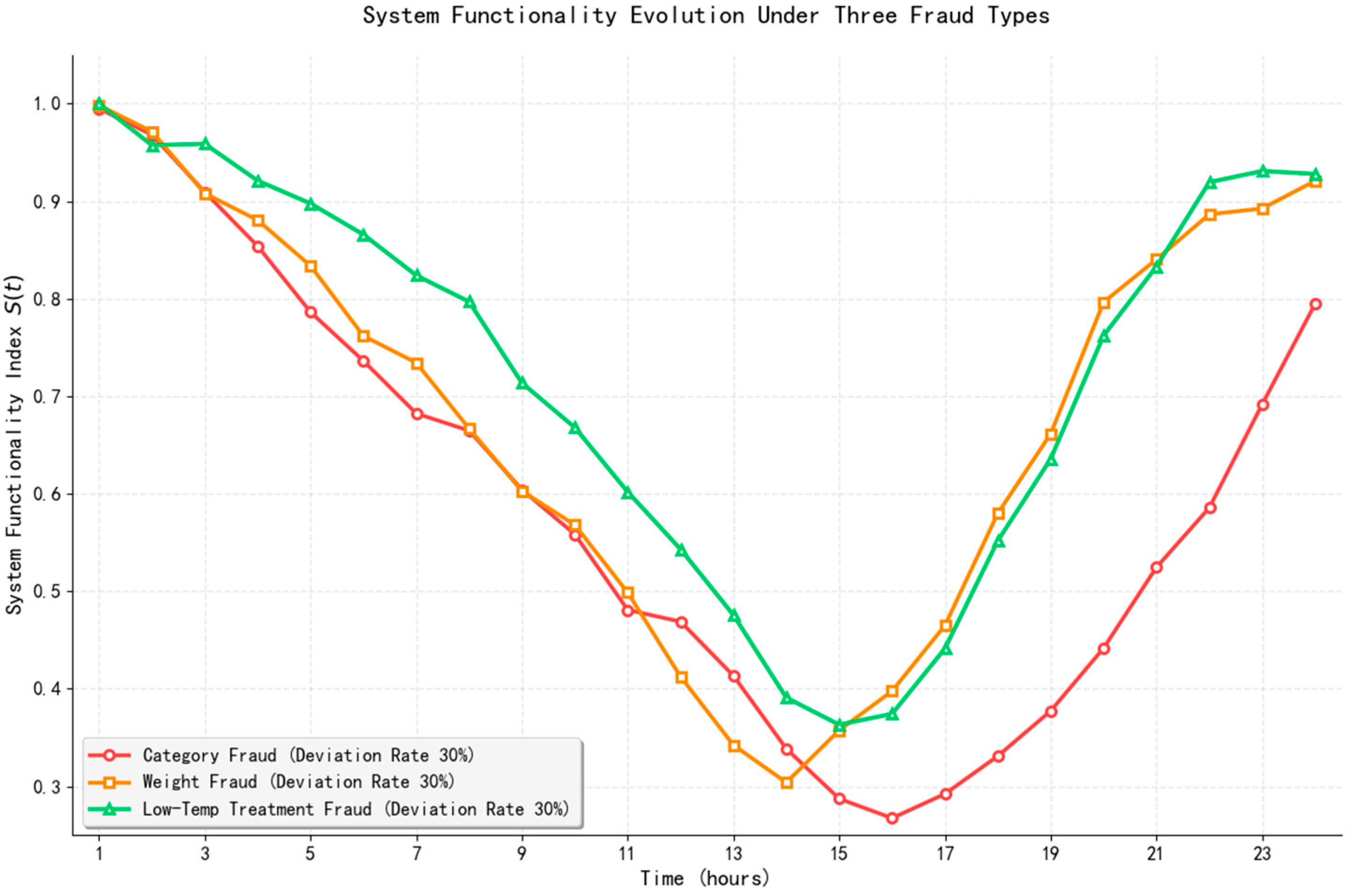

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Misdeclaration Type and Deviation Rate

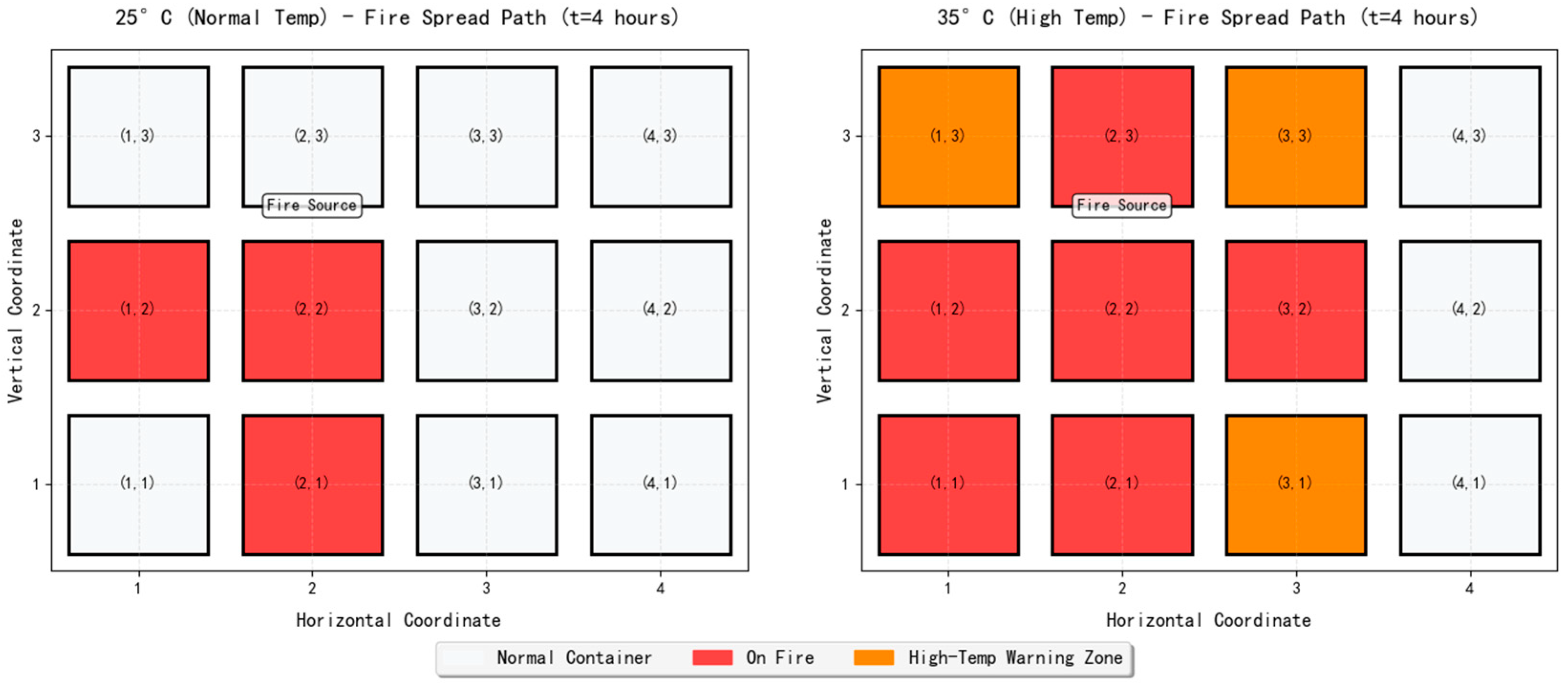

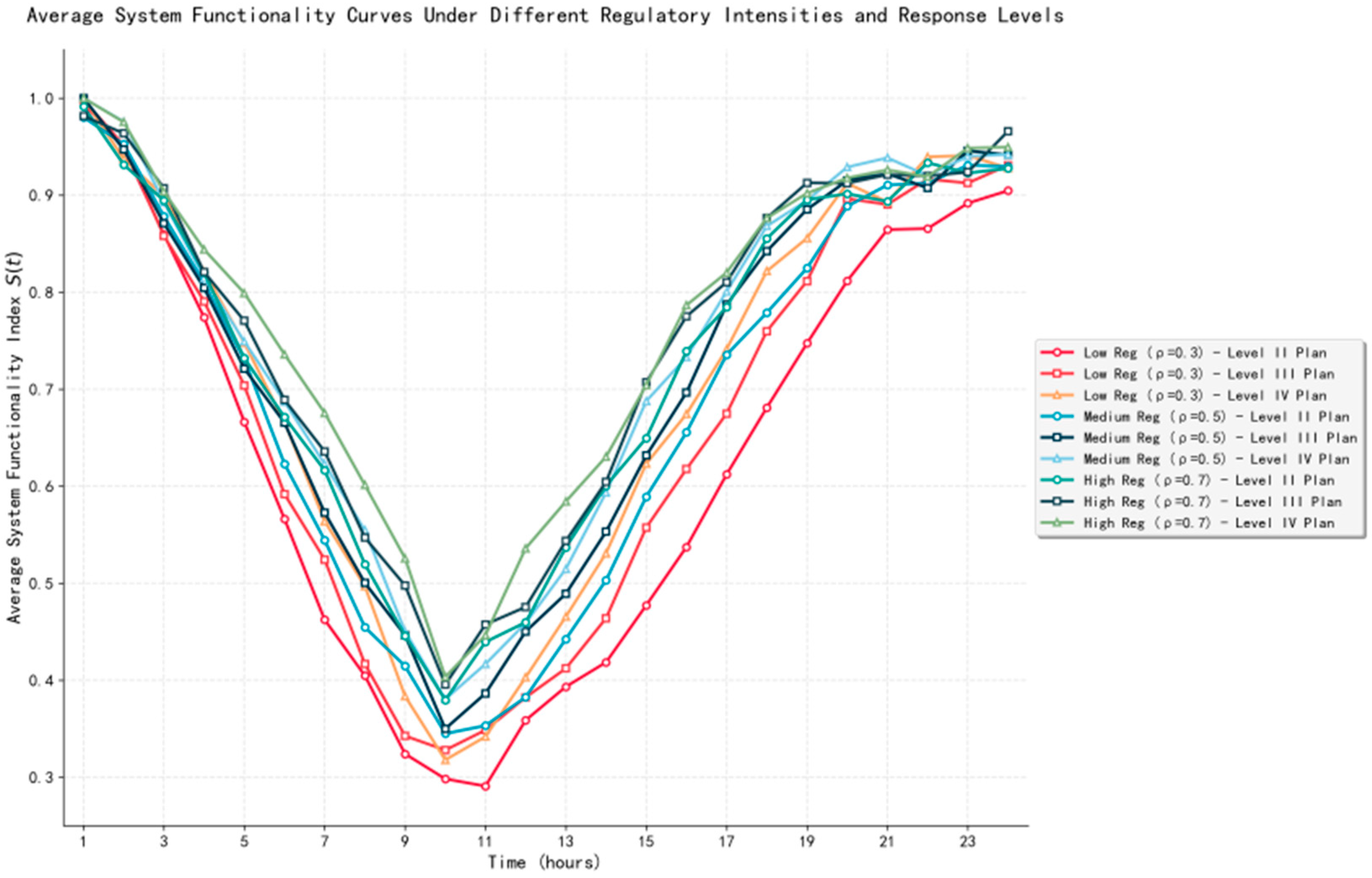

4.5. Sensitivity Analysis of Initial Regulatory Intensity and Emergency Response Level

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The modeling approach based on Dynamic Heterogeneous Spatiotemporal Graphs (DHSG) effectively captures the complex coupling mechanisms of disasters triggered by misdeclaration. By distinguishing between transportation edges, dependency edges, and temporal edges, the model accurately characterizes the propagation pathways of fires, explosions, and other hazards across spatial, functional, and environmental dimensions. The synergistic architecture of Qwen2.5-VL and STGNN facilitates an end-to-end mapping from multimodal data such as images and textual reports to node states, thereby enhancing the automation and objectivity of state perception.

- (2)

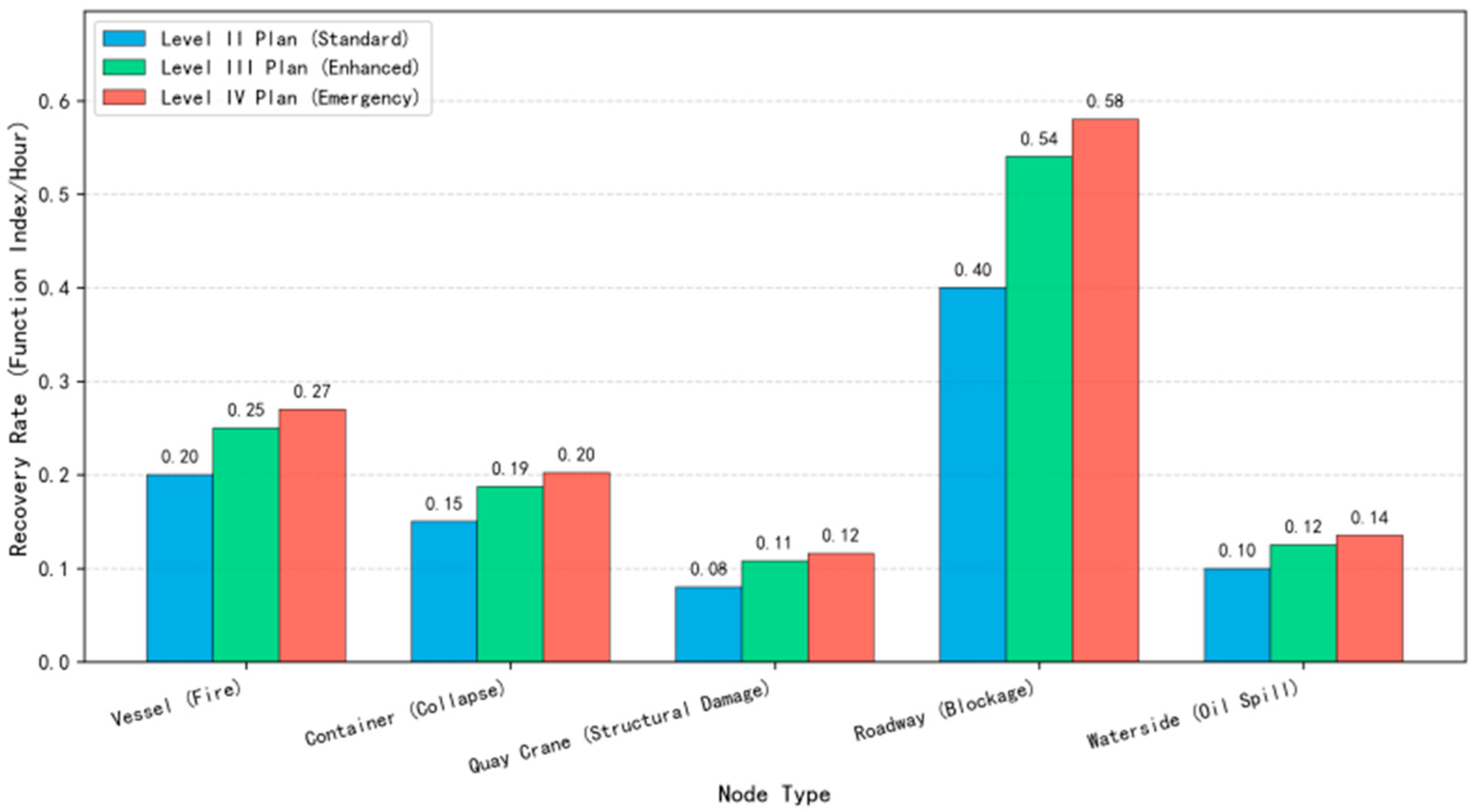

- Scientifically designed emergency intervention strategies can significantly enhance the system’s recovery capacity. Sensitivity analyses demonstrate that the Centrality-Priority Intervention strategy, which prioritizes the restoration of nodes with high betweenness centrality, can reduce the Recovery Time by 42%. Conversely, the Path-Blocking Intervention strategy proves effective in suppressing the Peak Resilience Loss, validating the guiding value of topological structure in emergency decision-making. By incorporating recovery rates as external control signals into the model, the framework supports what-if simulation for strategy pre-evaluation and effect comparison.

- (3)

- Environmental factors exert a significant amplifying effect on disaster evolution. Increased wind speed and temperature markedly accelerate fire spread, leading to a 12–20% increase in Peak Resilience Loss and a 28–39% expansion in Resilience Area. Specifically, high wind speeds primarily compress the response window by enhancing spatial diffusion, while elevated temperatures trigger a multi-point outbreak pattern by accelerating chemical reaction rates, underscoring the necessity of proactive early warnings and physical isolation measures under extreme meteorological conditions.

- (4)

- Among various types of misdeclaration, category misdeclaration poses the highest risk. Unlike weight or temperature-control misdeclarations, category misdeclaration completely circumvents the regulatory system, allowing risks to accumulate silently over time and ultimately resulting in a latent eruption. The Resilience Area associated with category misdeclaration exhibits nonlinear growth with increasing deviation rates; at a 50% deviation rate, Resilience Area increases by 92.8% compared to the 10% baseline, highlighting the critical role of intelligent image analysis and multi-source data verification technologies in source-level prevention.

- (5)

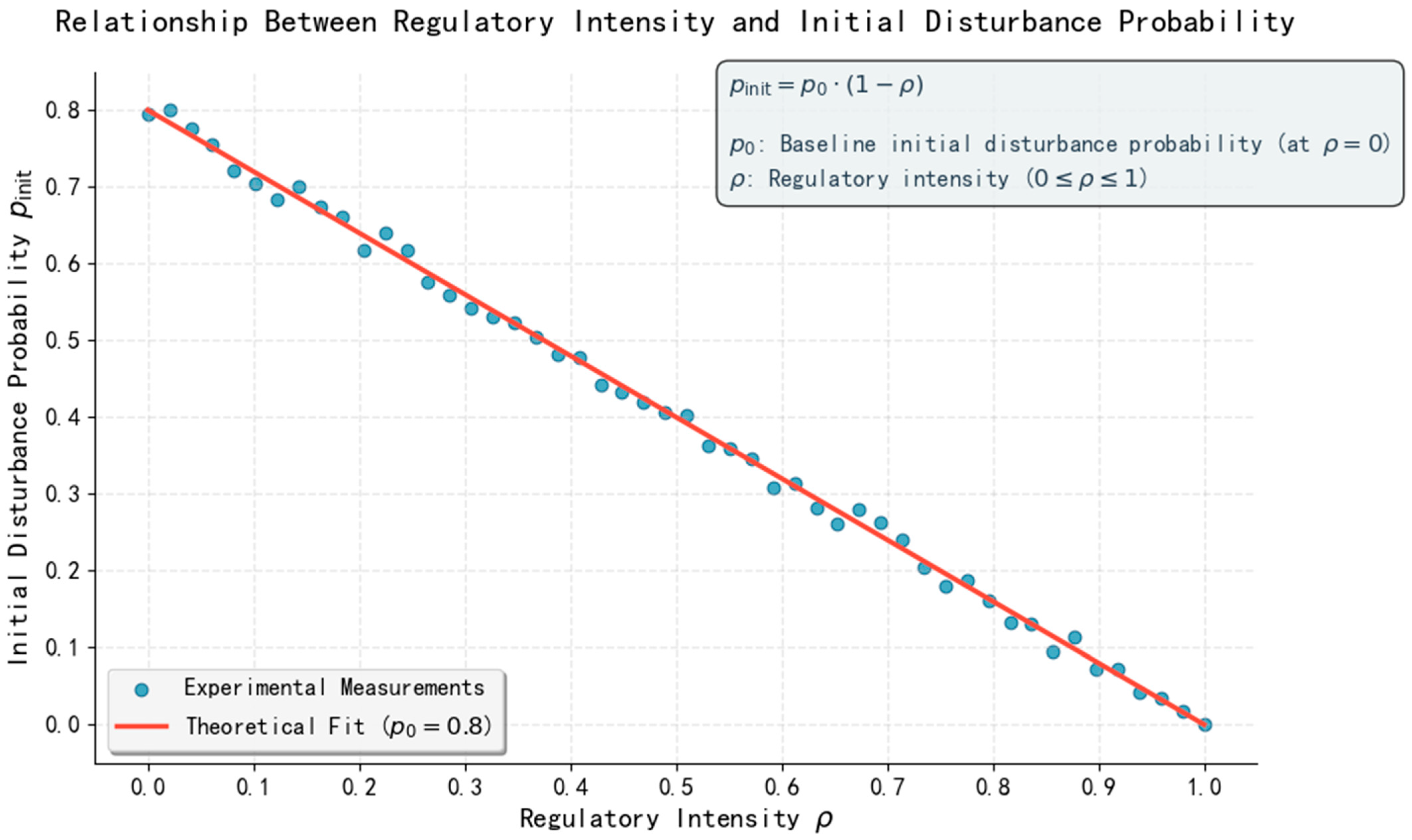

- The initial regulatory intensity exerts a more favorable impact on system resilience than the emergency response level. Enhancing regulatory intensity significantly reduces the initial disturbance probability and delays disaster onset. Its improvement in the Resilience Area of 29.6% surpasses that achieved by upgrading the response level at 22.8%. The synergistic effect of high regulatory intensity and a high-level emergency response yields optimal resilience performance, substantiating the governance principle of prevention over response and providing quantitative justification for resource allocation.

- (1)

- Establish an integrated intelligent supervision platform that combines risk pre-identification, dynamic simulation, and resilience evaluation, incorporating AI-powered image analysis, multi-source data verification, and disaster simulation capabilities to enhance the efficiency of misdeclaration detection.

- (2)

- Develop a differentiated emergency response strategy repository that prescribes intervention priorities based on specific misdeclaration types and environmental conditions, enabling precision rescue through topology-based resource allocation.

- (3)

- Elevate the regulatory standards for hazardous material storage during high-temperature and high-wind seasons, restrict the dense stacking of high-risk cargo, and strengthen real-time monitoring of temperature and humidity to mitigate environmental amplification effects.

- (4)

- Promote peacetime-emergency integration in resilient infrastructure development by maintaining emergency access routes and reserve resources during regular operations to minimize response delays.

- (1)

- Transfer learning applications, where the trained STGNN can be adapted to other ports with limited incident data through domain adaptation techniques, requiring only modest retraining on local facility configurations.

- (2)

- Integration with digital twin systems, where the framework could provide real-time resilience forecasting by processing live operational data and generating predictive disaster scenarios for proactive risk management.

- (3)

- Extension to multi-port network analysis, modeling cascading disruptions across connected ports in regional supply chains.

- (4)

- Integration of real-time decision support, where the intervention simulation capability could be deployed in emergency operation centers to evaluate response strategies during actual incidents. These extensions would significantly enhance the practical impact and generalizability of our methodology.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, L.; Su, W.; Liao, S.; Wang, S. Enhancing energy security through multi-scale network analysis: Robustness in global crude oil shipping–trade networks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2026, 265 Pt A, 111525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, X.; Yang, D. Port vulnerability to natural disasters: An integrated view from hinterland to seaside. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2025, 139, 104563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, M.; Zuo, L.; Xi, M.; Li, S.; Wang, Z. Risk assessment of marine disasters in fishing ports of Qinhuangdao, China. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2023, 60, 102832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Maalouf, N.J.; Mouawad, C. Assessing the impact of the Beirut port explosion on supply chain management and seaport infrastructure in Lebanon: A pathway to resilience and reform. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 32, 101555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, J.-H.; Tseng, P.-H. Exploring the ship operation safety indicators of international ports in Taiwan. Marit. Transp. Res. 2024, 6, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.; Garg, H.; Kousar, M. An industrial disaster emergency decision-making based on China’s Tianjin city port explosion under complex probabilistic hesitant fuzzy soft environment. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123 Pt B, 106400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, K.; Fu, X.; Jiang, C.; Zheng, S. How would co-opetition with dry ports affect seaports’ adaptation to disasters? Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 130, 104194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Chen, Y.; Gu, S.; Vanelslander, T. Leveraging structural topic modeling to compare “Green Port” research and practice. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 86, 104196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, J.; Tu, M.; Naseem, M.H. Comprehensive assessment of port resilience: A three-stage cycle approach. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 86, 104170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Song, Y.; Huang, H.; Niu, W.; Zhang, C. Assessment of port resilience based on Evidential Reasoning and Bayesian network: An improved framework by segmenting the metrics across time and performance dimensions. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 262, 111172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Tian, Y.; Li, J. Revealing spatiotemporal connections in container hub ports under adverse events through link prediction. J. Transp. Geogr. 2025, 125, 104198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xie, J.; Wang, X.; Mei, Z.; Cai, N. A digital Twin-based bi-directional deduction method for the full-pose of the Floating connection mechanism. Measurement 2024, 224, 113905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Yang, Z. Resilience assessment: Insights from port community structures across the global container shipping network. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2026, 265 Pt A, 111489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Ma, X.; Han, Y.; Xue, G.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y. Resilience analysis and recovery strategy for interdependent automated container port networks under cascading failures. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2026, 265 Pt A, 111495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Shi, L.; Ma, Z. An assessment of shipping network resilience under the epidemic transmission using a SEIR Model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polydoropoulou, A.; Velegrakis, A.; Papaioannou, G.; Karakikes, I.; Bouhouras, E.; Thanopoulou, H.; Chatzistratis, D.; Monioudi, I.; Moschopoulos, K.; Chatzipavlis, A. A composite port resilience index focused on climate-related hazards: Results from Greek ports’ living-labs. Marit. Transp. Res. 2025, 9, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Suo, M.; Fan, H.; Wang, J.; Lai, W. Port resilience assessment under congestion disruptions. J. Sea Res. 2025, 207, 102611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Zhou, C.; Shen, Y.; Chew, E.P.; Tan, K.C. Optimizing port system resilience through integrated preparedness. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2026, 266, 111770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, G.-S.; Gina, G.; Daniel, R.-R. A Bayesian network and DEMATEL-ISM based approach for evaluating resilience: A case study in inland waterway port. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2025, 270, 107881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Gong, D. Multiscenario deduction analysis for railway emergencies using knowledge metatheory and dynamic Bayesian networks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 255, 110675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Shi, M.; Li, Z.; Liu, B. Analysis of risk evolution mechanisms for hydrogen leakage in HECS: A dynamic Bayesian network and scenario deduction approach. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 163, 150804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Meng, F.; Bi, H. Scenario deduction of explosion accident based on fuzzy dynamic Bayesian network. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2025, 96, 105613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Hua, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhai, Z. Spatiotemporal polynomial graph neural network for anomaly detection of complex systems. Measurement 2024, 235, 115035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, Y. Data-driven static and dynamic resilience assessment of the global liner shipping network. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 161, 102661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zeng, W.; Luo, J.; Nan, G. An analysis of port congestion alleviation strategy based on system dynamics. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 229, 106336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, P.; Shuai, B.; Zhang, R.; Wang, B. STCAGNN-RNKDE: A traffic accident prediction model for spatiotemporal combinatorial attention graph neural networks using Ripley’s K and network kernel density estimation. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 265, 111593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wei, C.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Yuan, H. Assessing port cluster resilience: Integrating hypergraph-based modeling and agent-based simulation. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 137, 104485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisurin, P.; Pimpanit, P.; Jarumaneeroj, P. Evaluating the long-term operational performance of a large-scale inland terminal: A discrete event simulation-based modeling approach. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0278649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Liu, X. Data-driven approach for port resilience evaluation. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 186, 103558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuong, T.N.; Long, L.N.B.; Kim, H.-S.; You, S.-S. Data analytics and throughput forecasting in port management systems against disruptions: A case study of Busan Port. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2023, 25, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.U.; Yin, J.; Asad, M.; Alomayri, T.; Jameel, M. Predicting seaport disruptions from natural hazards using automated machine learning. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 213, 117610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Z.; Dong, Y.; Li, W.; Ding, R.; Wang, Q.; Li, J. Harnessing large language models for disaster management: A survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.06932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; Song, S.; Dang, K.; Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; et al. Qwen2. 5-vl technical report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.13923. [Google Scholar]

| Node Category | Extracted Attributes |

|---|---|

| Infrastructure (Containers, Quay Cranes, Vessels, Roads, Water Areas) | ID, Type, Spatial Coordinates, Geometric Extent, Status Label, Damage Ratio, Functional Index |

| Response Units (Emergency Vehicles, Personnel, Fire Stations) | ID, Type, Real-time Location, Status (Standby/Deployed/Operating), Service Range, Available Resources |

| Environmental Factors (Wind Speed, Wind Direction, Temperature) | Real-time Measurements, Alert Thresholds, Amplification Coefficient for Disaster Propagation |

| Management Variables (Global Parameters) | Regulatory Intensity (0–1), Emergency Response Level (I–IV), Misdeclaration Type, Misdeclaration Deviation Rate |

| Symbol | Description | Type/Range | Related Equations |

|---|---|---|---|

| i, j | Indices of nodes in DHSG | Integer | (3), (4), (13) |

| t | Discrete time step | t = 0, 1, …, T | (1)–(3), (5)–(9), (13)–(18) |

| G(t) | Dynamic heterogeneous spatiotemporal graph | Graph | Section 3.2, (4) |

| vi | Node i in DHSG | Node | (3), (4), (13) |

| Statusi(t) | Operational status of node i | Categorical | (3) |

| xi | Static node attributes | Feature vector | (3) |

| DamageAreai(t) | Damaged area at time t | Real ≥ 0 | (1) |

| TotalAreai | Geometric area of node i | Real > 0 | (1) |

| DamageRatioi(t) | Damage ratio of node i | [0, 1] | (1), (2) |

| FIi(t) | Functional index of node i | [0, 1] | (2), (13) |

| FI^i(t + 1) | Predicted functional index | [0, 1] | (11), (12) |

| Hidden node feature in layer l | Vector | (4) | |

| R | Set of edge types | Finite set | Section 3.2.2 |

| Nr(vi) | Neighbor set under edge type r | Set | (4) |

| Edge-type weight matrix | Matrix | (4) | |

| eij, aij | Edge weight and attention coefficient | Real | Section 3.3.1 |

| zt | GRU hidden state | Vector | (5)–(8) |

| ct | TCN output | Vector | (9) |

| Fused spatiotemporal feature | Vector | (10) | |

| α | Attention weight | [0, 1] | (10) |

| S(t) | System functionality | [0, 1] | (13), (16) |

| SFDI(t) | System Function Degradation Index | [0, 1] | (14)–(18) |

| PRL | Peak Resilience Loss | [0, 1] | (15) |

| RT | Recovery Time | Hours ≥ 0 | (16) |

| RA | Resilience Area | Real ≥ 0 | (17), (18) |

| ai(t) | Intervention indicator | {0, 1} | Section 3.4.4 |

| ri | Recovery rate | (0, 1] | Section 3.4.4 |

| Δt | Time step size | Δt = 1 h | (18) |

| Node Type | Response Resource | Recovery Rate ri |

|---|---|---|

| Ship (on fire) | Fireboat | 0.20 |

| Container (collapse) | Clearance vehicle | 0.15 |

| Quay Crane (damaged) | Maintenance crew | 0.08 |

| Road (blocked) | Clearance vehicle | 0.40 |

| Water Area (oil spill) | Oil recovery vessel | 0.10 |

| Intervention Strategy | PRL | RT (Hours) | RA |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Intervention | 0.62 | 18.2 | 10.84 |

| Random Intervention | 0.61 | 14.7 | 8.92 |

| Centrality-Priority Intervention | 0.60 | 10.5 | 6.37 |

| Path-Blocking Intervention | 0.58 | 11.8 | 7.01 |

| Environmental Variable | Level | PRL | RT (Hours) | RA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wind Speed | 3 m/s | 0.59 | 11.9 | 7.93 |

| 8 m/s | 0.65 | 14.1 | 9.87 | |

| 12 m/s | 0.71 | 16.4 | 11.02 | |

| Temperature | 25 °C | 0.60 | 12.1 | 8.78 |

| 35 °C | 0.66 | 15.3 | 11.27 |

| Misdeclaration Type | Deviation Rate | PRL | RT (Hours) | RA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category Misdeclaration | 10% | 0.58 | 13.4 | 6.42 |

| 30% | 0.72 | 17.6 | 9.81 | |

| 50% | 0.82 | 19.3 | 12.38 | |

| Weight Misdeclaration | 10% | 0.56 | 12.8 | 5.91 |

| 30% | 0.68 | 15.2 | 8.47 | |

| 50% | 0.75 | 18.9 | 9.96 | |

| Temperature-Control Misdeclaration | 10% | 0.54 | 12.5 | 5.73 |

| 30% | 0.65 | 14.8 | 7.82 | |

| 50% | 0.71 | 16.5 | 8.83 |

| Regulatory Intensity ρ | Response Level | PRL | RT (Hours) | RA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3 | Level II | 0.71 | 16.8 | 11.52 |

| Level III | 0.69 | 14.9 | 10.18 | |

| Level IV | 0.67 | 12.6 | 8.87 | |

| 0.5 | Level II | 0.66 | 15.3 | 10.34 |

| Level III | 0.64 | 13.7 | 9.02 | |

| Level IV | 0.62 | 12.1 | 8.01 | |

| 0.7 | Level II | 0.62 | 13.2 | 8.12 |

| Level III | 0.60 | 12.4 | 7.35 | |

| Level IV | 0.58 | 11.4 | 7.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, B.; Weng, Y.; Xia, L. Port Resilience Assessment for Misdeclaration Induced Disasters Using a Hybrid LLM-GNN Framework. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2280. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122280

Song B, Weng Y, Xia L. Port Resilience Assessment for Misdeclaration Induced Disasters Using a Hybrid LLM-GNN Framework. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2280. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122280

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Bo, Yanjun Weng, and Laiqun Xia. 2025. "Port Resilience Assessment for Misdeclaration Induced Disasters Using a Hybrid LLM-GNN Framework" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2280. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122280

APA StyleSong, B., Weng, Y., & Xia, L. (2025). Port Resilience Assessment for Misdeclaration Induced Disasters Using a Hybrid LLM-GNN Framework. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2280. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122280