Abstract

Shallow gas drilling in polar seas poses severe geological hazards, particularly unexpected eruptions that threaten platform safety and the marine environment. Accurate prediction of shallow gas occurrence and eruption risk is therefore essential for safe deep-water operations. However, previous studies seldom considered the coupled effects of gas pressure and pore-structure evolution on acoustic wave velocity, leading to deviations in hazard assessment. In this study, laboratory experiments and numerical simulations were conducted to clarify these mechanisms. Results revealed a non-monotonic relationship between porosity and P-wave velocity in shallow gas-bearing sediments: P-wave velocity decreases with increasing porosity at low porosity levels but increases beyond a critical threshold. This is attributed to changes in particle interactions and cementation that enhance the shear modulus. The inflection porosity for shallow gas (78%) highlights the diagnostic role of pore-structure evolution in predicting shallow gas distribution. A mathematical correlation between P-wave velocity and formation pressure was further established, and MP-PIC simulations showed that higher pressure coefficients significantly accelerate eruption rates, with a 0.1 increase in the pressure coefficient raising the instantaneous eruption velocity by 5.27 m3/min. Based on these findings, a quantitative evaluation method was developed to assess shallow gas hazard risk, providing engineering guidance for site selection and real-time risk prediction, and contributing to safer offshore drilling and ecological protection in polar environments.

1. Introduction

The vast potential of deep-water oil and gas resources, along with the substantial economic benefits they offer, has driven over 60 countries to engage in the competition for their development [1,2,3]. However, due to the extremely harsh construction environment in the polar sea, drilling in the polar sea is much more difficult than that in continental land [4,5]. According to statistics from the Norwegian Petroleum Safety Administration, 60% of deep-water drilling accidents are linked to surface drilling, with shallow geological hazards being an important reason for many of these incidents [6].

The shallow stratum is close to the seabed. Once a shallow gas accident occurs, it is easy to form a kick before the workers can react. If improper follow-up measures are applied, it can escalate into a blowout, igniting the entire platform and contaminating the surrounding sea, severely damaging the fragile polar marine ecosystem and leading to catastrophic consequences. The density of drilling fluid in shallow formations is difficult to design and control. High-density fluids can lead to mud loss, while low-density fluids are risky to cause a gas kick or even blowout when encountering shallow gas [7]. According to the International Coastal Exploration Council, 22% of blowout events are caused by shallow gas [8]. Once the shallow gas is drilled through without proper handle, it may cause a blowout in the wellhead, resulting in platform fire and other accidents.

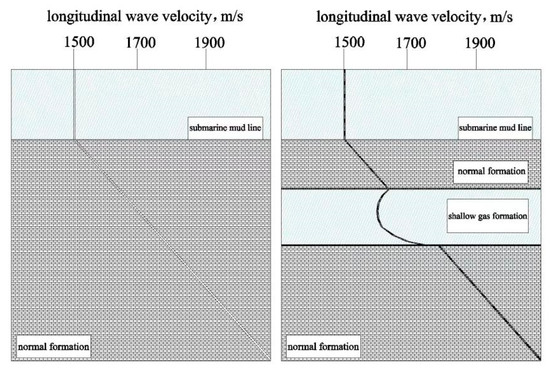

Shallow gas generally refers to overpressured gas accumulated within 800 m below the seabed, which is difficult to exploit as a gas resource [9,10]. Due to its difficult prediction, shallow burial, high pressure, fast eruption speed, and limited means to mitigate it, shallow gas poses a significant risk of major operational accidents, such as well blowouts or platform submersion. As shown in Figure 1, shallow gas mainly exists in the form of “gas”, which changes the litho-physical properties of the formation and forms a multi-phase mixture consisting of cap rock, mud, fluid and gas, thus significantly changing the propagation velocity law of longitudinal wave [11,12]. Generally, the velocity of longitudinal waves in shallow gas-bearing formations is between 800 and 1000 m/s, 20% to 50% lower than that in normal formations [13,14,15]. Currently, the identification of shallow gas mainly relies on qualitative identification through characteristics of “gas chimney”, “bright spot reflection”, and “blank band” in three-dimensional high-precision seismic section [16,17,18]. However, a quantitative identification method for shallow gas pressure is still lacking, which is of greatest concern in drilling operations [19].

Figure 1.

Characteristics of longitudinal wave propagation in different strata of the polar sea.

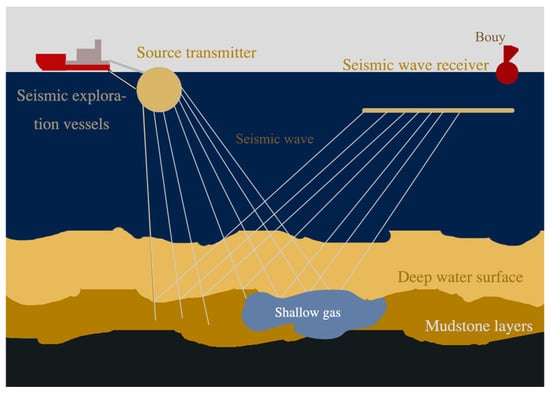

The principle of seismic exploration in deep-water is shown in Figure 2. According to the propagation velocity difference in seismic waves, i.e., longitudinal waves, in different media, the location of shallow gas can be identified. Based on the theory of acoustic wave propagation and consideration of the characteristic of shallow soil, gas-acoustic experiments of the shallow gas layer were conducted [19]. These experiments revealed that the propagation speed of acoustic waves increases with rising pressure and decreases with increasing porosity in shallow gas layers. Xu et al. (2023) investigated the seismic reflection characteristics and controlling factors of natural gas in the oblique morphology along the East China Sea using seismic profile data and drill core data [20]. Ferrante et al. (2022) constrained the seismic interpretation using six exploratory wells to lithologically characterize stratigraphic succession [21]. He et al. (2023) have developed a sound wave signal decomposition method that combines synchronous squeezing transform and empirical mode decomposition, which can be used for the comprehensive simulation of soil damage caused by dynamic loads [22]. Multi-channel seismic data were processed to identify the shallow gas formation. Kima et al. (2020) also used seismic data and AVO (Amplitude Versus Offset) processing to identify shallow gas [23]. Chen et al. (2020) used high-resolution chirped sonar profiling technology to study the natural gas anomalies in the Yangtze underwater delta and its distal mud wedge, and drew a shallow natural gas distribution map [24]. Numerical simulation methods can provide a more quantitative and intuitive analysis of shallow gas eruptions. Lei et al. (2022) established a numerical model for calculating the volume of gas invasion based on the theory of gas water two-phase flow [25]. This model involves the influence of drilling process and analyzes the factors that affect gas invasion. Long et al. (2023) simulated the flow patterns of shallow gas in ultra-deep-water areas and studied the mechanism and feasibility of shallow gas release [26]. Sun et al. (2025) have studied the gas migration laws and morphological changes in submarine sandy sediments through simulation experimental methods, and found that in submarine fine-grained sediments, gas migration follows the particle displacement mode [27]. Cao et al. (2023) used neural networks to analyze a large amount of valuable full-size seismic data and studied shallow gas hazard risk assessment [28].

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of deep-water seismic exploration principle.

Existing studies in the field of shallow gas exhibit shortcomings in several aspects: first, the identification of shallow gas mainly relies on qualitative methods based on features such as “gas chimneys”, “bright spot reflections”, and “blank zones” in 3D high-precision seismic profiles, lacking quantitative identification methods for shallow gas pressure—which is of primary concern in drilling operations; second, although there is a correlation between the wave velocity and pressure of shallow gas-bearing formations, previous studies rarely consider the influence of shallow gas pressure on wave velocity, leading to significant deviations in the results of shallow gas localization and hazard prediction; third, while existing studies have explored shallow gas from perspectives such as seismic data processing, numerical simulation, and experimental analysis, they have not yet systematically established a mathematical relationship between shallow gas pressure and P-wave propagation velocity, nor have they formed a complete technical scheme integrating pressure prediction and hazard assessment. As a result, these studies can hardly provide effective support for the safety requirements of shallow gas drilling operations in polar marine areas.

This study aims to investigate and study the mathematical relationship between P-wave propagation velocity and pressure in shallow gas formations through laboratory experiments. It innovatively revealed the recognition mechanism of aeroacoustics characteristics in shallow gas formations, focusing on the influence of gas pressure and buried depth on the propagation velocity of P-wave. A shallow gas pressure prediction chart is established. Next, the impact of different formation pressures on shallow gas geological disasters is analyzed by MP-PIC (Multi-phase Particle-in-Cell) discrete element simulation method. Finally, this study provided a method to predict the location and pressure of shallow gas from seismic data, evaluate its potential geological disaster level, and propose preventative measures. These insights will enhance the safety of shallow gas drilling in polar seas.

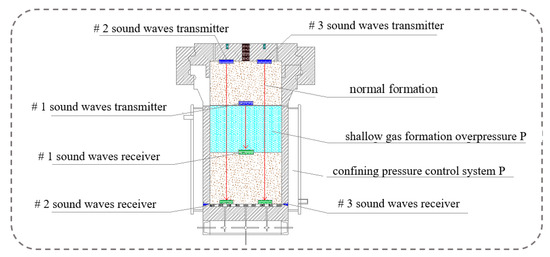

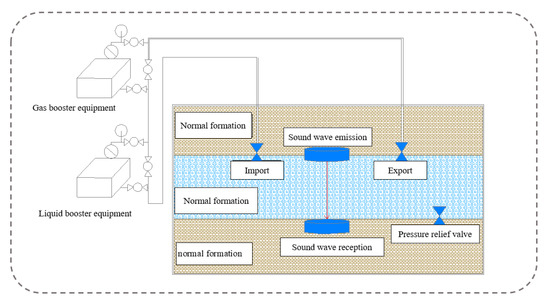

2. Experiment on Sound Wave Characteristic Recognition of Gas–Geological Disasters in Polar Sea Shallow Layer

Based on the similarity principle, this study conducted laboratory simulation experiments on the acoustic characteristics of shallow gas in polar cold seas. A high-pressure and low-temperature sealed reactor was used to simulate the polar cold sea operating environment, while confining pressure was applied to simulate different operating water depths and overlying rock formation pressures. Saturated sand-clay mixed soil was laid inside the reactor to mimic the seabed stratum, and a sealed high-pressure airbag capable of quantitatively filling gas and water was implanted in it to simulate shallow gas. The abnormal high pressure of shallow gas was simulated by adjusting the pressure inside the high-pressure airbag, and an acoustic detection system was used to measure the propagation velocity of P-wave in the normal stratum and shallow gas airbags with different pressure levels; the schematic diagram of the experimental system is shown in Figure 3. Shallow gas belongs to abnormal high-pressure strata. According to the principle of predicting abnormal high pressure based on the undercompaction theory, there is a certain mathematical relationship between its pressure and P-wave velocity. Using the data obtained from the experiments, a fitting mathematical model between the pressure level of shallow gas-bearing strata and P-wave velocity was established, as shown in Equation (1):

where is the velocity of longitudinal waves, m/s; is the confining pressure applied to the autoclave, MPa; is the overpressure in the airbag, MPa.

Figure 3.

Experimental system and schematic diagram of shallow gas-sound wave characteristic recognition.

2.1. Experimental Equipment

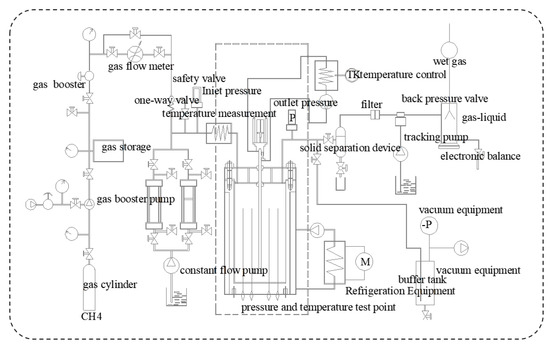

The experiment was primarily conducted using a self-developed simulation apparatus by China University of Petroleum-Beijing (Beijing, China), which is designed to identify the acoustic characteristics of shallow geological hazards in polar seas. This experimental device comprises several key components, including a high-pressure, low-temperature autoclave capable of simulating conditions of −30 °C and 30 MPa, an embedded pressure-sealed airbag for controlled pressure, a low-temperature and constant-temperature water bath system, a confining pressure control system, a gas injection and liquid supply system, an acoustic detection system, and a data acquisition and processing system. Field photographs and the overall schematic of the experimental device are presented in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 4.

On-site photo of the experimental device.

Figure 5.

Overall flow chart of the experimental device.

- (1)

- High-pressure and low-temperature reactor

The high-pressure reactor is a cylindrical container with an inner diameter of 0.5 m, a height of 1.5 m, and an effective volume of 129.5 L. It has a maximum static pressure-bearing capacity of 30 MPa and is mainly used for preparing simulated strata containing shallow gas and hydrates. The temperature of the reactor is controlled by a low-temperature constant-temperature water bath, with a temperature control range of −30 °C to 30 °C and a control accuracy of 0.5 °C. A confining pressure control system is installed around the reactor, which can apply a maximum confining pressure of 20 MPa to simulate different operating water depths and overlying rock formation pressures. Inside the reactor, 125 temperature measurement points are arranged, and PT100 platinum resistance temperature sensors are used to measure the temperature field distribution inside the reactor. These sensors have a measurement range of −30 °C to 100 °C and an accuracy of 0.25% FS. Additionally, 3 pressure measurement points are arranged to measure the internal pressure of the reactor, and the pressure sensors have a measurement range of 0 to 30 MPa and an accuracy of 0.1% FS.

- (2)

- Implantable pressure-controllable sealed airbag

The implantable pressure-controllable sealed airbag is a cylindrical sealed envelope with a size of Φ 0.5 m × 0.3 m. The envelope boundary must have both good sound transmission performance and a certain degree of structural strength. Since the propagation velocity of P-wave in an iron shell is extremely high (usually over 5000 m/s), P-wave, once excited, will first propagate rapidly along the iron shell. The superimposed waveform makes it difficult to identify the acoustic signal of P-wave passing through the medium inside the shell. In contrast, P-wave propagate slowly in rubber materials; moreover, rubber materials not only have excellent sound transmission performance but also strong pressure resistance, so they are often used to manufacture components of acoustic testing instruments. Therefore, neoprene rubber is selected as the material for the envelope boundary of the sealed airbag.

Sand-clay mixed soils with different porosities and densities were compacted, encapsulated, and then implanted into the high-pressure and low-temperature reactor. The envelope is equipped with a valve connected to the interior of the reactor: opening the valve can make the pressure and temperature of the airbag consistent with those inside the reactor; closing the valve allows high-pressure gas to be injected into the sealed envelope using a high-pressure gas flowmeter for pressurization, so as to simulate the overpressure environment of shallow gas. The high-pressure gas flowmeter has a pressurization range of 0 to 10 MPa, a flow rate range of 0 to 2000 mL/min, and a control accuracy of 0.2% FS. Acoustic transmitting and receiving probes were fixed at the top and bottom of the airbag via metal ejector rods to measure the propagation velocity of P-wave in the shallow gas-bearing soil. The working principle of the implantable pressure-controllable sealed airbag is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Implantable controllable pressure-sealed airbag.

The structure of the acoustic wave detection system is illustrated in Figure 7. As part of a simulation apparatus designed to identify the acoustic characteristics of shallow geological hazards in polar seas, the system is independently developed by China University of Petroleum-Beijing (Beijing, China). Its hardware components mainly include an acoustic wave transducer, a single-pulse acoustic wave transmitting card, and a CompuScope1400 data acquisition card. The waveform processing software provides several key functions:

Figure 7.

Structure schematic diagram of sound wave detection system.

- It enables real-time collection and storage of P-wave and S-wave waveforms, as well as the capability to perform spectrum analysis;

- The system allows for remote storage and retrieval of waveform analysis data (including longitudinal and transverse wave velocity, amplitude, frequency, and other parameters) via a database;

- It provides a graphical display of the collected waveforms, their spectra, and the analyzed data.

2.2. Experimental Procedures

- (1)

- Preparation of simulated strata containing shallow gas

Since sufficient undisturbed soil could not be obtained for the experiment, remolded soil was used in this study. To ensure the physical and mechanical properties of the prepared soil were consistent with those of the shallow strata in polar cold seas, the soil parameters obtained from core samples of shallow soil layers in the sub-Arctic Sakhalin block (as shown in Table 1) were referenced based on previous research findings. The physical property indices of the test sand, including particle gradation, dry density, and water content, were controlled to make the soil approximate the actual soil conditions of the shallow layers in polar cold seas.

Table 1.

Shallow Soil Parameters of the Sakhalin Block.

In this experiment, the porosity and density of the simulated strata and the soil inside the airbag were controlled by adjusting the particle gradation, compaction degree, and water content of the test soil. Based on the porosity and density range of shallow soils in polar cold seas, the weight method was adopted to prepare simulated shallow gas strata with different porosities (30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, and 80%). The specific porosity and density parameters are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Data of simulated formation porosity and density.

- (2)

- Measurement of P-wave velocity in shallow gas under different pressure levels

After the soil inside the reactor and the envelope was prepared, the acoustic transducers on the reactor and the airbag were fixed, followed by closing the reactor lid. The temperature inside the reactor was lowered to 1~2.5 °C (the seabed temperature of polar cold seas) using a low-temperature constant-temperature water bath. A confining pressure ranging from 2~16 MPa was applied to the reactor to simulate different operating water depths and overlying rock formation pressures. Once the confining pressure was applied, high-pressure gas was injected into the sealed airbag via a high-pressure gas flowmeter to increase the pressure, with the injected gas pressure levels ranging from 0.5 MPa to 10 MPa. The acoustic measurement system was calibrated, and the P-wave velocities of shallow gas under different confining pressures and shallow gas overpressure conditions were tested, respectively. Under the same conditions, each group of experiments was repeated 3 times to reduce uncertainties.

- (3)

- Experimental data processing

The accuracy of sound velocity calculation depends on the precise identification of the arrival time of the first arrival wave of the acoustic signal. The first arrival wave refers to the moment when the acoustic signal reaches the receiving transducer—when no acoustic signal is received, the signal exhibits a smooth baseline; at the moment of reception, the signal amplitude changes sharply and the waveform distorts, and this distortion point is the arrival time of the first arrival wave. Manual visual reading of this time is prone to large errors, so the wavelet analysis method was introduced for data processing: as a time–frequency localization analysis method, wavelet analysis can perform multi-scale analysis of acoustic signals. By utilizing the modulus maximum feature of the wavelet transform coefficient at the waveform mutation point when the acoustic wave reaches the transducer, the position of the mutation point can be detected, and then the accurate arrival time of the first arrival wave can be obtained, providing a reliable data basis for sound velocity calculation.

In the formula: the function Ψ(t) is the wavelet mother function; Ψ(t) is the conjugate function of Ψ(t); u is the translation parameter in wavelet transform; s is the scale parameter in wavelet transform.

After the time t is obtained via wavelet transform, the P-wave velocity can be calculated since the thickness of the simulated stratum is known:

In the formula: h is the stratum thickness, in meters (m); t is the propagation time of the acoustic wave in the stratum, in microseconds (μs).

3. Pressure Prediction of Shallow Gas

3.1. Effect of Porosity on P-Wave Propagation Velocity

Deep-water surface sediments are typically composed of unconsolidated clays and sandy soils, which become highly saturated under long-term seawater immersion. This saturation weakens the sediment framework and increases porosity, making their physical and mechanical properties strongly dependent on density, porosity, and clay content. From the perspective of porous media physics, these parameters exert a direct influence on the propagation of longitudinal acoustic waves. In relatively stable depositional environments without shallow gas, shallow water flows, or gas hydrates, the density and porosity of sediments remain nearly constant, resulting in stable P-wave velocities. However, once abnormal fluids or hydrate phases are present within the pore system, the pore geometry and connectivity undergo substantial variations, leading to changes in density and mechanical integrity. Such modifications significantly alter P-wave velocities, thereby providing an acoustic signature of pore-scale heterogeneity. Consequently, the coupling between longitudinal wave velocity and pore structure evolution not only reflects the microscale mechanics of saturated marine sediments but also offers a quantitative indicator for identifying shallow gas, shallow water flow, and hydrate-bearing strata in nanoporous marine environments.

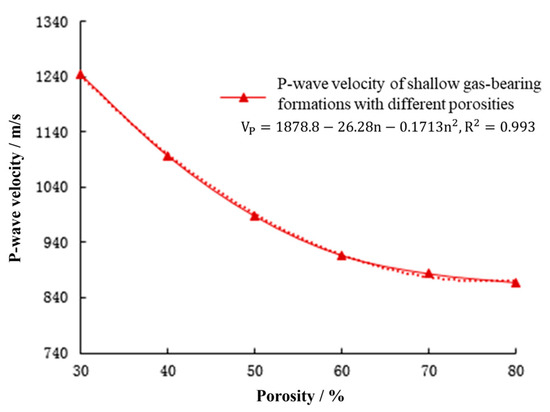

P-wave propagation velocity measurements were conducted on shallow gas simulation formations with porosities of 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, and 80%, respectively, under the temperature and pressure conditions of 0 °C and 25 MPa. Ten sets of data were measured for each porosity, and the weighted average of each set of measurement results was calculated. The experimental results are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

P-wave propagation speed in shallow gas formations with different porosities.

The experimental results show that the porosity of formations containing shallow gas and shallow water flow exhibits a non-monotonic quadratic relationship with P-wave propagation velocity. The reason is that in the low porosity stage, the increase in pores destroys the skeleton continuity, and the wave velocity decreases rapidly with the increase in porosity. As the porosity further increases, the decreasing rate slows down due to the stable particle contact state and balanced fluid effect, eventually showing a quadratic function-type non-monotonic decreasing characteristic. The fitting curve of P-wave propagation velocity and formation porosity is obtained with R2 = 0.993. With the increase in porosity, the P-wave velocity gradually decreases; when the porosity reaches a certain critical value, the P-wave velocity starts to increase.

It can be found from the curve of formation porosity versus P-wave propagation velocity that the porosity corresponding to the turning point of P-wave velocity in shallow gas-bearing formations is 76.71%. At this porosity, the P-wave propagation velocity tends to stabilize with the increase in formation porosity, so this point is defined as the inflection point of porosity. The cause of this phenomenon is that the increase in porosity changes the Coulomb force and van der Waals force between solid skeleton particles, and affects the cementation of sediments, resulting in the increase in shear modulus and thus the increase in acoustic velocity.

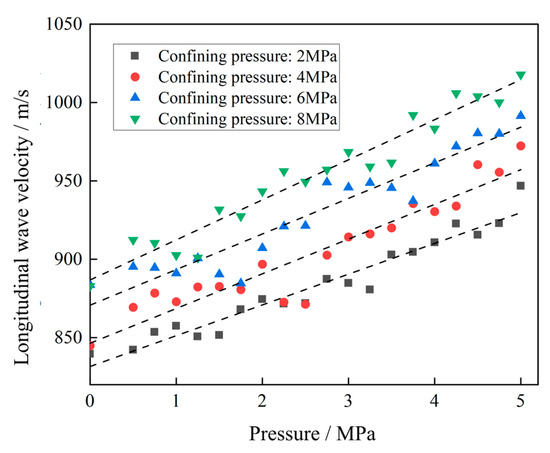

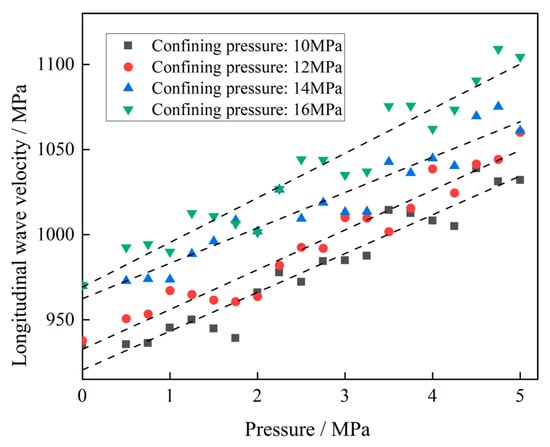

3.2. Relation Between Shallow Gas Pressure and P-Wave Velocity

Based on the experimental results, the relationships between P-wave velocity and shallow gas pressure under different confining pressures were established, as shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10. Under the same confining pressure, the P-wave velocity shows an approximately linear increasing trend with the increase in shallow gas pressure—for every 1 MPa increase in the average shallow gas pressure, the sound velocity increases by about 1.25% to 3.5%. The least squares method was used to fit the shallow gas pressure and P-wave velocity under different confining pressures, and the established mathematical model of shallow gas pressure-P-wave velocity is shown in Equation (6):

Figure 9.

Shallow gas pressure with confining pressure of 2~8 MPa in relation to longitudinal wave velocity.

Figure 10.

Shallow gas pressure with confining pressure of 10~16 MPa in relation to longitudinal wave velocity.

3.3. Quantitative Forecast Chart of Shallow Gas Pressure

The model for calculating the overburden pressure of shallow gas-bearing formation in the polar sea is shown in Equation (7):

where is the overlying pressure of shallow gas, MPa; is the height from the turntable surface to sea level, m; is the depth from sea level to underwater mud surface, m; is depth below mud surface to calculation point, m; is seawater density, is the density of rock layer, is the gravitational acceleration.

where is soil density at the mud surface, g/cm3; is the depth below the mud surface, m.

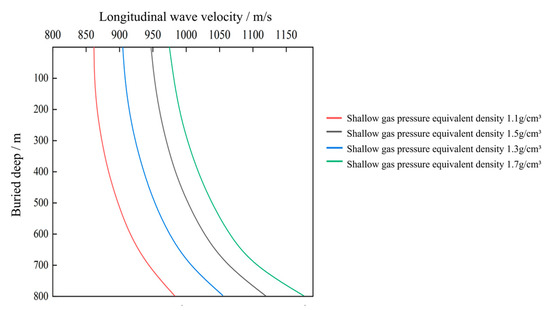

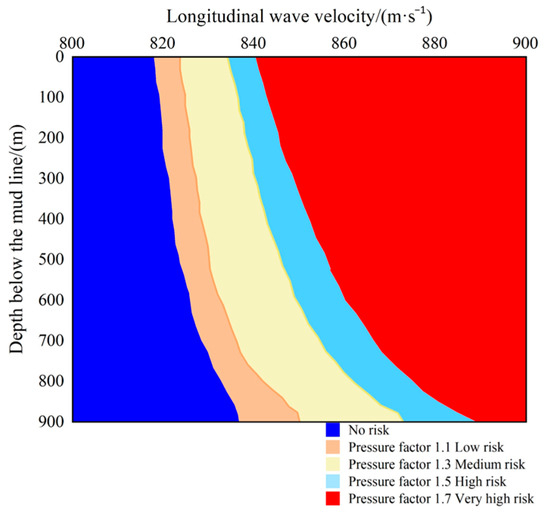

The overburden of the formation σv is approximately corresponds to the ambient pressure P in this experiment. Equations (7) and (8) are substituted into the fitting model of Equation (6) to obtain the model of longitudinal wave velocity varying with shallow gas pressure at different buried depths (Equation (9)). A quantitative prediction diagram of longitudinal wave velocity at different shallow gas pressures is established as shown in Figure 10.

where is shallow gas pressure equivalent density, g/cm3.

As shown in Figure 11, when the burial depth of shallow gas remains constant, the velocity of the longitudinal wave in shallow gas increases as pressure rises. Conversely, at the constant pressure, the longitudinal wave velocity also increases with greater burial depth, showing heightened sensitivity to depth variations. For example, when the pressure equivalent density increases by 0.2 g/cm3, the longitudinal wave velocity in shallow gas with a constant burial depth rises between 0.285% and 1%. Specifically, at depths less than 100 m, each 0.2 g/cm3 increase in pressure equivalent density results in a 0.285% increase in P-wave velocity. At a depth of 500 m, the same pressure increases lead to a 0.5419% rise in velocity, while at 800 m, it produces a 1% increase. When the pressure remains unchanged, the longitudinal wave increases by 2.13~6.19% with the increase in buried depth.

Figure 11.

Quantitative forecast profile of shallow gas pressure.

4. Numerical Simulation of Shallow Gas Eruption Risk Prediction

4.1. Numerical Model of Shallow Gas Eruption

MP-PIC discrete element simulation method [29,30] is used to model multi-phase mixtures consisting of caprock, mud, fluid, and gas in shallow gas formations. The motion of particles is described using the Lagrangian method. Instead of individual particle collisions, the particle phase pressure gradient force is applied to characterize the particle groups with the same dynamic characteristics. Therefore, this method significantly reduces the computational load, making it highly efficient for simulating large-scale particle systems.

Introducing continuous phase porosity of gas–solid two phases, continuous phase porosity in the control body is defined as :

where is the total volume of the k (k = 1, 2) phase particles in the control body; is the volume of the control body.

The continuity equation is [31]:

The momentum equation is:

where is the total number of calculated particles in the cell; is the true number of particles in the calculated particle; and are the volume of the particle and fluid cell, respectively; is the coefficient of drag force; and are the velocities of gases and calculated particles, respectively; is the corresponding pneumatic force.

The equation of motion of the solid phase is given below:

where is the solid phase pressure, is the maximum solid phase stacking fraction.

4.2. Geometric Model and Boundary Conditions

- (1)

- Geometric model

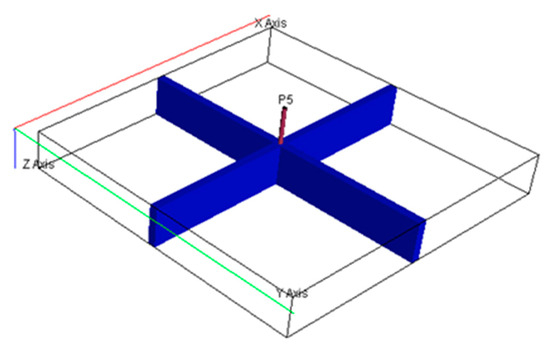

A geometric model was established using ANSYS Fluent 2023 R1 software. The target shallow gas reservoir is located 100 m below the seabed mudline, with a regular rectangular planar shape and specific dimensions of 50 m (length) × 40 m (width), corresponding to a total area of 2000 m2. The associated operating water depth is 200 m. The core parameters of the gas reservoir are set as follows: porosity = 0.5 and permeability = 2000 mD (millidarcies). To investigate the influence of reservoir thickness on mechanical responses, four thickness variables are designed: 5 m, 10 m, 15 m, and 20 m. Additionally, four pressure coefficient levels are established: 1.1, 1.3, 1.5, and 1.7. The established geometric model is shown in Figure 12, where the blue area represents the shallow gas-bearing formation model and the red arrows denote the wellbore fluid column pressure. A structured grid is adopted for meshing, with a planar grid density of 118 × 100 and a vertical grid size of 0.1 m. The time step is set to 0.0001 s, which is determined based on the critical time step calculated from particle characteristic size and wave velocity to avoid numerical oscillation. Based on the control equations of discrete element theory and combined with the actual geological conditions of the gas reservoir, the mechanical and flow boundaries of the model calculation domain are defined. Discrete element simulation is performed to analyze particle movement, stress transfer, and gas seepage behavior during the excavation disturbance of the gas reservoir.

Figure 12.

Geometric model of shallow gas formation.

- (2)

- Initial conditions

The initial particle porosity of shallow gas is 0.37. The bottom 3~25 cm is sand, and the rest space is air.

- (3)

- Boundary conditions

The lower and both sides of the model are sealed, and the upper opening is the outlet of borehole pressure, which is set as the liquid column pressure in the wellbore. The gas phase uses the wall slip-free condition, while the solid phase interacts with walls in an incomplete elastic collision.

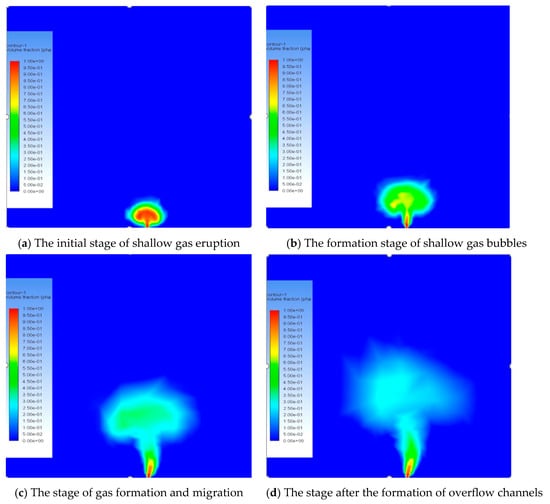

4.3. Analysis of Numerical Results

Figure 13 shows the continuous phase porosity distribution during the shallow gas eruption, with the shallow gas eruption time progressively increasing from Figure 13a to Figure 13d. Figure 13a shows the initial stage of shallow gas eruption: the gas velocity is low, and the soil particles have not been fluidized. At this stage, the gas flow can only change the pore between soil particles and form a certain pore pressure between particles. Gas can only seep through the gap of particles without bubbles. As the gas flow rate increases, pore pressure also rises. When the pore pressure equals the weight of the overlying soil particles, disturbances occur from the bottom up in the soil body. Due to the previous gas infiltration and the drag force exerted by gas flow, some soil particles start to move with the gas, the soil particles near the air inlet flow first, producing a phenomenon like liquefaction of sand, which is called “sand fluidization”. Gas bubbles are likely to form inside the sand due to the enhanced flow of sand. When bubbles form, the gas velocity and pressure reach their maximum critical values. As the sand fluidization occurs, the gas movement in the sand bed becomes fairly easy. Thus, as can be seen in Figure 13b, the gas moves to the soil surface in a very short time. With the continuous replenishment of gas, air bubbles gradually push the overlying sand away to form a passage through the top and bottom, and the pressure between the pores also decreases with the release of gas. In practice, when gas eruption in the reservoir is over, the pushed-off overlying sand will be re-deposited in the eruption channel under the action of gravity to fill the channel.

Figure 13.

Numerical simulation results of shallow gas eruption at different times.

Figure 13c is the stage of gas formation and movement. At this stage, the pore pressure distribution of gas in the soil layer is approximately circular from inside to outside. However, because the soil thickness is much smaller than the width of the box, the distribution of pore pressure far from the jet port is approximately elliptical. Figure 13d is the stage after the formation of the gas eruption channel. The overpressure air mass pushes the overlying soil mass apart, releases the gas, and the air pressure at the channel gradually returns to atmospheric pressure. Then, the air pressure in the soil particles around the channel is not released in time, which is higher than that at the channel. In actual working conditions, the soil in the pit is consolidated under the action of gravity after releasing the air pressure inside the voids.

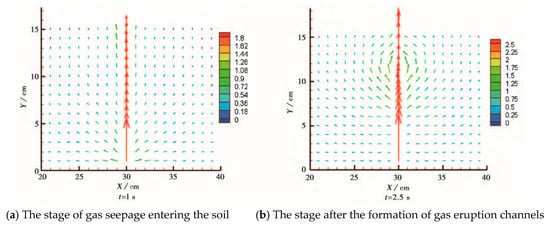

Figure 14 presents a vector diagram of gas velocity during shallow gas eruption, illustrating the direction of gas phase penetration and migration in the particles. In Figure 14a, gas enters the soil in the form of permeation. Because the permeability of the soil is isotropic in this stage, the gas velocity is radial. The closer the gas is to the borehole, the faster the gas velocity, and the greater the influence of gas pressure. Figure 14b depicts the stage after the formation of the gas eruption channel. At the base of the channel, most of the gas erupts from the channel at a high speed, with some portion entering the soil in the form of permeation. Even though the channel is connected with the atmosphere, the pore pressure is higher than the pressure in the wellbore when the pore pressure in the soil particles around the channel is not released in time. Therefore, gas in the soil around the upper half of the channel tends to move into the channel.

Figure 14.

Velocity vector diagram of shallow gas eruption.

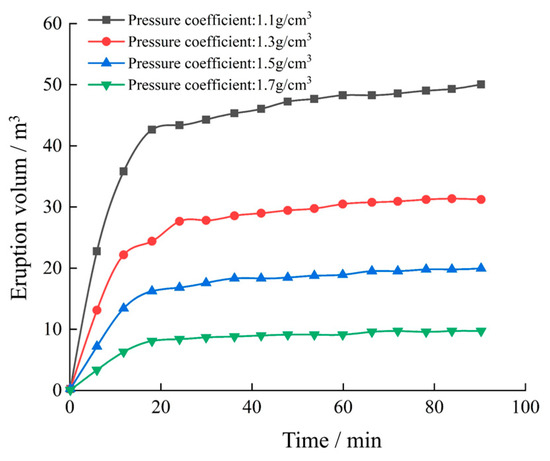

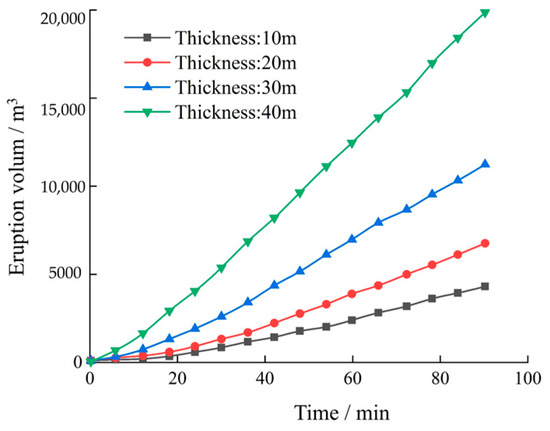

The results of numerical simulation in Figure 15 and Figure 16 show that: when the thickness of the shallow gas formation is only 5 m and the formation pressure coefficient is 1.1, the maximum instantaneous velocity can reach 7.13 m3/min. At this velocity, the sand containing gas poses a certain risk to the wellbore. When the pressure coefficient rises to 1.3, even with the same 5 m thickness, the instantaneous velocity of shallow gas can reach 18.77 m3/min, significantly elevating risk to the wellbore. For every additional 5 m increase in thickness, the instantaneous eruption velocity increases by 2.8 m3/min. With each 0.1 increase in the pressure coefficient, the instantaneous eruption velocity increases by 5.27 m3/min. The computed results show that the instantaneous eruption velocity of shallow gas is more sensitive to the change in shallow gas pressure. Therefore, according to the numerical simulation results, a shallow gas formation with a pressure coefficient higher than 1.1 can be defined as a low-risk shallow gas geological hazard. A shallow gas pressure coefficient higher than 1.3 is defined as a medium-risk shallow gas geological disaster. A shallow gas formation pressure coefficient higher than 1.5 is defined as a high-risk shallow gas geological disaster, and a shallow gas pressure coefficient higher than 1.7 is defined as a very high-risk shallow gas geological disaster.

Figure 15.

Influence of different pressure coefficients on instantaneous eruption velocity of shallow gas (the thickness of the shallow gas formation is 5 m).

Figure 16.

Influence of different shallow gas formation thickness on accumulated eruption volume of shallow gas (gas formation pressure coefficient is 1.1 g/cm3).

5. Risk Level Evaluation of Shallow Gas

Based on the analysis of the numerical simulation results, shallow gas formations contain significant amounts of overpressure gas. Upon drilling through the overlying formation, this gas infiltrates the wellbore and accumulates, forming a gas column. As the gas ascends, the decreasing hydrostatic pressure causes the gas column to expand rapidly, potentially leading to a blowout at the wellhead. Shallow drilling operations in polar seas differ significantly from conventional land-based drilling, as the shallow drilling stage typically employs open-circuit drilling. In these operations, a blowout preventer (BOP) system is not installed, and well control measures on the platform are limited. Given that shallow gas is located at a relatively shallow depth, a blowout could quickly reach the underwater wellhead, leaving operators with minimal time to implement well control measures, increasing the likelihood of catastrophic accidents. The risk accident tree for shallow gas well blowouts is shown in Figure 17. The primary causes of such blowouts include inaccurate pre-drilling predictions and failures in shallow dynamic well control.

Figure 17.

Risk fault tree of shallow gas drilling.

The fault tree for shallow gas blowout risks is shown in Figure 17. The main causes of such blowouts include inaccurate pre-drilling prediction and failure of dynamic shallow well control. Specifically, inaccurate pre-drilling prediction can be divided into failure to detect kick, human error, and ancient well failure, etc. Failure of dynamic kill operation can be categorized into failure to detect kick and incorrect drilling fluid configuration. During the drilling process in shallow gas-bearing formations, special attention should be paid to the above key risk nodes.

Based on the risk classification of shallow gas and the P-wave velocity prediction chart for shallow gas pressure levels shown in Figure 11, a shallow gas risk level assessment chart was established, as shown in Figure 18. According to the five risk levels in Figure 18, five-level control measures are recommended.

Figure 18.

Shallow gas risk grade evaluation chart.

The 1st level (“No risk”) requires no additional measures, and continuous drilling is recommended.

For the 2nd level “Low risk”, it is recommended to use heavier drilling fluids.

For the 3rd level “Medium risk” and 4th level “High risk”, the shallow gas should be released by drilling a pilot hole to open a small part of the shallow gas formation. Then, deep-water drilling operations can be normally carried out near the pilot hole.

For the 5th level “Very high risk”, it is recommended to avoid drilling through the shallow gas formation.

6. Conclusions

This study introduces a comprehensive quantitative assessment methodology for evaluating geological hazards associated with shallow gas drilling in polar marine environments. The research combines rigorous laboratory experiments with sophisticated numerical simulations, yielding several key conclusions:

- The greater the pressure coefficient of the shallow gas formation, the more rapid the eruption speed of the shallow gas, leading to a more severe geological disaster.

- The influence of gas pressure on the velocity of longitudinal waves is highly significant. Beyond a simple pressure–velocity correlation, the response of porous geological structures under varying gas pressures and the dynamic interaction between gas and pore networks together critically modify P-wave propagation characteristics. Experimental results demonstrate that for every 1 MPa increase in shallow gas overpressure (P0), the longitudinal wave velocity increases by 19.6 m/s, reflecting both pore-structure deformation and gas–solid coupling effects, which together underpin the predictive capacity of acoustic monitoring.

- By leveraging the P-wave velocity and the established mathematical correlation between this velocity and the pressure of shallow gas formations, we can quantitatively forecast the severity of geological disasters. Furthermore, we have proposed tailored mitigation measures for varying degrees of geological hazards, which are instrumental in enhancing the safety of shallow gas drilling operations in polar seas and safeguarding the delicate ecological balance of these regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.; Data curation, T.C.; Formal analysis, Y.Z.; Funding acquisition, L.L.; Investigation, S.W.; Methodology, L.L.; Project administration, L.L.; Resources, G.Z.; Supervision, L.L.; Validation, L.H.; Writing—original draft, Q.T.; Writing—review and editing, L.L., Y.S., G.Z. and T.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52404013), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant Number: 2025T180800) and Science Foundation of China University of Petroleum, Beijing (No. 2462025YJRC039). This research is also supported by the specific research fund of The Innovation Platform for Academicians of Hainan Province.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| velocity of longitudinal waves, m/s | |

| confining pressure applied to the autoclave, MPa | |

| overpressure in the airbag, MPa. | |

| overlying pressure of shallow gas, MPa | |

| height from the turntable surface to sea level, m | |

| depth from sea level to underwater mud surface, m | |

| depth below mud surface to calculation point, m | |

| seawater density, g/m3 | |

| density of rock layer, g/m3 | |

| gravitational acceleration, m/s2 | |

| soil density at the mud surface, g/cm3 | |

| depth below the mud surface, m | |

| shallow gas pressure equivalent density, g/cm3 | |

| total volume of the k (k = 1, 2) phase particles in the control body, cm3 | |

| volume of the control body, cm3 | |

| total number of calculated particles in the cell | |

| true number of particles in the calculated particle | |

| volume of the particle, cm3 | |

| volume of the fluid cell, cm3 | |

| coefficient of drag force | |

| velocities of gases, m/s | |

| velocities of calculated particles, m/s | |

| corresponding pneumatic force, Pa | |

| solid phase pressure, Pa | |

| the maximum solid phase stacking fraction |

References

- Yang, J.; Meng, W.; Yao, M.; Gao, D.; Zhou, B.; Xu, Y. Calculation method of riser top tension in deep water drilling. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2015, 42, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Calculation method of surface conductor setting depth in deepwater oil and gas wells. Acta Pet. Sin. 2019, 40, 1396–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, X.; Li, H.; Pang, H. Exploring the mysteries of deep oil and gas formation in the South China Sea to guide Palaeocene exploration in the Pearl River Mouth Basin. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2022, 6, 361–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yan, D.; Tian, R.; Zhou, B.; Liu, S.; Zhou, J.; Tang, H. Bit stick-out calculation for the deepwater conductor jetting technique. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2013, 40, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, D.; Fang, J. Finite element analysis of deepwater conductor bearing capacity to analyze the subsea wellhead stability with consideration of contact interface models between pile and soil. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2015, 126, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, N. Poromechanics II, new ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Xu, J.; Meng, L.; Hong, J. An Acoustic Approach to Identify Shallow Gas and Evaluate Drilling Risk in Deep Water Based on Simulation Experiment Study. In Proceedings of the 29th International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 16–21 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, D.R.; Zhang, Z.; Ray, B. Review of progress in evaluating gas hydrate drilling hazards. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2012, 34, 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Q.; Malinowski, M.; Kramarska, R.; Kaulbarsz, D.; Mil, L.; Hübscher, C. Gas-Escape features along the Trzebiatów fault offshore Poland: Evidence for a leaking petroleum system. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 156, 106431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.; Hassan, R.; Sherwani, F.; Soomro, Q.; Sohu, S.; Lakhiar, M. Oil and gas disasters and industrial hazards associated with drilling operation: An extensive literature review. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computing, Mathematics and Engineering Technologies (iCoMET), Sukkur, Pakistan, 30–31 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Jackson, D. Measurement of sound speed in fine-grained sediments during the seabed characterization experiment. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2019, 45, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachman, R. Estimating velocity ratio in marine sediment. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1989, 86, 2029–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevostianov, I. Gassmann equation and replacement relations in micromechanics: A review. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2020, 154, 103344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Kim, D.; Lee, G.; Kim, G.; Kim, S.; Seo, Y. Physical and acoustic properties of inner shelf sediments in the South Sea, Korea. Quat. Int. 2014, 344, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhanov, B.A.; Chuvilin, E.M.; Grebenkin, S.I. Effects of pore gas hydrate dissociation on physical properties of frozen soils due to thermobaric conditions change. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2025, 239, 104610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S. Seismic Characteristics of Two Deep-Water Drilling Hazards: Shallow-Water Flow Sands and Gas Hydrate; The University of Texas at Dallas: Richardson, TX, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Peng, K.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, J.; Wang, M. Study on the characteristics of coal and gas outburst hazard under the influence of high formation temperature in deep mines. Energy 2023, 268, 126645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Ju, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X. Numerical analysis of coupled thermal-hydro-chemo-mechanical (THCM) behavior to joint production of marine gas hydrate and shallow gas. Energy 2023, 281, 128224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wu, S.; Tong, G.; Wang, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, W. Acoustic Prediction and Risk Evaluation of Shallow Gas in Deep-Water Areas. J. Ocean Univ. China 2022, 21, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Bai, Y.; Yang, G.; Fang, X.; Liu, Y.; Tao, C. Seismic reflection characteristics and controlling factors of shallow gas in the alongshore mud clinoform of the East China Sea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 158, 106570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, G.; Accaino, F.; Civile, D.; Lodolo, E.; Volpi, V.; Romeo, R. Deep and shallow gas occurrence in the NW Sicilian Channel and related features. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2022, 139, 105575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Shen, F.; Chen, T.; Mitri, H.; Ren, T.; Song, D. Study on the seismic damage and dynamic support of roadway surrounding rock based on reconstructive transverse and longitudinal waves. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2023, 9, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kima, Y.; Cheonga, S.; Chuna, J.H.; Cukur, D.; Kim, S.; Kim, K. Identification of shallow gas by seismic data and AVO processing: Example from the southwestern continental shelf of the Ulleung Basin, East Sea, Korea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 117, 104346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Deng, B.; Zhang, J. Shallow gas in the Holocene mud wedge along the inner East China Sea shelf. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 114, 104233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, G. Simulation of Shallow Gas Invasion Process During Deepwater Drilling and Its Control Measures. J. Ocean Univ. China 2022, 21, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Yang, J.; Yin, Q.; Fu, C.; Zhao, Y.H.; Xue, Q. Numerical simulation study on the mechanism of releasing ultra-deep water shallow gas by drilling pilot holes. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 221, 111294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Kong, D.; Li, Z.; Peng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, Y.P.; Zhu, B. Experimental investigation into gas migration mechanism in submarine sandy sediments at pore-scale. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2025, 17, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Yin, Q.; Guo, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z. Field data analysis and risk assessment of shallow gas hazards based on neural networks during industrial deep-water drilling. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 232, 109079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Yu, A.; Zhou, G.; Xie, J.; Zhang, H. CFD simulation of dense particulate reaction system: Approaches, recent advances and applications—ScienceDirect. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2016, 140, 16–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Padding, J.T. A Novel Approach to MP-PIC: Continuum Particle Model for Dense Particle Flows in Fluidized Beds. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 6, 115408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Xia, Y.; Jin, Y.; Chen, M.; Chen, K. Quantitative study in shale gas behaviors using a coupled triple-continuum and discrete fracture model. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 174, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).