1. Introduction

Global energy demand continues to grow rapidly, and the capacity of renewable energy is also expanding rapidly as shown in

Figure 1 (left) [

1]. In particular, wind energy accounted for the second-largest share of renewable electricity generation in 2024, with a rapid growth rate every year as illustrated in

Figure 1 (right). The wind turbine tower is a key structural component that supports the self-weight and operational loads of the entire system, which must be designed to withstand both static and dynamic loading. Buckling and collapse accidents involving wind turbine towers have been reported frequently, and the continuous trend toward larger turbines suggests that structural failures of tower structures may lead to more severe consequences than other types of accidents [

2]. Most towers are currently designed using the allowable stress design method, which applies safety factors to keep stresses below the material yield strength. However, due to the very thin shells of wind turbine towers relative to their height and diameter, structural failure may occur at loads below the yield strength due to buckling and localized stress concentrations. Therefore, to ensure a safer tower design, it is essential to understand the structural behavior of the slender steel cylindrical shell, including buckling and ultimate strength, under the relevant loading conditions.

Wind turbine towers are subjected to typical loading conditions, including self-weight (e.g., the weight of the rotor, nacelle, and tower), load on rotor (e.g., lateral concentrated load from wind acting on the rotor), aerodynamic wind load (e.g., lateral distributed load from wind acting on the tower), and torque (e.g., torsional load at the top of the tower caused by blade rotation). Among these, the lateral concentrated load, particularly under extreme environmental conditions, is considered a primary factor influencing buckling and collapse. Accordingly, several numerical studies have been conducted to develop analytical methods for predicting the ultimate behavior of towers under such loading conditions. Lee et al. [

3] proposed a nonlinear finite element modelling approach that accounts for the ultimate limit state (ULS) under various loading conditions, including concentrated loads acting on the rotor, for an actual tower structure with openings. Santos et al. [

4] evaluated the ultimate strength of a 10 MW steel tower with a door opening and collar stiffeners, considering variations in the initial imperfection ratio.

To ensure the reliability of finite element analysis (FEA) methods, experimental studies have been conducted using scaled steel cylindrical shells representing wind turbine towers. Four representative studies were identified, and the scaled specimen dimensions and test conditions in each study are summarized in

Table 1 to highlight the characteristics of scaled testing. These tests were conducted to examine lateral loading and the combined effects of bending and compression resulting from it.

Although significant progress has been made, experimental and numerical studies addressing the ultimate behavior of cylindrical structures associated with wind turbine towers remain scarce, especially in exploring the global response of complete steel shell subjected to loads applied at higher elevations. In contrast to previous works, this study adopts scaled models with a deliberately slender configuration, achieving a high L/D ratio that more accurately captures the thin-walled characteristics of real wind turbine towers. Moreover, while longer models are often tested in a horizontal orientation for practical reasons, our experiments were conducted with the models erected vertically, faithfully replicating the actual tower condition.

As summarized in

Table 1, previous studies have primarily adopted fully supported boundary conditions. However, in practice, the tower–foundation interface cannot be regarded as an ideal fully clamped joint. Bolts, grout, and contact friction collectively render the connection semi-rigid rather than perfectly fixed. In particular, several previous studies have highlighted friction as a primary load-bearing mechanism between shells in monopile structures and tower connections. Veljkovic et al. [

9] proposed a slip joint using friction connections with long open slotted holes instead of separate flanges and experimentally validated its structural performance. Subsequently, Heistermann et al. [

10] evaluated the influence of execution tolerances on the structural reliability of such slip joints through FEA. Additionally, in the context of offshore wind turbines, frictional slip at the grouted joint connecting the tower and the monopile structure is a critical factor influencing structural reliability [

11]. In this regard, Islam [

12,

13] proposed a pile-in-pile (PIP) slip joint as an alternative to conventional tubular connections and discussed its structural advantages. Considering these studies, understanding the ultimate structural behavior of shells subjected to friction is essential.

Previous studies [

9,

10] investigated frictional behavior between joined structural components, where friction served as the main mechanism transferring loads across the connection interface. In contrast, the present study focuses on the frictional restraint acting at the support (bottom) of a single slender cylindrical shell which governs the global deformation and buckling behavior of the entire structure. This distinction highlights that, while earlier research emphasized interfacial friction between structures, our work experimentally quantifies how boundary friction within a single structural system influences its ultimate and post-buckling responses. By observing the structural behavior as it approaches the ultimate response under frictional resistance, the study provides fundamental insight into friction-induced deformation and strength characteristics, which can further support localized analyses of frictional slip and contact performance in actual tower connections.

Thus, this study experimentally investigated the buckling and ultimate behavior of a slender steel cylindrical shell structure representing a wind turbine tower under lateral concentrated loading at the upper part, highlighting the influence of boundary conditions. The two types of boundary conditions used in the experiments are as follows. The first condition is a fully supported configuration, in which the bottom of the specimen was completely welded to the lower plate. The second condition is a friction-supported configuration, which allows for the investigation of frictional slip effects. By comparing these two cases, the study evaluated both the ultimate response under idealized full fixation and the post-elastic behavior where friction governs the load transfer mechanism.

Based on the experimental results, the structural behavior was numerically analyzed using the finite element (FE) software ANSYS 2025 R1 [

14], leading to the development and validation of a nonlinear FEA technique applicable to actual tower conditions. Additionally, numerical analyses were conducted to investigate the effects of loading type, friction coefficient and contact area, and initial geometric imperfection, providing further insight into the governing factors that influence the global response and ultimate strength of the structure. Through this combined experimental and numerical approach, the study aims to enhance the safety and reliability of wind turbine tower design and provide a foundation for the practical application of nonlinear FEA techniques.

2. Target Structure and Test Scenarios

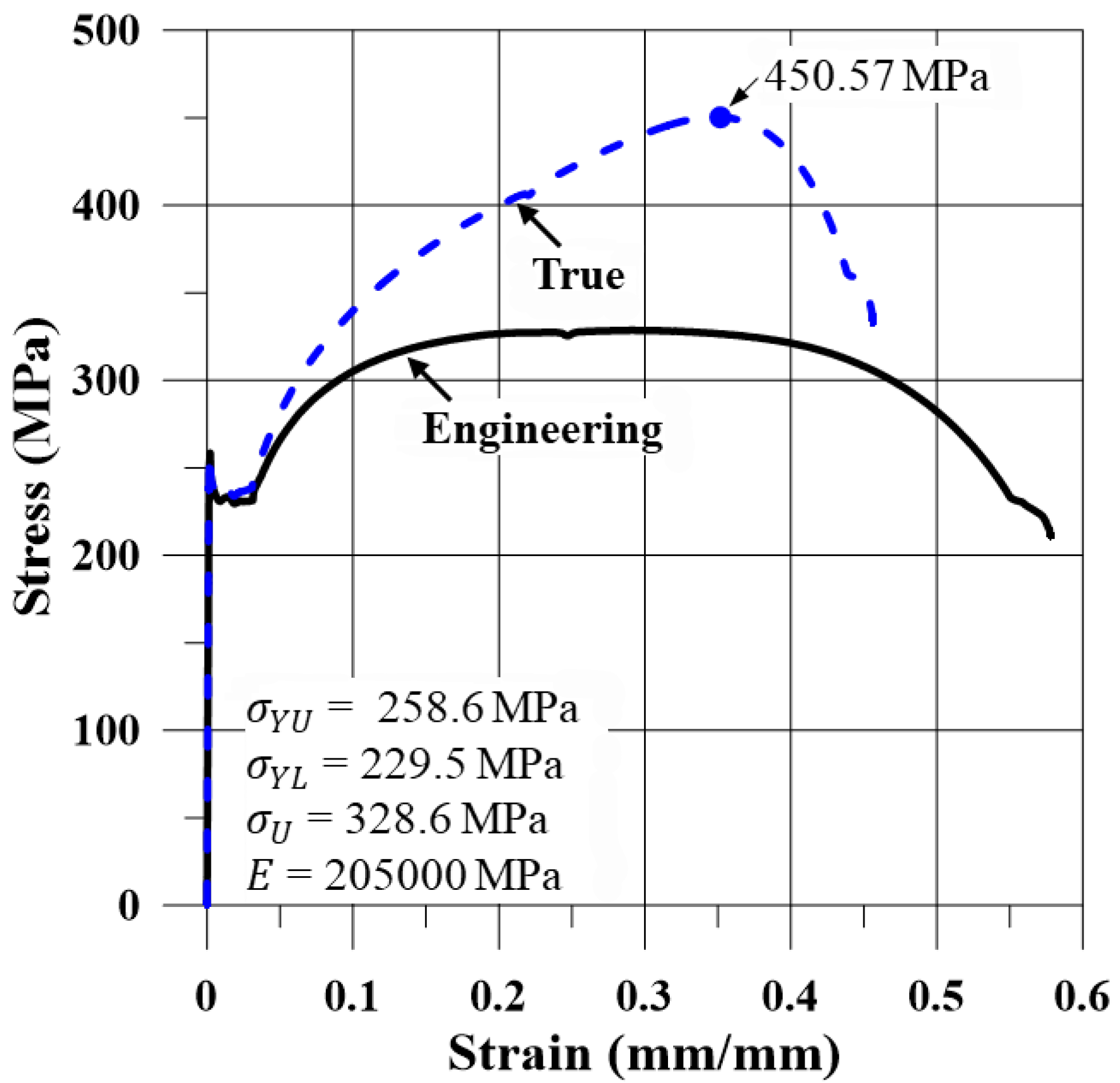

This study used a cylindrical structure which can represent the wind turbine tower as the target structure. Because commercially available cylindrical structures have a much smaller ratio of the diameter to the thickness (D/t) compared to existing wind turbines, the test specimen, shown in

Figure 2, was manufactured by roll forming and welding from a flat plate of carbon steel, the properties of which are listed in

Table 2. To minimize geometric imperfections (e.g., out-of-roundness), the roll forming process was performed multiple times.

The dimensions of the scaled specimens were determined by considering the limitations of the test facility, including the maximum actuator load and stroke capacity. Under these constraints, it was not feasible to simultaneously match the L/D and D/t ratios of full-scale wind turbine towers. Increasing L/D by reducing the diameter would have produced unrealistically small D/t values, while increasing D/t by using thinner plates would have caused welding difficulties, and large initial imperfections such as deflection and residual stress. To balance these competing factors, preliminary FEA was carried out to select an appropriate combination of diameter and thickness capable of reproducing the representative global buckling and post-ultimate behavior within the capacity of the test setup.

Main dimensions and test scenarios are presented in

Table 3. Roundness represents the deviation from a perfect circle and is quantified by the difference between the largest and smallest diameters. As noted in

Section 1, two support conditions were considered, fully and frictionally supported, which were implemented by welding (W) and jigs (J), respectively.

3. Test Setup

Before setting up a test facility, preliminary analyses using analytical and numerical approaches were concisely performed to determine the minimum required load that can demonstrate the post-ultimate behavior of the specimen. Consequently, an MTS actuator system with a maximum load capacity of 250 kN and displacement of 100 mm was selected. While wind loads typically fluctuate, a static loading condition was adopted to examine the structural ultimate behavior and post-buckling characteristics under extreme load scenarios.

Figure 3 illustrates the test setup and its schematic view. The actuator applied a lateral force at the top of the specimen to simulate the wind load transferred to the tower top in the form of a concentrated force. The specimen was tested under two support conditions: fully supported by welding and frictionally supported by jigs, as shown in

Figure 4. In the frictional support case, the jigs were firmly clamped to ensure adequate frictional resistance, thereby allowing the effects of friction and slip to be investigated. Although this setup does not fully reproduce the actual contact condition of a tower base, it enables investigation of how frictional restraint influences deformation and ultimate capacity. Load and displacement were measured using the actuator’s built-in load cell and a Linear Variable Differential Transformer (LVDT). For the fully supported condition, displacement-controlled loading was applied at a rate of 1 mm/min up to the ultimate strength and 5 mm/min thereafter, while for the frictionally supported condition, a loading rate of 3 mm/min was applied.

Considering the 5 mm gage length, the corresponding strain rates were approximately 0.0033/s (fully supported) and 0.01/s (frictionally supported), which fall within the static to quasi-static range. The slower rate for the fully supported case enabled a clearer observation of deformation and post-buckling behavior, whereas the slightly higher rate for the frictionally supported case helped maintain stable loading by reducing slip-induced fluctuations at the contact surface. Under these conditions, strain-rate sensitivity of the steel is negligible, and no noticeable frictional heating occurs, since such thermal effects are known to develop only when the relative sliding velocity exceeds approximately 1 mm/s (60 mm/min). Hence, both rate-dependent and friction-induced thermal effects were ignored in this study.

4. Results of Experimental Test

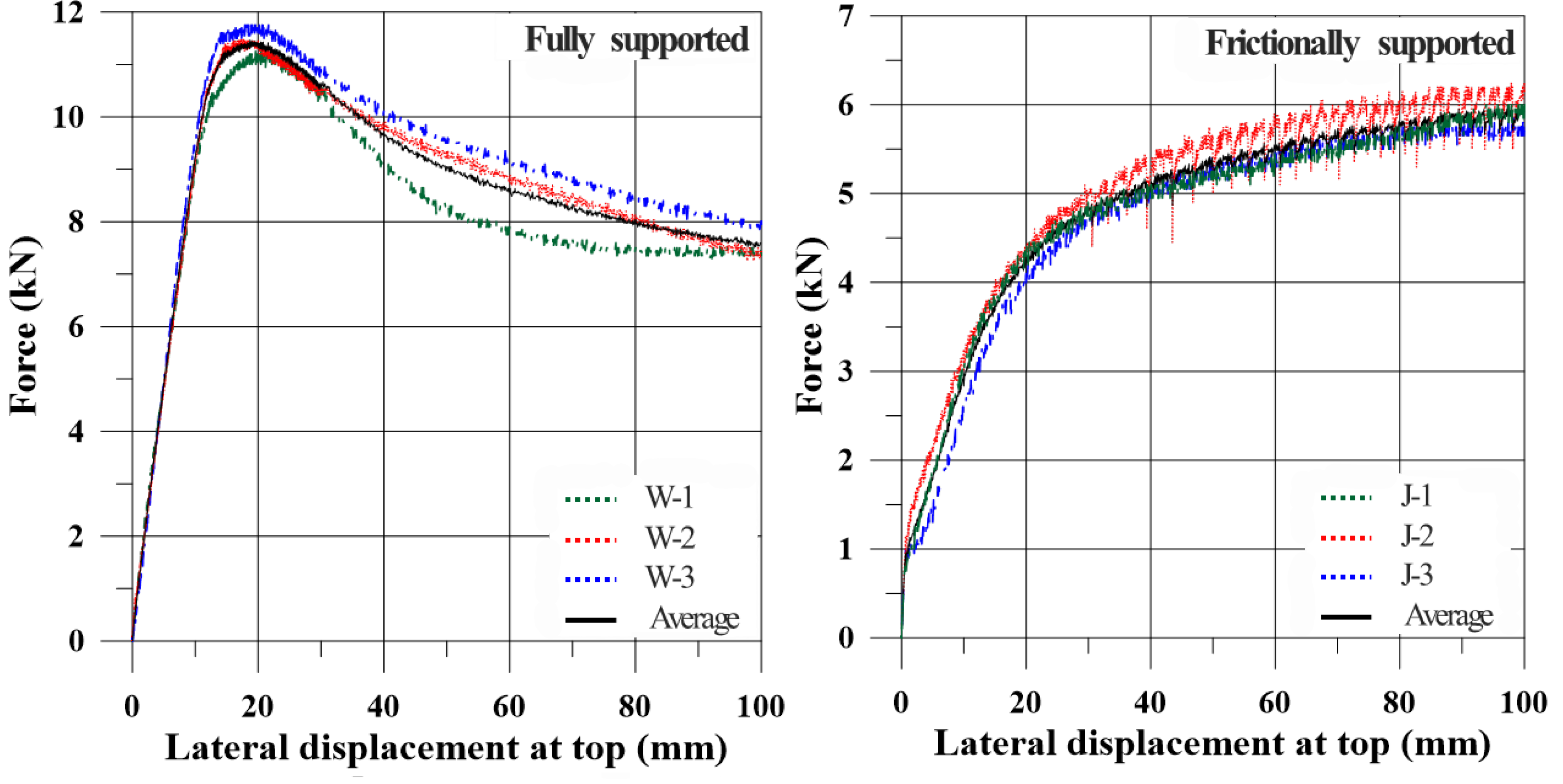

Figure 5 presents the experimentally obtained structural responses of the cylindrical shell specimens under fully and frictionally supported conditions. The data were recorded at a rate of 1 Hz, providing sufficient resolution to capture both the ultimate and post-ultimate behavior. As shown in

Figure 5 (left), the fully supported specimens exhibited a distinct ultimate strength point followed by pronounced post-ultimate behavior. In contrast, the frictionally supported specimens showed a more gradual load–displacement response without a clearly defined ultimate point. Moreover, their peak load was significantly lower than that of the fully supported specimens (

Figure 5 (right)).

The sharper post-ultimate softening observed for specimen W-1 compared with W-2 and W-3 can be explained by slight variations introduced during fabrication. Although all specimens shared the same nominal geometry, they were manufactured from flat steel plates that were roll-formed and welded, which may have produced initial geometric imperfections near the weld seam. Moreover, differences in weld quality and local stiffness could have affected the stress redistribution and post-buckling stiffness.

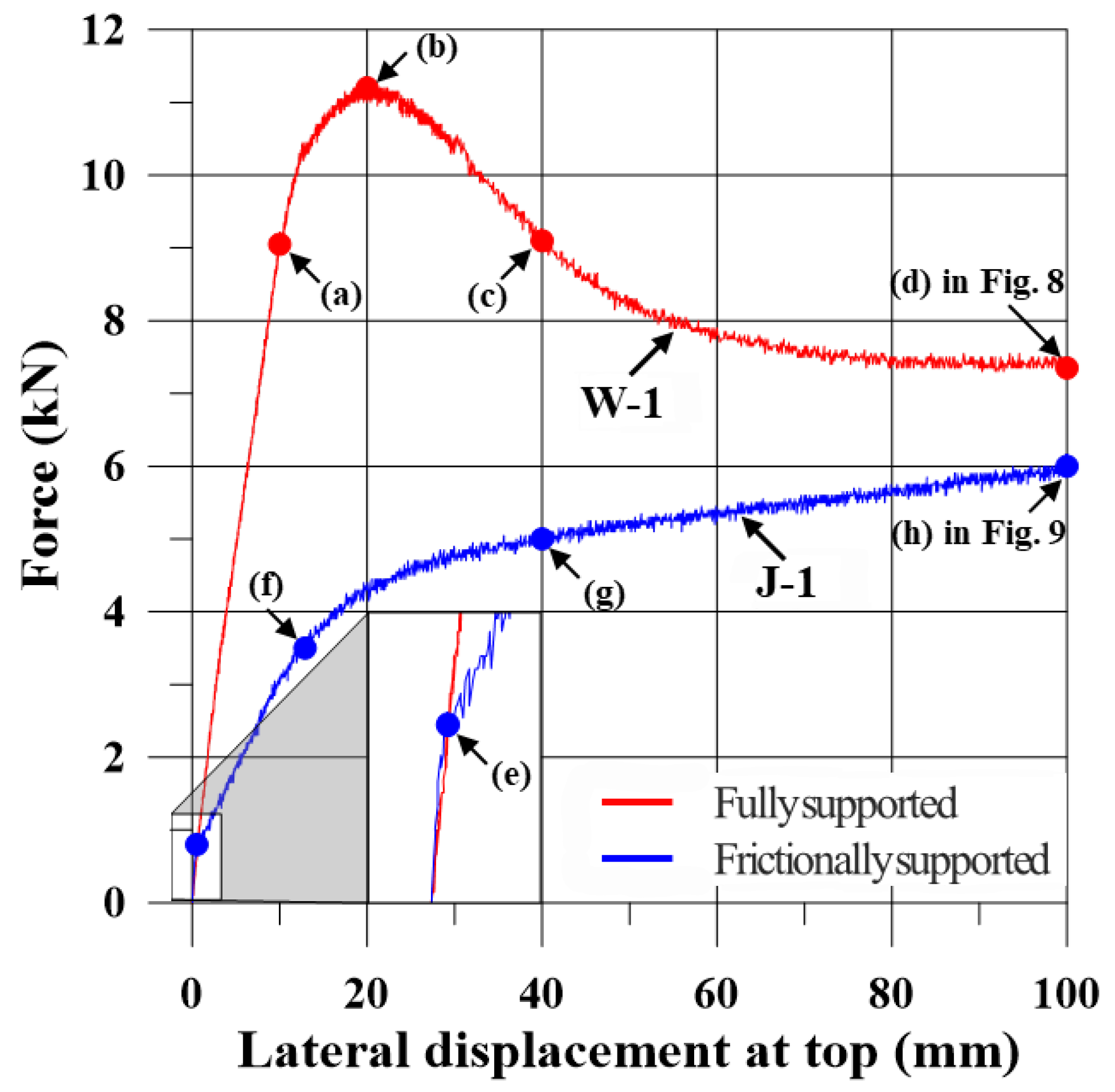

The influence of boundary conditions on the structural response was explicitly observed by comparing the behaviors shown in

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

Figure 6 presents the force–displacement relationships of specimens supported by welding and jig. Additionally,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present global displacements at specific loading conditions indicated in

Figure 6, while the specific local bucking regions are provided in

Figure 9. The states of each marked point were defined as follows.

- -

For the welded specimen (fully supported):

(a) Proportional limit;

(b) Ultimate strength;

(c) Post-ultimate state;

(d) End of the test.

- -

For the jig-supported specimen (frictionally supported):

(e) Onset of sliding (static friction limit exceeded);

(f) Maximum frictional resistance (transition to sliding-dominated behavior);

(g) Nearly constant, low tangent stiffness due to slipping, accompanied by progressive localized buckling near the jig contact area;

(h) The end of the test.

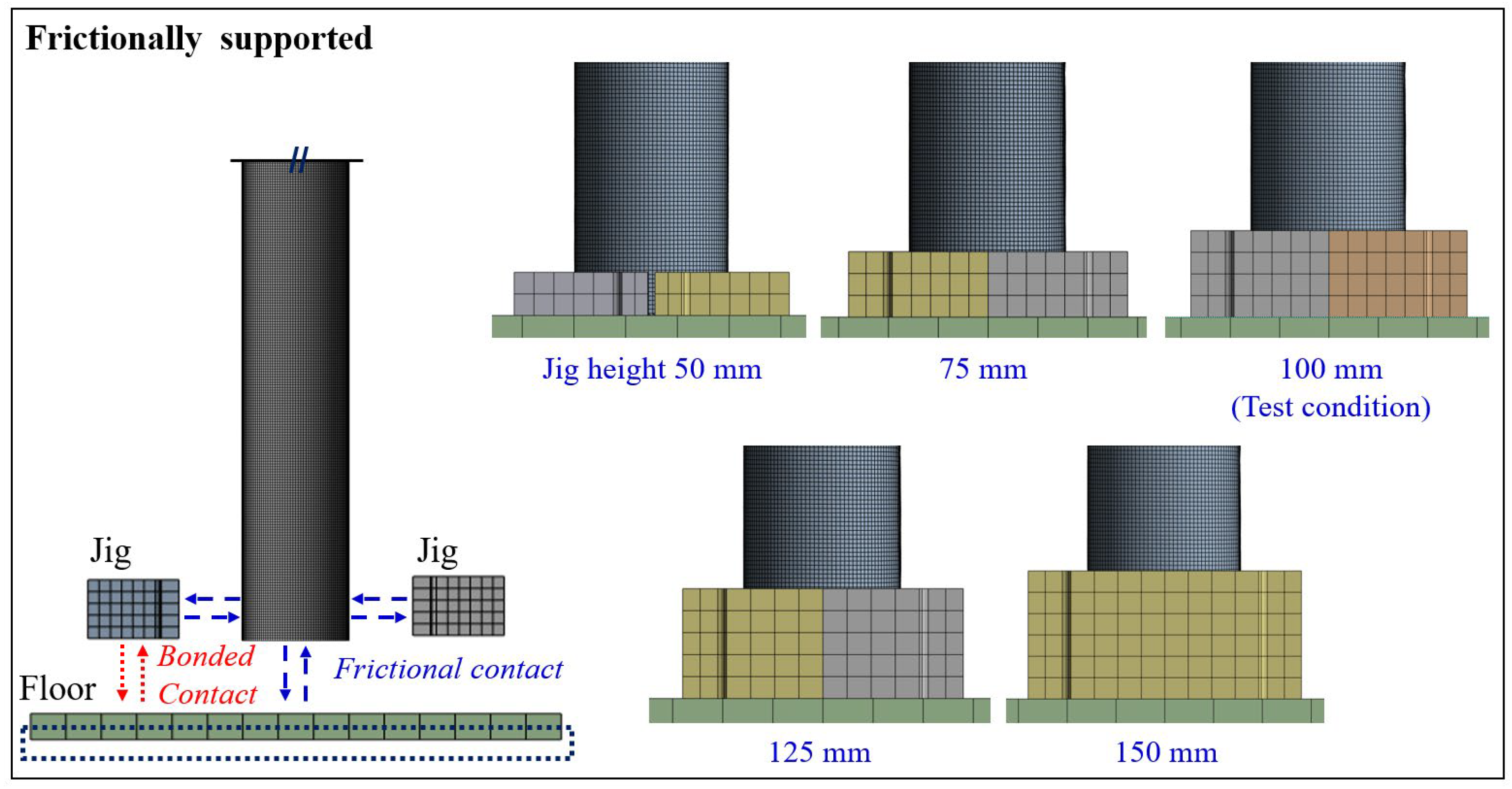

At a displacement of 20 mm, the W-1 specimen reached an ultimate strength of 11.2 kN at point (b) and then experienced a decrease in load. At the same displacement, the J-1 specimen reached 4.4 kN after transitioning to sliding-dominated behavior between points (f) and (g). In the friction-supported model, the structural response can vary depending on the clamping force and the resulting frictional resistance generated by the bolts between the jig and the specimen. In this study, a 100 mm-high jig was installed from the bottom of the specimen to ensure experimental safety and to examine the effect of sufficient frictional resistance. As a result, an approximately 61% difference in strength was observed between the two support conditions, which is attributed to different deformation mechanisms. In the fully supported model, large deformation from buckling that induces nonlinear structural behavior developed. In contrast, in the friction-supported model, gradual plastic deformation occurred at the contact surface with the jig and large deformation caused by buckling was rarely observed. Furthermore, the load increase beyond point (g) may have resulted from the combined influence of changes in frictional contact area due to slip and the vertical compressive force transmitted through the lower contact between the model and the base plate. This implies that the strength of the frictionally supported specimen depends on the effective frictional contact area, since a larger contact area provides greater frictional resistance while a smaller area reduces it.

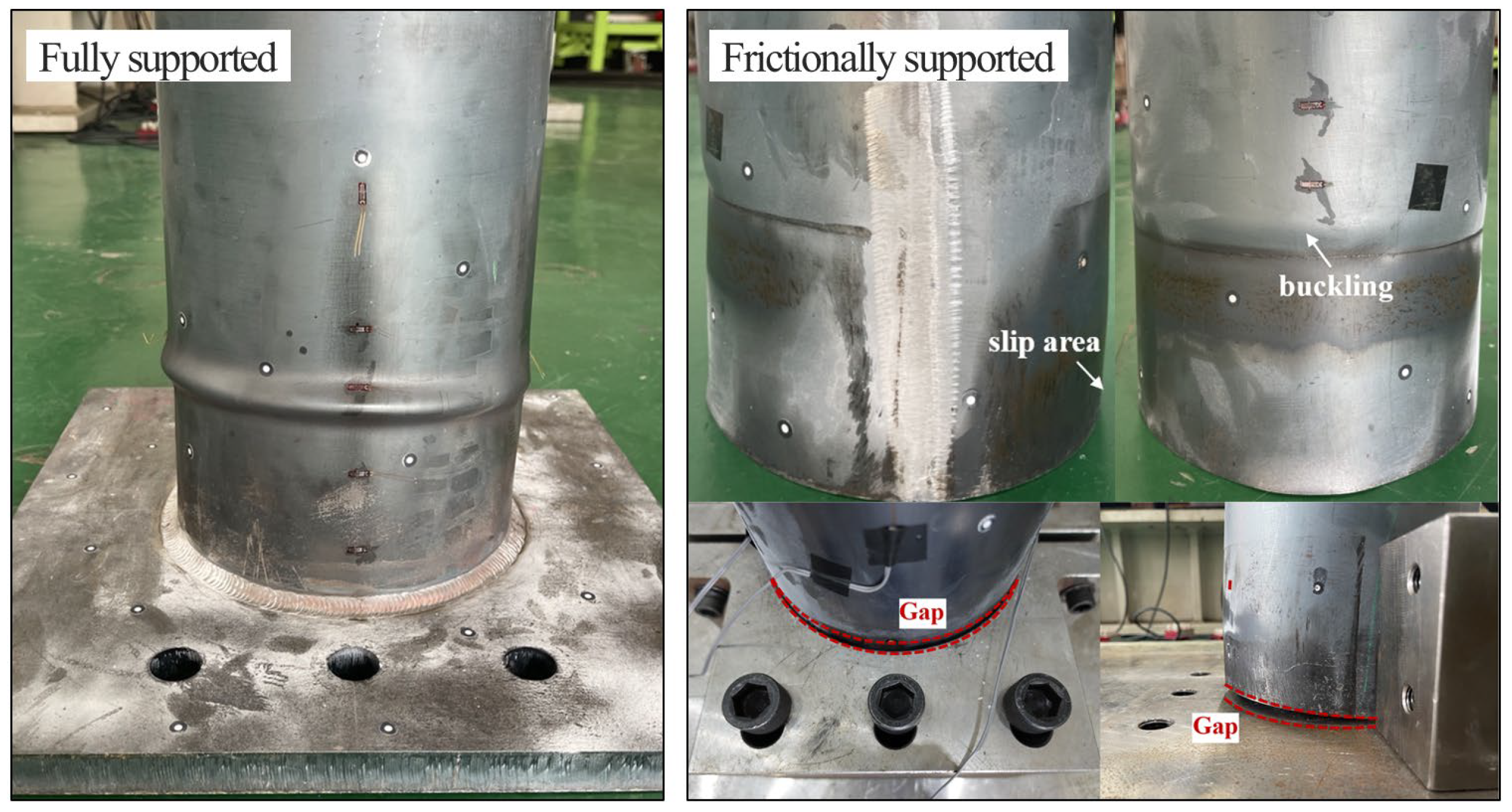

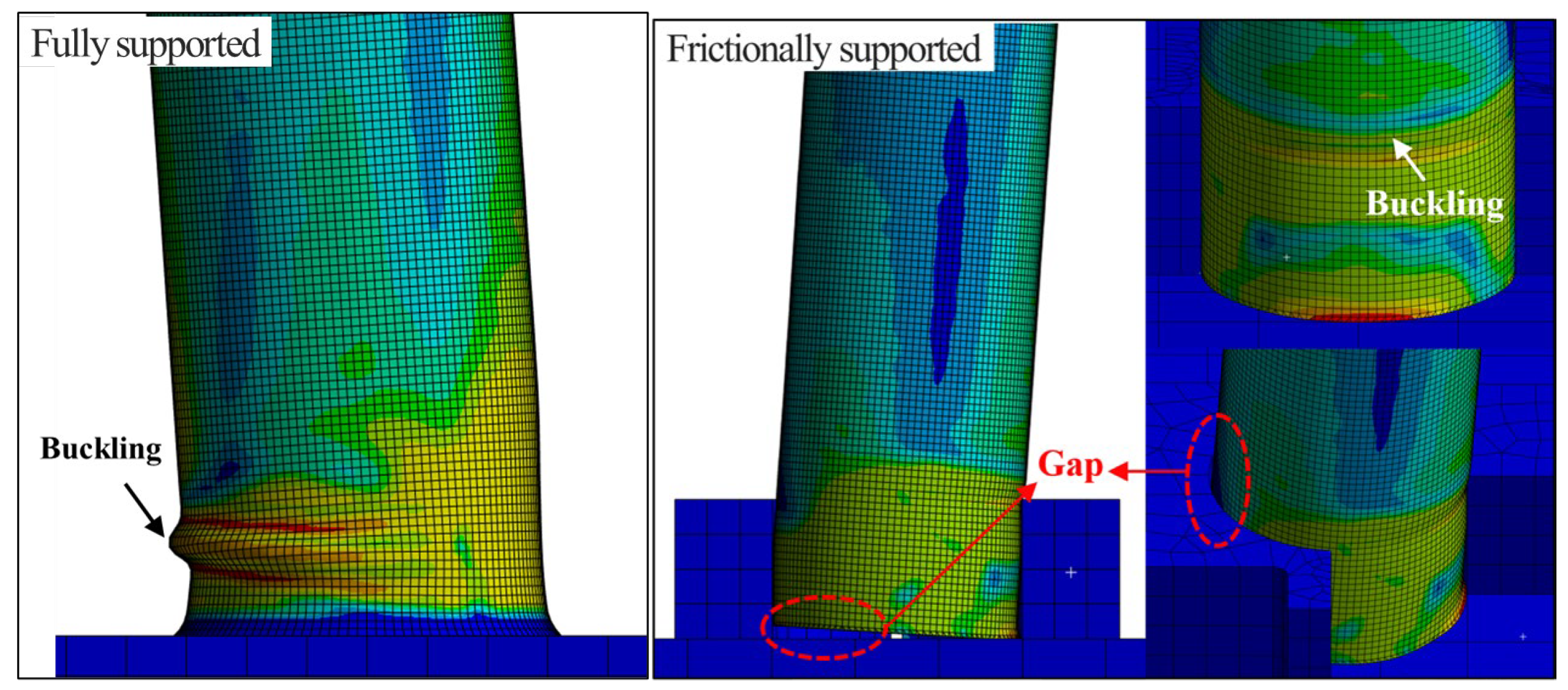

Figure 9 shows the final deformed shapes of the specimens after testing, rather than the instantaneous deformation at the onset of buckling. In the fully supported specimen, pronounced buckling developed near the lower region. In contrast, the frictionally supported specimen exhibited slip marks and progressive localized buckling near the jig contact, accompanied by a visible gap formation at the base.

Table 4 compares the maximum load-carrying capacity and the corresponding top displacement of the specimens. Both support conditions were tested up to the displacement limit of 100 mm imposed by the facility. In the fully supported specimens, a distinct ultimate load was reached followed by load reduction, whereas in the frictionally supported specimens, the maximum load was attained at the displacement limit without a clearly defined ultimate point. The measured maximum loading capacity showed minimal variation, with coefficients of variation (COVs) of 2.17% for the fully supported case and 3.85% for the frictionally supported case, confirming the reliability of the experimental results.

6. Numerical Validation of the Finite Element Model

The comparison aims to evaluate how accurately the developed numerical model can reproduce the overall load–displacement behavior, stiffness degradation, and post-buckling response observed in the experiments.

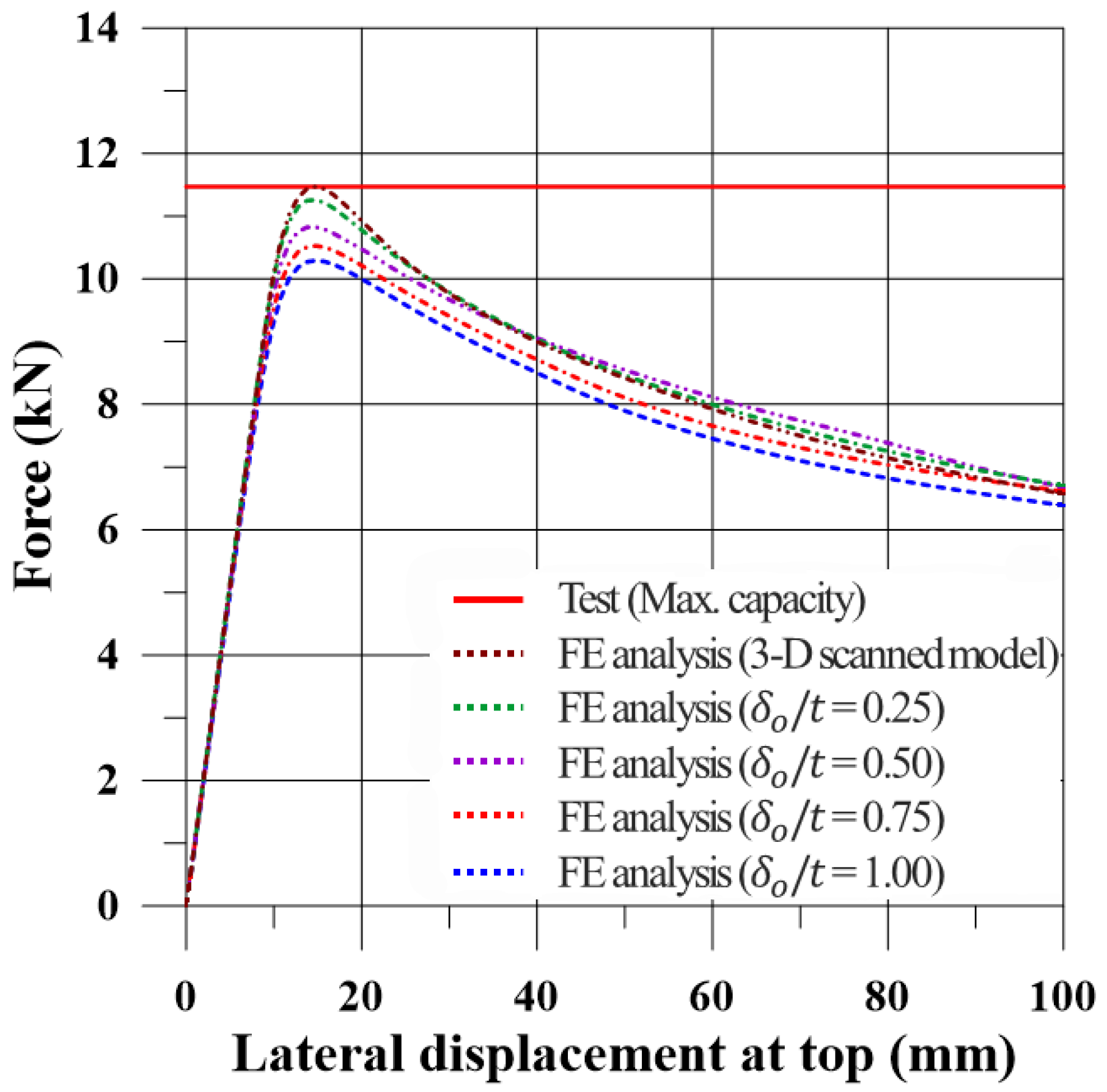

Figure 20 compares the global structural response obtained from numerical analysis and experimental tests. The results indicate that the FE model, considering both fully and frictionally supported conditions, shows good agreement with the experimental results.

For the fully supported model, the FE model slightly underestimated the post-ultimate behavior compared to the experiments. This discrepancy is mainly attributed to the local stiffening effect induced by the welding at the bottom rim. In the experiments, the welded joint and bead formation increased the local thickness and stiffness near the boundary, which was not fully represented in the simplified FE model that employed a rigid constraint at the base without explicitly modeling the weld bead geometry. Nevertheless, stiffness and ultimate strength, as essential characteristics of the ultimate behavior, were accurately captured by the FE model. By contrast, in the frictional contact case, a slight deviation in initial stiffness was observed at the beginning of loading. This discrepancy may be attributed to the bolted connection between the jig and the specimen in the experiment, which could have required a slightly higher load to initiate slipping compared to the idealized numerical model (as indicated at point (e) in

Figure 6).

Figure 21 illustrates the local structural response from the FE analysis. A comparison with the experimental results (shown in

Figure 9) confirms that the developed FE model accurately reproduces the local behavior, particularly around the buckling region and the lower boundary of the structure. Furthermore, the numerical results showed close quantitative agreement with the experimental measurements, demonstrating the reliability of the FE model in capturing the local response characteristics.

7. Conclusions

The main aim of this study was to experimentally investigate the effect of boundary conditions, fully and frictionally supported, on the structural behavior of a cylindrical structure representative of a wind turbine tower under lateral concentrated loads that simulate wind loads on blades. In the numerical part of the study, FE modelling techniques were developed and validated against experimental tests. During this process, the effects of loading type, friction coefficient, contact area, and initial geometric imperfection were examined to achieve deeper understanding of the structural response. The main findings are summarized as follows:

Under the fully supported condition, the ultimate strength of the target structure (L = 1500 mm, D = 180 mm, t = 2 mm) reached an average load of 11.47 kN, after which the load-carrying capacity gradually decreased. In contrast, under the frictionally supported condition, the load at the same displacement was approximately 61% lower due to slip at the contact interface, and the structure showed a continuous increase in resistance without a distinct ultimate load point.

In the fully supported model, the FE framework was systematically validated. The material model employed the true stress–strain curve obtained from the tensile test, and mesh convergence studies confirmed the numerical stability and accuracy of the results. The 3D-scanned geometry showed the closest agreement with the experimental results, corresponding to the behavior of the model with the smallest imperfection amplitude. Moreover, the comparison of different loading types (surface, line, and rigid jig) demonstrated that the simplified line loading accurately reproduced the experimental response.

In the frictional support model, the nonlinear static analysis verified that a friction coefficient of 0.3 accurately represented the dry steel-on-steel contact conditions between the specimen and the jig. Increasing the frictional contact area led to higher structural stiffness and maximum strength, demonstrating that the frictional resistance was nearly proportional to the contact area and should be properly accounted for in the evaluation of frictional behavior.

The developed FE technique showed good agreement with the results of the experimental tests, with coefficients of variation (COVs) of 2.2% for the fully supported case and 3.9% for the frictionally supported case. The technique might be useful to capture the structural behavior of wind turbine tower structures, including the ultimate strength, slipping point, etc., for further research.