Abstract

The Levantine Basin is the first region of the Mediterranean Sea to be impacted by climate warming and the arrival of non-indigenous species (NIS) via the Suez Canal. Although Levantine zooplankton has been studied previously, recent datasets capable of detecting the occurrence of new taxa, or shifts in community composition, especially in the easternmost part of the basin, are lacking. The present study provides updated information on zooplankton composition from Tyre (South Lebanon). In this study, the occurrence of two copepod families (Canuellidae, Longipediidae) and the first regional record of Facetotecta (Y-nauplii) are reported for the first time in the Levantine Basin. Additionally, although six Calanoida species were recorded as new to the Lebanese fauna, none can be attributed to Lessepsian NIS.

Keywords:

biodiversity; Levant sea; Mediterranean basin; plankton; Tyre; Canuella; Longipedia; Facetotecta 1. Introduction

The increasing anthropic pressure [1,2,3,4,5,6], the ongoing climate warming [7,8], the continuous arrival of species from outside the Mediterranean, and biological invasions [9,10,11] make the Mediterranean basin one of the most rapidly changing bioregions worldwide [12,13]. The introduction and invasiveness of non-indigenous species (NIS) are manifested by their establishment and expansion into new ecological niches following their arrival, often at the expense of indigenous species [14]. This process has been intensified since the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 and the damming of the Nile in 1964, making the Levant basin a sentinel zone for newcomer species [9,15] in the frame of the so-called Lessepsian migration [16]. The Levantine Basin is characterized by distinct oceanographic features [17], primarily influenced by its distance from the nutrient-rich Atlantic inflow. It also experiences a negative freshwater balance, with evaporation exceeding the input from rivers and precipitation [18,19]. For these reasons, along with habitat degradation, and fishing pressure, the Levantine Basin is the most sensitive region of the Mediterranean to climate change. Therefore, the increasing sea temperature favors the establishment of new thermophilic species coming from the Red Sea and the Indo-Pacific region [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. The Lebanese coastal waters are characterized by a narrow continental shelf that hosts a variety of marine habitats [28,29,30,31] and a high number of NIS [32,33,34,35,36]. This well-known situation, however, is typical of benthic environments, whereas pelagic communities have not been considered as potentially diverging from this pattern. In fact, the last comprehensive zooplankton lists date back to 2013 (with samples collected in 2007) [37], with most surveys conducted before 2000 [38,39,40,41,42]. No updated datasets have been produced since then, leaving a significant gap in knowledge. Planktonic communities do not always conform to the patterns established from benthic studies. In fact, unlike benthic taxa, some zooplankton groups such as Calanoida show an increase in species richness from west to east across the Mediterranean basin (compare [43] with [44]), as well as a tendency to migrate southwards, contrary to the expected routes imposed by climate warming, even with the transit in the Suez Canal as so-called anti-Lessepsian migrants [16,45,46]. Such atypical behavior, together with the rarity of Lessepsian migrants in planktonic assemblages, highlights the necessity of a dedicated study focused on planktonic communities in the Levantine Basin of the Mediterranean Sea.

Based on material collected within the framework of “Blue Tyre Local Partnership for Sustainable Marine and Coastal Development” (AID 012314/01/6), and in line with previously published results on benthic material [47,48,49], the aim of the present study is to update the zooplankton composition in Lebanese waters, with the focus on the taxon Calanoida (Copepoda), the most important component of the zooplankton across all latitudes in terms of both species richness and abundance [43].

2. Materials and Methods

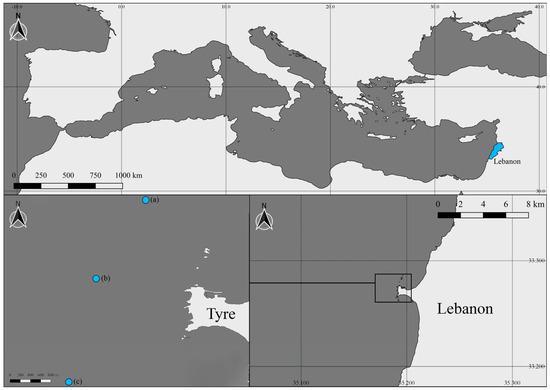

Sample collection was carried out in November 2022, June 2023, and April 2024, within the framework of the Blue Tyre project, at three stations (a, b, c) off the coast of Tyre (south Lebanon) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of the geographic area where sampling has been carried out. (a) 33°17′15.8634″ N, 35°8′24.648″ E, (b) 33°16′25.14″ N, 35°8′15.6114″ E, (c) 33°15′42.2994″ N, 35°8′13.38″ E, sampling stations.

At each station, three vertical tows (each tow representing a replicate) were conducted over a 0–50 m depth interval. The used plankton net was characterized by a 42 cm net mouth diameter and a 200 µm mesh size. The vertical tows were performed by hand without the aid of a winch, taking care of filtering at a speed not lower than 0.5 m·s−1. The filtered volume was calculated by using a flowmeter (digital flowmeter HYDRO-BIOS model 438115, Holtenau-Kiel, Germany). Given the impossibility of using the same instrument throughout the whole duration of the project, environmental parameters such as surface temperature and salinity have been retrieved from the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS) [50].

Each sample was fixed in situ with 80% ethanol and stored in the Blue Tyre Project inventory at the Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences and Technologies (DiSTeBA) of the University of Salento (Lecce, Italy). Samples were sorted under a Zeiss compound microscope, and specimens underwent preliminary morphological identification to the LPT level (lowest possible taxon). Due to their general dominance in species richness and abundance within zooplankton [43], Calanoida (Copepoda) were studied in detail, with species-level identifications made using available identification guides [51,52].

Taxonomic abundances per sample were counted and then normalized to volume (ind.·m−3). For each sampling site and time, mean abundances and standard deviations were calculated to LPT and family level. Statistical analyses included ANOVA carried out on abundance values of 103 zooplankton taxa recorded in 27 samples, and on 5 environmental descriptors (temperature, salinity, Chl-a concentration, photoperiod, and moon phase) related to the three different stations and times of the study. The SIMPER procedure has been used to individuate taxa mainly responsible for similarities inside each time, and each station or dissimilarities between times and stations. Zooplankton diversity was assessed on a subset of the 103 taxa, including only those identified at the species level (59). Species richness (S), Margalef’s index (D), and Pielou’s evenness (J′) were computed using the DIVERSE routine implemented in the software PRIMER-E. To evaluate the effects of sampling time (November 2022, June 2023, April 2024) and station (A, B, C) on community diversity, PERMANOVA analyses were performed on univariate indices using Euclidean distance. Each PERMANOVA included time, station as fixed factors, with 9999 permutations. Abundance data were fourth-root transformed prior to analysis to reduce the influence of dominant taxa, and temporal or spatial differences were considered significant at P(perm) < 0.05 (significance level = 95%). All statistical tests were performed using the software package PRIMER-E v6 [53].

Both the hand towing of the plankton net, the fragmentariness of sampling times, and the impossibility of collecting complete datasets of environmental parameters must be considered as limiting factors for ecological assessments, including seasonality and quantitative comparisons with previous studies [37].

This research complies with restrictions regarding collected sample size and environmental surveys of the collection sites, as well as with local, regional, national, and international rules and regulations on biodiversity access, sustainable use, and benefit-sharing (Convention on Biological Diversity and its Nagoya Protocol, national regulations).

3. Results

The extrapolation of environmental parameters from CMEMS at the three stations at the three sampling times allowed the obtaining of environmental data adjusted in Table 1. At each sampling time, data from the satellite did show differences in values between the stations only for Chl-a concentrations.

Table 1.

Water parameters (temperature, salinity, and Chl-a, from Copernicus satellite data) and season characteristics (photoperiod and moon phase) of sampling sites at time of zooplankton collections. Moon phase is calculated for full moon = 100.

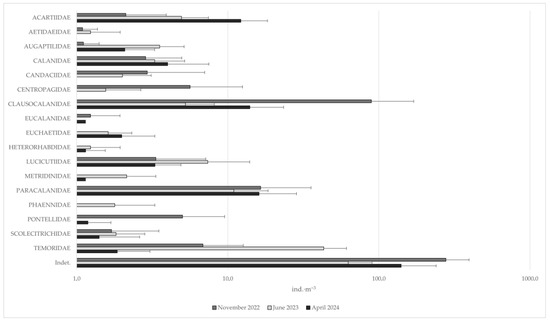

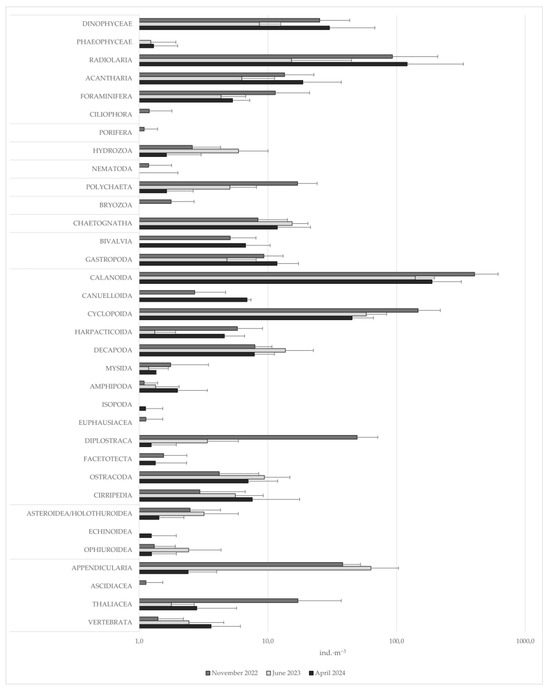

The analysis of 27 zooplankton samples yielded a total of 103 taxa (Table 2). The most represented group was Copepoda (Crustacea), comprising 53 taxa, most of which were identified to the species level, with Calanoida being particularly dominant (41 species) and the most abundant taxon overall, ranging from an average of 14.5 individuals per m−3 (ind.·m−3) at station B (April 2024) to 1751.7 ind.·m−3 at station A (November 2022). Among other Crustacea, the most common were Corycaeidae, Oithonidae, and Oncaeidae, each found in more than 25 of the 27 samples (Figure 2). Taxa with the highest abundances were Clausocalanus furcatus, Temora stylifera (Copepoda, Calanoida), Oithonidae (Copepoda, Cyclopoida), Evadne spp. (Branchiopoda, Onchyopoda). The most abundant “non-Crustacea” taxa were Polychaeta larvae, Chaetognatha, Gastropoda veligers, and Oikopleura sp. (Appendicularia) (Figure 3).

Table 2.

List of all the zooplankton taxa recorded in Lebanon, with their mean abundances and standard deviation at each sampling period. Taxa marked in bold are reported for the first time in Lebanon. Taxa marked with an asterisk (*) are the first record for the entire Levantine Basin.

Figure 2.

Mean abundances of the identified Calanoida families at the three sampling times (each time deriving from three sites and a total of 9 replicates), expressed as ind.·m−3. Abundances are represented on a logarithmic scale (base 10). Error bars represent the standard deviation between all replicates.

Figure 3.

Mean abundances of the identified taxa, other than Calanoida, at the three sampling times (each time deriving from three sites and a total of 9 replicates), expressed as ind.·m−3. Abundances are presented on a logarithmic scale (base 10). Error bars represent the standard deviation between all replicates.

Among the rare or occasional occurrences, Alectona sp. (Porifera), Canuella sp. (Canuelloida), and Longipedia sp. (Canuelloida) were collected as larvae and/or juveniles. Finally, the report of Nauplii “Y” (Hansenocaris sp., Facetotecta), although by very few specimens, added an entire subclass of Crustacea to the fauna of the whole Levantine Basin, with a morphology distinct from any previously described Mediterranean species [54].

The detailed analysis of the Calanoida assemblage led to the discovery of six species new to the Lebanese fauna, including Pseudoamallothrix profunda (Brodsky, 1950), which is also new to the entire Mediterranean Sea. The other five species, recently reported only from the Turkish coast (from 1991 onwards), represent additions to Lebanese zooplankton records. In none of the cases can the faunistic novelties be associated with a recent arrival from the Red Sea via the Suez Canal. P. profunda, in detail, was reported, before the present study, only from the southern Atlantic and northern Pacific [52].

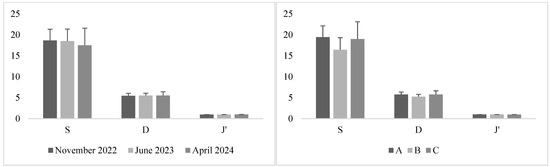

The analysis of the zooplankton diversity indices (S, D, and J′), showed a relatively uniform distribution of species abundances across samples. Mean values of S ranged between 17.5 and 19.4, while Margalef’s index varied from 5.25 to 5.75 across stations and sampling times, with evenness values consistently high between 0.98 and 0.99 (Figure 4). PERMANOVA analyses revealed no significant differences in S or D among sampling times or stations (p > 0.05). In contrast, Pielou’s evenness (J′) showed a highly significant temporal effect (Pseudo-F(2,16) = 11.83, p = 0.001), with the highest evenness recorded in April 2024 (0.992 ± 0.005). No spatial or interaction effects were detected for any diversity index. These findings suggest that, while overall species richness and diversity remained stable across the study area, zooplankton communities exhibited greater evenness in April 2024, possibly reflecting a more balanced distribution among taxa during this period.

Figure 4.

Diversity index values (species richness, S; Margalef’s index; D; and Pielou’s evenness, J′) across sampling times (November 2022, June 2023, and April 2024; (left)) and stations (A, B, and C; (right)). Error bars represent standard deviations.

3.1. Hansenocaris sp.

The genus is currently the only recognized taxon of the subclass Facetotecta (Crustacea), created by Grygier [55] to collocate a series of nauplii, long referred to as “Y” nauplii, with a morphology not corresponding to any known crustacean taxon. Such nauplii have been reported from Japan, the Arctic, the Atlantic, and the Mediterranean Sea, with a total of five species proposed [54,56] (Figure 5a–e).

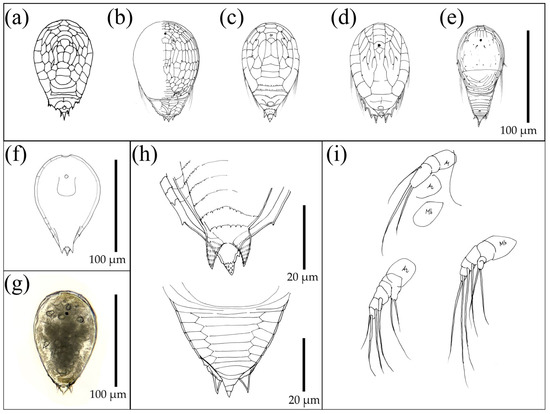

Figure 5.

Nauplius of Facetotecta found in Tyre zooplankton and reference existing species, included for visual comparison with the sampled organisms. (a) Proteolepas sp. (from [56]). (b) Hansenocaris leucadea Belmonte, 2005 (from [54]). (c) H. salentina Belmonte, 2005 (from [54]). (d) H. corvinae Belmonte, 2005 (from [54]). (e) H. mediterranea Belmonte, 2005 (from [54]). (f) Drawing of the Facetotecta found in Lebanon. (g) Microscope photography of the Facetotecta found in Lebanon. (h) Drawing details of ventral (up) and dorsal (down) terminal spines of Facetotecta found in Lebanon. (i) Drawing details of appendices A1, A2, and Mb (antennulae, antennae, and mandibles, respectively) of Facetotecta found in Lebanon.

Adults of Facetotecta, after more than 100 years of scientific research, are still unknown and probably extremely modified endoparasites in some marine organisms [57]. Even under laboratory conditions, Facetotecta nauplii only produced a successive larval stage (a “cypris”) that never underwent the final metamorphosis to the adult stage [58,59,60]. By administering crustacean growth hormone to y-cypris at Okinawa, Glenner et al. [61] induced them to molt into a minute, sluglike “ypsilon” stage, which they interpreted as a juvenile, very likely a parasite, but in any case, not the adult. All described Y nauplii were assigned to the genus Hansenocaris, though it is evident that morphological differences at the larval stage are probably enough to justify differences above the species level. The Hansenocaris nauplii found in the Tyre plankton (Figure 5f–i) shared the general shape with Hansenocaris salentina Belmonte, 2005 (Figure 5c), but with some marked differences, including more pronounced cuticle partitioning in the posterior part of the body, and the absence (or inconspicuous presence) of the rounded cuticular area in the middle of the dorsal part of the rear body. These differences probably justify the recognition of a new species. However, the low abundance of specimens prevented a full diagnostic examination and a formal species description, which will be undertaken in the future.

3.2. Canuella sp.

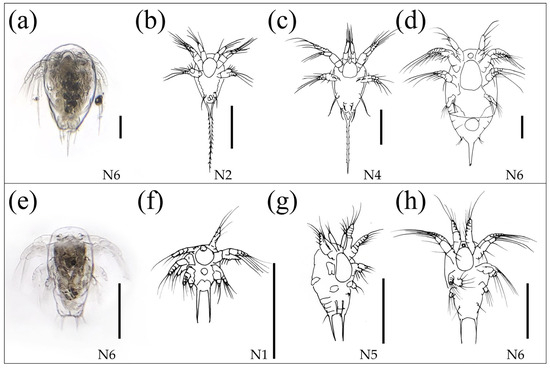

The nauplii were recognizable by their short antennulae, typical of Canuelloida, and by two prominent, semi parallel spines at the extremity of the abdomen, characteristic of family Canuellidae. This family contains several genera, and Canuella species were reported already by Por [62] from the benthos of the Israeli coast, even from Haifa, a site very close to Tyre. However, that report of Canuellidae did not include nauplii, which are typical and well recognizable [63] (Figure 5a–d). In fact, nauplii are common in the plankton of coastal and brackish environments, whereas adults are benthic and rarely encountered in plankton samples.

3.3. Longipedia sp.

The nauplii are characterized by short antennulae, typical of Canuelloida, and a single prominent, elongated spine at the extremity of the abdomen, characteristic of Longipediidae [63] (Figure 6e–h). The family Longipediidae contains a single genus Longipedia, whose adults are characterized by an extremely long terminal article of the P2 (second thoracic leg) and have been reported by Por [62] in coastal benthos of Israel since 1964. Nauplii, along with the first two copepodite instars, are common in coastal plankton and brackish lakes, whereas adults are benthic and rarely found in plankton samples. Although the genus is widespread in the Mediterranean benthos, it has not previously been reported from Lebanese zooplankton.

Figure 6.

(a) Microscope photography of one of the Longipedia nauplii found in Lebanon. (b–d) Drawings of various stages of Longipedia nauplii found in Lebanon. (e) Microscope photography of one of the Canuella nauplii found in Lebanon. (f–h) Drawings of various stages of Canuella nauplii found in Lebanon. All the scale bars measure 100 μm.

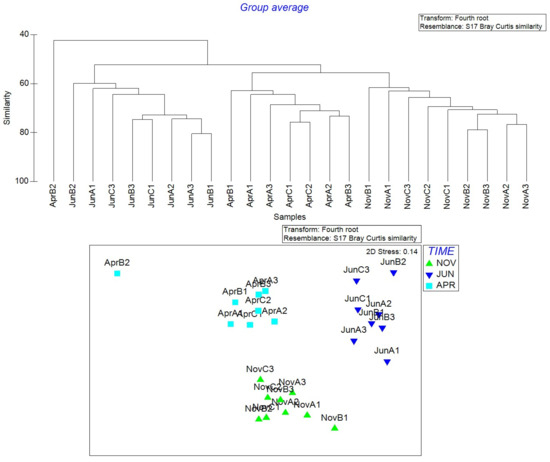

As regards the statistical treatment of data, two Bray–Curtis [64] similarity matrices were obtained to realize a cluster plot of samples (and the relative MDS plot) either for zooplankton or for environmental data (only clusters of samples are reported, Figure 7). In both the plots it is evident that the samples cluster mainly according to the time, than to the space.

Figure 7.

(Up), the cluster graph of samples. All the samples, except AprilB2, of the same time (November 2022, June 2023, April 2024) cluster together at the minimum similarity level of 60%. (Below), the MDS plot representation.

The SIMPER procedure (PRIMER package) allowed us to establish the taxa mainly responsible for similarities inside data groups from different times and stations, and dissimilarities between times and stations in paired comparisons (Table 3). Calanoida indet. (nauplii and juveniles) were always the most important taxon, in terms of abundance (ind. m−3) and consequently the taxon mainly responsible for similarities. The statistical treatment also allowed us to establish the taxa more important for the dissimilarity between times (all the stations) and stations (all the times). Dissimilarity between different times (November 2022, June 2023, April 2024) resulted in more important differences than that between stations (a, b, c) (Table 4). In this case, the taxa responsible for dissimilarities between times were mainly single species (Table 4), and the total dissimilarity was higher for the comparison between distant times (November 2022 vs. April 2024).

Table 3.

The five most important (in terms of abundance and presence) taxa (among 103) in each time (November 2022, June 2023, April 2024), and in each station (A, B, C) in affecting similarities of samples inside times (all the stations) and/or stations (all the times). Av., Average; Ab., abundance; Sim., similarity; SD, standard deviation; Contr., contribution; Cum., cumulative CAL, Calanoida indet.; CORY, Corycaeidae indet.; EVA, Evadne sp.; GAS, Gastropoda veliger; OIKO, Oikopleura; OITH, Oithonidae indet.; ONC, Oncaeidae indet.; RADIO, Radiolaria indet.; TES, Temora stylifera.

Table 4.

The five taxa (among 103) mainly responsible for dissimilarities (in terms of abundance and presence) between times (all the stations). Av., average; Ab., abundance; Diss, dissimilarity; SD, standard deviation; Contr., contribution; Cum., cumulative. ACL, Acartia clausi; BIVA, Bivalvia veliger; CAL, Calanoida indet.; CLF, Ciliofora indet.; EVA, Evadne sp.; OIKO, Oikopleura sp.; POLY, Polychaeta larvae; RADIO, Radiolaria indet.; TES, Temora stylifera.

4. Discussion

Although the sampling plan did not consider a complete annual cycle, and its ecological information could not be considered strong, some differences emerged from previous research in both abundances and taxonomic composition of Lebanese zooplankton. This is particularly evident when compared with the datasets provided by [39], who sampled in a nearby area but not in southern Lebanon, and those of [37,40], who provided most of the available data on Lebanese zooplankton. Lakkis [37,40] described the zooplankton composition of 1969–1972 as being dominated by Copepoda, reaching abundances of up to 3000 ind. m−3, whereas in the present study values never were so high, with a mean abundance of 525.5 ± 210.3 ind. m−3 (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Variations in this size cannot be reliably attributed to ongoing environmental changes, because the possibility of not having collected samples in a “rich” period of the year is real (only one date per year has been considered, and differences in times are probably more affected by interannual variability than by seasonality). The present study is more informative from the point of view of taxa presence. Lakkis published a revised checklist of Lebanese plankton in 2013 [37], also describing seasonal trends in community composition. However, in that study, regarding plankton seasonality in Lebanese waters, only a general overview is provided, without any statistical data on abundance fluctuation. Consequently, comparisons with the data obtained in the present study will be only qualitative. Autumnal plankton was reported showing remarkable abundances of Hydrozoa medusae, Siphonophora, Polychaeta larvae, Appendicularia, Cirripedia larvae, and Radiolaria, together with the presence of Luciferidae larvae (annual peak) and dense macroscopic aggregations of Ctenophora that span over the whole winter period. In the present study, the only autumn date of November 2022 gave all these taxa in the samples; however, only Polychaeta, Appendicularia, Cirripedia, and Radiolaria abundances and the presence of Luciferidae larvae reflected the patterns described by Lakkis [37]. Hydrozoa, Siphonophora, and Cirripedia were found only occasionally in 2022 samples, while Ctenophora were almost absent, with just two individuals at the larval stage recorded in a single sample. During spring, plankton communities are typically characterized by demographic increases, especially in herbivorous and filter-feeding copepods, with higher densities of the predatory Chaetognatha. The data collected in April 2024 reflected these community characteristics. In summer data of [37], the presence of a thermocline between 35 and 75 m coincided with the annual peak of zooplankton biomass, followed by the decline of the phytoplankton. Samples collected in June 2023 did not reflect such a seasonal pattern, showing higher biomass than spring samples but considerably lower than autumn values. Lack of a complete seasonal survey in the present work, however, could justify this difference. In any cases, Lakkis described how June and July typically exhibit very high abundances of Cladocera, particularly Evadne spp., whereas in our samples this taxon showed the lowest density in June. A similar trend was observed for Hydrozoa and Siphonophora, which reached their highest abundances in spring rather than in summer.

These observed deviations from past seasonal patterns could be influenced by ongoing climate change and the warming of Mediterranean waters, which may alter the timing, abundance, and distribution of zooplankton in Lebanese coastal waters. Lakkis [37], however, already highlighted that interannual fluctuations in plankton abundance can exceed twofold increases or decreases relative to the previous year, indicating that our data should be viewed as descriptive snapshots of zooplankton during specific study periods, rather than as definitive ecological comparisons of seasonal dynamics. If the abundance variation in community and single taxa cannot be satisfactorily compared with data of the past, the qualitative composition remains the main result.

Among species new for Lebanese waters, Pseudoamallothrix profunda (Calanoida) was reported before from the South Atlantic and North Pacific [52], in any case far from the entrance area of the Suez Canal, which represents the most important access of faunal novelties in the eastern Mediterranean [9,10]. Also, Canuellidae and Longipediidae were recorded for the first time in the zooplankton of the Levant Basin, as the nauplius stage of unidentified species. Non-adult Copepoda are often left unidentified due to the absence of diagnostic characteristics that are present only in adult stages. However, these two families exhibit morphological features already detectable in nauplii, allowing the first record of Canuelloida families (Canuellidae and Longipediidae) in Lebanese zooplankton, although Canuelloida have already been reported from the benthos of the Levant Basin [62]. Moreover, the present study shows figures to help the identification of naupliar stages of Canuellidae and Longipediidae, that switch to benthic environment when passing to the better studied adult stage. In contrast, Y-Nauplii (Facetotecta), also reported for the first time in the Levent Mediterranean Sea, have unknown adult stages, and only a few authors have provided taxonomic information [60,65,66,67], with only two studies interesting a site of the Mediterranean basin [54,56]. Their morphology, described in the present study, does not correspond to currently known Mediterranean species (see [54]) for a comparison (Figure 4), or to any other species described in the world’s seas [59], and this fact suggests that it could be a species new to science. Future collection (more material) will be resolutive in helping the correct morphological description other than a molecular biology characterization of the possible new taxon, before a definitive addition to the world biodiversity checklist. As in other circumstances, the rarity, and the habit of students to skip the systematics of nauplii in the absence of adults, propose an existence of such a taxon in the area, and not a new arrival. Consequently, for different reasons (species already present in other parts of the Mediterranean, species not present in the Red Sea or the Indian Ocean, and taxa here recognized from the nauplius stage), the faunal novelties here communicated for the Lebanese zooplankton, should not be attributed to the Lessepsian invasion, which is the main responsible for faunal new arrivals in the Levantine Basin of the Mediterranean.

5. Conclusions

The study of zooplankton collected at the marine coast off Tyre (South Lebanon) between 2022 and 2024 has been an occasion to update the knowledge on zooplankton composition in a Mediterranean sector particularly subject to habitat alteration due to climate change, and to biological invasion from the Suez Canal. The analysis of zooplankton composition allowed the addition of six Calanoida species new to the Lebanese zooplankton, including one species new to the entire Mediterranean basin. In addition, two new Copepoda families (Canuellidae, and Longipediidae) and a new subclass of Crustacea (Facetotecta) were also reported for the first time in the zooplankton, as nauplii. None of these faunal novelties appear to certainly derive from Lessepsian invasion (sensu Por [16]). Future studies will take into consideration this particular aspect of Copepoda biogeographic distribution, which, as with other distributional patterns, does not seem to be influenced by the general trends affecting the non-planktonic fauna [43].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.B., S.P., Y.T., L.M.F. and A.T.; methodology, G.B., S.P., L.M.F. and A.T.; validation, G.B.; formal analysis, Y.T., G.B. and D.A.; investigation, Y.T., L.M.F., A.T., R.T. and M.B.; resources, S.P., G.B. and M.B.; data curation, Y.T., G.B. and M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.T. and G.B.; writing—review and editing, L.M.F., A.T., M.A., R.T., M.B., S.P. and D.A.; visualization, Y.T. and G.B.; supervision, G.B. and S.P.; project administration, G.B. and S.P.; funding acquisition, S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the Blue Tyre project. Local Partnership for Sustainable Marine and Coastal Development (AID 012314/01/6), developed by the Municipality of Tricase (Italy) and the Municipality of Tyre (Lebanon), funded by the Italian Agency for Development Cooperation (Promotion of Territorial Partnerships and implementation of the 2030 Agenda) and in part by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.4—Call for tender No. 3138 of 16 December 2021, rectified by Decree n.3175 of 18 December 2021 of the Italian Ministry of University and Research, funded by the European Union-NextGenerationEU. Project code CN_00000033, Concession Decree No. 1034. Of 14 June 2022, adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and research, CUP D33C22000960007, Project title “National Biodiversity Future Center-NBFC”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all the partners and collaborators of the project Blue Tyre: Municipality of Tricase, Municipality of Tyre, Tyre Coast Nature Reserve (TCNR), Cooperation in World Territories (CTM), Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences and Technologies (Di.S.Te.B.A.)—University of Salento, Naturalia (Civic Museum of Natural History of Salento), Magna Grecia Mare Association, Tyros Lag, Lebanon Diving Center.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Mouillot, D.; Albouy, C.; Guilhaumon, F.; Ben Rais Lasram, F.; Coll, M.; Devictor, V.; Meynard, C.N.; Pauly, D.; Tomasini, J.A.; Troussellie, M.; et al. Protected and threatened components of fish biodiversity in the Mediterranean Sea. Curr. Biol. 2021, 21, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, M.; Piroddi, C.; Steenbeek, J.; Kaschner, K.; Ben Rais Lasram, F.; Aguzzi, J.; Ballesteros, E.; Bianchi, C.N.; Corbera, J.; Dailianis, T.; et al. The biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: Estimates, patterns, and threats. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, M.; Piroddi, C.; Albouy, C.; Ben Rais Lasram, F.; Cheung, W.W.L.; Christensen, V.; Karpouzi, V.S.; Guilhaumon, F.; Mouillot, D.; Paleczny, M.; et al. The Mediterranean under siege: Spatial overlap between marine biodiversity, cumulative threats and marine reserves. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 465–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheli, F.; Halpern, B.S.; Walbridge, S.; Ciriaco, S.; Ferretti, F.; Fraschetti, S.; Lewison, R.; Nykjaer, L.; Rosenberg, A.A. Cumulative human impacts on Mediterranean and Black Sea marine ecosystems: Assessing current pressures and opportunities. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langeneck, J.; Putignano, M.; Dimichele, D.; Giangrande, A.; Bilan, M.; Toso, A.; Musco, L. Non-indigenous polychaetes along the Salento Peninsula: New records and first molecular data. Medit. Mar. Sci. 2024, 25, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toso, A.; Solca, M.; Trainito, E.; Stifani, M.; Furfaro, G. Arrivals and departures: Exploring sea slug diversity (Mollusca, Gastropoda) in the Salento Peninsula harbours. Mar. Biodiv. 2025, 55, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejeusne, C.; Chevaldonne, P.; Pergent-Martini, C.; Boudouresque, C.F.; Perez, T. Climate change effects on a miniature ocean: The highly diverse, highly impacted Mediterranean Sea. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, P.G.; Steger, J.; Bošnjak, M.; Dunne, B.; Guifarro, Z.; Turapova, E.; Hua, Q.; Kaufman, D.S.; Rilov, G.; Zuschin, M. Native biodiversity collapse in the eastern Mediterranean. Proc. R. Soc. B 2021, 288, 20202469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenetos, A.; Gofas, S.; Morri, C.; Rosso, A.; Violanti, D.; García Raso, J.E.; Çinar, M.E.; Almogi-Labin, A.; Ates, A.S.; Azzurro, E.; et al. Alien species in the Mediterranean Sea by 2012. A contribution to the application of European Union’s Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD). Part 2. Introduction trends and pathways. Medit. Mar. Sci. 2012, 13, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanevakis, S.; Zenetos, A.; Belchior, C.; Cardoso, A.C. Invading European Seas: Assessing pathways of introduction of marine aliens. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2013, 76, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, P.G.; Schultz, L.; Wessely, J.; Taviani, M.; Dullinger, S.; Danise, S. The dawn of the tropical Atlantic invasion into the Mediterranean Sea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2320687121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, B.S.; Walbridge, S.; Selkoe, K.A.; Kappel, C.V.; Micheli, F.; D’Agrosa, C.; Bruno, J.F.; Casey, K.S.; Ebert, C.; Fox, H.E.; et al. A global map of human impact on marine ecosystems. Science 2008, 319, 948–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, M.J.; Coll, M.; Danovaro, R.; Halpin, P.; Ojaveer, H.; Miloslavich, P. A census of marine biodiversity knowledge, resources and future challenges. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toso, A.; Musco, L. The hidden invasion of the alien seagrass Halophila stipulacea (Forsskål) Ascherson along Southeastern Italy. Medit. Mar. Sci. 2023, 24, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galil, B.S. Taking stock: Inventory of alien species in the Mediterranean Sea. Biol. Invasions 2009, 11, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Por, F.D. Lessepsian Migration: The Influx of the Red Sea Biota into the Mediterranean by Way of the Suez Canal; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1978; Volume 23, p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- El-Geziry, T.M.; Bryden, I.G. The circulation pattern in the Mediterranean Sea: Issues for modeller consideration. J. Oper. Oceanogr. 2010, 3, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bariche, M. Field Identification Guide to the Living Marine Resources of the Eastern and Southern Mediterranean; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012; p. 625. [Google Scholar]

- Sisma-Ventura, G.; Bialik, O.M.; Yam, R.; Herut, B.; Silverman, J. pCO2 variability in the surface waters of the ultra-oligotrophic Levantine Sea: Exploring the air–sea CO2 fluxes in a fast warming region. Mar. Chem. 2017, 196, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitar, G.; Ocaña, O.; Ramos-Esplá, A.A. Contribution of the Red Sea alien species to structuring some benthic biocenosis in the Lebanon coast (Eastern Mediterranean). In CIESM Congress Proceedings, No. 38; CIESM: Villa Girasole, Monaco, 2007; p. 437. [Google Scholar]

- Thessalou-Legaki, M.; Aydogan, Ö.; Bekas, P.; Bilge, G.; Boyaci, Y.Ö.; Brunelli, E.; Circosta, V.; Crocetta, F.; Durucan, F.; Erdem, M.; et al. New Mediterranean biodiversity records (December 2012). Medit. Mar. Sci. 2012, 13, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzomos, T.; Kitsos, M.S.; Koutsoubas, D.; Koukouras, A. Evolution of the entrance rate and of the spatio-temporal distribution of Lessepsian Mollusca in the Mediterranean Sea. J. Biol. Res.-Thessalon. 2012, 17, 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Yokeş, M.B.; Dalyan, C.; Karhan, S.Ű.; Demir, V.; Tural, U.; Kalkan, E. Alien opisthobranchs from Turkish coasts: First record of Plocamopherus tilesii Bergh, 1877 from the Mediterranean. Triton 2012, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zenetos, A. Progress in Mediterranean bioinvasions two years after the Suez Canal enlargement. Acta Adriat. 2017, 58, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galil, B.; Marchini, A.; Occhipinti-Ambrogi, A.; Ojaveer, H. The enlargement of the Suez Canal—Erythraean introductions and management challenges. Manag. Biol. Invasions 2017, 8, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galil, B.S.; Marchini, A.; Occhipinti-Ambrogi, A. East is east and West is west? Management of marine bioinvasions in the Mediterranean Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 201, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilecenoğlu, M.; Yokeş, M.B. New data on the occurrence of two lessepsian marine heterobranchs, Plocamopherus ocellatus (Nudibranchia: Polyceridae) and Lamprohaminoea ovalis (Cephalaspidea: Haminoeidae), from the Aegean Sea. Ann. Ser. Hist. Nat. Sci. Res. Center Slov. Rep. 2022, 32, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, A. Support of space techniques for groundwater exploration in Lebanon. J. Water Resour. Prot. 2010, 2, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhouk, S.N.; Itani, M.; Al-Zein, M. Biodiversity in Lebanon. In Global Biodiversity; Pullaiah, T., Ed.; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 259–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badreddine, A.; Milazzo, M.; Abboud-Abi Saab, M.; Bitar, G.; Mangialajo, L. Threatened biogenic formations of the Mediterranean: Current status and assessment of the vermetid reefs along the Lebanese coastline (Levant basin). Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 169, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bariche, M.; Sayar, N.; Limam, A.; SPA/RAC–UN Environment/MAP. Ecological Characterization of the Coastal and Marine Habitats in Tyre, Lebanon; SPA/RAC, IMAP-MPA Project: Tunis, Tunisia, 2021; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Bitar, G.; Zibrowius, H. Scleractinian corals from Lebanon, Eastern Mediterranean, including a non-lessepsian invading species (Cnidaria: Scleractinia). Sci. Mar. 1997, 61, 227–231. [Google Scholar]

- Zibrowius, H.; Bitar, G. Invertébrés marins exotiques sur la côte du Liban. Leban. Sci. J. 2003, 4, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Harmelin-Vivien, M.L.; Bitar, G.; Harmelin, J.G.; Monestiez, P. The littoral fish community of the Lebanese rocky coast (eastern Mediterranean Sea) with emphasis on Red Sea immigrants. Biol. Invasions 2005, 7, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morri, C.; Puce, S.; Bianchi, C.N.; Bitar, G.; Zibrowius, H.; Bavestrello, G. Hydroids (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa) from the Levant Sea (mainly Lebanon), with emphasis on alien species. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2009, 89, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bariche, M.; Fricke, R. The marine ichthyofauna of Lebanon: An annotated checklist, history, biogeography, and conservation status. Zootaxa 2020, 4775, 001–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakkis, S. Le zooplancton des Eaux Marines Libanaises (Méditerranée Orientale): Biodiversité, Biologie, Biogéographie; ARACNE Éditrice: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- El-Maghraby, A.M. The seasonal variations in length of some marine planktonic copepods from the eastern Mediterranean at Alexandria. Crustaceana 1965, 8, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimor, B.; Bedurgo, V. Cruise to the Eastern Mediterranean. Cyprus 03. plankton reports. Sea Fish. Res. St. Halif. Bull. 1967, 45, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lakkis, S. Considerations on the distribution of pelagic copepods in the Eastern Mediterranean off the coast of Lebanon. Acta Adriat. 1976, 18, 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalev, A.V.; Kideys, A.E.; Pavlova, E.V.; Shmeleva, A.A.; Skryabin, V.A.; Ostrovskaya, N.A.; Uysal, Z. Composition and abundance of zooplankton of the eastern Mediterranean Sea. In The Eastern Mediterranean as a Laboratory Basin for the Assessment of Contrasting Ecosystems; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zakaria, H.Y. The zooplankton community in Egyptian Mediterranean waters: A review. Acta Adriat. 2006, 47, 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez de Puelles, M.L.; Gras, D.; Hernandez-Leon, S. Annual cycle of zooplankton biomass, abundance and species composition in the neritic area of the Balearic Sea, Western Mediterranean. Mar. Ecol. 2003, 24, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siokou-Frangou, I.; Christaki, U.; Mazzocchi, M.G.; Montresor, M.; Ribera d’Alcalà, M.; Vaquè, D.; Zingone, A. Plankton in the open Mediterranean Sea: A review. Biogeosciences 2010, 7, 1543–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmonte, G. Mediterranean Sea biodiversity. In Elements of Pelagos Biology; Belmonte, G., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 97–146. [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte, G. Acartiidae Sars, G.O., 1903. ICES Identif. Leafl. Plankton 2021, 194, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furfaro, G.; Fumarola, L.M.; Toso, A.; Toso, Y.; Trainito, E.; Bariche, M.; Piraino, S. A Mediterranean melting pot: Native and non-indigenous sea slugs (Gastropoda, Heterobranchia) from Lebanese waters. BioInvasions Rec. 2024, 14, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toso, A.; Putignano, M.; Fumarola, L.; Bariche, M.; Giangrande, A.; Musco, L.; Piraino, S.; Langeneck, J. A revised inventory of Annelida in the Lebanese coastal waters with ten new aliens for the Mediterranean Sea. Medit. Mar. Sci. 2024, 25, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcour, N.; Garzia, M.; Oliver, P.G.; Berrilli, E.; Toso, A.; Bariche, M.; Albano, P.G.; Mariottini, P.; Salvi, D. High genetic diversity and lack of structure underlie the invasion history of the non-indigenous oyster Dendostrea cf. crenulifera (Mollusca, Ostreida, Ostreidae) spreading in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. NeoBiota 2025, 6, e156780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMEMS 2020–2025. Marine Data Store. Available online: https://marine.copernicus.eu/access-data/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Vives, F.; Shmeleva, A.A. Crustacea, Copépodos marinos I. Calanoida. In Fauna Ibérica; Ramos, M.A., Ed.; Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 2007; Volume 29, p. 1152. [Google Scholar]

- Razouls, C.; Desreumaux, N.; Kouwenberg, J.; de Bovée, F. Biodiversity of Marine Planktonic Copepods (Morphology, Geographical Distribution and Biological Data). Sorbonne University, CNRS. Available online: http://copepodes.obs-banyuls.fr/en (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Anderson, M.J.; Gorley, R.N.; Clarke, K.R. PERMANOVA+forPRIMER: Guide to Software and Statistical Methods; PRIMER-E: Plymouth, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte, G. Y-Nauplii (Crustacea, Thecostraca, Facetotecta) from coastal waters of the Salento Peninsula (south eastern Italy, Mediterranean Sea) with descriptions of four new species. Mar. Biol. Res. 2005, 1, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grygier, M.J. New records, external and internal anatomy, and systematic position of Hansen’s Y-larvae (Crustacea: Maxillopoda: Facetotecta). Sarsia 1987, 72, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steuer, A. Über eine neue Cirripedienlarve aus dem Golfe von Triest. Arb. Zool. Inst. Univ. Wien Zool. Staz. Triest 1903, 15, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer, N.; Bernot, J.P.; Olesen, J.; Kolbasov, G.A.; Høeg, J.T.; Machida, R.J.; Chan, B.K. Phylogenomics of enigmatic crustacean y-larvae reveals multiple origins of parasitism in barnacles. Curr. Biol. 2025, 35, 3356–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, J. Nauplius “y” Hansen: Its distribution and relationship with a new cypris larva. Vidensk. Medd. Dan. Naturhist. Foren. 1965, 128, 245–258. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbasov, G.A.; Grygier, M.J.; Ivanenko, V.N.; Vagelli, A.A. A new species of the y-larva genus Hansenocaris Itô, 1985 (Crustacea: Thecostraca: Facetotecta) from Indonesia, with a review of y-cyprids and a key to all their described species. Raffles Bull. Zool. 2007, 55, 343–353. [Google Scholar]

- Grygier, M.J.; Høeg, J.T.; Dreyer, N.; Olesen, J. A new internal structure of nauplius larvae: A “ghostly” support sling for cypris y left within the exuviae of nauplius y after metamorphosis (Crustacea: Thecostraca: Facetotecta). J. Morphol. 2019, 280, 1222–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenner, H.; Høeg, J.T.; Grygier, M.J.; Fujita, Y. Induced metamorphosis in crustacean y-larvae: Towards a solution to a 100-year-old riddle. BMC Biol. 2008, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Por, F.D. A study of the Levantine and Pontic Harpacticoida (Crustacea, Copepoda). Zool. Verh. 1964, 64, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Sazhina, L.I. Naupliusi Massovik Vidov Pelagiceskik Copepod Mirovogo Oceana; Naukova Dumka: Kyiv, Ukraine, 1985; p. 240. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Bray, J.R.; Curtis, J.T. An Ordination of the Upland Forest Communities of Southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 1957, 27, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, H.J. Die Cladoceren und Cirripeden der Plankton Expedition. Ergeb. Plankton-Exped. Humbold Stift. 1899, 2, 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, T. Three types of ‘‘nauplius y’’ (Maxillopoda: Facetotecta) from the North Pacific. Publ. Seto Mar. Biol. Lab. 1986, 31, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, H.; Takahashi, K.; Toda, T.; Kikuchi, T. Distribution and seasonal occurrence of nauplius y (Crustacea: Maxillopoda: Facetotecta) in Manazuru Port, Sagami Bay, Central Japan. Taxa 2000, 9, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).