Abstract

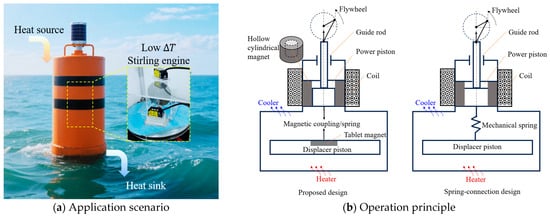

The ocean, as one of the largest thermal energy storage bodies on earth, has great potential as a thermal-electric energy reserve. Application of the relatively fixed-temperature ocean as the heat sink, and using concentrated solar energy as the heat source, one may construct a mobile power station on the ocean’s surface. However, a traditional solar-based heat source requires a large footprint to concentrate the light beam, resulting in bulky parabolic dishes, which are impractical under ocean engineering scenarios. For buoy-sized applications, the small form factor of the energy collector can only achieve limited temperature differential, and its energy quality is deemed to be unusable by traditional spring-loaded free piston Stirling engines. Facing these challenges, a low-temperature differential free piston Stirling engine is presented. The engine features a large displacer piston (ϕ136, 5 mm thick) made of corrugated board, and an aluminum power piston (ϕ10). Permanent magnets embedded in both pistons couple them through magnetic attraction rather than a mechanical spring. This magnetic “spring” delivers an inverse-exponential force–distance relation: weak attraction at large separations minimizes damping, while strong attraction at small separations efficiently transfers kinetic energy from the displacer to the power piston. Engine dynamics are captured by a lumped-parameter model implemented in Simulink, with key magnetic parameters extracted from finite-element analysis. Initial results have shown that the laboratory prototype can operate continuously across heater-to-cooler temperature differences of 58–84 K, sustaining flywheel speeds of 258–324 RPM.

1. Introduction

The ocean accounts for 70% of the earth’s surface area and contains a vast amount of energy, including solar, thermal, wave and tidal energy, etc. These energy sources are completely renewable and continuously available, which are ideal for offshore and onsite power generation, to power ocean monitoring devices such as data buoys. Currently, data buoys are mostly powered by photovoltaics. Since solar panels’ output power may be limited by the real estate of the buoy’s projected surface area, additional energy sources such as the temperature differential energy from the ocean may be of great value to improve the electrical power output capability of the device. Based on basic thermodynamics, it is known that large mediums such as the ocean can be high in terms of internal energy, and the temperature of the water body can be relatively constant over the seasons. The recorded annual average water temperature of the global ocean surfaces is about 290 K, with the highest in the Pacific Ocean up to 302 K, and the lowest in the Arctic Ocean down to 271 K [1]. A water body maintained at a relatively stable temperature can serve as an ideal heat sink against a solar collector; if converted into electricity, it can have a significantly positive impact on the long-term deployment of data buoys.

To utilize the temperature differential between the heat source and sink, the Stirling engine is a promising candidate to convert the thermal into mechanical energy. Stirling engines can be categorized into two major architectures, the kinetic or free-piston configurations. The former uses four-bar linkage to couple the motion between the power and displacer piston and often a flywheel is required for energy storage, while the latter uses the gas dynamics together with the spring and power take-off devices attached to the pistons to achieve oscillations. In theory, Stirling engines can be very high in efficiency, which makes them popular in the renewable energy conversion field. At present, Stirling solar energy conversion devices mostly rely on solar concentrators as heat source, and most of the deployment locations are on land. Today’s commercial/currently-under-research solar Stirling generators are large in size and often operate under 500 K–700 K under nominal conditions [2]. For buoy-scale applications, the limited form factor of a typical buoy cannot accommodate conventional parabolic dishes ranging from 3 m to 17 m in diameter, whereas dishes small enough to fit fail to raise the hot-end temperature to the required level, leading to sub-optimal engine operation [3].

Most state-of-the-art Stirling engine research focuses on improving the engine efficiency, partially overlapping with the goal of low-temperature operation. However, details such as the engine start conditions are rarely discussed. And very few details have been reported on the topic of engine performance under low-temperature excitation. Published work in this field can be categorized as component-level investigations such as structural optimization, heat transfer intensification, or system-level optimization. Firstly, extensive research work has been reported on the improvement of the original Stirling structure. Rahmati et al. performed optimization of Stirling heat engine connecting rod for higher output power [4]. Joseph et al. designed a gamma engine and studied the rotational speed under different temperature differences [5]. Takeuchi et al. studied a modified alpha-type engine for indirect heating sources [6]. Cheng et al. established a four-cylinder double-acting Stirling model with combined maximum shaft power of 103 W and 12 N·m available torque at 1200 K temperature difference [7]. Sun et al. proposed a new type of combined cooling and power design based on resonance tube coupled free piston Stirling engine, which can achieve global effective energy efficiency at 29.4% [8].

Secondly, under the constraint of limited installation space in modern ocean monitoring equipment, it is critical to improve the heat transfer process through heat exchanger and regenerator designs. Regalado-Rodrguez et al. showed that the engine efficiency can be increased by 1.3 to 2.5 times with different heat exchanger chamber designs [9]. Kumaravelu et al. studied the impacts of shapes of cooling fins on heat transfer, and found rectangular fins can be as efficient as 19% in heat dissipation, compared to other geometries [10]. Xin et al. proposed to significantly reduce the size of the cooler by installing a helical structure on the cold end [11]. Zhao et al. established a high-precision Stirling simulation model for better prediction of heat transfer [12]. Al Nimr et al. replaced the heat exchanger of the solar Stirling unit with phase change materials and increased the system efficiency by 22.6% under 700 W/m2 of sunlight [13]. Chen et al. established free piston Stirling simulation models for single-, two-, and three-section heat exchanger performance prediction [14]. Ahadi et al. studied the effects of porosity of the regenerator on the total engine efficiency [15]. Moura et al. showed numerically that increasing regenerator effectiveness improves overall engine efficiency, yet this is accompanied by a reduction in output power [16]. Additionally, there are also studies reported on the investigation of engine auxiliary systems. In the study of regenerator design, Topgül et al. showed that when the power cylinder is connected to the hot volume of the displacer cylinder rather than the cold volume, the maximum torque and power increase by 68.4% and 84.7% [17]. As mentioned earlier, to improve the engine performance, obtaining higher cyclic efficiency and output power are primary goals for the published work.

So far, the low-temperature differential (LTD) Stirling engines that work around the temperature of water boiling points are mostly toys or garage projects, which designs are very distinguishable by the magnetic coupling between the power and displacer piston, and a high displacer-to-power-piston diameter ratio to achieve steady operation [18]. However, most reported work is empirical, without development of dynamic mathematical relationships or the prediction methods for parameterized study [19]. Most importantly, it is interesting to analyze the complex friction and damping effects of the mechanical linkage and compare with the magnetic couplings on the overall engine performance under low temperature differential conditions.

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper presents an LTD engine prototype that uses magnetic attraction, rather than mechanical springs, to constrain the pistons, as shown in Figure 1. The displacer and power pistons carry permanent magnets of opposite polarity, creating an attractive force between them. This magnetic interaction, together with dynamic gas pressure, couples the two pistons. The power piston runs inside an acrylic tube with a clearance fit; a hollow-cylindrical permanent magnet is mounted on its top end, producing a time-varying magnetic field as the piston reciprocates. A coil wound directly around the acrylic tube generates electricity via Faraday’s law of induction. Additionally, the power piston drives a flywheel to ensure smooth oscillation, and the crank length is adjustable for parametric studies. The proposed Stirling engine, occupying a 150 mm × 150 mm footprint and intended for installation in a smart buoy, can in principle operate with a temperature difference of only 80 K.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the FPSE prototype with magnetic constraint.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the dynamic and thermodynamic equations of the proposed Stirling engine are modeled, and the formula of engine motion is established. A lumped parameter engine numerical solver is established in Section 3 using Simulink block diagram to predict engine performance. In Section 4, a prototype engine is assembled in a lab, and the experimental test setup is presented. In the last sections, the simulation prediction and experimental results of the engine are compared, key parameters of the LTD are investigated, and the proposed engine topology is validated.

2. Mathematical Models

2.1. Piston Dynamics

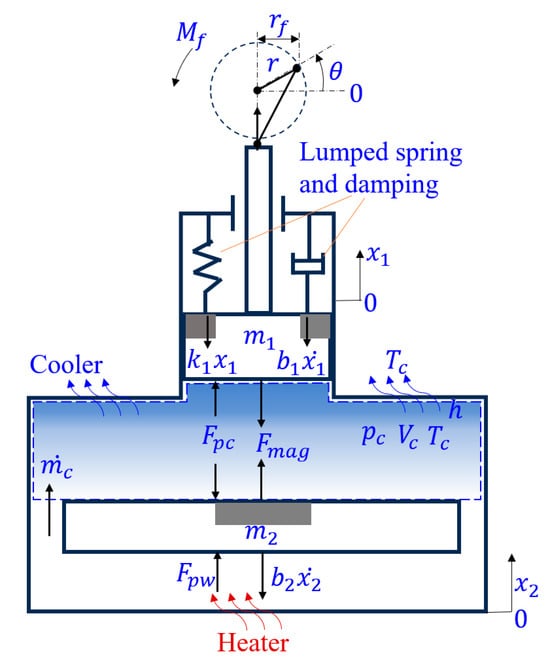

To study the magnetic coupling between the power and displacer pistons, the dynamic equations of the pistons are derived based on Newton’s second law. The free-body diagram is shown in Figure 2. The total external force on the power piston equals the summation of pressure force, the magnetic attraction from the displacer piston, and damping force from combined internal friction and electricity generation.

where is the mass of the power piston, is the power piston displacement, is the lumped damping coefficient including both the electrical generation term , and mechanical dissipation term , is the magnetic force acting on the power piston, is the pressure force acting on the power piston, which equals to the difference between the compression chamber gas pressure and the atmospheric pressure , is the area of the power piston, is the torque at the output shaft of the engine, and is the crank radius projected onto the direction normal to the power-piston axis.

Figure 2.

Free body diagram of the dynamic system. The x1-origin is set at the mid-stroke position between the power piston’s top and bottom dead centers, the x2-origin coincides with the displacer piston’s bottom dead center, and the crank-angle θ-origin is aligned with the positive horizontal axis.

is the tangential force acting on the slider (power piston) along its direction of motion due to torque , and satisfies:

Also, the angular rotation of the flywheel and the displacement of the power piston also satisfy:

Substitute Equations (2) and (3) into Equation (1), which becomes:

where is the effective elastic coefficient of power piston spring. Note that the gravitational term on the right-hand side of the equation is omitted since in vertical orientation, the gravitational effects are absorbed by the pre-stretch of the spring. To mitigate the discontinuities of at 0, π, and 2π, is linearized with respect to , allowing a constant magnitude to be determined by trial and error through numerical simulation.

Upon inspection of Equation (4), it is found that by incorporating the tangential force term into a crank-angle-dependent effective spring constant , the flywheel’s role can be modeled as that of a spring. This analogy is justified because both components cyclically store and release energy over each half-cycle, thereby simplifying the construction of the simulation model.

Similarly, the equation of motion can be found for the displacer.

where is the mass of the displacer, is the pressure force generated on the displacer piston due to pressure differential, is the pressure of the expansion chamber, is the pressure of the compression chamber, and is the cross-section area of the displacer.

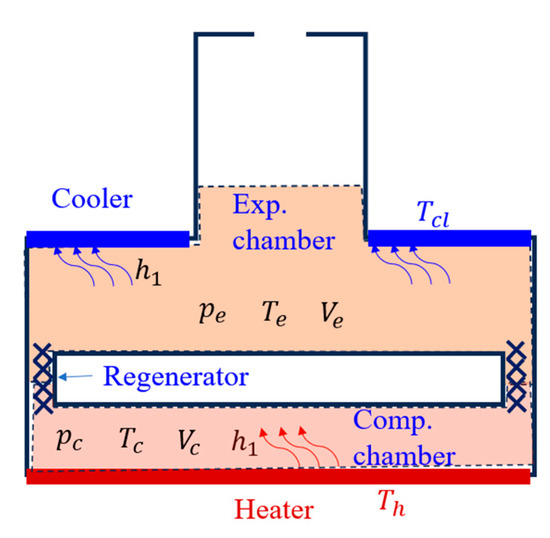

Equations (4) and (5) together define the piston dynamics. To obtain numerical solutions, constitutive relations for the pressure and the magnetic-spring force must be established. Under lumped parameter assumption, the gas trapped beneath the displacer or above can be selected as the control volume, Take the cool end control volume, for instance, shown as the dotted border area in Figure 2, where the principle of conservation of energy can be applied.

whereis the rate of change of internal energy of the control body, is the heat transfer power, is the shaft power, contributed by the boundaries in motion, and is the rate of change of enthalpy of the control volume.

By defining each term in Equation (6), the transport of heat and mass during the engine cycles can be modeled. As the present study concentrates on engine dynamics, the heat-transfer models are relegated to the Appendix A and the authors’ earlier work [20] to keep the main text concise. Then, transient pressure term can be found:

where is the compression chamber temperature, is the cooler temperature, is the heat capacity ratio of the gas, is the heat convection coefficient, is the compression chamber gas volume, which is a function of and . With the constitutive relationships between the pressure and pistons’ displacement determined, the unknowns left to solve Equations (1) and (2) are the and . The derivation for follows the same procedure as in Equations (6) and (7).

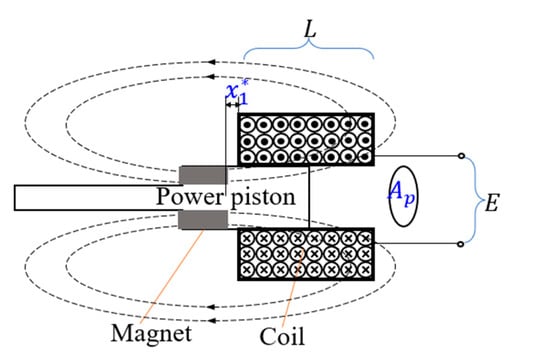

2.2. Electrical Generation

The prototype generates electricity on the power piston cylinder via solenoid coil. According to Faraday’s law of induction, the induced electrical potential is proportional to the negative of the rate of change of magnetic flux , and the number of loops in the coil:

A diagram of the power piston, magnet, and coil is shown in Figure 3. Assuming a linear relationship between the magnet displacement and the magnetic strength, the magnetic flux at the cross section of the coil is modeled as follows:

where is the maximum magnetic strength when the magnet is fully inside the coil; is the length of the coil; and , defined as constant, represents the distance between the nearest end of the magnet and the edge of the coil when the magnet is completely outside the coil.

Figure 3.

Electricity generation model. Note: The dotted lines represent the magnetic field, and the arrows denote the direction of the field.

Then, based on conservation of power, the generated electrical power should equal to a virtual damping force multiplied by the piston velocity:

Therefore, through experimental calibration, can be determined. In this work, open circuit set up is used. Hence, , and .

2.3. Engine Start Conditions

For LTD Stirling engines, one challenge is to understand the conditions for the engine to start. During the engine start phase, it is usually through the manual rotation of the power piston flywheel to gain the required angular momentum to start the engine, which should last long enough until the pressure differential starts to move the displacer. In other words, the engine start problem can be viewed as two initial value problems. Firstly, the provided magnetic pulling work should be capable of aiding the displacer to travel half a stroke, assuming the damping coefficient is a constant. By rearranging Equation (5), the following equation holds:

where is negligible during the engine start, when the pressure difference between the expansion and compression chambers is nearly zero.

Obviously, for the displacer to continuously run for a cycle, the following condition should be satisfied:

Condition 1:

Secondly, the work done by the pressure differential, i.e., , must be greater than the work required to drive the power piston and to overcome the reaction force arising from magnet attraction.

Condition 2:

Obviously, an engine needs to satisfy both conditions 1 and 2 to start successfully. For condition 1, the following pseudo code can be used to perform the evaluation, as shown in Algorithm 1. An algorithm to valuate condition 2 can be programmed in a similar manner.

| Algorithm 1. Function: c1 = Engine_start(t, x2) |

| Inputs: t = {t1, …, tn} is 1 by n time series, x2 = {x21, …, x2n} is 1 by n displacer position voltage signal history Output: c-Boolean, engine start flag 1 Initialize two new variables and , both equals to 0, c1 = FALSE 2 for each t do 3 Simulate simultaneous equations set (Equations (1)–(7)) 4 Get the simulated velocity of the displacer by differentiation 5 6 7 end 8 if 9 c1 = TRUE 10 end |

3. Numerical Study

3.1. Magnetic Constraint/Field Analysis

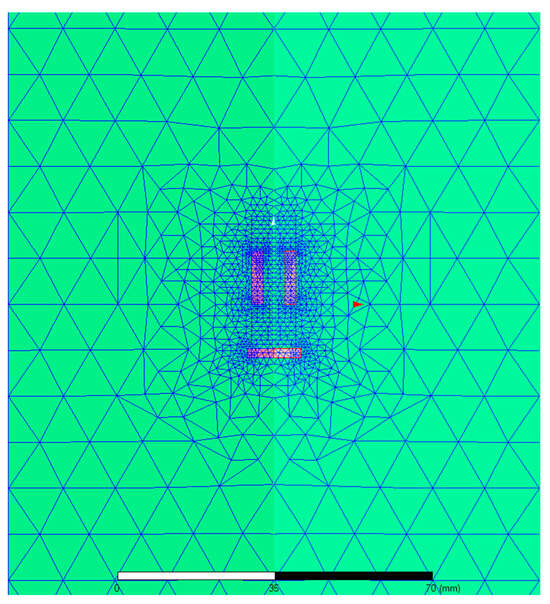

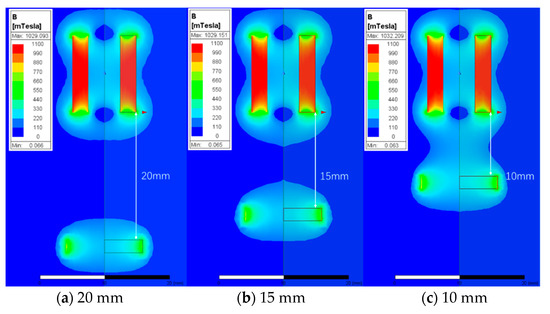

Due to the complexity of magnetic fields, the magnetic force as a function of distance between magnets is analyzed numerically. To study the magnetic attraction force, the two permanent magnets (Neodymium N35) are modeled in the Ansys Electronics Student software (Version 2024), the force is simulated under quasistatic condition, where the impacts of the time derivatives of the distance is ignored. This assumption is valid because the simulation includes no inductors whose dynamics would need to be considered, and, according to Maxwell’s theory, the total field produced by two permanent magnets is simply the superposition of the individual fields. In the simulation, a hollow cylindrical magnet and a circular tablet magnet are set to attract and follow the same axis, as shown in Figure 4. Axial symmetric 2D simulating of the two magnets spaced between 0 and 20 mm are carried out. The key parameters are listed in Table 1. Note that in the Ansys software, “adaptive setup” mode was selected in the configuration. Therefore, the system ensures convergence by calculating the total energy, percentage of error, etc. of the model, until the values converged.

Figure 4.

Generated mesh elements. Note: the top red blocks represent the cylindrical magnet on the power piston, the bottom one represents the tablet magnet on the displacer.

Table 1.

Magnet spring force simulation parameters.

3.2. Numerical Solution of the Combined Dynamics

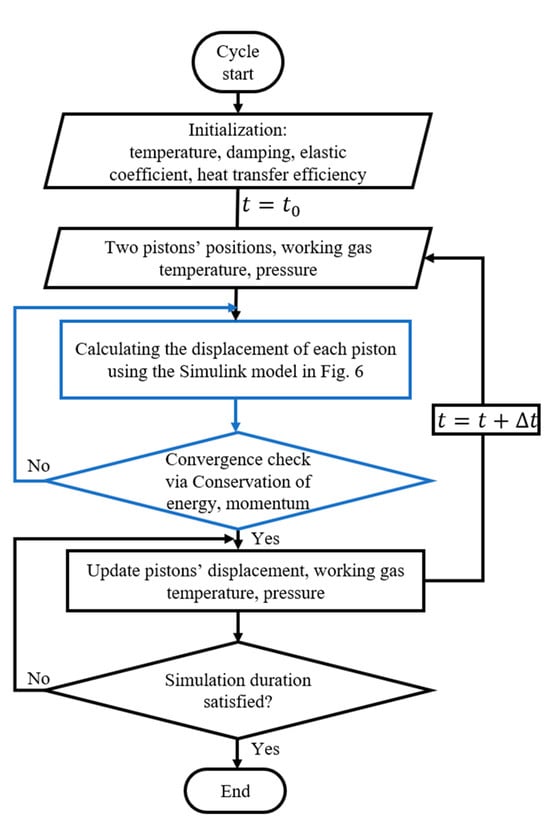

The dynamic models of the proposed Stirling engine need to be solved simultaneously. To do so, a block diagram was constructed in MATLAB/Simulink (Version 2024b), to study the influence of various parameters on the prototype. During the simulation, at each time step, the magnet dynamics, gas pressure, and heat transfer are solved simultaneously and iteratively, until all the variables are converged. The simulation procedures are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Flowchart of the combined transient simulation.

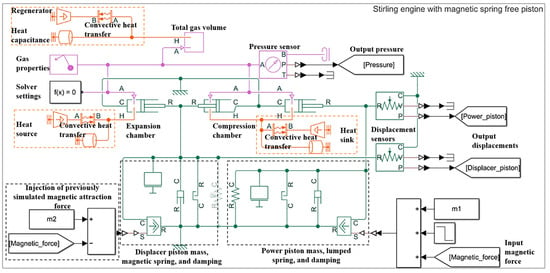

In the block diagram as shown in Figure 6, pneumatic cylinder modules are used to build the hot and cold cylinders, the ends of which are connected to convective heat transfer modules. Mass of the pistons are selected to make sure the effective system natural frequency is identical to that of the prototype. A step signal of force is applied as the initial condition to start the engine. In this simulation, the displacement, cylinder pressure of the hot and cold pistons of the engine are studied and recorded. The magnet spring model is added to the simulation as a function of the distance between the hot and cold pistons, which numerical relationship is obtained from the curve fitting of the simulation results in Section 3.1. The rest of the simulation parameters can be found in Table 2. It is worth noting that the gas temperature in either the compression or expansion chamber is assumed equal to that of the cooler or heater. Under this assumption, heat transfer time is neglected and regarded as instantaneous.

Figure 6.

Simulation block diagram of the combined dynamics. Note: orange color denotes heat transfer model, purple color denotes gas dynamics, green color represents dynamics, and black color represents data input/output.

Table 2.

Transient simulation parameters.

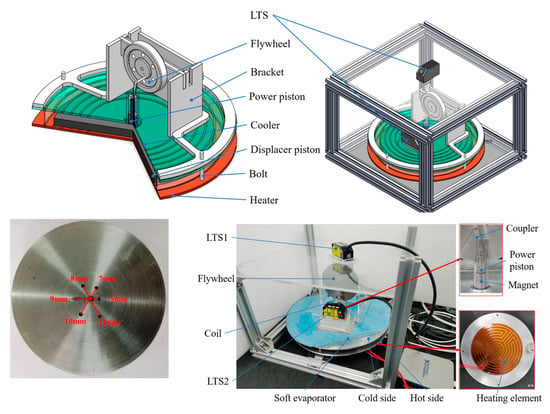

4. Experimental Design

4.1. Prototype Design

In the previous sections, mathematical modeling and simulation setups were carried out for the proposed magnetic-spring Stirling engine. To validate the models and verify engine-start conditions, a prototype was constructed and instrumented with key sensors and data-acquisition devices, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Experimental test bed for the prototype engine.

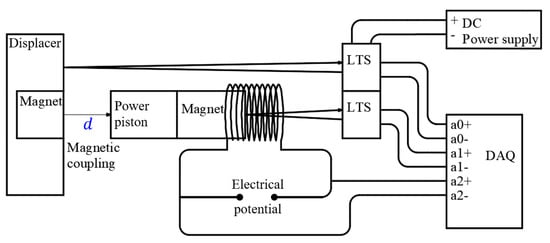

The engine features a large displacer piston (ϕ136, 5 mm thick) made of corrugated board, and an aluminum power piston (ϕ10). A permanent magnet is installed at the center of each piston—one on the power piston and one on the displacer piston. The two magnets are oriented with opposite polarities to create an attractive force between them. An iron flywheel with various crank mounting holes is machined, whose radius ranges from 5 mm to 11 mm. A coil (3250 turns, ϕ20, 25 mm long) is mounted around the power piston cylinder, so that electrical potential is generated as the piston reciprocates. A schematic diagram of signal acquisition is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the experiment.

To measure the dynamics of the pistons, one laser triangulation sensor (LTS) is installed coaxially with the power piston, another LTS is located off-axis but on top of the cold side of the engine, such that both the power and the displacer pistons’ trajectories can be recorded. To measure the generated electric potential, the two ends of the coil were directly fed into the data acquisition card (DAQ). The temperature values of the hot and cold ends of the piston cylinders were measured using K-type thermocouples. The temperature drift between the start and finish point was found experimentally to be within 0.8 K for a 100 s duration, which is safely negligible. Prior to the experiment, the entire test stand was preheated for approximately 10 min, allowing all engine components to reach thermal equilibrium. The sample rate was set at 1000 Hz, and total acquisition time was 100 s.

4.2. Measurement Uncertainty Analysis

The axial displacement values of the prototype are directly measured using two laser triangular sensors (HG-C series, Panasonic, Osaka, Japan), to use as the true value for comparison with the model-predicted results. The displacement sensor has a full measurement scale of 70 mm, with a linearity of ±0.1% full scale, which converts to the following axial displacement sensing uncertainty:

The temperature measurement is conducted by installation of two standard PT-100 sensors on the warm and cool cylinder surfaces, which linearity is 0.607%F.S. Therefore, when the target temperature is between 300 and 400 K, the maximum uncertainty of PT100 measurement is:

The power piston’s range of displacement is 9 mm, 10 mm, or 11 mm in this work, depending on the experimental settings; the displacer piston’s range of displacement is stably around 5 mm. Quantitatively, the measurement uncertainty for the worst-case scenario is 0.7%. Similarly, the worst-case temperature measurement uncertainty is 0.09%. Based on these numbers, the systematic measurement uncertainty of the experiment is low. To account for the environmental impacts, the prototype was fully pre-warmed-up for 10 min, and all of the tests were conducted within 30 min.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Magnetic Constraining Force

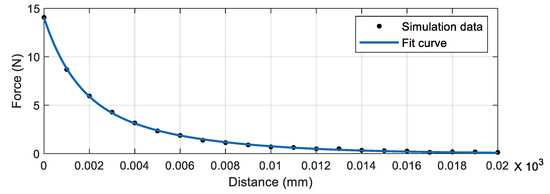

The magnetic attraction force to bond the power and displacer pistons is obtained via finite element simulation as shown in Figure 9, based on the discretized solution field in Figure 4, and the settings in Section 3.1. A quasi-static simulation approach is used to obtain the magnetic field strength and the magnetic attraction force between the hollow cylindrical magnet and the tablet magnet at set intervals between 0 m and 0.02 m. The force between the two magnets is designated as the magnetic spring force, and is obtained as shown in Figure 10. Using first-order rational fitting tools, a good correlation between distance and magnetic force over 0–20 mm is obtained, with an R2 value (coefficient of determination) of 0.99.

where stands for the attraction force in mN, and stands for the distance between the two magnets in mm.

Figure 9.

Simulated magnetic field strength at different distances between the power piston magnet and the displacer piston magnet.

Figure 10.

Magnetic force constraining the two magnets as a function of distance between the two pistons.

It is worth mentioning that, based on the simulated magnetic field strength map, the majority of the magnetic flux is concentrated within the proximities of the magnets. This is as expected since the permeability of the air is very low compared to that of the magnet. It is found that the displacer magnet’s influential area is contained within 5 mm vertically, where the field strength goes to almost 0 Tesla at further distances. Therefore, the magnetic field of the displacer magnet’s effects on the coil can be safely neglected.

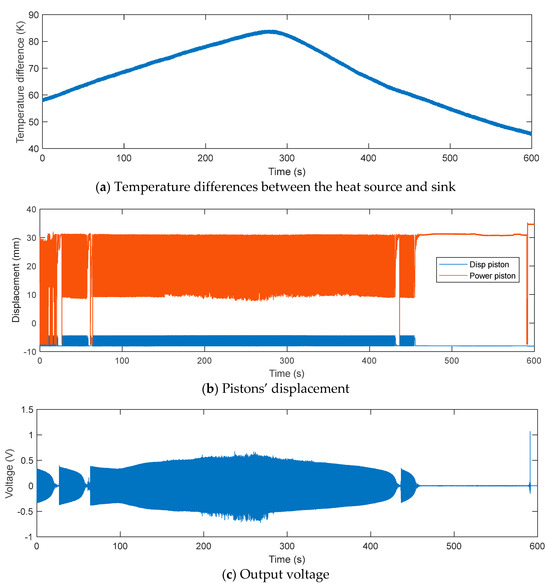

5.2. Engine Function Validation

The prototype FPSE was tested first to validate the basic functionality. During the test, the temperature difference () between the prototype’s heat source and heat sink, the displacement of the pistons, and the generated electrical potential without load were measured. As shown in Figure 11b, the flywheel was pushed manually to attempt to start the engine. It is very interesting to observe that when the temperature difference between the heat source and sink is below 64 K (Figure 11a), the engine failed to operate continuously, which can be observed between 0 s and 60 s in Figure 11b,c. Particularly, Figure 11c clearly shows that the generated electricity potential starts to stabilize after 60 s, and the amplitude of the generated electrical potential between 60 s and 450 s is proportional to the temperature differential between the hot and cold pistons.

Figure 11.

Prototype engine operation recording. Note that (a) shows the difference between the measured heater and cooler temperatures, while (b,c) present the raw data acquired from the data-acquisition system.

5.3. Engine Model Validation

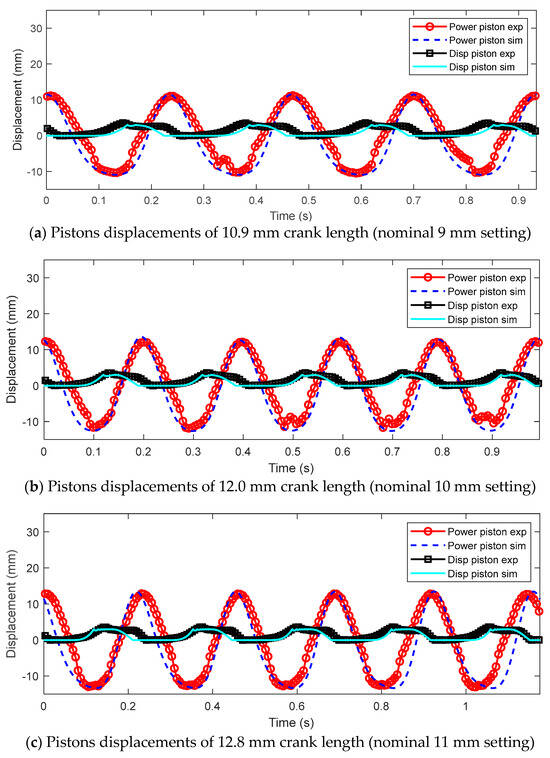

With the functionality of the prototype validated, the models derived earlier in this paper were compared with experimental results next. Using the acquired temperature data at the warm and cool sides of the prototype as input, the models were simulated using the block diagram in Figure 6. The displacements of the power and displacer pistons were used as the indicator for model validation, as shown in Figure 12, where the experimentally measured piston displacements were compared with simulation. Different values of crank length were installed on the flywheel and tested.

Figure 12.

Pistons’ displacements comparison between the simulation and experimental results. Note that the displacement curves of both the power piston and the displacer piston have been shifted together in the vertical direction to align with the adopted coordinate system.

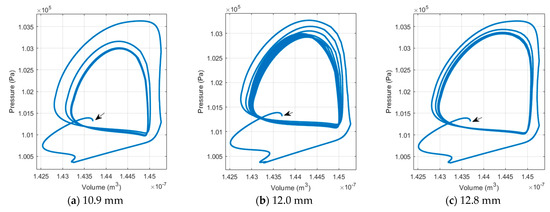

As shown in Figure 12, the models managed to predict the general trends of the prototype’s pistons’ motion. For a 10.9 mm long power piston’s crank, the measured and simulated system frequencies were both at 4.3 Hz; for a 12.0 mm long crank, the frequency was at 5.1 Hz; and for a 12.8 mm long crank, the value was found to be 4.4 Hz. The results are as expected, since longer crank length means wider reciprocation distance, which takes longer durations to cover the full cycle. To evaluate the model’s predictive performance, the relative percentage error was used to quantify the deviation of the simulated piston trajectories from the experimental measurements. Observed in the figure, the maximum deviations were found at the transition phases between the peaks and valleys of the piston displacements. For the 10.9 mm case, the model overpredicted the amplitude of the power piston by 6.7% at peak locations; for the 12.0 mm case, 12.4%; for the 12.8 mm case, 5.9%. The relatively large errors stem from unmodeled factors, such as the spatial motion of the four-bar linkage and oversimplifications inherent in the lumped-parameter approach. Nonetheless, the model successfully captured the shape of the piston trajectories and provides valuable insights into the operating principles of the new engine architecture. Additionally, “vibrations” have been identified at the valleys of the experimental power piston signals. Since laser displacement sensors were used for piston-displacement measurement, engine-induced vibrations can make the coupler link move laterally, diffracting and reflecting the beam near the ends of the piston’s travel and thus producing the irregular valleys in the displacement signal. Also, the actual power-piston displacement range in each case shown in Figure 12 does not equal twice the nominal crank length. This discrepancy mainly arises from manufacturing and assembly tolerances: every component of the prototype was fabricated in-house, relying heavily on laser-lithography techniques. Nevertheless, these deviations in crank length do not compromise the primary objectives of this study. The model still predicted the system frequency with enough accuracy, suggesting the dynamics of the system can be captured by the models in this paper.

Figure 13 shows the ensemble of PV diagrams acquired at three crank-length settings (10.9 mm, 12.0 mm and 12.8 mm). Regardless of the initial offset, the indicator loops collapse onto repeatable trajectories within two to three engine revolutions, signaling the attainment of a cyclic steady state. The 10.9 mm and 12.8 mm configurations stabilize after only two cycles, whereas the 12.0 mm geometry requires three, a behavior that mirrors the different operation frequencies reported in Figure 12. This slightly prolonged transient for the 12.0 mm case is attributed to its highest instantaneous operating frequency: the faster crank acceleration furnishes additional kinetic energy storage that must be dissipated before the thermodynamic and mechanical states equilibrate, hence a marginally extended ring-down period.

Figure 13.

Simulated PV diagrams of the system at different crank length values. Note: the black arrow marks the starting position of the process.

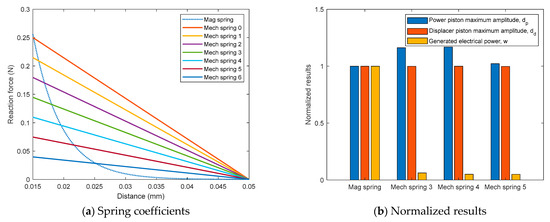

5.4. Effects of Magnetic Spring

The effects of the magnetic constraint (spring) are compared with a traditional free-piston engine, which hot and cold pistons are bounded by a mechanical spring. This baseline engine’s simulation parameters are identical to that of the proposed engine. The only difference is that the magnetic spring is replaced with an ideal mechanical spring (i.e., linear, without damping effects). The elastic coefficient of the mechanical spring between the two pistons is set at seven different values, ranging from −7.13 N/m to −1.13 N/m, as shown in Table 3. The choice of the spring coefficient is based on linear approximation of the pneumatic spring’s reaction force range, as shown in Figure 14a. The results of the proposed FPSE and the baseline are compared in terms of normalized maximum pistons’ displacing amplitudes, , , and the normalized generated electrical power, , shown below:

where and are the simulation time stamps, is a constant related to the electric load, and , , are the maximum pistons’ displacement and the generated electrical work of the magnetic spring case, respectively.

Table 3.

Numerically tested mechanical spring parameters and simulation status.

Figure 14.

Simulation settings and results of the comparative study in terms of choice of spring and spring coefficients for 9 mm crank length case.

As shown in Figure 14b, only the cases 3, 4, 5 of the mechanical spring resulted in stable oscillating motion in the simulation, where the spring coefficients of cases 0~2, and case 6 are either too strong or too weak for the engine to operate continuously. Obviously, the engine with magnetic constraint can generate higher electrical power, according to Figure 14b, where the electrical power generated by the magnetic spring design is 17~20 times more than the baseline mechanical spring groups, despite the fact that the power pistons’ maximum displacement ranges of the mechanical spring cases are higher.

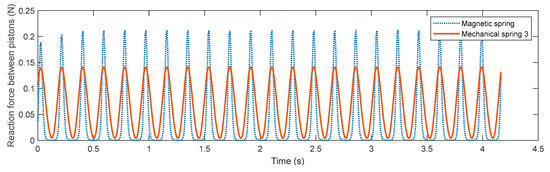

To analyze the observation that the magnetic spring outperformed the baseline mechanical springs in the proposed LTD FPSE, the reaction forces between the power and displacer pistons are compared in Figure 15. This is mainly due to the magnetic spring’s nonlinear distance–force relationship, as shown in Figure 14a. As previously discussed, the magnetic spring force reduces in a fast inversely proportional relationship to the distance, which can be advantageous compared to traditional mechanical springs, thanks to the short range of attraction, as shown in Figure 14. When the distance between the two pistons increases, the magnetic spring’s reaction force reduces much faster compared to that of the mechanical spring, allowing for much lower compression resistance. This is supported by the observation in Figure 15, where the magnetic spring’s reaction time is only approximately 73% of the mechanical one, but the peak amplitude is 50% higher. It is therefore proved that the proposed magnetic spring’s nonlinear distance–force relationship helped the system to maintain operation even when the temperature difference between the heat source and sink was very low, when the traditional engine struggles to maintain a stable operating condition.

Figure 15.

Simulated reaction forces between the power and the displacer pistons.

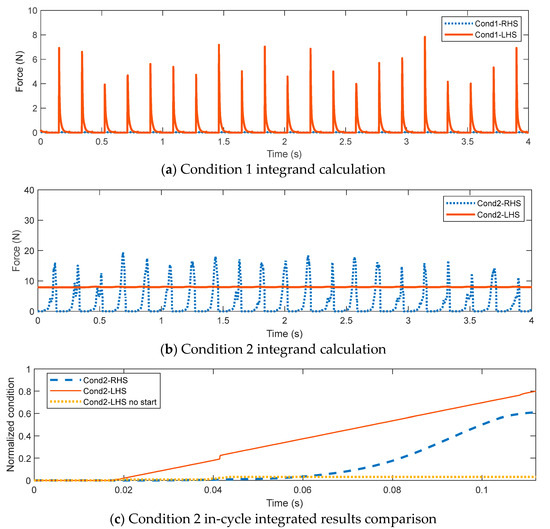

5.5. Engine Start Conditions Discussions

As discussed previously in Section 2.3, both conditions 1 and 2 need to be satisfied that the left-hand side (LHS) of the equation is greater than that of the right-hand side (RHS). To test the engine start conditions developed previously, based on the pseudo codes in Section 2.3, the results are shown in Figure 16. As shown in Figure 16a, the integrand of the LHS is consistently higher than that of the RHS, suggesting that after integration, condition 1 always holds. Though it seems rather simple, it is as expected since the magnetic force is always capable of lifting the displacer piston and withstanding the gas damping and material friction effects.

Figure 16.

Engine start conditions calculations.

As shown in Figure 16b, however, by only examining the integrands of condition 2, it is not obvious to detect whether or not the engine start condition 2 has been met. Therefore, the full condition 2 as in Equation (13) was calculated, and the results for a working cycle as well as for a no-good cycle were found as in Figure 16c. In this graph, it is clear that for a stable running condition, the LHS is consistently higher than the RHS as the integration starts from the beginning of the cycle. As for the no-good cycle, where the pressure of the gas was set to be atmospheric pressure, a reasonable assumption that no thermal energy was delivered to the engine, it is found in this case, the LHS failed to overcome the RHS. In a short summary, by investigating the LHS and RHS of conditions 1 and 2, one is capable of determining whether the engine can operate continuously or not.

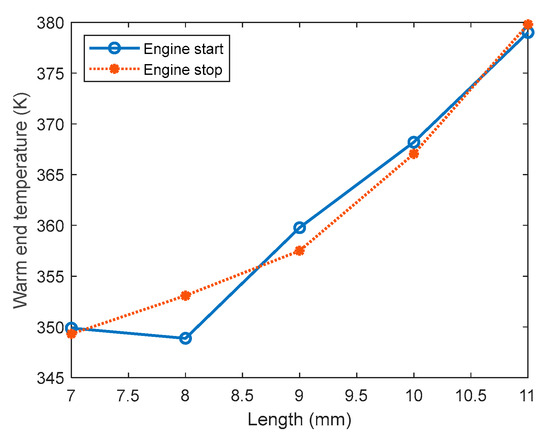

Figure 17 presents the start and stop temperatures of the heater recorded in the lab experiment. The start temperature is the lowest heater temperature at which the engine can start and run continuously; the stop temperature is the heater temperature required to sustain steady operation. It was found that as the length of the crank increased from 7 mm to 11 mm, the required warm end temperature also elevated from 350 K to 380 K. Both the start and stop temperatures are proportional to the length of the crank, which can be explained by the fact that longer reciprocation range means a larger gas volume and more area for heat to dissipate, requiring more thermal energy to reach the same level of pressure force. In general, the start and stop temperatures overlapped with each other. However, in the 8 mm case, the engine start temperature was 5 K lower than the stop temperature, which could be attributed to measurement error, which in this case was 1.4%. Nonetheless, the prototype was found capable of continuous operation when the heater (warm end) temperature () was between 350 K and 380 K, which can be suitable in the solar-oceanic thermal energy to electricity conversion scenarios.

Figure 17.

Recorded prototype start and stop temperatures.

Table 4 benchmarks the present magnetic spring free piston Stirling engine (FPSE) against five designs from the literature by comparing the temperature difference (ΔT) across the hot and cold ends and the resulting rotational speed (RPM), since the rotational speed is one of the direct influencing factors governing the generated power. Data show that raising ΔT generally increases rotational speed of the engine shaft. The prototype reported here achieves 258~324 RPM operation over ΔT = 45~84 °C, positioning it at the upper performance envelope for ultra-low-grade heat applications, which validates the effectiveness of the magnetic-spring FPSE concept.

Table 4.

Temperature difference and engine rotational speed comparison with reported work.

Finally, in terms of potential application of this engine, the hundreds of Kelvin temperature difference requirements in the traditional Stirling engines are not compatible with the small and isolated deployed ocean monitoring devices, where the proposed LTD engine can be of great use. It can also be of use in the waste heat recovery from low temperature sources such as the housing of an internal combustion engine (ICE), which surface temperature is usually well below the boiling point of liquid water at sea level atmospheric pressure but is extractable with the proposed engine. In future work, better sealing and heat transfer design, as well as more powerful permanent magnets with efficient coils, can be designed and tested for further improved low temperature heat recovery.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, facing tight space requirements onboard a data buoy, a low-temperature piston Stirling engine using the ocean as a heat sink was proposed, modeled, simulated, and experimentally validated. Experimental results show that the prototype can sustain operation with a heater-to-cooler temperature difference of 58–84 K and a flywheel speed of 258–324 RPM. The key findings of this paper are:

- The proposed magnet attraction constraint and its corresponding nonlinear attraction force characteristics allow for lower temperature differential operation of the Stirling engine, where traditional mechanical piston coupling fails.

- Direct integration of electrical coils onto the power piston can greatly reduce the complexity of energy conversion, where the mechanism to convert the translational motion of the power piston to the rotation of an electrical generator is no longer needed, improving the compactness of the system.

- Based on the developed engine start conditions, it is now possible to evaluate the engine operation continuity.

Based on the experimentally obtained results, the low temperature difference allows for a wide range of operational areas, from the Arctic Ocean, Pacific Ocean, or even inner lakes, where a stable temperature difference around the magnitude of boiling water can ensure the operation of the prototype. In future work, more detailed power generation and optimized coil geometries are believed to be the keys to better performing engines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T.; Methodology, H.T.; Formal analysis, H.T. and Z.G.; Investigation, Z.G.; Resources, Y.G.; Data curation, Z.G.; Writing—original draft, Z.G.; Writing—review & editing, H.T. and Y.G.; Visualization, Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was jointly funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51705061), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2020YFB2009803).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Heat Transfer Model

Figure A1 depicts the heat-transfer configuration of the engine. Treating the highlighted surfaces as constant-temperature heat sources and all remaining boundaries as adiabatic, the internal heat-flux distribution under natural convection conditions is fully specified.

where, is the convective heat transfer coefficient, and and are the expansion and compression chamber heat transfer surface area.

The enthalpy change resulting from the mass flow of gas through the boundary (the clearance between the displacer piston and the housing) can be defined as:

where is the mass flow rate of the gas, and is the temperature of the gas at the boundary.

Figure A1.

Heat transfer diagram of the dynamic system.

References

- National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). Coastal Water Temperature Guide. Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/coastal-water-temperature-guide/ (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Kodama, T. High-temperature solar chemistry for converting solar heat to chemical fuels. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2003, 29, 567–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataineh, K. Hybrid fuel-assisted solar-powered stirling engine for combined cooling, heating, and power systems: A review. Energy 2024, 300, 131506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, A.; Varedi-Koulaei, S.M.; Ahmadi, M.H.; Ahmadi, H. Dynamic synthesis of the alpha-type stirling engine based on reducing the output velocity fluctuations using Metaheuristic algorithms. Energy 2022, 238, 121686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Louis, E.M.; Thomas, B.; Anurag, K.; Sankar, V.; Pullan, T.T. Fabrication and testing of a gamma type stirling engine. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 9641–9645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, M.; Suzuki, S.; Abe, Y. Development of a low-temperature-difference indirect-heating kinematic Stirling engine. Energy 2021, 229, 120577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-H.; Yang, H.-S.; Tan, Y.-H. Theoretical model of a α-type four-cylinder double-acting stirling engine based on energy method. Energy 2022, 238, 121730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yu, G.; Dai, W.; Zhang, L.; Luo, E. Dynamic and thermodynamic characterization of a resonance tube-coupled free-piston Stirling engine-based combined cooling and power system. Appl. Energy 2022, 322, 119437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalado-Rodríguez, N.; Militello, C. Comparative study of the effects of increasing heat transfer area within compression and expansion chambers in combination with modified pistons in Stirling engines. A simulation approach based on CFD and a numerical thermodynamic model. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 268, 115930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaravelu, T.; Saadon, S.; Abu Talib, A.R. Heat transfer enhancement of a Stirling engine by using fins attachment in an energy recovery system. Energy 2022, 239, 121881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, F.; Yu, M.; Liu, W.; Liu, Z. Heat transfer characteristics of enhanced cooling tube with a helical wire under oscillatory flow in Stirling engine. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2021, 168, 107063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, R.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, S. Numerical analysis of fluid dynamics and thermodynamics in a stirling engine. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 189, 116727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nimr, M.; Khashan, S.A.; Al-Oqla, H. Novel techniques to enhance the performance of Stirling engines integrated with solar systems. Renew. Energy 2023, 202, 894–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhong, G.; Niu, Y.; Liu, Y. Performance optimization of a free piston stirling engine using multi-section regenerators based on the response surface methodology. Energy 2022, 261, 125221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahadi, F.; Azadi, M.; Biglari, M.; Madani, S.N. Study of coating effects on the performance of Stirling engine by non-ideal adiabatic thermodynamics modeling. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 3688–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moura, E.F.; Henriques, I.B.; Ribeiro, G.B. Thermodynamic-Dynamic coupling of a Stirling engine for space exploration. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2022, 32, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topgül, T.; Okur, M.; Şahin, F.; Çınar, C. Experimental investigation of the effects of hot-end and cold-end connection on the performance of a gamma type Stirling engine. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2022, 36, 101152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Kim, I.; Kim, D. Hybrid energy harvesting system based on Stirling engine towards next-generation heat recovery system in industrial fields. Nano Energy 2021, 90, 106508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, D. Numerical and Experimental Studies on Free Piston Stirling Engines. Master’s Thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2012. Available online: https://drum.lib.umd.edu/handle/1903/12817 (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Tian, H.; Zhao, S.; Gong, Y. Study of piston trajectory parameters on the performance of a kinetic Stirling engine. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A J. Power Energy 2022, 236, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakolpour, A.R.; Zomorodian, A.; Golneshan, A.A. Simulation, construction and testing of a two-cylinder solar Stirling engine powered by a flat-plate solar collector without regenerator. Renew. Energy 2008, 33, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongtragool, B.; Wongwises, S. A four power-piston low-temperature differential Stirling engine using simulated solar energy as a heat source. Sol. Energy 2008, 82, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheith, R.; Aloui, F.; Nasrallah, S.B. Determination of adequate regenerator for a Gamma-type Stirling engine. Appl. Energy 2015, 139, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sripakagorn, A.; Srikam, C. Design and performance of a moderate temperature difference Stirling engine. Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 1728–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutammachte, N.; Knorr, J. Field-test of a solar low delta-T Stirling engine. Sol. Energy 2012, 86, 1849–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).