1. Introduction

As research and current accident data show, the majority of accidents are attributed to human errors [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. From 2014 to 2020, up to 53% of ship accidents were due to human errors in the European waters [

1]. The overall collision risk is especially high in coastal waters and congested areas, like ports [

6].

Especially in ports, navigating safely in confined waters is challenging due to other traffic, port infrastructure, and the environmental conditions, like gusty winds or low visibility. A prevalent approach to automated obstacle detection involves utilizing image recognition algorithms. In recent years, AI-based systems leveraging neural networks have been increasingly employed for image recognition [

7]. These algorithms utilize image data from onboard camera systems to proactively identify potential obstacles. Such information can then be provided to the onboard crew as decision support, aiding in making informed navigational choices. These commercially available products are already being used on ships today, primarily targeting large shipping companies for deep-sea freight transportation.

However, these systems are less suitable for obstacle detection in port areas, where static harbor objects, such as quay walls, piles, and buoys, pose a significant threat to vessels operating within harbor basins or close to the coastline.

This results from a very limited selection of suitable candidates [

8,

9]. Currently, only Fa few datasets are available that are suitable for training AI models based on neural networks—examples are the “Singapore Maritime Dataset” (SMD) and the “SeaShips7000” dataset [

8]. Most other datasets are either too small, not optimized for object recognition use cases, or utilize satellite images [

8]. However, both the SMD and the SeaShips7000 datasets focus on recognizing various types of ships [

8]. The SMD comprises a total of ten classes, including six ship classes [

9]. Among static harbor objects, only a “buoy” class is represented [

10]. The SeaShips7000 dataset exclusively covers ship types and is specialized for object recognition on rivers [

8,

9,

11].

This work presents a framework to create port-specific datasets needed to account for the differences in harbor infrastructure, which differ from harbor to harbor. As a proof of concept, this paper is going to consider the port of Emden as the operational area of an autonomous vessel. Therefore, the training dataset is going to contain objects specific to this area. However, the proposed method can be adapted to any other port by tailoring the training dataset to the specific conditions on site.

2. Related Work

The maritime domain presents a unique challenge for object detection used in autonomous systems, with many applications relying on accurate identification and tracking of vessels, buoys, and other marine features. However, current studies neglect optical detection of static port objects, such as quay walls, pillars, or buoys. The following section gives an overview of current research in the context of vehicle and vessel automation. The former part presents developments in the automotive domain while the latter part focuses on scientific contributions that have been achieved in the maritime domain.

Khatab et al. [

12] examine the suitability of various sensors, such as RGB cameras, radar, and lidar sensors, as well as different deep learning models like Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks (R-CNN), Single Shot Detector (SSD), and YOLO for achieving automated object detection in the context of autonomous driving. The study concludes that optimal object recognition can only be achieved through the combination of different sensors, a diverse and domain-specific dataset for training the AI models, and the use of real-time capable deep learning models like YOLO. The authors believe that only by supplementing RGB cameras with active sensors (radar and lidar) can object distances be reliably detected in a three-dimensional space [

12].

Chen et al. [

13] explore a railway-focused LIDAR-based perception approach for real-time environment monitoring. The authors propose an efficient dynamic feature-encoding algorithm based on voxels. This conversion of point clouds into 2-D voxels reduces computational effort, removing redundant processing steps. The authors state that the resulting system outperforms state-of-the-art methodologies, especially when it is applied to large point clouds [

13].

Kanchana et al. [

14] explore automated object detection in autonomous driving, focusing on evaluating various machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models in computer vision. They conduct a meta-analysis of relevant scientific articles, examining two-stage detectors like Fast R-CNN and Faster R-CNN, as well as single-stage detectors like YOLO and SSD, including both simple CNNs and R-CNNs. Additionally, they com-pare passive sensors (simple cameras) with active sensors (radar and lidar). The study concludes that ML and DL models are indeed suitable for autonomous driving, but precision must be improved to avoid endangering lives. Currently, a major issue is the lack of high-quality and sufficiently large training datasets for these models. However, with modern technologies, collecting such data is becoming easier and can enhance the predictive accuracy of the models [

14].

Singh and Arat [

15] explore DL applications in the automotive industry, with the primary use case being autonomous driving support. DL is utilized to automate the detection of objects like traffic lights, road signs, and lane markings by combining camera, lidar, and radar data. It can also monitor the driver’s attention level. CNNs are mainly used in these areas due to their high efficiency. DL algorithms can also be applied for vehicle health monitoring, predicting wear, and warning the driver in advance. Addition-ally, cameras can automatically detect and evaluate existing damages to vehicles. The authors identified data-driven product development support as a fourth DL application, which can help manufacturers reduce recall numbers [

15].

While the automotive industry is a key driver in the development of novel detection methods used in automated vehicles, the maritime domain faces specific challenges not relevant to the automotive domain. These include, among others, differences in vehicle types or environmental conditions that might not be relevant in the automotive domain. Therefore, the following section focuses specifically on solutions based in the maritime domain.

Dosovitskiy et al. [

16] introduce the concept of Vision Transformers as an alternative to CNNs. During this process, the image is split into patches and then input into a transformer along with information about the sequence of these patches. Image patches are treated the same way as tokens are in natural language processing where transformers were previously used. The model is trained in a supervised fashion.

Xue et al. [

17] explore an improved Vision Transformer applied to the topic of unmanned aerial vehicle tracking. To enable the edge computing capabilities necessary to fulfill the task onboard the drone, the authors adapt existing Vision Transformers by introducing a selection module to disable not needed layers and therefore improve computation time while balancing the accuracy–speed trade-off.

Statheros et al. [

18] examine the suitability of mathematical models and soft computing approaches, such as neural networks, evolutionary algorithms, and fuzzy logic, to implement navigation and collision avoidance using image recognition in autonomous ships. According to the authors, mathematical models are particularly helpful when environmental influences remain constant. With increasingly dynamic environments, the benefits of AI approaches, including real-time capabilities, increase. By combining neural networks, fuzzy logic, and mathematical algorithms, good collision avoidance performance can be achieved in both static and dynamic environments, even though such systems are challenging to design and implement. The authors believe that autonomous technologies will only find application in shipping when the uncertainties associated with these technologies are smaller than those arising from human actors [

18].

Nanda et al. [

19] introduce “KOLOMVERSE”, an open-source object detection dataset for maritime objects. It comprises 2,151,470 4K images taken by 17 ships off South Korea’s coast, featuring high diversity. Unlike other datasets, KOLOMVERSE includes annotations for various maritime objects beyond ships, such as wind turbines, lighthouses, and buoys. The images capture different light conditions, waves, wind, and other weather conditions, like rain and snow. The authors tested YOLOv3, YOLOv4, SSD, Faster RCNN, and Center-Net models on the dataset, with the Center-Net model achieving the highest prediction accuracy (mAP_0.5 = 61.86%). To further enhance the dataset’s diversity, the authors aim to integrate additional object classes into the KOLOMVERSE dataset, thereby addressing the existing class imbalance (82.9% of all instances being ships) [

19].

Fefilatyev et al. [

20] evaluate a method for detecting and tracking ships using a cam-era buoy. It was observed that frequent perspective changes caused by waves significantly reduced the prediction accuracy of the models. To address this issue, an algorithm for horizon detection was developed to standardize the camera images’ perspective. This approach led to substantially more reliable results in ship detection and tracking using the employed AI algorithms [

20].

Zhang et al. [

21] focus on optimizing an object detection model for ships and swimmers in foggy weather. They used the YOLOv4_tiny model, known for real-time predictions and high accuracy. They created a custom dataset with 3838 images of ships and humans in the water and used an algorithm to simulate a foggy environment. The YOLOv4 model underwent three optimizations to make the detection of smaller objects more reliable and enhance the feature extraction process by focusing on the most important features. The created SRC-YOLO model achieved a mean average precision of 86.15%, surpassing YOLOv4-tiny (79.56%). Further work involves optimizing for different weather conditions and improving detection of small objects [

21].

Kaido et al. [

22] focus on detecting and tracking ships in camera images. They use a combination of a Laplace filter and a Support Vector Machine (SVM) for ship detection and localization. The SVM is used to examine the proposals generated by the Laplace filter and filter out erroneous candidates, such as waves and reflections. Ship tracking is implemented using a particle filter. Although the developed approach already achieves good results, further improvement in ship tracking could be achieved by incorporating additional information such as current speed, ship course, 3D cameras, radar, and AIS data [

22].

Moosbauer et al. [

10] establish a benchmark dataset for the maritime domain using the existing Singapore Maritime Dataset (SMD). The authors propose a train-validation-test split for SMD to ensure reproducibility and comparability. They also devised an algorithm to create segmentation labels for the dataset. The performances of the Faster R-CNN and Mask R-CNN models were evaluated on this newly created benchmark dataset. It was found that Mask R-CNN particularly excels in accurate object detection in the maritime domain. Both models struggled with detecting small and overlapping objects, and foggy weather conditions resulted in detection errors [

10].

Bovcon et al. [

23] develop an algorithm called “ISSM” in MATLAB for detecting obstacles in water and the horizon. The evaluation used the “Maritime Obstacle Detection Dataset 2” (MODD2), captured by a small unmanned surface vehicle (USV) with a stereo camera system, covering various weather conditions. The dataset covers various weather conditions, such as fog and sun reflections. The algorithm incorporates data from the inertial measurement unit (IMU) of the USV to improve horizon detection. Under this approach, all pixels in the images are assigned to three areas: sky, coast, and sea. The method can also detect small and large objects in the water. Evaluation showed that ISSM outperforms the former state-of-the-art model “SSM” in horizon and object detection regarding prediction accuracy [

23].

Spraul et al. [

8] explore the suitability of various state-of-the-art object detection models for ship detection. The authors analyze publicly available datasets to assess their adequacy as training data and benchmarks in the maritime domain. Alongside popular datasets like MS COCO and PASCAL VOC, domain-specific datasets such as the Singapore Maritime Dataset and SeaShips7000 are considered. The evaluated models include Faster R-CNN, Cascade Faster R-CNN, Libra R-CNN, RetinaNet, and FCOS, with FCOS proving to be the most suitable for this application. The trained FCOS model was then used to assess the datasets’ generalization ability by conducting training runs on them. Overfitting was observed, especially on the SeaShips7000 dataset. The best results were achieved when the FCOS model was trained on a combination of all datasets and supplemented with additional web-crawled content [

8].

Fernandes et al. [

24] explore DL techniques in computer vision for maritime applications. The authors reviewed scientific papers, examining their goals, datasets, and DL models used. The most common use case was ship detection and localization (object detection or instance segmentation) using either water surface images or satellite imagery. Other objectives included underwater equipment detection (pipes, valves), coral and marine life localization and classification, underwater mine detection, and oil spill detection. The CNN architecture was most frequently employed, with Fast R-CNN showing the best performance for ship detection. CNN-based models like ResNet-50 and VGG-16 were also used frequently for coral detection [

24].

As evident from the description of related works, current research in automated object detection in the maritime domain almost exclusively focuses on ship detection [

8,

10,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23], while static port objects are either not considered or inadequately addressed. Quay walls and piles are not found in any of the examined works. Buoys were only included as a target class in Nanda et al. [

19]. This existing research gap will be addressed in this study by investigating the suitability of AI models for automated detection of static port objects.

3. Method

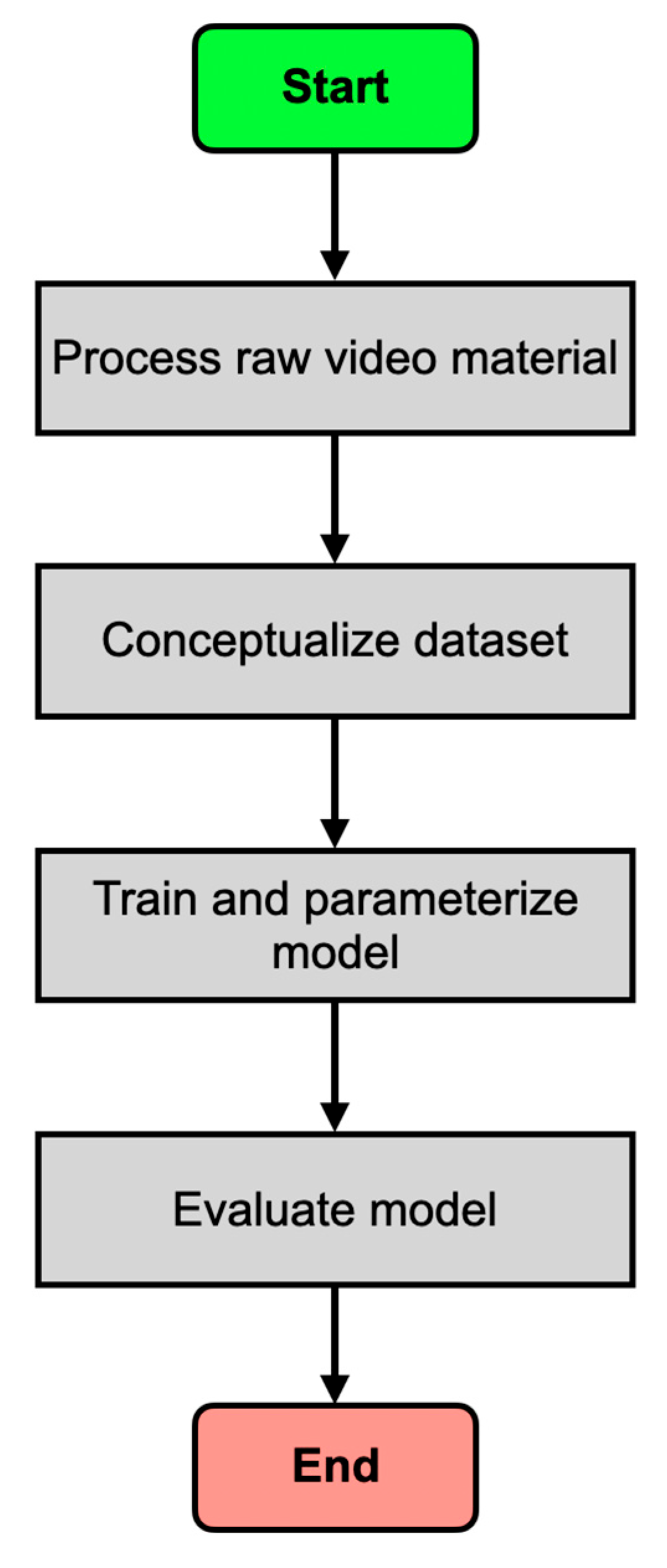

As shown in

Section 2, there is currently a research gap that exists due to the lack of training data for static infrastructure commonly found in ports. Even though some of these structures are locally occurring phenomena, autonomous vessels that operate in these areas need to be able to correctly identify these to guarantee safe operation. The process is divided into four steps. The first step (see

Figure 1) of the project was to build a domain-specific object detection dataset for the detection of static port objects based on camera images from the port of Emden. This was necessary as currently there is no freely available object detection dataset that includes static port objects, such as quay walls and piles. Prior to annotating these images, frames had to be extracted and processed from the provided raw video material. Subsequently, the static port objects—in this case, quay walls and piles—were labeled using bounding boxes. Once this process was completed, the annotations underwent quality control to correct any errors. In the next step, the dataset was prepared by applying a data augmentation.

Afterward, the next step was to select a suitable AI model. It was decided to implement the object detection model “YOLOv5s6” to answer the research question. The model was then parameterized to achieve optimal adaptation to the specific use case—the automatic detection of static port objects using camera images from the port of Emden. Once the parameterization was completed, the performance of the final model iteration was evaluated using appropriate performance metrics. This approach allowed for an assessment of how well the implemented model was suited for automated detection of static port objects. Additionally, it facilitated the quantification and evaluation of the model’s strengths and weaknesses. As part of the performance evaluation, a final step involves investigating the extent to which the model is capable of reliably detecting images of static harbor objects from different port areas.

As part of the performance evaluation, a final step was to investigate to what extent the model is capable of reliably detecting quay walls and piles on images recorded in other port areas.

3.1. Processing of the Raw Video Material

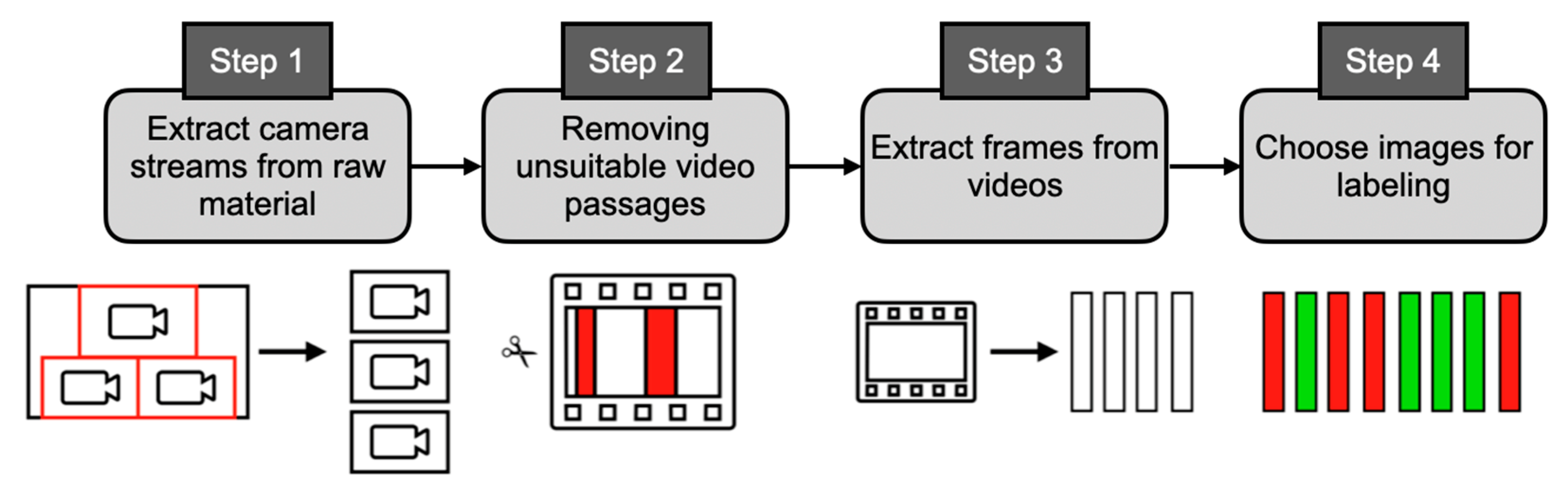

The preparation of raw video material involves obtaining the images ready for labeling.

Figure 2 illustrates the four steps that needed to be performed during the data preparation process.

In the first step, it was essential to ensure that the three camera streams were extracted from the provided videos. An ML algorithm learns where target objects appear more frequently in the images. Training on the unprocessed raw material would lead to the model not being adequately prepared for use in the port of Emden. During training, the ML algorithm would adapt to the specific locations of objects in the three camera streams of the raw material. However, in reality, there are no images that combine all three camera views in one frame. The large black areas between the camera streams are not present in actual use cases. In the productive environment, the model works on frames that fill the entire image. Training on the unprocessed raw data would lead the model to assume that the target objects are much smaller than they actually are in reality. All of this would negatively impact the model’s accuracy in the productive environment.

In the second step, unsuitable video passages needed to be removed from the previously extracted video streams. This primarily involved removing segments where the camera boat was not moving. This measure ensured that not too many nearly identical images were integrated into the dataset. Integrating such similar images into the dataset would cause the model to overly adapt to recognizing the same quay walls and piles repeatedly. Consequently, the model would lose its ability to generalize effectively.

Next, the videos needed to be divided into individual frames. It is also essential to ensure that too many nearly identical images are not created. To prevent this, only one image per second was extracted from the videos; all other frames were discarded. This approach is recommended to avoid overfitting the model [

10].

In the last step, the images that will be part of the dataset were selected. The selection was performed randomly from the pool of extracted frames. This measure ensured that all segments of the videos were represented in the dataset to increase diversity and improve the model’s robustness.

3.2. Conceptualization of the Dataset

In this step, the quay walls and piles contained in the images from the port of Emden were annotated using bounding boxes. After completing the labeling process, a final quality control of the dataset was conducted. During this control, the quality of the labels was reviewed, and any inaccurate or erroneous bounding boxes were corrected. This included annotations with incorrect class labels or improperly placed bounding boxes. Additionally, any objects that were overlooked during the initial annotation process were manually reannotated.

It was crucial that the dataset represents the two target classes in a diverse manner to prepare the trained model for real-world deployment. To achieve this, the objects should be depicted from various perspectives and angles, at different distances, under varying weather conditions (sunny, cloudy, rainy, or foggy), and lighting conditions, as well as during different times of the day. Overlaps between objects, intersections with other objects in the surroundings, and the image borders should also be included to enhance the robustness of the AI model. However, the existing images from the port of Emden only partially fulfill these diversity requirements. A beneficial aspect is that the recordings were captured by three different cameras, providing three different perspectives and angles of the quay walls and piles. The cameras also have a slight variation in their tilt, resulting in varying inclination angles of the depicted quay walls and piles. Overlaps between piles and quay walls, as well as intersections with other objects in the surroundings, were also represented. On the downside, the recordings were exclusively taken in broad daylight and under sunny or cloudy skies. This limitation could have potentially impacted the model’s performance in scenarios with different lighting conditions or weather situations.

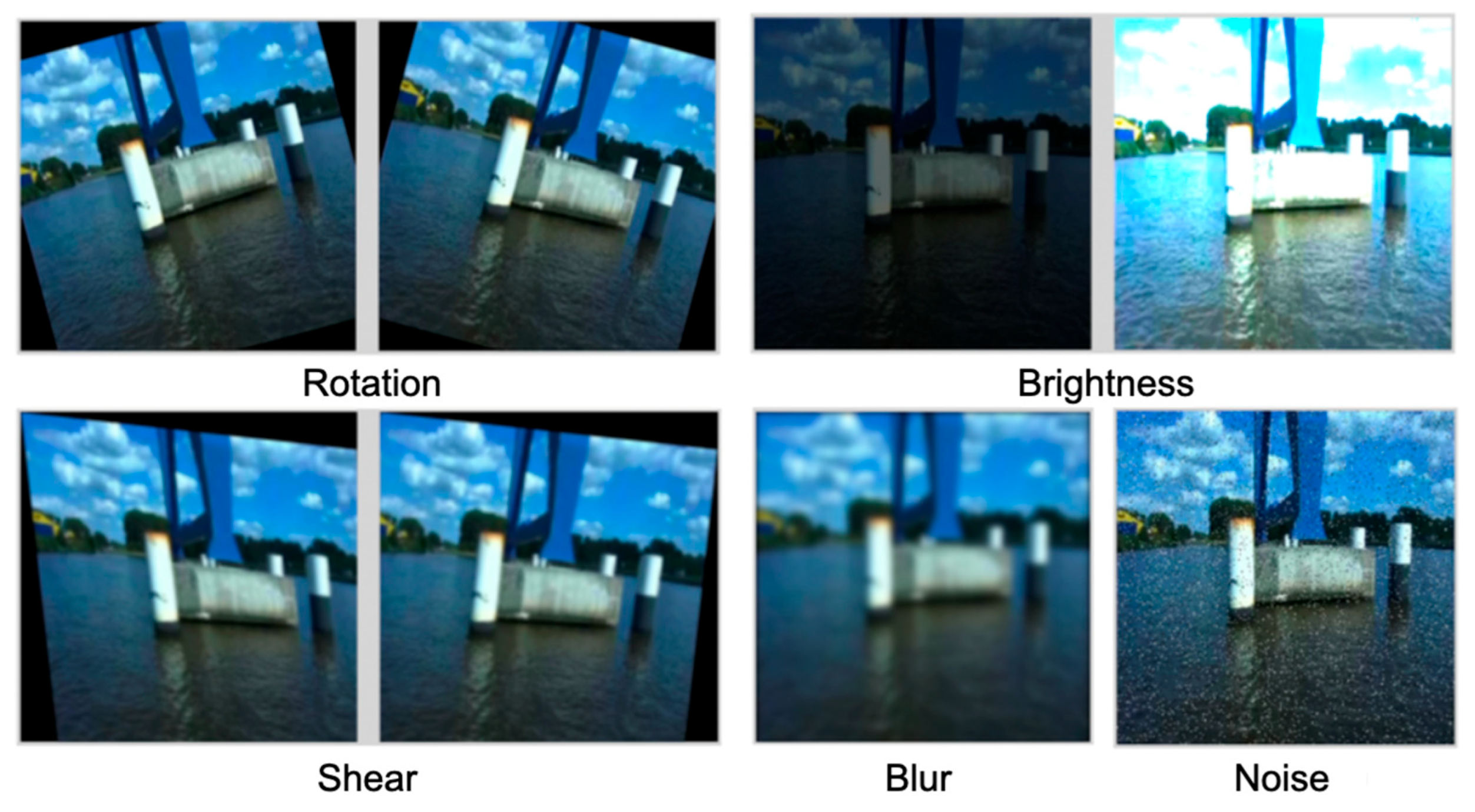

To improve the diversity of the dataset and prepare the model for real-world deployment, data augmentation was used. Data augmentation allows artificial expansion of the size of the dataset by adding modified copies of the original images [

25]. By applying data augmentation, the diversity of the dataset increases, which reduces the risk of overfitting the model [

25]. Another advantage is that this technique enables the simulation of various weather and lighting conditions, as well as changes in perspective.

Figure 3 illustrates the transformation steps that have been applied as part of the data augmentation as demonstrated in [

26]. First, rotation ([−5°, +5°]) and shearing ([−5°, +5°]) were performed to simulate fluctuations caused by strong winds and/or rough seas. These fluctuations lead to changes in the camera’s perspective and angle on the port objects (slight tilting). The brightness augmentation ([−60%, 60%]) was used to imitate different lighting conditions. Artificial darkening of the images allowed the model to recognize objects in dim light conditions during real-world deployment. The implementation of image noise (10%) helped simulate rain, hail, snow, or fog and prepare the model for technical disturbances [

27]. The artificial blurring (2 Pixel) of images was used to simulate water droplets on the camera lens. Moreover, it can simulate scenarios where one or more cameras lose focus.

The resulting labeled dataset contains 6811 images in total that contain 20,110 annotations. The dataset was divided into a train-validation-test split set in a 60:20:20 manner as recommended by [

28]. This results in 4087 images used in the training set, 1357 images in the validation set, and 1362 images in the test set. After augmentation the dataset contains 10,240 images containing 30,315 annotations. The size of the training set is increased to 7514 images, while the size of the validation and test set stay the same.

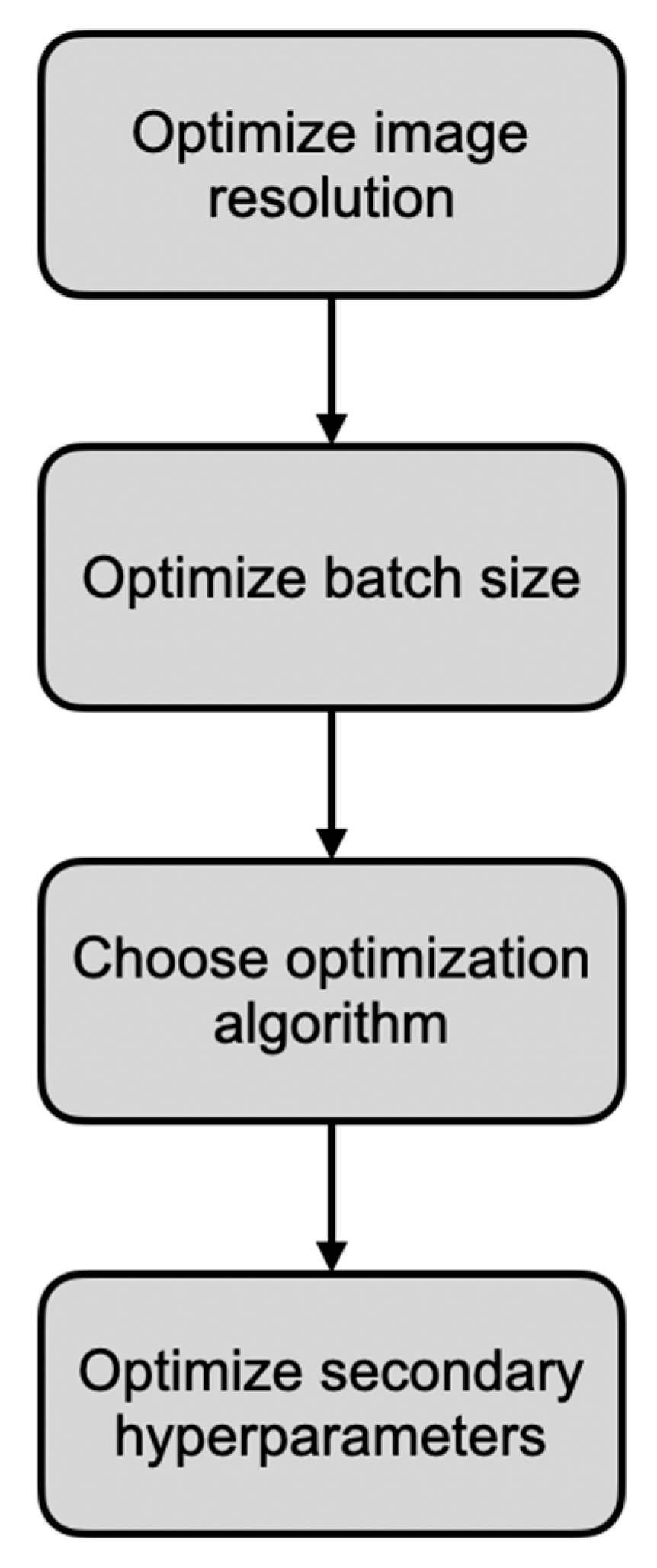

3.3. Hyperparameter Optimization

In order to detect the quay walls and piles on the previously constructed dataset, an in-house pre-trained YOLOv5s6 instance was used. This approach aimed to reduce the risk of model overfitting and accelerate the training process [

29].

The YOLO model has a variety of adjustable hyperparameters. It is possible to manually pass a portion of these parameters during the execution of the training script. Examples of these parameters include the resolution of input images, the number of trained epochs, the batch size, and the optimization algorithm used. The batch size indicates how many training examples are processed by the model before the internal model parameters are updated by the optimizer [

28,

30]. These four model parameters significantly impact the eventual model performance and the time and computational power required for training.

In addition to these “primary” hyperparameters, there are numerous other “secondary” hyperparameters that can be optimized for the YOLOv5 model. Unlike primary hyperparameters, these secondary parameters cannot be manually passed as arguments to the training script; instead, they must be provided in a separate hyperparameter configuration file. Examples of secondary hyperparameters include the learning rate, momentum, or the Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold used for training. Due to the large number of secondary hyperparameters, it is not practical to manually try out all possible hyperparameter combinations. Instead, a genetic algorithm was used to increase the likelihood of finding an optimal hyperparameter combination.

Figure 4 illustrates the process of hyperparameter optimization. A total of four experiments were conducted. The division into four separate experiments was aimed at clarifying the cause-and-effect relationship between individual hyperparameter settings and the model performance.

The first three experiments concentrated on tuning the three primary hyperparameters: image resolution, batch size, and the chosen optimization algorithm. In the fourth step, the optimization of secondary hyperparameters took place. To establish a basis for comparison, the model instances parameterized within the scope of the four experiments were trained for 100 epochs each.

In the first experiment, the goal was to determine an appropriate resolution for the input images. For this purpose, the three resolutions [640 × 640], [1280 × 1280], and [1280 × 720] were compared. [640 × 640] corresponds to the standard image resolution of the YOLOv5 model. YOLOv5 offers an additional model family alongside the standard model variants, supporting a maximum image resolution of [1280 × 1280]. YOLOv5 also accommodates the processing of rectangular images with a 16:9 aspect ratio. The [1280 × 720] resolution corresponds to the native resolution of the images in the previously created dataset. By comparing the resolutions [640 × 640] and [1280 × 1280], the aim is to evaluate whether an increase in image resolution indeed leads to improved performance, particularly for smaller objects. The investigation of the [1280 × 720] resolution aims to assess the extent to which using the native image resolution impacts the model’s performance and the training process.

In the second experiment, the influences of different batch sizes on required training resources and model performance were investigated. Generally, it is recommended to set the batch size as high as possible [

31]. In this experiment, the training began with a batch size of 16. Subsequently, the value was doubled as is common practice in the field (32, 64, 128, etc.). This process continued for as long as it was supported by the hardware.

In the third experiment, the selection of an appropriate optimization algorithm took place. All optimizers provided as default choices by the YOLOv5 model were examined. YOLOv5 offers the option to choose between three optimization algorithms: “SGD with Nesterov momentum”, “Adam”, and “AdamW”.

In the final experiment, the secondary hyperparameters were optimized using the genetic algorithm integrated into YOLOv5. Subsequently, the extent to which this approach can contribute to improving model performance will be investigated.

For training the final model, the parameters determined to be optimal through hyperparameter optimization were used. In all previous experiments, the models were trained for 100 epochs each. However, in this context, the epoch limit was removed to determine the optimal number of epochs for training the final model. To identify the optimal number of epochs, a technique known as “early stopping” was implemented. Early stopping involves terminating training prematurely when there is no further improvement in performance over a certain number of epochs [

30]. To prevent overfitting, it was important to ensure that the validation loss remained consistently low and did not start increasing again in the final epochs [

28].

In the context of the conducted experiments, the impacts of different hyperparameter configurations on the predictive accuracy and speed of the implemented model were examined. To evaluate predictive accuracy, two performance metrics, mAP_0.5 and mAP_0.5:0.95, were used. Model speed was evaluated through the metrics of inference time and frames per second (FPS). Besides these primary performance metrics, additional metrics such as precision–recall curves and loss curves were also used, if necessary, to interpret the results. In addition to the model performance, the influences of different hyperparameters on required training resources were investigated. For performance metrics, both training duration and memory requirements (system RAM and GPU memory) were collected and analyzed.

Within the context of performance evaluation, an investigation was also conducted to determine if the observed performance metrics of the final model could be transferred to other use cases. Since no suitable dataset existed to depict quay walls and piles from other harbor areas, a collection of 30 internet images was assembled for this purpose. These images were then processed by the trained model to make predictions. This approach helped assess the model’s capability to recognize foreign harbor objects and determine the extent to which the model can be adapted to different scenarios.

All training and evaluation were conducted on a single NVIDIA A100-SXM4-40GB with 40 GB of VRAM, an AMD EPYC 7742 CPU, 83.5 GB RAM, and storage capacity of 166.8 GB.

4. Evaluation

Due to space constraints, only the results of the last two experiments will be described in this section. Based on these research findings in experiment one, the decision has been made to use an image resolution of [1280 × 720] in subsequent training runs. This parameter setting allows for a favorable cost–benefit ratio. On the one hand, the model could achieve a significantly higher accuracy—especially in detecting the smaller piles objects—compared to the model using an image resolution of [640 × 640]. On the other hand, the training resources required for this model can be reduced by up to 50 percent compared to the [1280 × 720] image resolution model. Another advantage is that the camera images generated in operational use do not require any additional preprocessing steps in this case, as would be necessary for the other two models. This helps to improve the responsiveness of the model.

Based on the research findings in experiment two, the decision was made to use a batch size of 64 for training the models in subsequent experiments. While this parameter setting does have the drawback of requiring more system and GPU RAM, it can lead to an improved accuracy in detecting quay walls and piles within the IoU interval of 0.5 to 0.95. Additionally, utilizing the maximum supported batch size allows for a reduction in the training duration.

4.1. Optimization of the Used Optimization Algorithm

In the first step, the ability of the three optimization algorithms to minimize the box loss of the training and the validation set was evaluated. It was evident that in both cases, the most effective reduction in loss could be achieved when the model employed the SGD optimizer. After 100 epochs, the AdamW and SGD optimizers achieved box loss values of 0.0259 and 0.0232, respectively, on the validation set. The Adam optimizer yielded a significantly higher loss of 0.0383 (+48% and +65%) in comparison. In the training set, the box loss of the AdamW optimizer was approximately 35% higher than that of the SGD optimizer; however, in the validation set, this difference was only 12%.

The respective ability to minimize the loss functions was also reflected in the predictive accuracy of the three models.

Figure 5 illustrates the development of the mAP_0.5 metric across the 100 epochs. It was evident that the mAP_0.5 for the SGD optimizer experienced an exponential increase in the first 40 epochs. On the other hand, a linear progression was noticeable for the AdamW optimizer. The final mAP_0.5 for the AdamW optimizer was approximately two percentage points lower than the SGD model (97.6% vs. 95.8%). Using the Adam optimizer only achieved a mAP_0.5 value of 67.8%. A similar ranking of the three models was also evident in the mAP_0.5:0.95 metric.

A look at

Table 1 reveals that the Adam optimizer had difficulties in accurately predicting both quay walls and piles. Particularly in the detection of quay walls, a significant performance difference was noticeable: the model only achieved a mean average precision of 20.4 percent.

The use of the Adam optimizer not only leads to the model’s unreliable localization of the harbor objects but also decreases the model’s classification accuracy. The classification loss in the training set, unlike the other two models, is least efficiently minimized with the Adam optimizer. While the model using the Adam optimizer also reaches the highest final loss value in this regard, the gaps between the three models are notably smaller compared to the box loss.

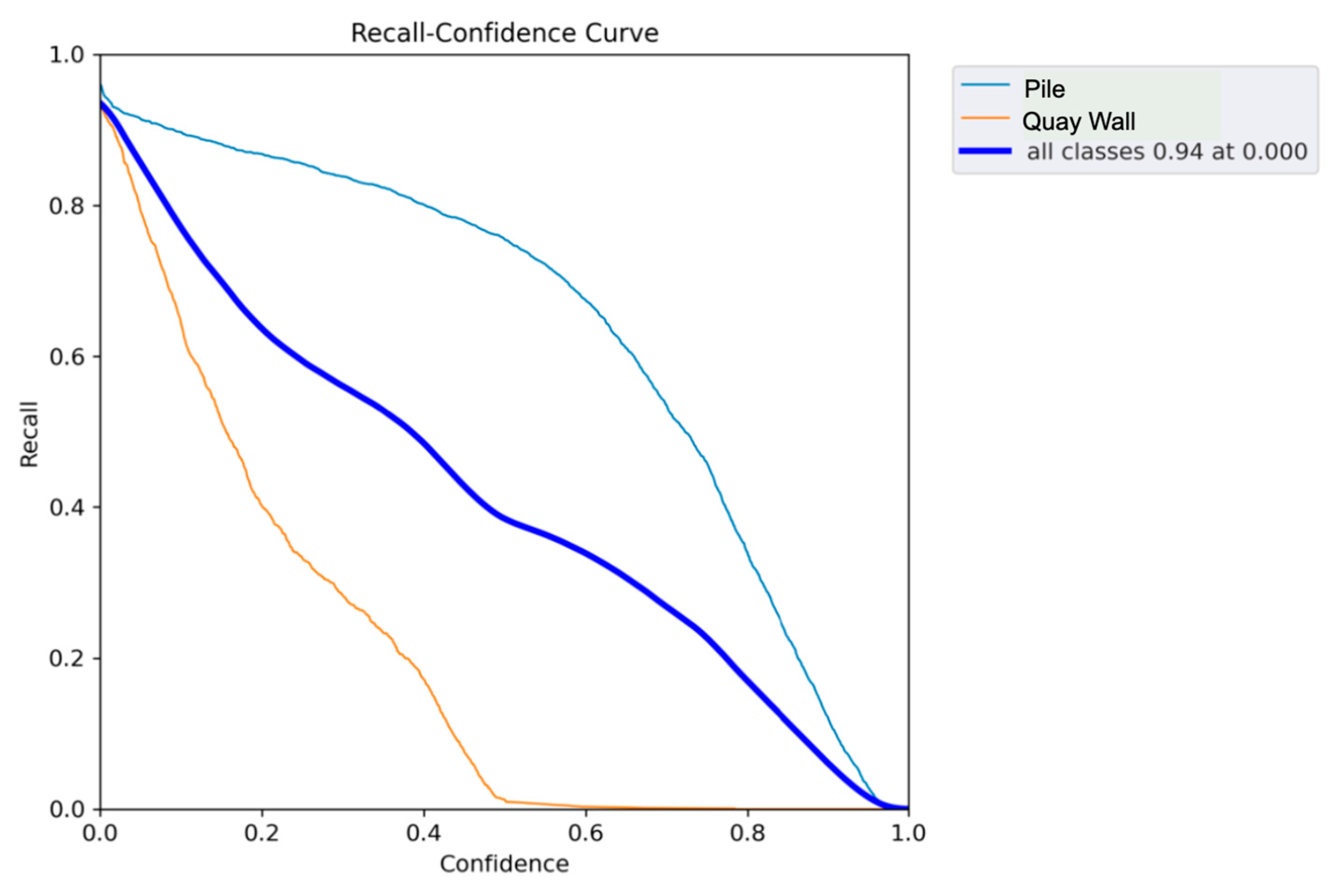

In summary, it can be concluded that the use of the Adam optimizer in the current application leads to inaccurate and flawed predictions, especially at high IoU thresholds. Additionally, the model is incapable of minimizing the box and classification losses as rapidly and effectively as achieved by using the AdamW or SGD optimizers. An examination of the performance metrics reveals that the Adam optimizer particularly struggles to achieve a high recall (see

Figure 6). After 100 epochs, the model attains a final recall value of only 59.8%, whereas the SGD optimizer achieves a recall of 94.1%.

As depicted in

Figure 6, the recall stagnates within the confidence range of 50 to 100 percent. This observation arises from the fact that the model fails to reliably localize many quay wall objects within that range. Due to generating a high number of false negatives, the recall could not be increased further in this confidence range (Recall = TP/TP + FN). In essence, the model overlooks numerous quay wall objects for which ground truth bounding boxes exist.

In comparison to the other optimization algorithms, the SGD optimizer proved to be the most effective in improving the efficiency of the gradient descent algorithm in the current application. It ensured a swift and sustainable minimization of the loss functions. Particularly in the reduction in the box loss, the SGD optimizer outperformed the other two algorithms. Consequently, the SGD model achieved the highest mean average precision values. Since the choice of optimization algorithm had no additional impact on the required training resources and the predictive accuracy of the models, the decision was made to use the SGD optimizer with Nesterov momentum for the subsequent experiments.

4.2. Evolutionary Optimization

Up to this point, only the default configuration provided by YOLOv5 for the instantiation of the secondary hyperparameters has been utilized. In the context of this experiment, the integrated genetic algorithm within the YOLOv5 repository was employed to automatically determine an optimal hyperparameter combination.

The current YOLOv5 model involves a total of 29 adjustable secondary hyperparameters. The model employs an initial (l0) and final learning rate (lf) to control the strength of weight adjustments over time. Additional secondary hyperparameters encompass the duration of the warm-up phase, the strength of the used momentum and warm-up momentum, the warm-up learning rate, the IoU threshold applied for training, the weight decay, and the weighting factors for the loss functions.

The evolutionary algorithm was configured to train the model for ten epochs each. After every ten epochs, the model’s predictive accuracy was evaluated. The genetic algorithm ran for a total of 100 epochs. Hence, the hyperparameter optimization process took up 1000 epochs (100 generations × 10 epochs per generation). The creation of a new offspring proceeded by selecting a specific solution from the top n solution candidates across all previous generations. In the initial generation, there was only one solution candidate—the default hyperparameter configuration. Over time, more hyperparameter combinations were generated. The algorithm dictated that during parent selection, at most the top five solutions could be considered. Each of these maximum five solution candidates was assigned a weight. Solutions with higher fitness values were given more weight than those with lower fitness values. These weights were subsequently utilized to select a concrete offspring for the current generation from the best n solutions. The weighting of candidates ensured that solutions with high fitness were preferred choices [

32].

The hyperparameters of the determined offspring were subsequently mutated component-wise. The probability of a hyperparameter being altered was set at 80 percent. The Gaussian mutation operator was employed for the mutation process. In this mutation operator, an initial random value was drawn from a normal distribution (variance = 0, mean = 1) [

33]. This value was then multiplied by the so-called mutation rate, which controls the strength of the mutation [

33]. In this scenario, the mutation rate was 0.2. The resulting value represented the actual mutation factor, which was applied to the corresponding hyperparameter [

32]. Subsequently, the performance of the generated solution was evaluated through a fitness function. The fitness function calculated the weighted sum of the two performance metrics, mAP_0.5 (weight = 10%) and mAP_0.5:0.95 (weight = 90%) [

32].

The most effective hyperparameter configuration was discovered after 78 generations. This candidate achieved the highest mAP_0.5 value of 93.3 percent in the first ten epochs. The hyperparameter optimization has resulted in the model being better equipped to minimize the box loss. This implies that the model achieves improved results more rapidly when adapting to the training dataset and previously unseen input images. Even the box loss achieved after 100 epochs is lower. For the training set, this value was reduced to 0.0127 after optimization, whereas it was almost double at 0.0228 before. In the validation set, the box loss after 100 epochs was reduced by almost 45 percent through hyperparameter optimization. Similar trends are evident in the classification loss in the validation set. The final classification loss was reduced from 0.0001837 to 0.00005904 (−68 percent) through the adjusted hyperparameters. However, the adaptability to training images could hardly be improved.

It is notable that precision, recall, and mAP metrics can be improved in less time through the adjustment of hyperparameters. The original model with the default hyperparameter configuration required more epochs initially to achieve similar high-performance values. Additionally, it is evident that the performance values of the two models gradually converge, and, after 100 epochs, there was no significant difference in mean average precision measurable anymore. The enhancement in efficiency in minimizing the loss functions was attributed to the adaptation of hyperparameters within the framework of evolutionary optimization (see

Table 2).

On the one hand, the warm-up phase was reduced from 3 to 1.87 epochs. By decreasing the initial learning rate from 0.01 to 0.00746, the momentum from 0.937 to 0.853, and the warm-up momentum, the likelihood of the model skipping valleys in the loss function at the beginning of the learning process decreased. It seems that without the adjusted hyperparameters, the model might have become stuck in a less optimal minimum after a certain point, as opposed to the optimized model. This is why the final loss scores of the two models—particularly the box loss—differ after 100 epochs.

In summary, it can be concluded that the optimization of the secondary hyperparameters aided in improving the YOLO model’s adaptation to training images and previously unseen data. While the hyperparameter optimization did not lead to an enhancement in the final model performance, it did bring about an efficiency improvement in the training process. The model is now capable of sustaining a stronger minimization of the loss functions and achieving quicker increases in precision, recall, and mean average precision in the initial epochs. The convergence of final mean average precision values can be attributed to the differing weightings of the loss functions (box loss: 0.05 (before) vs. 0.0279 (after); class loss: 0.5 (before) vs. 0.261 (after)).

4.3. Final Model

The final model utilizes the optimal settings for hyperparameters determined within the scope of the four experiments (image resolution: [1280 × 720], batch size: 64, optimization algorithm: SGD with Nesterov momentum, and the optimized hyperparameters). The implementation of early stopping led to the premature termination of training after 306 epochs.

Table 3 presents the mean average precision (mAP) values and inference time of the final model.

It is evident that the model’s prediction accuracy in detecting the quay walls is higher in both the mAP_0.5 and mAP_0.5:0.95 metrics compared to detecting the piles. While the performance difference in class-specific mAP_0.5 is merely one percentage point, it amounts to 6.6 percentage points in the mAP_0.5:0.95 metric. This observation has been consistent throughout the preceding experiments. The size of the objects can be attributed as a reason for this performance difference. Piles are generally smaller than quay wall objects. Due to the functioning of the YOLO architecture, instances of imprecise localization of such objects are more frequent [

34,

35]. This issue becomes more pronounced, especially when higher Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds are applied.

The final model achieves a prediction accuracy (mAP_0.5) of 97.7 percent while having a low inference time of 7.7 milliseconds per image, enabling the final model to process approximately 130 frames per second (FPS). This allows the model to be used in a real-time context, like early warning and navigation systems.

As outlined in

Section 3, an investigation was conducted to determine whether the implemented model in this study could be utilized for the automated detection of quay walls and piles in different port areas. For this purpose, a total of 30 images was collected from the internet, depicting quay walls and piles in other port areas. Subsequently, the final YOLO model was employed to make predictions on these previously unseen images. The evaluation of the results revealed that the model’s performance can only be transferred to other use cases to a very limited extent. On 14 out of the 30 images, the quay walls and piles were not detected at all due to their differing appearance (e.g., color or shape).

5. Summary and Conclusions

Within the scope of this study, it has been demonstrated that the automated detection of static harbor objects within port areas has not been sufficiently investigated thus far. Current research and commercially available solutions predominantly focus on ship detection. To address this research gap, the central research question of this study aimed to be answered: How can static harbor objects be automatically identified in camera images?

During the hyperparameter optimization process, noteworthy observations were made. Specifically, the reliability in detecting smaller objects like piles could be enhanced by increasing the input image resolution. Furthermore, employing a native image resolution of [1280 × 720] offers the advantage of directly processing images in operational use without requiring an additional preprocessing step, leading to improved model prediction speed. In the context of the second experiment, it was evident that a higher batch size correlated with improved model accuracy and reduced training duration. However, this also demands more memory space. The third experiment revealed that the “stochastic gradient descent with momentum” algorithm is best suited for detecting static harbor objects in the given application. In the final step, the remaining secondary hyperparameters of the model were fine-tuned using a genetic algorithm. This hyperparameter optimization facilitated a more sustainable minimization of loss functions, particularly the box loss, resulting in a model that better adapts to the underlying images.

It is important to note that the optimal hyperparameter configuration derived from these experiments may not be universally transferable to other use cases. The suitability of this hyperparameter combination for the current application does not guarantee optimal outcomes for all other scenarios (No Free Lunch theorem) [

28]. This especially holds true for the employed optimization algorithm and the determined secondary hyperparameters.

The evaluation of the final model’s performance revealed that all specified functional mandatory requirements were successfully met. Both performance-related requirements regarding the achieved prediction accuracy (mAP_0.5 ≥ 95%) and speed (≥30 FPS) of the model were surpassed. However, it was also demonstrated that the performance of the implemented model cannot be readily transferred to other port areas. The reason for this is that the appearance of harbor objects varies significantly from one port area to another, differing from the quay walls and piles in the port of Emden. As a result, the model fails to recognize these objects in the unseen images. The model’s predictions made in these cases are largely inaccurate and erroneous.

Although the model implemented in this study is not suitable for detecting static harbor objects in other port areas, the conceptual framework developed in this study can still serve as a guide for undertaking appropriate measures when building a custom dataset and implementing an individual YOLOv5s6 model. The outlined steps for data preprocessing, dataset labeling, and data augmentation can be readily applied to the detection of various static harbor objects in different port areas, if necessary, with minimal adjustments. The recommended practices for setting image resolution and batch size also hold universal applicability. In such cases, only the underlying training images need to be substituted. Moreover, the dataset created as part of this work provides a foundational resource to propel further research in the realm of static harbor object detection.

In conclusion, it can be affirmed that the formulated research question has been successfully addressed. Through the evaluation of model performance, it has been demonstrated that the deployed YOLOv5 model is capable of making reliable and swift predictions, effectively adapting to the specific challenges within the maritime domain.