Assessing the Environmental Impact of Deep-Sea Mining Plumes: A Study on the Influence of Particle Size on Dispersion and Settlement Using CFD and Experiments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

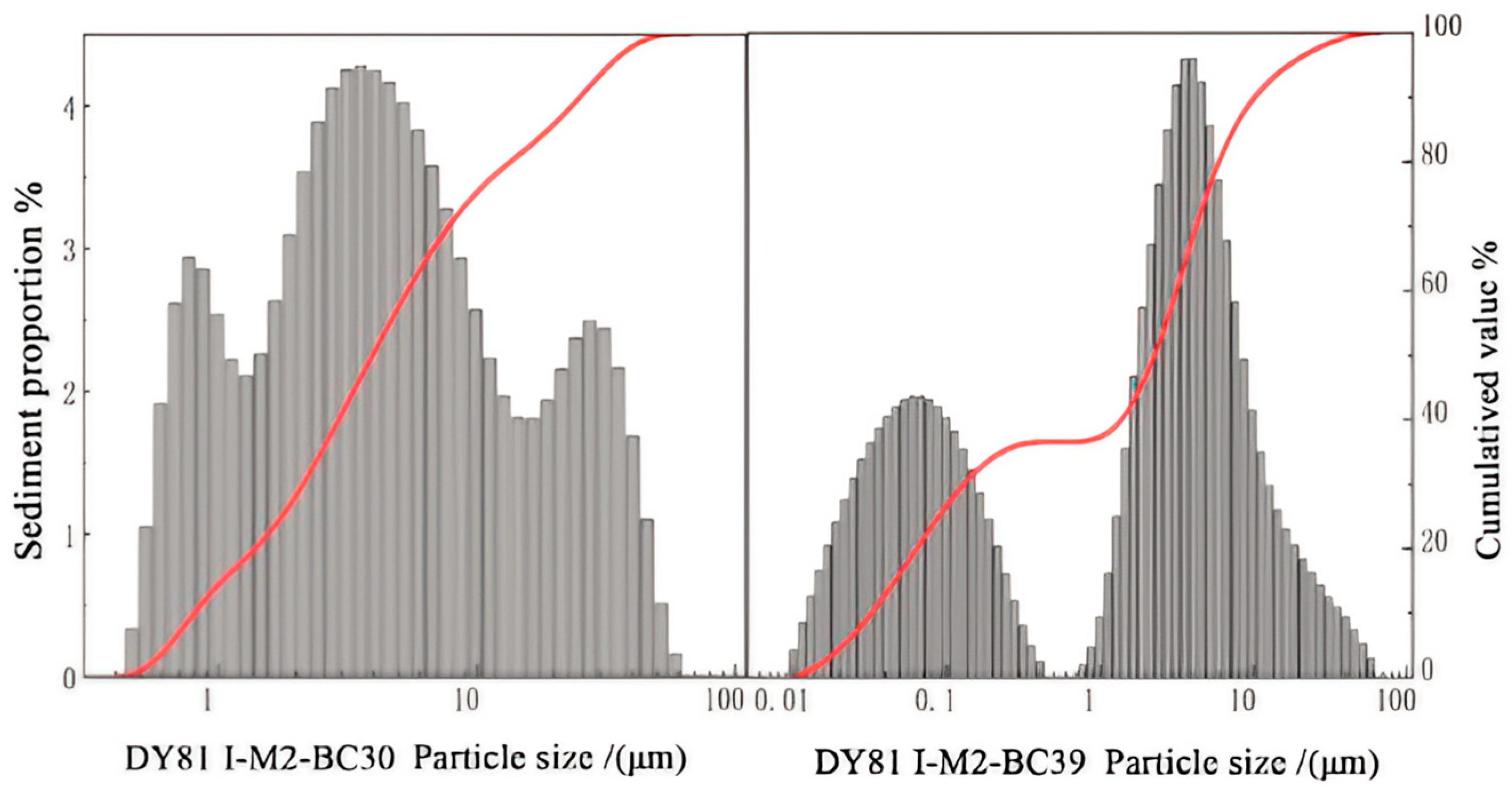

2.1. Sediment Physical Properties

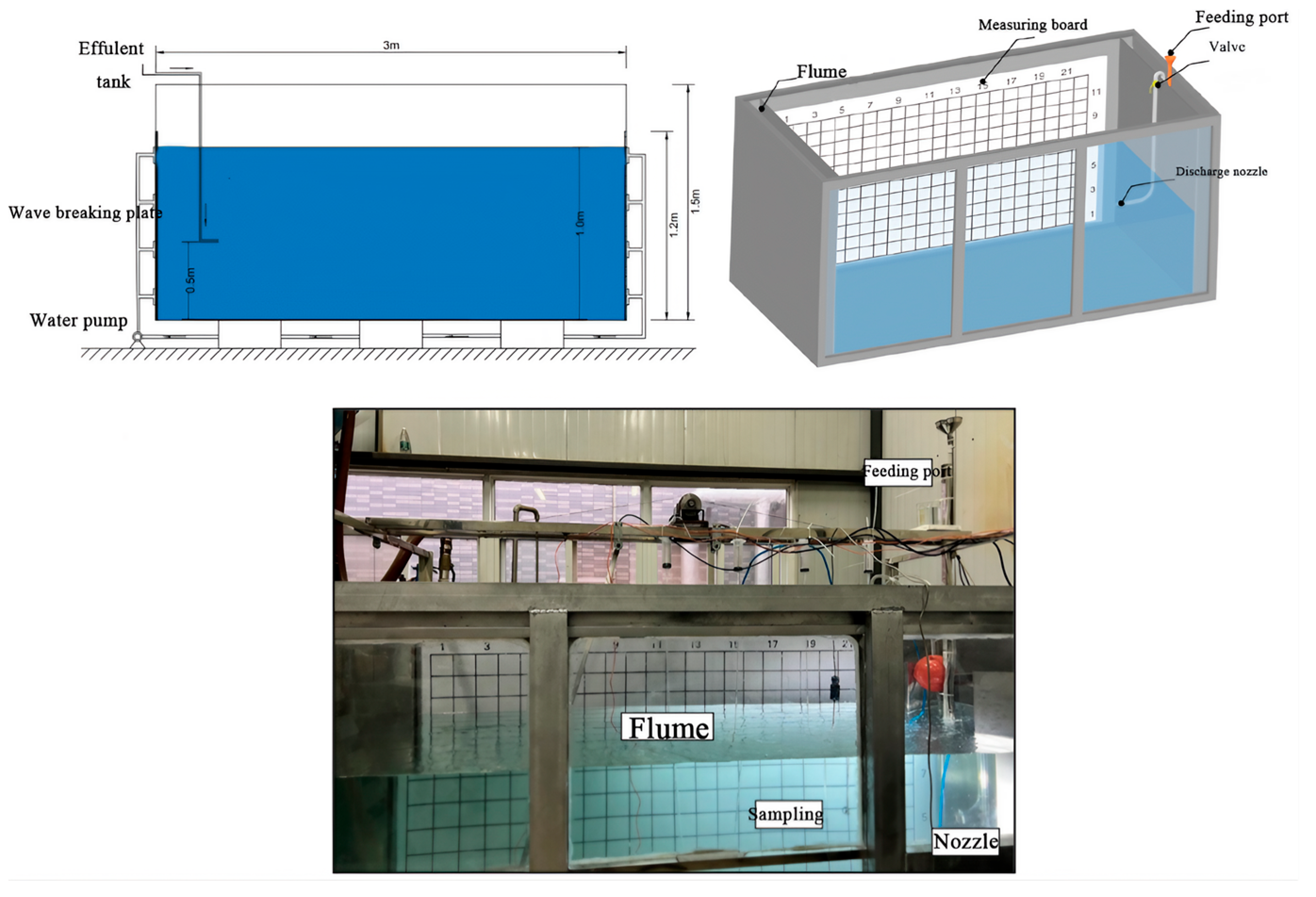

2.2. Experimental Setup

2.3. Sampling and Data Processing

3. Numerical Models

3.1. Model Equation

3.2. Model Validation

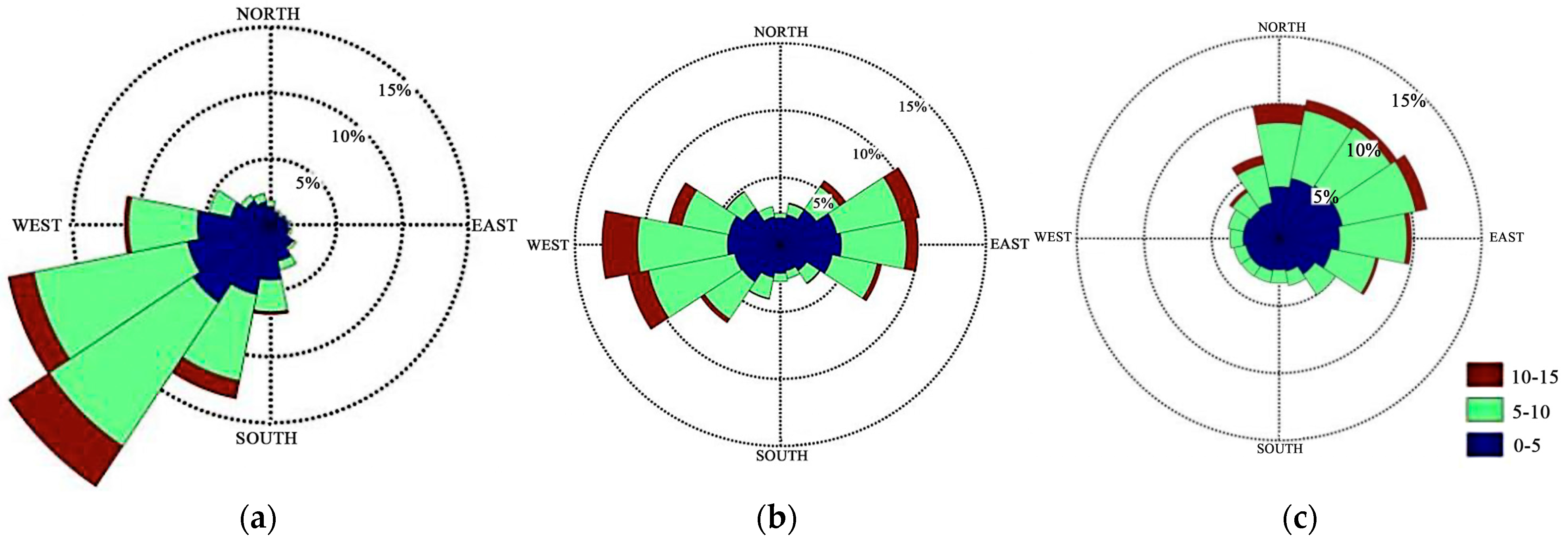

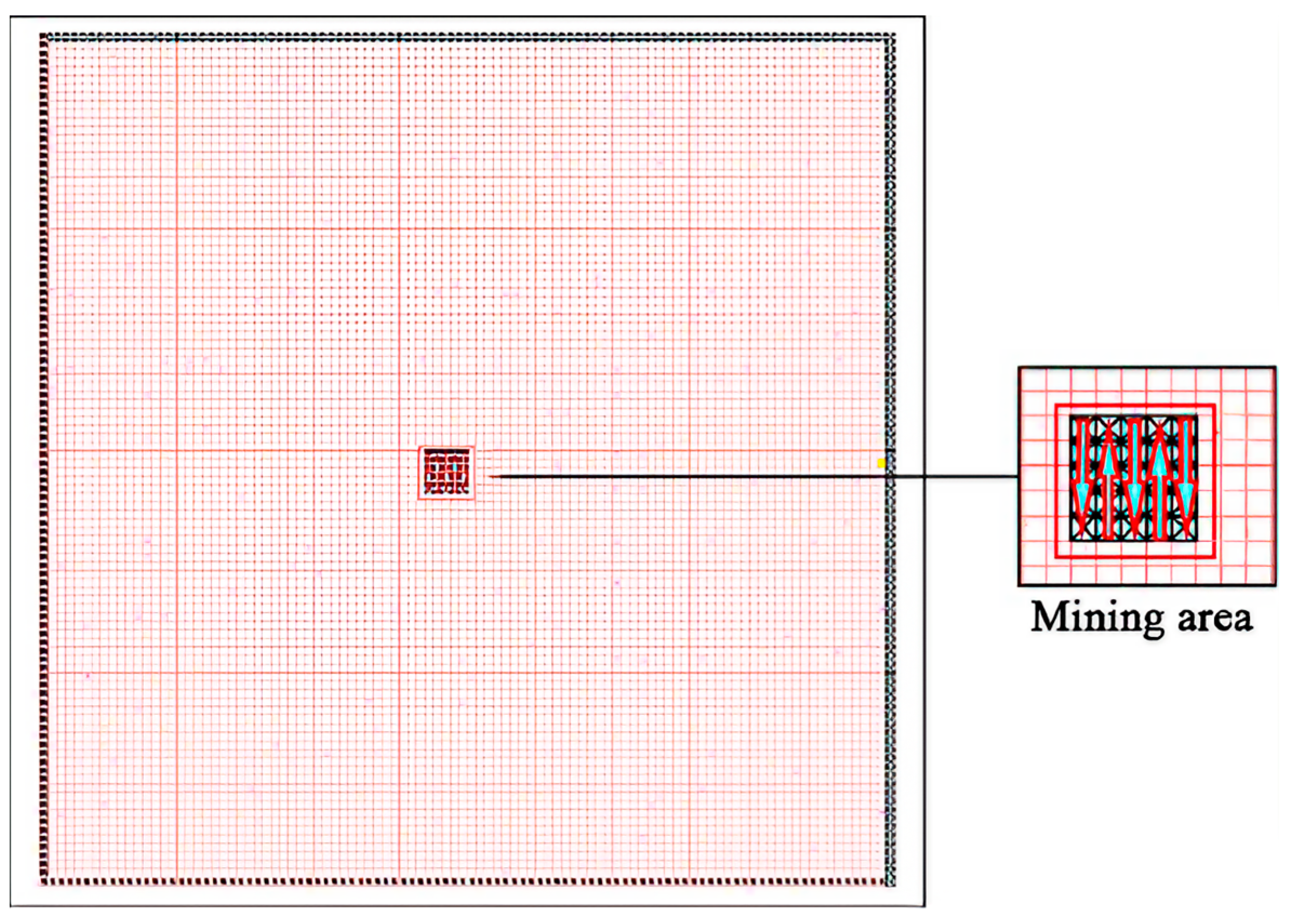

3.3. Field Simulation and Boundary Conditions

4. Results and Discussion

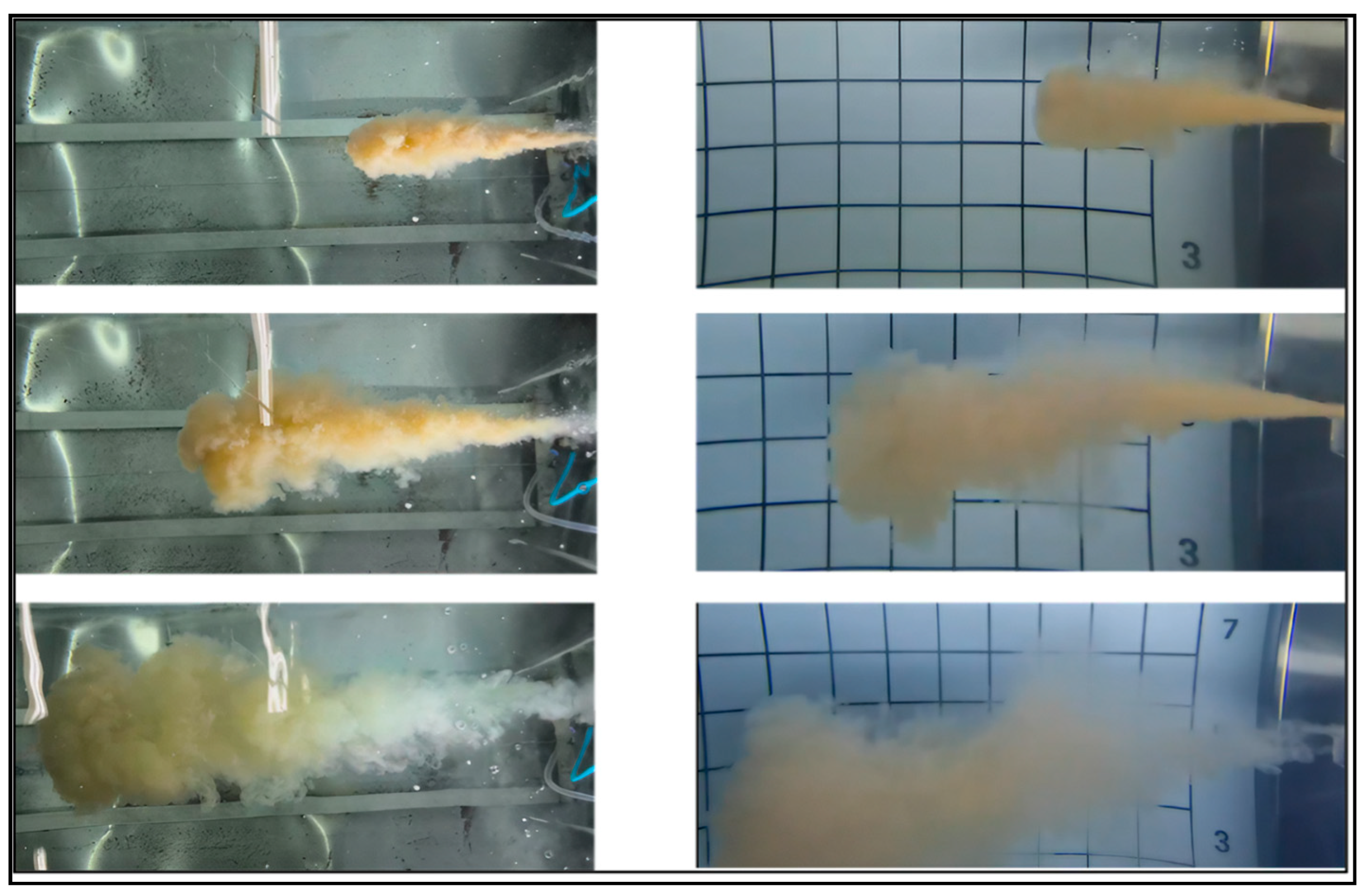

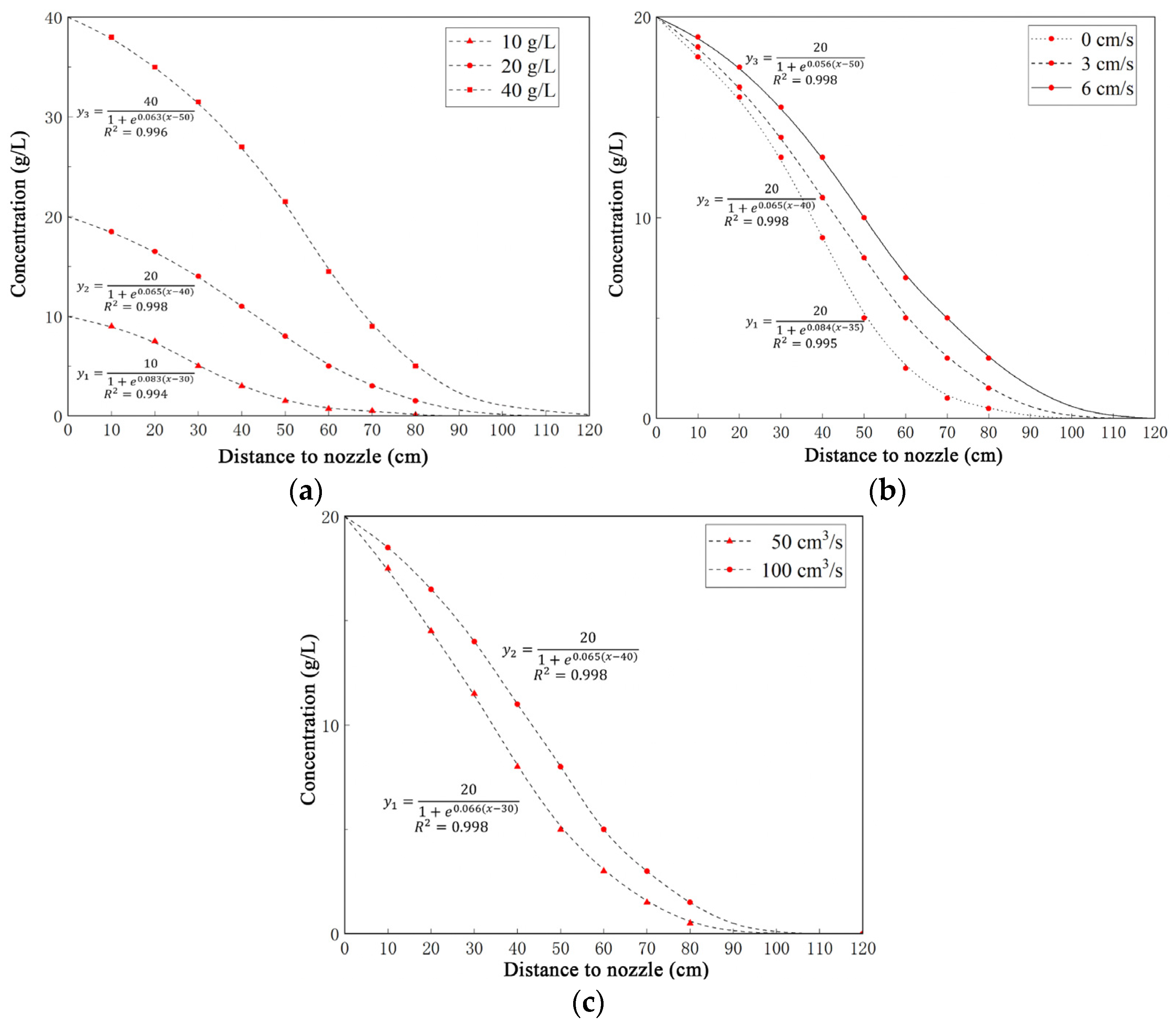

4.1. Comparison with Experiment

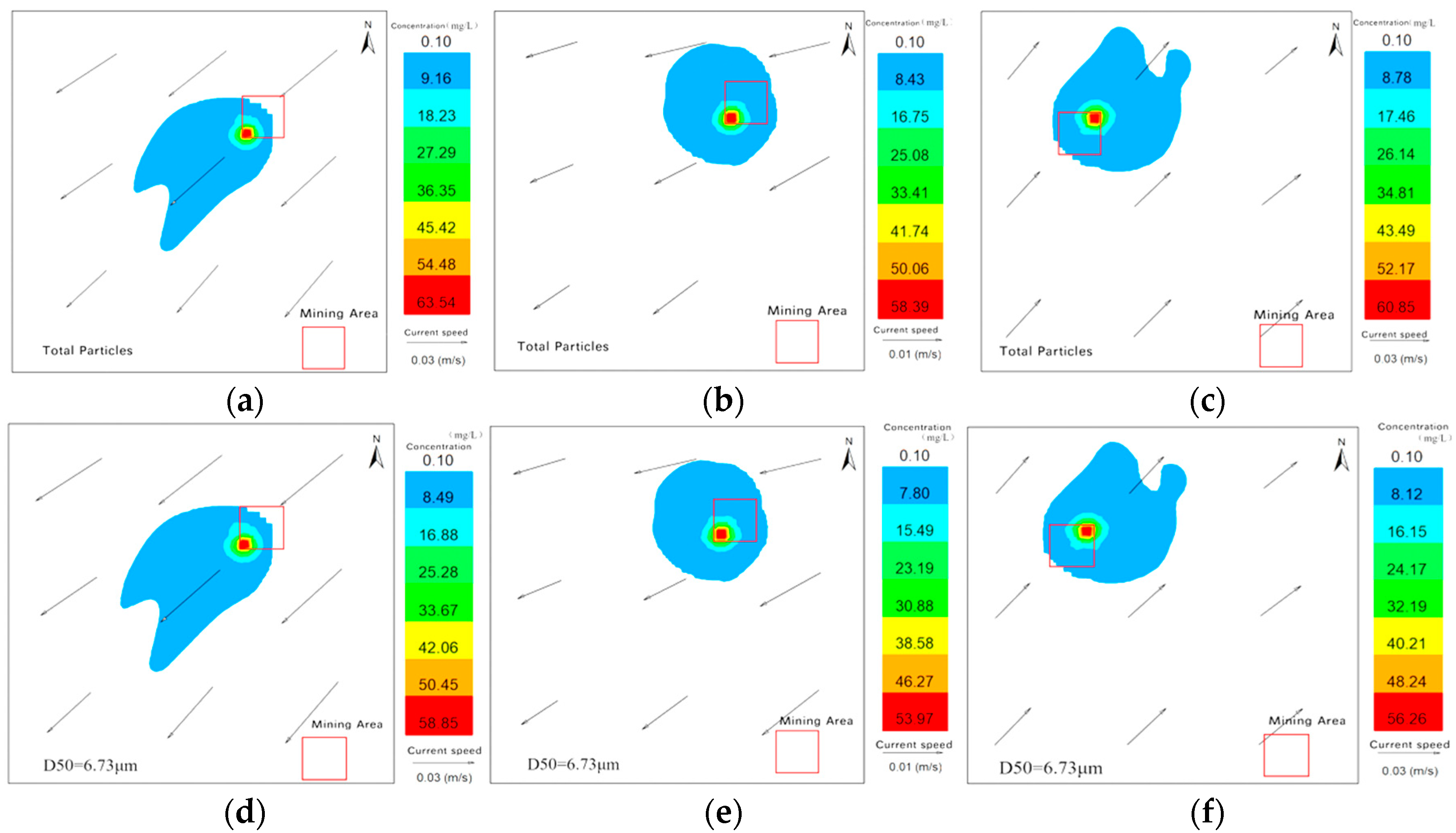

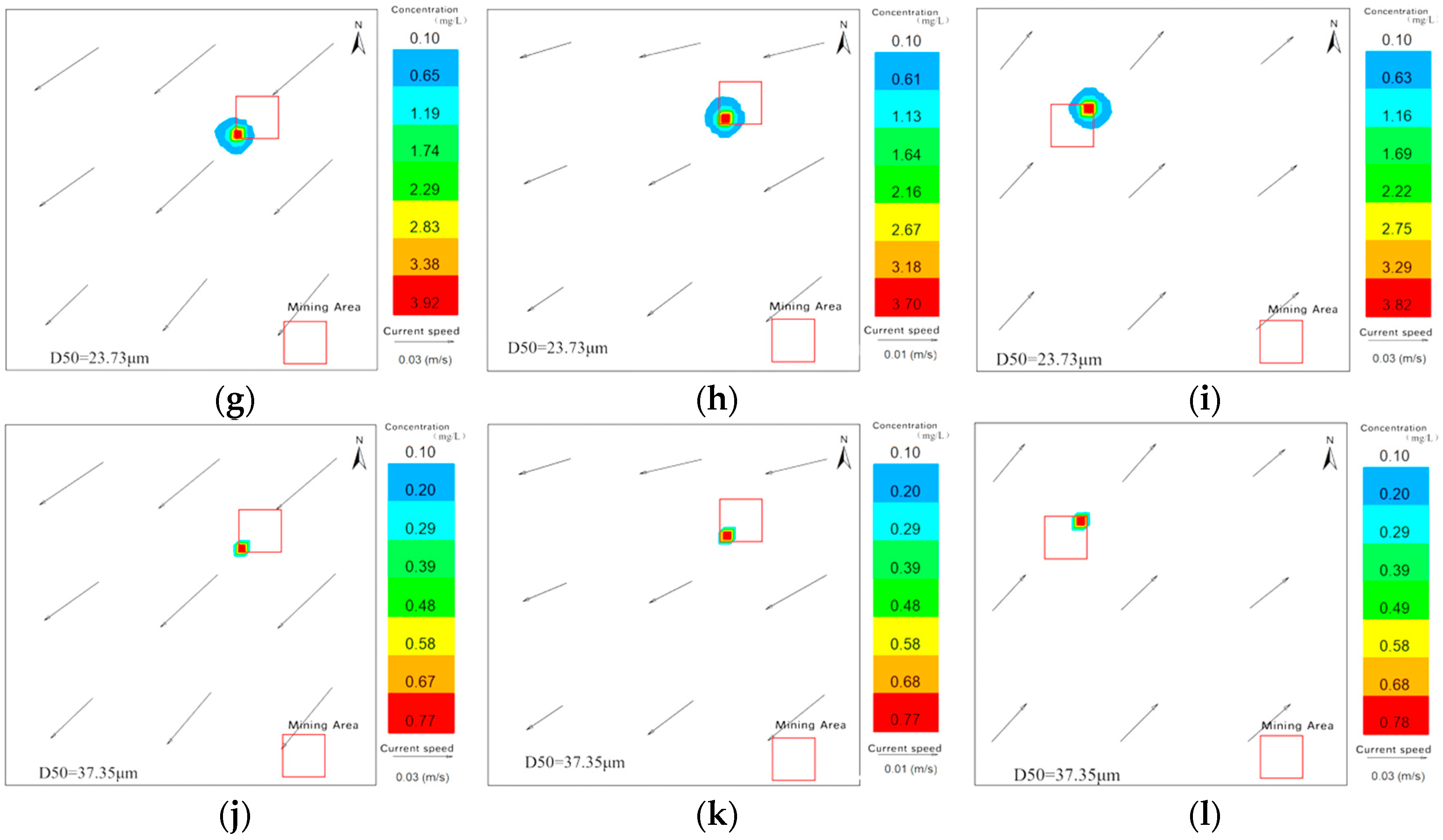

4.2. Field Simulation Results

4.3. Implications for Environmental Thresholds

5. Conclusions

- Sediments in the western Pacific are primarily composed of cohesive particles with sizes mostly ranging from 0 to 66.89 μm, a median size below 5 μm, and over 90% cohesive particles. The particle size distribution shows both bimodal and unimodal patterns. Sedimentation experiments calculated particle settling velocities ranging from 0.06 to 8.33 mm/s. Analysis revealed that during the first 0–14 min of settling, larger particles (30–66.9 μm) dominate the sediment, settling due to gravity. Smaller particles tend to aggregate via flocculation, forming larger flocs with higher settling velocities.

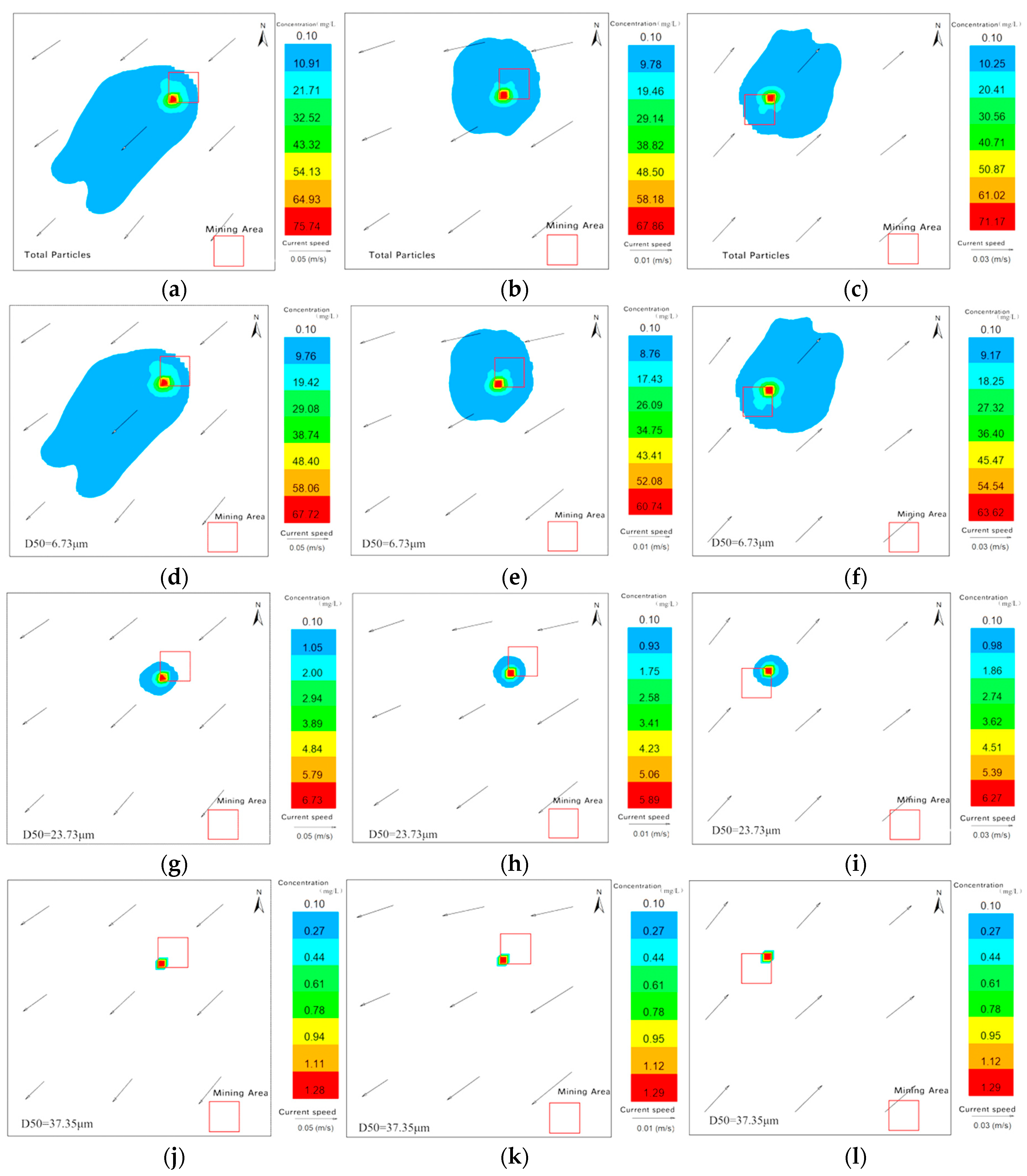

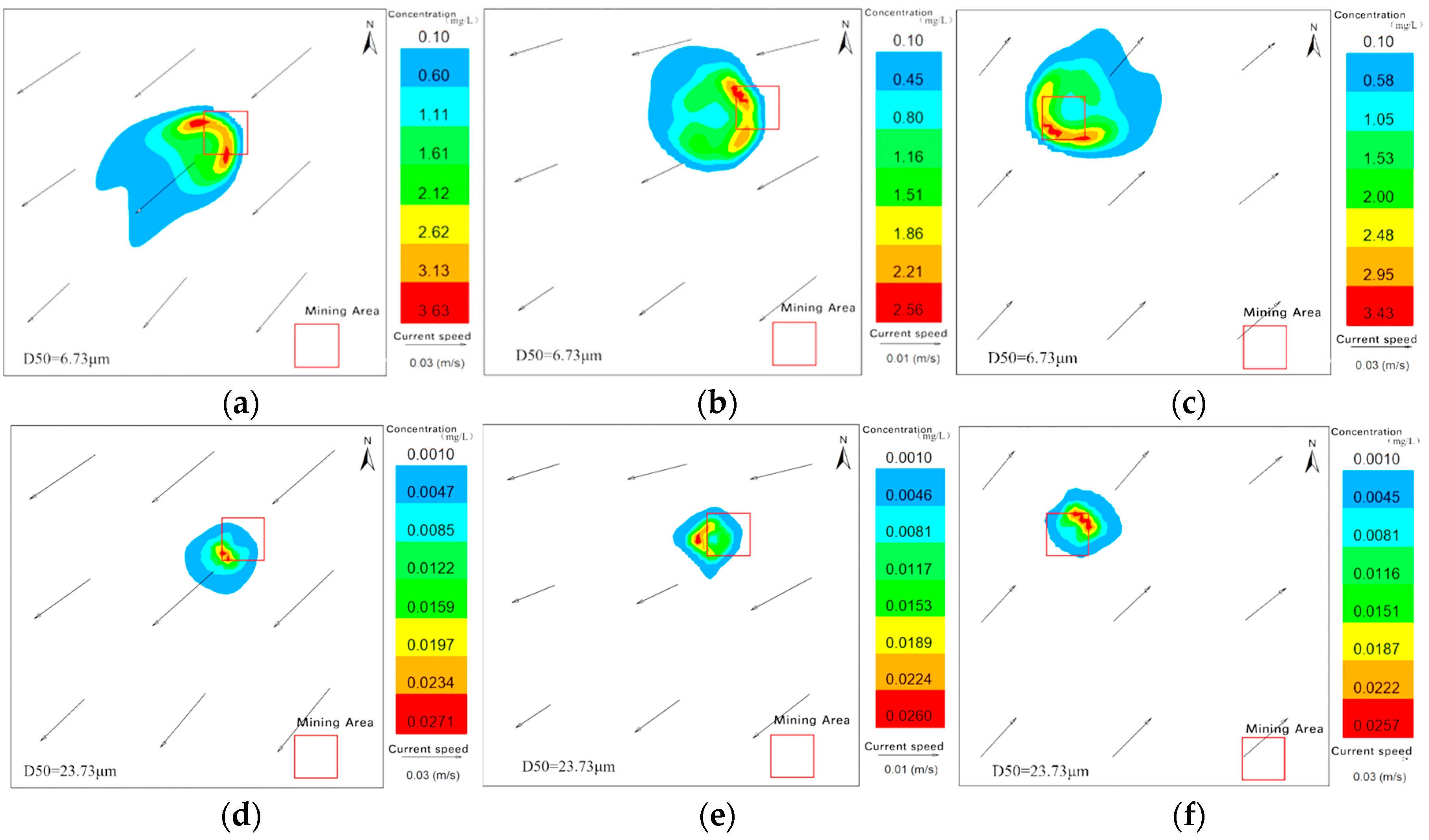

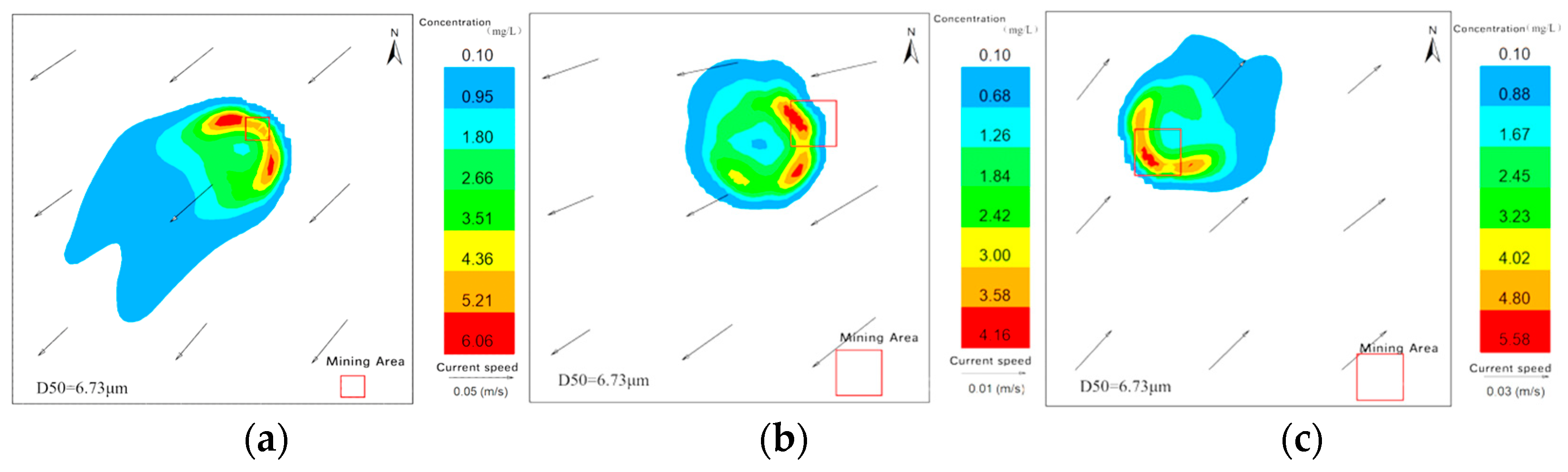

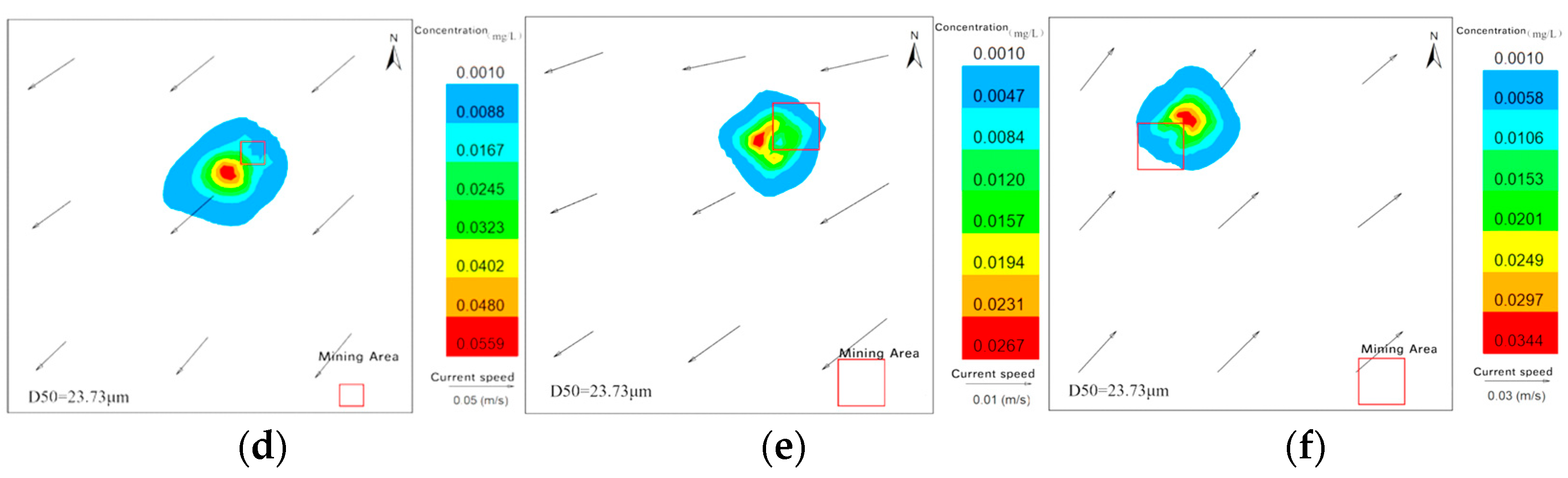

- During deep-sea nodule collection experiments, sediment was categorized into three groups based on median particle size (D50): cohesive sediments with 1 μm < D50 < 8 μm (80%), 8 μm < D50 < 32 μm (10%), and non-cohesive sediments with D50 > 32 μm (10%). Corresponding discharge source strengths (Q1, Q2, Q3) were calculated as 46.74 kg/s, 5.84 kg/s, and 5.84 kg/s, respectively. Experimental observations showed that the maximum diffusion area of the sediment plume reached 3.8 km2 under six tested scenarios; approximately three days after the discharge ceased, the plume had nearly dissipated completely. An increase in current velocity led to an expansion of the plume’s diffusion range, while simultaneously reducing the plume’s maximum concentration. Additionally, higher current velocity increased the area where the sediment resettlement thickness exceeded 1 mm, but decreased the overall resettlement thickness in those areas. A greater discharge height contributed to a higher average current speed in the surrounding water and prolonged the sediment settling time. This, in turn, expanded the total sediment resettlement area, though it also resulted in a reduction in the maximum resettlement thickness.

- After continuous plume discharge for 3 days, using 0.1 mg/L as the background concentration, the maximum plume diffusion distance exceeded 2.4 km with an area over 3 km2. The plume disappeared 3 days after the experiment ended. The area with resettlement thickness greater than 1 mm ranged from 0.261 to 0.282 km2, slightly larger than the experimental area (0.25 km2), indicating that the 1 mm thick resettlement was mostly confined near the test site.

- Based on simulation results, continuous deep-sea nodule collection over 3 days generates plume concentrations and resettlement thicknesses from suspended collector discharge that impact the deep-sea environment. Mining under the condition of 4 m discharge height and an average current velocity of 1.21 cm/s results in the least environmental impact.

- The plume’s migration, diffusion, and resettlement during deep-sea nodule collection pose potential environmental impacts. Under varying current speeds and discharge heights, near-bottom maximum plume concentrations ranged from 58.39 to 75.74 mg/L with diffusion areas between 1.69 km2 and 3.80 km2. After 3 days, concentrations dropped to 0.23–0.49 mg/L across six scenarios, with affected areas from 0.53 km2 to 2.41 km2. Maximum resettlement thicknesses ranged from 2.7 to 3.4 cm. Prolonged mining activities may cause sustained low-level plume concentrations and sediment resettlement over large areas, increasing impact range and severity—such as wider plume dispersion and resettlement thickness exceeding 5 cm—posing potential risks to marine ecosystems during months-long commercial mining.

- The scope of this study being limited to particle size effects in plume simulation, various other influencing factors were not elaborated. Despite the insights provided, this study has several limitations. The numerical model neglects small-scale turbulence interactions, which may affect the accuracy of simulated sediment plume diffusion in the near field. Moreover, considering the current measurement accuracy of experimental equipment for mass concentration, the observation duration of the physical experiment is relatively limited and therefore insufficient to capture the plume’s motion throughout its entire life cycle. Future research will systematically address flocculation impacts on plume dispersion and develop methodologies for characterizing sediment particle size distribution and determining critical parameters like settling velocity. At the same time, new technologies will be introduced into the experiments to enable more accurate measurements of plume dynamics for the low-concentration samples.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, D.O.; Simon-Lledó, E.; Amon, D.J.; Bett, B.J.; Caulle, C.; Clement, L.; Huvenne, V.A. Environment, ecology, and potential effectiveness of an area protected from deep-sea mining (Clarion Clipperton Zone, abyssal Pacific). Prog. Oceanogr. 2021, 197, 102653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, K. Numerical simulation and analysis of initial plume discharge of deep-sea mining. Ocean Eng. 2024, 310, 118794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, J. A modified drag coefficient model for calculating the terminal settling velocity and horizontal diffusion distance of irregular plume particles in deep-sea mining. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 33848–33866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, T.; Ouillon, R. The fluid mechanics of deep-sea mining. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2023, 55, 403–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapil, M.; Sutherland, B.R.; Balasubramanian, S. Sediment characterization of bottom propagating reversing buoyancy particle-bearing jets. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2022, 7, 104302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillard, B.; Purkiani, K.; Chatzievangelou, D.; Vink, A.; Iversen, M.H.; Thomsen, L. Physical and hydrodynamic properties of deep sea mining-generated, abyssal sediment plumes in the Clarion Clipperton Fracture Zone (eastern-central Pacific). Elem. Sci. Anth. 2019, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, B.R.; Middleton, J. Scale diagrams for forced plumes. J. Fluid Mech. 1973, 58, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, W.N.; Hess, W.C. An Advection-Diffusion Model of the DOMES Turbidity Plumes; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Environmental Research Laboratory, U.S. Department Commerce: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 1976; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern, D. Upper ocean circulation studies in the eastern tropical North Pacific during September and October 1975. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 5–8 May 1976. OTC-2457-MS. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski, J.A.; Malcherek, A.; Zielke, W. Numerical modeling of sediment transport processes caused by deep sea mining discharges. In Proceedings of the OCEANS’94, Brest, France, 13–16 September 1994; Volume 3, pp. III/269–III/277. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski, J.A.; Malcherek, A.; Zielke, W. Numerical modeling of suspended sediment due to deep-sea mining. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 1996, 101, 3545–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, H. Near-bottom currents in the deep Peru Basin, DISCOL experimental area. Dtsch. Hydrogr. Z. 1993, 45, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, K.; Nakata, K.; Aoki, S.; Kubota, M. Environmental study on the deep-sea mining of manganese nodules in the Northeastern Tropical Pacific. In Proceedings of the ISOPE Ocean Mining and Gas Hydrates Symposium, Tsukuba, Japan, 21–22 November 1995. Paper ISOPE-M-95-025. [Google Scholar]

- Doi, T.; Nakata, K.; Kubota, M.; Aoki, S. Environmental study on the deep-sea mining of manganese nodules in the Northeastern Tropical Pacific—Modeling the sediment-laden negative buoyant flow. In Proceedings of the ISOPE Ocean Mining and Gas Hydrates Symposium, Goa, India, 8–10 November 1999. Paper ISOPE-M-99-025. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski, A.J.; Zielke, W. The mesoscale sediment transport due to technical activities in the deep sea. Deep-Sea Res. Part II 2001, 48, 3487–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouillon, R.; Kakoutas, C.; Meiburg, E.; Peacock, T. Gravity currents from moving sources. J. Fluid Mech. 2021, 924, A43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, G.; Tunstall, R. CFD validation of buoyancy driven jet spreading, mixing and wall interaction. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2020, 365, 110703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Royo, C.; Peacock, T.; Alford, M.H.; Smith, J.A.; Le Boyer, A.; Kulkarni, C.S.; Ju, S.J. Extent of impact of deep-sea nodule mining midwater plumes is influenced by sediment loading, turbulence and thresholds. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elerian, M.; Huang, Z.; van Rhee, C.; Helmons, R. Flocculation effect on turbidity flows generated by deep-sea mining: A numerical study. Ocean Eng. 2023, 277, 114250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Smirren, J.; Banks, A.; Foster, T.; Clarke, M.; Marsh, L.; Allen, K. Observing Deep Water Sediment Plumes Using Mobile and Seabed Deployed Instrumentation. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 6–9 May 2024. Paper D021S023R006. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, W.; Lu, H.; Bai, T.; Zou, L. Research on numerical simulation of initial process of sediment discharge from deep-sea mining vehicle. Ocean Eng. 2025, 327, 120973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousadik, S.E.; Ouillon, R.; Muñoz-Royo, C.; Slade, W.; Pottsmith, C.; Leeuw, T.; Peacock, T. In Situ Optical Measurement of Particles in Sediment Plumes Generated by a Pre-Prototype Polymetallic Nodule Collector. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Weng, Z.; Guo, J.; Lin, X.; Phan-Thien, N.; Zhang, J. Simulation Study on the Sediment Dispersion during Deep-Sea Nodule Harvesting. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.Q.; Zhao, Y.; Bai, T.B.; Huang, K. Study on the inhibitory effect of stern deflector on the diffusion of tail plume of deep-sea mining collector. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 43, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Yang, J.; Lu, H.; Lin, Z.; Sun, P.; Zhang, B. Numerical and experimental investigation of the coupling effect of double plume discharge sources in deep-sea mining. Ocean Eng. 2025, 337, 121861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, J.; Taylor, J.; Crossouard, N.; Cooper, A.; Turnbull, M.; Manning, A.; Lee, M.; Murton, B. Measurement and modelling of deep sea sediment plumes and implications for deep sea mining. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, F.F.; Zhang, J.; Jing, C.; Guo, X.; Wang, C. Modelling of sediment plumes generated by deep-sea mining in CCZ. J. Appl. Oceanogr. 2024, 43, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; He, Z.; Han, X. Transport and deposition patterns of particles laden by rising submarine hydrothermal plumes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL089935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, S.K.; Chauhan, P.S. Towards sustainable delta ecosystems: Pollution mitigation for achieving SDGs in Indian delta region. In Solid Waste Management in Delta Region for SDGs Fulfillment: Delta Sustainability by Waste Management; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, P.J.; Armitage, P.D. Biological effects of fine sediment in the lotic environment. Environ. Manag. 1997, 21, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, P.; Sear, D.; Collins, A.; Naden, P.; Jones, I. The impacts of fine sediment on riverine fish. Hydrol. Process. 2011, 25, 1800–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.I.; Murphy, J.F.; Collins, A.L.; Sear, D.A.; Naden, P.S.; Armitage, P.D. The impact of fine sediment on macro-invertebrates. River Res. Appl. 2012, 28, 1055–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extence, C.; Chadd, R.P.; England, J.; Dunbar, M.J.; Wood, P.J.; Taylor, E.D. The assessment of fine sediment accumulation in rivers using macro-invertebrate community response. River Res. Appl. 2013, 29, 17–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashtgard, S.E.; Gingras, M.K.; Pemberton, S.G. Grain-size controls on the occurrence of bioturbation. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2008, 257, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, M.G.D.; Holthaus, K.I.E.; Trannum, H.C.; Neff, J.M.; Kjeilen-Eilertsen, G.; Jak, R.G.; Hendriks, A.J. Species sensitivity distributions for suspended clays, sediment burial, and grain size change in the marine environment. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2008, 27, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, C.; Tjensvoll, I.; Sköld, M.; Allan, I.J.; Molvaer, J.; Magnusson, J.; Nilsson, H.C. Bottom trawling resuspends sediment and releases bioavailable contaminants in a polluted fjord. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 170, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, M.C.; Strehlow, B.; Kamp, J.; Duckworth, A.; Jones, R.; Webster, N.S. Effects of combined dredging-related stressors on sponges: A laboratory approach using realistic scenarios. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, M.; Oliveira, A.; Barros, S.; Alves, N.; Raimundo, J.; Caetano, M.; Santos, M.M. Functional, biochemical and molecular impact of sediment plumes from deep-sea mining on Mytilus galloprovincialis under hyperbaric conditions. Environ. Res. 2021, 195, 110753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, W.E.; Kirchner, J.W.; Ikeda, H.; Iseya, F. Sediment supply and the development of the coarse surface layer in gravel-bedded rivers. Nature 1989, 340, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahoon, L.B.; Nearhoof, J.E.; Tilton, C.L. Sediment grain size effect on benthic microalgal biomass in shallow aquatic ecosystems. Estuaries 1999, 22, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainbridge, Z.T.; Wolanski, E.; Álvarez-Romero, J.G.; Lewis, S.E.; Brodie, J.E. Fine sediment and nutrient dynamics related to particle size and floc formation in a Burdekin River flood plume, Australia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 65, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.O.; Kaiser, S.; Sweetman, A.K.; Smith, C.R.; Menot, L.; Vink, A.; Clark, M.R. Biological responses to disturbance from simulated deep-sea polymetallic nodule mining. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, L.K.; Pandey, M.; Raj, P.A.; Shukla, A.K. Fine sediment intrusion and its consequences for river ecosystems: A review. J. Hazard. Toxic Radioact. Waste 2023, 27, 04022036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazis, I.-Z.; de Stigter, H.; Mohrmann, J.; Heger, K.; Diaz, M.; Gillard, B.; Baeye, M.; Veloso-Alarcón, M.E.; Purkiani, K.; Haeckel, M.; et al. Monitoring benthic plumes, sediment redeposition and seafloor imprints caused by deep-sea polymetallic nodule mining. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.O.; Durden, J.M.; Murphy, K.; Gjerde, K.M.; Gebicka, A.; Colaço, A.; Billett, D.S. Existing environmental management approaches relevant to deep-sea mining. Mar. Policy 2019, 103, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulfsnes, A.; Haugland, J.K.; Weltzien, R. Monitoring of drilling activities in areas with presence of cold-water corals. Det Nor. Veritas 2012, 1691, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Offshore Norge. Species and Habitats of Environmental Concern, Mapping, Risk Assessment, Mitigation and Monitoring; The Norwegian Oil and Gas Association: Stavanger, Norway, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.; Schott, D.; van Rhee, C. Numerical calculations of environmental impacts for deep sea mining activities. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 652, 996–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitchin, B.; Smith, S.; Kröger, K.; Jones, D.; Jaeckel, A.; Mestre, N.; Ardron, J.; Escobar, E.; van der Grient, J.; Amaro, T. Thresholds in deep-seabed mining: A primer for their development. Mar. Policy 2023, 149, 105505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenvers, V.I.; Hauss, H.; Bayer, T.; Havermans, C.; Hentschel, U.; Schmittmann, L.; Sweetman, A.K.; Hoving, H.-J.T. Experimental mining plumes and ocean warming trigger stress in a deep pelagic jellyfish. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaikkonen, L.; Helle, I.; Kostamo, K.; Kuikka, S.; Törnroos, A.; Nygård, H.; Venesjärvi, R.; Uusitalo, L. Causal approach to determining the environmental risks of seabed mining. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 8502–8513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Time (min) | Settling Velocity in Still Water ω1/(mm/s) | Single Particle Settling Velocity ω2/(mm/s) | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 8.333 | 0.262 | 31.79 |

| 10 | 1.667 | 0.116 | 14.36 |

| 14 | 1.190 | 0.064 | 18.62 |

| 20 | 0.833 | 0.072 | 11.65 |

| 30 | 0.556 | 0.050 | 11.11 |

| 60 | 0.278 | 0.020 | 13.59 |

| 180 | 0.093 | 0.017 | 5.57 |

| Case No. | Discharge Concentration (g/L) | Discharge Flow Rate (cm3/s) | Ambient Velocity (cm/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 100 | 3 |

| 2 | 20 | 100 | 3 |

| 3 | 40 | 100 | 3 |

| 4 | 20 | 100 | 0 |

| 5 | 20 | 100 | 6 |

| 6 | 20 | 50 | 3 |

| Case No. | Discharge Height (m) | Eastward Component of Mean Current Velocity (m/s) | Northward Component of Mean Current Velocity (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | −0.0315 | −0.0248 |

| 2 | 4 | −0.012 | −0.006 |

| 3 | 4 | 0.0149 | 0.017 |

| 4 | 10 | −0.0315 | −0.0248 |

| 5 | 10 | −0.012 | −0.006 |

| 6 | 10 | 0.0149 | 0.017 |

| Case No. | Maximum Dispersion Distance at the Highest Concentration (km) | Maximum Concentration (mg/L) | Concentrations for Different Particle Size Categories (mg/L) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10 μm | 10–30 μm | >30 μm | |||

| 1 | 1.45 | 63.54 | 58.85 | 3.92 | 0.77 |

| 2 | 0.92 | 58.39 | 53.97 | 3.70 | 0.77 |

| 3 | 0.46 | 60.85 | 56.26 | 3.82 | 0.78 |

| 4 | 2.41 | 75.74 | 67.72 | 6.73 | 1.28 |

| 5 | 1.91 | 67.86 | 60.74 | 5.89 | 1.29 |

| 6 | 1.44 | 71.17 | 63.62 | 6.27 | 1.29 |

| Case No. | Area with Concentration > 0.1 mg/L (km2) | Dispersion Area for Different Particle Size Categories After 1 Day of Cessation (km2) | Dispersion Area for Different Particle Size Categories After 3 Days of Cessation (km2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10 μm | 10–30 μm | <10 μm | 10–30 μm | ||

| 1 | 2.57 | 2.36 | 0.63 | 1.08 | - |

| 2 | 1.69 | 1.65 | 0.48 | 0.53 | - |

| 3 | 1.90 | 1.75 | 0.49 | 0.90 | - |

| 4 | 3.80 | 3.76 | 1.14 | 2.41 | - |

| 5 | 2.17 | 2.17 | 0.94 | 1.55 | - |

| 6 | 2.72 | 2.52 | 0.89 | 1.44 | - |

| Case No. | Distance from Source to Maximum Thickness Location (km) | Maximum Re-Deposition Thickness (mm) | Area with Re-Deposition Thickness > 1 mm (km2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.55 | 31 | 0.275 |

| 2 | 0.49 | 34 | 0.261 |

| 3 | 0.53 | 33 | 0.263 |

| 4 | 0.56 | 27 | 0.282 |

| 5 | 0.51 | 28 | 0.265 |

| 6 | 0.55 | 28 | 0.267 |

| Indicator | Threshold/Classification | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Turbidity | A threshold of 10 mg/L is set at a specified distance to protect benthic fish species. | [49] |

| Classified into five levels: 0, 16.7, 33.3, 166.7, 333.3 mg/L (impact ranging from low to high). | [50] | |

| Re-deposition thickness | Preliminary critical sediment thickness to keep species disturbance within acceptable environmental limits estimated at 2 cm. | [51] |

| Sediment impact thresholds: 0–1 mm (minor impact), 1–3 mm (moderate), 3–10 mm (significant), >10 mm (severe). Sediment coverage thickness should be <10 mm to avoid cold-water coral exposure. | [49] | |

| Impact classification: 0–1 mm/1–5 mm/5–10 mm (increasing severity). | [48] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Xia, J. Assessing the Environmental Impact of Deep-Sea Mining Plumes: A Study on the Influence of Particle Size on Dispersion and Settlement Using CFD and Experiments. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1987. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13101987

Wang X, Chen Z, Xia J. Assessing the Environmental Impact of Deep-Sea Mining Plumes: A Study on the Influence of Particle Size on Dispersion and Settlement Using CFD and Experiments. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(10):1987. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13101987

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xueming, Zekun Chen, and Jianxin Xia. 2025. "Assessing the Environmental Impact of Deep-Sea Mining Plumes: A Study on the Influence of Particle Size on Dispersion and Settlement Using CFD and Experiments" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 10: 1987. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13101987

APA StyleWang, X., Chen, Z., & Xia, J. (2025). Assessing the Environmental Impact of Deep-Sea Mining Plumes: A Study on the Influence of Particle Size on Dispersion and Settlement Using CFD and Experiments. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(10), 1987. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13101987