Abstract

Traditional cooperative navigation algorithms for multiple AUVs are typically designed for a single specific configuration, such as parallel or leader-slave. This paper proposes a novel cooperative navigation algorithm based on factor graph and Lie group to address the multi-AUV localization problem, which is applicable to various multi-AUV configurations. First, the motion state of an AUV is represented within the two-dimensional special Euclidean group (SE(2)) space from Lie theory. Second, the motion of the AUV and acoustic-based range and bearing measurements are modeled to derive the motion error function and the range and bearing error function, respectively. Depending on the formulation of the motion error function, the proposed approach comprises two methods: Method 1 and Method 2. Third, the Gauss-Newton method is employed for nonlinear optimization to obtain the optimal estimates of the motion states for all AUVs. Finally, a parameter-level simulation system for AUV cooperative navigation is established to evaluate the algorithm’s performance under two different multi-AUV configurations. Method 1 is designed for parallel configurations, reducing the average RMSE of position and orientation errors by 29% compared to the EKF. Method 2 is tailored for leader-slave configurations, reducing the average RMSE of position and orientation errors by 38% compared to the EKF. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm achieves superior performance across different AUV configurations compared to conventional EKF-based approaches.

1. Introduction

In the field of marine exploration and development, the cooperative operation mode of Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) clusters demonstrates great potential in applications such as seabed mapping, resource exploration, and military operations [1,2,3,4]. For large-scale underwater monitoring missions, the multi-AUV cooperative exploration and data fusion mode offers advantages including extensive coverage, strong mission fault tolerance, and high data acquisition efficiency. The underwater environment is characterized by limited communication capabilities and rapid attenuation of positioning signals, making high-precision cooperative navigation (CN) systems a core technology for achieving multi-AUV coordination [5,6,7,8]. Through CN technology, multiple AUVs can share positional information and environmental perception data, effectively mitigating navigation error accumulation in individual AUVs, and significantly enhancing the positioning accuracy and mission reliability of cluster operations.

At present, CN algorithms can be broadly categorized into the following three types: filter-based, graph theory-based, and optimization theory-based.

1.1. Filter-Based CN Algorithms

Filter-based CN and localization algorithms predominantly adopt the Kalman filter (KF) framework. The Kalman filter is an optimal estimation method based on the principle of minimum variance, capable of estimating system states, eliminating redundancy, and predicting future states. Consequently, filter-based CN algorithms have been extensively researched.

Harris et al. [9] utilized numerical simulations to assess the influence of range-rate observations on the performance of the Centralized Extended Kalman Filter (CEKF) CN algorithm. Their results demonstrate that the inclusion of range-rate measurements can offer benefits compared to range-only approaches, particularly in scenarios where the accuracy of range measurements is degraded. Gao et al. [10] developed a Huber-based iterated divided difference filter (HIDDF) for cooperative localization of AUVs using a single surface leader. This technique delivers improved accuracy and faster convergence relative to the standard DDF under conditions of weak observability and significant initial errors, while also exhibiting robustness against outliers. Zhao et al. [11] introduced an unscented particle filter framework for multi-leader AUV cooperative localization aimed at overcoming limitations related to low accuracy and non-Gaussian noise. The approach effectively mitigates particle depletion and enhances positioning precision across diverse noise environments. Huang et al. [12] presented a new adaptive extended Kalman filter (EKF) to tackle the issue of unknown noise covariance in AUV cooperative localization. By employing an online expectation-maximization strategy, the method dynamically estimates both prediction error and measurement noise covariance. Zhang et al. [13] put forward a consistent EKF-based cooperative localization method for multi-AUV systems to resolve state estimation inconsistencies. Through correction of linearized measurements in the Jacobian matrix, their strategy ensures estimation consistency. Kim et al. [14] formulated a cooperative algorithm for multi-AUV navigation and sea current estimation that utilizes fused Kalman filters. Requiring only one leader AUV equipped with Doppler Velocity Log (DVL) and Ultra Short Baseline (USBL), the method enhances group localization performance in environments with unknown currents, as supported by simulation studies. Li et al. [15] constructed a robust leader–slave CN algorithm for AUVs based on Student’s t extended Kalman filter (SEKF), which strengthens resistance to outliers arising from acoustic communication and unreliable sensors in comparison to conventional Gaussian-based EKF. Zhu et al. [16] proposes a leader-slave AUV CN method to overcome accuracy degradation and limited beacon calibration range in underwater missions. To counter drift from ocean currents, a navigation model incorporating current velocity as a state variable is developed using five filtering methods.

1.2. Graph Theory-Based CN Algorithms

Graph theory-based algorithms address complex systems by constructing simple yet effective graphical models and applying fundamental graph theory techniques to solve related problems. In cooperative localization systems, this involves first establishing a graphical model of the system, then utilizing measurement data as connecting edges between graph nodes, and finally employing graph theory algorithms to compute optimal estimates.

Fan et al. [17] proposes a novel factor graph and sum-product (FGS) based cooperative positioning algorithm for autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) to address the limitations of traditional Kalman filter methods in multi-sensor fusion applications. The proposed improved FGS (IFGS) algorithm employs a Bayesian framework to reduce linearization errors and incorporates a robust data processing mechanism to enhance estimation accuracy. Ben et al. [18] proposes a novel factor graph with cycles (CFG)-based leader–slave CN algorithm for multi-AUV systems. By incorporating range and bearing measurements, the method estimates the slave AUV’s position and orientation. Cycles introduced by bearing data are resolved via clustering, enabling efficient inference using the sum-product algorithm. Ma et al. [19] proposes a factor graph-based parallel CN algorithm for AUVs in unknown underwater environments. The method constructs a factor graph model that distributes local navigation and inter-AUV observation data across platform nodes. Message passing within the graph enables optimal state estimation for each AUV. Li et al. [20] proposes HTACL, a hybrid TOA/AOA cooperative localization algorithm for multi-AUV systems in anchor-free environments. By jointly utilizing TOA and AOA measurements, the method reduces inertial error accumulation and enhances relative positioning accuracy. Li et al. [21] proposes a factor graph-based cooperative localization algorithm for multi-AUV systems that uses Mercator projection to bridge geodetic and Cartesian coordinate discrepancies. The method constructs a cycle-free factor graph model to efficiently estimate slave AUV states via the sum-product algorithm, avoiding additional computational cycles. Guo et al. [22] addresses localization delays in multi-AUV cooperative systems caused by slow underwater acoustic communication. A prediction model is proposed that uses least squares to estimate unreceived distance data and incorporates maximum correntropy criterion into factor graph optimization. Ben et al. [23] proposes a factor graph-based CN algorithm with a stretching nodes’ strategy to mitigate unknown ocean current disturbances in multi-AUV systems. By incorporating ocean current velocities as variable nodes and transforming cyclic graphs into cycle-free structures, the method enables simultaneous estimation of AUV states and current velocities using a parametric sum-product algorithm.

1.3. Optimization Theory-Based Cooperative Navigation Algorithms

Optimization algorithms enhance CN and localization performance by breaking down complex problems into simpler subproblems. The process involves establishing constraint equations for the system, defining an objective function, and solving for the optimum value of this function to obtain an optimized solution.

Zhang et al. [24] proposes a dual-leader CN method for AUVs using the Cross-Entropy (CE) algorithm and Markov Decision Process (MDP). By predefining slave AUV trajectories, the approach optimizes leader AUV paths probabilistically to minimize observation error and maintain suitable ranging distances. Nerurkar et al. [25] proposes a distributed Maximum A Posteriori (MAP) estimator for multi-robot cooperative localization. The method distributes data and computations across robots to reduce memory and processing demands compared to centralized approaches. It incorporates a distributed data-allocation scheme and conjugate gradient optimization to improve computational efficiency and robustness. Zhou et al. [26] proposes SAPSO-AUFastSLAM, an improved algorithm for AUV simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) that adaptively estimates time-varying observation noise and optimizes particle resampling. It incorporates adaptive noise correction and simulated annealing particle swarm optimization to prevent filter divergence and avoid local minima. Bo et al. [27] enhances a previously developed Huber-based robust cooperative localization algorithm for AUVs by incorporating adaptive noise estimation. The proposed method uses a covariance matching technique to estimate both Gaussian and non-Gaussian process and measurement noise in real time, thereby adjusting the filter gain adaptively. Zhu et al. [28] proposes a hierarchical reinforcement learning-based method for leader-slave multi-AUV CN to mitigate positioning errors caused by low-precision sensors. The approach formulates the problem as a semi-Markov decision process and combines hierarchical reinforcement learning with a polar Kalman filter for trajectory planning.

CN algorithm based on factor graph enables highly accurate and robust state estimation by providing a transparent framework for modeling and optimizing over complex measurement relationships. In this paper, we design a CN algorithm based on factor graph and Lie group. To perform nonlinear optimization, the motion states of AUVs are described using the two-dimensional special Euclidean group (SE(2)) space. To calibrate and fuse data, error functions are derived by modeling AUV motion and acoustic ranging and bearing measurements. The Gauss-Newton method is then employed to solve this nonlinear optimization problem for optimal state estimation. To accurately simulate the actual performance of AUVs, a parameter-level cooperative navigation simulation system is established. Simulation experiments demonstrate that the proposed algorithm outperforms the EKF algorithm across different AUV configurations.

Unlike prior factor-graph works for AUV CN that rely on the sum-product algorithm, our method leverages a nonlinear optimization backend (Gauss-Newton) on Lie groups, yielding higher accuracy and robustness. The main contributions of this paper and its distinctions from the state of the art are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Novel State Representation: Unlike existing factor graph-based CN methods [17,18,19,20,21,22,23] that typically represent the AUV state in vector space (e.g., , this work is the first to utilize the two-dimensional Special Euclidean Group SE(2) from Lie theory to describe the motion state of AUVs. This representation provides a more natural framework for handling the rigid-body motions of AUVs.

- (2)

- Dual-Mode Optimization Framework: We propose two distinct optimization methods tailored for different operational configurations. Method 1 is designed for parallel configurations where all AUVs possess similar sensor accuracy. Method 2 is specifically tailored for leader-slave configurations, which strategically leverages the high-precision attitude information from a well-equipped leader AUV, preventing the degradation of its attitude estimate by noisy acoustic measurements—a common issue in standard EKF or single-method factor graph approaches.

- (3)

- Comprehensive Performance Validation: A parameter-level simulation system that incorporates AUV dynamics is established for evaluation. The proposed methods demonstrate superior performance compared to the conventional EKF, with significant reductions in average RMSE for both parallel (29% reduction with Method 1) and leader-slave (38% reduction with Method 2) configurations.

2. Structures and Devices of Multiple AUVs

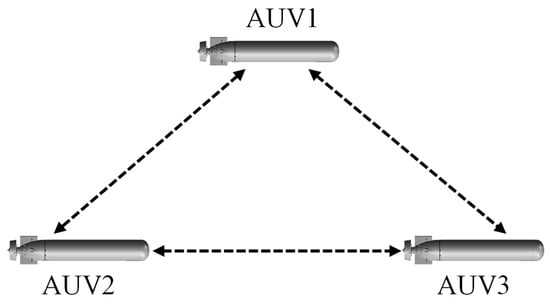

A CN system for multiple AUVs has two structures: parallel configuration and leader-slave configuration.

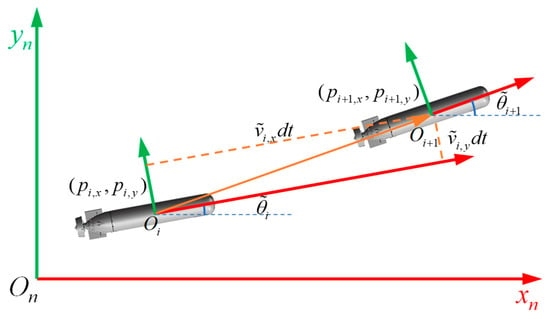

2.1. Parallel Configuration

Parallel configuration, as shown in Figure 1, means that there is no distinction between primary and secondary AUVs. Each AUV has the same function and uses its own navigation sensor to determine its own position. Through underwater acoustic communication, it exchanges information with other AUVs in the system and obtains the position information of neighboring AUVs. Parallel configuration, due to the equal status of each AUV and flexible system configuration, the failure of one AUV will not have a significant impact on the system. Therefore, it has good robustness and is suitable for performing tasks that are easily damaged by some aircraft.

Figure 1.

Parallel configuration.

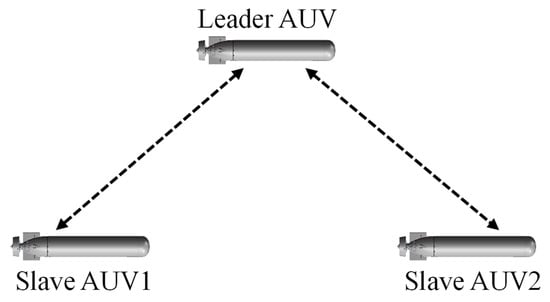

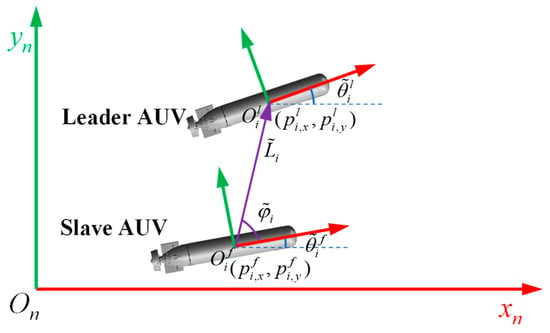

2.2. Leader-Slave Configuration

The leader-slave configuration refers to a small number of AUVs equipped with high-precision navigation equipment as the main reference nodes, while other vehicles are equipped with relatively low-precision navigation equipment. According to the different number of leader AUVs, the positioning system can be divided into two modes: single leader and multi leader. The single leader system selects one AUV equipped with high-precision navigation equipment as the leader AUV, and the rest are slave AUVs. The single leader system has simple navigation, easy deployment, relatively low cost, and good operability. However, because the overall navigation performance of the CN system depends on the main vehicle, high requirements are placed on the positioning ability, reliability, and stability of the leader AUV. The typical leader-slave structure is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Leader-slave configuration.

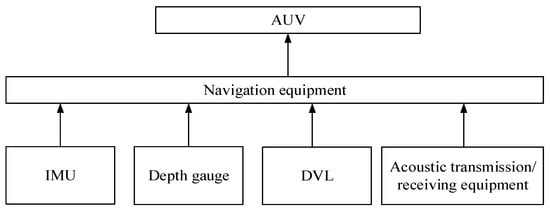

The algorithm of CN between two AUVs can be extended to multiple AUVs. This article studies the algorithm for CN between two AUVs. Without appointing configuration, one AUV is referred to as the leader AUV and the other AUV is referred to as the slave AUV. As shown in Figure 3, for CN system, AUVs will be equipped with IMU, DVL, depth gauge, and acoustic transmission/receiving equipment. In addition, the distance and direction measurement modes of cluster AUVs studied by different scholars are not completely the same. The mode studied in this article is the transmission from the leader AUV to the receiving from the slave AUV, which means that only from slave AUV has measuring functions.

Figure 3.

Navigation equipment.

3. Factor Graph Optimization Theory

This section reviews the well-established theories of factor graph and maximum a posteriori estimation, which form the foundational framework for our proposed algorithm [29,30].

Factor graph is a bipartite graph model used to represent the joint probability distribution of random variables. The factor graph model can be defined as a set of state nodes , a set of factor nodes , and an edge set connecting nodes. State nodes represent random variables of the probability distribution. Factor nodes represent the probability function of local state variables and are also local functions of factorization. The edge represents the relationship between factor nodes and state variables. The factor graph model represents the joint probability distribution of state variables through state nodes, factor nodes, and edges, and the posterior estimation solution of state variables is the optimal estimation value under joint constraints. According to Bayes’ formula, if there are state variables and measurement values at a given time, the posterior probability density of the set of state variables can be decomposed into:

In the decomposition results of the above equation, and correspond to the likelihood probability density of the state variables and measurement information in the factor graph, respectively. In the factor graph, both the posterior probability density and the prior probability are represented by factor nodes . Therefore, the posterior probability density of the state variable in Equation (1) can be rewritten as a factorization form:

where is the subset of state nodes connected to factor . The maximum posterior estimate of the state variable in the factor diagram is:

For Gaussian distributed noise, factors have probability distributions in the following form:

Among them, represents the observation function of the state variable, represents the actual observation value, represents generalized subtraction, and represents the weight matrix. The nonlinear least squares optimization objective of factor graph can be written as

Among them, , represents the error function of nonlinear optimization in the factor graph.

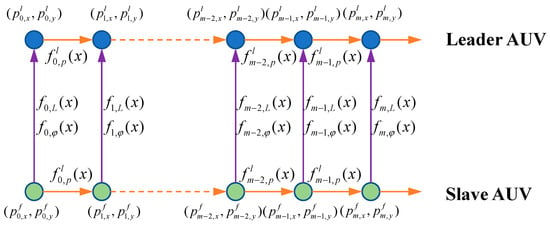

The specific factor graph model for our multi-AUV cooperative navigation system, which visualizes these state nodes and factors (e.g., motion, range, bearing), is depicted in Figure 7 in Section 4.3.

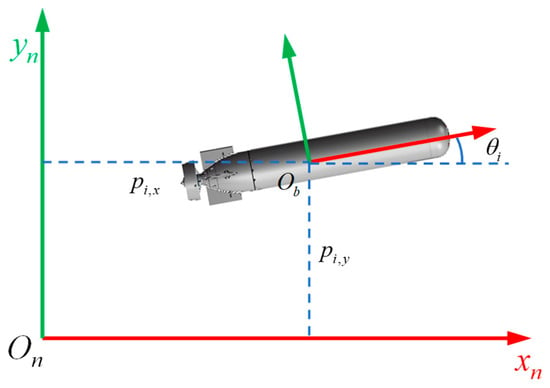

4. Modeling Based on Li Group

4.1. Model Design

As shown in Figure 4, the navigation process of AUV is generally divided into navigation coordinate system and body coordinate system . In CN system, all AUVs use the same navigation coordinate system.

Figure 4.

Coordinate System.

The depth gauge equipped on AUVs usually has high accuracy, and the cooperation tasks of AUVs are usually carried out in a fixed depth state, so it can be considered that all AUVs move in a two-dimensional plane. The state of AUV at time can be represented as:

where and represent the position of the AUV in the and directions of the navigation coordinate system, and represents the heading angle of the AUV in the navigation coordinate system. Obviously, is in the vector space.

In the factor graph, the set of AUV states from time 0 to time m can be represented as:

The pose of a vehicle in a two-dimensional plane can also be represented using the SE(2) space in the Lie group, and the motion state of the AUV at the time can also be expressed as pose matrix:

where represents the rotation matrix from the navigation coordinate system to the body coordinate system, and represents the translation transformation vector from the navigation coordinate system to the body coordinate system. in SE(2) space and in the vector space correspond to each other, and their conversion relationship is represented by the symbols Log and Exp as follows:

where is the variation in SE(2) space with respect to the increment in the vector space. Two-dimensional Lie group SE(2) uses a single matrix multiplication to describe complex transformations uniformly, represents orientation via rotation matrices, naturally avoids singularities, and enables unconstrained optimization on its corresponding Lie algebra, resulting in more efficient and stable computations. The set operation definitions for the two-dimensional Lie group SE(2) are as follows:

Its Jacobian matrix can be derived using the following formula:

When , Equation (11) can be transformed into:

The adoption of the SE(2) Lie group for state representation is motivated by the limitations of optimizing over states parameterized in vector space (e.g., using Euler angles for orientation). Such parameterizations can suffer from singularities (gimbal lock) and constraints, leading to instability and inefficiency in nonlinear optimization. The Lie group framework provides a more natural and robust foundation for describing the rigid-body motions of AUVs. By representing the state on the SE(2) manifold, we achieve a more stable and efficient estimation process. This constitutes a fundamental aspect of our novel methodology.

4.2. Observation Model Based on Li Group

The AUV CN process includes motion observation and measurement of range and bearing.

4.2.1. Motion Model

Assuming that at time , the velocity measurements of DVL are and the angle measurement of IMU is , as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of motion model.

The pose change measurements from time 0 to time m can be represented by SE(2). So, the error function f of the pose change measurement can be expressed as:

The notation denotes the A-norm induced by a symmetric positive definite matrix A. It is defined for a vector as: . Where denotes the weight matrix of pose transformation measurement.

4.2.2. Range and Bearing Model

At time , the pose of the leader AUV is , the pose of the follower AUV is , and the measurements of range and bearing are . The schematic diagram of direction and distance measurement process is shown in Figure 6:

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of range and bearing.

The range error function at time can be expressed as:

where represents the weight matrix of ranging. The bearing error function at time can be expressed as:

where represents the weight matrix of bearing.

4.3. System Structure of Factor Graph

From time 0 to time m, the leader AUV has a pose set …, and the slave AUV has a pose set …. Figure 7 depicts the motion model and range and bearing factors of the entire process.

Figure 7.

System structure of factor graph.

According to (5), the nonlinear least squares optimization objective of the factor graph can be written as:

Optimizing the above equation can obtain the optimal estimation value of the master and slave AUV poses at all times, which is denoted as …, , …, .

The modeling method for the error function in the factor diagram mentioned above is called Method 1, which optimizes the heading angles of both the master and slave AUVs simultaneously. This is suitable for situations where both AUVs use low-precision IMUs.

The aforementioned factor graph error function modeling approach is referred to as Method 1. It simultaneously optimizes the heading angles of both the master and slave AUVs, which is suitable for scenarios where both AUVs are equipped with low-precision IMUs. During the factor graph fusion process, this method essentially performs a weighted average between the leader AUV’s attitude angle measurements and the slave AUV’s attitude angle measurements, which are augmented with underwater acoustic range and angle measurements. However, in cases where the leader AUV is equipped with a high-precision IMU, this fusion approach may in fact compromise the accuracy of its attitude estimates.

Therefore, Method 2 is adopted to model the motion measurement errors of the leader AUV. The error function for its position change measurements can be expressed as:

Compared to Equation (13), the error function of the leader AUV motion model only includes the measurement error of position, without considering the measurement error of attitude. The nonlinear least squares optimization objective of factor graph for Method 2 is as follows:

The factor graph serves as a transparent and flexible framework for probabilistic modeling, representing the joint probability distribution of all AUV states given the measurements. The innovation of this work lies in the synergy between this modeling framework and the Lie group representation. While the factor graph elegantly encapsulates the system’s probabilistic constraints, the use of the SE(2) Lie group provides the mathematical foundation for the state representation and the subsequent optimization on the manifold. This combination allows for a principled and accurate formulation of the cooperative navigation problem.

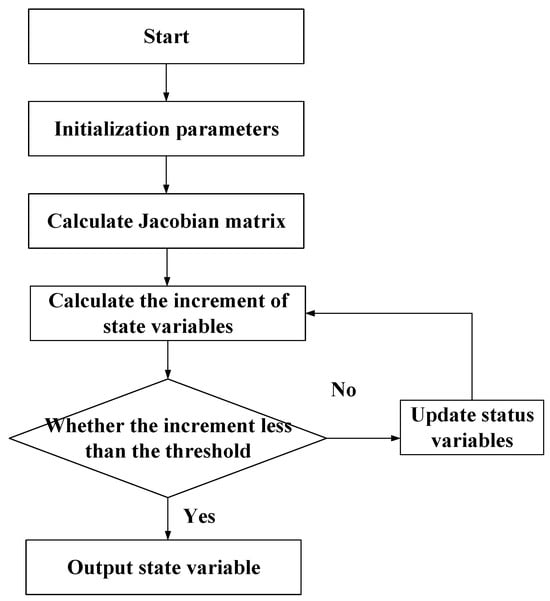

4.4. Method of Solving Factor Graph

The Gauss-Newton method is used to solve the nonlinear least squares problem. The key step is to linearize the error functions on the manifold. we define a perturbation in the vector space. The error function is approximated as:

where is the Jacobian matrix of the error function with respect to . Substituting it into the least squares optimization objective of (13) (15):

By making the first-order derivative of is equal to 0, we can obtain:

By iteratively solving the above equation to obtain , the optimal estimate of can be obtained. The flowchart of the Gauss Newton method is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The flow chart of algorithm.

The Lie group formulation inherently facilitates the computation of Jacobian matrices by providing a structured manifold framework. To demonstrate this advantage, the range error function , excluding weighting factors, is analyzed as a representative case for Jacobian derivation

In practical applications of solving factor graphs for cooperative navigation, a key distinction of our approach lies in the solver selection. Unlike prior factor graph methods for AUVs that often rely on the Sum-Product Algorithm [17,18,19], the core innovation of this work is the adoption of the Gauss-Newton method as the backend solver on the Lie group manifold. This paradigm shift from a probabilistic inference algorithm to a nonlinear optimization technique is crucial. Operating directly on the SE(2) manifold, the Gauss-Newton method provides higher linearization accuracy and better estimation consistency by avoiding the approximations often required by the Sum-Product Algorithm, especially in graphs with cycles.

To ensure the practical feasibility of this optimization-based approach, a sliding window strategy is employed. Only a limited number of recent states are maintained for optimization, as the influence of earlier historical states on the current state is negligible. This approach effectively controls computational complexity by focusing on the most relevant states. For a sliding window of size W time steps, the number of state variables optimized in each iteration remains constant at 2 × W × 3 (for two AUVs in SE(2)), preventing unbounded growth in computational cost over time. For example, with a window size of W = 30, the number of optimized variables is 180.

We analyzed the computational efficiency to demonstrate the real-time capability of the proposed algorithm. The simulations were conducted on a standard desktop CPU. The average time required to solve the nonlinear optimization problem per update was empirically measured to be below 50 ms. Given that the acoustic ranging and communication updates typically occur at a 1 s interval in AUV applications, the computational demand of our algorithm is well within the available time budget, confirming its potential for real-time operation. It is important to note that the EKF, due to its recursive nature, has a lower and constant computational cost per update. The significant gain in estimation accuracy (29–38% reduction in RMSE, as shown in Section 5.2 and Section 5.3) achieved by our method justifies this acceptable increase in computational load. The scalability of the approach for larger teams of AUVs will be a focus of our future work.

4.5. AUV Cooperative Navigation Simulation System

It is often difficult to obtain accurate ground truth poses of AUVs in underwater navigation experiments, so precise simulation experiments can be used to compare and verify the above algorithms. According to reference [31], the dynamic equation of AUV is as Equation (23), and the meanings represented by each variable are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of symbols in simulation system.

By iteratively calculating Equation (23) using the Euler method, the linear velocity and angular velocity of the AUV at each moment can be obtained, as well as the true position and angle.

AUVs can acquire simulated measurements such as acceleration, angular velocity, velocity, and inter-AUV distance and angle, corresponding to IMU, DVL, and sonar sensors for ranging and bearing. The of Equation (23) refer to the acceleration of the AUV in the body coordinate system, while the measurement of IMU is the acceleration in the navigation coordinate system. The relationship between the velocity of the body coordinate system and the navigation coordinate system is:

where is the velocity of navigation coordinate system, and is velocity of the body coordinate system. By taking the derivative, the acceleration of AUV in the navigation coordinate system can be obtained:

where is the velocity of navigation coordinate system, and is angular velocity of AUV. By adding Gaussian noise to the above measurements, a parameter level CN simulation system can be constructed.

5. Experiments and Results

5.1. Experimental Setup

The relative deviation between the planned trajectories of the leader AUV and the follower AUV is set to 10 m. The controller receives the real motion data of the AUVs to ensure they follow the planned trajectories. During this process, Gaussian noise is added to the true values of the AUV’s acceleration, angular velocity, linear velocity, relative distance, and relative angle to simulate the corresponding measured values.

Two simulation conditions were set up for the AUV cluster structure, corresponding to parallel and leader-slave configurations. In the first experiment, a parallel configuration is adopted: both the leader and follower AUVs are equipped with the same low-precision IMU1. In the second experiment, a leader-slave configuration is used: the leader AUV is equipped with a high-precision IMU2, while the follower AUV uses the low-precision IMU1. The relevant equipment parameters are provided in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Equipment parameters.

5.2. Simulation Result of Parallel Configuration

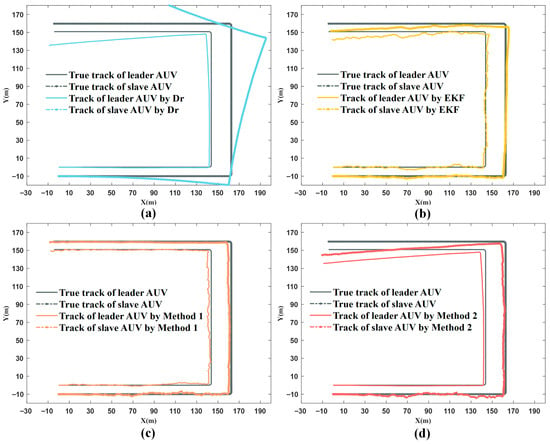

Under the first set of simulation conditions, the trajectory of the AUV was estimated using dead reckoning (Dr), extended Kalman filtering (EKF) [32], Method 1, and Method 2, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Estimation trajectory of different algorithms. (a) Comparison between true track and DR track; (b) Comparison between true track and EKF track; (c) Comparison between true track and Method1 track; (d) Comparison between true track and Method 2 track.

It can be observed that due to the relatively low accuracy of the IMU and the absence of sonar-based ranging and directional information, the trajectories of the two AUVs under Dr increasingly deviate from the true values, with significant heading angle errors, posing challenges in practical applications. The trajectories of the leader and follower AUVs estimated by the Kalman filter generally follow the true trajectory and remain relatively parallel. However, since the Kalman filter relies solely on single-instance ranging and directional measurements with substantial error noise, the estimated trajectory exhibits considerable oscillations.

In contrast, the trajectories estimated by Method 1 also follow the true trajectory and maintain mutual parallelism, with the leader’s trajectory showing smaller oscillations compared to the Kalman filter. Method 2, on the other hand, produces a leader trajectory consistent with Dr. While it partially mitigates oscillations in the follower’s estimated trajectory, the leader’s heading deviation results in an overall bias in the trajectories.

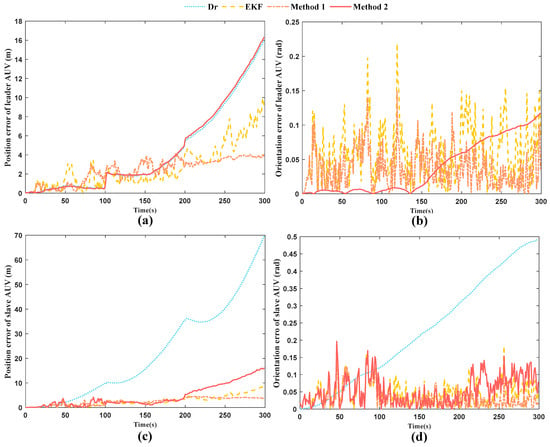

From Figure 10 and Table 3, it can be seen that in the case of using two low-precision IMUs in a distributed cluster, Method 1, with the minimum RMSE, should be used for parallel configuration. It can be observed that in terms of the position of the leader AUV, the orientation of the leader AUV, the position of the follower AUV, and the orientation of the follower AUV, the error RMSE of Method 1 is reduced by 24%, 43%, 16%, and 33%, respectively, compared to the EKF, with an average reduction of 29%.

Figure 10.

Error of different algorithms. (a) Comparison of position errors of leader AUVs using different algorithms; (b) Comparison of orientation errors of leader AUVs using different algorithms; (c) Comparison of position errors of slave AUVs using different algorithms; (d) Comparison of orientation errors of slave AUVs using different algorithms. Orientation error is presented in radians. For improved readability, note that 0.1 rad ≈ 5.73.

Table 3.

Error analysis (RMSE: Root Mean Square Error; MAXE: Maximum Absolute Error).

5.3. Simulation Result of Leader-Slave Configuration

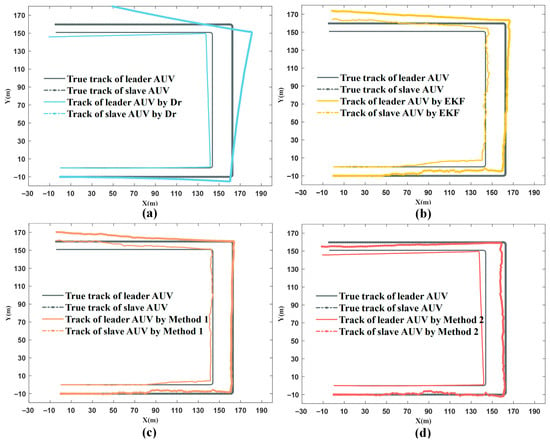

Under the second set of simulation conditions, the trajectory of the AUV was estimated using Dr, EKF, Method 1, and Method 2, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Estimation trajectory of different algorithms. (a) Comparison between true track and DR track; (b) Comparison between true track and EKF track; (c) Comparison between true track and Method1 track; (d) Comparison between true track and Method 2 track.

It can be observed that due to the high precision of the leader AUV’s IMU, the trajectory estimated by Dr remains very close to the true value throughout. However, the trajectory of the follower AUV based solely on Dr deviates significantly from the true trajectory. Noises in ranging, bearing, and the follower’s IMU affect the estimated trajectory of the leader, causing both the leader’s and the followers’ estimated paths to deviate from the true values.

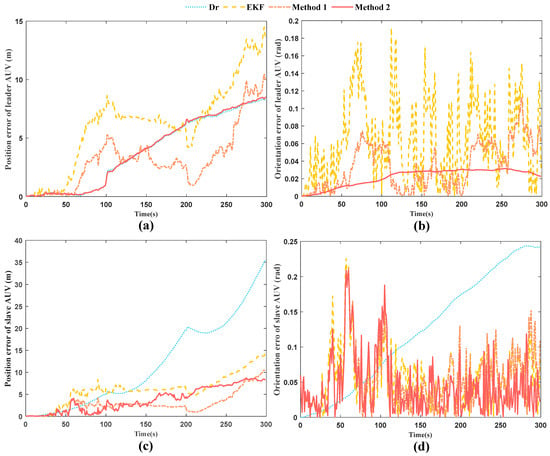

In Method 2, the trajectory of the leader AUV is estimated entirely using the attitude angles provided by the high-precision IMU. The ranging and bearing noises do not degrade its heading accuracy. As a result, the leader’s trajectory almost coincides with that of the Dr leader, and the trajectory of the follower AUV is also significantly corrected. As demonstrated in Figure 12 and Table 4, the pose errors of the leader AUV in Method 2 are consistent with those of Dr and are smaller than those of the EKF and Method 1. Meanwhile, the pose errors of the follower AUV are noticeably smaller than those of the previous two methods.

Figure 12.

Error of different algorithms. (a) Comparison of position errors of leader AUVs using different algorithms; (b) Comparison of orientation errors of leader AUVs using different algorithms; (c) Comparison of position errors of slave AUVs using different algorithms; (d) Comparison of orientation errors of slave AUVs using different algorithms. Orientation error is presented in radians. For improved readability, note that 0.1 rad ≈ 5.73.

Table 4.

Error Analysis.

It can be observed that in terms of the position of the leader AUV, the orientation of the leader AUV, the position of the follower AUV, and the orientation of the follower AUV, the error RMSE of Method 2 is reduced by 31%, 75%, 32%, and 14%, respectively, compared to the EKF, with an average reduction of 38%.

As stated in Section 4.5, the average optimization time per update was consistently below 50 ms in our simulations. This timing data solidly supports the real-time capability of the proposed method, as it is an order of magnitude faster than the 1 s cycle of acoustic measurements.

6. Conclusions

This paper addressed the cooperative navigation problem for multi-AUV systems under different configurations by proposing a novel optimization algorithm based on factor graph theory and Lie group theory.

The main contributions and conclusions of this study are summarized as follows:

Novel Methodology: This work is the first to utilize the two-dimensional Special Euclidean Group SE(2) to describe the motion state of AUVs. Based on this representation, error functions for both the motion model and the acoustic ranging/bearing model were formulated, effectively transforming the cooperative navigation problem into a nonlinear least-squares optimization problem on the Lie group.

Dual Optimization Strategies: Two distinct optimization methods (Method 1 and Method 2) were proposed to cater to different AUV configurations. Method 1 is designed for parallel configurations, simultaneously optimizing the poses of both the leader and follower AUVs. Method 2 is tailored for leader–follower configurations; it fully trusts the leader’s high-precision attitude sensor, optimizing only its position, thereby preventing the contamination of the leader’s attitude estimate by acoustic measurement noise.

Superior Performance: The effectiveness of the proposed algorithms was validated through parameter-level simulation experiments. The results demonstrate that in parallel configurations, Method 1 reduces the average RMSE of position and orientation errors by 29% compared to the traditional Extended Kalman Filter (EKF). In leader–follower configurations, Method 2 performs even better, achieving a significant 38% average reduction in RMSE, which highlights a substantial improvement in navigation accuracy.

The proposed algorithm is not dependent on a specific AUV formation configuration. Its flexible factor graph model effectively fuses observations from diverse sources, demonstrating strong generality and robustness.

In conclusion, the factor graph and Lie group-based cooperative navigation algorithm proposed in this paper provides an effective and versatile solution for the precise pose estimation of multi-AUV systems. Future work will focus on extending the algorithm to three-dimensional space (SE(3)) and further investigating its performance under more practical challenges, such as communication delays and packet loss. It is important to note that a direct comparative analysis with other state-of-the-art multi-AUV localization algorithms was not conducted. This is due to the current absence of standardized benchmark scenarios and the fact that advanced algorithms are typically validated under specific, non-uniform simulation setups or configurations that differ from this study. Future work will aim to address this gap by engaging in collaborative efforts to establish common benchmarks for the community.

Author Contributions

This study is the result of cooperative teamwork. Conceptualization, J.L.; validation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, X.B.; visualization, X.B.; supervision, C.W., J.L. and X.B. contributed equally to this paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2023YFC2809604).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Qi, C.; Ma, T.; Li, Y.; Ling, Y.; Liao, Y.; Jiang, Y. A Multi-AUV Collaborative Mapping System With Bathymetric Cooperative Active SLAM Algorithm. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 12, 12441–12452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Qiao, C. Cooperative search and survey using autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs). IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2010, 22, 364–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Hu, Q.; Feng, H.; Feng, X.; Su, W. A cooperative hunting method for multi-AUV swarm in underwater weak information environment with obstacles. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblond, I.; Tauvry, S.; Pinto, M. Sonar image registration for swarm AUVs navigation: Results from SWARMs project. J. Comput. Sci. 2019, 36, 101021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Mei, D.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; Sun, W.; Wang, D.; Chen, J. Task allocation for Multi-AUV system: A review. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 112911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Fan, H.; Yang, G. Angle-Constrained Cooperative Guidance Law with Limited Communication for Multi-AUV. In Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Mechanical and Electronics Engineering (ICMEE), Xi’an, China, 27–29 December; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Xu, X.; Cai, M.; Liu, K. Master-slave AUV cooperative navigation algorithm based on nonlinear error compensation of observation matrix. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2025, 36, 076312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, B.; Su, Z. Multi-mode fault-tolerant trajectory tracking control of AUV under thruster failure conditions in complex environments. Ocean Eng. 2025, 330, 121257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Z.J.; Whitcomb, L.L. Preliminary study of cooperative navigation of underwater vehicles without a DVL utilizing range and range-rate observations. In Cooperative Localization and Navigation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Liu, Y.; Xu, B. Robust Huber-based iterated divided difference filtering with application to cooperative localization of autonomous underwater vehicles. Sensors 2014, 14, 24523–24542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xing, W.; Yuan, H.; Shi, P. A collaborative control framework with multi-leaders for AUVs based on unscented particle filter. J. Frankl. Inst. 2016, 353, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, B.; Wu, Z.; Chambers, J.A. A new adaptive extended Kalman filter for cooperative localization. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2017, 54, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wu, X.; Ma, P. Consistent extended Kalman filter-based cooperative localization of multiple autonomous underwater vehicles. Sensors 2022, 22, 4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Cooperative localization and unknown currents estimation using multiple autonomous underwater vehicles. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 2365–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ben, Y.; Naqvi, S.M.; Neasham, J.A.; Chambers, J.A. Robust student’s t-based cooperative navigation for autonomous underwater vehicles. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2018, 67, 1762–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Duan, Y.; Mu, X.; Bai, G.; Dou, L. An Improved Cooperative Navigation Method for Slave AUV Under the Influence of Ocean Currents. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS), Nanjing, China, 18–20 October 2024; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 1590–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhu, M.; Yu, F. An advanced cooperative positioning algorithm based on improved factor graph and sum-product theory for multiple AUVs. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 67006–67017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, Q.; Zang, X. A novel cooperative navigation algorithm based on factor graph with cycles for AUVs. Ocean Eng. 2021, 241, 110024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, C. Research on AUVs Parallel Cooperative Navigation and Positioning Technology Based on Factor Graph. In Proceedings of the 2024 18th International Conference on Ubiquitous Information Management and Communication (IMCOM), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 3–5 January 2024; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yu, W.; Guan, X. Hybrid TOA-AOA cooperative localization for multiple AUVs in the absence of anchors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 20, 2420–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Huang, H.; Sun, Y.; Ben, Y. A Factor Graph with Mercator Projection-Based Cooperative Localization Algorithm for Multiple AUVs. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 8510810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Yan, X.; Luo, Q.; Lin, J. Cooperative Localization Algorithm for Multiple AUVs Under Communication Delay. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 12–16 May 2025; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; pp. 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ben, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, Q.; Huang, H.; Gong, S. Multi-AUV cooperative navigation algorithm based on factor graph with stretching nodes strategy. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1008715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Tao, X. Cooperative navigation based on cross entropy: Dual leaders. IEEE Access. 2019, 7, 151378–151388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerurkar, E.D.; Roumeliotis, S.I.; Martinelli, A. Distributed Maximum a Posteriori Estimation for Multi-Robot Cooperative Localization. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; pp. 1402–1409. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Qin, P.; He, B. Adaptive slam methodology based on simulated annealing particle swarm optimization for auv navigation. Electronics 2023, 12, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, X.; Razzaqi, A.A.; Yalong, L. Cooperative localisation of AUVs based on Huber-based robust algorithm and adaptive noise estimation. J. Navig. 2019, 72, 875–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Wu, D.; Bai, S.; Ren, R.; Geng, W. An efficient multi-AUV cooperative navigation method based on hierarchical reinforcement learning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrun, S. Probabilistic robotics. Commun. ACM 2002, 45, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barfoot, T.D. State Estimation for Robotics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Prestero, T.T.J. Verification of a Six-Degree of Freedom Simulation Model for the REMUS Autonomous Underwater Vehicle; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gelb, A. Applied Optimal Estimation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).