Abstract

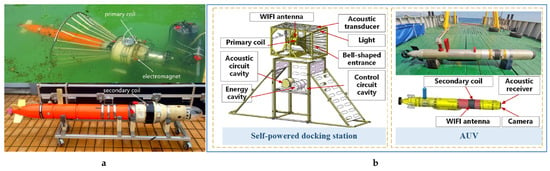

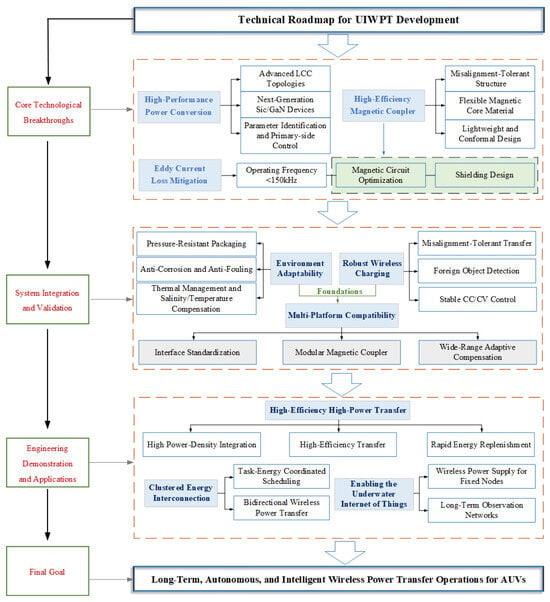

The endurance of autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) has long been constrained by limited energy replenishment. Underwater inductive wireless power transfer (UIWPT), with its contactless power transfer capability, offers an innovative solution for efficient underwater charging of AUVs. This paper provides a systematic review of the architecture of UIWPT systems, analyzes key power loss mechanisms and corresponding optimization strategies, and summarizes the latest research progress in magnetic coupler design, compensation circuit topologies, control methods, simultaneous power and data transfer, and seawater-induced eddy current losses. Representative cases of UIWPT system integration on AUV platforms are also reviewed, with particular emphasis on environmental factors such as salinity variation, biofouling, and deep-sea pressure, as well as EMC, which critically constrain engineering applications. Finally, this paper discusses development trends including high-efficiency power transfer, enhanced reliability under extreme environments, and practical deployment challenges, and it presents a forward-looking technical roadmap towards long-term, autonomous, and intelligent underwater wireless power transfer.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the intensification of marine resource exploration and the growing demand for environmental monitoring have made the development of efficient and intelligent ocean exploration equipment a fundamental requirement in marine scientific research and engineering. Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), owing to their high autonomy and operational flexibility, have become indispensable tools for subsea mapping, resource exploration, ecological monitoring, and other related domains, demonstrating significant potential for both practical applications and academic research [1,2,3].

As exploration missions grow in complexity and duration, the energy demands of AUVs have increased significantly. Currently, AUVs rely on on-board energy storage [4,5]. However, because of limitations imposed by the size and weight of on-board devices, their battery capacities are insufficient to support long-duration and high-performance operations, thereby necessitating external energy replenishment [6,7]. Traditional energy replenishment methods include shore-based recovery charging [8] and underwater docking through wired connections [9,10]. The former requires frequent manual intervention, leading to decreased operational efficiency and elevated costs and risks [4]. The latter approach employs wet-mate connectors for power transfer, which enhances the long-term underwater residency capability of AUVs but remains constrained by corrosion susceptibility and limited mating cycles. Repeated usage can result in electrical faults, reduced equipment reliability, and high maintenance costs [11,12].

The development of wireless power transfer (WPT) technology began in the late 20th century, drawing on Nikola Tesla’s pioneering work in contactless power transfer [13]. It has since been widely applied in electric vehicles [14,15,16], consumer electronics [17], medical devices [18,19], and industrial automation systems [20,21]. WPT enables non-contact power transfer, significantly reducing maintenance requirements and operational risks. It is typically categorized into far-field methods, such as ultrasonic [22] and optical power transfer [23], and near-field methods, such as inductive [24] and capacitive [25] power transfer. In underwater environments, ultrasonic transmission is limited by severe signal attenuation, while optical transmission is hindered by environmental interference such as scattering and turbidity [26]; both face difficulties in achieving stable and efficient power transfer. Capacitive power transfer is limited by its frequency-dependent characteristics and constrained power capacity, leading to poor adaptability in underwater conditions [27,28]. In contrast, inductive wireless power transfer (IWPT) offers high efficiency, substantial power capacity, and enhanced operational safety, making it a key area of research in AUV energy replenishment [29,30].

Despite the significant advantages of IWPT, its implementation in complex underwater environments faces several critical technical challenges. These include substantial signal attenuation caused by the high electrical conductivity of seawater [31,32], system instability induced by hydrodynamic forces [33,34,35], and the pronounced sensitivity of electromagnetic coupling efficiency to environmental fluctuations [36]. Collectively, these factors impose substantial limitations on the continued development, reliable system integration, and large-scale deployment of underwater inductive wireless power transfer (UIWPT) technologies.

In response to these challenges, this paper offers a comprehensive review of recent developments and technological trends in UIWPT systems for AUV applications. The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 introduces the system architecture and operating principles of UIWPT, together with an analysis of energy loss mechanisms in underwater environments and their corresponding optimization strategies. Section 3 provides an in-depth review of key technical advancements, including magnetic coupler design, compensation circuit topologies, control strategies, simultaneous power and data transfer, and eddy current loss analysis. Section 4 discusses representative integration cases of UIWPT systems on AUV platforms and evaluates their performance. Section 5 focuses on the engineering application requirements and systematically examines the critical challenges encountered during real-world implementation. Section 6 discusses development trends in UIWPT technology to support continued innovation and facilitate its application in deep-sea operations. Finally, Section 7 presents the conclusions.

2. System Architecture and Power Loss Mechanisms of UIWPT

UIWPT technology has been increasingly applied to AUV energy replenishment. A thorough understanding of its system architecture and power loss mechanisms is critical for improving overall system performance and charging efficiency.

2.1. System Architecture and Operating Principles

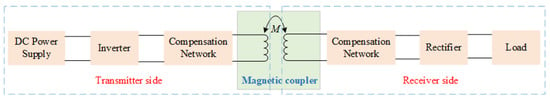

The UIWPT system operates on the principle of Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction, facilitating wireless power transfer via electromagnetic coupling between the primary and secondary coils [37]. The system primarily comprises a power supply unit, high-frequency inverter, resonant compensation network, magnetic coupler, and rectification and filtering circuit. An illustrative schematic of the system architecture is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of a typical UIWPT system’s architecture.

A detailed introduction to the core components of the UIWPT system and their functions is provided below:

- Power Supply Unit: Serves as the system’s energy source, typically comprising high-energy-density battery packs that deliver a stable DC input;

- High-Frequency Inverter [38]: Employs a full-bridge or half-bridge topology to convert DC power into high-frequency AC power;

- Resonant Compensation Network: Includes compensation circuits on both the primary and secondary sides to improve power transfer efficiency and achieve zero phase angle (ZPA) operation;

- Magnetic Coupler: Consists of a transmitting coil, a receiving coil, and an optional magnetic core, facilitating efficient electromagnetic coupling;

- Rectification and Filtering Circuit: Located on the secondary side, this unit employs a full-bridge or half-bridge rectifier with a filtering circuit to convert the received AC power back into DC [39];

- Control Unit: Dynamically regulates output voltage and current in response to variations in the coupling coefficient and load conditions [40]. Additionally, it provides flexible control over other system components as needed.

In a typical subsea charging scenario, where a seabed base station supplies power to an AUV, the system operates as follows: the DC power from the base station’s energy storage system is converted into high-frequency AC by the inverter. This AC power excites the transmitting coil via the resonant compensation network, generating an alternating magnetic field. The field propagates through the seawater medium and couples to the receiving coil within the magnetic coupler, where an AC voltage is induced on the secondary side. The induced AC power is then rectified and filtered to produce a stable DC output, which is used to charge the AUV’s on-board battery pack. The entire process enables fully contactless power transfer.

2.2. Power Loss Mechanisms and Optimization Strategies

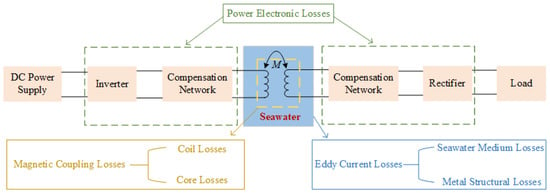

The efficiency of UIWPT systems is a key performance indicator in underwater applications, where electrical energy is scarce and enhancing energy transfer efficiency is particularly essential. In AUV-based UIWPT systems, power losses primarily originate from the magnetic coupler, power electronic components, and eddy current effects. The distribution of these losses is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of loss distribution in the UIWPT system.

2.2.1. Losses in the Magnetic Coupler

Losses in the magnetic coupler represent the dominant source of energy dissipation in UIWPT systems and are generally categorized into coil losses and core losses, collectively accounting for nearly half of the total power losses [41].

Coil losses primarily arise from three mechanisms: skin effect, proximity effect, and DC resistance. The use of Litz wire, composed of multiple individually insulated strands, can substantially mitigate both the skin and proximity effects under high-frequency operation, making their impact negligible. Under such conditions, DC resistance becomes the predominant contributor to coil losses and can be expressed as follows:

In the equation, and represent the root mean square currents on the primary and secondary sides, respectively, while and denote the corresponding DC resistances of the primary and secondary coils. To minimize these losses, several strategies can be adopted. First, increasing the conductor’s cross-sectional area and optimizing the coil winding geometry can effectively reduce resistance. Second, designing an appropriate turns ratio between the primary and secondary windings [42], along with fine-tuning the resonant network parameters, helps to achieve optimal current distribution and minimize transmission loss. Furthermore, integrating robust thermal management techniques can improve overall system efficiency.

Core loss refers to the energy dissipated in magnetic core materials under alternating magnetic fields and consists of both hysteresis losses and eddy current losses [43]. It is commonly estimated using the Steinmetz equation:

In the equation, denotes the material loss coefficient, which reflects the intrinsic dissipation characteristics of the magnetic core material. The exponents and represent the dependencies of core loss on frequency (f) and peak magnetic flux density (), respectively, and describe how the loss varies with operating conditions. Core loss can be effectively suppressed by optimizing the microstructure of the magnetic material to reduce and by appropriately adjusting the values of and [44]. For example, reducing is particularly important in high-frequency applications, while minimizing becomes critical in high-power operating scenarios. These key parameters are typically determined by least-squares fitting to experimental loss curves, enabling accurate prediction and optimal design of core losses [45].

2.2.2. Losses in Power Electronics

Power electronic losses primarily originate from switching events in the inverter, characteristics of the rectifier, and reactive power losses associated with the inductors and capacitors in the compensation network. To systematically reduce these losses, modern power electronic systems increasingly adopt wide-bandgap semiconductor devices such as silicon carbide (SiC) and gallium nitride (GaN). Their superior switching characteristics substantially reduce switching losses and improve overall inverter efficiency [46].

In the rectification stage, synchronous rectification technology, which is characterized by lower conduction voltage drop, is gradually replacing traditional Schottky diode solutions [47]. This approach is particularly effective in low-voltage, high-current applications, where it significantly reduces conduction losses. To minimize losses in the compensation network, a combination of strategies should be adopted. These include the use of air-core inductors to eliminate core losses, the selection of novel magnetic core materials with high permeability and low loss, and the adoption of TDK ceramic capacitors that exhibit high quality factors and excellent thermal stability. Collectively, these measures provide effective control over losses within the compensation network.

2.2.3. Losses in Eddy Current Paths

In practical marine environments, eddy current losses in UIWPT systems applied to AUVs primarily originate from the seawater medium and metallic shielding structures. Specifically, seawater-induced eddy current loss occurs because seawater, as a highly conductive medium, undergoes electromagnetic induction under the influence of alternating magnetic fields, thereby generating eddy currents that dissipate energy in the form of Joule heat. Considering that the seawater gap between most magnetic couplers can be approximated as a cylindrical structure, the eddy current loss under such geometric conditions can be analytically derived from Maxwell’s equations, combined with a planar circular coil model and volume integration in polar coordinates, and is expressed as follows:

where

In the expression, h denotes the vertical distance between the transmitting and receiving coils, r is the coil radius, and is the electrical conductivity of seawater. represents the angular frequency, and is the magnetic permeability (approximately taken as ). n is the number of turns, while and correspond to the currents in the transmitting and receiving coils, respectively. The term serves as the expansion/skin-effect correction factor, whereas reflects the influence of seawater electrical parameters on field dispersion.

These results indicate that seawater-induced eddy current losses are proportional to the electrical conductivity of the medium and to the square of the operating frequency, and they are significantly influenced by coil parameters and current amplitudes. Therefore, optimizing the magnetic shielding structure [48] and appropriately controlling the operating frequency constitute effective approaches to mitigating seawater eddy current losses [49]. Given its complex mechanism and its unique role as a distinct loss component in underwater UIWPT systems, this topic will be further elaborated in Section 3.5.

Metallic eddy current losses primarily originate from the titanium or aluminum alloy hull of the AUV, as well as from the metallic enclosure components of the magnetic coupler. When alternating magnetic fields penetrate these metallic structures, induced parasitic eddy currents are generated within them, leading to energy dissipation. The corresponding expression can be written as follows:

In the equation, H denotes the magnetic field intensity, S denotes the cross-sectional area of the metallic shielding structure, and and denote the magnetic permeability and electrical conductivity of the metal material, respectively. To effectively suppress eddy current losses in metallic shielding structures, several optimization strategies can be implemented. These include replacing conventional metal enclosures with non-metallic composite materials (such as carbon fiber) to eliminate eddy current paths, optimizing the thickness of metallic layers and employing multi-layer shielding configurations to reduce the effective eddy current loop area [50], and reducing the system’s operating frequency to minimize high-frequency eddy current effects.

3. Key Technologies of UIWPT Systems

3.1. Structural Design of Magnetic Couplers

The design of the magnetic coupler in UIWPT systems plays a pivotal role in determining power transfer capability, transmission efficiency, and magnetic field distribution. In the context of AUV applications, such design must not only meet conventional engineering standards but also address the unique challenges posed by the underwater environment. The major challenges and corresponding key design requirements can be summarized as follows:

- Form Factor Conformity: The design of the magnetic coupler must fully account for the structural characteristics of AUVs, particularly their widely adopted streamlined configurations [51]. The geometry of the coupler should closely match the contour of the AUV to minimize hydrodynamic drag and avoid negative effects on its hydrodynamic performance [30];.

- Misalignment Tolerance: Traditional wet-mate charging methods rely on mechanical components to achieve precise alignment, whereas UIWPT technology seeks to reduce dependence on exact docking. Positional shifts between the transmitter and receiver coils, caused by factors such as ocean currents, can significantly degrade overall system performance. Therefore, the magnetic coupler should be designed with a certain degree of misalignment tolerance to compensate for positional deviations within a defined spatial range and to ensure stable and efficient power transfer under complex marine conditions [52].

- Eddy Current Loss Suppression: Eddy current losses in the seawater environment are among the main factors limiting energy transfer efficiency. In the design of the magnetic coupler, the gap between the primary and secondary sides should be minimized to concentrate the magnetic field and reduce its leakage into the surrounding seawater. Additionally, eddy current losses can be significantly reduced by optimizing the selection of magnetic materials and the geometric layout, thereby further improving overall energy efficiency [53];

- EMC [54]: The magnetic fields generated during wireless power transfer may cause EMC with sensitive on-board electronic systems in the AUV, such as navigation units and sensors. To ensure EMC, the design must precisely control the magnetic field distribution through structural optimization and the use of effective shielding materials. This is essential for enhancing the overall safety and reliability of the system.

- Miniaturization and Lightweight Design: Given the stringent constraints on volume and weight in AUV platforms, the magnetic coupler should be designed with a focus on miniaturization and weight reduction [55,56,57]. By selecting high-performance lightweight materials and optimizing structural parameters, the overall weight of the system can be significantly reduced, thereby enhancing the AUV’s mobility, endurance, and energy utilization efficiency.

The design of magnetic couplers is typically based on the docking configuration of the AUV. While certain AUVs are designed to dock with surface vessels or motherships, the most common application scenario is docking with subsea base stations. Currently, AUV-to-station docking methods are generally categorized into three types: capture-type [58,59], platform-type [60,61], and guided docking [62]. Among these, the guided docking approach utilizes a guide-shroud structure to achieve precise alignment, significantly reducing positional deviations during the docking process and thereby improving the overall success rate. This advantage has established guided docking as the mainstream solution, with most magnetic couplers developed around this configuration. Building on the design characteristics of the AUV-mounted magnetic coupler, the following section systematically reviews the current state of technological development in UIWPT magnetic coupling systems.

To enhance the comparability of different research results under non-uniform conditions, this paper introduces two standardized performance metrics, which are subsequently employed to compare the performance of different types of magnetic couplers. The first is the figure of merit (FoM), defined as follows:

where denotes the transfer efficiency, k is the coupling coefficient, and h represents the gap between the primary and secondary magnetic couplers. This metric simultaneously accounts for system efficiency, coupling strength, and transfer distance, thereby serving as a comprehensive indicator for evaluating the overall performance of magnetic couplers.

The second metric is the rated power density (RPD), defined as follows:

where denotes the output power of the system and W is the weight of the magnetic coupler on the AUV side. This metric evaluates the power transfer capability of the magnetic coupler per unit mass, highlighting its engineering relevance and practicality.

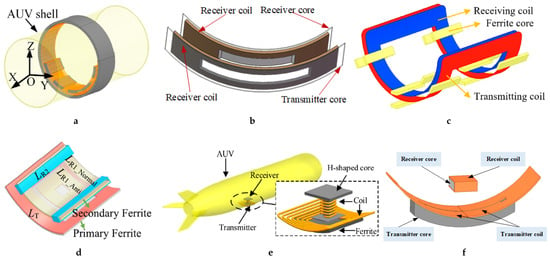

3.1.1. Non-Standard Core Magnetic Couplers

Non-standard core magnetic couplers adopt specially designed irregular magnetic core geometries to accommodate the specific structural constraints of the system. This configuration is primarily used in wireless power transfer systems that involve docking between AUVs and surface vessels or submarines. Based on differences in mechanical fixation methods, non-standard core configurations can be further classified into two major categories: concave–convex interlocking and base-alignment type.

The concave–convex interlocking magnetic coupler achieves precise alignment and power transfer via plug-in engagement between the primary and secondary magnetic cores. This configuration effectively mitigates disturbances caused by marine environmental factors, such as ocean current fluctuations, thereby enhancing the stability and reliability of the coupling process.

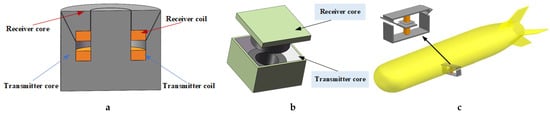

An early design proposed in [63] introduced a conical magnetic coupler mounted at the bow of the AUV, which docked with the subsea charging station via an insertion-based interface. This structure demonstrated excellent adaptability to ocean current fluctuations and achieved high power transfer efficiency. A self-locking magnetic coupler was proposed in [64], in which specially angled cutouts on the side poles of the magnetic core were used to increase the contact area. The central post on the transmitting side inserts into a groove on the receiving side, forming a self-locking engagement. This design significantly reduced the structural weight on the AUV side and enhanced resistance to disturbances caused by ocean currents (Figure 3a). A semi-enclosed magnetic coupler was developed in [65], offering higher power transmission capacity while effectively reducing electromagnetic radiation leakage. A clamping mechanism integrated into the housing ensures secure mechanical engagement. However, as the structure is mounted externally on the AUV, it may compromise the streamlined design and increase hydrodynamic drag (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Non-standard core magnetic couplers: (a) Zhou et al. [64]. (b) Cheng et al. [65]. (c) Sun et al. [49].

The base-alignment magnetic coupler emphasizes precise alignment between the bottom surfaces of the AUV-side and transmitter-side magnetic cores. This design conforms to the streamlined curvature of AUV hulls and typically requires auxiliary mechanical fixtures to ensure accurate positioning and stable fixation. Such a configuration significantly reduces magnetic leakage and improves power transfer efficiency.

Yan et al. [66] proposed a base-alignment magnetic coupler utilizing an EE-type magnetic core, in which the secondary and primary sides are positioned on the underside of the AUV and the subsea base station, respectively. The windings are arranged around the central magnetic limb, thereby improving the coupling coefficient and enhancing the power transfer capability of the system. In further research, Cai et al. [67] proposed an optimized -type magnetic core design, featuring a bottom surface with improved conformity to the curved profile of the AUV hull. Through parameter optimization and iterative refinement, simulation results under misalignment conditions demonstrated that the -type core exhibited significantly enhanced coupling performance compared to the conventional E-type core configuration. In addition, a study presented in [49] introduced an anchor-shaped magnetic core structure with an enlarged curved contact surface, significantly improving geometric conformity with the AUV hull. This design enhanced coupling performance and exhibited increased tolerance to angular misalignment (Figure 3c).

Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of the key parameters and performance metrics of UIWPT systems using non-standard core magnetic coupler designs, as reported in recent literature, and provides the corresponding FoM values. Despite their advantages, non-standard core magnetic coupler structures still encounter practical challenges, including limited conformity with the AUV’s external contours and constraints in the effective utilization of internal space, which constrain their wider adoption in system integration and engineering applications.

Table 1.

Comparison of system parameters for non-standard core magnetic couplers.

3.1.2. Circumferential Magnetic Couplers

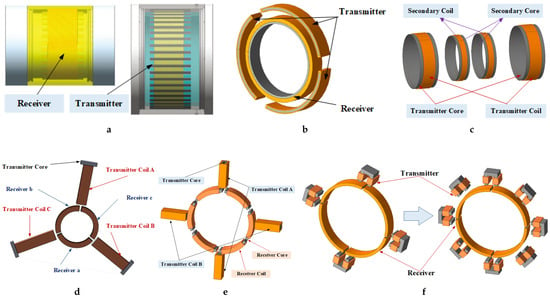

Circumferential magnetic couplers are designed and optimized based on guided docking configurations. On the AUV side, the magnetic coupling units are arranged circumferentially along the curved hull and installed within specific compartments. After docking, these units form uniform magnetic coupling with the corresponding magnetic coupling structure on the subsea base station. This configuration offers high tolerance to rotational misalignment. Based on structural form and design methodology, this type can be further categorized into two main subtypes: the solenoidal configuration and the arc-shaped coil configuration.

A coreless coaxial solenoidal magnetic coupler proposed by Lin et al. [68] achieves 360-degree misalignment tolerance through nested primary and secondary coils. However, this configuration exhibits limitations in both EMC and power transfer efficiency. In subsequent research, [51] introduced magnetic cores and a metallic shielding enclosure and further optimized the core dimensions as well as the spacing between the core and the shield (Figure 4a). These enhancements significantly improved the magnetic coupling efficiency and EMC of the system. In further work, [69,70] proposed a reconfigurable annular magnetic coupler with adjustable dimensions. The transmitter side consists of multiple movable arc segments that form a coaxial solenoidal configuration when unlocked. Once locked, the structure effectively reduces the gap between the primary and secondary coils, thereby enhancing overall magnetic coupling performance.

To address power fluctuations caused by rotational misalignment, Yu et al. [71] proposed a three-transmitter, single-receiver configuration. By implementing a segmented design with 120° phase differences, the system was able to maintain power fluctuations within 5.9% (Figure 4b). In addition, Liu [72] proposed a squirrel-cage structure featuring columnar magnetic cores, which are designed to conform to the streamlined hull of the AUV. By employing circumferentially symmetric windings, the design enhances the tolerance to both axial and rotational misalignments, while also satisfying the requirements for modularity and lightweight construction.

To enhance axial misalignment tolerance, Mostafa et al. [73] proposed a dual-solenoid split-type magnetic coupler. This design adopts co-directional current excitation and a shared magnetic core between the transmitting and receiving units. Compared to conventional coaxial solenoidal structures, it reduces the fluctuation of the coupling coefficient by 22% under an axial misalignment of 80 mm. Subsequently, Wang et al. [74] optimized the design by configuring the currents on the same-side coils to flow in the same direction, while those on the opposite-side coils flow in opposite directions. Nanocrystalline magnetic cores were embedded with each coil to enhance magnetic performance. Through multi-objective optimization, the system achieved mutual inductance fluctuation of less than 10% under ±100 mm axial misalignment and 360° rotational misalignment, with a power transfer efficiency exceeding 92% (Figure 4c).

To address the multidimensional misalignment challenges of AUVs under complex operating conditions, Xiong et al. [75] developed a configuration comprising dual coaxial split-type transmitting solenoids and a single receiving solenoid. Under combined misalignment conditions, including 50 mm axial offset, 25 mm air gap, and 15° rotational deviation, the system exhibited only a 4.83% variation in output power while maintaining an efficiency above 90%. To further enhance charging flexibility, Hasaba [76] designed a helical coil–encircling magnetic coupler. The transmitter consists of three serially connected coils, each with a diameter of 2 m and spaced 1 m apart. The receiving coil is wrapped around the outer surface of the AUV hull segment, enabling stable power transfer during low-speed transit within the transmitter coil array.

Kan et al. [77] proposed a three-phase wireless charging system comprising three symmetrically arranged transmitting and receiving units, aiming to reduce magnetic field interference affecting the central equipment. However, the system exhibits limited tolerance to rotational misalignment (Figure 4d). In [78], the triple-receiver configuration was optimized into a dual-receiver design with oppositely wound coil pairs, which significantly improved power stability within a rotational misalignment range of 120°. Subsequently, Yan et al. [79] further reduced the number of transmitters to two and designed a structure consisting of four arc-shaped receiver segments. Each segment consists of two layers of coils wound in opposite directions, wrapped around an arc-shaped ferrite core. By leveraging the principle of vertical magnetic flux decoupling, this design effectively improves transmission stability under conditions of rotational misalignment.

Building on this foundation, in [80], a receiving structure composed of six arc-shaped solenoids was developed, featuring four transmitter units arranged in decoupled pairs and a phase control strategy. This configuration significantly enhanced the system’s tolerance to both axial and rotational misalignments, achieving an output power fluctuation of less than 5% (Figure 4e). In subsequent research, a complementary magnetic field structure, consisting of a U-shaped bipolar transmitting coil and four unipolar arc-shaped receiving coils, was developed to maintain high output power stability under a rotational misalignment of 240 degrees [81]. In [82], the number of transmitters was expanded to eight, enabling efficient power transfer under full 360° rotational misalignment and varying load conditions (Figure 4f).

The arc-shaped coil magnetic coupler adopts an innovative spatial folded design to enable circumferential distribution along the AUV. This configuration maintains high coupling performance while significantly enhancing both EMC and misalignment tolerance. In [83,84], Mostafa proposed a fully circumferential, folded unipolar coil structure based on the Hall sensor principle. The design enables strong electromagnetic coupling and significantly reduces internal magnetic field leakage by employing an insertion-based docking mechanism on the secondary side. This design exhibits significant advantages over traditional coaxial solenoidal configurations.

A magnetic coupler tolerant to rotational misalignment with adjustable geometry was developed in [85], providing adaptability to AUVs of various sizes and offering high compatibility. Each of the transmitting and receiving units was composed of four arc-shaped coils connected in series. This design was later optimized into a dual-layer magnetic coupler on the receiving side, where each layer comprised four arc-shaped coils with a phase offset between them. Within a full 360° rotational range, the improved structure demonstrated high angular misalignment tolerance, maintaining stable output power and high transmission efficiency [86].

Figure 4.

Circumferential magnetic couplers: (a) Liu et al. [51]. (b) Yu et al. [71]. (c) Wang et al. [74]. (d) Kan et al. [77]. (e) Yan et al. [80]. (f) Chen et al. [81,82].

The system parameters of various types of circumferentially distributed magnetic couplers are compared, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of system parameters for circumferential magnetic couplers.

3.1.3. Locally Distributed Magnetic Couplers

Locally distributed magnetic couplers are also developed based on guided docking principles. On the AUV side, the coil configuration is non-circumferential and is optimized for integration with specific hull regions. Based on the integration approach with the AUV hull, magnetic couplers can be classified into the conformal type, which aligns with the AUV’s curved surface, and the compact space-efficient type, which fits within the internal cabin. Since AUV are structurally designed to minimize roll, and the underwater docking station provides stable attitude constraints during docking, the system’s tolerance for rotational misalignment is significantly reduced. Compared with circumferentially distributed structures, locally distributed designs enable effective power transfer while reducing size and weight, and they achieve higher power density. Moreover, this configuration reduces magnetic field interference at the center of the AUV, thereby improving EMC.

Xia et al. [87] proposed an asymmetric magnetic coupling configuration, consisting of a full circumferential solenoidal coil on the transmitter side and a locally distributed solenoidal coil on the receiver side. Compared with the conventional coaxial solenoidal coil, this configuration offers improved magnetic field convergence and reduced structural weight (Figure 5a). Furthermore, Cai [88] proposed a magnetic coupler using partially curved solenoidal coils to suppress EMC that affects the AUV’s internal electronic systems. In addition, the adoption of Fe-based nanocrystalline magnetic cores significantly reduces the system weight. Wang et al. [54] proposed an arc-shaped magnetic coupler, designed to conform precisely to the curved surface of the AUV hull. By optimizing design parameters via finite element analysis (FEA), the magnetic flux density at the AUV center was significantly reduced. Moreover, a quantitative loss analysis was conducted, providing a foundation for further structural optimization (Figure 5b). Subsequent studies optimized the magnetic core structure into a distributed ferrite configuration and applied a genetic algorithm to optimize key coil parameters such as the number of turns and coil width (Figure 5c). This approach achieved maximum structural weight reduction while maintaining a high magnetic coupling coefficient [89].

Figure 5.

Locally distributed magnetic couplers: (a) Xia et al. [87]. (b) Wang et al. [54]. (c) Lin et al. [89]. (d) Tang et al. [90]. (e) Qiao et al. [55]. (f) Cai et al. [57].

With arc-shaped transmitting coils that conform to the AUV’s curved hull now widely adopted, structural innovation on the receiver side has increasingly become a research focus. A dual-channel decoupled receiver, proposed in [90], integrates inner and outer reverse-bending coils with an external dual-solenoid structure, maintaining voltage fluctuation within 6% under a wide rotational misalignment of 50° and demonstrating excellent offset resistance (Figure 5d). Another study introduced an H-shaped ferrite core configuration, where the receiving coil is wound around vertically oriented magnetic cores [55]. This structure significantly enhances vertical magnetic flux coupling efficiency and exhibits better suitability for miniaturized and lightweight system designs compared to conventional arc-shaped configurations (Figure 5e). Building upon this, Wang et al. [91] further replaced the upper and lower sections of the H-shaped ferrite core with flexible magnetic materials to enhance structural bendability. Under conditions of 30° rotational misalignment and 30 mm axial offset, the design achieves mutual inductance fluctuation of less than 10% while also improving power density and significantly enhancing transmission stability.

To examine the performance differences between monopolar and bipolar structures, Yan et al. [92] conducted comparative experiments and demonstrated that although the bipolar structure is marginally heavier, it exhibits significantly lower levels of electromagnetic radiation than its monopolar counterpart, offering a clear advantage in minimizing interference with sensitive on-board equipment in AUVs. In addition, Zhao et al. [93] proposed a design in which the receiving side employs a curved receiving coil, while the transmitting side adopts a distributed forward-series configuration. A miniature internal compensation coil is integrated to enhance magnetic field uniformity, and the use of an arrayed ferrite core configuration effectively reduces the system’s overall weight. This design enables stable power transfer under multi-dimensional misalignment conditions.

The compact space-efficient magnetic coupler is exemplified by a receiving-end design proposed by Cai’s group, featuring an I-shaped ferrite core combined with a solenoidal coil. This miniaturized and structurally compact configuration provides a robust foundation for subsequent research and optimization. Building upon this receiving-end configuration, Cai’s team achieved further performance improvements through innovative transmitting-side designs. In [57], the bipolar arc-shaped transmitting coils are arranged with a centrally symmetric layout to maximize the coupling area, exhibiting good structural compatibility (Figure 5f). The double-layer arc-shaped coil employs a combination of three lower-layer coils and four upper-layer coils wound in an interlayer series-opposing manner. When coupled with precise excitation timing control, it generates a constant-amplitude traveling magnetic field with excellent tolerance to both axial and rotational misalignments [94]. The four-unit crossed transmitter, proposed in [95,96], operates in coordination with a dual-channel orthogonally decoupled receiver through a two-phase orthogonal coil array. The resulting large-area uniform magnetic field significantly improves the system’s misalignment tolerance. The curved four-transmitter scheme utilizes a paired arrangement of three equivalent sets of DD coils, combined with a two-phase orthogonal receiver design based on the sine–cosine coupling superposition principle. By employing hollow ferrite cores, the system achieves a weight reduction of 440g while maintaining excellent misalignment tolerance [97].

A comparison of different designs of locally distributed magnetic couplers is presented in Table 3. Given that such configurations emphasize lightweight characteristics on the AUV side, the RPD is also included to more intuitively reflect their performance advantages under weight-reduction constraints.

Table 3.

Comparison of system parameters for locally distributed magnetic couplers.

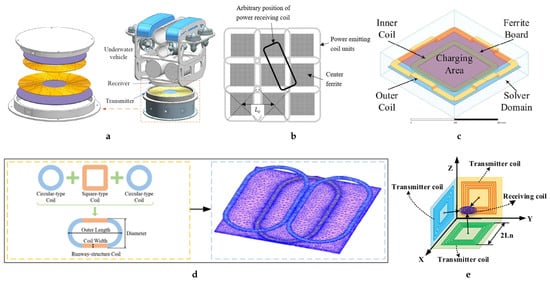

3.1.4. Planar Coil Magnetic Couplers

Planar coil magnetic couplers are characterized by their flattened structure and high spatial adaptability and are widely used in UIWPT systems for AUVs. They reduce the structural complexity of the AUV and demonstrate excellent adaptability across diverse docking scenarios, including platform-based and guided configurations.

In terms of structural optimization, Li et al. [98] developed a tank-shaped planar magnetic coupler specifically designed for 4000-meter deep-sea conditions. Experimental results confirmed its magnetic coupling performance under high hydrostatic pressure and axial misalignment, providing valuable guidance for the selection of enclosure materials and mechanical layout in deep-sea applications. Based on the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II), Liang et al. [99] conducted multi-objective optimization of planar coil design parameters for a frame-type AUV, thereby improving the system’s robustness to positional misalignments (Figure 6a). In [100], a coreless circular planar coil is used at the receiving end, while the transmitting side employs an inner–outer series-connected coil structure integrated with ferrite cores. This design effectively improves the uniformity of the magnetic field and enhances energy transfer efficiency, thereby increasing the system’s misalignment tolerance.

The platform-based docking method enhances the spatial adaptability and robustness of autonomous AUV charging. In [101], an omnidirectional charging platform was developed, featuring an arrayed planar transmitting coil system with an optimized spatial layout to support high-tolerance docking (Figure 6b). This system is further integrated with an electromagnetic anchoring mechanism to ensure accurate multi-dimensional positioning. To improve docking accuracy and system intelligence, SLAM-based navigation is combined with a visual servo docking system. By recognizing specific patterns on the platform, the system enables autonomous high-precision localization of the AUV, as demonstrated in [60]. In [102], a transmitting-end structure combining a raised annular coil and a coaxial central coil is proposed to improve platform generality and compatibility (Figure 6c). Meanwhile, a second-order Lagrangian-based nonlinear optimization algorithm is employed to optimize magnetic field strength and distribution uniformity. In addition, Cai et al. [103] integrated the advantages of circular and square coils by constructing a racetrack-shaped coil array. Utilizing a “DDQ” configuration, the system enables simultaneous multi-payload charging, thereby significantly enhancing platform operational efficiency (Figure 6d).

In recent years, many researchers have investigated extended configurations of planar coil-type magnetic couplers. Wen et al. [52] vertically embedded a dual-layer planar spiral coil into a specific cabin section of the AUV. Through guided docking with a solenoidal transmitter coil on the underwater base station, the system achieves stable coupling performance, effectively mitigating output fluctuations caused by axial misalignment. In [104], a dual-transmitter, single-receiver planar spiral coil structure was adopted. The receiving coil is mounted on the outer surface of the AUV stern and was magnetically aligned with the center of the dual transmitter coils during docking. This configuration reduces eddy current losses while maintaining stable power output and high transfer efficiency. In a more advanced study reported in [53], the planar spiral receiving coil was embedded into the AUV stern fin, while the transmitting coil was arranged in a solenoidal configuration to form a closed-loop magnetic field. This design not only significantly reduces electromagnetic leakage but also achieves overall system weight reduction through a coreless configuration.

Three-dimensional omnidirectional wireless power transfer systems for underwater applications have increasingly attracted research attention. In [105], the receiving side employs a conventional planar spiral coil, whereas the transmitting side features a spherical coil configuration composed of three mutually orthogonal circular loops. This design ensures non-interference among energy transfer channels, making it suitable for multi-directional and spatially distributed power delivery scenarios. Another study, reported in [106], utilizes an array of three orthogonally arranged square coils to achieve orientation-independent parallel power transfer to multiple AUVs (Figure 6e). Although such systems offer high spatial flexibility and relaxed docking accuracy requirements, improvements in power density and transmission efficiency are still needed.

Figure 6.

Planar coil magnetic couplers: (a) Liang et al. [99]. (b) Yang et al. [101]. (c) Lyu et al. [102]. (d) Cai et al. [103]. (e) Zhang et al. [106].

In Table 4, the system parameters of planar coil-type magnetic coupler designs reported in the literature are systematically compared.

Table 4.

Comparison of system parameters for planar coil magnetic couplers.

3.2. Application of Compensation Topologies

In UIWPT systems, the topology of the resonant compensation network plays a vital role in shaping overall system performance [107]. Accurate tuning of capacitance and inductance parameters enables the system to achieve the following key functions:

- Facilitating dynamic reactive power compensation to improve energy efficiency;

- Mitigating electrical stress on power devices to ensure reliable long-term operation;

- Maintaining stable CC/CV output under varying loads;

- Enabling accurate zero-voltage switching(ZVS)/zero-current switching (ZCS) operation to reduce switching losses and thermal impact.

Therefore, in practical applications, the selection of a compensation topology must comprehensively account for multiple factors, including operating frequency characteristics, load variation range, current waveform distortion, and the requirements for achieving soft-switching conditions [108]. Currently, compensation topologies in UIWPT systems are broadly categorized into low-order and high-order types. In addition, a variety of specialized topologies have been developed to address diverse application demands. The following presents a systematic analysis of the characteristics, application scenarios, and recent research advances in these compensation topologies, along with a comparative evaluation of their performance features.

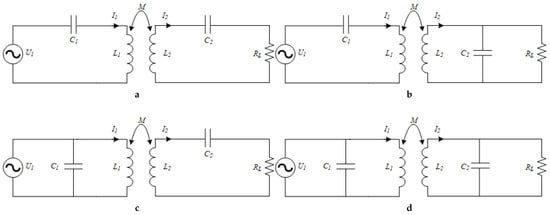

3.2.1. Low-Order Compensation Topologies

Low-order compensation topologies are widely employed in UIWPT systems owing to their structural simplicity and cost-effectiveness. This category mainly comprises four fundamental configurations: series–series (SS), series–parallel (SP), parallel–series (PS), and parallel–parallel (PP), as illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Low-order compensation topologies: (a) SS. (b) SP. (c) PS. (d) PP.

The series–series (SS) topology offers substantial advantages in AUV wireless charging applications, as its resonant frequency remains unaffected by variations in coupling coefficient and load [76,88,93]. Thanks to its structural simplicity, it reliably delivers constant current (CC) output, making it particularly suitable for battery charging applications. However, under light-load or no-load conditions, excessive current may circulate on the primary side, causing abnormal voltage rise and elevated current stress, which may ultimately damage power switching devices. Therefore, the SS topology is better suited to high-power circuit architectures that employ advanced control techniques.

The series–parallel (SP) topology demonstrates enhanced stability under varying load conditions, rendering it particularly suitable for complex and dynamic load environments [64,87]. However, when the receiving side is open-circuited, the primary side may display resonant short-circuit behavior, thus requiring reliable current-limiting protection circuits. As reported in [68], comparative studies reveal that the SP topology offers markedly improved output voltage stability compared to the SS topology under dynamic load conditions.

The parallel–series (PS) topology offers high transmission efficiency and favorable power factor characteristics under conditions of low coupling coefficient and wide load variation [109]. However, it necessitates a CC source input to suppress voltage transients, thereby partially constraining its practical deployment.

In contrast, the parallel–parallel (PP) topology is infrequently adopted in practical engineering applications due to multiple technical constraints, including poor power factor, excessive secondary-side voltage, and stringent current source requirements [107].

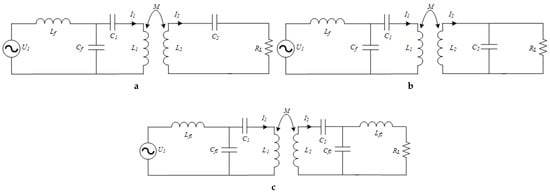

3.2.2. High-Order Compensation Topologies

Conventional low-order resonant networks possess inherent limitations when applied to specific operational scenarios. High-order compensation topologies, through the integration of additional resonant components, offer substantial improvements in system performance and robustness. In recent years, such topologies have attracted growing interest and have been increasingly applied in UIWPT systems for AUVs. Miniaturization and lightweight construction remain critical design objectives in the development of AUV wireless charging systems. Given the stringent volume and weight constraints of AUV platforms, topological configurations with simplified secondary-side structures are generally regarded as more practical. Due to their relatively complex secondary-side configurations, S-LCC and P-LCC compensation topologies have limited applicability in UIWPT systems for AUVs.

By comparison, the LCC-S and LCC-P topologies exhibit superior weight reduction performance in AUV applications. Among these, the LCC-S topology has emerged as a mainstream solution in contemporary AUV wireless charging systems due to its compact structure and high operational stability. Notably, an optimized LCC-P topology can achieve performance comparable to that of the standard LCC configuration while significantly reducing voltage and current stress on switching devices. Using a CC operation with optimal efficiency as the design objective, Qiao et al. [110] developed a nonlinear programming model and employed a genetic algorithm to optimize system parameters. The proposed system achieved an output power of 802.3 W and a transmission efficiency of 91.12% under seawater conditions.

The LCC–LCC topology provides high design flexibility, enabling effective suppression of inverter current stress while enhancing misalignment tolerance and load variation. However, its requirement for numerous compensation components increases system cost and physical volume. Consequently, this topology is mainly employed in specialized scenarios, such as bidirectional charging for AUVs. Yan et al. [92] demonstrated via comparative analysis that, under identical operating conditions, the LCC–LCC topology achieves transmission efficiency comparable to that of the SS topology while producing coil current waveforms closer to an ideal sine wave, thereby offering significantly improved waveform quality. Figure 8 presents commonly used high-order compensation topologies in AUV-based UIWPT systems.

Figure 8.

High-order compensation topologies: (a) LCC-S. (b) LCC-P. (c) LCC-LCC.

3.2.3. Single-Sided Compensation Topologies

Single-sided compensation topologies can be divided into two main types based on the configuration of resonant components: primary-side uncompensated and secondary-side uncompensated structures. By selectively omitting the resonant network on one side, these topologies simplify the overall system design while achieving performance optimization for specific application scenarios.

Primary-side uncompensated topologies, which omit resonant components on the transmitter side, significantly reduce system complexity and implementation cost. Among these, the N–S topology serves as a representative example. In [111], an open-loop control strategy without feedback was employed, demonstrating distinct advantages. This type of topology exhibits low sensitivity to load variations, effectively avoids frequency bifurcation, and greatly simplifies parameter design. These characteristics make it particularly suitable for operational environments with constrained underwater communication.

Secondary-side uncompensated topologies are primarily designed to meet the lightweight and compactness requirements of AUV systems. By eliminating compensation components on the receiving side, these configurations significantly reduce overall system weight and volume. The LCC–N topology employs an innovative switched-capacitor control strategy on the primary side, combined with precise parameter optimization, to achieve stable output current under varying coupling coefficients and load conditions [112]. Notably, the LLC–N topology proposed in [113] combines fundamental harmonic analysis with time-domain analysis to optimize primary-side circuit parameters. This approach effectively mitigates current stress and significantly enhances overall system reliability.

3.2.4. Reconfigurable and Hybrid Compensation Topologies

In response to the challenges posed by increasingly complex and dynamic operating environments, reconfigurable and hybrid compensation topologies have undergone notable advancements in recent years. These configurations enhance system adaptability and performance by enabling real-time structural reconfiguration or synergistic operation of multiple compensation schemes.

In the domain of reconfigurable topologies, Li et al. [114] proposed a topology-switching strategy between the LCC and -type networks, utilizing an impedance self-adaptive tuning mechanism. Under conditions of low coupling efficiency and reduced battery voltage, this approach achieves a 1.7-fold improvement in power transfer capability compared to the conventional LCC–LCC topology, with system efficiency reaching 93.1%. Another noteworthy study, presented in [115], realized dynamic reconfiguration between SS and SP topologies via a switching matrix, enabling the system to flexibly alternate between power transfer and high-speed data communication modes.

Within the domain of hybrid compensation topologies, the dual LCC-S hybrid configuration enables self-adaptive operational mode switching through structural innovation, without requiring any active switching elements. Tang et al. [116] experimentally verified that the proposed topology maintains output voltage fluctuations within 8% over a wide coupling coefficient range of 0.2 to 0.6, achieves a sustained transmission efficiency exceeding 89% in air, and consistently operates under ZVS throughout the entire operating range. To address the specific requirements of multidimensional crossed magnetic couplers, Cai et al. [96] developed a dual LCC-S hybrid compensation strategy. By jointly optimizing the inductance parameters, the system’s fault tolerance under misalignment conditions was significantly enhanced.

3.3. Design of Control Strategies

Power control technologies in UIWPT systems constitute a core component for achieving stable operation, high-efficiency power transfer, and accurate power regulation [117]. However, the complex and dynamic nature of the marine environment presents several critical challenges to power control systems, primarily reflected in the following aspects:

- Seawater imposes substantial attenuation of high-frequency electromagnetic waves, thereby degrading communication reliability;

- Coil misalignment induced by ocean current disturbances significantly reduces magnetic coupling efficiency;

- Parasitic effects introduced by the marine environment contribute to strong system nonlinearity;

- Dynamic load variations during the charging process hinder stable power regulation.

From a system architecture perspective, control strategies in UIWPT systems can be classified along two key dimensions. Based on the control target, they include inverter modulation [118], compensation parameter tuning, rectifier control [39], and DC–DC converter regulation [119]. According to the control location, strategies can be further categorized as primary-side control [120], secondary-side control [121], dual-side independent control (without communication) [112], and dual-side coordinated control [122]. To address the unique challenges of AUV wireless charging systems, the following content systematically reviews recent research progress on control strategies, with a focus on practical engineering implementation.

3.3.1. Enhancement of Misalignment Tolerance

In marine environments, turbulence and ocean current often cause relative displacement between the primary and secondary coils, leading to dynamic variations in the coupling coefficient and fluctuations in reflected impedance, which significantly degrade power transfer performance. To mitigate this challenge, researchers have introduced a variety of innovative adaptive control strategies.

Fan et al. [123] optimized the pulse-width modulation (PWM) strategy and employed FPGA-based real-time inverter output control, effectively suppressing harmonic distortion. With a radial misalignment of 30%, the system’s transmission efficiency decreased by only 15%. In [124], a closed-loop CC control method incorporating variable secondary-side inductance was proposed. This approach achieved an efficiency of no less than 87% under a horizontal misalignment of 47% and a vertical misalignment of 140% while significantly reducing reliance on primary–secondary communication. Similarly, Luo et al. [125] developed an optimal efficiency model under variable gap conditions by dynamically adjusting the MOSFET duty cycle, demonstrating enhanced system reliability.

Fu et al. [126] proposed an intelligent control algorithm that integrates a backpropagation (BP) neural network with non-singular terminal sliding mode control (NTSMC) for multi-coil transmission systems. The method dynamically predicts the secondary coil position and optimizes the associated magnetic field distribution. Experimental results indicate that the system maintains a transmission efficiency exceeding 78.5% and exhibits high stability within an 80 mm misalignment range. To address rotational misalignment caused by ocean currents, Zhang et al. [127] proposed a mutual inductance estimation and angular identification algorithm based on primary-side current characteristics. This algorithm enables real-time feedback to the AUV master control system for attitude correction, thereby ensuring optimal power transfer operation.

3.3.2. Identification and Modeling of Dynamic Parameters

In UIWPT systems, the seawater environment introduces not only substantial eddy current losses but also a complex network of parasitic elements, such as stray capacitance and inductance. These factors pose significant challenges to the accuracy of conventional modeling methods in representing the system’s dynamic behavior. Meanwhile, the high attenuation of underwater communication restricts real-time parameter exchange between the primary and secondary sides, making single-sided parameter identification essential for precise control.

For system modeling, Xia et al. [128] developed a data-driven approach based on a simplified refined instrumental variable algorithm, integrated with model predictive control (MPC). This method significantly improves the system’s dynamic response and outperforms conventional PID control under varying operating conditions. In [129], a Buck–Boost converter was implemented on the secondary side, and a multi-strategy nonlinear recursive instrumental matrix estimation (RIME) algorithm was employed to dynamically identify the mutual inductance and load parameters, achieving relative errors below 1% and 6.8%, respectively.

In [130], an improved particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm was proposed for LCC-S-based high-order compensated UIWPT systems. Under three-dimensional misalignment and dynamic load variations, the algorithm achieved mutual inductance identification error within 2.5% and maintained output power fluctuations below 5%. In addition, Liu [131] conducted an in-depth investigation into the influence of seawater-induced eddy current effects on system modeling and proposed a multi-parameter joint identification strategy that accounts for key variables such as mutual inductance, load resistance, and stray components. In [132], the multi-parameter identification problem was formulated as an objective function optimization task. A weighted-adjusted adaptive moment estimation (Adam-W) algorithm was employed to enable dynamic parameter identification using only primary-side information, providing an effective solution for control in non-communication scenarios.

The integration of machine learning techniques has brought notable progress in parameter identification. Orekan et al. [133] proposed a method for dynamically adjusting DC–DC converter parameters through real-time estimation of the secondary side coupling coefficient. Under misalignment conditions, this approach maintains a transmission efficiency above 85%. These innovative approaches effectively address the challenges of system modeling and parameter identification in marine environments, offering a reliable solution for power control in non-communication scenarios.

3.3.3. Maximum Efficiency Tracking and Optimization

The power transfer efficiency of UIWPT systems is influenced by various factors, including coil misalignment, eddy current loss, and load variability. Consequently, maximum efficiency point tracking (MEPT) and system-wide efficiency optimization have emerged as critical areas of research [134].

Wang et al. [135] implemented a variable-step perturb-and-observe algorithm on the primary side to perform power factor correction (PFC) and achieve MEPT. In combination with a semi-active rectifier combined with PI-based control on the secondary side, the system supports constant-current charging without requiring a communication link, thereby significantly simplifying the overall architecture. Zheng et al. [122] proposed an adaptive frequency tracking control (AFTC) technique that dynamically adjusts the operating frequency to match the system’s resonant frequency, thereby maintaining continuous operation at the maximum efficiency point.

To optimize system efficiency under dynamic operating conditions, Zheng [136] integrated neural networks with PID control to implement MEPT based on the learned optimal mapping between output voltage and coupling coefficient. By enabling real-time adaptive regulation of the DC–DC converter, the system maintains high energy transfer efficiency despite variations in load and coupling conditions. In [137], spiral-structured negative permeability metamaterials were incorporated into the system alongside a Buck–Boost impedance converter and an optimal impedance tracking strategy, thereby effectively minimizing reactive power loss.

Li [112] proposed a hybrid control strategy combining switched-capacitor (SCC) technology with frequency modulation for the LCC-N compensation topology. The system demonstrated superior performance, maintaining output current fluctuation within 4.47% and achieving an efficiency greater than 87% across a wide coupling coefficient range (0.3–0.54). Similarly, Zhang et al. [85] developed a dynamically tuned SCC technique capable of adaptively matching varying self-inductance values, offering an innovative solution for highly compatible AUV charging platforms. In addition, by optimizing the secondary-side compensation parameters and phase-shift control, Wang [138] effectively reduced eddy current loss, resulting in a 4–5% improvement in overall system efficiency.

3.3.4. Regulation of Power Output and Battery Charging

To meet the charging requirements of AUV lithium battery packs, UIWPT systems must overcome the challenge of output stability under dynamic load conditions and implement a dual-stage constant current–constant voltage (CC–CV) charging strategy in accordance with the electrochemical characteristics of the battery. In recent years, several notable technological advances have been achieved in this area.

For output stabilization, Yang et al. [139] implemented a high-power-density boost switched-capacitor (SC) converter on the secondary side, combined with a nonlinear voltage-oriented one-cycle control (VOCC) technique, which effectively suppresses input voltage fluctuations and load disturbances in real time. In the context of dual-side LCC compensation networks, Siroos et al. [140] conducted a comparative study of different control strategies. The results indicate that the DC–DC converter-based approach provides superior output voltage stability and minimal fluctuation amplitude across a wide range of coupling coefficients and power levels, outperforming both PWM-controlled inverters and Z-source converters.

For battery charging management, Zheng [122] proposed a voltage–current dual-loop control architecture based on a Buck converter, enabling seamless transitions between constant-current (CC) and constant-voltage (CV) charging modes. In [141], a cooperative control scheme was developed by combining resonant frequency tracking with digital phase-locked loop (PLL) phase-shift control. By utilizing wireless communication to transmit electrical parameters, the system dynamically adjusts the phase-shift angle to maintain constant-current and constant-voltage output. Under step changes in load, this method achieves a 5% improvement in system efficiency. These technological advancements not only improve energy transfer stability under dynamic load conditions but also offer a new approach to the integrated design of AUV energy management systems.

3.4. Implementation of Simultaneous Power and Data Transfer

During wireless power transfer operations, AUVs are required to simultaneously support multiple modes of data communications, including charging control feedback, task command exchange, and mission data transmission [142]. Stable and efficient communication between the AUV and the underwater base station is a fundamental prerequisite for realizing a closed-loop control architecture in UIWPT systems. Traditionally, power and data transfer have been implemented using wet-mate connectors and dedicated electro-optical hybrid cables [143]. However, with the growing deployment of UIWPT technologies, ensuring reliable and high-speed data transmission in complex underwater environments has become a critical technical challenge [144].

Contemporary underwater wireless communication technologies mainly include acoustic [145], optical [146,147], radio frequency (RF) [148,149], and the emerging MI communication. A performance comparison of these methods is provided in Table 5. The first three approaches typically require dedicated wireless communication modules to enable data transmission. In contrast, MI communication enables the simultaneous transmission of power and data, offering advantages in compact integration, reduced communication latency, and improved environmental adaptability. These features make it particularly suitable for complex underwater operations involving AUVs. Based on the coil configuration for data transmission, MI communication systems are generally classified into two categories: decoupled architectures employing independent coils and multiplexed architectures that utilize shared coils for both power and data. Each architecture offers distinct advantages in system integration and is tailored to different underwater application scenarios.

Table 5.

Performance comparison of underwater wireless communication methods.

3.4.1. Dedicated Wireless Communication Systems

As the dominant method for long-range underwater transmission, acoustic communication utilizes the favorable propagation characteristics of sound waves in water, playing an irreplaceable role in extended-range AUV positioning and cooperative operations. A typical Ultra-Short Baseline (USBL) positioning system enables precise relative localization using acoustic signals, but its limited inherent bandwidth constrains its effectiveness in high-frequency control tasks and large-volume data transmission [150,151]. Guida et al. [22] proposed an acoustically integrated simultaneous data and power transfer system, incorporating a bidirectional acoustic modem to enable coordinated transmission of communication and ultrasonic wireless power, offering a novel energy solution for distributed underwater sensor networks. However, due to the inherently low efficiency of ultrasonic energy transfer, this technology remains at an exploratory stage with restricted practical adoption.

Optical communication technology, known for ultra-high data rates and extremely low latency, offers an ideal solution for short-range underwater communication. Based on this technology, Pontbriand [152] achieved full-duplex communication between AUVs and seafloor nodes over distances of up to 150 m, with data rates reaching 10 Mbps, while near-field transmission within 5 m exceeded 400 Mbps and required less stringent directional alignment. Visible Light Communication (VLC), as an emerging technology, shows significant promise in interference resistance and device miniaturization due to the unique advantages of LED light sources [153]. However, VLC requires a highly linear transmission path and is highly sensitive to water turbidity and ambient light interference, which greatly compromises its reliability in complex underwater environments.

RF communication technology supports high-speed data transmission using standard protocols such as Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, and it has been widely investigated for underwater applications. However, it faces major limitations due to the high conductivity of seawater, which causes severe attenuation of electromagnetic signals, especially in high-frequency bands. Granger et al. [154] conducted experiments on wireless charging and communication post AUV docking, integrating a Wi-Fi module with the magnetic coupler for power transfer. Communication was achieved using the 802.11b Wi-Fi protocol. In [155], a dual-RF adapter architecture combined with a glass fiber-reinforced polymer enclosure enabled data transmission at 3.5 Mbps across a 2 mm gap. In [144], the optimized antenna design of a 2.4 GHz wireless communication system enabled the AUV to uplink 700 MB of data at 3.1 MBps, even under a 7° roll angle. For deep-sea applications, Shi [156] proposed a non-intrusive docking structure that employs magnetic attachment and epoxy encapsulation. This design enabled simultaneous power and data transfer, delivering 130 W at 70% efficiency and supporting 73 Mbps full-duplex communication, offering a valuable reference for the practical implementation of underwater RF communication.

3.4.2. Decoupled Magnetic Induction Communication Systems

MI communication transmits data via alternating magnetic fields between compact coupled coils, typically operating in the MHz frequency range [157]. Compared to GHz-range RF signals, MI experiences significantly lower attenuation in water, offering improved communication stability and microsecond-level latency, effectively supporting real-time closed-loop control during AUV wireless charging.

The decoupled transmission scheme employing independent coils achieves electromagnetic decoupling of power and data channels through precise magnetic field orthogonalization. This configuration enables efficient and simultaneous transfer of power and data without signal interference. Unlike approaches that incorporate dedicated wireless communication modules, this method facilitates deep integration of power and data transfer at the system architecture level. It provides advantages such as improved spatial efficiency, enhanced synchronization accuracy, and greater environmental adaptability. Notably, this architecture represents one of the earliest solutions proposed for integrated MI communication.

In [158], an innovative overlapped coil structure was proposed, where a bipolar flux coil generates a horizontal magnetic field for power transfer, while a unipolar flux coil establishes a vertical magnetic field for data transmission. The receiver decouples the two channels via spatial magnetic field separation, enabling independent reception of power and data. This architecture significantly mitigates interference from the power channel on the communication signal and enhances system compactness and lightweight integration. Additionally, a band-stop filter is embedded in the data channel to suppress power crosstalk, thereby enabling high-quality full-duplex communication without compromising power transfer efficiency.

Da et al. [159] adopted a DDQ coil configuration, where two D-shaped coils handle power transfer and a dedicated Q coil supports data communication. Based on this architecture, a seawater-adapted communication system was developed. Experimental results show that the system can achieve Mbps-level data rates under high power transfer conditions, although full-duplex communication remains unrealized. Subsequent research extended this system to bidirectional power transfer scenarios, where pulse synchronization techniques were applied to optimize the phase alignment between forward and reverse power flow. In conjunction with PLL control, this method significantly reduced interference from the power channel to the data signal [160]. Notably, Xia et al. [128] proposed an alternative setup that utilizes DD coils for data transmission and assigns the Q coil for power delivery. However, due to limited magnetic coupling, the system exhibited relatively low data throughput.

To address interference from the power channel to the communication signal, Zhang [161] conducted an in-depth analysis of the magnetic field distribution of the DD coils and strategically positioned a circular data coil in a region of low field intensity while maintaining orthogonality with the power flux. This configuration enabled miniaturization of the communication unit and demonstrated strong resilience to axial misalignment, although the achievable data rate remains limited. To further enhance the isolation between power and data channels, Li et al. [162] proposed a hybrid magnetic induction–electric field coupling architecture in which power transfer is conducted via conventional inductive coupling, while data communication is achieved through single-capacitor-based electric field transmission. This hybrid architecture not only enables full-duplex communication but also significantly extends the effective transmission range, ensuring continuous information exchange throughout all phases of AUV charging—before, during, and after power transfer. In addition, the spherical orthogonal coil assembly designed in [163] achieved complete three-dimensional magnetic field decoupling, enabling fully independent transmission of power and data. This system was successfully applied to wireless energy supply and data collection between AUVs and distributed underwater sensor networks, demonstrating strong potential for complex subsea operations.

To compare the overall performance of different schemes under non-uniform experimental conditions, this paper defines a standardized performance metric termed the Communication Energy Efficiency Index (CEI), which is intended to jointly evaluate the capability of simultaneous power and data transfer. Its definition is given as follows:

In this expression, denotes the power transfer efficiency, represents the output power, and R refers to the data transfer rate. The CEI value is positively correlated with these three parameters, and a higher value indicates superior overall performance in both power transfer and data transfer. In the following analysis, this metric will be employed to systematically evaluate and compare different schemes.

A parameter comparison of decoupled transfer systems using independent coils with the corresponding CEI values is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Parameter comparison of decoupled transfer systems using independent coils.

3.4.3. Multiplexed Magnetic Induction Communication Systems

The multiplexed shared-coil transmission scheme enables simultaneous power and data transfer by superimposing high-frequency communication signals onto the power transfer coils. In contrast to decoupled transmission systems employing dedicated communication coils, this approach eliminates the need for dedicated communication coils, offering notable advantages in system integration, compactness, and weight reduction. Depending on different multiplexing methods and coil configuration, existing studies can be broadly divided into two categories: partial-coil multiplexing and single-coil time–frequency multiplexing.

The partial-coil multiplexing scheme typically utilizes a designated portion of the power transfer coil, such as the outermost or innermost winding, for data communication. This architecture integrates communication capabilities while preserving high power transfer efficiency; however, it requires precise coil alignment to ensure stable system performance. Wang et al. [164] proposed an innovative dual-sided LLCC compensation topology in which the data carrier is loaded onto the outermost turn of the power coil to facilitate full-duplex communication via frequency division multiplexing (FDM). By incorporating frequency shift keying (FSK), the system reduces voltage stress and improves both interference immunity and communication robustness. To further enhance spectral efficiency, Li [165] introduced orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM), enabling high-speed full-duplex data transmission over a planar coil structure and significantly improving the system’s communication capacity.

Zeng et al. [166] designed a transmitting coil consisting of two oppositely wound spiral loops paired with a specially shaped arc-shaped receiving coil to generate a multidirectional magnetic field distribution. This configuration enables simultaneous power delivery and data feedback operations for multiple AUVs. A multi-objective genetic algorithm was utilized to optimize the parameters of the coupling structure, achieving a trade-off between transmission efficiency and system weight. In addition, the hybrid injection communication scheme based on the LCC-S topology achieves data injection via transformer coupling, demonstrating strong system compatibility.

For communication channel design, Li et al. [167] proposed a method for directly injecting and extracting information carriers at the tap point of the coupled coil. By eliminating the limitations of conventional resonant structures and employing minimum shift keying (MSK) modulation together with coherent demodulation, this approach simplifies system design while significantly enhancing bandwidth utilization and data throughput. In [168], an enhanced dual-channel full-duplex architecture was proposed, enabling priority-based transmission of control commands and sensing data by differentially injecting carriers at distinct positions along the coupling coil. The accompanying reduced-order high-precision model offered effective guidance for communication channel design, thereby enhancing the engineering applicability of the overall system. Table 7 summarizes the performance comparison of various partial-coil multiplexing schemes in shared-coil MI communication systems.

Table 7.