Acoustic Scattering Characteristics of Micropterus salmoides Using a Combined Kirchhoff Ray-Mode Model and In Situ Measurements

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

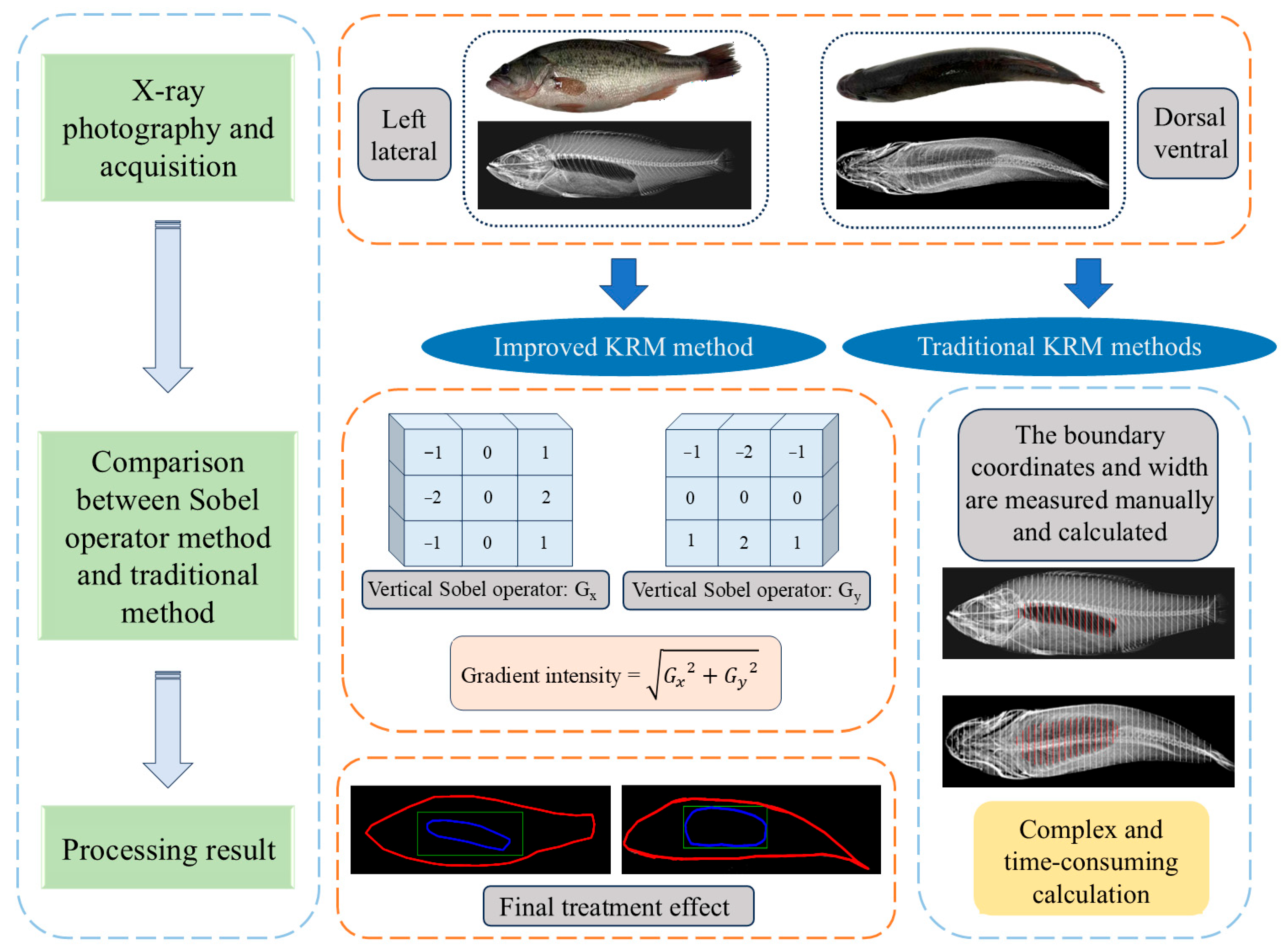

2.1. Integration of Edge Detection Technology with the Kirchhoff Ray-Mode Model

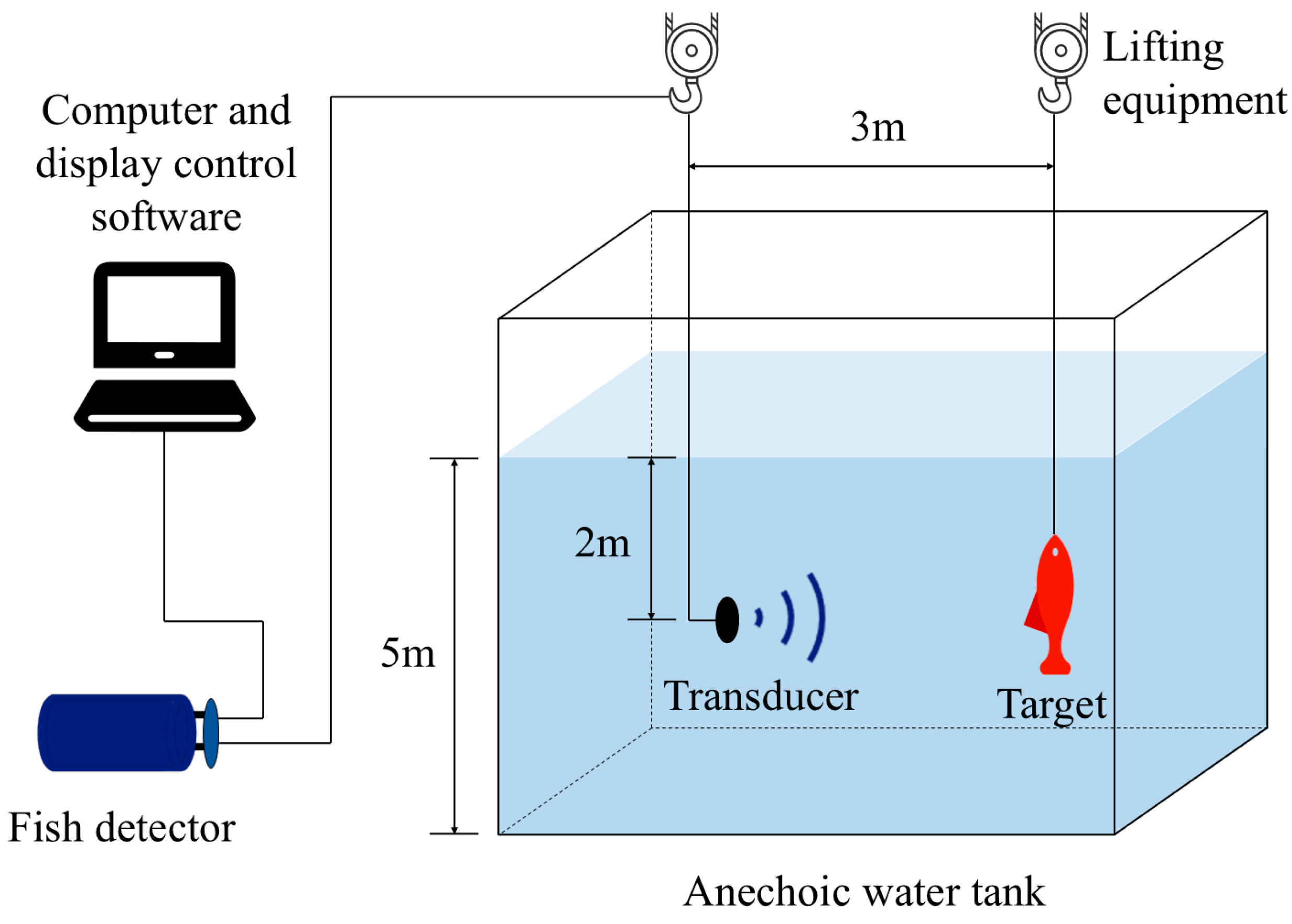

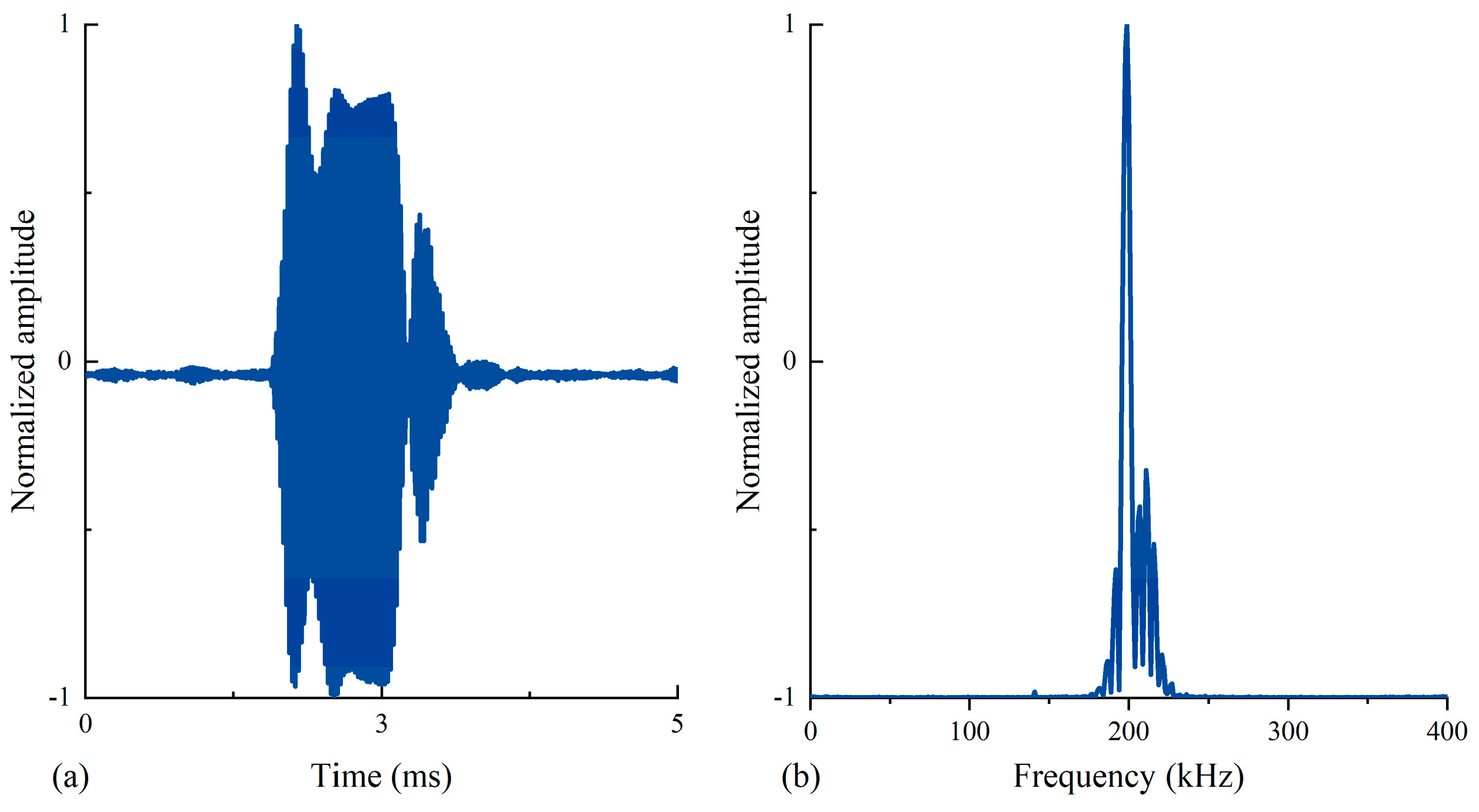

2.2. In Situ Measurement of Target Strength

2.3. Sample Acquisition

2.4. In Situ Measurement Method

2.5. Edge Detection Processing and Model Construction

- (1)

- Edge Detection and Separation. Utilizing edge detection algorithms, the X-ray images were processed in software to precisely separate the fish body and swim bladder regions. This step involved identifying high-gradient areas within the images to extract the boundary contours of both the fish body and the swim bladder.

- (2)

- Model Segmentation and Cross-Section Extraction. The separated fish body and swim bladder models were divided into equally spaced cross-sections. Each cross-section segment was uniformly distributed to ensure data continuity and representativeness. By recording the boundary coordinate points and length information of each cross-section, the structural features of the swim bladder and fish body were accurately depicted.

- (3)

- Target Strength Calculation and Acoustic Scattering Analysis. Based on Equations (1)–(8), the target strength of each fish was calculated. Furthermore, acoustic scattering characteristics were analyzed to evaluate the reflection and scattering effects of fish bodies on sound waves.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphological Information

3.2. Acoustic Scattering Characteristics of Micropterus salmoides

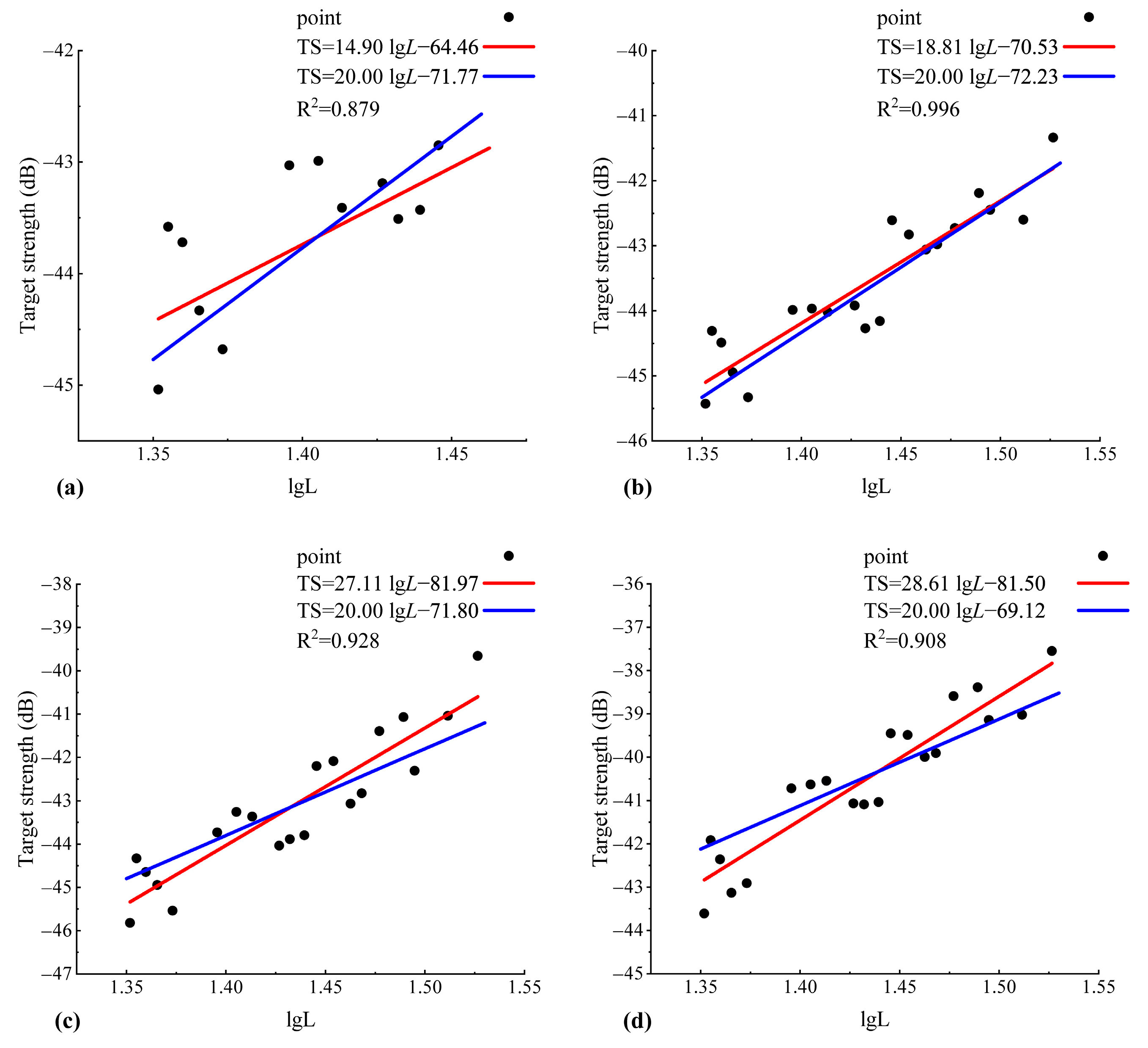

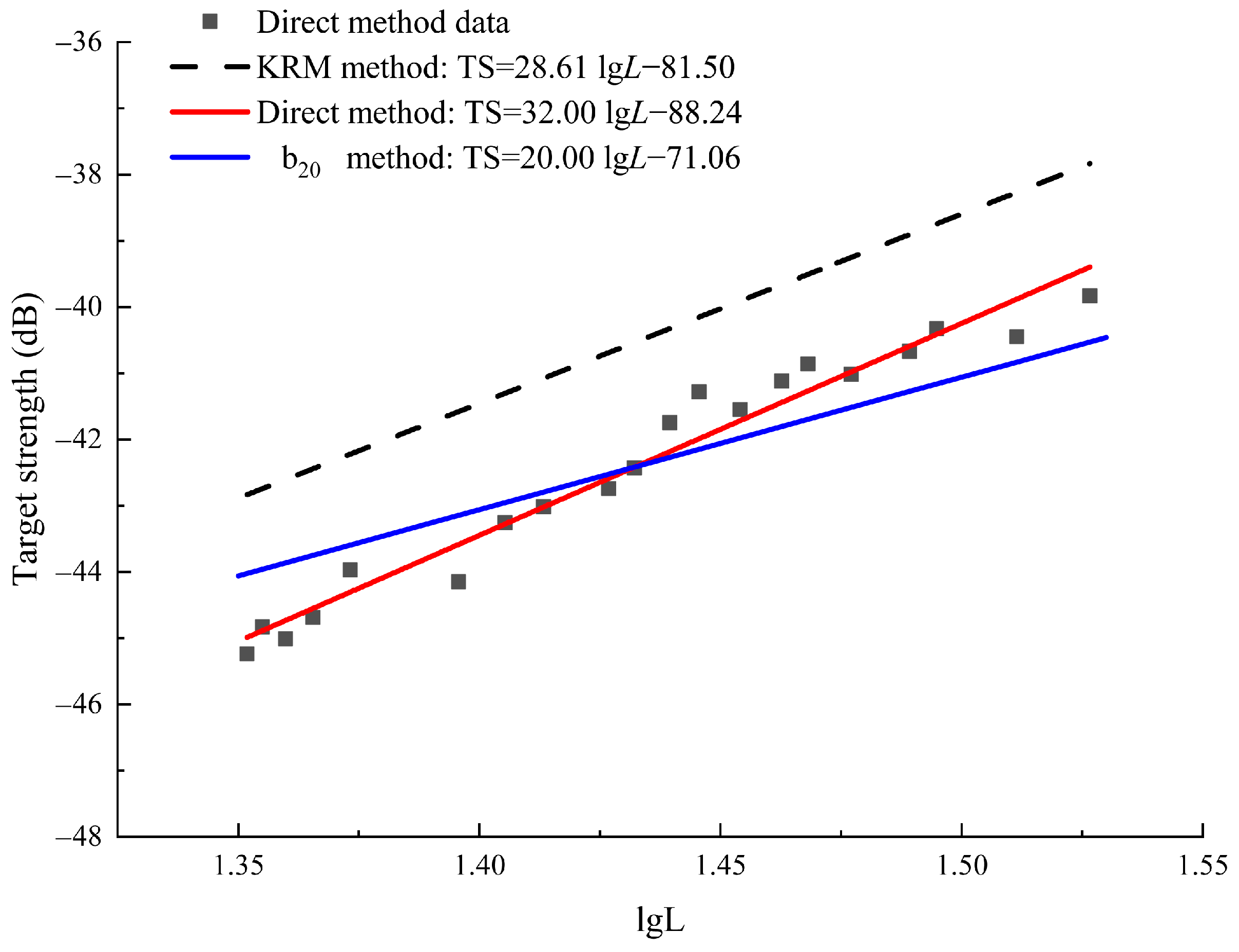

3.2.1. Relationship Between Target Strength and Body Length

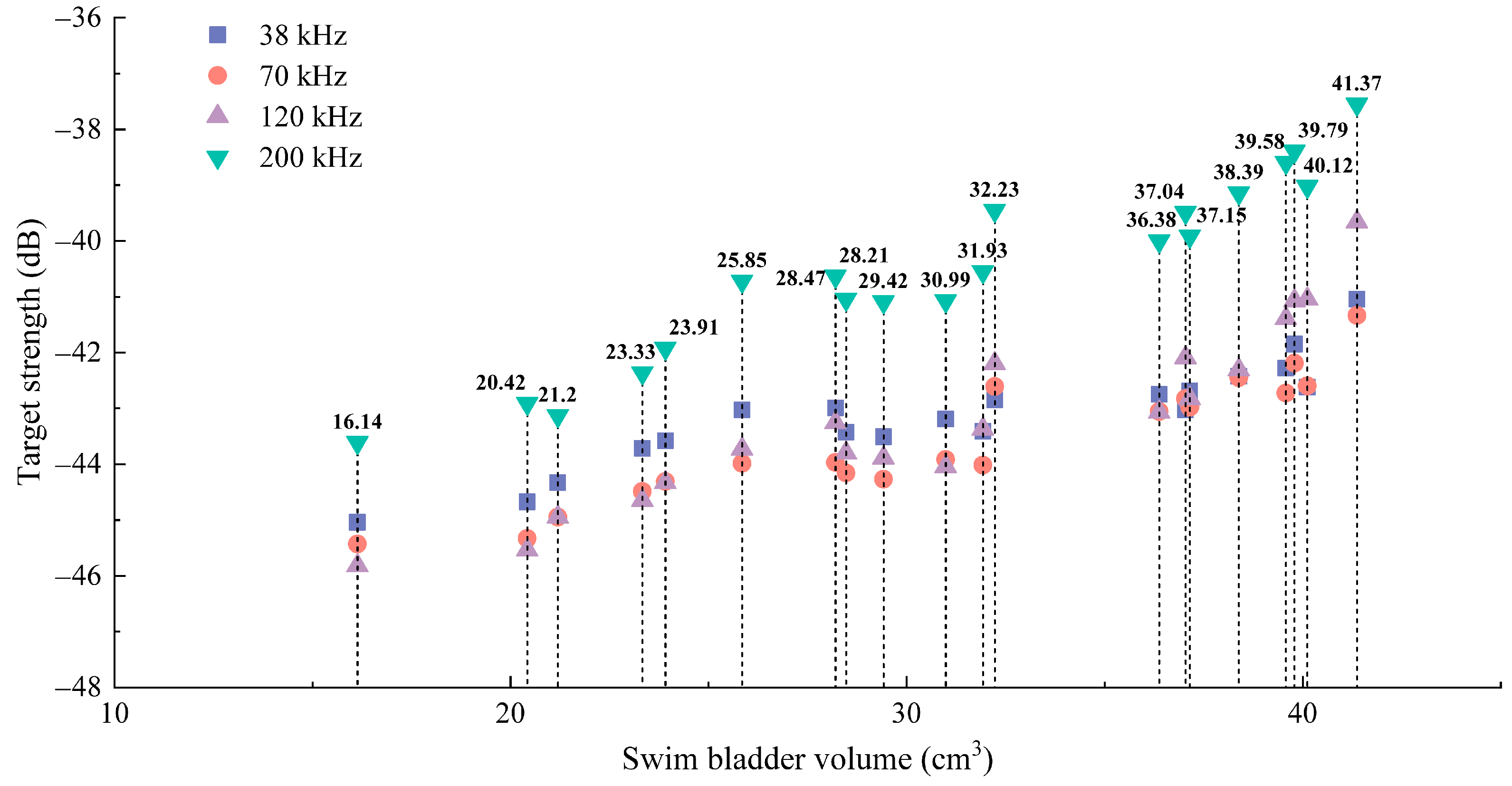

3.2.2. Relationship Between Target Strength and Swim Bladder Volume

3.2.3. Underwater Acoustic Data Processing and Analysis

3.2.4. Other Factors Affecting Target Strength

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dai, X.; Zhu, S.; Ye, J.; Xu, Q.; Yi, T.; Wu, C.; Wang, B.; Luo, K.; Gao, W. Effects of Dietary Enzymatically Treated Artemisia annua L. in Low Fish Meal Diet on Growth, Antioxidation, Metabolism and Intestinal Health of Micropterus salmoides. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 33, 101843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Hu, J.; Li, X.; Sun, Q.; Tan, X.; You, C.; Dong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, M. Dietary Black Soldier Fly Oil Enhances Growth Performance, Flesh Quality, and Health Status of Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides). Anim. Nutr. 2024, 18, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Chen, H.; Liu, M.; Zhong, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wu, C.; Wang, S.; Zhao, C.; et al. Current Status and Application of Largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) Germplasm Resources. Reprod. Breed. 2024, 4, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, J.; Song, H.; Zhu, T.; Lei, C.; Du, J.; Li, S. Osmoregulation and Physiological Response of Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) Juvenile to Different Salinity Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, J.; Pu, D.; Li, P.; Wei, X.; Li, D.; Gao, L.; Zhai, X.; Zhao, C.; Du, Y. Comparative Evaluation of Nutritional Quality and Flavor Characteristics for Micropterus salmoides Muscle in Different Aquaculture Systems. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 101787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, M.; Guo, W.; Deng, S.; Liu, H.; Yao, L. Isolation and Identification of a New Strain Micropterus salmoides Rhabdovirus (MSRV) from Largemouth Bass Micropterus salmoides in China. Aquaculture 2023, 572, 739538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, M.; Pedersen, G.; Daase, M.; Berge, J.; Venables, E.; Basedow, S.L.; Falk-Petersen, S.; Langbehn, T.J.; Jensen, J.; Camus, L.; et al. Broadband Acoustic Classification of Atlantic Cod, Polar Cod, and Northern Shrimp in in Situ Mesocosm Experiments. Fish. Res. 2025, 286, 107388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattler, K.R.; Looby, A.; Côté, I.M.; Cox, K.D. The Sound of Recovery: Integrating Acoustics into Fish Status Assessments and Recovery Strategies. Biol. Conserv. 2025, 310, 111339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.; Lowry, M.B.; Fowler, A.M.; Taylor, M.D. Hydroacoustic Surveys Reveal the Distribution of Mid-Water Fish Around Two Artificial Reef Designs in Temperate Australia. Fish. Res. 2023, 257, 106509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenkoehler, W.; Long, J.M.; Gary, R.; Snow, R.A.; Schooley, J.D.; Bruckerhoff, L.A.; Lonsinger, R.C. Viability of Side-Scan Sonar to Enumerate Paddlefish, a Large Pelagic Freshwater Fish, in Rivers and Reservoirs. Fish. Res. 2023, 261, 106639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladino, A.; Pérez-Arjona, I.; Espinosa, V.; Chillarón, M.; Vidal, V.; Godinho, L.M.; Moreno, G.; Boyra, G. Role of Material Properties in Acoustical Target Strength: Insights from Two Species Lacking a Swimbladder. Fish. Res. 2024, 270, 106895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J.; Jansen, T.; Fenwick, A.J.; Fernandes, P.G. A New In-Situ Method to Estimate Fish Target Strength Reveals High Variability in Broadband Measurements. Fish. Res. 2023, 261, 106611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautureau, C.; Goulon, C.; Guillard, J. In Situ TS Detections Using Two Generations of Echo-Sounder, EK60 and EK80: The Continuity of Fishery Acoustic Data in Lakes. Fish. Res. 2022, 249, 106237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, W.; Fan, J.; Zhao, K.; Zhou, F.; Tan, L. Modeling of Bistatic Scattering from an Underwater Non-Penetrable Target Using a Kirchhoff Approximation Method. Def. Technol. 2022, 18, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Yuan, X.; Lam, C.-T.; Im, S.-K. Low-Complexity DQED: Advancing Dual-Scenario Quantum Edge Detection for Enhanced Image Analysis. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2025, 127, 110545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Duanmu, L.; Zhai, Z.J.; Wang, Z. Application and Improvement of Canny Edge-Detection Algorithm for Exterior Wall Hollowing Detection Using Infrared Thermal Images. Energy Build. 2022, 274, 112421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Jiang, Z.; Kamruzzaman, M.M. Radar Remote Sensing Image Retrieval Algorithm Based on Improved Sobel Operator. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2020, 71, 102720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wu, Y.; Qu, C.; Hu, H.; Lee, T.; Lin, S.; Zhang, J.; Lam, K.S.; Wang, A. Protocol for Vision Transformer-Based Evaluation of Drug Potency Using Images Processed by an Optimized Sobel Operator. STAR Protoc. 2023, 4, 102259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng-o, T.; Chaikan, P. High Performance and Energy Efficient Sobel Edge Detection. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2021, 87, 104368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, K.G. Importance of the Swimbladder in Acoustic Scattering by Fish: A Comparison of Gadoid and Mackerel Target Strengths. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1980, 67, 2084–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuma, H.; Sawada, K.; Takao, Y.; Miyashita, K.; Aoki, I. Swimbladder condition and target strength of myctophid fish in the temperate zone of the Northwest Pacific. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2010, 67, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Hao, Y.; Duan, Y. Nonintrusive Methods for Biomass Estimation in Aquaculture with Emphasis on Fish: A Review. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 1390–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, B.S.; Stubbs, A.R. Measurements of the Acoustic Target Strengths of Fish in Dorsal Aspect, Including Swimbladder Resonance. J. Sound Vib. 1971, 15, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating frequency | 200 kHz | Input voltage | DC10–14 V |

| Detection range | 1.0–200 m | Power consumption | 30 W |

| Pulse type | CW and LFM | Communication mode | ethernet network |

| Pulse duration | 0.1–10 ms | Data transfer rate | 100 Mbps |

| Maximum emission SL | 210 dB | Materials | Stainless steel |

| Beam type | split beam | Dynamic range | ±40 dB |

| Frame rate | 0.01–30 frames/second | Operating system | Windows |

| No. | Body Length (cm) | Body Width (cm) | Body Height (cm) | Bladder Length (cm) | Bladder Width (cm) | Bladder Height (cm) | Badder Volume (cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22.48 | 3.76 | 6.55 | 8.15 | 2.44 | 1.55 | 16.14 |

| 2 | 22.65 | 4.68 | 7.73 | 8.51 | 2.87 | 1.87 | 23.91 |

| 3 | 22.90 | 4.61 | 8.05 | 8.66 | 2.68 | 1.92 | 23.33 |

| 4 | 23.20 | 4.27 | 7.09 | 8.50 | 2.87 | 1.66 | 21.20 |

| 5 | 23.62 | 3.95 | 6.88 | 8.56 | 2.56 | 1.78 | 20.42 |

| 6 | 24.87 | 4.74 | 8.19 | 9.04 | 3.15 | 2.05 | 30.57 |

| 7 | 25.43 | 4.96 | 8.32 | 8.61 | 2.98 | 2.10 | 28.21 |

| 8 | 25.90 | 5.01 | 8.30 | 9.49 | 3.06 | 2.10 | 31.93 |

| 9 | 26.72 | 4.81 | 8.17 | 9.68 | 3.20 | 1.91 | 30.99 |

| 10 | 27.05 | 4.75 | 7.90 | 9.80 | 3.05 | 1.88 | 29.42 |

| 11 | 27.51 | 4.60 | 8.01 | 9.57 | 2.99 | 1.90 | 28.47 |

| 12 | 27.90 | 5.06 | 8.72 | 9.98 | 3.23 | 2.15 | 36.29 |

| 13 | 28.45 | 5.12 | 8.84 | 9.85 | 3.17 | 2.28 | 37.28 |

| 14 | 29.02 | 5.14 | 8.86 | 9.93 | 3.38 | 2.07 | 36.38 |

| 15 | 29.39 | 5.12 | 8.92 | 9.88 | 3.42 | 2.10 | 37.15 |

| 16 | 30.00 | 5.20 | 8.78 | 9.90 | 3.32 | 2.30 | 39.58 |

| 17 | 30.85 | 5.27 | 9.05 | 9.92 | 3.36 | 2.28 | 39.79 |

| 18 | 31.25 | 5.15 | 8.96 | 10.01 | 3.27 | 2.24 | 38.39 |

| 19 | 32.47 | 5.34 | 9.12 | 10.08 | 3.32 | 2.29 | 40.12 |

| 20 | 33.62 | 5.23 | 9.10 | 10.12 | 3.38 | 2.31 | 41.37 |

| average | 27.26 | 4.84 | 8.27 | 9.36 | 3.07 | 2.03 | 31.10 |

| No. | Body Length (cm) | Average of Target Strength (dB) | b20 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38 kHz | 70 kHz | 120 kHz | 200 kHz | 38 kHz | 70 kHz | 120 kHz | 200 kHz | ||

| 1 | 22.48 | −45.04 | −45.43 | −45.82 | −43.61 | −72.08 | −72.47 | −72.86 | −70.65 |

| 2 | 22.65 | −43.58 | −44.31 | −44.33 | −41.92 | −70.68 | −71.41 | −71.43 | −69.02 |

| 3 | 22.90 | −43.72 | −44.49 | −44.65 | −42.36 | −70.92 | −71.69 | −71.85 | −69.56 |

| 4 | 23.20 | −44.33 | −44.95 | −44.95 | −43.13 | −71.64 | −72.26 | −72.26 | −70.44 |

| 5 | 23.62 | −44.68 | −45.33 | −45.54 | −42.91 | −72.15 | −72.80 | −73.01 | −70.38 |

| 6 | 24.87 | −43.03 | −43.99 | −43.73 | −40.72 | −70.94 | −71.90 | −71.64 | −68.63 |

| 7 | 25.43 | −42.99 | −43.97 | −43.26 | −40.63 | −71.10 | −72.08 | −71.37 | −68.74 |

| 8 | 25.90 | −43.41 | −44.02 | −43.37 | −40.55 | −71.68 | −72.29 | −71.64 | −68.82 |

| 9 | 26.72 | −43.19 | −43.92 | −44.04 | −41.07 | −71.73 | −72.46 | −72.58 | −69.61 |

| 10 | 27.05 | −43.51 | −44.27 | −43.89 | −41.09 | −72.15 | −72.91 | −72.53 | −69.73 |

| 11 | 27.51 | −43.43 | −44.16 | −43.80 | −41.04 | −72.22 | −72.95 | −72.59 | −69.83 |

| 12 | 27.90 | −42.85 | −42.61 | −42.20 | −39.45 | −71.76 | −71.52 | −71.11 | −68.36 |

| 13 | 28.45 | −43.03 | −42.83 | −42.09 | −39.49 | −72.11 | −71.91 | −71.17 | −68.57 |

| 14 | 29.02 | −42.75 | −43.06 | −43.07 | −40.00 | −72.00 | −72.31 | −72.32 | −69.25 |

| 15 | 29.39 | −42.69 | −42.98 | −42.83 | −39.91 | −72.05 | −72.34 | −72.19 | −69.27 |

| 16 | 30.00 | −42.28 | −42.73 | −41.39 | −38.59 | −71.82 | −72.27 | −70.93 | −68.13 |

| 17 | 30.85 | −41.85 | −42.19 | −41.07 | −38.39 | −71.64 | −71.98 | −70.86 | −68.18 |

| 18 | 31.25 | −42.43 | −42.45 | −42.31 | −39.14 | −72.33 | −72.35 | −72.21 | −69.04 |

| 19 | 32.47 | −42.62 | −42.60 | −41.04 | −39.02 | −72.85 | −72.83 | −71.27 | −69.25 |

| 20 | 33.62 | −41.04 | −41.34 | −39.66 | −37.55 | −71.57 | −71.87 | −70.19 | −68.08 |

| Average | 27.26 | −43.12 | −43.58 | −43.15 | −40.53 | −71.77 | −72.23 | −71.80 | −69.12 |

| No. | Body Length (cm) | Average of Target Strength (dB) | b20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22.48 | −45.24 | −72.28 |

| 2 | 22.65 | −44.83 | −71.93 |

| 3 | 22.90 | −45.01 | −72.21 |

| 4 | 23.20 | −44.69 | −72.00 |

| 5 | 23.62 | −43.97 | −71.44 |

| 6 | 24.87 | −44.15 | −72.06 |

| 7 | 25.43 | −43.26 | −71.37 |

| 8 | 25.90 | −43.02 | −71.29 |

| 9 | 26.72 | −42.74 | −71.28 |

| 10 | 27.05 | −42.43 | −71.07 |

| 11 | 27.51 | −41.75 | −70.53 |

| 12 | 27.90 | −41.28 | −70.19 |

| 13 | 28.45 | −41.55 | −70.63 |

| 14 | 29.02 | −41.12 | −70.37 |

| 15 | 29.39 | −40.86 | −70.22 |

| 16 | 30.00 | −41.02 | −70.56 |

| 17 | 30.85 | −40.67 | −70.46 |

| 18 | 31.25 | −40.33 | −70.23 |

| 19 | 32.47 | −40.45 | −70.68 |

| 20 | 33.62 | −39.83 | −70.36 |

| Average | 27.26 | −42.41 | −71.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, W.; Sheng, M.; Guo, Z.; Wang, M. Acoustic Scattering Characteristics of Micropterus salmoides Using a Combined Kirchhoff Ray-Mode Model and In Situ Measurements. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13101856

Wang W, Sheng M, Guo Z, Wang M. Acoustic Scattering Characteristics of Micropterus salmoides Using a Combined Kirchhoff Ray-Mode Model and In Situ Measurements. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(10):1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13101856

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Wenzhuo, Meiping Sheng, Zhiwei Guo, and Minqing Wang. 2025. "Acoustic Scattering Characteristics of Micropterus salmoides Using a Combined Kirchhoff Ray-Mode Model and In Situ Measurements" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 10: 1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13101856

APA StyleWang, W., Sheng, M., Guo, Z., & Wang, M. (2025). Acoustic Scattering Characteristics of Micropterus salmoides Using a Combined Kirchhoff Ray-Mode Model and In Situ Measurements. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(10), 1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13101856