Abstract

Accurate target identification of UAV (Unmanned Aerial Vehicle)-captured images is a prerequisite for maritime rescue and maritime surveillance. However, UAV-captured images pose several challenges, such as complex maritime backgrounds, tiny targets, and crowded scenes. To reduce the impact of these challenges on target recognition, we propose an efficient maritime rescue network (EMR-YOLO) for recognizing images captured by UAVs. In the proposed network, the DRC2f (Dilated Reparam-based Channel-to-Pixel) module is first designed by the Dilated Reparam Block to effectively increase the receptive field, reduce the number of parameters, and improve feature extraction capability. Then, the ADOWN downsampling module is used to mitigate fine-grained information loss, thereby improving the efficiency and performance of the model. Finally, CASPPF (Coordinate Attention-based Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast) is designed by fusing CA (Coordinate Attention) and SPPF (Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast), which effectively enhances the feature representation and spatial information integration ability, making the model more accurate and robust when dealing with complex scenes. Experimental results on the AFO dataset show that, compared with the YOLOv8s network, the EMR-YOLO network improves the mAP (mean average precision) and mAP50 by 4.7% and 9.2%, respectively, while reducing the number of parameters and computation by 22.5% and 18.7%, respectively. Overall, the use of UAVs to capture images and deep learning for maritime target recognition for maritime rescue and surveillance improves rescue efficiency and safety.

1. Introduction

Maritime transport is one of the most important modes of transport worldwide. According to UNCTAD (https://unctad.org/rmt2022, accessed on 24 April 2024), in 2021, approximately 80% of global trade in products was transported via the sea. Because of the high volume of maritime activity, accidents at sea are inevitable. According to the European Maritime Safety Agency’s (EMSA) [1] Annual Overview of Maritime Casualties and Accidents 2023, 2510 maritime casualties and accidents occurred in 2022, with 597 people injured. Maritime accidents have a serious impact on the country’s economic development, marine ecosystems, and crew members’ lives, causing significant property damage and fatalities. As a result, research and development of maritime rescue identification technology is critical for monitoring ships at sea and detecting people overboard promptly to reduce the impact of maritime accidents.

Traditional maritime rescue [2] techniques primarily include radar search, sonar identification, radio communication, and visual search. These methods are inefficient, provide limited coverage, are affected by the natural environment, and pose a high risk. To address these issues, integrating deep learning-based UAV target recognition algorithms on ships at sea can provide critical information in ship path planning, such as the location of individuals overboard, obstacles at sea, and maritime traffic conditions. Intelligent planning of ship pathways can be achieved through the collaboration between UAVs and ships to enhance the efficiency and safety of ship navigation at sea, with enormous potential and advantages in sectors such as maritime search and rescue [3], maritime surveillance [4], and so on. UAVs have greater flexibility and a wider field of view than traditional rescue methods, which not only save resources but also improve rescue efficiency and contribute significantly to maritime safety. Our research is dedicated to enhancing the accuracy of maritime target detection using UAV-captured imagery.

In recent years, numerous researchers have used deep learning to identify maritime targets. However, the application of maritime target recognition algorithms to UAVs may face the following issues. First, in real maritime environments, there are frequently complex situations such as sea fog, low light at night, and exposure, which result in blurred or distorted images. Second, UAVs fly at high altitudes and record images with a large number of small targets, resulting in a single type of feature. Third, the UAV’s lack of internal storage space and computational resources might cause issues such as model deployment difficulties and poor real-time processing capabilities. Consequently, this study focuses on how to use advanced target identification algorithms and techniques for maritime UAVs to improve the accuracy and efficiency of maritime rescue and provide more reliable support for it.

Traditional target identification algorithms have seriously affected efficiency because of the cumbersome identification process, resulting in the gradual fading out of mainstream application areas. Target recognition algorithms based on deep learning gradually demonstrate their advantages. Among these, the YOLO [5] series, as a typical representative of single-stage target recognition, is widely used in UAV target recognition [6] due to its characteristics of real-time recognition, fewer parameters, and less computation. In this paper, we present an improved version of the YOLOv8 model named EMR-YOLO, which achieves higher accuracy and faster identification speed than those of the original YOLOv8s model, making it well suited for detecting targets in images captured by UAVs.

To achieve efficient maritime target identification on UAV-captured images for maritime rescue and maritime surveillance, our contributions are as follows:

- EMR-YOLO is proposed as a target identification method for maritime rescue. Experimental results show that the method performs better than existing state-of-the-art methods.

- In the proposed network, the DRC2f module is designed by improving the C2f module of the backbone network using a Dilated Reparam Block to better capture global information and enhance the feature extraction capability.

- The ADOWN downsampling module is used to obtain shallow feature information, enabling a more complete extraction of feature information.

- To avoid loss of feature information, CASPPF is designed by fusing the CA and SPPF, which effectively enhances the information fusion of different layers of features, making the model more accurate in dealing with complex scenes.

2. Related Work

2.1. Current State of Research on Maritime Rescue Identification

In recent years, algorithms for maritime rescue identification based on deep learning have become more popular. Earlier, Ran [7] proposed marine target identification based on multispectral analysis to address rescue challenges in complex sea areas and extract information about people in the water by analyzing the visible and near-infrared spectra. In 2019, Zheng [8] proposed using humans and UAVs to assist in searches in complex environments, significantly reducing the time required for human rescuers to locate targets. In 2021, Leira et al. [9] investigated a multi-target identification system for search UAVs, where multiple targets can be detected and localized in real time by one search UAV. With advancements in target identification technology, the YOLO series has gradually become the mainstream algorithm for maritime target identification. In 2021, Sun et al. [10] proposed a USV sea surface target identification algorithm based on an improved feature fusion network with YOLOv4 as the baseline. This method achieved an inference speed of 36 FPS and the capability of detecting sea surface objects of varying sizes in complex weather conditions. In 2022, Bai [11] improved the YOLOV5s algorithm and proposed a lightweight network to search for people overboard. In 2023, Yang [12] improved the YOLOV5s maritime target identification algorithm by effectively balancing the accuracy and efficiency of target identification. Zhang [13] proposed an improved algorithm for maritime SAR identification in 2023 by making improvements to YOLOv7. This improved algorithm reduced the effects of low light and sunlight reflection on the identification model and increased its robustness. However, the large size of the model and its slow identification speed make it unsuitable for UAV deployment. Despite the wide application of target identification algorithms in UAV images, UAV-captured images at sea still face challenges such as small targets and complex backgrounds.

The efficiency of the rescue process at sea is significantly improved by the combination of the drone and the ship, with the information recognized by the drone being passed on to the ship. With their advantages of good maneuverability, wide search range, and fast positioning, UAVs can achieve high-precision identification of people, ships, and obstacles in the water, thereby improving the accuracy and safety of ship path planning, and increasing the success rate of rescuing people in distress. Therefore, deep learning-based target identification methods offer improved potential for marine search and rescue.

2.2. Current State of Deep Learning-Based Target Identification Research

Geoffrey Hinton [14] introduced the concept of deep learning in 2006, and the discipline of deep learning rapidly evolved over the next decade, with researchers beginning to apply it to solve picture problems. In 2012, Hinton’s team [15] developed the AlexNet architecture, a model utilizing convolutional neural networks. This model significantly established CNNs as a prominent tool in the field of computer vision. Currently, deep learning-based target identification algorithms are classified as either two-stage or single-stage depending on the presence or absence of a separate region selection module.

R-CNN [16] is a target identification technique introduced by Girshick et al. in 2013. It is a two-stage algorithm utilizing convolutional neural networks for target detection. This algorithm employs a candidate region approach, resulting in a notable improvement in accuracy. Nevertheless, the R-CNN algorithm suffers from a clear drawback: The presence of overlapping target candidate regions causes computational redundancy during the CNN feature extraction phase, leading to reduced detection speed. As convolutional neural networks continue to evolve. Girshick proposed the Fast R-CNN [17] technique in 2015, which uses a fully connected layer and an RoI pooling layer to speed up the detection process and anticipate and locate the target, thus improving processing efficiency. However, the inclusion of the fully connected layer increases the computational parameters, which is unfavorable for hardware deployment. In the same year, Ren et al. introduced the Faster R-CNN [18] technique, which addresses the issue of time-consuming candidate area selection by utilizing the Region Proposal Network (RPN). This improvement enhanced the real-time target identification capability. However, there remains computational redundancy in the detector step. Although the two-stage target detection algorithm has higher accuracy, its lengthy candidate frame generation time and complex model structure limit its real-time detection capabilities and make it unsuitable for practical applications.

Single-stage target detection algorithms differ from two-stage algorithms in that they can regress directly on the input image to compute the prediction frame and target category in real time. The most representative algorithms are the SSD [19] and YOLO [5] series. In 2016, Redmon et al. [5] published the first YOLO algorithm, YOLOv1. This approach employs a single neural network to forecast the category probabilities and bounding box coordinates of the entire image simultaneously, allowing for end-to-end optimization. However, the algorithm has significant limits in dense scenes. In 2017, Redmon et al. [20] proposed the YOLOv2 algorithm, which improves YOLOv1 by replacing the AlexNet feature extraction network with DarkNet19 [21], thereby improving model performance. In 2018, Redmon et al. [22] proposed the YOLOv3 algorithm using DarkNet53 as a feature extraction network, along with FPN [23] (Feature Pyramid Network), to fuse features through a top-down unidirectional in-formation flow path. Furthermore, detection is performed on the three feature layers obtained through feature fusion to effectively detect objects of varying sizes and improve model robustness. In 2020, Bochkovskiy et al. [24] proposed the YOLOv4 algorithm, which employs CSPDarknet53 as a feature extraction network that maintains a high inference speed while maintaining high accuracy to better handle complex scenes. Then, in 2022, Li et al. proposed YOLOv6 [25], which significantly improves model performance by utilizing SimSPPF and SIOU, as well as by constructing a Rep-PAN structure, allowing the model to perform multi-scale fusion while reasoning at high speed. In 2023, Wang proposed the YOLOV7 [26] algorithm, which uses an efficient ELAN network architecture to obtain rich feature information and improve the model’s identification accuracy. Due to its effective trade-off between speed and precision, the single-stage target detection algorithm is suitable for implementation in real-world applications.

Compared to the two-stage target detection algorithm, the single-stage target detection method may treat the detection task as a regression problem, allowing for end-to-end training with the benefits of quick detection speed, small model size, and low computation cost. Therefore, in this paper, a single-stage detection algorithm is used to realize the detection of UAV-captured images.

2.3. Principles of the YOLOv8 Algorithm

YOLOv8 is an enhanced iteration of YOLOv5, which was made publicly available by Ultralytics (https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics, accessed on 20 June 2024) in January 2023. YOLOv8 has five versions based on network depth and width: YOLOv8n, YOLOv8s, YOLOv8m, YOLOv8l, and YOLOv8x. To strike a balance between accuracy and model size, in this article, YOLOv8s serves as the baseline model for detecting images acquired by maritime UAVs.

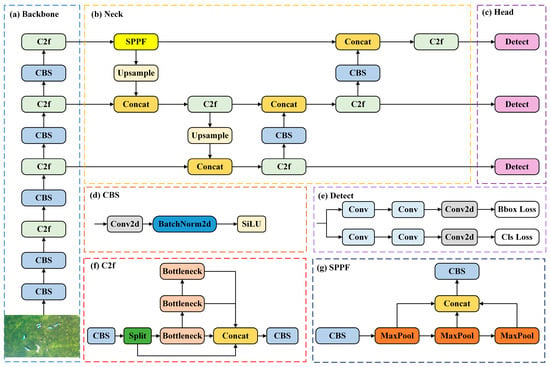

In Figure 1, the YOLOv8 network architecture is illustrated. Following data preprocessing to resize the input image to 640 × 640 × 3, data enhancement is implemented on the image. The network is divided into three main components: the backbone, neck, and detection head.

Figure 1.

Structure of YOLOv8.

Backbone network: As its backbone network, YOLOv8 makes use of Darknet-53. Five downsamplings are performed on the input feature map to generate five distinct scale features ranging from P1 to P5. In relation to the C3 structure of YOLOv5 and the ELAN structure of YOLOv7, YOLOv8 develops a novel C2f structure. This enables the integration of features at various scales, which improves the network’s representation of the features and enriches the gradient flow information. The CBS module applies convolution, BN, and SiLU activation function operations on the input information to get the output results.

Neck network: To establish the backbone and neck connection, the neck network employs the Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast (SPPF) module to transform feature maps of variable size into feature vectors of consistent size. SPPF reduces computation and increases speed in comparison to the spatial pyramid pooling (SPP) [27] structure by progressively connecting the three largest pooling layers. At the same time, to improve the model’s identification performance, the Neck section employs the PANet [28] architecture, which enhances the network’s capability of fusing features of targets with varying scaling scales and is utilized to propagate feature information and merge features of different levels.

Head network: Detection and classification are separated using a decoupled header structure. Additionally, the Anchor-Free algorithm replaces the previous Anchor-Based algorithm, which significantly decreases computation time and improves speed without compromising accuracy.

3. Methodology

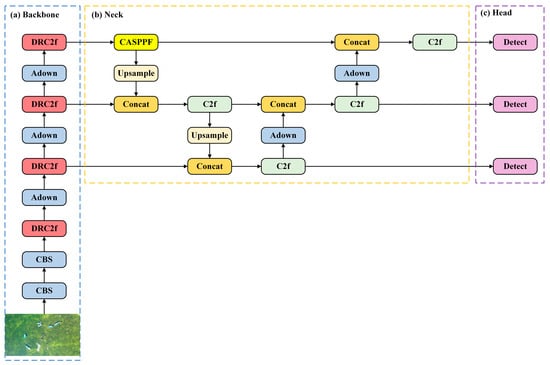

This section provides a full discussion of the Efficient Maritime Rescue Identification (EMR-YOLO) method. Figure 2 depicts the network structure diagram of EMR-YOLO. First, to improve its feature extraction and capture global information, we use the Dilated Reparam Block [29] to improve the C2f module in the backbone of the model. Subsequently, the downsampling method used in the networking is changed from Convolutional Module to Adown to reduce the problem of information loss due to downsampling. In addition, the CA attention mechanism [30] is integrated into the SPPF module, which can suppress the background information in the feature map, effectively enhancing the recognition and improving the accuracy and robustness of identification. These enhancements improve the precision of rescue identification in UAV-captured images at sea. The experimental results indicated that EMR-YOLO improved mAP50 by 9.2% compared to YOLOv8s.

Figure 2.

EMR-YOLO structure diagram.

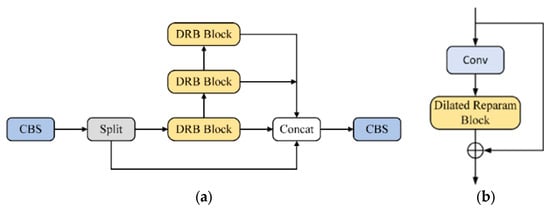

3.1. DRC2f

The C2f module of YOLOv8 consists of Bottleneck and CBS, which have redundant computation and insufficient feature extraction. To solve these problems, this paper improves the bottleneck of the C2f module using the Dilated Reparam Block [29] and designs an accurate and lightweight feature extraction module DRC2f, as shown in Figure 3a. This module achieves a lightweight design and obtains a good feature extraction capability. The receptive field can be enlarged while reducing the number of parameters, thus better capturing global information of the input data and improving the accuracy of the model at the same time.

Figure 3.

(a) Network structure of DRC2f. (b) DR Block.

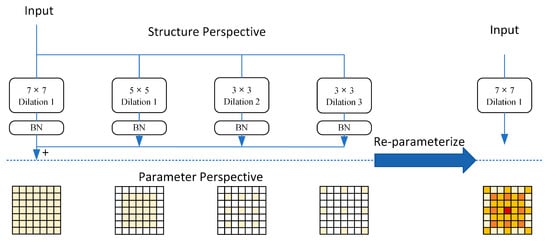

The DR Block consists of a Conv layer and a Dilated Reparam Block layer, as shown in Figure 3b. The working principle of the Dilated Reparam Block is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Dilated Reparam Block Schematic.

The Dilated Reparam Block module of the UniRepLKNet network [29] utilizes a combination of dilated convolution and reparameterization techniques to break down a large non-expanded convolutional kernel into a smaller non-expanded kernel and several smaller expanded kernels. First, dilation convolution is used through the dilation rate, which helps to capture sparse features and generate higher-quality features. The receptive field of the convolution kernel is expanded to capture a wider range of contextual information. Second, a reparameterization process is implemented to nonlinearly transform the convolution output, providing supplementary parameters and nonlinear functions. The objective of this approach is to augment the model’s expressive capacity and enhance its capability to capture input features.

To eliminate the inference cost of the dilated convolution, the entire block is treated as a non-dilated convolution. Let k be the kernel size of the dilated layer. By inserting zero entries, the equivalent kernel size of the non-dilated layer is . A transposed convolution to implement the original convolution kernel with a step size of r. The dilated convolution kernel is actually equivalent to inserting zeros between the elements of the original convolution kernel, obtaining the transformation of the convolution kernel , realizing the expansion of the convolution. The transposed convolution ( function uses weight sharing so that even as the size of the convolution kernel increases, many positions are filled with zeros. No large convolution kernel is used directly, and the actual amount of calculation does not increase. As shown in Equation (1), with the PyTorch-style pseudo code:

Among them, the dilation rate in the transposed convolution is , and the dilation rate refers to the number of holes inserted between the convolution kernel elements during the convolution operation. Formula (1) first upsamples the original convolution kernel to expand the size of the convolution kernel. Secondly, the use of the unit convolution kernel ensures that the transposed convolution operation only upsamples the original weights while maintaining the characteristics of the original convolution kernel W, and only expands the receptive field of the convolution kernel by inserting zeros. For a given arbitrary and arbitrary input channels, the convolution of W and r always produces the same result as the non-dilated convolution with W’.

UniRepLKNet is a large kernel convolutional neural network with its Dilated Reparam Block module offering multiple parameter configurations, and its network experiments are set up with a large convolutional kernel with k = 13, k = (5, 7, 3, 3, 3, 3), and r = (1, 2, 3, 4, 5), and equivalent kernel sizes of (5, 13, 7, 7, 9, 11), respectively. where the kernel size and expansion of the parallel branches are bounded by . Since our experiments require a smaller computational cost, we have selected smaller convolutional kernel configurations K = 7, r = (1, 2, 3), k = (5, 3, 3), and the equivalent kernel sizes will be (5, 5, 7), respectively, as shown in Figure 4.

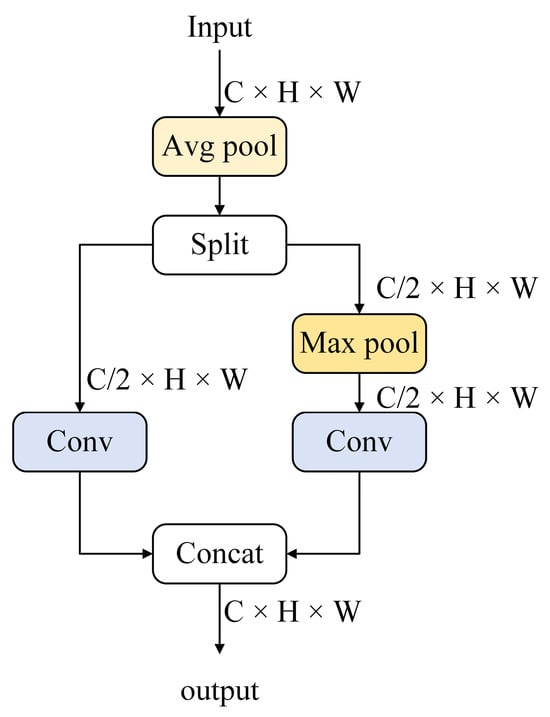

3.2. Adown

Downsampling is crucial in target recognition, as it reduces the size of the feature map while retaining important feature information. Additionally, downsampling reduces the computational load and the number of parameters, thereby speeding up the training and inference processes of the network. Convolution (Conv) is used for downsampling in the YOLOv8 network, which results in the loss of fine-grained information while reducing the size of the feature map. The sea rescue dataset in this study contains a large number of small targets and lacks redundant information, so the loss of fine-grained information will significantly affect the model’s detection performance [31]. Therefore, we adopt the Adown downsampling module from the YOLOv9 [32] project to improve YOLOv8, as shown in the EMR-YOLO structure diagram in Figure 2. The structure of the Adown module is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Structure of Adown downsampling.

First, the input feature map is downsampled using average pooling to reduce its size by half. After downsampling, the feature map is partitioned into ×1 and ×2 parts along the channel dimension. Then, a 3 × 3 convolution operation is applied to ×1 for feature extraction and dimensionality reduction of the feature map. Max pooling and a 1 × 1 pointwise convolution are applied to ×2 to increase nonlinear feature representation and further reduce dimensionality. Finally, the two partial feature maps after convolution are joined together to produce the output of the ADown module.

In contrast to standard convolutional downsampling, the ADown module uses a combination of max and average pooling during the downsampling process, allowing for a more thorough extraction of feature information. Additionally, the ADown module employs a multi-branch structure that enhances the network’s flexibility while better acquiring feature data at various scales. This method of varied downsampling aids in enhancing the model’s characterization capacity.

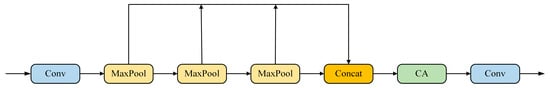

3.3. CASPPF

The function of SPPF is to obtain multi-scale features by splicing together the outputs of each of the three max pooling layers of 5 × 5 size. This process may result in information loss, particularly given the small size of maritime objects detected by UAVs and the complexity of environmental changes, which could make it difficult to accurately localize the target. To improve the model’s identification and localization skills and prevent the deep network from losing target feature information during input processing, the CA attention module is incorporated into the SPPF module. as depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

CASPPF structure diagram.

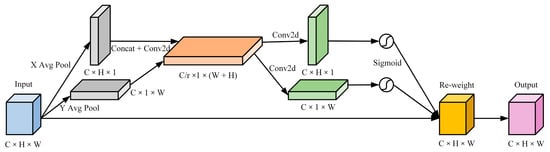

The CA module improves feature representation by embedding spatial location information into channel information, allowing the network to fully consider the relationship between feature map channels and spatial locations, adaptively adjusting the importance of each feature during fusion, and ignoring the interference of irrelevant background information. Compared with the SE [33] and ECA [34] attention mechanisms, which focus only on channel information, the introduction of the CA attention mechanism in the SPPF module efficiently focuses on both spatial and channel information to improve the accuracy and robustness of target recognition. The CASPPF module with the added CA attention mechanism can obtain higher performance with less computational cost. Figure 7 depicts the configuration of the CA module.

Figure 7.

CA attention mechanism.

The CA attention process is primarily separated into two stages: coordinate information embedding and coordinate attention generation.

In the first step, coordinate information embedding. The input feature map X of size C × H × W undergoes average pooling for the and directions, yielding direction-aware feature maps and in the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively. As shown below.

In the second step, coordinate attention is generated. coordinate attention is generated. The feature maps of and specific orientation information are subjected to a Concat operation, downscaled by a shared 1 × 1 convolution, and then the nonlinear activation function yields the intermediate feature vector , where r is the downsampling scale factor:

Then, after upscaling using two 1 × 1 convolutions and then combining with the Sigmoid activation function , the attention weights and of the feature map X in the horizontal and vertical directions are obtained as follows:

Finally, a weighted multiplication operation is performed by outputting the feature map with the feature weights. The following equation is used:

The SPPF module, incorporating the CA attention mechanism, emphasizes the features of interest while suppressing useless information in the feature map, effectively enhancing the network’s anti-interference and target localization problems, and improving the accuracy and robustness of target identification.

4. Testing and Analysis

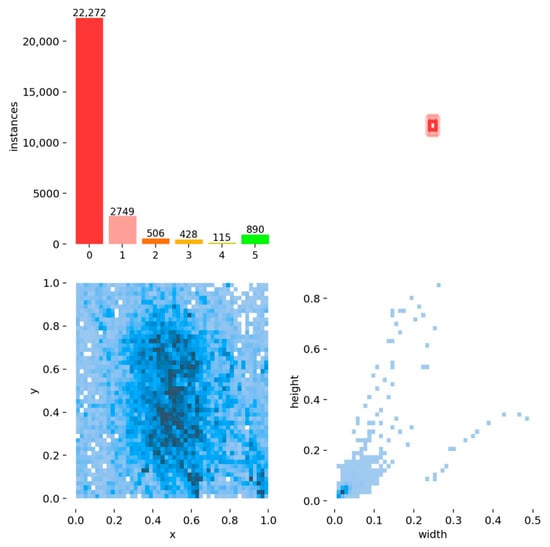

4.1. Dataset

The AFO dataset [35] is utilized as a maritime rescue dataset in this article. The dataset comprises 3647 images and 39,991 labeled objects, all of which were obtained from 50 video clips captured by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) at resolutions spanning from 1280 × 720 to 3840 × 2160. The training set has 67.4% of the objects in the dataset, followed by the validation set with 13.48% of the objects and testing with 19.12% of the objects. The target categories contain six categories: people, surfboards, boats, buoys, sailboats, and kayaks. To prevent model overfitting, test set images consist of frames collected from videos that were not utilized in the training and validation sets.

Figure 8 depicts the basic information of the training set, which is divided into four parts: the number of categories in the upper left corner, the location of the target’s center point in the image in the lower left corner, the size of the target frame in the upper right corner, and the aspect ratio of the target relative to the original image in the lower right corner. The dataset contains an abundance of crowded images and a significant number of small targets with an uneven distribution of categories.

Figure 8.

Basic information on the training set.

4.2. Test Environment

Training parameter settings are crucial in the model training process and have a significant impact on final detection accuracy. To ensure fairness in the comparison, this paper uses consistent parameters. The input image size affects feature extraction and computational complexity. To ensure detection accuracy, an input image of 640 × 640 pixels is selected. The batch size is set to 8. A smaller batch size allows for more parameter updates, leading to more stable model convergence. The number of training rounds (Epoch) is set to 200, meaning the model is fully trained 200 times. An appropriate number of training rounds can save computing resources and avoid the risk of overfitting. The learning rate is set to 0.001, and the momentum factor is 0.937 to adjust the convergence speed and training stability. The hardware and software environments used in the experiment are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental configuration.

4.3. Evaluation Index

To validate the enhancement’s efficacy, performance indices are used to compare the improved model to the dominant mainstream algorithms for target identification. Under the same software and hardware environment, the same experimental parameters are set, and the AFO dataset is used. The performance of the model is assessed in this research using metrics that are frequently employed in target identification algorithms: mean average precision (mAP), parameters, gig floating point operations per second (GFLOPs), and FPS. The values of p, R, and mAP are computed, as shown in Equations (8)–(11).

where stands for the number of true positive samples and for the number of false positive samples, respectively. stands for the number of false negative samples, for the precision rate, and for the recall rate. The precision rate is the proportion of correct identification results to total detection outcomes, as stated in Equations (8) and (9), while the recall rate is the proportion of correct detection to all actual results. The mean average precision (mAP) can provide a more accurate picture of the model’s overall detection performance compared to precision and recall rates. AP is defined as the area under the PR curve, and mAP is the average AP of each category. According to the COCO benchmark, AP is averaged over IOUs ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 in steps of 0.05. AP50 indicates an IoU (intersection-over-union) threshold of 0.5.

Furthermore, the model’s inference performance is indicated by frames per second (FPS). The model is deemed to satisfy the requirements for real-time identification if the FPS surpasses 30. The model complexity is then measured in terms of giga floating point operations per second (GFLOPs) and parameter count. The smaller the GFLOPs and the number of parameters, the less computing power is required to represent the model.

4.4. Performance Comparison and Analysis of Results

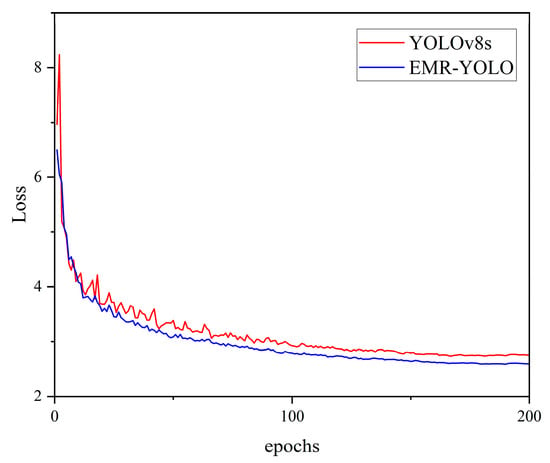

To evaluate the capability of the EMR-YOLO algorithm in marine rescue identification, YOLOv8s and EMR-YOLO are trained under the same experimental conditions. As shown in Figure 9, the red line represents the YOLOv8s loss function on the validation set during training, while the blue line represents the EMR-YOLO loss function on the validation set during training. The EMR-YOLO model has a smaller loss function, indicating that it can capture target features more accurately.

Figure 9.

Validation loss.

Table 2 shows the test results for YOLOv8s and EMR-YOLO. The mAP is 26.4% for YOLOv8s and 56.3% for mAP50 EMR-YOLO outperforms YOLOv8s on all metrics, improving mAP by 4.7% and mAP50 by 9.2%, while reducing computation and parameter count by 18.7% and 22.5%, respectively. The results suggest that the EMR-YOLO method described in this paper outperforms YOLOv8s for the marine rescue identification of UAV images.

Table 2.

Comparison of the improved models.

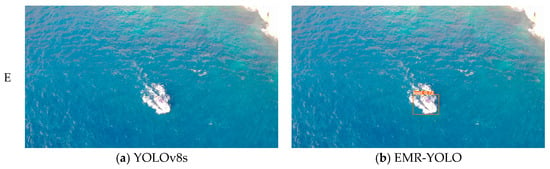

To further validate the identification performance, experiments were performed on the test dataset using the YOLOv8s and EMR-YOLO models. The identification results are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the identification results for YOLOv8s and EMR-YOLO. Images A, B, C, D, and E were captured by a UAV.

It can be concluded, based on the observations in Figure 10, that EMR-YOLO outperforms YOLOv8s in accurately identifying maritime targets in UAV images, particularly in the presence of similar or small targets. The identification performance of EMR-YOLO in detecting maritime targets in UAV images is compared with that of YOLOv8s, as illustrated in Figure 10. When the maritime target is small, fewer features are shown in the image, which may lead to missed identification and misidentification of YOLOv8s, as shown in row A in Figure 10. The YOLOv8s miss the identification due to the small size of the image captured by the UAV. In addition, as shown in row C of Figure 10, the UAV images acquired during the flight may have white highlights of seawater in the pictures due to sunlight-induced over-illumination, causing YOLOv8s to misidentify the background as a person. Due to the complexity of the background and the small size of the target, YOLOv8s incorrectly recognize the person as a surfboard in the image shown in row B. In row D, YOLOv8s incorrectly recognized the surfboard as a boat and the person as a surfboard. In the image in row E, YOLOv8s did not detect the target due to the overexposure of the image and the overlapping of the moving boat and the waves. These results demonstrate that EMR-YOLO has high accuracy, robustness, and anti-interference capabilities, enabling it to effectively solve the identification problem in complex marine environments.

4.5. Ablation Test

Ablation experiments with the YOLOv8s model were performed to evaluate the efficacy of the proposed EMR-YOLO model in detecting maritime targets. All of the hardware environments and parameter settings used for model training remained consistent throughout the experiment, and the experimental test results are shown in Table 3. The metrics mAP and mAP50 represent the accuracy evaluation, while GFLOPs and Params are the model’s computational and parametric complexity, respectively.

Table 3.

Results of ablation experiments.

Where M0, M1, M2, M3, M4, M5, and M6 denote the addition of DRC2f, Adown, and CASPPF to the YOLOv8s model, respectively. According to the results in Table 3, the improved algorithm of the present study effectively improves the accuracy, computation, and number of parameters compared to the original algorithm. Although the FPS has decreased, it remains much greater than that required for real-time detection (FPS > 30). When the DRC2f feature extraction module is introduced into YOLOv8s, mAP, and mAP50 increase by 1.6% and 1.0%, respectively, while the number of GFLOPs and parameters is reduced by 9.2% and 8.1%, respectively. When the model uses the improved CASPPF, the mAP50 increases from 56.3% to 58.6%, but the GFLOPs increase by only 0.1. The computational effort and parameters of the model were reduced when using Adown downsampling. We then conducted a fusion experiment of the two methods separately. In the M3 experiment, mAP and mAP50 increased by 3.1% and 5.1%, respectively, while maintaining the least GFLOPs and parameters. The remaining two methods also show improvement, proving the effectiveness of our improved methods. Finally, the EMR-YOLO model, obtained by combining the three improved methods, increases the mAP50 from 56.3% to 65.5% compared to the conventional YOLOv8s. In summary, all three improvement schemes enhance the identification accuracy of the model, and the target identification task of UAV images can be better realized using the EMR-YOLO algorithm.

4.6. Comparison Experiments

On the AFO test set, we compare the improved EMR-YOLO some advanced techniques, including YOLOv3, SDD, YOLOv5s, YOLOv7, YOLOv8s, and YOLOv8m models. The performance test results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of different target detection models.

As can be seen from Table 4, EMR-YOLO has the best combined performance in mAP, GFLOPs, and Params. Compared with YOLOv3, YOLOv5s, YOLOv7, YOLOv8s, and YOLOv8m, the mAP50 of EMR-YOLO improves by 12.4%, 15.1%, 5.1%, 9.2%, and 8.6%, respectively. EMR-YOLO had 43%, 93.2%, 77.6%, 18.7%, and 70.6% fewer GFLPOs than YOLOv3, SDD, YOLOv7, YOLOv8s, and YOLOv8m, respectively. Compared to YOLOv3, SDD, YOLOv7, YOLOv8s, and YOLOv8m, the parameter quantity in EMR-YOLO decreased by 86%, 64.8%, 76.4%, 22.5%, and 66.7%, respectively. Although YOLOv5s have fewer parameters and GDLOPs than EMR-YOLO, EMR-YOLO is superior to YOLOv5s, considering the accuracy of the algorithm. SDD has the best performance on mAP50, but the amount of computation and parameterization is too large for deployment in the model.

For the UAV platform with small hardware space and low arithmetic power, the improved model in this paper not only occupies small hardware space and meets the frame rate for real-time detection but also improves identification performance and better realizes the identification task. In summary, EMR-YOLO is a high-precision target identification algorithm suitable for realizing sea rescue with maritime UAVs.

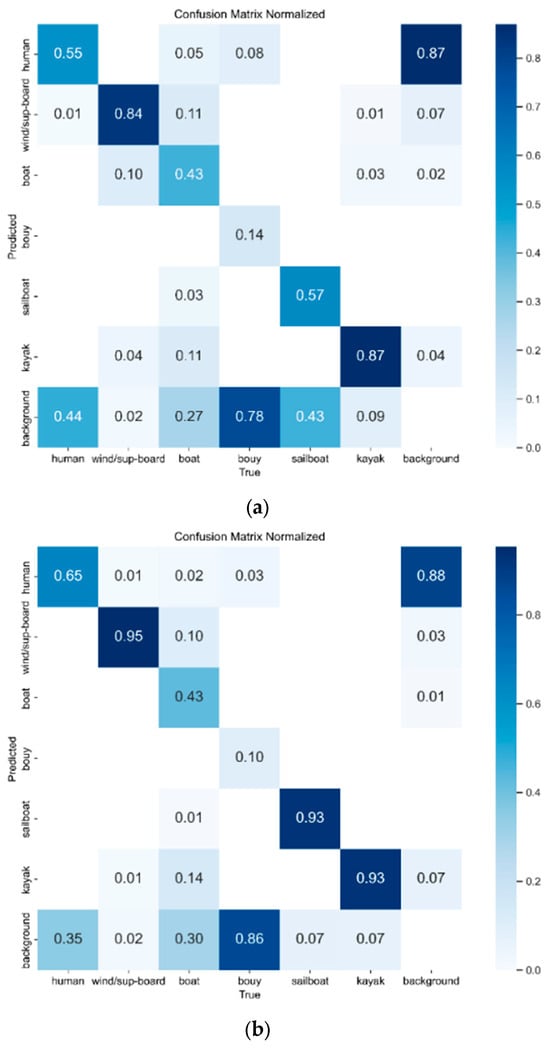

4.7. Visualization Analysis

To visually demonstrate the performance of the improved method, we evaluate the model using a confusion matrix and a heat map. The YOLOv8s and EMR-YOLO confusion matrices, which can visualize how each target category is classified, are displayed in Figure 11. The predicted categories in this instance are represented by the rows of the confusion matrix, the true categories by the columns, the percentage of correctly predicted categories by the values in the diagonal region, the percentage of missed detections by the lower left region, and the percentage of false detections by the upper right region. The proportion of EMR-YOLO in the diagonal zone in Figure 11 is greater than that of YOLOv8s, suggesting that the EMR-YOLO model is more accurate at identifying targets.

Figure 11.

(a) YOLOv8s confusion matrix; (b) EMR-YOLO confusion matrix.

Among them, the proportion of people successfully detected is 65%, which is 10% higher than that of YOLOv8, demonstrating that our model can better identify humans in falling water. YOLOv8s and EMR-YOLO had higher miss detection rates for detecting people and buoy categories, and the highest false detection rate for identifying people, which is mostly due to the smaller target, complex background, and tag imbalance in the dataset.

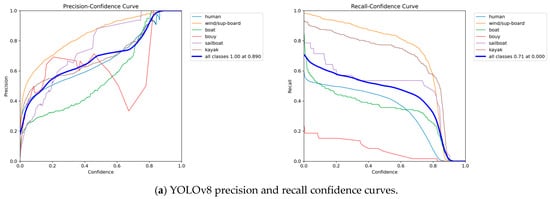

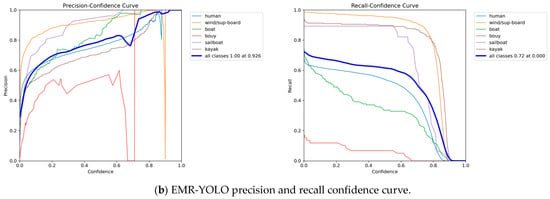

To better reflect the performance of the model, we compare the output of YOLOv8s and EMR-YOLO. As shown in Figure 12, in the precision confidence curve, it can be observed that at different confidence levels, the average accuracy of EMR-YOLO (blue line) is significantly higher than that of YOLOv8s. At the same time, in the recall confidence curve, the recall rate of EMR-YOLO at different confidence levels is also better than that of YOLOv8s. This demonstrates that our model has significantly improved both accuracy and recall at different confidence levels, enhancing its ability to identify maritime targets more accurately.

Figure 12.

Comparison of precision and recall before and after improvement.

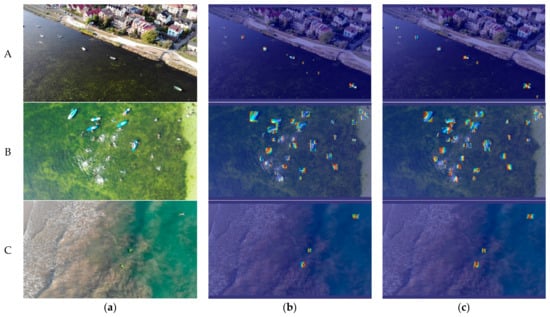

The features output from the YOLOv8s and EMR-YOLO models are visualized and compared using the CardCAM heat map to provide a more intuitive display of the pixel regions of interest and the degree of attention before and after model improvement. The redder the color, the more attention the region receives. The results are shown in Figure 13, which shows that YOLOv8s does not pay much attention to small objects, and the extraction ability is not as good as that of EMR-YOLO. For example, as shown in row A, YOLOv8s extracts extra background information, while the EMR-YOLO module successfully extracts the target, which indicates that the model can suppress the background noise well and improve the accuracy of detecting small targets. Comparison between rows B and C shows that the EMR-YOLO algorithm can focus on the target object more correctly and with a larger focus area under different lighting environments and interference conditions, which means that the improved model is more accurate for recognition at sea and improves the model’s overall performance.

Figure 13.

Rows A, B and C represent yolov8 and EMR comparison plots. (a) Original image; (b) YOLOv8s thermogram; (c) EMR-YOLO thermogram.

Overall, the proposed EMR-YOLO network is an efficient UAV maritime rescue identification network that can accurately and quickly recognize maritime targets, thereby improving the efficiency of maritime rescue.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the EMR-YOLO algorithm we propose demonstrates notable benefits in the identification of maritime targets through the integration of deep learning techniques with UAV-captured images, thereby enhancing the efficacy of maritime surveillance and rescue systems. The EMR-YOLO algorithm is suggested to mitigate the challenges posed by small targets, complex environments, and inconspicuous features in UAV images. First, the Dilated Reparam Block is added to the algorithm’s backbone network, and it is used to improve the bottleneck in the C2f module. The method employs dilated convolution and reparameterization to extract more effective features while suppressing unnecessary ones, thus boosting the model’s ability to capture global feature information. Second, to mitigate the information loss induced by downsampling, we switch from convolution to ADOWN as the downsampling method. Finally, we develop CASPPF for multi-scale feature fusion. We incorporate the CA attention mechanism into SPPF, enabling the network to better focus on small targets at sea. The experimental results show that the EMR-YOLO algorithm proposed in this paper outperforms the other tested models by improving mAP and mAP50 performance by 4.7% and 9.2%, respectively, compared to the YOLOv8s algorithm on the AFO dataset. In addition, EMR-YOLO performs excellently in recognizing small targets and complex environmental contexts in UAV images. It has advantages in inference speed, model computation, and number of parameters. The visual comparisons show that the model meets the performance requirements for maritime rescue detection. Our future goal is to enhance the accuracy and generalization capabilities of EMR-YOLO and implement it on edge devices for better real-time target recognition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. (Jun Zhang), C.L. and J.Z. (Jianping Zhu); Formal analysis, L.L., L.C. and X.S.; Investigation, X.S., Y.H., W.S. and S.W.; Methodology, C.L., L.L. and L.C.; Validation, X.S., Y.H. and Y.F.; Software, Y.F., W.S. and S.W.; Visualization, L.L., L.C. and X.S.; Writing—original draft, J.Z. (Jun Zhang) and J.Z. (Jianping Zhu); Writing—review and editing, J.Z. (Jun Zhang) and J.Z. (Jianping Zhu). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- European Maritime Safety Agency. Annual Overview of Marine Casualties and Incidents 2023; European Maritime Safety Agency: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Munari, F. Search and Rescue at Sea: Do New Challenges Require New Rules? In Governance of Arctic Shipping: Rethinking Risk, Human Impacts and Regulation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Jiang, Z.; Sun, R.; Cheng, N.; Feng, H. Maritime Search and Rescue Based on Group Mobile Computing for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Unmanned Surface Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 7700–7708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Guo, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, F.; Huan, Y.; Liu, R.W. Intelligent maritime surveillance framework driven by fusion of camera-based vessel detection and AIS data. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Macau, China, 8–12 October 2022; pp. 2280–2285. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision & Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, R.W.; Qu, J.; Gao, R. Deep learning-based object detection in maritime unmanned aerial vehicle imagery: Review and experimental comparisons. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 128, 107513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, X.; Chen, J. Feature extraction for rescue target detection based on multi-spectral image analysis. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety (ICTIS), Wuhan, China, 25–28 June 2015; pp. 579–582. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.-J.; Du, Y.-C.; Sheng, W.-G.; Ling, H.-F. Collaborative human–UAV search and rescue for missing tourists in nature reserves. INFORMS J. Appl. Anal. 2019, 49, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leira, F.S.; Helgesen, H.H.; Johansen, T.A.; Fossen, T.I. Object detection, recognition, and tracking from UAVs using a thermal camera. J. Field Robot. 2021, 38, 242–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, T.; Yu, X.; Pang, B.J.J.o.I.; Systems, R. Unmanned surface vessel visual object detection under all-weather conditions with optimized feature fusion network in YOLOv4. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2021, 103, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Dai, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, S. A detection method of the rescue targets in the marine casualty based on improved YOLOv5s. Front. Neurorobot. 2022, 16, 1053124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Yin, Y.; Jing, Q.; Shao, Z. A High-Precision Detection Model of Small Objects in Maritime UAV Perspective Based on Improved YOLOv5. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Shao, Z. An Enhanced Target Detection Algorithm for Maritime Search and Rescue Based on Aerial Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.E.; Osindero, S.; Teh, Y. A Fast Learning Algorithm for Deep Belief Nets. Neural Comput. 2006, 18, 1527–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 2015, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28 (NIPS 2015), Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Proceedings, Part I 14. pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: Better, faster, stronger. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 7263–7271. [Google Scholar]

- Bosio, A.; Bernardi, P.; Ruospo, A.; Sanchez, E. A reliability analysis of a deep neural network. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Latin American Test Symposium (LATS), Santiago, Chile, 11–13 March 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.-Y.; Liao, H.-Y. Yolov4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.-Y. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Spatial Pyramid Pooling in Deep Convolutional Networks for Visual Recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2014, 37, 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 8759–8768. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, Y.; Zhao, S.; Song, L.; Yue, X.; Shan, Y. Unireplknet: A universal perception large-kernel convnet for audio, video, point cloud, time-series and image recognition. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.15599. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 13713–13722. [Google Scholar]

- Sunkara, R.; Luo, T. No more strided convolutions or pooling: A new CNN building block for low-resolution images and small objects. In Proceedings of the Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Grenoble, France, 19–23 September 2022; pp. 443–459. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Yeh, I.-H.; Liao, H.-Y. YOLOv9: Learning What You Want to Learn Using Programmable Gradient Information. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.13616. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 11534–11542. [Google Scholar]

- Gasienica-Jozkowy, J.; Knapik, M.; Cyganek, B. An ensemble deep learning method with optimized weights for drone-based water rescue and surveillance. Integr. Comput.-Aided Eng. 2021, 28, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).