Abstract

The use and transformation of biomass into highly valuable products is a key element in circular economy models. The purpose of this research was to characterise the volatile compounds and the temperature at which they are emitted during the thermal decomposition by pyrolysis of algal biomass while looking at three different types: (A1) endemic microalgae consortium, (A2) photobioreactor microalgae consortium and (A3) Caribbean macroalgae consortium. Furthermore, the ultimate (CHON) and proximate (humidity, volatile solids and ashes) compositions of the algal biomass were determined. Some volatile species were identified as having potential industrial interest for use as precursors and intermediaries, such as commercially used aromatic compounds which if not suitably managed can be harmful to our health and the environment. It is concluded that the pyrolysis of algal biomass shows potential for the generation of valuable products. The information generated is useful, especially the temperature at which volatility occurs, in order to access the valuable compounds offered by the algal biomasses, and under the concept of biorefinery convert the issue of biomass disposal into a sustainable source of raw materials.

1. Introduction

Biomass use and the circular economy are closely linked in terms of the availability of materials and energy production [1]. In general, biomass mainly consists of food processing waste, crop waste and dry biomass from leaves [2]. However, there is worldwide interest in the exploitation of algae based processes and products, essentially due to the diversity of this biomass’s chemical composition, as well as its broad spectrum of secondary metabolites. Under the concept of a low-carbon circular bioeconomy, it has been discovered that it is both environmentally and financially desirable to simultaneously combine the algae CO2 deposits and waste flow phytoremediation, with the synthesis of high value-added products [3,4].

Thermochemical conversion is an attractive option for the treatment and conversion of the biomass [5], as it displays great efficiency, as well as producing a wide range of substances [6]. Thermochemical conversion by pyrolysis, combustion and gasification are the most commonly used technologies in the biomass processing industry [7,8]. Furthermore, pyrolysis in particular, as well as being a precursor to the thermochemical processes of gasification and combustion, is one of the most promising routes for thermochemical conversion in the production of fuel and other chemical compounds [5,9]. Pyrolysis is a process in which superimposed reactions are produced in the absence of oxygen. It is a highly versatile technology that takes advantage of all of the fractions making up the biomass [10,11]. In general, it was identified that higher temperatures and longer residence times promote the production of volatile gases as the main product of pyrolysis, whereas lower temperatures and longer residence times lead to the formation of solids [8].

It was also discovered that the high heating value (HHV) of the biomass pyrolysis gas is directly associated with the pyrolysis temperature i.e., as the pyrolysis temperature increases the HHV also increases [12]. The macroalgae-based syngas generates a higher energy content (4.6–17.2 MJ/kg) in comparison to microalgae-based syngas (1.2–5.1 MJ/kg), although when a suitable feedstock is selected the bio-oil yield generated from algal biomass can exceed 55% (>40 MJ/kg) [13].

Diverse studies were carried out to observe the pyrolytic behaviour of biomasses, mainly using thermogravimetric (TG) analysis [5,14,15].TG analysis has been used as a proven technique to study the thermochemical phenomena of microalgae. The advantages of using a thermogravimetric analyser are its easy operation, minimal use of raw material, precise control and ability to record temperature and sample weight loss [16]. Sukarni (2020) studied the combustion process and the kinetic parameters of the microalgae Spirulina, synthetic waste and mixture of both. He observed that variances in organic and mineral compounds in typical microalgae species lead to differences in thermal degradation [17]. Meanwhile, Jabeen et al. (2020) proposed an alternative thermogravimetric analytical procedure for the proximate analysis of algal biomass, using Spirulina and Chlorella as model algae [18].

Other authors have studied the volatile compounds (VCs) released during the pyrolysis of the biomasses using gas chromatography techniques, such as analytical pyrolysis-mass spectrometry (PyGC/MS) [19,20] and GC/MS attached to a tube furnace [9]. Furthermore, it was found that applying the technique of thermogravimetric characterisation coupled with gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (TG-GC/MS) enables information on the sample’s mass loss and VCs released at certain temperatures to be obtained, simultaneously [8,10,21,22].

Diverse studies show the importance of studying the VCs of pyrolysis in order to promote the use of biomass [23,24,25]. However, the characterisation of VCs of biomasses is an ongoing challenge due to their diverse origins, forms and complexities [20,26]. The objective of this investigation was to study the thermal decomposition of algal biomass by pyrolysis and determine the main volatile metabolites emitted using TG-GC/MS coupling techniques. According to Vieira et al. (2020) under the framework of a circular economy all of the biomass fractions must be valued in order to make its use competitive [3]. Therefore, studying the VCs will promote the exploitation of the compounds offered by algal biomasses under the concept of biorefinery.

2. Materials and Methods

This research analysed 3 types of algae: (A1) endemic microalgae consortium from a body of water (unidentified), (A2) microalgae consortium cultivated in a photobioreactor (Spirulina microalgae) and (A3) Mexican Caribbean macroalgae consortium (Sargassum natans & S. fluitans).

The endemic microalgae studied were obtained from the peri-urban dam Chuvíscar in Chihuahua city, Mexico (28°35′56″ N, 106°6′59″ W). The sample of cultivated microalgae was obtained from an experimental photobioreactor prototype from the start up Alis Algae Solutions, which used waste water as a culture medium. The photobioreactor prototype is a closed vertical reactor made of polycarbonate in the shape of a hexagonal prism with a flat bottom and a gas diffuser, which combines the mechanism of a column of bubbles with an air-lift type reactor in order to cultivate Spirulina microalgae.

The Sargassum macroalgae samples were gathered from Caribbean beaches in the hotel coastal area of Cancun, Mexico (21°4′04.1″ N, 86°46′33″ W).

The biomasses were washed with drinking water, dried in the sun for three days at normal environmental temperature and stored for characterisation in high-density polyethylene bags. They were then dried in an electric oven at 105 °C. The samples were sieved using a 100 mesh and stored in a dryer for subsequent characterisation. According to Mlonka-Mędral et al. (2019) the particle size of the biomass is an important parameter that must be considered when planning the thermal conversion process [8].

For the ultimate analysis, the C, H, O and N elements present in the biomass samples were determined via the chromatography of elements in a Thermo Scientific Flash Smart device with a Porapak PQS column and molecular sieve, using helium as the carrier gas.

The determination of volatile solids (VS), percentage humidity, and ashes of the biomass samples were determined using TG. STA Regulus 2500 Netzsch equipment was used with a heating ramp rate of 10 °C/min from 20 to 1000 °C with a sample of mass 10 mg in an alumina crucible using helium (99.999%) as a carrier gas with a flow rate of 50 mL/min. The derivative time thermogravimetric analysis (DTG) was also performed.

The TG, DTG curves combined with the GC/MS results were used to describe the pyrolysis process [10,27]. The volatile metabolites emitted during pyrolysis were determined using the TG-GC/MS coupling technique with the same temperature ramp and experimental conditions as the TG. An STA Regulus 2500 Netzsch attached to an Agilent 7890B Gas Chromatograph device and a mass spectrometer 5977B (GC/MS) via a JAS transfer line were used. Helium (99.999%) was used as a carrier gas at a flow rate of 50 mL/min in a Porapak 19091S-433UI column of 30 m coupled to a quadruple MS simple, using a mass range from 35 to 450 m/z to characterise the emitted volatiles. 48 injections of the STA to the GC/MS system were carried out for each experiment within a total time of 110 min, during the pyrolysis thermal treatment at a constant temperature of 150 °C in the column.

Agilent MassHunter software was used to gather and analyse chromatographic peaks. Only peaks with areas that represent 5% or more of the largest peak area in the chromatogram and with a degree of certainty greater than 60% were included for identification. The compounds were identified using the database of National Institute Standard and Technology (NIST).

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Ultimate Analysis

Table 1 displays the values obtained in the ultimate analysis of algal biomasses.

Table 1.

Ultimate analysis of biomasses by elemental chromatography.

The pyrolysis behaviour largely depends on the chemical structure of the biomasses. The C/N ratio is an important parameter in the study of thermochemical processes, which is useful in determining the most suitable energy conversion process. It was discovered that higher ratio values indicate a more suitable biomass for the gasification process [7,15]. However, lower values of this ratio in the biomasses confirm that the development of NOX would be minimised in the pyrolysis [28]. These observations are consistent with the potential for using the Sargassum macroalgae via gasification and the lower production of NOx in the pyrolysis of the algae cultivated in a photobioreactor.

Several authors have reported very variable C/N ratios in biomasses ranging from 8.72 to 58 [29]. In our study, the values are found in the rage of 6.72 to 24.

Furthermore, Filer et al. (2019) identified that a C/N ratio close to 40 leads to optimal operation for the anaerobic digestion of the biomasses [30]. This is a value found to be within the range recommended by Al Seadi et al. (2013), in the production of biogas which is 16 to 45 for efficient digester performance [31]. If this ratio is high the nitrogen is rapidly consumed and biogas production decreases and if low, inhibitors such as ammonia and volatile fatty acids can accumulate [32]. The C/N ratio for Sargassum was determined to be within this range for biogas production (Table 1) and this was shown in previous studies [33]. For their part, the endemic macroalgae and the microalgae of the photobioreactor show less potential for biogas production.

The energy content of the samples also depends on their inherent bonds of O-C and H-C. Table 1 shows the molar ratios O/C and H/C found for the biomasses of this study, and indicates the carbonisation degree for the samples. The raw materials for the biochars show O/C ratios in the range of 0.4 to 0.9 and H/C ratios between 1.3 and 1.9, whereas after the pyrolysis process the fuel biochars and carbons show O/C values in the range of 0.05 and 0.5 and H/C ratios between 0 and 1.5 [34]. The biomasses analysed presented O/C values exceeding 1 in all cases, and H/C values exceeding 1.4 which indicate greater oxidation and less condensation of the samples.

3.2. Proximate Analysis

Table 2 shows the proximate analysis obtained by thermogravimetry for each of the biomasses.

Table 2.

Proximate analysis of biomasses by TG.

Variability in the percentage humidity determined was mainly affected by the drying technique, the presence of intermolecular water and the susceptibility of the dry biomasses to reabsorbing humidity from the atmosphere.

Several authors identified a VS range for diverse biomasses of 3.93 to 96.96% [10,20,23,24,28,35,36,37,38], The VS content found in Laminaria digitate, Ascophyllum nodosum and Chaetomorpha macroalgaes was 25.5, 63.3 and 84.3%, respectively [39] while Spirulina platensis microalgae contained 77.96% [17], and Chlorella vulgaris microalgae 84.3%, [18]. The presence of ash in biomasses has appeared in the range between 0.34 and 52.39% [7,9,10,20,24,28,35,36,39,40], for Laminaria digitate, Ascophyllum nodosum and Chaetomorpha macroalgaes are 59.9, 31.8 and 67.6%, respectively [39]. Additionally, for Spirulina platensis and Chlorella vulgaris microalgae it was observed 10.14 and 5.3% [17,18].

This research found VS values between 3.73 and 68.7% and for ashes between 18.86 and 94.5%, respectively (Table 2). The presence of VS is related to the organic matter and the amount of ash with the presence of mineral compounds found in the algal biomass The ash content and its chemical composition cause significant issues during thermal processing, considering the dirt and slag generated, as well as the corrosion of metal surfaces in the boiler systems [8]. An example of this is the case with the endemic microalgal biomass that displayed 94.25% ash.

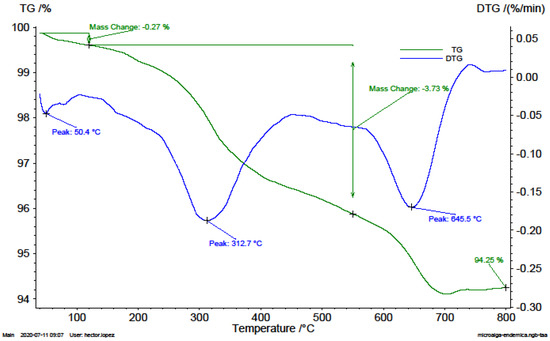

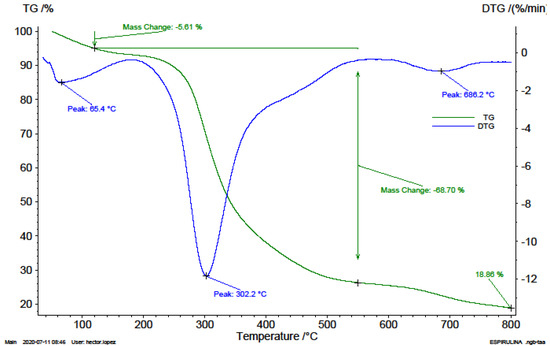

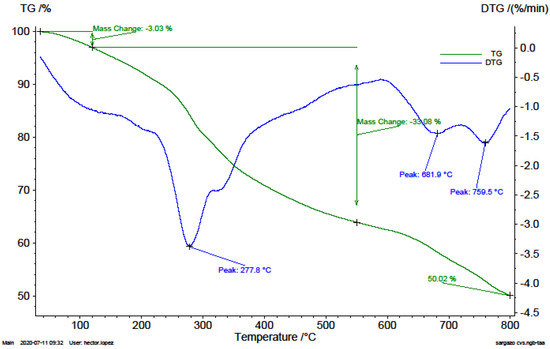

Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the thermograms of the algal biomasses studied and the differential curves of the same. Within the range of 150 and 360 °C, with a greater volatile generation rate at 180 °C, the decomposition of both proteins and soluble polysaccharides occurs. At higher temperatures (maximum rates at 271 and 411 °C) the cellulose present in the cellular walls decomposes, as well as other insoluble polysaccharides, and the lipids present decompose between 330 and 560 °C [22,26].

Figure 1.

TG an DTG thermograms of endemic microalgae consortium sample (A1).

Figure 2.

TG an DTG thermograms of photobioreactor microalgae consortium sample (A2).

Figure 3.

TG an DTG thermograms of Mexican Caribbean macroalgae consortium sample (A3).

In the thermograms, Figure 1, the first drop associated with the humidity present in the sample is identified at a rate of 0.05%/min. The highest peak on the DTG curve shows a maximum rate of 0.19%/min and is related to the decomposition of saccharides (cellulose). The second highest peak was at a rate of 0.17%/min, related to the thermal decomposition of the carbonates and the sulphated salts present. The great amount of ash generated may indicate the presence of recalcitrant compounds in the sample.

Figure 2 shows the TG and DTG thermograms of microalgae consortium sample cultivated in a column photobioreactor. A loss in mass of 5.61%, associated with humidity, is observed even after drying at 150 °C, which is associated with the water chemically bound to the cellulose structure of the algae. The greatest material decomposition and emission of the highest number of volatiles were observed between 300 and 400 °C, ending at 500 °C.

A maximum weight loss rate of 11.84%/min, at 302.2 °C was identified on the DTG curve of the microalgae cultivated in the photobioreactor and associated with the decomposition of the cellulose. The second highest peak on the DTG curve is associated with the humidity loss of the sample, at a maximum rate of 1.56%/min. Above 550 °C, the occurrence of calcite decarbonisation and devolatisation of CO2 are observed, respectively. The presence of carbonates and sulphates in the sample of up to 20% is also deduced. A slight drop between 600 and 800 °C associated with the thermal decomposition of the carbonates and probable metallic sulphates present is identified, with a maximum devolatisation rate of 0.97%/min at 686.2 °C.

In the thermogravimetric analysis obtained for the Sargassum (Figure 3), the maximum decomposition rate of the biomass on the DTG curve was 3.38%/min, and the overlapping of two peaks is observed which could be associated with the decomposition of the hemicellulose, cellulose and salts present in the biomass. Within the interval from 600 to 800 °C of the DTG curve, two main peaks were identified with rates of 1.46%/min and 1.62%/min, the first related to the decomposition of sulphated metal compounds present and the second with the decarbonation. The ash, determined as 65% of the sample weight from combustion tests that are not presented in this work, will be material rich in CaO and CaCO3 that could not be decomposed.

In agreement with several authors the greatest mass loss for the biomasses occurs between 150 and 500 °C [21,28].

In this work, It was identified that the main devolatisation reactions of microalgal pyrolysis occur between 160 and 600 °C. And the maximum devolatisation rates of the biomasses studied were observed within the temperature range of 207.1 and 312.7 °C. The microalgal biomass cultivated in a photobioreactor displayed the greatest weight loss of 11.84%/min at 302.2 °C (Figure 1). The endemic algae biomass displayed the lowest devolatisation rate of 0.19%/min at 312.7 °C (Figure 2). The VC generation rates are mainly associated with the cellulosic compounds of the biomasses according to Zong et al. (2020) who states that cellulose in pure form decomposes between 302.9 °C and 387.8 °C with a 96.66% volatile content [20].

3.3. TG-GC/MS Analysis

Lignocellulosic biomass is a complex mixture of carbohydrate polymers such as cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin and trace amounts of other substances. Its thermal decomposition occurs through a series of complex and competitive reactions, that depend on conditions such as reaction temperature, residence time and biomass properties, where units of intermediate polymeric macromolecules are decomposed into more simple units, thereby forming organic products [41,42]. The TG-GC/MS coupling system enables a correlation to be made between the thermal behaviour of the decomposition of materials and the composition of the pyrolytic gas [8].

Table 3 shows the fragments of molecular ions detected during the pyrolysis of the GC/MS analysis of A1 algae.

Table 3.

Volatile compounds detected during the pyrolysis of the GC/MS analysis of endemic micro-algae consortium sample (A1).

Table 4 shows the fragments of molecular ions that were detected during the pyrolysis of the GC/MS analysis of A2 algae.

Table 4.

Volatile compounds detected during the pyrolysis of the GC/MS analysis of photobioreactor microalgae consortium sample (A2).

Table 5 shows the fragments of molecular ions detected during the pyrolysis of the GC/MS analysis of A3 algae.

Table 5.

Volatile compounds detected during the pyrolysis of the GC/MS analysis of the Mexican Caribbean macroalgae consortium sample (A3).

During the pyrolysis of the algal biomass the diversity of volatile compounds was determined, and as well as the compounds shown in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 the main products were CO, CO2 and H2O [11,22]. However, these gasses were not shown in the result tables as they were not considered important for this study.

Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 shows the compounds of interest detected, Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) numbers and some of their main characteristics.

Table 6.

Volatile compounds (carboxylic acids) detected in the TG-GC/MS coupling analysis of the algal biomass during pyrolysis.

Table 7.

Volatile compounds (amines) detected in the TG-GC/MS coupling analysis of the algal biomass during pyrolysis.

Table 8.

Volatile compounds (aromatic) detected in the TG-GC/MS coupling analysis of the algal biomass during pyrolysis.

Table 9.

Volatile compounds detected in the TG-GC/MS coupling analysis of the algal biomass during pyrolysis.

In agreement with several authors carboxylic acids (Table 6) and amines (Table 7) produced during the pyrolysis of marine algae were identified [11,22,61]. Furthermore, in accordance with many authors aromatic compounds (Table 8) produced by the pyrolysis of microalgae were determined [3,84]. It was proposed that the algae’s proteins could be combined with the carbohydrates and react to form aromatic compounds such as phenols, pyrroles and indoles [26]. In the specific case of Sargassum, the production of volatile aromatic compounds could be related to the presence of complex aromatic polyphenols identified in the macroalgae [100]. In the same manner, the presence of some alcohols were also determined in the pyrolysis of the algal biomass. It was found that the linoleic fatty acids are the precursors of aldehydes that can be subsequently reduced to alcohols by dehydrogenases. Furthermore, according to Yang et al. (2019) reactions such as decarboxylation and deoxygenation of carbohydrates in the algae can give alcohols as a result [26].

The pyrolysis of algae has not been commercialised and only tested at bench scale [26]. However, the presence of compounds of commercial interest in the pyrolytic gasses makes the pyrolysis process a promising technology for the disposal of biomasses and the production of high value products.

Further studies are required to evaluate the volatile compounds produced by the pyrolysis of algae with other chromatography techniques such as PyGC/MS, in order validate the findings of this investigation.

The fragments of molecular ions detected using the TG-GC/MS technique are related to the pyrolytic VCs that can be obtained from the algal pyrolysis. However, it is necessary to validate that the compounds detected are not the product of the interaction of VCs with the plasma in the chromatography technique.

The VCs that can be obtained from the algae are a mixture of compounds, and to select the most advantageous volatile compound recovery technique it is necessary to also investigate the location of the target compound within the biochemical system and the volatility of the target molecule, as well as its distribution across the phases under real production conditions [3]. It is advisable to carry out a quantitative analysis of the volatile compounds of interest in large-scale pyrolytic systems, especially those determined with devolatisation within the range of 207.1 and 312.7 °C.

It was identified that the algae adapt to abiotic stress (humidity, mineral composition and temperature, quantity and intensity of light) during their life cycle. Therefore, different compositions and properties of the liberated VCs involve different algae species, and growth and reaction conditions [26,61]. Therefore, it is advised to carry out a seasonal analysis of the algae species available each season and the VCs that can be obtained with biomass pyrolysis for its use as part of a circular economy model.

After the VCs are extracted the residual biochar could be used as fuel. Likewise, the biochar could potentially be used as an adsorbent medium for the filtration of fluids or in application to soils in combination with either organic or inorganic fertilizers due to its pore structure and surface area, as well as the presence of N, P and K [101]. Its characterisation is needed to identify the best use for this biochar.

4. Conclusions

This research analysed samples of algal biomasses: consortium of endemic microalgae from a body of water, consortium of microalgae cultivated in a photobioreactor and Sargassum macroalgae consortium. It was determined that the most part of the material is decomposed to VCs under the TG conditions. Furthermore, the VCs show potential for application in the generation of valuable chemical substances. The study was limited to the semi-analytical and qualitative analysis of the species. Further quantitative analysis of the substances produced is required in order to evaluate their feasibility as valuable products. As well as the volatile compounds of industrial value detected during the pyrolytic decomposition, aromatic compounds were also identified, such as toluene and benzaldehyde which when burned emit substances that are harmful to the ecosystem. Due to this fact, the studied algal biomasses are not recommended for direct use as fuel due to the potential risk of generating toxic gases. It is advisable to evaluate the release of the VCs found in the pyrolysis for the production of biochar, given that some are potential sources for environmental contamination.

The comprehensive use of biomasses available as part of the circular economy is imperative. The use and implementation of photobioreactors as greenhouse gas capturing systems in urban areas and the use of algal biomass generated in urban bodies of water and the ocean via pyrolysis are promising technologies for converting the issue of biomass disposal into a sustainable source for raw materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, review and editing, H.A.L.-A., writing—original draft preparation, D.Q.-C., writing—review and editing, A.P.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge to Centro de Investigación en Materiales Avanzados S. C. (CIMAV); and Universidad La Salle de Chihuahua. As well as the projects: CONACYT-SENER 243715 and CONACYT-SEMAR 305292 for their support to the generation of infrastructure and laboratories.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sherwood, J. The significance of biomass in a circular economy. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 300, 122755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoumpou, V.; Novakovic, J.; Kontogianni, N.; Barampouti, E.M.; Mai, S.; Moustakas, K.; Malamis, D.; Loizidou, M. Assessing straw digestate as feedstock for bioethanol production. Renew. Energy 2020, 153, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, K.R.; Pinheiro, P.N.; Zepka, L.Q. Volatile organic compounds from microalgae. In Handbook of Microalgae-Based Processes and Products; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 659–686. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, Y.K.; Chew, K.W.; Chen, W.-H.; Chang, J.-S.; Show, P.L. Reuniting the Biogeochemistry of Algae for a Low-Carbon Circular Bioeconomy. Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasool, T.; Kumar, S. Kinetic and Thermodynamic Evaluation of Pyrolysis of Plant Biomass using TGA. Mater. Today: Proc. 2020, 21, 2087–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, J.J.; Doshi, V. Recent advances in biomass pretreatment—Torrefaction fundamentals and technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 4212–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellucci, S.; Cocchi, S.; Celma, C.B. Energy characterization of residual biomass in Mediterranean Area for small biomass gasifiers in according to the European Standards. Appl. Math. Sci. 2014, 8, 6621–6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlonka-Mędrala, A.; Magdziarz, A.; Dziok, T.; Sieradzka, M.; Nowak, W. Laboratory studies on the influence of biomass particle size on pyrolysis and combustion using TG GC/MS. Fuel 2019, 252, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningbo, G.; Baoling, L.; Aimin, L.; Juanjuan, L. Continuous pyrolysis of pine sawdust at different pyrolysis temperatures and solid residence times. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2015, 114, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Ding, L.; Gong, Y.; Li, W.; Wei, J.; Yu, G. Effect of torrefaction on pinewood pyrolysis kinetics and thermal behavior using thermogravimetric analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 280, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-González, D.; Fernandez-Lopez, M.; Valverde, J.; Sanchez-Silva, L. Pyrolysis of three different types of microalgae: Kinetic and evolved gas analysis. Energy 2014, 73, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlavsová, A.; Corsaro, A.; Raclavska, H.; Juchelková, D.; Škrobánková, H.; Frydrych, J. Syngas Production from Pyrolysis of Nine Composts Obtained from Nonhybrid and Hybrid Perennial Grasses. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 723092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, X.J.; Ong, H.C.; Gan, Y.Y.; Chen, W.H.; Mahlia, T.M.I. State of art review on conventional and advanced pyrolysis of macroalgae and microalgae for biochar, bio-oil and bio-syngas production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 210, 112707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, B.V.; Gaibor-Chávez, J.; Niño-Ruiz, Z.; Cortés-Rojas, E. Development of biomass fast proximate analysis by thermogravimetric scale. Renew. Energy 2018, 126, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajka, K.; Modliński, N.; Kisiela-Czajka, A.M.; Naidoo, R.; Peta, S.; Nyangwa, B. Volatile matter release from coal at different heating rates—Experimental study and kinetic modelling. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2019, 139, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, Q.-V.; Chen, W.-H. Pyrolysis characteristics and kinetics of microalgae via thermogravimetric analysis (TGA): A state-of-the-art review. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 246, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukarni, S. Thermogravimetric analysis of the combustion of marine microalgae Spirulina platensis and its blend with synthetic waste. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabeen, S.; Gao, X.; Altarawneh, M.; Hayashi, J.-I.; Zhang, M.; Dlugogorski, B.Z. Analytical Procedure for Proximate Analysis of Algal Biomass: Case Study for Spirulina platensis and Chlorella vulgaris. Energy Fuels 2019, 34, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, F.J.; McCarty, G.W.; Reeves, J.B. Pyrolisis-MS and FT-IR analysis of fresh and decomposed dairy manure. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2006, 76, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, P.; Jiang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Li, J.; Yuan, M.; Ji, Y.; Chen, M.; Li, D.; Qiao, Y. Pyrolysis behavior and product distributions of biomass six group components: Starch, cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, protein and oil. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 216, 112777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ischia, M.; Perazzolli, C.; Maschio, R.D.; Campostrini, R. Pyrolysis study of sewage sludge by TG-MS and TG-GC-MS coupled analyses. J. Therm. Anal. 2006, 87, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Silva, L.; López-González, D.; García-Minguillán, A.; Valverde, J.L. Pyrolysis, combustion and gasification characteristics of Nannochloropsis gaditana microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 130, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Li, A.; Quan, C.; Du, L.; Duan, Y. TG–FTIR and Py–GC/MS analysis on pyrolysis and combustion of pine sawdust. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2013, 100, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Liao, Y.; Yu, Z.; Fang, S.; Ma, X. A study on co-pyrolysis of bagasse and sewage sludge using TG-FTIR and Py-GC/MS. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 151, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Pang, S.; Mercader, F.D.M.; Torr, K.M. The effect of biomass pretreatment on catalytic pyrolysis products of pine wood by Py-GC/MS and principal component analysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2018, 138, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, R.; Zhang, B.; Qiu, Q.; Wang, B.; Yang, H.; Ding, Y.; Wang, C. Pyrolysis of microalgae: A critical review. Fuel Process. Technol. 2019, 186, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmita, A.; Fischer, C.; Hodor, K.; Holtzer, M.; Roczniak, A. Thermal decomposition of foundry resins: A determination of organic products by thermogravimetry–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (TG–GC–MS). Arab. J. Chem. 2016, 11, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Mohanty, K. Kinetic analysis and pyrolysis behaviour of waste biomass towards its bioenergy potential. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 311, 123480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, G.P.B.; Santiañez, W.J.E.; Trono, G.C.; Montaño, M.N.E.; Araki, H.; Takeuchi, H.; Hasegawa, T. Seaweed biomass of the Philippines: Sustainable feedstock for biogas production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 38, 1056–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filer, J.; Ding, H.H.; Chang, S. Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) Assay Method for Anaerobic Digestion Research. Water 2019, 11, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Seadi, T.; Drosg, B.; Fuchs, W.; Rutz, D.; Janssen, R. Biogas digestate quality and utilization. In The Biogas Hand-Book; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2013; pp. 267–301. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Hong, J.; Jeong, S.; Chandran, K.; Park, K.Y. Interactions between substrate characteristics and microbial communities on biogas production yield and rate. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 303, 122934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Aguilar, H.A.; Kennedy-Puentes, G.; Gómez, J.A.; Huerta-Reynoso, E.A.; Peralta-Pérez, M.D.R.; de la Serna, F.J.Z.-D.; Pérez-Hernández, A. Practical and Theoretical Modeling of Anaerobic Digestion of Sargassum spp. in the Mexican Caribbean. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 30, 3151–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santín, C.; Doerr, S.H.; Merino, A.; Bucheli, T.D.; Bryant, R.; Ascough, P.; Gao, X.; Masiello, C. Carbon sequestration potential and physicochemical properties differ between wildfire charcoals and slow-pyrolysis biochars. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saidur, R.; Abdelaziz, E.; Demirbas, A.; Hossain, M.; Mekhilef, S. A review on biomass as a fuel for boilers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2262–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motte, J.-C.; Escudié, R.; Bernet, N.; Delgenes, J.-P.; Steyer, J.-P.; Dumas, C. Dynamic effect of total solid content, low substrate/inoculum ratio and particle size on solid-state anaerobic digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 144, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moset, V.; Al-Zohairi, N.; Møller, H. The impact of inoculum source, inoculum to substrate ratio and sample preservation on methane potential from different substrates. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 83, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlini, M.; Castellucci, S.; Moneti, M. Biogas Production from Poultry Manure and Cheese Whey Wastewater under Mesophilic Conditions in Batch Reactor. Energy Procedia 2015, 82, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, M.A.; Kebelmann, K.; Schartel, B.; Griffiths, G. Valorization of macroalgae digestate into aromatic rich bio-oil and lipid rich microalgal biomass for enhanced algal biorefinery performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 341, 130925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuenter, E.; Delbaere, C.; De Winne, A.; Bijttebier, S.; Custers, D.; Foubert, K.; Van Durme, J.; Messens, K.; Dewettinck, K.; Pieters, L. Non-volatile and volatile composition of West African bulk and Ecuadorian fine-flavor cocoa liquor and chocolate. Food Res. Int. 2020, 130, 108943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, J.L. Modeling of Biomass Torrefaction and Pyrolysis and Its Applications; Michigan Technological University: Houghton, MI, USA; ProQuest LLC: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Stelt, M.J.C.; Gerhauser, H.; Kiel, J.H.A.; Ptasinski, K.J. Biomass upgrading by torrefaction for the production of biofuels: A review. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 3748–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R.; Moore, M. Carbamic acid: Molecular structure and IR spectra. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 1999, 55, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, G. Identification of volatile organic compounds produced by algae. Egypt. J. Phycol. 2004, 5, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesemuyi, M.F. Pyrolysed Products from Lignocellulosic Wastes: Production, Characterisation and Their Effect on Soil Properties, Okra, Insect and Microbial Growth. Ph.D. Thesis, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman, J.; Patterson, H.H. Photodecomposition of the Carbamate Pesticide Carbofuran: Kinetics and the Influence of Dissolved Organic Matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1999, 33, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberman, J.; Taylor, A. Carbamate Toxicity; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De Llasera, M.G.; Bernal-González, M. Presence of carbamate pesticides in environmental waters from the northwest of Mexico: Determination by liquid chromatography. Water Res. 2001, 35, 1933–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, E.; Yi, H.; Choi, Y.; Cho, H.; Lee, K.; Moon, H. Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of carbamic acid 1-phenyl-3-(4-phenyl-piperazine-1-yl)-propyl ester derivatives as new analgesic agents. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 2434–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roscher, A.A.; Jussek, E.; Noguchi, T.; Franklin, S. Fatal accidental diglycolic acid intoxication. Bull. Soc. Pharmacol. Environ. Pathol. 1975, 3, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Wu, M.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Dong, W.; Zhou, J.; Jiang, M.; Xin, F. Current advances on biological production of fumaric acid. Biochem. Eng. J. 2019, 153, 107397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, J.; Mercader, P.; Giménez-Arnau, A. Dermatitis de contacto por dimetilfumarato. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas 2010, 101, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corma, A.; Leyva, A.; Rubio Marqués, P. Proceso de Obtención de Aminas Secundarias a Partir de Nitrobenceno en un Solo. Reactor. Patent Number ES2472344 A1, 20 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Naji, M.; Van Aelst, J.; Liao, Y.; D'Hullian, M.; Tian, Z.; Wang, C.; Gläser, R.; Sels, B.F. Pentanoic acid from γ-valerolactone and formic acid using bifunctional catalysis. Green Chem. 2019, 22, 1171–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Adhikari, N.; Jha, T. A pentanoic acid derivative targeting matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) induces apoptosis in a chronic myeloid leukemia cell line. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 141, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, W., Jr. Acrylic acid and derivatives. In Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, C.-S.; Mo, M.-H.; Gu, Y.-Q.; Zhou, J.-P.; Zhang, K.-Q. Possible contributions of volatile-producing bacteria to soil fungistasis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 2371–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, M.; Ma, H.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J. Comparative Study on the Pyrolysis Behaviors of Pine Cone and Pretreated Pine Cone by Using TGA–FTIR and Pyrolysis-GC/MS. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 3490–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, T.S.; Anandan, A.; Jegadeesan, M.; Appl, A.; Res, S. Identification of chemical compounds in Cissus quadrangularis L. Variant-I of different sample using GC-MS analysis. Arch. Appl. Sci. Res. 2012, 4, 1782–1787. [Google Scholar]

- Valasinas, A.; Reddy, V.K.; Blokhin, A.; Basu, H.S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Sarkar, A.; Marton, L.J.; Frydman, B. Long-chain polyamines (oligoamines) exhibit strong cytotoxicities against human prostate cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 4121–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, E.G.; O'Sullivan, M.G.; Kerry, J.P.; Kilcawley, K.N. Volatile compounds of six species of edible seaweed: A review. Algal Res. 2019, 45, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagahisa, E.; Kanno, N.; Sato, M.; Sato, Y. Occurrence of FreeD-Alanine in Marine Macroalgae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1995, 59, 2176–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Sato, M.; Kan-No, N.; Nakano, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Nagahisa, E. Alanine racemase activity in the microalga Thalassiosira sp. Fish. Sci. 2005, 71, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, K.; Tomoda, Y.; Nakamoto, Y.; Kawada, T.; Ishii, Y.; Nagata, Y. Alanine racemase from the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Amino Acids 2006, 32, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, R.M.; Saunders, B.; Ball, G.; Harris, R.C.; Sale, C. Effects of β-alanine supplementation on exercise performance: A meta-analysis. Amino Acids 2012, 43, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashi, R.T.; Desai, S.A.; Desai, P.S. Ethylamines as corrosion inhibitors for zinc in nitric acid. Asian J. Chem. 2008, 20, 4553. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, F.; Cui, X. Catalytic Amination for N-Alkyl Amine Synthesis; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, J.M. Butylamines. In Encyclopedia of Toxicology, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; p. 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Eckert, J. The mechanism of fungistatic action of sec-butylamine: I. Effects of sec-butylamine on the metabolism of hyphae of Penicillium digitatum. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1976, 6, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, V.; Jüttner, F. Excretion products of algae: Identification of biogenic amines by gas-liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry of their trifluoroacetamides. Anal. Biochem. 1977, 78, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, M.; Hartmann, T. The occurence and distribution of volatile amines in marine algae. Planta 1968, 79, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitani, A.M. Oil refining and products. In Encyclopedia of Energy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 4, pp. 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathaniel, C.R.; Neetha, M.; Anilkumar, G. Silver-catalyzed pyrrole synthesis: An overview. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2021, 35, e6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawale, H.; Kishore, N. Production of hydrocarbons from a green algae (Oscillatoria) with exploration of its fuel characteristics over different reaction atmospheres. Energy 2019, 178, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, L.V.; González-Morales, S.; Mendoza, A.B. Ácido benzoico: Biosíntesis, modificación y función en plantas. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agrícolas 2015, 6, 1667–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerlikaya, O.; Gucer, L.; Akan, E.; Meric, S.; Aydin, E.; Kinik, O. Benzoic acid formation and its relationship with microbial properties in traditional Turkish cheese varieties. Food Biosci. 2021, 41, 101040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheler, T.R.; Araújo, L.F.; Silva, C.C.D.; Gomes, G.A.; Prata, M.F.; Gomide, C.A. Uso de ácido benzoico na dieta de leitões. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2009, 38, 2182–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pérez Alvarado, M.A.; Cervantes López, J.; Braña Varela, D.; Mariscal Landín, G.; Cuarón Ibargüengoytia, J.A. Ácido benzoico y un producto basado en especies de Bacillus para proteger la productividad de los lechones y al ambiente. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pecu. 2013, 4, 447–468. [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Pérez, L.; Gaucín-Delgado, J.M.; Preciado-Rangel, P.; Fortis-Hernández, M.; Valenzuela-García, J.R.; Ayala-Garay, A.V. Efecto del ácido benzoico en la capacidad antioxidante de germinados de trigo. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agrícolas 2016, 17, 3397–3404. [Google Scholar]

- Chinaka, I.C.B.; Okwudili, O.S.; Nkiru, D.-A.I. Chemical Composition, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Properties of Chloroform Fraction of Platycerium Bifurcatum. Adv. Res. Life Sci. 2018, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jinshun, L. Study on the chemical composition of the volatile oil in Ligustrum lucidum. Zhongguo Yao Xue Za Zhi 2005, 40, 178–180. [Google Scholar]

- Dashtban, M.; Gilbert, A.; Fatehi, P. Production of furfural: Overview and challenges. J. Sci. Technol. Forest Prod. Process 2012, 2, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, S.; De, S.; Saha, B.; Alam, I. Advances in conversion of hemicellulosic biomass to furfural and upgrading to biofuels. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 2025–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biller, P.; Ross, A. Pyrolysis GC–MS as a novel analysis technique to determine the biochemical composition of microalgae. Algal Res. 2014, 6, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhyani, V.; Bhaskar, T. Pyrolysis of Biomass. Cellulose. In Biofuels: Alternative Feedstocks and Conversion Processes for the Production of Liquid and Gaseous Biofuels; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 217–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, B.; Bjerrum, J.; Lundén, R.; Prydz, H. Methylated Taurines and Choline Sulphate in Red Algae. Acta Chem. Scand. 1955, 9, 1323–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.H.; Ito, S.; Maeyama, S.; Schaffer, S.W.; Murakami, S.; Ito, T. In Vivo and In Vitro Study of N-Methyltaurine on Pharmacokinetics and Antimuscle Atrophic Effects in Mice. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 11241–11246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.-M.; Luo, Y.-S.; Wang, H.; Peng, W.-X.; Wu, Y.-Q.; Zhang, D.-Q.; Ma, Q.-Z. Determination of chemical components of benzene/ethanol extractive of beech wood by GC/MS. In Proceedings of the 2008 2nd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering, Shanghai, China, 16–18 May 2008; pp. 2776–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.L.; Lien, E.J.; Tokes, Z.A. Synthesis, biological evaluation, and quantitative structure-activity relationship analysis of 2-hydroxy-1H-isoindolediones as new cytostatic agents. J. Med. Chem. 1987, 30, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Huang, M.; Zhang, S.; Li, L.; Li, M.; Sun, J.; Wu, L.; Guan, Q.; Zhang, W. Design, synthesis and bioevaluation of 6-aryl-1-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazoles as tubulin polymerization inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 226, 113826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, G.; Paira, P.; Cheong, S.L.; Vamsikrishna, K.; Federico, S.; Klotz, K.-N.; Spalluto, G.; Pastorin, G. Discovery of simplified N2-substituted pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine derivatives as novel adenosine receptor antagonists: Efficient synthetic approaches, biological evaluations and molecular docking studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 1751–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, S.; Tailor, Y.K.; Rushell, E.; Kumar, M. Use of sustainable organic transformations in the construction of heterocyclic scaffolds. In Green Approaches in Medicinal Chemistry for Sustainable Drug Design; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 245–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vankar, P.S. Essential oils and fragrances from natural sources. Resonance 2004, 9, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinty, D.; Lapczynski, A.; Bhatia, S.; Letizia, C.; Api, A. Fragrance material review on 7-octen-2-ol, 2-methyl-6-methylene-, dihydro derivative. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, S46–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanlong, Z.; Fangyan, Y.; Zhengkun, W. Study of chemical communication based on urine in tree shrews Tupaia belangeri (Mammalia: Scandentia: Tupaiidae). Eur. ZoÖl. J. 2017, 84, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menotta, M.; Gioacchini, A.M.; Amicucci, A.; Buffalini, M.; Sisti, D.; Stocchi, V. Headspace solid-phase microextraction with gas chromatography and mass spectrometry in the investigation of volatile organic compounds in an ectomycorrhizae synthesis system. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2003, 18, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Bleecker, A.B.; Caldwell, K.S.; Langridge, P.; Powell, W. Ethylene Biology. More Than a Gas. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 2895–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meléndez-Ortiz, H.I.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Concheiro, A.; Jiménez-Páez, V.M.; Bucio, E. Modification of medical grade PVC with N-vinylimidazole to obtain bactericidal surface. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2016, 119, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öncül, A.; Çoban, K.; Sezer, E.; Şenkal, B.F. Inhibition of the corrosion of stainless steel by poly-N-vinylimidazole and N-vinylimidazole. Prog. Org. Coat. 2011, 71, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzate-Gaviria, L.; Domínguez-Maldonado, J.; Chablé-Villacís, R.; Olguin-Maciel, E.; Leal-Bautista, R.M.; Canché-Escamilla, G.; Caballero-Vázquez, A.; Hernández-Zepeda, C.; Barredo-Pool, F.A.; Tapia-Tussell, R. Presence of Polyphenols Complex Aromatic “Lignin” in Sargassum spp. from Mexican Caribbean. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moralı, U.; Şensöz, S. Pyrolysis of hornbeam shell (Carpinus betulus L.) in a fixed bed reactor: Characterization of bio-oil and bio-char. Fuel 2015, 150, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).