Abstract

This study investigated the effects of environmentally friendly soil amendments—processed red clay (PRC) and rice husk (RH)—on early establishment, growth characteristics, phytochemical accumulation, and soil chemical properties in wild-simulated ginseng (WSG; Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) cultivated under forest conditions. PRC was produced through alkali-assisted thermal processing to improve material homogeneity and enhance plant-available mineral components, particularly silicon. We hypothesized that the combined application of PRC and RH would improve soil chemical conditions and thereby support WSG growth and phytochemical accumulation under low-input cultivation systems. Four treatments were evaluated in a randomized complete block design with four replicates: non-treated control (NMNF), PRC alone (NMPRC), RH alone (RHNF), and combined PRC and RH (RHPRC). Growth responses were assessed in one-year-old and seven-year-old WSG, including germination rate, seedling vigor index, growth traits, photosynthetic pigment composition, total polyphenol content, ginsenoside profiles, and soil chemical properties. The RHPRC treatment significantly increased germination rate and seedling vigor compared to the non-treated control and showed consistently greater biomass accumulation across cultivation stages. RH application was primarily associated with improved early establishment and increased total polyphenol content, particularly during the early growth stage, whereas PRC application was associated with enhanced root development and age-dependent increases in selected ginsenosides. Soil analyses indicated that PRC application increased available phosphorus and exchangeable cation contents, with the most stable improvements observed under combined PRC and RH treatment. Overall, the results indicate that integrated mineral–organic soil management using PRC and RH can improve soil chemical propertise and support long-term growth and phytochemical accumulation in WSG cultivated under forest conditions. This approach offers a practical, low-input strategy for enhancing the sustainability of WSG cultivation while reducing reliance on synthetic fertilizers.

1. Introduction

Sustainable soil management has become a central challenge in modern agriculture [1,2,3], as the prolonged and intensive use of chemical fertilizers has been associated with soil acidification, nutrient imbalance, disruption of microbial communities, and the long-term decline of soil fertility [4,5,6]. These issues are particularly pronounced in cropping systems that rely on continuous fertilization to sustain productivity, raising concerns regarding both environmental integrity and crop quality [7,8]. Consequently, increasing attention has been directed toward alternative soil amendment strategies that enhance nutrient availability and soil function while minimizing dependence on synthetic inputs.

Wild-simulated ginseng (WSG; Panax ginseng Meyer) represents a unique cultivation system that is especially sensitive to soil conditions [9]. Unlike field-cultivated ginseng, WSG is grown under forest conditions with minimal external input and is subject to strict regulations that largely prohibit the use of chemical fertilizers [10,11,12]. The crop requires long cultivation periods [10,11], often exceeding six years, during which gradual soil degradation, nutrient depletion, and changes in soil chemical properties can adversely affect plant growth and the accumulation of bioactive compounds [13,14]. These challenges highlight the need for soil management approaches that are compatible with low-input, regulation-constrained systems while sustaining both productivity and phytochemical quality.

Mineral-based soil amendments have been widely explored as alternatives to chemical fertilizers due to their capacity to improve soil structure, nutrient retention, and chemical stability [15,16]. Red clay, which is abundant in many regions [17] and characterized by high contents of iron and aluminum oxides as well as clay minerals, has attracted interest for its potential to enhance cation exchange capacity and regulate soil pH [18,19]. Previous studies have demonstrated that red clay application can improve soil physicochemical properties and nutrient availability in agricultural soils [15,20,21]. However, these studies have largely focused on short-term responses or annual cropping systems [22,23,24,25], with limited consideration of long-term perennial or medicinal crops.

Organic amendments derived from agricultural by-products have also received attention for their role in sustainable soil management [26]. Rice husk (RH), a by-product generated in large quantities during rice processing [27], is rich in silica and organic carbon and has been reported to improve soil aeration, water retention, and microbial activity [28,29,30,31]. The incorporation of RH into soils has been shown to enhance soil physical properties and contribute to organic matter accumulation [30,32]. Nevertheless, most investigations have emphasized its function as a soil conditioner, with relatively little emphasis on its interaction with mineral amendments or its influence on the accumulation of secondary metabolites in high-value medicinal crops.

Despite the growing body of literature on mineral and organic soil amendments, their combined application in WSG cultivation remains insufficiently explored. Existing studies on ginseng have primarily examined cultivation environments [13,33,34], shading conditions [35,36], or ginsenoside profiles independently [37,38,39], while soil amendment strategies compatible with regulatory constraints have received comparatively little attention. In particular, there is a lack of systematic evaluations that integrate soil chemical changes, plant growth responses, and phytochemical accumulation across different cultivation stages under forest-based conditions.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to systematically assess the individual and combined effects of processed red clay (PRC) and RH on soil chemical properties, growth characteristics, and phytochemical composition of WSG cultivated under forest conditions. To capture both early and advanced cultivation stages, one-year-old and seven-year-old plants were evaluated. By integrating mineral and organic amendments within a long-term, low-input cultivation system, this study aims to elucidate sustainable soil management strategies that support both plant performance and bioactive compound accumulation in WSG. The outcomes of this study are particularly relevant to WSG farmers in South Korea, where forest-based cultivation systems and strict restrictions on chemical fertilizer use necessitate alternative soil management approaches. The findings are expected to provide a scientific basis for environmentally sound and regulation-compliant soil amendment practices applicable to high-value medicinal crops cultivated in agroforestry systems

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

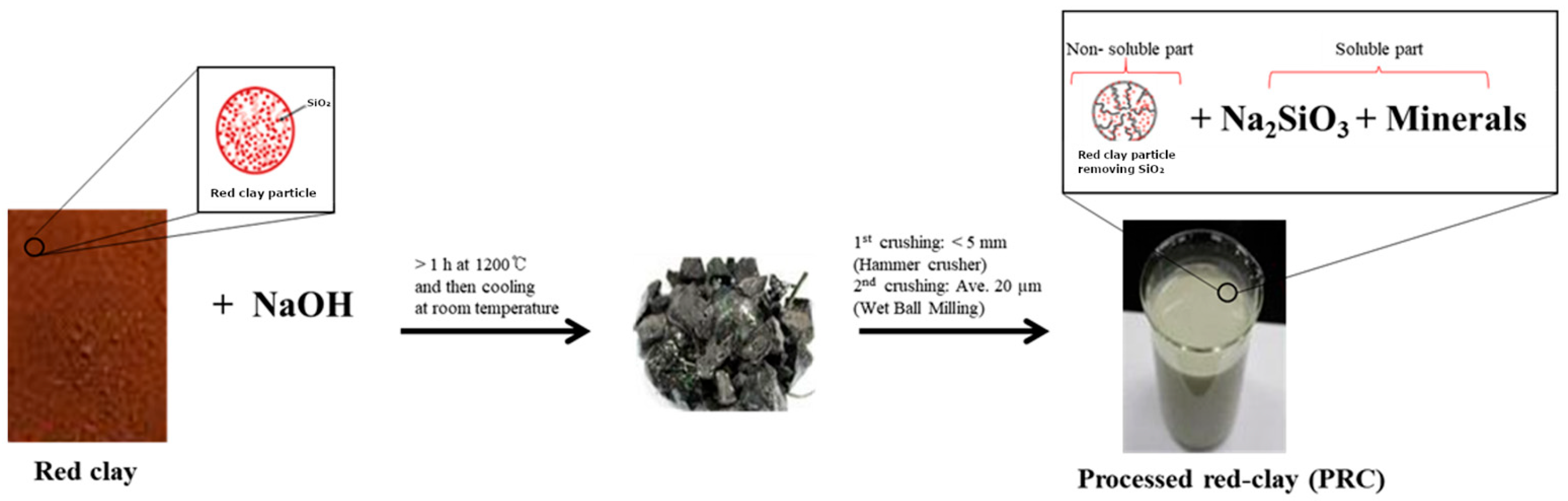

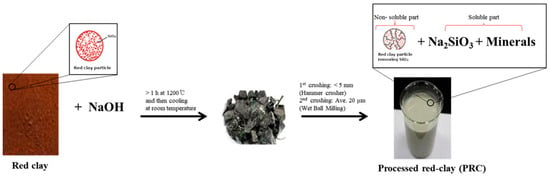

Seeds of WSG, cultivated under forest conditions in Namyangju, Korea, and certified under a geographical indication (GI) collective trademark (No. 44-0000293), were used for direct seeding and cultivation. The planting material represents a locally adapted wild-simulated ginseng landrace rather than a standardized commercial cultivar, reflecting typical production systems used in forest-based WSG cultivation. WSG plants were partially harvested and measured on 22 June 2015 for 1-year-old plants (WSG-1), and on 27 June 2021 for 7-year-old plants (WSG-7). Red clay (particle size < 3 mm) was obtained from Boryeong Hwangto (Boryeong Hwangto Co., Boryeong, Republic of Korea) for further processing. The red clay was mixed with NaOH and heated at 1200 °C for 3 h in an electric furnace (Ajeon Heating Industrial Co., Namyangju, Republic of Korea), followed by cooling at 24 °C for 24 h (Figure 1). The processed material was subsequently crushed using a hammer mill (Korea Pulverizing Machinery Co, Ltd., Incheon, Republic of Korea) and further ground using a ball mill (Daihan Scientific Co. Ltd., Wonju, Republic of Korea).

Figure 1.

Scheme reactions for the production of processed red clay (PRC) from red clay.

PRC was obtained as a slurry that separated into a solid fraction, consisting of red clay with SiO2 removed, and a liquid fraction containing Na2SiO3, according to the following reaction:

The chemical composition of PRC consisted of SiO2 (31.1%), Na2O (25.6%), Al2O3 (19.0%), Fe2O3 (7.47%), K2O (1.30%), CaO (0.95%), TiO2 (0.94%), MgO (0.73%), and others (13.91%) (Table 1) [40]. Chemical composition analysis was conducted at the Korea Testing & Research Institute (KTR; Gwacheon, Republic of Korea), a laboratory accredited by the Korea Laboratory Accreditation Scheme (KOLAS).

Table 1.

Composition of red clay and processed red clay (PRC) (unit: %).

2.2. Experimental Site Conditions and Treatment Design

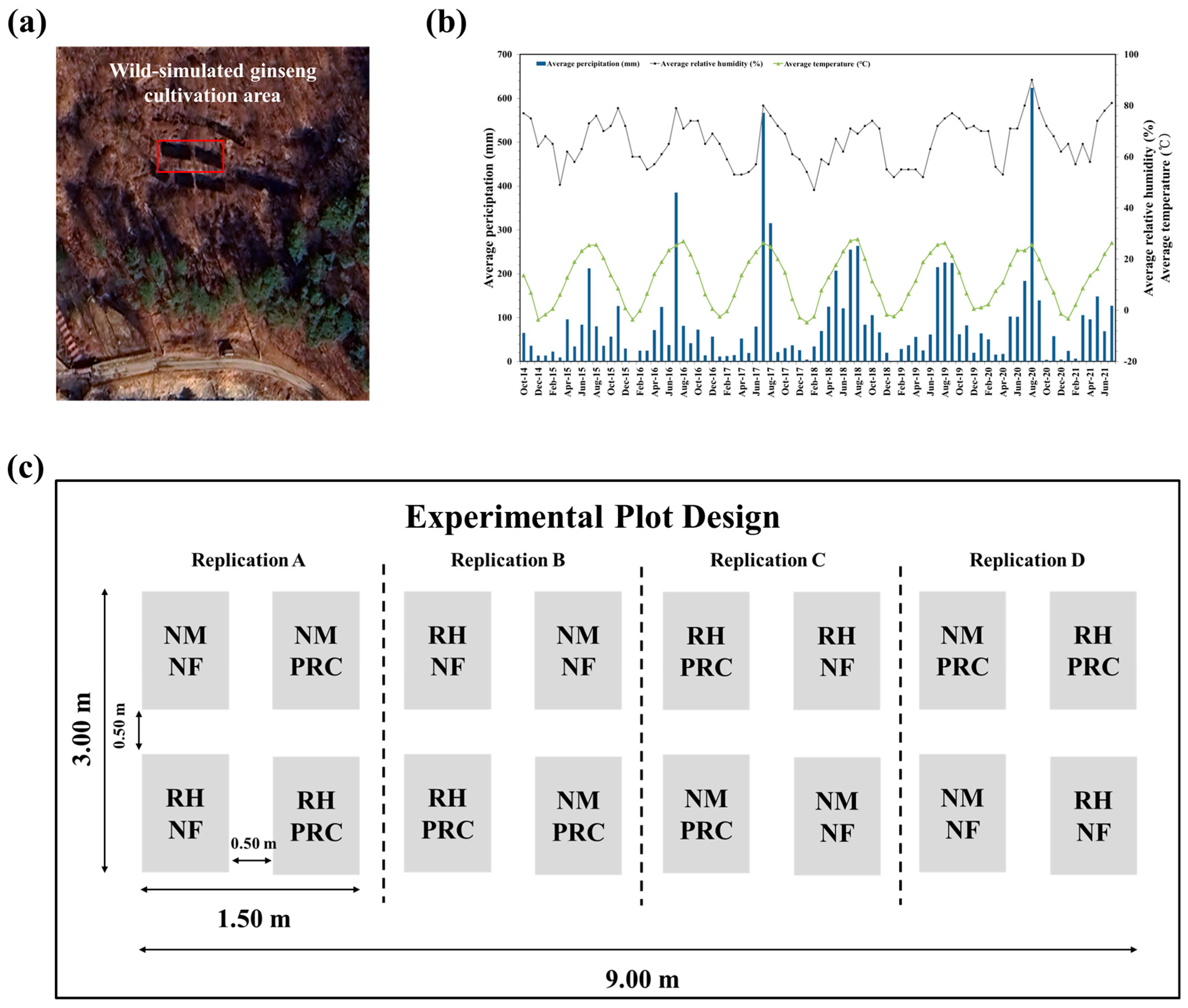

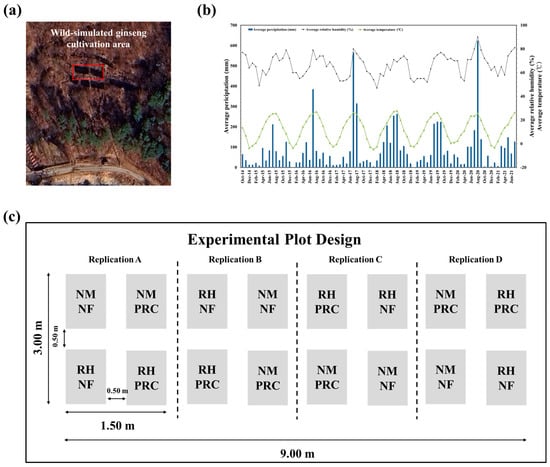

This study was conducted at the Dongguk University Educational Forest in Ungilsan, Gyeong-gi Province (N 37°33′48″, E 127°17′29″, 105 m above sea level) (Figure 2a). The slope of the study area was 16° facing south, and the forest consisted of broad-leaved trees with a diameter at breast height of <6 cm and an estimated stand age of less than ten years. The experimental soil was classified as Cambisol according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) soil classification system and exhibited a subangular blocky structure [41]. The soil texture was sandy loam, consisting of 55% sand, 21% silt, and 24% clay. The soil chemical properties of the experimental site prior to planting were as follows: pH 4.60; electrical conductivity (EC), 1.22 dS m−1; organic matter (OM), 50.00 g kg−1; available P2O5, 72.00 mg kg−1; available SiO2, 65.00 mg kg−1; exchangeable Ca2+ 1.50 cmol kg−1, Mg2+ 0.40 cmol kg−1; K+, 0.27 cmol kg−1; and total nitrogen (TN), 0.17%.

Figure 2.

Geographical location of the wild-simulated ginseng (WSG) cultivation site, climatic conditions during the cultivation period and experimental plot design with the timeline of processed red clay (PRC) treatment. (a) Aerial photograph showing the geographical location of the WSG cultivation site, with the experimental area indicated by a red box. (b) Monthly average precipitation, relative humidity, and air temperature during the cultivation period. (c) Schematic illustration of the experimental plot design, including four treatment conditions and buffer zones established between adjacent plots to minimize cross-plot interference. The treatments consisted of non-mulching and non-fertilizer (NMNF; water only, 2.5 L), non-mulching with PRC application (NMPRC; 200-fold diluted PRC, 2.5 L), rice husk mulching without PRC (RHNF; water only, 2.5 L), and the combined application of PRC and rice husk mulching (RHPRC; 200-fold diluted PRC, 2.5 L). The timing of PRC application during the cultivation period is also illustrated.

During the first cultivation period, from October 2014 to June 2015, the average precipitation was 41.6 mm, the average air temperature was 8.5 °C, and the average relative humidity was 64.0%. Between the first and second harvesting periods (2015–2021), the average air temperature was 12.6 °C, with a minimum of 7.5 °C, a maximum of 18.5 °C, and an average precipitation of 91.7 mm (Figure 2b) [42].

The field experiment was conducted using a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with four replications (Figure 2c). Each experimental plot measured 0.50 m × 1.25 m and was assigned one of four treatment conditions. On 26 November 2014, 425 ginseng seeds were uniformly broadcast in each plot. To evaluate the effects of RH mulching, seeds in the designated plots were evenly covered with RH to a thickness of 0.5 cm immediately after sowing.

PRC was initially applied to the designated plots, followed by three additional applications prior to seed germination. The first PRC application was conducted on 7 April 2015, and the remaining applications were performed at weekly intervals thereafter.

The four treatment conditions were as follows: non-mulching and non-fertilizer (NMNF; water only, 2.5 L), PRC application without RH mulching (NMPRC; 200-fold diluted PRC, 2.5 L), RH mulching without PRC (RHNF; water only, 2.5 L) and the combined application of PRC with RH mulching (RHPRC; 200-fold diluted PRC, 2.5 L). PRC solution or water was applied uniformly to the soil surface, whereas RH was applied as a surface mulch layer in the designated treatments.

To minimize potential cross-plot interference, buffer zones measuring 0.50 m × 1.25 m were established between adjacent plots. No soil amendments or fertilizer were applied within the buffer zones (0.50 m), and these areas were excluded from all sampling and measurements.

2.3. Seed Germination, Seedling Growth and Vigor Index (SVI)

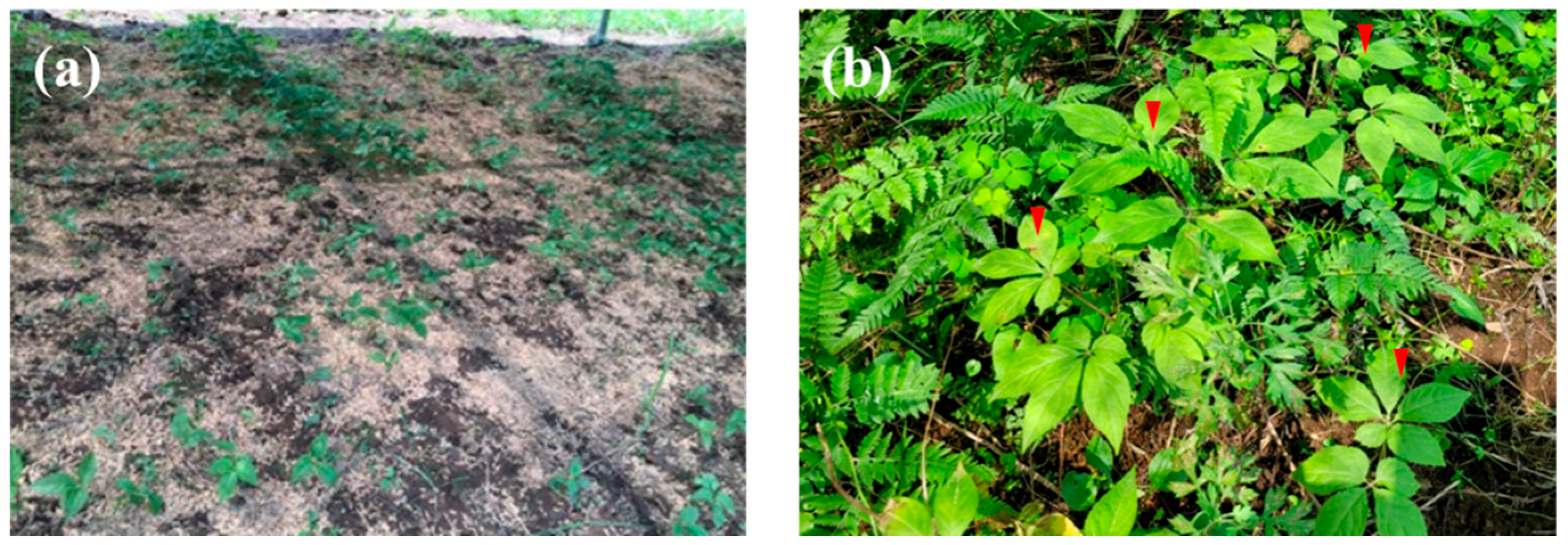

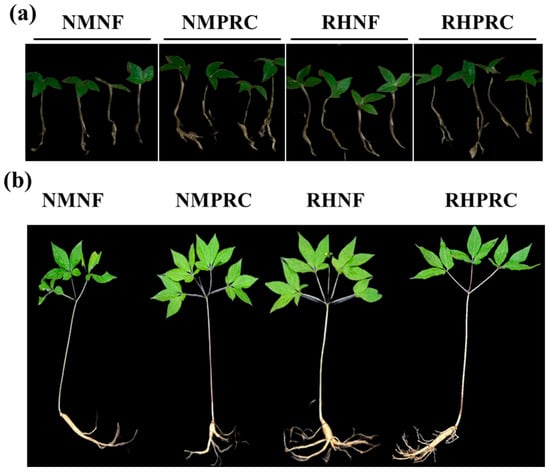

The germination rate, seedling growth characteristics, and seedling vigor index (SVI) were evaluated (Figure 3). Seed germination and seedling vigor index (SVI) were evaluated only in one-year-old WSG, as these indices are conventionally applied to assess early establishment performance and are not biologically relevant at later developmental stages.

Figure 3.

Morphological appearances of wild-simulated ginseng (WSG) following processed red clay (PRC) application. (a) 1-year-old WSG seedlings; (b) 7-year-old WSG plants (indicated by red arrows).

The germination rate was calculated as the number of germinated seeds divided by the total number of seeds. Seedling growth was assessed by measuring shoot length, root length, fresh weight, and the number of fine roots after separating plants into shoot and root components.

The SVI was determined according to the method described by [43], using the following formula:

2.4. Measurement of Photosynthetic Pigments in the Leaves

To analyze chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll (a + b), and carotenoid contents, twelve leaf samples were collected from each treatment and cut into approximately 1 mm pieces. Fresh leaf material (0.1 g) was placed into amber vials, and 8 mL of 80% (v/v) acetone was added. The samples were extracted by incubating the vials in a cool, dark place for 7 days. Absorbance was measured at 663, 645, and 470 nm using a UV/VIS spectrophotometer (UV-2100, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Chlorophyll and carotenoid contents were calculated using the equations described by Mackinney (1941) [44] and Arnon (1949) [45].

2.5. Measurement of Total Polyphenol Content (TPC)

Total polyphenol content (TPC) was determined in the shoot and root components of WSG using the Folin–Ciocalteu method [46]. Briefly, 0.1 g of freeze-dried powdered sample was extracted with 10 mL of 80% (v/v) ethanol, shaken for 10 min, and then sonicated at 80 °C for 1 h using an ultrasonic bath (Branson 8800, Branson Ultrasonics, Brookfield, CT, USA). The extract was adjusted to a final volume of 50 mL and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min (2236R, Gyrozen Inc., Deajeon, Republic of Korea). An aliquot of the supernatant (250 μL) was mixed with 250 μL of Folin–Ciocalteu Reagent (50%, v/v) and 2 mL distilled water. After equilibration for 5 min, 250 μL of sodium carbonate solution (15%, w/v) was added. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 60 min, and absorbance was measured at 760 nm using a UV/VIS spectrophotometer (UV-2100, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Tannic acid was used as the standard for calibration.

2.6. Measurement of Ginsenoside Contents

Approximately 1.0 g of dried WSG sample was extracted with 50 mL of 50% (v/v) methanol under reflux for 1 h in a water bath maintained at 70–80 °C, and then centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min to collect the supernatant. After cleanup using a C18 solid phase extraction (SPE) cartridge, the extract was filtered through a 0.22 µm syringe filter and analyzed by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) (ACQUITY TQD, Waters, Milford, MA, USA).

Chromatographic separation was performed on an ethylene-bridged hybrid (BEH) C8 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 µm; Waters, Milford, MA, USA) under UPLC conditions. The mobile phase consisted of (A) 0.1% formic acid in water and (B) acetonitrile. Gradient elution was applied as follows: 80A:20B at 0 min, 68A:32B at 2 min, 48A:52B at 20 min, 20A:80B at 26 min, and 80A:20B at 30 min.

2.7. Soil Sampling and Analysis

Soil samples were collected from each plot after the harvested of WSG-1 and WSG-7 in June 2015 and June 2021, respectively. Samples were taken from the 0–20 cm topsoil layer using a hand shovel, air-dried at room temperature, and passed through a 2 mm sieve prior to soil property analysis [47]. Soil pH was measured using a pH meter in soil-to-distilled-water suspension (1:5, w/v). Electrical conductivity (EC) was determined in a soil-to-water suspension (1:5) using an EC meter. Organic matter (OM) content was analyzed using the Tyurin method [48]. Total nitrogen (TN) was determined using the Kjeldahl method [49], and available P2O5 was measured using the Lancaster method [50]. Available SiO2 was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 700 nm after extraction with a 1 N NaOAc buffer (pH 4.0). Exchangeable cations (K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ and Na+) were extracted with 1N NH4OAc and analyzed using an ICP-OES spectrometer (Optima 8300, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and significant differences among means were determined using Duncan’s multiple-range test at a significance level of p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 28.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Seed Germination Rate and Seedling Vigor Index (SVI) of 1-Year-Old Wild-Simulated Ginseng (WSG-1)

The germination rate of the NMNF group was 16.18% (Table 2). In contrast, germination rates in the treated plots ranged from 29.47% to 38.97%. The seedling vigor index (SVI) was significantly enhanced by all treatments. The highest SVI was observed in the RHPRC group (511.63), representing an approximately 2.63-fold increase compared with the NMNF group (194.87), which exhibited the lowest value. Treatments with PRC or RH alone also resulted in significantly higher SVI values than NMNF, with increases of approximately 2.17-fold (NMPRC) and 2.26-fold (RHNF), respectively.

Table 2.

Seed germination rate and vigor index under different treatments in 1-year-old wild-simulated ginseng (WSG-1).

3.2. Growth Characteristics

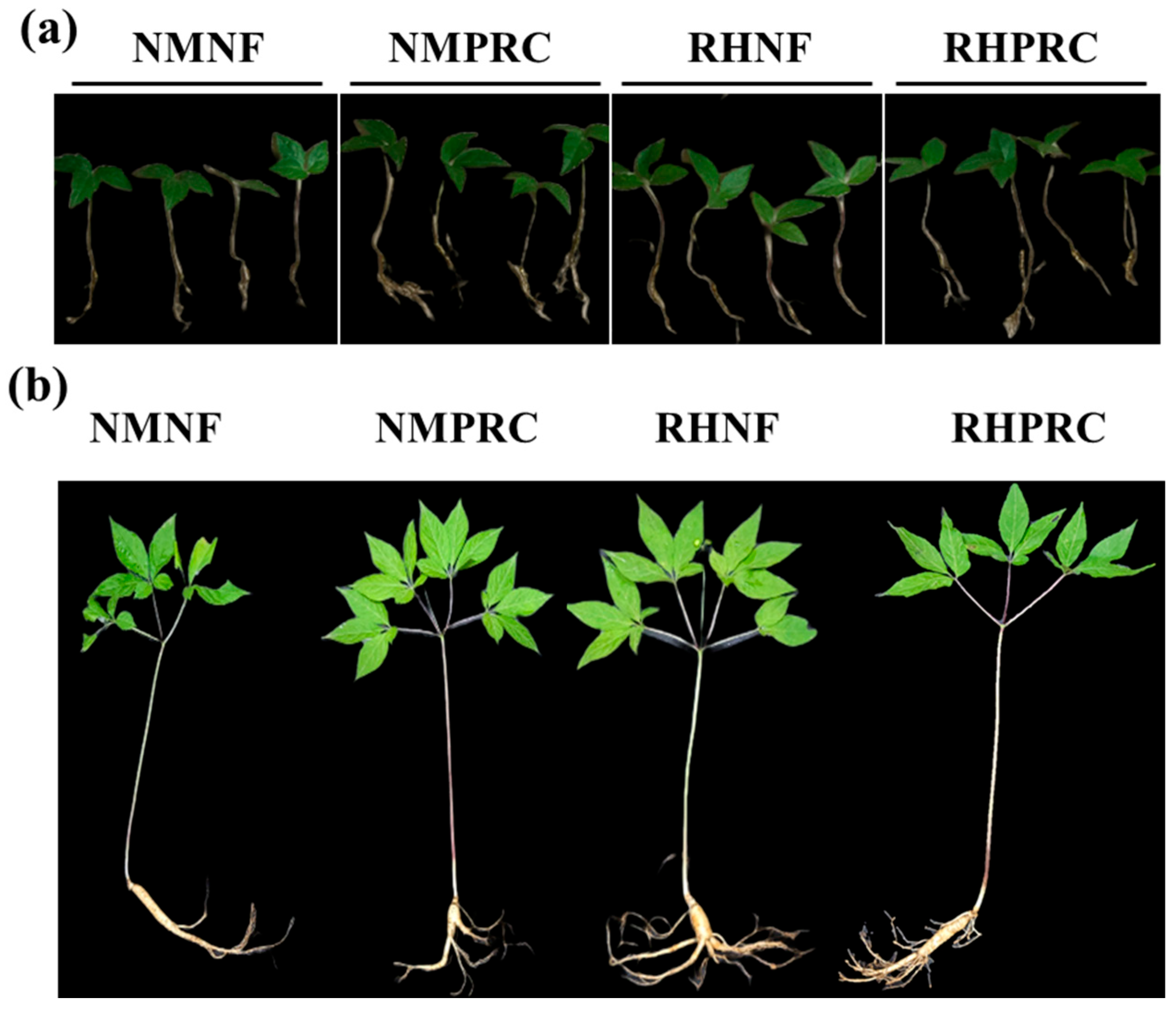

The morphological characteristics of WSG-1 and WSG-7 under each treatment are shown in Figure 4. For growth analysis, plants were separated into shoot and root components and measured accordingly (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Appearances of wild-simulated ginseng (WSG) under four treatment conditions. (a) 1-year-old WSG seedlings; (b) 7-year-old WSG plants. NMNF (non-mulching and non-fertilizer, water only, 2.5 L); NMPRC (non-mulching with processed-red clay (PRC), 200-fold diluted PRC, 2.5 L); RHNF (rice husk (RH) mulching with water only, 2.5 L); RHPRC (RH mulching with PRC, 200-fold diluted PRC, 2.5 L).

Table 3.

Growth characteristics of 1-year-old and 7-year-old WSG under different treatments.

In WSG-1, the longest shoot length was observed in the NMNF treatment (12.56 cm). Shoot length decreased by 19.51%, 14.33%, and 16.00% in the NMPRC, RHNF, and RHPRC treatments, respectively (p < 0.001). In contrast, shoot fresh weight increased by 7.14% in RHNF (0.15 g) and by 21.43% in RHPRC (0.17 g) compared with NMNF (0.14 g) (p < 0.01).

In WSG-7, shoot growth was markedly promoted by PRC application. The longest shoots were recorded in the RHPRC group (21.57 cm), representing a 32.09% increase compared with NMNF (16.33 cm). Shoot fresh weight was also highest in RHPRC (2.90 g), corresponding to an 84.71% increase relative to NMNF (p < 0.01).

In WSG-1, root length increased by 11.17% in NMPRC (4.18 cm) and by 21.01% in RHPRC (4.55 cm) compared with NMNF (3.76 cm) (p < 0.001). Root fresh weight increased substantially, with increases of 50.00% in NMPRC and RHNF (0.09 g) and 83.33% in RHPRC (0.11 g) relative to NMNF (0.06 g) (p < 0.01). Root diameter did not differ significantly among treatments.

In WSG-7, root growth was markedly enhanced by the combined PRC and RH treatment. Although root length did not differ significantly from NMNF, root diameter and fresh weight in the RHPRC treatment increased by 32.18% (1.14 mm) and 60.87% (3.70 g), respectively, compared with NMNF.

In WSG-1, the number of fine roots per plant was highest in the NMNF (6.23) and RHNF (6.16) groups. In contrast, NMPRC and RHPRC treatments showed reductions of 33.71% and 13.32%, respectively, compared with NMNF (p < 0.001). Conversely, in WSG-7, the number of fine roots increased substantially in the NMPRC and RHPRC treatments, reaching 41.89 and 39.14 roots per plant, respectively, nearly twice that of the NMNF group.

In WSG-1, the shoot-to-root (S/R) ratio decreased by 31.44%, 31.82%, and 34.85% in the NMPRC (1.81), RHNF (1.80), and RHPRC (1.72) treatments, respectively, compared with NMNF, indicating greater biomass allocation to root growth. In WSG-7, the S/R ratio ranged from 0.74 to 0.87 and did not differ significantly among treatments.

3.3. Photosynthetic Pigments in the Leaves

Chlorophyll content is a key parameter for evaluating plant physiological status and quality [51,52]. Plants regulate chlorophyll composition—including chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll (a + b), and the chlorophyll a/b ratio—in response to environmental conditions to optimize photosynthetic performance [53]. Accordingly, chlorophyll content was measured to assess the physiological responses of WSG leaves to PRC and RH treatments (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effects of different treatments on leaf photosynthetic pigments in 1-year-old and 7-year-old wild-simulated ginseng (WSG).

At the early stage (WSG-1), chlorophyll content tended to be higher under non-mulched conditions than under RH mulching. Under NMNF conditions, chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll were 8.46, 5.16, and 13.65 mg g−1 FW, respectively, representing the highest values among treatments (p < 0.001). In contrast, the lowest values were observed in the RHPRC group. The chlorophyll a/b ratio ranged from 1.64 to 1.75, with the highest value under NMPRC treatment, indicating that PRC application tended to increase the chlorophyll a/b ratio at the seedling stage.

Carotenoid content in WSG-1 differed significantly among treatments (p < 0.01). The highest carotenoid content was observed in the NMPRC group (0.86 mg g−1 FW), approximately 1.46-fold higher than in NMNF. RHNF and RHPRC exhibited similar carotenoid contents, which were higher than NMNF but did not differ significantly from each other.

In WSG-7, significant differences in chlorophyll parameters were observed among treatments (p < 0.001). Chlorophyll a ranged from 7.92 to 11.75 mg g−1 FW, with the highest value in RHNF and the lowest in NMPRC. Chlorophyll b showed a similar trend, resulting in the highest total chlorophyll (a + b) content in RHNF (19.25 mg g−1 FW), representing a 23.16% increase compared with NMNF. The chlorophyll a/b ratio ranged from 1.32 to 1.86 and was highest in the RHPRC treatment.

3.4. Total Polyphenol Content in Shoots and Roots

The total polyphenol content of WSG-1 and WSG-7, measured separately in shoot and root tissues, is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Total polyphenol content in the shoots and roots of 1-year-old and 7-year-old wild-simulated ginseng (WSG-1 and WSG-7) under different treatments.

In WSG-1, shoot total polyphenol content ranged from 6.62 to 8.07 mg TAE g−1 DW. The highest value was observed in RHPRC, followed by RHNF, whereas NMNF and NMPRC showed significantly lower values (p < 0.01). Root total polyphenol content ranged from 0.95 to 1.51 mg TAE g−1 DW, with the highest value recorded in the RHPRC treatment, representing an approximately 17.97% increase compared with NMNF. Overall, polyphenol concentrations were significantly higher in shoots than in roots at the seedling stage.

In WSG-7, TPC levels increased markedly compared with WSG-1. Relative to NMNF, shoot and root total polyphenol content increased by approximately 11.0-fold and 8.8-fold, respectively. Shoot total polyphenol content ranged from 76.35 to 102.62 mg TAE g−1 DW, with the highest values observed in PRC-treated groups. Root total polyphenol content ranged from 11.26 to 14.40 mg TAE g−1 DW, with NMPRC and RHPRC showing the highest values, corresponding to an approximately 34% increase compared with NMNF (p < 0.001).

3.5. Comparison of Ginsenoside Content of 1-Year-Old and 7-Year-Old Wild-Simulated Ginseng (WSG)

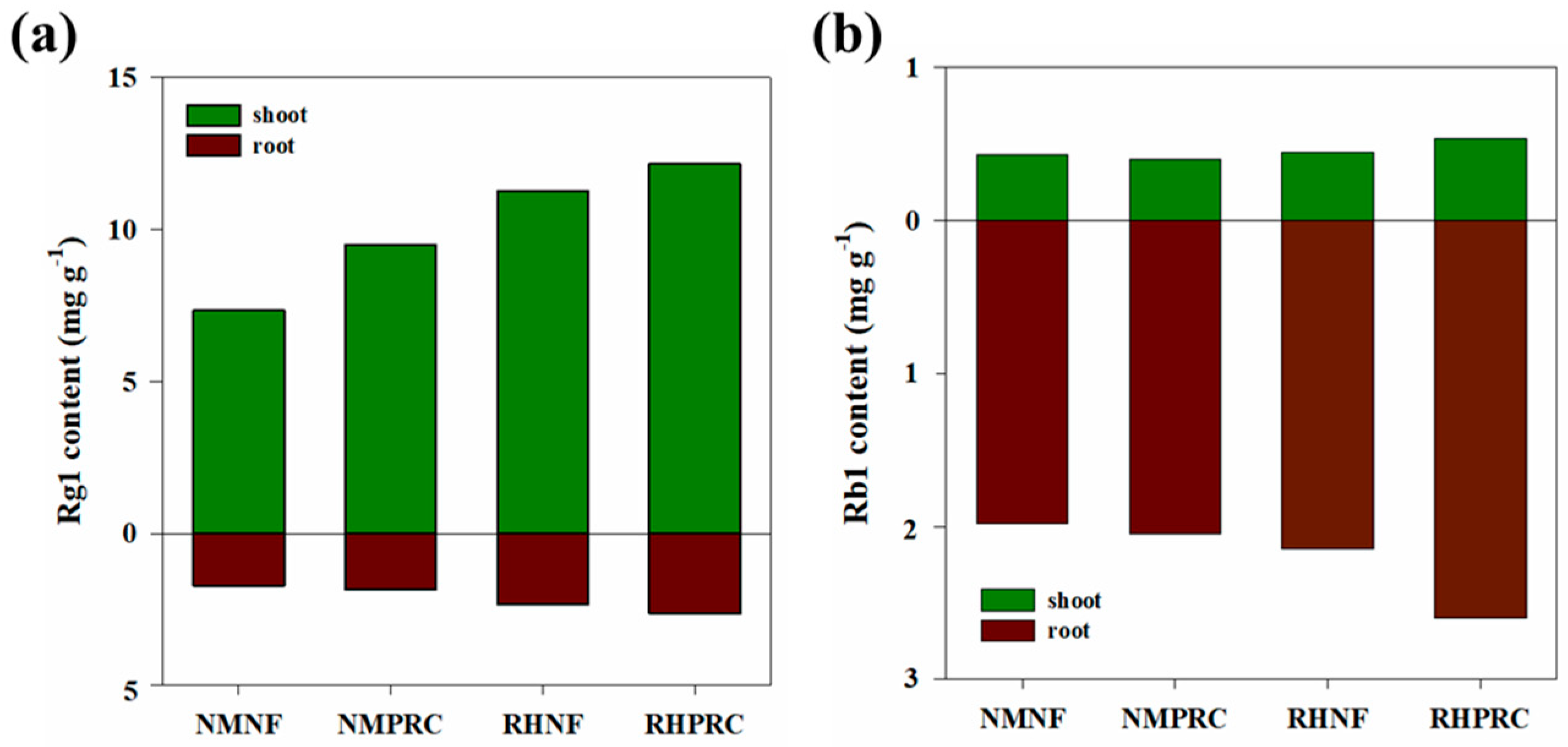

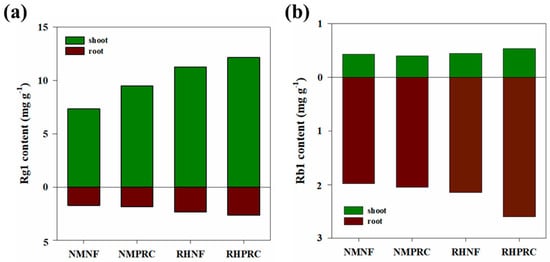

Ginsenosides are classified into protopanaxadiol (PPD), protopanaxatriol (PPT), and oleanane types based on their chemical structures [54,55]. To evaluate the effects of PRC and RH treatments on ginsenoside accumulation in WSG-1, Rb1 (PPD type) and Rg1 (PPT type) were selected as representative compounds (Figure 5) [56,57,58]. In WSG-1, Rg1 content was consistently higher in shoots than in roots. Compared with NMNF, shoot Rg1 content increased by 29.14%, 53.31%, and 65.62% in NMPRC, RHNF, and RHPRC, respectively. Root Rg1 content showed a similar trend, with the highest value observed in RHPRC. In contrast, Rb1 content was higher in roots than in shoots across all treatments. Although shoot Rb1 content did not differ significantly among NMNF, NMPRC, and RHNF, both shoot and root Rb1 contents tended to increase under RHPRC treatment.

Figure 5.

Rg1 and Rb1 contents in (a) shoot and (b) root under different treatments in 1-year-old wild-simulated ginseng (WSG-1). NMNF (non-mulching and non-fertilizer, water only, 2.5 L); NMPRC (non-mulching with processed-red clay (PRC), 200-fold diluted PRC, 2.5 L); RHNF (rice husk (RH) mulching with water only, 2.5 L); RHPRC (RH mulching with PRC, 200-fold diluted PRC, 2.5 L).

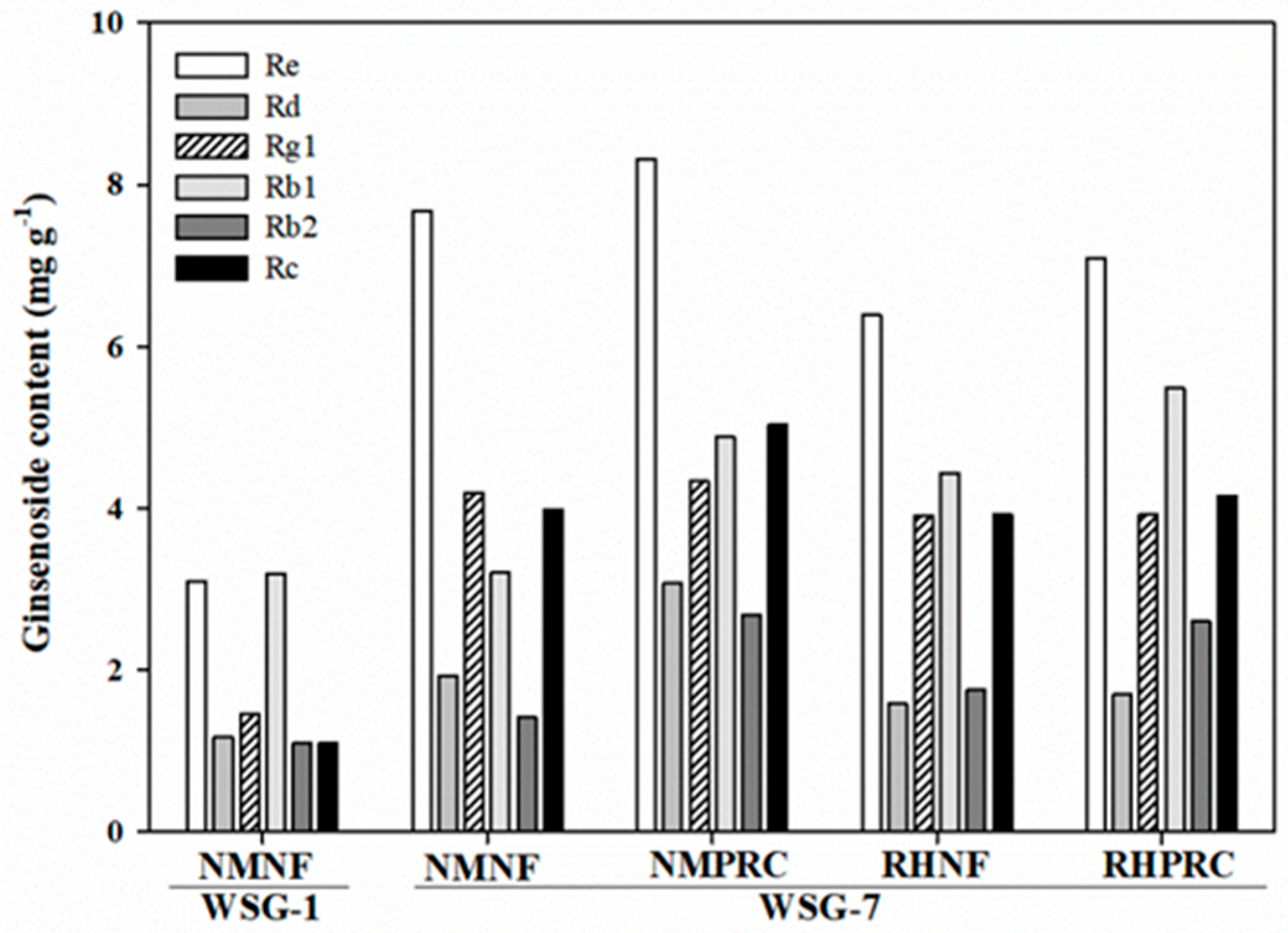

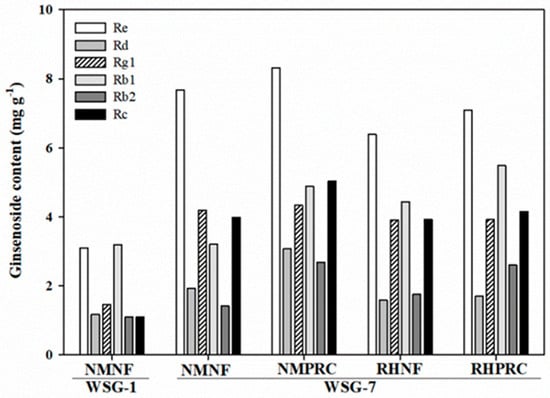

Comparative analysis between WSG-1 and WSG-7 revealed a marked increase in all analyzed ginsenosides in WSG-7 (Figure 6). PPT-type ginsenosides, particularly Re and Rg1, showed pronounced increases, exceeding two-fold compared with WSG-1. Among PPD-type ginsenosides, Rc increased more than three-fold in WSG-7. Within WSG-7, PRC-treated groups exhibited higher levels of PPD-type ginsenosides, especially Rb1 and Rb2, with the highest Rb1 content observed in RHPRC. These results indicate that long-term cultivation markedly enhances ginsenoside accumulation, with PRC application further promoting specific PPD-type ginsenosides at the mature stage.

Figure 6.

Ginsenoside contents (Re, Rd, Rg1, Rb1, Rg2, Rb2, and Rc) in the whole plant under different treatments in 1-year-old and 7-year-old wild-simulated ginseng (WSG-1 and WSG-7). NMNF (non-mulching and non-fertilizer, water only, 2.5 L); NMPRC (non-mulching with processed-red clay (PRC), 200-fold diluted PRC, 2.5 L); RHNF (rice husk (RH) mulching with water only, 2.5 L); RHPRC (RH mulching with PRC, 200-fold diluted PRC, 2.5 L).

3.6. Changes in Soil Chemical Properties

Soil chemical properties in the WSG cultivation sites are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Soil chemical properties of 1-year-old and 7-year-old wild-simulated ginseng (WSG-1 and WSG-7) under different treatments.

In WSG-1, soil pH ranged from 4.84 to 5.30 and was significantly higher in RH-treated plots than in non-mulched plots (p < 0.01). Soil EC was significantly lower in PRC- and RH-treated plots than in NMNF. Organic matter (OM) increased significantly under RH treatments, with the highest value in RHPRC. Available P2O5 was highest in NMPRC, whereas RH treatments reduced its levels. Available SiO2 was highest in RHNF, while PRC-treated plots showed lower values. Exchangeable Ca2+ and Mg2+ were significantly enhanced by PRC application, particularly in RHPRC.

In WSG-7, soil pH ranged from 4.54 to 4.74. OM content increased markedly with both PRC and RH treatments, reaching its highest value in RHPRC. Available P2O5 was highest in NMPRC, whereas RH-treated plots exhibited lower values. Exchangeable Ca2+ and Mg2+ increased substantially with PRC application, with Ca2+ in RHPRC showing a nearly 1.5-fold increase compared with NMNF. In contrast, K+ and Na+ showed relatively minor variations among treatments.

4. Discussion

4.1. Seed Germination and Seedling Vigor Index (SVI) in Wild-Simulated Ginseng

Seed germination and SVI are critical indicators of early establishment success, particularly in perennial medicinal crops cultivated under forest conditions. In the present study, overall germination rates of WSG were relatively low across treatments, which is consistent with previous reports indicating that WSG seeds generally exhibit poor germination under natural forest environments. Yong et al. [59] reported germination rates of approximately 15% under leaf-covered forest conditions, while Kim et al. [60] observed germination rates below 50% even under managed conditions. These findings suggest that low germination is an inherent constraint in WSG cultivation.

Nevertheless, germination rate and SVI were markedly higher in the RHPRC treatment than in the non-mulched, non-amended control (NMNF). This improvement is likely attributable to the combined effects of RH mulching and PRC application on the soil microenvironment. Organic mulching materials such as RH are known to reduce soil moisture evaporation, buffer soil temperature fluctuations, and protect seeds from excessive radiation, thereby creating more favorable conditions for germination [60,61,62]. In contrast, the lowest germination observed in NMNF likely reflects unfavorable surface conditions, including rapid moisture loss and unstable temperature regimes.

SVI integrates germination percentage with early seedling growth and has been widely used as a predictor of subsequent plant performance [63,64]. In this study, treatments associated with higher SVI at the seedling stage also exhibited improved growth characteristics in 7-year-old plants, suggesting that early establishment conditions may influence long-term performance in WSG. Given the extended cultivation period of WSG (7–12 years) [65], environmentally benign strategies that improve early-stage soil conditions—such as mineral–organic soil amendments—may represent a practical alternative to chemical seed treatments, which can raise concerns regarding environmental safety and regulatory compliance.

4.2. Effects of PRC and RH on Growth Characteristics

Growth responses of WSG differed depending on cultivation age and soil amendment treatment. Rice husk and processed red clay exerted distinct effects, while their combined application (RHPRC) produced more consistent improvements across multiple growth parameters. In general, RH application alone tended to increase biomass accumulation, particularly root fresh weight, without markedly increasing shoot or root length. This pattern suggests that RH primarily influences soil physical properties, such as moisture retention and aeration, which may favor biomass accumulation rather than elongation growth.

In contrast, PRC application was more strongly associated with enhanced root development, especially at the early cultivation stage (WSG-1). In WSG-1 plants, PRC-treated soils were associated with increased root length and fresh weight, indicating a potential role of mineral-based amendments in promoting early root establishment. These observations are consistent with previous studies reporting that mineral-rich soil amendments can influence root growth by modifying nutrient availability and soil structure [22]. Clear age-dependent growth patterns were observed between WSG-1 and WSG-7. In WSG-7, increases in shoot fresh weight were more pronounced than increases in shoot length, reflecting a developmental transition from elongation-dominated growth to biomass accumulation. Root diameter and fine root development were also substantially greater in WSG-7, consistent with previous reports that ginseng shifts toward root thickening and storage organ development after several years of growth [66,67].

The combined RHPRC treatment consistently resulted in greater root diameter, fresh weight, and fine root number, particularly in WSG-7. Fine roots play a critical role in nutrient and water uptake and have been reported to contain relatively high concentrations of ginsenosides [68]. Although this study did not directly assess functional root activity, the increased fine root development observed under RHPRC treatment may partially contribute to improved nutrient acquisition and secondary metabolite accumulation over long-term cultivation.

4.3. Photosynthetic Pigment Responses

Photosynthetic pigment composition in WSG leaves varied with both cultivation age and soil amendment treatment. PRC application did not result in a consistent increase in total chlorophyll content in either WSG-1 or WSG-7. In WSG-1, total chlorophyll content did not differ significantly between NMPRC and NMNF treatments, while a slight reduction was observed under RHPRC treatment. These results indicate that PRC and RH do not directly enhance chlorophyll accumulation. However, carotenoid content was significantly higher in PRC-treated WSG-1 plants. Carotenoids play essential roles in photoprotection by dissipating excess excitation energy and mitigating oxidative stress [69,70,71].

Therefore, increased carotenoid accumulation may reflect improved physiological stability under forest-shaded conditions rather than enhanced photosynthetic capacity per se. Previous studies have similarly reported that silicon-based soil amendments do not necessarily increase chlorophyll content in ginseng but may influence pigment balance and stress tolerance [72]. Consistent with these findings, PRC application in the present study did not result in a marked increase in total chlorophyll content. However, the observed increase in carotenoid content under NMPRC treatment suggests that PRC may improve physiological conditions related to photoprotection and photosynthetic stability rather than directly promoting chlorophyll accumulation.

The chlorophyll a/b ratios observed in this study (1.32–1.86) are characteristic of shade-adapted plants, in which increased chlorophyll b content enhances light-harvesting efficiency under low irradiance [73]. PRC-treated plants tended to exhibit relatively higher chlorophyll a/b ratios, suggesting subtle alterations in pigment composition. However, because photosynthetic activity was not directly measured, the functional implications of these pigment changes should be interpreted with caution.

4.4. Total Polyphenol Content

Total polyphenol content exhibited pronounced age-dependent responses to soil amendment treatments. In WSG-1, increases in root total polyphenol content were primarily observed in RH-containing treatments (RHNF and RHPRC), whereas PRC alone had limited effects. In contrast, in WSG-7, root total polyphenol content was significantly higher across all amended treatments, indicating that long-term soil management plays an important role in polyphenol accumulation.

RH contains silica and organic functional groups that may influence soil–plant interactions and the stability of phenolic compounds [74]. In addition, previous studies have reported that silicon-based amendments can be associated with enhanced secondary metabolite production under certain conditions [75,76,77]. While the present study does not provide direct evidence of underlying biochemical mechanisms, the observed increases in total polyphenol content suggest that combined mineral–organic soil amendments may contribute to a soil environment conducive to polyphenol accumulation during long-term WSG cultivation.

Polyphenol distribution patterns observed in this study—higher concentrations in shoots during early growth stages—are consistent with previous reports in ginseng and other medicinal plants [78,79,80]. Because only total polyphenol content was assessed, further studies focusing on specific phenolic compounds and associated metabolic pathways are required to clarify regulatory mechanisms.

4.5. Ginsenoside Contents

Ginsenosides are the primary bioactive constituents of ginseng and serve as key indicators of medicinal quality [81,82]. In this study, ginsenoside accumulation increased markedly with cultivation age, with WSG-7 plants exhibiting substantially higher levels than WSG-1, consistent with established knowledge that ginsenoside content increases over time [83,84]. Soil amendment treatments influenced ginsenoside profiles, although effects varied by compound and cultivation stage [85,86,87]. In WSG-1, Rg1 was more abundant in shoots, whereas Rb1 predominated in roots, reflecting known tissue-specific distribution patterns [88,89,90]. In WSG-7, PRC-treated plots tended to show higher levels of PPD-type ginsenosides, including Rb1 and Rb2. These differences may reflect indirect effects of improved soil conditions on metabolic regulation rather than direct stimulation of ginsenoside biosynthesis.

Recent studies suggest that ginsenoside accumulation is regulated by coordinated metabolic networks rather than single biosynthetic steps [84,86,91,92]. Therefore, improvements in soil chemical properties and root system development associated with PRC and RH application may contribute to a physiological environment favorable for secondary metabolite accumulation over long-term cultivation

4.6. Effects of PRC and RH on Soil Chemical Properties

PRC and RH exerted complementary effects on soil chemical properties. RH application significantly increased soil organic matter content, particularly in WSG-1 soils, consistent with enhanced carbon input and microbial activity [93,94,95]. However, RH alone tended to reduce available P2O5, suggesting potential phosphorus immobilization during organic matter decomposition. In contrast, PRC application increased available P2O5, as well as exchangeable Ca2+ and Mg2+, likely by mobilizing previously fixed nutrients [96]. The combined RHPRC treatment resulted in more stable and balanced improvements across soil parameters, particularly in long-term cultivated soils (WSG-7). These findings indicate that integrated mineral–organic soil amendment strategies may be more effective than single amendments for sustaining soil fertility and supporting long-term WSG cultivation under forest conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the effects of PRC and RH amendments on the growth, phytochemical characteristics, and soil properties of WSG cultivated under forest conditions. A clear difference in plant survival and growth was observed between early-stage (WSG-1) and long-term cultivated plants (WSG-7), underscoring the inherent difficulty of maintaining WSG over extended cultivation periods and highlighting the importance of appropriate soil management during the early establishment stage.

Across treatments, the combined application of RH and PRC (RHPRC) was consistently associated with higher germination rates, improved seedling vigor, and enhanced biomass accumulation compared with the non-mulched, non-amended control. PRC application was also associated with measurable changes in soil chemical properties, including increased exchangeable Ca2+ and Mg2+ and improved indicators of soil fertility, particularly in long-term cultivated soils. These changes occurred without the application of synthetic fertilizers, suggesting that mineral–organic soil amendments may contribute to improved soil nutrient balance under forest cultivation conditions. Phytochemical analyses indicated that total polyphenol and ginsenoside contents increased markedly with cultivation age, and that amended treatments—particularly those including PRC—were associated with higher accumulation of specific secondary metabolites in mature plants. However, the effects of PRC and RH varied depending on cultivation stage and compound type, indicating that their influence on phytochemical accumulation is likely indirect and mediated through long-term improvements in soil conditions and root development rather than through direct stimulation of biosynthetic pathways.

Overall, the findings of this study suggest that PRC- and RH-based soil management practices have potential as environmentally benign strategies to support sustainable WSG cultivation by improving soil properties and supporting plant growth and phytochemical accumulation under forest conditions. Further studies are required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of PRC–plant–soil interactions, including the roles of PRC-derived minerals such as silicon, and to validate the long-term applicability of these amendments across different forest environments.

Author Contributions

Research design, H.K. and H.W.L.; performing experiments, S.L. (Sora Lee) and W.C.; data analysis, S.L. (Sora Lee), M.J., A.S. and H.J.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L. (Sora Lee); writing—review and editing, H.C., S.L. (Songhee Lee) and H.K.; supervision, H.W.L. and H.K.; funding acquisition, D.S.K. and H.W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Forest Science (grant number FP0802-2023-02), Korea.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Moonyoung Yoon for supplying the PRC to perform this experiment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NF | Non-Fertilizer |

| NM | Non-Mulching |

| PRC | Processed Red Clay |

| RH | Rice Husk |

| SVI | Seedling Vigor Index |

| WSG | Wild-Simulated Ginseng |

References

- Streimikis, J.; Baležentis, T. Agricultural sustainability assessment framework integrating sustainable development goals and interlinked priorities of environmental, climate and agriculture policies. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1702–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. REPowerEU Plan: Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. Available online: https://cdn.climatepolicyradar.org/navigator/EUR/2022/european-commission-communication-repowereu-plan_e664152c06f10794af4cc41112ec4a2c.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2019; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Pretty, J.; Benton, T.G.; Bharucha, Z.P.; Dicks, L.V.; Flora, C.B.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Goulson, D.; Hartley, S.; Lampkin, N.; Morris, C. Global assessment of agricultural system redesign for sustainable intensification. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, P.C.; Gerber, J.S.; Engstrom, P.M.; Mueller, N.D.; Brauman, K.A.; Carlson, K.M.; Cassidy, E.S.; Johnston, M.; MacDonald, G.K.; Ray, D.K. Leverage points for improving global food security and the environment. Science 2014, 345, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur Rahim, H.; Qaswar, M.; Uddin, M.; Giannini, C.; Herrera, M.L.; Rea, G. Nano-enable materials promoting sustainability and resilience in modern agriculture. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diacono, M.; Montemurro, F. Long-term Effects of Organic Amendments on Soil Fertility. In Sustainable Agriculture; Lichtfouse, E., Hamelin, M., Navarrete, M., Debaeke, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 761–786. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S.; Hu, Q.; Liu, Q.; Xu, W.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, W.; Dong, W. The Synergistic effect of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and spent mushroom substrate improves ginseng quality and rhizosphere nutrients. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, M.A.; Flinn, K.M.; Jancaitis, J.; Alley, A.; Paxton, A. Declining abundance of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.) documented by herbarium specimens. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 134, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, K. Crafting the wild: Growing ginseng in the simulated wild in Appalachia. Agric. Hum. Values 2024, 41, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, K.; Um, Y.; Jung, C.; Park, H.; Kim, M. Standard Cultivation Manual of Wild-Simulated Ginseng; National Institute of Forest Science: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2018; pp. 15–20.

- Kim, K.; Huh, J.H.; Um, Y.; Jeon, K.S.; Kim, H.J. The comparative of growth characteristics and ginsenoside contents in wild-simulated ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) on different years by soil properties of cultivation regions. Korean J. Plant Resour. 2020, 33, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Yun, Y.B.; Park, M.; Um, Y. Correlation between soil properties and growth of wild-simulated ginseng for site suitability assessment. Korean J. Soil Sci. Fertil. 2025, 58, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilkes, R.J.; Prakongkep, N. How the unique properties of soil kaolin affect the fertility of tropical soils. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 131, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjaiah, K.M.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Paul, R.; Datta, S.C.; Kumararaja, P.; Sarkar, B. Clay minerals and zeolites for environmentally sustainable agriculture. In Modified Clay and Zeolite Nanocomposite Materials; Mariano, M., Binoy, S., Alessio, L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 309–329. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, K.; Fenton, C.H.; Bell, D.H. A review of the geotechnical characteristics of loess and loess-derived soils from Canterbury, South Island, New Zealand. Eng. Geol. 2018, 236, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wi, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, S. Biochar-red clay composites for energy efficiency as eco-friendly building materials: Thermal and mechanical performance. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 373, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J. Mineralogy and chemical composition of the kesiaual soils (Hwangto) from South Korea. Miner. Soc. Korea 2000, 13, 147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Han, G.Z.; Zhang, G.-L.; Li, D.C.; Yang, J.L. Pedogenetic evolution of clay minerals and agricultural implications in three paddy soil chronosequences of South China derived from different parent materials. J. Soils Sediments 2015, 15, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, S.; Marschner, P. Clay addition to sandy soil: Effect of clay concentration and ped size on microbial biomass and nutrient dynamics after addition of low C/N ratio residue. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2016, 16, 864–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Yoon, T.K.; Han, S.; Kang, H.; Yi, M.; Son, Y. Effects of soil amendments on survival rate and growth of Populus sibirica and Ulmus pumila seedlings in a semi-arid region, Mongolia. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2014, 103, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.; Yang, I.; Yoon, S.; Kim, S.; Seo, S.; Won, C.I.; Cho, W.; Lee, S.; Kang, H.; Yoon, M.Y. Evaluation of quality characteristics of Brassica campetris L. Treated with environmentally-friendly red clay-processed materials. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 44, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.W.; Jang, H.; Cho, W.; Tsetsegmaa, G.; Kang, H.; Choi, H. Effects of processed red-clay and microbial fertilizer containing Lactobacillus fermentum on tomato growth characteristics, and fruit quality levels. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2024, 42, 414–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jang, H.; Lee, S.; Cho, W.; Lee, H.W.; Kang, H.; Choi, H. Effects of processed red clay and microbial fertilizer containing Lactobacillus fermentum on cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) growth and soil properties. J. Agric. Life Sci. 2024, 58, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, T.; Sindhu, S.S. Sustainable management of organic agricultural wastes: Contributions to nutrient availability, pollution mitigation, and crop production. Discov. Agric. 2024, 2, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Dhada, I.; Haldar, P. Rice Husk: From Agro-Industrial to Modern Applications. In Agricultural Waste to Value-Added Products: Technical, Economic and Sustainable Aspects; Neelancherry, R., Gao, B., Wisniewski, A., Jr., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 295–320. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, N.N.; Nguyen, A.V.; Konarova, M. Converting rice husk biomass into value-added materials for low-carbon economies: Current progress and prospect toward more sustainable practices. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linam, F.; Limmer, M.A.; Ebling, A.M.; Seyfferth, A.L. Rice husk and husk biochar soil amendments store soil carbon while water management controls dissolved organic matter chemistry in well-weathered soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 339, 117936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Taing, K.; Hall, M.W.; Shinogi, Y. Effects of rice husk and rice husk charcoal on soil physicochemical properties, rice growth and yield. Agric. Sci. 2017, 8, 1014–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Amirahmadi, E. Effect of rice husk biochar (RHB) on some of chemical properties of an acidic soil and the absorption of some nutrients. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2018, 22, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsuri, A.W.; Tariq, F.S.; Karam, D.S.; Aris, A.Z.; Jamilu, G. The effects of rice husk ashes and inorganic fertilizers application rates on the phytoremediation of gold mine tailings by vetiver grass. Appl. Geochem. 2019, 108, 104366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Lee, C.K.; Kang, H.M.; Choi, S.I.; Jeon, S.H.; Kim, H. Land suitability evaluation for wild-simulated ginseng cultivation in South Korea. Land 2021, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, D.; Yang, J.; Jiao, X.; Gao, W. Effect of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium deficiency on content of phenolic compounds in exudation of American ginseng. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2011, 36, 326–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheban, K.C.; Woodbury, D.J.; Duguid, M.C. Importance of environmental factors on plantings of wild-simulated American Ginseng. Agrofor. Syst. 2022, 96, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Niu, Y.Q.; Wang, X.F.; Wang, Z.H.; Yang, M.L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.G.; Song, W.J.; Li, Z.P.; Lin, F. Phenotypic and transcriptomic responses of the shade-grown species Panax ginseng to variable light conditions. Ann. Bot. 2022, 130, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Jang, M.; Choi, J.; Chang, B.S.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, Y.; Kwak, Y.S.; Oh, S.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Korean red ginseng and ginsenoside-Rb1/-Rg1 alleviate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by suppressing Th1 and Th17 cells and upregulating regulatory T cells. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 1977–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, X.; He, M.; Zheng, W.; Qi, D.; Zhang, Y.; Han, C. Ginseng polysaccharides: A potential neuroprotective agent. J. Ginseng Res. 2021, 45, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.H.; Kim, H.G.; Jang, K.; Kim, Y.J. Novel cultivation of six-year-old Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng) in pot: From non-agrochemical management to increased ginsenoside. J. Ginseng Res. 2024, 48, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, M.Y.; Lee, S.; Choo, J.H.; Jang, H.; Cho, W.; Kang, H.; Park, J.K. Economical synthesis of complex silicon fertilizer by unique technology using loess. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 33, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Soil Information System. Available online: https://soil.rda.go.kr/geoweb/soilmain.do (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Korea Meteorological Administration. Available online: https://web.kma.go.kr (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Abdul-Baki, A.A.; Anderson, J.D. Vigor Determination in soybean seed by multiple criteria. Crop Sci. 1973, 13, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinney, G. Absorption of light by chlorophyll solutions. J. Biol. Chem. 1941, 140, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnon, D.I. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Mistry, H.; Thakor, R.; Bariya, H. Isolation and identification of associative symbiotic N2 fixing microbes: Desulfovibrio. In Practical Handbook on Agricultural Microbiology; Amaresan, N., Patel, P., Amin, D., Eds.; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tyurin, I. A new modification of the volumetric method of determining soil organic matter by means of chromic acid. Pochvovedenie 1931, 26, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, P.L. Kjeldahl method for total nitrogen. Anal. Chem. 1950, 22, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alban, L.; Vacharotayan, S.; Jackson, T. Phosphorus availability in reddish brown lateritic soils. I. Laboratory studies 1. Agron. J. 1964, 56, 555–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.A. Reflectance wavebands and indices for remote estimation of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance in pine canopies. Remote Sens. Environ. 1998, 63, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.A.; Cibula, W.G.; Miller, R.L. Narrow-band reflectance imagery compared with thermal imagery for early detection of plant stress. J. Plant Physiol. 1996, 148, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, N.; Hou, J.; Xu, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X. Factors influencing leaf chlorophyll content in natural forests at the biome scale. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.P. Ginsenosides: Chemistry, biosynthesis, analysis, and potential health effects. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2008, 55, 1–99. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.D. Metabolism and drug interactions of Korean ginseng based on the pharmacokinetic properties of ginsenosides: Current status and future perspectives. J. Ginseng Res. 2024, 48, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Kim, M.; Rhee, M.H. Anti-platelet role of Korean ginseng and ginsenosides in cardiovascular diseases. J. Ginseng Res. 2020, 44, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiani, M.H.; Eassa, S.; Parnell, C.; Nima, Z.; Ghosh, A.; Biris, A.S.; Khodakovskaya, M.V. Carbon nanotubes as carriers of Panax ginseng metabolites and enhancers of ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg1 anti-cancer activity. Nanotechnology 2016, 28, 015101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.H. Effects of Panax ginseng in neurodegenerative diseases. J. Ginseng Res. 2012, 36, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, S.H.; Seo, Y.R.; Kim, H.G.; Park, D.; Seol, Y.; Choi, E.; Hong, J.H.; Choi, M.S. Growth characteristics and saponin content of mountain-cultivated ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) according to seed-sowing method suitable for cultivation under forest. For. Sci. Technol. 2020, 16, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Um, Y.; Jeong, D.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, M.J.; Jeon, K.S. The correlation between growth characteristics and location environment of wild-simulated ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer). Korean J. Plant Resour. 2019, 32, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G.; Ku, J.J.; Cho, W.; Kang, H. Effects of rice hull cover for seed germination, types of tray and soil, shading conditions for seedling growth of Codonopsis pilosuala. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2013, 102, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.K.; Moon, K.G.; Kim, S.U.; Um, I.S.; Cho, Y.S.; Kim, Y.G.; Rho, I.R. Analysis of growth and antioxidant compounds in deodeok in response to mulching materials. Korean J. Med. Crop Sci. 2016, 24, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Salokhe, V. Seedling characteristics and the early growth of transplanted rice under different water regimes. Exp. Agric. 2008, 44, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G.; Kim, H.Y.; Ku, J.J. Effects of seed storage temperature and pre-treatment on germination, seedling quality on wild Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim and Trichosanthes kirilowii var. japonica Kitam. Korean J. Med. Crop Sci. 2014, 22, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.B.; McGraw, J.B. Can putative indicator species predict habitat quality for American ginseng? Ecol. Indic. 2015, 57, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, B.G.; Jung, G.R.; Kim, M.S.; Moon, H.G.; Park, S.J.; Chun, J. Ginsenoside contents and antioxidant activities of cultivated mountain ginseng (Panax ginseng CA Meyer) with different ages. Food Sci. Preserv. 2019, 26, 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G.; Choi, G.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Yun, S.J.; Kim, W.; Lee, H.; Baik, M.Y.; Hwang, J.K. Proximate analysis and antioxidant activity of cultivated wild Panax ginseng. Food Eng. Prog. 2017, 21, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.S.; Tak, H.S.; Lee, G.S.; Kim, J.S.; Choi, J.E. Comparison of ginsenoside content according to age and diameter in Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer cultivated by direct seeding. Korean J. Med. Crop Sci. 2013, 21, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, K.H. Effects of acid treatments on chlorophyll, carotenoid and anthocyanin contents in Arabidopsis. Res. Plant Dis. 2010, 16, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, R.D.; Prihastyanti, M.N.U.; Lukitasari, D.M. Effects of pH, high pressure processing, and ultraviolet light on carotenoids, chlorophylls, and anthocyanins of fresh fruit and vegetable juices. eFood 2021, 2, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, G.A.; Hearst, J.E. Genetics and molecular biology of carotenoid pigment biosynthesis. FASEB J. 1996, 10, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Sadiq, N.B.; Hamayun, M.; Jung, J.; Lee, T.; Yang, J.S.; Lee, B.; Kim, H.Y. Silicon foliage spraying improves growth characteristics, morphological traits, and root quality of Panax ginseng C.A. Mey. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 156, 112848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.; Walters, R.G.; Jansson, S.; Horton, P. Acclimation of Arabidopsis thaliana to the light environment: The existence of separate low light and high light responses. Planta 2001, 213, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapolova, E.G.; Lomovskij, O.I. Features of the mechanical treatment of rice husk for the performance of the solid-phase reaction of silicon dioxide with polyphenols. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2016, 42, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanchal Malhotra, C.; Kapoor, R.; Ganjewala, D. Alleviation of abiotic and biotic stresses in plants by silicon supplementation. Sci. Agric. 2016, 13, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Zhu, X.; Chen, K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C. Silicon alleviates oxidative damage of wheat plants in pots under drought. Plant Sci. 2005, 169, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, F.A.; Tahir, I.; Hakeem, K.R.; Rehman, R.U. Silicon application enhances the photosynthetic pigments and phenolic/flavonoid content by modulating the phenylpropanoid pathway in common buckwheat under aluminium stress. Silicon 2022, 14, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Evaluation of antioxidant activity and thermal stability of plant polyphenols. Biomater. Res. 2009, 13, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.S. Investigation of phenolic, flavonoid, and vitamin contents in different parts of Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng CA Meyer). Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2016, 21, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, I.M.; Lim, J.J.; Ahn, M.S.; Jeong, H.N.; An, T.J.; Kim, S.H. Comparative phenolic compound profiles and antioxidative activity of the fruit, leaves, and roots of Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng Meyer) according to cultivation years. J. Ginseng Res. 2016, 40, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.O.; Shin, Y.S.; Hyun, S.H.; Cho, S.; Bang, K.H.; Lee, D.; Choi, S.P.; Choi, H.K. NMR-based metabolic profiling and differentiation of ginseng roots according to cultivation ages. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2012, 58, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kong, D.; Fu, Y.; Sussman, M.R.; Wu, H. The effect of developmental and environmental factors on secondary metabolites in medicinal plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Ding, L. Investigation of ginsenosides in different parts and ages of Panax ginseng. Food Chem. 2007, 102, 664–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Wang, Q.; Pei, W.; Li, S.; Wang, T.; Song, H.; Teng, D.; Kang, T.; Zhang, H. Age-induced changes in ginsenoside accumulation and primary metabolic characteristics of Panax ginseng in transplantation mode. J. Ginseng Res. 2024, 48, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.Q.; Yi, L.W.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, Y.Z.; Guo, F.; Huo, Y.S.; Zhao, D.Q.; Xu, F.; Wang, X.; Cai, S.-Q. 177 Saponins, including 11 new compounds in wild ginseng tentatively identified via HPLC-IT-TOF-MSn, and differences among wild ginseng, ginseng under forest, and cultivated ginseng. Molecules 2021, 26, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.S.; Park, H.S.; Lee, D.K.; Jayakodi, M.; Kim, N.H.; Koo, H.J.; Lee, S.C.; Kim, Y.J.; Kwon, S.W.; Yang, T.J. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis of five Panax ginseng cultivars reveals the dynamics of ginsenoside biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Balan, P.; Popovich, D.G. Analysis of ginsenoside content (Panax ginseng) from different regions. Molecules 2019, 24, 3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Shen, L.; Zhang, J. Anti-amnestic and anti-aging effects of ginsenoside Rg1 and Rb1 and its mechanism of action. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2005, 26, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Joo, S.C.; Shi, J.; Hu, C.; Quan, S.; Hu, J.; Sukweenadhi, J.; Mohanan, P.; Yang, D.C.; Zhang, D. Metabolic dynamics and physiological adaptation of Panax ginseng during development. Plant Cell Rep. 2018, 37, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, O.J.; Kim, J.S. Comparison of ginsenoside contents in different parts of Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer). Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2016, 21, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, L.; Qi, L.; Lu, X. Construct a gene-to-metabolite network to screen the key genes of triterpene saponin biosynthetic pathway in Panax notoginseng. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2018, 65, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Transcriptional regulatory network of ginsenosides content in various ginseng cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 322, 112388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillman, G.P.; Burkett, D.C.; Coventry, R.J. Amending highly weathered soils with finely ground basalt rock. Appl. Geochem. 2002, 17, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.F.; Miyake, Y.; Takahashi, E. Silicon as a beneficial element for crop plants. Stud. Plant Sci. 2001, 8, 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yanai, J.; Taniguchi, H.; Nakao, A. Evaluation of available silicon content and its determining factors of agricultural soils in Japan. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2016, 62, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, J.; Faucherre, S.; Joss, H.; Obst, M.; Goeckede, M.; Planer-Friedrich, B.; Peiffer, S.; Gilfedder, B.; Elberling, B. Silicon increases the phosphorus availability of Arctic soils. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.