Abstract

Tea bud recognition and localization constitute a fundamental step toward enabling fine-grained tea plantation management and intelligent harvesting, offering substantial value in improving the picking quality of premium tea materials, reducing labor dependency, and accelerating the development of smart tea agriculture. However, most existing methods for detecting tea buds are built upon Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) and rely extensively on floating-point computation, making them difficult to deploy efficiently on energy-constrained edge platforms. To address this challenge, this paper proposes an energy-efficient tea bud detection model, GAE-SpikeYOLO, which improves upon the Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) detection framework SpikeYOLO. Firstly, Gated Attention Coding (GAC) is introduced into the input encoding stage to generate spike streams with richer spatiotemporal dynamics, strengthening shallow feature saliency while suppressing redundant background spikes. Secondly, the model incorporates the Temporal-Channel-Spatial Attention (TCSA) module into the neck network to enhance deep semantic attention on tea bud regions and effectively suppress high-level feature responses unrelated to the target. Lastly, the proposed model adopts the EIoU loss function to further improve bounding box regression accuracy. The detection capability of the model is systematically validated on a tea bud object detection dataset collected in natural tea garden environments. Experimental results show that the proposed GAE-SpikeYOLO achieves a Precision (P) of 83.0%, a Recall (R) of 72.1%, a mAP@0.5 of 81.0%, and a mAP@[0.5:0.95] of 60.4%, with an inference energy consumption of only 49.4 mJ. Compared with the original SpikeYOLO, the proposed model improves P, R, mAP@0.5, and mAP@[0.5:0.95] by 1.4%, 1.6%, 2.0%, and 3.3%, respectively, while achieving a relative reduction of 24.3% in inference energy consumption. The results indicate that GAE-SpikeYOLO provides an efficient and readily deployable solution for tea bud detection and other agricultural vision tasks in energy-limited scenarios.

1. Introduction

Tea has become one of the most popular beverages worldwide due to its unique flavor and high nutritional value. According to statistics from 2020, worldwide tea output amounted to 62,690 tons, among which China contributed the largest share, reaching 29,860 tons [1,2]. With the ongoing consumption upgrade and industrial modernization, there is an increasing demand for standardized raw material harvesting, bud integrity, and yield estimation in tea production. High-grade teas typically require the plucking of “one bud” or “one bud and one leaf” [3,4]. Therefore, accurate bud recognition, counting, and localization form the foundation for quality assurance and automated harvesting. In recent years, machine vision and intelligent harvesting have received growing attention in tea garden management and automated plucking. While traditional manual harvesting can maintain quality, it is labor-intensive, inefficient, and subject to seasonal labor shortages, which has driven research and application in mechanized and intelligent harvesting. Some recent studies have explored the integration of edge devices, such as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), with tea-target detection, moving toward an integrated “detection–localization–harvesting” workflow to enable both tea garden inspection and large-scale automated operations [5].

With the rapid advancement of computer vision and artificial intelligence, deep learning techniques have increasingly been applied to tackle various problems in agriculture. Leveraging these algorithms, tea-harvesting drones and robotic systems are able to detect and classify tea leaves more accurately, thereby enhancing both harvesting precision and operational efficiency [6,7]. Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks (R-CNN) [8] were among the first models introduced for object recognition. Subsequently, approaches such as You Only Look Once (YOLO) [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16], Single Shot MultiBox Detectors (SSD) [17], and other improved variants have been widely adopted in agricultural applications, achieving high accuracy and robustness in tasks including pest and disease detection, weed identification, and crop yield estimation. Sa et al. [18] proposed a fruit detection approach that integrates Faster R-CNN with multispectral imagery, achieving accurate apple detection in orchard environments. Bargoti and Underwood [19] employed Faster R-CNN to detect multiple types of fruits, including apples, mangoes, and oranges, demonstrating strong generalization performance under natural illumination variations and occlusion conditions. Wang et al. [20] introduced a blueberry maturity recognition method that combines an improved I-MSRCR image enhancement algorithm with a lightweight YOLO-BLBE model, effectively improving both recognition accuracy and detection efficiency for fruits at different maturity stages in complex natural environments. Xiao et al. [21] adopted a hybrid framework that integrates a Transformer model from the field of natural language processing with deep learning techniques to classify apples at different ripeness levels. This approach facilitates the fusion of multimodal data and offers greater flexibility in representation learning and modeling. Appe et al. [22] improved the YOLOv5 architecture by incorporating the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) for automatic multi-class tomato classification, achieving an average accuracy of 88.1%. However, compared to these agricultural tasks, tea bud detection presents more unique and complex challenges due to the small and densely distributed targets, as well as the high visual similarity between buds and surrounding leaves [23].

To address the unique challenges in tea bud detection, researchers have customized advanced object detection architectures and proposed various specialized models tailored for this task. Yang et al. [23] introduced the RFA-YOLOv8 model, which incorporates the Receptive Field Coordinate Attention Convolution (RFCAConv) module and an improved SPPFCSPC multi-scale feature extraction structure on the YOLOv8 framework. This model achieved 84.1% mAP@0.5 and 58.7% mAP@[0.5:0.95] on a self-constructed tea bud dataset. Yang et al. [24] proposed a tea bud recognition algorithm based on an improved YOLOv3, which optimizes the network architecture through an image pyramid mechanism, significantly enhancing detection accuracy and robustness under varying poses and occlusion conditions. Wang M et al. [25] introduced Tea-YOLOv5s, an enhanced YOLOv5s model incorporating ASPP for multi-scale feature extraction, BiFPN for efficient feature fusion, and CBAM for attention refinement. On the tea-shoots dataset, the model outperformed the original YOLOv5s, improving average precision and recall by 4.0 and 0.5 percentage points, respectively. Gui et al. [26] presented YOLO-Tea, which combines a multi-scale convolutional attention module (MCBAM), jointly optimizes anchor boxes using k-means clustering and a genetic algorithm, and employs EIoU loss with Soft-NMS, ultimately achieving 95.2% mean accuracy on the tea bud detection task. Chen et al. [27] proposed RT-DETR-Tea, which introduces cascaded grouped attention, the GD-Tea multi-scale fusion mechanism, and the DRBC3 module, attaining 96.1% accuracy and 79.7% mAP@[0.5:0.95] in multi-variety unstructured tea garden scenarios.

Although these deep learning models have demonstrated significant advantages in tea bud detection, their high computational demands and inference energy consumption hinder deployment on energy-constrained mobile devices. Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs), by simulating the spike-based signaling mechanism of biological neurons, perform computation and transmission only when information changes, thereby substantially reducing energy consumption and making them highly suitable for deployment on energy-limited edge devices or mobile platforms [28]. In recent years, several studies have explored the application of SNNs to object detection, achieving a certain balance between energy efficiency and performance. EMS-YOLO [29] was the first SNN model to perform object detection using a direct training strategy, employing surrogate gradient methods for end-to-end training. The SpikSSD model [30] further introduced a Spike-Based Feature Fusion Module (SBFM) to enhance the detection capability for multi-scale objects. SpikeYOLO [31] proposed a detection framework combining an integer-valued training strategy with spike-driven inference, achieving performance close to that of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs).

Improving the performance of Spiking Neural Networks in object detection while preserving their inherent energy efficiency has become a major challenge for practical SNN deployment. Researchers have attempted to develop more effective encoding schemes that convert static images into spatiotemporal feature sequences suitable for SNN inputs, aiming to improve network performance. Rate coding [32] (Van Rullen et al., 2001) represents pixel or feature intensity through spike firing frequency, where higher luminance corresponds to higher neuronal firing rates within a fixed time window. Temporal coding [33] (Comsa et al., 2020) conveys input strength or feature importance via spike timing rather than frequency, encoding information in the temporal position of spikes. Phase coding [34] (Kim et al., 2018) encodes input intensity using spike phase positions within a periodic reference signal (e.g., oscillatory waves). However, these encoding schemes fail to generate the intrinsic temporal dynamics observed in human vision, which serves as the fundamental inspiration for SNNs. The conventional LIF neuron remains the most classic spiking neuron model, mimicking membrane potential integration and leakage to achieve bio-inspired information processing. Nevertheless, the standard LIF model uses fixed parameters and has a limited dynamic range, making it difficult to accommodate multi-scale features and nonlinear temporal variations in complex visual tasks. To address this, researchers have proposed multiple enhanced neuron models, including PLIF neurons [35], I-LIF neurons [31], GLIF neurons [36], and others, which further optimize object detection performance in SNNs. Attention modules allow the network to concentrate on the most informative features while suppressing irrelevant or redundant responses. Moreover, integrating attention modules into SNN architectures can reduce spike firing rates triggered by non-target information, improving detection accuracy while lowering energy consumption. Yao et al. (2021) [37] attached the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) module [38] to the temporal input dimension of SNNs, but this method achieves improved performance only on small datasets using shallow networks. Yao et al. [39] transformed CBAM [40] into a multi-dimensional attention mechanism and injected it into SNN architectures, revealing the potential of deep SNNs as a general-purpose backbone for diverse applications. However, challenges remain when integrating attention modules into SNN architectures intended for deployment on neuromorphic hardware that supports sparse addition operations. This is because attention score computation typically requires partial multiplication units to dynamically generate attention weights, which may impede the spike-driven nature of SNNs.

Recently, the SpikeYOLO model proposed by Luo et al. [31] has achieved a major breakthrough in Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) for object detection, demonstrating the potential to surpass traditional Artificial Neural Network (ANNs) models in detection performance while preserving the inherent low-energy advantages of SNNs, thus presenting dual benefits in both performance and energy efficiency. Inspired by this, this paper takes SpikeYOLO as the base model and proposes an improved object detection method—GAE-SpikeYOLO, which aims to enable precise tea bud detection and recognition at low energy cost. Specifically, the proposed method integrates Gated Attention Coding (GAC) and the Temporal-Channel-Spatial Attention (TCSA) module to enhance the model’s detection capability for tea buds in complex environments. In addition, EIoU is employed as the bounding box regression loss to achieve faster convergence and more accurate bounding box localization. This method provides a new solution for deploying object detection algorithms on energy-constrained mobile devices and enabling high-precision tea bud detection.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- This paper presents the first study on the application of Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) to tea bud object detection.

- (2)

- This paper proposes an improved object detection model, namely GAE-SpikeYOLO, which integrates Gated Attention Coding, Temporal-Channel-Spatial Attention, and EIoU Loss into SpikeYOLO. The proposed model outperforms the original model on tea bud detection in complex environments, while achieving improvements in energy efficiency optimization, mAP@50, and mAP@[50:95].

- (3)

- The dataset used in this paper consists of 7842 tea bud images, covering diverse shooting perspectives and complex tea garden scenarios, enabling a comprehensive evaluation of the detection performance of GAE-SpikeYOLO under natural conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

Existing open-source tea bud datasets are constrained by single lighting or weather conditions and lack multi-view samples as well as complex cases involving occlusion and background interference [41,42], making it difficult for detection models to maintain generalization capability and robustness in real-world environments.

To address the limitations of current open-source datasets, this study adopts a tea bud image dataset collected from the experimental fields of the Yingde Tea Research Institute in Guangdong Province, during the period from 1 August 2025 to 11 September 2025. The dataset includes multiple tea bud varieties, such as Yinghong 9 and Hongyan 12, and was captured using a Canon EOS M200 (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan), an iPhone 13 Pro (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA), and a Huawei Mate 50 (Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). The dataset includes multiple acquisition perspectives, such as upward-, downward-, and front-facing views, and covers challenging tea garden scenarios, including leaf occlusion, backlighting, and strong illumination, allowing a more comprehensive restoration of detection difficulty in authentic tea garden environments.

A total of 7842 images are included in the dataset, with Table 1 presenting their distribution across different illumination intensities and acquisition angles. The data were split into training, validation, and testing sets at a 6:2:2 ratio, comprising 4706, 1568, and 1568 images, respectively. To ensure consistency within the dataset, images were preprocessed using the Python Imaging Library (Pillow, version 10.2.0). The LANCZOS resampling technique was employed to perform high-quality scaling, preserving overall image fidelity while processing RGBA-formatted images. To preserve sufficient spatial details for detecting small and densely distributed tea buds, all input images are resized to , as lower resolutions (e.g., ) would lead to excessive downsampling and loss of fine-grained features critical for accurate localization. In this study, “one bud” or “one bud and one leaf” morphology was adopted as the unified annotation criterion for tea bud recognition, and LabelImg (version 1.8.6) was used to manually annotate 7842 images to ensure the labeling quality of the dataset. The dataset contains diverse tea bud images across different lighting conditions, weather scenarios, perspectives, and natural occlusions, providing sufficient variation for training. Therefore, no additional data augmentation was applied. Representative sample images from the dataset are shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Image distribution across Luminous intensities and acquisition angles in the dataset.

Figure 1.

Some images from the dataset.

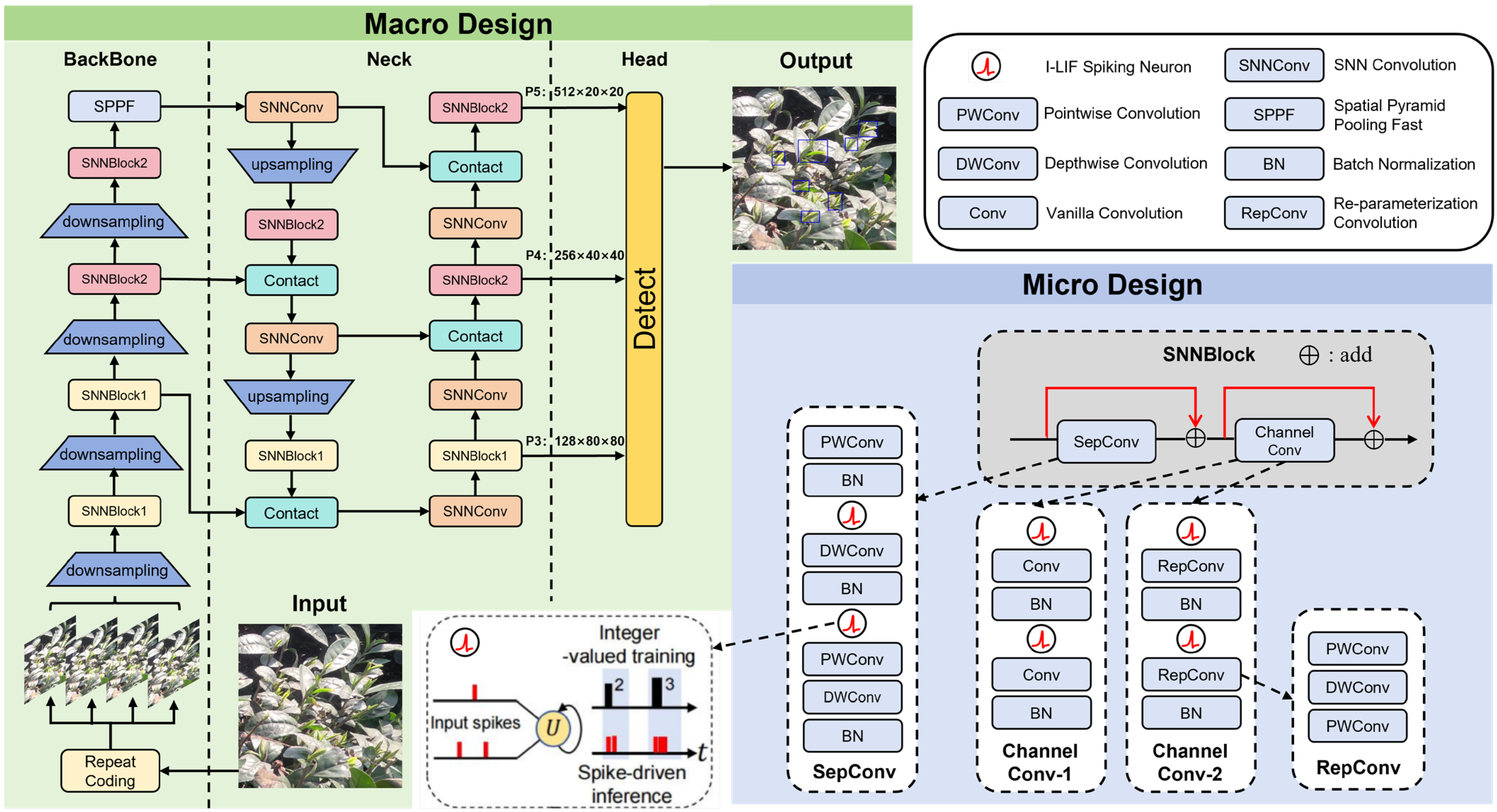

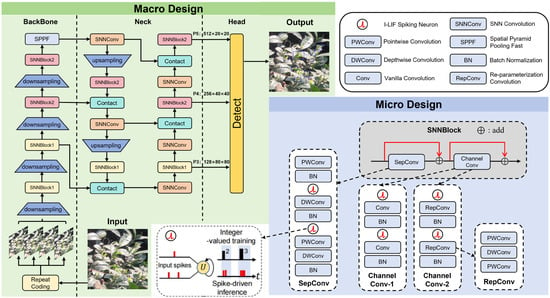

2.2. SpikeYOLO

Based on the macro framework of the YOLOv8 model, SpikeYOLO replaces the conventional continuous activation functions with a spiking mechanism that exhibits temporal dynamics. This substitution transforms a large number of energy-intensive multiply-accumulate (MAC) operations into energy-efficient accumulate (AC) operations, significantly reducing inference energy consumption and facilitating deployment on energy-constrained devices. The overall architecture of SpikeYOLO is illustrated in Figure 2. SpikeYOLO integrates the macro-level framework of YOLOv8 with the micro-level design of Meta-SpikeFormer [43], thereby avoiding spike degradation [44] that can occur when complex modules within the YOLO architecture are directly converted into their SNN counterparts.

Figure 2.

The architecture of SpikeYOLO. The blue boxes in the output of the figure indicate the detected tea bud targets.

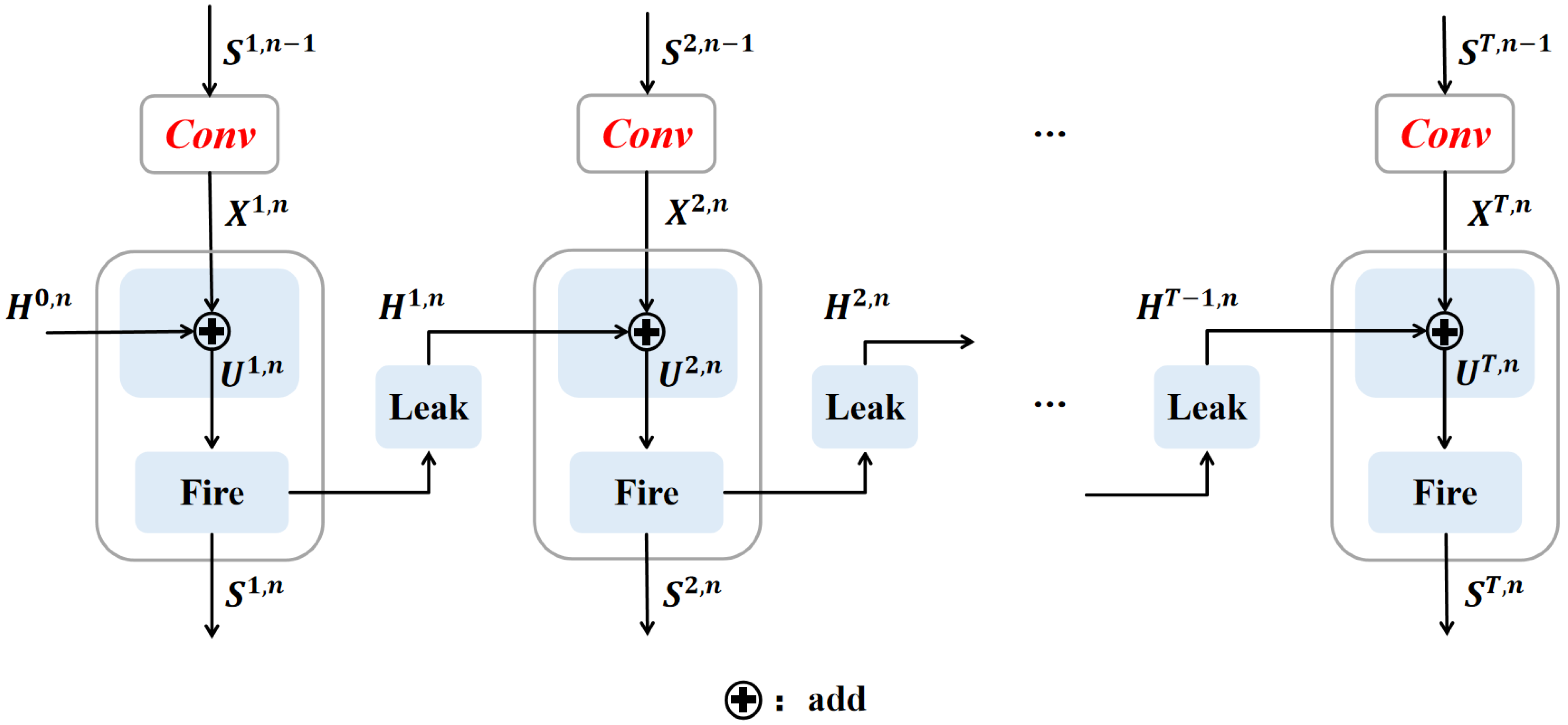

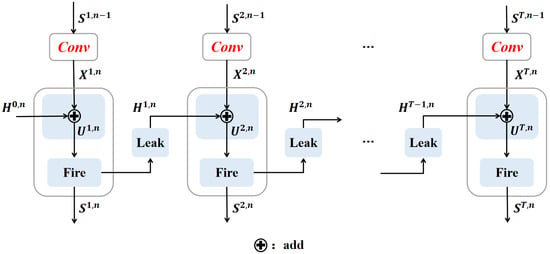

To further reduce quantization errors in the spiking network, SpikeYOLO designs an Integer Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (I-LIF) neuron. The mechanism of I-LIF is as follows:

Figure 3 provides a more detailed explanation of the working process of I-LIF, where denotes the time step, represents the membrane potential that integrates information from the previous time step and the current spatial information , and is the spike emitted at time . denotes the decay rate, represents the rounding operation, and denotes clipping to the range , where is the maximum integer output of the I-LIF neuron. I-LIF combines integer-valued training with spike-driven inference, which not only reduces network quantization errors during training but also preserves the sparse spiking characteristics of Spiking Neural Networks during inference.

Figure 3.

The flowchart of I-LIF.

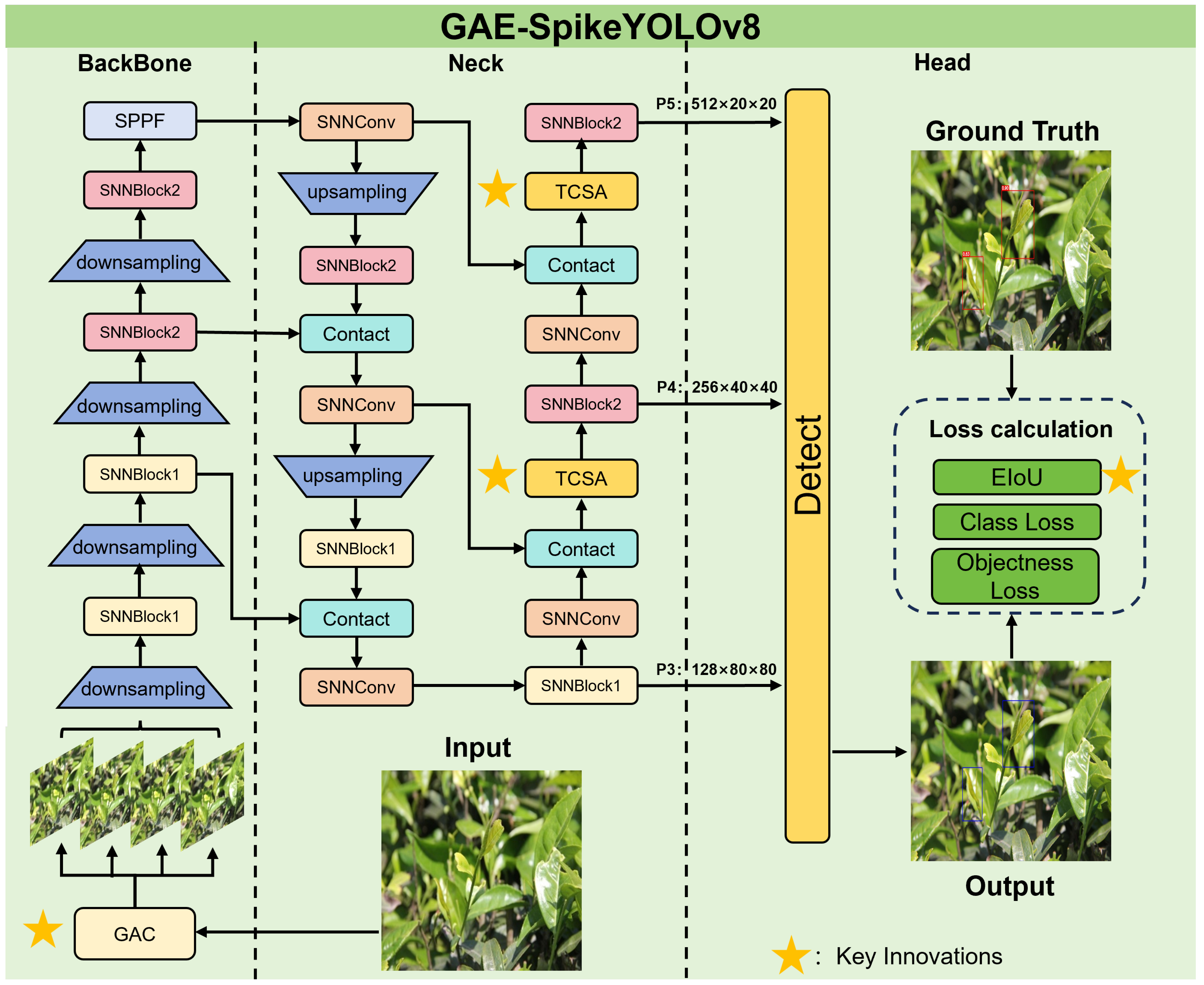

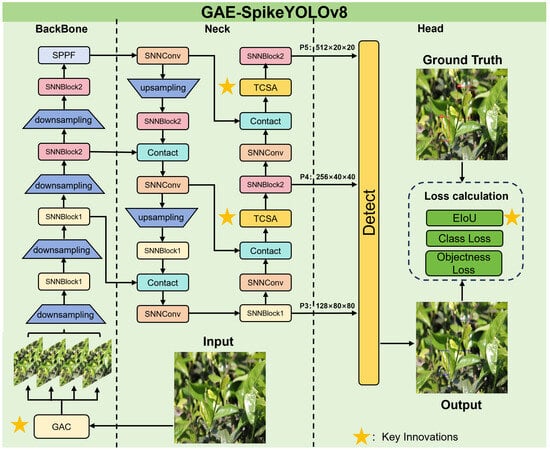

2.3. Architecture of the Proposed GAE-SpikeYOLO

The architecture of SpikeYOLO retains the efficient feature extraction and detection mechanisms of YOLOv8, while its spiking conversion introduces sparsity and event-driven characteristics in the computation process, providing significant energy efficiency advantages over the conventional YOLOv8. However, SpikeYOLO still has certain limitations that result in relatively poor detection accuracy in the task of tea bud detection. Specifically, at the input stage, static images are converted into spatiotemporal feature sequences suitable for Spiking Neural Network inputs using a simple repetition-based encoding. This encoding produces identical frames at each time step, leading to a lack of temporal dynamics and limiting the model’s ability to extract potential features across the temporal, spatial, and channel dimensions. As a result, shallow features such as local color, brightness, and texture variations are insufficiently captured, causing inaccurate localization and susceptibility to background noise. Moreover, the model lacks effective attention modeling for tea bud regions in deep semantic features. Such deficiencies reduces the model’s ability to focus on deep semantic regions, preventing global association and semantic verification across different parts of the target, which increases the likelihood of false positives and false negatives under complex backgrounds. To address these issues, this paper proposes an enhanced SpikeYOLO-based object detection model (as illustrated in Figure 4), which improves the detection performance of tea buds while reducing inference energy consumption. The improvements to the model architecture focus on three key aspects:

Figure 4.

The architecture of the proposed GAE-SpikeYOLO. Blue boxes in the output images indicate ground truth, and red boxes in the output images indicate model-detected targets.

- i.

- At the input stage, Gated Attention Coding (GAC) [44] is adopted as the spike encoding module. The module produces spike input sequences enriched with spatiotemporal information, markedly strengthening the temporal–spatial representation capability of the input features and guiding subsequent feature extraction layers toward more discriminative shallow semantic features. On one hand, it effectively suppresses noise interference and enhances target localization accuracy. On the other hand, it reduces spike firing in redundant background and noisy regions, thereby lowering the spike firing rate and further decreasing the model’s energy consumption.

- ii.

- After the fusion of two features along the bottom-up path in the neck network, a Temporal-Channel-Spatial Attention (TCSA) module [39] is introduced. This module adaptively adjusts feature responses across the temporal, channel, and spatial dimensions, focusing semantically on authentic tea bud regions and effectively suppressing high-level responses unrelated to the target, such as leaf tips or specular reflections. On one hand, it attenuates the membrane potentials of these non-target responses to enhance sparsity and further reduce energy consumption. On the other hand, it improves the model’s target recognition accuracy and robustness.

- iii.

- To address the issue of width-height gradient coupling in the CIoU-based bounding box regression loss of SpikeYOLO, this study adopts the EIoU bounding box loss [45] to replace the original CIoU loss. By decoupling the aspect ratio parameters, EIoU achieves faster convergence and more precise bounding box localization, thereby improving the model’s detection accuracy in complex scenarios.

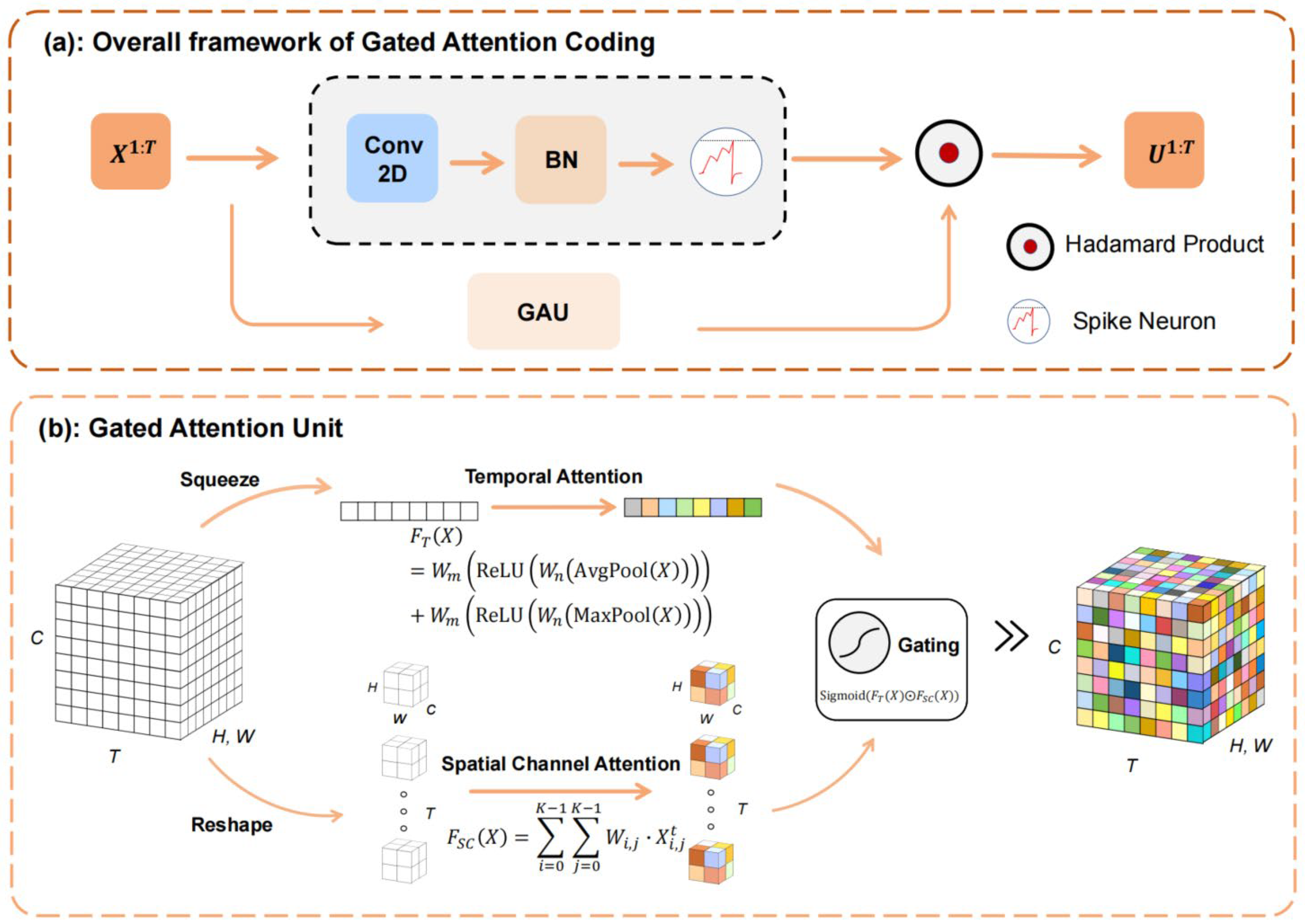

2.3.1. Gated Attention Coding (GAC)

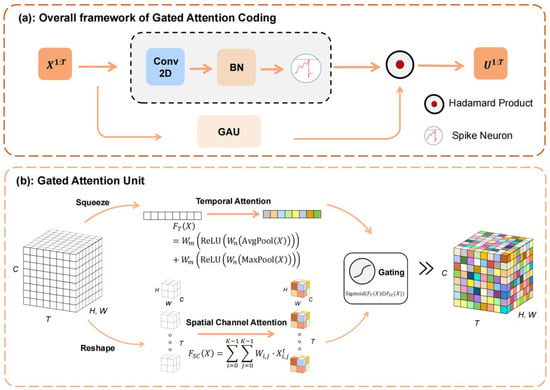

In this work, static input images are encoded using Gated Attention Coding (GAC). The overall architecture of GAC is illustrated in Figure 5a [44]. The complete GAC encoding procedure can be summarized as follows:

where and is the GAC module’s input and output, is a shared 2-D convoltion operation with the filter size of , and is the spiking neuron model. Moreover, is the Hadamard Product, and is the functional operation of GAU, which can fuse temporal-spatial-channel information for better encoding feature expression capabilities.

Figure 5.

The Gated Attention Coding (GAC) framework. (a) the overall framework of Gated Attention Coding, (b) the Gated Attention Unit.

As shown in Figure 5b, the Gated Attention Unit (GAU) consists of three units. In the following, we describe the working principles of each unit and their specific applications in this study.

The Temporal Attention unit first perform the squeezing step on the spatial-channel feature map of the repeated input , where is the input of GAC module, is the simulation time step and is the channel size. Then the unit use and to calculate the maximum and average of the input in the last three dimensions. Finally, the pooled features are jointly fed into a shared MLP network to produce a temporal attention weight vector , which can be formulated as follows:

where is the functional operation of temporal attention. And , are the weights of two shared dense layers. Moreover, is the temporal dimension reduction factor used to manage its computing overhead.

The Spatial Channel Attention unit use a shared 2-D convolution operation at each time step to obtain the spatial channel matrix . The computation process is presented as follows:

where is the functional operation of spatial channel attention, is the learnable parameter and represents the size of the 2-D convolution kernel size. And , where is the input of GAC module.

After the above two operations, the Gating unit obtain the temporal vector and spatial channel matrix . Then to extract the temporal-spatial-channel fused dynamics features, the unit first broadcast the temporal vector to and gating the above result by:

where and are the Sigmoid function and Hadamard Product.

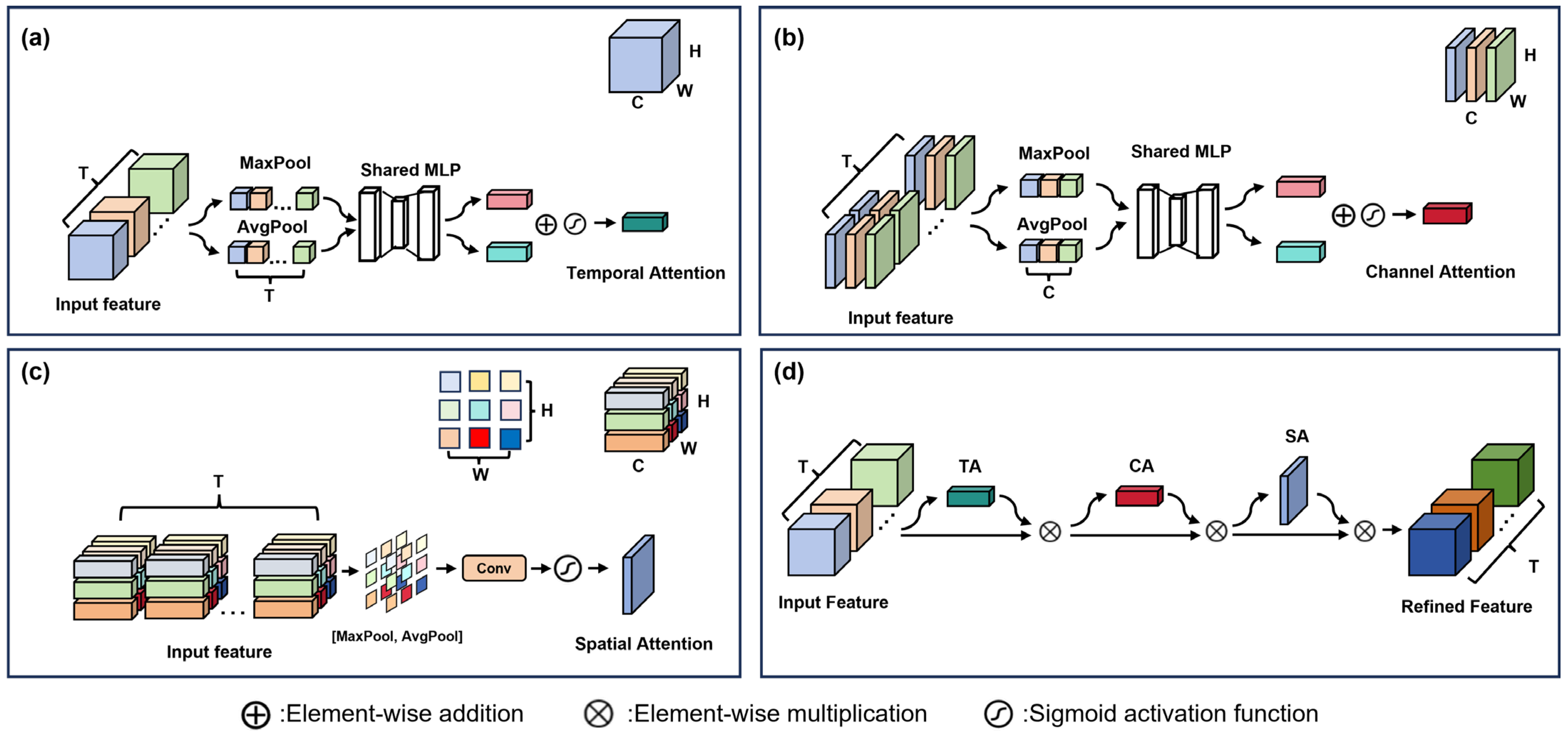

2.3.2. Temporal-Channel-Spatial Attention (TCSA) Module

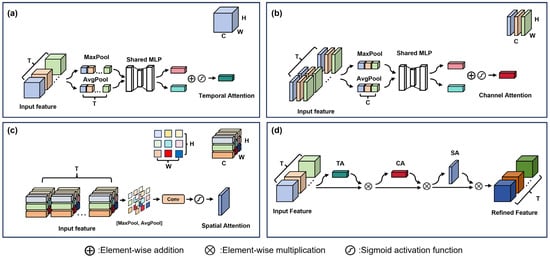

The TCSA module is derived from the multi-dimensional attention mechanism proposed by Yao et al. in 2022 [39] and consists of three sub-modules: temporal attention, channel attention, and spatial attention. These sub-modules are designed to capture temporal sequence dependencies, inter-channel semantic correlations, and spatially salient regions, respectively, thereby enabling adaptive enhancement and suppression of spiking features. Each sub-module can operate independently or jointly; in this study, the three are employed in a combined structure (TCSA) to fully exploit spatiotemporal correlations. A schematic diagram of the module is shown in Figure 6d. The following sections provide a detailed explanation of the underlying principles of each sub-module and their specific application in this study.

Figure 6.

The architecture of TCSA module. (a) the Temporal Attention module, (b) the Channel Attention module, (c) the Spatial Attention module, (d) the whole TCSA module.

The objective of the Temporal Attention module is to capture the dynamic dependencies across different time steps in the input spike sequence, thereby learning “when” to attend to input events. A schematic of the module is shown in Figure 6a. Temporal attention extracts temporal context features by applying both global average pooling and global max pooling over the feature maps across all time steps. These pooled features are then fed into a shared multi-layer perceptron (MLP) to generate temporal attention weights. This process can be formally expressed by the following equations:

where denotes the one-dimensional temporal attention weights, while and represent the outputs of the average pooling and max pooling layers, respectively. denotes the Sigmoid activation function. and are the weight vectors of the linear layers in the shared multi-layer perceptron (MLP), and is the temporal reduction factor used to control the computational load of the MLP.

The Channel Attention (CA) module aims to model inter-channel dependencies in the features, determining “what” semantic features to focus on. A schematic of the module is shown in Figure 6b. The CA module first applies both average pooling and max pooling across the spatial dimensions to obtain global channel descriptors. These two descriptors are then fed into a shared two-layer multi-layer perceptron (MLP) to generate channel attention weights. This process can be formally expressed by the following equations:

where denotes the one-dimensional channel attention weights, while and are the weight vectors of the linear layers in the shared multi-layer perceptron (MLP). The parameter represents the channel reduction factor. To reduce the number of parameters, the weights and of this MLP are shared across different time steps.

The Spatial Attention (SA) module is designed to determine “where” to focus, enhancing salient regions while suppressing background areas. A schematic of the module is shown in Figure 6c. In the spatial attention (SA) mechanism, global average pooling and global max pooling are applied across the channel axis to produce two complementary spatial feature representations. These feature maps are subsequently fused via channel-wise concatenation and fed into a convolutional operation using a 7 × 7 kernel. Afterward, a Sigmoid function is employed to compute the final spatial attention map. The entire procedure can be mathematically formulated as follows:

where denotes the two-dimensional spatial attention weights, and represents the convolution operation with a 7 × 7 kernel.

The three attention modules are sequentially connected in the order of temporal–channel–spatial to form the complete TCSA module. This can be formally expressed as:

2.3.3. EIoU Loss Function

In the SpikeYOLO model, the original framework adopts CIoU [46] as the bounding box regression loss. Building upon DIoU, CIoU further introduces the aspect ratio parameter into the penalty term as an independent regularization factor. This mechanism accelerates and improves bounding box regression by explicitly constraining the predicted box to rapidly approximate the aspect ratio of the ground truth box. The CIoU loss function is defined as follows:

where denotes the aspect ratio penalty factor. When the predicted bounding box has the same aspect ratio as the ground truth, the penalty term collapses to zero. As a result, a gradient coupling phenomenon occurs, where the gradients associated with the width and height parameters become interdependent during backpropagation, ultimately weakening the effectiveness of parameter optimization.

To address the theoretical drawbacks discussed above, we replace the conventional CIoU loss with EIoU [45]. Unlike CIoU, EIoU introduces a decoupled formulation for handling aspect ratio constraints, allowing the bounding box width and height to be optimized independently. By directly regressing these two dimensions, the proposed loss function avoids gradient entanglement during backpropagation. Moreover, this design ensures that effective supervision is retained across diverse aspect ratios, leading to improved convergence behavior and more precise bounding box regression. The EIoU loss function consists of three components: the overlap loss , the center distance loss , and the aspect regression loss . The formal definition of the EIoU loss is given as follows:

where and denote the centers of the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes, respectively; and represent the widths, and and represent the heights of the predicted and ground truth boxes, respectively. The operator computes the Euclidean distance between two points. and denote the width and height of the smallest enclosing box that simultaneously covers both the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes. Owing to its improved numerical stability, EIoU mitigates the regression performance oscillations that can arise in CIoU when the predicted bounding boxes closely match the ground truth in aspect ratio. This increased stability translates into more reliable detection outcomes in challenging environments, such as scenes with uneven lighting, partially occluded tea buds, and complex background interference, ultimately strengthening the robustness of the model and the accuracy of its localization capability.

2.4. Model Evaluation Metrics

In this work, the proposed approach for tea bud detection in real-world conditions is assessed from two main aspects, namely detection capability and computational energy cost. With respect to detection performance, four standard evaluation indicators are employed, including Precision (P), Recall (R), mAP@0.5, and mAP@[0.5:0.95]. Precision reflects the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples, while Recall quantifies the model’s effectiveness in retrieving relevant targets. The mAP@0.5 metric measures accuracy under a fixed IoU threshold of 0.5, whereas mAP@[0.5:0.95] summarizes detection quality over a range of IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95, offering a more holistic evaluation. The detailed mathematical definitions of these metrics are presented subsequently.

In addition to accuracy-related metrics, computational complexity is also a critical factor in evaluating the practical applicability of a model. The computational cost during the inference stage directly affects response latency, energy consumption and real-world deployability, especially in resource- and energy-constrained scenarios. In this study, the number of operations (OPs) is adopted as the metric for measuring model computational complexity. OPs quantify the total number of operations required for a single forward inference pass. For Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), OPs correspond to the number of floating-point operations (FLOPs), which represent the total floating-point computations executed during one forward pass. In contrast, due to the event-driven spiking mechanism inherent to Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs), OPs are defined as the number of spike operations (SOPs), i.e., the total number of spike events generated during a single inference process. The SOPs can be calculated as follows [47]:

where denotes the spike firing rate of the -th network layer, represents the number of time steps of the I-LIF neurons, is the total number of layers in the model, and indicates the number of floating-point operations of the -th layer.

Additionally, it is essential to quantify the energy consumption incurred during the execution of the detection task. On neuromorphic hardware, the number of operations is commonly used as a proxy metric for computational energy cost. For Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), since the vast majority of computations consist of multiply–accumulate operations (MACs) and only a very small fraction involve pure accumulations, these accumulation operations are ignored in our energy estimation. In contrast, Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) exhibit superior energy efficiency on neuromorphic platforms, as neurons participate in computation only when spikes are emitted, and the associated cost is dominated by accumulate operations (ACs). However, many existing SNN-based studies cannot guarantee fully spiking architectures. Consequently, when estimating the energy consumption of such non-fully spiking networks, we also account for MAC operations [30]. Accordingly, this paper defines the energy consumption estimation formulas for ANNs and SNNs as follows:

where denotes the spike firing rate of the -th network layer, while and represent the number of multiply–accumulate (MACs) and accumulation (ACs) operations in the layer, respectively. and denote the energy cost per MAC and AC operation, respectively. In this work, we adopt the standard approach for evaluating energy consumption commonly used in the field of Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs). All computations are assumed to be implemented with 32-bit floating-point precision on 45 nm technology, where the energy costs are and [48].

3. Results

3.1. Experiment Details

Table 2 summarizes the hardware and software configuration of the experimental platform employed in this study.

Table 2.

Experimental platform’s environment settings.

To ensure experimental fairness, we kept the basic hyperparameters listed in Table 3 consistent throughout the training process, while other hyperparameters that are specific to different models were set according to the recommendations in the original papers or official repositories. By standardizing the experimental conditions and hyperparameter settings, we effectively eliminated the interference of external variables, ensuring that the model’s performance was solely influenced by the algorithm’s optimization and the structural design. Further details are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Experimental hyperparameter settings.

3.2. Baseline Model Results

3.2.1. Quantitative Analysis of the Baseline Model

This section aims to systematically evaluate the advantages and limitations of SpikeYOLO in practical deployment scenarios and, based on these findings, to identify directions for model improvement. To ensure the comprehensiveness of the evaluation and the comparability of results, this study selects multiple object detection models as baselines, including YOLOv6, YOLOv7, YOLOv8, YOLOv9, YOLOv10, YOLOv11, and YOLOv12, all of which are mainstream Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)-based detection models [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. All models are trained and tested on the tea bud object detection dataset constructed uniformly in this study, strictly controlling for consistency in data, training strategies, and evaluation metrics. This ensures that independent variables are controlled, the experimental setup is standardized, and the detection results are fair and comparable. The quantitative evaluation results of all models are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

The Performance of the ten models.

As shown in Table 4, SpikeYOLO demonstrates a significant advantage in inference energy consumption, requiring only 65.3 mJ, which is lower than all the compared baseline models. With respect to the total number of operations (OPs), SpikeYOLO achieves 72.6 G, which is lower than that of YOLOv6 (85.8 G), YOLOv7 (104.7 G), YOLOv8 (78.9 G), and YOLOv9 (76.3 G), while being higher than other models such as YOLOv8s and YOLOv8m-MobileNetV4. However, a larger number of operations does not necessarily imply higher energy consumption. On the contrary, owing to its event-driven spiking mechanism, the majority of operations in SpikeYOLO are energy-efficient accumulation operations (ACs). As a result, although SpikeYOLO requires a slightly higher number of operations per forward inference, it consumes less energy overall. This characteristic endows SpikeYOLO with a significant advantage in terms of low energy consumption in practical deployment scenarios.

In terms of detection performance, SpikeYOLO achieves higher Precision (P), Recall (R), mAP@0.5, and mAP@[0.5:0.95], with values of 81.6%, 70.5%, 79.0%, and 57.1%, respectively, compared to YOLOv8 (s), which achieves 77.9%, 70.3%, 78.9%, and 54.2%, and YOLOv8m-MobileNetV4 [49], which achieves 76.1%, 69.5%, 77.9%, and 51.9%. SpikeYOLO outperforms these two lightweight variants of YOLOv8 (m) in both detection performance and energy efficiency, indicating that, compared to conventionally lightweight YOLO models, the improvements in SpikeYOLO are more likely to achieve better detection performance while maintaining low energy consumption.

Although SpikeYOLO demonstrates excellent energy efficiency, its detection performance is clearly inferior to all standard YOLO baseline models. Specifically, mAP@0.5 and mAP@[0.5:0.95], with values of 79.0% and 57.1%, are significantly lower than those of YOLOv9 (m) (81.7% and 61.4%), YOLOv8 (m) (81.5% and 61.0%), and YOLOv11 (m) (81.3% and 61.0%). This limits the practical applicability of SpikeYOLO, particularly in tasks involving complex backgrounds or multi-scale tea bud detection, where false positives and missed detections are more likely to occur. Therefore, improving the existing SpikeYOLO model to develop a variant that maintains its low energy consumption while enhancing detection accuracy has become the central objective of this study.

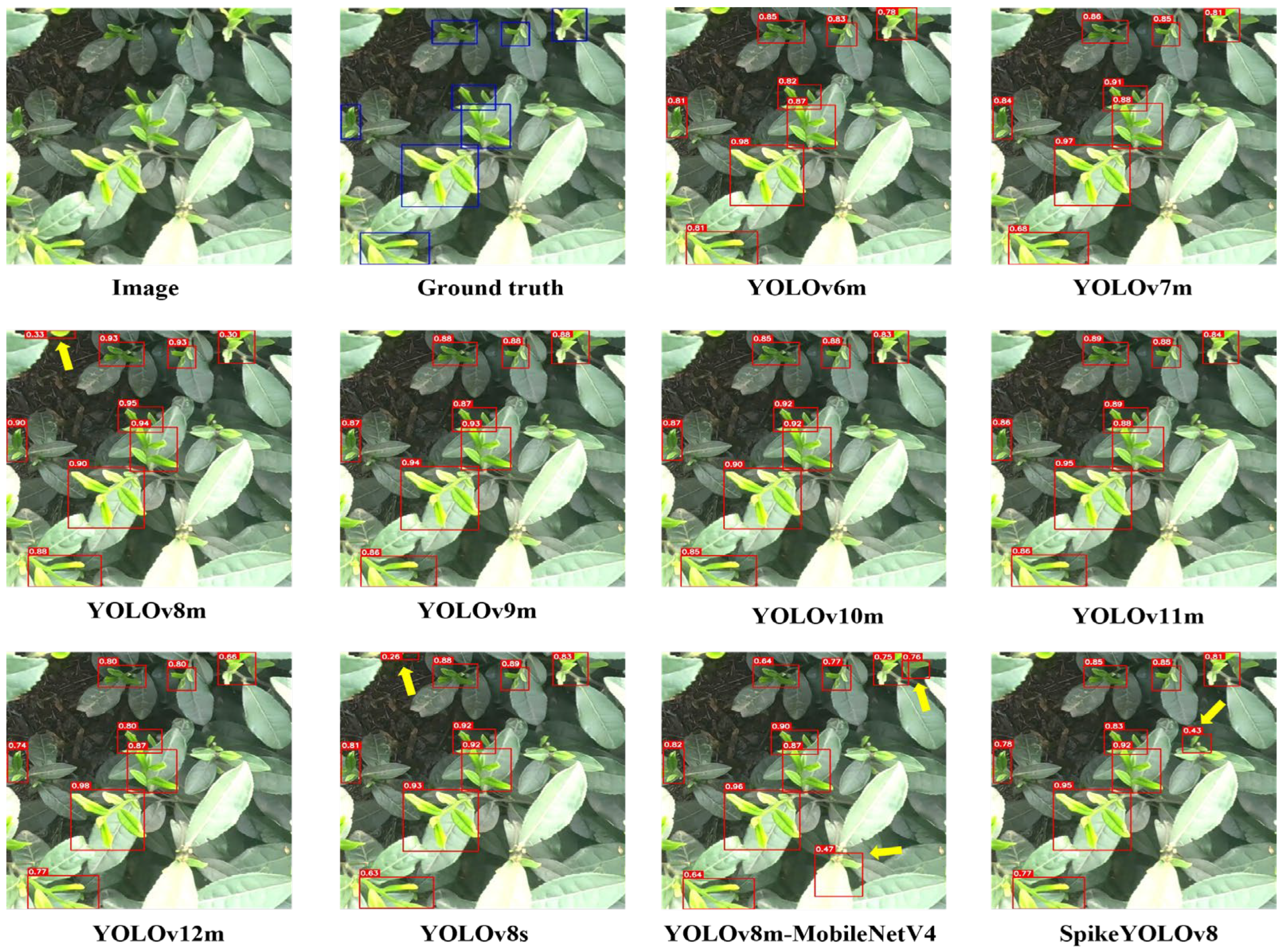

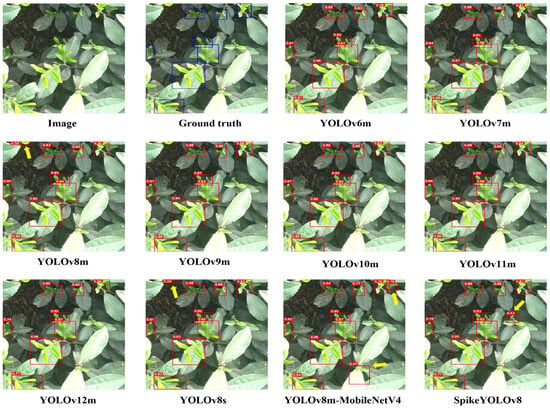

3.2.2. Qualitative Analysis of the Baseline Model

To further evaluate the performance of the baseline models and analyze the differences between SpikeYOLO and other models in real-world detection scenarios, a qualitative analysis was conducted on the ten baseline models, as shown in Figure 7. Experimental results on the tea bud detection dataset indicate that SpikeYOLO still exhibits a gap in detection accuracy compared to standard YOLO models, highlighting the need for further optimization and improvement. To maintain experimental rigor and avoid bias, the images used for model evaluation were kept separate from the training dataset.

Figure 7.

The results of the object detection on the ten baseline models. The yellow arrows point to the falsely detected targets.

Figure 7 presents qualitative results of different models on the tea bud detection task, with yellow arrows indicating regions of false positives or missed detections. As shown, YOLOv9 (m) and YOLOv11 (m) demonstrate strong detection performance, successfully identifying tea buds in various poses with high confidence. YOLOv8 (m) can also detect all tea buds reasonably well, but it occasionally misclassifies small leaves as tea buds. YOLOv6 (m), YOLOv7 (m), YOLOv10 (m), and YOLOv12 (m) correctly detect all tea buds without false positives or missed detections. However, differences in confidence distribution are observed among these models: YOLOv7 (m) and YOLOv12 (m) show lower confidence for tea buds in highly illuminated regions, YOLOv10 (m) exhibits lower confidence for larger tea buds near the image center, and YOLOv6 (m) demonstrates insufficient confidence for smaller tea buds at the image edges. YOLOv8m-MobileNetV4, YOLOv8 (s), and SpikeYOLO occasionally misidentify small leaves as tea buds. Overall, SpikeYOLO outperforms YOLOv8 (s) and YOLOv8m-MobileNetV4, but still lags behind traditional ANN-based YOLO models, particularly in detecting small tea buds located near the image periphery.

3.3. SpikeYOLO Before and After Improvement Results

3.3.1. Quantitative Analysis of the Improved SpikeYOLO

In this section, we systematically evaluate the performance of the proposed GAE-SpikeYOLO model for tea bud detection in natural environments, in comparison with the SpikeYOLO model. The quantitative results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of SpikeYOLO and GAE-SpikeYOLO.

As shown in the experimental results in Table 5, GAE-SpikeYOLO demonstrates a significant performance improvement over the SpikeYOLO model in tea bud detection under natural environments. Compared to SpikeYOLO, it achieves a Precision (P) of 83.0% and a Recall (R) of 72.1%, representing improvements of 1.4% and 1.6%, respectively. The mAP@0.5 and mAP@[0.5–0.95] reach 81.0% and 60.4%, corresponding to increases of 2.0% and 3.3%. Notably, the detection accuracy of GAE-SpikeYOLO approaches or even surpasses that of some mainstream YOLO models based on Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs). Compared with YOLOv8 (m) (81.5% mAP@0.5, 61.0% mAP@[0.5–0.95]), its mAP@0.5 and mAP@[0.5–0.95] are only 0.5% and 0.6% lower, respectively. Compared with YOLOv11 (m) (81.3% mAP@0.5, 61.0% mAP@[0.5–0.95]), the differences are 0.3% and 0.6%. Even relative to the best-performing YOLOv9 (m) (81.7% mAP@0.5, 61.4% mAP@[0.5–0.95]), GAE-SpikeYOLO is only 0.7% and 1.0% lower. At the same time, GAE-SpikeYOLO surpasses YOLOv6 (m), YOLOv7 (m), YOLOv10 (m), and YOLOv12 (m) in detection accuracy, indicating that it has effectively closed the performance gap between Spiking Neural Networks and conventional ANN-based YOLO models.

In terms of energy consumption, GAE-SpikeYOLO also shows a significant advantage, with an energy cost of only 49.44 mJ, representing a 24.3% reduction compared to the original SpikeYOLO model, and lower than those of two lightweight models, YOLOv8m-MobileNetV4 (70.61 mJ) and YOLOv8 (s) (68.08 mJ). Furthermore, GAE-SpikeYOLO achieves an OPs of 58.9 G, which represents a reduction of 15.7 G compared to SpikeYOLO. This decrease in computational operations further enhances its practicality and suitability for real-world deployment scenarios.

These results indicate that GAE-SpikeYOLO outperforms SpikeYOLO across multiple key metrics, achieves detection performance comparable to several ANN-based YOLO models, and exhibits significantly lower energy consumption, demonstrating its effectiveness and reliability for energy-constrained object detection tasks.

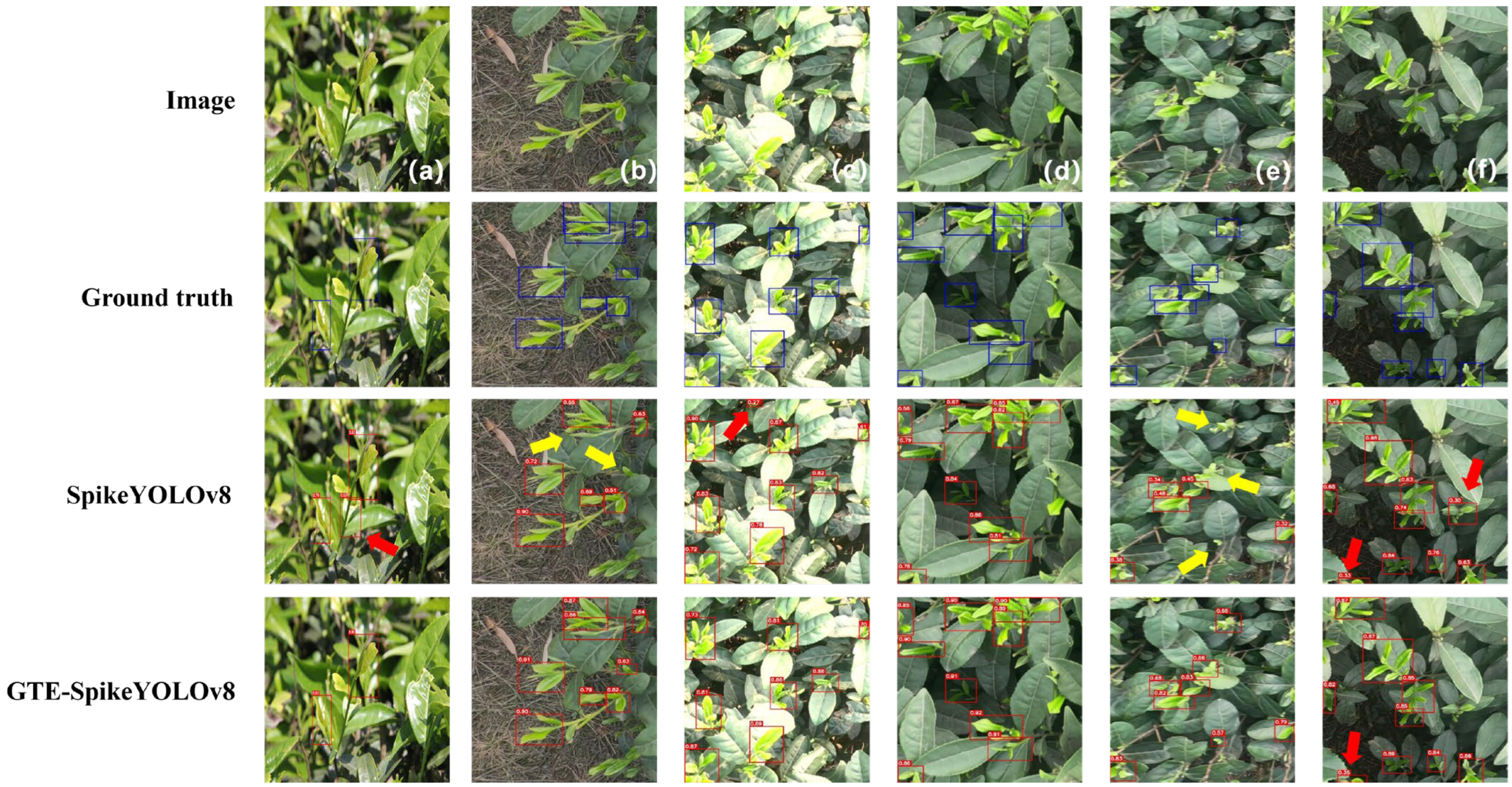

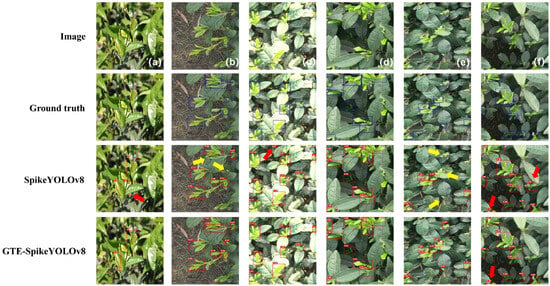

3.3.2. Qualitative Analysis of the GAE-SpikeYOLO

To further assess the performance of our approach, we performed a qualitative comparison between the original SpikeYOLO model and the improved GAE-SpikeYOLO variant. The experimental results show that GAE-SpikeYOLO outperforms SpikeYOLO in detection accuracy, fine-grained detection details, and robustness under complex tea plantation environments. To maintain experimental rigor and avoid bias, the images used for model evaluation were kept separate from the training dataset.

Figure 8a–f present the detection results of the two models in different complex tea plantation scenarios, where yellow and red arrows indicate missed and false detection regions, respectively. Compared with the baseline model, GAE-SpikeYOLO exhibits higher detection stability and accuracy under multiple complex environmental conditions. As shown in Figure 8a–e, in complex tea plantation environments, including image blur, tea bud occlusion, similar colors, complex backgrounds, and strong illumination, SpikeYOLO suffers from false and missed detections. GAE-SpikeYOLO avoids misclassifying branches as tea buds in visually similar backgrounds (Figure 8a), accurately identifies tea buds despite occlusion by other buds or leaves (Figure 8b), prevents misclassifying shadowed leaves as tea buds under strong illumination (Figure 8c), achieves significantly improved accuracy in low-light dark regions (Figure 8d), and fully detects all tea buds even in motion-blurred images (Figure 8e). These results demonstrate that the proposed GAE-SpikeYOLO model shows stronger robustness and generalization capability under complex natural conditions. However, GAE-SpikeYOLO still has certain limitations. As shown in Figure 8f, when both highlight and low-light regions coexist in the same image, leaves in low-light background regions become highly similar to tea buds in appearance, leading to false detections in both models.

Figure 8.

The results of object detection on SpikeYOLO and GAE-SpikeYOLO. The red arrows indicate falsely detected targets, and the yellow arrows indicate missed targets.

3.4. Validation Experiments for Robustness

Illumination conditions have a significant impact on image quality in natural environments. Under strong direct sunlight or low-light conditions, captured images are prone to overexposure and local blurring, which leads to the loss of fine-grained features and consequently degrades object detection accuracy. To systematically evaluate the influence of illumination intensity on detection performance, the validation set was divided into three categories according to lighting intensity: high intensity, moderate intensity, and low intensity.

The corresponding experimental results are reported in Table 6. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed GAE-SpikeYOLO consistently outperforms the baseline SpikeYOLO across tea plantation scenes under all illumination conditions. Specifically, under high light conditions, GAE-SpikeYOLO achieves improvements of 2.1% and 3.2% in mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95, respectively, indicating stronger robustness against interference caused by high exposure. Under moderate light conditions, the mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 metrics are improved by 1.7% and 3.3%, respectively, confirming the model’s stable baseline performance under normal lighting conditions. In low light scenarios, the performance gains are the most pronounced, with mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 increasing by 2.5% and 3.6%, respectively. These results suggest that GAE-SpikeYOLO is particularly effective in suppressing low-light noise and enhancing low-contrast feature representations. Furthermore, compared with the detection results obtained on the complete validation set, the mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 of GAE-SpikeYOLO decrease by only 0.3% and 0.5% under high light conditions, and by merely 0.2% and 0.3% under low light conditions. In contrast, under moderate light conditions, the corresponding metrics even increase by 0.2% and 0.3%. Taken together, these results indicate that the proposed GAE-SpikeYOLO maintains stable and superior detection performance across varying illumination conditions, demonstrating strong robustness and generalization capability.

Table 6.

Comparison of results under different lighting conditions.

3.5. Ablation Analysis

3.5.1. Ablation Analysis of the GAE-SpikeYOLO

Table 7 presents a systematic ablation study conducted on the GAE-SpikeYOLO model to quantify the individual contributions of the GAC encoding scheme, TCSA module, and EIoU bounding box loss function to overall performance. Method (1) serves as the baseline, achieving a Precision of 81.6%, a Recall of 70.5%, a mAP@0.5 of 79.0%, a mAP@[0.5–0.95] of 57.1%, and an energy consumption of 65.3 mJ. In Method (2), the GAC module is introduced for input image encoding. Compared to the baseline, mAP@0.5 and mAP@[0.5–0.95] increase to 79.3% (+0.3%) and 58.5% (+1.4%), respectively, while energy consumption is reduced by 11.5%. These results indicate that GAC enhances the model’s ability to prioritize salient shallow features, and further improves energy efficiency by suppressing spike firing rates in non-informative regions through irrelevant feature inhibition. Method (3) incorporates the TCSA attention module alone. Relative to the baseline, mAP@0.5 and mAP@[0.5–0.95] rise to 79.9% (+0.9%) and 58.8% (+1.7%), respectively, accompanied by a 15.1% reduction in energy consumption. This demonstrates that TCSA strengthens high-level semantic focus, attenuates attention responses to irrelevant semantic areas, and mitigates ineffective membrane potential accumulation in non-salient regions, thereby lowering redundant spike emissions and reducing overall energy expenditure. Method (4) replaces the baseline bounding box loss with EIoU. The model attains an mAP@0.5 of 79.2% (+0.2% over baseline) and mAP@[0.5–0.95] of 58.0% (+0.9% over baseline), corroborating the effectiveness of EIoU in improving bounding box localization accuracy and enhancing regression precision.

Table 7.

The results of the ablation experiments.

In the two-module combinations, Method (5) (GAC + TCSA) improves mAP@0.5 to 80.8% (+1.8% over the baseline) and mAP@[0.5–0.95] to 60.1% (+3.0% over the baseline), while reducing energy consumption to 49.5 mJ (−24.2% over the baseline). This demonstrates that the GAC and TCSA modules exhibit strong functional complementarity, jointly enhancing both detection accuracy and energy efficiency without mutual interference. Compared with Method (1), Method (6) (GAC + EIoU) increases mAP@0.5 and mAP@[0.5–0.95] by 1.5% and 1.9%, respectively, while reducing energy consumption by 11.5%. Method (7) (TCSA + EIoU) achieves mAP@0.5 and mAP@[0.5–0.95] of 80.7% (+1.7% over baseline) and 59.1% (+2.0% over baseline), respectively, with energy consumption reduced to 55.4 mJ (−15.1% over baseline). Finally, Method (8), which integrates all three modules, achieves the best results across all evaluation metrics. Compared to the baseline, precision (P), recall (R), mAP@0.5, and mAP@[0.5–0.95] increase by 1.4%, 1.6%, 2.0%, and 3.3%, respectively, while reducing energy consumption by 24.3%. These improvements provide compelling evidence that the proposed optimization strategy delivers strong effectiveness and synergy for energy-efficient object detection tasks.

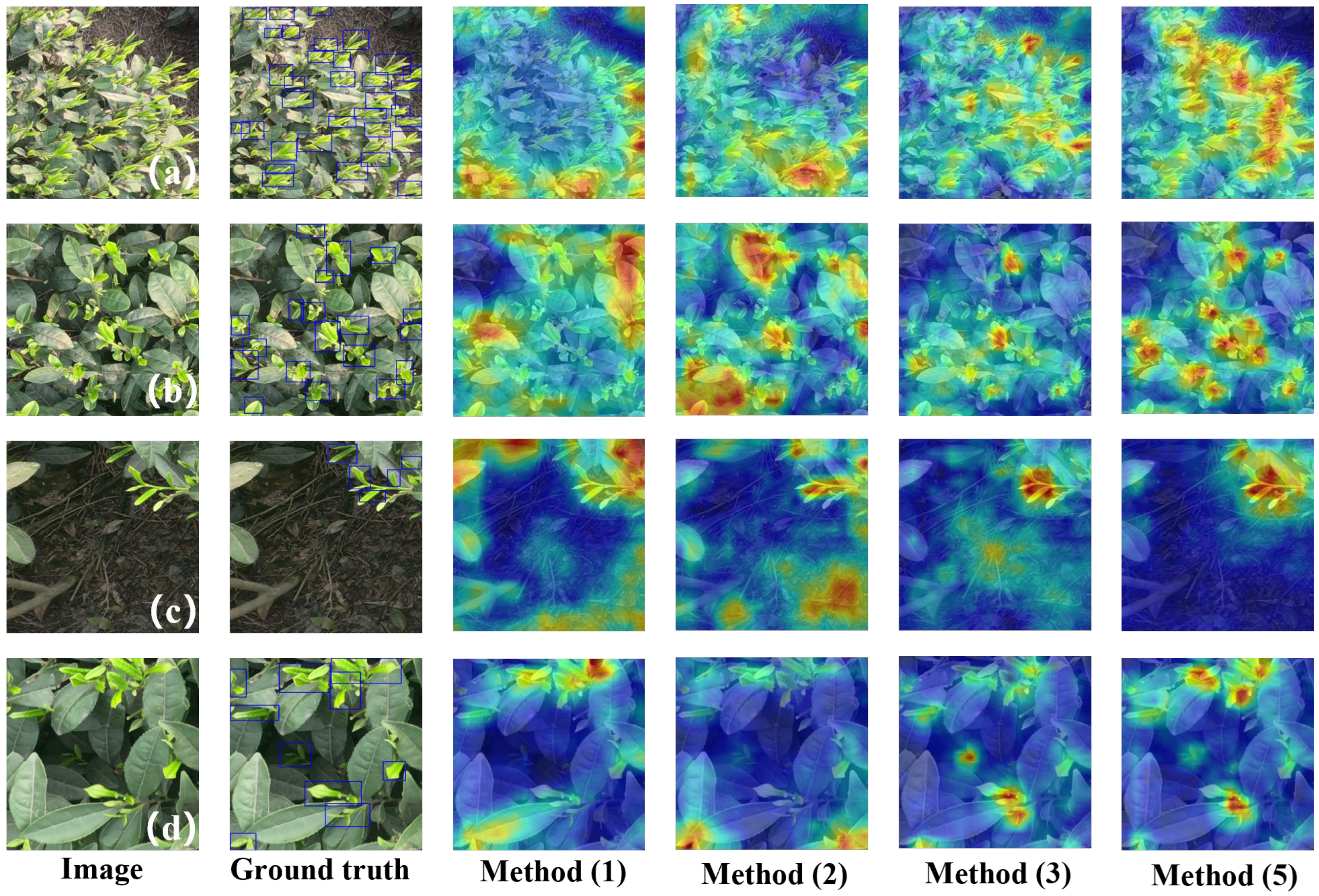

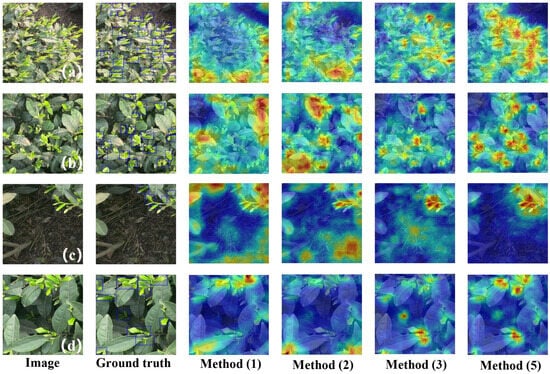

3.5.2. Ablation Analysis of GAC and TCSA Module

From the overall ablation experiments on the GAE-SpikeYOLO model in Section 3.5.1, it can be quantitatively observed that the GAC and TCSA modules have a significant positive impact on the model’s overall performance. To further verify whether the introduced GAC and TCSA modules guide the model to focus on the target regions rather than background noise and to explore their optimization mechanism in depth, this section analyzes the model’s attention distribution from a visualization perspective. In this study, the Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) method is used to visualize the attention distribution of several methods presented in Section 3.5.1. Grad-CAM computes attention weights using gradient information and produces a heatmap over the original image according to these weights. The heatmap uses a color scale from blue to red, with red areas indicating regions that contribute most significantly to tea bud detection [50].

Figure 9 presents the Grad-CAM heatmaps of Method (1), (2), (3), and (5) in the tea bud detection task from Section 3.5.1. Method (1) represents the baseline model without any optimization strategies; Method (2) integrates the GAC module at the input coding stage; Method (3) introduces the TCSA module in the neck network; and Method (5) applies both GAC and TCSA optimization strategies simultaneously. Observing the heatmap of Method (1), the model exhibits relatively high attention responses to background regions without tea buds and tends to focus more on large targets, while its responses to small targets are weak, with some attention even directed toward leaves. This indicates that the baseline model lacks effective attention guidance during shallow feature extraction and deep semantic fusion, resulting in insufficient feature focus.

Figure 9.

Visualization results of heatmaps for four methods.

In contrast, the heatmap of Method (2), which incorporates the GAC module, demonstrates enhanced small-target focus, with a greater number of tea bud regions showing high-response red areas. This suggests that GAC, by generating input spikes with richer spatiotemporal dynamics, effectively strengthens the model’s attention to shallow discriminative features. Nevertheless, in certain samples (e.g., Figure 9b–d), the model still exhibits elevated attention responses to large leaves, background between leaf gaps, and extensive background areas. This behavior is likely due to GAC operating within the shallow network, where attention allocation relies on low-level visual cues such as edges, textures, and local contrast rather than semantic information, making it susceptible to interference from irrelevant high-frequency textures or local contrast variations.

The heatmaps of Method (3), which incorporates the TCSA module, reveal a more distinct semantic attention pattern. Almost all tea bud regions exhibit strong attention responses, while activations in leaf gaps and background areas are effectively suppressed. In particular, as shown in Figure 9d, the model successfully attends to tea buds located in dark regions surrounded by leaves, demonstrating that the temporal-channel-spatial attention mechanism of TCSA enhances the model’s perception of critical semantic regions and facilitates global contextual reasoning across different parts of the target. This contributes to a notable improvement in robustness under challenging conditions such as occlusion and low illumination. Nevertheless, some redundant attention responses remain in background areas as illustrated in Figure 9c. This may be attributed to shallow-level background details, such as branch textures or lighting variations, that persist in higher-level features after repeated downsampling, thereby affecting the attention weight computation of the TCSA module.

An overall comparison of the heatmaps from Method (1) and Method (5) shows that when both the GAC and TCSA modules are incorporated, the model exhibits highly focused attention responses across all tea bud targets, while responses to background areas are substantially suppressed. This result indicates a strong synergistic effect between the two optimization mechanisms. GAC guides the extraction of shallow features at the input coding stage through a gating mechanism, enhancing the model’s perception of critical local details. TCSA employs temporal-channel-spatial attention to direct the model’s focus toward semantically consistent tea bud regions. This collaborative optimization substantially reduces false positives and missed detections, further improving the model’s applicability and robustness in complex natural tea plantation environments.

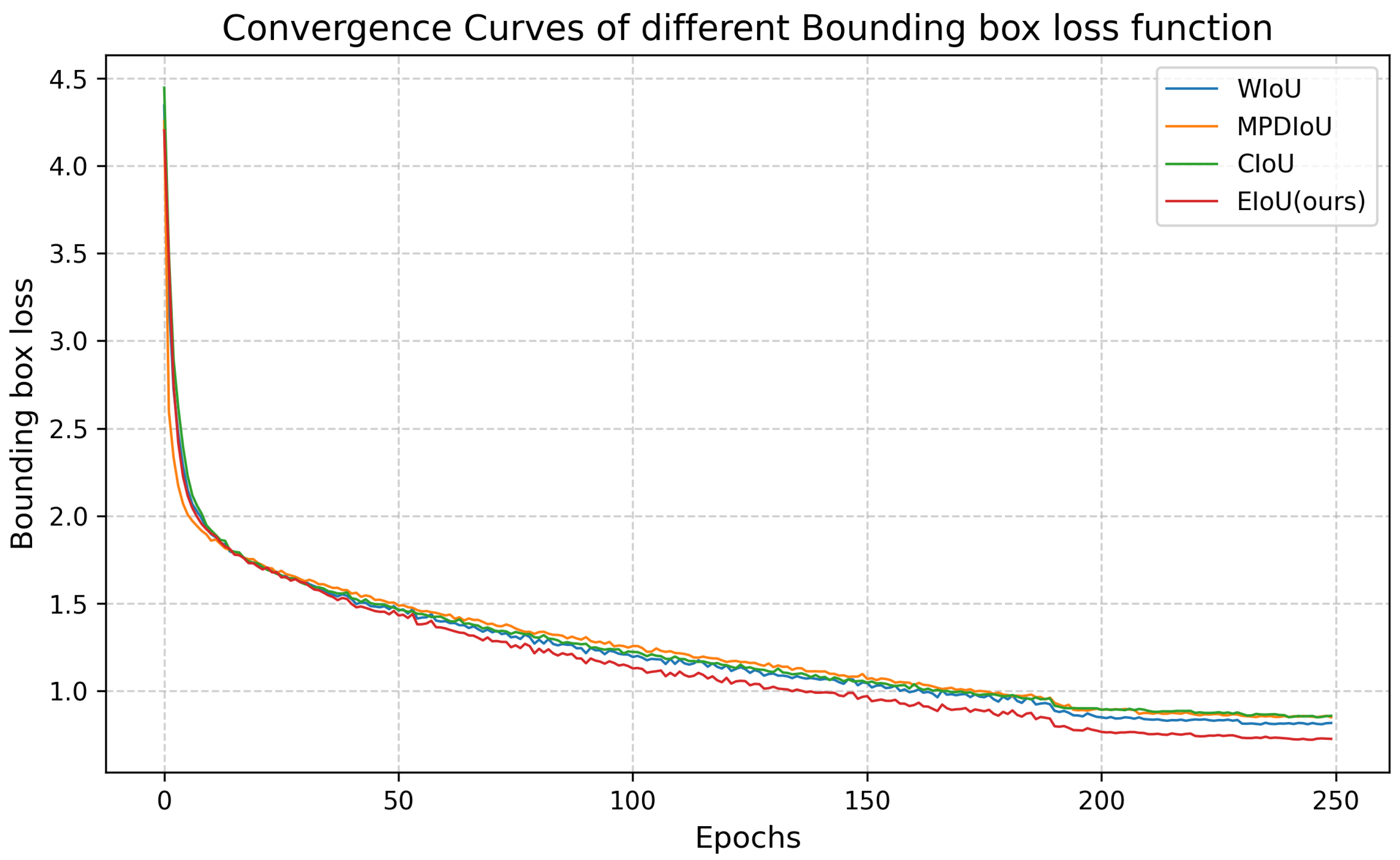

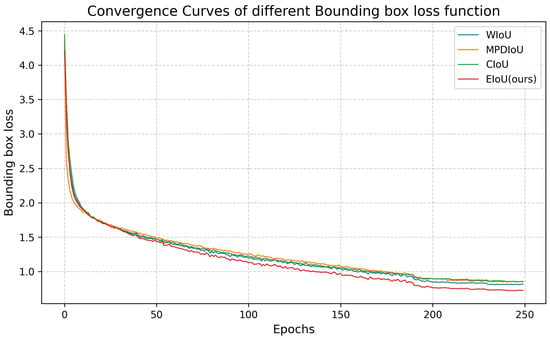

3.6. Bounding Box Loss Function Replacement Results

From the ablation experiment results in Section 3.5.1, it can be quantitatively observed that replacing the bounding box loss function from CIoU to EIoU significantly improves the overall performance of the GAE-SpikeYOLO model. To further investigate the specific impact of different bounding box loss functions on the model’s detection performance, this section compares the performance of GAE-SpikeYOLO under the same training conditions using four loss functions: CIoU, EIoU (the method adopted in this study), MPDIoU [51], and WIoU [52]. The quantitative evaluation results for each loss function are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Results of the four bounding box loss functions.

As presented in Table 8, the MPDIoU loss leads to a reduction in detection performance compared with the original CIoU, with mAP@0.5 and mAP@[0.5:0.95] dropping by 1.0% and 1.2%, respectively. Similarly, the WIoU loss also results in a slight performance decline, reducing mAP@0.5 and mAP@[0.5:0.95] by 0.2% and 0.4%. In contrast, EIoU demonstrates an improvement over CIoU, with mAP@0.5 and mAP@[0.5:0.95] increasing by 0.2% and 0.3%, and Precision (P) and Recall (R) rising by 0.1% and 0.7%, respectively. Based on these results, EIoU is chosen as the final bounding box regression loss for this study, replacing the original CIoU.

To further verify the advantages of EIoU, Figure 10 presents the convergence curves of the four loss functions during training. It can be observed that MPDIoU demonstrates faster convergence than CIoU during the initial training stage and even exceeds the performance of the best-performing EIoU. However, as training progresses, the distance penalty term in MPDIoU gradually dominates the optimization direction, weakening the fine-grained constraints for high-IoU samples. This limits the subsequent decrease in loss, resulting in a final loss value that is even higher than that of CIoU. In comparison, WIoU shows a smoother decline throughout training, but its advantage over CIoU is not significant. Notably, EIoU enables a faster loss reduction during the early training stage compared with CIoU, demonstrating higher convergence efficiency. This improvement is primarily attributed to the decoupling of width and height parameters, which resolves the inherent gradient coupling issue in CIoU. Furthermore, EIoU consistently maintains lower loss values throughout the entire training process, indicating its superior capability in capturing the geometric characteristics of the ground truth bounding boxes.

Figure 10.

Comparison of convergence curves between WIoU, MPDIoU, CIoU and EIoU.

3.7. Results of GAE-SpikeYOLO Under Different Hyperparameter T Values

In the GAE-SpikeYOLO model, two core hyperparameters that significantly affect model performance are the time step of the I-LIF neurons and the maximum integer spike value during training. The time step controls the temporal integration length of the neurons. A larger allows neurons to accumulate and propagate spike information over a longer temporal dimension, enhancing the representation of spatiotemporal features and improving model accuracy, but it also increases computational complexity and energy consumption. The parameter represents the maximum integer spikes that a neuron can emit during training, reflecting the precision of spike quantization. A larger effectively reduces quantization errors and improves representational accuracy, but it similarly increases computational burden and energy consumption. Accordingly, this section conducts a comparative analysis of model performance under different combinations of the hyperparameters and . Specifically, and are considered, resulting in nine groups of comparative experiments with different hyperparameter settings. It is worth noting that when both and are relatively small, the model may fail to converge properly. Therefore, only the experimental configurations that successfully converge are included in the analysis. The detailed experimental results are summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

Results of GAE-SpikeYOLO under different hyperparameters T and D.

From an overall perspective, when is fixed, the detection performance of the model consistently improves as increases, accompanied by a corresponding increase in inference energy consumption. Similarly, when is fixed, a larger value of leads to higher detection accuracy, while also resulting in increased inference energy consumption. By comparing models (3), (6), and (7), it can be observed that models (3) and (6) exhibit poor detection performance, achieving only (mAP@0.5 of 80.0% and mAP@[0.5–0.95] of 58.8%) and (mAP@0.5 of 78.6% and mAP@[0.5–0.95] of 56.5%), respectively. Although model (7) attains relatively high detection accuracy (mAP@0.5 of 81.0% and mAP@[0.5–0.95] of 60.4%), its inference energy consumption reaches 73.6 mJ. These results indicate that when is set too small, the detection performance of the model degrades significantly. However, further analysis of models (5) and (9) reveals that excessively large values of lead to substantially higher inference energy consumption (75.2 mJ and 143.3 mJ, respectively), while yielding only marginal performance gains compared with models (4) and (8), with improvements of merely 0.4% and 0.2% in mAP@[0.5–0.95], respectively. A similar trend is observed in the analysis of : overly large values of increase inference energy consumption, whereas excessively small values constrain the model’s achievable performance. By jointly comparing models (2), (4), (6), and (7), model (4) demonstrates superior detection performance with significantly lower inference energy consumption, indicating that its hyperparameter configuration is more reasonable. As a result, model (4) represents a favorable trade-off between detection accuracy and inference energy efficiency. Consequently, in this work, and are set to 2 and 4, respectively, to balance detection performance and inference energy consumption.

4. Discussion

Accurate and automated detection and localization of tea tree buds is of significant importance for the development of intelligent tea bud harvesting systems. In current agricultural production scenarios such as tea plantations, bud picking and maturity assessment still rely primarily on human expertise, which is not only time-consuming and labor-intensive but also prone to subjective errors [53]. To reduce human involvement and improve operational efficiency, researchers have recently proposed various computer vision-based crop detection methods, which have shown promising results in tasks such as fruit and vegetable maturity recognition and disease identification [54,55,56,57]. However, most existing mainstream methods are based on Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), whose high demand for floating-point computations poses challenges in deploying these models on energy-constrained edge devices, leading to high computational costs and power consumption [58,59]. This limitation is particularly critical in applications requiring real-time inference, such as unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) inspection and field mobile robots, where conventional ANNs models struggle to maintain detection accuracy while controlling energy consumption.

Based on the issues outlined above, this study explores the feasibility of applying Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) to tea bud detection in natural scenes and proposes an improved detection model, GAE-SpikeYOLO, which integrates the GAC module, the TCSA mechanism, and the EIoU loss function on the original SpikeYOLO model. To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed model in practical scenarios, a tea bud detection dataset containing 7842 images was used. The dataset covers multiple weather conditions, diverse shooting angles, and complex tea plantation environments. On this basis, ten baseline models, including seven mainstream object detection models, two lightweight detection models, and one Spiking Neural Networks model, were systematically analyzed alongside the proposed GAE-SpikeYOLO through both quantitative and qualitative evaluations. The experimental results indicate that, under identical datasets, training hyperparameters, and hardware platforms, the baseline SNN model already achieves a favorable balance between energy consumption and detection performance. The proposed GAE-SpikeYOLO model further achieves significant improvements across multiple metrics, including mAP, IoU, Precision, Recall, and energy consumption. Specifically, GAE-SpikeYOLO attains a Precision of 83.0%, a Recall of 72.1%, a mAP@0.5 of 81.0%, and a mAP@[0.5:0.95] of 60.4%, with an energy consumption of 49.4 mJ. Compared to the original SpikeYOLO model, this approach achieves improvements of 1.4%, 1.6%, 2.0%, and 3.3% in Precision, Recall, mAP@0.5 and mAP@[0.5:0.95], respectively, and achieves reductions of 24.3% in energy consumption. These results demonstrate that the proposed detection model substantially reduces energy consumption while maintaining high detection accuracy, making it more suitable for deployment on energy-constrained edge devices and providing a promising solution for efficient and energy-efficient tea bud detection in complex natural environments.

Based on qualitative analysis and ablation experiments, the proposed model demonstrates a clear improvement over SpikeYOLO in detecting small tea bud targets, while exhibiting enhanced robustness under challenging conditions such as occlusion and illumination variation. These performance gains can be attributed to the joint optimization of input encoding, deep feature attention, and bounding box regression. Specifically, the GAC module enhances the representation of partially occluded and low-level tea bud features by selectively amplifying informative spatiotemporal responses and suppressing background-induced spike activity. Moreover, the introduced TCSA module reinforces high-level semantic consistency by adaptively emphasizing semantically relevant regions, thereby reducing false detections caused by leaf occlusion, specular highlights, and background interference. In addition, replacing the CIoU loss with EIoU improves localization stability through decoupled width-height regression, which is advantageous for small and occluded targets. Consequently, the proposed model achieves more accurate and reliable tea bud detection across varying levels of occlusion and illumination conditions.

Compared with existing object detection methods for tea buds [23,24,25,26,27], this study explores how Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) perform on the tea bud detection task. The improved model not only exhibits significant energy-efficiency advantages but also achieves clear improvements in detection accuracy over the original model. This effectively addresses the common issue of insufficient detection performance observed in conventional SNNs in practical applications.

Although this study has achieved promising experimental results, several issues warrant further investigation. Compared with ANNs models, the training of SNNs models is more sensitive to gradient estimation and parameter updates, which may still lead to false detections under natural disturbances such as extreme lighting conditions.

In future work, we aim to design an attention module specifically for Spiking Neural Networks that completely eliminates floating-point operations while dynamically computing attention weights. This will further reduce the model’s overall energy consumption and improve its deploy ability in energy-constrained environments [44]. At the same time, we plan to deploy the proposed model on edge hardware platforms with neuromorphic brain-like characteristics to evaluate its real-time performance, power consumption, and operational stability in actual tea plantation environments. In addition, taking advantage of the inherent energy efficiency of SNNs, we will explore the scalability of this approach to other crop detection tasks, including apples, bananas, and various other fruits and vegetables.

5. Conclusions

This study focuses on the task of tea bud detection and investigates the application of energy-efficient object detection techniques in energy-constrained environments. To meet the energy-efficient deployment requirements of edge detection devices while maintaining detection performance, the Spiking Neural Networks model SpikeYOLO, which has demonstrated strong performance in object detection, was selected as the baseline model. Based on this, an energy-efficient object detection model, GAE-SpikeYOLO, was proposed. By comparing it with nine mainstream object detection models, including YOLOv6 through YOLOv12, YOLOv8m-MobileNetV4, and YOLOv8 (s), the advantages and limitations of SpikeYOLO were analyzed, providing guidance for subsequent improvements. The introduction of Gated Attention Coding (GAC) and the Temporal-Channel-Spatial Attention (TCSA) module significantly enhanced the model’s performance while reducing overall energy consumption. Furthermore, replacing the bounding box loss function with EIoU led to additional improvements in detection performance. On the tea bud detection dataset, the proposed model achieved a Precision of 83.0%, a Recall of 72.1%, a mAP@0.5 of 81.0%, a mAP@[0.5:0.95] of 60.4%, and an energy consumption of 49.4 mJ. In comparison to the original SpikeYOLO model, this approach demonstrates improvements of 1.4%, 1.6%, 2.0%, and 3.3% in Precision, Recall, mAP@0.5, and mAP@[0.5:0.95], respectively, while energy consumption decreased by 24.3%. In addition, ablation experiments demonstrated that each optimization module in the proposed model is effective. Finally, experiments were conducted under identical conditions to evaluate the model with different time steps . The results indicate that when , the proposed model achieves the best balance between detection performance and energy efficiency. In summary, the method presented in this study provides a promising and efficient energy-efficient solution for intelligent tea bud detection in precision agriculture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L., J.J. and H.L.; Methodology, J.L., J.J. and H.L.; Validation, J.L., J.J. and H.L.; Investigation, J.L., J.J., H.L., G.Z., M.Y., Y.C. and A.C.; Resources, Y.Z.; Data curation, J.L., J.J., H.L., H.C., Y.C., A.C. and R.S.; Writing—original draft preparation, J.L., J.J. and H.L.; Writing—review and editing, J.L., J.J., G.Z. and M.Y.; Visualization, J.L., J.J. and H.L.; Supervision, Y.Z.; Project administration, Y.Z., J.L., J.J. and G.Z.; Funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71712250410247), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (No. WGXZ2023054L), and 2024 National Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students (202511078050).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this research is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. This dataset is not available to the public because of the laboratory privacy concerns.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest for this article.

References

- FAO. Tea: A Resilient Sector; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://www.fao.org/international-tea-day/home/tea-a-resilient-sector/en (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- ITC-Credible Accurate Tea Statistics-.(n.d.). Retrieved 24 September. 2022. Available online: https://inttea.com/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Wang, C.; Li, H.; Deng, X.; Liu, Y.; Wu, T.; Liu, W.; Xiao, R.; Wang, Z.; Wang, B. Improved You Only Look Once v.8 Model Based on Deep Learning: Precision Detection and Recognition of Fresh Leaves from Yunnan Large-Leaf Tea Tree. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Gui, Z.; Yu, T. Tea Bud Detection and 3D Pose Estimation in the Field with a Depth Camera Based on Improved YOLOv5 and the Optimal Pose-Vertices Search Method. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-M.; Yu, C.-P.; Ma, J.-H.; Ouyang, J.-X.; Zhao, Z.-M.; Xuan, Y.-M.; Fan, D.-M.; Yu, J.-F.; Wang, X.-C.; Zheng, X.-Q. Tea yield estimation using UAV images and deep learning. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 212, 118358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Yuan, M.; Wang, P.; Zhang, R.; Sun, J.; Mao, H. Tea diseases detection based on fast infrared thermal image processing technology. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 3459–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Feng, J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, B.; Wang, T.; Zhang, C.; Xu, S.; Zhang, L.; Zuo, G.; Lv, Y.; et al. Detection and Correction of Abnormal IoT Data from Tea Plantations Based on Deep Learning. Agriculture 2023, 13, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. What is YOLOv5: A deep look into the internal features of the popular object detector. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.20892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A Single-Stage Object Detection Framework for Industrial Applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable Bag-of-Freebies Sets New State-of-the-Art for Real-Time Object Detectors. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ding, Z.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, K. The tea buds detection and yield estimation method based on optimized YOLOv8. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 338, 113730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Yeh, I.-H.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv9: Learning What You Want to Learn Using Programmable Gradient Information. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.13616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14458. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv11: An Overview of the Key Architectural Enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. YOLOv12: Attention-Centric Real-Time Object Detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sa, I.; Ge, Z.; Dayoub, F.; Upcroft, B.; Perez, T.; McCool, C. Deepfruits: A fruit detection system using deep neural networks. Sensors 2016, 16, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargoti, S.; Underwood, J. Deep fruit detection in orchards. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 3626–3633. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Han, Q.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Zou, X. YOLO-BLBE: A Novel Model for Identifying Blueberry Fruits with Different Maturities Using the I-MSRCR Method. Agronomy 2024, 14, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Nguyen, M.; Yan, W.Q. Apple ripeness identification from digital images using transformers. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 7811–7825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appe, S.N.; Arulselvi, G.; Gn, B. CAM-YOLO: Tomato detection and classification based on improved YOLOv5 using combining attention mechanism. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2023, 9, e1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Gu, J.; Xiong, T.; Wang, Q.; Huang, J.; Xi, Y.; Shen, Z. RFA-YOLOv8: A Robust Tea Bud Detection Model with Adaptive Illumination Enhancement for Complex Orchard Environments. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Chen, L.; Chen, M.; Ma, Z.; Deng, F.; Li, M.; Li, X. Tender Tea Shoots Recognition and Positioning for Picking Robot Using Improved YOLO-V3 Model. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 180998–181011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Gu, J.; Wang, H.; Hu, T.; Fang, X.; Pan, Z. Method for Identifying Tea Buds Based on Improved YOLOv5s Model. Nongye Gongcheng Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2023, 39, 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, J.; Wu, D.; Xu, H.; Chen, J.; Tong, J. Tea bud detection based on multi-scale convolutional block attention module. J. Food Process Eng. 2024, 47, e14556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, B.; Chen, J.; Zhang, M.; Cui, Y.; Tang, J. RT-DETR-Tea: A Multi-Species Tea Bud Detection Model for Unstructured Environments. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Jaiswal, A.; Panda, P. Towards spike-based machine intelligence with neuromorphic computing. Nature 2019, 575, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Q.; Chou, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, J.; Mei, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, G. Deep Directly-Trained Spiking Neural Networks for Object Detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.11411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, M.; Zhang, W. SpikSSD: Better Extraction and Fusion for Object Detection with Spikin g Neuron Networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.15151. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Yao, M.; Chou, Y.; Xu, B.; Li, G. Integer-Valued Training and Spike-Driven Inference Spiking Neural Network for High-performance and Energy-efficient Object Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.20708. [Google Scholar]

- Rullen, R.V.; Thorpe, S.J. Rate Coding Versus Temporal Order Coding: What the Retinal Ganglion Cells Tell the Visual Cortex. Neural Comput. 2001, 13, 1255–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comsa, I.M.; Potempa, K.; Versari, L.; Fischbacher, T.; Gesmundo, A.; Alakuijala, J. Temporal Coding in Spiking Neural Networks with Alpha Synaptic Function: Learning with Backpropagation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.13223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Huh, S.; Lee, J.; Choi, K. Deep neural networks with weighted spikes. Neurocomputing 2018, 311, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhao, J.; Su, L.; Jiang, N.; Hu, Q. Spiking Neural Networks for Object Detection Based on Integrating Neuronal Variants and Self-Attention Mechanisms. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Li, F.; Mo, Z.; Cheng, J. GLIF: A Unified Gated Leaky Integrate-and-Fire Neuron for Spiking Neural Networks. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.13768. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, M.; Gao, H.; Zhao, G.; Wang, D.; Lin, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, G. Temporal-wise Attention Spiking Neural Networks for Event Streams Classification. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10201–10210. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, M.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Y.; Deng, L.; Tian, Y.; Xu, B.; Li, G. Attention Spiking Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 9393–9410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.06521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiling12. Tea Buds YOLO Dataset; Kaggle: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/meiling12/tea-budsyolo (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Slygirl. Tea Shoots—Object and Keypoints Detection; Kaggle: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/slygirl/tea-shoots-object-and-keypoints-detection (accessed on 13 September 2025).