Abstract

Leaf litter accumulation in tea soil contributes to soil sickness due to increased soil acidification and the release of allelochemicals. Microbe-assisted vermitechnology-based decomposition of potentially hazardous metal (PHM) containing tea leaf litter (TLL) biomass offers an environmentally friendly alternative compared to synthetic fertilizer-based products. This research investigated the efficacy of microbe-assisted TLL vermicompost as an organic amendment for okra cultivation, focusing on biochemical traits, microbial activity, and bioavailability of other micro and macronutrients of soil. The findings suggested that treatment T5 exhibited a significant increase in soil microbial activity, higher yield, enhanced biochemical traits, and negligible PHM bioavailability post-harvest, compared to chemical fertilizer-treated soil (T9). At the post-harvest stage, the bioavailable PHM content was found to be minimal in treatment T5 (DTPA_Cr = 2.91 ± 0.82; DTPA_Ni = 2.73 ± 0.39; DTPA_Pb = 2.03 ± 0.12). The FIAM-HQ value was below 0.5 for every treatment, indicating that okra grown on TLL vermicompost poses a negligible health hazard associated with PHM. Fuzzy-TOPSIS ranked T5 highest among the treatments in terms of agronomic performance. Sobol sensitivity analysis successfully predicted the influence of biochemical traits on the agronomical parameters of okra. Based on a pot trial experiment, the preliminary findings indicated that application of microbe-assisted TLL vermicompost has successfully increased the yield by 1.22-fold with respect to chemical fertilizer-treated soil. Overall, this study investigates the efficacy of microbe-assisted TLL vermicompost in enhancing okra yield, thereby contributing to sustainable agricultural development and environmentally friendly practices.

1. Introduction

Okra is a highly valued seasonal vegetable widely cultivated in tropical, subtropical regions across the globe [1]. Okra plant (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.)) is a summer crop in India, while in far east countries, its tender leaves are also consumed. India holds a significant position in okra cultivation with an annual production of 6146 metric tons and a productivity of 11.6 metric tons/hectare [2]. Daily consumption of okra is associated with a lowering of blood sugar and cholesterol levels, even though it is beneficial for asthma patients [3]. For its anti-cancerous property and other numerous health benefits, diet consultants often recommend incorporating okra into an individual’s diet [4].

The “Green Revolution” modernized agriculture with new techniques, but excessive use of agrochemicals has harmed soil health, depleted nutrients, and led to loss of biodiversity [5]. Inorganic fertilizers play a pivotal role in boosting crop production and are a key component of modern agriculture [6]. However, indiscriminate use of chemical fertilizers results in soil acidification, nutrient loss, and compaction. Compost offers multiple advantages over traditional agriculture practices as it improves soil health, increases water retention, and supports beneficial microbes, reducing the need for synthetic inputs [7]. Amongst several other composting techniques, earthworm and microbe-assisted tea compost has gained popularity, with new formulations and application systems being developed to suit various crops and cropping systems [8]. Acidophilic tea plants tend to accumulate potentially hazardous metals (PHMs) from soil. PHM contamination in tea soil is influenced by multiple factors, including soil physicochemical characteristics, plantation age, and both geogenic and anthropogenic activities [9]. Pruned tea leaf litter (TLL) can lead to soil degradation in tea plantations by accumulating PHMs and polyphenols, which may negatively affect plant growth and yield [10]. Although pruning is commonly used to manage tea plants and boost productivity, the substantial return of pruned material to the soil can introduce active allelochemicals and lignocellulosic waste. These compounds may cause soil acidification and disrupt microbial communities, ultimately reducing plant growth and yield, especially in long-standing monoculture systems [11]. Therefore, an urgent need has been established for a sustainable waste management system for the pruned TLL. Aerobic composting and microbe-enriched vermicomposting of TLL can be regarded as a cost-effective, eco-friendly, sustainable waste management practice. The chief components of leaf litter biomass are lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose, which are highly resistant to breakdown during composting. Use of lignocellulolytic microorganisms has been recommended by many researchers to enhance the decomposition rate of the composting process [12,13]. Additionally, Earthworms also play a vital role in composting by minimizing the volume of organic waste and producing valuable by-products like antioxidants, metallothionein, and cytochrome P450 enzymes to combat PHM stress [14]. Earthworm guts are a reservoir of many hydrolytic enzymes like lipase, amylase, protease, and cellulase that accelerate the organic matter breakdown rate [15]. Numerous studies have reported positive effects from the application of tea compost, both as organic substrate additives and in the suppression of soil-borne diseases. For instance, compost teas derived from agro-wastes have shown to significantly enhance the growth, biochemical properties, and yield of okra when applied weekly at full dose [16]. Despite having multiple beneficial traits of the TLL vermicompost product, it is important to assess the PHM uptake (Cr, Ni, and Pb) capacity of the plants grown in the TLL compost. Primary staple crops and other seasonal vegetables might have the tendency to accumulate high concentrations of PHMs in their plant parts (root, shoot, and grain). This accumulation might contribute to a significant risk to the food chain. To evaluate any possible PHM uptake by crops growing in PHM-contaminated leaf litter vermicompost, the solubility-free ion activity model (FIAM) can be employed [17]. Additionally, the technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) is an effective multi-criteria decision-making tool that ranks potential alternatives based on their Euclidean distances from the positive ideal solution (Si+) and the negative ideal solution (Si−). By incorporating information entropy, TOPSIS enhances the objectivity of criteria weighting [18]. Furthermore, the Fuzzy-TOPSIS approach has been applied to rank the best treatment on the basis of agronomical traits under uncertain or imprecise conditions. Also, Sobol sensitivity analysis was introduced in this study to predict the influence of biochemical attributes on agronomical parameters of okra.

Moreover, TLL accumulation in soils contributes to acidification, reduced fertility, and PHM accumulation due to its lignocellulosic recalcitrance. To achieve complete decomposition of this lignocellulosic biomass of TLL, the vermicompost was enriched with lignocellulose-degrading microbial inoculants, which also act as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR). This bioaugmented vermicompost not only improves soil fertility but also aids in reducing the mobility of PHMs by promoting their immobilization. Microbe-assisted vermicomposting of TLL can be a sustainable amendment for okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) by improving soil–plant interactions, reducing PHM bioavailability, and enhancing nutrient availability. To our best knowledge, there is no data on the efficacy of microbe-assisted TLL vermicompost on agriculturally important horticulture crops like okra. To bridge the research gap, a pot experiment has been conducted focusing on okra cultivation using microbe-assisted tea leaf litter vermicompost. Furthermore, advanced multivariate techniques, namely Fuzzy-TOPSIS and Sobol sensitivity analysis, were employed in this study to identify the most effective treatment on the basis of agronomic attributes and to predict the influence of biochemical parameters on okra growth. Therefore, the objectives of our research are (i) to enumerate the efficacy of microbe-assisted vermi-converted PHM containing TLL as a soil conditioner, (ii) to evaluate the biochemical properties of okra and microbial activity, physicochemical properties, and changes in PHM concentration of soil of okra plants treated with microbe-assisted vermicompost, (iii) to assess the most appropriate treatments on the basis of agronomical traits associated with treatments, multi-criteria decision-making technique Fuzzy-TOPSIS analysis was performed, and (iv) to predict the effect of biochemical traits on agnomical attributes of okra through SOBOL sensitivity analysis. Therefore, the integration of these analytical tools with conventional laboratory evaluation will contribute to evaluating the efficacy of TLL vermicompost on okra yield, promoting sustainable agricultural development on a global scale.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Microbe-Enriched Vermicompost from TLL

Pruned leaf litter (TLL) was brought from small tea growers of North Bengal, India. The primary characteristics of different TLL composts were described in Table S6. Adult and healthy earthworms (Eisenia fetida) were sourced from a vermiculture unit located in Giridih, Jharkhand, India, for the study. Cow dung (CD) utilized for this vermicomposting procedure was sourced from a nearby dairy farmhouse, adjacent to the experimental laboratory. Raw TLL samples were mixed with cow dung (CD) in a 1:1 (w/w) ratio, and 500 g of each mixture was placed into thoroughly cleaned and perforated composting units (2.5 ft × 4.75 ft × 1.1 ft). For vermicomposting, healthy adult earthworms were introduced into the treatment mixture (10 pc/kg), whereas aerobic compost was prepared without earthworms. By the end of the composting period, the feedstock had transformed into an earthy-smelling, dark brown product, which was sieved for further analysis. All compost samples exhibited a C/N ratio of 10–16, water-holding capacity of 87–91%, C/N of organic water extract (6.2 ± 0.79), Humus-C/Organic-C (25.12 ± 1.34%), Humic acid-C/Organic-C (18.3 ± 0.68%), and Humic acid-C/Fulvic acid-C ratio (1.97 ± 0.012), which are well-established indicators of compost maturity. To further validate compost quality, a germination index (GI) assay was performed using surface-sterilized okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) seeds. GI values exceeded 80% across all treatments, confirming the production of mature, non-phytotoxic compost suitable for agricultural application. To enhance the composting process, a ligninolytic bacterium (Pantoea dispersa) and a lignocellulolytic bacterium (Bacillus xiamenensis) were applied individually as well as in combination. Both bacterial strains are recognized as effective plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPRs) with the ability to solubilize potassium, phosphate, and zinc, and to produce key phytohormones such as auxins and gibberellins. Prior to their application in the feedstock, an interaction study was performed to confirm the successful co-existence and compatibility of the two bacterial strains. The treatment details are described in Table 1. Following the process, the resulting vermicompost was harvested, sieved, and stored in polythene bags for subsequent crop trials.

Table 1.

Description of experimental treatments for the okra pot study.

2.2. Design of Trial Pot Experiment

The pot experiment was conducted during June–September of 2024–2025 for two consecutive years at the Experimental Farm of the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI), Jharkhand, India. Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.)) is a prominent fruit vegetable widely cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions, including India, Africa, and Turkey. Valued for its nutritional content, okra is a significant crop in these areas, particularly during summer and rainy seasons [2]. A pot trial was established in the greenhouse following a completely randomized design (CRD) with ten treatments, each replicated four times, resulting in forty pots. Observations were recorded from all plants, and mean values per pot were used for statistical analysis, with each pot considered an independent experimental unit. Across two years, this design yielded a total of 80 plants. Each pot (25 cm diameter × 26 cm height) had a soil-holding capacity of 10 kg, and one uniform okra plant was maintained per pot to avoid intra-specific competition. Standard agronomic practices were adopted, and uniform management practices, including irrigation to maintain optimum soil moisture and pest control as required, were applied across treatments. The study utilized various fertilizers and organic supplements, including microbially-assisted TLL vermicompost, cow dung manure, and inorganic NPK (100:60:45 kg/ha). Urea (RCF, India), SSP (RCF, India), and MOP (RCF, India) were utilized as supplements for NPK. Organic supplements were applied before transplanting, while synthetic fertilizers were applied at transplanting. The properties of the different TLL composts are reported in Table S6. The study measured vital agronomic parameters, including fruit characteristics, plant growth, and yield components, to evaluate the efficacy of microbe-enriched TLL vermicompost on okra’s yield. Agronomic parameters were measured from randomly selected plants, and fruit yields were calculated. Standard farming practices, including watering, drainage, weeding, and pest control, were consistently adopted across all treatments as per the guidelines of the Jharkhand Government’s Department of Agriculture.

2.3. Soil Sampling

Four different stages of pot moist soil samples from okra plantation (0-, 30-, 60-, and post-harvest) were collected to estimate the microbial parameters, including microbial biomass carbon, respiration, and other enzymatic properties. Soil samples were collected at two stages: pre-transplanting and post-harvest, and stored in sterile bags, maintaining all aseptic conditions.

2.3.1. Analysis of Physico-Chemical Parameters of Soil

Soil pH, organic carbon (OC), available nitrogen (Avl N), available phosphorus (Avl P), and available potassium (Avl K) were analyzed, along with nutrient content in cow dung and vermicompost. Air-dried soil samples (0 day and post-harvest) were used to assess physicochemical properties. pH (H2O) was analyzed in a digital pH meter (Systronics 335, Ahmedabad, India) [19]. Organic carbon was enumerated according to the standard protocol of Walkey & Black [20]. Available phosphorus was measured using Olsen’s reagent, stannous chloride, and ammonium molybdate reagent with standard protocol, and available nitrogen was assessed by alkaline potassium permanganate solution utilizing the Kjeldahl apparatus [21]. Okra’s agronomic performance was also estimated at harvest.

2.3.2. Microbial Analysis of Soil

Microbial biomass carbon of the different stages of the soil sample was evaluated by adopting the chloroform fumigation method as established previously by Joergensen et al. [22]. Microbial respiration, including both basal level and substrate-level, was estimated by trapping CO2 in NaOH solution [23]. β-D-glucosidase activity, dehydrogenase, and alkaline phosphatase activity were evaluated by using the protocol obtained by Tabatabai [24]. Fluorescein diacetate (FDA) hydrolysis activity in soil was enumerated using the established protocol of Schnurer and Rosswall [25].

2.4. Estimation of PHMs Content in Different Parts of Plants and Bioavailable Forms in Soils

Air-dried soil samples were used to analyze the bioavailable forms of PHMs using DTPA-extractant, following established methodology [17]. PHM concentration in different plant parts (root, shoot, and fruit) was evaluated by digesting them in a mixture of HNO3:HClO4 acid. PHMs (Cr, Ni, Pb, and Cu) concentrations were analyzed using atomic absorption spectrophotometry. Stock solutions of PHM (100 mg/L) of PHMs were used for calibration purposes, Merck-grade standards were used for calibration, and quality control measures included blank extracts and certified reference materials (Table S5).

2.5. Evaluation of Mobility Assessment of PHMs

The mobility assessment of PHMs and their possible transfer into plant systems was carried out and quantified using bioconcentration factors (BCF), bioaccumulation factors (BAF), and translocation factors (TF), as outlined by [26]. The corresponding formulas for these factors are presented below.

2.6. Prediction Models Design for PHM Uptake in Okra Plant (FIAM)

The FIAM model is a widely adopted theoretical framework used in environmental chemistry and ecotoxicological studies on the basis of free metal ions activity rather than their total concentration. This model is a more reliable predictor of metal uptake and the associated biological effects of the metals in living organisms. The core principle of FIAM is that biological responses are directly linked to free ion activity, which governs the binding of metal ions at cell surfaces or biological membranes. The FIAM model was employed to predict the accumulation of PHMs in tea plants cultivated in TLL-containing soil. The model incorporates the pH-sensitive Freundlich equation, which determines PHM concentrations by relating the activity of PHM ions in the soil (Mn−) to their transfer from soil to plant, represented by the transfer factor (TF) [27].

In this equation, Mn+ refers to the concentration of PHMs in the okra. Only the bioavailable forms of PHMs were considered when evaluating their uptake by the okra plant. Additionally, the potential health risks associated with consuming okra grown in a leaf litter containing soil were assessed using the FIAM-based hazard quotient (FIAM-HQ), following the procedures outlined by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). However, the application of the FIAM model in pot experiments has certain limitations. Pot trial experiments are carried out under highly controlled conditions, and therefore, predictions might not fully account for in-field variability in the case of soil pH, redox potential, and organic carbon content. These three aforementioned parameters significantly influence metal ion activity. Additionally, constraints imposed by the root environment and altered nutrient dynamics in pots may affect metal availability. Despite these limitations, FIAM has been successfully applied in pot studies, as reported by [5,28].

2.7. Evaluation of Biochemical Content of Okra Fruit

The biochemical traits of okra fruits were monitored. The chlorophyll content was analyzed following established protocols [29]. Total sugar was estimated using the anthrone method. Total phenolic content was determined by mixing 100 µL of the supernatant with Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, and the absorbance was measured at 750 nm using a spectrophotometer [30]. Ascorbic acid levels were determined through a standard titrimetric method using starch as an indicator.

2.8. Determination of Health Hazards Using Fuzzy-TOPSIS

The TOPSIS (Technique for Ordering Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution) method is a multi-criteria decision-making approach that ranks alternatives based on their similarity to ideal solutions. The “alternatives” (treatments) and “criteria” (agronomic traits of the okra plant) were established for different treatments. Firstly, a decision matrix was made involving agronomic traits like fruit yield, number of okras per plant, shoot length, root length, and shoot–root height for each treatment. Subjectivity was avoided by assigning importance to criteria, and entropy weighting was applied to calculate objective weights based on the variability of each agronomic input across treatments. The decision matrix was then normalized and multiplied by the corresponding entropy-derived weights to obtain a weighted normalized matrix. Fuzzy TOPSIS uses entropy to determine the best (Si+) and worst (Si−) solutions and has been widely applied in decision-making, including fertilizer selection in the agronomy sector [31]. Finally, a performance (closeness) coefficient (Pi) was computed for each treatment, indicating its relative proximity to the ideal worst condition. Treatments were ranked based on Pi values, with higher scores indicating the best treatment. In this research, TOPSIS was employed to rank treatments based on their agronomic attributes, with Fuzzy-TOPSIS calculations following equations proposed [14]. While Fuzzy-TOPSIS is widely applied for comparative evaluation under multi-criteria conditions, several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting its outcomes. The method is inherently sensitive to the quality and completeness of input data, such that measurement uncertainties or the exclusion of relevant indicators may substantially influence the final ranking [32]. Furthermore, Fuzzy-TOPSIS is primarily a ranking-based decision support tool and does not elucidate causal or mechanistic relationships among variables, thereby limiting its capacity to explain underlying environmental processes. In addition, the use of entropy-based weighting, although effective in reducing subjectivity, tends to assign greater importance to criteria with higher variability, which may not always correspond to their actual ecological or toxicological significance.

2.9. Predicting the Influence of Biochemical Properties on the Yield of Okra

Sobol sensitivity indices were used to determine which input parameters most strongly influenced variations in the model output and to quantify their relative contributions to overall uncertainty. These sensitivity indices (SIs) represent the proportion of total output variance that can be attributed to individual input variables and their interactions. The primary Sobol sensitivity indices include the first-order sensitivity index (FOSI), which reflects the impact of a single input variable on the model’s output, followed by the second-order sensitivity index (SOSI), which accounts for interactions between two input variables. The first-order sensitivity index (FOSI) describes the direct effect of a single input parameter on the model output by measuring the variance explained when that parameter is varied alone, while all other inputs are kept constant. In contrast, the second-order sensitivity index (SOSI) reflects the interaction effects between pairs of input parameters. Total-order sensitivity index (TOSI) captures the overall contribution of a variable, including both individual and interactive effects of input variables, which are classified as highly sensitive (>0.1), sensitive (0.01–0.1), or insensitive (<0.01) based on their sensitivity indices [33]. In this study, Sobol sensitivity analysis (SSA) was applied to explore how biochemical parameters affect agronomical traits. The analysis focused on the first-order and total-order sensitivity indices (FOSI and TOSI), which together provide a comprehensive view of individual parameter effects as well as their combined influence through interactions. Although SSA is a powerful tool for assessing global parameter importance, its application in environmental research is subject to several limitations, including high computational requirements, assumptions of parameter independence, limited capacity to address correlated and dynamic systems, and challenges in interpreting complex interaction effects.

2.10. Evaluation of Agronomic Traits of Okra Plant

Agronomic traits of the okra plants, including fruit yield, number of okras per plant, shoot length, root length, shoot–root, and height, were measured at the time of harvest. All the data were recorded according to the protocol described by Sarkar et al. [5].

2.11. Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA and ANOVA with repeated measures, post hoc analysis [Tukey’s HSD (Honestly Significant Difference)], were carried out using SPSS software (version 7.5) to compare between variables. Sobol sensitivity analysis was performed in Python software. Other statistical tests, like the Pearson correlation plot and principal component analysis, were performed using R Studio (version 4.3.2).

3. Results

3.1. Variation in Soil Physicochemical Attributes over Different Treatments

The gradual changes in soil physico-chemical properties across different treatments (0-day soil and post-harvest soil) are illustrated in Table S1. At 0 days, the initial soil pH was slightly acidic in nature (6.09 ± 0.42–6.38 ± 0.27). The lowest pH of 6.09 was observed in the T1 treatment at 0 days. Application of leaf litter vermicompost in treatment T1 exhibited a slightly acidic range. An upsurge in pH (6.69 ± 0.68–7.21 ± 0.67) has been reflected in all the treatments in the post-harvest soil. Treatments T3, T4, T5, T6, and T7 showed a perfect neural pH range. These findings are in accordance with [7]. The EC levels exhibited the same trend as pH. EC levels were particularly high in compost and manure mixed soils. A temporal increase in total organic carbon content was observed amongst all treatments at post-harvest soil. All these data were found to be statistically significant at a p < 0.05 significance level. Furthermore, three important macronutrients Avl. N, Avl. K, and Avl. P content was also increased at the post-harvest stage. Treatment T5 (bacterial consortium enriched vermicompost amended soil) recorded the highest macronutrient availability (Avl N: 29.37 ± 1.67 mg/kg, Avl P: 73.59 ± 6.28, Avl K: 193.43 ± 15.25), followed by treatment T8, T4, and T9, respectively.

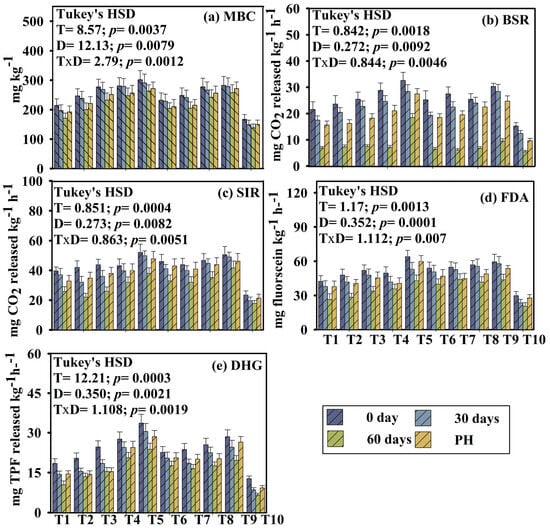

3.2. Treatment-Wise Temporal Variation of Microbial Enzymes over Different Time Periods

In this research, different microbial parameters, i.e., microbial biomass carbon (MBC), respiration (both BSR and SIR level), fluorescein di-acetate (FDA), and dehydrogenase activity (DHG), were evaluated over different time periods (0, 30, 60, and post-harvest) across different treatments. Temporal dynamics of microbial parameters significantly varied (Figure 1). A two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant effects of treatment on soil microbial activity across different time points. The magnitude of increase varied among treatments. At day 0, all microbial parameters appeared to flourish, followed by a significant and gradual decline up to 60 days. A slight increase was observed in post-harvest soils. Enzyme activity was consistently higher in soils under treatment T5 (microbial consortium-enriched vermicompost), T8 (consortium-enriched aerobic compost), and T9 (100% fertilizer) compared to T1 (TLL) and T10 (control). All data were statistically significant (p < 0.05), indicating a clear time-dependent treatment response. Repeated measures ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was performed on the temporal microbial data. For all tested parameters (MBC, BSR, SIR, FDA, DHG), Mauchly’s test of sphericity was violated (p < 0.05). Therefore, Greenhouse–Geisser corrections were applied. The adjusted degrees of freedom, p-values, and F-values are presented in the Supplementary Table. Both within-subject and between-subject effects are also reported in the Supplementary Material (Tables S7 and S8).

Figure 1.

Variation of microbial parameters of different treatments during the pot experiment with okra as the test crop. Here, T1: TLL+ CD; T2: TLL+ CD + Earth worm (Eisenia fetida); T3: TLL+ CD + Earth worm + B1; T4: TLL+ CD + Earth worm + B2; T5: TLL+ CD + Earth worm + B1 + B2; T6: TLL+ CD + B1; T7: TLL+ CD + B2; T8: TLL+ CD + B1 + B2; T9: NPK fertilizer (100%); T10: Control soil. HSD: Honestly Significance Difference at 5% level and T: Treatment, D: Day, PH: Post-harvest. (a) MBC: Microbial Biomass Carbon, (b) BSR: Basal Soil Respiration, (c) SIR: Substrate Induced Respiration, (d) FDA: Fluorescein Di-acetate, (e) DHG: Dehydrogenase (Error bar denotes standard deviation).

Microbial biomass carbon (MBC) reflects the activity of the total soil microbiota, whereas soil respiration (BSR and SIR) reflects the metabolically active microbial population. In the experiment, MBC, BSR, and SIR significantly varied amongst all the treatments and subsequently declined up to 60 days. At the post-harvest stage, a striking increment has been observed in all the parameters. Treatment T5 followed by T8 exhibited highest MBC activity (T5_0D: 302.64 ± 22.63; T5_30D: 291.73 ± 18.94; T5_60D: 264.37 ± 20.82; T5_post-harvest: 272.62 ± 18.38). Addition of biofortified vermicomposted leaf litter along with organic manure might have enhanced soil MBC (p = 0.0037; HSD_T = 8.57) compared to synthetic fertilizer and control (Figure 1). However, BSR and SIR also exhibited the same trend. The highest respiration rate has been observed in treatments T5, T9, T8, and T4, whereas the lowest respiration rates have been recorded in treatments T10 and T1. These results are in line with the findings of [32]. Fluorescein di-acetate (FDA) and dehydrogenase (DHG) enzyme activity were highest at 0 days, then followed by a gradual decline up to 60 days, and then a slight increase in enzyme activity was recorded at the post-harvest stage across the treatments. Treatments T1 (TLL amended soil) and T10 (control) soil consistently recorded the lowest enzyme activity and other microbial parameters.

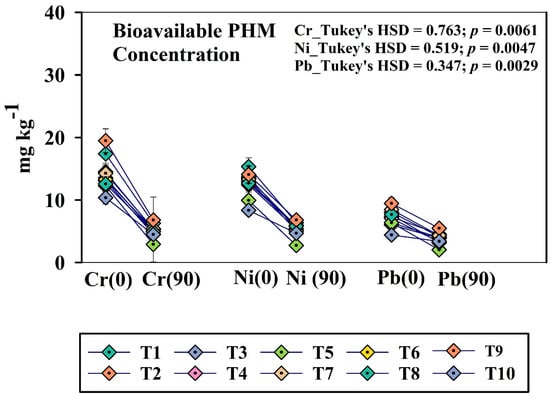

3.3. Periodic Variation in Bioavailability of PHMs Across the Treatments

The bioavailable fraction of PHMs is a vital parameter, as it indicates the amount of PHM that is available for plant uptake [17]. DTPA extractable bioavailable fraction of PHMs was taken into account for this research work, and the fraction varied significantly across the treatments (Figure 2). In the initial days, the bioavailable concentration of Cr, Ni, and Pb was comparatively high in the soil. The concentration declined sharply and came to a minimum at the post-harvest stage. Initially, the highest concentration of Cr, Ni, and Pb was reflected in treatment T1 and T9 on zero day (T1 DTPA-Cr_0D:17.39 ± 1.63; T9 DTPA-Cr_0D:19.48 ± 1.70; T1 DTPA-Ni_0D:15.34 ± 1.47; T9 DTPA-Ni_0D: 14.06 ± 1.24; T1 DTPA-Pb_0D: 7.29 ± 0.53; T9 DTPA-Pb_0D:9.46 ± 0.74. All these results were statistically significant at a significance level of p < 0.05. In contrast, treatment T5 and T8 exhibited the most significant reduction in Cr, Ni, and Pb content at the post-harvest stage at p < 0.05 (T5_DTPA Cr_0D: 12.26 ± 1.1; T5-DTPA-Cr_90D: 2.91 ± 0.82; T8_ DTPA Cr_0D: 12.57 ± 1.2; T8-DTPA-Cr_90D: 4.95 ± 0.48).

Figure 2.

Periodic change (0 day and post-harvest) of bioavailable PHMs (Cr, Ni, and Pb) among the treatments. Here, T1: TLL+ CD; T2: TLL+ CD + Earth worm (Eisenia fetida); T3: TLL+ CD + Earth worm + B1; T4: TLL+ CD + Earth worm + B2; T5: TLL+ CD + Earth worm + B1 + B2; T6: TLL+ CD + B1; T7: TLL+ CD + B2; T8: TLL+ CD + B1 + B2; T9: NPK fertilizer (100%); T10: Control soil. HSD: Honestly Significance Difference at 5% level, T: Treatment, and PH: Post-harvest (Error bar denotes standard deviation).

Strikingly, the bioavailable micronutrient content seems to be upregulated at the post-harvest stage. An upsurge in bioavailable Cu and Zn content has been reflected in post-harvest soil compared to 0-day soil. Treatment T5 recorded the highest bioavailable Cu and Zn content (DTPA_Cu_Post-harvest: 29.58 ± 2.43, DTPA_Zn_Post-harvest: 42.67 ± 3.39) followed by T8, and T9 (Table S1). Both microbially-enriched aerobic compost (T8) and vermicompost (T5) significantly reduced the bioavailable concentrations of PHMs such as Cr, Ni, and Pb. Interestingly, these amendments simultaneously increased the bioavailable fractions of essential micronutrients, particularly Cu and Zn.

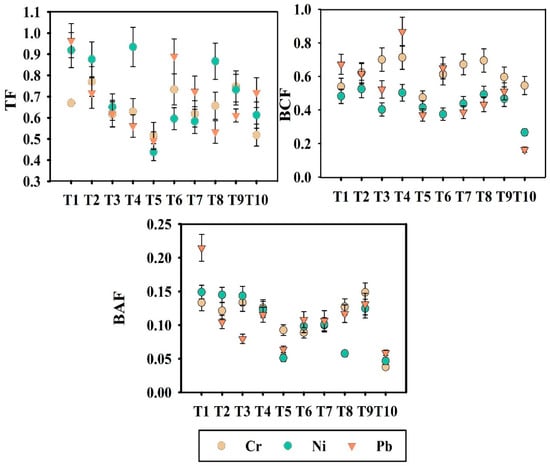

3.4. Determination of Soil to Plant Translocation Patterns of Okra Through Several Indices and Determination of Risk Factor by Model-Based Analysis

Evaluating the translocation patterns of PHMs from soil to plants and subsequently into the crop is vital, as their accumulation in edible parts of the plant can facilitate entry of the PHMs into the food chain and pose significant health risks. The uptake and translocation pattern of PHMs from soil to okra plant was estimated through some vital indices such as translocation factor (TF), bioconcentration factor (BCF), and bioaccumulation factor (BAF), represented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Variation of TF (Translocation Factor), BCF (Bioconcentration Factor), and BAF (Bioaccumulation Factor) across different treatments. Here, T1: TLL+ CD; T2: TLL+ CD + Earth worm (Eisenia fetida); T3: TLL+ CD + Earth worm + B1; T4: TLL+ CD + Earth worm + B2; T5: TLL+ CD + Earth worm + B1 + B2; T6: TLL+ CD + B1; T7: TLL+ CD + B2; T8: TLL+ CD + B1 + B2; T9: NPK fertilizer (100%); T10: Control soil.

Translocation factor (TF) is determined by the ratio of root to shoot transfer of PHMs, while the uptake of PHMs from soil to root is represented by the bioconcentration factor (BCF). Bioaccumulation factor (BAF) is the ratio of PHMs content of grain to PHMs content of soil. The lowest TF values for individual treatment were reflected in treatment T5 (TFCr = 0.61, TFNi = 0.43, TFPb = 0.49), T3 (TFCr = 0.61, TFNi = 0.65, TFPb = 0.62), and T8 (TFCr = 0.65, TFNi = 0.86, TFPb = 0.53). TF values less than 1 denoted restricted translocation of PHMs. The highest TF values were recorded for treatment T1 (TFNi = 0.91, TFPb = 0.96), highlighting the direct effect of the application of PHM containing leaf litter. The BCF value estimated the PHM accumulation in the root section. The BCF and BAF values for Cr, Ni, and Pb were consistently lower than 1 in all the treatments. For Cr and Ni, the lowest BAF values were recorded in treatment T5 (BAFCr = 0.092, BAFNi = 0.051). In our study, TF, BCF, and BAF values were all below 1, which is generally used as a reference threshold in environmental contamination and phytoremediation literature to indicate limited bioaccumulation and translocation of PHMs. Among the evaluated treatments, the microbial consortium-assisted vermicompost (T5) exhibited the lowest values, thereby demonstrating its superior efficacy in mitigating potential risks. Additionally, to validate the efficacy of vermicompost in mitigating PHM-related health hazards, model-based approaches were employed. Specifically, the Free Ion Activity Model (FIAM) was applied to assess potential risks associated with PHM risk. The FIAM hazard quotient (FIAM-HQ) and the prediction coefficient C, β1, and β2 values are illustrated in Table S2. The FIAM model was successfully appointed based on bioavailable PHM content, soil pH, and total organic carbon content. Treatments T5, T8, and T9 were selected for FIAM-based analysis. A FIAM-HQ value < 0.5 was observed for treatments T5 and T8 in the case of Cr, Ni, and Pb, except for treatment T9. Minimal FIAM-HQ values were observed in treatment T5 (Cr = 0.03, Ni = 0.02, Pb = 0.17). Amongst the three treatments, the highest FIAM-HQ values were reflected in treatment T9 (Cr = 0.11, Ni = 0.09, Pb = 0.57). In the case of Pb, treatment T9 (chemical fertilizer-treated soil) slightly exceeded the threshold value of 0.5.

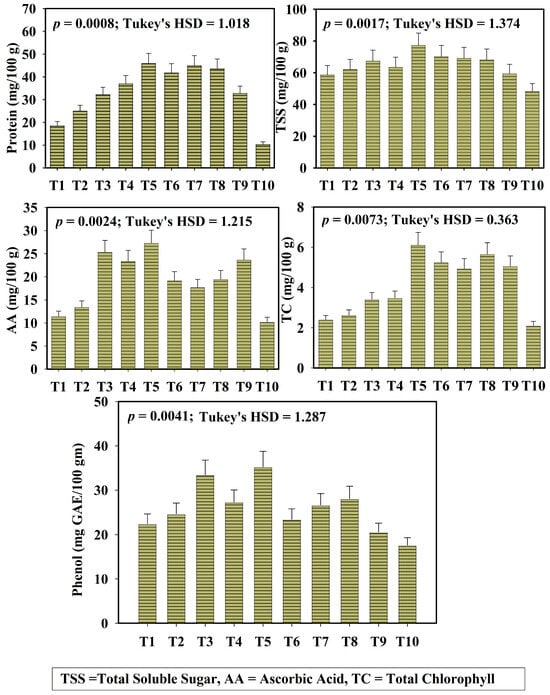

3.5. Comparison Between Different Biochemical Traits of Okra Across Different Treatments

Different biochemical parameters of okra, total chlorophyll content (TC), total soluble sugar (TSS), total phenol content (TP), protein content (Pro), and ascorbic acid (AA) were assessed across all treatments and are illustrated in Figure 4. Total chlorophyll (TC) content of okra fruit was significantly higher in treatments T5 and T8, followed by T9. Treatment T5 recorded the highest TC content of 6.12 ± 0.53 mg/100 g FW, whereas the TC content of the synthetic fertilizer-treated input was 5.07 ± 0.36 mg/100 g FW. Similarly ascorbic acid (AA) and total soluble sugar (TSS) content in okra fruit was maximum in T5 (TSS = 77.29 ± 6.40 mg/100 g FW), T8 (TSS = 68.23 ± 4.77 mg/100 g FW), and T9 (TSS = 59.42 ± 4.04 mg/100 g FW) reflecting the influence of microbe-assisted leaf litter vermicompost on biochemical quality of okra (HSD_AA = 1.215; HSD_TSS = 1.37). Amongst these parameters, treatment T10 (control soil) and T1 (only leaf litter) express the lowest activity of TC, TSS, and AA content.

Figure 4.

Variation of biochemical parameters of okra fruit across different treatments (protein, TSS, AA, TC, Phenol). Here, T1: TLL+ CD; T2: TLL+ CD + Earth worm (Eisenia fetida); T3: TLL+ CD + Earth worm + B1; T4: TLL+ CD + Earth worm + B2; T5: TLL+ CD + Earth worm + B1 + B2; T6: TLL+ CD + B1; T7: TLL+ CD + B2; T8: TLL+ CD + B1 + B2; T9: NPK fertilizer (100%); T10: Control soil. HSD: Honestly Significance Difference at 5% level and T: Treatment (Error bar denotes standard deviation).

The total phenol content of okra varied significantly across the treatments. The highest phenol content was recorded in treatment T5 (35.27 ± 2.91 mg GAE/100 g), T3 (33.48 ± 3.02 mg GAE/100 g), and T8 (28.09 ± 1.61 mg GAE/100 g).

3.6. Evaluation of Different Agronomical Traits of Okra Across Different Treatments and Prediction of the Best Treatment Through Fuzzy-TOPSIS Analysis

Several agronomical traits like shoot length (SH), root length (RL), number of okra/plant (NOP), and yield/plant were assessed and represented in Table S3. The aforementioned agronomical attributes seem to flourish in treatment no. T5, followed by T9 and T8. The yield was significantly higher in T5 and T8 compared to control soil (T10) and synthetic fertilizer-treated soil (T9). Treatment T5 (bacterial consortium-enriched vermicompost-amended soil) exhibited a 1.22-fold increase in yield compared to the synthetic fertilizer-treated soil. The number of okra/plant (NOP) was highest in treatment T5 (NOP = 33 ± 2.37), followed by T8, T7, and T4, compared to the chemical fertilizer-treated soil. Fuzzy-TOPSIS analysis was further employed in the study to select the best treatments for the aforementioned agronomical attributes. Various alternatives, “Treatments,” were taken into account based on the criteria of SH, RL, NOP, and yield. The best and worst values, along with the associated parameters, are represented in Table S4. The treatment was ranked as T5 > T8 > T9 > T6 > T7 > T4 > T3 > T2 > T10 > T1 on the basis of agronomical parameters. The Pi values for treatment T5, T8, and T9 were 0.86, 0.75, and 0.72, respectively. Amongst 10 different treatments, treatment T5 emerged as the best treatment, followed by T8 and T9, on the basis of multiple agronomical parameters. The lowest Pi values were observed for treatments T10 and T1. Through the model-based analysis, the microbe-assisted TLL vermicompost treatment (T5) turned out to be the best treatment when compared to 100% synthetic fertilizer input (T9). Application of the Fuzzy TOPSIS method for the selection of the best treatment based on agronomical parameters is novel, as prior studies such as [31] have primarily employed this method for fertilizer selection.

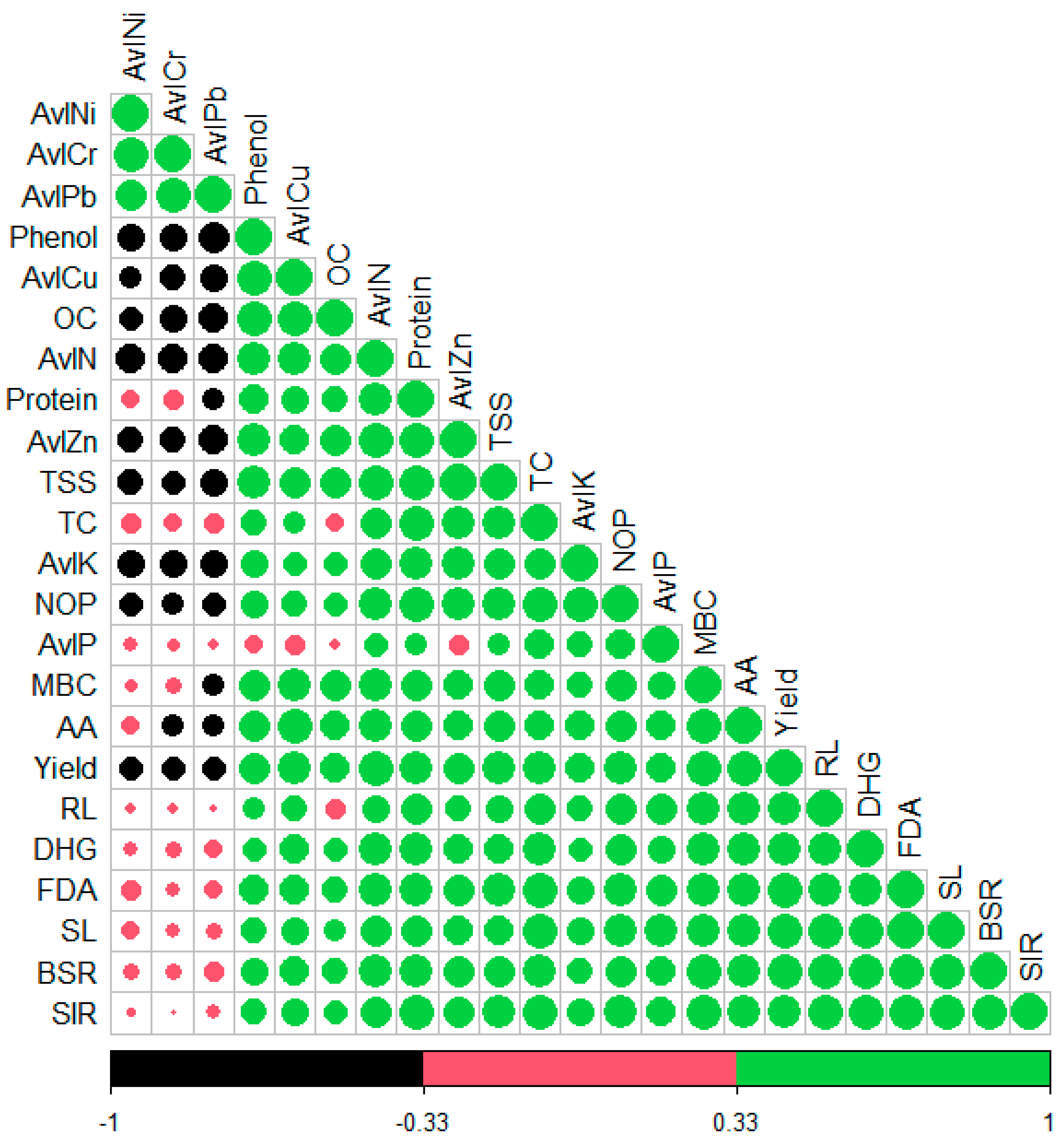

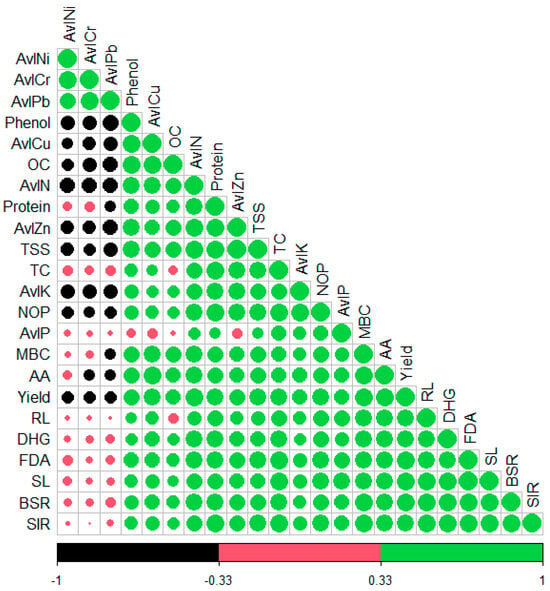

3.7. Evaluating the Interrelationship Between Microbial, Biochemical, Agronomical Parameters and Bioavailable Micro and Macronutrient Content Through Correlation Analysis

A simple Pearson correlation analysis was performed to assess the correlation between microbial, biochemical, and agronomical parameters of okra and bioavailable micro and macronutrients (Figure 5). All the microbial parameters exhibited a strong positive correlation with available macronutrient and micronutrient content, but showed a negative correlation with the bioavailable PHM (Cr, Ni, and Pb) [MBC (rAvl Cu = 0.809; rAvlZn = 0.675; rOC = 0.692; rAvl N = 0.781, rAvl P = 0.57; rAvl K = 0.47; rAvl Cr = −0.22, rAvl Ni = −0.108, rAvl Pb = −0.35]. Likewise, MBC, the other microbial parameters (FDA, DHG, BSR, and SIR) also reflected the same pattern. The biochemical parameters also showed a strong positive correlation with the microbial parameters, available macro (Avl N, Avl K, Avl P) and micronutrient (Avl Cu, Avl Zn). [TSS (rMBC = 0.69; rFDA = 0.80; rDHG = 0.64; rBSR = 0.73; rSIR = 0.78; r Avl Cu = 0.71; Avl K = 0.71; Avl N = 0.89, rOC = 0.71; rAvl Zn = 0.96; rAvl Cr = −0. 42; rAvl Ni = −0.46; rAvl Pb = −0.53]. Phenol content exhibited a strong negative correlation with Bioavailable PHM content [Phenol (rAvl Cr = −0.60, rAvl Ni = −0.53, rAvl Pb = −0.69)]. Ultimately, yield/plant poses a strong positive correlation with microbial parameters (rMBC = 0.91; rFDA = 0.90; rBSR = 0.91; rSIR = 0.844), available macronutrient and micronutrient content (rAvl Cu = 0.78; rAvl Zn = 0.75; rAvl N = 0.88; rAvl P = 0.65; rAvl K = 0.67; OC = 0.64), and biochemical parameters (rTSS = 0.77, rProtein = 0.79; rAA = 0.93; rTC = 0.79; rPhenol = 0.769). Strikingly, yield/plant reflected a strong negative correlation with available PHM (AvlCr = −0.40; Avl Ni = −0.40; Avl Pb = −0.44).

Figure 5.

Correlation plot describing the association between available macro and micronutrients of soil, microbial parameters of soil, and biochemical and agronomical attributes of okra.

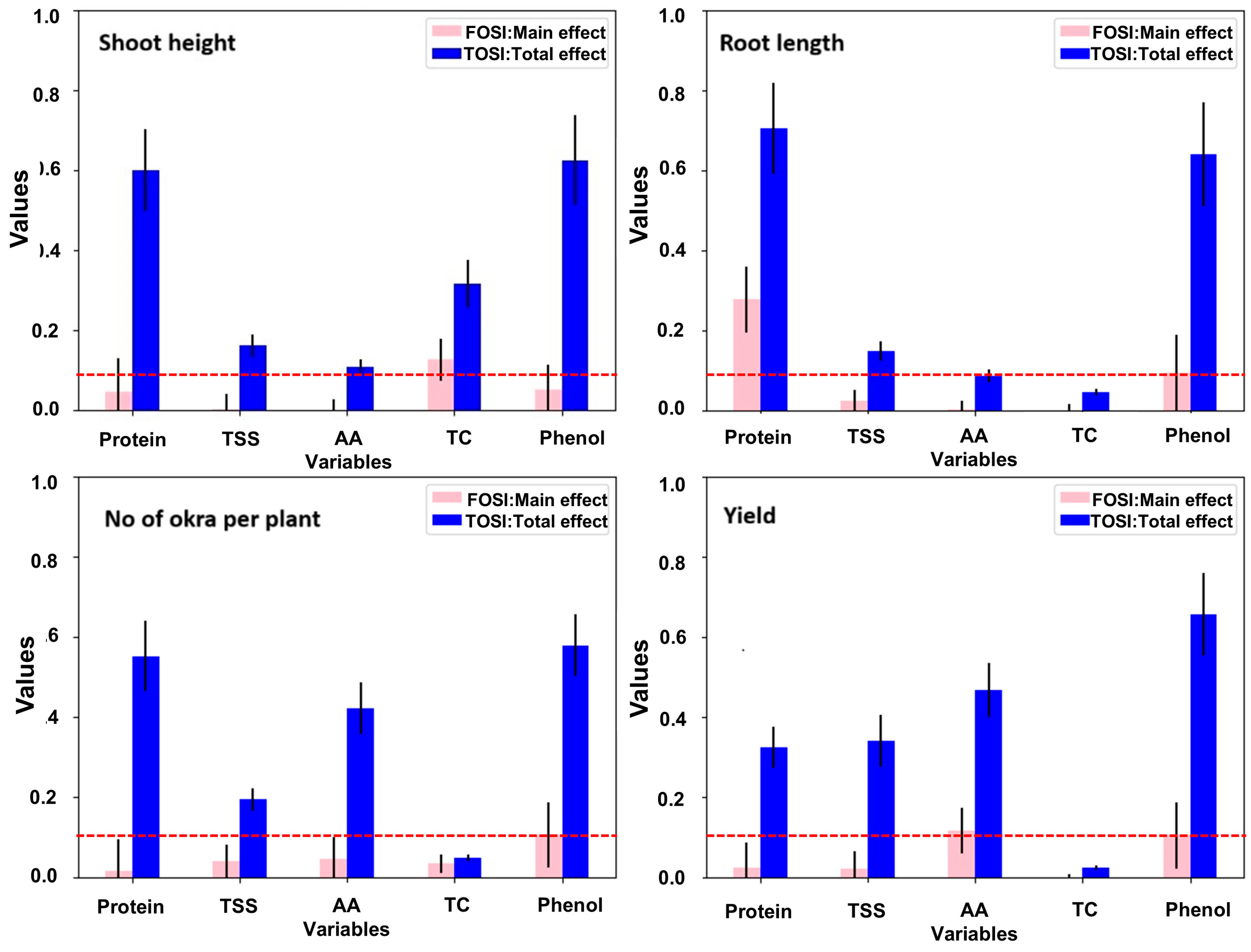

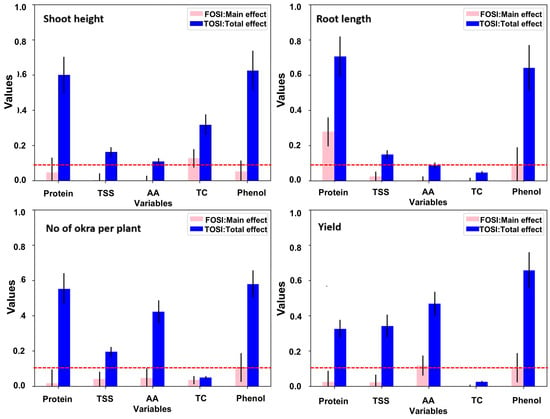

3.8. Predicting the Influence of Biochemical Parameters on Agronomical Traits of Okra Through Sobol Sensitivity Analysis

In this research, Sobol sensitivity analysis (SSA) was employed to predict the effect of biochemical parameters (Protein, TSS, AA, TC, and Phenol) on agronomical traits (SH: Shoot Height; RL: Root Length; NOP: No of okra/plant; Yield). The outcomes resulted in two sensitivity indices, namely the total-order sensitivity index (TOSI) and the first-order sensitivity index (FOSI). The TOSI and FOSI values for different agronomic parameters on okra, together with their influence on biochemical traits, are depicted in Figure 6. Among the biochemical parameters, phenol, AA, and protein content exhibited the highest sensitivity on yield and no of okra/plant (TOSI > 0.1). Similarly, protein, phenol, and TC imparted a higher sensitivity on the SH of okra.

Figure 6.

Influence prediction of biochemical parameters (protein, TSS, AA, TC, phenol) on agronomic attributes (shoot height, root length, no of okra per plant, yield) of okra through SOBOL sensitivity analysis.

4. Discussion

Maintenance of soil health through balanced physicochemical and microbial properties is crucial for sustainable crop production. In this research, the efficacy of microbe-assisted vermicompost and aerobic composted TLL on nutrient dynamics of soil, plant growth, and potential health risks associated with PHMs was comprehensively evaluated in okra. Soil pH is a crucial determinant of nutrient availability and plant metabolic efficiency. Supplementation of microbe-assisted vermicompost resulted in a substantial increase in post-harvest soil pH, thereby fostering a more conducive environment for nutrient uptake and root activity. Additionally, soil amended with compost and cow dung exhibited comparatively higher EC, which might be due to the release and accumulation of soluble salts during organic matter mineralization. A steady increase in TOC was observed across all treatments at the post-harvest stage, likely due to the decomposition of crop residues and the addition of organic amendments. This finding aligns with earlier reports indicating that carbon derived from plant residues interacts with clay particles to form stable soil aggregates, thereby enhancing humification and promoting long-term carbon stabilization [34]. Moreover, post-harvest soils exhibited improved bioavailability of essential macronutrients, particularly Avl N, Avl P, and Avl K across all the treatments, particularly in the microbe-assisted vermicompost treatment. Although soils may inherently contain substantial reserves of phosphorus and potassium, these elements often persist in insoluble forms; organic amendments, especially those enriched with microbial activity, play a pivotal role in their solubilization and subsequent uptake by plants.

TLL contains lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose, of which lignin is particularly resistant to microbial degradation. To achieve rapid lignocellulosic decomposition of leaf litter biomass, the TLL vermicompost was enriched with a ligninolytic bacterium and a lignocellulolytic bacterium, both of which also function as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR). This value-added vermicompost not only enhances soil fertility but also contributes to the mitigation of PHMs immobilization. The better performance of microbe-assisted vermicompost compared to aerobic compost sheds light on the fact that the abundance of beneficial microorganisms might have facilitated atmospheric nitrogen fixation and the P and K solubilization process. In earlier findings of Sahni et al. (2008) [35], it was stated that diverse PGPRs present in vermicompost likely contributed to enhanced nutrient availability through the production of phytohormones (indole acetic acid, gibberellic acid, cytokinin), ammonia, and siderophores. Additionally, the organic amendments, i.e., microbe-assisted vermicompost and aerobic compost, appear to optimize mineral distribution and soil enzymatic activity, which in turn escalates the release of various exogenous and endogenous enzymes in soil, thereby boosting soil fertility [35].

Soil microbial activity and organic carbon dynamics are intricately linked with soil health. Microorganisms-driven organic matter decomposition, nutrient cycling, and stable humic substances formation contribute to long-term carbon sequestration [36]. In our research, MBC, BSR, and SIR varied significantly across treatments. Although these parameters declined up to 60 days, a marked increase was observed at the post-harvest stage. Supplementation of microbe-assisted vermicomposted TLL has reflected an upsurge in MBC value compared to soils treated with only synthetic fertilizers, which typically lack a sufficient carbon source for the survival of a diverse microbial plethora [37]. Additionally, residual root biomass most likely served as an additional carbon source, supporting microbial activity in post-harvest soil [38]. BSR and SIR provided valuable insights regarding the functional responses of the soil microbial plethora. SIR depicts the activity of fast-growing, substrate-responsive r-strategist microbes, while BSR reflects steady and metabolically active k-strategist microorganisms [39]. Enzymatic activities such as FDA hydrolysis and DHG activity were higher in organically amended soils, pinpointing flourishing microbial metabolic potential. In contrast, lower microbial activity in raw TLL amended soils is most likely due to the presence of PHMs, which might hinder soil enzymatic activity [38,40,41]. Organic amendments, particularly microbe-assisted vermicompost and aerobic compost, effectively boosted microbial enzyme production and activity among all the treatments.

PHMs like Cr, Ni, and Pb pose considerable ecological and health hazards when found in bioavailable forms [17]. This research indicates that both microbe-assisted aerobic compost and vermicompost markedly decreased the bioavailable fractions of Cr, Ni, and Pb, while concurrently increasing the bioavailability of essential micronutrients such as Cu and zinc [42]. This event underscored an additional positive aspect of organic amendments supplementation for immobilizing PHMs, thereby fostering robust okra growth. Flourished microbial activity likely facilitated PHM immobilization through chelation, redox transformations, and organic matter complexation and organic acid secretion. The translocation of PHMs from soil to plant tissues was evaluated using indices such as the TF, BCF, and BAF. Rhizosphere chemistry, encompassing pH and organic matter content, accelerates PHM mobility. Additionally, absorption capacity and root selectivity also impact the soil-to-plant translocation of PHMs [43]. The indices-based result efficiently portrayed the retention of Cr, Pb, and Ni in plant roots, which indicates the effective sequestration of PHMs within root cell vacuoles and limited xylem transport, thereby restricting their accumulation in above-ground tissues [44]. This reduced mobility alleviated metal-induced toxicity stress and efficiently contributed to robust plant growth. Rhizosphere chemistry, including pH and organic matter content, further accelerates PHM mobility. Additionally, absorption capacity and root selectivity also impact the soil-to-plant translocation of PHMs [43]. Notably, okra consumption posed negligible health risks under all treatments, with the microbial-assisted vermicompost exhibiting the lowest PHM-related risk indices. These findings were further corroborated using the Free Ion Activity Model (FIAM), a slightly increased value of FIAM-HQ for Pb in treatment T9 pinpoints the risk associated with consumption of chemical fertilizer-treated crops. In contrast, this model also confirmed that okra grown under microbe-assisted vermicompost and compost treatments is safe for consumption.

In this study, it has been observed that organic amendments significantly influenced the biochemical quality of okra fruits. Total chlorophyll content, total soluble sugars, ascorbic acid, protein, and total phenolic content were reportedly higher in plants grown with microbe-assisted vermicompost and aerobic compost. Increased levels of organic acid and carbohydrate content under the influence of organic amendment conditions are consistent with earlier reports [45,46,47]. Lower chlorophyll content in the control treatment may be attributed to PHM-induced disruption of chloroplast structure and nutrient deficiency, leading to impaired photosynthesis [48]. Improved nitrogen availability under the influence of both organic and inorganic amendments results in higher protein synthesis, corroborating previous studies [49]. Application of vermicompost, particularly the microbe-assisted one, significantly increased total phenolic content, which is associated with improved antioxidant capacity and plant defense mechanisms. Phenolic compounds have a vital role in maintaining cell wall integrity and nutrient uptake regulation, thus confer resistance against plant pathogens and pests [50]. Similarly, higher chlorophyll content is associated with enhanced photosynthetic efficiency, glucose production, and ultimately promotes shoot elongation and crop yield. SOBOL sensitivity analysis further confirmed the strong influence of protein, phenol, and chlorophyll content on agronomic traits such as shoot height and yield. The microbe-assisted TLL vermicompost offers a balanced soil macro and micronutrient profile due to its rich humic acid content, phytohormones, and diverse microbial communities that stimulate plant secondary metabolism [51]. Comparable enhancements in phenolic content and antioxidant activity have been reported in crops such as tomato, strawberry, basil, and Withania somnifera [52]. Increased Phenolic compounds play a role in enhancing plant resilience through reinforcement of cell wall formation and nutrient uptake regulation, thereby simultaneously functioning as a defense mechanism against pathogens and pests [53]. TC content can affect shoot height positively by increasing photosynthetic capacity, which leads to robust plant growth. Elevated TC concentrations improve the light absorption efficiency, thereby increasing glucose formation in plant tissue. This in turn supports biomass build-up and cellular respiration in the plant system, ultimately leading to shoot elongation [54].

Additionally, Fuzzy-TOPSIS analysis marked microbe-assisted vermicompost as the most effective treatment on the basis of key agronomic parameters, highlighting the novelty of applying this decision-making tool for treatment selection rather than [31]. Supplementation of microbe-assisted TLL aerobic compost and vermicompost serves as a nutritious soil amendment and supports beneficial microbial activity by suppressing pathogenic population [55]. The findings of this research are corroborated by the findings of [56]. Overall, the application of microbe-assisted vermicompost and aerobic compost significantly boosts soil fertility, agronomic traits, yield, and nutritional quality of okra, while lowering PHM accumulation [57]. Despite the promising outcomes, the pot-based experimental trial has its own limitations, as restricted root growth and altered soil structure in a closed environment might influence rhizosphere interactions and PHM mobility. Nevertheless, the results strongly indicate that microbe-assisted tea leaf litter vermicompost holds substantial potential for field-scale application and represents a sustainable, eco-friendly alternative to synthetic fertilizers for improving crop productivity and soil health.

5. Conclusions

The objective of the research is to assess the efficacy of microbe-assisted TLL vermicompost on sustainable okra production. Outcomes of this study highlighted that bacterial inoculants-assisted TLL vermicompost (T5) performed best, followed by bacterial inoculants-assisted aerobic compost (T9) due to its lignocellulolytic potential. Application of microbe-assisted vermicompost leads to elevated bioavailable macro and micronutrient content in soil at the post-harvest stage and significantly improved soil fertility. Notably, a higher FIAM-HQ value for Pb reflects the possible health hazard associated with chemical fertilizer application. In contrast, the FIAM model validated that TLL compost-treated okra consumption does not pose any PHM-related health risk, as uptake was negligible. Microbe-assisted TLL vermicompost emerged as a viable, environmentally sustainable alternative to conventional chemical fertilizers. Moreover, biochemical and agronomical parameters of okra seem to have flourished in the case of microbe-assisted vermicompost (T5)-treated soil when compared to chemical fertilizer-treated soil (T9). Sobol sensitivity analysis successfully predicts the influence of biochemical parameters on agronomical attributes of okra. Fuzzy TOPSIS analysis ranked microbe-assisted vermicompost (T5) as the best treatment, followed by T8 and T9. The addition of microbe-assisted tea vermicompost significantly increases the yield of okra compared to synthetic fertilizer-treated soil. Hence, lignocellulosic microbe-assisted tea leaf litter compost might serve as a feasible substitute for conventional fertilizer and organic manure. The findings underscore the importance of preserving healthy soil ecosystems, promoting sustainable agrowaste conversion, and forecasting long-term soil resilience.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture16030348/s1, Table S1: Comparison of physicochemical parameters of okra cultivated soil (0 day and post-harvest) amongst different treatment. Table S2: Tabular representation of the FIAM parameters (Constant, β1, β2) among different treatment. Table S3: Tabular representation of agronomical attributes of okra between different treatment. Table S4: Determination of best treatment based on agronomical attributes of okra through Fuzzy-TOPSIS analysis. Table S5: PHM recovery percentage of certified reference material (SRM2710). Table S6: Properties of different TLL Compost. Table S7: Repeated measures univariate ANOVA results (Within Subject Effect). Table S8: Repeated measures univariate ANOVA results (Between Subject Effect).

Author Contributions

R.B.: Formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft; S.B.: Software, review and editing; S.J.: Methodology; P.B.: Conceptualization, supervision, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| PHM/PHMs | Potentially Hazardous Metal(s) |

| TLL | Tea Leaf Litter |

| FIAM | Free Ion Activity Model |

| DTPA | Diethylene Triamine Pentaacetic Acid |

| CD | Cow Dung |

| CRD | Completely randomized design |

| OC | Organic Carbon |

| Avl N | Available Nitrogen |

| Avl P | Available Phosphorus |

| Avl K | Available Potassium |

| MBC | Microbial Biomass carbon |

| BSR | Basal Soil respiration |

| SIR | Substrate-Induced Respiration |

| FDA | Fluorescein Diacetate |

| DHG | Dehydrogenase Activity |

| BCF | Bioconcentration Factor |

| BAF | Bioaccumulation Factor |

| TF | Translocation Factor |

References

- Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Novellino, E.; Souto, E.B.; Daliu, P.; Santini, A. Abelmoschus esculentus (L.): Bioactive components’ beneficial properties—Focused on antidiabetic role—For sustainable health applications. Molecules 2018, 24, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, N.J.; Tripathy, P.; Sahu, G.S.; Dash, S.K.; Lenka, D.; Mishra, S. Correlation and Path Analysis of Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L. Monech) Germplasms for Fruit Yield and its Components. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 1963–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Jain, R.; Jain, V.; Jain, S. A review on: Abelmoschus esculentus. Pharmacia 2012, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.T. Phytochemical information and pharmacological activities of Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus): A literature-based review. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, S.; Ghosh, S.; Banerjee, S.; Bhattacharyya, P. Evaluation of oil sludge vermicompost for integrated nutrient management in rain fed wetland rice (Oryza sativa L.): SAMOE, FIAM and Fuzzy. J. Crop Weed 2023, 19, 148–163. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, M.W. Chemical fertilizer in transformations in world agriculture and the state system, 1870 to interwar period. J. Agrar. Change 2018, 18, 768–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, P.; Ghosh, S.; Banerjee, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhattacharyya, P. Evaluating the efficacy of vermicomposted products in rain-fed wetland rice and predicting potential hazards from metal-contaminated tannery sludge using novel machine learning tactic. Chemosphere 2024, 358, 142272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, Y.; Islam, T.M.; Naidu, Y.; Meon, S. The conjunctive use of compost tea and inorganic fertiliser on the growth, yield and terpenoid content of Centella asiatica (L.) urban. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 130, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, B.B.; Yeasin, M.; Paul, R.K.; Deka, D.; Malakar, H.; Saikia, J.; Rahman, F.H.; Maiti, C.S.; Sarkar, A.; Handique, J.G. Pollution indices of selected metals in tea (Camellia sinensis L.) growing soils of the Upper Assam region divulges a non-trifling menace of National Highway. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 922, 170737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, P.; Chen, M.; Du, M.; Pang, X.; Ye, J.; Wang, H.; Jia, X. Effects of pruning on tea tree growth, soil enzyme activity and microbial diversity. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, Y.; Ud Din, I.; Tayyab, M.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, T.; Cai, Z.; Zhao, H.; Lin, X.; Lin, W.; Lin, S. Soil sickness in aged tea plantation is associated with a shift in microbial communities as a result of plant polyphenol accumulation in the tea gardens. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Sharma, S. Composting of a crop residue through treatment with microorganisms and subsequent vermicomposting. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 85, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, M.K.; Pandey, A.K.; Khan, J.; Bundela, P.S.; Wong, J.W.; Selvam, A. Evaluation of thermophilic fungal consortium for organic municipal solid waste composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 168, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.; Verma, A.; Bhattacharyya, P. Assessing the effectiveness of vermicomposted products and predicting potential hazards from metal contaminated steel waste through multi-model analysis. Water Air Soil Poll. 2023, 234, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Sauza, R.M.; Álvarez-Jiménez, M.; Delhal, A.; Reverchon, F.; Blouin, M.; Guerrero-Analco, J.A.; Cerdán, C.R.; Guevara, R.; Villain, L.; Barois, I. Earthworms Building Up Soil Microbiota, a Review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2019, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, Y.; Meon, S.; Ismail, R.; Rahmani, M. Bio-potential of compost tea from agro-waste to suppress Choanephora cucurbitarum L. the causal pathogen of wet rot of okra. Biol. Control 2009, 49, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Ghosh, S.; Jha, S.; Kumar, S.; Mondal, G.; Sarkar, D.; Datta, R.; Mukherjee, A.; Bhattacharyya, P. Assessing pollution and health risks from chromite mine tailing contaminated soils in India by employing synergistic statistical approaches. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 880, 163228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sianaki, O.A.; Masoum, M.A. A fuzzy TOPSIS approach for home energy management in smart grid with considering householders’ preferences. In Proceedings of the Innovative Smart Grid Technologies (ISGT), Washington, DC, USA, 24–27 February 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1–6.

- Page, A.L.; Miller, R.H.; Keeney, D.R. Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 2. Soil Science Society of America, Madison WI; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, S.; Ludden, P.W. Post-translational regulation of nitrogenase in photosynthetic bacteria. In Genetics and Regulation of Nitrogen Fixation in Free-Living Bacteria; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Joergensen, R.G.; Wu, J.; Brookes, P.C. Measuring soil microbial biomass using an automated procedure. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 873–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alef, K. Phosphatase activity. In Methods in Applied Soil Microbiology and Biochemistry; Alef, K., Nannipieri, P., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tabatabai, M.A. Soil enzymes. In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 2. Microbiological and Biochemical Properties; Weaver, R.W., Angel, J.S., Bottomley, P.S., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1994; pp. 775–783. [Google Scholar]

- Schnrer, J.; Rosswall, T. Fluorescein diacetate hydrolysis as a measure of total microbial activity in soil and litter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1982, 43, 1256–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.D.; Hasan, M.M.; Rahaman, A.; Haque, P.; Islam, M.S.; Rahman, M.M. Translocation and bioaccumulation of trace metals from industrial effluent to locally grown vegetables and assessment of human health risk in Bangladesh. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golui, D.; Mazumder, D.N.G.; Sanyal, S.K.; Datta, S.P.; Ray, P.; Patra, P.K.; Sarkar, S.; Bhattacharya, K. Safe limit of arsenic in soil in relation to dietary exposure of arsenicosis patients from Malda district, West Bengal—A case study. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 144, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.B.; Singh, Y.K.; Mandal, J.; Shambhavi, S.; Sadhu, S.K.; Kumar, R.; Ghosh, M.; Raj, M.; Singh, M. Determination of safe limit for arsenic contaminated irrigation water using solubility free ion activity model (FIAM) and Tobit Regression Model. Chemosphere 2021, 270, 128630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnon, D.I. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julkunen-Tiitto, R. Phenolic constituents in the leaves of northern willows: Methods for the analysis of certain phenolics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1985, 33, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indahingwati, A.; Barid, M.; Wajdi, N.; Susilo, D.E.; Kurniasih, N.; Rahim, R. Comparison analysis of TOPSIS and fuzzy logic methods on fertilizer selection. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2019, 7, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, R.; Mondal, S.; Mandal, J.; Bhattacharyya, P. From fuzzy-TOPSIS to machine learning: A holistic approach to understanding groundwater fluoride contamination. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, S.; Zarei, M.R.; Karamoozian, A.; Mohammadpour, A.; Azhdarpoor, A. Sobol sensitivity analysis for non-carcinogenic health risk assessment and water quality index for Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad Province. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 104342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivenge, P.; Vanlauwe, B.; Gentile, R.; Six, J. Organic resource quality influences short-term aggregate dynamics and soil organic carbon and nitrogen accumulation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahni, S.; Sarma, B.K.; Singh, D.P.; Singh, H.B.; Singh, K.P. Vermicompost enhances performance of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria in Cicer arietinum rhizosphere against Sclerotium rolfsii. Crop Prot. 2008, 27, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Wang, X.; Xue, W.; Liu, Y.; Wu, B. Addition of microbes shifts the ability of soil carbon sequestration in the process of soil Cd remediation. J. Soils Sediments 2024, 24, 2669–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Srivastava, P.; Devi, R.S.; Bhadouria, R. Influence of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides on soil health and soil microbiology. In Agrochemicals Detection, Treatment and Remediation; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Nannipieri, P.; Ascher, J.; Ceccherini, M.; Landi, L.; Pietramellara, G.; Renella, G. Microbial diversity and soil functions. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2017, 68, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilly, O. Microbial energetics in soils. In Microorganisms in Soils: Roles in Genesis and Functions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Macci, C.; Doni, S.; Peruzzi, E.; Masciandaro, G.; Mennone, C.; Ceccanti, B. Almond tree and organic fertilization for soil quality improvement in southern Italy. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 95, S215–S222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Wang, P.; Kong, C.H. Urease, invertase, dehydrogenase and polyphenoloxidase activities in paddy soil influenced by allelopathic rice variety. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2009, 45, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Ji, L.; Hu, Z.; Yang, X.; Li, H.; Jiang, Y.; He, T.; Yang, Y.; Ni, K.; Ruan, J. Organic amendments improved soil quality and reduced ecological risks of heavy metals in a long-term tea plantation field trial on an Alfisol. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.; Banerjee, S.; Ghosh, S.; Verma, A.; Bhattacharyya, P. Appraisal of Heavy Metal Risk Hazards of Eisenia fetida-Mediated Steel Slag Vermicompost on Oryza sativa L.: Insights from Agro-Scale Inspection and Machine Learning Analytics. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, V.; Feller, U. Heavy metals in crop plants: Transport and redistribution processes on the whole plant level. Agronomy 2015, 5, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Ren, Y.; Shi, Q.; Wang, X.; Wei, M.; Yang, F. Effects of vermicompost on quality and yield of watermelon. China Veg. 2011, 6, 76–79, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Seth, T.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Dutta, S.; Hazra, P.; Singh, B. Genetic control of yellow vein mosaic virus disease in okra and its relationship with biochemical parameters. Euphytica 2017, 213, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romdhane, L.; Ebinezer, L.B.; Panozzo, A.; Barion, G.; Dal Cortivo, C.; Radhouane, L.; Vamerali, T. Effects of soil amendment with wood ash on transpiration, growth, and metal uptake in two contrasting maize (Zea mays L.) hybrids to drought tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 661909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, M.; Dumat, C.; Khalid, S.; Schreck, E.; Xiong, T.; Niazi, N.K. Foliar heavy metal uptake, toxicity and detoxification in plants: A comparison of foliar and root metal uptake. J. Hazard. Mat. 2017, 325, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallovo, C.; Schreiner, M.; Schwarz, D.; Colla, G.; Krumbein, A.P. Hytochemical changes induced by different nitrogen supply forms and radiation levels in two leafy Brassica species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 4198–4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.O.; Agbenorhevi, J.K.; Kpodo, F.M. Total phenol content and antioxidant activity of okra seeds from different genotypes. Am. J. Food Nutr. 2017, 5, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.K.; Chahal, A.S.; Sharma, A.; Alam, M.A. Synergistic Impact of Humic Acid and Biofertilizers on the Growth and Yield of Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch): A Review. J. Exp. Agric. Int. 2025, 47, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhani, I.; Srivastava, V.; Megharaj, M.; Suthar, S.; Garg, V.K.; Singh, R.P. Effect of compost and vermicompost amendments on biochemical and physiological responses of lady’s finger (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) grown under different salinity gradients. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowska, Z.; Gradowski, M.; Dobrzyński, J. Role of plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) in enhancing phenolic compounds biosynthesis and its relevance to abiotic stress tolerance in plants: A review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2025, 118, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales-Alvarado, A.C.; Cardoso, J.C. Development, chlorophyll content, and nutrient accumulation in in vitro shoots of Melaleuca alternifolia under light wavelengths and 6-BAP. Plants 2024, 13, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theunissen, J.; Ndakidemi, P.A.; Laubscher, C.P. Potential of vermicompost produced from plant waste on the growth and nutrient status in vegetable production. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2010, 5, 1964–1973. [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor, A.; Naveed, M.S.; Ali, R.M.A.; Naseer, M.A.; Ul-Hussan, M.; Saqib, M.; Farooq, M. Vermicompost: A potential organic fertilizer for sustainable vegetable cultivation. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 336, 113443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Yu, H.; Li, Q.; Gao, Y.; Sallam, B.N.; Wang, H.; Liu, P.; Jiang, W. Exogenous application of amino acids improves the growth and yield of lettuce by enhancing photosynthetic assimilation and nutrient availability. Agronomy 2019, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.