Abstract

Sawdust represents a locally available lignocellulosic resource that may complement ruminant diets during periods of forage shortage. This study evaluated the feeding value of birch (Betula pendula) sawdust subjected to physical and chemical processing using a stepwise experimental approach. Steam-exploded and fresh sawdust were treated with 0, 4% ammonia, or 4% sodium hydroxide in a 2 × 3 factorial design and initially evaluated by in vitro gas production, dry matter digestibility, and fermentation pH. Based on these results, selected materials were further assessed for rumen dry matter and fiber degradation using the in sacco technique in cannulated dairy cows, with untreated and ammonia-treated wheat straw included for comparison. In addition, steam-exploded sawdust was compared with wheat straw and grass silage for in vivo digestibility in sheep. A pilot study also tested aspen (Populus tremula) sawdust in lactating cow diets. Steam explosion substantially reduced fiber fractions, particularly hemicellulose, and increased residual carbohydrates, resulting in higher gas production and in vitro digestibility compared with fresh sawdust (p < 0.05). Ammonia treatment markedly increased crude protein content, whereas sodium hydroxide primarily increased ash concentration. In sacco, steam-exploded birch showed similar or higher ruminal dry matter and neutral detergent fiber degradation compared with ammonia-treated wheat straw, while untreated fresh birch remained largely undegraded. In vivo, steam-exploded sawdust exhibited greater organic matter digestibility and net energy than untreated wheat straw but remained less digestible than grass silage (p < 0.0001). A pilot feeding test with lactating dairy cows demonstrated good acceptance of untreated aspen sawdust as a partial roughage substitute under non-standardized conditions. Overall, the results indicate that steam-exploded sawdust has potential as a complementary roughage source for ruminants when conventional forages are limited.

1. Introduction

Ruminants play a key role in global food systems by converting fibrous plant biomass unsuitable for human consumption into high-quality animal products. Worldwide, ruminant livestock utilize approximately 3.6 billion hectares of grasslands and forage resources, accounting for nearly 70% of agricultural land [1]. The stability and availability of roughage are therefore central to sustainable ruminant production. Increasing climatic variability, including more frequent droughts and extreme weather events, has already led to substantial forage yield losses and is projected to further destabilize feed supply chains globally [2]. Because roughage production depends largely on local conditions, regional livestock systems remain especially vulnerable during periods of feed shortage, highlighting the need for resilient, regionally available fiber sources. Effective roughage substitutes should provide adequate structural fiber to maintain rumen function, be readily available during periods of shortage, and ensure both animal health and product safety [3,4]. Increasing the utilization of fibrous biomass unsuitable for human or monogastric animal consumption has been proposed as a strategy to strengthen the role of ruminants in sustainable food production [5].

Forest biomass represents a substantial and geographically concentrated resource that could contribute to alleviating roughage deficits, particularly in northern Europe. Forests cover approximately 76% of Finland, 74% of Sweden, 46% of Norway, and 16% of Denmark [6]. Across the European Union, forested land reached about 160 million hectares in 2022, corresponding to 39% of total land area [7]. Sawmilling operations associated with this forest base generate several million tonnes of residues annually, including sawdust, much of which remains underutilized. Historically, severe feed shortages have prompted the use of unconventional forest-derived materials such as leaves, twigs, raw wood, and seaweed as emergency feed resources [8,9]. These experiences suggest that forest by-products may contribute to ruminant feeding systems, provided their nutritional limitations are adequately addressed.

From a nutritional perspective, wood residues contain considerable amounts of structural carbohydrates, typically 40–50% cellulose and 20–30% hemicellulose, but also 20–30% lignin, which severely restricts ruminal degradation [9]. As a result, untreated sawdust has low digestibility and energy value. Feeding trials have shown that untreated sawdust can be included at low levels, generally around 5–10% of dietary dry matter, primarily as a source of physical fiber in high-concentrate diets, without negative effects on feed intake or rumen function [8,10]. In beef cattle finishing diets, inclusion levels of up to approximately 8% of dietary dry matter have been reported to maintain animal performance when rations are appropriately balanced [11]. In contrast, higher inclusion rates, particularly above 10–15% of dietary dry matter, consistently reduce digestibility and performance, especially in high-producing dairy cows [12].

To improve the feeding value of sawdust, several pretreatment technologies have been developed that can modify the lignocellulosic structure and increase microbial accessibility. Alkali treatments using sodium hydroxide or ammonia have long been employed to enhance the digestibility of fibrous feeds by disrupting lignin–carbohydrate complexes, with reported increases in neutral detergent fiber digestibility of 10–30 percentage units depending on treatment conditions and substrate characteristics [13,14]. Steam explosion has also been shown to improve fiber utilization by defibrating wood particles, reducing particle size, and increasing enzymatic cellulose accessibility [15]. Compared with more intensive chemical processes, steam explosion is associated with relatively low capital investment, moderate energy requirements, and limited environmental impact [16]. Alternative approaches, such as biological treatment with white-rot fungi, have demonstrated potential to selectively degrade lignin, although long processing times and variable effectiveness currently limit their practical application [17]. In parallel, conversion of wood biomass into yeast protein has shown promise as a protein source for several livestock species, including farmed fish [18], poultry [19], pigs [20], and dairy cows [21]; however, the need for sequential pretreatment, enzymatic hydrolysis, and fermentation steps remains a major constraint to large-scale implementation [22,23,24].

The present work compiles results from a series of experiments conducted following the severe summer drought of 2018 in northern Europe, a period that highlighted the vulnerability of regional forage systems. The objective was to evaluate the effects of steam explosion and alkali treatments (NH3 and NaOH), applied individually or in combination, on the feed value of sawdust using in vitro gas production, in sacco rumen degradation in cannulated dairy cows, and in vivo digestibility measurements in sheep. In addition, a pilot feeding study with lactating Norwegian Red dairy cows was conducted to assess the acceptability of aspen (Populus tremula) sawdust when substituting part of the dietary roughage. Parts of these results have previously been presented at Nordic Feed Science conferences [25,26].

2. Materials and Methods

The experiments were conducted during autumn 2018 and throughout 2019 at the Faculty of Biosciences, Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU). The experimental work comprised four components: (1) in vitro gas production of six birch sawdust treatments using the ANKOM RF gas production system; (2) in sacco rumen degradability of three selected sawdust materials using rumen-cannulated dairy cows; (3) in vivo digestibility assessment of steam-exploded sawdust combined with grass silage and straw in sheep; and (4) evaluation of feed acceptance and milk production in dairy cows offered diets in which sawdust partially replaced roughage. The in-sacco and in vivo techniques are standard methods within the Nordic Feed Evaluation System [27] for evaluating ruminant feeds.

2.1. Experimental Design of Physicochemical Treatment of Birch Sawdust

The feed material used in the physicochemical treatment was sawdust from a birch (Betula pendula) tree. One batch of sawdust was fully steam-exploded by Glommen Technology AS (Elverum, Norway), while the other batch consisted of fresh, untreated sawdust. Both batches were further treated with either ammonia (NH3) or sodium hydroxide (NaOH) at 4% of the sawdust dry weight, following procedures established for commercial straw treatment for ruminants [14]. Untreated portions from both batches were retained as controls. Briefly, a 10% (w/v) solution of NH3 or NaOH was prepared by dissolving the respective chemical in water. For each 100 g of sawdust (dry weight), 40 mL of the 10% solution was applied using a syringe, yielding a target moisture content of approximately 50%. Treated sawdust was thoroughly mixed to ensure uniform chemical distribution. Both the steam-exploded and fresh sawdust batches were subjected to the same chemical treatments, resulting in six treatment combinations (2 sawdust types × 3 chemical treatments: NH3, NaOH, untreated), as outlined in Table 1. Each treated material was placed in four replicated airtight containers and incubated at room temperature for 5 weeks to allow for chemical reaction and stabilization. Containers were gently mixed weekly to maintain homogeneity and prevent localized differences in moisture or chemical exposure.

Table 1.

Treatment combinations and codes for birch sawdust processing.

2.2. Chemical Analysis

After 35 days of storage in sealed containers, the treated materials, along with untreated controls, were freeze-dried in preparation for milling. The samples were ground through a 1.0 mm sieve using a Retsch SM 200 cutting mill (Retsch GmbH, Haan, Germany). Samples were analyzed in quadruplicate for dry matter (DM) following AOAC method 930.15, ash with method 942.05, and Kjeldahl nitrogen (N) using method 984.13 [28]. Crude protein (CP) content was calculated as N × 6.25. Neutral detergent fiber (NDF), acid detergent fiber (ADF), and acid detergent lignin (ADL) were measured on an organic matter basis following the procedures of Van Soest and Robertson [29] with an Ankom200 fiber analyzer (Ankom Technology, Macedon, NY, USA). Hemicellulose and cellulose contents were derived as NDF–ADF and ADF–ADL, respectively. Residual carbohydrate (RestCHO) was estimated as the remaining carbohydrate fraction by subtracting protein, fat, starch, NDF, and NH3-N from organic matter.

2.3. In Vitro Gas Production

In vitro gas production was conducted for six treatments (Table 1) using the ANKOM RF Gas Production System (ANKOM Technology; Macedon, NY, USA). A buffer solution was prepared following the method of Goering and Van Soest [30], and rumen fluid was collected from two rumen-fistulated, non-lactating Norwegian Red cows four hours after their morning feeding. The cows were fed at maintenance level with a diet consisting of hay, straw, and concentrate. The diet contained 67% roughage and 33% concentrate on a dry matter basis, with a crude protein content exceeding 120 g/kg DM, according to the standard method [31]. Rumen fluid was obtained from the central rumen and transferred immediately into a pre-warmed thermos flask. The rumen fluid from both cows was mixed and filtered through a 250 µm nylon mesh filter (SEFAR NITEX, Sefar AG, Heiden, Switzerland). Incubation began within one hour of rumen fluid collection. A 1 g dry matter sample of feed was weighed into 250 mL glass bottles and mixed with 33.3 mL of rumen fluid and 66.7 mL of preheated buffer solution, all under continuous flushing with carbon dioxide. Each treatment was incubated in triplicate, along with three blanks (containing only rumen fluid and buffer) and an internal standard feed. Two incubation batches were conducted, each lasting 72 h in a 39 °C cabinet with constant gentle shaking using the Stuart SSL3 3D gyro-rocker (Cole-Palmer Ltd., Staffordshire, UK). Gas production was recorded every ten minutes over 72 h. The cumulative gas pressure (psi) was converted into gas volume (mL/g DM) using the ideal gas law and Avogadro’s law [32]. The gas production data were modeled using the approach by Groot et al. [33], assuming a single-phase fermentation pool, described by the equation GP = A/(1 + (B/t)C), where GP is the cumulative gas volume at time “t,” “A” represents the asymptotic maximum potential gas production (mL/g DM), “B” is the time (hours) to produce half of “A,” and “C” is a dimensionless shape parameter of the curve.

At the end of the 72 h incubation period, data on the pH of the incubated media (pH72) and in vitro DM digestibility (IVDMD) were collected. The pH was measured using a portable pH-meter (WTW, pH 3310, Germany, with a Hamilton Bonaduz AG, Polyplast Pro, Switzerland, pH sensor). For IVDMD, the contents of each bottle were recovered into an in sacco nylon bag with a pore size of 12 mm. The bottles were rinsed with distilled water, and the nylon bags were then washed in a washing machine at 25 °C using the wool cycle, without centrifugation, following the standard in sacco method [31]. After washing, the bags were dried at 45 °C for 48 h, and the IVDMD (%) was calculated as the proportion of feed residue that had disappeared from the original weighed amount.

2.4. In Sacco Experimental Procedure

Rumen degradation kinetics of sawdust preparations (A1, B1, and B2; Table 1) were evaluated using the in sacco method in three rumen-fistulated, non-lactating dairy cows fed a standard diet, following the procedure by Åkerlind et al. [31]. A1, B1, and B2 were chosen for the in sacco trial based on their in vitro results, where A1 showed improved gas production and IVDMD, B1 served as the untreated lignocellulosic reference, and B2 was selected for increased nitrogen content and gas production through ammoniation. Untreated and ammonia-treated wheat straw were included for comparison. Ground feed samples were weighed into nylon bags (38 μm pore size) and incubated in the rumen at 0, 2, 4, 8, 16, 24, 48, and 96 h, with the number of replicate bags per incubation time being 3, 6, 6, 6, 9, 9, 9, and 12, respectively (Table 2). To determine indigestible NDF (iNDF), samples were incubated for 288 h in 12 μm pore size bags [27], with 12 replicates. Zero-hour bags were prepared by soaking in a 39 °C water bath for 20 min before washing. After incubation, all bags were rinsed in cold tap water without squeezing and machine-washed using a program without spinning at 25 °C, as described for the in vitro gas production residues. The washed residues were oven-dried at 45 °C for 48 h before analysis. DM and NDF degradation profiles were modeled using the nonlinear least-squares (nls) procedure following the exponential model: P = a + b(1 − e−ct), where “P” is the cumulative DM degradability (%) at time “t”, “a” is the rapidly degradable fraction, “b” is the slowly degradable fraction, “c” is the degradation rate constant, and “e” is Euler’s number. Effective degradability (ED) was calculated as ED = a + b × c/(c + k), assuming a rumen outflow rate (k) of 0.05 h−1, following Ørskov and McDonald [34].

Table 2.

Experimental design for the in sacco degradability trial.

2.5. In Vivo Digestibility

The in vivo digestibility of steam-exploded birch (A1) was assessed alongside untreated wheat straw and grass silage using adult castrated male sheep (n = 3 per treatment), with each sheep acting as the experimental unit. Steam-exploded birch was selected due to its superior gas production and in sacco degradability compared to other lignocellulosic materials tested. The standard method for organic matter digestibility follows the protocol for sheep fed at maintenance [35]. Early-harvested grass silage served as the main feed, while untreated wheat straw was used as a comparative roughage. Sheep were housed individually in metabolic crates and fed at maintenance levels, with diets (on a dry matter basis) consisting of: (1) grass silage only, 1211 g/day; (2) grass silage with wheat straw, 732 g and 481 g/day, respectively; and (3) grass silage with steam-exploded birch, 732 g and 467 g/day, respectively. After an 11-day adaptation period, total fecal output was collected over 10 consecutive days. Total tract digestibility of organic matter (OMD) and neutral detergent fiber (NDFD) was determined for silage, straw, and steam-exploded birch, with the digestibility of the latter two calculated by difference. Feed energy concentration was expressed as net energy (MJ/kg DM).

2.6. Acceptability and Performance of Cows Fed Aspen Sawdust

A pilot feeding test was carried out with six multiparous (≥3rd lactation) Norwegian Red lactating cows with an average initial body weight (±SE) of 567.1 ± 24.6 kg and a starting milk yield of 23.9 ± 1.51 kg. The cows were kept in tie-stall accommodation equipped with rubber mats, and milked twice daily using a DeLaval milk meter MM6 (DeLaval Inc., Tumba, Sweden). The cows were moved directly from summer pasture to a diet of 10 kg concentrate and 6 kg DM from early cut grass silage (289 g DM/kg, 133 g CP/kg DM, and 414 g NDF/kg DM). The concentrate used had a DM content of 870 g/kg feed and contained 190 g/kg CP, 197 g/kg NDF, and 377 g/kg starch, respectively.

Sawdust was produced by chopping whole aspen logs with bark using a rotating drum with modified chainsaw bands. The initial particle size was too fine, with 10% and 53% of particles retained on 2 mm and 1 mm screens, respectively. After modifications, these sizes changed to 33% and 35%. The test began using the first sawdust quality, switched to the second quality mid-way through the feeding trial, and used a third production lot with longer particles for the final two days. The test started with three cows during an initial acceptance phase, where a small quantity of sawdust was gradually mixed into the concentrate by reducing grass silage. Once the cows adapted to eating the sawdust, three more cows were added on day 8 of the trial. Silage was fed at 07:00 and 18:00, while the concentrate and sawdust were given in equal portions at 07:30, 14:00, and 18:30. Daily monitoring included feed intake (i.e., sawdust, silage, and concentrate), milk yield, and rumination activity using an electronic device (RumiWatch, Itin + Hoch GmbH, Liestal, Switzerland). Milk samples for chemical analysis were collected throughout the test period, which ended on day 22. Rumen pH was measured continuously for the last three days of the experiment, with data logging at 10 min intervals, in a fistulated cow using a portable pH meter (pH 3310) (WTW GmbH, Weilheim, Germany) with an adapted electrode.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.5.1; R Core Team) [36]. Data on chemical composition, gas production at 72 h (GP72), IVDMD, and pH were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA according to the model:

where Yij is the response variable (e.g., Chemical compositions, GP72, A, B, C, IVDMD, pH); μ is the overall mean; βi is the effect of physical treatment (steam-exploded or fresh sawdust); γj is the effect of chemical treatment (NaOH-treated, NH3-treated, or non-treated); (βγ)ij is the interaction between physical and chemical treatments; and ϵij is the random error. Assumptions of ANOVA, including normality of residuals and homogeneity of variances, were checked using Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. Treatment means were compared using Tukey’s multiple comparison test when ANOVA indicated significant effects.

Yij = μ + βi + γj + (βγ)ij + ϵij,

Cumulative gas production data were summarized as mean ± standard error for each feed and incubation time. Rumen degradation profiles of DM and NDF were fitted to an exponential model using nonlinear least-squares (nls). In vivo organic matter and NDF digestibility, as well as net energy of the three feeds, were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, and the results were visualized using the tidyverse [37] and ggplot2 [38] packages. However, data from the feeding trial with lactating dairy cows were summarized descriptively, focusing on practical implications, and were not subjected to formal statistical testing. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied for all statistical analyses.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition After 35 Day of Physicochemical Treatment of Birch

Dry matter was significantly affected by chemical treatment (p = 0.003) but not by physical processing or their interaction (Table 3). Ash content increased with NaOH treatment (p < 0.001) and was unaffected by steam explosion. Crude protein showed significant interaction between physical and chemical treatments (p < 0.001), with ammonia-treated samples exhibiting the highest concentrations. NDFom was significantly reduced by steam explosion and showed a notable interaction with chemical treatment (p = 0.013), whereas ADFom, ADLom, and cellulose were primarily influenced by physical processing. Hemicellulose and residual carbohydrates were significantly affected by the interaction (p < 0.001), with untreated samples exhibiting the highest residual carbohydrates and ammonia-treated sawdust showing the lowest, reflecting hemicellulose depolymerization and the accumulation of soluble carbohydrates (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of physicochemical treatment on chemical composition of birch sawdust after 35 days (g/kg DM).

Steam explosion caused substantial structural disruption in birch sawdust, significantly reducing NDFom from 906 ± 16 g/kg in fresh sawdust to 538 ± 12 g/kg in steam-exploded samples (−40%, p < 0.001) and decreasing ADFom from 682 ± 12 to 520 ± 13 g/kg DM (−24%). Hemicellulose content was particularly affected, decreasing from 224 ± 19 g/kg in fresh sawdust to 17.7 ± 4.1 g/kg in steam-exploded samples. These results are consistent with previous findings: Shi et al. [39] reported decreases of 32% in NDF and 81% in hemicellulose in steam-exploded corn stover, Ju et al. [11] observed reductions in oak NDF from 86.5% to 71.5% (−17%) and hemicellulose from 23.2% to 11.0% (−53%), and in pine NDF from 92.4% to 80.5% (−13%) and hemicellulose from 18.2% to 7.4% (−59%). Similarly, Yue et al. [40] reported a ~90% decrease in hemicellulose in bulrush, with a 25% increase in soluble sugars and 150% increase in total organic carbon. Hemicellulose, being amorphous and thermally labile, is readily depolymerized under elevated temperature and pressure, producing soluble monosaccharides and oligosaccharides [41,42]. In the present study, the marked increase in residual carbohydrates from 33 ± 44 g/kg in fresh sawdust to 384 ± 70 g/kg in steam-exploded samples reflects hemicellulose breakdown and accumulation of soluble carbohydrate intermediates.

Steam explosion also decreased lignin content (Table 3), indicating cleavage of lignin–cellulose bonds and disruption of the lignin matrix. This structural alteration improved fiber accessibility and is consistent with partial lignin removal reported in bulrush [40], although species-specific responses have been observed: Ju et al. [11] reported no change in oak and pine lignin, while Shi et al. [39] found a 4% increase in lignin in corn stover due to unbound lignin accumulation. Hardwood species such as birch and aspen are generally more digestible than softwoods like pine and spruce [43]. Lower NDF and ADL values in steam-exploded birch suggest enhanced nutritive value and potential for improved digestibility in ruminant diets. Residual carbohydrate (ResCHO) was highest in untreated, steam-exploded sawdust (A1, 442 g/kg DM) and lowest in chemically treated groups (B2, 25 g/kg DM), highlighting that chemical treatments mobilize structural carbohydrates.

Chemical treatment further modified the sawdust composition. Ammonia (NH3) treatment substantially increased crude protein, with A2 reaching 162.5 g/kg DM (+142% relative to untreated steam-exploded A1) and B2 reaching 128.1 g/kg DM (+123% relative to untreated fresh B1). This reflects nitrogen incorporation from ammonia addition, with theoretical CP values approaching 200 g/kg DM at 4% anhydrous ammonia application; slightly lower measured values may result from ammonia loss during treatment. NH3 treatment also likely enhanced fiber digestibility by breaking lignin–cellulose bonds [14]. In contrast, NaOH treatment significantly increased ash content (A3 and B3 ~24 g/kg DM) due to sodium incorporation, which can facilitate lignin–carbohydrate bond cleavage [44]. The increase in ash content reflects the addition of sodium with NaOH rather than mineral solubilization, as ash is determined after combustion. While moderate sodium addition can be beneficial, excessive NaOH application may lead to ash levels above typical forage recommendations [45], which could reduce feed intake [46]. In such cases, animals should have free access to water to help excrete excess sodium, and environmental considerations must be taken into account when handling NaOH [47]. These results indicate that steam explosion primarily alters fiber structure, increasing ResCHO availability, whereas NH3 treatment increases nitrogen content and may further improve fiber digestibility, and NaOH modifies ash content with potential chemical effects on fiber utilization.

3.2. In Vitro Gas Production and DM Disappearance

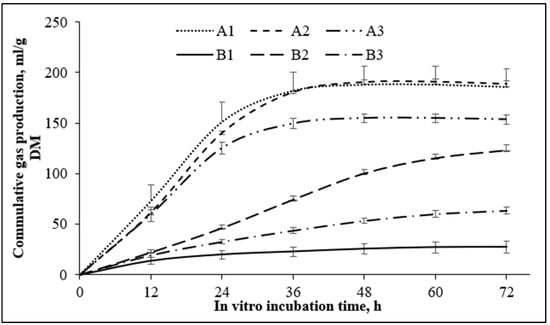

The in vitro gas production profile of birch sawdust under different physicochemical treatments is shown in Figure 1, with fermentation parameters summarized in Table 4. There was a significant interaction between steam explosion and chemical treatment for both GP72 (p < 0.0001) and asymptotic gas production (p = 0.003). Steam-exploded sawdust, both untreated (A1) and ammonia-treated (A2), achieved the highest cumulative gas production over 72 h. Alkali treatment of fresh sawdust increased GP72 and asymptotic gas production, particularly with ammonia, whereas NaOH had a limited effect. For steam-exploded sawdust, additional alkali treatment did not enhance gas production. Untreated fresh sawdust consistently produced the lowest gas throughout the incubation period, highlighting the strong effect of steam explosion on improving fermentability.

Figure 1.

Cumulative gas production (mL/g DM) over time of incubation (A1 = Steam-exploded, without alkali treatment; A2 = Steam-exploded NH3 treated; A3 = Steam-exploded NaOH treated; B1 = Fresh sawdust, without alkali treatment; B2 = Fresh sawdust NH3 treated; B3 = Fresh sawdust NaOH treated).

Table 4.

Effect of physicochemical treatment the in vitro gas production characteristics of birch sawdust (GP72 = gas volume at 72 h, mL/g DM, A = asymptotic gas volume, mL/g DM incubated; B = time in hours taken to produce half of the asymptotic gas volume; and C is the shape parameter).

Steam explosion of sawdust increased in vitro gas production, indicating improved feed value, whereas further alkali treatment did not enhance fermentability. Alkali treatment, especially with ammonia (NH3), enhanced the degradation of fresh birch, likely because of its ability to penetrate the lignocellulosic matrix and cleave ester and lignin–carbohydrate linkages. This chemical action promotes swelling of the cell wall, increases porosity and internal surface area, and facilitates the redistribution or partial removal of lignin and hemicellulose, thereby improving microbial access to structural carbohydrates during fermentation and enhancing fiber degradation [48]. The higher crude protein content from NH3 treatment may have further stimulated microbial activity. Residual carbohydrate (ResCHO) content was a major determinant of fermentability, as higher ResCHO correlated with increased gas production, consistent with evidence that fermentable carbohydrate availability drives in vitro fermentation kinetics [49]. In contrast, NaOH treatment of steam-exploded birch reduced gas production after 18 h, likely due to chemical modifications of the cell wall and the release of phenolic compounds, such as ferulic and p-coumaric acids, that have been shown to inhibit microbial activity in alkali-treated corn fiber and wheat bran [48,50].

For IVDMD and pH of the incubated materials, these parameters reflected the gas production profile, except that there was no significant interaction effect between the steam explosion and alkali treatments (p > 0.05). Fresh, unexploded sawdust exhibited the lowest IVDMD, accompanied by a significantly higher pH, whereas steam explosion increased IVDMD and lowered the pH of the incubated material. Although fresh, unexploded sawdust treated with ammonia showed a slight increase in gas production, its digestibility remained substantially lower than that of steam-exploded sawdust. This difference is due to the high lignin content in fresh, unexploded sawdust, which hinders microbes from accessing cellulose and hemicellulose. Steam explosion, however, effectively breaks the lignin bonds, making cellulose and hemicellulose more accessible for digestion. Importantly, these results indicate that additional alkali treatment of steam-exploded material is unnecessary, as steam explosion alone is sufficient to achieve significant improvements in digestibility.

3.3. In Sacco Degradability Using Cannulated Cows

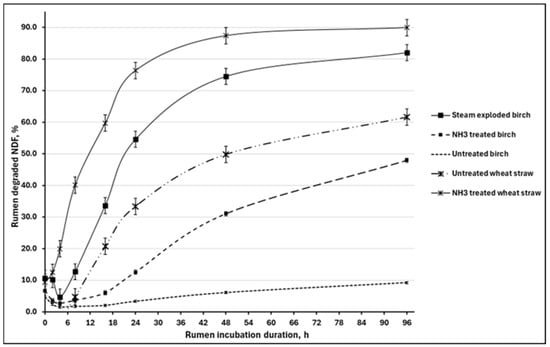

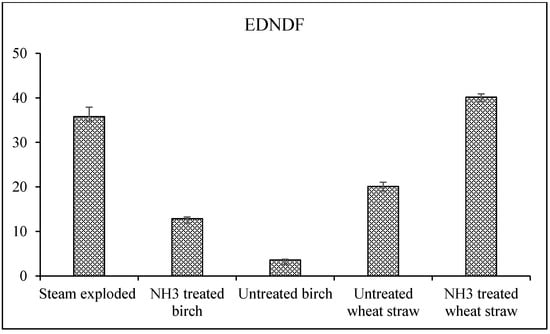

The rumen degradation profiles of DM and NDF for birch sawdust selected from an in vitro trial (i.e., A1, B1, and B2) and two types of wheat straw (ammonia treated vs. untreated) are shown in Table 5 and Figure 2, respectively. Steam-exploded birch achieved similar or higher ruminal DM and NDF degradation compared to ammonia-treated straw. Untreated wheat straw outperformed ammonia-treated fresh birch for both parameters. Conversely, untreated fresh birch remained almost undegraded in the rumen, indicating its limited digestibility with only 3% DM degradability at 96 h and nearly 90% still undegraded even after 288 h of incubation. The low degradation is supported by the in vitro gas production data mentioned above.

Table 5.

In sacco degradability and effective degradability of DM (EDDM) of sawdust and straw over rumen incubation time.

Figure 2.

In sacco rumen degradation profile of NDF.

The high in sacco DM degradability of steam-exploded sawdust and ammonia-treated straw (84% at 96 h), compared to the minimal degradation of untreated material (3%), highlights the improved nutritional value of steam-exploded biomass for ruminants. This aligns with Ju et al. [11], who showed that steam-digested oak roughage, with similar improvements in degradability, can replace up to 50% of total forage or completely substitute rice straw in the total mixed rations of early fattening steers. Ammonia treatment of birch increased rumen degradation of DM, but to a much lesser extent than steam explosion, as indicated by lower DM degradation values. This is because steam explosion disrupts the lignin matrix more effectively than ammonia, which mainly acts on hemicellulose and cellulose without extensively changing the lignin structure [51]. Untreated fresh birch remains undegradable due to its intact lignin structure, which blocks microbial enzymes from accessing degradable carbohydrates [49]. Therefore, fresh untreated birch showed the highest level of iNDF, while steam-exploded birch and NH3-treated straw showed the lowest iNDF levels (Figure 3). Steam-digestion treatment was found to reduce neutral detergent-insoluble fiber by 17% in oak and 13% in pine trees, as reported by Ju et al. [11].

Figure 3.

Effective degradability of NDF.

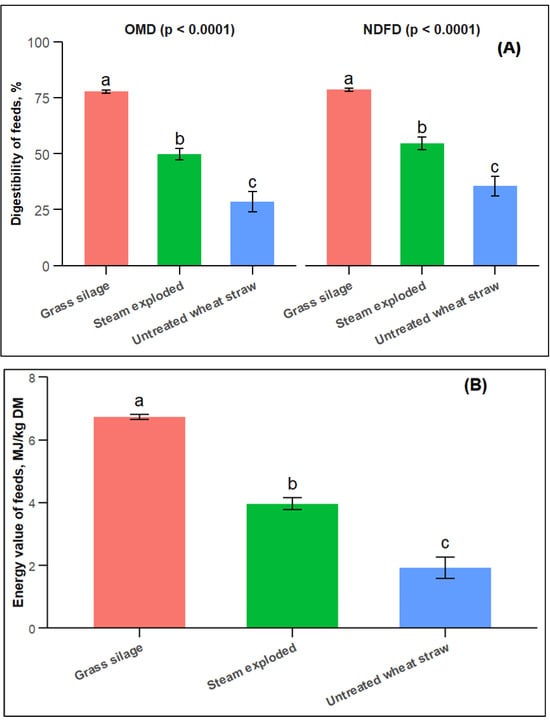

3.4. In Vivo Digestibility Using Castrated Rams

Steam-exploded birch exhibited significantly higher OMD compared with untreated wheat straw (p < 0.0001), reaching approximately 50%. This value aligns well with the effective degradability results from the in situ trial and previously reported digestibility of woody materials [52]. A consistent pattern was observed across all measured parameters (OMD, NDFD, and NE), with grass silage exhibiting the highest values, followed by steam-exploded sawdust and untreated wheat straw (p < 0.0001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Total tract digestibility (A) and estimated net energy value (B) of grass silage, steam exploded birch sawdust, and untreated wheat straw (OMD = Organic matter digestibility; NDFD = Neutral detergent fiber digestibility). Bars with different letters differ significantly (p < 0.05). Tukey’s multiple comparison test was applied to compare means.

The lower digestibility and energy value of steam-exploded sawdust compared with early-harvest grass silage indicate that it should serve as a complementary rather than sole roughage source for ruminants. Structurally, hemicellulose forms the matrix surrounding the cellulose framework in lignocellulosic biomass, while lignin acts as an encrusting material that restricts microbial access [53]. The steam explosion process effectively disrupts lignin, thereby improving enzymatic and microbial accessibility to cellulose and hemicellulose and enhancing nutrient release and energy concentration [54]. The energy value of steam-exploded birch approached that of ammonia-treated straw [55], highlighting its potential as a partial replacement for conventional roughages under constrained feed supply conditions. Nevertheless, consistent with Satter et al. [10], inclusion of long forage remains essential for maintaining rumen function and overall animal performance when steam-exploded sawdust is incorporated into the diet.

3.5. Feeding Trial with Lactating Dairy Cows Using Aspen Sawdust

Admittedly, this trial was conducted before the other experiments described above, using different wood species to investigate whether a substantial portion of roughage in lactating dairy cow diets could be replaced with sawdust and increased concentrate feeds. The study was carried out as part of an emergency response to the severe 2018 drought in Europe, particularly in the Nordic countries, where annual crop harvests, including roughage, were critically low, making herd maintenance a priority over production yield. The bulky nature of conventional roughages, such as grass silage and hay, limited import opportunities, whereas compound feeds were more readily available. Consequently, aspen sawdust was chosen based on its practical feasibility and prior studies [10,56]. The data collected were primarily descriptive, focusing on practical feeding outcomes rather than formal statistical analysis, yet they provide relevant insights into alternative roughage strategies.

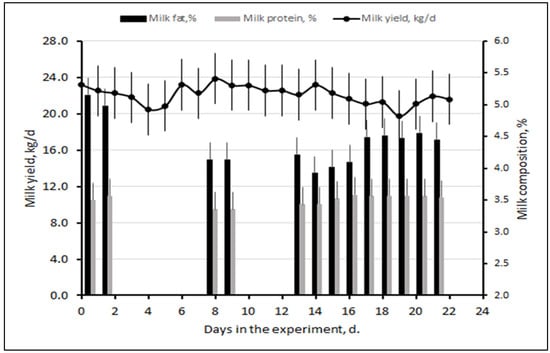

At the start, cows were fed 6 kg DM grass silage and 8.7 kg DM concentrate. By the end, intake shifted to 2.5 kg DM silage, 11.3 kg DM concentrate, and 5.4 kg DM sawdust. This indicates that sawdust accounted for approximately 27% of total dry matter intake. Adaptation to sawdust was rapid, with cows adjusting within 7–12 days, and no health issues or changes in water intake were observed. Milk yield decreased slightly from 23.9 to 21.9 kg, while milk fat and protein concentrations remained stable, indicating that rumen function was maintained. When silage provision was reduced further, minor decreases in intake and milk fat were corrected by gradually increasing silage, emphasizing the need for a baseline level of roughage (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Average milk yield and fat and protein content of milk on the test days.

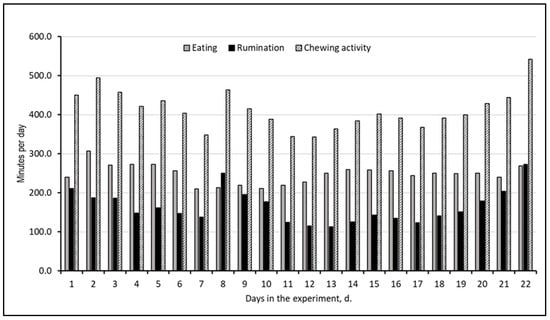

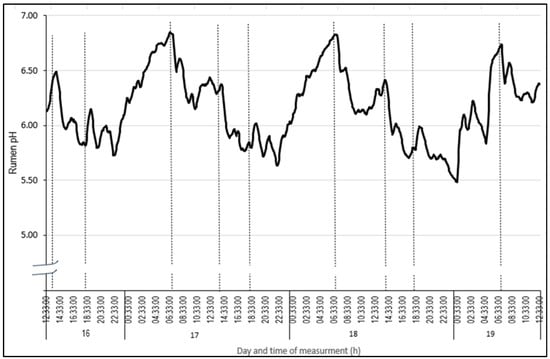

Figure 6 shows the average times for rumination, eating, and chewing observed during the test period. Chewing and rumination times reflected the reduced fiber content of sawdust compared to grass silage. With reported chewing times of 60 min/kg DM for silage and 4 min/kg DM for concentrate [57], the use of sawdust resulted in an average daily chewing time of about 350 min. Of this, sawdust contributed roughly 150 min, substantially less than the chewing time typically associated with silage. Larger particle sawdust introduced in the final two days increased rumination time, highlighting the importance of particle size for feed effectiveness and rumen health. Rumen pH measurements showed that nutrient digestion remained stable despite limited silage provision (Figure 7), with sawdust supporting normal rumen function. Generally, aspen sawdust can replace a substantial portion of grass silage in the diets of low- to moderate-yielding dairy cows without negatively affecting milk production, composition, or cow health, provided that a minimum level of structured forage is maintained. These observations align with previous reports [8,10] and emphasize the practical feasibility of sawdust as an alternative feed, particularly when conventional roughage is scarce or costly. The findings highlight that particle size, fiber content, and maintenance of baseline roughage are critical factors for successful incorporation of sawdust into diets.

Figure 6.

Average rumination, eating and total chewing activity.

Figure 7.

Rumen pH of one of the cows measured continuously for 3 days (i.e., mid-day of day 16 to mid-day of day 19) using a pH probe. Vertical dotted lines represent approximate feed pushing time points as described in Section 2.

4. Conclusions

The feeding value of birch sawdust is strongly influenced by processing methods. Steam-explosion treatment substantially improves digestibility and in vitro fermentability, whereas subsequent alkali treatment provides limited additional benefits. Residual carbohydrate availability and cell wall accessibility appear to be the main factors determining degradability. Both in vivo trials with sheep and preliminary acceptability tests with dairy cows indicate that ruminants can consume sawdust as a component of their diet without apparent refusal. However, due to the small scale and absence of standardized conditions in the cow trial, effects on milk production and composition cannot be conclusively determined. Further research is warranted to optimize the nutritive value of sawdust and other wood-based feedstuffs and to evaluate their role in sustainable ruminant production systems under varying climatic, economic, and political conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.P. and A.K.; Data curation, S.A.Y. and E.P.; Formal analysis, S.A.Y., E.P., L.M.H. and A.K.; Funding acquisition, E.P. and A.K.; Investigation, E.P., L.M.H. and A.K.; Methodology, E.P., L.M.H. and A.K.; Project administration, E.P. and A.K.; Resources, E.P. and A.K.; Software, S.A.Y., L.M.H. and A.K.; Supervision, A.K.; Validation, S.A.Y. and A.K.; Visualization, S.A.Y. and A.K.; Writing—original draft, S.A.Y.; Writing—review & editing, S.A.Y., E.P. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Innovasjon Norge funded this research (Ref. no: 2019/114236) in collaboration with Norgesfor AS, Strand Unikorn AS, and Glommen Technology AS (Elverum, Norway).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal procedures were conducted at the Senter for Husdyrforsøk, Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU), an animal research facility approved by the Norwegian Animal Research Authority. The in vitro and in sacco experiments involving rumen-cannulated cows were performed in accordance with Norwegian animal welfare legislation and were authorized by the Norwegian Research Authority (FOTS-ID 18/256940). The in vivo experiments using castrated rams followed standard methods within the Nordic Feed Evaluation System [27] and complied with national regulations on animal experimentation.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset will be available upon request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

Glommen Technology provided the steam-exploded birch sawdust. We would like to thank O. M. Harstad for his contribution to the dairy cow sawdust feeding experiment. S.A.Y. is a student at NMBU supported by the project “Institutional Collaboration Program Between Hawassa and Mekelle Universities of Ethiopia and the Norwegian University of Life Sciences” (ICP-V project funded by the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Addis Abeba, Ethiopia). A.K. also acknowledges support from the ICP-V project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. World Livestock: Transforming the Livestock Sector through the Sustainable Development Goals; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rinne, M.; Kautto, O.; Kuoppala, K.; Ahvenjärvi, S.; Willför, S.; Kitunen, V.; Ilvesniemi, H.; Sormunen-Cristian, R. Digestion of wood-based hemicellulose extracts as screened by in vitro gas production method and verified in vivo using sheep. Agric. Food Sci. 2016, 25, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin, K.A. Invited review: Current perspectives on eating and rumination activity in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4762–4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halmemies-Beauchet-Filleau, A.; Rinne, M.; Lamminen, M.; Mapato, C.; Ampapon, T.; Wanapat, M.; Vanhatalo, A. Alternative and novel feeds for ruminants: Nutritive value, product quality, and environmental aspects. Animal 2018, 12, s295–s309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forest Europe. State of Europe’s Forests 2015; Forest Europe: Madrid, Spain, 2015; Available online: https://foresteurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/soef_21_12_2015.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Eurostat. Forests, Forestry and Logging Statistics, 2023; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2023; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Baker, A.J.; Millett, M.A.; Satter, L.D. Wood and wood-based residues in animal feeds. ACS Symp. Ser. 1975, 10, 75–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöström, E. Wood Chemistry: Fundamentals and Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993; 293p. [Google Scholar]

- Satter, L.D.; Lang, R.L.; Baker, A.J.; Millett, M.A. Value of aspen sawdust as a roughage replacement in high-concentrate dairy rations. J. Dairy Sci. 1973, 56, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.R.; Baek, Y.C.; Jang, S.S.; Oh, Y.K.; Lee, S.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Park, K.K. Nutritional value and in situ degradability of oak wood roughage and its feeding effects on growth performance and behavior of Hanwoo steers during the early fattening period. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 33, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Leach, K.; Rinne, M.; Kuoppala, K.; Padel, S. Integrating willow-based bioenergy and organic dairy production: The role of tree fodder for feed supplementation. VTI Agric. For. Res. 2012, 394–397. [Google Scholar]

- Millett, M.A.; Baker, A.J.; Satter, L.D. Physical and chemical pretreatments for enhancing cellulose saccharification. Biotechnol. Bioeng. Symp. 1976, 6, 125–153. [Google Scholar]

- Sundstøl, F. Ammonia treatment of straw: Methods for treatment and feeding experience in Norway. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1984, 10, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielhop, T.; Amgarten, J.; Rudolf von Rohr, P.; Studer, M.H. Steam explosion pretreatment of softwood: The effect of the explosive decompression on enzymatic digestibility. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, M.; Kumar, R.; Karimi, K. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass. In Lignocellulose-Based Bioproducts; Karimi, K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 85–154. [Google Scholar]

- Castoldi, R.; Bracht, A.; de Morais, G.R.; Baesso, M.L.; Correa, R.C.G.; Peralta, R.A.; Moreira, R.F.P.M.; Polizeli, M.L.T.M.; de Souza, C.G.M.; Peralta, R.M. Biological pretreatment of Eucalyptus grandis sawdust with white-rot fungi: Study of degradation patterns and saccharification kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 258, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeper, A.; Ekmay, R.; Knobloch, S.; Skírnisdóttir, S.; Varunjikar, M.; Dubois, M.; Smárason, B.Ö.; Árnason, J.; Koppe, W.; Benhaïm, D. Torula yeast in the diet of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and the impact on growth performance and gut microbiome. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.; Sterten, H.; Steinhoff, F.S.; Mydland, L.T.; Øverland, M. Cyberlindnera jadinii yeast as a protein source for broiler chickens: Effects on growth performance and digestive function from hatching to 30 days of age. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 3168–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, A.; Tauson, A.-H.; Matthiesen, C.F.; Mydland, L.T.; Øverland, M. Cyberlindnera jadinii yeast as a protein source for growing pigs: Effects on protein and energy metabolism. Livest. Sci. 2020, 231, 103855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidane, A.; Vhile, S.G.; Ferneborg, S.; Skeie, S.; Olsen, M.A.; Mydland, L.T.; Øverland, M.; Prestløkken, E. Cyberlindnera jadinii yeast as a protein source in early- to mid-lactation dairy cow diets: Effects on feed intake, ruminal fermentation, and milk production. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 2343–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivekanand, V.; Olsen, E.F.; Eijsink, V.G.H.; Horn, S.J. Effect of different steam explosion conditions on methane potential and enzymatic saccharification of birch. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 127, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.H.F.; Kadic, A.; Chylenski, P.; Várnai, A.; Bengtsson, O.; Lidén, G.; Eijsink, V.G.H.; Horn, S.J. Demonstration-scale enzymatic saccharification of sulfite-pulped spruce with addition of hydrogen peroxide for LPMO activation. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2020, 14, 734–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapeña, D.; Olsen, P.M.; Arntzen, M.Ø.; Kosa, G.; Passoth, V.; Eijsink, V.G.H.; Horn, S.J. Spruce sugars and poultry hydrolysate as growth medium in repeated fed-batch fermentation processes for production of yeast biomass. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 43, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestløkken, E.; Harstad, O.M. Wood products as emergency feed for ruminants. In Proceedings of the 10th Nordic Feed Science Conference, Uppsala, Sweden, 11–12 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kidane, A.; Hval, L.M.; Prestlølcken, E. Feeding value of processed birch measured in vitro, in sacco and in vivo. In Proceedings of the 11th Nordic Feed Science Conference, Uppsala, Sweden, 25–26 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- NorFor. NorFor—The Nordic Feed Evaluation System; Volden, H., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 16th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Arlington, VA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B. Analysis of Forages and Fibrous Foods; AS 613 Manual; Department of Animal Science, Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Goering, H.K.; Van Soest, P.J. Forage Fiber Analyses (Apparatus, Reagents, Procedures, and Some Applications); Agriculture Handbook No. 379; USDA-ARS: Washington, DC, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Åkerlind, M.; Weisbjerg, M.; Eriksson, T.; Tøgersen, R.; Udén, P.; Ólafsson, B.; Harstad, O. Feed analyses and digestion methods. In NorFor: The Nordic Feed Evaluation System, 1st ed.; Volden, H., Ed.; EAAP Publication No. 130; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ANKOM Technology. ANKOMRF Gas Production System—Operator’s Manual; ANKOM Technology: Fairport, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.ankom.com/sites/default/files/2024-09/RF_Manual_090424.pdf?srsltid=AfmBOoqx4fuVOo07G1_v43VvpA-FlsdIXE_Ugx5e3a5E-6D_3JIzp3_y (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Groot, J.C.; Cone, J.W.; Williams, B.A.; Debersaques, F.M.; Lantinga, E.A. Multiphasic analysis of gas production kinetics for in vitro fermentation of ruminant feeds. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1996, 64, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørskov, E.R.; McDonald, I. The estimation of protein degradability in the rumen from incubation measurements weighted according to rate of passage. J. Agric. Sci. 1979, 92, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EAAP (European Association for Animal Production). Methods for Determination of Digestibility Coefficients of Feeds for Ruminants; Report No. 1 from the Study Commission on Animal Nutrition; Mariendals Boktrykkeri A/S: Gjøvik, Norway, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Q.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, W. Effects of steam explosion on lignocellulosic degradation of and methane production from corn stover by a co-cultured anaerobic fungus and methanogen. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 290, 121796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Z.B.; Liu, R.H.; Yu, H.Q.; Chen, H.Z.; Yu, B.; Harada, H.; Li, Y.Y. Enhanced anaerobic ruminal degradation of bulrush through steam explosion pretreatment. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 5899–5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.G.; Li, G.D.; Zheng, N.; Wang, J.Q.; Yu, Z.T. Steam explosion enhances digestibility and fermentation of corn stover by facilitating ruminal microbial colonization. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 253, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Suhag, M.; Dhaka, A. Augmented digestion of lignocellulose by steam explosion, acid and alkaline pretreatment methods: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 117, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinne, M.; Kuoppala, K. Feeds for ruminants from forests? In Proceedings of the 10th Nordic Feed Science Conference; Report 302; SLU: Uppsala, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M.G. Review article: The alkali treatment of straws. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1977, 2, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, P.C. Ash content of forages. Focus Forage 2005, 7, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Khattab, H.M.; Gado, H.; Salem, A.Z.M.; Díaz, L.M.; El-Sayed, M.; Kholif, A.; Elshewy, A.; Kholif, A. Chemical composition and in vitro digestibility of Pleurotus ostreatus spent rice straw. Anim. Nutr. Feed Technol. 2013, 13, 507–516. [Google Scholar]

- Humer, E.; Zebeli, Q. Grains in ruminant feeding and potentials to enhance their nutritive and health value by chemical processing: Review article. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2017, 226, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Lu, Y.; An, N.; Zhu, W.; Li, M.; Gao, M.; Wang, X.; Wu, C.; Wang, Y. Pretreatment technologies for lignocellulosic biomass: Research progress, mechanisms, and prospects. BioResources 2025, 20, 4897–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.J. Nutritional Ecology of the Ruminant, 2nd ed.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, J.L.; Harbaum-Piayda, B.; Schwarz, K. Phenolic compounds from hydrolyzed and extracted fiber-rich by-products. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherzadeh, M.J.; Karimi, K. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic wastes to improve ethanol and biogas production: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2008, 9, 1621–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Kuoppala, K.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D.; Leach, K.; Rinne, M. Nutritional and fermentation quality of ensiled willow from an integrated feed and bioenergy agroforestry system in the UK. Suom. Maatal. Seuran Tied. 2014, 30, 1–9. Available online: https://journal.fi/smst/article/view/75342/36788 (accessed on 13 January 2026). [CrossRef]

- Binder, J.B.; Raines, R.T. Fermentable sugars by chemical hydrolysis of biomass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 4516–4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, A.T.W.M.; Zeeman, G. Pretreatments to enhance the digestibility of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundstøl, F.; Hove, K.; Volden, H. Ammonia treatment of straw. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1978, 3, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kamstra, L.D.; Singh, M.; Embry, L.B.; Peterson, L. Aspen material as a feed ingredient in ruminant rations. In South Dakota Cattle Feeders Field Day Proceedings and Research Reports; South Dakota State University: Brookings, SD, USA, 1976; Paper 9; Available online: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/sd_cattlefeed_1976/9 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Nørgaard, P.; Nadeau, E.; Randby, Å.; Volden, H. Chewing index system for predicting physical structure of the diet. In NorFor: The Nordic Feed Evaluation System, 1st ed.; Volden, H., Ed.; EAAP Publication No. 130; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.