Abstract

The effects of pelleting a total mixed ration (TMR) for dairy sheep were investigated in an experiment involving 24 lactating Assaf ewes, which were assigned to two groups and fed the same TMR ad libitum, offered either in pelleted (PTMR group, n = 12) or in unpelleted form (CTMR group, n = 12). The experiment lasted 28 days, during which feed intake, eating behavior (including meal frequency and size, meal duration, eating rate, between-meal interval), and milk yield were recorded daily. Body weight (BW) was recorded on days 1 and 28 and milk samples were collected on days 1, 8, 15, 22 and 28 for milk composition analysis. Blood acid-base status was determined at the beginning and at the end of the trial. Ewes fed the CTMR diet exhibited (p < 0.05) a higher meal frequency and longer meal duration, along with a smaller meal size and slower eating rate. However, feed intake in this group was less than that in ewes fed PTMR only during the final two weeks of the experimental period. Total eating time was also longer (p < 0.001) in the CTMR group, whereas the average time between meals was shorter (p < 0.002). No differences (p > 0.05) were observed between dietary treatments in blood acid-base status, milk yield or milk composition. However, a diet x day interaction (p < 0.05) was detected for milk yield, as during the last 2 weeks of the experimental period the ewes fed the PTMR yielded more milk than those fed the CTMR. Feed conversion ratio did not differ between groups (p > 0.05), but body weight loss was greater in ewes fed the CTMR diet (−3.00 vs. −0.58 kg; p < 0.05). A trend toward improved feed efficiency was observed in the PTMR group when calculated based on milk yield corrected for that theoretically derived from the mobilization of body reserves (1.98 vs. 1.41 g DMI/kg milk; p = 0.077), with estimated contributions from body reserves of 485 g/day in the CTMR group and 70 g/day in the PTMR group. In conclusion, the use of pelleted total mixed rations in high-yielding dairy ewes enhances feed intake, feed efficiency, milk yield, and energy balance without adversely affecting milk composition or animal health in the short term.

1. Introduction

Dairy sheep farming is largely concentrated within the Mediterranean region, accounting for 45% of world ewe milk production. These systems are economic drivers of rural zones, providing job opportunities where alternatives are limited [1]. However, to ensure their long-term economic and environmental sustainability, it is crucial to implement useful measures, including those that allow for a more efficient use of resources [2].

Intensive dairy sheep production systems in Spain typically rely on indoor feeding strategies, which involve either the separate provision of rationed forage and concentrate or their combination in non-pelleted total mixed rations (TMR) [3]. With both feeding strategies sheep can consume dietary components selectively according to their individual preferences [4,5,6]. By this selective consumption, small ruminants can alter the composition of the TMR within the first two hours after its delivery, potentially compromising the nutritional quality of the feed remaining in the trough [7]. It is well known that animals differ markedly both among individuals and over time in their feed selection. Depending on factors such as feeding timing and frequency, feed bunk design, and available space, feeding behavior may vary, with animals preferentially selecting more palatable or nutrient-dense feed components. This selective feeding can reduce overall intake and lead to dietary imbalances [8,9,10]. Selective sorting and consumption of specific dietary components may lead to an excessive intake of rapidly fermentable carbohydrates, thereby compromising rumen health and resulting in unfavorable alterations in milk composition. Competition among animals within the herd implies that those accessing feed later may encounter rations of reduced quality, as higher-quality fractions may have already been consumed by animals that had fed earlier [7,11]. Pelleting total mixed rations (TMR) offers a potential strategy to prevent feed sorting, thereby ensuring that each bite delivers a nutritionally balanced diet. Pelleting feed for ruminants has been studied since the 1960s in dairy cows [12,13] and, subsequently, in dairy sheep [14,15]. Some of these early studies, along with more recent research, have raised concerns because pelleting involves a substantial reduction in forage particle size, which can negatively impact ruminal fermentation and feed intake, and may lead to milk fat depression [16,17,18]. However, such adverse effects have not been consistently observed, either in dairy cows [12,13] or in dairy sheep [15]. Some nutritional strategies have been proposed to alleviate these potential adverse effects of feeding pelleted TMR, such as balancing the ratio of dietary fiber to non-structural carbohydrates [19,20,21], using different pellet sizes allowing for the inclusion of coarser forage [22] or supplementing a yeast culture as a feed additive [23]. The variability in results suggests the influence of several modulating factors, including animal-related aspects such as the level of intake, as well as diet-related characteristics such as pellet physical properties, forage-to-concentrate ratio, type of forage or concentrate used, protein content, and the inclusion of feed additives that may modulate ruminal fermentation [13,23,24,25,26]. Particle size and the proportions of fibrous and non-structural carbohydrates seem to be the most influential factors [21].

The limited availability of information (combined with concerns about potential risks such as ruminal acidosis and milk fat depression, as well as the additional cost associated with pelleting) has likely limited the widespread adoption of feeding pelleted diets in some ruminant farming systems [27,28]. Although pelleted total mixed rations (TMR) are widely used in dairy and beef cattle production [6,28], their application in small ruminants remains considerably more limited. In sheep, some studies have addressed their use in growing lambs [18,19,28,29,30,31]; however, virtually no information is available regarding dairy sheep, particularly high-yielding ewes. However, the increasing availability of cost-effective automated feed distribution technologies, the growing need for precision feeding systems, and labor shortages in the livestock sector are driving renewed interest in pelleted feeding strategies [32,33]. These developments highlight the need for continued research aimed at optimizing the use of pelleted diets while minimizing the associated risks previously described. Genetically improved dairy ewes exhibit high nutritional requirements, necessitating high-concentrate diets and elevated dry matter intakes (exceeding 3.5% of body weight) to sustain peak lactation. However, when fed a conventional TMR, sheep may selectively consume palatable, less fibrous components. Such sorting behavior increases the intake of readily fermentable carbohydrates, thereby exacerbating the risk of ruminal acidosis. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have compared unpelleted and pelleted TMR of identical composition to evaluate their capacity for supporting high milk production while mitigating acidogenic risks. In most existing literature, TMRs are usually formulated with highly fermentable ingredients, and pelleting is accompanied by changes in dietary formulation. Our hypothesis is that pelleting prevents feed sorting during ingestion and that the risk of acidosis can be alleviated by incorporating fibrous, non-acidogenic ingredients into the pelleted TMR. To rigorously test this hypothesis, it is essential to compare pelleted and unpelleted TMR of identical nutritional composition. In this context, the present study was designed to evaluate the effects of pelleting a standard total mixed ration for high-producing dairy sheep, with particular attention to how the reduction in feed particle size associated with pelleting may affect feeding behavior or zootechnical performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Ethics

The experiment was compliant with the Spanish legislation (Royal Decree 1201/2005) related to the protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes. The experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Instituto de Ganadería de Montaña (CSIC, Madrid, Spain) with protocol number 100102/2021-6.

2.2. Animals and Experimental Diets

Twenty-four high yielding lactating Assaf ewes were assigned to two experimental groups. All ewes were fed the same TMR (Table 1) ad libitum, offered to 12 of the ewes as an unpelleted TMR (control or CTMR group; n = 12) and to the other 12 ewes in pelleted form (PTMR group; n = 12). Experimental groups were balanced according to body weight (BW, average 77.0 ± 2.37 kg), number of lactation (1.5 ± 0.25), days in milk (DIM 48 ± 1.6 days) and milk production (2608 ± 160.4 g/d).

Table 1.

Ingredients and chemical composition of the diets (CTMR: control total mixed ration diet; PTMR: pelleted total mixed ration) used during the experimental period.

Composition of the experimental diets (CTMR and PTMR) is shown in Table 1. The mixed control ration was formulated and prepared combining all the ingredients in a 22 m3-capacity horizontal TMR mixer (unifeed) wagon equipped with blades (Lombarte model MSE-322 PI stationery, Binéfar, Spain). The forages (dehydrated alfalfa and pre-chopped barley straw) were added first and mixed for 10 min. Subsequently, the concentrates and the other ingredients were incorporated, stirring all components and mixing continued for an additional 5 min to ensure homogeneity of the final diet. A single batch of 3000 kg of fresh TMR was prepared, sufficient for the entire experimental period. The TMR was stored in a cool, dry, and well-ventilated area within a barn and was protected from environmental exposure.

The ingredients included in the PTMR of one group were ground using a sieve with a screen diameter of 2 mm using a 100-horsepower hammermill (VRE model, Rosal® Instalaciones Agroindustriales, Santa Perpètua de Mogoda, Barcelona, Spain). After mixing the PTMR was steam-conditioned (70 °C temperature and 312 kPa of conditioning steam pressure) and then extruded through a 6 mm (hole diameter) × 44 mm (thickness) die using a 150-horsepower pellet mill (PVR model, MABRIK S.A.U., Barberà del Vallès, Barcelona, Spain). The die thickness to hole diameter ratio was 7.3. Pellet dimensions were 3.7 mm in diameter and 14.0 mm in length (SE = 1.44), with a bulk density of 685 kg/m3 (SE 2.73) and a Kahl pellet hardness of 7.4 kg (1.12).

2.3. Experimental Procedures

All sheep were managed similarly and maintained under the same feeding system from parturition until 10 days before the beginning of the experimental period, receiving ad libitum the control TMR. On day −10 (10 days before the beginning of the trial), milk yield and BW of each ewe were recorded and animals were assigned to the experimental treatments (CTMR vs. PTMR). During all the experiment (including the adaptation and measurement periods), the ewes assigned to the control group received the CTMR ad libitum. During the preliminary adaptation period (10 days), ewes assigned to the PTMR group were gradually transitioned from the control diet to the pelleted TMR, with the proportion of PTMR progressively increased until it constituted 100% of the diet.

The experimental period lasted 28 days. Individual feed intake and feeding behavior (meal frequency, meal size, and meal duration) were recorded daily using automatic feeders (Agrolaval S.L., Gijón, Asturias, Spain). The feeders identified each ewe via radio-frequency technology and automatically registered the start time (at which the sheep accessed the feeder), duration, and size of each meal. Two automatic feeders were assigned to every 6 ewes, providing an estimated average availability of 8 h per ewe per day. To minimize competition at the automatic feeders, the ewes in each experimental group were divided into two pens. The area occupied by each pen was 24 m2, was equipped with two automatic feeders, and housed six ewes. The four pens were located within the same barn to ensure uniform environmental conditions.

Feeders were refilled daily after refusals were removed. Samples of the offered feed (TMR) and refusals were collected daily to determine DM content.

Daily feed intake and eating behavior parameters were calculated for each ewe and day, considering both the entire 24 h period and three 8 h periods within the day (morning from 08:00 to 16:00 h, evening from 16:00 to 24:00 h, and overnight from 24:00 to 08:00 h). A minimum interval of 5 min between successive visits to the feeder was used as the criterion to define independent feeding events, corresponding to a single meal. To determine whether daily feed intake resulted from a few large meals or numerous small meals, the distribution of meal sizes was further examined by classifying meals into three categories based on their relative size: small meals (<0.33 of the largest daily meal), medium meals (0.33–0.66 of the largest daily meal), and large meals (>0.66 of the largest daily meal).

At the beginning (d 1) and end (d 28) of the experimental period, body weight (BW) was recorded for each ewe immediately after milking, and blood samples were collected by jugular venipuncture following a one-hour feed restriction to ensure that all ewes were in a comparable postprandial state. Blood samples were drawn into 10 mL Vacutainer® tubes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) containing sodium heparin and were immediately transported on ice to the laboratory for determination of acid–base status within 2 h of collection.

Ewes were machine milked once daily at 08:00 h using a 1 × 10 low-line Casse milking parlor equipped with 10 stalls and 2 milking clusters. To ensure a consistent interval between consecutive milkings, the milking order was kept uniform throughout the entire experimental period. Accordingly, the CTMR ewes were milked first, followed by those allocated to the PTMR group. The milking machine (Alfa-Laval Iberia S.A., Madrid, Spain) operated at 120 pulsations per minute with a 50:50 pulsation ratio and a vacuum pressure of 36 kPa. The standard milking routine included teat cleaning, machine stripping (i.e., massaging the udder before teat cup removal), and post-milking teat dipping (Alfadine, DeLaval, Barcelona, Spain). Individual milk yield was recorded daily, and milk samples were collected on d 1, 8, 15, 22, and 28 for compositional analysis. Milk samples of approximately 100 mL were collected for each ewe, preserved with a broad-spectrum antimicrobial tablet (Bronopol; Broad Spectrum Microtabs II, Bentley Instruments EU, Maroeuil, France), and stored at 4 °C until laboratory analysis, which was performed within 24 h of sampling.

2.4. Particle Size Distribution

The particle size distribution of both diets was determined by dry sieving analysis [34,35], using an Endecotts test sieve shaker equipped with electromagnetic three-dimensional sieving motion (Octagon Digital model, Endecotts Ltd., London, UK). Sieves with progressively smaller mesh sizes were arranged in the mechanical sieve shaker. Samples of the PTMR diet were soaked in tap water for 30 min prior to sieving to allow pellet disintegration and were subsequently dried at 50 °C for 48 h in a forced-air oven. Control diet samples were also dried under the same conditions before sieving. For each test, a 100 g sample was used, and each TMR was analyzed in triplicate. Each sample was sieved for 5 min using an intermittent cycle consisting of 5 s of vibration (amplitude set at 2.64 mm) followed by 2 s without vibration. Results are presented in Table 1.

2.5. Chemical Analyses

Feed samples were analyzed for dry matter (DM) (ISO 6496 [36]), ash (ISO 5984 [37]), and crude protein (ISO 5893-2 [38]). Neutral and acid detergent fiber were determined as described by Van Soest et al. [39], using a fiber analyzer (Ankom Technology Corp., Macedon, NY, USA). Neutral detergent fiber was assayed with sodium sulfite and α-amylase and expressed with residual ash. The content of crude fat was determined by the Ankom filter bag technology [40].

Milk fat, protein, lactose, total solids, urea, acetone, and β-hydroxybutyrate concentrations were determined by automatic infrared spectrophotometry (MilkoScan FT6000; Foss Electric, Hillerød, Denmark). Somatic cell count was measured using an automated cell counter (Fossomatic 5000; Foss Electric, Hillerød, Denmark). Energy-corrected milk yield (ECM) was calculated according to Bocquier et al. [41] as follows: ECM (g/d) = milk yield (g/d) × (0.071 × %fat + 0.043 × %protein + 0.2224).

Blood samples (as collected) were analyzed for parameters related to acid–base balance, including pH, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2; mmHg), bicarbonate concentration (HCO3−; mmol/L), and anion gap (mmol/L), using a Stat Profile pHOx Plus analyzer (Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.6. Calculations and Statistical Analysis

Twelve lactating ewes were allocated to each experimental group, as a minimum sample size of 10 animals was previously determined to provide 80% statistical power, based on the standard deviation of the productive parameters measured (i.e., dry matter intake, milk yield, and milk composition).

Feed conversion ratio (FCR) was calculated as the ratio of average daily DM intake (DMI) to average daily milk yield. The theoretical daily milk production derived from the energy supplied by BW changes was estimated according to the guidelines of the Agricultural and Food Research Council [42]. A corrected feed conversion ratio (FCRcorrected) was then obtained by dividing daily feed intake by daily milk yield after subtracting the estimated milk production attributed to mobilization of body reserves. Residual feed intake was estimated as the difference between observed and expected feed intake. The expected feed intake was estimated from multiple linear regression, including the animal’s average BW, changes in BW, and corrected milk production as explanatory variables in the model.

Data normality and homogeneity of variances were assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. Variables including BW, BW change, and FCR were analyzed by one-way ANOVA using the GLM procedure of SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), with diet included as a fixed effect and animal nested within diet as the error term. Feed intake, eating behavior parameters, and milk yield data were analyzed as repeated measures using the MIXED procedure of SAS 9.1.3. Milk composition and blood acid–base parameters were also analyzed as repeated measures but based on data collected on 5 and 2 sampling days, respectively, instead of 28 days. The model included diet, day, and their interaction as fixed effects, with animal nested within diet as the error term for testing diet effects. The residual error term was used to test day and diet × day effects. Different covariance structures (compound symmetry, unstructured, first-order and heterogeneous autoregressive) were evaluated selecting the one with the lowest Schwarz Bayesian information criteria. Least squares means (LSMEANS) and pairwise differences (PDIFF) were used to compare means. Statistical significance was declared at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Intake and Feeding Behavior

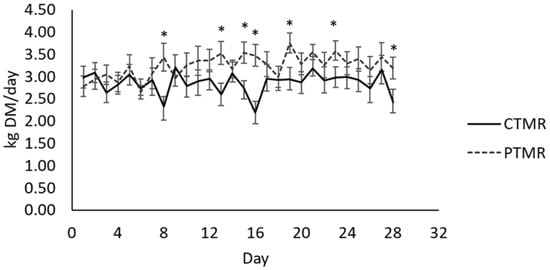

No significant (p = 0.267) differences between experimental diets were found for total daily feed intake (Table 2). However, a diet × day interaction was detected (p < 0.001), as feed intake was similar between groups during the first two weeks, but was subsequently greater in ewes fed the PMTR than in those fed the CTMR on most days during the final two weeks (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Effect of pelleting the total mixed ration (CTMR: unpelleted TMR; PTMR: pelleted TMR) on feed intake and eating behavior in lactating ewes.

Figure 1.

Dry matter intake along the experimental period in ewes receiving an unpelleted (CTMR) or pelleted (PTMR) total mixed ration (*: differences between dietary treatments were significant at p < 0.05).

Diet type significantly influenced feeding behavior (Table 2), with ewes offered the CTMR diet exhibiting a higher meal frequency and longer meal duration, but smaller meal size and a slower eating rate (p < 0.05). It is noteworthy that, in both experimental groups, the majority of daily feed intake was derived from small and medium meals, which together accounted for approximately 75% of total intake (Table 2).

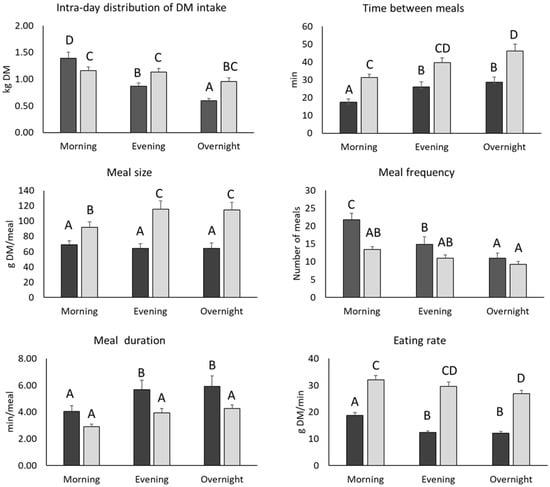

Feeding behavior varied throughout the day. During the morning period (08:00–16:00 h), the smaller meal size observed in ewes fed the CTMR diet was compensated by a higher meal frequency, resulting in a numerically greater total feed intake compared with those offered the PMTR diet (Figure 2). In the subsequent periods (16:00–24:00 h and 24:00–08:00 h), meal size in the CTMR group remained relatively constant, while meal frequency declined. Consequently, feed intake decreased substantially, representing 48.5%, 30.4%, and 21.1% of the total daily intake during the 08:00–16:00 h, 16:00–24:00 h, and 24:00–08:00 h intervals, respectively (Figure 2). In contrast, for ewes fed the PMTR diet, meal size increased after the morning period, whereas meal frequency decreased (Figure 2), leading to relatively minor variations in feed intake across the day (35.7%, 34.9%, and 29.4% of total daily intake during the 08:00–16:00 h, 16:00–24:00 h, and 24:00–08:00 h intervals, respectively) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Dry matter intake and feeding behavior at different intervals within a day in ewes receiving either unpelleted (CTMR  ) or pelleted (PTMR

) or pelleted (PTMR  ) total mixed rations (the three 8 h periods were morning 08:00–16:00 h, evening 16:00–24:00 h and overnight 24:00–08:00 h; A, B, C, D: bars with different letters are significantly different at p < 0.05).

) total mixed rations (the three 8 h periods were morning 08:00–16:00 h, evening 16:00–24:00 h and overnight 24:00–08:00 h; A, B, C, D: bars with different letters are significantly different at p < 0.05).

) or pelleted (PTMR

) or pelleted (PTMR  ) total mixed rations (the three 8 h periods were morning 08:00–16:00 h, evening 16:00–24:00 h and overnight 24:00–08:00 h; A, B, C, D: bars with different letters are significantly different at p < 0.05).

) total mixed rations (the three 8 h periods were morning 08:00–16:00 h, evening 16:00–24:00 h and overnight 24:00–08:00 h; A, B, C, D: bars with different letters are significantly different at p < 0.05).

Total eating time was longer in ewes fed the CTMR diet (p < 0.001), whereas the interval between meals was shorter (p < 0.002) than with the PTMR. In both experimental groups, the time between meals was shorter (p < 0.05) during the morning period compared with subsequent intervals, but remained consistently longer in PMTR-fed ewes (CTMR: 17.5, 26.0, and 28.7 min at 08:00–16:00 h, 16:00–24:00 h, and 24:00–08:00 h, respectively; PMTR: 31.3, 39.5, and 46.1 min at 08:00–16:00 h, 16:00–24:00 h, and 24:00–08:00 h, respectively).

3.2. Blood Acid-Base Status

Mean values for blood acid-base parameters are shown in Table 3. There were not significant (p > 0.05) differences between experimental diets in any of the parameters evaluated. However, pH increased and pCO2 decreased (p < 0.05) from the beginning to the end of the trial in both experimental groups.

Table 3.

Effect of pelleting the total mixed ration (CTMR: unpelleted TMR; PTMR: pelleted TMR) on blood acid-base status.

3.3. Milk Yield and Composition

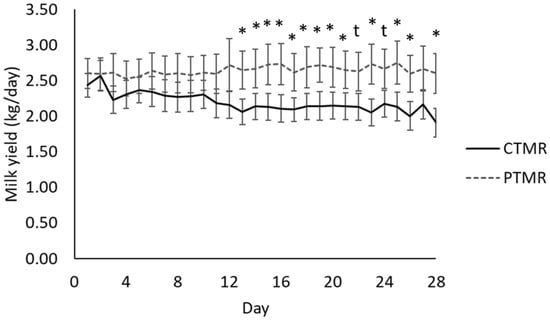

As shown in Table 4, no significant differences (p = 0.178) were observed between experimental groups for overall average milk yield over the 28-day experimental period. However, the diet x day interaction was significant, with milk yield being higher in ewes fed the PMTR than in those fed the CTMR on most days during the final two weeks (p < 0.05 on days 13 to 21, 23, 25, 26 and 28 of the study, and 0.05 < p < 0.10 on days 22 and 24) of the experimental period (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Effect of pelleting the total mixed ration (CTMR: unpelleted TMR; PTMR: pelleted TMR) on milk yield and composition.

Figure 3.

Milk yield along the experimental period in ewes receiving an unpelleted (CTMR) or pelleted (PTMR) total mixed ration (*: differences between dietary treatments were significant at p < 0.05; t: differences between dietary treatments tended to be significant at p < 0.10).

Milk composition was not affected (p > 0.05) by dietary treatments. Sampling day influenced (p < 0.05) total solids, fat and urea milk contents, but this effect was independent of dietary treatments.

3.4. Body Weight Changes and Feed Efficiency

At the beginning of the experimental trial, no significant differences in BW were observed (p > 0.05). However, by the conclusion of the experimental period, the differences exhibited a trend toward statistical significance (p = 0.056), with numerically lower values recorded in the ewes fed the CTMR (Table 5). Throughout the trial, sheep experienced a reduction in BW, and the magnitude of this BW change was greater (p = 0.02) in the CTMR group compared to the PTMR group.

Table 5.

Effect of pelleting the total mixed ration (CTMR: unpelleted TMR; PTMR: pelleted TMR) on body weight (BW) and feed conversion ratio (FCR).

Variations in intake among animals were highly correlated (R2 = 0.72; p < 0.001) with milk production, average BW, and change in BW during the trial. No differences (p > 0.704) in residual feed intake were observed between groups.

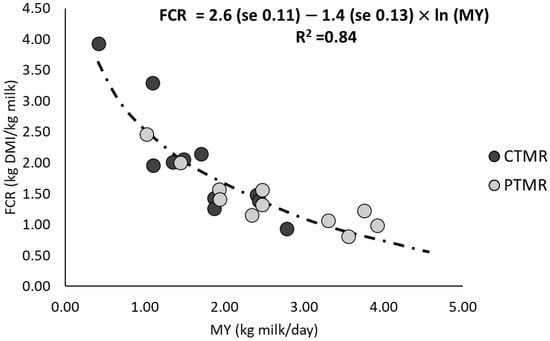

Regarding feed efficiency, no significant differences (p > 0.05) were detected between dietary treatments for the feed conversion ratio (FCR). Given the differences between groups in BW loss (suggesting body reserve mobilization), the FCR was subsequently adjusted using milk yield calculated after excluding that theoretically derived from the mobilization of body reserves (485 g milk/day for the CTMR vs. 70 g milk/day for PTMR). The difference between groups in this adjusted FCR showed a trend toward significance (p = 0.077). Furthermore, after a correction for the body weight loss, an inverse relationship was observed between FCR and milk yield (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Relationship between feed conversion ratio (FCR, kg dry matter intake/kg milk yield) and milk yield (MY, kg milk/day) in ewes fed with in ewes receiving an unpelleted (CTMR) or pelleted (PTMR) total mixed ration. FRC was estimated after accounting for milk production derived from the mobilization of body reserves. Dots (dark for CTMR and light for PTMR) represent the observed values, while the dotted line corresponds to the adjusted (i.e., fitted) curve of the equation relating FCR to MY.

4. Discussion

4.1. Intake and Eating Behavior

The 28-day experimental period was considered sufficient to evaluate the effects of dietary treatments (CTMR vs. PTMR), based on our previous experience and similar lactation studies conducted with high-yielding Assaf ewes. In addition, feed intake (Figure 1) and milk production (Figure 2) showed a rapid adaptation to both TMRs and a stable response pattern throughout the experimental period. These observations indicate that the duration of the study was adequate to capture meaningful and representative effects of the physical form of the TMR.

Feed intake in ewes fed the CTMR diet were within the ranges reported for Assaf ewes of similar characteristics and fed with unpelleted total mixed rations [43,44]. Likewise, the mean value for eating time (213 min/day) recorded in this group would be within the range of values reported for non-pelleted diets. Vega et al. [45] reported eating times of 154, 397 and 339 min/day when chopped alfalfa was offered once, twice a day or continuously. Eating times ranging from 180 to 336 min/day were observed in sheep fed hays of different quality or chopped at different particle length [46,47]. It should be noted that a higher forage-to-concentrate ratio in total mixed rations tends to increase chewing time [48,49], and therefore shorter eating times could be expected in the present experiment. Our study involved high-yielding dairy ewes after the peak of lactation, when the maximum feed intake capacity is reached, requiring longer eating times for ad libitum intake.

Several studies [45,50] have reported that total eating time decreased when pelleted diets were used, whereas total feed intake was increased, which is consistent with the results obtained in the present study. Likewise, the average eating time recorded for PTMR ewes (115 min/day) was comparable to that reported by Pulina et al. [51] in lactating ewes, using diets elaborated with different proportions of 2 types of pellets (normal concentrate pellets and high fiber pellets).

An increase in feed intake in sheep offered pelleted diets, relative to diets composed of the same ingredients provided in long form, has been reported in several studies [30,50,52]. In some of these investigations, pelleting slightly decreased feed digestibility [30,52], whereas in others digestibility was not affected [50] or was even enhanced [53]. Reduction in feed particle size through pelleting has been associated with an increased digesta passage rate [50], decreased rumen fill [30], and reduced rumination activity [53]. Taken together, these observations indicate a relationship between feed physical form, ruminal digesta retention, and voluntary feed intake.

In addition to differences in total eating time, the other eating behavior parameters were influenced by the type of diet. Fewer meals per day were recorded in sheep fed pelleted diets, but they were of shorter duration (min/meal) and larger size (g feed/meal) resulting in a higher eating rate (g feed/min). To the best of our knowledge, no studies have been published in milking ewes sheep evaluating the effect of pelleting total mixed rations on all parameters defining eating behavior, but Bermudez et al. [54] studied the effect of physiological status on several eating behavior parameters using complete pelleted diets and the values reported for meal frequency (34 meals/day), and meal size (97 g/day) during lactation period were similar to those observed in our study in ewes fed PTMR.

The faster eating rate and larger meal size in PTMR sheep were probably related to reduced mastication activity and filling effect of the diet. Chewing activity per g of feed increases as particle size increases because animals require more intensive mastication to swallow the feed bolus [46,55]. It has been suggested that chewing activity could modulate gut hormone release and may send signals to brain’s satiety centers and trigger meal cessation [56]. Furthermore, even after chewing during eating, the filling effect of digesta probably was also increased in ewes fed unpelleted diets, so that a smaller amount of feed would be required to induce distension of the reticulo-rumen and stimulate tension and mechanical receptors [57]. In fact, as feed and ruminal digesta particle size increases, rumination time increases, contributing to a reduction in total feed intake [50]. However, in the current experiment, the time between consecutive meals was longer in ewes fed the pelleted diet, suggesting that the larger meal size in PTMR ewes could activate postruminal and postabsorptive metabolic mechanisms [57,58,59,60], delaying the onset of hunger sensation and the start of the next meal. The main mechanisms involved include increased intestinal nutrient flux (increasing plasma concentrations of key energy metabolites), enhanced hepatic oxidation of absorbed energy-yielding substrates, stimulation of gastrointestinal and pancreatic satiety hormones, central metabolic sensing of absorbed nutrients, and osmotic feedback originating from the small intestine [57,58,59,60].

It is interesting to analyze the differences in eating behavior throughout the day. Thus, when the intake pattern was compared in 3 intervals within the day (morning: 08:00–16:00 h.; afternoon: 16:00–24:00 h; overnight: 24:00–08:00 h), it was observed that the total intake was similar in the three intervals in sheep fed the PTMR, although the eating behavior was slightly modified, decreasing the number of meals, but increasing the duration and size of each meal and the time between meals throughout the day. In contrast, the size of each meal was reduced but the time between meals was increased throughout the day in ewes fed the CTMR. As a result, intake varied significantly between periods, with the majority of intake occurring in the morning (08:00–16:00 h). In fact, during this morning interval, the intake when ewes were fed CTMR was slightly increased compared with those fed the PTMR diet (167 vs. 138 g of DM/h).

The more evident variation in eating behavior among intervals observed during the day in ewes fed the CTMR diet could be related to a more pronounced diet-selection (sorting of and choosing the most palatable components of the TMR) activity attributable to the preference for specific ingredients. The animals may have been more selective during the first hours after feed distribution in the morning, changing the diet consumed throughout the day as the composition of the feed remaining in the feeder varied. In the present study, the composition of the feed in the feeder was not monitored at the beginning of each 8 h interval as this could disturb the natural eating behavior of sheep, and unfortunately this hypothesis cannot be corroborated. However, it has been reported that sheep can modify the composition of the total mixed ration in the feeder within the first 2 h after feed distribution [7]. The change in eating behavior throughout the day observed in ewes fed the CTMR could be due also to innate behavior related to changes in activity associated with circadian rhythms [61,62] and not only to changes in the composition of the diet consumed. In fact, a similar behavior to that observed in sheep fed the CTMR, with a significant reduction in intake during the night period, has also been reported in sheep using a complete pelleted feed [54]. In any case, it should be kept in mind that effects of circadian rhythms on feeding behavior can be affected by the level of production, since feeding behavior must be aligned with the energy demand of the animals [63,64].

4.2. Blood Acid-Base Status

Bicarbonate enters the rumen primarily through salivary secretion during eating and rumination, as well as via anion exchange associated with volatile fatty acid (VFA) absorption, both of which play a critical role in buffering ruminal pH [65,66]. When feed particle size is reduced, ruminal fermentation rate is increased and feed saliva secretion is reduced [18,65,66,67,68]. Consequently, decreases in ruminal pH and blood bicarbonate (HCO3−) concentration would be expected in ewes fed the pelleted total mixed ration (PTMR). Similarly, a compensatory reduction in the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) would be anticipated to maintain blood pH homeostasis and prevent metabolic acidosis [69]. However, no significant differences were observed between experimental groups in any of the measured acid-base parameters. Furthermore, feed intake was not depressed in ewes fed the PTMR, and day-to-day variability in feed intake -an indicator of subclinical acidosis [66]- was comparable between treatments, with coefficients of variation of 13 ± 3.4% and 11 ± 4.0% for the conventional total mixed ration (CTMR) and PTMR groups, respectively. Feed intake, milk production and composition (fat-to-protein ratio), and blood acid-base status were used in this study as indirect indicators of the possible occurrence of subacute ruminal acidosis. The validity of these indicators has been well documented in previous studies [70,71,72]; however, their interpretation remains constrained in the absence of direct measurements, such as continuous ruminal pH monitoring [73,74].

The absence of differences in acid-base status may be attributed, at least in part, to the inclusion of bicarbonate in the experimental diets [75]. Nonetheless, other compensatory mechanisms cannot be excluded. For instance, pelleting has been reported to increase the passage rate of the liquid phase of digesta [45], potentially enhancing the outflow of VFAs from the rumen and thereby limiting their accumulation [55].

In addition, some studies have suggested that diets containing higher proportions of concentrates promote a feeding pattern characterized by a greater number of small meals, which may represent a behavioral adaptation to mitigate the risk of ruminal acidosis [76]. Consistent with this hypothesis, ewes in both experimental groups consumed their daily feed in multiple small meals, with few large meals observed. Such a feeding pattern likely prevents the rapid accumulation of VFAs within the rumen, thereby contributing to the maintenance of stable ruminal pH and systemic acid-base balance.

4.3. Milk Yield and Composition, Changes in Body Weight and Feed Efficiency

Assaf is classified as a high-yielding dairy sheep breed, as ewes typically produce between 300 and 450 L of milk per lactation, with a minimum lactation length of 170 days [77,78], corresponding to average daily milk yields of approximately 1.9 to 2.7 L/day. Milk production and composition values in the present study were within the range previously reported for Assaf ewes [3,77,79]. Throughout the experimental period, milk yield remained relatively stable in ewes fed the pelleted total mixed ration (PTMR), whereas a decline was observed in those fed the conventional total mixed ration (CTMR). Specifically, the slopes of the regression of milk yield over time were –13.5 ± 1.88 g/day and +3.7 ± 1.20 g/day for the CTMR and PTMR groups, respectively. Consequently, from the second week of the experimental period onward, daily milk production was significantly higher in the PTMR group.

The reduction in milk yield observed in ewes fed the CTMR diet is consistent with their lower feed intake and greater body weight loss. Milk yield can be affected when energy intake is below requirements and body reserves mobilization cannot fully compensate for the negative energy balance [80], so that milk production can be compromised. The magnitude of milk yield loss depends on the stage of lactation and the severity and duration of the negative energy balance [81]. However, the mammary gland has biological priority over maternal tissues so that the synthesis of milk component is tightly regulated and buffered against short-term nutrient shortages, thus ensuring stable milk composition even when the lactating female is in negative energy balance [81,82]. While ewes receiving the CTMR diet exhibited a greater BW loss (approximately 100 g/day) compared to those on the PTMR diet, the magnitude of this loss remained relatively minor. Consequently, although both experimental groups experienced a negative energy balance, the deficit was mild and most likely insufficient to impair the mammary synthesis of milk constituents. Consistent with this observation, no significant differences in milk composition were detected between the two dietary treatments.

The absence of differences in milk composition despite evidence of a less favorable energy balance in CTMR-fed ewes may be explained by the relatively modest magnitude of the energy deficit, corresponding to an average weight loss of approximately 100 g/day. In cases of substantial fat mobilization, blood concentrations of non-esterified fatty acids and ketone bodies, such as acetone and β-hydroxybutyrate, typically increase. Under such conditions, ketone body concentrations in milk also rise, supporting their use as biomarkers of hyperketonemia [83]. In the present study, however, no differences were observed between treatments in milk acetone or β-hydroxybutyrate concentrations.

Previous studies have reported that the use of pelleted diets may decrease the digestibility of neutral detergent fiber and alter ruminal fermentation patterns, potentially reducing milk fat content [28,84]. Conversely, a negative energy balance is typically associated with an increase in milk fat concentration [80]. Therefore, the absence of differences in milk fat content between treatments suggests that ruminal fermentation patterns were largely comparable between the CTMR and PTMR diets. This finding aligns with results from previous studies in dairy cows, which have not reported adverse effects of pelleted diets on milk composition [12,13]. To our knowledge, no studies directly comparing pelleted and non-pelleted total mixed rations in lactating ewes have been reported. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that ewes appear less susceptible than cows to diet-induced milk fat depression when dietary fermentability is increased or feed particle size is reduced [85].

Diet pelleting did not significantly affect feed efficiency, as no differences between CTRM and PTRM were observed in residual feed intake or in feed conversion ratio. However, the greater body weight loss observed in CTMR-fed ewes likely compensated for their lower apparent efficiency. Based on AFRC [42] estimations, milk production attributable to mobilized body reserves averaged 485 ± 0.3 g/day in the CTMR group and 70 ± 0.4 g/day in the PTMR group. After accounting for this contribution, feed efficiency in CTMR-fed ewes was approximately 29% lower than in the PTMR group. An inverse relationship (R2 = 0.84; Figure 4) was observed between milk yield and feed conversion ratio after correction for body weight loss. Therefore, this apparent effect should be interpreted as a mathematical artifact rather than as evidence of differences in digestive or metabolic efficiency between diets.

5. Conclusions

The use of pelleted total mixed rations in high-yielding dairy ewes improves feed intake, milk yield, and overall energy balance without causing adverse effects on milk composition or animal health in the short term. Feed efficiency is also enhanced, primarily because of the increased dry matter intake associated with the pelleted diet. Further research is warranted to assess the long-term implications of feeding pelleted total mixed rations and to elucidate the physiological and behavioral mechanisms, as well as the potential modulating factors involved in the regulation of feed intake and eating behavior in dairy ewes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A., S.L. and F.J.G.; methodology, F.J.G.; formal analysis, S.L., A.D.R. and F.J.G.; investigation, S.A., S.L., A.D.R., A.M., L.M., R.B. and F.J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L. and F.J.G.; writing—review and editing, S.A., S.L., A.D.R., A.M., L.M., R.B. and F.J.G.; supervision, F.J.G.; project administration, S.A.; funding acquisition, S.A. and F.J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (PID2021-126489OB-I00, MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, “FEDER, Una manera de hacer Europa”).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Instituto de Ganadería de Montaña (CSIC, Spain) (protocol number 100102/2021-6).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be addressed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The collaboration of the Animal Selection and Reproduction Center (CENSYRA, Junta de Castilla y León, Spain) in the analysis of milk samples is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TMR | Total Mixed Ration |

| CTMR | Control (unpelleted) Total Mixed Ration |

| PTMR | Pelleted Total Mixed Ration |

| DM | Dry matter |

| DMI | Dry matter intake |

| BW | Body weight |

| FCR | Feed conversion ratio |

| MY | Milk yield |

| SED | Standard error of the difference |

| VFA | Volatile fatty acids |

References

- Papanikolopoulou, V.; Vouraki, S.; Priskas, S.; Theodoridis, A.; Dimitriou, S.; Arsenos, G. Economic Performance of Dairy Sheep Farms in Less-Favoured Areas of Greece: A Comparative Analysis Based on Flock Size and Farming System. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timpanaro, G.; Foti, V.T. The Sustainability of Small-scale Sheep and Goat Farming in a Semi-arid Mediterranean Environment. J. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 2024, 3, e12111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milán, M.J.; Caja, G.; González-González, R.; Fernández-Pérez, A.M.; Such, X. Structure and Performance of Awassi and Assaf Dairy Sheep Farms in Northwestern Spain. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Cushon, E.K.; DeVries, T.J. Feed Sorting in Dairy Cattle: Causes, Consequences, and Management. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 4172–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, J.H.; dos Santos, J.F.; Almeida, R. Accuracy and Physical Characteristics of Total Mixed Rations and Feeding Sorting Behavior in Dairy Herds of Castro, Paraná. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2021, 50, 620200174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schingoethe, D.J. A 100-Year Review: Total Mixed Ration Feeding of Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 10143–10150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthel, R.; Dohme-Meier, F.; Keil, N. Dairy Sheep and Goats Sort for Particle Size and Protein in Mixed Rations. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2024, 271, 106144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schingoethe, D.J.; Stegeman, G.A.; Treacher, R.J. Response of Lactating Dairy Cows to a Cellulase and Xylanase Enzyme Mixture Applied to Forages at the Time of Feeding. J. Dairy Sci. 1999, 82, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neave, H.W.; Weary, D.M.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G. Review: Individual Variability in Feeding Behaviour of Domesticated Ruminants. Animal 2018, 12, s419–s430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, A.A.; Iommelli, P.; Morello, A.R.; Britti, D.; Pelle, N.; Poerio, G.; Morittu, V.M. Particle Size Distribution and Feed Sorting of Hay-Based and Silage-Based Total Mixed Ration of Calabrian Dairy Herds. Dairy 2024, 5, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthel, R.; Simmler, M.; Dohme-Meier, F.; Keil, N. Dairy Sheep and Goats Prefer the Single Components over the Mixed Ration. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 1017669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, P.A.; Davis, R.E. Effect of Feeding Pelleted Complete Rations to Lactating Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1961, 44, 1465–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, G.C.; Thurmon, H.S.; Olson, H.H.; Reed, A. Complete Feed Rations for Lactating Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1966, 49, 1058–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; Serra, A.; Pulina, G.; Cannas, A.; Brandano, P. L’Utilizzazione di un Alimento Unico Pellettato (Unipellet) nell’Alimentazione dell Pecore da Latte. I. Influenza della Grassatura e del Livello Proteico sulla Produzione Quanti-Qualitativa di Latte in Pecore di Raza Sarda. Zootec. Nutr. Anim. 1991, 17, 2–34. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, A.; Calamari, L.; Cappa, V.; Cannas, A.; Rossi, G. Trial on Use of a Complete Pelleted Feed (Unipellet) in Lactating Ewes: Metabolic Profile Results. Ann. Fac. Agric. Univ. Sassari (I) 1992, 34, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Murdock, F.R.; Hodgson, A.S. Cubed Complete Rations for Lactating Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1977, 60, 1921–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dell, G.D.; King, W.A.; Cook, W.C. Effect of Grinding, Pelleting, and Frequency of Feeding of Forage on Fat Percentage of Milk and Milk Production of Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1968, 51, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo Trabi, E.; Seddik, H.; Xie, F.; Lin, L.; Mao, S. Comparison of the Rumen Bacterial Community, Rumen Fermentation and Growth Performance of Fattening Lambs Fed Low-Grain, Pelleted or Non-Pelleted High Grain Total Mixed Ration. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2019, 253, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, C.; Giráldez, F.J.; Prieto, N.; Benavides, J.; Wattegedera, S.; Morán, L.; Andrés, S.; Bodas, R. Total Mixed Ration Pellets for Light Fattening Lambs: Effects on Animal Health. Animal 2015, 9, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.I.; Rashid, M.A.; Yousaf, M.S.; Naveed, S.; Javed, K.; Rehman, H. Effect of Physical Form and Level of Wheat Straw Inclusion on Growth Performance and Blood Metabolites of Fattening Goat. Animals 2020, 10, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Li, F.; Ma, Z.; Li, F.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; et al. Effects of Dietary Forage Neutral Detergent Fiber and Rumen Degradable Starch Ratios on Chewing Activity, Ruminal Fermentation, Ruminal Microbes and Nutrient Digestibility of Hu Sheep Fed a Pelleted Total Mixed Ration. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, M.A.; Rashid, M.A.; Yousaf, M.S.; Naveed, S.; Shahid, M.Q.; Rehman, H.U. Effect of Straw Particle Size in High Grain Complete Pelleted Diet on Growth Performance, Rumen pH, Feeding Behavior, Nutrient Digestibility, Blood and Carcass Indices of Fattening Male Goats. Small Rumin. Res. 2023, 219, 106907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, N.; Ungerfeld, E.; Guo, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, M.; Ma, Z. Effects of Supplementing a Yeast Culture in a Pelleted Total Mixed Ration on Fiber Degradation, Fermentation Parameters, and the Bacterial Community in the Rumen of Sheep. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2023, 296, 115565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronning, M. Effect of Varying Alfalfa Hay-Concentrate Ratios in a Pelleted Ration for Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1960, 14, 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, T.; Christensen, D.A.; Manns, J.G. Performance of Lactating Dairy Cows Fed Complete Pelleted Diets Based on Wheat Straw, Barley and Wheat. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 1974, 54, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retnani, Y.; Risyahadi, S.; Qomariyah, N.; Barkah, N.; Taryati, T.; Jayanegara, A. Comparison between Pelleted and Unpelleted Feed Forms on the Performance and Digestion of Small Ruminants: A Meta-Analysis. J. Anim. Feed. Sci. 2022, 31, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankins, D.L.; Pugh, D.G. Feeding and Nutrition. In Sheep and Goat Medicine, 2nd ed.; Pugh, D.G., Baird, A.N., Eds.; W.B. Saunders: Saint Louis, MO, USA, 2012; pp. 18–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Zhao, C.; Feng, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Luo, D.; Cheng, L.; Liu, D.; Fang, Y. Effects of Feeding Ground versus Pelleted Total Mixed Ration on Digestion, Rumen Function and Milk Production Performance of Dairy Cows. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2020, 73, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, M.M.; Al-Marashdeh, O.; Gan, L.P.; Zhang, C.Y.; Zhang, G.G. Performance, Rumen Fermentation, and Gastrointestinal Microflora of Lambs Fed Pelleted or Unpelleted Total Mixed Ration. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2019, 253, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Sun, X.; Huo, Q.; Zhang, G.; Wu, T.; You, P.; He, Y.; Tian, W.; Li, R.; Li, C.; et al. Pelleting of a Total Mixed Ration Affects Growth Performance of Fattening Lambs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 629016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lárusson, T.; Sveinbjörnsson, J. The Effects of Pelleting Hay upon Feed Intake, Digestibility, Growth Rate and Energy Retention of Lambs. Icel. Agric. Sci. 2023, 36, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, E.; Brambilla, M.; Cutini, M.; Giovinazzo, S.; Lazzari, A.; Calcante, A.; Tangorra, F.M.; Rossi, P.; Motta, A.; Bisaglia, C.; et al. Increased Cattle Feeding Precision from Automatic Feeding Systems: Considerations on Technology Spread and Farm Level Perceived Advantages in Italy. Animals 2023, 13, 3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M. Labour and Skills Shortages in the Agro-Food Sector; OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers No. 189; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASDA. A Report: Committee on Classification of Particle Size in Feedstuffs. J. Dairy Sci. 1970, 53, 689–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldo, R.; Smith, L.W.; Cox, E.L.; Weinland, B.T.; Lucas, H.L., Jr. Logarithmic Normal Distribution for Description of Sieved Forage Materials. J. Dairy Sci. 1971, 54, 1465–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6496:1999; Animal Feeding Stuffs Determination of Moisture and Other Volatile Matter Content. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999.

- ISO 5984:2022; Animal Feeding Stuffs—Determination of Crude Ash. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- ISO 5983-2:2009; Animal Feeding Stuffs Determination of Nitrogen Content and Calculation of Crude Protein Content—Part 2: Block Digestion and Steam Distillation Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for Dietary Fiber, Neutral Detergent Fiber, and Nonstarch Polysaccharides in Relation to Animal Nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOCS. Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemistry Society, 5th ed.; Firestone, D., Ed.; AOCS: Champaign, IL, USA, 1998; ISBN 0935315977. [Google Scholar]

- Bocquier, F.; Barillet, F.; Guillouet, P.; Jacquin, M. Prévision de l’énergie Du Lait de Brebis à Partir de Différents Résultats d’analyses: Proposition de Lait Standard Pour Les Brebis Laitières. Ann. Zootech. 1993, 42, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AFRC. Energy and Protein Requirements of Ruminants; An Advisory Manual Prepared by the AFRC Technical Committee on Nutrient Responses; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1993; ISBN 9780851988511. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, N.; Bodas, R.; López-Campos, Ó.; Andrés, S.; López, S.; Giráldez, F.J. Effect of Sunflower Oil Supplementation and Milking Frequency Reduction on Sheep Milk Production and Composition. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, A.; Giráldez, F.J.; Mateos, I.; Saro, C.; Mateo, J.; Andrés, S.; Caro, I.; Ranilla, M.J. Feeding Broccoli and Cauliflower to Dairy Sheep: Influence on Feed Intake, Metabolic Health Status and Milk Production and Composition. Animal 2025, 19, 101530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vega, A.; Gasa, J.; Guada, J.A.; Castrillo, C. Frequency of Feeding and Form of Lucerne Hay as Factors Affecting Voluntary Intake, Digestibility, Feeding Behaviour, and Marker Kinetics in Ewes. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2000, 51, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, S.; Kellaway, R.; Black, J. Effect of Forage Particle Length on Rumen Digesta Load, Packing Density and Voluntary Feed Intake by Sheep. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1992, 43, 1321–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, M.; Adebayo, R.A.; Nsahlai, I.V. Effects of Diet and Roughage Quality, and Period of the Day on Diurnal Feeding Behaviour Patterns of Sheep and Goats under Subtropical Conditions. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 32, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mialon, M.M.; Martin, C.; Garcia, F.; Menassol, J.B.; Dubroeucq, H.; Veissier, I.; Micol, D. Effects of the Forage-to-Concentrate Ratio of the Diet on Feeding Behaviour in Young Blond d’Aquitaine Bulls. Animal 2008, 2, 1682–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giger-Reverdin, S.; Rigalma, K.; Desnoyers, M.; Sauvant, D.; Duvaux-Ponter, C. Effect of Concentrate Level on Feeding Behavior and Rumen and Blood Parameters in Dairy Goats: Relationships between Behavioral and Physiological Parameters and Effect of between-Animal Variability. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 4367–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vega, A.; Gasa, J.; Castrillo, C.; Guada, J.A. Presentation (Chopped versus Ground and Pelleted) of a Low-Quality Alfalfa Hay in Sheep: Effects on Intake, Feeding Behaviour, Rumen Fill and Digestion, and Passage. Animals 2025, 15, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulina, G.; Cannas, A.; Rassu, S.P.G.; Rossi, G.; Brandano, P.; Serra, A. The Effect of the Utilization of a High Fibre Pelleted Feed on Milk Yield and Composition in Dairy Sheep. Ann. Fac. Agric. Univ. Sassari 1993, 35, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, J.F.D.; Reid, G.W. The Effects of Pelleting Various Diets on Intake and Digestibility in Sheep and Cattle. Anim. Prod. 1973, 16, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimizadeh, E.; Chaji, M.; Mohammadabadi, T. Effects of Physical Form of Diet on Nutrient Digestibility, Rumen Fermentation, Rumination, Growth Performance and Protozoa Population of Finishing Lambs. Anim. Nutr. 2017, 3, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermudez, F.F.; Forbes, J.M.; Jones, R. Feed Intakes and Meal Patterns of Sheep during Pregnancy and Lactation, and after Weaning. Appetite 1989, 13, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin, K.A. Invited Review: Current Perspectives on Eating and Rumination Activity in Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4762–4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquel-Kergoat, S.; Azais-Braesco, V.; Burton-Freeman, B.; Hetherington, M.M. Effects of Chewing on Appetite, Food Intake and Gut Hormones: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 151, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.S. Effects of Diet on Short-Term Regulation of Feed Intake by Lactating Dairy Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2000, 83, 1598–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faverdin, P. The Effect of Nutrients on Feed Intake in Ruminants. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1999, 58, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, M.S. Drives and Limits to Feed Intake in Ruminants. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2014, 54, 1513–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albornoz, R.I.; Kennedy, K.M.; Bradford, B.J. Symposium Review: Fueling Appetite: Nutrient Metabolism and the Control of Feed Intake. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 2161–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, M.; Ying, Y.; Bartell, P.A.; Harvatine, K.J. The Effects of Feeding Time on Milk Production, Total-Tract Digestibility, and Daily Rhythms of Feeding Behavior and Plasma Metabolites and Hormones in Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 7764–7776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, T.A.; Dilaga, W.S.; Purnomoadi, A. Eating Behaviour of Sheep Fed at Day and/or Night Period. J. Indones. Trop. Anim. Agric. 2015, 40, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salfer, I.J.; Harvatine, K.J. Night-Restricted Feeding of Dairy Cows Modifies Daily Rhythms of Feed Intake, Milk Synthesis and Plasma Metabolites Compared with Day-Restricted Feeding. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 123, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvatine, K.J. Importance of Circadian Rhythms in Dairy Nutrition. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2023, 63, 1827–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin, K.; Penner, G. New Developments in Understanding Ruminal Acidosis in Dairy Cows. In Proceedings of the Tri-State Dairy Nutrition Conference, Fort Wayne, IN, USA, 21–22 April 2009; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- González, L.A.; Manteca, X.; Calsamiglia, S.; Schwartzkopf-Genswein, K.S.; Ferret, A. Ruminal Acidosis in Feedlot Cattle: Interplay between Feed Ingredients, Rumen Function and Feeding Behavior (A Review). Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2012, 172, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.R.; Allen, O.B.; Grovum, W.L. The Effect of Feeding Frequency and Meal Size on Amounts of Total and Parotid Saliva Secreted by Sheep. Br. J. Nutr. 1990, 63, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrillo, C.; Mota, M.; Van Laar, H.; Martín-Tereso, J.; Gimeno, A.; Fondevila, M.; Guada, J.A. Effect of Compound Feed Pelleting and Die Diameter on Rumen Fermentation in Beef Cattle Fed High Concentrate Diets. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2013, 180, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nardi, R.; Marchesini, G.; Gianesella, M.; Ricci, R.; Montemurro, F.; Contiero, B.; Andrighetto, I.; Segato, S. Blood Parameters Modification at Different Ruminal Acidosis Conditions. Agric. Conspec. Sci. 2013, 78, 259–262. [Google Scholar]

- Gianesella, M.; Morgante, M.; Cannizzo, C.; Stefani, A.; Dalvit, P.; Messina, V.; Giudice, E. Subacute Ruminal Acidosis and Evaluation of Blood Gas Analysis in Dairy Cow. Vet. Med. Int. 2010, 2010, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humer, E.; Aschenbach, J.R.; Neubauer, V.; Kröger, I.; Khiaosa-ard, R.; Baumgartner, W.; Zebeli, Q. Signals for Identifying Cows at Risk of Subacute Ruminal Acidosis in Dairy Veterinary Practice. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 102, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voulgarakis, N.; Gougoulis, D.A.; Psalla, D.; Papakonstantinou, G.I.; Katsoulis, K.; Angelidou-Tsifida, M.; Athanasiou, L.V.; Papatsiros, V.G.; Christodoulopoulos, G. Subacute Rumen Acidosis in Greek Dairy Sheep: Prevalence, Impact and Colorimetry Management. Animals 2024, 14, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villot, C.; Meunier, B.; Bodin, J.; Martin, C.; Silberberg, M. Relative Reticulo-Rumen pH Indicators for Subacute Ruminal Acidosis Detection in Dairy Cows. Animal 2018, 12, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golder, H.M.; Lean, I.J. Invited Review: Ruminal Acidosis and its Definition—A Critical Review. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 10066–10098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, L.A.; Ferret, A.; Manteca, X.; Calsamiglia, S. Increasing Sodium Bicarbonate Level in High-Concentrate Diets for Heifers. I. Effects on Intake, Water Consumption and Ruminal Fermentation. Animal 2008, 2, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abijaoudé, J.A.; Morand-Fehr, P.; Tessier, J.; Schmidely, P.; Sauvant, D. Diet Effect on the Daily Feeding Behaviour, Frequency and Characteristics of Meals in Dairy Goats. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2000, 64, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollott, G.E.; Gootwine, E. Reproductive Performance and Milk Production of Assaf Sheep in an Intensive Management System. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 3690–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milán, M.J.; Frendi, F.; González-González, R.; Caja, G. Cost Structure and Profitability of Assaf Dairy Sheep Farms in Spain. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 5239–5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, E.; Giráldez, F.J.; Bodas, R.; Andrés, S.; Prieto, N. Effect of Reduction of Milking Frequency and Supplementation of Vitamin E and Selenium above Requirements on Milk Yield and Composition in Assaf Ewes. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 3527–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herve, L.; Quesnel, H.; Veron, M.; Portanguen, J.; Gross, J.J.; Bruckmaier, R.M.; Boutinaud, M. Milk Yield Loss in Response to Feed Restriction is Associated with Mammary Epithelial Cell Exfoliation in Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 2670–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leduc, A.; Souchet, S.; Gelé, M.; Le Provost, F.; Boutinaud, M. Effect of Feed Restriction on Dairy Cow Milk Production: A Review. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99, skab130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, D.E. Regulation of Nutrient Partitioning during Lactation: Homeostasis and Homeorhesis Revisited. In Ruminant Physiology: Digestion, Metabolism, Growth and Reproduction; Cronjé, P.B., Ed.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2000; pp. 311–328. [Google Scholar]

- Benedet, A.; Manuelian, C.L.; Zidi, A.; Penasa, M.; De Marchi, M. Invited Review: β-Hydroxybutyrate Concentration in Blood and Milk and Its Associations with Cow Performance. Animal 2019, 13, 1676–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bath, D.L. Reducing Fat in Milk and Dairy Products by Feeding. J. Dairy Sci. 1982, 65, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewanckele, L.; Toral, P.G.; Vlaeminck, B.; Fievez, V. Invited Review: Role of Rumen Biohydrogenation Intermediates and Rumen Microbes in Diet-Induced Milk Fat Depression: An Update. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 7655–7681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.