Abstract

The western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte) remains one of the most damaging pests of maize across Europe, including Romania. Reliable integrated pest management relies on monitoring systems capable of capturing adult flight activity under field conditions. This study presents a comparative field evaluation of three monitoring approaches: Virgiwit yellow sticky panels (YSP), pheromone-based CSALOMON® KLP+ traps, and the automated iScout® digital monitoring system. Monitoring was conducted at weekly intervals over an eight-week period (20 July–15 September 2025) in four maize fields in western Romania. Capture data were analyzed descriptively to assess relative trap performance and to explore associations with selected meteorological variables. KLP+ traps consistently recorded the highest numbers of adults, while YSP traps reproduced the main seasonal flight patterns. The iScout® system captured fewer individuals but provided continuous temporal information on adult activity. Correlation analyses indicated generally weak and inconsistent relationships between trap captures and short-term weather variables, reflecting the limitations imposed by weekly manual sampling and site-specific variability. Overall, the results highlight the complementary strengths and limitations of manual and automated monitoring tools and support their exploratory use for characterizing seasonal flight activity and temporal population patterns of Diabrotica virgifera virgifera under field conditions. Further multi-year and device-specific validation is required before automated systems can be fully integrated into operational pest management frameworks.

1. Introduction

The western corn rootworm (WCR; Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) is one of the most destructive and invasive pests of maize (Zea mays L.) worldwide, causing substantial yield losses and threatening crop sustainability across Europe [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. The pest was first detected in Europe in the early 1990s and has since spread throughout Central and Eastern regions, including Romania [4,5,6,7,8].

Effective integrated pest management (IPM) strategies rely on accurate and timely monitoring of adult populations to guide control decisions and assess infestation risk [9,10,11,12]. Over time, various trap types have been used for detecting and monitoring pest insects, including Diabrotica virgifera virgifera, most of them presenting several limitations [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Conventional traps typically require weekly field inspection and manual counting of captured insects, which is time-consuming and labor-intensive, particularly in large-scale maize fields. In addition, manually collected data are often delayed in time, reducing their usefulness for rapid management decisions [4,10,13].

Among available trapping systems, yellow sticky panels remain simple visual tools for estimating population trends, while pheromone-baited CSALOMON® KLP “hat” traps have long been used for monitoring based on the synthetic sex pheromone [19,20,21].

To improve capture efficiency and attract both sexes, floral-based attractants containing plant-derived volatiles have been combined with pheromone lures in WCR traps [22,23,24]. This dual-lure approach enhances trap responsiveness under variable field conditions and provides a more complete picture of adult population dynamics [25,26,27].

Recent technological advances have focused on overcoming these challenges through the development of automated or digital traps capable of detecting and enumerating target species in real time. Accurate forecasting of pest infestation dynamics requires real-time monitoring systems that facilitate the precise timing and localization of control interventions [14,15,16,17,18].

More recently, automated monitoring platforms such as the ZooLog KLP opto-electronic probe [28], iScout® automated trap (Pessl Instruments GmbH, Weiz, Austria) (https://metos.global/en/iscout/; accessed on 5 July 2025), and the Trap view VERTICAL SC trap equipped with temperature–humidity (T-Rh) sensors [28,29,30,31,32,33] have enabled remote image transmission, cloud-based insect recognition, and real-time data sharing.

In addition, climate-based risk modelling has shown that temperature increases could expand the potential distribution range of D. virgifera virgifera across Europe, including Romania [15,16,34,35]. These projections emphasize the importance of developing reliable, automated monitoring systems capable of detecting population shifts and flight patterns under local agroclimatic conditions [36,37,38]. However, few studies have assessed how different trap types, traditional and automated, with combined pheromone and floral attractants, perform simultaneously within the same maize fields, particularly under Romanian environmental and management contexts, where pest pressure and phenology may differ from those observed in Central Europe [2,6,12,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49].

A clear understanding and evaluation of how different trap types and attractant combinations represent pest activity are key to advancing decision-support tools and integrating automated monitoring into regional IPM frameworks [50,51,52,53,54].

Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate and compare the performance of three monitoring trap types, yellow sticky panels, CSALOMON® KLP pheromone + floral traps, and iScout® automated digital traps, for detecting adult flight activity of D. virgifera virgifera in maize fields of Bihor County, Romania. The research aimed to describe the temporal dynamics of adult flight, determine trap sensitivity and capture efficiency, assess relationships between weekly captures and key meteorological variables, and identify the most suitable trap type for early detection and routine field monitoring within Romanian IPM programs. The iScout® automated monitoring system was not originally developed specifically for Diabrotica virgifera virgifera, but represents an imaging-based platform adapted from broader pest monitoring applications. Its performance in WCR monitoring therefore requires careful evaluation and calibration before operational deployment.

To achieve these objectives, field experiments were established in four maize-growing sites located in Bihor County, northwestern Romania. Monitoring traps representing different detection principles (visual, pheromone-based, and automated) were deployed under comparable field conditions throughout the 2025 growing season. Data collection focused on weekly adult captures, allowing the comparison of trap efficiency and flight dynamics across devices and locations. Details of the experimental design, trap characteristics, and analytical approach are provided in the Materials and Methods section.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites and Field Characteristics

The study was conducted in four maize fields located in Bihor County, northwestern Romania: Livada de Bihor (P1), Salonta (P2), Tulca (P3), and Rohani (P4) (Table 1). Plot P2 was managed under an organic farming system, whereas P1, P3 and P4 followed conventional agronomic practices. The FAO values reported in Table 1 refer to the maturity groups of the maize hybrids cultivated in each plot. Specifically, FAO 350 and FAO 410 indicate medium-early to medium maturity classes, which are commonly grown under the agroecological conditions of western Romania. The monitored fields differed in their management histories. Conventional plots were managed using standard regional practices, including mineral fertilization and chemical weed control, whereas the organic plot relied on mechanical weed control and organic fertilization practices. Detailed quantitative records of input rates were not available for all sites, and these management differences may have contributed to observed variability in adult captures. All sites were located within the lowland maize-production zone, characterized by warm continental summers and moderate rainfall. Elevation across fields ranged between 85–108 m a.s.l.

Table 1.

Description of experimental sites.

Each field consisted of a uniformly planted maize crop (Zea mays L.) cultivated according to standard local practices, with sowing conducted between mid-April and early May. No insecticides targeting Diabrotica virgifera virgifera were applied in any of the experimental fields during the study period.

2.2. Monitoring Period and Trap Deployment

Monitoring was conducted for eight consecutive weeks, from 20 July to 15 September 2025, covering the main adult flight period of D. v. virgifera in the region. Three types of traps were used (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview and detailed views of the three monitoring systems used for tracking Diabrotica virgifera virgifera adults in maize fields. (a) Yellow Sticky Panel (YSP) trap installed at tasseling stage; (b) Detail of YSP adhesive surface showing captured adults; (c) CSALOMON® KLP+ pheromone–floral trap placed at mid-canopy level; (d) Detail of KLP+ inner capture container with accumulated beetles; (e) iScout® automated remote-sensing trap with solar-powered unit; (f) Interior view of the iScout® trap showing the adhesive panel and pheromone dispenser.

The three monitoring systems differed in both trap design and attractant composition. Yellow sticky panels (with pheromone Virgiwit®) (https://www.witasek.com/) were equipped with plant-volatile-based lures designed to enhance visual attraction. CSALOMON® KLP+ traps (Plant Protection Institute, Centre for Agricultural Research, Budapest, Hungary) were baited with a combination of a synthetic sex pheromone and a floral attractant, enabling attraction of both male and female adults. The iScout® automated system used pheromone-baited adhesive panels coupled with image-based detection. Differences in lure composition among trap types are therefore expected to influence capture rates and should be considered when interpreting quantitative differences among monitoring systems. KLP+ traps were used as the reference method due to their established sensitivity and widespread use in WCR population assessment.

All traps were installed at a height of 170–180 cm, following the manufacturers’ technical guidelines and corresponding to the upper maize canopy, where adult activity is typically highest, and positioned within the central area of each field to minimize border effects. The minimum distance between any two traps within a plot was 50 m to avoid interference among attractants.

In each monitoring plot, one trap of each manual type (KLP+ and YSP) was deployed, resulting in one replicate per trap type per site. Due to logistical and equipment availability constraints, the automated iScout® system was installed only in two plots (P1 and P2), with one unit per plot. As a result, the experimental design was observational and descriptive, focusing on side-by-side field performance rather than replicated inferential testing.

2.3. Trap Servicing and Data Collection

Manual traps (KLP+ and YSP) were inspected at weekly intervals, and captured beetles were counted on site. Adhesive surfaces and lures were replaced whenever saturation or degradation occurred, following manufacturer recommendations.

iScout® traps acquired digital images at 12–24 h intervals and transmitted them through GSM/GPRS to the associated cloud platform. In cases of unstable signal reception, images were stored locally and retrieved during the next successful transmission. All images generated by the iScout® automated trap were subjected to manual validation prior to data analysis. Image validation was performed by trained personnel with experience in the identification of Diabrotica virgifera virgifera. A detection was considered correct when adult beetles could be clearly recognized based on external morphological features, including body shape, coloration, and size. Images with low resolution, overlapping insects, or uncertain taxonomic identification were excluded from further analysis. No formal interrater reliability analysis or quantitative accuracy metrics (e.g., precision or recall) were applied. Therefore, image validation should be regarded as a qualitative confirmation of species presence rather than a full evaluation of automated detection performance.

Daily weather data (mean air temperature, precipitation, and relative humidity) were obtained from the nearest Romanian national weather stations (5–12 km from the plots) (Table 2), maintained by the National Meteorological Administration. These data were synchronized with trapping dates for statistical analysis.

Table 2.

Site and the straight-line distance between each site and its assigned station.

Within each plot, different trap types were installed at standardized distances to ensure exposure to the same local beetle population while minimizing interference.

2.4. Data Preprocessing

Daily trap captures and meteorological observations were checked for completeness and converted to numeric formats. Because manual trap inspections (YSP and KLP+) were conducted at weekly intervals, the recorded capture values represent cumulative adult activity over several days rather than discrete daily counts. To ensure temporal consistency between response variables and meteorological data, weather variables (air temperature, precipitation, and relative humidity) were aggregated to weekly values corresponding to each trap inspection. Weekly mean values were used for temperature and relative humidity, while weekly cumulative precipitation was calculated. Correlation analyses therefore reflect associations between weekly trap captures and weekly meteorological conditions and should be interpreted as exploratory.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Trap capture data were summarized using descriptive statistics and visualized through boxplots and scatter plots to explore temporal and spatial patterns in adult activity. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to describe associations between weekly trap captures and weekly aggregated meteorological variables (mean air temperature, cumulative precipitation, and mean relative humidity). Given the limited number of monitoring plots, the unbalanced deployment of automated traps, and the weekly integration of manual trap data, all statistical analyses were considered exploratory and descriptive. No causal inference was attempted. More advanced modelling approaches (e.g., generalized linear mixed models accounting for count distributions, site effects, and temporal autocorrelation) were considered beyond the scope of the present dataset and are proposed for future studies with larger and more balanced experimental designs.

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.1).

3. Results

3.1. Adult Capture Dynamics Across Monitoring Sites and Trap Types

Weekly aggregation of trap captures revealed marked quantitative differences among sites and trap types. Overall, KLP+ traps consistently recorded the highest weekly totals, followed by YSP traps, while the iScout® system produced the lowest values in plots where it was deployed.

Across plots, mean weekly captures ranged from 44.0 to 830.0 adults for YSP, from 99.6 to 3489.3 adults for KLP+, and from 19.0 to 22.1 adults for the iScout® system (Table S1). Maximum weekly captures showed large spatial contrasts: YSP ranged from 133 adults (P4) to 11,315 adults (P3), whereas KLP+ ranged from 286 adults (P4) to 19,857 adults (P3). Median weekly captures were consistently lower than mean values for all trap types, reflecting the asymmetrical distribution of activity peaks across the flight period.

Plots P3 and P1 showed the highest variability, with interquartile ranges (IQR) of 1373.0 and 83.5 adults for YSP, and 425.4 and 285.8 adults for KLP+, respectively. In contrast, P4 showed the narrowest distributions for both YSP (IQR = 79.3 adults) and KLP+ (IQR = 100.5 adults). The iScout® system, deployed only in P1 and P2, showed relatively low weekly medians (14.5 and 5.0 adults) and narrow dispersion.

These descriptive values provide a numerical overview of adult capture intensity and variability across monitoring sites and serve as the basis for the comparative statistical analysis presented below. Because weekly capture data showed strong skewness and the presence of extreme values, variability was summarized using medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) rather than means and standard deviations. Detailed descriptive statistics for each plot and trap type are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

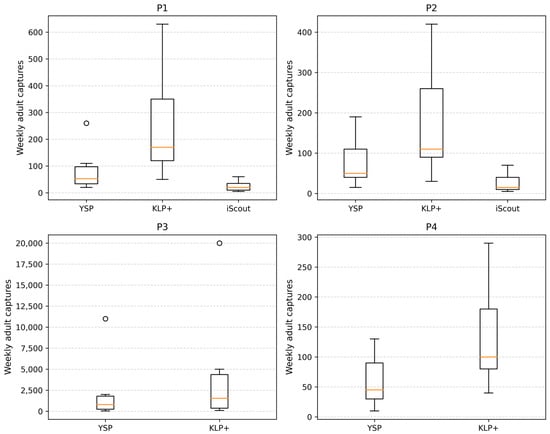

3.1.1. Capture Levels at the Monitoring Sites

Weekly boxplots for each monitoring plot (Figure 2) illustrate the distribution of weekly capture values for each trap type present in the corresponding location. In P1, KLP+ traps exhibited the highest weekly median (125.5 adults) and the widest dispersion (IQR = 285.8 adults), while YSP and iScout® traps showed substantially lower medians (15.0 and 14.5 adults, respectively). Maximum weekly captures ranged from 63 adults in iScout® to 632 adults in KLP+.

Figure 2.

Weekly captures of Diabrotica virgifera virgifera adults recorded in four maize plots (P1–P4) using different monitoring methods. Boxplots show the weekly distribution of adult captures for each trap type present at each site (YSP, KLP+, and iScout® in P1 and P2; YSP and KLP+ in P3 and P4). Boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR), the horizontal line inside each box indicates the median, and whiskers extend to 1.5 × IQR. Individual points represent outliers. Differences in median values and dispersion reflect spatial variation in adult population levels and trap-specific capture performance among monitoring plots.

In P2, KLP+ again showed the largest weekly maxima (426 adults) and median (69.0 adults), followed by YSP (median = 12.0 adults) and iScout® (median = 5.0 adults). Weekly IQR values reflected this hierarchy (188.8 adults in KLP+, 64.0 adults in YSP, and 25.5 adults in iScout®).

Plot P3 showed the most pronounced activity peaks of the entire monitoring network. Here, YSP traps reached a weekly maximum of 11,315 adults, while KLP+ recorded the highest peak observed across all plots (19,857 adults). Despite these extreme values, median weekly captures remained moderate (135.0 adults for YSP and 260.0 adults for KLP+), reflecting an uneven distribution of high-activity weeks.

In P4, weekly captures were lower and more homogeneous, with medians of 30.0 adults for YSP and 80.5 adults for KLP+. Maximum weekly captures in this plot (133 adults for YSP and 286 adults for KLP+) were substantially lower compared with P3 or P1.

Overall, the boxplots emphasize both the spatial variability of adult population levels and the consistent ranking of trap performance observed across the monitoring sites.

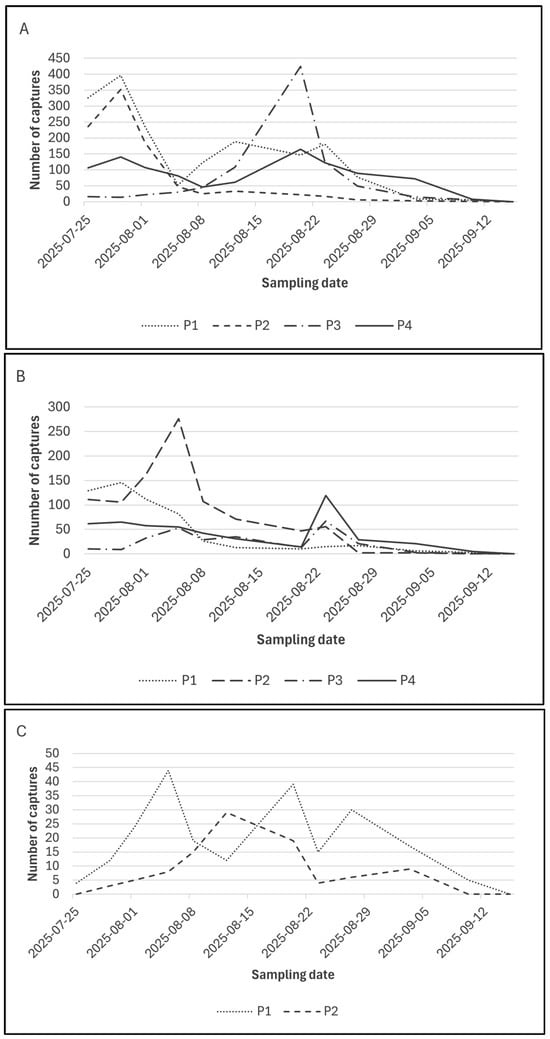

Differences between weekly distributions (Figure 2) and daily flight curves (Figure 3) reflect the different temporal aggregation levels of the data. Weekly boxplots may include extreme values arising from short periods of intense activity, whereas daily curves distribute these captures across multiple sampling dates.

Figure 3.

Seasonal flight dynamics of Diabrotica virgifera virgifera adults recorded with three monitoring systems across four maize plots during the 2025 growing season (25 July–15 September). (A) KLP+ pheromone traps detecting adult activity in Plots 1, 2, 3, and 4. (B) Baited Yellow Sticky Panels (YSP) showing adult captures in the same four plots. (C) iScout® automated monitoring system recording adults in Plot 1 (conventional) and Plot 2 (organic). Values represent the weekly number of adults captured at each sampling date. Plot 2 corresponds to the ecologically managed field, while Plots 1, 3, and 4 represent conventionally managed fields.

3.1.2. Comparative Evaluation of Capture Performance Among Trap Types

From mid-July to early September, adult flight activity showed a clear seasonal pattern across all monitoring sites and trap types, with a rapid increase during late July and early August followed by a gradual decline. While absolute capture levels differed substantially among plots, particularly in P3 where population density was markedly higher, all monitoring methods consistently reflected the same overall temporal trend. Differences among trap types primarily affected capture magnitude rather than the timing of seasonal peaks.

It should be noted that Figure 2 and Figure 3 address complementary aspects of the dataset: Figure 2 summarizes the distribution of weekly capture values, whereas Figure 3 illustrates seasonal dynamics across consecutive sampling events. Minor differences in apparent magnitude reflect differences in data aggregation and visualization rather than inconsistencies in the underlying dataset.

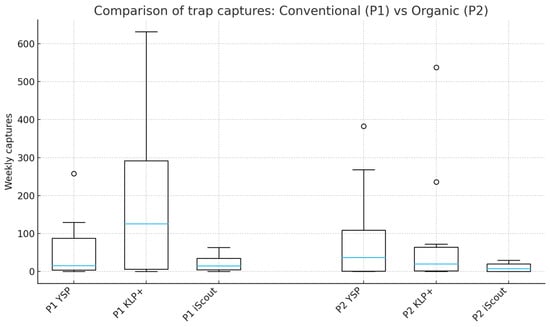

3.1.3. Descriptive Comparison of Capture Patterns Between Plots Under Different Management Practices

Weekly captures recorded in P1 (conventional) and P2 (organic) are presented in Figure 4. Both plots were monitored with identical trap types (YSP, KLP+, and iScout®), allowing a direct descriptive comparison between cultivation systems.

Figure 4.

Descriptive comparison of weekly adult captures of Diabrotica virgifera virgifera recorded in one conventional (P1) and one organic (P2) maize plot using three trap types. As only one plot per management system was available, the comparison is exploratory and descriptive and does not allow inference at the cultivation-system level.

For YSP traps, weekly captures ranged from 0 to 383 adults in both plots, with a weekly median of 36.5 adults (IQR: 0.5–109).

For KLP+ traps, weekly captures ranged from 0 to 538 adults, with a median of 19.5 adults (IQR: 1.5–63.75) in both P1 and P2.

For iScout® traps, weekly captures ranged from 0 to 29 adults, with a median of 7 individuals (IQR: 0–19.5) in both plots.

Across all three trap types, weekly capture distributions in P1 and P2 were numerically identical in terms of minimum, maximum, median, and dispersion parameters. As only one organic and one conventional plot were available, no statistical comparison was performed, and the results remain purely descriptive.

3.2. Weather-Driven Activity Patterns of D. v. virgifera Adults

Correlation coefficients are reported together with sample size (n) and p-values to allow assessment of their statistical robustness. Given the limited temporal replication, these analyses are presented as descriptive and exploratory rather than inferential.

Pearson correlation analyses were performed to assess the relationships between daily adult captures and three meteorological variables, mean air temperature, daily precipitation, and relative humidity, for each trap type and monitoring plot (Table 3). Overall, correlations were weak for the manual traps (YSP and KLP+), whereas clear associations were observed for the iScout® automated system.

Table 3.

Pearson correlations between trap captures and weather variables (n = 10 sampling dates).

For YSP traps, correlations with temperature ranged from –0.202 (P3) to 0.059 (P2), indicating no substantial linear response to short-term temperature fluctuations. Precipitation showed consistently negative coefficients (–0.169 to –0.042), suggesting slightly reduced YSP activity during rainy periods. Correlations with relative humidity were low and close to zero (–0.158 to 0.024), indicating minimal influence of RH on sticky-panel capture rates.

For KLP+ pheromone traps, temperature correlations were similarly weak, ranging from –0.179 (P1) to 0.102 (P2). Precipitation and RH also showed consistently low and negative correlations (precipitation: –0.122 to –0.032; RH: –0.094 to –0.001), indicating limited short-term sensitivity of pheromone trap captures to daily weather dynamics.

In contrast, iScout® automated traps exhibited higher Pearson correlation coefficients with selected meteorological variables; however, these associations should be interpreted cautiously. All correlation analyses were based on a limited number of sampling events (n = 10), and manual trap data represent weekly integrated captures rather than discrete daily responses. In the conventional plot (P1), iScout® captures showed high positive correlation coefficients with air temperature (r = 0.917) and precipitation (r = 0.959), and a weak negative association with relative humidity (r = −0.335). In the organic plot (P2), iScout® captures exhibited a positive correlation with precipitation (r = 0.877), a weak negative correlation with relative humidity (r = −0.355), and a near-zero correlation with temperature (r = −0.082).

These relationships are descriptive and exploratory in nature and likely reflect coincident seasonal trends rather than direct mechanistic responses. Consequently, the observed associations should not be interpreted as evidence of causality, but rather as indicative of the potential sensitivity of automated monitoring systems to short-term environmental variability under field conditions.

Exploratory correlation analyses were performed to examine associations between weekly trap captures and weekly meteorological variables (Figure 5). For the iScout® automated system, moderate to high positive associations were observed with weekly precipitation and air temperature in plots P1 and P2, while relationships with relative humidity were weaker and variable. For YSP and KLP+ traps, associations with meteorological variables were more dispersed and inconsistent across plots, reflecting the integrative nature of weekly manual sampling. Given the limited number of observations (n = 10 per plot) and the lack of temporal independence among weekly values, these correlations should be interpreted descriptively and do not imply causal relationships.

Figure 5.

Relationships between weekly trap captures of Diabrotica virgifera virgifera adults and meteorological variables during the monitoring period. Scatter plots illustrate associations between weekly trap captures and weekly mean air temperature (°C), weekly precipitation (mm), and weekly mean relative humidity (%). Panels (A–C) show iScout® automated trap captures in relation to temperature, precipitation, and relative humidity (plots P1 and P2). Panels (D–F) show Yellow Sticky Panel (YSP) captures in relation to temperature, precipitation, and relative humidity (plots P1–P4). Panels (G–I) show CSALOMON® KLP+ pheromone trap captures in relation to temperature, precipitation, and relative humidity (plots P1–P4). Each point represents one weekly observation; colors and symbols indicate individual monitoring plots.

Together, these results indicate that, under the weather conditions recorded during the monitoring period, manual traps showed only weak sensitivity to short-term meteorological fluctuations, whereas automated image-based monitoring captured high weather-linked variation, particularly in relation to precipitation.

3.3. Performance Evaluation of Trap Types

Across the entire monitoring period, the three trap types differed markedly in the total number of D. virgifera virgifera adults captured. To enable a standardized comparison, seasonal captures obtained by each device were expressed relative to the KLP+ pheromone trap, which was used as the reference method due to its established role in WCR monitoring programs.

Relative capture efficiencies are summarized in Table 4. KLP+ traps recorded the highest number of adults (4515 individuals; 100% reference efficiency). YSP traps captured 2273 adults, corresponding to 50.3% of the captures obtained with KLP+ traps. The iScout® automated trap system registered 319 adults, representing 7.1% of the reference level. These values reflect the proportional contribution of each trap type to the total number of adults detected during the study period and highlight the clear quantitative differences in capture performance across monitoring devices.

Table 4.

Relative efficiency (%) of each trap type expressed as total seasonal captures relative to the KLP+ trap.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings and Interpretation

Consistent differences in capture magnitude were observed among trap types across monitoring sites; however, these differences are presented descriptively and reflect contrasting trap mechanisms and sampling resolution rather than statistically tested performance rankings. Across all plots, CSALOMON® KLP+ traps recorded the highest number of adults, confirming their established reliability for quantitative WCR monitoring [2,10,11,21,24]. Yellow sticky panels (YSP) captured approximately half as many adults as KLP+ traps, yet they reproduced the main seasonal activity curves, consistent with earlier studies emphasizing the temporal stability of visual traps [20,22,23]. Although the iScout® automated trap captured fewer individuals in absolute terms, it accurately reflected the timing of seasonal peaks and provided continuous digital records, underscoring its utility for real-time field surveillance [13,29,30,31,32,33].

Relative capture proportion can be explained by their attractant mechanisms (pheromone + floral lures for KLP+, plant-volatile-based lures for YSP, and pheromone-equipped adhesive boards combined with automated imaging for iScout®), with each mediating beetle responsiveness differently [11,12,25,26,27,28].

Cumulative capture curves further indicated that manual traps (KLP+ and YSP) reached 50% of their seasonal totals earlier than the automated device. A similar temporal lag in automated imaging systems has been reported under fluctuating humidity conditions, where image recognition or insect mobility may be affected [29,30,31,32,33].

Correlation analysis showed that day-to-day weather variation explained only a modest portion of short-term capture variability. For KLP+ and YSP traps, temperature, precipitation, and relative humidity exhibited uniformly weak associations with captures, reflecting the limited sensitivity of manual traps to microclimatic fluctuations and the predominant influence of adult emergence patterns and local population density [8,12,19,22]. For iScout® traps, positive correlations with precipitation were detected in both plots, while temperature and relative humidity showed weaker or inconsistent associations. These findings suggest that automated systems may be more sensitive to short-term environmental fluctuations, although their performance remains influenced by weather-dependent insect activity and image quality constraints [29,30,31,32,33].

The markedly higher captures recorded in plot P3 should be interpreted with caution. While they indicate elevated adult activity at this site, such differences may also be influenced by site-specific confounding factors, including crop management practices, soil properties, and surrounding landscape context, which were not experimentally controlled in the present study. Therefore, spatial differences among plots are reported descriptively and do not imply causal attribution to population dynamics alone.

Overall, the results indicate that while weather contributes to seasonal emergence timing, same-day meteorological factors exert limited influence on daily trap counts compared with biological and agronomic drivers.

Although several previous studies have independently evaluated pheromone traps, sticky panels, or automated monitoring tools for Diabrotica virgifera virgifera, direct side-by-side comparisons of these approaches under identical field conditions remain limited. The present study does not aim to introduce a novel trap design or to redefine established monitoring thresholds. Instead, its main contribution lies in the parallel evaluation of three commonly used monitoring approaches, manual sticky panels, pheromone traps, and a commercially available automated digital system, operated simultaneously within the same maize fields and over the same seasonal window.

By applying all monitoring tools in real production fields and under practical constraints (e.g., limited spatial replication, variable connectivity, and routine weekly inspections), this study provides an applied assessment of how these systems perform relative to each other rather than in isolation. In particular, it highlights how automated traps complement, rather than replace, conventional monitoring by offering higher temporal resolution and remote field visibility, while still relying on established manual traps for quantitative population assessment.

4.2. Comparison with Previous Studies

Seasonal activity patterns recorded here align with those reported across Central and Eastern Europe, where D. v. virgifera adult flight typically peaks from late July to late August [8,19,23,24,55]. The two-peak pattern observed, an early rise immediately after trap installation followed by a broader mid-August maximum, is consistent with the staggered emergence documented in previous studies [9,18,25,56,57].

The superior performance of KLP+ traps matches earlier reports by Tóth et al. [10,11,24] and Bažok et al. [2], while the lower but temporally consistent captures of YSP traps correspond well with findings by Kiss et al. [20,22]. Applications of automated imaging systems to WCR remain limited, but our results complement existing evaluations of digital traps for other pest species [13,29,30,31,32,33], showing that automated devices can accurately reflect flight dynamics even when their absolute capture numbers are lower.

Although several studies reported associations between weather variables and WCR emergence at broader temporal scales [8,12,15,16], our daily-resolution dataset revealed only weak or inconsistent correlations, similar to findings from field-based monitoring under variable conditions [23,24,58,59]. This supports the view that microclimate influences short-term mobility less than population phenology or field-level heterogeneity.

The comparison between organically and conventionally managed plots should be interpreted with caution. As only one organic field was monitored, observed differences may reflect site-specific factors rather than management system effects. Therefore, results are presented as a descriptive case comparison rather than evidence of system-level differences.

4.3. Practical Implications for IPM

Action thresholds reported in the literature are currently available only for KLP+ pheromone-floral traps and are therefore trap-specific. These thresholds cannot be directly transferred to other monitoring systems, such as yellow sticky panels or automated imaging-based traps, due to substantial differences in trap design, attractant type, and capture efficiency [10,11,12,21,24].

Accordingly, capture data obtained from YSP and iScout® traps in this study should be interpreted primarily as indicators of relative adult activity, seasonal flight dynamics, and temporal changes in population pressure, rather than as direct triggers for management actions [29,30,31,32,33]. At present, automated trap outputs cannot be directly translated into actionable management thresholds, as device-specific economic thresholds have not yet been established.

The integration of automated traps into decision-support frameworks will require the development and validation of device-specific thresholds, ideally through multi-year field calibration against established reference traps and agronomic outcomes, including crop damage and yield loss [18,20,25,27,60,61,62].

Trap captures should be interpreted as relative indicators of adult activity rather than direct predictors of yield loss. For Diabrotica virgifera virgifera, adult monitoring is primarily used to assess flight dynamics, population pressure, and temporal risk windows for egg-laying, which inform management decisions in subsequent seasons. Consequently, capture values such as 40 or 3000 adults per trap do not translate directly into immediate intervention thresholds, but instead signal differences in population intensity and spatial heterogeneity among fields.

Although the automated iScout® system recorded lower capture numbers compared to pheromone-based traps, its value lies in temporal resolution and remote accessibility rather than capture efficiency. Continuous image-based monitoring allows near real-time detection of adult presence and activity trends, reducing the need for frequent field visits and enabling earlier situational awareness, particularly in large-scale or logistically constrained farming systems. However, the present results also indicate that further technical refinement and pest-specific calibration are required before automated systems can replace conventional monitoring tools for decision-making purposes.

4.4. Methodological Limitations

Because traps were installed after the onset of adult emergence, the earliest phase of flight activity was not captured. However, the monitoring period encompassed the main activity window, when population density and trap responsiveness are highest.

Meteorological data were obtained from nearby weather stations rather than on-site sensors, potentially introducing small spatial discrepancies in temperature or rainfall. The performance of automated traps was occasionally affected by unstable GPRS connectivity, which influenced real-time data transmission but did not affect the comparative ranking of trap types. These limitations are typical of field-based entomological studies and do not compromise the robustness of the comparative findings.

4.5. Future Research Directions

Future work should extend this monitoring approach across multiple growing seasons to better capture interannual variation in population dynamics and weather influences [12,15]. Integrating automated trap data with degree-day models, remote-sensing indicators, or machine-learning algorithms could improve predictive capacity for WCR monitoring and enhance decision-support tools [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,60,61,62].

Further improvements in automated trap networks will depend on resolving GSM/GPRS connectivity issues in remote fields, as noted for other IoT-based surveillance systems [30,31,32,33,63,64]. Enhancing onboard data storage, signal amplification, and image-recognition performance, particularly under high humidity, will be essential steps toward fully automated, regional-scale pest monitoring systems that support precision IPM under changing climatic conditions [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,65,66].

Therefore, the novelty of this work lies not in demonstrating the superiority of one trap over another, but in illustrating how different monitoring tools provide complementary information when used together within an integrated pest management framework. This integrated perspective is particularly relevant for regions where automated systems are increasingly available but where their role in decision support remains insufficiently defined.

Visual and olfactory stimuli play a critical role in western corn rootworm attraction. Prior studies demonstrate that color contrast and lure composition can significantly affect trap efficiency. Our findings reflect cumulative responses to combined physical and chemical cues inherent to each trap type, but disentangling the specific effects of trap color versus lure chemistry is beyond the scope of the current observational field study. Future research should incorporate controlled manipulations of trap color and lure type to determine their independent and interactive effects on adult WCR captures. Also, should integrate degree-day models with automated monitoring systems to improve prediction of adult emergence and flight dynamics. Therefore, while automated traps offer advantages in temporal resolution and data continuity, their apparent sensitivity to weather variables in this study should be considered exploratory. Future studies using time-series analyses or mixed-effects models are required to disentangle true biological responses from seasonal trends.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that manual and automated monitoring systems provide complementary but not interchangeable information on adult activity of D. virgifera virgifera. While pheromone-based KLP+ traps remain the most reliable tools for quantitative population assessment and supporting monitoring strategies, automated imaging systems such as iScout® currently function best as exploratory or early-warning tools.

Given their financial cost and lower capture efficiency, automated systems require further technical optimization and pest-specific calibration before they can support independent management decisions. Future research should focus on linking automated trap outputs to crop damage, yield loss, and established economic thresholds to improve their relevance for practical IPM implementation.

While automated monitoring systems offer clear advantages in terms of temporal resolution and remote data access, their effective use in IPM decision-making will depend on the establishment of validation. At present, automated traps should be regarded as complementary tools that enhance situational awareness rather than as standalone decision instruments.

Further research should focus on dissecting the relative contributions of trap color, panel design, and lure composition to capture performance. Controlled experiments that systematically vary these factors would clarify mechanisms underpinning trap effectiveness and enhance the utility of monitoring strategies across diverse agroecosystems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture16010096/s1, Table S1. Weekly descriptive statistics (mean, median, min, max, IQR, and number of weeks) for adult captures across trap types and plots.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.P. and I.G.; methodology, I.G. and D.M.P.; software, D.M.P.; validation, I.G.; formal analysis, I.G.; investigation, D.M.P.; resources, I.G. and D.M.P.; data curation, D.M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.P. and I.G.; writing—review and editing, I.G.; visualization, I.G. and D.M.P.; supervision, I.G.; project administration, I.G.; funding acquisition, D.M.P. and I.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication of the present paper was supported by the University of Life Sciences “King Mihai I” from Timisoara, Romania.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are part of an ongoing doctoral research project and are not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the local farm managers and landowners in Bihor County for granting access to their maize fields and allowing the installation and maintenance of the monitoring devices throughout the study period. Their cooperation and support were essential for conducting the field experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DvvLC | Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte |

| IPM | Integrated Pest Management |

| YSP | Yellow Sticky Panel trap |

| KLP+ | CSALOMON® KLP pheromone + floral attractant trap |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization Crop Maturity Group |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| GPRS | General Packet Radio Service |

| LED | Light Emitting Diode |

| T–Rh | Temperature–Relative Humidity |

| LOESS | Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing |

| iScout® | Automated remote digital monitoring trap |

| WCR | Western Corn Rootworm |

References

- Bazok, R.; Lemic, D.; Chiarini, F.; Furlan, L. Western Corn Rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte) in Europe: Current Status and Sustainable Pest Management. Insects 2021, 12, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinke, L.J.; Sappington, T.W.; Onstad, D.W.; Guillemaud, T.; Miller, N.J.; Komaromi, J.; Levay, N.; Furlan, L.; Kiss, J. Western Corn Rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte) Population Dynamics. Agric. For. Entomol. 2009, 11, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinke, L.J.; Spomer, S.M.; Naranjo, S.E.; Sappington, T.W. Adaptation and Invasiveness of Western Corn Rootworm. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2009, 54, 303–321. [Google Scholar]

- Ciosi, M.; Miller, N.J.; Kim, K.S.; Giordano, R.; Estoup, A.; Guillemaud, T. Invasion of Europe by the Western Corn Rootworm. Mol. Ecol. 2008, 17, 3614–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon, P.; Lobo, J.M.; Romo, H. Global Estimation of Invasion Risk Zones for the Western Corn Rootworm. J. Appl. Ecol. 2010, 47, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.L.; Hibbard, B.E.; Moeser, J.; Onstad, D.W. Behavior and Ecology of the Western Corn Rootworm. Agric. For. Entomol. 2009, 11, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPPO. PM 7/36 (2) Diabrotica virgifera virgifera. EPPO Bull. 2017, 47, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, S.; Kuhlmann, U.; Edwards, C.R. Western Corn Rootworm: Ecology and Management; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Obasa, K.; Santiago-Gonzalez, J. Western Corn Rootworm and Southern Corn Rootworm Identified as Vectors of Pantoea ananatis. Crops 2025, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toepfer, S.; Kuhlmann, U. Survey for Natural Enemies of the Invasive Alien Chrysomelid Diabrotica virgifera virgifera in Central Europe. Biocontrol 2004, 49, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toepfer, S.; Gueldenzoph, C.; Ehlers, R.U.; Kuhlmann, U. Screening of Entomopathogenic Nematodes for Virulence against Diabrotica virgifera virgifera. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2005, 95, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeser, J.; Vidal, S. Do Alternative Host Plants Enhance the Invasion of the Maize Pest Diabrotica virgifera virgifera in Europe? Environ. Entomol. 2004, 33, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, L.; Furlan, L.; Toth, M.; Steinger, T.; Carrasco, L.R.; Toepfer, S. Efficiency of Pheromone Traps for Monitoring Diabrotica virgifera virgifera. EPPO Bull. 2011, 41, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshova, T.B.; Velchev, D.I.; Abaev, V.D.; Subchev, M.A.; Atanasova, D.Y.; Toth, M. Detection and Monitoring of Diabrotica virgifera virgifera in Bulgaria Using KLP+ Traps Baited with Dual Lures. Acta Zool. Bulg. 2017, 9, 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Toth, M.; Imrei, Z.; Schaub, L.; Furlan, L. ‘Hat’ Trap with Semiochemical Lures Suitable for Trapping Diabrotica spp. J. Pest Sci. 2014, 87, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Hemerik, L.; Busstra, C.; Mols, P. Predicting the Temperature-Dependent Natural Population Expansion of the Western Corn Rootworm. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2004, 111, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streda, T.; Vahala, O.; Stredova, H. Prediction of Adult Western Corn Rootworm Emergence. Plant Protect. Sci. 2012, 49, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos, T.; Gunjaca, J.; Igrc Barcic, J. Western Corn Rootworm Adult Captures as a Tool for Larval Damage Prediction in Continuous Maize. J. Appl. Entomol. 2014, 138, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, G.L.; Tollefson, J.J.; Calvin, D.D. Comparison of Adult Corn Rootworm Trapping Techniques. Environ. Entomol. 1984, 13, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhar, T.P.; Youngman, R.R. Olson Yellow Sticky Trap: Decision-Making Tool for Sampling Western Corn Rootworm Adults in Field Corn. J. Econ. Entomol. 1998, 91, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imrei, Z.; Toth, M. A Review of Different Trapping Methods and Purposes for Diabrotica virgifera virgifera. J. Kult. Pflanzen 2014, 444, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Beres, P.K.; Drzewiecki, S.; Nakonieczny, M.; Tarnawska, M.; Guzik, J.; Migula, P. Population Dynamics of Western Corn Rootworm Beetles on Different Varieties of Maize Identified Using Pheromone and Floral-Baited Traps. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 153, 1479–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazok, R.; Igrc Barcic, J.; Edwards, C.R. Effects of Proteinase Inhibitors on Western Corn Rootworm Life Parameters. J. Appl. Entomol. 2005, 129, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toepfer, S.; Levay, N.; Kiss, J. Adult Movements of Newly Introduced Western Corn Rootworm. J. Appl. Entomol. 2006, 130, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wudtke, A.; Hummel, H.; Ulrichs, C. The Western Corn Rootworm en Route to Germany. Gesunde Pflanz. 2005, 57, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igrc Barcic, J.; Bazok, R.; Maceljski, M. Research on the Western Corn Rootworm in Croatia (1994–2003). Entomol. Croat. 2003, 7, 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Schaumann, W.; Shaw, J.T.; Hummel, H.E. Monitoring Trap for Diabrotica virgifera virgifera Adults Lured with Poisoned Cucurbitacin Bait. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2003, 68, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, Z.; Tóth, M.; Jósvai, J.K.; Tóth, F.; Flórián, N.; Gergocs, V.; Dombos, M. Automatic Field Detection of Western Corn Rootworm with a New Probe. Insects 2020, 11, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preti, M.; Verheggen, F.; Angeli, S. Insect Pest Monitoring with Camera-Equipped Traps: Strengths and Limitations. J. Pest Sci. 2021, 94, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.C.; Ribeiro, J.; Morais, R.; Sousa, J.J.; Cunha, A. A Systematic Review on Automatic Insect Detection Using Deep Learning. Agriculture 2023, 13, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Liu, S.; Luo, H.; Feng, Z.; Yang, B.; Luo, J.; Tang, J.; Yao, Q.; Xu, J. Intelligent Monitoring System of Migratory Pests Based on Machine Vision. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 897739. [Google Scholar]

- Okuyama, T. Using Automated Monitoring Systems to Uncover Pest Population Dynamics. Agric. Syst. 2011, 104, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Dong, D.; Wang, K. Real-Time Monitoring of Insects Based on Laser Remote Sensing. Ecol. Indicat. 2023, 151, 110302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Aparicio, A.; Llorens, J.; Rosell-Polo, J.R.; Martí, J.; Gemeno, C. A Low-Cost Electronic Sensor Automated Trap for Monitoring Flying Insects. Eur. J. Entomol. 2021, 118, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagan, L.; Rosca, I. Seasonal Dispersal of Western Corn Rootworm Adults in Bt and Non-Bt Maize. Plant Protect. Sci. 2012, 48, S36–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashev, S.; Palagacheva, N.; Ivanova, S.; Georgiev, S. Western Corn Rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte): Appearance and Distribution in Central-South Bulgaria. Sci. Pap. Ser. A Agron. 2024, LXVII, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kos, T.; Bazok, R.; Varga, B.; Igrc Barčić, J. Estimation of Western Corn Rootworm Egg Abundance Based on Previous Year Adult Capture. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2013, 14, 1488–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beres, P.K. Economic Importance and Control of Western Corn Rootworm in Poland. Prog. Plant Prot. 2013, 53, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gyeraj, A.; Szalai, M.; Palinkas, Z.; Edwards, C.R.; Kiss, J. Effects of Adult Western Corn Rootworm Silk Feeding on Yield Parameters of Sweet Maize. Crop Prot. 2020, 127, 104965. [Google Scholar]

- Trapview. Real-Time Smart Pest Monitoring and Forecasting; Trapview Technical Brochure: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pessl Instruments. iSCOUT Optical High-Resolution Camera Trap for Precision Insect Monitoring; Pessl Instruments GmbH: Weiz, Austria, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- ZooLog Sensor System. Automated Online Monitoring of Insects with Sensor-Equipped Pheromone Traps; EU CAP Network Leaflet: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Horgos, H.; Grozea, I. The Current Assessment of the Structure of Diabrotica Virgifera (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Populations and the Possible Correlation of Adult Coloristic with the Type and Composition of Ingested Maize Plants. Rom. Agric. Res. 2020, 37, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amargioalei, R.G.; Pintilie, P.L.; Trotus, E.; Pintilie, A.S.; Herea, M.; Talmaciu, M. Flight Dynamics of Diabrotica virgifera virgifera in Maize Crops in Central Moldova, 2021–2023. Sci. Pap. Ser. A Agron. 2024, 67, 260–265. [Google Scholar]

- Costea, M.-A.; Grozea, I. Analysis of the Range of Pests and Their Effect on Maize Plants Growing in the Organic System. Sci. Pap. Ser. A Agron. 2022, LXV, 259–265. [Google Scholar]

- Purice, D.M.; Grozea, I. Review of Traps Used to Capture Adults of Diabrotica virgifera in Corn Crops. Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2024, 56, 228–233. [Google Scholar]

- Costea, M.A.; Konjević, A.; Grozea, I. Biological Solutions for The Management of Pests in Corn Crops. AgroLife Sci. J. 2023, 12, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, E.; Toader, M.; Caniă, L.; Partal, E.; Bordei, M.; Manole, M.S. The Western Corn Rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera Le Conte) Population Is Increasing in the Southeast of Romania. Sci. Pap. Ser. A Agron. 2025, LXVIII, 363–370. [Google Scholar]

- Suto, J. Codling Moth Monitoring with Camera-Equipped Traps in Apple Orchards: Implications for Automatic Pest Monitoring. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onstad, D.W. Modeling the Spread and Management of Western Corn Rootworm. J. Econ. Entomol. 2008, 101, 181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M.E.; Steffey, K.L.; Estes, R.E.; Schroeder, J.B. Corn Rootworm Management and Bt Maize: Developments and Discoveries. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2016, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard, B.E.; Meihls, L.N.; Ellersieck, M.R.; Onstad, D.W. Adult Emergence Patterns of Western Corn Rootworm in Field Conditions. J. Econ. Entomol. 2010, 103, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, E.; Oloumi-Sadeghi, H. Management of Diabroticite Rootworms in Corn. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1991, 36, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.J.; Estoup, A.; Toepfer, S.; Bourguet, D.; Lapchin, L.; Derridj, S.; Kim, K.S.; Reynaud, P.; Furlan, L.; Guillemaud, T. Multiple Transatlantic Introductions of the Western Corn Rootworm. Biol. Invasions 2005, 7, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiss, J.; Edwards, C.R.; Berger, H.K.; Cate, P.; Cean, M.; Cheek, S.; Derron, J.; Festić, H.; Furlan, L.; Igrc-Barčić, J.; et al. Monitoring of Western Corn Rootworm in Europe. J. Appl. Entomol. 2005, 129, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Toth, M. Development of Synthetic Lures for Chrysomelid Beetles. Int. Org. Biol. Control WPRS Bull. 2010, 50, 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Mrganić, M.; Bažok, R.; Mikac, K.M.; Benítez, H.A.; Lemic, D. Two Decades of Invasive Western Corn Rootworm Population Monitoring in Croatia. Insects 2018, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon, P.; Logo, J.M. Predicted effect of climate change on the invasibility and distribution of the Western corn root-worm. Agric. For. Entomol. 2012, 14, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozea, I.; Purice, D.M.; Damianov, S.; Molnar, L.; Grozea, A.; Virteiu, A.M. Predicting the Potential Spread of Diabrotica virgifera virgifera in Europe Using Climate-Based Spatial Risk Modeling. Insects 2025, 16, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cortés, S.; Menéndez-Díaz, A.; Bande-Castro, M.J.; Carballal-Samalea, A.; Martínez-Fernández, A.; Oliveira-Prendes, J.A. A machine learning approach for estimating forage maize yield and quality in NW Spain. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noskov, A.; Bendix, J.; Friess, N.A. Review of Insect Monitoring Approaches with Special Reference to Radar Techniques. Sensors 2021, 21, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, M.F.; Mao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Elmasry, G.; Awad, M.A.; Abdalla, A.; Mousa, S.; Elwakeel, A.E.; Elsherbiny, O. Emerging Technologies for Precision Crop Management Towards Agriculture 5.0: A Comprehensive Overview. Agriculture 2025, 15, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-López, F.R.; Jiménez-López, A.F.; García-Ramírez, D.Y. Intelligent System for Integrated Pest Management in Agriculture: An electronic approach to Sustainable Farming. Visión Electrónica 2024, 18, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komala, G.; Manda, R.R.; Seram, D. Role of Semiochemicals in Integrated Pest Management. Int. J. Entomol. Res. 2021, 6, 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, D.; Rafiq, S.; Saini, P.; Ahad, I.; Gonal, B.; Rehman, S.A.; Rashid, S.; Saini, P.; Rohela, G.K.; Aulum, K.; et al. Remote Sensing and Artificial Intelligence: Revolutionizing Pest Management in Agriculture. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1551460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassman, K.G. Ecological Intensification of Maize-Based Cropping Systems. Better Crops 2017, 101, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.