Abstract

The need for more sustainable agriculture less dependent on mineral fertilizers has intensified the interest in the reuse of agro-industrial by-products as alternative nutrient sources. This study investigates the agronomic potential of citrus sewage sludge (CSS), derived from citrus wastewater treatment, as a nitrogen (N) source for wheat cultivation. An experiment was conducted using two Mediterranean soils with contrasting physicochemical properties, comparing a non-fertilized control (CTR), inorganic N fertilization (NH4NO3) (CTR + N), and CSS; fertilizers were applied once at 30 mg of N per plant. Differences in soil organic carbon availability and C/N ratio, together with carbonate-related properties, influenced N dynamics in the soil–plant system. In the soil with higher oxidizable organic C and a more favorable C/N ratio (S1), CSS increased soil ammonium concentrations by about 70% compared with the control and by nearly 50% compared with the soil characterized by lower organic C availability (S2). In S2, the lower concentrations of both NH4+ and NO3− indicate reduced microbial mineralization and nitrification, consistent with its lower availability of readily degradable organic carbon. Moreover, wheat grown with CSS exhibited a total biomass about 40% higher than that of the CTR. The Mineral Fertilizer Replacement Value (MFRV) reached 73% in S1 and 46% in S2, confirming the potential of CSS as a sustainable N source, particularly in soils where organic C availability supports microbial activity and N transformations. Future strategies should focus on improving CSS use through specific soil management practices.

1. Introduction

Global population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050 [1], which will imply an increased food demand. To meet this demand, it is necessary that global agricultural production increases by 70–100%, taking into account expected changes in diet composition, consumption levels, and income growth. These socio-economic changes are not only boosting food demand, but also redefining expectations in terms of food quality, sustainability, and equity [2]. The pandemic and the climate crisis have exerted unprecedented pressure on global food systems. These interconnected challenges require integrated solutions, as sustainable and inclusive food systems are fundamental to peace and stability. The pressing need to increase food production has intensified global dependence on fertilizers, which are essential for maintaining crop yields due to their stable nutrient concentrations [3,4]. Moreover, the cost of fertilizers, which has remained consistently high since March 2020, has led to a significant decrease in wheat (−30%), maize (−15%) and sunflower (−70%) production, further threatening global food security [5,6]. Nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) are needed in great amounts, but significant quantities are lost in waste streams. It is estimated that 22 million Mg of N are lost each year [5]. In addition, the traditional intensive use of chemical fertilizers in many regions of the world has raised serious environmental and agronomic concerns. Prolonged application reduces soil organic matter (SOM) and contributes to pollution [7]; however, this effect varies depending on management practices [8]. The high salt content in these fertilizers can damage both plants and soil, leading to long-term degradation of soil fertility [9]. In contrast, the nutrients contained in organic fertilizers must first be mineralized by soil microorganisms before they become available to plants. Long-term supply of organic fertilizers improves soil properties by promoting the accumulation of organic matter, in turn increasing carbon pools with slower turnover rates [10]. This issue is particularly critical in arid and semi-arid areas of the Mediterranean, where decades of intensive agricultural practices have degraded soil fertility to levels that threaten long-term agricultural productivity. Therefore, a transition to more sustainable practices is essential. In this context, identifying renewable organic sources for reuse as fertilizers can contribute to nutrient cycling, decreasing the dependence on mineral fertilizers and sustainable soil management.

Citrus fruits are cultivated in over 140 countries worldwide and most are intended for human consumption. Globally, citrus production is dominated by sweet oranges (65%), followed by tangerines (19%), lemons and limes (11%), and grapefruit (5%) [11]. In this context, Mediterranean countries play a leading role as major producers of fresh citrus fruits for the international market [12]. On average, over 20% of total citrus fruit production is processed industrially, mainly for the extraction of juices and essential oils (EO) [13]. These processes generate two main by-products: a solid or semi-solid fraction, consisting of peel and fruit residues, and citrus wastewater (CWW). The CWW is typically sent to wastewater treatment plants for disposal, as required by environmental legislation (e.g., Directive 91/271/EEC on urban wastewater treatment and subsequent national implementations). During treatment, the resulting citrus sewage sludge (CSS), rich in N and organic matter, represents a potentially valuable resource [14]. If managed and treated appropriately to ensure safety, CSS could be recovered and reused in agricultural systems as organic soil improvers or fertilizer alternatives, contributing to nutrient recycling and promoting more sustainable waste management practices [15]. Indeed, CSS are characterized by subalkaline pH, high electrical conductivity (however, lower than 4 dS m−1), and contains, on average, 255 g kg−1 of total organic carbon (TOC) and 40 g kg−1 of N [16]. The application of CSS can significantly improve the availability of N for plant uptake, while increasing soil organic carbon [17,18,19]. However, the efficiency with which CSS release plant-available N is expected to vary depending on soil characteristics that control the microbial degradation of organic matter, such as organic C availability, C/N ratio, and carbonate-related buffering capacity [20]. This effect is particularly valuable in arid and semi-arid regions where organic matter is constantly declining. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the fertilizer potential of CSS in two soils with contrasting properties, particularly in terms of organic carbon availability, C/N ratio and carbonate content, and to assess how these soil characteristics influence the mineralization of CSS-derived nitrogen and its uptake by wheat plants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soils

Two Mediterranean soils were collected and prepared for the experiment. According to the USDA Soil Taxonomy [21], soil S1 was classified as Inceptisol while soil S2 as Alfisol. The main soil properties are detailed in Table 1. The characterization of the two soils was carried out using standard analytical procedures. Reaction and electrical conductivity (EC) were measured in a 1:2.5 (w/v) soil-to-water suspension. Oxidable organic carbon was determined by the Walkley–Black wet oxidation method [22]. Total carbonates were quantified by a volumetric calcimeter method, while active carbonate was measured following standard titrimetric procedures. Soil nitrate was determined by the second-derivative spectrophotometric method [23] and ammonium was measured according to Mulvaney [24]. Total N was determined by the Kjeldahl digestion method [25]. Available P was assessed by the Olsen method [26] and P in the resulting bicarbonate extracts quantified colorimetrically according to Murphy and Riley [27]. The cation exchange capacity was measured using the ammonium acetate method.

Table 1.

Main chemical properties of the soil used for the experiment.

2.2. Citrus Sewage Sludge Characterization and Chemical Properties

Citrus wastewater treatment plants generate a large amount of sludge that differ in quantity and chemical composition. This sludge generally contains organic matter, macronutrients (such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium), heavy metals, organic microcontaminants (such as pharmaceuticals and pesticides), and a diverse range of microorganisms, both beneficial and harmful [14].

Citrus sewage sludge used in this study were collected from a citrus processing industry (Agrumaria Corleone Spa, Palermo, Italy). These consisted of the waste produced by the wastewater treatment process of the citrus industry. The CSS used in this study derived from the aerobic digestion step of the citrus wastewater treatment process, in which microorganisms oxidize and stabilize the organic fraction before sludge dewatering.

2.3. Citrus Sewage Sludge Analyses

CSS were air-dried before analysis and subsequently characterized to determine their main chemical properties. Reaction and electrical conductivity (1:2.5, w/v) were determined by a pH meter (FiveEasy, Mettler Toledo Spa, Milan, Italy) and a conductometer (HI5321, Hanna Instruments Italia Srl, Padua, Italy), respectively. Total nitrogen (TN) and carbon were determined using a CHN-analyzer (Perkin–Elmer 2400 CHNS/O elemental analyzer, New York, NY, USA). To determine total phosphorus (Total P), 0.25 g of pulverized CSS material underwent mineralization in porcelain crucibles by a muffle furnace at 550 °C for 8 h. The ashes were later recovered through acid digestion using 10 mL of 1 M HCl on a hot plate at 100 °C for 15 min. The digested samples were recovered in 15 mL tubes and adjusted to a volume of 10 mL with MilliQ water. The amount of P was determined by the colorimetric method of Murphy and Riley [27].

The content of macronutrients and heavy metals in CSS was determined by microwave plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (MP-AES) (Agilent 4210 MP-AES, Milan, Italy) following CSS mineralization by wet digestion procedure (2% HNO3 and 30% H2O2). Briefly, 0.5 g of CSS were weighed into a porcelain crucible and placed in a cool muffles furnace. The furnace temperature was set to reach 550 °C in about 2 h and samples were left to stand overnight. Then, samples were removed and, after cooling, 5 mL of 2% HNO3 and 5 mL of 30% H2O2 were added. Then, they were placed in a hot plate at 250 °C for 2 h and, if needed, the addition of 2% HNO3 and 30% H2O2 was repeated. After cooling, the digested sample was transferred quantitatively to a volumetric flask and brought to a 20 mL volume with 2% HNO3 [28]. As and Hg were not determined since they were absent in the raw materials.

2.4. Experimental Design and Setup

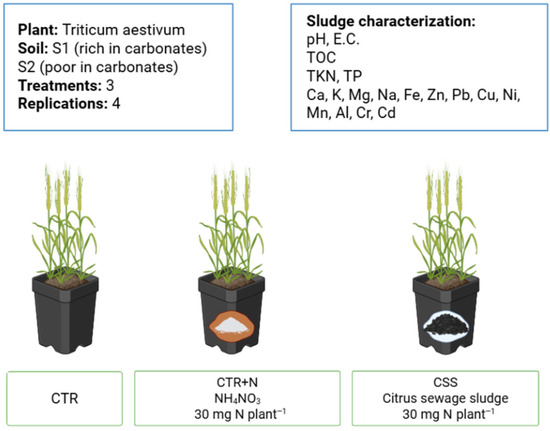

The experiment was carried out in a growth chamber located at the Higher Technical School of Agricultural Engineering (ETSIA) of the University of Seville (Spain). Black plastic pots (10 × 20 cm) with a capacity of 1 L were used. The growing media was prepared by mixing 950 g of soil, previously sieved at 4 mm and homogenized, with 25% perlite of the total volume. Wheat crop was selected for this experiment because of its global importance as an agricultural crop and for its sensitivity to N input. Wheat seeds were pregerminated by sowing in a nursery for 4 days at 4 °C, moistened with distilled water and 0.1 M CaCl2 to prevent root rot. After that, four seeds were transplanted into each pot containing soil already mixed with CSS. Inorganic fertilizer (NH4NO3) or CSS were mixed with soil at a rate of 30 mg of N per plant. This corresponded to the addition of approximately 2.3 g CSS kg−1 soil and 0.4 g NH4NO3 per pot. Not fertilized soil was used as control. Eight pots per treatment were set up (n = 4). The pots were placed in the growing chamber with 16 h of light at 22 °C and 40% relative humidity, and 8 h of darkness at 18 °C and 60% relative humidity, with a light intensity of 22 w m−2. Irrigation was applied to maintain soil water holding capacity at about 70%. Within the first two days of transplanting the wheat seedlings, irrigation was conducted only with water, after which modified Hoagland solution, N-free, was applied on a regular basis [29].

The experiment was designed as a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) including two soils (S1 and S2), three treatments (CTR, CTR + N, and CSS), and four replicates per treatment. Each pot contained four wheat plants, resulting in 12 pots per soil (24 pots in total).

The growth experiment lasted 80 days.

2.5. Soil Analyses

At the end of the experiment, the soil and plants of each pot were separated to be analyzed. Soil samples were separated from plant root apparatus by shaking off soils from wheat roots. Then, the soil of each pot was fully mixed, air-dried, and sieved at <2 mm and stored for further analyses. Soil ammonium (NH4+) and nitrate (NO3−) were determined on soil extracts performed with 2 M KCl. In brief, 2 g of soil was end-over-end shaken with 20 mL of extractant in polyethylene falcon tubes of 50 mL, at 180 rpm for 30 min. Soil NH4+ and NO3- were quantified through colorimetric analysis employing the Berthelot method [24] and the Spectroquant® Nitrate test, using a spectrophotometer (UVmini-1240, Shimadzu Italia Srl, Milan, Italy) after the formation of a yellow-green and red complex, respectively. β-glucosidase activity was determined on soil samples previously stored at −20 °C. The activity of soil β-glucosidase was determined by measuring the amount of p-nitrophenol formed from 4-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside, following the method of Eivazi and Tabatabai [30] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scheme of the experimental design.

2.6. Plant Analyses

Root and shoot samples were first washed with tap water and then with distilled water oven-dried at 65 °C for 72 h and dry weight noted. Then, roots, stems, gluma, and wheat grain were collected separately and ground using a small laboratory mill (Retsch GM 200, Haan, Germany) until a fine, homogeneous powder was obtained (<1 mm particle size) for subsequent analysis. The N concentration in plant tissues was determined using the Dumas Method [31] by the CNS-Trumac Elemental Autoanalyzer by LECO (Milan, Italy). Tissue N concentrations were used to calculate total plant N uptake and the Mineral Fertilizer Replacement Value (MFRV).

Nitrogen uptake was calculated as the sum of the N uptake of each plant organ, obtained by multiplying the dry weight of each organ by its N concentration. By using N uptake, the replacement value of the alternative fertilizer products, CSS, (MFRV—Mineral Fertilizer Replacement Value) was calculated as reported by Ayeyemi et al. [32] from the amount of commercial mineral N fertilizer saved or replaced when using an alternative fertilizer while achieving the same N uptake or yield. It can be interpreted as the percentage of commercial mineral fertilizer that alternative fertilizers can replace. It was estimated based on each application of Equation (1):

where is the by the crop in the treatment with alternative fertilizer is the average in the non-fertilized control treatment, and is the average N uptake in the mineral fertilizer treatment at the same N rate as .

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Reported values are the arithmetic mean ± standard deviations of four replicates. Before performing parametric statistical analyses, normal distribution and variance homogeneity of the data were checked by Shapiro–Wilk test and Levene’s tests, respectively (p-value > 0.05). All variables were subjected to two-way ANOVA, considering soil type (S1 and S2) and N supply forms (CTR, CTR + N, CSS) as factors. Significant statistical differences among treatments were assessed by Tukey test (p < 0.05). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA, 1996).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Properties of Citrus Sewage Sludge

The main chemical properties of CSS used for this experiment are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Main chemical parameters determined on citrus sewage sludge (CSS) according to Directive 86/278/EEC [33]. n.d., not detectable.

Citrus sewage sludge exhibited almost neutral pH (6.7) and moderate electrical conductivity (2.19 dS m−1), indicating a good degree of stabilization. The relatively high N content (52 g kg−1) and low C/N ratio (~3) suggest an easily mineralizable organic fraction, likely due to the protein-rich nature of citrus residues and to microbial biomass accumulation during aerobic digestion [16,34]. Phosphorus (4 mg g−1) represented the dominant primary macronutrient after N, whereas Ca, Mg, and K occurred at lower concentrations, consistent with the typical nutrient pattern of fruit-processing sludges [14,35]. Compared with municipal sewage sludge, CSS contained similar N but higher P and lower K levels [36]. When compared with livestock manure, CSS were richer in N and P but less saline than poultry litter, suggesting favorable agronomic properties [34,35]. Heavy metals were all below the Directive 86/278/EEC thresholds, confirming the environmental safety of this material for agricultural use [37]. Such composition suggests that, when applied to soil, CSS may act as a readily available nutrient source for plants, especially N.

3.2. Effect of N Supply Forms on N Dynamics in Soils

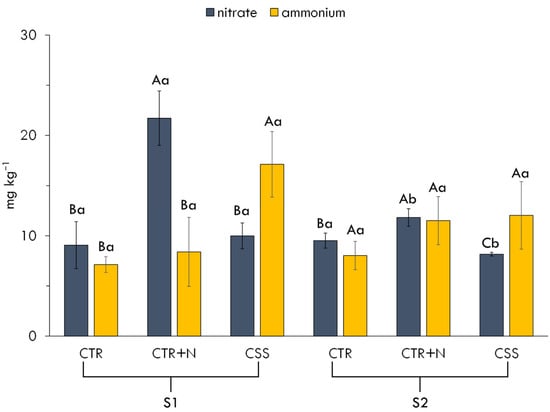

Soil nitrate and ammonium contents were influenced by the type of N supply (NH4NO3 and CSS) and by soil properties regulating microbial activity, including organic C availability, C/N ratio, and carbonate-related buffering capacity. In S1, the application of NH4NO3 resulted in a pronounced increase in NO3− concentrations compared to other treatments in the S1 (Figure 2). This effect can be attributed to the direct input of NO3− from the fertilizer. The higher value obtained in this treatment compared to S2 likely reflects more favorable conditions for microbial activity in S1, including alkaline pH and greater availability of organic C to sustain nitrifier metabolism. Indeed, alkaline pH values are known to promote the growth and activity of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, accelerating NH4+ oxidation to NO3− [38].

Figure 2.

Nitrate and ammonium content in tested soil. Experimental factors were as follows: soil type (S1, S2), fertilizer type (CTR, no fertilizer; CTR + N, ammonium nitrate; CSS, citrus sewage sludge), and their interaction. Different capital letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments within the same soil; lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among soils within the same treatment.

The application of CSS in S1 led to higher NH4+ concentration compared to the other treatments. This outcome suggests that the organic nature of CSS influenced the nitrification process probably by modulating microbial community dynamics. In particular, the presence of complex organic compounds in CSS likely delayed the release of inorganic N, like NH4+ and NO3−, while simultaneously stimulating microbial activity as microorganisms accessed labile carbon substrates. Organic amendments can alter the abundance and activity of nitrifying microorganisms, occasionally suppressing ammonia-oxidizing bacteria due to competition for substrates or the presence of inhibitory compounds [39]. A contrasting pattern emerged in S2. The moderate increases in both NH4+ and NO3− following the addition of NH4NO3 suggest that nitrification was less efficient, mainly because the soil provided limited organic C to sustain microbial activity [40]. Although pH conditions in S2 are still suitable for nitrification, the much lower availability of oxidizable organic C and its narrower C/N ratio greatly reduced the energy supply required for both mineralization and nitrification [20]. This interpretation is consistent with the behavior of the CSS treatment in S2, where only a modest accumulation of NH4+ and low NO3− levels were detected (Figure 2), indicating strong constraints on microbial processes driven by carbon limitation. Taken together, these responses demonstrate that the differences in soil organic matter quantity and quality, rather than pH or carbonate buffering, played a central role in regulating N transformations following fertilization [41]. Soil analyses showed that S1 contained approximately 40% more organic matter than S2 and had a more favorable C/N ratio (12 vs. 9), providing a larger pool of degradable C to support microbial metabolism. This likely enhanced both ammonification and subsequent nitrification in S1. In contrast, the limited amount of readily mineralizable C in S2 reduced microbial energy inputs, constraining N mineralization and oxidation even under pH conditions typically suitable for nitrification.

Comparable behavior has been reported for other organic amendments under favorable soil conditions. Geisseler [20] showed that a substantial fraction of total N in organic fertilizers can become mineral N over time, with modeled mineralization values ranging from 61 to 73% after 100 days for several materials and around 32–40% for poultry manure and manure compost. Similarly, Antille et al. [42] found that a biosolid-derived organomineral fertilizer released 40–72% of its total N within the first 30 days of soil incubation, with an additional 10–28% released over the following 60–90 days. Taken together, these findings support our observation that conditions combining adequate pH and sufficient organic C availability allow organic N sources such as CSS to supply mineral N efficiently.

In addition, they show that the nature of the N source, whether mineral or organic, interacts substantially with soil conditions. Rapid nitrification following NH4NO3 application in alkaline soils enhances the immediate availability of NO3− concentration compared to CSS, reflecting an oversupply of NO3− that has exceeded plant demand. Moreover, this behavior may also increase the risk of NO3− leaching, as highlighted by Volpi et al. [43]. Conversely, the gradual mineralization of organic N sources, such as CSS, can provide a more controlled release of plant-available N that appears to be more closely synchronized with plant uptake, although this effect is heavily dependent on soil microbial activity and environmental conditions.

The application of CSS significantly enhanced β-glucosidase activity, particularly in S1, where values were approximately 18% higher than in the control (Figure 3). β-glucosidase is a key enzyme involved in cellulose degradation catalyzing the release of glucose units, and its activity is often used as an indicator of microbial functional diversity and soil organic matter turnover [44,45]. The observed increase in β-glucosidase activity following CSS addition can be attributed to the high concentration of labile organic carbon supplied by CSS. This fraction provided an easily available energy source for soil microorganisms, thereby stimulating microbial growth and enzyme synthesis [17,46]. The stronger enzymatic response observed in S1 is consistent with its higher soil organic C content and more favorable C/N ratio, which together supported greater microbial functional capacity than in S2. Carbonate-related pH buffering in S1 may have contributed to enzyme stability, but likely played a secondary role compared with the greater availability of degradable organic carbon. Consequently, β-glucosidase activity persisted at higher levels in S1, whereas in S2, lower microbial activity and restricted C availability likely constrained enzyme production. Although microbial community composition was not directly assessed, the enzymatic response indicates a more active and functionally diverse microbial population in S1 following CSS application.

Figure 3.

β-glucosidase activity in soils at the end of the crop cycle. Tested experimental factors were as follows: soil type (S1, S2), fertilizer type (CTR, no fertilizer; CTR + N, ammonium nitrate; CSS, citrus sewage sludge), and their interaction. Different capital letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatment within the same soil; lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among soils within the same treatment.

3.3. Effect of N Supply Forms on Plants

Plant growth and N use efficiency were strongly influenced by the type of fertilizer applied and soil characteristics. In terms of biomass accumulation, total dry weight of wheat plants was only significantly affected by N supply forms in S2 (Figure 4). In this soil, the control exhibited the lowest dry weight, while CSS and CTR + N treatments significantly increased biomass with no differences between the two treatments in S1. Such results highlighted the ability of CSS to match the performance of inorganic N. Comparable plant responses have been reported in other studies using organic amendments. Lucia et al. [16] observed a 33% increase in lettuce dry biomass and a 22% increase in chlorophyll index (SPAD) in soil amended with citrus sewage sludge at 10 t ha−1 compared to the control, supporting the potential of CSS to supply readily available nutrients and enhance crop growth under favorable soil conditions.

Figure 4.

Total dry weight of wheat plant. Tested experimental factors were as follows: soil type (S1, S2), fertilizer type (CTR, no fertilizer; CTR + N, ammonium nitrate; CSS, citrus sewage sludge), and their interaction. Different capital letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatment within the same soil; lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among soils within the same treatment.

In contrast, in S1, all treatments resulted in statistically similar dry biomass, suggesting that the higher nutrient retention capacity and inherent fertility of this soil may have covered the differences in N input.

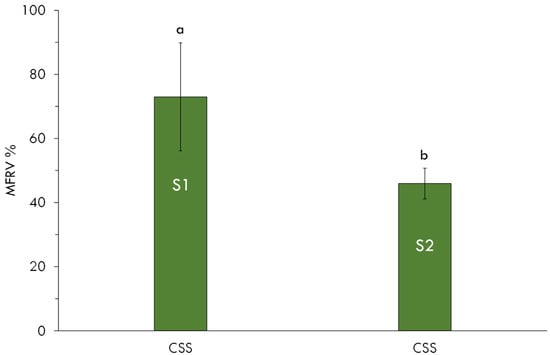

The mineral fertilizer replacement value (MFRV) of CSS in S1 was 73%, significantly higher than the 46% observed in S2 (Figure 5). This indicates that CSS supplied a substantial portion of the N required by the crop in S1. The lower MFRV in S2 may be attributed to reduced nitrification, largely driven by the lower availability of oxidizable organic carbon and the narrower C/N ratio in this soil. These conditions limited microbial energy supply and constrained both ammonification and nitrification, resulting in reduced N uptake by wheat.

Figure 5.

Mineral fertilizer replacement values (MFRV) of CSS applied to different soil (S1, S2) with wheat crop. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among soils within the same treatment.

The findings support the potential of CSS as a sustainable N source for wheat crops, capable of partially replacing synthetic fertilizers. Antille et al. [42] reported that biosolid applications can sustain crop yields comparable to mineral fertilization, although their effectiveness is strongly controlled by soil organic carbon availability and microbial activity. On the one hand, CSS can provide a cost-effective and environmentally friendly alternative to mineral fertilizers. On the other hand, in soils characterized by low organic C availability or limited microbial activity, complementary strategies, such as combining CSS with mineral N or improving soil structure to sustain high nitrification level, may be required to enhance its effectiveness.

4. Conclusions

The results showed that N dynamics were more efficient in S1, where soil organic matter quality provided more favorable conditions for microbial activity and nitrification. Under these conditions, CSS effectively supported wheat growth, achieving an MFRV of 73%, and stimulated β-glucosidase activity, indicating enhanced microbial functioning. In contrast, CSS efficiency was lower in S2, where limited carbon resources constrained microbial processes, reducing N mineralization and uptake. Overall, CSS represents a promising organic N source when applications are adapted to soil characteristics. The CSS used in this study contained heavy metals well below the limits set by Directive 86/278/EEC, indicating no short-term accumulation risk; nevertheless, long-term soil and plant monitoring would be useful to assess potential accumulation over time.

These conclusions refer to the chemical and biological behavior of nitrogen under contrasting soil organic matter conditions. Further studies integrating microbial activity and community composition would help clarify the mechanisms underlying N transformations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture16010037/s1, Table S1. Dry biomass and nitrogen content of each plant fraction, determined at the end of the growth cycle. Experimental factors were: soil type (S1, S2), fertilizer type (CTR, no fertilizer; CTR+N, ammonium nitrate; CSS, citrus sewage sludge), and their interaction. Different capital letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments within the same soil; lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among soils within the same treatment. DW = dry weight; DWR = dry weight of roots; DWS = dry weight of stems; DWGl = dry weight of gluma; DWGr = dry weight of grain; N = nitrogen content; NR = N in roots; NS = N in stems; NGl = N in gluma; NGr = N in grain; NTOT = total plant N; R = root; S = stem; Gl = gluma; Gr = grain. Figure S1. Number of grains in wheat plants. Experimental factors were: soil type (S1, S2), fertilizer type (CTR, no fertilizer; CTR+N, ammonium nitrate; CSS, citrus sewage sludge), and their interaction. Different capital letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments within the same soil; lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among soils within the same treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D. and V.A.L.; methodology, A.D. and V.A.L.; validation, A.D. and V.A.L.; formal analysis, C.L. and S.M.M.; investigation, C.L. and S.M.M.; data curation, C.L., S.M.M. and J.N.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L. and S.M.M.; writing—review and editing, C.L., S.M.M., J.N.C., A.D. and V.A.L.; supervision, A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fukase, E.; Martin, W. Economic Growth, Convergence, and World Food Demand and Supply. World Dev. 2020, 132, 104954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penuelas, J.; Coello, F.; Sardans, J. A better use of fertilizers is needed for global food security and environmental sustainability. Agric. Food Secur. 2023, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, K.; Jonak, K.; Wolińska, A. The Impact of Reduced N Fertilization Rates According to the “Farm to Fork” Strategy on the Environment and Human Health. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelle, T.; Dumas, P.; Souty, F.; Nadaud, F.; Bamière, L. Evaluating the Impact of Rising Fertilizer Prices on Crop Yields. Agric. Econ. 2015, 46, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniatala, B.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Sobotka, D.; Makinia, J.; Othman, M.H.D. Macro-Nutrients Recovery from Liquid Waste as a Sustainable Resource for Production of Recovered Mineral Fertilizer. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudicina, V.A.; Barbera, V.; Gristina, L.; Badalucco, L. Management Practices to Preserve Soil Organic Matter in Semiarid Mediterranean Environment. In Soil Organic Matter: Ecology, Environmental Impact and Management; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S.; Pan, W.; Yang, Y.; Luo, Z.; Wanek, W.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Marsden, K.A.; Liang, G.; Chadwick, D.R.; Gregory, A.S.; et al. Soil carbon sequestration enhanced by long-term nitrogen and phosphorus fertilization. Nat. Geosci. 2025, 18, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahalvi, H.N.; Rafiya, L.; Rashid, S.; Nisar, B.; Kamili, A.N. Chemical Fertilizers and Their Impact on Soil Health. In Microbiota and Biofertilizers; Dar, G.H., Bhat, R.A., Mehmood, M.A., Hakeem, K.R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzolo, E.; Laudicina, V.A.; Roccuzzo, G.; Allegra, M.; Torrisi, B.; Micalizzi, A.; Badalucco, L. Bioindicators and Nutrient Availability through Whole Soil Profile under Orange Groves after Long-Term Different Organic Fertilizations. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Citrus Fruit Fresh and Processed Statistical Bulletin; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/4760a5b5-f3b2-41c7-8713-ccdb1a5f8c08/content (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Rovetto, E.; La Spada, F.; Aloi, F.; Riolo, M.; Pane, A.; Garbelotto, M.; Cacciola, S.O. Green Solutions and New Technologies for Sustainable Management of Fungus and Oomycete Diseases in the Citrus Fruit Supply Chain. J. Plant Pathol. 2024, 106, 411–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zema, D.A.; Calabrò, P.S.; Folino, A.; Tamburino, V.; Zappia, G.; Zimbone, S.M. Wastewater Management in Citrus Processing Industries: An Overview of Advantages and Limits. Water 2019, 11, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, C.; Badalucco, L.; Corsino, S.F.; Galati, A.; Iovino, M.; Muscarella, S.M.; Paliaga, S.; Torregrossa, M.; Laudicina, V.A. Management and Valorisation of Sewage Sludge to Foster the Circular Economy in the Agricultural Sector. Discov. Soil 2025, 2, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, C.; Laudicina, V.A.; Badalucco, L.; Galati, A.; Palazzolo, E.; Torregrossa, M.; Viviani, G.; Corsino, S.F. Challenges and Opportunities for Citrus Wastewater Management and Valorisation: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 321, 115924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, C.; Pampinella, D.; Palazzolo, E.; Badalucco, L.; Laudicina, V.A. From Waste to Resources: Sewage Sludges from the Citrus Processing Industry to Improve Soil Fertility and Performance of Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Agriculture 2023, 13, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almási, C.; Orosz, V.; Tóth, T.; Mansour, M.M.; Demeter, I.; Henzsel, I.; Bogdányi, Z.; Szegi, T.A.; Makádi, M. Effects of Sewage Sludge Compost on Carbon, Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Sulfur Ratios and Soil Enzyme Activities in a Long-Term Experiment. Agronomy 2025, 15, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, J. The Central Role of Soil Organic Matter in Soil Fertility and Carbon Storage. Soil Syst. 2022, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliaga, S.; Muscarella, S.M.; Lucia, C.; Pampinella, D.; Palazzolo, E.; Badalucco, L.; Badagliacca, G.; Laudicina, V.A. Long-Term Organic Management: Mitigating Land Use Intensity Drawbacks and Enhancing Soil Microbial Redundancy. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2024, 187, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisseler, D.; Smith, R.; Cahn, M.; Muramoto, J. Nitrogen mineralization from organic fertilizers and composts: Literature survey and model fitting. J. Environ. Qual. 2021, 50, 1325–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soil Survey Staff. Keys to Soil Taxonomy, 13th ed.; USDA–Natural Resources Conservation Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 3, Chemical Methods; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Soil Science Society of America Book Series No 5; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 961–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Ferree, M.A.; Shannon, R.D. Evaluation of a second derivative UV/visible spectroscopy technique for nitrate and total nitrogen analysis of wastewater samples. Water Res. 2001, 35, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvaney, R.L. Nitrogen—Inorganic Forms. In Methods of Soil Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 1123–1184. ISBN 978-0-89118-866-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, J.M. Nitrogen Total. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 3 Chemical Methods; Sparks, D.L., Page, A.L., Helmke, P.A., Loeppert, R.H., Soltanpour, P.N., Tabatabai, M.A., Johnston, C.T., Sumner, M.E., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA; American Society of Agronomy, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 1085–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S.R.; Sommers, L.E. Phosphorus. In Methods of Soil Analysis Part 2 Chemical and Microbiological Properties; Page, A.L., Ed.; American Society of Agronomy, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA; Soil Science Society of America, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; pp. 403–430. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.; Riley, J.P. A Modified Single Solution Method for the Determination of Phosphate in Natural Waters. Anal. Chim. Acta 1962, 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.J., Jr.; Case, V.W. Sampling, Handling, and Analyzing Plant Tissue Samples. In Soil Testing and Plant Analysis, 3rd ed.; Westerman, R.L., Ed.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1990; pp. 389–427. [Google Scholar]

- Hoagland, D.R.; Dennis, R. The Water-Culture Method for Growing Plants without Soil. Calif. Agric. Exp. Stn. Circ. 1938, 347, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Eivazi, F.; Tabatabai, M.A. Glucosidases and Galactosidases in Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1988, 20, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Crude Protein in Cereal Grains and Oil Seeds; AOAC Official Method 992.23; AOAC International: Washington, DC, USA.

- Ayeyemi, T.; Recena, R.; García-López, A.M.; Delgado, A. Circular Economy Approach to Enhance Soil Fertility Based on Recovering Phosphorus from Wastewater. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council Directive 86/278/EEC of 12 June 1986 on the Protection of the Environment, and in Particular of the Soil, When Sewage Sludge Is Used in Agriculture. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:31986L0278 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Arrobas, M.; Meneses, R.; Gusmão, A.G.; da Silva, J.M.; Correia, C.M.; Rodrigues, M.Â. Nitrogen-Rich Sewage Sludge Mineralized Quickly, Improving Lettuce Nutrition and Yield, with Reduced Risk of Heavy Metal Contamination of Soil and Plant Tissues. Agronomy 2024, 14, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Agrawal, M. Potential Benefits and Risks of Land Application of Sewage Sludge. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Phuleria, H.C.; Chandel, M.K. Unlocking the Nutrient Value of Sewage Sludge. Water Environ. J. 2022, 36, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianico, A.; Braguglia, C.M.; Gallipoli, A.; Montecchio, D.; Mininni, G. Land Application of Biosolids in Europe: Possibilities, Constraints and Future Perspectives. Water 2021, 13, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayiti, O.E.; Babalola, O.O. Factors Influencing Soil Nitrification Process and the Effect on Environment and Health. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 821994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.; Long, X.E.; Tang, Y.F.; Wen, J.; Su, S.; Bai, L.; Zeng, X. Effects of Different Fertilizer Application Methods on the Community of Nitrifiers and Denitrifiers in a Paddy Soil. J. Soils Sediments 2018, 18, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, M.S.; Stark, J.M.; Rastetter, E. Controls on Nitrogen Cycling in Terrestrial Ecosystems: A Synthetic Analysis of Literature Data. Ecol. Monogr. 2005, 75, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwath, W.R.; Paul, E.A. Carbon Cycling: The Dynamics and Formation of Organic Matter. In Soil Microbiology, Ecology and Biochemistry, 4th ed.; Paul, E.A., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2015; pp. 339–382. [Google Scholar]

- Antille, D.L.; Sakrabani, R.; Godwin, R.J. Nitrogen release characteristics from biosolids-derived organomineral fertilizers. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2014, 45, 1687–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpi, I.; Laville, P.; Bonari, E.; Di Nasso, N.N.; Bosco, S. Improving the Management of Mineral Fertilizers for Nitrous Oxide Mitigation: The Effect of Nitrogen Fertilizer Type, Urease and Nitrification Inhibitors in two Different Textured Soils. Geoderma 2017, 307, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.L.; Hopkins, D.W.; Haygarth, P.M.; Ostle, N. β-Glucosidase Activity in Pasture Soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2002, 20, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, R.F.; Naves, E.R.; da Mota, R.P. Soil Quality: Enzymatic Activity of Soil β-Glucosidase. Glob. J. Agric. Res. Rev. 2015, 3, 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, I.; Antolín, M.C.; García, C.; Polo, A.; Sánchez-Díaz, M. Effect of Water Deficit on Microbial Characteristics in Soil Amended with Sewage Sludge or Inorganic Fertilizer under Laboratory Conditions. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.