1. Introduction

AHS represents the wisdom crystallized from the co-evolution of humans and nature throughout history, reflecting the deep adaptability and integration between agricultural production systems and the natural environment. As an ecosystem centered around agricultural production, protecting AHS not only enhances ecological quality, creating conditions for human survival and development, but also plays a crucial role in preserving biodiversity, enhancing ecosystem services, ensuring food and ecological security, and promoting the construction of ecological civilization. However, compared to other types of heritage, the vitality and complexity of AHS make its protection and development more challenging [

1]. The advancement of urbanization, loss of rural labor, the impact of the commodity economy, and insufficient traditional cultural inheritance all pose threats to AHS, risking it being destroyed, forgotten, and abandoned. These issues necessitate scientifically planned protection and management strategies [

2].

Under the framework of ecological civilization and rural revitalization strategies, the protection and sustainable utilization of AHS have become critical issues for regional sustainable development. AHS sites typically possess rich natural resources and traditional culture, while their economic development remains relatively lagging. Realizing the value of ecosystem products is a crucial path to resolving the conflict between the protection and development of heritage sites. Ecosystem products value realization (EPVR) refers to the process of rationally developing ecosystem products through the establishment of policies, markets, and technological mechanisms, transforming their ecological value into economic benefits without damaging the ecosystem [

3]. Through EPVR, the ecological resources of heritage sites can be transformed into economic profits, increasing farmers’ incomes and improving the ecological environment, which provides support for rural revitalization.

There remain substantial gaps in the theoretical research related to AHS. This heritage represents a complex and unique system with rich cultural connotations and higher demands for protection and inheritance. Existing research often appears fragmented. In terms of practical approaches, scholars have explored diverse models, However, common issues such as the lack of coordination mechanisms between these approaches and insufficient market integration are prevalent [

4]. In case studies, empirical analyses of typical systems, such as Honghe Hani Rice Terraces System and Qingtian Rice-Fish culture System, have revealed innovative models for developing material products [

5], but they have failed to overcome the limitations of focusing on single elements or regions, especially the insufficient attention to the transformation of cultural service values [

6]. This fragmentation in research perspectives and reliance on case-specific methodologies has hindered the development of a universally applicable theoretical framework. Additionally, the lack of consensus on foundational concepts, such as the definition and classification of EPAHS, has severely restricted the further development of AHS value transformation theories. Therefore, the primary goal of this paper is to address these gaps by systematically constructing a theoretical framework for EPAHS, clarifying its concepts, connotations, and classification, exploring pathways, accounting methods, and evaluation techniques for the EPVR, and providing both theoretical support and practical guidance for the protection, utilization, and sustainable development of AHS.

Although significant progress has been made in the EPVR in general ecosystems and administrative units [

7], studies focusing on AHS—an intricate system with rich cultural connotations and higher protection requirements—remain fragmented and at an exploratory stage. Current research primarily concentrates on value realization pathways, such as tourism development [

8], industry integration [

9], and ecological compensation [

10]. A systematic exploration of the pathways for realizing the value of ecological products under various constraints, alongside the establishment of a diversified income system for local residents, can both enhance economic benefits and foster proactive AHS conservation [

11].

The process of realizing the value of ecological products in heritage sites exhibits significant variations across different development stages [

12]. In the early stages of tourism market cultivation, government-led ecological compensation mechanisms play a crucial role, primarily due to the immaturity of market mechanisms, which necessitates government intervention and support. As market maturity improves, the economic benefits of industrial development become more apparent, reflected in the extension of industrial chains, the enhancement of value-added products, and the expansion of market scale. Zhang and Min [

9] proposed that industrial integration in agricultural cultural heritage sites can be achieved through three primary models: (1) The “agricultural production-centered” model, which enhances the added value of agricultural products by integrating traditional farming with modern technologies, fostering ecological circular agriculture, agricultural product processing, and cultural and creative industries. (2) The “tourism development-centered” model, which leverages the natural landscapes and cultural resources of agricultural cultural heritage to promote rural tourism, agritourism, and farm-based experiences, thereby driving the growth of related service industries. (3) The “external market-centered” model, which utilizes e-commerce platforms and digital marketplaces to expand the reach of heritage-site products, thereby increasing their market value.

In terms of ecological compensation, existing practices primarily include direct cash subsidies, increased purchase prices for agricultural products, and financial support for conservation activities [

13]. For example, in Zhejiang’s Qingtian region, the rice–fish symbiosis system provides cash subsidies to farmers adopting environmentally friendly production methods, while in Yunnan’s Honghe Hani Rice Terraces, higher purchase prices for rice serve as an incentive for eco-friendly farming. Theoretical research in this area has primarily focused on determining compensation standards. Given the public goods nature of agricultural cultural heritage, a fundamental principle of government-led compensation supplemented by market mechanisms should be established [

14]. Moreover, a well-structured benefit distribution mechanism and comprehensive policy support system are essential to maximizing the value of ecological products in heritage sites [

15].

Despite notable advancements in research and practice, existing studies predominantly adopt generalized ecosystem product frameworks, failing to fully account for the unique characteristics of AHS. Specifically, they overlook the principles of value realization in terms of cultural transmission, farmer benefits, and sustainable development. Additionally, there is a lack of foundational theoretical research on defining the concept of EPAHS, establishing classification standards, and developing methods for assessing value transformation effects. This limitation significantly hinders the in-depth development of theories related to the value conversion of AHS. Therefore, this study aims to bridge this research gap by systematically constructing a theoretical framework for EPAHS. It seeks to clarify the fundamental differences between these and general ecosystem products, define their concepts, connotations, and classification framework, and explore pathways for value realization, accounting methodologies, and evaluation approaches for value transformation. Ultimately, this research provides theoretical foundations and practical guidance for the conservation, utilization, and sustainable development of AHS.

2. Method

The study was conducted on 20 March 2025, by searching the journal literature containing “ecosystem product value” in China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). The target source journals were selected from Science Citation Index (SCI), The Engineering Index (EI), Core Journal of China (CJC), Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index (CSSCI) and Chinese Science Citation Database (CSCD), and the search mode was set as “exact search”. Since the term “ecosystem products” was formally introduced in 2010, we set the search period as “2010–2025”. In addition, this article aims to discuss and introduce the policy terminology with Chinese characteristics, so we manually screened out the literature related to the international terminology “ecosystem services” and other irrelevant literature, such as the literature on land governance, product economy, etc., and we finally obtained 631 usable documents.

Based on bibliometrics and knowledge mapping, CiteSpace was comprehensively used to analyze the current status of domestic research on EPVR. All literature data format conversions and bibliometric analyses for this study were performed using CiteSpace.5.6. Firstly, the selected documents in Refworks format were exported from the CNKI database, and the format conversion of the exported document data was carried out by the CNKI data processing module in CiteSpace. The time period was set as 2010–2025, and the cut-off time partition was 1 year. Keyword co-occurrence analysis was performed on the transformed CNKI data. Based on the results of the co-occurrence of keywords in the field of EPVR, and taking into account the characteristics of AHS as well as the requirements of dynamic conservation and sustainable exploitation, we constructed a theoretical framework of EPAHS.

3. Theoretical Analysis of EPAHS

3.1. Social–Economic–Natural Complex Ecosystem of AHS

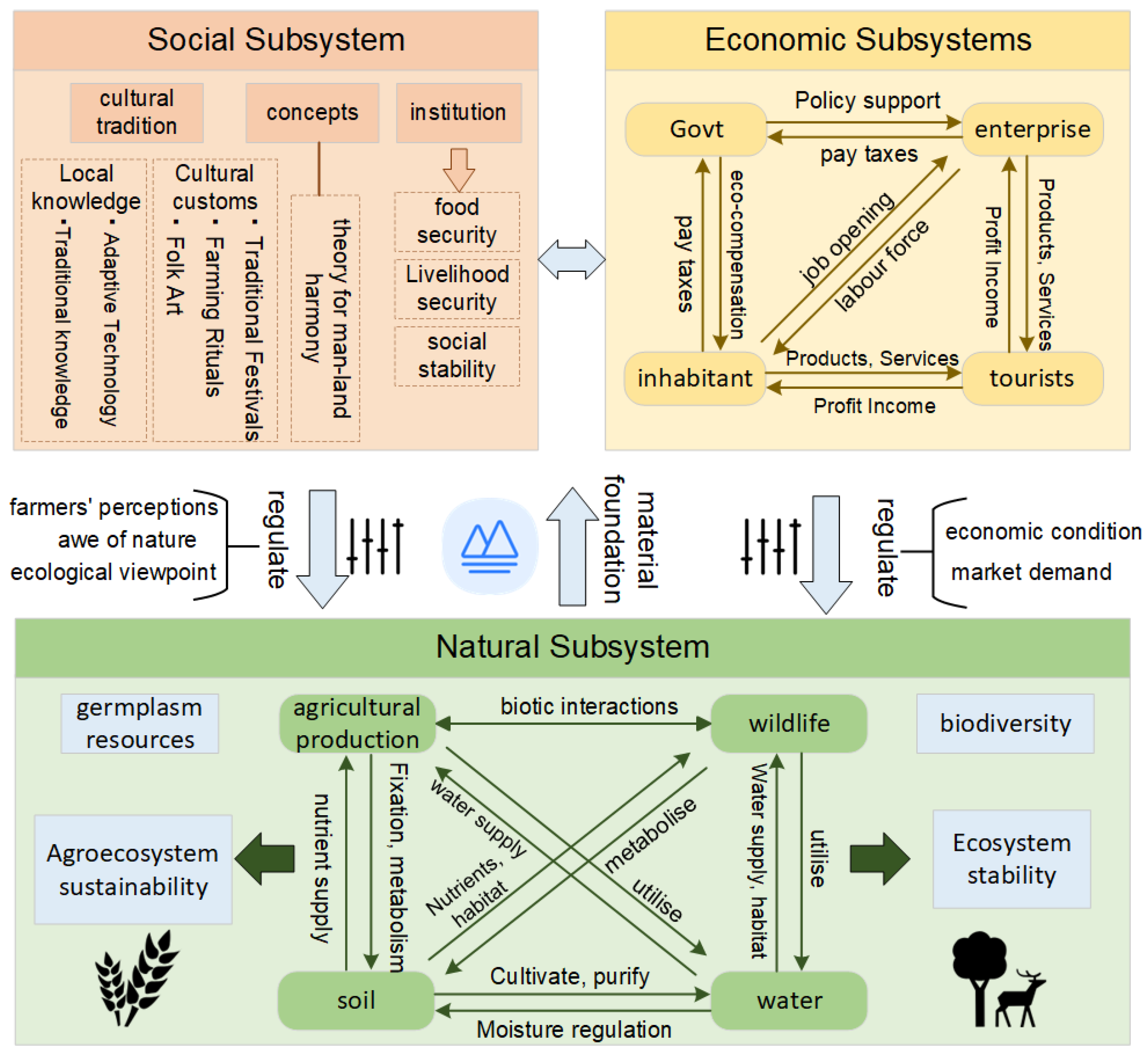

The social–economic–natural complex ecosystem is a highly integrated system formed by the intricate interactions and mutual constraints among social, economic, and natural subsystems. Human economic activities, social structures, and the natural environment are considered as an interconnected whole [

16]. AHS is a typical example of a social–economic–natural complex ecosystem. Its connotation goes beyond the traditional agricultural culture and technology domain, showcasing the relationship between human and nature’s co-evolution. This system consists of three subsystems: society, economy, and nature, which constrain and complement each other, forming a complex network of social, economic, and natural interconnections. The social–economic–natural complex ecosystem of AHS forms the foundation for the creation and development of ecosystem products. A well-organized system can protect the environment while stimulating the activities of businesses, governments, and residents, promoting the operation, trade, and value realization of ecosystem products. Studying this system helps us understand the sources and formation mechanisms of ecosystem products and their roles in the ecosystem, providing theoretical support for related research and applications [

17].

3.1.1. Description of Subsystems

Within the natural subsystem, AHS encompasses multidimensional interactions, including soil, water resources, agricultural production, and wildlife, with biodiversity serving as the core [

18]. Soil, as the foundation of agricultural production, supplies nutrients and moisture, with its structure and composition directly influencing plant growth. Water sources, both surface and groundwater, provide the essential moisture and habitats needed for plant and animal life. Agricultural production converts solar energy into biological energy via photosynthesis. Traditional agricultural practices enhance soil fertility and maintain ecological health. Wildlife, such as pollinating insects and earthworms, sustains biodiversity, fosters nutrient cycling, and strengthens system stability. These interactions form the dynamic balance of ecosystems, enhancing resilience and adaptability, which underpins the sustainability of agriculture.

The social subsystem includes cultural traditions, values, and systems, reflecting human practices in the protection and use of AHS [

19]. Cultural traditions, such as farming rituals, festivals, and the transmission of craftsmanship, enhance community cohesion and serve as a spiritual bond among residents. Traditional production systems, including terraced farming and irrigation, are tailored to local conditions, optimizing ecological niches and balancing resource efficiency with environmental protection, thus shaping an ecological perspective of human–environment harmony. Agricultural products ensure food security, while specialty agriculture stimulates the growth of processing industries, services, and eco-tourism, expanding employment opportunities and providing diversified economic sources, especially for women, thereby maintaining social stability. Traditional knowledge and skills are passed down through families, schools, and communities, ensuring the continued preservation of AHS.

The economic subsystem supports traditional production methods and economic functions, involving multiple stakeholders such as governments, businesses, indigenous populations, and tourists. Specialty agricultural products, such as those with geographic indications, have high market value, and activities in production, processing, and trade significantly bolster indigenous communities and local economies. Governments support heritage conservation among indigenous groups through ecological compensation mechanisms, enhancing their economic conditions, promoting environmentally sustainable production practices, and encouraging sustainable development [

20]. Specialty agricultural landscapes and traditional cultures attract tourists, making eco-tourism a new growth area for local economies. However, its development is grounded in agricultural production and aligned with ecological compensation goals, ensuring a symbiotic relationship between production methods and the ecological environment [

21]. Local enterprises provide employment opportunities and ensure fair distribution of revenues through dividends, while residents and businesses contribute to government taxes, supporting the sustainable development of heritage sites [

22]. The economic subsystem of AHS fosters a balance between ecological protection and economic development through collaborative efforts, establishing a foundation for enduring local economic prosperity.

3.1.2. Interactions Between Subsystems

The ecosystem of AHS interacts with the socio-economic layer through multiple dimensions—resource utilization, cultural integration, economic feedback, resilience enhancement, and policy regulation (

Figure 1). These factors combine to form a dynamic equilibrium system for the AHS. This mutually reinforcing and interdependent relationship is central to its sustainable development and provides critical support for the integration of ecological protection with socio-economic development objectives.

- (1)

Reciprocal Relationship Between Resource Base and Production Activities

The ecosystem provides the material foundation for agricultural production in the socio-economic layer. Soil fertility, stable water supply, biodiversity, and a healthy ecological environment ensure crop growth and agricultural product quality, constituting the core elements of AHS’s economic activities [

23]. In turn, the agricultural production system, using traditional knowledge and techniques, responsibly utilizes natural resources (e.g., terraced rice farming systems and integrated farming systems) to preserve ecosystem health, reduce the risks of over-exploitation, and sustain the long-term viability of natural resource use.

- (2)

Integration of Ecological Services with Socio-Cultural Practices

The rich biodiversity of ecosystems supports both crop production and traditional cultural practices. For instance, farming rituals and festivals based on natural cycles reflect a deep dependence on and respect for the ecosystem. Through cultural transmission and practice, the socio-economic layer embeds ecological protection awareness within community life, promoting the sustainability of ecological services through traditional knowledge systems (e.g., soil nutrient management and water resource distribution).

- (3)

Mutual Support Between Economic Gains and Heritage Conservation

Economic activities, such as the production of specialty agricultural products and eco-tourism, rely on the ecosystem’s aesthetic value and ecological health. These activities not only provide livelihoods for local residents but also support ecological protection efforts. Profits from tourism and geographical indication products [

24] contribute to restoring soil health, preserving biodiversity, and maintaining irrigation systems, thereby enhancing ecosystem functions. This positive feedback loop ensures that economic development and ecological protection reinforce each other.

- (4)

Resilience Enhancement Through Multi-Level Interactions

The interaction between the ecosystem and socio-economic layers boosts the resilience of AHS systems [

25]. When ecosystems face external shocks (e.g., climate change or resource depletion), the socio-economic layer, using cultural wisdom, economic tools, and policy support, facilitates ecological recovery. Additionally, ecosystem stability and diversity strengthen the socio-economic layer’s adaptive capacity in times of crisis, ensuring the continuity of AHS despite social and economic changes.

- (5)

Regulatory Role of Policy and Governance

Policy and governance mechanisms play an essential regulatory role in managing the interactions between the ecosystem and the socio-economic layer. Through measures like ecological compensation, community participation, and benefit-sharing, governments can effectively coordinate ecological protection and economic development [

26]. The sustainable management of ecosystems further promotes social equity and stability, fostering a win-win scenario for both environmental and economic goals.

3.2. The Formation Mechanism of EPAHS

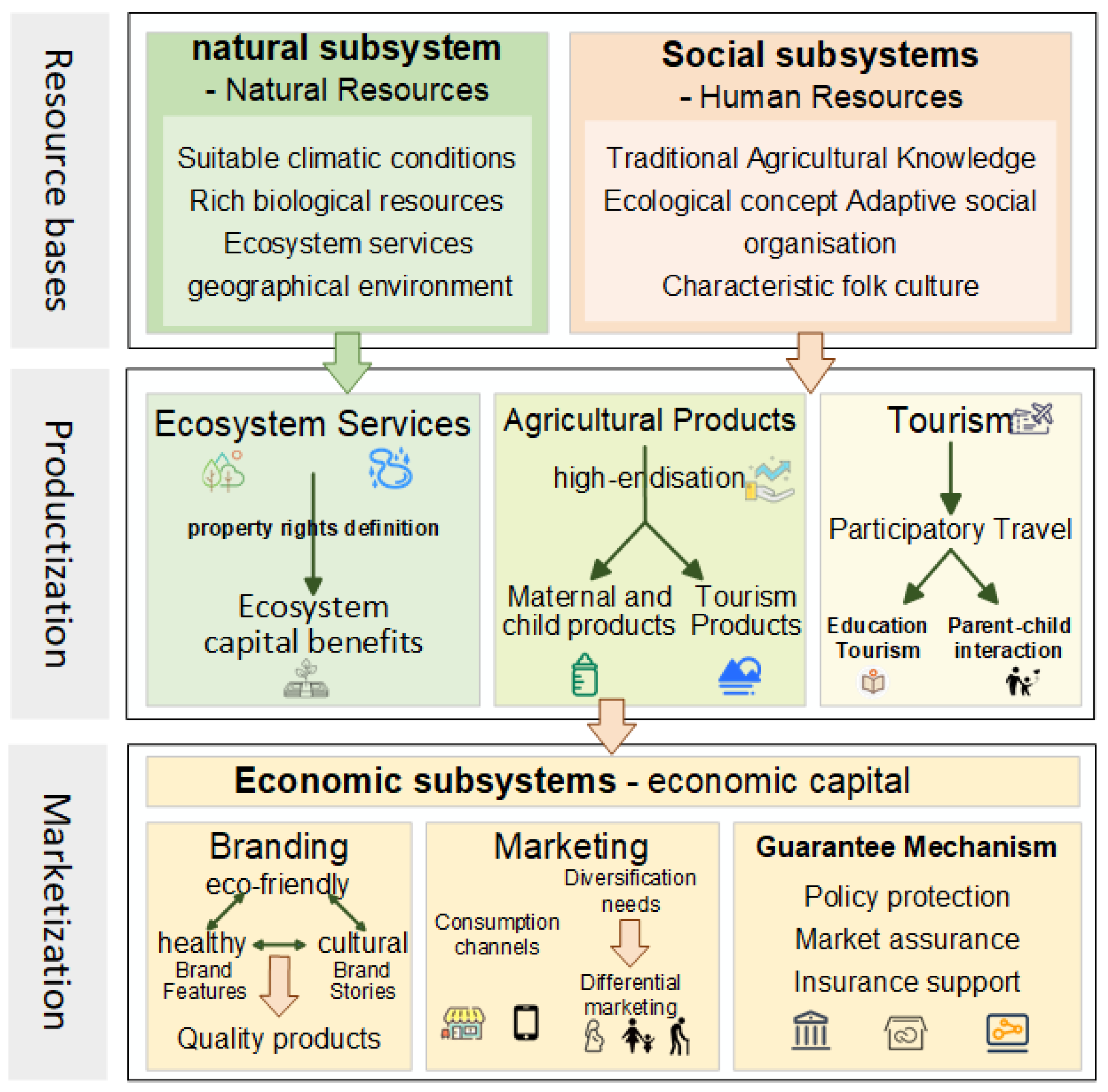

AHS, as a comprehensive entity with ecological, cultural, and economic values, provides a unique resource base and formation mechanism for the development of ecosystem products. The mechanism of ecosystem product formation reveals the deep interaction between the natural ecosystem and the socio-economic system within AHS (

Figure 2).

3.2.1. Resource Basis for the Formation of EPAHS

The formation of EPAHS relies on the synergy between the natural and social subsystems. The natural subsystem provides the material basis: unique geographic environments (such as terraces and wetlands) create differentiated production spaces, diverse climates and biological resources form ecological regulation functions, and high-quality soil and water conditions support the quality of agricultural products. These natural resources, through long-term adaptive use, establish a stable ecological cycle system. For instance, traditional agricultural practices maintain soil fertility, and the staged use of water resources protects the ecosystem. Meanwhile, the social subsystem adds value to these resources through agricultural techniques, folk culture, and social organization, with traditional technologies optimizing resource use efficiency, cultural practices embedding cultural value in resources, and social organizations ensuring resource sustainability. The deep integration of these two subsystems forms a “ecological–cultural” symbiotic model, where resource scarcity, uniqueness, and composite value form the underlying logic of ecosystem product development.

3.2.2. Commercialization of the Resource Basis of EPAHS

The commercialization of the resource basis for EPAHS essentially involves deeply exploring and innovatively transforming unique resources to turn traditional agricultural products into diversified, cross-sectoral products. This transformation process depends on the collaboration of the natural, social, and economic subsystems, highlighting the uniqueness of EPAHS.

The transformation from resources to products follows a “multi-dimensional value-added” path, with the core of commercialization lying in the creative reorganization of resource elements: in the material dimension, green production standards increase the added value of agricultural products, converting ecological advantages into quality advantages; in the cultural dimension, agricultural wisdom and traditional skills are integrated into product design to create cultural premiums; and in the spatial dimension, agricultural landscapes and ecosystem services are combined to develop experiential cultural tourism products. This process requires breaking away from the single-output model of traditional agriculture and constructing a “production-culture-service” composite product system. For example, the Iron Buddha Tea cultural system in Anxi, Fujian, not only produces high-quality tea but also develops ecological tourism [

27]. Through farming experiences, it conveys ecological wisdom and offers tourism services based on landscape aesthetics. The “Sea Silk Tea Source · Tea Tourism Holy Land” route was rated as one of China’s Beautiful Rural Tourism (Autumn) Boutique Routes, and the tea tourism route based on the Iron Buddha AHS was selected as one of the “Top Ten Agricultural Heritage Tourism Routes.” The annual tourism income of Anxi reaches CNY 1.2 billion, demonstrating the immense potential for integrating AHS with tourism and cultural industries.

Moreover, the definition of property rights is of paramount importance. The property rights associated with AHS involve the preservation and transformation of both material culture and ecosystem services. Clear and precise delineation of ownership is essential to safeguard the interests of stakeholders and forms a critical foundation for realizing the value of ecosystem products.

3.2.3. Marketization of EPAHS

Marketization is a crucial stage in realizing the value of EPAHS. Economic resources serve as a bridge, facilitating the industrialization of EPAHS and helping traditional agriculture connect with modern consumer markets. Marketization of EPAHS mainly focuses on branding, marketing, and the establishment of protective mechanisms.

First, branding is fundamental to the marketization of EPAHS [

28]. Through differentiated market positioning, ecological attributes (such as green production), cultural genes (such as historical inheritance), and health values (such as product quality) are organically integrated, creating a unique and competitive brand image. For example, Aohan millet has successfully built a distinctive brand identity through its green production and cultural heritage, strengthening its market recognition. This process not only improves product quality and consumer recognition but also infuses deep cultural meaning into the product through cultural empowerment, increasing its added value. Brand-building strategies help EPAHS stand out in the market, creating competitive barriers.

Secondly, channel innovation breaks through the limitations of traditional sales models, expanding market access. By utilizing online platforms and social media, ecosystem products overcome geographic limitations, reaching broader markets. For example, through e-commerce platforms, local agricultural products can connect directly with consumers nationwide or even globally [

29]. The interaction between online and offline sales enhances market coverage and penetration. Additionally, experiential marketing and the “cultural transmission–consumption conversion–word of mouth diffusion” closed-loop model can effectively enhance consumers’ value perception. At the same time, precise marketing strategies can be employed based on different consumer groups [

30], such as emphasizing the combination of traditional culture and educational tourism for families with children or highlighting the product’s natural and health benefits for older adults, thus increasing market share.

In addition, the development of EPAHS requires a comprehensive protection system, including policy safeguards (such as heritage protection laws and financial subsidy policies), market safeguards (such as guiding market demand and optimizing the industrial chain), and technical safeguards (such as traditional technology improvement and innovation support). Through multi-party cooperation, a development model for EPAHS that aligns with regional development goals can be constructed, achieving the integration of ecological, economic, and cultural benefits.

4. The Theoretical Framework for AHSEP

4.1. Conceptual Definition and Attributes of EPAHS

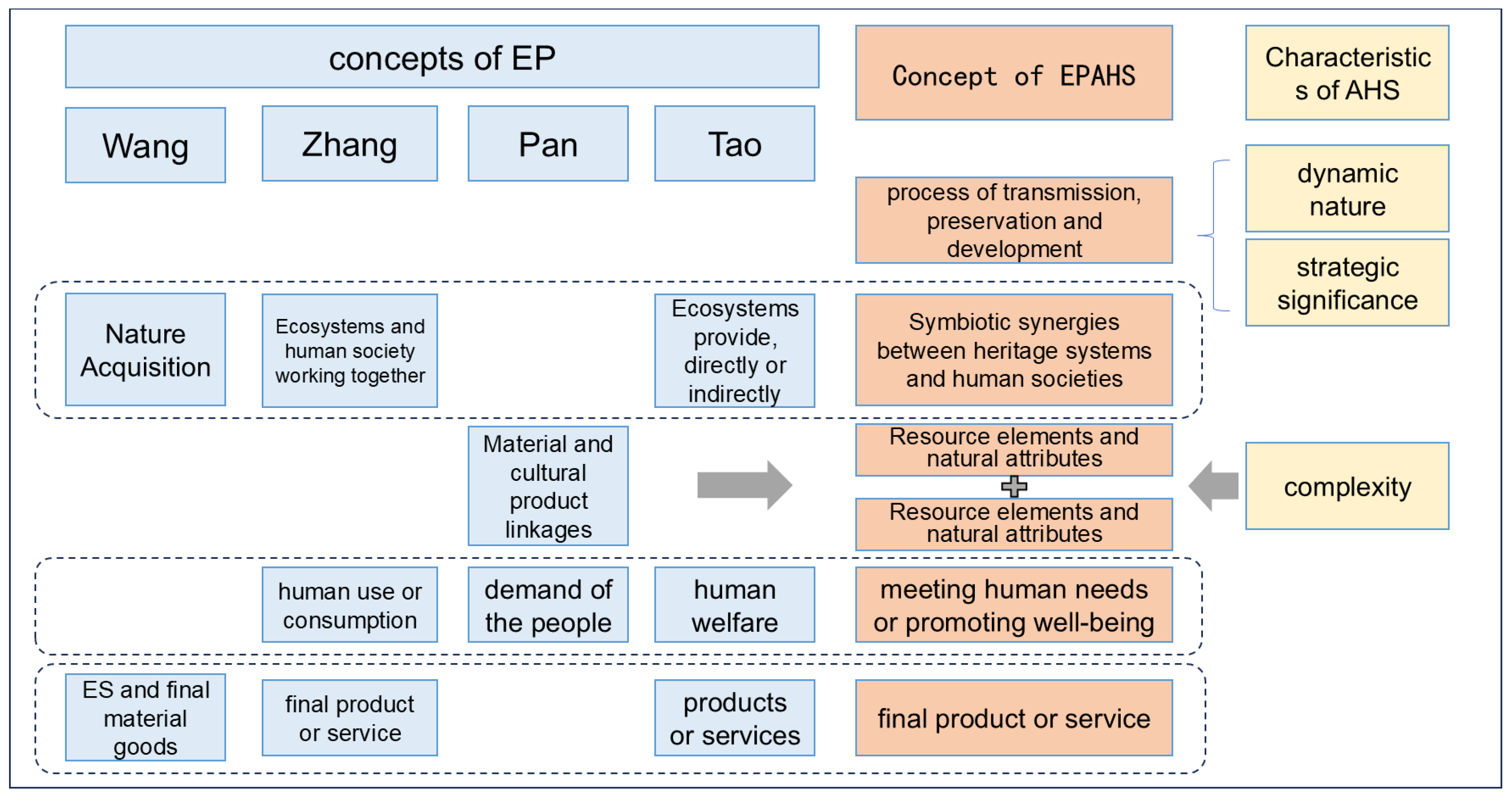

Since its introduction in 2010, the concept of ecosystem products has gradually evolved, with three main interpretations: one is a narrow concept, referring to natural elements such as fresh air and clean water; the second includes the products jointly produced by ecosystems and human societies; and the third is a broad concept that further includes environmentally friendly products produced by the socio-economic system [

31].

The concept of EPAHS must reflect the core characteristics of AHS, integrating the ecosystem product framework with the needs of heritage conservation and development. It should simultaneously embody the ecological sustainability of environmentally friendly practices and highlight the economic, social, and cultural composite attributes that contribute to human well-being. To enhance the practical relevance and applicability of this study, the definition of agricultural cultural heritage ecological products is based on the broad concept of ecosystem products and incorporates definitions proposed by Wang [

32], Zhang [

33], Pan [

34], and Tao [

35], along with the characteristics of agricultural cultural heritage outlined by Min and Sun [

36]. Agricultural cultural heritage ecological products are defined as the final products or services generated in the process of inheriting, protecting, and developing agricultural cultural heritage. These products result from the synergy between heritage systems and human society, utilizing resources and natural attributes in combination with agricultural production and cultural traditions. They meet human consumption and usage needs or enhance human well-being (

Figure 3), including material supply services, cultural services, and regulating services.

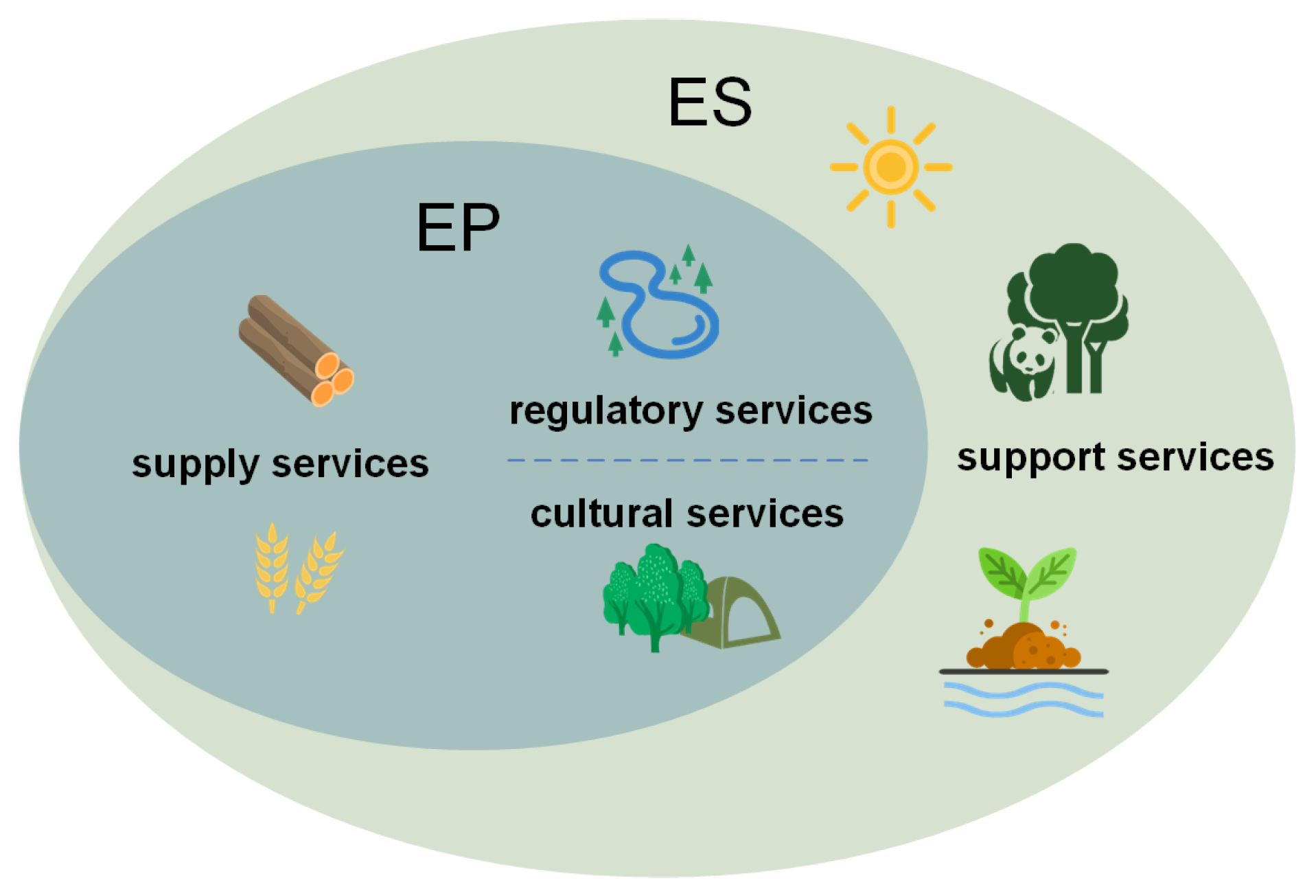

This definition emphasizes three basic features: market transactions, human needs, and final products [

37]. First, EPAHS have tangible or intangible market value, such as agricultural products or cultural tourism services, and are tradable. Second, these products must meet consumer needs, particularly for health, environmental protection, and sustainable development. Through branding and market promotion, EPAHS gradually gain recognition in the market. Finally, the definition of final products avoids the double counting of ecosystem processes and functions, focusing on measurable outcomes produced by the combined actions of ecosystems and human activities, such as food, timber, or clean water. Ecosystem products are conceptually similar to ecosystem services; however, the latter primarily provides indirect benefits, while ecosystem products are directly linked to tangible, perceivable benefits for humans [

38]. EPAHS represent the tangible manifestation and ultimate expression of its ecosystem services. Consequently, EPAHS exclude supporting services, which are non-terminal in nature, and encompass only material, regulating, and cultural services within ecosystem services (

Figure 4).

EPAHS have both commonalities and uniqueness within the ecosystem product system (

Table 1). Like general ecosystem products, EPAHS provide ecological services and possess multiple values, including ecological, economic, social, and cultural aspects, such as food production, biodiversity conservation, and soil and water resource maintenance. Their uniqueness lies in the fact that EPAHS are rooted in traditional agricultural culture. They integrate rich historical and cultural connotations and regional characteristics, building upon general ecosystem products while balancing cultural heritage and ecological protection. Their value is not only reflected in ecological service functions but also extended through the transmission of traditional knowledge and the promotion of cultural diversity protection, which enhances their social significance and economic value. EPAHS emphasize the deep integration of culture and nature, possessing irreplaceable uniqueness and stronger local dependence [

36]. These products play a unique role in the ecosystem product system, enriching the types of ecosystem products and highlighting their distinct historical, cultural, and ecological economic values through the combination of culture and natural resources. The development of such products contributes to the coordinated development of ecological protection and cultural heritage in rural areas, promoting the optimized configuration of ecosystem services.

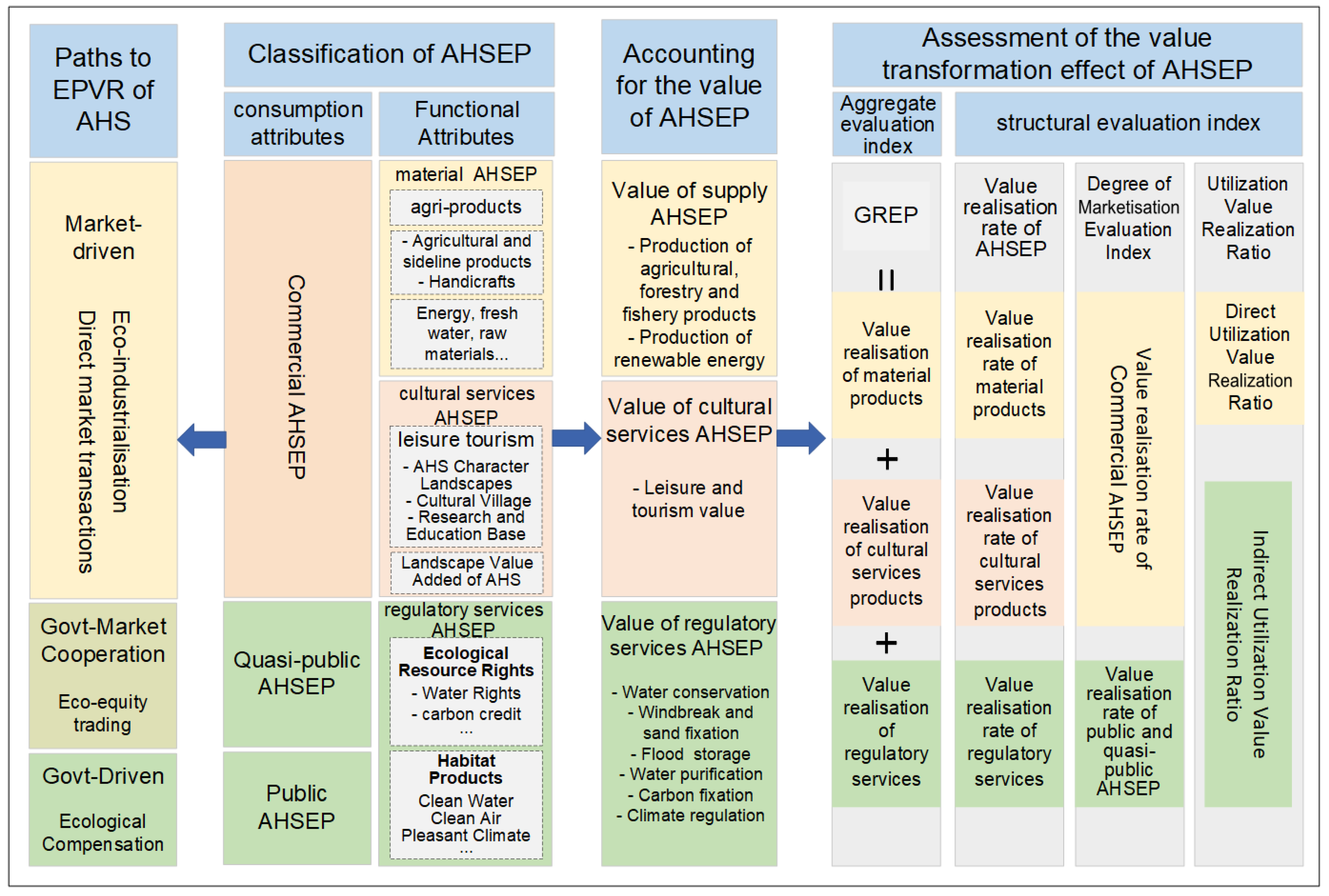

4.2. Classification of EPAHS

The classification of Agricultural Cultural Heritage Ecological Products (EPAHS) provides a scientific foundation and a basic framework for their subsequent applications. Through rational classification, it not only allows for a more systematic and precise identification of the value realization pathways of EPAHS but also provides practical support for value accounting and the assessment of value conversion effects. EPAHS possess multidimensional and multilayered functional characteristics, and a single evaluation system cannot comprehensively reflect their ecological, cultural, and economic values. Therefore, classification is the foundation for an in-depth analysis of their characteristics and serves as an essential prerequisite for future research and practice.

Currently, there are various ways to classify ecosystem products, including by form of existence [

39], degree of human activity [

34], functional attributes [

40], economic characteristics [

41], and consumption attributes [

31]. Based on the specific nature of Agricultural Cultural Heritage, this study classifies EPAHS according to functional and consumption attributes, providing a methodological foundation for constructing a value realization theory that accommodates both the general principles of ecosystem products and the particular constraints of agricultural cultural heritage.

The classification based on functional attributes addresses the cultural complexity of EPAHS, precisely matching the value structure of EPAHS, which is “ecology as the body, culture as the soul.” This classification provides a basis for the diversified value accounting of these products. EPAHS are classified into three main categories: material supply products, cultural service products, and ecological regulation service products. Material supply products primarily include agricultural, forestry, animal husbandry, and fishery products, as well as ecological energy provided by the agricultural cultural heritage system through primary and secondary production processes, such as specialty agricultural products, timber, fuel, and freshwater. Ecological regulation products refer to functions such as water source conservation, biodiversity protection, soil and water conservation, farmland protection, and climate regulation offered by the agricultural cultural heritage system. Cultural service products primarily include leisure and recreation, tourism, and landscape value-added functions associated with the agricultural cultural heritage system.

The further introduction of classification based on consumption attributes addresses the practical need to align with the economic transformation pathways and the specific beneficiaries of EPAHS. Material supply products and cultural service products, due to their clear ownership and minimal externalities, are classified as market-based ecosystem products. These products have clearly defined ownership and relatively low externalities, enabling them to be traded through market mechanisms to directly serve economic transformation needs centered around “agricultural production as the core, and cultural experience as the added value.” Additionally, to ensure better protection and utilization, a further classification is introduced based on the consumption perspective of EPAHS. Public ecosystem products are identified based on the unique characteristics of EPAHS, such as “protection priority,” “environmentally sustainable practices,” and “community benefits.” These products have significant positive externalities (e.g., gene pool protection for globally significant agricultural cultural heritage benefiting all of humanity, and heritage sites with favorable natural environments), but they are difficult to price through market mechanisms and require value conversion through public financial tools, such as ecological compensation and heritage protection funds. Another subset of regulation service products, while possessing externalities, have unclear ownership or usage rights (e.g., carbon emission rights and water rights) and are classified as quasi-public ecosystem products. These products can be moderately commercialized through appropriate institutional arrangements and market mechanisms. This classification system, by distinguishing the exclusivity and competitiveness of products, provides a foundation for developing a differentiated value realization mechanism that involves collaboration between government, market, and community. It helps resolve the “protection vs. development” conflict and ensures that local communities, as primary stakeholders, benefit through appropriate institutional designs.

In essence, the classification system constructs a “genetic map” for value conversion research. The classification of functional attributes defines the observational dimensions for value assessment, while the classification of consumption attributes specifies the institutional pathways for value realization. The matrix combination of these two classifications creates a complete logical chain of “value identification–path matching–effect evaluation” (

Figure 5). This classification-driven evaluation framework ensures that the assessment of value transformation effects encompasses both the economic dimension and a deeper integration of the core objectives of AHS protection.

4.3. Pathways for Realizing the Value of EPAHS

Based on consumption attributes, the value realization pathways for EPAHS can be classified into three categories: government-led pathways, market-led pathways, and government–market cooperation pathways.

4.3.1. Government-Led Value Realization Pathway

The government-led value realization pathway primarily targets public ecosystem products and mainly employs an ecological compensation mechanism. Ecological compensation refers to the economic compensation for farmers who, in ecological functional zones, produce public ecosystem products by bearing certain costs or giving up opportunities. Compensation can be in the form of government compensation or market compensation. Government compensation is provided through fiscal transfer payments, differentiated regional policies, etc. Market compensation involves direct consumer premiums as compensation for ecological protection costs, such as the premium for organic agricultural products and eco-tourism products, which reflect the cost of ecological protection. As noted in the report of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, a diversified market-driven ecological compensation mechanism should be established, emphasizing a voluntary negotiation mechanism between market participants and protected areas, further incentivizing the production of ecosystem products. The ecological compensation mechanisms in regions like the mountainous

Juglans hopeiensis planting system in Beijing have shown early success through direct subsidies and price incentives [

42], encouraging environmentally friendly production methods.

4.3.2. Market-Led Value Realization Pathway

The market-led pathway mainly applies to commercial ecosystem products, relying on the industrialization of ecosystem products and direct market transactions to transform the multi-dimensional value of ecosystem products into economic benefits. Under the premise of not damaging ecosystem functions, this pathway guides the development and utilization of ecological resources through market demand, promoting green, low-carbon, and sustainable economic development.

Ecological industrialization refers to the development and operation of ecological resources without damaging ecosystems, converting “green mountains and clear water” into “golden mountains and silver mountains.” This model enhances overall benefits through industry linkage, such as developing eco-tourism and specialty agriculture. Ecological industrialization meets the requirements of rural revitalization by driving new green dynamics that benefit the public.

Direct market transactions are the most critical means of realizing the value of EPAHS. These include developing specialty agriculture, eco-tourism, and e-commerce platforms. For instance, ecosystem products in the Red River Hani Rice Terraces achieve value realization through market premiums, while utilizing e-commerce platforms to break traditional sales channels and expand product influence [

43].

4.3.3. Government–Market Cooperation Pathway

The government–market cooperation pathway combines government policy support with market resource allocation capabilities through the coordination of legal, administrative, and market mechanisms, promoting the marketization of ecosystem products. This pathway is especially suitable for semi-public ecosystem products, such as biodiversity and water conservation services.

Ecological property rights trading is a key method in this pathway. The government sets ecological resource indicators (such as carbon emission rights or water rights) and uses market mechanisms to trade them, helping AHS sites realize the market value of ecological resources. For example, through carbon emissions trading, AHS sites can obtain carbon sink certification through ecological protection measures and trade these certificates in the market to generate economic benefits. This approach has already been implemented in several areas, such as the Chengdu Rural Property Rights Exchange, which promotes the market circulation of land and forest rights [

44], and the “Two Mountains Bank” reform pilot in Linyi, Shandong, which explores new mechanisms for realizing the value of ecosystem products [

45].

4.4. Accounting for the Value of EPAHS

Ecosystem product value accounting for AHS plays a critical role in its protection and development. By adopting the Gross Ecosystem Product (GEP) accounting framework, the ecological, economic, cultural, and social service values provided by AHS can be scientifically quantified, enabling a comprehensive assessment of its ecosystem products. GEP accounting is a tool used to quantify the total value of natural ecosystems through monetization and quantification, covering provisioning, regulating, and cultural ecosystem services [

46]. It can be applied to calculate the value of AHS’s ecosystem products in terms of material supply, regulating services, and cultural services. This method aligns naturally with the characteristics of AHS, providing a scientific foundation for the comprehensive accounting of its multi-dimensional ecosystem product value. Currently, the GEP accounting method is widely applied and increasingly refined in China. According to incomplete statistics, 44 cities at or above the prefecture level, among the 337 cities in China, have conducted GEP accounting. Additionally, 68 cities have implemented GEP accounting in some of their subordinate districts and counties. Nine provinces (municipalities directly under the central government), including Beijing, Fujian, and Guizhou, have developed provincial-level GEP accounting technical standards [

47].

Material product value accounting for AHS is based primarily on physical quantities, where the output of agricultural, forestry, animal husbandry, and fishery products is measured and assigned market prices. To reflect ecological and cultural values, for unique traditional crops, market premiums for specialized agricultural products or handicrafts may be used to incorporate cultural added value, thus fully capturing the material product value.

The value of regulating services for AHS can be quantified through ecosystem service models. By combining field monitoring and literature data, the quantities of water conservation, soil preservation, and greenhouse gas sequestration can be estimated. These quantities are then translated into value using methods such as the entropy value method [

48], ensuring that the diversity of regulating services is accurately reflected.

Cultural services value accounting for AHS primarily includes leisure tourism value, educational value, and cultural conservation value. Leisure tourism value can be calculated based on tourist numbers and consumption data using market-based methods or tourism expenditure models. Cultural conservation and educational values can be quantified using the replacement cost method (e.g., training costs for traditional farming techniques) or contingent valuation [

49].

However, the price of AHS does not equate to its value. Price is a dynamic monetary expression of a good in the market during exchange, reflecting supply and demand. Processing labor and technological innovations, such as special packaging, brand promotion, and marketing, can increase the added value of EPAHS, which may be sold at a price above their production cost. While these labor inputs reflect in the price, they do not necessarily indicate value. Supply and demand relationships also affect price. Some products, due to their rarity or cultural uniqueness, may have a market price higher than their intrinsic value, with demand surpassing supply. Moreover, externalities make it challenging to quantify the ecological and socio-cultural value of EPAHS, which may not be fully reflected in market prices. These externalities typically result in prices lower than the actual societal cost. Therefore, understanding and protecting the multi-dimensional values of EPAHS, and making market prices better reflect their true value through policies, market mechanisms, and public awareness, remains a long-term challenge.

4.5. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Value Transformation of EPAHS

Based on the characteristics of AHS and the value transformation process, total value evaluation indicators and structural evaluation indicators are introduced [

50].

4.5.1. Total Value Evaluation Indicators

Total value evaluation indicators assess the overall level of EPVR, including the gross value realization of EPAHS, and the realization values of material products, regulatory services, and cultural services from AHS. The total value realization is the sum of the realization values of these three categories (

Table 2).

4.5.2. Structural Evaluation Indicators

Structural evaluation indicators encompass the realization rate of ecosystem product value, the realization rates of structural values for ecosystem products, namely material supply, regulating services, and cultural services, the marketization degree evaluation index for EPVR, the direct or indirect utilization value realization ratios, and the product concentration degree for EPAHS.

The EPVR rate of AHS is identified as a core indicator. It is defined as the ratio of the realized value of EPAHS to the GEP. This metric not only serves as a critical parameter for assessing the effectiveness of the EPVR mechanism but also acts as a key basis for evaluating the success of AHS protection and utilization.

Further disaggregation of this indicator reveals that the structural value realization rate of EPAHS consists of three sub-indicators: the material product value realization rate, the regulation service value realization rate, and the cultural service value realization rate. Each of these measures represents the ratio of the realized value of specific ecosystem products to their corresponding potential ecosystem product values. These indicators provide a clear representation of the efficiency of the structural transformation of ecosystem product values, with a positive correlation between their values and the degree of transformation. Consequently, they offer a quantitative basis for optimizing the pathways through which ecosystem product value is realized.

Within the marketization evaluation dimension, the EPVR system primarily includes two key indicators: the ratio of realized value for commercial ecosystem products, and the ratio of realized value for public or quasi-public ecosystem products. This classification not only enhances the understanding of the varying roles different ecosystem products play within market mechanisms but also helps to identify the potential developmental space for each product type. Moreover, from the perspective of use value, EPVR is further divided into the direct use value realization rate and the indirect use value realization rate. Here, material product value primarily reflects the direct use value of ecosystem products, while the regulation and cultural service values constitute the indirect use value system of ecosystem products. This multi-dimensional evaluation framework offers a systematic structure for comprehensively assessing the effectiveness of EPVR.

5. Conclusions

EPAHS are an essential outcome in the protection and development of AHS, possessing ecological, economic, and cultural values. This paper systematically proposes a theoretical framework for EPAHS by studying the characteristics of their social–economic–natural complex ecosystem. The findings indicate the following:

Firstly, agricultural heritage system ecosystem products, like other ecosystem products, are based on ecosystem services. However, their uniqueness is reflected in their profound cultural attributes and regional distinctiveness, the adoption of environmentally friendly ecological models, an agricultural production-centric focus, emphasis on local community benefits, and dual goals of heritage preservation and ecological maintenance.

Secondly, based on the “functional attributes-consumption attributes” dual classification system, agricultural heritage system ecosystem products can be divided into three categories: material supply products, cultural service products, and regulatory service products. These are further classified into commercial, public, and quasi-public products based on exclusivity and competitiveness characteristics. The study proposes three value realization approaches: market-driven, government-driven, and market–government cooperation, emphasizing that the value realization of agricultural heritage system ecosystem products should be based on agricultural production as the foundation for value transformation, community participation as the intrinsic motivation, and cultural inheritance as the value-added vehicle, following the “protection first, moderate development” principle.

Thirdly, in light of the typical characteristics of agricultural heritage systems—“vitality, complexity, and strategic importance”—and the nonlinear nature of their value transformation process, the study constructs a two-dimensional evaluation indicator system based on the ecosystem gross primary productivity (GEP) theory. This system includes both overall value assessment indicators and structural evaluation indicators to quantify the compound value of agricultural heritage system ecosystem products and their transformation effects.

The study of EPAHS plays a crucial role in achieving the dual goals of ecological civilization and rural revitalization. Moving forward, further exploration of the value realization mechanisms for ecosystem products is necessary, combining theory and practice to better support the comprehensive protection and utilization of AHS.

6. Discussion

The cognitive misconceptions that exist in the process of AHS preservation can be effectively resolved through the EPVR mechanism. A prevalent misconception is the simplistic opposition between the protection of AHS and modern agricultural development. This view fails to recognize the inherent consistency between the ecological wisdom embedded in traditional agriculture and the principles of modern sustainable development. The ecological cycle models formed over thousands of years of traditional agricultural practice provide valuable insights for addressing the high energy consumption and pollution challenges of modern agriculture. Meanwhile, modern agricultural technologies can support the innovative transformation of traditional wisdom, and the integration of both can give rise to a more dynamic ecological agriculture development model.

The second misconception is the separation of cultural heritage protection from the improvement of farmers’ livelihoods. In reality, by establishing an EPVR system of AHS, it is entirely possible to protect traditional agricultural systems while simultaneously creating diversified economic benefits for local residents, making cultural heritage protection a key driver of rural revitalization.

The third misconception stems from a one-sided understanding of the relationship between protection and development. Protection should not be seen as static conservation; rather, it should involve dynamic management and adaptive innovation. This approach, while maintaining the stability of the ecosystem, allows the full economic and social value of cultural heritage to be realized. The establishment of an EPVR mechanism provides the scientific basis for balancing protection and development, ensuring that AHS sites can sustain their cultural transmission and ecological functions while also gaining reasonable development space. Ultimately, this leads to the synergistic advancement of ecological protection, cultural preservation, and socio-economic development.

This systematic framework of EPAHS not only corrects the cognitive biases surrounding AHS protection but also offers important insights for global agricultural sustainable development.

Despite these contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the evaluation of cultural service values remains challenging due to their intangible nature, which may introduce subjectivity into the assessment. Secondly, the proposed framework is primarily theoretical, based on existing literature, and its generalizability needs to be further tested through large-scale empirical studies. Third, the dynamic and evolving nature of AHS requires continuous adaptation of the evaluation framework, which poses methodological challenges for long-term studies.

To address these limitations and further advance the field, future research could focus on the following avenues: (1) Refinement of Valuation Methods: Develop more robust and objective methods for quantifying cultural service values, potentially integrating interdisciplinary approaches from ecology, economics, and cultural studies. (2) Empirical Validation: Conduct large-scale empirical studies to test the applicability of the proposed classification system and value realization pathways across different AHS contexts. (3) Policy Innovation: Explore innovative policy tools, such as enhanced ecological compensation mechanisms and community-based governance models, to support the sustainable development of EPAHS. (4) Longitudinal Studies: Track the evolution of EPAHS over time to better understand their dynamic nature and adapt management strategies accordingly.

This study makes several significant contributions to the literature: it proposes a comprehensive theoretical framework for EPAHS, systematically distinguishes the unique and general characteristics of agricultural cultural heritage ecological products for the first time, and offers a new research perspective and theoretical framework for studying value realization of these products. It introduces a dual classification system and customized value realization pathways, offering a systematic approach to managing EPAHS. Furthermore, it extends the GEP theory to AHS contexts, presenting a novel evaluation framework that captures the compound value of EPAHS and informs policy development. These contributions not only enrich the theoretical foundation of ecosystem product research but also provide practical insights for achieving the dual objectives of ecological civilization and rural revitalization.