Abstract

Induced resistance in plants is a promising strategy for pest management, helping to reduce dependence on synthetic pesticides. However, no study has yet examined the interaction between Tetranychus urticae and Aronia melanocarpa, including host acceptance, performance, and antioxidant defence mechanisms. In this study, host acceptance of T. urticae was evaluated using two A. melanocarpa ecotypes: a non-cultivar (AMe) and the cultivated variety ‘Galicjanka’ (AGe). Leaf morphological traits (trichome density and length) and key life-history parameters of the mite (fecundity, egg development time, and larval duration) were assessed. Mite feeding effects on oxidative stress markers (hydrogen peroxide—H2O2; thiobarbituric acid reactive substances—TBARS) and antioxidant enzyme activity (guaiacol peroxidase—GPX ascorbate peroxidase—APX) were analysed by ecotype and infestation duration. Results showed low fecundity and prolonged development, indicating that neither ecotype is a preferred host for T. urticae. Ecotype-dependent differences in acceptance and mite performance suggest that variation in trichome density and biochemical traits may influence susceptibility. Baseline differences in H2O2 and TBARS imply a role in constitutive resistance, while their induction, accompanied by increased GPX and APX activity, highlights oxidative stress and antioxidant defences as key components of A. melanocarpa responses to mite attack.

Keywords:

biotic stress; black chokeberry; life table; mites; plant defence; two-spotted spider mite 1. Introduction

Black chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa [Michx.] Elliott) is a deciduous shrub belonging to the Rosaceae family, native to the eastern regions of North America. At present, aronia is cultivated worldwide; however, it has gained the greatest popularity in Eastern, Central, and Northern European countries [1]. Poland is the world’s largest producer of chokeberries, accounting for nearly 90% of global production [2]. Due to its origin, the genus Aronia constitutes a specific and relatively closed group of plants, characterized by low genotypic diversity, as confirmed by the findings of Smolik et al. [3]. Some cultivars have been developed from A. melanocarpa, while others are hybrid cultivars [4,5]. Currently, several commercial chokeberry cultivars are available on the market, with major ones including ‘Nero’, ‘Aron’, and ‘Galicjanka’ [4,6,7,8,9]. Since the early 2000s, systematic surveys of Polish plantations have documented numerous herbivorous species [10,11]. Among them, the two-spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae), is a cosmopolitan and highly polyphagous pest, infesting a wide range of hosts, including vegetables, ornamentals, herbaceous plants, and trees. It has been recorded on over 1000 plant species belonging to more than 140 families, including over 70 from the Rosaceae [12,13]. Because of this broad host range, it is one of the most dangerous herbivorous pests in fruit production [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21].

Severe infestations can lead to defoliation, loss of chlorophyll, leaf bronzing, and even plant death as a result of direct feeding [22,23,24]. The exceptionally high reproductive capacity of this pest allows it to cause severe damage in a very short period. In Poland, 4–6 generations develop during one growing season, and under optimal conditions (25–30 °C), a single generation may complete in 8 days [25]. The length of the life cycle and the development of the population depends on the temperature, the type of host plant on which it develops, and plant health [26,27]. The plant nutrition status, leaf age, and moisture stress also influence development and reproduction of T. urticae [28]. Economic losses are frequently reported in berry crops such as raspberry, strawberry, and currant [29,30,31,32]. Until now, populations of T. urticae observed on black chokeberry plantations have not posed a significant threat. Spider mites have been reported on black chokeberry by Górska-Drabik [11]. According to our observations in nurseries and plantations with disrupted water availability, mite-induced plant damage varies from slight to occasionally severe. However, climate warming, rising temperatures, and low humidity may promote its development and enhance negative effects on plant growth, especially in nurseries and young plantations [33,34].

Plants and herbivores interact in complex ways, and plant responses to feeding can reveal important chemical and ecological mechanisms underlying these interactions [35]. Herbivory activates constitutive or induced plant defence mechanisms [36,37], which may affect pest establishment and performance. Plant resistance can reduce infestation or increase pest emigration [38,39]. One form of resistance is antixenosis (formerly termed non-preference or non-acceptance), where pests avoid a host due to specific morphological or chemical traits [40,41,42,43,44]. Another mechanism, antibiosis, occurs when plant characteristics negatively affect pest development or survival [41,43,44,45,46].

Herbivore feeding often triggers a rapid oxidative burst in plant tissues, leading to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide, superoxide, and hydroxyl radicals [47,48]. These molecules function both as direct defence factors and as key signalling components that activate downstream protective pathways [49,50,51,52,53,54]. Their levels are regulated by antioxidant enzymes, including catalase and peroxidases; among them, ascorbate peroxidase (APX) plays a central role in hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) detoxification, while guaiacol peroxidase (GPX) contributes to ROS scavenging and cell wall strengthening [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. Although these mechanisms are well documented in plant stress physiology, their regulation in response to herbivory—particularly mite feeding—remains insufficiently understood [64].

Inducing plant resistance is a promising strategy for reducing pest populations. Understanding the underlying resistance mechanisms may facilitate the development of cultivars with improved resilience and reduce reliance on chemical control. Although numerous studies have explored the interaction between plants and T. urticae, there is no information on its feeding behaviour on A. melanocarpa, nor is the response of the antioxidant defence system of A. melanocarpa to mite infestation known. To address this gap, both ecotypes were selected for this study, reflecting the presence in Poland of older plantations established in the 1980s from non-cultivar seedlings, as well as the increasing number of more recent plantings of the Polish cultivar ‘Galicjanka’.

This study investigated host acceptance of T. urticae in two A. melanocarpa ecotypes, focusing on leaf traits such as trichome density and length. We also assessed effects on key mite life-history traits, including fecundity and developmental time. Additionally, oxidative stress markers (H2O2, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS)) and antioxidant enzyme activity (GPX, APX) were measured. These results provide one of the first comprehensive insights into resistance and antioxidant responses of A. melanocarpa to mite feeding.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

An experiment was conducted in 2022 under laboratory conditions at the Department of Plant Protection, University of Life Sciences in Lublin, Poland (ULSL). Two ecotypes of black chokeberry were used: non-cultivar—A. melanocarpa (AMe) and cultivar—A. melanocarpa ‘Galicjanka’ (AGe). AMe ecotype analyzed in this study originates from a plantation located in Boduszyn (51°19′29″ N 22°38′17″ E), in southeastern Poland (Lublin Province). The plantation was established in the 1980s using a population derived from seedlings of a non-cultivar. Plants of A. melanocarpa ‘Galicjanka’ (AGe) were obtained from a specialized horticultural centre. Both ecotypes were cultivated in 22 cm diameter plastic pots filled with a universal growing substrate, consisting of 80% peat and 20% perlite. All experimental plants exhibited a uniform growth habit, consisting of two shoots per plant, each measuring 40–45 cm in height. Throughout the experimental period, the plants were maintained under controlled conditions: temperature 25 ± 1 °C, humidity 60 ± 5%, and a photoperiod of 16:8 h (L:D).

2.2. Free Choice Test

Stock cultures of T. urticae were reared on potted bean plants under laboratory conditions at the ULSL. In order to analyse the degree of acceptance of two ecotypes of A. melanocarpa by the two-spotted spider mite, a free—choice test was conducted. Non-infested plants (40–45 cm tall seedlings with 9 leaves) were arranged in a circle on a cardboard platform, so that their leaves did not touch one another. The shoots were secured with office tape to ensure equal access of mites to the leaves. One compound leaf of Phaseolus sp. colonized by 35 adults and nymphs (1:1) T. urticae were placed in the centre of the cardboard platform. In the experiment, a 30 cm diameter platform was used, with plants positioned on opposite sides at a height of approximately 30 cm. The number of individuals moving to the plants of the examined ecotypes was counted after 7 d. Plant acceptance was calculated as the number of mites recorded on each plant, summed for each ecotype, and expressed as a percentage. The experiments were conducted in five replicates, using a total of 175 adults and nymphs. After seven days, the number of mites remaining on the plants was lower than at the start of the experiment—8% of the individuals did not colonize the test plants and dispersed. These mites were therefore excluded from the final analysis, resulting in a total of 161 individuals. All experiments were performed under controlled conditions of 25 ± 1 °C, 60–70% relative humidity, and artificial lighting with a 16:8 h (L:D) photoperiod.

2.3. Mite Rearing and Demographic Measurements

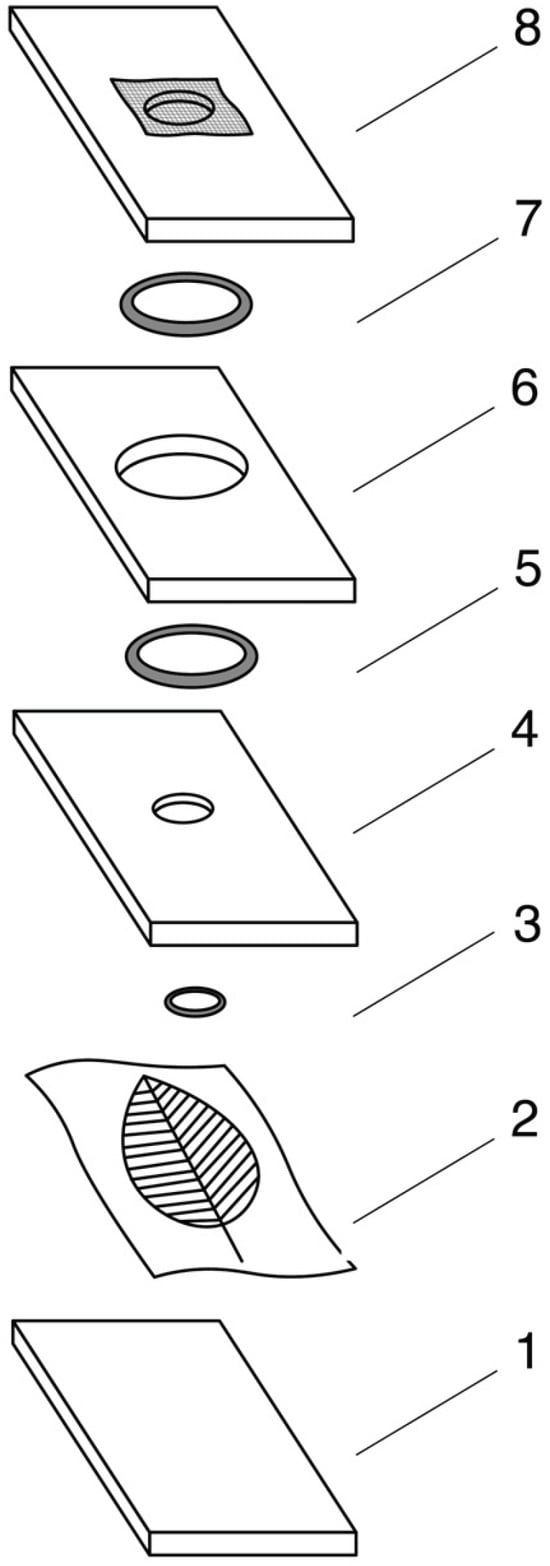

The experiment used a laboratory population of the two-spotted spider mite that had been maintained under controlled conditions for approximately three years (ca. 20 generations). To establish a genetically uniform rearing line, a single adult female T. urticae was isolated from the stock colony and transferred to a Munger cell for oviposition. After egg laying, the female was removed, leaving a single egg. The individual that developed from this egg was subsequently used to initiate a clonal rearing line, with adults paired to maintain the line for experimental purposes. In this study, we refined the method for individually rearing mites on detached leaves by using a Munger cell additionally sealed with rubber gaskets [65] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of the modified Munger cell used in the experiment: 1—Plexiglas bottom plate; 2—leaf placed on a lignin pad; 3—rubber gasket (12 mm diameter); 4—plate with a 12 mm central opening; 5—rubber gasket (30 mm diameter); 6—plate with a 30 mm central opening; 7—rubber gasket (30 mm diameter); 8—top plate with a 12 mm ventilation hole covered with muslin mesh.

Each cell consisted of four 3 mm plexiglas plates arranged in sequence. The bottom plate was lined with tissue paper, and a single leaf was placed on it (ventral side up). The next plate contained a 12 mm central hole and was sealed with a rubber gasket. Above it, a plate with a 30 mm central hole was added to increase the culture space, also sealed on both sides with rubber gaskets. The top plate contained a 12 mm ventilation hole covered with muslin mesh. The stack was held together with large binder clips. The leaves designated for the experiment were approximately four months old. Individual leaves measured 5–6 cm in length and 3–4 cm in width. To maintain humidity in the cell, the tissue paper was moistened daily with distilled water by using a pipette. When watered daily, the leaves remained fresh for approximately 3.5 weeks. Observations were made at 24 h intervals with a Nikon stereoscopic microscope SMZ 800 (Nikon Co., Tokyo, Japan). The experiments were conducted under constant conditions of 25 ± 1 °C, 60–70% RH, and artificial light with a 16:8 (L:D) photoperiod. Daily fecundity, egg development time, and larval development time were measured and are presented as arithmetic means with standard deviations (SD). For each ecotype, the experiment was conducted with 20 replicates (total N = 40).

2.4. Surface Structure of A. melanocarpa Leaf

The number and length of trichomes (on the underside) were determined on the leaves of each ecotype. Using a 1 cm2 template, trichome density was assessed under a Nikon SMZ 800 stereomicroscope and trichome length was measured with NIS-Elements software (version D) (Nikon Imaging Software Elements) (Nikon Co., Tokyo, Japan). Trichome length was expressed in millimetres (mm). Twenty leaves from each ecotype were analyzed (total N = 40).

2.5. Physiological Analysis

Leaf analyses were conducted at the Laboratory of the Department of Plant Physiology, University of Life Sciences in Lublin. Physiological measurements were conducted in three replicates (N = 3) for each parameter, as described below:

Hydrogen peroxide concentration (H2O2) was estimated by forming a titanium–hydro peroxide complex [66]. Subsequently, 0.1 g of plant material was grinded in 3 cm3 of phosphorus buffer (50 mM, pH 6.5) at 4 °C, and then the mixture was centrifuged at 6000× g for 25 min. To determine H2O2 concentration, 1.5 cm3 of the supernatant was added to 0.5 mL TiO2 in 20% (v/v) H2SO4 and centrifuged again at 6000× g for 15 min. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 410 nm against blank reagent with a Cecil CE 9500 spectrophotometer (Cecil Instruments, Cambridge, UK). The H2O2 concentration was calculated using the molar absorbance coefficient, which for H2O2 was 0.28 μM−1 cm−1, and was expressed as nanomoles per 1 g fresh weight (FW).

The content of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) was assessed according to the method by Heath and Packer [67]. A total of 0.2 g crushed plant material was extracted in a 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer pH = 7.0, and then centrifuged at 12,000× g for 20 min. Next, 0.5 cm3 of the homogenate was added to 2 cm3 20% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) containing 0.5% thiobarbituric acid (TBA) and incubated for 30 min in a water bath at 95 °C. Thereafter, the samples were cooled down and centrifuged at 10,000× g for 10 min. Absorbance was measured at 532 and 600 nm using a Cecil CE 9500 spectrophotometer (Cecil Instruments, Cambridge, UK). The concentration of TBARS in a sample was calculated by using the molar absorbance coefficient, which for TBARS is 155 nM−1 cm−1, and it was expressed in nanomoles in 1 g of dry weight (FW).

Antioxidant enzyme assays: For GPX and APX activities, 0.25 g of each sample was homogenized in 0.05 mol dm−3 phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 0.2 mol dm−3 EDTA and 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) at 4 °C. Then, the homogenates were centrifuged for 10 min (10,000× g, 4 °C) and immediately used for analyses. Guaiacol peroxidase (GPX, EC 1.11.1.7) activity was measured by the method of Małolepsza et al. [68]. The reaction mixture contained 0.5 cm3 0.05 mol dm−3 phosphate buffer (pH 5.6), 0.5 cm3 0.02 mol dm−3 guaiacol, 0.5 cm3 0.06 mol dm−3 H2O2 and 0.5 cm3 of enzyme extract. The change in absorbance was measured at 480 nm for 4 min, at 1 min intervals using a Cecil CE 9500 spectrophotometer (Cecil Instruments, Cambridge, UK). GPX activity was determined using the absorbance coefficient for this enzyme, which was 26.6 mM cm−1 and expressed as the change in peroxidase activity per fresh weight (FW) (U mg−1 FW). Ascorbate peroxidase (APX, EC 1.11.1.11) activity was determined using a protocol described by Nakano and Asada [69]. The reaction mixture contained 1.8 cm3 0.1 M phosphorus buffer pH 6.0, 20 mm3 of 5 mM sodium ascorbate, 100 mm3 of 1 mM H2O2 and 100 mm3 of enzymatic extract. Ascorbate oxidation was monitored at 290 nm for 5 min, measured at 1 min intervals with a Cecil CE 9500 spectrophotometer (Cecil Instruments, Cambridge, UK). APX activity was determined using the absorbance coefficient for this enzyme, which was 2800 M−1 cm−1. APX activity was expressed as the change in peroxidase activity per fresh weight (FW) (U mg−1 FW).

2.6. Statistical Procedures

All data are presented as arithmetic means () ± standard deviation (SD). The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Homogeneity of variances was evaluated with Levene’s test. Differences in leaf morphological traits between the AMe and AGe ecotypes, as well as percentage data from the free-choice bioassay (after Bliss transformation), were analyzed using Student’s t-test. The relationships between the variables under study (trichome density and number of mites) were assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). Differences in demographic parameters within ecotypes were confirmed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Physiological data (analyzed separately for each ecotype) were evaluated using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post hoc test (for H2O2 concentration, TBARS content, and GPX and APX activity in AMe and AGe leaves). Differences between ecotypes (analyzed separately for each time point) were verified using Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using TIBCO Statistica for Windows, version 14 (StatSoft Sp. z o.o., Kraków, Poland).

3. Results

3.1. Plants Acceptance by T. urticae and Leaf Morphological Characteristics of A. melanocarpa Ecotypes

The attractiveness of the tested AMe plants to T. urticae in the free-choice test depended on the ecotype (Table 1). The AMe ecotype was preferred, with 66.52% of two-spotted spider mites choosing it for feeding, whereas the AGe ecotype was less attractive (33.48%). These differences were statistically significant.

Table 1.

Acceptance of A. melanocarpa ecotypes by T. urticae and morphological characteristics of plant leaves.

The leaf structures of both ecotypes (trichome number and length) were differed. The leaves of AMe had statistically significantly fewer setae (73 per cm2) than the leaves AGe (108.70 per cm2). However, trichome length did not differ significantly between the two ecotypes, with mean values of 0.96 mm and 1.02 mm, respectively (Table 1).

Ecotype-dependent trends were observed between trichome density and host acceptance, with a strong negative correlation in AME (r = −0.84; p = 0.07) and a strong positive correlation in AGE (r = 0.78; p = 0.12); however, neither was statistically significant.

3.2. Demographic Parameters of T. urticae

The mean daily fecundity of T. urticae females was 2.15 on the AMe ecotype and 2.34 on the AGe ecotype (Table 2). No statistically significant differences in female fecundity were observed between the studied ecotypes.

Table 2.

Mean (±SD) daily fecundity, duration of egg development, and larval stage (in days) of T. urticae reared on two ecotypes of A. melanocarpa.

Egg development time was significantly shorter on the AGe, averaging 3.83 days, compared to 4.79 days on AMe. Larval development duration did not differ significantly between ecotypes and averaged 2.66 days (AGe) and 2.86 days (AMe), respectively.

3.3. Changes in Hydrogen Peroxide and Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances

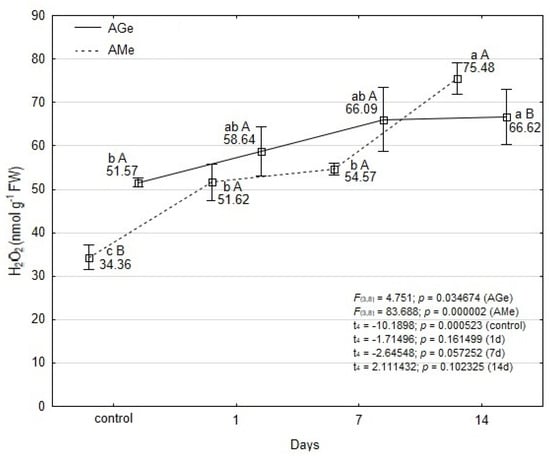

Throughout the experimental time points, the concentration of H2O2 in the leaves of the ‘Galicjanka’ cultivar (AGe) was generally higher than in AMe, with the exception of the final measurement on day 14. However, significance of these differences was statistically confirmed only under control plants and on day 7 of mite feeding (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of T. urticae infestation in hydrogen peroxide concentration within leaves of A. melanocarpa (AMe) and A. melanocarpa ‘Galicjanka’ (AGe). Results are reported as mean ± SD (standard deviation) calculated from three replicates (N = 3). Data points marked with different lowercase letters are significantly different within each ecotype over time (Tukey’s HSD test p ≤ 0.05). Uppercase letters indicate significant differences between the two ecotypes within the same time point (Student t-test, p ≤ 0.05).

During the initial period of mite feeding (up to 7 days), a statistically significant increase in H2O2 concentration was detected only in AMe leaves (1.6-fold relative to the control), whereas the increase observed in AGe was not significant. After 14 days of T. urticae feeding, the H2O2 concentration significantly increased in both ecotypes—by 2-fold in AMe and by 1.3-fold in AGe, relative to their respective controls.

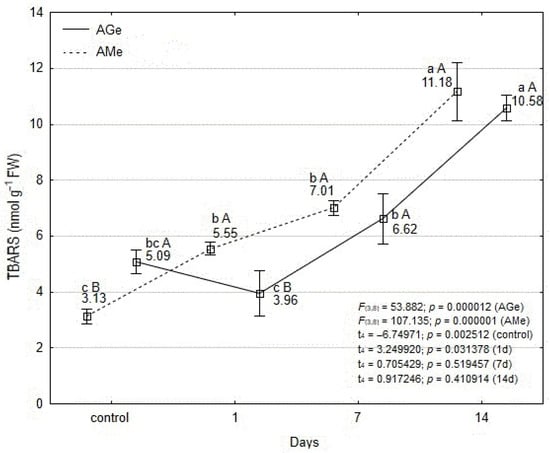

The content of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) in the tissues of AGe was 1.5 times higher than in AMe, but only in the control plants (Figure 3). At subsequent time points—except on the first day of mite infestation—no statistically significant differences in TBARS levels were observed between the two ecotypes.

Figure 3.

Effect of T. urticae infestation in content of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) within leaves of A. melanocarpa (AMe) and A. melanocarpa ‘Galicjanka’ (AGe). Results are reported as mean ± SD (standard deviation) calculated from three replicates (N = 3). Data points marked with different lowercase letters are significantly different within each ecotype over time (Tukey’s HSD test p ≤ 0.05). Uppercase letters indicate significant differences between the two ecotypes within the same time point (Student t-test, p ≤ 0.05).

During the initial phase of T. urticae infestation, an increase in TBARS content was recorded in the leaves of AMe, whereas a decrease was observed in AGe (Figure 3). The initial decrease in TBARS in AGe may be due to an increase in the level of lipid peroxidation products following oxidative stress. After this period, a gradual increase in TBARS levels was observed in both ecotypes. Statistically significant changes were observed only after 14 days of mite feeding in the AGe ecotype, whereas in the AMe ecotype, they were detected after both 1 and 14 days. In AMe leaves, TBARS content increased 3.6-fold compared with the control, while in AGe the increase was 2.1-fold.

3.4. Changes in Antioxidant Enzymes Activity

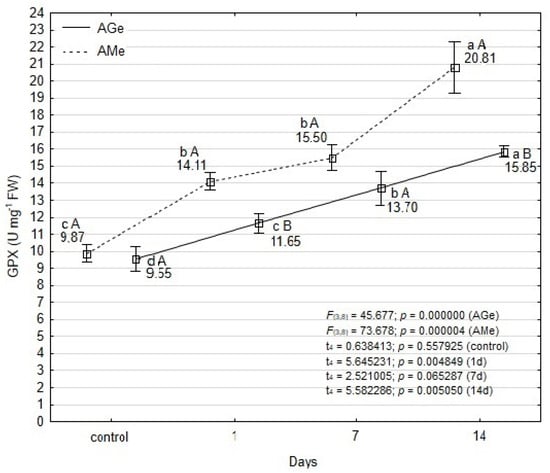

Guaiacol peroxidase (GPX) activity was generally higher in the leaves of AMe compared to the ‘Galicjanka’ cultivar (AGe) (Figure 4). Statistically significant differences between the ecotypes were recorded at three time points: in control plants, and after 1 and 14 days of mite feeding.

Figure 4.

Effect of T. urticae infestation in guaiacol peroxidase (GPX) activity within leaves of A. melanocarpa (AMe) and A. melanocarpa ‘Galicjanka’ (AGe). Results are reported as mean ± SD (standard deviation) calculated from three replicates (N = 3). Data points marked with different lowercase letters are significantly different within each ecotype over time (Tukey’s HSD test p ≤ 0.05). Uppercase letters indicate significant differences between the two ecotypes within the same time point (Student t-test, p ≤ 0.05).

An increase in GPX activity was observed in both ecotypes over the course of the experiment (Figure 4). In AMe leaves, significantly elevated GPX activity was detected at all time points, with the exception of days 1 and 7. The most pronounced increase occurred on day 14, when GPX activity more than doubled relative to the control. In the AGe cultivar, GPX activity increased gradually and consistently, showing statistically significant differences at each sampling time. After 14 days of T. urticae feeding, GPX activity was 1.5-fold higher than in the control. Thus it was stated that differences in GPX activity were mainly dependent on the duration of the spider mite infestation and, to a lesser extent, on the chokeberry cultivar.

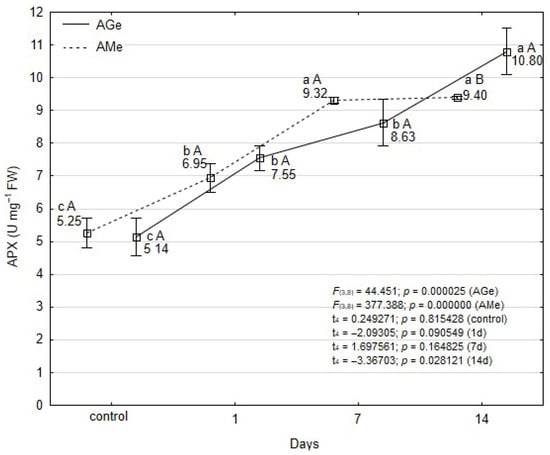

Ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity in the control plant tissues of both ecotypes was at a comparable level (Figure 5). At subsequent time points (days 1 and 7), no statistically significant differences in APX content were observed between the ecotypes. However, by day 14 of the experiment, a significantly higher APX level was recorded in the tissues of the AGe ecotype.

Figure 5.

Effect of T. urticae infestation in ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity within leaves of A. melanocarpa (AMe) and A. melanocarpa ‘Galicjanka’ (AGe). Results are reported as mean ± SD (standard deviation) calculated from three replicates (N = 3). Data points marked with different lowercase letters are significantly different within each ecotype over time (Tukey’s HSD test p ≤ 0.05). Uppercase letters indicate significant differences between the two ecotypes within the same time point (Student t-test, p ≤ 0.05).

In the AMe ecotype, a marked statistically significant increase in APX activity was observed during the first 7 days, showing a 1.8-fold rise compared to the control (Figure 5). Thereafter, the enzyme concentration remained stable. In contrast, the AGe ecotype exhibited a statistically significant increase in APX content as early as day 1, with a further elevation observed on day 14 following T. urticae feeding. Similarly to AMe, the APX concentration in AGe tissues at the end of the experiment was more than twice as high as in the control.

4. Discussion

4.1. Host Plant Acceptance: Comparison of A. melanocarpa Ecotypes

The results of the free-choice test showed that T. urticae displayed higher acceptance of the non-cultivar ecotype (AMe) compared with the cultivar ‘Galicjanka’ (AGe). Similar patterns of differential preference among cultivars have been demonstrated for strawberry, rose, and willow [20,70,71], suggesting that even closely related plant types can vary in their suitability for mites. In plant–mite systems, factors such as morphological barriers, leaf surface chemistry, nutrient composition, and secondary metabolites are known to contribute to antixenosis-based resistance [40,41,42,43,44,72,73]. Although chemical cues were not directly measured, the lower acceptance of AGe suggests the presence of deterrent traits in this cultivar. Overall, the results demonstrate that the two A. melanocarpa ecotypes differ in attractiveness to T. urticae, and that the cultivar AGe may possess features contributing to non-preference–based resistance.

4.2. Comparison of Leaf Morphology in A. melanocarpa Ecotypes

Non-acceptance during host selection is shaped by leaf traits such as surface structure, wax coating, and trichomes, which can hinder pest movement and access to tissues [45,74,75,76]. Therefore, the degree of infestation observed in the free-choice test may partly reflect differences in trichome density between the two tested A. melanocarpa ecotypes.

To date, information on the morphology and distribution of trichomes in A. melanocarpa and its cultivars is limited, highlighting a gap in understanding the mechanisms underlying potential resistance to herbivores. According to the only available description [77], the abaxial surface of the leaf is covered with long, tangled trichomes, with the highest concentration along the midrib, whereas the adaxial surface is nearly glabrous. Trichomes can affect herbivores both mechanically and chemically, with non-glandular types impeding movement and glandular types releasing deterrent or toxic metabolites and, in some cases, volatiles that attract natural enemies [78]. Their role in resistance is well documented in several crops, although studies show that high trichome density does not always translate directly into reduced susceptibility to spider mites [45,75,79,80]. These findings demonstrate that trichome density alone does not fully explain host preference in spider mites.

In the present study, although T. urticae showed a higher preference for the non-cultivar ecotype (AMe), several key demographic parameters—including daily fecundity and egg and larval development time—were less favourable on this host compared with the less preferred ‘Galicjanka’ (AGe). This discrepancy suggests a complex relationship between host acceptance and suitability, indicating that factors beyond trichome morphology influence mite performance.

Our results suggest that trichome density may influence spider mite acceptance of black chokeberry, though chemical cues and other traits likely modulate this response. Further studies integrating leaf chemistry, nutrient composition, and surface microstructure are needed to clarify the mechanisms involved. On the other hand, differences in the colonization of the studied chokeberry cultivars by spider mites may also result from the mechanisms of constitutional and/or induced resistance resulting from the mechanisms of oxidative stress generated by feeding pests.

4.3. Suitability of A. melanocarpa Ecotypes in Relation to Selected Life History Parameters of T. urticae

The suitability of a host plant depends not only on its acceptance but also on the reproductive success and development of herbivores feeding on it. In the present study, daily fecundity of T. urticae ranged from 2.15 eggs per day on the non-cultivar ecotype (AMe) to 2.34 eggs per day on the cultivar ‘Galicjanka’ (AGe). Egg development was significantly longer on AMe (4.79 days) compared with AGe (3.83 days), and a similar trend was observed for the larval stage (2.86 and 2.66 days, respectively), although this difference was not significant. These values fall within the range reported for the species and support the observation that neither ecotype represents a highly suitable host [14,20,70].

Comparable trends have been described in other crop systems, where less preferred cultivars resulted in reduced reproductive output and extended development. Monteiro et al. [14] demonstrated that T. urticae exhibited lower fecundity and prolonged development on less preferred strawberry cultivars (‘Camarosa’, ‘Diamante’), whereas bean (Phaseolus spp.), a highly suitable host, supported rapid population growth and higher reproductive success. Similarly, host-driven differences were documented in T. viennensis, where plum provided the most favourable conditions for development, while cherry and apricot significantly reduced fecundity and extended developmental time [81]. While trichomes may partly explain the differences observed between the two A. melanocarpa ecotypes, they are unlikely to be the sole determinant of host suitability. Host performance in herbivorous mites is typically shaped by multiple interacting characteristics, including nutrient availability (e.g., nitrogen content and C:N ratio), phenolic compounds, surface wax chemistry and tissue hardness, all of which may influence nutrient accessibility, feeding efficiency, detoxification costs and metabolic stress. These combined factors may explain why T. urticae demonstrated higher acceptance of AMe, yet performed better on the less preferred AGe.

Overall, the results suggest that both A. melanocarpa ecotypes impose physiological constraints on mite development, and that the cultivar ‘Galicjanka’ may moderate herbivore performance more effectively despite being less preferred during initial host selection.

4.4. Biochemical Mechanisms of Interactions Between A. melanocarpa and T. urticae

The biochemical responses recorded in our study indicate that oxidative processes are involved in the defence of A. melanocarpa against T. urticae. Control plants of the AGe ecotype, which was less accepted by mites, showed higher basal levels of H2O2 and TBARS compared with AMe, suggesting that these components may contribute to constitutive resistance. Following infestation, both ecotypes exhibited increased levels of H2O2 and TBARS, although this response occurred earlier and more strongly in AMe (after 1 day), whereas AGe responded more gradually, with increases detectable after 14 days. These patterns indicate that oxidative stress is induced by mite feeding and that the timing and intensity of this response are ecotype-dependent.

Herbivore feeding commonly induces oxidative stress in plant–arthropod systems, including spider mites, where cellular disruption causes ROS accumulation and membrane damage [82,83,84]. Similarly to findings in Arabidopsis and Medicago, mite feeding on A. melanocarpa increased H2O2 levels and electrolyte leakage, indicating cell damage and activation of defence responses [82,85]. Importantly, the delayed ROS accumulation observed in AGe resembles patterns described as late defensive events, associated not with signalling, but with tissue damage limitation and containment of further invasion.

The enzymatic response further supports the involvement of redox metabolism in defence. Both GPX and APX activities increased following infestation, with earlier and more pronounced activation in AMe. APX is a key ROS-scavenging enzyme, while GPX may also aid lignification and cell wall reinforcement, limiting herbivore feeding [56,57]. The prolonged activity of these enzymes suggests a sustained defence rather than a transient stress reaction. Comparable patterns have been described in systems where elevated peroxidase activity correlated with reduced herbivore performance and increased tolerance [60,61,62].

Taken together, interactions between A. melanocarpa and T. urticae are governed by distinct resistance strategies arising from differences in host acceptance, mite performance, and the timing of oxidative and enzymatic responses. The contrasting patterns of GPX and APX activity likely reflect their distinct roles in plant defence, with APX primarily detoxifying hydrogen peroxide [56] and GPX contributing to cell wall reinforcement and the formation of quinones that lower tissue digestibility for herbivores [59].

5. Conclusions

In summary, the low fecundity and prolonged development of T. urticae indicate that neither the non-cultivar ecotype (AMe) nor the cultivar ‘Galicjanka’ (AGe) represents a preferred host for this species. Differences in acceptance between ecotypes may be associated with morphological traits such as trichome density, as well as distinct biochemical defence mechanisms. Higher baseline TBARS and H2O2 levels in control AGe plants suggest the involvement of constitutive defence, whereas the post-infestation increase in ROS and the induction of APX and GPX activities highlight the importance of oxidative signalling and antioxidant enzyme activation in induced plant responses.

Collectively, these findings indicate that the defensive capacity of A. melanocarpa arises from the combined effects of anatomical traits and redox-based metabolic pathways. Importantly, traits identified in this study—including trichome density, ROS accumulation patterns, and APX/GPX activity—have the potential to serve as practical markers of resistance in breeding programmes. These results underscore the value of A. melanocarpa as a promising genetic resource for developing berry and fruit crop cultivars with enhanced tolerance to spider mites and reduced reliance on chemical plant protection measures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G.-D. and K.R.; methodology, E.G.-D. and K.R., and K.G.; software E.G.-D. and K.G.; validation, K.G.; formal analysis, K.G. and C.S.; investigation, E.G.-D., K.G. and K.R.; data curation, E.G.-D. and C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G.-D., K.R., C.S. and K.G.; writing—review and editing, E.G.-D., C.S. and K.G.; visualization, E.G.-D.; supervision, E.G.-D. and K.G.; project administration, E.G.-D.; funding acquisition, E.G.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Life Sciences in Lublin, grant number SUBB.WOK.19.019 and Siedlce University, grant number 197/24/B.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Monika Poniewozik for her help with rearing of mites and for providing technical support, as well as Julia Drabik for preparing the schematic representation of the modified Munger cell.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Engels, G.; Brinckmann, J. Aronia czarna, Aronia melanocarpa. Am. Bot. Counc. 2014, 101, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rozpara, E.; Morgaś, H.; Filipczak, J.; Meszka, B.; Hołdaj, M.; Łabanowska, B.H.; Sekrecka, M.; Sobiczewski, P.; Lisek, J.; Danelski, W. Metodyka Produkcji Owoców Aronii Metodą Ekologiczną; Inhort: Skierniewice, Poland, 2016; 27p. [Google Scholar]

- Smolik, M.; Ochmian, I.; Smolik, B. RAPD and ISSR methods used for fingerprinting selected, closely related cultivars of Aronia melanocarpa. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Napoca 2011, 39, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppsson, N. The effect of cultivar and cracking on the fruit quality in black chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) and the hybrids between chokeberry and rowan (Soubzis). Gartenbauwissenschaft 2000, 65, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppsson, N.; Johansson, R. Changes in fruit quality in black chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) during maturation. J. Hortic. Sci. Biot. 2000, 75, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulling, S.E.; Rawel, H.M. Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa)—A review on the characteristic components and potential health effects. Planta Med. 2008, 74, 1625–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enescu Mazilu, I.C.; Cosmulescu, S. Effect of cultivar, year, and their interaction on nutritional and energy value components in Aronia melanocarpa berries. Not. Bot. Horti. Agrobot. 2023, 51, 13478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strigl, A.W.; Leitner, E.; Pfannhauser, W. Die schwarze Apfelbeere (Aronia melanocarpa) als natürliche Farbstoffquelle. Dtsch. Lebensmitt. Rundsch. 1995, 91, 177–180. [Google Scholar]

- Ochmian, I.; Grajkowski, J.; Smolik, M. Comparison of Some Morphological Features, Quality and Chemical Content of Four Cultivars of Chokeberry Fruits (Aronia melanocarpa). Not. Bot. Horti. Agrobo. 2012, 40, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska-Drabik, E. Trachycera advenella (Zinck.) (Lepidoptera, Pyralidae)—A new pest on black chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa). Prog. Plant Prot. 2009, 49, 531–534. [Google Scholar]

- Górska-Drabik, E. Owady i roztocza zagrażające aronii czarnoowocowej. In Materiały IX Konferencji Sadowniczej “Trendy w uprawie gatunków jagodowych i pestkowych”; Związku Sadowników RP: Grójec, Poland, 2013; pp. 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Migeon, A.; Nouguier, E.; Dorkeld, F. Spider mites web: A comprehensive database for the Tetranychidae. In Trends in Acarology; Sabelis, M., Bruin, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 557–560. [Google Scholar]

- Spider Mites Web. Available online: https://www1.montpellier.inrae.fr/CBGP/spmweb/public/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Monteiro, L.B.; Kuhn, T.M.; Mogor, A.F.; da Silva, E.D. Biology of the Two-Spotted Spider Mite on Strawberry Plants. Neotrop. Entomol. 2014, 43, 183–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounfour, M.; Tanigoshi, L.K.; Chen, C.; Cameron, S.; Klauer, S. Chlorophyll Content and Chlorophyll Fluorescence in Red Raspberry Leaves Infested with Tetranychus urticae and Eotetranychus carpini borealis (Acari: Tetranychidae). Environ. Entomol. 2002, 31, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warabieda, W. Effect of two-spotted spider mite population (Tetranychus urticae Koch) on growth parameters and yield of the summer apple cv. Katja. Hort. Sci. 2015, 42, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorupska, A. Resistance of apple cultivars to two-spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acarina, Tetranychidae). Part I. Bionomy of two-spotted spider mite on selected cultivars of apple trees. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2004, 44, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Leus, L.; Minguely, C.; Van Poucke, C.; Audenaert, J.; Witters, J. Cultivar susceptibility and stress hormone response in raspberry (Rubus ideaus) to two-spotted spider mite (Tetranychus urticae). Acta Hortic. 2020, 1277, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehri, K.; Gulami, R.; Geroh, M. Host plant responses, biotic stressors and management strategies for the control of Tetranychus utricae Koch (Acarina: Tetranychidae). Agric. Rev. 2014, 35, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadi Dana, E.; Sadeghi, A.; Maroufpoor, M.; Khanjani, M.; Babolhavaeji, H.; Ullah, M.S. Comparison of the life table and reproduction parameters of the Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidea) on five strawberry varieties. Int. J. Acarol. 2018, 44, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari-Shiri, H.; Hajiqanbar, H.; Zalucki, M.P.; Fathipour, Y. The role of host plant resistance as a critical factor for the management of Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) in strawberry. Persian J. Acarol. 2025, 14, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.K.P.S.; Craemer, C. Mites (Arachnida: Acari) as crop pests in southern Africa: An overview. Afr. Plant Prot. 1999, 5, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bensoussan, N.; Santamaria, M.E.; Zhurov, V.; Diaz, I.; Grbić, M.; Grbić, V. Plant-herbivore interaction: Dissection of the cellular pattern of Tetranychus urticae feeding on the host plant. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrella Santamaria, M.; Arnaiz, A.; Rosa-Diaz, I.; González-Melendi, P.; Romero-Hernandez, G.; Ojeda-Martinez, D.A.; Garcia, A.; Contreras, E.; Martinez, M.; Diaz, I. Plant Defenses against Tetranychus urticae: Mind the Gaps. Plants 2020, 9, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowska, M.; Fiedler, Ż.; Bocianowski, J.; Torzyński, K. The effect of spider mites (Acari: Tetranychidae) occurrence on sugar beet yield depending on the variety. Agron. Sci. 2018, 73, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotem, K.A.; Agrawal, A.A. Density dependent population growth of the two-spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae, on the host plant Leonurus cardiaca. Oikos 2003, 103, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinosci, C.; Magalhães, S.; Macke, E.; Navajas, M.; Carbonell, D.; Devaux, C.; Olivieri, I. Effects of host plant on life-history traits in the polyphagous spider mite Tetranychus urticae. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 3151–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puspitarini, R.D.; Fernando, I.; Rachmawati, R.; Hadi, M.S.; Rizali, A. Host plant variability affects the development and reproduction of Tetranychus urticae. Int. J. Acarol. 2021, 47, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropczyńska-Linkiewicz, D.; Garnis, J.; Jaworski, S.; Sagan, A.; Krężlewicz, M. Drapieżne roztocza (Acari: Phytoseiidae) występujące na roślinach w otoczeniu plantacji krzewów jagodowych. Pog. Plant Prot. 2009, 49, 1048–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Łabanowska, B.H.; Gajek, D. Control of the twospottedspider mite Tetranychus Urticae Koch. on black currant. Acta Hortic. 1993, 352, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajek, D. Species Composition Of Tetranychid Mites (Tetranychidae) And Predatory Mites (Phytoseiidae) Occurring On Raspberry Plantations In Poland. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2003, 43, 353–360. [Google Scholar]

- Łabanowska, B.H.; Tartanus, M.; Piotrowski, W.; Sobieszek, B. Usefulness of products with mechanical action to control of two-spotted spider mite (Tetranychus urticae Koch.) on strawberry. Zesz. Nauk. Instyt. Ogrodn. 2017, 25, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Jonathan, F.T.; Mahendranathan, C. Impact of climate change on plant diseases. Agrieast J. Agric. Sci. 2024, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.S.; Wang, B.X.; Wang, X.J.; Lin, Q.C.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.F.; van Baaren, J.; Bebber, D.P.; Eigenbrode, S.D.; Zalucki, M.P.; et al. Crop pest responses to global changes in climate and land management. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 264–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, S.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, W.; Jin, B. Plant responses to herbivory, wounding, and infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mithöfer, A.; Boland, W. Recognition of Herbivory-Associated Molecular Patterns. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fürstenberg-Hägg, J.; Zagrobelny, M.; Bak, S. Plant Defense against Insect Herbivores. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 10242–10297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, D. Host plant resistance. In Insect Pest Management; Dent, D., Ed.; CABI Publishing: Oxfordshire, UK, 2000; pp. 123–179. [Google Scholar]

- Sarfraz, M.; Dosdall, L.M.; Keddie, B.A. Diamondback moth-host plant interactions: Implications for pest management. Crop Prot. 2006, 25, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, R.H. Insect resistance in crop plants. Soil Sci. 1951, 72, 481. [Google Scholar]

- Dąbrowski, Z.T. Mechanizmy odporności roślin na szkodniki. In Podstawy Odporności Roślin na Szkodniki; PWRiL: Warszawa, Poland, 1976; pp. 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kogan, M.; Ortman, E.F. Antixenosis—A new term proposed to define Painter’s “non-preference” modality of resistance. Bull. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1978, 24, 175–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, Z.T. Podstawy Odporności Roślin Uprawnych na Szkodniki; PWRiL: Warszawa, Poland, 1988; 260p. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.M. Plant Resistance to Insects. A Fundamental Approach; Joan Willey & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1989; 286p. [Google Scholar]

- Kiełkiewicz-Szaniawska, M. Strategie Obronne Roślin Pomidorów (Lycopersicon Esculentum Miller) Wobec Przędziorka Szklarniowca (Tetranychus Cinnabarinus Boisduval, Acari: Tetranychidae); Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warszawa, Poland, 2003; Volume 264, 140p. [Google Scholar]

- Boczek, J. Niechemiczne Metody Zwalczania Szkodników Roślin; Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warszawa, Poland, 1992; 242p. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, C.; Santiago-Vazquez, L.; Paul, V. Toxin release in response to oxidative stress and programmed cell death in the cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa. Aqu. Toxicol. 2006, 78, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minibayeva, F.; Beckett, R.P.; Kranner, I. Roles of Apoplastic Peroxidases in Plant Response to Wounding. Phytochemistry 2015, 112, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Kuc, J. Peroxidase-generated hydrogen peroxide as a source of antifungal activity in vitro and on tobacco leaf disks. Phytopathology 1992, 82, 696–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, K.; Hirt, H. Reactive oxygen species: Metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004, 55, 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, P.U.; Jyothsna, Y. Biochemical and enzymatic changes in rice plants as a mechanism of defense. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2010, 32, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S. The language of reactive oxygen species signaling in plants. J. Bot. 2012, 2012, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant Machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, D.; Uniyal, N.; Panneerselvam, P.; Senapati, A.; Ganeshamurthy, A.N. Role of mycorrhiza and its associated bacteria on plant growth promotion and nutrient management in sustainable agriculture. Int. J. Life Sci. Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Caverzan, A.; Passaia, G.; Rosa, S.B.; Ribeiro, C.W.; Lazzarotto, F.; Margis-Pinheiro, M. Plant responses to stresses: Role of ascorbate peroxidase in the antioxidant protection. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2012, 35, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passardi, F.; Cosio, C.; Penel, C.; Dunand, C. Peroxidases have more functions than a swiss army knife. Plant Cell Rep. 2005, 24, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiti, F.; Verdeil, J.L.; El Hadrami, I. Effect of jasmonic acid on the induction of polyphenoloxidase and peroxidase activities in relation to date palm resistance against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2009, 74, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranger, C.M.; Singh, A.P.; Frantz, J.M.; Cañas, L.; Locke, J.C.; Reding, M.E.; Vorsa, N. Influence of silicon on resistance of Zinnia elegans to Myzus persicae (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Environ. Entomol. 2009, 38, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Steffens, J.C. Overexpression of polyphenol oxidase in transgenic tomato plants results in enhanced bacterial disease resistance. Planta 2002, 2, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi-Werle, L.; Heng-Moss, T.M.; Hunt, T.E.; Baldin, E.L.L.; Baird, L.M. Characterization of Peroxidase Changes in Tolerant and Susceptible Soybeans Challenged by Soybean Aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2014, 107, 1985–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulsen, O.; Eickhoff, T.; Heng-Moss, T.; Shearman, R.; Baxendale, F.; Sarath, G.; Lee, D. Characterization of peroxidase changes in resistant and susceptible warm-season turfgrasses challenged by Blissus occiduus. Arthropod. Plant Interact. 2010, 4, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Ruban, A.V.; Noctor, G. Viewing oxidative stress through the lens of oxidative signalling rather than damage. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, V.C.; Tran, N.T.; Nguyen, D.S. The involvement of peroxidases in soybean seedlings’ defense against infestation of cowpea aphid. Arthropod-Plant Int. 2016, 10, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druciarek, T.; Lewandowski, M.; Kozak, M. Demographic parameters of Phyllocoptes adalius (Acari: Eriophyoidea) and influence of insemination on female fecundity and longevity. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2014, 63, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, S.; Choudhuri, M.A. Glycolate metabolism of three submerged aquatic angiosperms during aging. Aquat. Bot. 1981, 12, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, R.L.; Packer, L. Effect of light on lipid peroxidation in chloroplasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1968, 19, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małolepsza, A.; Urbanek, H.; Polit, J. Some biochemical of strawberry plants to infection with Botrytis cinerea and salicylic acid treatment. Acta Agrobot. 1994, 47, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Asada, K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981, 22, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golizadeh, A.; Ghavidel, S.; Razmjou, J.; Fathi, S.A.A.; Hassanpour, M. Comparative life table analysis of Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae) on ten rose cultivars. Acarologia 2017, 57, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorupska, A. Food acceptance of spider mite (Schizotetranychus schizopus Zacher) and two-spotted spider mite (Tetranychus urticae Koch.) in the selection basket willow varieties (Salix viminalis L.). Prog. Plant Prot. 2012, 52, 456–460. [Google Scholar]

- van den Boom, C.E.M.; van Beek, T.A.; Dicke, M. Differences among plant species in acceptance by the spider mite Tetranychus urticae Koch. J. Appl. Entomol. 2003, 127, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorupska, A.; Rogalińska, M. Food preference of two-spotted spider mite (Tetranychus urticae Koch) to choosing annual weed species in cereals. Prog. Plant Prot. 2012, 52, 461–466. [Google Scholar]

- Luczynski, A.; Isman, M.B.; Raworth, D.A.; Chan, C.K. Chemical and morphological factors of resistance against the twospotted spider mite in beach strawberry. J. Econ. Entomol. 1990, 83, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; Brennan, R.M.; Graham, J.; Karley, A.J. Plant Defense against Herbivorous Pests: Exploiting Resistance and Tolerance Traits for Sustainable Crop Protection. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakha, M.; Bouba, N.; Ramasamy, S.; Regnard, J.-L.; Hanson, P. Evaluation of wild tomato accessions (Solanum spp.) for resistance to two-spotted spider mite (Tetranychus urticae Koch) based on trichome type and acylsugar content. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2017, 64, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradova, Y.; Shelepova, O.; Vergun, O.; Grygorieva, O.; Kuklina, A.; Brindza, J. Differences between Aronia Medik. taxa on the morphological and biochemical characters. Environ. Res. Engin. Manag. 2018, 74, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempruch, C. Interakcje między mszycami a roślinami we wstępnych etapach wyboru żywiciela. Kosmos 2012, 61, 573–586. [Google Scholar]

- Alba, J.M.; Montserrat, M.; Fernández-Muñoz, R. Resistance to the two-spotted spider mite (Tetranychus urticae) by acylsucroses of wild tomato (Solanum pimpinellifolium) trichomes studied in a recombinant inbred line population. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2009, 47, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Tooker, J.; Peiffer, M.; Chung, S.; Felton, G.W. Role of trichomes in defense against herbivores: Comparison of herbivore response to woolly and hairless trichome mutants in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Planta 2012, 236, 1053–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Tian, J.; Shen, Z. Assessment of sublethal effects of clofentezine on life-table parameters in hawthorn spider mite (Tetranychus viennensis). Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2006, 38, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, M.E.; Martinez, M.; Arnaiz, A.; Ortego, F.; Grbic, V.; Diaz, I. MATI, a novel protein involved in the regulation of herbivore-associated signaling pathways. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Baldwin, I.T. New insights into plant responses to the attack from insect herbivores. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2010, 44, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukasik, I.; Goławska, S.; Wojcicka, A.; Goławski, A. Effect of host plants on antioxidant system of pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. Bull. Insect. 2011, 64, 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Leitner, M.; Boland, W.; Mithöfer, A. Direct and indirect defences induced by piercing-sucking and chewing herbivores in Medicago truncatula. New Phytol. 2005, 167, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).