Abstract

In recent years, the rapidly changing environment and climate have emphasized the need for sustainable development, particularly in the agricultural sector. Tractors are the most widely used machines in agriculture, making their energy efficiency crucial not only for environmental protection but also for reducing farming costs and enhancing economic sustainability. This study applies Yeo–Johnson data transformation to normalize the discretized data of 111 tractor models, enabling the classification of agricultural tractors based on energy efficiency. Tractors were categorized into five classes according to energy efficiency, and the upper limit of each class was used to quantify the rate of improvement in energy efficiency. Furthermore, a comparative analysis between the classification model from 2006 to 2010 and that from 2016 to 2020 demonstrated that the latter exhibits superior energy consumption efficiency. Specifically, the 2016–2020 model showed an improvement in energy efficiency ranging from approximately 20.57% to 54.86% across all power categories, with higher-rated power tractors achieving greater improvements. This comparison confirms that the energy efficiency of tractors in the latest classification model is further improved, reflecting the substantial technological advancements made over the past decade.

1. Introduction

Global warming is one of the major consequences of human activities, caused primarily by the excessive use of fossil fuels as energy sources. This results in increased concentrations of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the atmosphere and a subsequent rise in the Earth’s average surface temperature [1,2].

In recent decades, the rapid increase in energy consumption and the corresponding rise in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions have had serious impacts on the global environment, raising widespread concerns [3]. Energy plays a critical role in sustaining economic growth and living standards in modern society and is considered one of the key variables in achieving sustainable development. According to U.S. Energy Information Administration’s International Energy Outlook 2019 [4], energy consumption in the industrial sector is projected to increase by approximately 30% by 2050, with energy demand for final products expected to exceed 310 quadrillion BTUs globally.

This growing energy demand is directly linked to the increased consumption of fossil fuels, which has been identified as a major contributor to climate change and global warming [5,6]. In fact, global CO2 emissions increased from 20.18 billion tons in 1990 to 32.314 billion tons in 2016 [7]. Despite the emergence of alternative energy sources, the majority of the world’s energy supply still relies on fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas [8], leading to a complex set of challenges including supply insecurity, resource depletion, climate disasters, and rising economic costs.

A long-term trend in CO2 concentration from 1950 to 2013 illustrates how industrialization, centered around fossil fuel consumption, has steadily increased atmospheric CO2 levels [9]. As of 2015, approximately 45% of CO2 emissions originated from coal combustion, 35% from oil, and 20% from natural gas [7].

In response, the international community has established several climate agreements aimed at reducing GHG emissions. The Kyoto Protocol [10], the Copenhagen Accord [11], and the Paris Agreement [12] have served as foundations for national policies addressing climate change. In particular, Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7 of the United Nations calls for “affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all” and sets energy efficiency improvement and CO2 emission reduction as core targets to be achieved by 2030 [13].

These policy directions are significant not only from an environmental perspective but also in terms of economic efficiency. Enhancing energy efficiency can reduce dependence on imported energy, lower costs for households and industries [14], and have positive effects across multiple sectors such as buildings, transportation, manufacturing, and energy production [15].

In line with this global trend, individual countries have formulated their own strategies. For example, the European Union established the “Europe 2020 Strategy” and later the “2030 Climate and Energy Framework,” which set targets for a 32.5% improvement in energy efficiency, a minimum of a 32% share of renewable energy, and a 40% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions [16,17,18]. Lithuania introduced its “National Energy Independence Strategy” in 2018 with the goal of expanding renewable energy use and improving energy efficiency by 2050 [19]. Similarly, China is implementing policies to reduce coal dependency and improve energy intensity [20], while the United States is pursuing various strategies to reduce carbon emissions.

This shift in energy policy is also emerging as a critical issue not only in industry, transportation, and construction but also in the agricultural sector. Although agriculture has traditionally been considered a low-energy-consuming industry, the expansion of mechanized and large-scale intensive farming—including operations such as tillage, seeding, and harvesting—has led to a significant increase in fossil fuel-based energy consumption within the sector [21,22].

Among agricultural machinery, the tractor is one of the most frequently used and fuel-intensive machines. For example, tillage operations alone can consume approximately 71.1 L of diesel per hectare annually, which corresponds to about 2.68 GJ/ha/year [23].

Therefore, establishing an objective energy efficiency evaluation system and a standardized rating scheme for high-fuel-consuming agricultural machines such as tractors could serve as an effective strategy to promote rational choices among users and to enhance energy efficiency and reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the agricultural sector [24,25].

Previous studies have proposed a wide range of approaches to predict and evaluate the fuel consumption and energy efficiency of agricultural tractors. In the early stages, Harris [26,27] and Grisso et al. [28] laid the groundwork for empirical and analytical research by developing predictive models based on variables such as engine speed, throttle position, drawbar power, and fuel consumption. Subsequent studies actively developed systematic classification frameworks to quantitatively assess tractor energy efficiency. For example, Gil-Sierra et al. [29] proposed a foundational methodology for energy efficiency classification, which was later adapted to national contexts by Türker et al. [30] in Turkey and Shin et al. [31] in Korea. In the Korean case, a tractor fuel efficiency rating system tailored to local agricultural conditions was established using OECD standard test data. Additionally, Shin et al. [32] presented a method for fuel efficiency classification of agricultural tractors based on ASABE standard procedures. These studies provided objective and quantitative benchmarks that enable consistent comparison and evaluation across various tractor models. In parallel, Kim et al. [33] and Kim et al. [34] developed fuel consumption prediction models by incorporating simulation and field data that reflect actual farming conditions. Kocher et al. [35] introduced a generalized fuel consumption model based on uniform tractor test data, allowing for consistent comparisons across various machine types. Beyond modeling energy efficiency, a number of studies have also examined how tractor design and operational conditions influence energy efficiency. For instance, Monifar et al. [36] analyzed differences in performance and fuel consumption depending on the drive system type, while Kolator [37] modeled fuel consumption characteristics under varying load and traction conditions. In addition, Mohan et al. [38] provided a comprehensive review of engine control strategies—such as fuel injection timing and pressure adjustment—aimed at improving performance and reducing emissions. More recently, TeKolste et al. [39] reviewed the evolution of the U.S. EPA’s tiered nonroad diesel exhaust emission standards and examined how tractor fuel efficiency changed as these standards became more stringent.

In recent years, a growing body of research has focused explicitly on improving the fuel and energy efficiency of agricultural tractors. Shafaei et al. analyzed the overall energy efficiency of the tractor–implement system during plowing operations and quantitatively clarified the individual and combined effects of forward speed and plowing depth on this efficiency [40]. Bolotokov et al. demonstrated that applying a helical groove to the injector needle of a tractor diesel engine improves spray characteristics and reduces fuel-delivery unevenness, thereby increasing engine power and decreasing specific fuel consumption [41]. From a control perspective, Feng et al. proposed a Pontryagin’s Minimum Principle-based energy-saving control strategy for parallel hybrid tractors that incorporates working-condition prediction and demonstrated that it can significantly reduce the total energy consumption cost under typical plowing conditions [42]. Yin et al. proposed an optimized fuzzy control strategy for high-horsepower series hybrid tractors that combines PSO–SVM-based working-condition recognition with a genetic algorithm and demonstrated that the proposed method can adaptively manage power distribution according to varying working conditions, thereby reducing the overall fuel consumption by up to 6.96% [43].

At a wider system level, several recent studies have evaluated tractor energy performance in terms of powertrain configuration and long-term design evolution. Kivekäs and Lajunen quantitatively compared the energy efficiency and Well-to-Wheels CO2 emissions of various tractor powertrains (diesel, gas, hybrid, hydrogen, and electric) based on the representative work cycles of Finnish grain farms and demonstrated that not only the technical characteristics of the powertrain but also differences in fuel production pathways critically determine the achievable reductions in overall carbon emissions [44]. Herranz-Matey conducted a methodological and parametric assessment of tractor productivity and efficiency evolution using standardized test data, revealing how changes in propulsion system design over the past decades have affected effective power utilization and specific fuel consumption at the fleet level [45]. These recent contributions clearly show that improving the energy efficiency of agricultural tractors is an active research topic spanning component design, control strategies, and alternative powertrains. However, relatively few studies have quantitatively assessed how energy-efficiency rating indices for agricultural tractors have evolved over time under a national grading scheme or have evaluated to what extent technological developments have translated into measurable improvements in standardized fuel-efficiency classes.

Despite these valuable contributions focusing on fuel consumption characteristics, classification, prediction, and influencing factors, few studies have quantitatively analyzed whether energy efficiency has been improved over time. In particular, empirical evaluations of the effectiveness of energy efficiency grading systems are limited. The extent to which technological advancements have contributed to improvements in tractor energy efficiency also remains underexplored and warrants further empirical investigation.

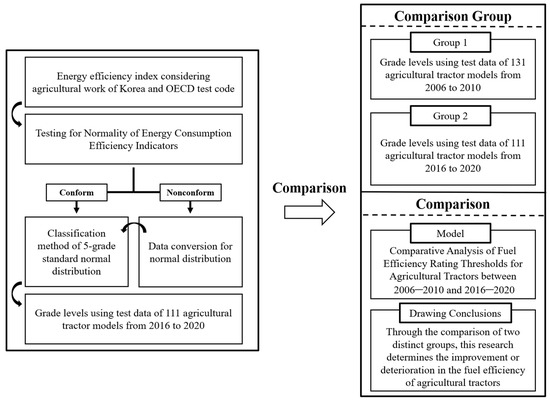

This study aims to evaluate the energy efficiency of agricultural tractors—an essential factor in sustainable farming practices and to monitor the rate of energy efficiency enhancement. Figure 1 below presents an overview of the entire analytical procedure used in this study. Firstly, energy efficiency index values, considered the characteristics of agricultural works in Korea, were evaluated based on the data in compliance with OECD test code from 111 agricultural tractor models between 2016 and 2020. Secondly, the normality tests such as the Shapiro–Wilk, Anderson–Darling, and Lilliefors tests were conducted on the dataset to establish the normal distribution.

Figure 1.

Comparative Analysis Framework for Fuel Efficiency Ratings of Agricultural Tractors.

If the data conformed to normality, a five-grade classification method based on the standard normal distribution was applied. If not, the data were transformed into a normal distribution using methods such as the Yeo–Johnson transformation, followed by grade classification. The resulting grade thresholds were then used for comparative analysis. The comparison targeted two groups: 131 tractor models from 2006 to 2010 (Group 1) and 111 tractor models from 2016 to 2020 (Group 2). By analyzing the differences in the energy efficiency index values between the two groups, it was proved that energy efficiency was improved from technological advancements during the time between 2010 and 2020.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tractor Model Data Collection and Classification

This research is founded on the agricultural tractor fuel consumption prediction method developed by Shin et al. [31], encompassing a comprehensive study of 111 tractor models manufactured over the recent five years (2016 to 2020), incorporating a variety of models. To ensure the study’s reliability and accuracy, meticulous data collection for each tractor model was imperative.

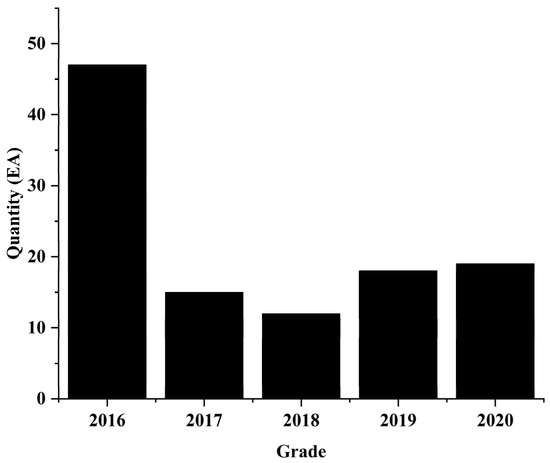

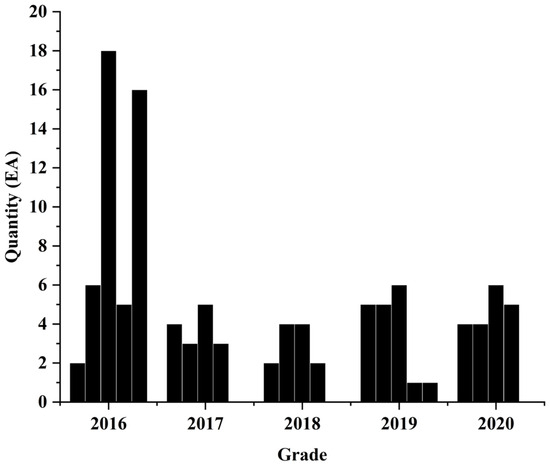

Consequently, the study leveraged test reports on tractor models provided by the Korea Agricultural Technology Promotion Agency as the primary data source. These data furnish extensive details on the performance and fuel efficiency of tractors, thereby offering significant foundational material for the research. As depicted in Figure 2, the yearly distribution of analyzed tractor models consists of 47 units in 2016, 15 units in 2017, 12 units in 2018, 18 units in 2019, and finally, 19 units in 2020. Furthermore, the distribution of agricultural tractors by horsepower per year is meticulously detailed in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Number of Agricultural Tractor Models by Year (2016–2020).

Table 1.

Number of agricultural tractors in South Korea from 2016 to 2020.

In this study, the samples were derived from all tractor models that received official performance tests from the Korea Agricultural Technology Promotion Agency in the corresponding years. However, due to discrepancies in the number of tested units across years, the influence of individual model characteristics on the annual mean may become relatively large in years with smaller sample sizes (e.g., 15 units in 2017). Consequently, the energy efficiency values for such years may not fully represent the overall trend. To minimize the effects of this sample imbalance, the data were aggregated into five-year intervals rather than analyzed on a yearly basis, after which energy efficiency rating was conducted by horsepower category.

2.2. Energy Efficiency Index

Apart from other energy efficiency systems, there was a need for a unique index to measure and manage the energy efficiency of agricultural tractors. In response to this need, Shin et al. [31] developed an index to evaluate the energy efficiency of agricultural tractors. The index primarily focused on evaluating both the tractor’s power take-off (PTO) and Drawbar, and it included the following categories.

- Fuel efficiency with full engine throttle.

- Fuel efficiency with reduced engine throttle.

- Fuel efficiency in field works by PTO power.

- Fuel efficiency in field works by drawbar power.

The OECD test code, recognized and approved globally, served as the basis for developing the energy efficiency index. According to Shin and Kim [32], data for the OECD tractor test reports were gathered under these specified conditions:

- Varying engine speed with full load: PTO power, engine speed, and fuel consumption were considered as a function of engine speed under full load.

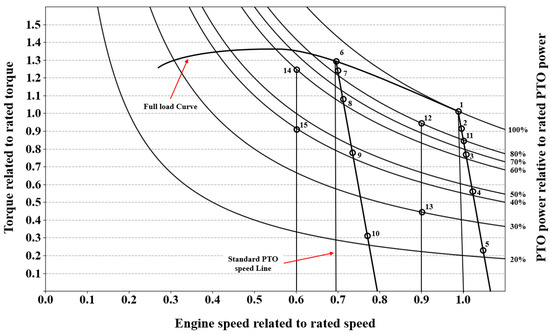

- Varying load at rated engine speed with full throttle: PTO power, engine speed, and fuel consumption were obtained at five points with corresponding loads of 100%, 85%, 64% (75% of 85% torque), 43% (50% of 85% torque), and 21% (25% of 85% torque) of the torque corresponding to the maximum power at the rated engine speed (points 1 to 5 in Figure 3).

Figure 3. Engine operating conditions used for fuel consumption measurement in OECD tractor tests.

Figure 3. Engine operating conditions used for fuel consumption measurement in OECD tractor tests. - Varying load at the standard PTO speed with full throttle: PTO power, engine speed, and fuel consumption were considered at five points with corresponding loads of 100%, 85%, 64% (75% of 85% torque), 43% (50% of 85% torque), and 21% (25% of 85% torque) of the torque corresponding to the maximum power at the standard PTO speed (points 6 to 10 in Figure 3).

- Partial load at reduced engine speed with reduced throttle: Engine speed and fuel consumption were considered at five points with a load of 80% of rated PTO power at the maximum engine speed setting, 80% of rated PTO power at 90% of rated engine speed, 40% of rated PTO power at 90% of rated engine speed, 60% of rated PTO power at 60% of rated engine speed, and 40% of rated PTO power at 60% of rated engine speed (points 11 to 15 in Figure 3).

- Maximum drawbar power with different gears at the rated engine speed: Engine speed and power, pull, pull speed, slip, and fuel consumption were considered for all transmission gears.

This data can be integrated to develop a classification index for the overall fuel efficiency of agricultural tractors. Equation (1), established using data from points 1 to 5 out of the 15 points in Figure 3, considers fuel efficiency at rated speed when operating with full throttle. Equation (2), formulated based on data from points 6 to 10, represents the fuel efficiency at standard PTO speed with full throttle. Finally, Equation (3), developed using data from points 11 to 15, applies the fuel efficiency at rated engine speed with reduced throttle [32].

where is sub-index to rate fuel efficiency at rated engine speed with full throttle (L/kW·h), is sub-index to rate fuel efficiency at standard PTO speed with full throttle (L/kW·h), is sub-index to rate fuel efficiency at reduced engine speed with reduced throttle (L/kW·h), is fuel consumption required to produce PTO power, (L/h), is PTO power corresponding to point in Figure 3 (kW).

Based on the study by (Shin and Kim, 2012) [31], the data reflects the drawbar work for two specific scenarios. When plowing at a speed of 3.0 km/h, which is considered the standard pulling speed for this activity, and when rotovating at a speed of 7.5 km/h, which is also regarded as the typical pulling speed for that task, the drawbar work measurements were recorded as indicated in the data.

where is sub-index to rate fuel efficiency for drawbar works (L/kW·h), is fuel consumption at pull speed closest to 3.0 km/h (L/h), is fuel consumption at pull speed closest to 7.5 km/h (L/h), is drawbar power at pull speed closest to 3.0 km/h (kW), is drawbar power at pull speed closest to 7.5 km/h (kW).

As described in [32], the final energy efficiency index representing agricultural activities is defined by assigning weights to its sub-indexes. In this study, the weighting factors were determined in the same manner, based on the nationwide tractor operation-time statistics reported by the Rural Development Administration (RDA) in 2011, as summarized in Table 2 [46].

Table 2.

Annual Tractor Usage Status in Korea for 2011.

Although the annual tractor usage patterns in 2019, as shown in Table 3, differ somewhat from those in 2011, the present study applied the 2012 operation-time dataset used in the original development of the energy efficiency index in order to ensure consistency of methodology and maintain comparable analytical conditions with the previous work. [47].

Table 3.

Annual Tractor Usage Status in Korea for 2019.

The components of this index are as follows:

where is classification index to classify tractors by energy efficiency (L/kW·h).

2.3. Data Conversion

The fuel consumption rate data for tractors, influenced by various operational conditions and environmental factors, exists in a discretized form encompassing both positive and negative values. This often fails to meet the assumption of normality in data analysis, thereby affecting the accuracy and reliability of statistical analysis. To address this issue, the present study applied the Yeo–Johnson data transformation technique to enhance the normality of the data.

The Yeo–Johnson transformation is a technique used to transform data closer to a normal distribution, serving as an extension that encompasses the Box–Cox transformation. It is applicable to data containing both positive and negative values, making it particularly useful for complex datasets, such as the tractor fuel consumption rate data discussed in this research. The primary goal of the Yeo–Johnson transformation is to reduce the skewness of the data and transform it into a shape that is closer to a normal distribution.

The transformation process is defined according to the input data x and the transformation parameter as follows [48]:

where denotes the transformed data, represents the original observations, and λ is the transformation parameter. Through this transformation, the original skewed data are mapped into a distribution that is closer to normality, making them more suitable for subsequent statistical analysis and modeling.

To determine the optimal value of the transformation parameter λ, the present study employed the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) approach. Let be the original observations and be the transformed values obtained from Equation (7) for a given . The sample mean and variance of the transformed data are defined as:

Assuming that the transformed data follow a normal distribution with mean and variance , the profile log-likelihood function for can be written as

where denotes the Jacobian term associated with the Yeo–Johnson transformation. The maximum likelihood estimate is then obtained by maximizing with respect to ,

In practice, was obtained numerically using a one-dimensional optimization procedure.

2.4. Normality Test

Given the unique nature of our dataset, encompassing approximately 100 observations that are both small in size and discretized, we adopted a comprehensive approach to assess the normality of the transformed fuel efficiency data. To ensure a robust and accurate evaluation, we utilized three distinct normality tests: the Shapiro–Wilk test, the Anderson–Darling test, and the Lilliefors test. Each test offers unique advantages and sensitivities to different aspects of the data distribution, enabling us to conduct a thorough analysis of the dataset’s adherence to normality. This multifaceted approach not only leverages the strengths of each test but also provides a holistic view of the data’s distribution characteristics, ensuring the reliability and validity of our findings.

2.4.1. Shapiro–Wilk Test

The Shapiro–Wilk Test is widely utilized for assessing whether sample data follow a normal distribution, demonstrating high sensitivity for small datasets. This test evaluates the correlation between the order statistics of the sample and the expected values of a normal distribution. If the p-value is below the predefined significance level (0.05), it concludes that the data do not follow a normal distribution.

The normality test using the Shapiro–Wilk method is based on the test statistic as shown in Equation (11) [49].

where represent the order statistics corresponding to the random sample , The parameter = was approximated for sample of size , as described in [50], The normality hypothesis is rejected at a test size if , where is the quantile od the null distribution of , which is location-scale invariant.

2.4.2. Anderson–Darling Test

The Anderson–Darling test evaluates the goodness-of-fit by measuring the discrepancy between the empirical distribution of the sample data and the assumed theoretical distribution. A larger test statistic indicates a greater deviation from the assumed distribution, suggesting that the data is less likely to follow it. Notably, this test is more sensitive to deviations in the tails of the distribution compared to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The Anderson–Darling test statistic (A2) is given by [51]:

where is the sample size, represents the ordered sample data transformed according to the assumed distribution, and denotes the cumulative function (CDF) of the assumed distribution.

2.4.3. Lilliefors Test

The Lilliefors (LF) test is a modification of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test. It is used when the parameters of the hypothesized distribution are unknown and must be estimated from the sample data. The KS test is applicable when the parameters of the assumed distribution are fully specified; however, in many practical cases, the true parameters are unknown, requiring estimation from the sample itself. When the original KS test is applied in such cases, it can produce misleading results, as the probability of a Type I error may be underestimated compared to the standard KS test tables [52].

The Lilliefors test statistic (LF) is given by:

where is the Lilliefors test statistic, representing the maximum absolute difference between the empirical cumulative distribution function (ECDF) and the estimated cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the normal distribution, denotes the supremum (i.e., the largest absolute difference) between the two functions over all observed data points, is the estimated cumulative distribution function (CDF) of a normal distribution, computed using the sample mean () and sample standard deviation (), is the empirical cumulative distribution function (ECDF), constructed directly from the sample data.

2.5. Definition of the Classification Index Improvement Rate

As a result of the regression analysis between the classification index and the rated power, a linear equation was derived as follows:

where is the classification index, is slope of regression line, is the intercept of the regression line

is defined as the difference between the actual classification index of each model and the predicted value based on the linear regression.

where is actual classification index, is predicted value.

The equations for the mean and standard deviation of are as follows:

For 111 tractor models, the was calculated as −0.01875, and the standard deviation was 0.05381.

To evaluate the relative energy efficiency performance of each tractor model, the Z-score of the energy efficiency index () was calculated using the following equation.

where is the relative position of the energy efficiency index of each tractor model in the standard normal distribution, is the difference between the actual classification index and the regression based predicted value for each model, is the average of all values, is the standard deviation of the values.

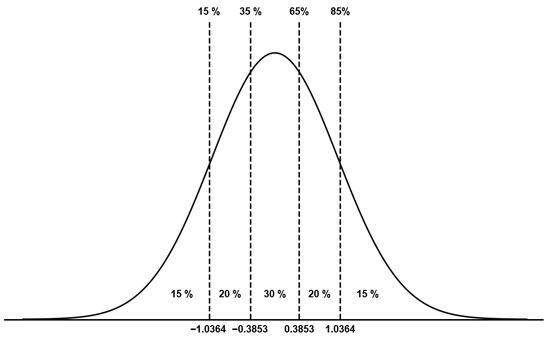

Figure 4 illustrates a normal distribution curve used to define the classification ranges of the energy efficiency index. The Z-scores of −1.0364, −0.3853, 0.3853, and 1.0364 divide the curve into five regions, each corresponding to a specific grade. Approximately 15% of the data falls below −1.0364 and above 1.0364 (1st and 5th grades), while 20% lies between each pair of adjacent Z-scores, and 30% lies near the mean (between −0.3853 and 0.3853), representing the 3rd grade.

Figure 4.

Five-Grade Classification Using Z-Scores and the Standard Normal Distribution.

This table presents the classification ranges of the energy efficiency index based on Z-scores. Each grade is defined by the calculated Z-score intervals, and the data is divided into five grades using the Z-score thresholds (±1.0364, ±0.3853). This method represents a grading system that reflects the relative distribution of energy performance. The corresponding Z-score–based grade boundaries are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Z-Score-Based Fuel Efficiency Grade Criteria for Agricultural Tractors.

To ensure the robustness of the grade classification thresholds, we examined potential outliers in the ΔEFi distribution using the standardized scores defined in Equation (14). Under the assumption of approximate normality, observations with were regarded as potential statistical outliers according to the three-sigma rule. In the present dataset, the values of ranged from −2.49 to 2.08, and no observations exceeded the threshold. Therefore, all 111 tractor models were retained for calculating and and for constructing the Z-score–based grade classification thresholds.

The Grading Upper Line Point (GULP) is defined by the following equation and is used to determine the threshold value for each grade level.

where A is the slope of the regression line, B is the intercept of the regression line, is the Grading Upper Line for grade , where , is the Z-score constant corresponding to each grade.

To compare the improvement in the grade index by horsepower between the previous and current studies, the following equation is used to define the Compare Energy Efficiency Index (CEFi):

where represents the difference in the grade index at horsepower p, indicating the degree of improvement in performance, is Grading Upper Line Point for grade I at horsepower p, based on tractor models produced from 2016 to 2020, is Grading Upper Line Point for grade i at horsepower p, based on tractor models produced from 2006 to 2010, is Horsepower values, consisting of 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100.

To quantitatively compare the improvement in energy efficiency based on horsepower, this study introduces the Energy Efficiency Index Advancement Rate (EFIAR), defined as:

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Correlation Between Rated PTO Power and Fuel Efficiency Classification Index

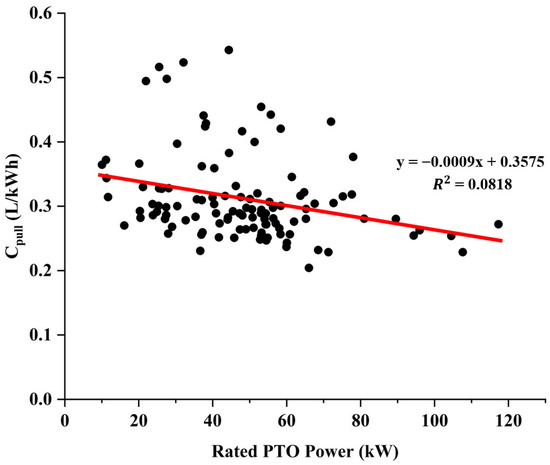

To classify tractors based on fuel efficiency, it is imperative to calculate the classification index values for the 111 tractor models tested from 2016 to 2020. The classification index of all tractors can be depicted as a function of Rated PTO power and the classification index, as shown in Figure 5. Within this graph, although the index values are dispersed, a discernible trend of declining classification index values with increasing Rated PTO power can be observed. This trend can be represented by a linear regression line, aggregating the mean of scattered index values, thereby delineating a linear relationship between the index values and Rated PTO power. Such an analytical approach enables a quantitative analysis of the correlation between index values and tractor PTO output, enhancing the comprehension of the relationship between observed index values and tractor PTO output. Consequently, as shown in Figure 5, an inverse correlation between the increase in Rated PTO Power and the decrease in classification index is evident. This indicates that an increase in Rated PTO output inversely affects the classification index, elucidating the variations in efficiency relative to output through this relationship.

Figure 5.

Relationship Between Rated PTO Power and Energy Consumption Efficiency Index ().

The coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.0818) obtained from the linear regression in Figure 5 indicates that the linear relationship is not strong. However, this should be interpreted as reflecting the heterogeneous nature of the dataset rather than the absence of any trend. The period from 2015 to 2020 corresponds to a transition phase in which tractors with conventional mechanical fuel-injection systems and those equipped with common-rail fuel-injection systems coexist, so that even within the same year a wide variety of models with markedly different engine performance and combustion-control technologies are included. As a result, the efficiency index exhibits large dispersion, and a low coefficient of determination is inevitable. Thus, the linear regression line in Figure 5 is not intended to provide precise predictions of the efficiency of individual tractor models, but rather to serve as an auxiliary tool for defining reference grading lines for each power class.

3.2. Normality Test and Nomal Distribution

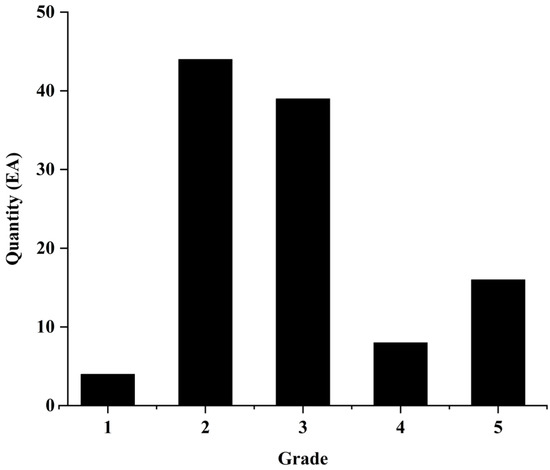

In this study, we conducted a grading process based on the energy classification of tractor models, which allowed us to observe the distribution of tractor models across different grades as depicted in Figure 6. In addition, the grade distribution by year is shown in Figure 7. Specifically, the number of tractor models classified according to their energy efficiency indicators was 4 for Grade 1, 44 for Grade 2, 39 for Grade 3, 8 for Grade 4, and 16 for Grade 5. This distribution was determined to be non-normal, suggesting an imbalance in the number of models across grades. The fact that the data distribution did not exhibit normality implies a failure to meet the prerequisite conditions for securing accuracy in statistical analysis.

Figure 6.

Grade Distribution Before Data Normalization.

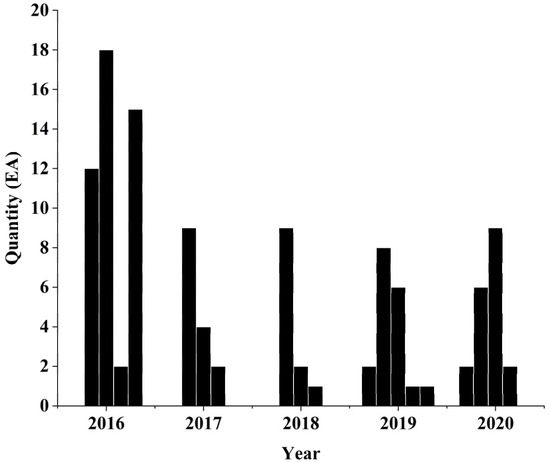

Figure 7.

Annual Distribution of Energy Efficiency Grades Before Data Transformation.

Therefore, this study adopted three different approaches to rigorously assess the normality of the data: the Shapiro–Wilk test, the Anderson–Darling test, and the Lilliefors test. These methods, based on distinct statistical foundations and theoretical underpinnings, played a fundamental role in evaluating the normality of the data, especially for a dataset with a high likelihood of non-normal distribution, including both positive and negative values. The application of multiple normality testing methodologies significantly enhanced the reliability of the statistical conclusions. When similar results were obtained across all testing methods, it provided confidence in the analysis outcomes, thereby strengthening the validity of the research. Furthermore, this approach added depth and accuracy to the data analysis process, contributing significantly to maximizing the reliability and validity of the research findings, thereby ensuring the precision of statistical inference and enhancing the validity of the research results. As indicated in Table 5, the Shapiro–Wilk test, a powerful method for determining whether sample data follows a normal distribution, yielded a very low p-value of for the original data. This significantly deviates from the standard normal distribution, strongly suggesting that the original data distribution does not satisfy normality. The Anderson–Darling test, sensitive to deviations in the tail regions, calculated a test statistic (T-S) of 5.7210, which, compared to the critical value (C-V) of 0.761, clearly indicates the data does not follow a normal distribution. Likewise, the Lilliefors test, an essential method for assessing data normality, supported this conclusion with a p-value of 0.000999. Following these initial analysis results, the Yeo–Johnson transformation process was implemented to improve the normality of the data, a versatile transformation method applicable to data containing both positive and negative values, known for its excellent capability to reduce asymmetry and enhance normality. This was considered an essential step towards enhancing the accuracy of statistical analysis. The retesting of the transformed data revealed a Shapiro–Wilk p-value of 0.11456, indicating a significantly higher likelihood of data normality. The Anderson–Darling test statistic (T-S) dropped to 0.5495, suggesting an improvement in data normality, while the Lilliefors test p-value of 0.2406 further confirmed this improvement. Therefore, the application of the Yeo–Johnson transformation markedly enhanced the normality of the dataset, which was crucial for systematically evaluating and improving data normality, playing a decisive role in boosting the precision and reliability of the analysis.

Table 5.

Comparison of p-values from Normality Tests for Original and Converted Data.

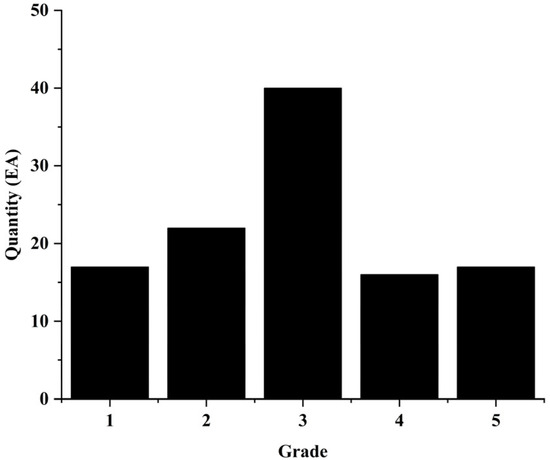

As shown in Figure 8, the classification results after applying the Yeo–Johnson transformation indicate a significant improvement in normality, with 17 models classified as Grade 1, 20 models as Grade 2, 40 models as Grade 3, 15 models as Grade 4, and 17 models as Grade 5. In addition, Figure 9 is included to illustrate the year-by-year grade distribution after applying the Yeo–Johnson transformation.

Figure 8.

Grade Distribution After Data Normalization.

Figure 9.

Annual Distribution of Energy Efficiency Grades After Data Transformation.

3.3. Comparison of Classification Index Improvement Rate

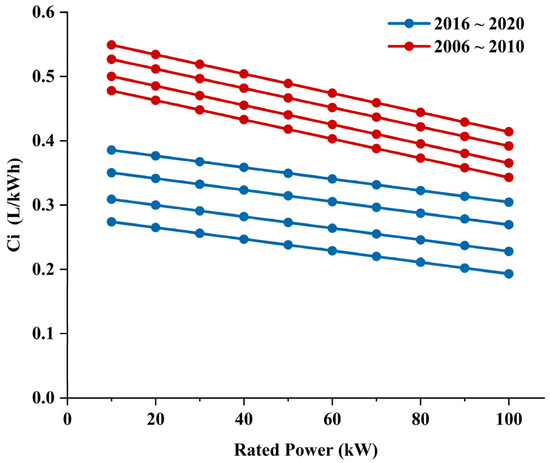

To assess the progress in energy consumption efficiency, this study conducted a comparative analysis between two tractor classification groups (Group 1: 2006–2010 and Group 2: 2016–2020). The classification indices were derived based on standardized test data and normalized using the Yeo–Johnson transformation to ensure statistical robustness.

As shown in Figure 10, the fuel consumption index (Ci, L/kW·h) of tractors in Group 2 (2016–2020) consistently exhibited lower values than those of Group 1 (2006–2010) across all rated power categories. This indicates that tractors manufactured between 2016 and 2020 achieved higher fuel efficiency compared to those produced between 2006 and 2010.

Figure 10.

Comparative Analysis of Tractor Fuel Efficiency Between 2006–2010 and 2016–2020 Across Rated Power Levels.

To quantitatively assess the degree of improvement, the upper thresholds of each classification grade by power category were compared between the two groups. The results revealed that the energy efficiency of agricultural tractors improved significantly, as shown in Table 6, with grade-level improvements ranging from approximately 20.57% to 54.86% depending on the rated power band.

Table 6.

Comparative Analysis of EFIAR Between 2006–2010 and 2016–2020 Across Rated Power Categories.

Additionally, the distribution ratio of supplied tractors by rated power category during the 2016–2020 period is presented in Table 7. According to the Agricultural Machinery Supply Status by Manufacturer and Specification published by the Korea Agricultural Machinery Industry Cooperative, tractors in the 50–60 ps range accounted for 23.78%, while those with over 100 ps accounted for 16.97%, representing the highest supply ratios.

Table 7.

Distribution ratio of supplied tractors by rated power category (2016~2020).

Overall, the energy consumption efficiency tended to increase as the rated power increased. This trend is particularly important given that medium- and large-sized tractors still account for a substantial share of the domestic agricultural market. These results suggest that technological advancements over the past decade have had the greatest impact on the main tractor models used in Korean agriculture. Since around 2017, high-horsepower tractor models have increasingly adopted common-rail fuel injection systems, which may partly explain why improvements in energy efficiency have been more pronounced in higher-power tractors.

4. Conclusions

This study quantitatively analyzed changes in the energy consumption efficiency of agricultural tractor models manufactured between 2006–2010 and 2016–2020. Energy consumption efficiency ratings were calculated for 111 tractor models based on standardized test data, and comparisons were conducted after ensuring data normality through the Yeo–Johnson transformation. The analysis showed that models produced between 2016 and 2020 exhibited improved fuel consumption efficiency across all power categories compared to those produced between 2006 and 2010, with improvement rates ranging from approximately 20.57% to a maximum of 54.86%. In particular, tractors with higher rated power tended to show greater improvements in energy consumption efficiency.

From the viewpoint of engine technology, these improvements are closely related to the evolution of diesel fuel-injection systems used in agricultural tractors. Earlier tractor models predominantly employed mechanically controlled in-line or rotary distributor injection pumps, which provided only a single main injection per cycle and offered limited flexibility in controlling injection timing and quantity. Subsequently, electronically assisted injection pumps were introduced, enabling more precise control of the start of injection and partial optimization of the combustion process. In the most recent generation of high-horsepower tractors, electronically controlled common-rail injection systems have become predominant. These systems supply high-pressure fuel to a common rail and use solenoid- or piezo-actuated injectors to perform multiple injections (pilot, main, and post injection) within one cycle, thereby improving mixture formation, shortening combustion duration, and reducing specific fuel consumption. Consequently, the higher improvement rates observed in the upper power categories in this study can be interpreted as the combined effect of this transition from mechanically controlled pumps to electronically controlled common-rail systems, together with other engine-side optimizations such as turbocharging and combustion calibration implemented to meet recent emission regulations.

These findings indicate that such technological advancements in agricultural tractors over the past decade have made a substantial contribution to enhancing energy consumption efficiency. However, this study applied statistical methods based on tractor usage hours in the Korean agricultural environment, and therefore, there are limitations in directly applying the results to agricultural conditions in other countries or regions. Additionally, various factors such as soil characteristics, terrain, and types of operations encountered in tractor use environments were not fully reflected. The energy consumption characteristics under actual operating conditions may differ from the results of this study, which should be addressed in future research. Further empirical studies that consider diverse operating environments and working conditions are needed. Moreover, it is necessary to expand energy consumption efficiency evaluations to next-generation agricultural machinery, including digital control technologies, autonomous driving functions, and electric and hybrid tractors, to contribute to the sustainable development of the agricultural sector and the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

This study has several limitations as it analyzed the energy efficiency of tractor models that were produced and distributed within Korea. First, there exists an imbalance in the number of samples across different years and models, which may have affected the representativeness of certain time periods. For instance, the number and types of tractor models included in the 2006–2010 and 2016–2020 groups differed, and such disparities in sample size could influence the interpretation of comparative results. Although the study minimized this issue by comparing five-year intervals, the selection of these time ranges may still affect the outcomes, which remains a limitation. Furthermore, the data used were confined to models released and operated in the Korean agricultural environment, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Because the results reflect Korea-specific operational conditions and tractor characteristics, they may not be directly comparable to energy efficiency trends in other countries or regions. Caution should be exercised in extrapolating the results to global trends, as fuel efficiency regulations and technology adoption rates differ across countries.

Second, the study relied solely on standardized test conditions, which may not fully capture the variability of real-world field operations. Tractor fuel efficiency can vary widely depending on working conditions such as terrain slope, soil resistance, crop type, and implement load. However, the energy efficiency indices in this study were derived from OECD-standardized test data, primarily reflecting performance under flat and idealized conditions. Therefore, the study did not account for field-specific factors such as muddy rice paddies, sloped terrain, or seasonal workload variations, which may lead to discrepancies between the reported results and the fuel efficiency experienced in practice. Additionally, since the analysis focused on efficiency changes driven by engine technology, other influencing factors were not considered. In real-world operation, fuel consumption is also affected by implement type and condition, tractor weight and drivetrain friction, tire inflation and traction, and operator behavior. Due to limitations in the current analytical framework, such variables could not be quantitatively controlled or reflected. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as improvements in engine and powertrain efficiency under equivalent test conditions. These limitations should be addressed in future studies by incorporating a broader range of variables and real-world operating scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-S.N. and C.-S.S.; methodology, J.-S.N. and C.-S.S.; software, J.-H.K. and W.-T.I.; validation, I.-S.H. and W.-T.I.; formal analysis, M.-K.J. and W.-T.I.; investigation, I.-S.H. and W.-T.I.; resources, T.-H.H. and Y.-T.K.; data curation, I.-S.H. and W.-T.I.; writing—original draft preparation, W.-T.I.; writing—review and editing, I.-S.H., W.-T.I. and C.-S.S.; visualization, I.-S.H.; supervision, C.-S.S. and Y.-K.K.; project administration, C.-S.S.; funding acquisition, C.-S.S. and Y.-K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out with the support of “Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science & Technology Development (RS-2023-00232116)”, Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea, and “Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science & Technology Development (RS-2025-02216071)”, Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Al-Ghussain, L. Global Warming: Review on Driving Forces and Mitigation. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2019, 38, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.; Chaudhry, S. Dealing with Climate Change: Concerns and Options. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2015, 4, 847–854. [Google Scholar]

- Zakari, A.; Khan, I.; Tan, D.; Alvarado, R.; Dagar, V. Energy Efficiency and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Energy 2022, 239, 122365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. International Energy Outlook 2019. U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/ieo/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Bilan, Y.; Streimikiene, D.; Vasylieva, T.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T.; Pavlyk, A. Linking between Renewable Energy, CO2 Emissions, and Economic Growth: Challenges for Candidates and Potential Candidates for the EU Membership. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Ahmed, K.; Ismail, M. Predictive Analysis of CO2 Emissions and the Role of Environmental Technology, Energy Use and Economic Output: Evidence from Emerging Economies. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2020, 13, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion 2018; IEA: Paris, France, 2018; ISBN 978-92-64-30678-3. ISSN 2219-9446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental and Energy Study Institute. Energy Efficiency. 2021. Available online: https://www.eesi.org/topics/energy-efficiency/description (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Climate Change: Atmospheric CO2. Available online: https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/carbon-dioxide/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 1997. Available online: https://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Copenhagen Accord. 2009. Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2009/cop15/eng/l07.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Paris Agreement. 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- United Nations Statistics Division; World Bank; International Energy Agency. Tracking SDG7: The Energy Progress Report 2020. Available online: https://trackingsdg7.esmap.org/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- International Energy Agency. Energy Efficiency 2021. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-efficiency-2021 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Türkoğlu, S.P.; Öztürk Kardoğan, P.S. The Role and Importance of Energy Efficiency for Sustainable Development of the Countries. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Sustainable Buildings Symposium (ISBS 2017), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 15–17 March 2017. In Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Fırat, S., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Europe 2020: A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth. 2010. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eu2020 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- European Commission. 2030 Climate & Energy Framework. 2014. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/climate-change/2030-climate-and-energy-framework/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Tsemekidi Tzeiranaki, S.; Bertoldi, P.; Castellazzi, L.; Gonzalez Torres, M.; Clementi, E.; Paci, D. Energy Consumption and Energy Efficiency Trends in the EU, 2000–2020; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaigalis, V.; Katinas, V. Analysis of the Renewable Energy Implementation and Prediction Prospects in Compliance with the EU Policy: A Case of Lithuania. Renew. Energy 2019, 151, 1016–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, X.; Yu, Y.; Wu, T.; Qi, Y. China’s Numerical Management System for Reducing National Energy Intensity. Energy Policy 2016, 94, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingali, P. Agricultural Mechanization: Adoption Patterns and Economic Impact. In Handbook of Agricultural Economics; Evenson, R., Pingali, P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 2779–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Liang, C.; Hamel, C.; Cutforth, H.; Wang, H. Strategies for Reducing the Carbon Footprint of Field Crops for Semiarid Areas: A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 31, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, N. An Energy Balance under a Conventional Crop Rotation System in Northern Japan: Perspectives on Fuel Ethanol Production from Sugar Beet. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 125, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C.S.; Park, J.G.; Kim, K.U. Classification Index and Grade Levels for Energy Efficiency Classification of Agricultural Dryers in Korea. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 39, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C.S.; Jang, J.H.; Kim, Y.T.; Kim, K.U. Classification Index and Grade Levels for Energy Efficiency Classification of Agricultural Heaters in Korea. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 38, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, H.D. Prediction of the Torque and Optimum Operating Point of Diesel Engines Using Engine Speed and Fuel Consumption. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1992, 53, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, H.D. Prediction of Tractor Engine Performance Using OECD Standard Test Data. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1992, 53, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisso, R.D.; Kocher, M.F.; Vaughan, D.H. Predicting Tractor Fuel Consumption. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2004, 20, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Sierra, J.; Ortiz-Cañavate, J.; Gil-Quirós, V.; Casanova-Kindelán, J. Energy Efficiency in Agricultural Tractors: A Methodology for Their Classification. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2007, 23, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türker, U.; Ergul, I.; Eroglu, M.C. Energy Efficiency Classification of Agricultural Tractors in Turkey Based on OECD Tests. Energy Educ. Sci. Technol. Part A Energy Sci. Res. 2012, 28, 917–924. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, C.S.; Kim, K.U.; Kim, K.W. Energy Efficiency Classification of Agricultural Tractors in Korea. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2012, 37, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C.; Kim, K.U. A Method for Fuel Efficiency Classification of Agricultural Tractors; ASABE Paper No. 131621100; ASABE: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.C.; Kim, K.U.; Kim, D.C. Prediction of Fuel Consumption of Agricultural Tractors. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2011, 27, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-S.; Kim, Y.-J.; Chung, S.-O.; Lee, D.-H.; Choi, C.-H.; Yoon, Y.-H. Development of Simulation Model for Fuel Efficiency of Agricultural Tractor. Korean J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 43, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocher, M.F.; Smith, B.J.; Hoy, R.M.; Woldstad, J.C.; Pitla, S. Fuel Consumption Models for Tractor Test Reports. Trans. ASABE 2017, 60, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monifar, H.; Khademolhosseini, F.; Raoufat, M.H.; Zareiforoush, H.; Alahdal, A.; Pishvaei, M.R. The Effect of the Tractor Driving System on Its Performance and Fuel Consumption. Inf. Process. Agric. 2020, 7, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolator, B.A. Modeling of Tractor Fuel Consumption. Energies 2021, 14, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, B.; Yang, W.; Chou, S.K. Fuel Injection Strategies for Performance Improvement and Emissions Reduction in Compression Ignition Engines—A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 28, 664–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TeKolste, J.; Walters, C.; McCullough, M.; Hamilton, L.; Nogueira, L.; Hoy, R.M. Diesel Tractor Fuel Efficiency and Exhaust Emissions Standards. Cornhusker Econ. Univ. Neb. Ext. 2023, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Shafaei, M.; Mahmoudi, A.; Ghamari, M.; Najafi, F. Scrutinization of overall energy efficiency of machinery in plowing process. Energy Equip. Syst. 2023, 11, 253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Bolotokov, A.; Gubzhokov, H.; Ashabokov, K.; Troyanovskaya, I.; Voinash, S.; Zagidullin, R.; Sabitov, L. Improving the fuel efficiency of an agricultural tractor diesel engine. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 411, 01045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, D. Research on energy-saving control of agricultural hybrid tractors integrating working condition prediction. Energy Rep. 2024, 10, 1334–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Fang, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; He, Q. Optimized fuzzy control energy management strategy for high-horsepower hybrid tractors considering working conditions adaptation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivekäs, K.; Komonen, A.; Vainio, M. Energy efficiency and carbon dioxide emissions of agricultural tractors using different powertrains. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz-Matey, I. Analyzing Tractor Productivity and Efficiency Evolution: A Methodological and Parametric Assessment of the Impact of Variations in Propulsion System Design. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rural Development Administration (RDA). Survey Report on the Use of Agricultural Machinery and the Mechanization Rate of Farm Work; Rural Development Administration: Jeonju, Republic of Korea, 2011.

- Rural Development Administration (RDA). Survey Report on the Use of Agricultural Machinery and the Mechanization Rate of Farm Work; Rural Development Administration: Jeonju, Republic of Korea, 2019.

- Yeo, I.-K.; Johnson, R.A. A New Family of Power Transformations to Improve Normality or Symmetry. Biometrika 2000, 87, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An Analysis of Variance Test for Normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royston, P. Approximating the Shapiro–Wilk W-test for non-normality. Stat. Comput. 1992, 2, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.W.; Darling, D.A. Asymptotic Theory of Certain ‘Goodness-of-Fit’ Criteria Based on Stochastic Processes. Ann. Math. Statist. 1952, 23, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilliefors, H.W. On the Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test for Normality with Mean and Variance Unknown. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1967, 62, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).