Abstract

To address the low segmentation accuracy and high computational complexity of classical deep learning algorithms—caused by the complex morphology of Northern Corn Leaf Blight (NCLB) and blurred boundaries between diseased and healthy leaf regions—this study proposes an improved lightweight segmentation model (termed MSA-UNet) based on the UNet architecture, specifically tailored for NCLB segmentation. In MSA-UNet, three core modules are integrated synergistically to balance efficiency and accuracy: (1) MobileNetV3 (a mobile-optimized convolutional network) replaces the original UNet encoder to reduce parameters while enhancing fine-grained feature extraction; (2) an Enhanced Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (E-ASPP) module is embedded in the bottleneck layer to capture multi-scale lesion features; and (3) the parameter-free Simple Attention Module (SimAM) is added to skip connections to strengthen focus on blurred lesion boundaries. Compared with the baseline UNet model, the proposed MSA-UNet achieves statistically significant performance improvements: mPA, mIoU, and F1-score increase by 3.59%, 5.32%, and 5.75%, respectively; moreover, it delivers substantial reductions in both computational complexity and parameter scale, with GFLOPs decreased by 394.50 G (an 87% reduction) and parameter count reduced by 16.71 M (a 67% reduction). These experimental results confirm that the proposed model markedly improves NCLB leaf lesion segmentation accuracy while retaining a lightweight architecture—rendering it better suited for practical agricultural applications that demand both efficiency and accuracy.

1. Introduction

Maize is highly susceptible to various diseases during its growth cycle, among which Northern Corn Leaf Blight (NCLB) is one of the most prevalent and destructive. NCLB compromises the photosynthetically active tissues of maize leaves upon infection, typically leading to yield reductions of approximately 20% and, in severe cases, losses exceeding 50%—resulting in substantial economic damage. Therefore, efficient and accurate segmentation of NCLB lesions, along with a reliable assessment of disease severity, is essential for early intervention, precision treatment, and accurate yield loss estimation. Traditional visual inspection methods, relying on manual assessment, are subjective and inconsistent. Field surveys are labor-intensive, time-consuming, and lack real-time feedback, while quantitative evaluation is often constrained by human measurement errors [1,2]. These limitations significantly hinder the timeliness and precision required for effective disease management in maize production [3].

With the continuous advancement of computer vision and artificial intelligence technologies, large-scale automated identification of plant diseases has become increasingly feasible. Compared to conventional techniques (e.g., manual inspection, threshold-based segmentation, or basic clustering), machine learning (ML) offers distinct advantages that address the core shortcomings of traditional methods. First, ML enables objective and consistent disease detection by eliminating human subjectivity—results are driven by data patterns rather than individual judgment, ensuring reproducibility across different scenarios. Second, ML methods automate feature extraction and classification, reducing the need for labor-intensive manual operations and enabling real-time processing of large-scale image datasets, which is impractical for traditional field surveys. Third, ML exhibits stronger robustness to environmental disturbances (e.g., variable lighting, leaf texture variations, or minor background noise) compared to conventional methods, which often rely on rigid parameter settings or idealized assumptions (e.g., uniform grayscale distribution) that fail in complex agricultural environments. Fourth, ML models can learn discriminative features from data automatically, avoiding the need for manual feature engineering (a major limitation of thresholding or clustering methods) and enhancing adaptability to diverse disease morphologies. These advantages make ML a powerful tool for overcoming the inefficiencies and inaccuracies of conventional plant disease detection techniques.

Current research on automated disease diagnosis generally falls into two categories: traditional machine learning approaches and deep learning-based methods.

Machine learning-based methods such as clustering methods [4], thresholding techniques [5], and Support-Vector Machines (SVM) [6] are commonly used to detect and classify crop diseases. Mishra et al. [7] proposed a method using clustering as an image segmentation method to differentiate between infected and uninfected portions of fruits. Four clustering techniques were used in the study: IS-KM, IS-FEKM, IS-MKM, and IS-FECA. The results showed that the IS-FECA based image segmentation method was able to more accurately separate the diseased portion of the fruit from the unaffected portion. Kumari et al. [8] proposed a systematic approach to identify leaf spot disease using image processing techniques. The system uses the K-mean clustering method to segment the image in the image segmentation stage and features are calculated from the clustered areas affected by the disease. All of the aforementioned traditional methods exhibit high sensitivity to parameter settings. For instance, the K-means clustering algorithm requires a predefined number of clusters, and its segmentation performance heavily depends on this manually set parameter. Similarly, threshold-based methods rely on the assumption of an ideal grayscale distribution, which limits their effectiveness in accurately segmenting irregular and multi-scale lesions on maize leaves.

In recent years, deep learning-based neural networks have been extensively applied in the field of image segmentation. Among these, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have shown remarkable effectiveness, particularly in tasks involving semantic segmentation and instance segmentation [9]. Polly et al. [10] presents an automated plant leaf damage detection and disease identification system. Experimental analyses using the Plant Village dataset show that the proposed method is very effective in detecting various defects in plants such as apple, tomato, and maize. Moazzam et al. [11] proposed a two-stage semantic segmentation architecture. In the first stage, a binary pixel-level classifier was developed to segment the background and vegetation. In the second stage, a three-class pixel-level classifier was designed to classify background, weeds, and tobacco. Cao et al. [12] proposed an enhanced UNet that combines a dual attention mechanism and Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling module for weed recognition. Gao et al. [13] developed a deep learning-based apple defect detection and quality grading system that integrates various advanced image processing techniques and machine learning algorithms to improve the automation and accuracy of apple quality monitoring. Jia et al. [14] proposed a persistent leaf disease image segmentation UNet based on the self-attention mechanism and deformable convolution, using UNet as the basic network, replacing the standard convolution in the downsampling stage of UNet with deformable convolution to extract richer features, and using the self-attention mechanism to learn the relationship between various features, so as to obtain more spatial and contextual information. Parul et al. [15] addressed the problem of degraded performance of deep learning models in automatic detection of plant diseases by using segmented image data to train convolutional neural network (CNN) models. Juliano P. Goncalves et al. [16] trained six convolutional neural network architectures for semantic segmentation of images to demonstrate necrotic lesions and/or yellowing induced by insect-infested coffee leaf miners in response to the poor performance of color-thresholded digital imaging methods under inhomogeneous illumination and background conditions, with FPN, UNet, and DeepLabv3+ (Xception) performing best at the pixel-level prediction for calculating percentage severity. Umme Fawzia Rahim et al. [17] proposed an innovative approach combining deep instance segmentation, data synthesis and color analysis for identifying and counting tomatoes at different growth stages. The study used synthetic dataset to train Mask R-CNN instance segmentation neural network to identify the growth stages of tomatoes and count them accordingly through the color threshold segmentation technique.

Current research on lesion segmentation primarily relies on deep learning techniques, employing advanced model architectures such as U-Net, Mask R-CNN, and Swin Transformer. However, in complex disease scenarios like Northern Corn Leaf Blight (NCLB), existing methods still face two major challenges: (1) Maize leaf lesions are often characterized by fuzzy boundaries, low contrast between diseased and healthy tissue, and highly variable morphology. These factors hinder effective feature extraction. Traditional semantic segmentation networks such as FPN and U-Net tend to lose fine-grained spatial information during deep convolutional operations, resulting in significant boundary segmentation errors and reduced accuracy; (2) Mainstream instance segmentation models, including transformer-based approaches and Mask R-CNN, suffer from high model complexity due to their multi-stage detection pipelines and mask generation modules. These models typically involve a large number of parameters and substantial computational overhead—for example, Mask R-CNN, with a ResNet-101 backbone contains approximately 46–48 million parameters—which hampers real-time performance and limits their practical applicability in agricultural production environments.

To address the above challenges, researchers have developed multiple U-Net variants by optimizing their structure, which provide valuable inspiration for our study. These modified models either enhance feature extraction capability or reduce computational complexity, achieving excellent performance in specific segmentation tasks. For instance, Yuan et al. [18] presented an improved AU-Net (DCAU-Net), which integrates deep and rich semantic information as well as shallow detail information, realizing adaptive and accurate segmentation of aneurysm images with large size differences in MRI angiography. Tian et al. [19] proposed a modified MSU-Net equipped with dilated convolution structure, squeeze-and-excitation (SE) block and spatial transformer layers, and experimental results proved its competitiveness in processing both normal and abnormal images. Additionally, Li et al. [20] proposed that multi-scale U-Net (MSU-Net) can concatenate fixed and moving images with multi-scale inputs or image pyramids, and subsequently merge these with corresponding layers of identical size within the U-Net architecture. Xu et al. [21] proposed LWMSDU-Net to solve the long training time of CNNs and low segmentation accuracy of the traditional U-Net for CDLIS (caused by leaf variations and complex backgrounds). It has encoding/decoding sub-networks and fuses features via residual connection, with fewer parameters and layers. These studies confirm that U-Net-based modified models can effectively solve segmentation problems in specific fields through targeted structural optimization.

Inspired by DCAU-Net, MSU-Net, and LWMSDU-Net, this study proposes a lightweight segmentation model for NCLB, referred to as MSA-UNet, which is based on an improved UNet architecture. MSA-UNet incorporates the lightweight MobileNetV3 backbone to significantly reduce the number of model parameters while enhancing the basic feature extraction capability by optimizing the downsampling process. To further improve the accuracy of lesion segmentation, the SimAM attention mechanism is introduced into the skip connections of the encoder–decoder structure. This module enhances the model’s focus on key regions associated with leaf lesion without increasing the parameter load, thereby effectively improving its generalization capability. In addition, an optimized ASPP module is integrated into the bottleneck layer to facilitate the hierarchical extraction of multi-scale lesion features. This is achieved by applying dilated convolutions with varying dilation rates, enabling simultaneous sampling at multiple spatial resolutions. The segmentation performance of the proposed MSA-UNet model is validated through comparative experiments with classical semantic segmentation models, including UNet, SegNet, PSPNet, and DeepLabV3+.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Maize Lesion S Dataset

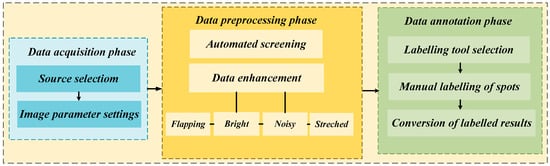

In this study, the characteristics of the NCLB lesion were selected as the primary research focus. The experimental data were sourced from two platforms: the open-source Plant Village database and the AI Studio platform. The construction process of the maize lesion dataset is illustrated in Figure 1, comprising three main phases: data acquisition, data preprocessing, and data annotation.

Figure 1.

The process of constructing a maize spot dataset.

In the data acquisition phase, although a large volume of maize disease-related images was available on open-source platforms, there was a lack of specialized datasets specifically focused on NCLB. To address this, we curated and screened image data exhibiting representative characteristics of NCLB from two platforms: AI Studio and the Plant Village open-source database. A total of 806 raw, unprocessed images of NCLB were selected as the foundation for subsequent dataset construction and analysis.

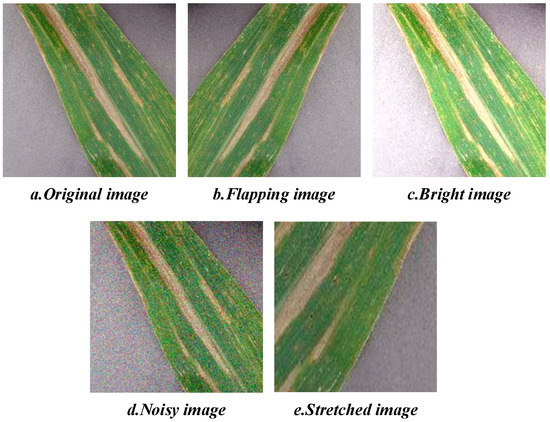

In the data preprocessing phase, OpenCV 4.10.0 was employed to automatically filter out blurred, low-resolution, or non-target images unrelated to leaf blight. As a result, an NCLB dataset comprising 358 RGB digital images with a resolution of 256 × 256 pixels was constructed. Following standard data partitioning practices, the dataset was divided into a training set (286 images) and a validation set (72 images) at an 8:2 ratio. The training set was used to optimize model parameters, while the validation set was used to evaluate generalization performance. To further improve the model’s learning capacity, robustness, and generalization ability, data augmentation techniques were applied to expand the training set. Specifically, the training set was increased to 1030 image samples through a combination of geometric transformations (e.g., flipping), color space adjustments (e.g., brightness enhancement and histogram stretching), and noise injection. The effect of the dataset augmentation is illustrated in Figure 2. The scale of our dataset is consistent with widely validated practices in crop disease leaf segmentation, as supported by numerous peer-reviewed studies across different crop species. These works confirm that small-to-medium-sized datasets—when paired with high-quality sampling, targeted augmentation, and precise annotation—can fully meet the requirements of deep learning model training for disease segmentation. Zou et al. [22] targeted three tobacco leaf diseases with complex lesion morphologies (small targets, blurred edges) similar to NCLB. It contained only 357 raw images—nearly identical to our 358 raw NCLB images. By covering different growth stages and natural environmental conditions, the dataset effectively supported disease segmentation model training. Our dataset, with almost the same raw scale and focus on a single disease, exhibits comparable or superior representativeness.

Figure 2.

Dataset augmentation effects.

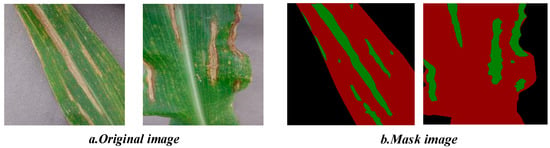

In the data annotation phase, manual semantic segmentation was performed using the LabelMe image annotation tool, in accordance with standard semantic segmentation labeling protocols. Specifically, lesion regions were annotated with green pixels, leaf regions with red pixels, and background areas with black pixels. The resulting annotations were subsequently converted into JSON-format mask maps for model training. An illustration of the dataset annotation outcomes is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Dataset labeling effects.

2.2. MSA-UNet Model

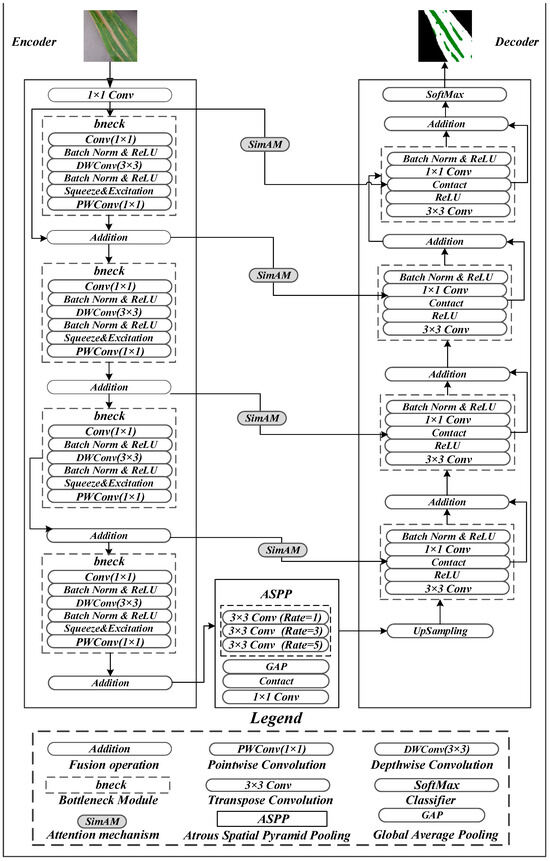

The improved UNet architecture proposed in this study, termed MSA-UNet, comprises three key components: (1) a lightweight encoder built upon MobileNetV3-derived bottleneck blocks (bneck), (2) a bottleneck layer integrated with an E-ASPP module for multi-scale feature fusion, and (3) encoder–decoder skip connections embedded with SimAM—a parameter-free attention mechanism. Retaining the classical encoder–decoder framework of the original UNet, MSA-UNet introduces targeted enhancements to address core challenges in NCLB segmentation, with its overall structure illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Network structure diagram of MSA-UNet.

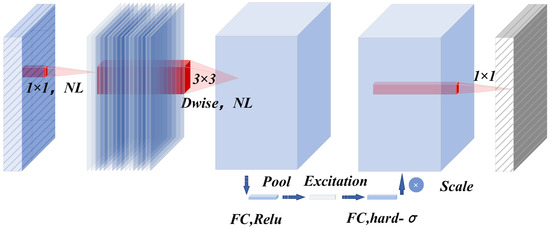

First, to resolve the redundant parameters and high computational complexity of the baseline UNet, the encoder adopts the bneck module from MobileNetV3 as its core building block. Leveraging depthwise separable convolutions, the bneck module drastically reduces redundant computations. Specifically, each bneck module sequentially performs channel expansion via 1 × 1 convolution, spatial feature extraction via 3 × 3 depthwise convolution (with channel-wise weights dynamically optimized by the squeeze-and-excitation (SE) attention mechanism), and channel dimension restoration via 1 × 1 pointwise convolution, followed by residual fusion with the input feature map.

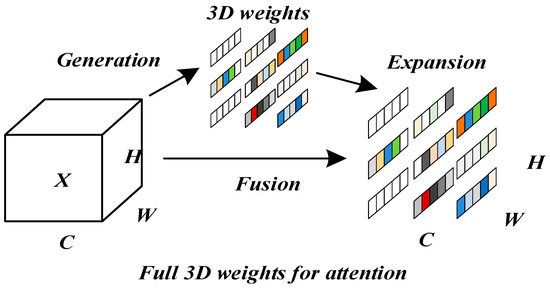

Second, NCLB lesions are often surrounded by yellow-brown halos and exhibit low color contrast, leading to ambiguous boundaries. The baseline UNet’s strided convolutions in the encoder gradually reduce feature resolution to improve computational efficiency, but this exacerbates detail loss in boundary regions—particularly for early-stage lesions or weak-texture areas. To mitigate this, SimAM is embedded in the encoder–decoder skip connections: by generating 3D attention weights (jointly modeling channel, height, and width dimensions), SimAM focuses on key boundary regions (e.g., the transition zone between yellow-brown halos and healthy tissues) to enhance extraction of low-contrast boundary features. Notably, this module improves the continuity and segmentation accuracy of fine-grained lesions without adding any model parameters.

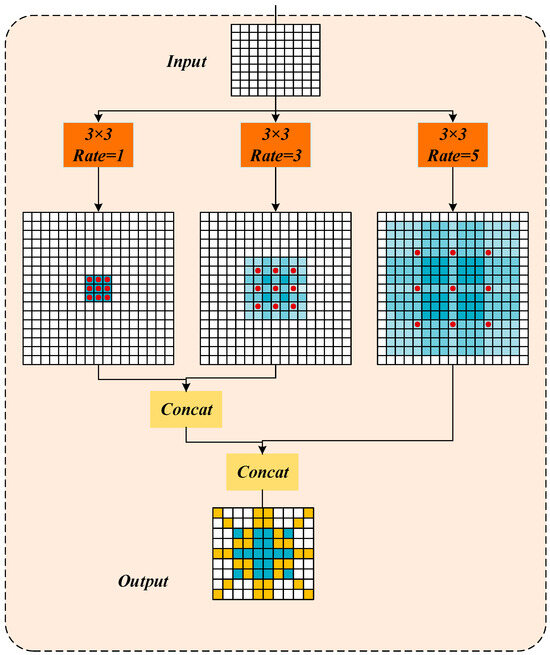

Third, NCLB segmentation involves coexisting multi-scale lesions, which often cause over-segmentation, under-segmentation, or broken boundaries in traditional methods limited by single-scale feature extraction. To address this, the E-ASPP module is integrated into the bottleneck between downsampling and upsampling stages. Distinguished from the standard ASPP, the enhanced version employs parallel 3 × 3 atrous convolutions with optimized dilation rates ([1, 3, 5]) to capture features across multiple receptive fields (3 × 3, 7 × 7, 11 × 11), while incorporating Global Average Pooling (GAP) to enhance global semantic representation. The multi-scale feature maps are concatenated and compressed via 1 × 1 convolution for dimensionality reduction, establishing cross-scale feature interactions that effectively alleviate errors caused by lesion size variations and improve segmentation accuracy.

The decoder implements a multi-level upsampling and feature enhancement mechanism: it first restores spatial resolution via 3 × 3 transpose convolution, followed by ReLU activation to strengthen nonlinear representation. Within the skip connections, encoder features are dynamically weighted by SimAM to enhance spatial alignment between cross-layer features; the weighted encoder features are then concatenated with decoder features along the channel dimension, fused via 1 × 1 convolution, and regularized by a Batch Normalization (BN) layer with ReLU activation. Through four iterations of this upsampling and fusion process, the model progressively reconstructs the original input image dimensions, and final segmentation results are generated via a softmax activation function.

2.2.1. Lightweight Encoders Based on Bneck

The core objective of introducing the bneck module into the MSA-UNet network is to achieve model lightweighting through structural optimization, with depthwise separable convolution serving as the key to this lightweight design. MobileNetV3 outperforms lightweight backbones as the backbone for NCLB detection via targeted optimizations: compared to MobileNetV2, its NAS-optimized structure, h-Swish activation, and integrated SE attention module better capture NCLB’s complex morphology and distinguish blurred lesion boundaries.

Depthwise separable convolution is a key factor in achieving the lightweight design of MSA-UNet. This operation decomposes the standard convolution into two sequential steps. First, a depthwise convolution is applied, where each input channel is processed independently using a convolutional kernel to extract spatial features such as edges and textures of lesion, thereby reducing cross-channel computations. Subsequently, a pointwise convolution is performed to integrate channel information. Notably, both the computational complexity and parameter count of this approach are significantly lower than those of a traditional convolution, as illustrated in Figure 5. Specifically, it first employs a 1 × 1 convolution to expand the channel dimension, thereby enhancing feature representation capability. This is followed by a depthwise separable convolution, which consists of a depthwise convolution and a pointwise convolution [23,24], enabling spatial feature extraction while significantly reducing computational complexity.

Figure 5.

Working principle of bneck structure.

Compared to traditional convolution, this approach substantially reduces both computational complexity and the number of parameters. Specifically, the computational cost of traditional convolution is expressed in Equation (1), and its number of parameters is given in Equation (2). Correspondingly, the computational cost and parameter count of depthwise separable convolution are presented in Equations (3) and (4), respectively. Where and represent the input feature map, and are the number of output channels, is the convolution kernel.

When analyzing the differences between depthwise separable convolution and traditional convolution, the efficiency advantages can be visually quantified by calculating the computational and parametric ratios of the two. The ratio of depthwise separable convolution to ordinary traditional computation is shown in Equation (5). The ratio of depthwise separable convolution to an ordinary convolution parametric quantity is shown in Equation (6).

By comparing the two convolution calculation processes of Equations (5) and (6), it can be seen that for both the number of parameters and the amount of computation, the depthwise separable convolution is only times the traditional convolution. This greatly reduces the computational burden of the model, thus effectively realizing the lightweight design of the MSA-UNet network.

The bneck module includes not only a depthwise separable convolution, but also incorporates the SE module [25] and the inverted residual structure; it dynamically enhances the feature response of important channels by obtaining channel weights through Global Average Pooling. Finally, based on the activation function Swish [26], the h-Swish activation function [27] is used, which retains the lightweight property and enhances the critical features through the attention mechanism, finally achieving an optimal balance between accuracy and speed.

2.2.2. Integration of an Improved ASPP Bottleneck Layer for Multi-Scale Feature Fusion

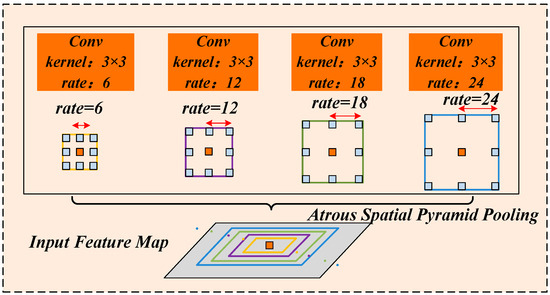

Morphological complexities, such as the coexistence of multi-scale lesions—ranging from large spreading lesions to tiny initial spots—are commonly observed in maize leaf lesion segmentation. Traditional clustering methods often suffer from over-segmentation or under-segmentation of such multi-scale targets, as well as edge fragmentation issues. These limitations arise primarily due to the reliance on a preset number of clusters and the focus on single-scale feature extraction capabilities. Therefore, this study introduces an improved multi-scale ASPP module [28] at the bottleneck layer at the end of the encoder. The architecture of the ASPP module is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Structure of Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling.

ASPP employs atrous convolutions with varying dilation rates for simultaneous multi-scale feature sampling. As illustrated in Figure 6, four parallel atrous convolutional layers are used, each with a kernel size of 3 × 3 but different dilation rates of 6, 12, 18, and 24. These varying dilation rates correspond to different receptive field sizes, enabling the expansion of the receptive field without increasing computational complexity. represents the dilation rate of the atrous convolution, for the convolution kernel size and the dilation rate , the receptive filed size formula is as follows:

Among them, the size of the receptive field plays a crucial role in feature extraction: larger receptive fields are more effective for capturing global contextual information, whereas smaller receptive fields better capture local details. In the context of NCLB segmentation, lesions often cluster in localized regions within an image. Excessively large dilation rates may cause the receptive field to extend beyond the actual lesion area, inadvertently including irrelevant background information and thereby reducing segmentation accuracy. To address the multi-scale nature of maize leaf lesion, this study optimizes the ASPP module by selecting medium dilation rates tailored to capture semantic features of small, medium, and large lesions. Specifically, the atrous convolution dilation rates are set to [1, 3, 5]. As depicted in Figure 7, the improved ASPP module employs three parallel atrous convolution layers with 3 × 3 kernels, corresponding to effective receptive fields of 3 × 3, 7 × 7, and 11 × 11, respectively. This multi-scale design comprehensively adapts to the morphological variations in lesions at different developmental stages.

Figure 7.

Medium multi-scale dilated convolution.

2.2.3. Jump Connection Pathways Embedded in the Parameter-Free Attention Mechanism SimAM

In the task of image segmentation of a maize leaf lesion, in addition to the problem of complex morphology in the segmentation of a maize leaf lesion, there are also problems such as blurred boundaries and low contrast between the lesion areas and healthy tissues and backgrounds, which make it difficult to accurately locate the lesion areas in the traditional segmentation model. Current attention-based improvement methods addressing these issues exhibit certain limitations. One-dimensional channel attention mechanisms (such as ECA [29]) capture channel dependencies via Global Average Pooling and spatial dimension compression, effectively enhancing key feature channels but neglecting spatial saliency information. Two-dimensional attention mechanisms (such as CBAM [30]) sequentially apply channel and spatial attention to realize two-dimensional feature enhancement; however, the independent weighting operations for channel and spatial dimensions hinder the collaborative optimization of features across all three dimensions—channel, height, and width. Furthermore, conventional three-dimensional attention mechanisms often rely on manually designed complex computational structures, resulting in high parameter counts and low computational efficiency, which severely limits their applicability in lightweight model deployment.

To address the above problems, this paper introduces the SimAM parameter-free attention module [31] in encoder–decoder skip connections, as shown in Figure 8. When calculating attention, SimAM not only pays attention to the characteristics of the channel dimension (), but also fully considers the characteristics of the spatial dimension ( and ), and realizes the fusion of multi-dimensional features.

Figure 8.

Full 3D attention mechanism.

SimAM attention is paid by defining the minimum energy function, which evaluates the importance of each position by measuring the linear separability between neurons. Specifically, the minimum energy function formula in SimAM is as follows:

Among them, and represent the height and width of the input feature map, is the number of neurons on each channel, represents the input feature map, represents the target neuron of the minimum energy, and represent the mean and variance of the neurons on a single channel, represents the regular term, and represents the minimum energy of the target neuron. indicates the importance of each neuron. The formula for the output characteristics of SimAM is as follows:

where the and tables represent the input and output feature maps, represents the dot product operation, and the Sigmoid activation function converts the value of into an attention weight between [0, 1]. Finally, the input feature map is multiplied by the weight of each neuron to obtain the final output feature map.

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Environment Configuration

To ensure experimental consistency and eliminate bias, all experiments in this study were conducted under identical hardware and software environments. The detailed specifications of the experimental setup, including hardware components and software configurations, are systematically summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental environment configuration.

3.2. Training Settings

The initial learning rate for the experiments in this paper is set to 0.0001, the iteration round epoch is set to 200, the experiments use the adaptive moment estimation (Adam) optimization algorithm, the learning rate decreases by cosine descent, and the momentum is set to 0.9.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

In this paper, we use Mean Pixel Accuracy (mPA), Mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), and F1-score to evaluate the segmentation accuracy of the model, and the number of parameters, Params, and the number of Giga Floating-point Operations Per Second, GFLOPs [28], to evaluate the computational complexity and the number of parameters of the model. The formulas for each evaluation metric are shown below:

In the above, (true positives) refers to the number of pixels correctly predicted as belonging to the lesion region; (true negatives) denotes the number of pixels correctly classified as background; (false positives) represents the number of background pixels incorrectly predicted as lesion; and (false negatives) indicates the number of lesion pixels incorrectly classified as background. Here, denotes the number of categories, and includes the addition of the background class.

3.4. Comparison of Different Segmentation Models

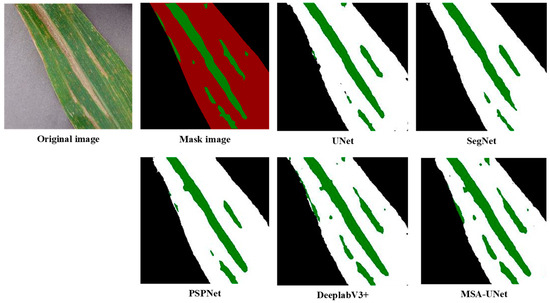

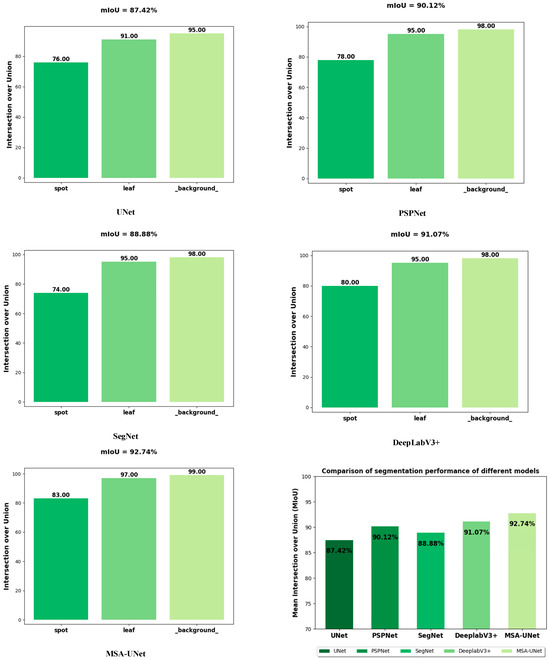

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed MSA-UNet model, this study compares the segmentation performance of several models for NCLB under consistent experimental conditions. The models included in the experiments are UNet, PSPNet, SegNet, DeepLabV3, and MSA-UNet. The comparative results are presented in Table 2 as well as in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Table 2.

Comparison of different segmentation models.

Figure 9.

Segmentation effect of different models.

Figure 10.

Comparison of segmentation performance of different models.

Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of five segmentation models: UNet, PSPNet, SegNet, DeepLabV3+, and the proposed MSA-UNet. All reported metrics (mPA, mIoU, F1-score, Params, GFLOPs) are average values obtained from three independent repeated experiments—conducted under identical hardware/software environments to avoid single-run bias—ensuring the statistical reliability of the results. This experimental design minimizes random fluctuations directly confirming the stability of the observed performance trends.

The experimental results demonstrate that MSA-UNet achieves a lightweight design with only 8.18 M parameters and 57.81 GFLOPs, while delivering the best overall segmentation performance. Specifically, MSA-UNet attains an mIoU of 92.74%, mPA of 95.42%, and F1-score of 91.95%, significantly outperforming the other models. Notably, this performance gain is not accidental but stems from the systematic optimization of the model structure—consistent with the findings of our ablation experiment, as shown in the subsequent ablation experiments: replacing the baseline UNet’s encoder with MobileNetV3 reduces parameters by 67% while maintaining accuracy; introducing the SimAM attention mechanism further boosts mIoU by 4.29%; and integrating the enhanced ASPP module ultimately achieves the total mIoU gain of 5.32%. This stepwise, incremental improvement (rather than erratic fluctuations) confirms that the performance advantages of MSA-UNet are driven by its structural design, not random variation.

For the critical lesion segmentation task, MSA-UNet achieves an IoU of 83%, representing a 7% improvement over the baseline UNet which reaches 76%, a 3% improvement over DeepLabV3+ which reaches 80%, and a 9% improvement over SegNet which reaches 74%. Such substantial and consistent gaps across multiple comparative models further validate the reliability of MSA-UNet’s performance enhancements. Although DeepLabV3+ achieves a relatively high mIoU of 91.07%, it incurs the highest computational cost of 167 GFLOPs and parameter count of 54.71 M, highlighting the imbalance between accuracy and efficiency in existing models. In contrast, PSPNet and SegNet exhibit moderate accuracy and efficiency, while the baseline UNet—with an mIoU of 87.42%—reflects inherent limitations in handling complex NCLB segmentation scenarios.

Figure 9 illustrates the segmentation results obtained by different models. It can be observed that the reference models UNet, SegNet, and PSPNet accurately segment leaf contours but exhibit limited capability in extracting lesions, with lesion segmentation accuracy below 80%. In contrast, DeepLabV3+ and MSA-UNet maintain stable performance in leaf contour segmentation and demonstrate clear advantages in lesion extraction. DeepLabV3+ provides relatively precise delineation of lesion boundaries and achieves slightly better segmentation results than the baseline UNet model. Notably, MSA-UNet outperforms all other models, with lesion segmentation accuracy exceeding 80%, effectively capturing the lesion regions with higher fidelity.

Figure 10 depicts the segmentation performance of different models for maize leaf, spot, and background, and it can be seen that there is a significant difference in the overall performance of each model in the maize leaf lesion segmentation task. Among them, MSA-UNet performed best with 92.74 mIoU, while UNet performed weakest with 87.42 mIoU. In terms of specific category segmentation, MSA-Net achieved 0.83 IoU for the lesion category, which was significantly better than UNet’s 0.76, indicating that it has obvious advantages in lesion segmentation tasks. However, the IoU of each model for the leaf category is maintained in a high level range of 0.93–0.97, indicating that different models have close segmentation capabilities for leaves and perform well. For background categories, the IoU of all models approached or exceeded 0.98, demonstrating excellent background segmentation capabilities.

These results demonstrate that MSA-UNet not only achieves the best overall segmentation performance but also exhibits significant advantages in accurately identifying key lesions. In contrast, the compared models perform relatively similarly in segmenting leaf and background regions.

3.5. Performance Comparison of Different Modules

3.5.1. Comparison of Different Attention Modules

In order to verify the effectiveness of SimAM attention mechanism for NCLB spot segmentation. In this paper, segmentation models with different latitude attention mechanisms were set up based on the UNet model in the experiment, including the SE module, CBAM module, and SimAM module, and the results are shown in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Comparison of the performance of different attention modules.

The experimental results in Table 3 show that all attention modules significantly improve segmentation performance, with mPA increasing by 1.05–2.43%, mIoU increasing by 2.43–4.29%, and F1 increasing by 1.8–4.54%, confirming that the introduction of attention mechanism can enhance the focusing ability of the model on low-contrast lesion features. Among them, the SimAM module, which is modeled by space and channel dimensions, can achieve the most significant segmentation accuracy without increasing network parameters through the parameter-free 3D energy function. Its mIoU, mPA, and F1 are improved by 2.43%, 4.29%, and 4.54%, respectively, compared with the reference UNet model, which shows that the introduction of the SimAM module at jump connections proposed in this paper can more effectively capture the local context letters of the lesion edge, where the balance between accuracy and efficiency is the best.

3.5.2. Comparison of Different Dilation Rates

In order to determine the effectiveness of ASPP with optimal dilation rate, the performance of the model is verified in the experiments by setting up three sets of different gradient of dilation rates to verify the performance of the model. The dilation rates set in the experiment are [1, 2, 3], [1, 6, 12], and [1, 3, 5], and the experimental results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of different dilation rates.

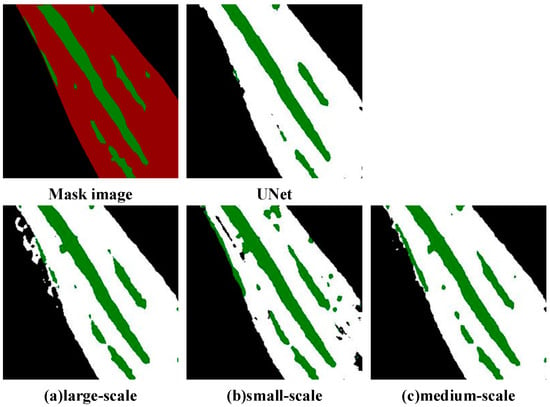

The experimental results in Table 4 show that when the combination of the dilation rate is [1, 3, 5], which is the medium-scale atrous convolution, the mPA, mIoU, and F1 of the model are 93.69%, 90.76%, and 90.35%, respectively, and the values of the experimental results are optimal, which indicates that it is optimally adapted to the morphology of the morphological characteristics of the maize leaf spots. As further verified in Figure 11, which visualizes the segmentation results under different dilation rate combinations.

Figure 11.

Segmentation effect of different dilation rates.

Figure 11 visualizes the segmentation results of Northern Corn Leaf Blight (NCLB) lesions under different atrous convolution dilation rate combinations. The “Mask image” serves as the ground-truth reference, with green regions indicating true lesion areas, while the UNet result acts as the baseline: the baseline UNet can roughly identify major lesion regions but fails to capture fine-grained details, exhibiting discontinuous lesion edges and slight deviations from the ground-truth boundaries—consistent with its relatively lower quantitative metrics in prior experiments.

We analyze the three dilation rate combinations: the large-scale dilation group uses the [1, 6, 12] combination, and its result in Panel A introduces noticeable background interference in the form of unnecessary predicted lesion regions. This issue arises from an excessively large receptive field, leading to over-segmentation. The small-scale dilation group uses the [1, 2, 3] combination, and its result in Panel B cannot fully cover large, continuous NCLB lesions due to a limited receptive field, resulting in fragmented segmentation (known as under-segmentation). In contrast, the medium-scale dilation group uses the [1, 3, 5] combination, and its result in Panel C is most aligned with the ground-truth mask: lesion edges are clear, continuous lesion regions are fully preserved, and there is no significant over-segmentation or under-segmentation.

This is because NCLB spots usually present a local aggregated distribution, and medium-scale atrous convolution can effectively balance the local details with the neighborhood context information, avoiding the feature fragmentation caused by too small receptive fields while effectively avoiding the feature dilation problem caused by large-scale dilation rates of [1, 6, 12]. The performance of the dilation rate [1, 2, 3] group was suboptimal, with an mPA of 93.37% and mIoU of 90.54%, mainly because of the insufficient expression power of small-scale combinations for multi-scale features. While maize spots have significant multi-scale characteristics such as an early spot diameter less than 2 mm and late expansion to more than 5 mm, a single small-scale atrous convolution struggles to cover the morphological changes in the developmental stages of the spots, resulting in limited ability to model the global context of late spots. Therefore, in this paper, the model is optimized using medium-scale atrous convolution (rate = [1, 3, 5]) to obtain the best segmentation performance.

3.5.3. Comparison of Different Optimizers

In order to determine the effectiveness of the best optimizer for UNet feature learning, this paper sets up a comparative experimental group of SGD (Stochastic Gradient Descent) and Adam (adaptive moment estimation) introduced into the UNet architecture before and after the improvement, aiming to compare the gradient updating mechanism through the differentiation analysis of the effects of different optimizers on the model segmentation performance, the results are shown in Table 5 below.

Table 5.

Performance comparison of different optimizers.

The experimental results in Table 5 show that under the basic UNet architecture, the mPA, mIoU, and F1 values of SGD (Experiment 1) are 90.51, 87.14, and 83.70, respectively, and the mPA, mIoU, and F1 values of Adam (Experiment 2) are 91.83, 87.42, and 86.20, respectively. The experiment shows that Adam is better than SGD on the original UNet, and the F1-score is significantly improved by 2.5; it is shown that Adam can better adapt to complex feature learning, and its adaptive learning rate mechanism can effectively alleviate the problem of gradient sparsity.

The mPA, mIoU, and F1 values of SGD (Experiment 3) under the improved UNet architecture are 94.33%, 90.85%, and 90.52%, respectively, and the mPA, mIoU, and F1 values of Adam (Experiment 4) are 95.42%, 92.74%, and 91.95%, respectively, which indicates that Adam still maintains the advantage in the improved UNet, but because the improved model structure itself solves part of the optimization problem, so the performance gap is narrowed and F1 is only improved by 1.43%, but Adam’s momentum adaptive property still has a gain on convergence.

3.6. Ablation Experiment

In order to verify the effect of different module combinations on the model segmentation performance, this paper conducted ablation experiments on the MSA-UNet model by the control variable method, and the results of the experiments are shown in the following table, with the optimal values bolded in the table. Under the premise that the experimental data and parameters are consistent, a total of six groups of ablation experiments were conducted in the experiment. The experimental results are shown in Table 6 below.

Table 6.

Results of ablation experiments.

The experimental results in Table 6 show that group (1) represents the benchmark UNet network without joining any module. In group (2), only the backbone network is replaced by the network model of MobileNetV3, although the values of mPA, mIoU, and F1 are only slightly improved, the value of model parameter Params decreases from 24.89 M to 7.78 M, and the value of computational complexity GFLOPs decreases from 452.31 G to 56.81 G, which is attributed to the fact that model pruning and compression techniques are used in the training process of MobileNetV3 to greatly reduce redundant connections and parameters through depthwise separable convolution, which makes MobileNetV3, as the backbone network, greatly reduce the number of parameters and computation. This significant reduction in parameters and computational complexity essentially reflects the core optimization logic of model lightweighting. Parameter count and GFLOPS are the core evaluation dimensions of lightweighting, and their collaborative compression directly determines the model’s adaptability to resource-constrained scenarios. Reduced parameter count is the basis of lightweighting, which can directly reduce memory occupation and avoid memory overflow when deployed on low-memory devices such as embedded industrial computers. Decreased GFLOPS reflects the optimization of computational complexity, which can reduce the computing power consumption and heat generation of devices, avoiding operation lag caused by insufficient computing power. The two are synergistically optimized through designs such as MobileNetV3’s depthwise separable convolution, forming the core technical support for the model to adapt to resource-constrained scenarios. In group (3), ASPP is added only at the bottleneck of UNet, and atrous convolutions with sampling rates of 1, 3, and 5 are used to enhance the semantic understanding and segmentation accuracy of the network for objects of different sizes by expanding the receptor’s convolution and capturing multi-scale contextual information, so that the accuracy indexes grow as follows: mPA value grows by 1.86%, mIoU value grows by 3.34%, and the F1 value is improved by 4.15%. At the same time, it also avoids increasing too much computational complexity, which is only increased to 471.43 G, and the number of parameters is also slightly increased to 25.03 M. In group (4), the SimAM module is introduced only at the jump connection of the U-Net network, and SimAM enhances the feature fusion and detail capturing through spatial and channel weighting at the jump connection of UNet, so that the model pays more attention to the key features, and thus effectively improves the segmentation accuracy. The accuracy index mPA value increases by 2.43%, mIoU value increases by 4.29%, F1 value increases by 4.54%, and the computational complexity increases to 463.11 G. The number of parameters is still 24.89 M because the SimAM attention mechanism is parameter-free by calculating weights based on the local self-similarity, optimizing the solution of the energy function, and avoiding over-parametrization. In group (5), replacing the backbone network MobileNetV3 and adding the SimAM module resulted in an increase of 2.87% in the value of the accuracy metric mPA, an increase of 4.90 percentage points in the value of mIoU, an increase of 5.12 percentage points in the value of F1, a decrease in computational complexity by 395.41 G, and a decrease in the number of model parameters by 17.11 M. In group (6) is the improved MSA-UNet algorithm, the experiments show that compared with the base model UNet, the values of mPA, mIoU, and F1 of the improved MSA-UNet model are improved by 3.59%, 5.32%, and 5.75%, respectively, and the computational complexity of the GFLOPs decreases by 394.50 G and the number of parameters decreases by 16.71 M. It can be seen that this paper has a significant advantage in improving segmentation accuracy as well as the computational efficiency. The algorithm in this paper has a significant advantage in terms of computational efficiency while improving the segmentation accuracy.

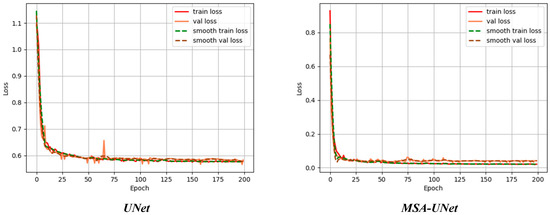

3.7. Loss Function

In order to verify the model convergence and measure the model generalization ability, this paper monitors the trend of the loss function on the training set and validation set during the training process, and the experimental results are shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Comparison of loss values before and after the advance.

Figure 12 shows the change in error of the algorithm before and after the improvement for training and testing on the dataset, Train loss denotes the loss value of the training set and Val loss denotes the loss value of the testing set. When Train loss decreases, Val loss decreases, indicating that training is normal; when Train loss decreases, Val loss is stable, indicating that the network is overfitting; when Train loss is stable, Val loss decreases, indicating that there is a problem with the dataset; when Train loss is stable, Val loss is stable, indicating that it is necessary to reduce the learning rate or Batch parameters; and when Train loss rises, Val loss rises, indicating that the training hyperparameters are not set properly. The training set loss of the base model UNet, Train loss, with a high initial value, decreases rapidly as the number of training rounds increases, dropping to about 0.6 at about 25 rounds, after which the decreasing trend slows down, and is maintained at about 0.55 at 200 rounds; the validation set loss, Val loss, has a similar decreasing trend as that of the training set, but has slightly larger fluctuations after 25 rounds, and eventually stabilizes slightly higher than the training set loss level of about 0.58. The small loss difference between the training and validation sets indicates that the model does not have an overfitting problem, but the relatively high loss values indicate that there is room for improvement in the model performance. The loss values of the training and validation sets of the MSA-UNet model decrease extremely fast, dropping below 0.1 at around 25 rounds, and then leveling off and remaining around 0.05. Compared with the base model UNet, the loss of both training and validation sets of the MSA-UNet model is significantly reduced, while the loss values remain close, which indicates that the MSA-UNet model has enhanced learning ability and better generalization ability.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, the MSA-UNet model based on improved UNet is proposed to address the problems of complex morphology, low segmentation accuracy caused by blurred boundaries between diseased and non-diseased spots, and a large number of model parameters in NCLB images. The method effectively improves the feature extraction capability and computational efficiency of the model by replacing the coding part of the benchmark UNet with a lightweight MobileNetV3 network, introducing the SimAM attention mechanism in the jump connection, and integrating the ASPP module in the bottleneck layer. In this paper, based on NCLB segmentation data, experimental validation was carried out, and UNet, SegNet, PSPNet, and DeeplabV3+ were selected as comparative models for performance validation. The results show that the mIoU, mPA, and F1 values of the MSA-UNet model are 92.74%, 95.42%, and 91.95%, respectively, which are significantly better than the comparison model, and the model achieves lightweight deployment while maintaining high accuracy, with a parameter count of only 8.18 M, and the computational complexity is controlled at 57.81 GFLOPs, which verifies the validity of the proposed method.

The method proposed in this paper can achieve accurate segmentation of maize leaf spots, which provides reliable technical support for the deployment of lightweight segmentation equipment and the grading of disease degree. The current model has achieved good results in single-leaf spot recognition, but the segmentation accuracy is still deficient when dealing with heavily curled leaves.

In future work, we will further expand the maize leaf image database covering different fertility periods and multiple species, focus on collecting samples of multi-disease complex infections, and improving the robustness of the model to disturbances such as complex light and leaf shading in the field through optimized algorithms, in order to promote the application of accurate disease monitoring in field environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: C.M., C.W. and X.G.; Software: C.M., X.C., R.W., G.X. and Y.L.; Validation: C.M., C.W. and X.G.; Investigation: C.M., G.X. and Y.L.; Data curation: C.M., X.C., R.W., G.X. and Y.L.; Project administration: C.M., X.C. and R.W.; Writing—original draft preparation: C.M., C.W. and X.G.; Writing—review and editing: S.Z. and Z.W.; Resources: Z.W.; Supervision: S.Z. and Z.W.; Funding acquisition: S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. ZR2024QF230).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bock, C.H.; Chiang, K.-S.; Del Ponte, E.M. Plant Disease Severity Estimated Visually: A Century of Research, Best Practices, and Opportunities for Improving Methods and Practices to Maximize Accuracy. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2021, 47, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Haynes, K.G.; Qu, X. Characterization of Early Blight Resistance in Potato Cultivars. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.-R.; Duan, L.-J.; Deng, Y.-J.; Liu, J.-L.; Long, C.-F.; Zhu, X.-H. Pest Detection Based on Lightweight Locality-Aware Faster R-CNN. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazarkar, S.; Keshavamurthy, B.N. A Survey on Image Data Analysis through Clustering Techniques for Real World Applications. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2018, 55, 596–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, M.N.A.; Abdullah, A.H.; Rahim, N.A.; Yazid, H.; Misman, S.N.; Masnan, M.J. Rice Leaf Blast Disease Detection Using Multi- Level Colour Image Thresholding. J. Telecommun. Electron. Comput. Eng. 2018, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lamba, S.; Kukreja, V.; Baliyan, A.; Rani, S.; Ahmed, S.H. A Novel Hybrid Severity Prediction Model for Blast Paddy Disease Using Machine Learning. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.K.; Tripathy, P.K.; Rout, S.K.; Pattanaik, C.R. An Enhanced Image Segmentation Approach for Detection of Diseases in Fruit. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Model. Des. 2022, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, C.U.; Jeevan Prasad, S.; Mounika, G. Leaf Disease Detection: Feature Extraction with K-Means Clustering and Classification with ANN. In Proceedings of the 2019 3rd International Conference on Computing Methodologies and Communication (ICCMC), Erode, India, 27–29 March 2019; pp. 1095–1098. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.; Das, N.; Das, I.; Maulik, U. Understanding Deep Learning Techniques for Image Segmentation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2019, 52, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polly, R.; Devi, E.A. Semantic Segmentation for Plant Leaf Disease Classification and Damage Detection: A Deep Learning Approach. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 9, 100526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzam, S.I.; Khan, U.S.; Qureshi, W.S.; Nawaz, T.; Kunwar, F. Towards Automated Weed Detection through Two-Stage Semantic Segmentation of Tobacco and Weed Pixels in Aerial Imagery. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 4, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Feng, W.; Wang, B.; Wang, H.; Luo, L.; Zhao, H. Research on Precise Segmentation and Center Localization of Weeds in Tea Gardens Based on an Improved U-Net Model and Skeleton Refinement Algorithm. Agriculture 2025, 15, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, S.; Su, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, L.; Tang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, M. Application of Advanced Deep Learning Models for Efficient Apple Defect Detection and Quality Grading in Agricultural Production. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Shi, A.; Xie, G.; Mu, S. Image Segmentation of Persimmon Leaf Diseases Based on UNet. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Signal Processing (ICSP), Xi’an, China, 15–17 April 2022; pp. 2036–2039. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Berwal, Y.P.S.; Ghai, W. Performance Analysis of Deep Learning CNN Models for Disease Detection in Plants Using Image Segmentation. Inf. Process. Agric. 2020, 7, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paula Gonçalves, J.; De Assis De Carvalho Pinto, F.; De Queiroz, D.M.; De Melo Villar, F.M.; Barbedo, J.G.A.; Del Ponte, E.M. Deep Learning Models for Semantic Segmentation and Automatic Estimation of Severity of Foliar Symptoms Caused by Diseases or Pests. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 210, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzia Rahim, U.; Mineno, H. Highly Accurate Tomato Maturity Recognition: Combining Deep Instance Segmentation, Data Synthesis and Color Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 4th Artificial Intelligence and Cloud Computing Conference, Kyoto, Japan, 17–19 December 2021; pp. 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, W.; Peng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Ren, Y.; Xue, Q. DCAU-Net: Dense Convolutional Attention U-Net for Segmentation of Intracranial Aneurysm Images. Vis. Comput. Ind. Biomed. Art 2022, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Hu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Hao, H.; Mou, L.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J. Multi-Scale U-Net with Edge Guidance for Multimodal Retinal Image Deformable Registration. In Proceedings of the 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 July 2020; pp. 1360–1363. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zheng, J.; Li, D. Precise Segmentation of Non-Enhanced Computed Tomography in Patients with Ischemic Stroke Based on Multi-Scale U-Net Deep Network Model. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 208, 106278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Yu, C.; Zhang, S. Lightweight Multi-Scale Dilated U-Net for Crop Disease Leaf Image Segmentation. Electronics 2022, 11, 3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Qiang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Lin, H. Semantic Segmentation of Small Target Diseases on Tobacco Leaves. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhai, S.; Lu, H. Load prediction based on depthwise separable convolution model. In Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on Mechatronics, Robotics and Automation (ICMRA), Zhanjiang, China, 22–24 October 2021; pp. 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Ren, H.; Wang, A. Smish: A Novel Activation Function for Deep Learning Methods. Electronics 2022, 11, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chen, B.; Wang, W.; Chen, L.-C.; Tan, M.; Chu, G.; Vasudevan, V.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; et al. Searching for MobileNetV3. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1314–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Semantic Image Segmentation with Deep Convolutional Nets and Fully Connected CRFs. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1412.7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient Channel Attention for Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11531–11539. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, R.-Y.; Li, L.; Xie, X. SimAM: A Simple, Parameter-Free Attention Module for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).