Coupling and Coordination Characteristics of Agricultural Water Resources and Economic Development in the Qilian Mountains Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Research Method

2.2.1. Super-SBM Model [22]

2.2.2. Comprehensive Evaluation Model [17]

- (1)

- Data standardization processing:where represents the data after non-dimensionalization; represents the original data; a and b are the lower limit (0) and upper limit (1) of the normalized range, respectively; and and are the minimum and maximum values of the factor quantization, respectively. Positive indicators are processed as shown in Equation (2), and for the inverse index, it is necessary to subtract the normalized value from the normalized upper limit.

- (2)

- Index weight calculation:where Pij is the proportion of the standardized value of the city-state index in the index; gj is the information entropy redundancy, which is used to evaluate the redundancy degree and repeated information process among indicators; Ej is the information entropy value of the j index, reflecting the information purity and difference of each index; n is the number of Pij; m is the number of gj; and Wj is the weight of the i index.

- (3)

- Construction of the comprehensive evaluation model:where Z represents the comprehensive evaluation index of the ith evaluation object, Wj represents the weight of the JTH indicator, and is a standardized indicator data value.

2.2.3. CCD Model [5,17]

2.2.4. Coefficient of Variation Method [17]

2.2.5. GM(1,1) Model [23]

- (1)

- Establish the original system sequence:X(0) = [x(0)(1), x(0)(2), …, x(0)n]

- (2)

- Accumulate the original sequence to generate the following new sequence:X(1) = [x(1)(1), x(1)(2), …, x(1)n]

- (3)

- Generate the mean sequence:Z(1) = [z(1)(2), z(1)(3), …, z(1)n]

- (4)

- Determine the mean form of the GM(1,1) model as follows:x0(k) + az1(k) = a

- (5)

- Calculate the model parameters as follows:â = [a,b]T = (BT × B)−1 × BTY

- (6)

- Establish the first-order cumulative time-response sequence prediction, as follows:x(1)(t) = (x(1) − b/a)exp(−a(t − 1))+b/a

- (7)

- Calculate the predicted value, as follows:

2.3. Index System Construction

3. Results

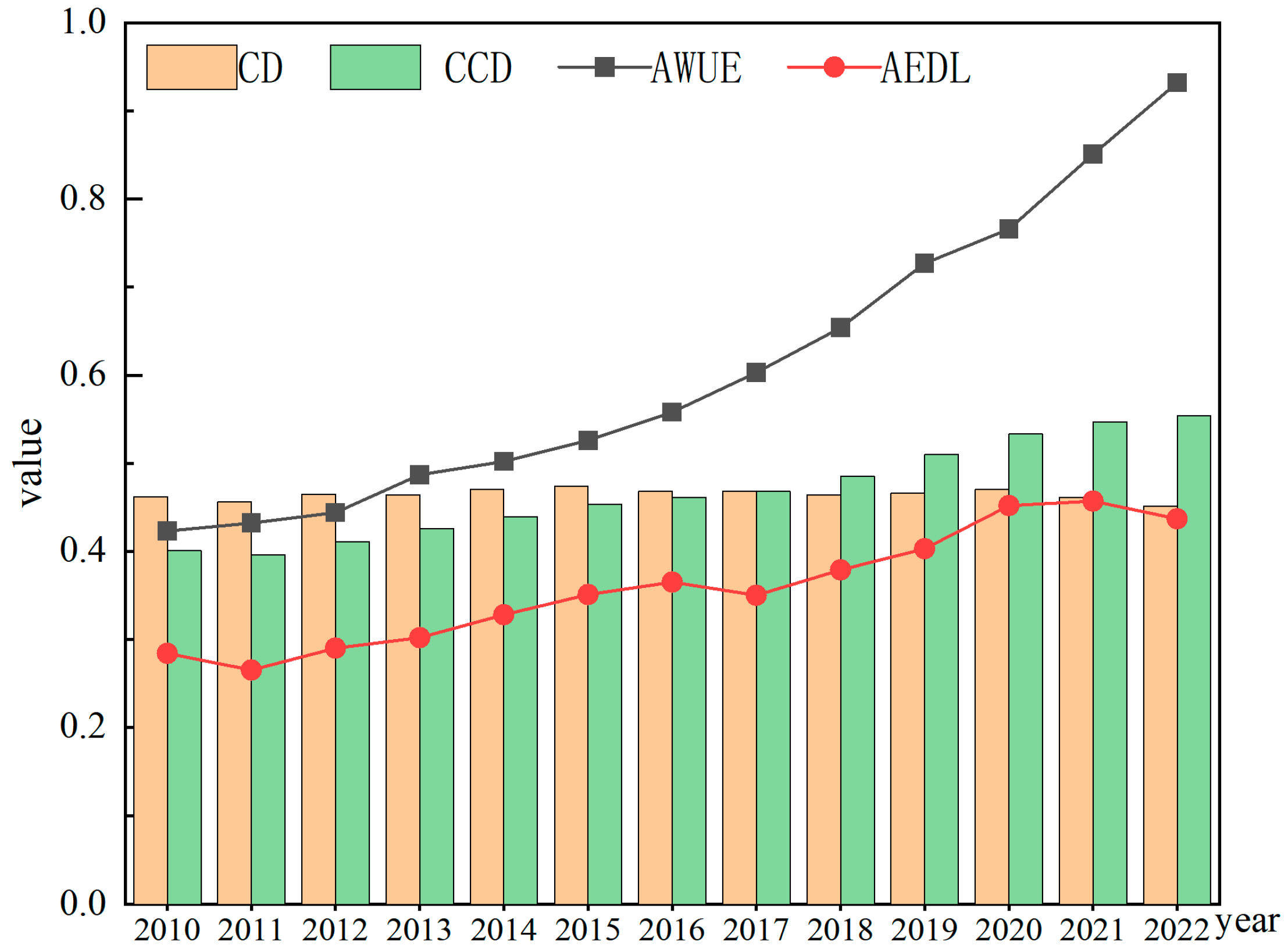

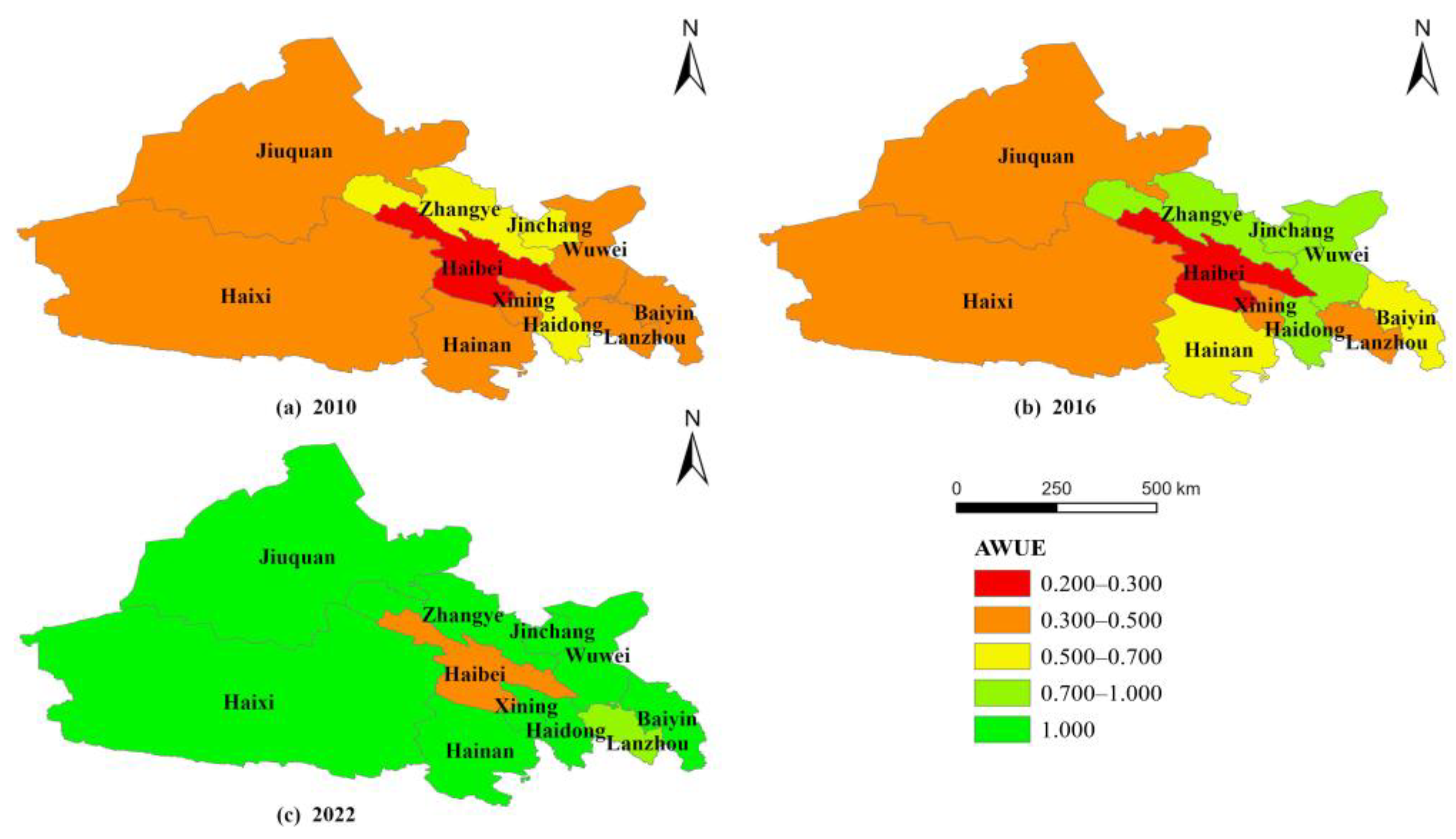

3.1. AWUE

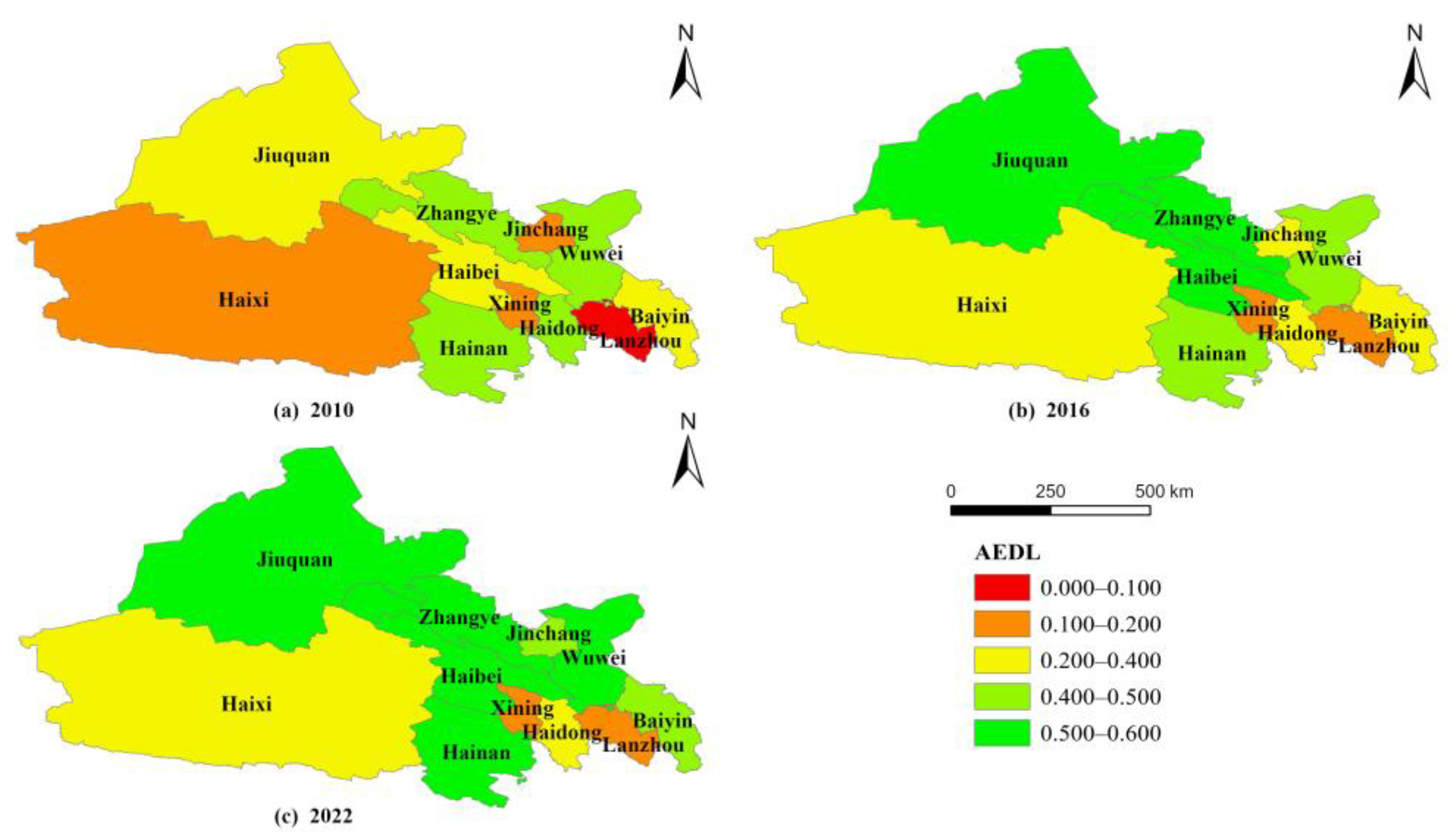

3.2. AEDL

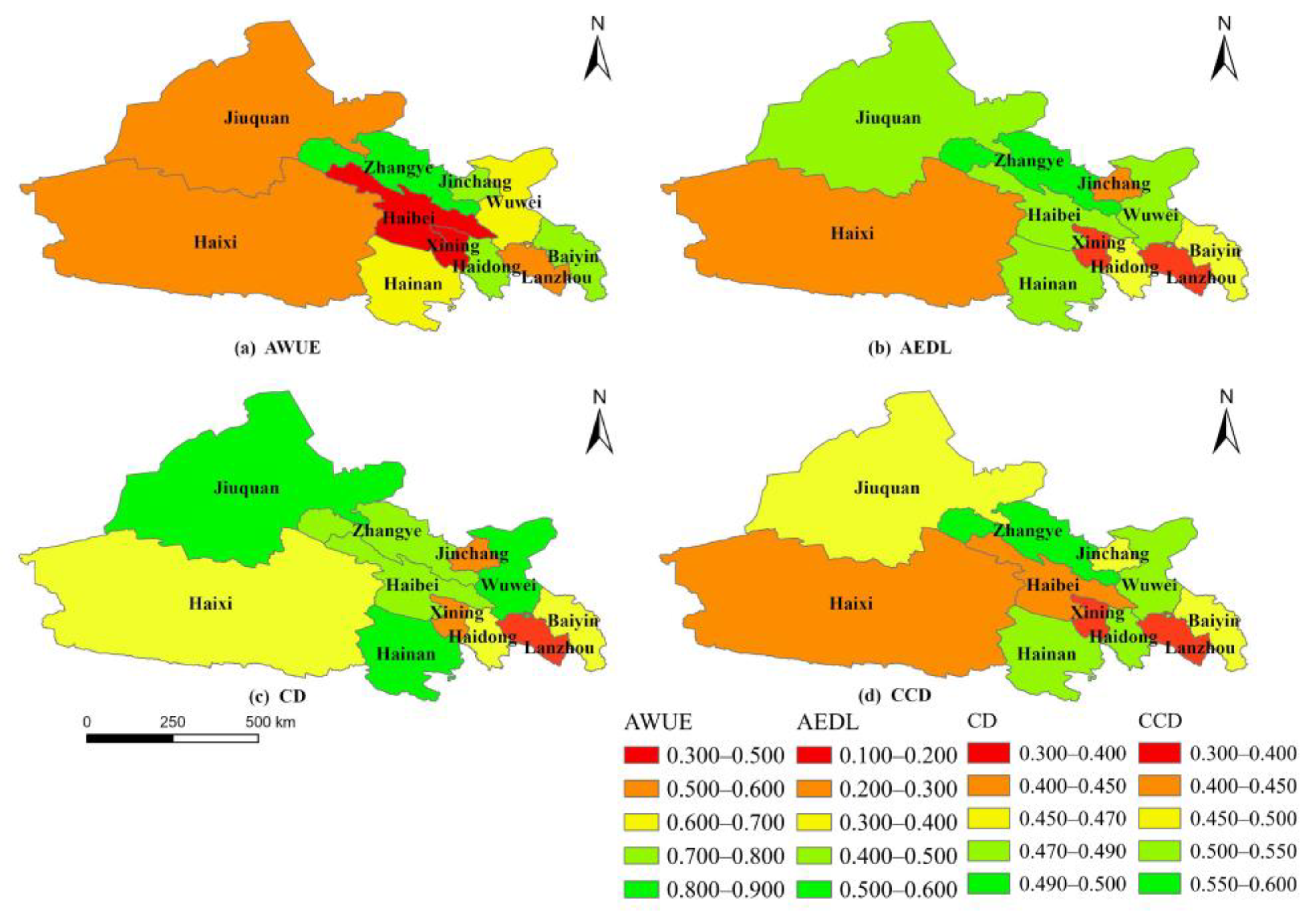

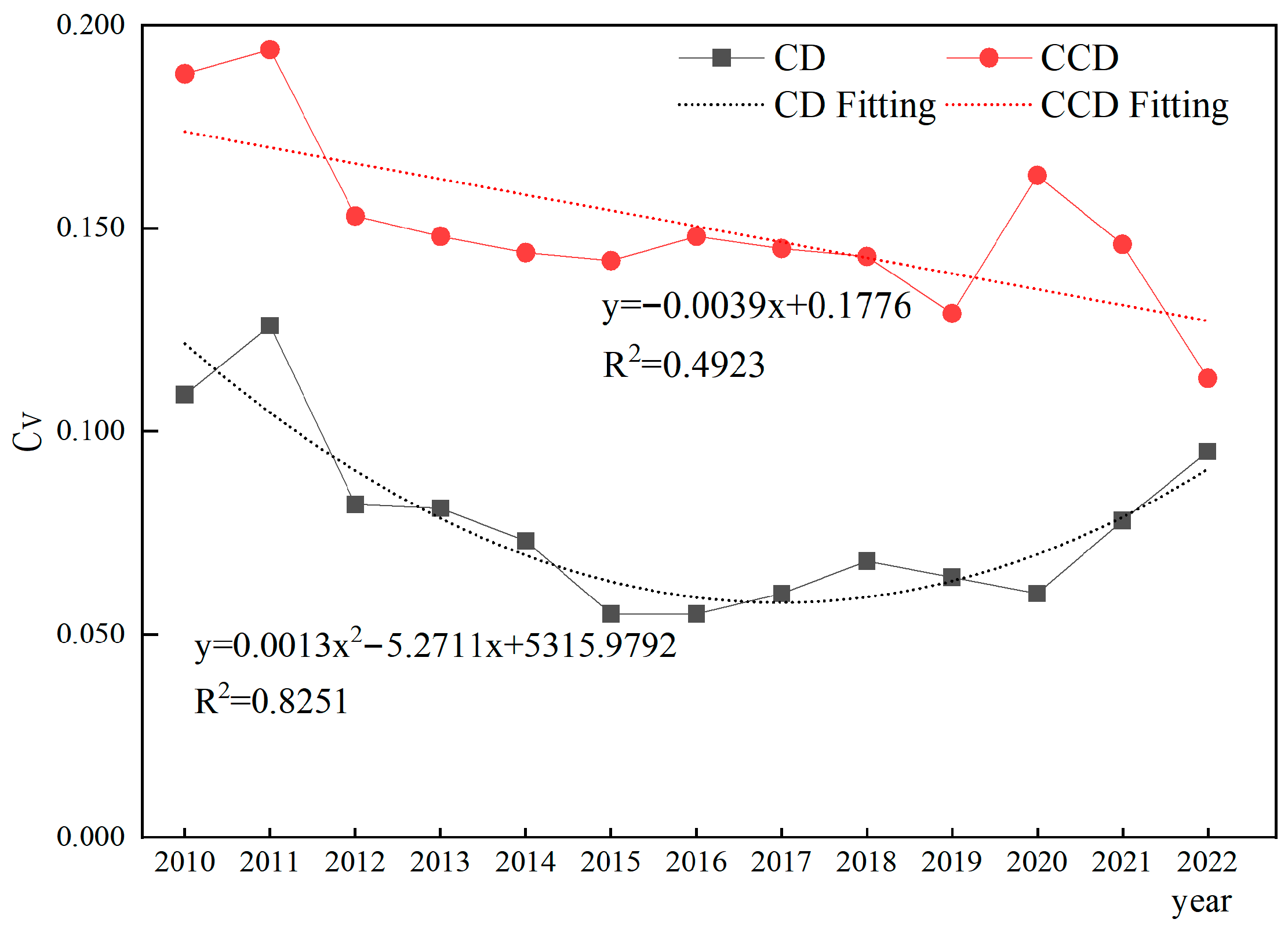

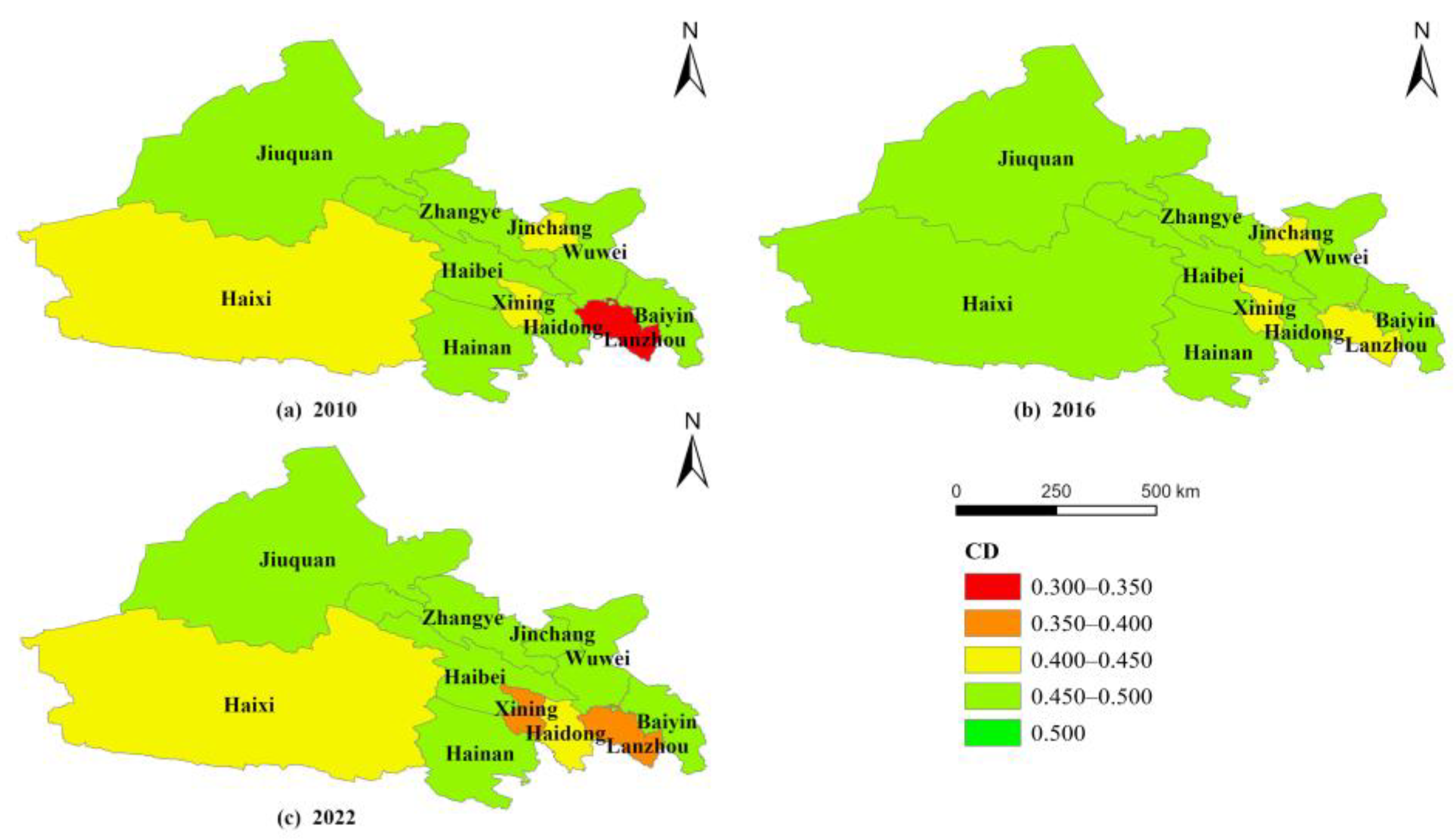

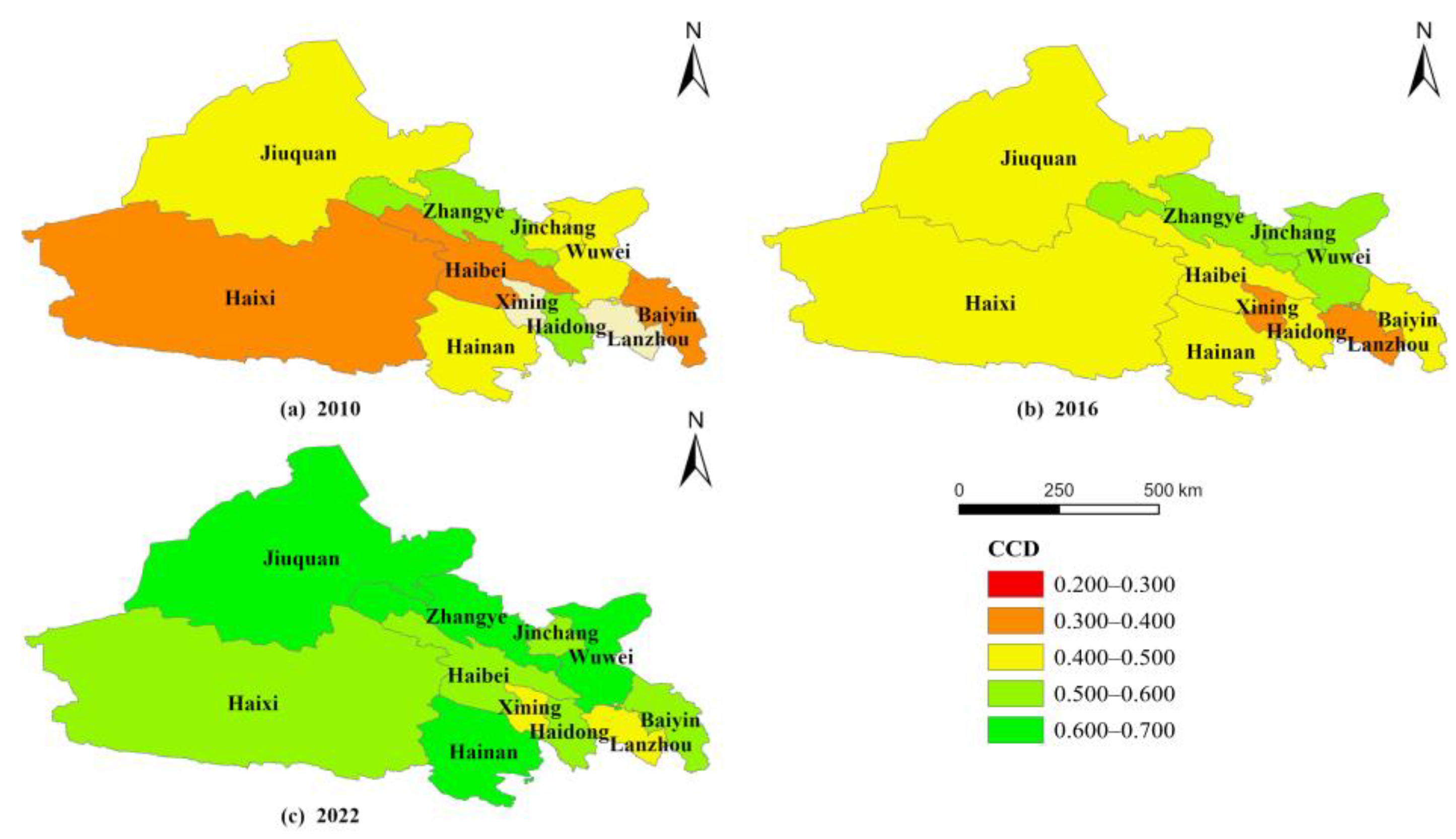

3.3. CD and CCD

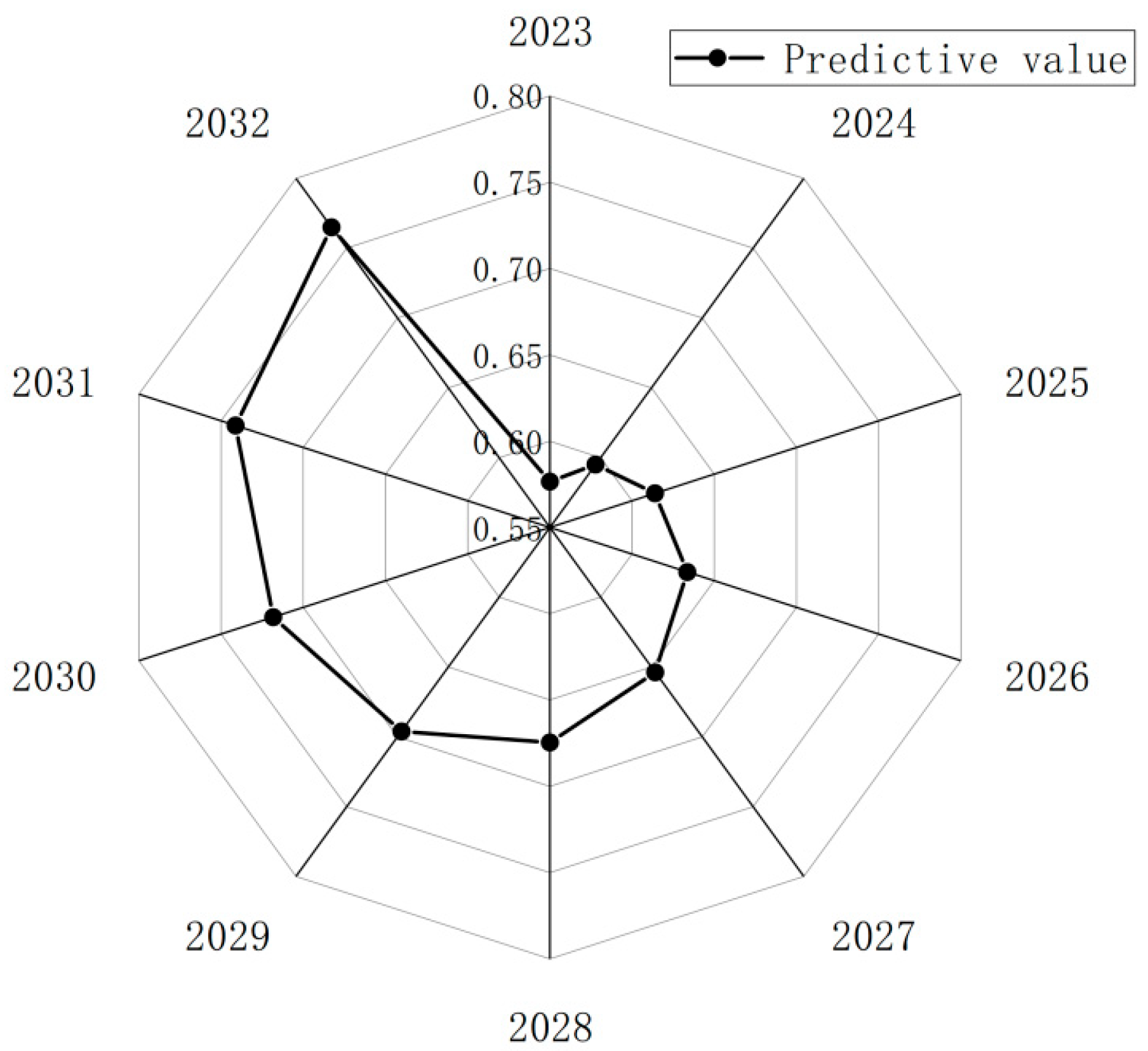

3.4. Prediction and Analysis of CCD

4. Discussion

4.1. Changes in AWUE and AEDL

4.2. Coupling Analysis of AWUE and AEDL

5. Conclusions

5.1. Conclusions and Recommendations

- (1)

- From 2010 to 2022, both AWUE and the AEDL in these areas showed an upward trend, with a spatial pattern summarized as being higher in the northeast and lower in other regions. By 2022, the overall AWUE has reached a high level, and most cities have achieved an effective status. Conversely, while the AEDL also increased substantially over the same period, the overall AEDL has remained relatively low, indicating significant room for improvement.

- (2)

- The AWUE and AEDL are currently in a ‘low coupling, high coordination’ development phase. The coordinated development patterns evolved via four distinct pathways: a highly coordinated sustainability pathway, growth-oriented pathway, transitioning pathway, and improving pathway. Overall, the CCD was found to be highest in cities with integrated primary, secondary, and tertiary industries, followed by agriculture-based cities with supplementary sectors, and then others based on animal husbandry with agricultural supplementation and those that are industry-based with agricultural supplementation. Spatially, the CCD is summarized as ‘high in the middle, low in the east and west’, with high coordination areas expanding from Zhangye City to Hexi Corridor regions, from middle to east and west, and from the northern to southern foothills, moving towards a higher level of coordination overall.

- (3)

- Considering industrial layouts, it is advisable to prioritize industries that offer substantial economic benefits with minimal water consumption to foster balanced development between AWUE and AEDL. Strategies should be tailored to local conditions: in Wuwei and Jinchang, the focus should be on Silk Road cold and arid agriculture, promoting efficient water-saving irrigation technologies and preventing the wastage of rural land resources due to the acceleration of urbanization [34]. In regions such as Zhangye and Jiuquan, emphasis should be placed on the rapid growth of the tertiary sector to maximize agricultural water-saving potential and optimize industrial structure [4]. In contrast, areas such as Baiyin and Haidong currently prioritize technical advancements in planting techniques and drought-resistance breeding to boost crop yields [12]. In water-rich regions, including Xining and Lanzhou, efforts should focus on raising water conservation awareness and improving agricultural water infrastructure [22]. Additionally, in prefectures such as Haibei, Hainan, and Haixi, it is essential to consistently increase agricultural fiscal investment, expand water conservancy coverage, and strengthen ecological stewardship [39].

5.2. Research Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Song, M.F.; He, W.J.; An, M.; Fang, X.; Wang, B.; Ramsey, T.S. Toward better agricultural grey water footprint allocation under economy-resource factors constraint. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.Z. Ten years of agricultural water-saving in China: Achievements, challenges and measures. China Water Resour. 2024, 10, 1–9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.W.; Wu, Z.; Tian, G.L. Research on water resources pricing model under the water resources–economic high-quality development coupling system: A case study of Hubei Province, China. Water Policy 2022, 24, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.L.; Li, X.Y.; An, H. Decoupling of water resources utilization and coordinated economic development in China’s Hexi Corridor based on ecological water resource footprint. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2022, 29, 90936–90947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Abliz, A.; Guo, D.P.; Liu, X.H.; Li, J.L.; Nurahmat, B. Coupling Coordination Development Between Cultivated Land and Agricultural Water Use Efficiency in Arid Regions: A Case Study of the Turpan-Hami Basin. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.X.; Cai, Y.; Khan, S.U.; Zhao, M.J. Decoupling analysis of water use and economic development in arid region of China—Based on quantity and quality of water use. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 761, 143275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalin, C.; Conway, D. Water resources transfers through southern African food trade: Water efficiency and climate signals. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, M.; Yang, J.; Wu, T.; Wang, S.; Zhao, X.; Tariq, A. Impact assessment of agricultural droughts on water use efficiency in different climatic regions of Punjab Province Pakistan using MODIS time series imagery. Hydrol. Process 2024, 38, 15232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotze, H.C.; Qotoyi, M.S.M.A.; Bahta, Y.T.; Jordaan, H.; Monteiro, M.A. A systematic review and Meta-Analysis of factors influencing water use behaviour and the efficiency of agricultural production in South Africa. Resources 2024, 13, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.N.; Guo, X.Y.; Liu, W.X.; Du, R.R.; Chi, S.Y.; Zhou, B.Y. Spatial–temporal dynamic evolution and influencing factors of green efficiency of agricultural water use in the Yellow River Basin, China. Water 2023, 15, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Tong, J.B.; Fang, Z. Assessing the drivers of sustained agricultural economic development in China: Agricultural productivity and poverty reduction efficiency. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.M.; Yang, Y.R.; Gong, G.F.; Chen, X.L. The coupling and coordination characteristics of agricultural green water resources and agricultural economic development in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 2131–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Khan, S.U.; Swallow, B.; Liu, W.X.; Zhao, M.J. Coupling coordination analysis of China's water resources utilization efficiency and economic development level. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373, 133874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.R.; Wang, Z.C.; Wu, T.H. Risk analysis and assessment of water resource carrying capacity based on weighted gray model with improved entropy weighting method in the central plains region of China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.Y.; Dai, H.C.; Liu, X.R.; Wu, Y.Z.; Liu, X.Y.; Liu, Y. Impacts of climate change mitigation on agriculture water use: A provincial analysis in China. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.N.; Duan, W.L.; Zou, S.; Chen, Y.N.; De Maeyer, P.; Van de Voorde, T.; Takara, K.; Kayumba, P.M.; Kurban, A.; Goethals, P.L.M. Coupling coordination analysis of the water-food-energy-carbon nexus for crop production in Central Asia. Appl. Energy 2024, 369, 123584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J.P.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Zhou, X. Coupling and coordination relationship between agricultural water use efficiency and agricultural economic development in the nine provinces (autonomous regions) along the Yellow River. J. Water Resour. Water Eng. 2021, 32, 219–2266. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.T.; Li, Z.X.; Feng, Q.; Lu, Z.X.; Zhang, B.J.; Chen, W.J. Evolution of ecosystem service values in Qilian Mountains based on land-use change from 1990 to 2020. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2024, 44, 4187–4202. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ren, H.; Zhao, W.Z.; Wang, X.P.; Luo, W.C.; Zhou, T. System Cognition and Key Challenges for the Future of Qilian Mountains Community of Life: A Case Study of Gansu Province. Adv. Earth Sci. 2024, 39, 957–967. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.J.; Jiao, L.; Zhang, H.; Du, D.S.; Zhu, X.L.; Che, X.C. Vegetation coverage variation in the Qilian Mountains before and after ecological restoration. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 408–418. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.F.; Park, K.; Shrestha, A.; Yang, J.; McHale, M.; Bai, W.L.; Wang, G.Y. Impact of human disturbances on the spatial heterogeneity of landscape fragmentation in Qilian Mountain National Park, China. Land 2022, 11, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.S.; Han, F.M.; Cai, A.N.; Zhang, K.; Jin, W. Influence of agricultural water use efficiency on agricultural water consumption in consideration of regional differences. Resour. Environ. Yangtze River Basin 2017, 26, 2099–2110. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yao, H.; Zhang, Q.X.; Niu, G.Y.; Liu, H.; Yang, Y.X. Applying the GM(1,1) model to simulate and predict the ecological footprint values of Suzhou city, China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 11297–11309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Mei, D. Sustainable development of China’s regions from the perspective of ecological welfare performance: Analysis based on GM(1,1) and the malmquist index. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 1086–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Bai, X.G. Evaluation on coupling coordination development of agricultural water use efficiency—Economic development—Ecological environment in the Yellow River Basin. China Rural Water Hydropower 2024, 6, 114–123. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cetin, M. The effect of urban planning on urban formations determining bioclimatic comfort area’s effect using satellitia imagines on air quality: A case study of Bursa city. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2019, 12, 1237–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.S.; Xu, X.D.; Su, Y.L. Evaluation and Prediction of Agricultural Water Use Efficiency in the Jianghan Plain Based on the Tent-SSA-BPNN Model. Agriculture 2025, 15, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.L.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.J.; Luo, Y.Z. Spatial and temporal differentiation of agricultural water use efficiency and its influencing factors under the combination of multiple models. Water Sav. Irrig. 2024, 4, 105–113. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Xiao, Y.; Gao, L.; Ma, D.; Su, R.; Yang, Q. How agricultural water use efficiency varies in China—A spatial-temporal analysis considering unexpected outputs. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 260, 107297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Wang, W.J. An Evaluation Scheme Driven by Science and Technological Innovation-A Study on the Coupling and Coordination of the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation-Economy-Ecology Complex System in the Yangtze River Basin of China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.Z.; Hao, X.M.; Du, T.S.; Tong, L.; Su, X.L.; Lu, H.N.; Li, X.L.; Huo, Z.L.; Li, S.E.; Ding, R.S. Improving agricultural water productivity to ensure food security in China under changing environment: From research to practice. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 179, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, L. Research on the coupling and coordination of harmonious rural construction and integration of agriculture and tourism. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.H. Analysis of the Measurement of high-quality development level of agricultural economy based on entropy weight method—Taking Shandong Province as an example. Rural Econ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 34, 99–102. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Jia, Y.Q.; Zhao, W.W. Ecological cycle of agriculture and economic development model in Zhangye. Pratacultural Sci. 2013, 30, 1488–1492. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Makapela, M.; Alexander, G.; Tshelane, M. Enhancing Agricultural Productivity Among Emerging Farmers Through Data-Driven Practices. Sustainability 2025, 14, 4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athelly, A.; Guzmán, S.M.; Yu, Z.W.; Watson, J.A. Bridging the gap between water-saving technologies and adoption in vegetable farming: Insights from Florida, USA. Agric. Front. Agron. 2025, 7, 162260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awa, M.; Zhao, J.H.; Tumaerbai, H. Deficit Irrigation-Based Improvement in Growth and Yield of Quinoa in the Northwestern Arid Region in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 107297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.Q.; Zheng, J.L.; He, M.N.; Feng, G.Z.; He, K.H.; Ma, T.; Coffman, D.; Mi, Z.F.; Wang, S.Y. A multi-regional input-output database linking Chinese subnational regions and global economies. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.P.; Li, W.D. Analysis of water use characteristics of different economic structures in Haixi prefecture of Qinghai province. Ecol. Sci. 2023, 42, 136–142. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| CD Value | Coupling Level | CCD Value | Coupling Coordination Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–0.3 | Low-degree coupling | 0–0.4 | Low coordination stage |

| 0.3–0.5 | Primary coupling | 0.4–0.5 | Moderate coordination stage |

| 0.5–0.7 | Intermediate coupling | 0.5–0.8 | High coordination stage |

| 0.7–1 | High-degree coupling | 0.8–1 | Extreme coordination stage |

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Measurable Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Input Indicator | Land | Crop sowing area/(kha) |

| Agricultural water resources | Irrigation water consumption/(×109 m3) | |

| Labor force | Number of employees in the primary industry/(×104 person ) | |

| Technological advancement | Total power of agricultural machinery/(×104 kWh) | |

| Capital | Pure chemical fertilizer equivalent/(t) | |

| Output indicators | Economic output | Gross output value of agriculture/(×104 CNY) |

| Physical output | Grain production/(10 kt) |

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Indicator Meaning | Index Attribute | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Development Scale | Per capita agricultural output value/(×104 CNY) | Total output value of agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fisheries divided by the number of primary industry workers | + | 0.215 |

| Agricultural Development Structure | Proportion of primary industry in GDP/% | Ratio of primary industry total output value to the regional GDP | + | 0.234 |

| Agricultural Development Investment | Proportion of fixed asset investment in primary industry/% | Fixed asset investment in the primary industry/total fixed asset investment | + | 0.241 |

| Proportion of agricultural fiscal expenditure/% | Agricultural financial expenditure/general budget expenditure | + | 0.131 | |

| Agricultural Economic Objectives | Disposable income of rural residents/(×104 CNY) | Disposable income of rural residents | + | 0.146 |

| Farmers’ Quality of Life | Rural Engel coefficient/% | Food, tobacco, and alcohol expenditure/consumer expenditure | − | 0.035 |

| Year | Original Value | Estimate Value | Residual | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 0.426 | - | - | - |

| 2014 | 0.439 | 0.397 | −0.001 | 1.052 |

| 2015 | 0.453 | 0.410 | 0.002 | 0.986 |

| 2016 | 0.461 | 0.423 | 0.003 | 0.357 |

| 2017 | 0.468 | 0.436 | 0.003 | 2.056 |

| 2018 | 0.485 | 0.450 | 0.003 | 1.622 |

| 2019 | 0.510 | 0.464 | −0.002 | 0.307 |

| 2020 | 0.533 | 0.478 | −0.010 | 1.527 |

| 2021 | 0.547 | 0.493 | −0.008 | 0.979 |

| 2022 | 0.554 | 0.509 | 0.001 | 0.807 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, H.; Ren, H.; Zhou, T.; Xu, X. Coupling and Coordination Characteristics of Agricultural Water Resources and Economic Development in the Qilian Mountains Region. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2551. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242551

Xu H, Ren H, Zhou T, Xu X. Coupling and Coordination Characteristics of Agricultural Water Resources and Economic Development in the Qilian Mountains Region. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2551. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242551

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Hua, Heng Ren, Tao Zhou, and Xiaolong Xu. 2025. "Coupling and Coordination Characteristics of Agricultural Water Resources and Economic Development in the Qilian Mountains Region" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2551. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242551

APA StyleXu, H., Ren, H., Zhou, T., & Xu, X. (2025). Coupling and Coordination Characteristics of Agricultural Water Resources and Economic Development in the Qilian Mountains Region. Agriculture, 15(24), 2551. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242551