Abstract

Accurate recognition of each cattle in group environments is essential for modern precision livestock management. This study proposed a multi-object cattle recognition method based on deep learning, enabling precise recognition in feeding passages. A dataset comprising facial images from 135 cattle was constructed, and a data augmentation strategy tailored to cattle facial characteristics was designed to enhance model generalisation. The YOLOv8n network was selected from a comparative experiment and further optimised. For multi-object bounding box regression, the standard CIoU loss was replaced by the MPDIoU loss, improving the mAP50 by 5.4% through optimised corner distance computation. In addition, a coordinate attention mechanism was embedded within the C2F module to strengthen the model’s spatial perception of key facial regions such as the eyes and nose, resulting in a 5.8% improvement in recognition precision. A comparative experiment between image-level segmentation and cattle-level segmentation datasets was carried out, and the proposed method was further validated on an untrained external test set collected from actual feeding Passages. The results demonstrate that, even under challenging conditions such as occlusion and illumination variation, the improved model achieved a classification accuracy of 88% while maintaining an average inference speed of 96.9 frames per second. This non-invasive, real-time recognition approach provides a novel solution for precision feeding in group-housed environments and offers valuable insights for improving the efficiency of livestock monitoring and feeding management systems.

1. Introduction

In intensive farming environments, where cattle are confined within barns, precise multi-target recognition becomes particularly critical for implementing automated feeding control, behavioral analysis, and precision health monitoring [1,2,3]. With the growth of the economy, there has been an increasing focus on high-quality meat and dairy products, leading to greater attention being paid to the health and disease status of individual cattle. This shift in public interest has prompted an increasing number of scholars to focus on individual cattle, and as a result, many new technologies have been applied in cattle research [4]. Traditional identification methods, such as branding, tattooing, and ear notching, have long been employed to differentiate individual cattle [5,6]. Although they provide a simple means of identity marking, these invasive physical methods cause pain, infection risks, and behavioral disturbances while also being susceptible to damage and counterfeiting [7,8,9]. The introduction of electronic recognition technologies, including RFID ear tags, collars, and pedometers, has improved traceability and data collection [10]. However, these devices remain dependent on physical attachment and may still provoke stress, detach, or malfunction in harsh farm conditions, making them unsuitable for fully automated and welfare-oriented systems.

With the rapid advancement of computer vision and deep learning, non-invasive image-based recognition has emerged as a promising alternative. Scholars have begun to explore the application of deep learning techniques in animal individual identification and behavioural recognition. Deep learning models can extract and learn discriminative biometric features from animal images, offering a scalable and animal-friendly solution. Since Kim et al. (2005) first demonstrated the feasibility of using coat patterns for cattle recognition [11], deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have revolutionised this field by achieving robust feature learning and improved classification precision [12]. Various biometric modalities have been explored, such as iris, muzzle, and retinal vessel patterns [13,14,15,16], yet facial recognition stands out due to the uniqueness and stability of cattle facial characteristics, including eye spacing, muzzle texture, and hair distribution [17,18]. Consequently, deep learning–based cattle facial recognition has become a key enabler of intelligent livestock management.

Nevertheless, several critical challenges remain before reliable facial recognition can be deployed in real farm environments. Current studies typically rely on self-collected datasets with limited diversity, making models prone to overfitting and poor generalisation [19,20]. In practice, cattle are frequently captured in visually complex settings: narrow feed alleys, high stocking density, mutual occlusion, non-uniform illumination, and substantial head pose variations [21,22]. These factors often obscure distinctive facial regions, resulting in reduced recognition precision and unstable performance [23,24,25,26]. An increasing number of researchers are improving existing algorithms for identifying animals by their individual traits or behaviors. Gong et al. (2024) added an iterative attention mechanism-based feature fusion module to YOLOv8 for the recognition of spotted deer. Their method increased precision by approximately 6 percentage points and average absolute precision (mAP50) by approximately 4.6 percentage points [27]. Ma et al. (2024) introduced lightweight improvements and focus mechanisms to the YOLOv5 model, which has led to the detection of wild animals in the wild [28]. Fang et al. (2024) integrated the Convolution Block Attention Module (CBAM) in YOLOv8 for sheep and cattle detection, and CBAM precision and recall have been significantly improved [29]. Chen et al. (2024) combined the attention mechanism (AM) with specialised small target areas using YOLOv8n to significantly reduce the missed detection in complex environments such as leaves and changes in lighting [30]. Qin et al. (2025) embedded CBAM into the YOLOv8 backbone network and modified the data augmentation (DA) strategy and loss function to enable the recognition of individual sheep, which significantly improved the precision of the recognition [31]. Together, these studies show the feasibility of improving YOLO algorithms for individual recognition of animals using facial images and highlight their great potential and benefits. However, most existing works focus on detecting or recognizing single animals, and the generalisation ability of the resulting models has remained a significant challenge. Moreover, the problem of recognising multiple cattle in shared feeding troughs, where several cows appear simultaneously, still requires further investigation. Addressing this issue requires models capable of robust feature extraction, fine-grained localization, and strong resistance to visual noise [32].

To overcome these limitations, the present study proposes an enhanced deep learning framework for multi-cattle facial recognition in complex feeding-passage environments. Built upon the YOLOv8n architecture, the framework introduces two major innovations. First, a Coordinate Attention mechanism (CAM) is integrated to strengthen the model’s ability to capture fine-grained spatial and passage dependencies, enabling more accurate localization of key facial features such as the eyes, ears, and muzzle. Second, an optimised loss function is designed to improve detection stability and discrimination under dense multi-target conditions. To facilitate training and evaluation, we establish a dedicated feeding-passage cattle face dataset, characterised by frequent occlusion, illumination variation, and high inter-individual similarity. Through comprehensive comparative experiments under both image-level and cattle-level data splits, the proposed approach demonstrates superior robustness and generalisation compared to existing methods.

Overall, this study provides a scalable, non-invasive, and high-precision solution for multi-cattle recognition under real farm conditions. The findings contribute to advancing the automation of precision livestock management and lay the foundation for developing intelligent vision-based systems that integrate feeding behavior analysis, health monitoring, and welfare assessment.

2. Materials and Methods

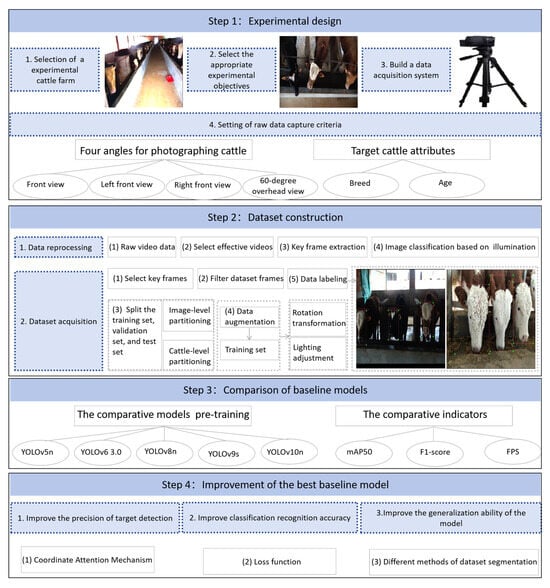

This section describes the overall methodology employed to develop and evaluate the proposed multi-cattle facial recognition framework. The research consists of four stages: experimental design, dataset construction, comparative selection of baseline models, and improvement of individual recognition models for multiple cattle. The overall framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The flowchart of the research.

2.1. The Setup of Experiments

The field experiment was conducted on two commercial beef cattle farms: Farm A, located in Jiangxi Province, China, from 18 to 24 November 2018; and Farm B, located in Xuchang, Henan Province, China, from 15 to 25 June 2022, both of which raise Simmental and yellow beef cattle (Ycattle) under semi-intensive feeding systems. The cattle farm environment is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

(a,b) display the experimental environment in the two cattle farms.

Farm A, located in a cold plain region, maintains approximately 200 Simmental cattle and 100 Ycattle, each weighing between 180 and 280 kg and aged 12–24 months under a tie-stall system. The feeding passages are approximately 0.5 m wide, and cattle are managed in groups of 10–15 individuals. This site provided more visually complex scenes due to the presence of shadows, reflective feeding troughs, and frequent inter-cattle occlusion. Farm B is situated in a plain area characterised by moderate temperature and natural daylight exposure. It houses approximately 150 Simmental cattle, each weighing between 160 and 250 kg and aged 10–18 months, under a loose system. All animals were clinically healthy and free from visible skin disease or injury. Data collection covered different times of day (morning and evening feeding sessions) to capture illumination variation and diverse animal behavior.

The experimental setup was designed to replicate the visual complexity typical of confined beef production environments. Each pen contained multiple cattle feeding simultaneously within narrow alleys equipped with automated troughs. Video data were captured using a Sony FDR-AX40 (it was manufactured by Sony Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) camcorder mounted on an adjustable tripod. Cameras were mounted approximately 1.8–2.5 m above the ground and 1.2 m from the feeding line. Shoot the cattle from four angles: straight ahead, left front, right front, and a 60-degree overhead view, to capture facial views.

At the Farm, natural daylight was the main illumination source, supplemented by overhead lamps during cloudy periods. Each recording session lasted 10–15 min, with each image containing three individual cattle, producing approximately 40 videos per day per farm. The video files were stored in MP4 format on memory cards, with a frame rate of 25 frames per second (fps) and a resolution of 3840 × 2160 pixels. During the experiment, cattle were allowed to feed freely without restraint, ensuring the captured images reflected natural variations in head movement, interaction, and occlusion among individuals.

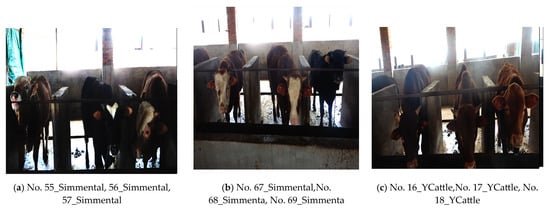

2.2. Data Acquisition

In this experiment, extract frames containing clear facial regions using code programs based on the video data obtained from the experiment. After extracting frames from the video data, a preliminary dataset of over 600,000 raw cattle face images was obtained. To ensure dataset diversity and representativeness, image selection covered: multiple head poses (frontal, overlook, side), different lighting conditions (natural daylight, shadowed), varying degrees of occlusion (none, partial, severe). These raw images exhibit characteristics of a complex environment, presenting significant challenges as illustrated in Figure 3a–c. As each recording session lasted only 10–15 min, the posture of most cattle remained largely unchanged, resulting in multiple images of the same animal captured from similar viewpoints. Following frame extraction, the majority of low-quality or highly similar images were removed to ensure the overall quality of the dataset. Images exhibiting notable variations in illumination or head pose were retained to maximise dataset diversity, which also helped reduce computational load and improve processing efficiency. The final dataset consists of data from 135 cattle, with 2368 facial images (including 50 negative images) collected from 123 cattle used for training the model. The remaining data from 12 cattle were reserved for external validation to evaluate the model’s generalisation ability. The cattle were selected in a balanced manner across two farms, and each cattle was assigned a unique ID, ranging from “NO 1_Breed” to “NO 135_Breed”, and a professional image annotation tool LabelImg was employed to draw bounding boxes for each image. The cattle breeds include Simmental cattle and Ycattle. This dual-farm design provided a broader range of environmental variations. Farm A introduced high-density indoor scenes with frequent occlusion and illumination shifts, while Farm B emphasised natural light and moderate density, ensuring comprehensive evaluation of model generalisation.

Figure 3.

Significant challenge image examples ((a) low lighting, (b) occlusion interference, (c) high similarity).

2.3. Data Preprocessing and Dataset Construction

2.3.1. Image Enhancement and Normalization

All annotated images underwent standardised preprocessing before being fed into the neural network. Each image was resized to 416 × 416 pixels. Histogram equalization and color normalization were applied to correct illumination imbalance and enhance contrast. Gaussian filtering was used to suppress background noise and reduce motion blur. Finally, pixel values were normalised to the range [0, 1] to ensure consistent input scaling across the dataset.

2.3.2. Dataset Partition Strategy

Previous studies have demonstrated that simple random partitioning may result in an overestimation of model performance and overfitting [33]. Two complementary partition strategies were implemented to evaluate both recognition precision and generalisation ability. For the image-level division, all images were randomly split into 70% for training, 20% for validation, and 10% for testing, regardless of individual overlap. For the cattle-level division, the dataset was split according to cattle identity at the same 7:2:1 ratio, ensuring that certain individuals were completely excluded from the training set and used solely for testing. A standardised multi-object cattle individual recognition dataset was constructed. This strategy simulated real-world scenarios where a model must identify previously unseen cattle. The dual partition design allowed a comprehensive comparison between intra-individual and inter-individual recognition performance.

2.3.3. Data Augmentation

To improve model generalisation and robustness under variable environmental conditions, a set of geometric and photometric augmentation techniques was applied dynamically during training. Random rotation (±10°) and horizontal flipping were used to simulate variations in head orientation. Random brightness, contrast, and hue adjustments were applied to emulate illumination changes between indoor and outdoor settings. Because the training set is used to train neural nets, whereas the validation and testing sets are used to evaluate the final performance of the model. The study only increased the training set by two times, and did not increase the data for the test and validation sets; only the necessary pre-treatment was carried out to ensure the stability and comparability of the results of the validation and testing. Simulate the different positions and facial expressions that cattle can exhibit in their natural environment. These augmentation techniques jointly ensured that the training dataset closely reflected real-world variability in lighting, head pose, occlusion, and background complexity. A detailed description of the number of class instances or objects in each dataset is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the datasets using two splitting strategies.

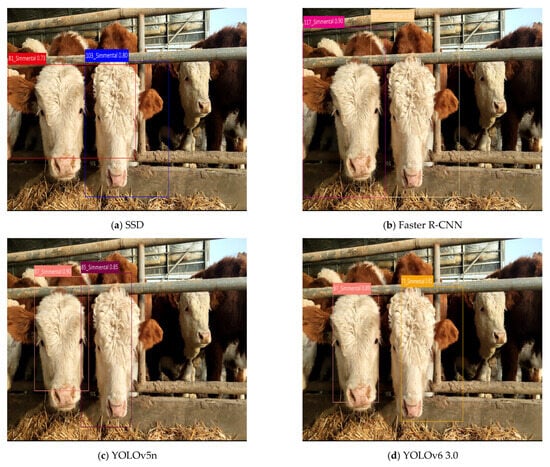

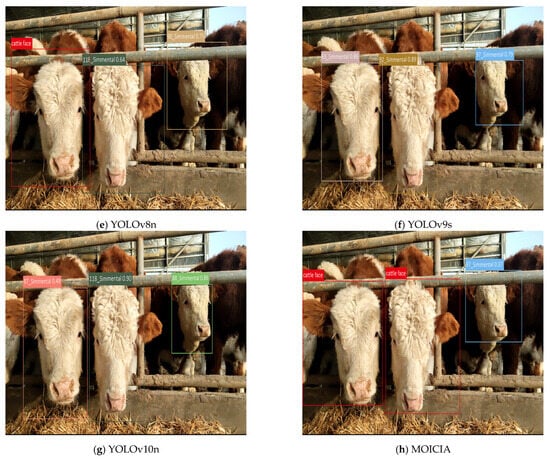

2.4. Multi-Object Cattle Individual Recognition Framework

According to previous research findings, the YOLO series of algorithms demonstrates significantly higher training precision and speed in animal facial recognition tasks compared with traditional approaches [34,35,36,37,38]. Therefore, this study analyzes object detection and classification algorithms by comparing algorithms such as SSD, Faster R-CNN, YOLOv5n, YOLOv6 3.0, YOLOv8n, YOLOv9s, and YOLOv10n. The comparison aims to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of these algorithms to select the most suitable one for cattle face recognition and optimization. The results indicate that YOLOv8n shows obvious advantages in both recognition precision and speed, particularly in handling noise in complex cattle farm environments.

2.4.1. YOLOv8n Baseline

The YOLOv8n algorithm was selected as the baseline model for individual cattle facial recognition due to its balance between recognition precision and inference efficiency. The architecture consists of three main modules: a CSP-based backbone for hierarchical feature extraction, a bidirectional feature pyramid network for multi-scale feature fusion, and a decoupled head responsible for simultaneous object classification and localization. The loss function of YOLOv8n was optimised by combining Complete IoU (CIoU) loss with Focal loss to balance localization precision and classification difficulty. The total loss function was defined as

where represent the classification, bounding box regression, and objectness confidence losses, respectively. The weighting coefficients λ1, λ2, and λ3 were empirically tuned through ablation experiments to achieve optimal performance across detection precision and convergence stability.

This design enables YOLOv8n to achieve high precision while maintaining real-time performance, which is essential for practical livestock monitoring applications.

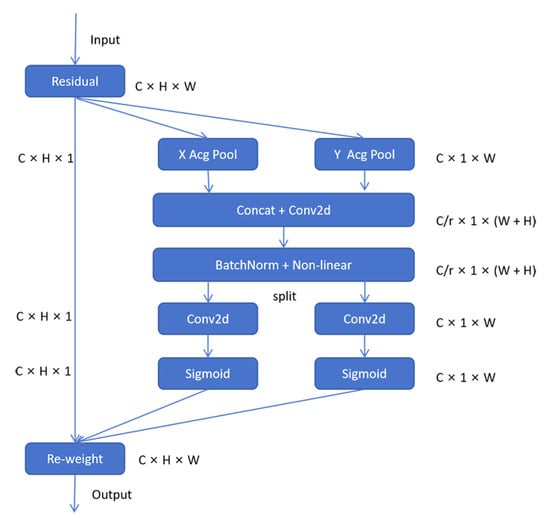

2.4.2. Coordinate Attention Integration

Due to the complexity of backgrounds and diverse shapes in the cattle face recognition task, the feature extraction process is prone to interference. The key facial features are lost after downsampling by the backbone network, making it difficult for the model to accurately capture facial details. To enhance the model’s feature discrimination under dense multi-cattle scenarios, a coordinate attention integration (CAM) was incorporated into the backbone to enhance the model’s ability to capture facial features. The CAM captures cross-dimensional interactions in the input data through three branches and calculates attention weights. The left branch processes the input feature map directly, performing average pooling in the X and Y directions (Avg Pool), concatenation (Concat), and convolution layers (Conv2d), followed by batch normalization (BatchNorm) and non-linear activation functions. The middle and right branches use permutation to adjust the dimensions of the input feature map and combine the results with pooling operations. Finally, the outputs from each branch are merged through element-wise addition after a second permutation. Unlike conventional passage attention that focuses solely on inter-passage relationships, CAM captures both spatial and passage dependencies, allowing the model to encode precise positional information while maintaining global contextual awareness. The CAM modules were embedded after the C2f blocks in deeper layers, enabling accurate localization of fine-grained features such as the eyes, ears, and muzzle. The coordinate-attention-based mechanism effectively integrates spatial and passage information, combining features at different levels, refining meaningful global and local features, and facilitating information transmission while reducing feature loss. This modification allows the network to better distinguish adjacent cattle faces and suppress background interference, thereby improving precision and robustness in crowded environments. The coordinate attention structure diagram is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Coordinate attention structure diagram.

2.4.3. Optimised Loss Function

During training, we use Intersection over Union (IoU) to evaluate the model’s precision in bounding box regression tasks. By calculating the ratio of the overlapping area between the predicted bounding box and the ground truth box to their union area, IoU reflects the similarity between the predicted bounding box and the actual target. The IoU is defined as the intersection of A (the actual bounding box of the frame) and B (the predicted bounding box of the frame). The symbols “∩” and “∪” represent mathematical operations on A and B: “∩” denotes the intersection between A and B, which refers to the overlapping area between B and A. “∪” represents the union of A and B, referring to the total area covered when the two bounding boxes (A and B) are combined, as defined in Equation (2).

In the cattle farming environments, the complexity of environmental conditions directly affects the precision of bounding box regression, which in turn determines the overall performance of the object detection model, especially in scenarios like Multi-object cattle individual face recognition, which requires precise localisation. Although the traditional CIoU loss function can consider factors such as the distance between the centre points, the overlap area, and aspect ratio, it still has limitations when dealing with subtle differences in the positions of the target bounding box corners, often leading to localisation bias. To address this issue, this paper introduces the MPDIoU (Modified Point Distance-based IoU) loss function as a new strategy for bounding box regression. MPDIoU not only inherits the CIoU’s ability to optimise the centre point distance and scale differences, but also further introduces a corner distance measurement mechanism. This improvement significantly enhances the model’s sensitivity to the target boundary, particularly when facing challenging scenarios such as complex backgrounds or target occlusions. As a result, it notably strengthens the model’s localisation robustness and precision, thereby comprehensively improving the detection quality of multi-object cattle individual facial recognition. The loss function is as follows:

where represent the coordinates of the top-left corner of the predicted bounding box, and represent the coordinates of the top-left corner of the ground truth bounding box, while Coordinates of the top-left corner point of the prediction box, and Coordinates of the top-right corner point of the ground truth box, prd denotes “predicted”, while gr refers to the “ground truth”. The symbols w and h represent the width and height of the predicted bounding box, respectively. By calculating the Euclidean distance between the key corner points of the predicted and ground truth boxes, finer adjustments to the bounding box location can be achieved.

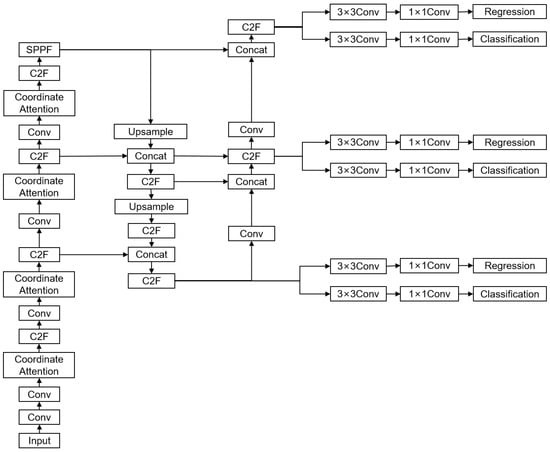

2.4.4. Multi-Object Individual Cattle Recognition Network Framework

Based on YOLOv8 as the baseline, we introduced a CAM before the C2f stage to enhance the network’s ability to learn key features. Additionally, we introduced the MPDIoU loss function to optimize object detection performance. The algorithm used in this paper is referred to as the multi-object individual cattle recognition algorithm (MOICIA), and its network architecture is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

MOICIA’s main network architecture.

2.4.5. Training Setup

Model training was conducted on an NVIDIA RTX 3080 GPU (24 GB VRAM) using the PyTorch-2.2.1 framework. The initial learning rate was set to 0.001 with a cosine decay schedule. The AdamW optimizer was employed, with a batch size of 16 and a total of 200 epochs. The input resolution was 416 × 416 pixels, and early stopping combined with model weight averaging was adopted to stabilize convergence and prevent overfitting. The best-performing model checkpoint was selected based on the highest mAP50 achieved on the validation set.

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

Model performance was quantitatively evaluated using standard object detection metrics. Precision (P) was defined as the proportion of correct detections among all predicted objects, while Recall (R) represented the proportion of correctly detected targets among all ground-truth objects. Mean Average Precision (mAP50) represents the average AP when the Intersection over Union (IoU) is greater than or equal to 50%. It was employed to assess overall detection precision. The F1-score, representing the harmonic mean of precision and recall, provided a balanced measure of detection performance. In addition, the inference speed, expressed as frames per second (FPS), was evaluated to assess the model’s suitability for real-time deployment in farm environments. The F1 score calculation formula is shown in Equation (8).

where TP denotes the number of True Positives, FP denotes False Positives, and FN denotes False Negatives.

The mAP is the average of the AP values across all classes, primarily used to evaluate the overall performance of the model, as shown in Equation (10). In this study, multiple classes are involved. A higher mAP value indicates better performance of the object detector.

Finally, data from the remaining 12 new cattle are used to confirm the MOICIA detection and recognition results under various lighting conditions, levels of occlusion, and head positions for qualitative analysis. This analysis intuitively demonstrates the robustness and applicability of the model to the individual recognition of cattle with multiple target species under realistic feed passage scenarios.

3. Results

3.1. Performance on Multi-Object Individual Cattle Face Detection

This study established a multi-object cattle face recognition model based on the proposed MOICIA algorithm, aiming to achieve accurate individual recognition under complex farm environments. Two datasets collected from different pastures were used to evaluate detection and recognition performance. For the cattle face detection task, the model was trained with a batch size of 16 and an initial learning rate of 0.001. After 200 epochs, mAP50 converged, and precision stabilised, indicating adequate training.

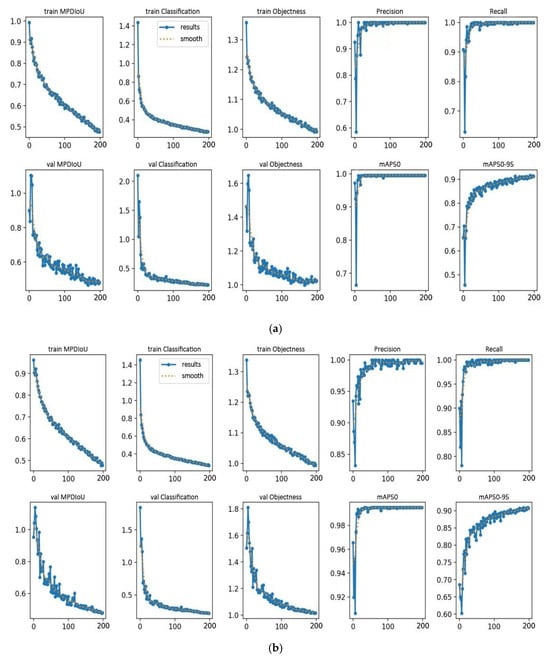

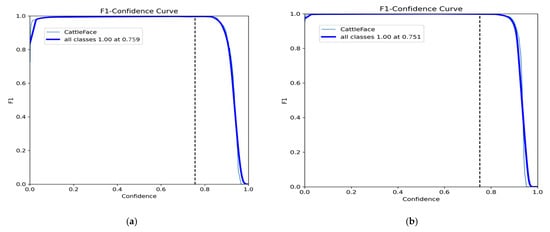

Two dataset partitioning strategies, image-level and cattle-level partitioning, were applied to assess the model’s robustness and generalisation. The training performance is illustrated in Figure 6, where the loss curves and metric trajectories demonstrate stable convergence. As shown in Figure 7, both partitioning strategies achieved high precision, with the mAP reaching 99.5% and the F1 score attaining the highest observed values across training. Notably, when the confidence threshold for image-level partitioning is 0.759, the model achieves the optimal combination, and when the confidence threshold for cattle-level partitioning is 0.751, the model also achieves the optimal combination. The model training results indicate that the image-level model achieved slightly superior detection precision.

Figure 6.

Performance of indicators during multi-object cattle face detection training. (a) The performance of MOICIA during the training process when the image-level partitioning dataset. (b) The performance of MOICIA during the training process when the cattle-level partitioning dataset.

Figure 7.

Model performance of cattle face detection under different dataset partitioning methods. (a) The performance of the F1-confidence curve when the image-level partitioning dataset. (b) The performance of the F1-confidence curve when the cattle-level partitioning dataset.

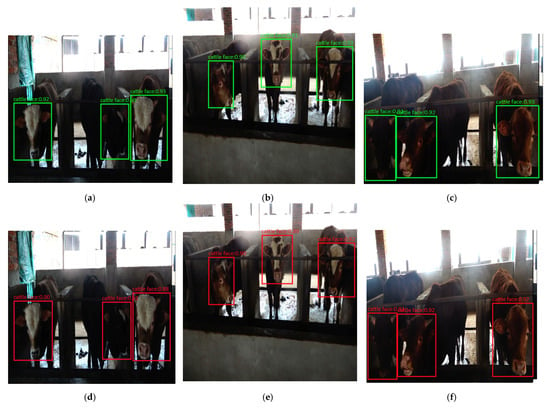

Representative detection outcomes on the two test sets under low illumination, partial occlusion, and visually similar individual conditions are presented in Figure 8. Across both partitioning methods, each cattle face was correctly localised, and bounding boxes accurately encompassed the facial regions. When tested on image-level partitioned data, the detection precision exceeded 90% for all individuals, whereas for the cattle-level partitioned dataset, the precision remained above 88%. Even when tested and evaluated on 12 previously unseen cattle in the external test set, both models maintained strong detection robustness. These findings demonstrate that both partitioning strategies effectively support multi-object cattle face detection.

Figure 8.

Illustrates the results of multi-object cattle face detection under different dataset partitioning strategies. Images (a–c) present the detection results of the model trained on the image-level partitioned dataset, whereas images (d–f) show the detection results obtained from the model trained on the cattle-level partitioned dataset.

3.2. Multi-Object Cattle Individual Recognition

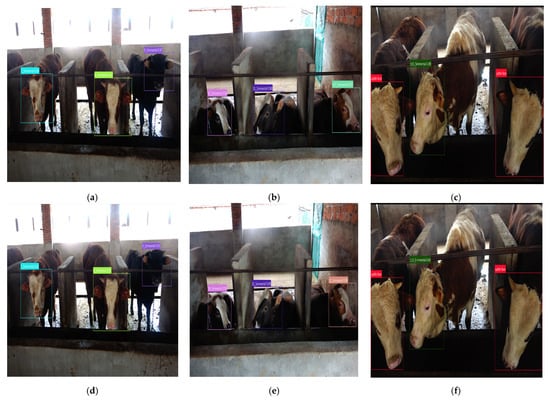

The detected cattle faces were standardised before being input into the classification network. When the MOICIA model reached optimal performance, both partitioning strategies achieved training precision of 99.5% and mAP values of 99%, reflecting excellent recognition capability. Under image-level partitioning, the MOICIA model achieved an overall recognition accuracy of 98.1% on the test set (9 misclassifications among 474 images). Research has found that when the dataset is segmented at the image level, the model is able to test the classification recognition results on the test set, achieving good accuracy. However, when the dataset is segmented at the individual cattle level, the model fails to produce classification results on the test set, as it has never encountered the specific cattle in the training data, whether from the test set or an external testing set. Therefore, when discussing individual cattle recognition, the test set and external test set segmented by individual cattle-level are used solely to evaluate the model’s rejection recognition ability, which reflects the model’s generalisation capacity. In this study, it is defined that when the model tests an untrained cattle, it only outputs “cattle face” without displaying the cattle ID label, which indicates that the model has correctly identified the cattle, as no matching cattle were found in the trained dataset. On the other hand, when the model outputs a cattle ID with a confidence score below 50%, it suggests that the model is uncertain about the identification, which can be considered as a near-correct result. Both indicate good generalisation ability of the model. If the model identifies a cattle that was part of the training set with a high confidence score, it signifies an incorrect identification, indicating poor generalisation ability of the model. Therefore, test results can be obtained. In contrast, the cattle-level partitioning model achieved 92.1% (36 misclassifications among 456 images), despite having no prior exposure to those individuals. For clarity, Figure 9 presents several representative examples of both models’ performance in identifying both trained and untrained cattle across various scenarios within the test set.

Figure 9.

Presents examples of multi-object cattle individual recognition results. Images (a–c) illustrate the test recognition outcomes of the model trained based on the image-level partitioned dataset, while images (d–f) show the corresponding results obtained from the model trained on the cattle-level partitioned dataset.

In Figure 9, Images (a) and (b), as well as (d) and (e), depict the test results of cattle included in the training set of two models. While images (c) and (f) feature cattle’s test results that were not included in the training set. In contrast, images (c) and (f) display the test results of cattle not included in the training set, demonstrating the models’ ability to reject unrecognised objects during testing. The results show that the performance of both training strategies in identifying nine cattle in three samples differs significantly. Note that images a and d, and b and e show the same scene in the training set. When using the test images, all three cattle in image a, captured from a frontal standing view, were correctly identified by both models. The model trained with the dataset divided by the cattle-level partitioning achieved a recognition precision exceeding 90%, whereas the model trained with the dataset divided by the image-level partitioning attained a slightly lower precision, albeit still above 87%. In image b, where all three cattle were captured in a lying posture, the cattle-based model successfully identified all individuals, though with marginally reduced precision compared with the frontal-standing scenario. In contrast, the image-based model misclassified cattle No. 32 as No. 107, indicating that an animal’s posture (standing versus lying) during image acquisition has a notable impact on multi-object recognition precision. Image c presents the results of the test on three untrained cattle. For these untrained cattle, the model trained on a dataset of cattle-level partitioning, if correctly recognised, will yield two types of prediction results. The first has a precision of less than 50 percent, indicating uncertainty or inconsistency. The second one does not display labels and only displays detected “cattle face”, indicating that no matching cattle have been found in the database. But the image-level model tended to misclassify unseen cattle as visually similar individuals from the training set, indicating weaker generalisation ability. Conversely, as shown in image c of Figure 9, a model trained on an image-level segmentation dataset incorrectly identified an untrained cattle as the visually similar cattle number 113, with a precision of 89%. This outcome suggests that the model based on a dataset of image-level data possesses weaker generalisation capability. The image-level model tended to misclassify unseen cattle as visually similar individuals from the training set. Moreover, frontal-standing images consistently produced higher recognition precision compared with other capture angles, such as lying or top-down views.

Statistical results confirm these observations. When evaluated on an external dataset of 100 images from 12 untrained cattle, both models achieved accuracies of 79% and 88% under image-level and cattle-level partitioning, respectively (Table 2). The model demonstrated better generalisation performance when the dataset was partitioned at the cattle-level. In comparison, the baseline YOLOv8n model achieved below 60% precision in both cases. These results demonstrate that the proposed MOICIA model significantly enhances recognition precision and generalisation, enabling reliable and accurate matching of individual cattle even for unseen cattle.

Table 2.

Comparison of the performance of different recognition models on the test set.

3.3. Comparison of Recognition Results from Different Network Algorithms

To validate the generalisation performance of the proposed algorithm, comparative experiments were conducted with seven other YOLO-based networks (SSD, Faster R-CNN, YOLOv5n, YOLOv6 3.0, YOLOv8n, YOLOv9s, and YOLOv10n) under the same cattle-level partitioning strategy. Each model was trained using identical hyperparameters (batch size = 16, learning rate = 0.001) for 200 epochs. Performance was evaluated using mAP, precision, recall, F1 score, and FPS metrics. In the best-performing results from a single run (Table 3), all algorithms achieved acceptable precision (above 79%), but the MOICIA model outperformed all others, achieving a precision of 97.50%, an mAP50 of 98.80%, and an inference speed of 96.9 FPS. In contrast, the baseline YOLOv8n achieved a precision of 90.85%, an mAP50 of 91.10%, and a speed of 105 FPS. Thus, MOICIA improved precision by 6.65%, mAP by 7.7%, and recall reached 100%. Despite a slight decrease in FPS, the model’s performance remained unaffected, with all other key performance metrics showing significant improvements. Among these models, SSD achieved the lowest precision, only 79.45%. Moreover, SSD and Faster R-CNN yielded the lowest FPS values, at 29 and 12.3, respectively, which makes them unsuitable for real-time identification in practical applications.

Table 3.

Comparison performance results of different network algorithms (n = 123).

To evaluate the stability of all eight models and the impact of data partitioning on model performance, a five-fold cross-validation was conducted. The averaged results show a slight reduction in both F1 and mAP50 relative to their single-run best performance. The FPS values of all algorithms were largely unaffected, remaining consistent with those of the best-performing set, as inference speed is largely independent of dataset partitioning, consistent with the expected variability across folds. Among the classical detectors, SSD achieved an average F1 of 76.3% and mAP50 of 73.8%, while Faster R-CNN performed moderately better with 82.1% and 81.3%, respectively. The YOLO family showed stronger cross-fold robustness: YOLO v5n, v6 3.0, v8n, v9s, and v10n achieved F1 scores of 87.4%, 85.5%, 89.4%, 87.2% and 87.1%, with corresponding mAP50 values of 87.5%, 85.7%, 90.3%, 87.3% and 87.6%. Among them, YOLO v8n yielded the most stable and highest accuracy within the YOLO group. The MOICIA model demonstrated the best cross-validation performance, with an average F1 of 98.4% and mAP50 of 98.5%, indicating minimal performance fluctuation across folds. These results confirm that the integration of optimised modules within the MOICIA architecture leads to significant gains in detection precision, recall, and real-time capability, establishing its superiority over existing YOLO-based approaches.

However, when evaluating generalisation using an external test set containing entirely unseen individuals, substantial performance differences emerged. MOICIA maintained strong generalisation ability, whereas the other seven models showed inaccurate localisation and frequent recognition errors under low illumination, occlusion, and high inter-individual similarity. Both Faster R-CNN and SSD exhibited a marked deterioration in performance, including missed detections, misclassification caused by occlusion, loss of targets at the frame boundaries, and confusion between visually similar individuals. YOLOv5n and YOLOv6 3.0 frequently produced incorrect or incomplete bounding boxes, especially under occlusion or low-light conditions, resulting in false detections or truncated facial regions. All seven baseline models also tended to confuse visually similar cattle, suggesting insufficient discrimination of fine-grained facial features. YOLOv8n, YOLOv9s, and YOLOv10n additionally showed reduced stability under significant lighting changes, often producing incorrect identities. Across all baseline models, occlusion remained a major challenge, leading to false positives or missed detections.

Although MOICIA did not correctly classify every unseen individual, its predictions for new cattle exhibited noticeably lower confidence (0.20–0.50), indicating appropriate uncertainty regarding unobserved identities. These errors stem from typical closed-set behavior, in which unseen individuals are forced into the closest known class. Under the adopted evaluation rule, predictions with confidence above 0.5 are treated as confident assignments to trained identities, whereas values below 0.5 are regarded as uncertain or unmatched. Among the baseline models, YOLOv8n, YOLOv9s, and YOLOv10n seldom missed detections but frequently misidentified new cattle with high confidence (0.55–0.90). In contrast, the proposed model benefited substantially from the Coordinate Attention Module, which strengthened the capture of discriminative bovine facial cues, and from the MPDIoU loss, which improved sensitivity to facial keypoint geometry and enhanced bounding-box centrality for unseen individuals. These improvements led to the expected gains in robustness and precision. For clarity, typical examples of the eight models under partial occlusion and inter-cattle similarity are compared in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Comparison of eight models for the face recognition results of cattle under partial occlusion and similar conditions for cattle.

As clearly seen in Figure 10, eight different algorithms were tested on an external test set consisting of previously unseen images of cattle, with varying predictions for cattle IDs. However, in the predictions made by the MOICIA model, two cattle that only output as “cattle face” without displaying the cattle ID label, which indicates that the model has correctly identified the cattle, as no matching cattle were found in the trained dataset. The third cattle was incorrectly recognised as cattle ID 97, but the confidence score was only 37%. Based on the previous generalisation definition, any prediction with a confidence level below 50% is considered an uncertain prediction, which is regarded as a case where the model is not confident in identifying the target cattle. Such predictions are close to the correct result. This indicates that the model exhibits strong generalisation capability, aligning with the expectations of this study. However, among the other seven models, OLOv9s and YOLOv10n showed relatively accurate detection and localization. SSD, Faster R-CNN, YOLOv5n, and YOLOv6 3.0 all missed detections, ignoring the third cattle, which was relatively far away. YOLOv8n performed relatively well, correctly predicting one cattle, but its overall performance was still unsatisfactory. Notably, when an individual cattle is incorrectly matched to a previously trained cattle with high confidence, it indicates a lack of model generalisation.

3.4. Model Validation and Ablation Analysis

To evaluate the contributions of each improvement in the proposed model, ablation experiments were performed by selectively introducing the MPDIoU loss function, and CAM. The evaluation was conducted under consistent conditions (IoU = 0.5, input size 416 × 416, confidence threshold 0.5, and non-maximum suppression threshold of 0.4). The results are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of recognition results of different improvement methods.

While neither the MPDIoU loss nor the Attention Mechanism (AM) alone achieved the optimal results, their combination in MOICIA significantly enhanced precision and speed while maintaining low computational cost. Introducing only the MPDIoU loss increased mAP50 by 5.4% (to 96.5%) and FPS from 105 to 100, reflecting a slight decrease in inference speed due to the additional computational overhead of the loss function. Incorporating only the AM improved mAP50 by 5.8% (to 96.9%) and FPS from 105 to 98, demonstrating that the attention mechanism enhanced feature representation and model performance, but it affected the inference speed and caused a slight decrease. When both the MPDIoU loss and AM were combined in the MOICIA model, it achieved 97.5% precision, 100% recall, 98.8% mAP50, and 96.9 FPS, showing the synergistic effect of these improvements. Notably, the addition of both components (MPDIoU loss and AM) resulted in a slight decrease in FPS, as expected, but the performance gains in terms of precision and recall were substantial. These results underscore the synergistic effect of the two enhancements, which together optimised both detection precision and computational efficiency.

These results indicate that the CAM effectively directs the network toward key discriminative facial regions, improving detection and classification precision, while the MPDIoU loss function enhances the bounding box regression precision and accelerates convergence. Collectively, these enhancements allow the MOICIA model to achieve superior real-time performance, stronger generalisation to complex scenarios, and improved practical deployment potential in multi-object cattle recognition systems.

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Model Recognition Performance

In this study, we proposed an improved multi-object cattle individual recognition algorithm, MOICIA, developed upon the YOLOv8n framework. By integrating the MPDIoU loss function and the CAM, the algorithm significantly enhances recognition performance in scenarios where multiple cattle faces appear simultaneously within feeding passages. The proposed model achieved an outstanding mAP50 of 98.8%, exceeding the single-cattle recognition results reported in previous studies [39,40,41,42]. The MPDIoU loss function extends traditional IoU-based regression by incorporating spatial distance and alignment penalties, thereby improving bounding-box localization precision. Experimental results demonstrated that MOICIA increased the mAP50 from 91.1% (baseline YOLOv8n) to 96.5%, reflecting substantial improvement in detecting small or partially occluded cattle faces and reducing localization errors under dense feeding conditions. These enhancements not only improve detection precision but also strengthen feature extraction quality, enabling reliable recognition in complex farm environments.

Furthermore, a CAM was introduced into the feature extraction stage before the YOLOv8 C2F module to enhance the model’s sensitivity to fine-grained visual cues. By embedding positional information along both horizontal and vertical dimensions, CAM captures long-range dependencies and focuses on discriminative facial regions while suppressing redundant background information. This selective CAM effectively reallocates focus from easily identifiable to more challenging samples, improving overall recognition robustness and precision. This finding is consistent with prior studies (Hou et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022), which demonstrated that coordinate attention outperforms SE or CBAM modules in fine-grained recognition tasks [43,44]. The integration of CAM led to a notable increase in the F1-score from 93.55% to 96.50%, reducing misclassification among visually similar individuals.

The proposed MOICIA model also achieved an average inference time of 0.0103 s per image, confirming its suitability for real-time multi-animal recognition in intelligent livestock monitoring. To assess model generalisation, two dataset partitioning strategies, image-level and cattle-level, were compared. While image-level partitioning yielded marginally higher apparent precision, the cattle-level strategy demonstrated superior generalisation on unseen individuals, consistent with Li et al. (2023) [45]. This confirms that individual-level partitioning effectively prevents overfitting to specific samples and promotes learning of generalisable morphological traits [46]. Therefore, when practical deployment and generalisation are prioritised, cattle-level partitioning should be preferred. Notably, image-level random partitioning can lead to overestimated performance when evaluated on unseen samples [33].

Compared with the method of Andrew et al. [47], the proposed approach achieved higher mAP values despite addressing a more complex task, simultaneous recognition of multiple cattle within confined feeding passages. This further demonstrates the robustness and practical applicability of MOICIA in realistic multi-target recognition scenarios.

4.2. Analysis of Environmental Factors in Multi-Object Cattle Individual Recognition

Despite the high recognition precision, real-world farming conditions still impose significant challenges on multi-object cattle recognition. In feeding troughs, high density, narrow spaces, and frequent interactions often cause occlusion and crowding, leading to missed or false detections [47]. Furthermore, lighting variations (e.g., day–night transitions, artificial illumination, shadows, and reflections) and facial contamination (e.g., dirt, feed residue, or splashes) can obscure discriminative facial and texture features, reducing recognition precision.

The results show that although environmental factors such as occlusion, crowding, minor inter-individual variation, illumination change, and contamination remain major constraints, enhancing the model mitigates their effects. The proposed model demonstrates higher robustness and reliability under visually degraded conditions compared with conventional detection networks. Given that the dataset and experimental conditions closely reflect practical feeding environments [42], these results confirm the real-world deployment potential of the MOICIA algorithm.

By contrast, Andrew et al. (2021) achieved 93.8% recognition precision using a deep metric learning framework in open pastures with minimal occlusion [48], while Wang et al. (2024) reached 94.58% precision under controlled partial-occlusion settings using attention and spatial transformation modules [40]. The present work achieved higher adaptability under more challenging, dense, and visually cluttered feeding-passage scenarios, further validating the effectiveness of MOICIA in realistic farm applications.

4.3. Limitations and Future Work

Although the MOICIA framework substantially improves multi-cattle face detection and recognition through enhanced localization precision and feature robustness, several limitations remain. The model currently relies on limited training samples (few-shot learning), which constrains generalisation across dynamic farm environments where lighting, occlusion, and background complexity vary over time.

Future research will focus on enhancing adaptability and scalability through several strategies: (1) Incremental learning to continuously update model parameters as new data (e.g., seasonal or individual growth changes) become available [49,50]; (2) Incorporation of temporal cues from video sequences to improve tracking continuity and identity persistence; (3) Integration of multi-modal sensing, including depth, hyperspectral, or thermal imaging, to enhance robustness under low-visibility or extreme lighting conditions; (4) Lightweight model design and compression to facilitate deployment on edge devices for real-time on-farm applications.

In conclusion, the proposed MOICIA algorithm demonstrates excellent robustness, high precision, and real-time capability for multi-object cattle face recognition in realistic farm conditions. However, continued optimization in image preprocessing, feature representation, environmental adaptation, and sensor fusion remains essential to achieve fully automated and reliable livestock recognition for precision farming.

5. Conclusions

This study presents an enhanced deep learning framework, MOICIA, for multi-object cattle face recognition under complex feeding-passage environments. By integrating the MPDIoU loss function with a CAM within the YOLOv8n framework, the model effectively improves detection precision, localization precision, and feature robustness in dense and occluded scenarios. Experimental results demonstrated that MOICIA achieved an mAP50 of 98.8%, an F1-score of 98.73%, and an average inference time of 0.0103 s per image, exhibiting precision that outperforms existing YOLO-based deep metric learning approaches. The CAM enabled the network to capture fine-grained spatial dependencies and focus on discriminative facial regions, reducing misclassification among visually similar individuals. The optimised IoU-based loss function enhanced bounding-box alignment and stability, improving overall recognition precision. Furthermore, the comparative analysis between image-level and cattle-level partitioning confirmed that cattle-level division provides superior generalisation to unseen individuals, aligning better with real-world deployment requirements. Despite these advances, limitations persist due to the model’s dependence on a few-shot training samples and sensitivity to extreme illumination or severe occlusion. Future research will explore incremental learning for adaptive updates, temporal feature fusion for identity tracking, and multimodal sensing (e.g., depth or thermal imaging) to enhance recognition reliability under diverse environmental conditions. In addition, lightweight model compression will facilitate deployment on edge devices for on-farm real-time applications. Overall, the proposed MOICIA algorithm demonstrates high robustness, precision, and practical potential for intelligent livestock management. Its integration into precision farming systems could enable automated cattle monitoring, behavioral assessment, and health management, contributing to the development of sustainable and welfare-oriented smart farming.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z. and W.W.; methodology, W.Z.; software, W.Z.; validation, W.Z., S.S., and Y.W.; formal analysis, W.Z.; investigation, S.S. and X.C.; resources, W.W.; data curation, W.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Z.; writing—review and editing, W.W. and Y.W.; visualization, W.Z.; supervision, W.W.; project administration, X.C.; funding acquisition, W.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research and Development Program of Xinjiang Autonomous Region, grant number [2023B02013-2].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to two private housing farms in Jiangxi Province and Henan Province, China, for their kind support with data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this paper.

References

- Xu, B.; Wang, W.; Guo, L.; Chen, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y. Evaluation of Deep Learning for Automatic Multi-View Face Detection in Cattle. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, E.; Hernández-Jover, M.; Newman, R.; Holyoake, P. Assessment of acute pain experienced by piglets from ear tagging, ear notching and intraperitoneal injectable transponders. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2010, 127, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Guo, L.; Falzon, G.; Kwan, P.; Jin, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, W. Analysis and Comparison of New-Born Calf Standing and Lying Time Based on Deep Learning. Animals 2024, 14, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mücher, S.; Wang, W.; Guo, L.; Kooistra, L. A review of three-dimensional computer vision used in precision livestock farming for cattle growth management. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 206, 107687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aziz, A.S.; Hassanien, A.E.; Azar, A.T.; Hanafi, S.E.-O. Machine learning techniques for anomalies detection and classification. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Security of Information and Communication Networks, Sydney, Australia, 25–27 September 2013; pp. 219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Giot, R.; El-Abed, M.; Rosenberger, C. Fast computation of the performance evaluation of biometric systems: Application to multibiometrics. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2013, 29, 788–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestal, M.K.; Ward, C.E.; Doye, D.G.; Lalman, D.L. Beef cattle production and management practices and implications for educators. Agecon Search 2006, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, S.K.; Dutta, T.; Gupta, H.P. A fast cattle recognition system using smart devices. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 15–19 October 2016; pp. 742–743. [Google Scholar]

- Scordino, J. Steller Sea Lions (Eumetopias jubatus) of Oregon and Northern California: Seasonal Haulout Abundance Patterns, Movements of Marked Juveniles, and Effects of Hot-Iron Branding on Apparent Survival of Pups at Rogue Reef. Master’s Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stanford, K.; Stitt, J.; Kellar, J.A.; McAllister, T.A. Traceability in cattle and small ruminants in Canada. Rev. Sci. Tech. L OIE. 2001, 20, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.T.; Choi, H.L.; Lee, D.W.; Yoon, Y.C. Recognition of Individual Holstein Cattle by Imaging Body Patterns. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 18, 1194–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Truman, M.; Sukkarieh, S. Cattle segmentation and contour extraction based on Mask R-CNN for precision livestock farming. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 165, 104958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, A.M.; Edwards, D.S. Welfare implications of identification of cattle by ear tags. Vet. Rec. 1996, 138, 612–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.T.; Ikeda, Y.; Choi, H.L. The Identification of Japanese Black Cattle by Their Faces. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 18, 868–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.G. Object recognition from local scale-invariant features. In Proceedings of the Seventh IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Kerkyra, Greece, 20–27 September 1999; Volume 2, pp. 1150–1157. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, B.; Gonzales-Barron, U.A.; McDonnell, K.; Butler, F.; Ward, S. Using muzzle pattern recognition as a biometric approach for cattle identification. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittier, J.C.; Doubet, J.; Henrickson, D.; Cobb, J.; Shadduck, J.; Golden, B.L. Biological considerations pertaining to use of the retinal vascular pattern for permanent identification of livestock. In Proceedings of the American Society of Animal Science Western Section, Phoenix, Arizona, 28–29 March 2003; Volume 54, pp. 339–344. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, J.; He, Y.; Yang, H.; Connor, T.; Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Zheng, B.; et al. Identification of animal individuals using deep learning: A case study of giant panda. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 242, 108414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Hu, Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Kuang, Y.; Gao, Y. Cow face detection and recognition based on automatic feature extraction algorithm. In Proceedings of the ACM Turing Celebration Conference—China, Chengdu, China, 17–19 May 2019; p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Z.; Meng, F.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Gong, C. Cattle face recognition based on a Two-Branch convolutional neural network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 196, 106871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qin, J.; Hou, Q.; Gong, S. Cattle Face Recognition Method Based on Parameter Transfer and Deep Learning. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1453, 012054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.; Bindelle, J.; Gu, X. Non-contact respiration rate measurement of multiple cows in a free-stall barn using computer vision methods. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 218, 108678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Jin, X.; Ji, J.; Wang, J.; Ma, H.; Zhu, X. Individual identification of Holstein dairy cows based on detecting and matching feature points in body images. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 181, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Wang, W.; Guo, L.; Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Cao, Z.; Wu, S. CattleFaceNet: A cattle face identification approach based on RetinaFace and ArcFace loss. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 193, 106675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Li, J. Cattle face recognition using local binary pattern descriptor. In Proceedings of the 2013 Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference, Kaohsiung, China, 29 October–1 November 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.; Wu, Q.; Yin, X.; Wu, D.; Song, H.; He, D. FLYOLOv3 deep learning for key parts of dairy cow body detection. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 166, 104982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Zhu, H.; Luo, L.; Li, H.; Hu, T.; Guo, Y.; Mu, Y. GFI-YOLOv8: Sika Deer Posture Recognition Target Detection Method Based on YOLOv8. Animals 2024, 14, 2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Dong, Y.; Xia, Y.; Xu, D.; Xu, F.; Chen, F. Wildlife Real-Time Detection in Complex Forest Scenes Based on YOLOv5s Deep Learning Network. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Li, C.; Yang, P.; Kong, S.; Han, Y.; Huang, X.; Niu, J. Enhancing Livestock Detection: An Efficient Model Based on YOLOv8. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, G.; Zhang, S.; Mao, W.; Zhang, M. YOLO-SAG: An improved wildlife object detection algorithm based on YOLOv8n. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 83, 102791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Zhou, X.; Gao, J.; Wang, Z.; Naer, A.; Hai, L.; Alatan, S.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z. YOLOv8-CBAM: A study of sheep head dentification in Ujumqin sheep. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1514212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russello, H.; van der Tol, R.; Kootstra, G. T-LEAP: Occlusion-robust pose estimation of walking cows using temporal information. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 192, 106559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Siegford, J.; Colbry, D.; Lesiyon, R.; Bosgraaf, A.; Chen, C.; Norton, T.; Steibel, J.P. Evaluation of computer vision for detecting agonistic behavior of pigs in a single-space feeding stall through blocked cross-validation strategies. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 204, 107520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hong, D.; Wu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, X.; Luo, H. Sheep-YOLO: Improved and lightweight YOLOv8n for precise and intelligent recognition of fattening lambs’ behaviors and vitality statuses. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 236, 110413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Liu, T.; Wang, H.; Hasi, B.; Yuan, C.; Gao, F.; Shi, H. Using Pruning-Based YOLOv3 Deep Learning Algorithm for Accurate Detection of Sheep Face. Animals 2022, 12, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hua, Z.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xu, X.; Song, H. E-YOLO: Recognition of estrus cow based on improved YOLOv8n model. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Yan, R.; Jiang, C.; Chand, N.V.; Bai, T.; Guo, L.; Qi, J. Grazing sheep behaviour recognition based on improved yolov5. Sensors 2023, 23, 4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Dai, B.; Hu, Y.; Dai, X.; Fang, J.; Yin, Y.; Liu, H.; Shen, W. Multi-behavior detection of group-housed pigs based on YOLOX and SCTS-SlowFast. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 225, 109286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Fang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y. Research on cattle behavior recognition and multi-object tracking algorithm based on yolo-bot. Animals 2024, 14, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Li, X.; An, X.; Duan, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Qi, J. Open-set recognition of individual cows based on spatial feature transformation and metric learning. Animals 2024, 14, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Burghardt, T.; Dowsey, A.W.; Campbell, N.W. MultiCamCows2024--A Multi-view Image Dataset for AI-driven Holstein-Friesian Cattle Re-Identification on a Working Farm. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.12695. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, X.; Mao, T.; Li, Y.; Liu, G. Individual Recognition of a Group Beef Cattle Based on Improved YOLO v5. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate Attention for Efficient Mobile Network Design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13713–13722. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, H. Fine-Grained Pig Face Recognition Using Attention-Augmented Convolutional Networks. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107078. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, Z. Individual-Level Data Partitioning Improves the Generalization of Deep Models for Livestock Identification. Animals 2023, 13, 892. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Tang, X. Deeply Learned Face Representations Are Sparse, Selective, and Robust. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2018, 126, 292–313. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, W.; Gao, J.; Mullan, S.; Campbell, N.; Dowsey, A.W.; Burghardt, T. Visual identification of individual Holstein-Friesian cattle via deep metric learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 185, 106133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Sun, J.; Guan, M.; Sun, S.; Shi, G.; Zhu, C. A New Method for Non-Destructive Identification and Tracking of Multi-Object Behaviors in Beef Cattle Based on Deep Learning. Animals 2024, 14, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, F.M.; Marín-Jim’enez, M.J.; Guil, N.; Schmid, C.; Alahari, K. End-to-end incremental learning. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Ye, Y.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Fu, Y. Large scale incremental learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).