Abstract

In the era of smart agriculture, intelligent fruit maturity detection has become a critical task. However, in complex orchard environments, factors such as occlusion by branches and leaves and interference from bagging materials pose significant challenges to detection accuracy. To address this issue, this study focuses on maturity detection of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates and proposes an improved YOLO-AMAS algorithm. The method integrates an Adaptive Feature Enhancement (AFE) module, a Multi-Scale Convolutional Attention Module (MSCAM), and an Adaptive Spatial Feature Fusion (ASFF) module. The AFE module effectively suppresses complex backgrounds through dual-channel spatial attention mechanisms; the MSCAM enhances multi-scale feature extraction capability using a pyramidal spatial convolution structure; and the ASFF optimizes the representation of both shallow details and deep semantic information via adaptive weighted fusion. A SlideLoss function based on Intersection over Union is introduced to alleviate class imbalance. Experimental validation conducted on a dataset comprising 6564 images from multiple scenarios demonstrates that the YOLO-AMAS model achieves a precision of 90.9%, recall of 86.0%, mAP@50 of 94.1% and mAP@50:95 of 67.6%. The model significantly outperforms mainstream detection models including RT-DETR-1, YOLOv3 to v6, v8, and 11 under multi-object, single-object, and occluded scenarios, with a mAP50 of 96.4% for bagged mature fruits. Through five-fold cross-validation, the model’s strong generalization capability and stability were demonstrated. Compared to YOLOv8, YOLO-AMAS reduces the false detection rate by 30.3%. This study provides a reliable and efficient solution for intelligent maturity detection of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates in complex orchard environments.

1. Introduction

Pomegranate fruit is abundant in nutrients and offers benefits such as anti-inflammatory and anti-aging properties, immunity enhancement, and prevention of cardiovascular diseases, thereby driving the rapid development of the pomegranate industry [1]. As a superior local variety in southern Shanxi Province [2], the ‘Jiang’ pomegranate boasts a lengthy cultivation history in Linyi County and is recognized as a China Nationally Important Agricultural Heritage System [3]. Its fruit quality is well-received in the market, making it a key element of the local specialty agriculture sector [4]. The climate in Linyi County is conducive to the growth of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates; however, the trees have low cold tolerance, and fruit development requires temperatures above 20 °C [5]. Bagging, which aids in increasing sugar accumulation in the arils and guards against pest harm, has become a mainstream cultivation technique [6]. However, bagging introduces additional optical interference in complex orchard environments. White polyethylene film tends to generate strong reflections and highlight spots, leading to localized overexposure and reduced contrast, which subsequently obscures edge details and causes false or missed detections [7]. Furthermore, the paper bag material closely resembles the color of semi-mature ‘Jiang’ pomegranates, further complicating automated visual inspection.

In recent years, deep-learning-based object detection methods with automatic feature extraction have been extensively applied to pomegranate detection. Among various deep learning architectures, the YOLO framework has emerged as a predominant approach in agricultural vision tasks, with numerous studies focusing on optimizing network structures and compressing model parameters to enhance detection accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency. Representative advancements include: the YOLO-MSNet proposed by Xu and Liang et al. boosted mAP@50 by 1.7%, while reducing the number of parameters and model size by 21.5% and 21.8%, respectively, rendering it more appropriate for resource-constrained devices compared to YOLOv11 [8]. Wang J et al. developed PG-YOLO based on YOLOv8, which attained an mmAP@50 of 93.4%, with a model weight of only 2.2 MB, a size reduction of 89.9% compared to the original YOLOv8s and a 74.1% enhancement in detection speed [9]. Du Y et al. presented TP-YOLO, which reached an average precision of 94.4%, with a model size of 1.9 MB and a 67.9% reduction in parameters [10]. Zhao J et al. proposed YOLO-Granadam, an improved version based on YOLOv5, which accomplished an average accuracy of 92.2%, enhanced the detection speed by 17.3%, and compressed the parameter count, FLOPs, and model size to 54.7%, 51.3%, and 56.3% of the original network, respectively [11]. Rupa and NB contrasted YOLOv5 and YOLOv8, discovering that YOLOv8 improved mAP@50 by 2.6%, and both models could accurately identify mature fruits [12]. However, existing research has mainly concentrated on pomegranate detection without bagging or in simple environments, neglecting to fully take into account the optical interference caused by bagging in practical production. Moreover, there is still a deficiency in adaptability research for complex orchard conditions, rendering it challenging to directly meet the practical requirements for maturity detection of bagged pomegranates.

Addressing the research gap in maturity detection of bagged ‘Jiang’ pomegranates in complex orchard environments, this study aims to address core challenges such as optical interference from bagging and the impact of complex environmental factors, and undertakes innovative exploration on accurate maturity detection methods for bagged ‘Jiang’ pomegranates. Bagging treatment was applied to ‘Jiang’ pomegranates at the onset of the coloring stage, following the fruit-setting period. A mixed dataset was constructed by collecting fruit images from initial fruit set to maturity, comprising both non-bagged and bagged samples. The model incorporates an Adaptive Feature Enhancement (AFE) module, which improves the resilience to complex backgrounds through dynamic channel weighting and spatial attention mechanisms. A Multi-Scale Convolutional Attention Module (MSCAM) is introduced to leverage multi-branch dilated convolutions and channel attention mechanisms, the MSCAM enhances the model’s multi-scale feature extraction capability, suppresses information from irrelevant regions, and successfully captures salient multi-scale features. Furthermore, an Adaptive Spatial Feature Fusion (ASFF) module is integrated to integrate features at different levels and optimize multi-scale feature representation through learnable weights, thereby enhancing the localization accuracy of small objects in distant scenes. In response to the morphological variability and significant maturity variation of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates, the training dataset was expanded with complex scenarios such as occlusion by branches and leaves and fruit overlapping, boosting the model’s adaptability to intricate orchard conditions. The SlideLoss function was adopted to optimize the bounding box regression process, further enhancing the model’s adaptability and generalization under varying lighting, occlusion, and background conditions. Ultimately, effective and precise maturity detection of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates in complex orchard scenarios was achieved.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Image Acquisition

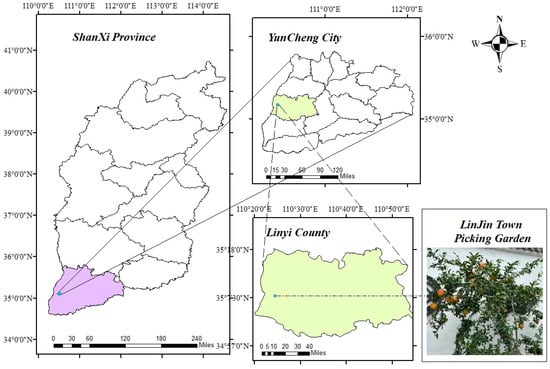

The experimental data for this study were collected in Linjin Town, Linyi County, Yuncheng City, Shanxi Province (35°05′ N, 110°33′ E), specifically at the Linjin Jiang Pomegranate Sightseeing and Picking Manor. It was the ‘Jiang’ pomegranate that served as the research subject. The experimental site is shown in the following Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Experimental site.

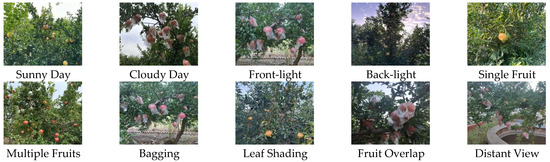

To facilitate the analysis of the characteristics of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates in complex orchard environments, image data were acquired using an iPhone 14 Pro smartphone under various time periods, angles, and orientations. The iPhone 14 Pro used in this study was sourced from Apple Inc. (Cupertino, CA, USA). The device was assembled by Foxconn in Zhengzhou, Henan, China, or in India. The collection period spanned from September to November 2024, covering three growth stages: initial fruit setting, fruit development, and maturity [13]. Images were captured at distances ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 m. A total of 5645 images of bagged and non-bagged ‘Jiang’ pomegranates were collected, each with a resolution of 3024 × 4032 pixels in JPEG format. The complex orchard conditions included front-light, back-light, overcast weather, single fruit, multiple fruits, close-up, long-distance, fruit overlapping, Bagging, and occlusion by branches and leaves. Representative sample images are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Sample Images of ‘Jiang’ Pomegranate under Complex Orchard Environment.

2.2. Data Augmentation

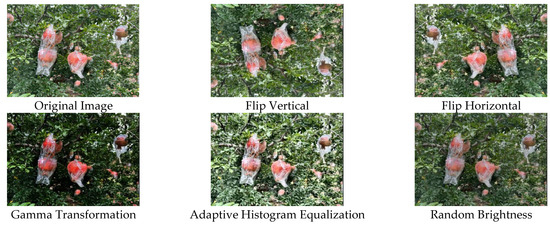

Due to various unpredictable factors such as lighting and weather conditions, the acquired image samples exhibited an uneven distribution, with insufficient samples under certain scenarios. The adequacy of the image dataset is of critical importance during model training. Insufficient training images can lead to overfitting, thereby compromising the rigor and accuracy of experimental results. Effectively addressing the scarcity of data under specific complex conditions helps mitigate model bias toward certain categories and reduces the risk of overfitting [14].

In order to enhance the robustness and generalization ability of the ‘Jiang’ pomegranate object detection model, data augmentation was applied to the samples. This study employed methods such as vertical flipping, horizontal flipping, gamma transformation, adaptive histogram equalization, and random brightness adjustment to enhance image contrast, with augmentation applied solely to the training dataset. After augmentation, the collected image data underwent systematic curation, and non-compliant samples were removed, ultimately yielding a total of 6564 sample images, among which 2996 were images of Jiang pomegranates that had undergone bagging treatment, and 3568 were images of Jiang pomegranates without bagging treatment. The final dataset was partitioned into a training set comprising 5245 images, a validation set with 676 images, and a test set containing 643 images, the ratio is 8:1:1. The specific exclusion criteria included: images that could not be annotated due to blurriness exceeding the acceptable range for manual labeling; images with excessively low or high brightness and severely imbalanced contrast, rendering target structures unidentifiable; images where the detection target was occluded by non-target objects by more than 30% of its own area. Examples of the data augmentation techniques are illustrated in the following Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Data Enhanced Picture Type.

2.3. Dataset Construction

The ‘Jiang’ pomegranate fruits in the images were manually annotated with the help of the open-source software LabelImg (v1.8.6).The annotation bounding boxes were drawn as minimum enclosing rectangles around the fruits in order to minimize interference from the background in object detection. Taking into account fruit maturity, the target ‘Jiang’ pomegranates were categorized into three classes: immature, semi-mature, and mature. This study conducted research by searching for relevant studies [15] and visiting pomegranate growers, the target ‘Jiang’ pomegranates were categorized into three classes: immature (G), semi-mature (GR), and mature (R). The annotation criteria were defined as follows: Fruits with coloring coverage exceeding 80% or fully red without green were labeled as mature; those with coloring coverage below 80% were labeled as semi-mature; and fruits exhibiting green coloration were labeled as immature. The annotations were stored in the commonly used TXT format files. There were a total of 6591 immature fruits, 15,384 semi-mature fruits, and 8751 mature fruits.

2.4. Pomegranate Maturity Detection Model Construction

2.4.1. Improved YOLOv8 Architecture

The YOLOv8 architecture mainly consists of three parts: a backbone network, a neck network, and a detection head. The backbone employs an improved CSPDarknet53, which integrates Cross-Stage Partial modules and C2f structures aiming to reduce computational cost while enhancing feature reuse capability. Additionally, an SPPF module is also incorporated to improve multi-scale feature perception. The neck network, which utilizes a PAN-FPN structure, enables efficient feature fusion through bidirectional cross-scale connections and significantly improves small object detection performance. The detection head adopts a decoupled design, which separates classification and regression tasks. It also uses an anchor-free mechanism to directly predict object center points and dimensions, simplifying the training process. The model training employs a dynamic label assignment strategy, and combines CIoU Loss to optimize bounding box regression, and uses VFL Loss to alleviate class imbalance, thereby comprehensively improving detection accuracy and robustness [16].

However, YOLOv8 exhibits insufficient adaptability in complex orchard environments. During the feature extraction stage, although the C2f module maintains gradient flow through cross-layer connections, its capacity for learning discriminative features against interference factors such as foliage occlusion and reflective fruit bags is limited, resulting in the attenuation of key fruit feature responses amid complex background noise [17]. At the multi-scale feature fusion level, while the FPN-PAN structure enables bidirectional fusion of feature pyramids, its representation of small-scale fruit targets remains inadequate, as shallow localization information tends to be diluted during deep semantic feature integration, leading to missed detections of distant or densely clustered small fruits [18]. In the detection head, the CIoU loss function demonstrates suboptimal performance when handling highly overlapping fruit instances, struggling to effectively distinguish boundary regions between adjacent targets and causing incorrect suppression of detection boxes by non-maximum suppression [19]. These structural limitations collectively constrain the model’s detection robustness and accuracy in complex orchard environments.

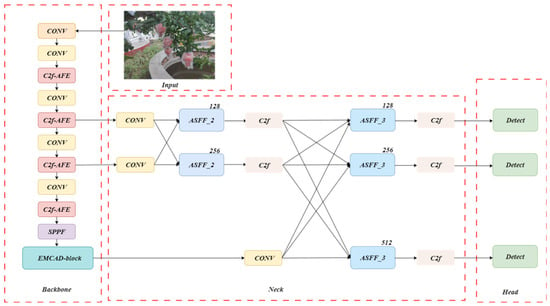

This study proposes a YOLO-AMAS model for detecting ‘Jiang’ pomegranates at varying maturity levels in complex orchard environments. Based on the YOLOv8 architecture, the model incorporates improvements through the integration of an Adaptive Feature Enhancement (AFE) module, a Multi-Scale Convolutional Attention (MSCAM) module, and an Adaptive Spatial Feature Fusion (ASFF) module. The model employs an AFE module to suppress complex background noise, utilizes an MSCAM to perceive context for occlusion handling, leverages an ASFF module to optimize multi-scale feature fusion, and incorporates SlideLoss to balance category influences. Collectively, these enhancements elevate detection accuracy and robustness for ‘Jiang’ pomegranates within intricate environments.

Specifically, the AFE module, which is embedded in the backbone network, enhances robustness to complex backgrounds through dynamic channel weighting and spatial attention mechanisms, while maintaining a lightweight structure to control computational costs. At the feature fusion stage, leveraging multi-branch dilated convolutions and channel attention mechanisms, the MSCAM enhances the model’s multi-scale feature extraction capability, suppresses information from irrelevant regions, and successfully captures salient multi-scale features. Simultaneously, the ASFF module adaptively integrates features from different levels and optimizes multi-scale feature representation through learnable weights, significantly improving localization accuracy for small objects in distant views. In response to the morphological diversity and significant maturity variation of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates, data augmentation methods such as rotation and random gamma transformation were applied during training. The SlideLoss function was adopted to optimize the bounding box regression process, which further enhances the model’s adaptability and generalization under varying lighting, occlusion, and background conditions. Together with the preceding three modules, it forms a unified improvement framewor. In conclusion, efficient and accurate maturity detection of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates in complex orchard scenarios was achieved. The structure of the improved YOLO-AMAS maturity detection model is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

YOLO-AMAS Model Structure.

2.4.2. AFE Module

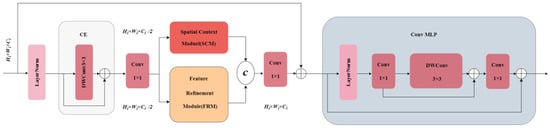

To address the inadequate capability of YOLOv8 in learning discriminative features against interference factors such as foliage occlusion and reflective bagging materials in complex orchard environments, this paper adopts an Adaptive Feature Enhancement (AFE) module to enhance the model’s feature extraction capability [20]. The structure of the AFE module is depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

AFE Module Structure.

Embedded in the shallow feature layers, the module mitigates conflicts between semantic and detailed information during cross-scale fusion through dynamic weight adjustment and channel attention mechanisms, while suppressing interference from redundant channels. To address feature confusion caused by dense fruit occlusion, the input features first undergo LayerNorm and channel compression, enhancing edge contour channels of occluded fruits and suppressing blurry noise generated by overlapping adjacent fruits.

To resolve the frequency-domain coupling problem between plastic bag reflection and fruit contours on bagged fruits, the compressed features are subsequently fed into the Spatial Context Module (SCM) and Feature Refinement Module (FRM): the SCM employs large-kernel 7 × 7 group convolutions to expand the receptive field and capture broader spatial contextual information; the FRM performs downsampling and smoothing through depthwise convolution, followed by upsampling to extract high-frequency details R and low-frequency components S, which are then concatenated along the channel dimension and output as refined features through a projection layer. The outputs of SCM and FRM are concatenated along the channel dimension, fused via 1 × 1 convolution, and input to ConvMLP for further feature representation enhancement, adapting to detection requirements of fruits of different sizes and ultimately improving the model’s semantic segmentation performance in complex scenarios.

2.4.3. MCSAM Module

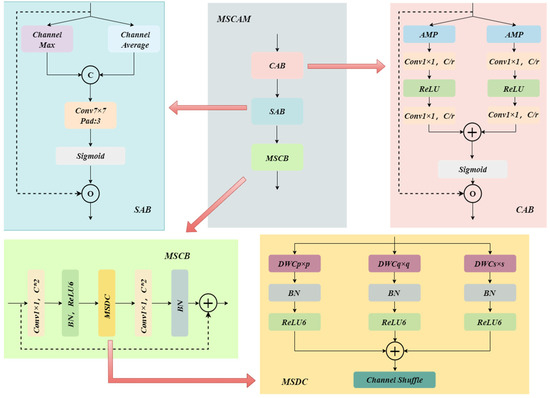

To address the limitations of multi-scale feature fusion in the Feature Pyramid Network of the YOLOv8 model, this paper adopts a multi-scale Convolutional Attention Module (MSCAM). This module operates on the deep feature layers and leverages the synergy between multi-scale convolution and dual attention mechanisms to tackle specific challenges in detecting bagged ‘Jiang’ pomegranates: high reflectivity interference from bagging materials, blurred boundaries between dense fruits, and incomplete target structures caused by severe foliage occlusion. The structure of the MSCAM is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

MSCAM Structure. In Figure 6, the three arrows of MSCAM respectively point to the modules CAB, SAB, and MSCB, and the arrow within the MSCB module further points to the MSDC module.

The MSCAM consists of three core components that enhance feature discriminability from different dimensions [21]. The Channel Attention Block (CAB) extracts channel statistics through parallel global average pooling and global max pooling, generates channel weights via a bottleneck structure composed of two fully connected layers, and achieve adaptive calibration for each channel via the sigmoid function. This module effectively suppresses channel response noise induced by bagging material reflections while enhancing responses in channels relevant to the fruit’s substantial features, thereby improving the model’s perception of key ‘Jiang’ pomegranate characteristics under complex optical interference. The structure of CAB is shown in Figure 6.

The Spatial Attention Block (SAB) performs both average pooling and max pooling along the channel dimension on the input features, concatenates the resulting features, and processes them through a convolutional layer to generate a spatial attention map. Spatial weight assignment is then accomplished via a Sigmoid function. This design enables the model to adaptively focus on visible regions of partially occluded fruits and individual instances within dense fruit clusters, significantly enhancing target localization robustness under overlapping and occluded conditions. The structure of SAB is shown in Figure 6.

The Multi-Scale Convolution Block (MSCB) employs depthwise convolutional layers with different kernel sizes in parallel to capture diverse features ranging from local details to global context. Its internal Multi-Scale Depthwise Convolution (MSDC) structure simultaneously captures multi-resolution features of both nearby large fruits and distant small fruits, effectively handling the significant scale variations of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates in orchard environments. Through feature fusion, it provides rich multi-scale feature representations for subsequent attention modules. The structure of the MSCB is shown in Figure 6, and the structure of the MSDC is also illustrated in Figure 6.

2.4.4. ASFF Module

To address the issues of cross-scale feature semantic misalignment and fixed fusion weights in multi-scale feature fusion within the Feature Pyramid Network of the YOLOv8 model, this paper adopts an Adaptive Spatial Feature Fusion module for improvement. While the traditional PANet structures fuse features from different levels through static concatenation or additive operations, a process that frequently induces semantic conflicts and redundant information interference. In contrast, the ASFF module dynamically calibrates feature response strengths via a spatially adaptive weight learning mechanism, thereby achieving precise alignment and fusion of multi-scale features [22]. The structure of the ASFF module is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

ASFF Module Structure.

In this study, the ASFF module is implemented for dynamic optimization as follows: first, channel compression via 1 × 1 convolution is applied to the P3, P4, and P5 level features output from the backbone network, completing feature preprocessing. Subsequently, the ASFF_2 module is deployed between adjacent levels P3 and P4, where spatial resolution is unified through 2× upsampling alignment, and a spatial weight map generated by a 1 × 1 convolution adaptively assigns fusion weights to local details and medium level semantics, thereby enhancing boundary localization capability for dense objects. For cross-level fusion spanning P3 to P5, the ASFF_3 module is employed, which unifies the three level features via 4× upsampling alignment and utilizes a 3 × 3 convolution to produce multi-channel weight maps. This mechanism dynamically balances the contributions of local details, medium-level semantics, and global context, effectively addressing detection consistency issues in scenes with drastic scale variations. ASFF module significantly improves the model’s adaptability to complex scenarios while maintaining inference efficiency, demonstrating superior performance particularly in dense object detection and environments with substantial scale variations.

2.5. Loss Function

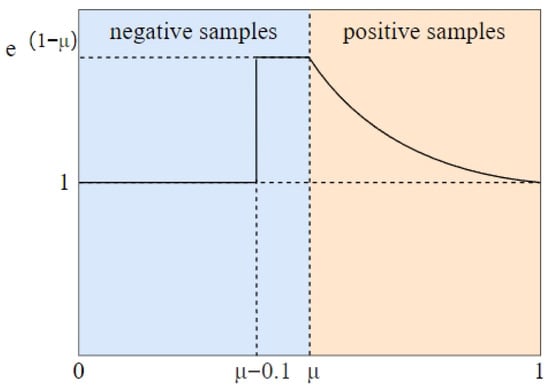

In the YOLOv8 object detection framework, the accuracy of bounding box regression is vital for target localization performance. The original model utilizes the CIoU loss function, which improves basic localization performance by integrating overlap area, center point distance, and aspect ratio. However, it is still plagued by gradient imbalance between positive and negative samples: the uniform weighting scheme allows high IoU positive samples to dominate the training process, while low IoU negative samples make inadequate contributions to gradients. This not only slows down model convergence but also leads to evaluation bias due to overfitting on positive samples. In the task of ‘Jiang’ pomegranate detection, the issue of sample imbalance is particularly pronounced. Specifically, in the context of densely foliated and complex orchard environments, background areas far exceed in number pomegranate targets, causing the model to incorrectly classify background as fruit. Meanwhile, small-sized or heavily occluded pomegranates are difficult to detect correctly due to indistinct features, whereas large, clear targets are numerous and dominate the training process, further aggravating category and difficulty imbalance. To address these issues, this study adopts a SlideLoss dynamic weighting mechanism to replace the original CIoU loss [23]. This strategy designs an adaptive weighting mechanism based on IoU thresholds by using the average IoU value of all bounding boxes as the threshold μ [24]. The experimental setting value is 0.5. Its formula is defined as Equation (1).

For each prediction-target pair with IoU x,when the IoU value x of a prediction-target pair is less than μ − 0.1, the weight remains at 1 to reflect its status as negative samples. For negative samples with IoU values x falling between μ and μ − 0.1, the weight is increased to e1−μ to enhance their training priority; whereas when the IoU value x is greater than μ, the weight decreases exponentially according to e1−x to suppress the excessive dominance of positive samples [25]. Figure 8 shows the schematic of Slide Loss.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of Slide Loss.

2.6. Experimental Environment Configuration and Network Parameter Settings

The experiments were conducted on a system running the Windows 11 operating system, equipped with an Intel (R) Xeon (R) Platinum 8270 CPU @ 2.70 GHz, an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090D GPU, 128 GB of RAM, and a 30 TB mechanical hard drive. The programming language used was Python 3.9, with PyTorch 2.2.0 as the deep learning framework and CUDA 11.8 as the GPU acceleration library. The detailed hyperparameters of the experiment are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

detailed hyperparameters of the experiment.

2.7. Model Evaluation Metrics

In the evaluation of model performance, the following metrics were selected in multiple dimensions including detection accuracy, computational efficiency, and generalization capability. For detection accuracy, precision (P), recall (R), and mean average precision (mAP) were used to thoroughly assess localization and classification performance.mAP@50 denotes the mean average precision at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5, reflecting the model’s detection accuracy under relaxed matching conditions; mAP@50-95 denotes the average mAP across IoU thresholds incremented from 0.5 to 0.95 in 0.05 increments, reflecting the model’s comprehensive detection accuracy across varying matching stringency levels. In terms of inference efficiency, the average detection time (ADT) was adopted to demonstrate the model’s practical deployment performance [26]. To assess computational complexity, the number of giga floating-point operations per second (GFLOPs) was employed to gauge the forward computation burden [27]. For assessing maturity category discrimination capability, the False Detection Rate (FD Rate) was employed to quantify the proportion of misclassified maturity categories [28].

3. Experimental Results Analysis

3.1. YOLO-AMAS Experimental Results

To evaluate the performance of the YOLO-AMAS model, 643 images of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates from the test set were evaluated. The detection results of the suggested model across different maturity levels are presented in Table 2. As shown in the table, the mAP@50 values for immature, semi-mature, and mature ‘Jiang’ pomegranates attained 91.8%, 94.2%, and 96.4%, respectively. The overall P, R, mAP@50 and mAP@50:95 for detecting targets at different maturity levels were 90.9%, 86.0%, 94.1% and 67.6%, indicating commendable detection performance.

Table 2.

Test results of YOLO-AMAS model.

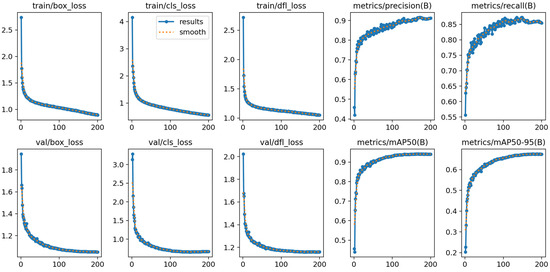

The results of model training and evaluation are shown in Figure 9. As observed in the subfigures, both training and validation loss values decreased consistently, while metrics such as precision, recall, and mean average precision continued to rise, demonstrating a progressive optimization of model performance. The similar trends in training and validation loss curves indicate the absence of overfitting and reflect strong generalization capability. The stabilization of metrics in the later stages confirms that the model has converged with satisfactory performance.

Figure 9.

Model training and evaluation result diagram.

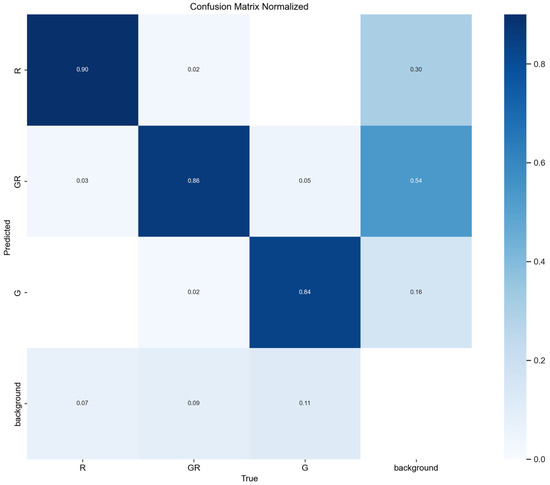

The normalized confusion matrix is shown in Figure 10. The model demonstrated relatively high effectiveness in detecting the maturity of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates, particularly in identifying R class fruits. However, there remains room for improvement in distinguishing between adjacent maturity stages and in separating immature pomegranates from the background.

Figure 10.

Normalized confusion matrix.

3.2. Function Verification

3.2.1. Comparative Experiment of Loss Functions

To validate the superiority of the SlideLoss function in ripeness detection, the Complete IOU (CIOU), Distance IOU (DIoU) [29], Generalized IOU (GIOU) [30], and SlideLoss functions were incorporated into the YOLOv8 model. Comparative experiments were conducted on identical experimental platforms and datasets. As shown in Table 3, the model employing the SlideLoss function achieved the highest P, R, mAP@50 and mAP@50:95 values. This demonstrates that the SlideLoss-based model better adapts to maturity detection of ‘Jiang’ Pomegranate in complex orchard environments, while also effectively mitigating class imbalance.

Table 3.

Model performance with different loss functions.

3.2.2. Comparative Experiments for Different μ Values

As the central threshold for IoU intervals, μ directly influences sample partitioning and weight allocation. To systematically investigate the impact mechanism of the core parameter μ in SlideLoss on model performance, this study conducted comparative experiments by maintaining identical dataset and model operation parameters while varying μ within the range of 0.3 to 0.7. This range covers typical partitioning scenarios for low, medium, and high IoU intervals in object detection tasks. Table 4 presents the detection results under different μ values. Experimental results demonstrate that incorporating the SlideLoss function yields improvements across all metrics compared to the YOLOv8 model, validating the method’s efficacy in addressing sample imbalance. Although variations in the µ parameter between 0.3 and 0.7 did not produce significant performance differences, this further underscores the stability of the SlideLoss approach under different configurations.

Table 4.

The detection results under different μ values.

3.3. Ablation Experiments

By combining the utilized modules in different configurations, this study designed 16 sets of ablation experiments to numerically analyze the performance of each network variant. An impartial evaluation was conducted using images of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates from the test set, and the results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of ablation test of YOLO-AMAS model.

As shown in Table 5, adding the AFE module alone improved R and mAP@50 and mAP@50:95 with negligible influence on model complexity. When the ASFF or MSCAM was integrated individually, both P, mAP@50 and mAP@50:95 increased, though at the expense of higher model complexity. Incorporating SlideLoss alone also boosted precision and mAP without increasing computational complexity. Among two-by-two combinations of modules, the integration of AFE with MSCAM yielded the most substantial improvements in P, mAP@50 and mAP@50:95. Combining ASFF with other modules also improved P, mAP@50 and mAP@50:95 but steadily increased model complexity. When all three modules were combined, additional gains in R, mAP@50 and mAP@50:95 were observed, even though with additional computational overhead. The suggested YOLO-AMAS model achieved the highest ratings in P, R, mAP@50 and mAP@50:95, and among all 16 configurations. In terms of computational cost, its GFLOPs were comparable only to the combination of AFE, MSCAM, and ASFF modules, but lower than the remaining 14 variants, allowing for faster data processing.

3.4. Comparison of Different Detection Models

Table 6 presents the performance metrics of different detection models on the test set. To conduct a quantitative comparison of the performance of the improved model, this study trained all models under identical conditions. These conditions encompassed the same dataset partitioning scheme, data augmentation strategies, hyperparameters, and input resolutions. Specific parameter settings are detailed in Table 1. Subsequently, the proposed model was evaluated against RT-DETR-1 [31], YOLOv3 [32], YOLOv5 [33], YOLOv6 [34], YOLOv8 [35], and YOLO11 [36] on the same test set.

Table 6.

Performance of different detection models in test set.

As shown in Table 6, the proposed improved model in this study achieved the highest P, R and mAP@50 among all compared models, reaching 90.9%, 86.0% and 94.1%, respectively. The ADT discrepancy between YOLO-AMAS and the original YOLOv8 was 0.5 ms. With respect to computational complexity, measured in giga floating-point operations, YOLO-AMAS required higher GFLOPs than YOLOv5, YOLOv8, and YOLO11, but lower than RT-DETR-1, YOLOv3, and YOLOv6. The disparity in GFLOPs between YOLO-AMAS and the original YOLOv8 was 2.3. Due to the high architectural complexity of RT-DETR-1 and the non-lightweight design of YOLOv3′s early architecture, both models showed significantly higher ADT and GFLOPs. In summary, excluding YOLOV3 and RT-DETR-1, while maintaining relatively high precision, the YOLO-AMAS model exhibits slightly longer Average Detection Time compared to the other models, and its GFLOPs is only lower than that of YOLOv6 and slightly higher than those of the remaining models. After a comprehensive consideration of various factors, although the proposed YOLO-AMAS model in this paper incurs an increase in computational cost, given its significant improvement in accuracy, optimization potential for resource constrained devices, and long-term economic benefits, the added complexity is deemed acceptable for the target application [37].

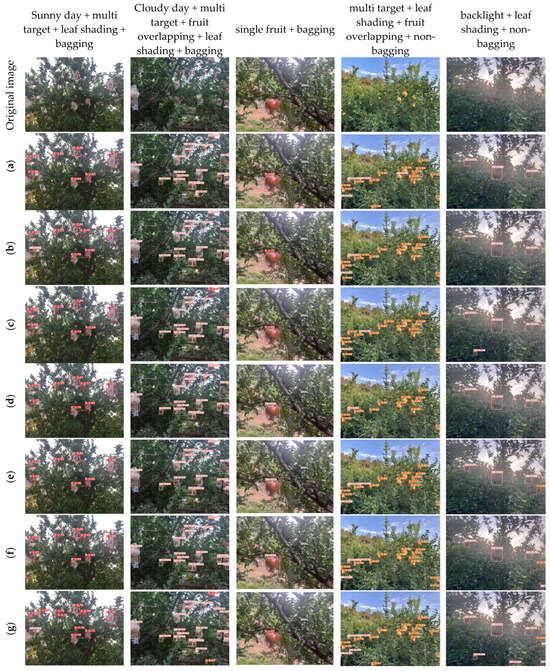

The detection results of each model in complex orchard environments are shown in Figure 11. As seen in Figure 11a, the RT-DETR-1 model performed poorly in detecting multiple mature fruits in both close-up and distant views. While it was feasible to detect bagged immature fruits under overcast conditions, the accuracy was relatively low, and missed detections of distant immature targets were significant. From Figure 11b, the YOLOv3 model exhibited low accuracy in detecting multiple mature fruits at close and distant ranges, with frequent misdetections of semi-mature fruits. Its performance in detecting bagged semi-mature and immature fruits under cloudy conditions was unsatisfactory, and missed detections of distant immature targets were severe. As illustrated in Figure 11c, the YOLOv5 model demonstrated balanced performance: it achieved high accuracy in detecting multiple mature fruits, semi-mature fruits on cloudy days, immature fruits under backlighting, and single fruits under front lighting. However, missed detections of distant immature targets were evident, and a small number of distant semi-mature fruits were misclassified as mature. From Figure 11d, the YOLOv6 model showed overall weaker performance: it performed poorly in detecting multiple mature fruits, had low accuracy for single fruits under front lighting, and only achieved moderate but insufficient accuracy for distant immature and bagged immature targets. As depicted in Figure 11e, the YOLOv8 model exhibited notable advantages: it delivered excellent detection results for multiple mature fruits, semi-mature fruits on cloudy days, distant mature fruits, and immature fruits. It was also capable of detecting occluded targets under backlighting conditions. However, due to the similar colors of distant immature targets and leaves/weeds, only partial detections were achieved with relatively low accuracy. From Figure 11f, the YOLO11 model achieved high accuracy in detecting multiple mature fruits, semi-mature fruits on cloudy days, and single fruits under front lighting. Its performance in detecting immature fruits under backlighting was acceptable, but it performed poorly in detecting distant mature and immature targets. As shown in Figure 11g, the YOLO-AMAS model demonstrated the best overall performance: it achieved high accuracy in detecting multiple mature fruits, immature fruits under backlighting, semi-mature fruits on cloudy days, single fruits under front lighting, and distant mature fruits. Although some missed detections occurred for distant immature targets, its overall performance surpassed that of all other models.

Figure 11.

Comparison of different target detection models. (a) RT-DETR-1. (b) YOLOv3. (c) YOLOv5. (d) YOLOv6. (e) YOLOv8. (f) YOLO11. (g) YOLO-AMAS.

3.5. K-Fold Cross-Validation

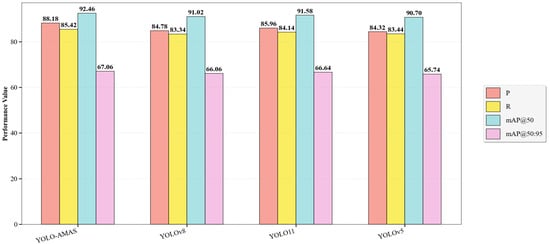

To objectively evaluate the model’s performance on the target dataset, we employed the widely recognized and well K-fold cross-validation strategy in model evaluation [38], setting K = 5. This process involves dividing the entire dataset into five non-overlapping, roughly equal subsets. During each validation iteration, one subset is strictly selected as the validation set, while the remaining four are combined as the training set. The validation set is rotated sequentially, completing five independent training and validation cycles. This approach comprehensively and objectively evaluates the model’s performance and stability under varying data partitioning conditions. Under identical experimental platforms and parameter settings, cross-validation is performed on YOLOv5, YOLOv8, YOLO11, and YOLO-AMAS.

The average results of five-fold cross-validation across different models are shown in Figure 12. The YOLO-AMAS model demonstrates comprehensive superiority across all metrics: P, R, mAP@50, and mAP@50:95. The YOLO11 model performed below the YOLO-AMAS model but above both the YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 models; The YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 models demonstrated very similar performance, with the YOLOv5 model exhibiting the poorest results.

Figure 12.

Average of five-fold cross-validation across different models.

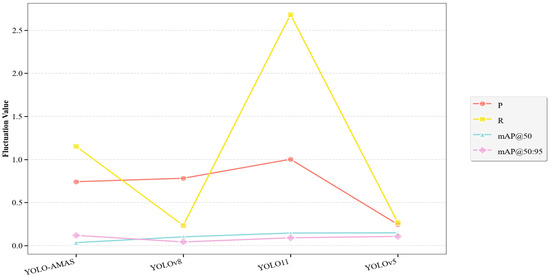

The mean squared error across five-fold cross-validation for different models is shown in Figure 13. Analysis of the validated results reveals that the YOLOv5 model exhibits the least fluctuation, followed by YOLOv8, while YOLO11 demonstrates the greatest variability. The YOLO-AMAS model maintains excellent stability while achieving significantly superior detection accuracy. This confirms the model’s strong generalization capability and stability for performing ‘Jiang’ pomegranate maturity detection tasks in complex environments, indicating that the attained performance metrics are not attributable to random fluctuations or specific data partitioning.

Figure 13.

Mean square error for five-fold cross-validation across different models.

3.6. False Detection Rate

This study selects False Detection Rate (FD Rate) as the key performance metric to evaluate the misclassification of ‘Jiang’ pomegranate maturity categories in complex environments, quantifying the inconsistency in fruit maturity category recognition by the model. The FD Rate formula is defined as Equation (2) [39].

where FP denotes the number of fruits where the IoU between predicted and ground-truth boxes meets the threshold, but the maturity category is incorrectly recognized, TP represents the number of fruits where the IoU between predicted and ground-truth boxes meets the threshold and the maturity category is correctly recognized, and FN indicates the number of missed ‘Jiang’ pomegranate fruits. By setting the IoU threshold, spatial alignment between predicted and ground-truth boxes is ensured, thereby excluding the interference of positional deviations in category evaluation and focusing on the accuracy of maturity classification. The false detection rate was selected for the following key reasons: it directly quantifies the risk of classification errors in practical applications, specifically addressing the challenges of maturity feature ambiguity under complex conditions such as bag reflection and leaf occlusion, thus providing a critical assessment of model reliability [40].

Using the test dataset, with initial manual annotations including 781 R class, 1436 GR class, and 574 G class fruits, totaling 2791 fruits. The false detection rate for each model was computed using the formula above. As shown in Table 4, achieved the lowest overall false detection rate of 2.18%, indicating the fewest misdetections of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates in complex environments and demonstrating optimal technical recognition stability. It also attained the lowest false detection rate for R-class fruits at 1.96%, reflecting higher accuracy in detecting mature fruits. In contrast, RT-DETR-1 exhibited the highest overall false detection rate at 7.77%, indicating pronounced misdetection issues in complex scenarios. The false detection rates of YOLOv3, YOLOv5, YOLOv6, YOLOv8, and YOLO11 ranged from 2.84% to 3.86%, suggesting that these models still exhibit certain false detection problems under challenging conditions. The false detection rate results for each model are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

False detection rate results of different models.

3.7. Heatmap

A detection heatmap visually represents the contribution of different image regions to the prediction outcome, where higher activation values indicate areas in the input image that elicit stronger network responses and contribute more significantly to the detection result [41]. In this study, the Grad-CAM method was employed to generate heatmaps for the improved model, enabling visual interpretation of its decision process [42]. The pixel values in the heatmap reflect the relative importance of each region to the detection outcome.

Figure 14 shows representative heatmaps of ‘Jiang’ pomegranate detection in complex orchard environments. It can be observed that the heatmaps produced by the proposed model closely align with the actual fruit regions. In a variety of challenging scenarios, including close-range multi-fruit scenes, long-range multi-fruit scenes, occlusion by branches and leaves, and fruit overlap, the heatmaps accurately highlight the locations of the fruits. This demonstrates the model’s ability to effectively focus on ‘Jiang’ pomegranate targets under diverse environmental conditions.

Figure 14.

YOLO-AMAS model for detecting heatmap.

The heatmap visualization employs a sequential colormap to spatially represent the model’s detection confidence across the input image. In this representation, red and yellow regions indicate areas of high confidence, where the model strongly activates and reliably detects target objects. Conversely, blue and green regions correspond to low confidence, reflecting minimal model attention or high uncertainty. Intermediate colors such as orange and teal signify moderate confidence levels, which often occur in ambiguous zones.

4. Discussion

This study explored maturity detection of bagged ‘Jiang’ pomegranates in complex orchard environments using the YOLO-AMAS model. The model incorporates an Adaptive Feature Enhancement module, a Multi-Scale Convolutional Attention Module, and an Adaptive Spatial Feature Fusion module, in addition to a SlideLoss dynamic weighting mechanism, achieving a mAP@50 of 94.1%.

In comparison with the YOLO-MSNet proposed by Xu et al., which increased mAP@50 by 1.7% while reducing parameters and model size by 21.5% and 21.8%, respectively [8], the proposed model exhibits competitive performance. Likewise, Wang et al. improved PG-YOLO to attain 93.4% mAP@50 with a model size of only 2.2 MB [9]; Du et al. developed TP-YOLO with an accuracy of 94.4% [10]; Zhao et al. significantly compressed their model [11]; and Rupa et al. reported a 2.6% mAP improvement with YOLOv8 [12]. While these studies have attained remarkable results, most focused on maturity detection of non-bagged pomegranates or those in simple environments. This study bridges the research gap in maturity detection of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates in complex orchard conditions, attaining a mAP@50 of 96.4% for bagged mature fruits and through five-fold cross-validation, the model’s strong generalization capability and stability were demonstrated. In contrast to YOLOv8, YOLO-AMAS decreases the false detection rate by 30.3%, providing reliable technical support for automated harvesting of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates in complex orchard environments.

Although there are advancements in model performance, this study has certain limitations. Owing to unforeseeable factors in complex orchard environments, further analysis is needed to improve detection capability and understand factors affecting recognition. Three representative detection cases are demonstrated in Figure 15 to discuss these challenges. Possible reasons for misdetection encompass: the color similarity between paper bags and semi-mature pomegranates, leading to misidentification of bags as semi-mature fruits, as shown in the blue circle in the upper left of Figure 15a; faint lighting during dusk causing leaves and immature pomegranates to exhibit similar colors, possibly resulting in leaves being misclassified as immature fruits, as indicated by the blue circle in the lower part of Figure 15b; and the use of white polyethylene film as the primary bagging material, where shading and reflection phenomena decrease recognition accuracy, leading to mature fruits being misidentified as semi-mature, as demonstrated by the blue circle in Figure 15c.The letters G, GR, and R in the figure represent immature, semi-mature, and mature, respectively. The accompanying numbers are confidence scores, typically ranging from 0 to 1. A higher value indicates that the model is more certain about the correctness of the detection.

Figure 15.

Identification Case. (a) Identify Paper Bags. (b) Identify Leaves. (c) Identify Category.

To improve detection accuracy in complex orchard environments, the following measures could be implemented: increasing the number of samples that are difficult but crucial for recognition, such as images of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates with significant reflections under low-light conditions, to diversify the dataset and enhance model detection capability; further refining the model’s feature extraction ability, particularly for detecting small targets.

Furthermore, the introduction of the SlideLoss loss function enhances results by effectively mitigating class imbalance issues. However, its sensitivity to µ values remains limited, the observed phenomenon may be attributed to the distribution pattern of the predominant class in the dataset, which appears to alleviate the effects of imbalance between easy and hard samples. The original weighting function of SlideLoss exhibits relatively gentle gradient changes within the practical parameter range, making it difficult to induce significant performance differences in current detection tasks. Future work will explore weighting function designs with enhanced sensitivity and dynamic µ adjustment strategies to improve the effectiveness of parameter tuning. Concurrently, integrating category-aware mechanisms with other imbalance mitigation techniques will be considered to further optimize model performance.

5. Conclusions

This study tackles the challenge of maturity detection in ‘Jiang’ pomegranates within complex orchard environments. To address these issues, an improved YOLO-AMAS model was proposed, incorporating several key enhancements: an Adaptive Feature Enhancement module was incorporated to suppress background noise through dual-channel space attention; a Multi-Scale Convolutional Attention was fused to capture multi-scale features using pyramidal dilated convolutions; and an Adaptive Spatial Feature Fusion module was utilized to dynamically align shallow texture features and deep semantic representations via learnable weights. Additionally, a SlideLoss mechanism based on Intersection over Union was implemented to mitigate class imbalance, thereby improving the detection accuracy of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates. The overall average P, R, mAP@50 and mAP@50:95 attained 90.9%, 86.0%, 94.1% and 67.6%.

Compared with various foundational models, the proposed model demonstrated outstanding detection performance across various challenging scenarios such as multi-object detection, fruit overlap, leaf occlusion, varying lighting conditions, and bagging interference, achieving the highest P, R, and mAP@50. These results fully demonstrate the effectiveness and efficiency of YOLO-AMAS in complex orchard environments, providing a reliable and efficient solution for intelligent ripeness detection of ‘Jiang’ pomegranates.

Despite the model’s outstanding performance, its recognition accuracy remains subject to some degree of variation in specific scenarios. Furthermore, detection speed on resource-constrained hardware requires further enhancement. Consequently, subsequent research should focus on constructing datasets under extreme weather conditions, optimizing the model architecture to improve adaptability to adverse environments such as low light and high humidity, and pursuing lightweight design to reduce deployment burdens on embedded devices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.H. and H.L.; methodology, C.H.; software, H.L.; validation, J.Z., W.D. and H.L.; formal analysis, J.Z.; investigation, C.H.; resources, X.Z.; data curation, C.H. and H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.H.; writing—review and editing, X.Z.; visualization, C.H.; supervision, W.D.; project administration, H.L.; funding acquisition, X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Science and Technology Innovation Enhancement Project under the Scientific Research Initiatives of Shanxi Agricultural University (No.CXGC2025057).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to concerns that disclosure may adversely affect future research projects.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tan, D.D.; Hao, L.; Ma, C.; Liu, Y.G. Main Pomegranate Cultivars and Breeding Directions in China. China Fruits Veg. 2025, 45, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Tang, G.M.; Shu, X.G.; Yang, L.; Luo, H.; Bi, R.X.; Zhao, D.C. Current Status of Breeding and Protection for New Pomegranate Cultivars in China. China Fruits Veg. 2025, 45, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Farmers’ Daily. Linjin Town, Linyi County, adjusts crop structure to vigorously develop the production of Jiang pomegranate. Fruit Grow. Friend 2006, 10, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture of China. Six projects in Shanxi Province shortlisted for China’s National Inventory of Important Agricultural Heritage Systems. Herit. Conserv. Stud. 2017, 1, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Q.; Du, J.J.; Wang, S.L. Pollution-Free Cultivation Techniques for Jiang Pomegranate. In Proceedings of the National Fruit Tree Academic Symposium & Annual Conference of the Fruit Tree Professional Committee, Beijing, China, 1 September 2006; China Agricultural Technology Extension Association: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Z.S. Analysis of Climatic Conditions for Pomegranate Cultivation in Linyi County and Meteorological Service Measures. South. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 81–83. [Google Scholar]

- Cubero, S.; Lee, W.S.; Aleixos, N.; Albert, F.; Blasco, J. Automated Systems Based on Machine Vision for Inspecting Citrus Fruits from the Field to Postharvest—A Review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2016, 9, 1623–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, B.; Fu, X.; Lu, Z.; Li, Z.; Jiang, B.; Jia, S. YOLO-MSNet: Real-Time Detection Algorithm for Pomegranate Fruit Improved by YOLOv11n. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Du, Y.; Zhao, M.; Jia, H.; Guo, Z.; Liu, Y. PG-YOLO: An Efficient Detection Algorithm for Pomegranate Before Fruit Thinning. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 134, 108700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Han, Y.; Su, Y.; Wang, J. A Lightweight Model Based on You Only Look Once for Pomegranate Before Fruit Thinning in Complex Environment. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 137, 109123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Du, C.; Li, Y.; Mudhsh, M.; Guo, D.; Fan, Y.; Almodfer, R. YOLO-Granada: A Lightweight Attentioned YOLO for Pomegranates Fruit Detection. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupa, N.B.; Balasuriya, R.; Siddharth, D.; Hima, Y.; Sowmya, V. Transformative Technologies in Agriculture: Growth Stage Detection in Pomegranate Using YOLO. In Proceedings of the Congress on Intelligent Systems 2024, Bangalore, India, 4–5 September 2024; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Melgarejo-Sánchez, P.; Núñez-Gómez, D.; Martínez-Nicolás, J.J.; Hernández, F.; Legua, P.; Melgarejo, P. Pomegranate Variety and Pomegranate Plant Part, Relevance from Bioactive Point of View: A Review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.W.; Dou, H.; Xiao, G.G. Few-Shot Object Detection via Integrated Classification Refinement and Sample Augmentation. J. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2024, 60, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawole, O.A.; Opara, U.L. Developmental Changes in Maturity Indices of Pomegranate Fruit: A Descriptive Review. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 159, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, R.; Sambath, M. YOLOv8: A Novel Object Detection Algorithm with Enhanced Performance and Robustness. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advances in Data Engineering and Intelligent Computing Systems (ADICS), Chennai, India, 18–20 April 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Lv, J.; Zhang, C. MAE-YOLOv8-Based Small Object Detection of Green Crisp Plum in Real Complex Orchard Environments. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 226, 109458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Jiang, C.; Song, L.; Liu, F.; Tao, Y. RVDR-YOLOv8: A Weed Target Detection Model Based on Improved YOLOv8. Electronics 2024, 13, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Abeyrathna, R.R.D.; Sampurno, R.M.; Nakaguchi, V.M.; Ahamed, T. Faster-YOLO-AP: A Lightweight Apple Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLOv8 with a New Efficient PDWConv in Orchard. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 223, 109118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.U.; Qin, Y.C.; Jia, Z.; Wang, G. Small Object Detection Algorithm Based on ATO-YOLO. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2024, 60, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Y. Precise Recognition of Gong-Che Score Characters Based on Deep Learning: Joint Optimization of YOLOv8m and SimAM/MSCAM. Electronics. 2025, 14, 2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.W.; Zhou, J. Grape Maturity Detection in Complex Environments Using Improved YOLOv7. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2025, 41, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Huang, H.; Chen, W.; Su, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X. YOLO-FaceV2: A Scale and Occlusion Aware Face Detector. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 155, 110714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; White, T.S.; Zhang, H.; Hu, W.; Wunsch II, D.C.; Liu, J. MS-YOLO: Infrared Object Detection for Edge Deployment via MobileNetV4 and SlideLoss. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.21696. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, E.; Zou, Y.; Chen, J.; Peng, J.; Huang, C.; Li, F.; Zhang, M. Enhancing LDD Diagnosis with YOLOv9-AID: Simultaneous Detection of Pfirrmann Grading, Disc Herniation, HIZ, and Schmorl’s Nodules. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1626299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.Y.; Li, H.T.; Chen, X.Y.; Yao, W. Research on YOLOv8-Based Mango Object Detection Algorithm Integrating Progressive Spatial Pyramid Pooling. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 2025, 62, 1415002. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, X.; Qi, K.; Yang, F.; Na, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, C. RSR-YOLO: A Real-Time Method for Small Target Tomato Detection Based on Improved YOLOv8 Network. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Misra, U. Deep Learning for Weed Detection: Exploring YOLO V8 Algorithm’s Performance in Agricultural Environments. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Disruptive Technologies (ICDT), Greater Noida, India, 15–16 March 2024; pp. 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ye, R.; Ren, D. Distance-IoU Loss: Faster and Better Learning for Bounding Box Regression. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; pp. 12993–13000. [Google Scholar]

- Rezatofighi, H.; Tsoi, N.; Gwak, J.; Sadeghian, A.; Reid, I.; Savarese, S. Generalized Intersection over Union: A Metric and a Loss for Bounding Box Regression. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 658–666. [Google Scholar]

- Nahiduzzaman, M.; Sarmun, R.; Khandakar, A.; Faisal, M.A.A.; Islam, M.S.; Alam, M.K.; Chowdhury, M.E. Deep Learning-Based Real-Time Detection and Classification of Tomato Ripeness Stages Using YOLOv8 on Raspberry Pi. Eng. Res. Express. 2025, 7, 015219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B.S.H.; Venkatramana, R.; Jayasree, L. Enhancing Apple Fruit Quality Detection with Augmented YOLOv3 Deep Learning Algorithm. Int. J. Human Comput. Intell. 2025, 4, 386–396. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H.; Li, Z.; Zou, X.; Wang, H.; Song, J. Research on Litchi Image Detection in Orchard Using UAV Based on Improved YOLOv5. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 263, 125828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.C.; Lee, S.; Jeong, J.; Kim, S. YOLOv6+: Simple and Optimized Object Detection Model for INT8 Quantized Inference on Mobile Devices. Signal Image Video Process 2025, 19, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Miao, Z.; Huang, W.; Han, W.; Guo, Z.; Li, T. SGW-YOLOv8n: An Improved YOLOv8n-Based Model for Apple Detection and Segmentation in Complex Orchard Environments. Agriculture 2024, 4, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Dong, W.; Hou, P.; Li, H.; Han, X.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, X. YOLOv11-BSD: Blueberry Maturity Detection Under Simulated Nighttime Conditions Evaluated with Causal Analysis. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, R.; Sun, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, N.; Lu, X.; Gong, J.; Cui, T. Intelligent Detection of Lightweight “Yuluxiang” Pear in Non-Structural Environment Based on YOLO-GEW. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sportelli, M.; Apolo-Apolo, O.E.; Fontanelli, M.; Frasconi, C.; Raffaelli, M.; Peruzzi, A.; Perez-Ruiz, M. Evaluation of YOLO Object Detectors for Weed Detection in Different Turfgrass Scenarios. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, H. Reducing False Positives in Video Object Detection via Temporal Consistency. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 12345–12355. [Google Scholar]

- Ukwuoma, C.C.; Zhiguang, Q.; Heyat, M.B.B.; Ali, L.; Almaspoor, Z.; Monday, H.N. Recent Advancements in Fruit Detection and Classification Using Deep Learning Techniques. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 1, 9210947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, H.; Liao, K.; Li, L. YOLO-CFruit: A Robust Object Detection Method for Camellia oleifera Fruit in Complex Environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1389961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Sun, Y.; Li, C.; Liu, Z.; Song, H. AHG-YOLO: Multi-Category Detection for Occluded Pear Fruits in Complex Orchard Scenes. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1580325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).