Abstract

Soil aggregate stability is a key indicator of soil health and is fundamental to soil processes such as water infiltration, nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration, erosion control, and ecosystem functionality. However, research concerning the impact of natural and anthropogenic factors on SAS across different climates, soil types, and management practices is lacking. This review synthesizes current understanding of physical, chemical, and biological mechanisms that govern the aggregate formation and stability and brings to light how the natural and anthropogenic drivers influence these processes. It highlights how clay mineralogy, root systems, microbial diversity, soil organic matter, and management practices shape the structure and turnover of aggregates essential for agricultural productivity. Key drivers of aggregate formation, categorized into natural (such as texture, clay mineral interaction, biota, and climate) and anthropogenic (such as tillage, land use changes, organic amendments) factors, have been critically evaluated. This review provides an insightful framework for soil management that may help enhance soil aggregation and promote sustainable agriculture and food security, especially under climate change.

1. Introduction

Soil aggregates are the dynamic structural units that form or break down through the interaction among biotic and abiotic factors. Their states reflect the balance between the formation processes that bind the particles together and the disintegration process that weakens the bonds of aggregation. The arrangement of soil aggregates influences soil structural properties such as pore size distribution, which in turn affects water infiltration and retention, microbial activity, nutrient cycling, and carbon retention in soils [1]. The longevity of soil aggregates is known as soil aggregate stability (SAS), which is a measure of the ability of soil aggregates to resist breakdown [2]. It is usually expressed as the percentage of aggregates that remain after being exposed to destabilizing stress such as wetting, shaking, or mechanical agitation. According to Angers et al. [3], high aggregate stability may enhance soil fertility, boost agronomic production, and lessen erodibility. SAS serves as an indicator for changes in soil quality in terrestrial ecosystems; it directly affects soil structure, soil porosity, fertility, and ecosystem functioning. Moreover, information on SAS is also helpful in the restoration of degraded lands [4]. A related concept, soil structural stability (SSS), is the ability of the soil structure to withstand external stressors like water and mechanical stress [5]. Since the soil aggregation is fundamental to nearly all soil functions, like water infiltration and retention, nutrient cycling, microbial activity, and organic matter (OM) decomposition, enhancing aggregate stability may lessen soil degradation and improve soil physical conditions for plant development [6]. Soil aggregates protect OM from rapid mineralization by physical occlusion of particulate organic matter (POM) within micro-aggregates, binding it in organo-mineral associations and constraining OM diffusion [7,8].

Soil aggregation results from the balance between the process of formation, stabilization and disintegration of soil aggregates. Aggregation is promoted by physiochemical mechanisms, such as organo-mineral association, cation bridging and OM and metal oxide interactions. Soil aggregate formation is also considerably affected by physical entanglement of particle by plant roots and fungal hyphae, particularly arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), plant root exudates (rhizodeposits) and secretion of proteins like glomalin by AM fungi which act as cementing material for soil aggregation [9]. Organic matter inputs especially particulate organic matter (POM) and microbial exudates such as extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), act as a key binding agents for aggregate formation [10,11]. However, many natural and anthropogenic factors which include soil erosion, inappropriate use of fertilizers, chemicals, and pollution by industrial effluents, loss of organic matter and soil biodiversity as well as climate change, threaten soil health and negatively affect aggregate stability and soil functional capacity [12]. Also, soil aggregates have recently drawn attention as potential sinks for carbon. To understand the mechanism of soil organic carbon (SOC) sequestration, understanding the role soil aggregates play in protecting SOC from decomposition is essential. Examining the SOC distribution and mineralization in different-sized aggregates might help us understand how soil aggregates cause sequestration [13]. In the current review, we delve into various factors including physical, chemical and biological, that affect soil aggregation, and have been hitherto studied only at individual levels without any reasonable attempt of integration of these factors into a wholistic picture [11,12]. Moreover, the role soil of aggregates in regulating soil health and associated ecosystem services has only been sparsely investigated [13,14]. To close this gap, a critical and updated review connecting soil aggregate dynamics with soil health indicators, ecosystem resilience, and sustainable land management is crucial. Thus, the objective of this study is to review recent information on soil aggregate dynamics, mainly focusing on the processes involved in aggregate formation, stabilization, and deterioration, as well as natural and anthropogenic forces driving soil aggregate formation. Finally, we intend to identify knowledge gaps and propose possible future research paths to fortify sustainable soil management based on available knowledge and understanding of aggregate behaviors.

2. Data Analysis

A comprehensive literature review was undertaken using electronic databases of information, including Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science (WoS). The literature search was conducted using the keywords “soil aggregates,” “aggregate stability,” “aggregate mechanism,” “soil organic matter,” “soil structure,” and “soil management practices.”. These keywords were selected to address the formation and stability of aggregates as well as their relationship to soil structure function. The search yielded 820 peer-reviewed articles published from 2000–2025. To narrow down the data, the articles were filtered by the following criteria: (a) Studies investigating soil aggregation, SOC, or soil health exclusively; (b) studies documenting experimental or methodological procedures; (c) studies on analysis of soil physicochemical or biological characteristics; and (d) studies on analysis of natural (i.e., soil texture, clay mineralogy, SOM quality, microbial activity, root traits, climate drivers) or anthropogenic (i.e., tillage, land-use change, organic amendments, cover crops, fertilization, pollution, restoration) mechanisms of aggregate formation. Studies were excluded if they lacked methodological clarity or only peripherally examined soil structure or characteristics of soil structure or lacked applicable functional guidance or recommendations for management. Upon screening, 223 studies met the above criteria and were analyzed for synthesis.

3. Soil Structural Stability: Theoretical Foundations

Soil structure, the manner in which soil aggregates assemble and enclose spore spaces between them, is vital for soil health and productivity. Soils with stable aggregates and well-connected pore spaces enable better gas and water transport, facilitate root penetration and development, and microbial function, while also enhancing erosion resistance by reducing surface sealing and runoff [14]. The formation and stabilization of soil aggregates (building blocks of soil structure) are affected by biochemical processes as well as soil organisms. For example, large soil organisms (macro-fauna) break down organic matter (OM), and microorganisms convert it into binding agents that hold mineral soil particles together [15].

Physico-chemical interactions between binding agents like Fe, Al, and Mn and soil organic matter (SOM) are central to micro-aggregate (<250 µm) formation, while SOM is the major binding agent for macro-aggregate (>250 µm) formation [16,17]. Also, micro-aggregates form within macro-aggregates [18]. The macro-aggregates eventually combine to form larger clusters, known as peds. Aggregates with internal porosity are classified as true aggregates, while as compact aggregates lacking internal pore spaces are described as false aggregates. In addition, aggregates may be described as water-stable or water-unstable depending on their resistance to slaking. Numerous agronomic and environmental processes, including the dynamics of SOC and the variety and activity of soil organisms, are affected by soil structure [19].

Soil hydrophobicity, the ability of soil particles to repel water due to the presence of hydrophobic organic compounds, has a dual role in the formation and stability of soil aggregates. At moderate levels, hydrophobic substances formed from plant residues, microbial metabolites, or the addition of biochar can stabilize aggregates because these neutral organic coatings reduce the water infiltration rate and allow better stabilization of aggregates during wetting and also reduce slaking and disintegration of aggregates [20,21]. The coatings can also slow microbial decomposition of OM that might be present in the aggregates, thereby increasing its residence time in the soil matrix [2]. On the other hand, increased hydrophobicity due to the release of hydrophobic materials after fire incidents or hydrophobic amendments can reduce soil wetting contact, decrease water retention, and restrict microbial activity [22]. Additionally, increased hydrophobicity is associated with greater aggregation, decreased wetting contact, crusting and decreased infiltration, especially in sandy or degraded soils with greater risks of erosion [23,24]. Hydrophobic OM additions, despite their positive effects on aggregate formation and stability, can cause water repellency and reduce infiltration which can affect hydraulic property of soils [22,25].

4. Function of Soil Aggregate Stability

Beyond their physical role in soil structure, aggregates act as functional hubs that regulate soil ecosystem services by protecting soil organic carbon, influencing long-term carbon sequestration and climate regulation. Their role in maintaining pore continuity supports water infiltration, storage, and purification services. At the biological level, aggregates provide habitats for microbes and fauna, thereby sustaining nutrient cycling and biodiversity. The cumulative effect of these processes underpins soil health, making aggregate stability a central determinant of ecosystem functionality. In all, soil aggregate stability affects the following functions of soils.

4.1. Nutrient Cycling

Soil aggregates and the cycling of nutrients are interwoven, as different microhabitats created by aggregates influence the microbial community structure and function, which ultimately play a role in the cycling of essential nutrients [26]. For example, macro-aggregates, or larger soil aggregates, are porous and are closely associated with microbial groups that are adapted to the oxygen-rich and dynamic habitats. Many copiotroph microbes of nutrient-rich environments are found in such aggregates, which aid in cycling nutrients, for example, by supporting the oxidation of acetyl-CoA and ammonia, both of which are important in C and nitrogen (N) cycles [27]. Also, larger aggregates enable greater urease activity through their provision of labile C. In contrast, micro-aggregates are more stable and favor microbes sensitive to drying and gas exchanges. Various bacteria involved in N cycling are found in different-sized aggregates [28]. By altering the spatial heterogeneity found in the aggregates, the activity and distribution of ureolytic microbes, important in urease activity and N cycling, can also be regulated. However, how soil aggregates may affect nutrient cycling may be complex, because nutrient cycling is influenced by many factors, including aggregate size, composition of the microbial community, and external inputs such as organic matter and fertilizers, etc. [29].

4.2. Water Infiltration

The internal structure of aggregates plays a vital role in determining water infiltration rates due to its influence on the physical properties of the soil, particularly concerning the ability to retain and transmit water [30]. Within a given soil system, an external force can compact soil aggregates and cause a significant change in pore size distribution, reducing the volume of large interpore and increasing the proportion of smaller intrapore volume, thereby lowering the water penetration potential [31]. The stability and continuity of the pore systems are essential for air and water transport and strongly affect permeability and air-filled pore space in soils [32]. Larger macro-aggregates can contribute to macropores, enhance the hydraulic properties of the soil by increasing the saturated hydraulic conductivity, allowing for greater water movement down through the soil profile [33]. Saturated hydraulic conductivity depends on the continuity of macropore networks, and even small proportions of micro-aggregates can clog interaggregate pores and restrict water flow [34,35]. The intra-aggregate pore structure varies depending on soil type and environmental conditions, with attendant effects on water flow and retention. Continuous pore networks lead to greater infiltration [36]. Differential permeability for water and air is also largely determined by soil aggregates, as these regulate pore architecture and connectivity. The stability and continuity of the pore systems are essential for air and water transport and strongly affect permeability and air-filled pore space in soils [32]. The arrangement and deformation of aggregates modify the permeability; in isotropic deformation, the permeability is preserved against the applied stress of compaction [37]. Overall structural maintenance and arrangement of soil aggregates are crucial for maintaining permeability in adequate proportions, which is essential for the better health and function of soil in diverse environmental and agricultural settings.

4.3. Carbon Sequestration

Soil aggregates serve as bioindicators of C sequestration concerning the storage and stability of soil organic carbon (SOC) in different ecosystems and land-use types. While the micro-aggregates are most proficient in long-term SOC storage, macro-aggregates store labile organic matter, which contributes to short-term storage, and meso-aggregates also play an essential role in SOC storage by protecting C from microbial decomposition [18,38]. The stability and C sequestration potential of these aggregates vary with changing environmental conditions and management practices. In forest ecosystems, plant species composition and diversity exert influence on aggregate stability and the spatial distribution of SOC, with mixed-species forest types sustaining the stability of macro-aggregates and greater SOC stocks [39]. Conversely, within urban green infrastructures, the micro-aggregates formed within decomposed macro-aggregates stably hold SOC [40]. Topographic factors, such as slope position in karst regions, highlight the role of macro-aggregates in carbon sequestration, whereby higher carbon storage occurs on thermodynamically more stable anti-dip slopes [41]. Organic amendments, e.g., biochar application, favors the formation and stabilization of macro-aggregates and consequently SOC sequestration [42]. In the same way, continuous straw return in arid farmland promotes micro- to macro-aggregate transformation, hence enhancing soil structure and stabilization of SOM [43]. Furthermore, human interventions in the saline-sodic soil, including organic amendments such as compost, vermicompost, farmyard manure, and biochar, increase macro-aggregate proportions and correlated fractions, contributing to C stock buildup [44]. Variations in land use and soil management practices and environmental conditions considerably affect the C sequestration potential of soil aggregates; consequently, strategies to enhance soil C storage may be context specific [45].

4.4. Erosion Prevention

Soil aggregate stability strongly affects detachment, transport, and crusting of soil particles, thereby immensely affecting susceptibility or resistance to erosion [46,47]. Soil aggregates prevent erosion primarily by imparting stability and resistance to various kinds of forces; stable aggregates are less prone to disintegration and subsequent transport of sediment [30]. The proportion of water-stable aggregates (WSA) and mean weight diameter (MWD) are commonly used to assess erosion resistance [15]. The other tools better indicate erosion susceptibility of aggregates in terms of their degrees of dispersion, disintegration, and destruction and include mean weight soil specific area (MWSSA) and percentage of aggregate destruction (PAD) [47,48]. In a study by Gan et al. [47] soil was fractionated into macro-aggregates (>0.25 mm), micro-aggregates (0.053–0.25 mm), and silt + clay (<0.053 mm), and the authors found that macro- and coarse macro- (>2 mm)aggregates were associated with erosion resistance, while smaller micro-aggregates (<0.25 mm) were more erosion susceptible. Moreover, the high proportion of water-resistant clumps (>10 mm) is effective in resisting water erosion, while the presence of finer particles makes soil prone to wind erosion [49]. Soil aggregates prevent erosion by adding macro pore space to the soil system, thereby improving water infiltration and decreasing surface runoff, which in turn minimizes erosion risk [50]. Aggregate stability has a spatial pattern driven by environmental factors, including slope, elevation, and land use, which bolster resistance against water erosion [51]. The levels of moisture, OC, and clay content in the aggregates strongly affect resistance to slaking and physio-chemical dispersion. Secondary aggregates decrease wind erosion by increasing surface roughness and consequently decreasing wind friction velocities, though this function is only effective till the clods are stable. The soil aggregate microbiome may also improve soil structure and function, thereby enhancing erosion resistance and SOC storage [52]. Aggregate stability has a spatial pattern driven by environmental factors, including slope, elevation, and land use, which bolster resistance against water erosion [51]. The soil aggregate microbiome may also improve soil structure and function, thereby enhancing erosion resistance and SOC storage under conservation farming practices [52]. Soil aggregates are a primary means of preventing erosion by keeping soil structure, enhancing water infiltration, and resisting both water- and wind-driven erosion, thus supporting ecological restoration and sustainable land management [50]. The function and role of soil aggregate cited from different studies is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of studies indicating the key function of soil aggregates.

5. Soil Aggregation and Its Impact on Soil Health

Soil is a living system; its health represents the ability to sustain biological productivity, maintain environmental quality, and support plant and animal health [68]. Soil functions are integral to maintaining soil health. Biological soil health is reflected by microbial diversity, enzymatic activity, and symbiotic relationships, which influence nutrient cycling and OM decomposition [2,69]. Healthy soils contribute not only to food security but also to climate regulation and biodiversity conservation and also promote environmental resilience [2]. Soil aggregation has a central role in regulating these ecological functions [10].

Soil management strategies, including conservation tillage, cover cropping, organic amendments, and the use of biofertilizers promote aggregation and therefore can be useful in restoring degraded soils. Conservation agricultural practices enhance microbial diversity and activity as compared to intensive agriculture [70]. Integrating these practices with emerging technologies such as microbial inoculants and precision agriculture can enhance aggregate formation and function across different soil types and climates [71,72,73].

6. Formation of Soil Aggregates

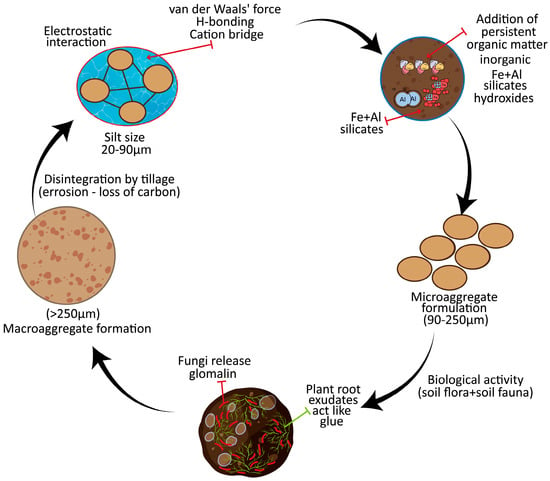

The formation and disintegration of soil aggregates involve a wide range of biotic and abiotic processes. Biotic mechanisms include root growth, fungal hyphae, microbial exudates, and SOM. Abiotic mechanisms include cation bridging, organo-mineral complexation, and physical drivers such as wetting-drying, swelling-shrinking, and freezing-thaw cycles [16]. The SOM contributes to the formation and stabilization of both macro- and micro-aggregates according to the aggregate hierarchy model [74]. Particulate organic matter (POM) and complex organo-mineral web, promote the formation of micro-aggregates (<250 nm) and their long-term stability [16]. Micro-aggregates are composed of silt-sized particles (20–90 µm) bonded together by persistent organic bonding agents. These bonding agents typically consist of an organic nucleus linked with inorganic compounds. The temporary and transitory bonding agents like fungal hyphae, EPS, and other sticky substances facilitate the association of micro-aggregates into macro-aggregates (>250 µm) (Figure 1) [75].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the soil aggregate life cycle, showing how micro-aggregates form around organic matter cores, combine into macro-aggregates through fungal hyphae and root enmeshment, and eventually undergo turnover and disintegration. This process highlights the dynamic balance between aggregate formation and breakdown that regulates soil structure and carbon stabilization.

According to this scheme, micro-aggregates form a nucleus at the heart of the macro-aggregates, which are bound together by transitory bonding agents, primarily roots and fungal hyphae. Within a brief period, the micro-aggregates break down, releasing minute clay-encrusted, mucilage-covered particles that form new micro-aggregates inside macro-aggregates [76,77].

In the aggregation model proposed by Bronick and Lal [78] micro-aggregates develop by the gradual accumulation of clay particles, cations, and POM, or even the disintegration of macro-aggregates and the macro-aggregates develop from the accumulation of micro-aggregates around POM or bacterial cores. Cationic bridges between clay and SOM facilitate particle agglomeration. Some cations (Si4+, Fe3+, Al3+, and Ca2+) cause precipitation of specific compounds, such as hydroxides, phosphates, and carbonates, which facilitates the aggregation of primary particles. In all, several factors influence soil aggregation, which can be conveniently divided into natural and anthropogenic drivers of soil aggregate formation.

6.1. Natural Drivers

6.1.1. Mineralogical Composition

Clay minerals affect the physical and chemical activities in the soil, which directly influence the formation and stability of the aggregates. They also influence how soil responds to OM and other mineral additions. Due to their large specific surface area and surface charges, clay minerals stimulate interactions with SOM, leading to the formation of organo-mineral complexes, which are vital both for the development and stability of aggregates [79]. The process of aggregation is induced through forces—the van der Waals and Coulomb forces. Intense attraction among the particles causes the constructive distance to decrease among them due to compression [80]. Moreover, the stability of clay aggregates depends on the specific cation effects, e.g., Cs, K, Na, and Li, imparting variable stability to montmorillonite aggregates in the order of Cs+ > K+ > Na+ > Li+ [81]. This is due to high polarization (non-classical polarization) of adsorbed cations under strong electric fields reducing repulsion more than expected as per the classical DLVO (Derjaguin–Landau–Verwey–Overbeek) theory. Kaolinite and many iron and aluminum oxides—goethite, hematite, and gibbsite—are common components of highly weathered soils; goethite and gibbsite have been reported to favor micro-aggregate formation in tropical soils [82,83]. Soil aggregate formation and stabilization is not only affected by the presence but also the relative proportion of different soil minerals [84,85]. Kaolinite is one of the most efficient clay minerals in promoting aggregate stability because it strongly interacts with OM, whereas quartz interacts rather poorly, making soils less stable [86]. Kaolinite favors block structure due to face-to-face alignment, while gibbsite enhances microgranular structure [83,87]. The polyvalent cations, such as calcium and aluminum, promote aggregation and, therefore, stabilize the aggregates, whereas monovalent cations, such as sodium, result in dispersion and instability [88]. The clay types in the soil also determine the fertility of the soil by regulating and controlling nutrient supply and the sequestering of OM, which is supposed to stabilize aggregates [89]. For example, the presence or absence of certain clay minerals like hydroxy-interlayered vermiculite or illite might affect organic carbon distribution across aggregates and thus the internal stability and carbon sequestration capacity of the soil [90]. In addition, clay minerals are important elements of the hierarchy model of aggregates, according to which smaller aggregates are formed by reactivity or mineral cohesion, whereas larger aggregates are developed by physical enmeshment through roots and fungal hyphae [91]. Thus, clay minerals play a strong role in the formation and stability of soil aggregates [92,93,94].

6.1.2. Soil Texture

Soil texture (relative proportion of sand, silt, and clay) is a fundamental property that influences particle aggregation, soil structure, nutrient cycling, and the association of organic carbon and nutrients with aggregates. Clay particles, with their high specific surface area and chemical reactivity, can act as nuclei to form micro- and macro-aggregates, leading to a favorable soil structure [78]. The SOM can be preserved from microbial decomposition by binding to clay particles, either through chemical stabilization or physical protection [95].

As clay content increases, the type of clay becomes more important than the amount in determining aggregation [96]. In many cases, silt particles are also involved in micro-aggregate formation and serve as intermediate binding agents surrounding the core of organic matter. On the other hand, sandy fractions, which are characterized by low surface reactivity and little capacity to interact by charge, contribute little to aggregation [8,75]. In the case of coarse-textured soils, aggregates themselves are typically less stable and more susceptible to slaking and erosion and rely on biotic factors, i.e., roots, hyphae, and exudates, etc., to hold the aggregate together [76,77]. In general, sandy soils are still physically fragile unless they are altered by organic amendments and vegetation inputs, whereas fine-textured soils with higher clay and silty fractions usually have deeper aggregate stability and physical stability [78,79]. Soil texture significantly influences the distribution of organic carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus within soil aggregates and considerably affects soil aggregate formation [97]. In particular, SOM can be preserved from microbial decomposition by binding to clay particles, either through chemical stabilization or physical protection [95]. Thus, soil texture, particularly clay content, is a key factor incorporated into various soil models (such as DNDC, Hydrus, Century, and Biome-BGC) that simulate physical, chemical, and biological processes in soils and other ecosystems. Coarse-textured soils tend to have higher nutrient availability compared to fine-textured soils [98]. Earlier studies on soil structure have focused on clay-sized particles as the main binding agent and underestimated the role of other soil particles [99]. More recent studies have shown that sand grains could actively contribute to aggregation through capillary (water menisci) forces, helping larger primary particles to consolidate in aggregates [100]. Similarly, a significant amount of silt-sized particles were released when larger aggregate structures (>50 μm) are broken down into smaller sizes (<50 μm) using glass beads, indicating their role in aggregation [101]. Different size fractions in the range of micro-aggregates contain different ratios of silt- and clay-sized building particles. The distribution of specific surface area, which is largest in fine particle fractions, is shaped by the organization of particle sizes into aggregate structures [102].

It is also important to note that methodological variations in assessing soil texture, in particular, sand and silt separation, can produce uncertainties that limit the interpretation of texture aggregation relationships. Specifically, classical sedimentation methods (pipette, hydrometer) and more modern laser diffraction methods often yield very different estimates of silt and fine sand due to the nature of the particle dispersion, the optical assumptions and formulas used, as well as pre-treatment (e.g., removal of organic matter, use of chemical dispersants) [103]. For example, Sedláčková et al. [104] and Faé et al. [105] illustrated these differences, finding that laser diffraction exaggerated coarser fractions (>~0.01 mm) and underestimated clay (<~2 µm), compared to hydrometer or pipette determination. The differences in the methods used in determining particle size can frustrate comparison of studies and may, in part, explain the disparity in reported texture effects on soil aggregation. Therefore, caution should be applied to the interpretation of sand- and silt-related effects, and future studies should consider greater harmonization in analytical methods and better mining and reporting of the methods used.

6.1.3. Soil Organic Matter

Soil organic matter is the primary stabilizing factor in the aggregates, acting as a binding agent for primary particles [89]. Organic matter in combination with clay particles promotes chemical bonding and stability of the aggregates [90]. The type of organic matter is more important than its net amount for structural stability, as indicated by the conversion of cultivated land into pastures, which results in a faster change in the overall stability due to the change in the nature of the SOC [16].

SOM exists in various forms ranging from fresh particulate organic matter (POM) to dissolved organic matter (DOM) and mineral-associated organic matter (MAOM), each playing distinct roles in aggregate formation and stabilization [106]. During aggregate formation, POM acts as a central core, surrounded by minerals [107]. The mineral matrix protects the POM from further microbial decomposition, stabilizing the aggregates [108]. Additionally, dissolved OM plays a significant role in pedogenesis [109]. The MAOM, derived from microbial residues and tightly bound to mineral surfaces, represents a long-term stabilized carbon fraction that contributes significantly to aggregate persistence [107,110]. Excretion of organic matter by soil organisms plays an important role in aggregate formation and stability; these are involved in binding, separating, and gluing processes that alter the physical and chemical environment of the soil, thereby affecting its functional milieu [111].

Aggregate architecture relates to the presence of OM as well as the biological functioning of the pores [112]. Regions containing POM are densely packed, with low porosity, and act as reservoirs for retaining and preserving organic carbon. In contrast, porous domains composed of mineral grains coated with thin organic matter films provide sites for microbial growth and OM turnover [113]. Haq et al. [114] identified two primary locations for OM decomposition in mineral soils: rhizosphere and detritusphere. Fresh POM enhances soil microbial biomass by offering new habitats for microorganisms, while DOM promotes microbial breakdown within soil micro-aggregates [115]. These findings suggest that different forms of OM input, such as POM or DOM carbon, create distinct microenvironments that influence microbial decomposition, ultimately affecting soil structure development and aggregate formation.

6.1.4. Rhizosphere

Plant roots influence soil aggregation through several mechanisms, including, entanglement of particles, compaction and penetration, release of root exudates, as well as encouraging activities of rhizospheric bacteria and fungi [116]. The complex interplay of all these factors shapes the soil structure and aggregation in the region surrounding the roots. The availability of mucilage in the rhizosphere influences the physical and chemical properties of the soil, as well as its aggregation, by facilitating contact between the root surface and soil particles and altering the wettability of the rhizosphere through the development of mucilage networks [117]. It also quickens organo-mineral interactions in the rhizosphere. The supply of mucilage and root exudates leads to enhanced aggregation, which boosts microbial growth and the production of EPS [118]. The EPS generated by both bacteria and fungi improves aggregate stability [119]. Roots and their associated hyphae also stabilize soil structure by binding soil particles in a, sort of, “sticky string bag” that helps enhance the stability of soil aggregates. The interaction between plants, rhizobacteria, and mycorrhizal fungi creates a beneficial soil environment that not only enhances plant growth by reducing stress, retaining moisture, suppressing pathogens, and promoting nutrient turnover but also facilitates aggregate formation [120]. As evidence of the dynamic nature of biotic influences on soil structure, the inactivation of these stabilizing agents by soil fauna and microorganisms leads to the disintegration of aggregates [121].

6.1.5. Soil Organisms

Soil microbes play a key role in shaping aggregate development [122]. Microorganisms influence soil structure at the local scale through processes such as micropore (≤30 µm) alteration, local compaction, increased water content, particle alignment, and aggregate stability [123]. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), one of the oldest symbioses [124], are well-recognized for improving soil structure. Significant extraradical hyphal development in AMF has been found to be correlated with high soil stability indices [125]. Research under controlled conditions demonstrated a direct causal link between the presence of AMF mycelium and the formation of water-stable aggregates in sterilized soil [126]. The extent to which AMF promote soil aggregation varies, as different families have distinct mechanisms for forming hyphae. A meta-analysis of studies from 1986 to 2012 found an overall positive effect of AMF on soil aggregation [17]. AMF promotes the formation of organo-mineral complexes [127].

Mycorrhizal fungi also promote aggregation by influencing plant community composition and host plant root development [128]. By creating particle enmeshments, fungal hyphae contribute to the development of macro-aggregates [119,123]. EPS-producing microorganisms strengthen the structural integrity of the soil at the field scale, increasing the number of water-stable aggregates [129] by synthesizing aggregation agents [14]; for instance, microbial EPS binds and glues soil mineral particles together. Furthermore, microbial lysate products also support aggregate formation [130] and increase the OM pool in the soil [131]. The nature of binding substances excreted by microorganisms affects formation and destruction of soil aggregates. In turn, composition of soil aggregates strongly affects microbial community organization in these aggregates [105]. Emergence of distinct microbial communities in response to increasing clay content in soil aggregates has been documented, e.g., variations in bacterial communities between free aggregates and occluded aggregates have been reported, with the former supporting copiotrophic and the latter oligotrophic bacterial communities [106].

The overall soil aggregate stabilizing impact of microorganisms depends on the biologically accessible C and ambient atmosphere [132], which includes the presence of soil fauna, e.g., earthworms [133], as well as plants [118]; the former disperse microorganisms throughout the soil profile during soil processing, while the latter provide nutrients and habitat for the microbial communities. Soil biota act as ecosystem engineers that play important roles in soil aggregation by bioturbation, OM decomposition, and excretion of biogenic OM that acts as glue in aggregation [111]. The large, grazing animals affect soil C dynamics, which in turn affects the activity of microbial decomposers and their enzymes responsible for OM decomposition, nutrient cycling, and other processes [134,135]. Grazing of soil invertebrates, for example, isopods on fungi, affects buildup of fungal biomass, fungal diversity, and competition, which in turn affects litter decomposition and nutrient cycling [136]. The soil macro-fauna, like earthworms and termites, aid soil aggregate formation through the fragmentation of OM that allows its incorporation into soil aggregates [137]. In addition, soil fauna, especially larger grazing animals, are important for SOM stabilization as they affect both labile and stabilized OM through transformation, translocation, and grazing microorganisms [138]. The larger soil fauna play an important role in soil aggregation dynamics by affecting many processes such as litter fragmentation, incorporation of organic matter into aggregates, bioturbation, and the formation and breakdown of aggregates [139]. Earthworms have been shown to indirectly promote plant growth by increasing hyphal density and mycorrhizal colonization of roots [140]. Rodger et al. [141] found that plants achieved maximum biomass when earthworms facilitated the formation of a specific microbial community in the rhizosphere. Soil microfauna, including protists and nematodes, also play a crucial role in shaping the microbiome of the rhizosphere, which in turn affects plant development and health [28]. Soil macro-fauna create various biostructures, such as burrows, galleries, dejections, and mounds, which differ in structure and composition from the surrounding soil and initial organic residues.

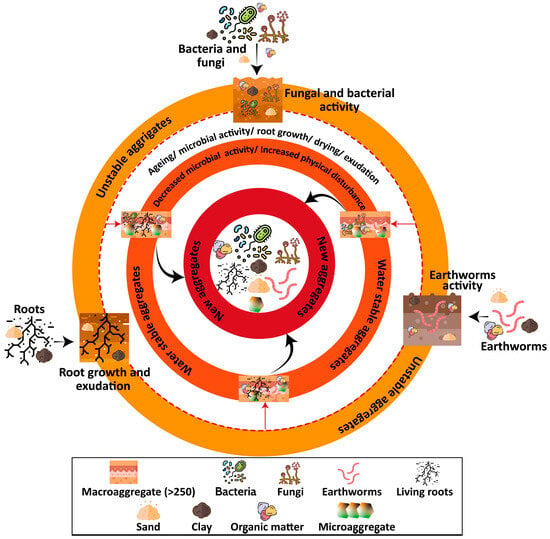

The role and activities of biotic factors in forming a macro-aggregate are shown in Figure 2. The creation of bio pores and nutrient-rich biostructures by soil fauna enhances root growth and development with implications for soil aggregate stability [142].

Figure 2.

Biological processes driving soil aggregate formation and stabilization. Roots, fungal hyphae, mycorrhizal associations, microbial exudates, and soil fauna act as binding agents, either directly by enmeshing particles or indirectly by producing polysaccharides and glomalin that strengthen aggregates. These interactions illustrate the central role of biotic activity in shaping soil structure and promoting long-term soil health.

6.1.6. Climate

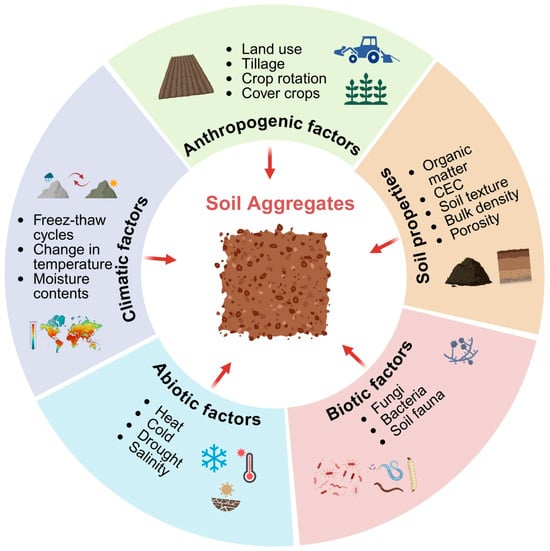

Climate has a key role in determining soil aggregation patterns. It influences the aggregation process by reorienting soil particles through the wet–dry and freeze–thaw cycles, as well as fluctuations in temperature and soil moisture content [Figure 3]. The wet and dry cycles fracture the aggregates during clay swellings, which reduces aggregate stability by separating the components [143]. According to Six et al. [14], the wetting and drying processes operate as counteracting events, causing the amount of aggregates to grow or decrease. Aggregates of different sizes differ in terms of microbial biomass and diversity, as well as C storage and cycling [144]. Microbial activity, which affects the aggregation process, also is sensitive to climatic factors [145,146]. Freeze–thaw cycles (FTCs) involve energy input and output in soil, significantly affecting soil structure by altering the arrangement and bonding of soil particles [24]. This process can re-organize the soil’s physical framework, influencing its porosity, water-holding capacity, and overall stability. The impacts of FTCs on soil aggregate stability have been discussed in several studies [40,66]. According to most of the research, FTCs reduce aggregate stability by increasing the percentage of small aggregates and decreasing the fraction of large aggregates [147]. Several investigations, however, have found that FTCs affect particle bonding, which affects aggregate stability from disruption to rebuilding [148]. The results were primarily related to soil type and aggregate stability determination technique [149], and freeze–thaw conditions (e.g., freezing temperatures, the number of FTCs, and the moisture content at freezing) [150]. Additionally, some research has shown that the detrimental effects of FTCs on aggregate stability may be mitigated by adding fertilizer, diatomite, compost made from municipal solid waste, sewage sludge, fly ash, and/or other materials to the soil [151]. According to Zhang et al. [66], variations in the OM content, particle size distribution, water stability, and mechanical strength of the soil all impact the stability of the aggregates during freeze–thaw treatments.

Figure 3.

Main drivers of aggregate formation and breakdown.

Different factors that affect the formation and stabilization of aggregates are shown in Figure 3.

6.1.7. Salinity

Soil salinity has a profound impact on soil structure, with soil salts having complex effects on aggregate formation and degradation. Salinity, mainly due to sodium ions, may not only cause dispersion of soils but can also cause structural breakdown [152]. High sodium absorption ratio (SAR) disrupts soil aggregation and structural stability by affecting various physiochemical processes in soils. Besides causing clay dispersion, high SAR reduces the stability of macro-aggregates, thereby decreasing the deposition of OM in the soil, as evident in brackish-water-irrigated cotton fields. Calcium ions can counteract these disadvantages by enhancing aggregate formation and stability [153]. Sodium being monovalent and having a high hydrated radius reduces the electrostatic attraction and increases the diffuse double layer, resulting in clay dispersion and aggregate destruction [154]. Xie et al. [155] reported that irrigation with brackish water having the SAR value of 10–20 mmol L−1 reduced the water-stable aggregate and mean weight diameter (MWD), but at SAR values below 10 mmol L−1, flocculation and organic matter retention increased due to Ca2+ ion bridging. Vieira et al. [156] state that high SAR significantly increases particle electrostatic double-layer pressure (PEDL) to lower saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ks) and further destabilize soil structure. SAR-induced dispersion, deflocculation, and swelling are significant processes of soil structural degradation, with considerable implications for water infiltration, erosion, and management of soil health.

Salts, both chlorides and sulfates, form clayey salt micro-aggregates in soils, which contribute to soil stability in arid climates [157]. Simonetti et al. [67] demonstrated that adding sodium salts to soil solutions at concentrations below 5 g L−1 promotes aggregate formation and reduces particle repulsion, resulting in more stable aggregates. Periodic alterations in soil temperatures occur due to annual variations in temperature, such as freezing and thawing cycles, with the most direct implications for the movement of water and salts in the soil. This creates zones for water and salt accumulation, which ultimately affect soil aggregate stability [158]. It leads to slaking, the primary process responsible for aggregate breakup early during rainfall, particularly due to decreased soil moisture levels following cyclic dry spells [159]. Salinity and the incorporation of organic amendments, such as straw or sewage sludge, increase aggregate stability by increasing the number of micro-aggregates and enhancing the soil’s ability to store organic carbon [30,159].

6.1.8. Soil Physico-Chemical Properties

The physico-chemical properties of the soil, including OM content, clay minerals, cation exchange capacity, soil texture, soil bulk density, and porosity, can affect soil aggregate formation and destruction [160]. OM aids aggregate stability because of its binding property, without which cohesion among soil particles would be weak; nevertheless, this binding effect can vary depending on the size of the aggregate and the mechanism of breakdown involved [161]. Soil texture, particularly the sand-to-clay ratio, influences the mechanical stability of an aggregate, whereby sandy soils disintegrate more readily due to their low cohesion and susceptibility to erosion [162]. Moreover, pH and electrical conductivity affect the electrostatic forces acting upon the soil, which, depending on the balance between attractive and repulsive forces, might stabilize or destabilize aggregates [163].

Soil bulk density and porosity also influence the formation and breakdown of soil aggregates. Low values of bulk density allow root growth and water movement, hence promoting aggregate stability and formation [67]. Conversely, high bulk density causes soil compaction, decreasing porosity and slowing down water movement, which can lead to the breakdown of aggregates [164]. Porosity affects the distribution and connectivity of macropores (>75 µm) or micropores (≤30 µm), which are key factors in water storage, air permeability, and microbial activity. In certain pore spaces where microbial access is excluded, SOC may find permanent residence in the soil and contribute to aggregate stability and C sequestration [165]. The alteration in porosity by freeze–thaw cycles results in a change in the size distribution of soil aggregates due to the breakdown of larger aggregates and the accumulation of smaller ones [41]. The bulk density-porosity relationship is thus important for sustaining aggregate cohesion and integrity.

6.2. Anthropogenic Drivers

Anthropogenic drivers of soil aggregate stability and dispersion are as under:

6.2.1. Land Use Change

Land use changes are the most crucial element influencing soil aggregation and may promote aggregate formation or breaking [125,166]. Changes in land use from natural forest to cultivated land also affect the distribution and stability of soil aggregates [18]. Beheshti et al. [167] found considerably higher soil aggregate stability in forest soil compared to bare fallow land and farmland soil. They concluded that ploughing damages soil structure and tillage causes root shredding, which reduces the stabilizing impact of root fibers. They also stated that mechanical culture increases pore spaces, resulting in higher oxygen availability for microorganisms, which leads to accelerated microbial decomposition of organic materials. Loss of SOM reduces the stability of soil aggregates. Land use changes substantially influence aggregate size and distribution and the amount of C associated with different aggregate size fractions [168]. Constant addition of leaf litter improves aggregation and stability [169]. Agricultural practices disrupt soil, breaking up the macro-aggregates, resulting in significantly larger proportions of micro-aggregates in croplands than in natural vegetation. According to Cheng-Linag et al. [170], cultivating and ploughing forest soils promotes oxidation and loss of SOM, resulting in destabilization and decreases in aggregate stability.

The distribution of nutrients and OM inside aggregates, as well as the aggregation of soil particles, is greatly influenced by the forms of land use. Adesodun et al. [171] found notable variations in the stocks of OC and N in aggregate fractions among different land use patterns. Nigerian forest soils had greater OC and N concentrations in each aggregate component than did farmed soils [171]; uncultivated rainforest soils have higher NPK concentrations in larger soil fractions than cultivated soils [172].

6.2.2. Tillage

Tillage is an important agricultural practice used for preparing seedbeds, combining fertilizers and crop residues, and controlling weeds. Tillage breaks up soil aggregates, increases bulk density, causes soil compaction, and alters microbial activity, all of which affect aggregation [173]. Tillage loosens the surface soil layers, increasing infiltration or providing temporary water storage by producing depressions on the soil surface [174]. Tillage may have an indirect influence on aggregate stability by affecting soil moisture, redistributing SOM, enhancing microbial activity, and modifying the soil solution composition and faunal population [175]. Tillage has an indirect effect on aggregate size distribution because it influences the distribution of aggregate-stabilizing chemicals such as organic bonding agents and polyvalent cations [176,177]. Li and Pang [178] showed that tillage reduced the amount of water-stable macro-aggregates, potentially due to the disruption of large macro-aggregates by physical effects or the increased rate of breakdown by plant roots. Furthermore, tillage inhibits the production of micro-aggregates inside macro-aggregates, reducing long-term C sequestration in micro-aggregates. The impact of tillage on soil aggregate stability is heavily influenced by soil moisture at the time of operation. The soil structure is most durable when tillage happens within a specific moisture range, which is notably brief in dry regions, sometimes only a few days [179]. Dry soils break into fine particles that are easily eroded, whereas overly wet soils tend to compact and decrease the pore space network. Consequently, tillage can either improve water infiltration by loosening the soil profile when moisture levels are ideal or cause increased compaction and erosion risk when moisture is suboptimal. Thus, the impact of tillage on soil density, aggregate longevity, and microbial activity depends on both the soil’s structural condition and its moisture level [180,181]. Notably, tillage promotes soil erosion by breaking up aggregates and exposing protected organic materials to microbial degradation [182]. In all, tillage may increase or decrease soil aggregate stability (Table 2).

Table 2.

Impact of tillage on soil aggregate stability.

6.2.3. Organic Amendments

Organic amendments improve aggregate stability by altering the size distribution and structural arrangement of aggregates [183]. According to Yu et al. [184], organic amendments diminish aggregate wettability and slaking by increasing aggregate cohesive power via the attraction force among mineral particles and organic polymers. Mulumba and Lal [57] investigated aggregate stability in plots with varied organic inputs and discovered that organic input-treated plots had considerably higher aggregate stability than the control plots. They found that increasing the C/N ratio of additional organic inputs improved aggregate stability in dry tropical rain-fed agro-ecosystems. Zhang et al. [185] suggested that using carbonized agricultural residue as biochar at the rate of 16 t ha−1 might help replenish deficient SOC and promote aggregate formation. According to Kahlon and Lal [186], applying ammoniated and short straws is a successful agricultural strategy for enhancing soil structural stability, as evidenced by the presence of significant amounts of water-stable aggregates, as well as increased crop output. Furthermore, long-term mulching improves soil aggregate stability and structure by protecting soil, promoting macro-fauna activity, and incorporating organic matter, all of which contribute to a high infiltration rate [187]. Sánchez-Navarro et al. [188] found that using crop leftover mulch in long-term conservational tillage increased SOC concentration through the establishment of macro-aggregates. Positive effects of organic amendments on soil aggregate stability have been observed under field as well as laboratory conditions [189,190,191,192,193]. Organic amendments increase slacking resistance in soil aggregates due to increased hydrophobicity and improved microbial activity [193]. The impact of animal manure [193,194,195], peat and wood residues [193,196,197] and treated municipal wastes [189,193,198] on soil aggregate stability has been tested with positive effect. Wheat straw increased water-stable macro-aggregates by 14.2% in a study by Sharma et al. [199]. It also increased organic carbon and aggregate mean weight diameter (8.9%) as well as aggregate ratios (36.9%). Macro-aggregates increased by 4% in sandy and 6% in loamy soils after compost addition [200]. Organic amendments also increase the rate of formation of soil aggregates [17]. However, some studies indicate a lack of consistent relationship between organic amendments and soil aggregate stability [189]; decreased soil aggregate stability after organic amendments has also been reported [78]. Thus, a stabilizing effect of organic amendments on soil aggregate stability may not be guaranteed, as it depends on many factors, including the soil type and the type of the amendments applied [194,200,201].

6.2.4. Crop Rotation

The process of crop rotation has been shown to greatly influence the formation and destruction of soil aggregates, which, in turn, control soil structure, fertility, and C sequestration. [202]. It has long been recognized that crop rotation and repeated cropping can enhance soil aggregation and mitigate soil erosion [203]. Several studies report that crop rotation promotes higher aggregate stability and a more uniform size distribution compared to monoculture systems. For example, rotations such as maize–alfalfa were reported to increase the proportion of macro-aggregates and increase SOC and nitrogen retention by increasing carbon inputs and rhizosphere activity [204]. Likewise, similar trends were reported in pulse–wheat and chickpea rotations, where the diversity of residue quality stimulates microbial binding agents and forms stable SOM fractions [202]. In addition, continuous rotation and fallow treatments have also been associated with higher macro-aggregate stability, primarily due to increased SOC [205]. The joint use of cover crops and organic inputs also improved aggregate stability and soil structure in studies carried out in Estonia and the Pacific Northwest, where reduced tillage combined with crop diversification improved infiltration capacity and mitigated soil erosion [206,207].

6.2.5. Cover Crops

Cover crops have numerous benefits for soil, including increasing C inputs, reducing erosion, enhancing cation exchange capacity (CEC), promoting aggregate stability, improving water infiltration, and recycling nutrients. However, the impact of cover crops on aggregate stability varies depending on the specific crop, agricultural rotation, and the cover crop used [208]. The effects of different crops are influenced by their unique chemical composition, rooting structure, and ability to alter the chemical and biological properties of the soil [209]. This highlights the importance of selecting appropriate cover crops to achieve specific soil improvement goals. In conventional tillage systems, the effects of crop rotations on aggregate stability are short lived and often negligible [210]. However, cover crops can have a lasting impact on soil health, including adding organic carbon, reducing erosion, increasing cation exchange capacity, enhancing aggregate stability, recycling nutrients, and improving water infiltration. Additionally, cover crop residues can stimulate soil microbial activity, leading to increased microbial biomass, respiration, and N mineralization, as well as shifts in the microbial community composition [211]. This highlights the potential of cover crops to improve soil fertility and structure.

7. Recent Techniques in Assessment of Soil Aggregate Stability

Recent technological advancements in the soil sciences have greatly improved our ability to study soil aggregate stability and dynamics. A few of these are briefly discussed below:

High-resolution imaging and computed tomography: High-resolution imaging (e.g., X-ray micro-computed tomography (µCT) and synchrotron-based imaging) allows non-destructive in situ visualization of the aggregate structure and pore networks; it provides a mechanistic understanding of how roots and microbes induce aggregation in situ [212,213,214].

Spectroscopic methods: Newly available methods like FTIR, 13C-NMR, and X-ray absorption spectroscopy allow for fine-scale examination of organo-mineral interactions and carbon stabilization in aggregates [215,216,217].

Laser diffraction or light scattering techniques: These methods provide a greater resolution in particle size distribution than classical sieving methods, specifically with micro-aggregates (<250 μm) [218].

Apart from the above techniques, new metrics are being developed and include not just weighted density means (MWD) and geometric mean diameter but also techniques developed from hydrological response (i.e., slaking tests and rainfall simulation) to link aggregate stability directly with infiltration, erosion resistance, or nutrient cycling [147,219,220]. Also, biological drivers are central to aggregate formation; the relationship between aggregate stability and microbial community metrics can be studied through metagenomics, phospholipid fatty acids, enzymatic assays, etc. [4,221,222,223]. Metagenomics, for example, enables detailed characterization of soil microbiomes, paving the way for synthetic microbial communities and targeted bioinoculants to improve soil functions.

8. Knowledge Gaps and Future Research Directions

8.1. Knowledge Gaps

Despite progress in soil aggregate dynamics research, knowledge gaps remain regarding the rate of formation, persistence, and destabilization of the soil aggregates. Measurements are mostly on static aggregates, and dynamics over time are not known. There is a lack of standardized methodology to facilitate comparison at the landscape or global level. Although the anthropogenic drivers of aggregate dynamics have been studied, their impact under various soil and climate types remains poorly studied. Moreover, there is a need for understanding microbiome–soil–plant interactions under stress and addressing contamination effects on soil aggregate formation and stability.

8.2. Future Directions

Climate Change Adaptation: Climate change affects all aspects of the soil environment, including soil aggregate formation and stability. Climatic variability imposes stress on physical parameters, challenging soil resilience and necessitating adaptive management. Therefore, strategies such as conservation agriculture, agroforestry, microbial amendments, and resilient cropping systems are needed to buffer soils against climate stress and maintain soil functions. Also, the future studies should explicitly connect soil aggregate stability to ecosystem vulnerability under climate change scenarios (drought, floods, freeze–thaw cycle).

Soil–Microbiome–Aggregate Interaction: Advances in metagenomics, the use of stable isotope tracing, and machine learning can uncover the spatial and temporal dynamics of soil aggregates and their microbial constituents. Incorporating such data into agroecological models will improve the prediction of soil responses to management and environmental change. Moreover, emerging biotechnologies, such as microbial consortia, engineered bioinoculants, and rhizosphere-targeted amendments, offer promising solutions for enhancing aggregation in degraded soils. These tools should be developed with ecological safety, site specificity, and farmer participation in mind.

Land Management Practices: There is an urgent need for globally distributed long-term studies that assess aggregate behavior across biomes, land uses, and management systems. Such efforts will facilitate the development of region-specific indicators and scalable soil health interventions.

High-Resolution Tools: Advanced imaging tools (e.g., synchrotron-based X-ray tomography, nanoscale 3D imaging) and machine learning approaches can uncover the spatial and temporal dynamics of aggregate formation. Integration of such data into agroecosystem and Earth system models could dramatically improve predictions of soil responses to management and climate change.

Policy and Knowledge Interaction: Aggregation should be embedded into agricultural and environmental policy frameworks as a measurable and manageable indicator of land quality. Collaborative strategies involving researchers, land managers, farmers, and policymakers can ensure effective translation of science into practice. Educational programs and knowledge co-production with local communities will also be key to widespread adoption.

9. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Soil aggregate formation and stability are fundamental processes that underpin soil structure, influence ecosystem services, and serve as vital indicators of soil health. Soil aggregation patterns strongly affect vital soil functions (water retention, C sequestration, and nutrient availability) and ecosystem services (biodiversity, microhabitat, and resistance to erosion). Declines in aggregate stability impact soil health by disrupting nutrient cycles, limiting carbon sequestration, and reducing water regulation, as well as biodiversity.

This review synthesized the multifaceted mechanisms governing soil aggregation, including the roles of soil organic matter, mineralogy, microbial communities, plant roots, and land-use practices, and highlighted their influence on soil aggregate stability/disintegration. It brought to light how stable aggregates enhance water infiltration, nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration, erosion resistance, and biological activity, thereby supporting long-term soil productivity and ecological resilience. Our review emphasizes that sustainable management practices, such as conservation tillage, organic amendments, cover cropping, and diversified crop rotations, consistently improve soil aggregate stability. However, despite significant advances, the integration of soil aggregation processes into broader frameworks for climate resilience, agroecosystem modelling, and policy design remains limited. There is a critical need to elevate soil aggregation as a central concept in sustainable land management and environmental restoration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H., D.K. and I.U.; software, A.H. and M.Z.M.; investigation, I.U. and I.M.; resources, D.K. and R.R.; data curation, M.A.T., N.R. and A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H. and D.K.; writing—review and editing, A.H., N.R. and I.U. Visualization, S.S.L. and S.K.; supervision, D.K. and I.U.; project administration, D.K. and I.M.; funding acquisition, D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by internal doctoral study budget of Lithuanian Research Center for Agriculture and Forestry, grant number VĖŽDOK402.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable time, insightful comments, and constructive suggestions that greatly enhanced the quality of this manuscript. A.H. extends special thanks to Manzoor R. Khan, Department of Botany, Aligarh Muslim University, for his thoughtful comments and recommendations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SOM | Soil Organic Matter |

| OM | Organic Matter |

| SOC | Soil Organic Carbon |

| OC | Organic Carbon |

| POM | Particulate Organic Matter |

| DOM | Dissolved Organic Matter |

| SSS | Soil Structure Stability |

| SAS | Soil Aggregate Stability |

| EPS | Extracellular Polymeric Substances |

| AMF | Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi |

| SAR | Sodium Absorption Ratio |

| ECE | Cation Exchange Capacity |

References

- Devine, S.; Markewitz, D.; Hendrix, P.; Coleman, D. Soil aggregates and associated organic matter under conventional tillage, no-tillage, and forest succession after three decades. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, S.; Sharma, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Kumar, M.; Rao, C.S.; Nataraj, K.; Singh, G.; Vinu, A.; Bhowmik, A.; Sharma, H. Biochar modulating soil biological health: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 169585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angers, D.; Carter, M. Aggregation and organic matter storage in cool, humid agricultural soils. In Structure and Organic Matter Storage in Agricultural Soils; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 193–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaduri, D.; Sihi, D.; Bhowmik, A.; Verma, B.C.; Munda, S.; Dari, B. A review on effective soil health bio-indicators for ecosystem restoration and sustainability. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 938481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, B. Soil structure and organic carbon: A review. In Soil Process. Carbon Cycle; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 169–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chan, K.; Oates, A.; Heenan, D.; Huang, G. Relationship between soil structure and runoff/soil loss after 24 years of conservation tillage. Soil Tillage Res. 2007, 92, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, K.; Rajvanshi, M.; Chugh, N.; Dixit, R.B.; Kumar, G.R.K.; Kumar, C.; Sagaram, U.S.; Dasgupta, S. Microalgal applications toward agricultural sustainability: Recent trends and future prospects. In Microalgae; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 339–379. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, P.; Garg, N.; Lakaria, B.L.; Biswas, A.; Rao, A.S. Soil and residue carbon mineralization as affected by soil aggregate size. Soil Tillage Res. 2012, 121, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiky, M.R.K.; Schaller, J.; Caruso, T.; Rillig, M.C. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and collembola non-additively increase soil aggregation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 47, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, G.; Wang, L.; Yu, X. Contributions of biotic and abiotic factors to soil aggregation under different thinning intensities. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 139, 108958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Řezáčová, V.; Czakó, A.; Stehlík, M.; Mayerová, M.; Šimon, T.; Smatanová, M.; Madaras, M. Organic fertilization improves soil aggregation through increases in abundance of eubacteria and products of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomiero, T. Soil degradation, land scarcity and food security: Reviewing a complex challenge. Sustainability 2016, 8, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbi, S.F.; Wilson, B.R.; Lockwood, P.V.; Daniel, H.; Young, I.M. Soil organic carbon mineralization rates in aggregates under contrasting land uses. Geoderma 2014, 216, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Frey, S.D.; Thiet, R.K.; Batten, K. Bacterial and fungal contributions to carbon sequestration in agroecosystems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2006, 70, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guhra, T.; Stolze, K.; Totsche, K.U. Pathways of biogenically excreted organic matter into soil aggregates. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 164, 108483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totsche, K.U.; Amelung, W.; Gerzabek, M.H.; Guggenberger, G.; Klumpp, E.; Knief, C.; Lehndorff, E.; Mikutta, R.; Peth, S.; Prechtel, A. Microaggregates in soils. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2018, 181, 104–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucka, F.B.; Kölbl, A.; Uteau, D.; Peth, S.; Kögel-Knabner, I. Organic matter input determines structure development and aggregate formation in artificial soils. Geoderma 2019, 354, 113881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Elliott, E.T.; Paustian, K. Soil macroaggregate turnover and microaggregate formation: A mechanism for C sequestration under no-tillage agriculture. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 2099–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabot, E.; Wiesmeier, M.; Schlüter, S.; Vogel, H.-J. Soil structure as an indicator of soil functions: A review. Geoderma 2018, 314, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.; Muhlack, R.; Morton, B.J.; Dunnigan, L.; Chittleborough, D.; Kwong, C.W. Pyrolysis temperature effects on biochar–water interactions and application for improved water holding capacity in vineyard soils. Soil Syst. 2019, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, P.D. A brief overview of the causes, impacts and amelioration of soil water repellency–a review. Soil Water Res. 2008, 3, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Zhang, K.; Chen, B. Linking hydrophobicity of biochar to the water repellency and water holding capacity of biochar-amended soil. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 253, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, M.; Van De Wiel, M.; Holtzman, R. Hydrological vs. mechanical impacts of soil water repellency on erosion. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2025, 261, 105022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.; Park, D.M. Food security in a changing climate starts with managing soil water repellency. Geoderma 2024, 447, 116922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, T.C.; Incerti, G.; Spaccini, R.; Piccolo, A.; Mazzoleni, S.; Bonanomi, G. Linking organic matter chemistry with soil aggregate stability: Insight from 13C NMR spectroscopy. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 117, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhu, H.; Shutes, B.; Rousseau, A.N.; Feng, W.-D.; Hou, S.-N.; Ou, Y.; Yan, B.-X. Soil aggregate-driven changes in nutrient redistribution and microbial communities after 10-year organic fertilization. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 348, 119306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Cao, C.; Feng, Y.; Miao, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, S. Influence of long-term ecological reclamation on carbon and nitrogen cycling in soil aggregates: The role of bacterial community structure and function. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Luo, X.; Xiong, X.; Chen, W.; Hao, X.; Huang, Q. Soil aggregate stratification of ureolytic microbiota affects urease activity in an inceptisol. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 11584–11590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, Y.; She, D.; Tang, S.; Wang, H.; Sun, X.; Han, X.; Liu, D. Assessing Roles of Aggregate Structure on Hydraulic Properties of Saline/Sodic Soils in Coastal Reclaimed Areas. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, P.; Yin, Z.; Li, A.; Zhou, X.; Qi, Z.; Wang, B. Soil aggregates and water infiltration performance of different water and soil conservation measures on phaeozems sloping farmland in northeast China. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers, C.; Berli, M.; Accorsi, M.; Or, D. Permeability of deformable soft aggregated earth materials: From single pore to sample cross section. Water Resour. Res. 2007, 43, W08424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullatif, Y.; Soliman, E.; Hammad, S.; El-Ghamry, A.; Mansour, M. Impact of carbon nanoparticles on aggregation and carbon sequestration under soil degradation–a review. J. Soil Sci. Agric. Eng. 2024, 15, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, M.; Jia, X.; Lair, G.; Faraj, P.; Blaud, A. Analysing the impact of compaction of soil aggregates using X-ray microtomography and water flow simulations. Soil Tillage Res. 2015, 150, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leer, M.D.; Zaadnoordijk, W.J.; Zech, A.; Buma, J.; Harting, R.; Bierkens, M.F.; Griffioen, J. Dominant factors determining the hydraulic conductivity of sedimentary aquitards: A random forest approach. J. Hydrol. 2023, 627, 130468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Swan, J.; Nieber, J.; Allmaras, R. Soil-macropore and layer influences on saturated hydraulic conductivity measured with borehole permeameters. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1993, 57, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorner, J.; Sandoval, P.; Dec, D. The role of soil structure on the pore functionality of an Ultisol. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2010, 10, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wang, Q.; Duan, C.; Huang, G.; Dong, K.; Wang, C. Biochar addition promotes soil organic carbon sequestration dominantly contributed by macro-aggregates in agricultural ecosystems of China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 359, 121042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Yang, L. Continuous straw returning enhances the carbon sequestration potential of soil aggregates by altering the quality and stability of organic carbon. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 358, 120903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Fan, H.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, R. Evaluation of soil macro-aggregate characteristics in response to soil macropore characteristics investigated by X-ray computed tomography under freeze-thaw effects. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 225, 105559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Hu, C.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, H.; Zou, L.; Zhou, W.; Gao, H.; Ren, X.; Wang, J. Artificial utilization of saline-sodic land promotes carbon stock: The importance of large macroaggregates. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Xu, G.; Wang, X.; Li, P.; Dang, X.; Jiang, W.; Ma, T.; Wang, B.; Gu, F.; Li, Z. Contribution of soil aggregate particle size to organic carbon and the effect of land use on its distribution in a typical small watershed on Loess Plateau, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 110988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Gsell, T.; Yunger, J.; Randa, L.; Peng, Y.; Carrington, M. Soil Aggregation, Aggregate Stability, and Associated Soil Organic Carbon in Huron Mountains Forests, Michigan, USA. Forests 2025, 16, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeb, M.; Groffman, P.M.; Amato, M.; Cheng, Z.; Giménez, D. Characterization of soil aggregates in green bioswales in relation to carbon sequestration, aggregate stability, and microbial activity. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, Vienna, Austria, 14–19 April 2024; p. 21211. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, J.; Zou, H.; Xia, X.; Dan, C.; Liu, C.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G. Response of soil aggregate disintegration to antecedent moisture during splash erosion. Catena 2024, 234, 107633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.G.; Loss, A.; Batista, I.; Melo, T.R.d.; Silva, E.C.d.; Pinto, L.A.d.S.R. Biogenic and physicogenic aggregates: Formation pathways, assessment techniques, and influence on soil properties. Rev. Bras. Ciência Solo 2021, 45, e0210108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Xu, C.; Ma, R.; Tu, K.; Yang, J.; Zhao, S.; Yang, M.; Zhang, F. Biochar application driven change in soil internal forces improves aggregate stability: Based on a two-year field study. Geoderma 2021, 403, 115276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, F.; Shi, H.; Gou, J.; Zhang, L.; Dai, Q.; Yan, Y. Responses of soil aggregate stability and soil erosion resistance to different bedrock strata dip and land use types in the karst trough valley of Southwest China. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2024, 12, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, M.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Peng, X. Effects of residue stoichiometric, biochemical and C functional features on soil aggregation during decomposition of eleven organic residues. Catena 2021, 202, 105288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.P.C. Soil Erosion and Conservation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Ji, L.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Tan, W. Spatial contribution of environmental factors to soil aggregate stability in a small catchment of the Loess Plateau, China. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Cai, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Xiao, T.; Peng, G.; Yang, W. Evaluation of soil aggregate microstructure and stability under wetting and drying cycles in two Ultisols using synchrotron-based X-ray micro-computed tomography. Soil Tillage Res. 2015, 149, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeler, E.; Marschner, P.; Tscherko, D.; Singh Gahoonia, T.; Nielsen, N.E. Microbial community composition and functional diversity in the rhizosphere of maize. Plant Soil 2002, 238, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, N.; Kader, M.A.; Al-Solaimani, S.G.; Abd El-Wahed, M.H.; Abohassan, R.A.; Charles, M.E. A review of impacts of hydrogels on soil water conservation in dryland agriculture. Farming Syst. 2025, 3, 100166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Singh, S.; Ghoshal, N. Soil aggregates: Formation, distribution and management. In New Approaches in Biological Research; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, P.R.; Nair, V.D.; Kumar, B.M.; Showalter, J.M. Carbon sequestration in agroforestry systems. Adv. Agron. 2010, 108, 237–307. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, S.; Hussain, S.; Guo, R.; Sarwar, M.; Ren, X.; Krstic, D.; Aslam, Z.; Zulifqar, U.; Rauf, A.; Hano, C. Carbon sequestration to avoid soil degradation: A review on the role of conservation tillage. Plants 2021, 10, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulumba, L.N.; Lal, R. Mulching effects on selected soil physical properties. Soil Tillage Res. 2008, 98, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayu, T. Systematic review on the role of microbial activities on nutrient cycling and transformation implication for soil fertility and crop productivity. bioRxiv 2024. bioRxiv:2024.2009.2002.610905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, N.; Dinkar, S.; Singh, S.; Kumar, M.; Deepak, S.; Singh, S. Soil Microbiome and Nutrient Cycling: Implications for Sustainable Agriculture. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2025, 31, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Shi, D.; Ni, S.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Song, G. Effects of soil erosion and soil amendment on soil aggregate stability in the cultivated-layer of sloping farmland in the Three Gorges Reservoir area. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 223, 105447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galic, M.; Percin, A.; Bogunovic, I. Soil C-CO2 Emissions Across Different Land Uses in a Peri-Urban Area of Central Croatia. Land 2025, 14, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Niu, W.; Cao, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Duan, X.; Zhang, Z. Effect of soil aeration on root morphology and photosynthetic characteristics of potted tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum) at different NaCl salinity levels. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]