Evaluation of Allyl Isothiocyanate and Ethylicin as Potential Substrate and Space Fumigants in Tomato Greenhouses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cultivation Substrate and Greenhouse Space Disinfestation

2.2. Pathogen Analysis

2.2.1. Cultivation Substrate Sampling and Storage Conditions

2.2.2. Greenhouse Space Sampling and Storage Requirements

2.2.3. Pathogen Isolation and Quantification

2.3. Analysis of Microbial Diversity in Cultivation Substrate Samples

2.3.1. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

2.3.2. High-Throughput Sequencing of Substrate Samples and Bioinformatic Analysis

2.4. Investigation of Tomato Growth and Yield

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

3. Results

3.1. Effect of the Treatments on Fungal Pathogens in the Substrate

3.2. Effects of Fumigation on Fusarium spp. and Phytophthora spp. in Greenhouse Space

3.3. Bacterial Microbial Diversity Analysis in Substrate Samples

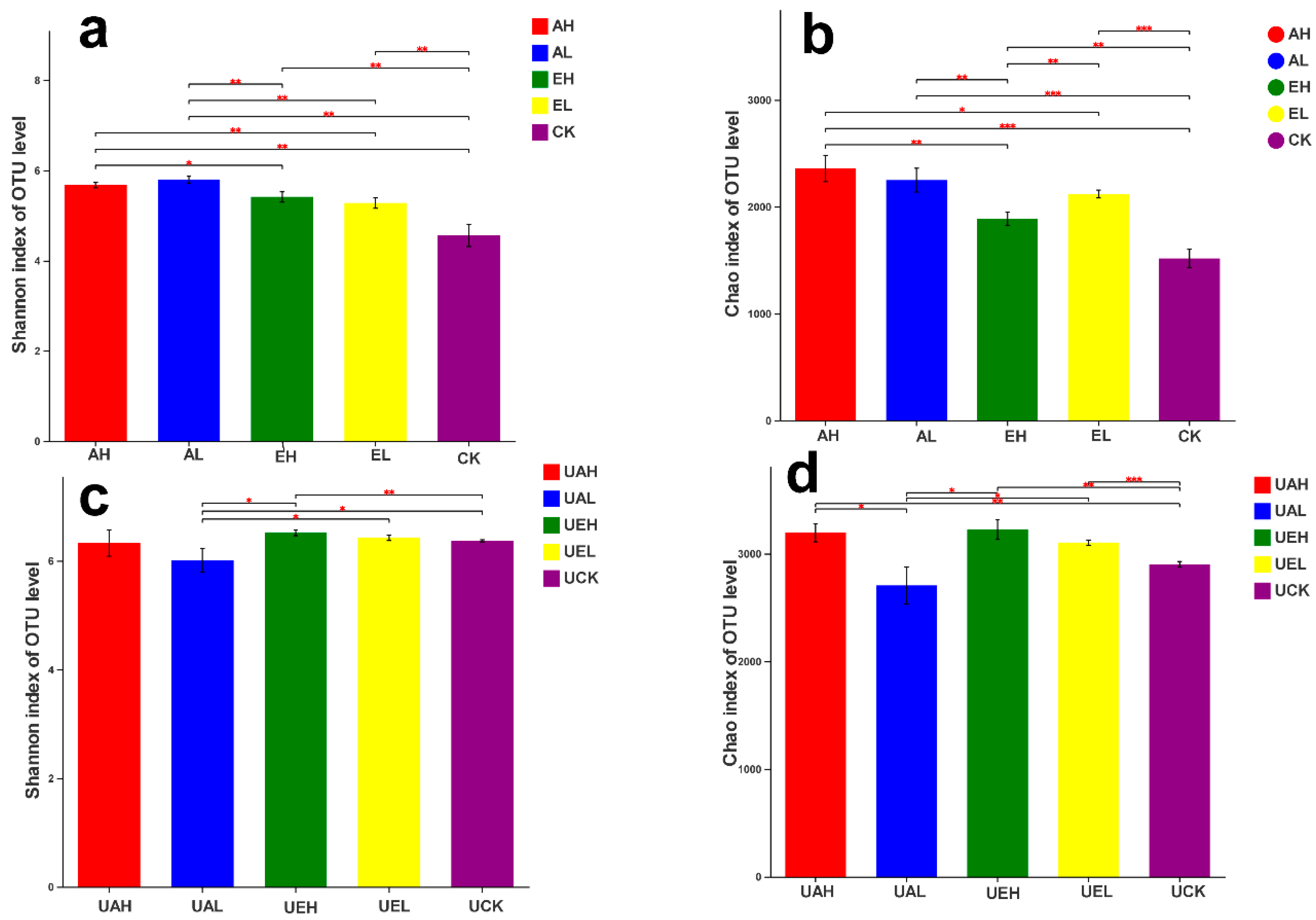

3.3.1. Bacterial Diversity Index Analysis

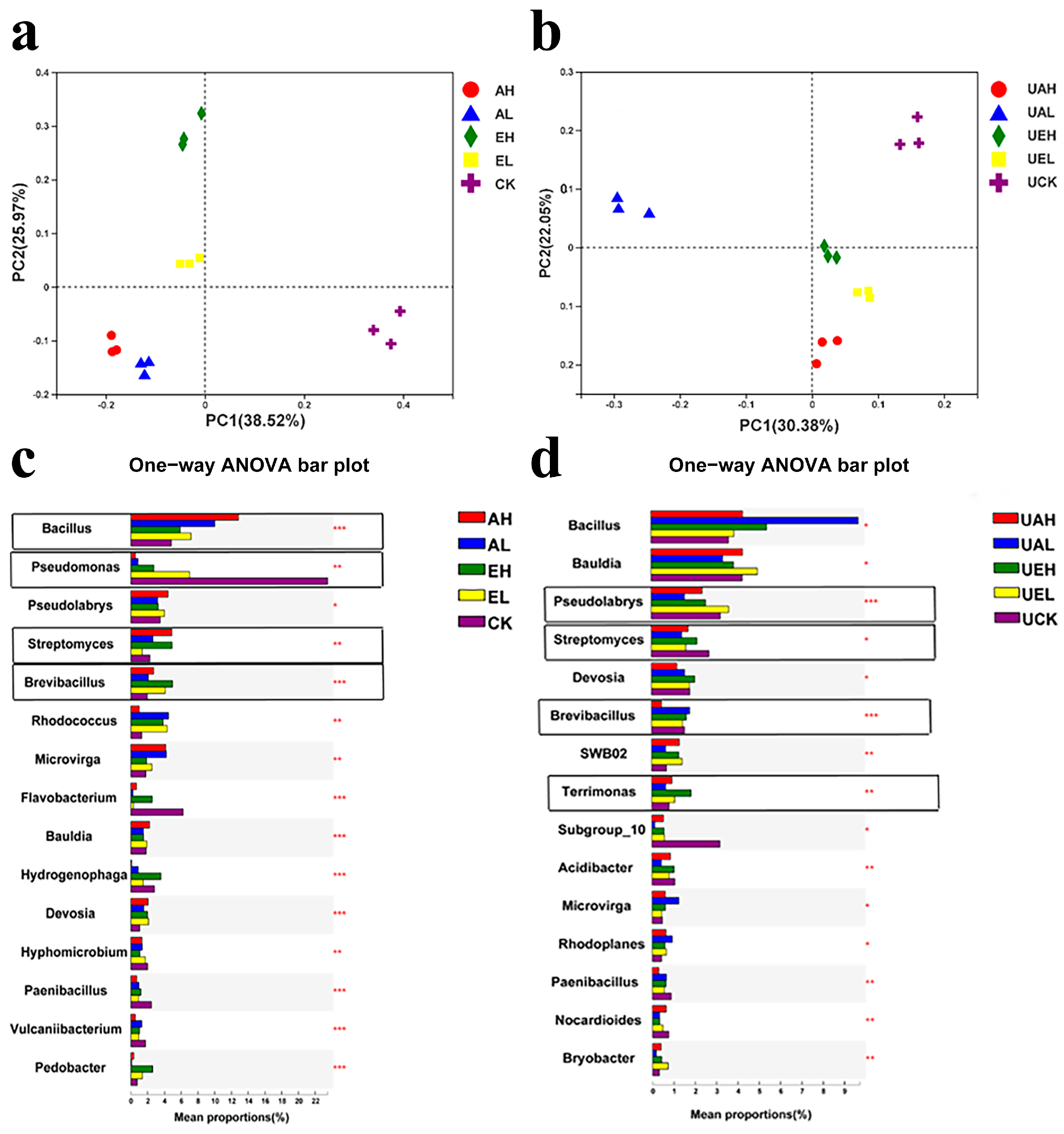

3.3.2. Principal Coordinate Analysis of Bacterial Community in Substrate Samples

3.3.3. Analysis of Differences in Bacterial Community Composition in Substrate Samples

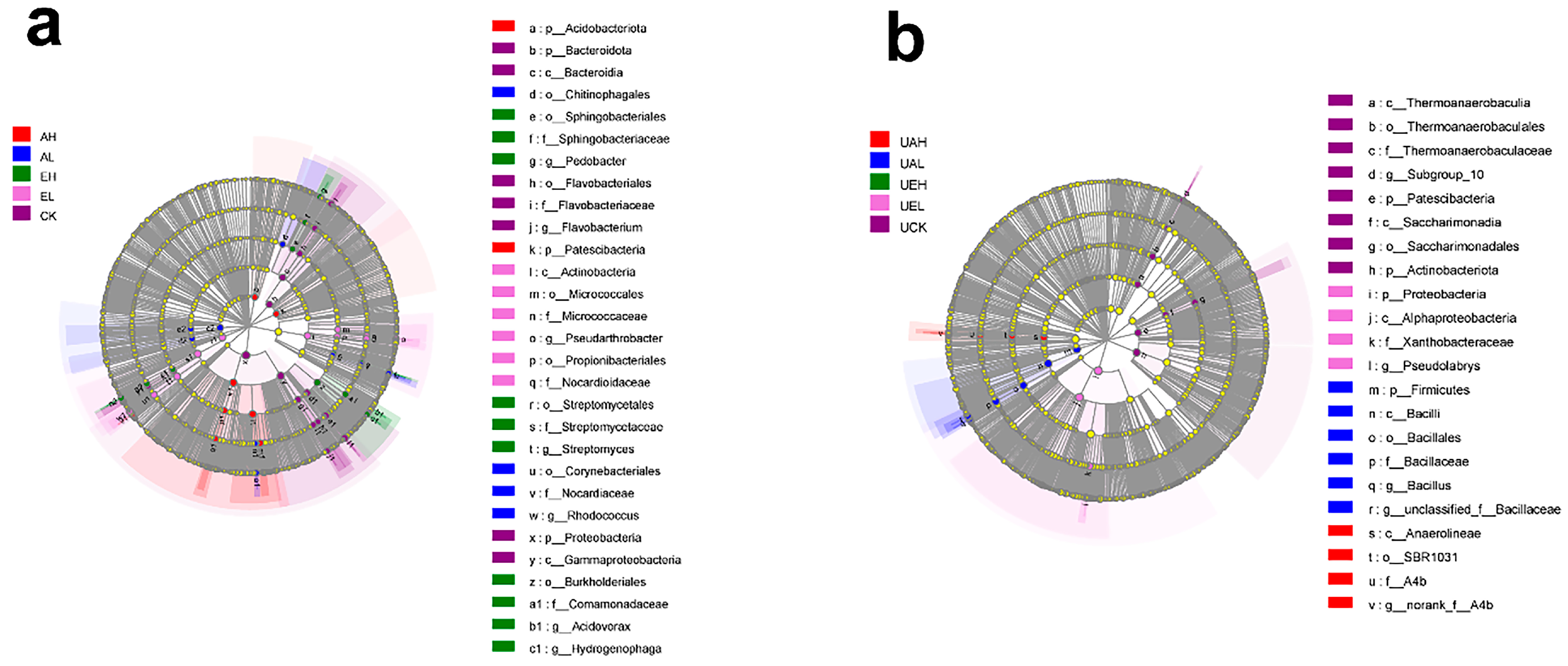

3.3.4. LEfSe Analysis of Differences in Bacterial Community Composition in Substrate Samples

3.4. Fungal Microbial Diversity Analysis in Substrate Samples

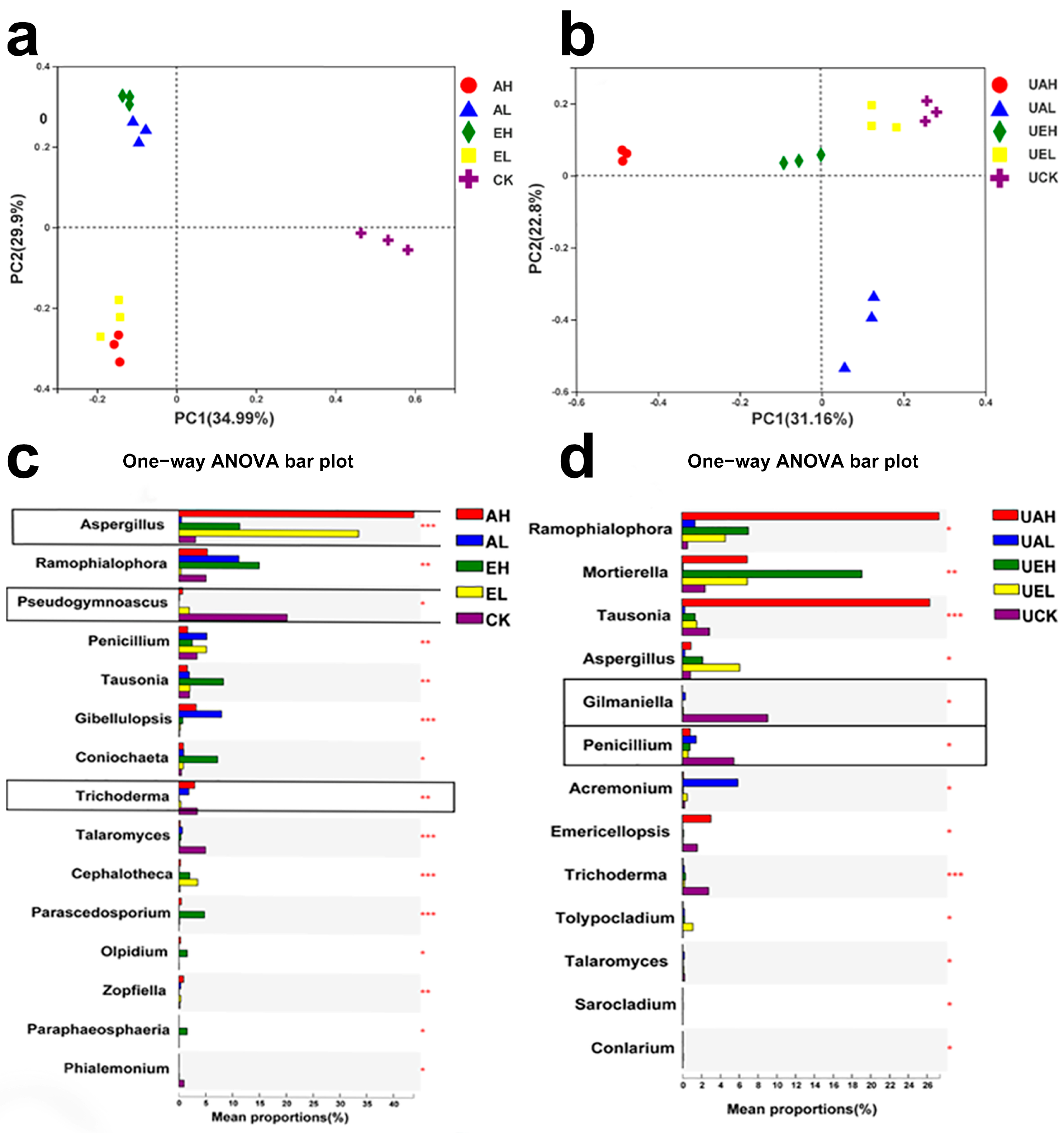

3.4.1. Fungal Diversity Index Analysis

3.4.2. Principal Coordinate Analysis of Fungal Community in Substrate

3.4.3. Analysis of Differences in Fungal Community Composition in Substrate

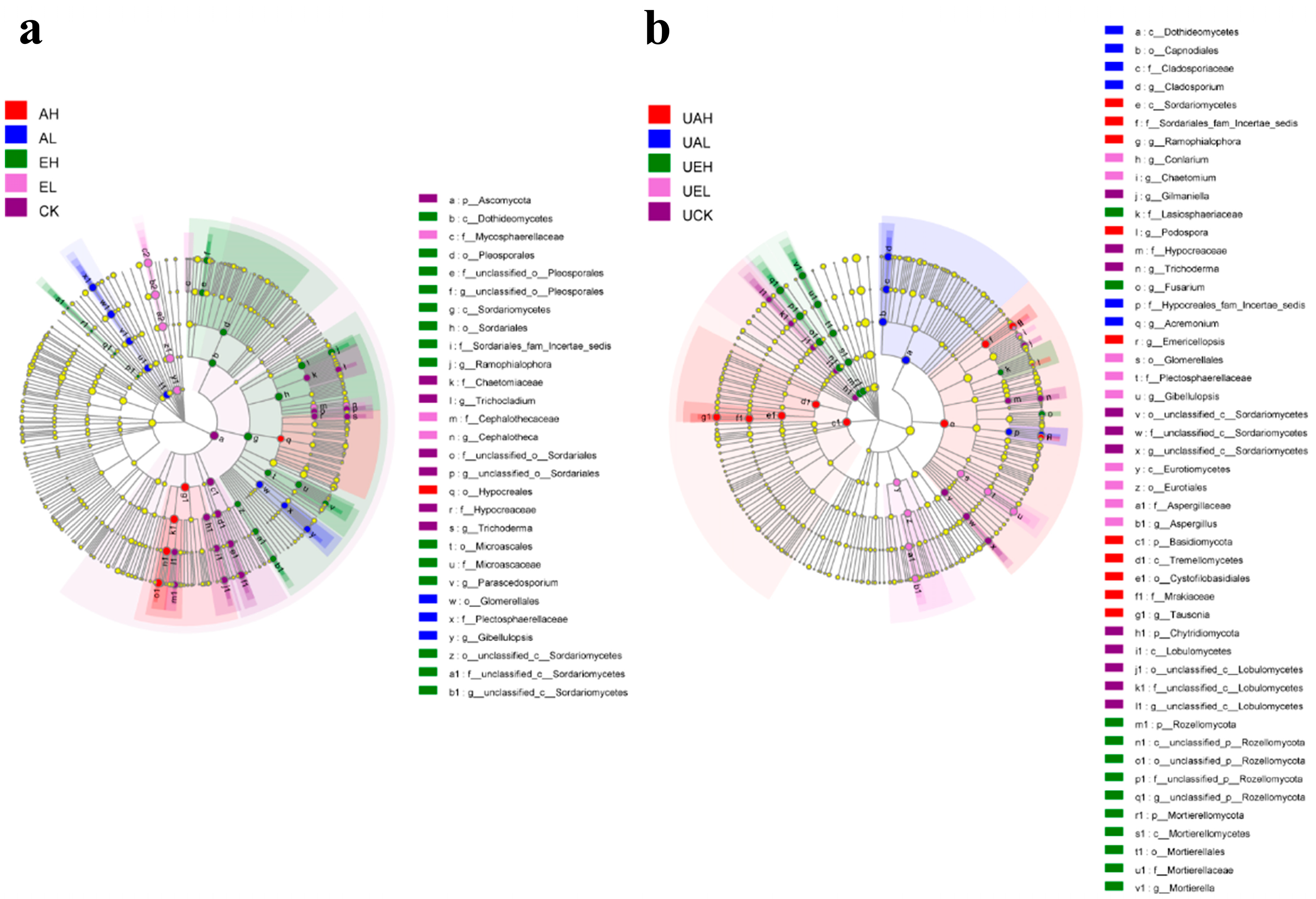

3.4.4. LEfSe Analysis of Differences in Fungal Community Composition in Substrate

3.5. Significant Improvement of Tomato Yield

4. Discussion

4.1. Investigation and Monitoring of Fusarium spp. and Phytophthora spp. in Substrate

4.2. Detection of Pathogens in the Space of Tomato Greenhouse

4.3. Analysis of Microbial Diversity of Substrate

4.3.1. Analysis of Taxonomic Diversity

4.3.2. Difference Analysis of Community Composition

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Chen, Z.; Wu, Z.; Gao, J. A convolutional neural network for large-scale greenhouse extraction from satellite images considering spatial features. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castello, I.; Baglieri, A.; Montoneri, E.; Vitale, A. Utilization of municipal biowaste-derived compounds to reduce soilborne fungal diseases of tomato: A further step toward circular bioeconomy. GCB Bioenergy 2025, 17, 70027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castello, I.; D’Emilio, A.; Danesh, Y.; Vitale, A. Enhancing the effects of solarization-based approaches to suppress Verticillium dahliae inocula affecting tomato in greenhouse. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, G.E.; Alexander, P.D.; Robinson, J.S. Achieving environmentally sustainable growing media for soilless plant cultivation systems—A review. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 212, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Du, X. Effects of different straw breeding substrates on the growth of tomato seedlings and transcriptome analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodge, A.; Berta, G.; Doussan, C. Plant root growth, architecture and function. Plant Soil 2009, 321, 153–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagne, V.; Capiaux, H.; Cannavo, P. Protective effect of organic substrates against soil-borne pathogens in soilless cucumber crops. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 206, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, B. Role of bacterial pathogens in microbial ecological networks in hydroponic plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1403226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sela Saldinger, S.; Rodov, V.; Kenigsbuch, D. Hydroponic agriculture and microbial safety of vegetables: Promises, challenges, and solutions. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, J. Research status and prospects of organic cultivation substrates. North. Hortic. 2011, 172–176. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Guo, S.; Li, X. Effects of disinfection, companion planting, and microbial agents on the properties of continuous cropping substrates and the growth and development of cucumbers. Northwest J. Plants 2023, 43, 1136–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Ren, L.; Li, Q. Evaluation of ethylicin as a potential soil fumigant in commercial tomato production in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlin, P.; Hallmann, J. New Insights on the Role of Allyl Isothiocyanate in Controlling the Root Knot Nematode Meloidogyne hapla. Plants 2020, 9, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.; Kathuria, A.; Lee, Y.S. Effect of hydrophilic and hydrophobic cyclodextrins on the release of encapsulated allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) and their potential application for plastic film extrusion. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 48137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, D. Fumigation alters the manganese-oxidizing microbial communities to enhance soil manganese availability and increase tomato yield. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 919, 170882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, C.; Bian, X. Nematicidal efficacy of isothiocyanates against root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica in cucumber. Crop Prot. 2011, 30, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, W.; Yan, D. Encapsulated allyl isothiocyanate improves soil distribution, efficacy against soil-borne pathogens and tomato yield. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 4583–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, W.; Yan, D. Comparison of drip-irrigated or injected allyl isothiocyanate against key soil-borne pathogens and weeds. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 3860–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, G. Ethylicin inhibition of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola in vitro and in vivo. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, M.; Khalid, A.R. Ethylicin prevents potato late blight by disrupting protein biosynthesis of Phytophthora infestans. Pathogens 2020, 9, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Zhang, M.; Chen, G. Evaluation of newly combination of Trichoderma with dimethyl disulfide fumigant to control Fusarium oxysporum, optimize soil microbial diversity and improve tomato yield. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 292, 117903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komada, H. Development of a selective medium for quantitative isolation of Fusarium oxysporum from natural soil. Rev. Plant Prot. Res. 1975, 8, 114–124. [Google Scholar]

- Masago, H.; Yoshikawa, M.; Fukada, M. Selective inhibition of Pythium spp. on a medium for direct isolation of Phytophthora spp. from soils and plants. Phytopathology 1977, 67, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Tan, G.; Wang, H. Effect of biochar additions to soil on nitrogen leaching, microbial biomass and bacterial community structure. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2016, 74, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Miletto, M.; Taylor, J. Dispersal in microbes: Fungi in indoor air are dominated by outdoor air and show dispersal limitation at short distances. ISME J. 2013, 7, 1262–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Chen, R.; Zhao, L. Chemical fumigants control apple replant disease: Microbial community structure-mediated inhibition of Fusarium and degradation of phenolic acids. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 440, 129786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Zhang, D.; Ren, L. Bio-activation of soil with beneficial microbes after soil fumigation reduces soil-borne pathogens and increases tomato yield. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 283, 117160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Li, Y.; Fang, W. Evaluation of allyl isothiocyanate as a soil fumigant against soil-borne diseases in commercial tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) production in China. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018, 74, 2146–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Fang, W. Soil properties, presence of microorganisms, application dose, soil moisture and temperature influence the degradation rate of allyl isothiocyanate in soil. Chemosphere 2020, 244, 125540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Ajwa, H.A.; Westerdahl, B.B. Multitactic preplant soil fumigation with allyl isothiocyanate in cut flowers and strawberry. HortTechnology 2020, 30, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Lacombe, A.; Rane, B. Scaling up gaseous chlorine dioxide (ClO2) treatment in the cold storage of fresh apples. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 217, 113118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakta, B.; Yamane, S.; Bhakta, J.N. Microbial control in greenhouses by spraying slightly acidic electrolyzed water. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefri, U.H.N.M.; Khan, A.; Lim, Y.C. A systematic review on chlorine dioxide as a disinfectant. J. Med. Life 2022, 15, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koide, S.; Shitanda, D.; Note, M. Effects of mildly heated, slightly acidic electrolyzed water on the disinfection and physicochemical properties of sliced carrot. Food Control 2011, 22, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.M.; Li, L.; Zhang, F.S. Acid phosphatase role in chickpea/maize intercropping. Ann. Bot. 2004, 94, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Yan, D.; Wang, X. Evidences of N2O emissions in chloropicrin-fumigated soil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 11580–11591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, B.; Wang, Q. Effect of fumigation with chloropicrin on soil bacterial communities and genes encoding key enzymes involved in nitrogen cycling. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 227, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Yan, D.; Wang, X. Responses of nitrogen-cycling microorganisms to dazomet fumigation. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, X.; Jiang, Q. Legacy effects of continuous chloropicrin-fumigation for 3-years on soil microbial community composition and metabolic activity. AMB Express 2017, 7, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Ren, Z.; Huang, B. Effects of fumigation with allyl isothiocyanate on soil microbial diversity and community structure of tomato. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanowicz, K.J.; Freedman, Z.B.; Upchurch, R.A. Active microorganisms in forest soils differ from the total community yet are shaped by the same environmental factors: The influence of pH and soil moisture. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollister, E.B.; Hu, P.; Wang, A.S. Differential impacts of brassicaceous and nonbrassicaceous oilseed meals on soil bacterial and fungal communities. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2013, 83, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Huang, H. Contrasting beneficial and pathogenic microbial communities across consecutive cropping fields of greenhouse strawberry. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 5717–5729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawicha, P.; Laopha, A.; Chamnansing, W. Biocontrol and plant growth-promoting properties of Streptomyces isolated from vermicompost soil. Indian Phytopathol. 2020, 73, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangola, S.; Bhandari, G.; Joshi, S. Esterase and ALDH dehydrogenase-based pesticide degradation by Bacillus brevis 1B from a contaminated environment. Environ. Res. 2023, 232, 116332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Deng, R. Mechanisms of manganese-tolerant Bacillus brevis MM2 mediated oxytetracycline biodegradation process. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 363, 125060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van De Veerdonk, F.L.; Gresnigt, M.S.; Romani, L. Aspergillus fumigatus morphology and dynamic host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadhukhan, R.; Jatav, H.S.; Sen, S. Biological nitrification inhibition for sustainable crop production. In Plant Perspectives to Global Climate Changes; Aftab, T., Roychoudhury, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 135–150. ISBN 978-0-323-85665-2. [Google Scholar]

- Negawo, W.J.; Beyene, D.N. The role of coffee based agroforestry system in tree diversity conservation in Eastern Uganda. J. Landsc. Ecol. 2017, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, S.; Verma, U. State space modelling and forecasting of sugarcane yield in Haryana, India. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2017, 9, 2036–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Dosage (g/m2) | Label 1 | Post-Treatment Time | Label 2 | Post-Treatment Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated control | CK | UCK | |||

| AITC | 14 | AH | after 7 days of fumigation | UAH | at the time of seedling planting |

| AITC | 7 | AL | UAL | ||

| ethylicin | 8 | EH | UEH | ||

| ethylicin | 4 | EL | UEL | ||

| Treatment | Dose (g/m2) | Fusarium spp. (%) | Phytophthora spp. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AH | 14 | 94.2 ± 4.60 a | 73.9 ± 3.48 b |

| AL | 7 | 87.4 ± 7.99 a | 69.2 ± 4.06 b |

| EH | 8 | 68.9 ± 4.63 b | 87.5 ± 2.35 a |

| EL | 4 | 67.0 ± 1.99 b | 61.7 ± 4.89 c |

| CK | - | - |

| Treatment | Dose (g/m2) | Spatial Location | Fusarium spp. | Phytophthora spp. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Fumigation | After Fumigation | Inhibition Rate (%) | Before Fumigation | After Fumigation | Inhibition Rate (%) | |||

| AH | 14 | film | 13.2 ± 2.71 c | 0 | 100.0 | 133.5 ± 34.32 d | 5.23 ± 3.33 e | 96.2 ± 1.22 a |

| ground | 65.34 ± 12.87 a | 0 | 100.0 | 435.16 ± 61.12 b | 30 ± 3.45 c | 93.1 ± 0.26 b | ||

| AL | 7 | film | 30.23 ± 8.14 b | 0 | 100.0 | 195.34 ± 24.77 c | 18 ± 2.59 d | 90.7 ± 0.74 c |

| ground | 45.22 ± 11.37 a | 0 | 100.0 | 124.85 ± 18.72 d | 11 ± 4.28 e | 91.1 ± 1.53 bc | ||

| EH | 8 | film | 16.43 ± 3.77 c | 0 | 100.0 | 953.67 ± 134.38 a | 29 ± 2.76 c | 96.9 ± 0.42 a |

| ground | 42 ± 8.27 ab | 0 | 100.0 | 780.21 ± 84.21 a | 73 ± 8.13 b | 90.6 ± 0.66 c | ||

| EL | 4 | film | 13 ± 2.54 c | 0 | 100.0 | 153.35 ± 27.89 cd | 31 ± 4.75 c | 79.7 ± 1.84 d |

| ground | 56 ± 7.65 a | 0 | 100.0 | 865.77 ± 92.17 a | 97 ± 9.24 a | 88.7 ± 0.24 c | ||

| Treatment | Dose (g/m2) | Yield (kg/666.7 m2) | Yield Increase (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AH | 14 | 575.6 ± 12.29 b | 32.68 ± 1.42 b |

| AL | 7 | 521.59 ± 22.62 c | 20.23 ± 1.81 c |

| EH | 8 | 629.73 ± 12.20 a | 45.16 ± 2.74 a |

| EL | 4 | 516.97 ± 11.44 c | 19.17 ± 2.73 c |

| CK | 433.81 ± 13.44 d | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, G.; Zhang, M.; Shi, Z.; Cao, A.; Wang, Q.; Yan, D.; Fang, W.; Li, Y. Evaluation of Allyl Isothiocyanate and Ethylicin as Potential Substrate and Space Fumigants in Tomato Greenhouses. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2502. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232502

Chen G, Zhang M, Shi Z, Cao A, Wang Q, Yan D, Fang W, Li Y. Evaluation of Allyl Isothiocyanate and Ethylicin as Potential Substrate and Space Fumigants in Tomato Greenhouses. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2502. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232502

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Guangming, Min Zhang, Zhaoai Shi, Aocheng Cao, Qiuxia Wang, Dongdong Yan, Wensheng Fang, and Yuan Li. 2025. "Evaluation of Allyl Isothiocyanate and Ethylicin as Potential Substrate and Space Fumigants in Tomato Greenhouses" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2502. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232502

APA StyleChen, G., Zhang, M., Shi, Z., Cao, A., Wang, Q., Yan, D., Fang, W., & Li, Y. (2025). Evaluation of Allyl Isothiocyanate and Ethylicin as Potential Substrate and Space Fumigants in Tomato Greenhouses. Agriculture, 15(23), 2502. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232502