Abstract

The spatial mismatch between grain production and water resources in China poses significant challenges to food security. This study examines Heilongjiang Province, a major grain-producing region, to explore pathways for enhancing food security through virtual water redistribution. By calculating the virtual water content of typical exported crops and integrating micro- and macroeconomic models, we coupled socio-economic benefits to develop a multi-objective allocation framework centered on “comprehensive benefits”. This framework forms the basis of a grain allocation model grounded in virtual water trade. Our study identifies eight typical grain-deficient regions, including Beijing and Shanghai, and demonstrates that Heilongjiang Province can meet their demands through virtual water transfers. The results reveal significant differences in allocation structures across crops and regions, reflecting heterogeneity in regional demands and resource endowments. This research provides theoretical insights and strategic directions for alleviating food security issues under imbalanced resource distribution, though practical application of the model requires further consideration of regional constraints.

1. Introduction

In recent years, water scarcity has become an increasingly severe issue worldwide [1]. Among 233 global countries and regions, 58 countries are facing food crises [2]. These countries have a total population of approximately 693 million, with shortages exacerbated by water shortages among other factors [2]. Currently, two primary approaches address water scarcity in agricultural regions. The first, based on “physical water” [3], involves reallocating limited resources through diversion projects and transfer initiatives. However, relying solely on physical water redistribution is no longer sufficient. Growing populations and socio-economic development prevent it from meeting the demands of arid regions.

The second approach adopts a “virtual water” perspective. It aims to optimize the industrial structure to facilitate virtual water trade (VWT) [4]. This method enables the optimal allocation of water resources embedded in products [4]. British scholar Tony Allan observed that substantial water is consumed during product manufacturing. This led to the concept of “virtual water”—defined as the water embedded within products [5]. Research on virtual water trade helps optimize agricultural industrial structures [6]. It holds significant practical importance for sustainable water resource allocation [6].

Research on agricultural virtual water trade addresses basic livelihood security. This security is crucial for regions experiencing food scarcity—often attributable to drought or limited land resources. Accurate calculation of virtual water is the foundational step toward its rational allocation. Currently, primary virtual water accounting methods include the “production tree approach” [7] and the “input–output method” [8]. The production tree approach aggregates water consumption throughout the production process up to the final product stage. In contrast, the input–output method is used for comprehensive accounting. It calculates virtual water content across multiple industrial sectors. Given that agricultural production involves multiple crop growth stages, this study adopts the production tree approach. This method calculates crop virtual water content [9]. It incorporates regional climate data and estimates total water requirements throughout germination, seedling, and maturation stages [9]. Through this process, the total virtual water volume of crops can be derived. The per capita virtual water amount by region can also be calculated. Significant disparities in water resources and agricultural conditions exist among Chinese provinces and cities. Northern China possesses more arable land than the South, while the South enjoys higher water availability. This has led to a virtual water flow pattern. It is characterized by “grain transport from North to South” [10].

Economic and social factors are key drivers influencing changes in virtual water allocation to crops. Ref. [11] applied the Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index (LMDI) decomposition method. They also used multiple regression models to analyze key natural and socioeconomic drivers of virtual water flows (VWF) associated with grain trade in China [12]. They constructed a dynamic, interactive framework integrating socio-hydrological and metacoupling systems. Yan computed China’s food water footprints (WFs) and interprovincial virtual water flows [13]. They also assessed unsustainable blue water footprints (UVBW) and water scarcity footprints (WSF) from 2015 to 2019 [13]. Synthesizing these two studies reveals that farmers—as key agents in agricultural production—exhibit strong economic rationality. This occurs against the backdrop of China’s rapid economic growth and people-oriented development policies. Generally, farmers prioritize profit maximization. At the same time, crop trade is significantly influenced by government macro-regulation.

However, a notable research gap remains regarding the interplay between farmer incentives and policy intervention. There is a lack of in-depth studies proposing specific institutional designs and allocation mechanisms. These mechanisms would achieve equitable distribution of limited grain resources within this complex context. Under constrained grain supply, should priority be given to ensuring basic subsistence needs in poorer regions? Alternatively, should it go to fulfilling higher-level market demand in more developed areas [14]? This issue touches not only on allocation efficiency. More profoundly, it concerns social equity and the foundation of the national food security strategy. To address coordination challenges in grain allocation, Cheng et al. developed a multi-objective optimization model [14]. This model is centered on water-saving capacity and the economic benefits of virtual water [14]. It focused on enhancing the economic efficiency of the grain system. Complementarily, Jiang (2024) proposed a multi-scale analytical framework for the Yangtze River Economic Belt [15]. This framework aimed to unravel complex interactions among economic, policy, and social dimensions. Particular emphasis was placed on social equity and regional coordination in grain distribution. While these two studies advance the discussion on grain allocation from distinct methodological angles—economic and social, respectively—neither successfully integrates the other’s prioritized dimension. Each exhibits a clear limitation in perspective. Each also shows a lack of systemic coupling. Within the complex system of grain allocation, achieving synergistic integration of economic and social benefits is essential. This integration has become crucial for deepening research in this field.

This study introduces systematic methodological innovations in the allocation strategy of virtual water trade. First, the virtual water content of typical crops in the study area was accurately measured using the “production tree approach,” providing a reliable data foundation for subsequent allocation analysis. Subsequently, the per capita virtual water occupancy of grain across 31 provinces and municipalities in China was evaluated, thereby identifying core regions and vulnerable nodes experiencing grain shortages. In designing the allocation mechanism, the research does not confine itself to a single perspective. Instead, it integrates classical microeconomic and macroeconomic distribution theories to construct a multi-objective collaborative framework that couples both economic and social goals, leading to the proposed TS allocation scheme. This study systematically couples two critical dimensions—economic and social benefits—in the allocation of virtual water trade. From the economic standpoint, it focuses on the efficiency of resource allocation and cost–benefit outcomes, promoting the flow of water resources toward high-value and high-efficiency uses. Socially, it emphasizes regional equity, food security, and the basic subsistence rights of vulnerable groups, preventing further marginalization of underdeveloped areas attributable to purely market-driven logic. The integration of these two aspects significantly enhances the comprehensiveness and feasibility of the virtual water allocation scheme [16].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

The data used in this study include meteorological data, remote sensing data, and social data, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of data used in this study.

2.2. Study Area

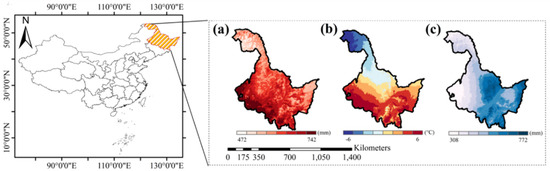

China’s water resources display a spatial pattern characterized by greater abundance in the south and scarcity in the north, whereas northern regions possess more extensive cultivated land resources [17]. As one of the world’s three major black soil regions, Heilongjiang Province has vast territory and relatively abundant water resources (province-wide average annual precipitation 647.7 mm, equivalent to water volume 2934.51 × 108 m3; total water resources 1196.28 × 108 m3, including surface water 1020.53 × 108 m3 and groundwater 362.7 × 108 m3), having become an important grain production base in China. The province’s total grain output surpassed Shandong Province in 2009 and exceeded Henan Province in 2011; currently, its total grain output, commodity grain volume, and grain transfer volume all rank first nationally. The province has 28 large reservoirs and 101 medium-sized reservoirs, with total year-end water storage of 129.66 × 108 m3, providing favorable water resource conditions for agricultural development [18]. For the meteorological characteristics, see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the study area. (a) Annual average evaporation; (b) Annual average temperature; (c) Annual average precipitation.

According to data from the Heilongjiang Statistical Yearbook and Water Resources Bulletin, the province’s cultivated area is 1444.12 × 108 m3, total grain output is 7898.92 × 104 t, and annual average agricultural irrigation water requirement is 281.95 × 108 m3. Among the 13 prefecture-level cities (regions), approximately 68.92% of cultivated land is concentrated in five areas: Qiqihar, Harbin, Jiamusi, Heihe, and Suihua, with Qiqihar City having the largest cultivated area and the Greater Khingan Mountains region having the smallest. Among the four major crops studied (rice, wheat, corn, soybeans), corn has the largest planting area while wheat has the smallest. Specifically, Jiamusi City has the largest rice planting area (no cultivation in the Greater Khingan Mountains region); Heihe City has the largest wheat planting area, Hegang City the smallest; Qiqihar City has the largest corn planting area, Greater Khingan Mountains region the smallest; and Heihe City has the largest soybean planting area, Qitaihe City the smallest [19]. For the grain crop spatial distribution characteristics, see Figure 1.

2.3. Calculation of Virtual Water Content in Crops

Since the concept of virtual water was proposed by British scholar Tony Allan in 1993, it has been widely implemented to measure water consumption in the crop production process [20]. In this study, common rice, wheat, corn, and soybean varieties in Heilongjiang Province were selected to calculate the virtual water content (wrice, wwheat, wcorn, wsoy) of the four crops [21]. The selected typical crop varieties are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sample crop varieties.

The calculation of virtual water content in crops is based on their entire life cycle, which includes the sowing, growth, and maturation stages. It is determined through a comprehensive analysis of water supply and demand balance. On the supply side, this primarily involves precipitation, artificial irrigation, and groundwater recharge. The demand side encompasses soil evaporation, crop transpiration, and water consumed during growth. Furthermore, by accounting for the influence of environmental factors—such as solar radiation, air temperature, humidity, wind speed, among others—on water consumption, the virtual water content per unit output is derived by calculating the ratio of total water consumption during crop growth to the final yield. This approach allows for extrapolation of the crop’s virtual water level. The principle of calculating the virtual moisture content of crops is shown in Figure S1 of the Supplementary Materials.

During the crop growth cycle, its water supply sources mainly include artificial irrigation (including surface water and groundwater utilization) and natural precipitation. However, the proportion of water actually absorbed and used for crop growth is extremely small; most water dissipates through evaporation and transpiration processes under environmental factors (such as temperature, solar radiation). The calculation of virtual water content in crop products essentially constitutes an estimation of total evapotranspiration (ET) throughout their entire growth cycle [16], with the specific calculation process shown as follows:

2.3.1. Calculation of Water Evapotranspiration from Crop Evapotranspiration

The Penman-Monteith formula is the method with a small error for calculating the amount of evapotranspiration from reference crops [22]. The formula is as follows:

In Equation (1), “” indicates the evapotranspiration water for crop growth in mm/d; “” indicates the net radiation on the crop surface in MJ/(m2·d), , “” represents net shortwave radiation, “” represents net longwave radiation, which were obtained through remote sensing data processing; “G” indicates the soil heat flux in MJ/(m2·d), , “” represents the thermal capacity of the soil; “T” indicates the average temperature in °C; “” indicates the wind speed at a height of h meters above the ground in m/s; “” indicates the vapor pressure at saturation in kPa; “” indicates the actual vapor pressure in kPa; “” indicates the difference in vapor pressure in kPa. “” indicates the slope of the vapor pressure curve in kPa/°C, ; and “” indicates the dryness and humidity constant in kPa/°C, .

2.3.2. Calculation of Water Demand per Unit Area of Crops

Crop water demand is generally calculated by summing crop evapotranspiration () during each growing period, considering various growth stages with reference to and the corresponding crop coefficient “” [23]. The equations are as follows:

In Equation (2), “” indicates the cumulative evapotranspiration during the growth and development of crops per unit area, i.e., the amount of water required for crop growth in m3/hm2; “” indicates the crop coefficient, which captures differences in vegetation cover, aerodynamic resistance as well as physiological and physical characteristics between the actual crop and the reference crop.

In Equation (3), “” indicates the water requirement per unit area of crops in m3/hm2; “” indicates the coefficient converting water depth index (mm) into water volume (m3), set at 10; “” is the duration of crop growth in d; “” indicates the duration of different growth stages in d.

2.3.3. Calculating Crop Blue-Green Virtual Water Requirements

The crop water footprint can be specifically categorized into a blue virtual water footprint and a green virtual water footprint, which correspond to when and where the respective water footprints occur. The blue virtual water footprint is the consumption of blue water (surface and groundwater resources) by a product in its supply chain, and depletion is the loss of available surface and groundwater within a watershed. Water loss occurs through evaporation, outflow from the watershed, reaching the sea, or incorporation into the product. Conversely, the green virtual water footprint is the depletion of green water (rainwater that does not become runoff) resources [24].

In Equation (4), “” indicates the green water demand per unit area of crops in m3/hm2; “” indicates the blue water demand per unit area of crops in m3/hm2; “ ” indicates effective rainfall; “” indicates virtual water content per unit of crop in m3/kg; “” indicates crop yield per unit area in m3/hm2; “” indicates the amount of evapotranspiration of green water during the reproductive period of the crop; “” indicates the amount of evapotranspiration of blue water during the reproductive period of the crop.

2.4. Screening of Grain-Deficit Regions

Food security represents a global challenge, particularly in populous countries like China, where uneven regional resource distribution can lead to certain areas relying on external grain supplies. The concept of virtual water is introduced to quantify the water resources required for grain production, thereby indirectly reflecting food self-sufficiency capacity. This study identifies grain-deficient regions by calculating per capita virtual water availability and comparing it with the national average. This approach assists policymakers in allocating resources in a more targeted manner to ensure a stable grain supply. Per capita virtual water availability serves as a key indicator for assessing whether a region requires grain imports. Thus, this study evaluated 31 Chinese provinces and municipalities, identifying those with per capita virtual water availability below the national average as primary grain-importing regions to facilitate optimized resource allocation [25]. The screening process is detailed below.

In Equation (5), “” indicates the difference between the per capita virtual water availability in a given region and the national standard; “−“ indicates that it falls below the national standard, while “+” indicates that it is above the national standard; “” indicates total virtual water for crops in a region; “” indicates population size; and “” indicates the national standard for per capita virtual water availability.

This step quantifies the extent to which each region deviates from the national average. By dividing total virtual water by population size, the actual per capita virtual water availability is obtained and then compared against the national benchmark, enabling the identification of potentially grain-deficient areas. This method not only considers the absolute volume of water resources but also incorporates demographic factors, making the assessment more realistic. For instance, if a region exhibits a negative value, it indicates insufficient per capita virtual water availability, suggesting a potential need to compensate for the deficit through grain imports. This highlights the importance of virtual water indicators in resource optimization. Furthermore, this deviation calculation lays the foundation for subsequent normalization, enhancing data comparability and analytical utility.

In Equation (6), “n” indicates the degree of scarcity of virtual water per capita in each province.

Using the min-max normalization method, the values for each region are converted into a relative scarcity index (n). This process eliminates the influence of measurement units, enabling more intuitive and equitable comparisons across regions. For example, when n approaches 1, it signifies the highest degree of per capita virtual water scarcity in that region, potentially indicating severe food insecurity. Conversely, when n approaches 0, it reflects lower scarcity and stronger food self-sufficiency capacity. This step improves the operational applicability of the research, providing clear prioritization for policy formulation. After normalization, “hotspot” regions can be more easily identified, allowing concentrated resources to address the most urgent food shortages. Simultaneously, this approach accounts for relative differences between regions, avoiding potential biases associated with absolute thresholds.

2.5. Virtual Water Allocation Model

At present, two mainstream approaches to resource allocation prevail; one is based on “microeconomic theory” and “demand-determined supply” allocation ideas [26], while the other is based on “macroeconomic theory” and “supply-driven demand” allocation principles [3]. Based on the interaction between input and output of four major crops based on VWT in various provinces and cities in China, this study selects food-scarce regions and then allocates crops in Heilongjiang Province using both microeconomics and macroeconomics theories.

After grain production in Heilongjiang Province, transportation via rail, road, or waterway incurs some grain loss. After reaching the point of sale, grains are stored in warehouses and sold in batches. This process causes additional transport and management costs. The theoretical output of the virtual water content of grain in Heilongjiang Province, “wt”, is the total amount of virtual water in Heilongjiang Province minus the locally required virtual water amount, as shown below.

In Equation (7), “” indicates the population size; and “” indicates the virtual water requirement per capita.

2.5.1. MIED Scenario Allocation Model

The allocation idea is based on the principle that in the context of a market economy, the allocation of social resources tends to prioritize economic efficiency maximization. Because of the different development rates among Chinese provinces and cities, the consumption level of citizens also varies, leading to different prices of goods across provinces and cities. As food is a necessity for human survival, food producers prefer to sell food to areas with high prices to boost their income [27].

In this study, the maximization of economic efficiency was selected as the objective function (obj) chosen to optimize the allocation of four crop types—rice, wheat, soybean, and maize—is the maximization of economic efficiency. The decision variable is the dummy water quantity (xij), where “i” denotes the grain input region and “j” denotes the grain type.

In Equation (8), “” indicates the economic income from food exports in CNY; “” indicates the cost in CNY. The cost of production remains consistent regardless of the export destination, so production costs are not considered in this study; “sr” indicates the loss rate in %; “x” indicates the virtual water input in m3 for each region; “t” indicates the virtual water unit price in CNY /m3; “” indicates unit transport costs in CNY/m3; “” indicates management and labor costs in CNY/m3.

These three parameters all represent the unit virtual water cost: “” is derived from grain market prices, “” originates from management labor costs in the production areas, and “” is determined by transport distance and freight costs. The data are sourced from the Heilongjiang Statistical Bulletin.

In this study, to optimize the allocation of virtual water in Heilongjiang province, virtual water balance constraints, input and output regional virtual water supply and demand balance constraints, and non-negative constraints are set as constraints (st) [10].

In Equation (9), “” indicates the maximum exportable virtual water in Heilongjiang Province in m3; “” indicates the consumable virtual water in a region in m3; “” indicates the virtual water contained in the self-produced grain in a region in m3.

2.5.2. MAED Scenario Allocation Model

This allocation idea posits that virtual water resources trade forms an integral component based on the natural-social-economic synergistic system. It needs a comprehensive consideration of regional development directions and statuses, along with a series of indicators, including political and social factors. This allocation idea mainly relies on the government’s macro-control capabilities and resource availability for productivity layout. It emphasizes the rational development and utilization of resources to ensure reasonable and rapid development [28].

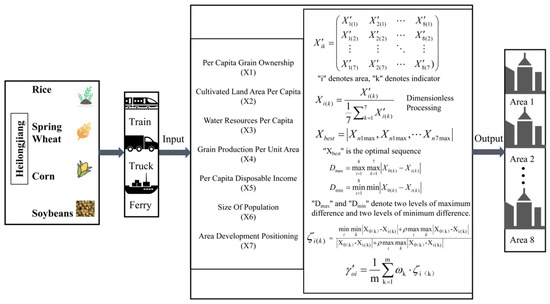

In this study, a series of indicators such as per capita food ownership, per capita water resources, and per capita disposable income are selected to evaluate each food-scarce region, and then the virtual water allocation for food in Heilongjiang Province is carried out according to the evaluation results [29]. The research process is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of MAED scenario analysis.

2.6. TS Scenario Allocation Model (Transition)

The MIED configuration model takes economic benefit maximization as its core objective, while the MAED model prioritizes ensuring resource demands for all regions. Given the limitations of both models, this study integrates their advantages to propose a set of transition schemes (TS scenarios). Under the TS scenario, resource allocation is subject to the synergistic effect of market mechanisms and government regulation; the market drives resources to flow towards benefit maximization, while the government imposes mandatory constraints to ensure the fulfillment of basic resource demands (such as per capita food demand in regions) [30]. Its price formation mechanism follows market rules: oversupply causes prices to fall, while supply–demand equilibrium maintains price stability.

Within the food supply system for eight provinces/municipalities, the TS scenario sets the following core constraints: (1) per capita food demand in each region must be satisfied and (2) regional economic development orientation, dietary habits (affecting food prices and consumption structure), and market price factors must be comprehensively considered. To maximize the overall system benefit (such as social welfare or economic efficiency), the allocation of the four crops requires optimization [31].

The essence of the TS scenario lies in enhancing the comprehensive benefits of the virtual water trade system by coordinating the relationship among food import regions, export regions, and the government [32]. Furthermore, to better reflect the objective of demand guarantee, this study also introduces a unified new objective function into both the MIED and MAED scenarios: minimization of the total shortage of the four foods across all regions. The TS scenario study process is shown in Figure S2 of the Supplementary Materials.

In the TS scenario, the objective function aims to maximize overall benefit while minimizing water deficit [33]:

In Equation (10), “” denotes the total benefit, CNY; “” denotes the integrated benefit conversion factor; “” denotes the total water deficit in m3; and “” denotes the virtual water demand of each region in m3.

3. Results

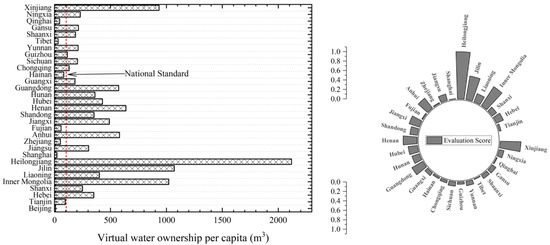

3.1. Grain-Deficient Regions

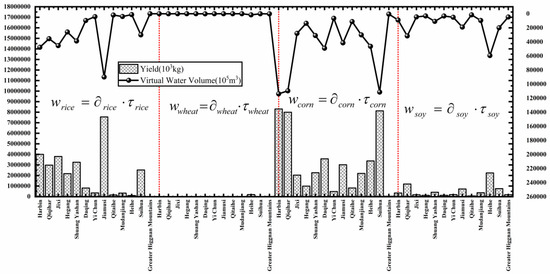

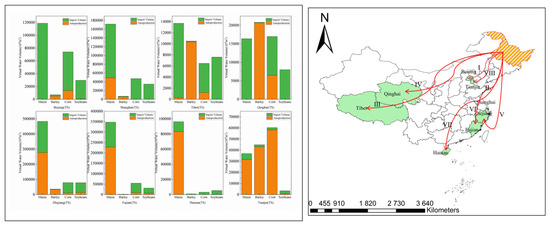

As shown in Figure 3, the virtual water content per unit yield of four major crops (rice, wheat, corn, and soybean) in Heilongjiang Province is presented. The results clearly indicate a significant positive correlation between virtual water content and grain yield. Spatially, Jiamusi exhibits the highest virtual water output for rice, while Qiqihar and Suihua show the highest values for corn. Heihe demonstrates the highest virtual water output for soybeans. In contrast, the virtual water output of wheat remains relatively low across the entire province.

Figure 3.

Grain production and virtual water content in Heilongjiang Province. In the figure, “w” denotes the total amount of virtual water contained in a certain crop in each city; “” denotes the total output of a certain crop in each city.

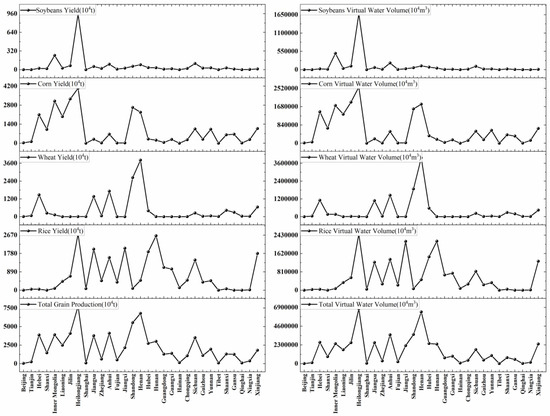

The four types of crop varieties in each province and city in China were selected. The yield and virtual water content of the Crops to be imported in each province and city were statistically calculated, considering factors such as net radiation on the surface of the crops in the local area and the soil heat flux. It was observed that, except for Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan, among the 31 provinces (municipalities) in China, Heilongjiang Province ranked first in the country in terms of grain output, with a total annual grain output of 7763.10 × 104 t, while Beijing City had the lowest grain output of 45.40 × 104 t. The major crop outputs and virtual water contents of provinces (municipalities) are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Grain production and virtual water content for the provinces and municipalities in China.

Based on a per capita virtual water assessment framework, this study further identifies regions at high risk for food insecurity across China (Figure 5). The results show that Heilongjiang Province leads the nation in per capita virtual water availability from grain, indicating a strong local food security position. In contrast, economically developed areas such as Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Zhejiang fall below the national per capita virtual water standard, revealing their high dependency on external grain resources. Consequently, eight regions—Beijing, Shanghai, Tibet, Qinghai, Zhejiang, Fujian, Hainan, and Tianjin—were selected as grain-receiving areas. The study then systematically formulates virtual water allocation plans, detailing the transfer of embedded water resources from Heilongjiang’s four major crops to these designated regions.

Figure 5.

Provincial-level per capita virtual water in China.

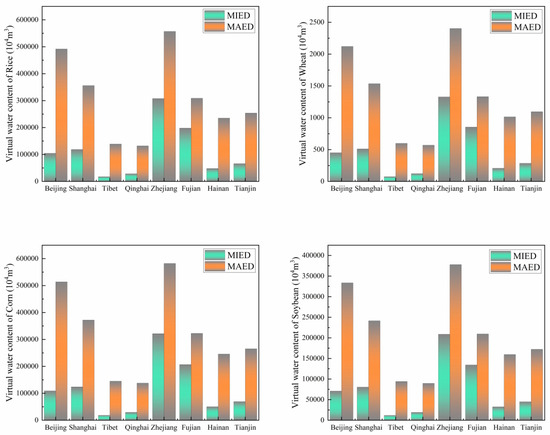

3.2. Crop Allocation Schemes

To address current grain shortages, this study develops two distinct virtual water allocation scenarios. The Minimum Virtual Water Export Scenario (MIED) aims to meet basic food security needs, with a total allocation of 24.231 × 108 m3 cubic meters. Within this scenario, the virtual water shares for rice, wheat, corn, and soybeans are 36.7%, 0.2%, 38.3%, and 24.8%, respectively. In contrast, the Maximum Virtual Water Export Scenario (MAED) operates on a proportional allocation principle, distributing the maximum exportable volume of 67.466 × 108 m3 cubic meters from Heilongjiang Province. This results in a corresponding increase in the virtual water allocated for each crop. Figure 6 clearly illustrates the allocation plans for the four crop types to the eight major grain-deficient regions under these different scenarios, highlighting the variations in resource distribution.

Figure 6.

Four food allocation programs in eight provinces and municipalities.

From Figure 6, in the MIED scenario, all Crops to be imported in each province meet the maximum per capita food demand. Zhejiang Province has the highest inputs for all four crop types, while Tibet has the lowest inputs; in contrast, in the MAED scenario, Zhejiang Province again has the highest inputs for all four crop types, while Qinghai Province has the lowest inputs.

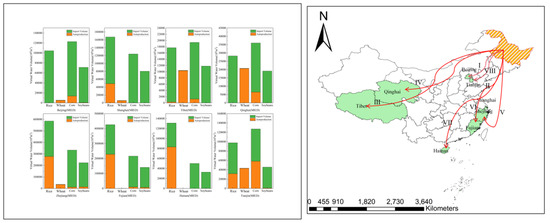

3.2.1. MIED Scenario

In the MIED scenario, self-produced barley accounts for a large proportion of the total wheat available for distribution in Beijing, Shanghai, Tibet, Qinghai, Zhejiang, and Tianjin, while Fujian and Hainan provinces all rely on imports, attributable to the limited wheat cultivation area in Heilongjiang Province. The correspondingly large wheat cultivation in Beijing and Tianjin, regions in southern China where wheat-based diets are common, as well as in Fujian and Hainan, coastal cities in the south, contributes to this difference. Fujian and Hainan, as southern coastal cities, basically do not produce wheat; all Provinces and regions mainly dependent on imports rely on imports for basically all of their soybeans; except for Tianjin, the other provinces and cities rely entirely on imported corn; for the total rice available for distribution in the Provinces and regions mainly dependent on imports, except for Zhejiang, Fujian and Hainan, the remaining five provinces and cities primarily depend on imports, which is attributable to the abundant rice production in southern China, where self-production is sufficient. Shanghai, also located in the south, produces less rice attributable to urbanization and limited arable land. As a result, it relies more on imports compared to its southern counterparts. The configuration result is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Configuration result of the MIED scheme.

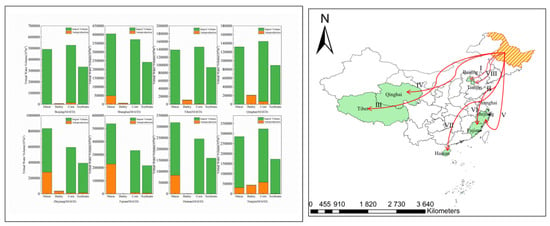

3.2.2. MAED Scenario

In the MAED scenario, Beijing, Shanghai, Tibet, Qinghai, Zhejiang, and Tianjin allocate a significant portion of domestically grown wheat, while Fujian and Hainan provinces rely entirely on imports; all Provinces and regions mainly dependent on imports rely on imports for almost all of their corn and soybeans; Similarly, except for Zhejiang and Fujian, the other six provinces and cities primarily rely on imports for rice. The study shows that under the “supply to demand” model of the MAED scenario, rice production in Heilongjiang province far exceeds the combined rice demand of the Provinces and regions mainly dependent on imports, while Zhejiang and Fujian, with higher arable land and higher rice production, allocate a smaller proportion of rice from Heilongjiang province, attributable to their own substantial production capacity. As a result, Zhejiang and Fujian rely more on self-produced rice than the other six provinces and municipalities. The configuration result is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Configuration result of the MAED scheme.

3.3. TS Scenario

The curve of variation in the price of four types of foodstuffs with the amount of disposable virtual water per capita is shown in Figure S3 of the Supplementary Materials.

The graph illustrates an exponential decrease in the prices of the four types of food with increasing per capita disposable virtual water volume.

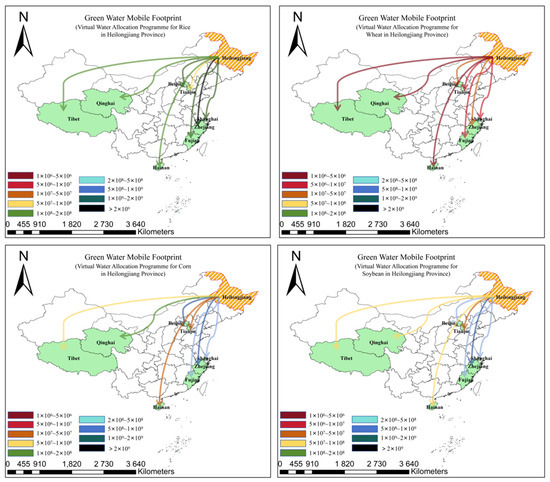

Under the TS scenario, Heilongjiang Province can export a total of 104.38 × 108 m3, of virtual water, which can satisfy the basic food demand per capita of eight regions with severe food scarcity. Specifically, the virtual water content of rice is 61.53 × 108 m3, for wheat is 1.07 × 108 m3, for corn is 24.16 × 108 m3, and for soybean is 17.62 × 108 m3. Among these regions, Beijing and Shanghai rely entirely on food imports, while Tianjin has a lesser demand for food imports. Except for Beijing and Shanghai, the northern provinces of Tibet, Qinghai, and Tianjin primarily rely on the self-production of wheat, while the southern regions of Zhejiang, Fujian, and Hainan receive the most rice allocation. The configuration result is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Configuration result of the TS scheme.

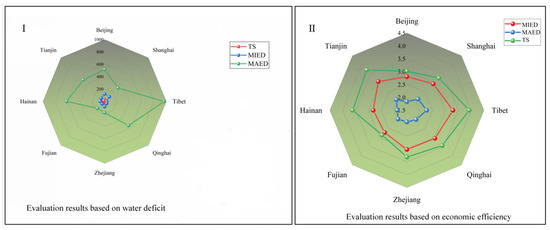

3.4. Optimization

The primary objective of this study is to assess three virtual water configuration scenarios: the MIED, the MAED, and the TS scenarios, from which a set of optimal scenarios is selected. The study employs economic efficiency, based on microeconomic theory, and water shortages, based on macroeconomic theory, as the evaluation systems for the three scenarios. For water scarcity, this study measures the difference between the per capita allocable virtual water content of the four food categories under the three scenarios and the per capita virtual water standard for food (m3). A negative evaluation value indicates better performance, suggesting smaller deviation from the standard. For economic benefits, this study evaluates the average unit price (CNY/m3) of virtual water for the four types of food under the three scenarios. A higher evaluation value is preferred, indicating greater economic benefits. The results of the configuration plan evaluation are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Configuration program evaluation results. (I) Evaluation results based on water scarcity. (II) Evaluation results based on economic efficiency MIED contextual configuration results.

According to the evaluation results, the water shortage and economic benefits are both optimal in the allocation scheme of the TS scenario. The TS scenario is chosen as the optimal grain allocation scheme in Heilongjiang Province. The distribution results of the four types of grain in Provinces and regions mainly dependent on imports under this scenario are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Virtual water footprint under the optimal allocation scheme.

4. Discussion and Policy Recommendations

4.1. Interpretation of Key Findings and Virtual Water Flow Patterns

This study quantifies the virtual water (VW) flows associated with grain redistribution from Heilongjiang Province to eight food-deficit regions. The socio-hydrological analysis identifies Zhejiang and Fujian as the primary VW inflow regions. This aligns with their high population density and economic development levels. The alignment results in intensified local water scarcity and grain demand [34]. The optimal allocation model is based on a “comprehensive benefit” objective. It successfully distributes four major crops. he distribution meets the per capita grain requirements of all deficit regions [35]. The distribution outcomes reveal significant disparities in VW allocation volumes [36]. Zhejiang received the highest allocation (33.96 × 108 m3), reflecting its substantial demand, whereas Tianjin received the lowest (1.20 × 108 m3) [10]. This pattern is rationally determined by the model’s integration of factors such as population, regional grain deficits, and economic efficiency [37]. Beyond the primary Heilongjiang-centric system, the analysis of national grain production data suggests that Heilongjiang, Henan, and Shandong form a robust foundation for a multi-province VW export system. This conclusion is supported by their dominant and stable grain output trends from 2011 to 2023.

4.2. Policy Recommendations Derived from Model Results

The model’s outputs provide a quantitative basis for targeted policy interventions:

Differentiated Subsidies for Export Hubs: The government should prioritize Heilongjiang, Henan, and Shandong as core VW export hubs. Economic subsidies and eco-compensation mechanisms should be calibrated based on their quantified export volumes (as exemplified by Heilongjiang’s central role in this study). This will incentivize sustained grain production and VW outflows.

Infrastructure Investment for Key Corridors: Given the large VW transfers to Zhejiang, Fujian, and other southeastern regions, policy should focus on minimizing losses in the physical grain supply chain. Investments in “green channels” for north-to-south grain transport, intelligent logistics, and modern storage infrastructure are crucial. These investments will preserve the virtual water embedded in allocated grains, directly supporting the model’s efficiency objective.

Promotion of Inter-regional Cooperation: The government should facilitate partnerships between grain-importing regions (e.g., technologically advanced zones like Beijing and Shanghai) and exporting provinces. Such cooperation could focus on R&D for water-efficient agricultural technologies and modernized supply chain management. This will enhance the resilience of the VW trade network identified in this study.

4.3. Research Limitations and Future Directions

While this study provides a viable framework for inter-regional grain allocation, several limitations must be acknowledged, which also chart the course for future research.

Model Simplifications and Assumptions: The current model is a static equilibrium analysis. It does not account for climatic variability, future market price fluctuations, or technological progress. The assumption of fixed water footprints and transportation costs introduces uncertainty over the long term [38].

Data Gaps and Resolution: The analysis relies on provincial-level data. Higher spatial resolution (e.g., prefectural/county level) could yield more precise allocation schemes. Furthermore, the virtual water calculations are based on standard crop coefficients and evapotranspiration data; localized, real-time measurements could improve accuracy [39].

Future Modeling Enhancements: To address these limitations, future work should focus on the following:

Developing dynamic stochastic programming or Agent-Based Models (ABM) to simulate VWT under climate scenarios (e.g., RCPs) and policy shocks (e.g., carbon tax).

Integrating sensitivity and uncertainty analysis for key input variables (e.g., crop evapotranspiration (ET), crop coefficients (Kc), commodity prices, and transport costs) to assess the robustness of the allocation results.

Expanding the objective function to include multi-dimensional sustainability indicators, such as the carbon footprint or gray water footprint, thereby evaluating the VW trade within a water–energy–food–carbon nexus framework.

Methodological Reproducibility: For full transparency and reproducibility, a subsequent technical note will detail the optimization software, solver specifications, algorithm parameters, and complete parameterization process used in this study.

5. Conclusions

This study developed an integrated economic model to optimize the inter-regional allocation of four major crops from Heilongjiang Province to eight grain-deficient regions in China. By introducing a “comprehensive benefit” objective and a transitional scenario balancing efficiency and equity, the model generated a feasible distribution plan. The results indicate that this strategy can meet the per capita grain requirements of the deficit regions while improving overall economic and resource efficiency. Zhejiang and Fujian were identified as the largest virtual water recipients, consistent with their socio-economic profiles.

The findings offer a theoretical foundation and a practical starting point for policymakers to enhance national food and water security through virtual water trade. However, the conclusions are contingent upon the model’s specific assumptions and parameters. The implementation of the proposed allocation strategy requires complementary policies—including targeted subsidies, infrastructure investment, and inter-regional cooperation—as well as a critical consideration of the model’s limitations, particularly its static nature. Future research should focus on developing dynamic, multi-objective models and conducting rigorous sensitivity analyses to build a more resilient and adaptive national virtual water management system.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15232477/s1, Figure S1: Principle of calculating virtual water content of crops; Figure S2: TS scenario study process; Figure S3: Food price curve relative to per capita disposable virtual water volume; Figure S4: Three-province cooperative virtual water trading system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W., Z.Z. and T.W.; data curation, Z.W.; formal analysis, Z.W. and R.H.; investigation, M.L. and Q.L.; methodology, Z.W.; resources, Z.W. and Z.Z.; software, Z.W.; validation, R.H., M.L. and P.X.; writing—original draft, Z.W. and Z.Z.; writing—review and editing, T.W., R.H., M.L. and Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 52422902 and 52409012); The Postdoctoral Fellowship Program and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (BX20240442); China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2025MD774050); Heilongjiang Provincial Postdoctoral Research Funding Program (LBH-Z24007); and the New Era Heilongjiang Outstanding Master’s/Doctoral Dissertation Grant Program.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Yang, L.; Yin, X.; Gao, Z.; Yang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, Y.; Gao, T.; Hai, N.T. Prioritizing crops for implementing a virtual water strategy that accounts for effects at an economic system scale in water-scarce regions. J. Hydrol. 2025, 661, 133756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, B.; Li, N.; Wang, P.; Chen, C.; Chen, W.-Q.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Lu, Y. Resource nexus for sustainable development: Status quo and prospect. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2021, 66, 3426–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilf, E. To go with the free information flow: Problems and contradictions in macro-level neoliberal theories and their translation to micro-level business innovation strategies. Soc. Anthropol. 2020, 28, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, T.; Wang, L.; Gao, X.; Han, X.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, L.; Wu, P. Simulation of the virtual water flow pattern associated with interprovincial grain trade and its impact on water resources stress in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oki, T.; Kanae, S. Virtual water trade and world water resources. Water Sci. Technol. 2004, 49, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, N.T.; Hejazi, M.I.; Kim, S.H.; Davies, E.G.R.; Edmonds, J.A.; Miralles-Wilhelm, F. Future changes in the trading of virtual water. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visentin, J.C.; Martins Guilhoto, J.J. The Role of Interregional Trade in Virtual Water on the Blue Water Footprint and the Water Exploitation Index in Brazil. Rev. Reg. Stud. 2019, 49, 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Han, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Liu, J. Virtual Water Flows Embodied in International and Interprovincial Trade of Yellow River Basin: A Multiregional Input-Output Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, K.; Yang, S.; Yu, Y. An input-output approach to evaluate the water footprint and virtual water trade of Beijing, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 42, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yuan, J.; Yu, Q.; Sun, Z. A Study of Initial Water Rights Allocation Coupled with Physical and Virtual Water Resources. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhuo, L.; Rulli, M.C.; Wu, P. Limited water scarcity mitigation by expanded interbasin physical and virtual water diversions with uneven economic value added in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 847, 157625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Tong, J.; Gu, J.; Sun, S.; Sun, J.; Zhao, J.; Tang, Y.; Wu, P.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z. Socio-hydrology pathway of grain virtual water flow in China. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 292, 108658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Li, M.; Zhuo, L.; Han, Y.; Ji, X.; Wu, P. Diversities and sustainability of dietary water footprint and virtual water flows in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 444, 141204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Jiang, X.; Wang, M.; Zhu, T.; Wang, L.; Miao, L.; Chen, X.; Qiu, J.; Shu, J.; Cheng, J. Optimal allocation of agricultural water and land resources integrated with virtual water trade: A perspective on spatial virtual water coordination. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 347, 119189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Yu, X.; Dai, M.; Shen, X.; Zhong, G.; Yuan, C. How do Multi-Scale Virtual Water Flows of Large River Economic Belts Impact Regional Water Distribution: Based on a Nested Input-Output Model. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 38, 1027–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.X.; Yin, Y.L.; Sun, S.K.; Wang, Y.B.; Yu, X.; Yan, K. Review on research status of virtual water: The perspective of accounting methods, impact assessment and limitations. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 243, 106407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Fang, X.; Yun, Y. Regional differences of vulnerability of food security in China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2009, 19, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Liu, C.; Li, T.; Meng, F.; Fu, Q.; Ji, Y.; Hou, R. Evaluation of the water resource carrying capacity in Heilongjiang, eastern China, based on the improved TOPSIS model. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 110208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Wei, S.; Ren, Y.; Fu, Q. Optimal allocation of agricultural water resources under the background of China’s agricultural water price reform-a case study of Heilongjiang province. Appl. Math. Model. 2021, 97, 636–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Sun, S.; Zhang, X. Analysis of virtual water flows related to crop transfer and its effects on local water resources in Hetao irrigation district, China, from 1960 to 2008. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2013, 11, 682–686. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Han, S.; Li, H.; Ren, D.; Sheng, Z.; Yang, Y. Virtual Water Flows in Internal and External Agricultural Product Trade in Central Asia. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2022, 58, 1162–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Kim, K.; Kim, H.S.B. Multi-Regional Input-Output Analysis of Inter-Regional Virtual Water Flow in Korea. Korean J. Agric. Econ. 2013, 54, 193–213. [Google Scholar]

- Brindha, K. International virtual water flows from agricultural and livestock products of India. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Li, J.; Singh, V.P. Optimal Allocation of Agricultural Water Resources Based on Virtual Water Subdivision in Shiyang River Basin. Water Resour. Manag. 2014, 28, 2243–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Huang, K.; Yu, Y.; Hu, J. Inter-Regional Agricultural Virtual Water Flow in China Based on Volumetric and Impact-Oriented Multi-Regional Input-Output (MRIO) Approach. Water 2020, 12, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Velasco, M. Market structure and pricing strategies: A mathematical and graphical analysis of price discrimination, accompanied by a Microsoft Excel-based tool. J. Educ. Bus. 2021, 96, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, T. Optimal water resource allocation considering virtual water trade in the Yellow River Basin. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, C.; Peng, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, C. The virtual Water flow of crops between intraregional and interregional in mainland China. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 208, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayia, A.; Collins, A.M.; Gilmont, M. The role of virtual-water decoupling in achieving food-water security: Lessons from Egypt, 1962–2013. Water Int. 2022, 47, 1118–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Sun, S.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, P. Evaluating grain virtual water flow in China: Patterns and drivers from a socio-hydrology perspective. J. Hydrol. 2022, 606, 127412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasakura, K. A macroeconomic theory of price determination. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2021, 59, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Sun, S.; Cao, X. Virtual Water Flows Related to Grain Crop Trade and Their Influencing Factors in Hetao Irrigation District, China. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2015, 17, 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Han, A.; Liu, A.; Guo, Z.; Liang, Y.; Chai, L. Measuring Gains and Losses in Virtual Water Trade from Environmental and Economic Perspectives. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2023, 85, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rashed, M.; Sefelnasr, A.; Sherif, M.; Murad, A.; Alshamsi, D.; Aliewi, A.; Ebraheem, A.A. Novel concept for water scarcity quantification considering nonconventional and virtual water resources in arid countries: Application in Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 882, 163473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Du, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhu, K.; Lu, Y.; Liu, X. Trade heterogeneity and virtual water exports of China. Econ. Syst. Res. 2023, 35, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Zhuo, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, Z.; Wu, P. Tracking indirect water footprints, virtual water flows, and burden shifts related to inputs and supply chains for croplands: A case for maize in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 342, 118347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, J.; Yu, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Shi, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y. Multi-scale near-long-range flow measurement and analysis of virtual water in China based on multi-regional input-output model and machine learning. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 175, 854–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekmatnia, M.; Isanezhad, A.; Ardakani, A.F.; Ghojghar, M.A.; Ghaleno, N.D. An attempt to develop a policy framework for the global sustainability of freshwater resources in the virtual water trade. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 39, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Guo, M. Exploring the drivers of quantity- and quality-related water scarcity attributable to trade for each province in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 333, 117423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).