Digital Image Quantification of Rice Sheath Blight: Optimized Segmentation and Automatic Classification

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The proposed method quantifies both the lesion area and the maximum height and, once sample images are provided, can rapidly and automatically evaluate the severity of the disease without manual intervention. This enables large-scale phenotyping with significantly reduced labor requirements.

- Methodologically, the framework consists of two major components:

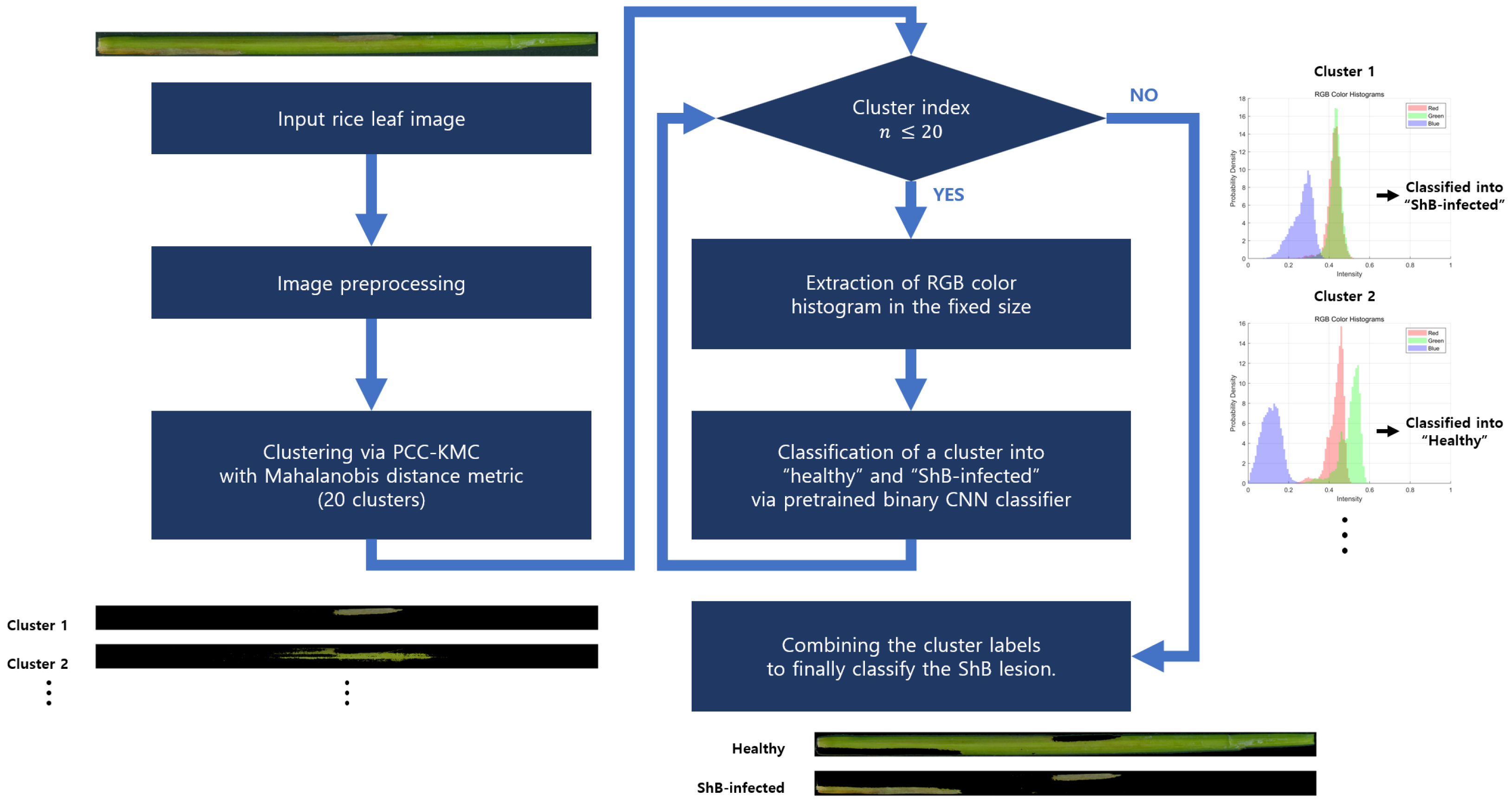

- Segmentation of lesion and healthy regions using the proposed Pixel Color- and Coordinate-based K-Means Clustering algorithm (PCC-KMC) utilizing the Mahalanobis metric;

- Automated classification using a pre-trained binary Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) classifier that determines whether each segmented region corresponds to an ShB lesion.

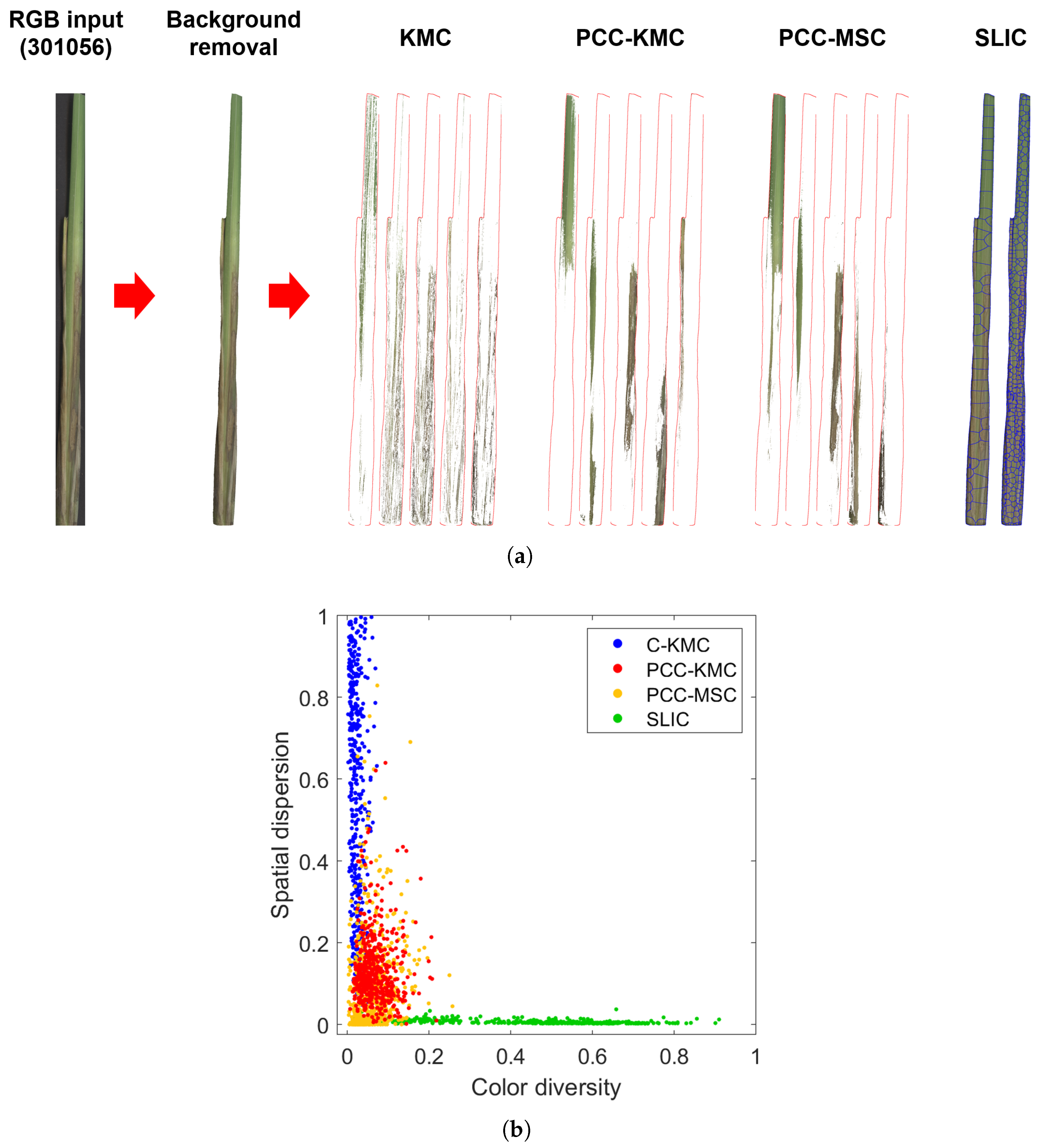

- In the segmentation step, traditional unsupervised color-based k-means clustering fails to isolate local lesions because it groups spatially scattered pixels with similar color values. By incorporating the Mahalanobis distance into the clustering, the proposed PCC-KMC method enforces spatial locality and color similarity simultaneously, allowing accurate extraction of local ShB lesions.

- Instead of relying on manual visual judgment to determine whether each segmented region is diseased, we employ a CNN-based classifier for automatic classification.

- Conventional CNNs require fixed-size rectangular image inputs and, therefore, cannot directly handle the irregular shapes and variable sizes of segmented lesion patches. To overcome this, we extract RGB histograms from each segmented region and use them as compact CNN inputs, leveraging the fact that the color distribution differs between the lesion and the healthy tissue.

- Because RGB histograms can be normalized to a fixed dimension regardless of the shape or size of the region, they are ideally suited as CNN input for robust classification.

2. Related Works

2.1. Traditional Phenotyping of Rice Sheath Blight

2.2. Genetic, Genomic, and QTL Studies and ShB Quantification

2.3. Digital Imaging and RGB-Based Disease Quantification

2.4. Hyperspectral and Multispectral Disease Detection Approaches

2.5. Summary of Gaps in the Literature

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparation of ShB-Infected Plant Samples

3.2. Acquisition of RGB Digital Images of ShB-Infected Rice Stems

3.3. Image Analyses of ShB-Infected Rice Stems

3.3.1. Pre-Processing of Acquired RGB Images

3.3.2. Segmentation of RGB Images Through PCC-KMC

3.3.3. Testing the Performance of PCC-KMC to Other Existing Methods

3.3.4. Convolutional Neural Network-Based Automatic ShB Symptom Classification

3.3.5. Post-Processing to Quantify Disease Severity

3.4. Evaluation of the Accuracy of PCC-KMC and PCC-KMC-CNN

4. Results

4.1. Performance of PCC-KMC

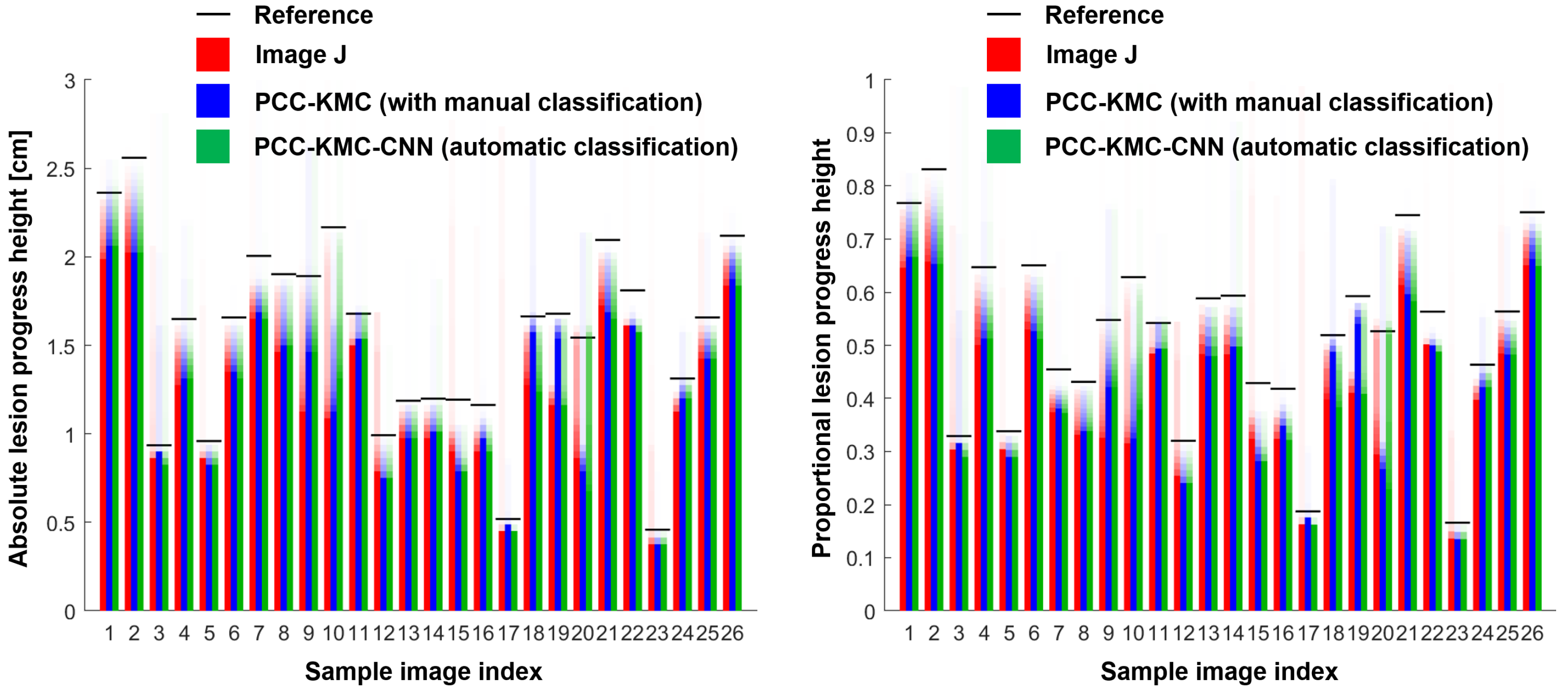

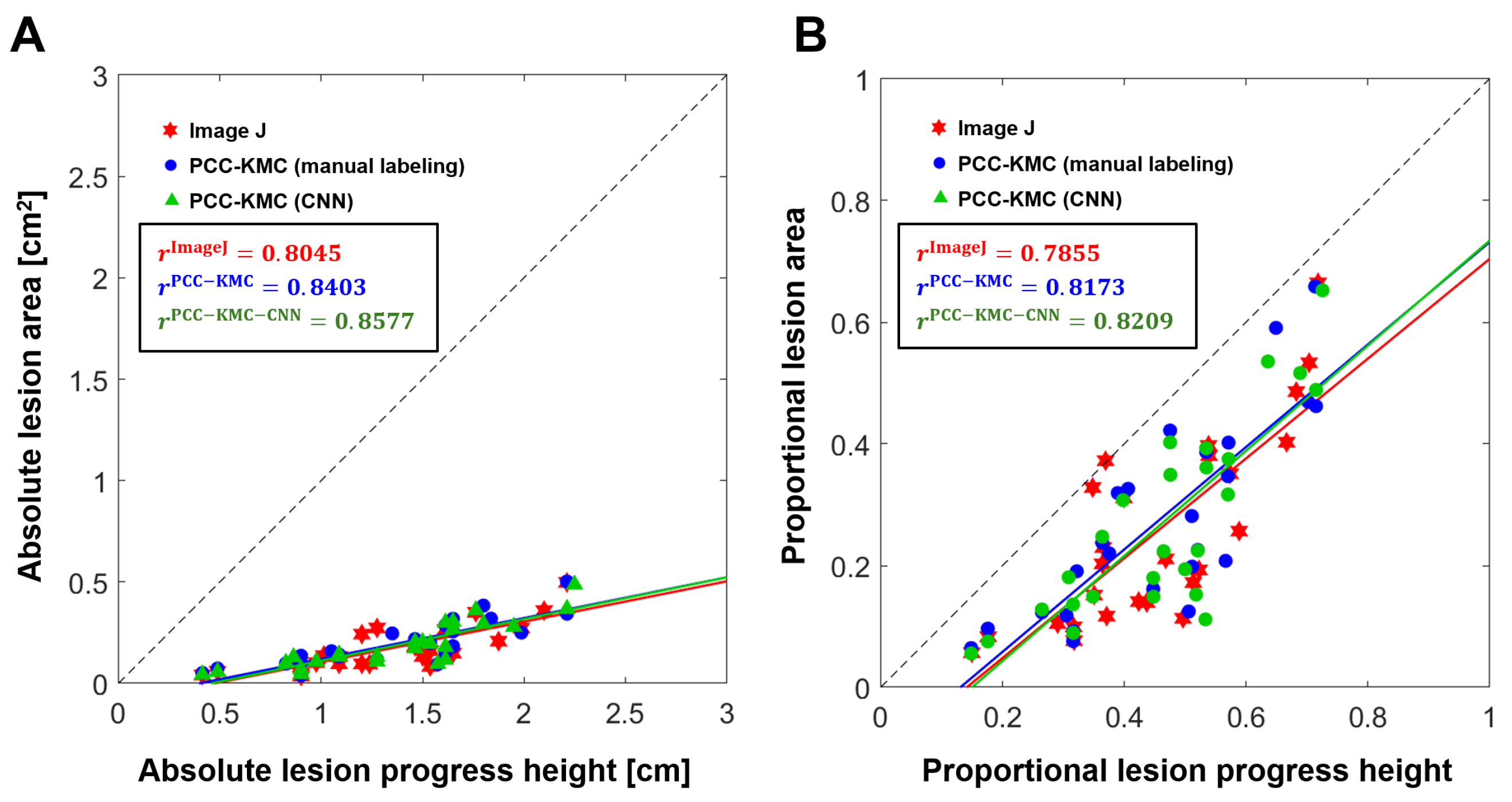

4.2. Accuracy of ShB Severity Measurements Obtained from Visual Manual Annotation, ImageJ and PCC-KMC and PCC-KMC-CNN

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Inconsistent illumination across RGB images, including shadows and brightness variations across different days, may reduce the robustness of the segmentation without appropriate normalization or pre-processing.

- The co-occurrence of multiple stresses in field environments, such as other diseases, nutrient deficiencies, and pest-induced damage, makes it challenging to isolate ShB lesions and requires further algorithmic adaptation for practical field deployment.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Groth, D.E. Effects of cultivar resistance and single fungicide application on rice sheath blight, yield, and quality. Crop Prot. 2008, 27, 1125–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogoshi, A. Ecology and pathogenicity of anastomosis and intraspecific groups of Rhizoctonia solani Kuhn. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1987, 25, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.Z.; Zhang, W.; Ou, Z.Q.; Li, C.W.; Zhou, G.J.; Wang, Z.K.; Yin, L.L. Analyses of the temporal development and yield losses due to sheath blight of rice (Rhizoctonia solani AG1-IA). Agric. Sci. China 2007, 6, 1074–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banniza, S.; Holderness, M. Rice sheath blight—pathogen biology and diversity. In Major Fungal Diseases of Rice: Recent Advances; Krause, G., Strange, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Slaton, N.A.; Cartwright, R.D.; Meng, J.; Gbur, E.E.; Norman, R.J. Sheath blight severity and rice yield as affected by bitrogen fertilizer rate, application method, and fungicide. Agron. J. 2003, 95, 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiba, T.; Kobayashi, T. Rice diseases incited by Rhizoctonia species. In Rhizoctonia Species: Taxonomy, Molecular Biology, Ecology, Pathology and Disease Control; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996; pp. 331–340. [Google Scholar]

- Asins, M.J.; Bernet, G.P.; Villalta, I.; Carbonell, E.A. QTL analysis in plant breeding. In Proceedings of the Molecular Techniques in Crop Improvement; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gururani, M.A.; Venkatesh, J.; Upadhyaya, C.P.; Nookaraju, A.; Pandey, S.K.; Park, S.W. Plant disease resistance genes: Current status and future directions. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 78, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Correa-Victoria, F.; McClung, A.; Zhu, L.; Liu, G.; Wamishe, Y.; Xie, J.; Marchetti, M.A.; Pinson, S.R.M.; Rutger, J.N.; et al. Rapid determination of rice cultivar responses to the sheath blight pathogen Rhizoctonia solani Using a micro-chamber screening method. Plant Dis. 2007, 91, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinson, S.R.M.; Capdevielle, F.M.; Oard, J.H. Confirming QTLs and Finding Additional Loci Conditioning Sheath Blight Resistance in Rice Using Recombinant Inbred Lines. Crop Sci. 2005, 45, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Jia, Y.; Correa-Victoria, F.J.; Prado, G.; Yeater, K.; McClung, A.; Correll, J.C. Mapping quantitative trait loci responsible for resistance to sheath blight in rice. Phytopathology 2009, 99, 1078–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.X.; Ji, Z.J.; Ma, L.Y.; Li, S.M.; Yang, C.D. Advances in mapping loci conferring resistance to rice sheath blight and mining Rhizoctonia solani resistant resources. Rice Sci. 2011, 18, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Liu, G.; Park, D.S.; Yang, Y. Inoculation and scoring methods for rice sheath blight disease. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 956, 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.K.; Jena, K.K.; Bhuiyan, M.A.R.; Wickneswari, R. Association between QTLs and morphological traits toward sheath blight resistance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Breed. Sci. 2016, 66, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, C.H.; Parker, P.E.; Cook, A.Z.; Gottwald, T.R. Visual rating and the use of image analysis for assessing different symptoms of citrus canker on grapefruit leaves. Plant Dis. 2008, 92, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Rohilla, R.; Singh, U.S.; Savary, S.; Willocquet, L.; Duveiller, E. An improved inoculation technique for sheath blight of rice caused by Rhizoctonia solani. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2002, 24, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, C.H.; Barbedo, J.G.A.; Ponte, E.M.D.; Bohnenkamp, D.; Mahlein, A.K. From visual estimates to fully automated sensor-based measurements of plant disease severity: Status and challenges for improving accuracy. Phytopathol. Res. 2020, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, F.; Yan, W.; Gibbons, J.; Emerson, M.; Clark, S.D. Rice blast and sheath blight evaluation results for newly introduced rice germplasm. In B.R. Wells Rice Research Studies 2002; Series No. 504; Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Arkansas: Fayetteville, AR, USA, 2002; pp. 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Poland, J.A.; Nelson, R.J. In the eye of the beholder: The effect of rater variability and different rating scales on QTL mapping. Phytopathology 2011, 101, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Tze, O.S.; Nadarajah, K.; Jena, K.; Rahman Bhuiyan, M.A.; Ratnam, W. Identification and validation of sheath blight resistance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars against Rhizoctonia solani. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2014, 36, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, X.Y.; Zhu, L.H. Resistance of some rice varieties to sheath blight (ShB). Int. Rice Res. Newsl. 1990, 15, 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, M.; Bollich, C. Quantification of the relationship between sheath blight severity and yield loss in rice. Plant Dis. 1991, 75, 773–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khirade, S.D.; Patil, A. Plant disease detection using image processing. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Computing Communication Control and Automation, Pune, India, 26–27 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arnal Barbedo, J.G. Digital image processing techniques for detecting, quantifying and classifying plant diseases. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlein, A.K. Plant disease detection by imaging sensors–parallels and specific demands for precision agriculture and plant phenotyping. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, C.; Belin, E.; Bove, E.; Rousseau, D.; Fabre, F.; Berruyer, R.; Guillaumès, J.; Manceau, C.; Jacques, M.A.; Boureau, T. High throughput quantitative phenotyping of plant resistance using chlorophyll fluorescence image analysis. Plant Methods 2013, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toda, Y.; Okura, F. How convolutional neural networks diagnose plant disease. Plant Phenomics 2019, 2019, 9237136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Du, K.; Zheng, F.; Zhang, L.; Gong, Z.; Sun, Z. A recognition method for cucumber diseases using leaf symptom images based on deep convolutional neural network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 154, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamari, L. Assess: Image Analysis Software for Plant Disease Quantification; APS Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Systat Software, Inc. SigmaPlot Version 12.5; Systat Software, Inc.: San Jose, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothen, M.E.; Pai, M.L. Detection of rice leaf diseases using image processing. In Proceedings of the 2020 Fourth International Conference on Computing Methodologies and Communication, Erode, India, 11–13 March 2020; pp. 424–430. [Google Scholar]

- Phadikar, S.; Sil, J. Rice disease identification using pattern recognition techniques. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology, Khulna, Bangladesh, 25–27 December 2008; pp. 420–423. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Q.; Guan, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, J.; Hu, Y.; Yang, B. Application of support vector machine for detecting rice diseases using shape and color texture features. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Engineering Computation, Hong Kong, China, 2–3 May 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Nutter, F.W.; Esker, P.D.; Netto, R.A.C. Disease assessment concepts and the advancements made in improving the accuracy and precision of plant disease data. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2006, 115, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Sengar, N.; Dutta, M.K.; Travieso, C.M.; Alonso, B.J. Automated segmentation of powdery mildew disease from cherry leaves using image processing. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference and Workshop on Bioinspired Intelligence, Funchal, Portugal, 10–12 July 2017; pp. 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kuruvilla, J.; Sukumaran, D.; Sankar, A.; Joy, S.P. A review on image processing and image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Data Mining and Advanced Computing, Ernakulam, India, 16–18 March 2016; pp. 198–203. [Google Scholar]

- Macqueen, J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Berkeley, CA, USA, 1 January 1967; Volume 1, pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Sethy, P.K.; Negi, B.; Bhoi, N. Detection of healthy and defected diseased leaf of rice crop using K-means clustering technique. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2017, 157, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hiary, H.; Bani-Ahmad, S.; Reyalat, M.; Braik, M.; ALRahamneh, Z. Fast and accurate detection and classification of plant diseases. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2011, 17, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashish, D.A.; Braik, M.; Bani-Ahmad, S. Detection and classification of leaf diseases using k-means-based segmentation and neural-networks-based classification. Inf. Technol. J. 2011, 10, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.S.; Sayler, R.J.; Hong, Y.G.; Nam, M.H.; Yang, Y. A method for inoculation and evaluation of rice sheath blight disease. Plant Dis. 2008, 92, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lore, J.S.; Hunjan, M.S.; Singh, P.; Willocquet, L.; Sri, S.; Savary, S. Phenotyping of partial physiological resistance to rice sheath blight. J. Phytopathol. 2013, 161, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, J.E.; Martínez, S.; Bonnecarrère, V.; Pérez de Vida, F.; Blanco, P.; Malosetti, M.; Jannink, J.L.; Gutiérrez, L. Comparison of phenotyping methods for resistance to stem rot and aggregated sheath spot in rice. Crop Sci. 2016, 56, 1619–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willocquet, L.; Lore, J.S.; Srinivasachary, S.; Savary, S. Quantification of the components of resistance to rice sheath blight using a detached tiller test under controlled conditions. Plant Dis. 2011, 95, 1507–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timsina, A.; Thera, U.K.; Ramasamy, N. Phenotypic screening of F3 rice (Oryza sativa L.) population resistance associated with sheath blight disease. Int. J. Bio-Resour. Stress Manag. 2022, 13, 527–534. [Google Scholar]

- International Rice Research Institute. Standard Evaluation System; International Rice Research Institute: Manila, Philippines, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, A.; Pandian, R.; Rajashekara, H.; Singh, V.; Kumar, G.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, A.; Krishnan, S.G.; Singh, A.; Rathour, R.; et al. Phenotyping of improved rice lines and landraces for blast and sheath blight resistance. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2014, 74, 499–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turaidar, V.; Krupa, K.; Reddy, M.; Deepak, C.; Harini, K.; Subhash, B. Phenotyping of rice landraces for sheath blight resistance. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2017, 6, 2209–2212. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.P.; Xing, Y.Z.; Gu, S.L.; Chen, Z.X.; Pan, X.B.; Chen, X.L. Effect of morphological traits on sheath blight resistance in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2003, 45, 825–831. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Pinson, S.; Marchetti, M.; Stansel, J.; Park, W. Characterization of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) in cultivated rice contributing to field resistance to sheath blight (Rhizoctonia solani). Theor. Appl. Genet. 1995, 91, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Pan, X.; Chen, Z.; Xu, J.; Lu, J.; Zhai, W.; Zhu, L. Mapping quantitative trait loci controlling sheath blight resistance in two rice cultivars (Oryza sativa L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000, 101, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channamallikarjuna, V.; Sonah, H.; Prasad, M.; Rao, G.; Chand, S.; Upreti, H.; Singh, N.; Sharma, T. Identification of major quantitative trait loci qSBR11-1 for sheath blight resistance in rice. Mol. Breed. 2010, 25, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, S.; Yin, Y.; Pan, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, S.; Zhu, L.; Pan, X. Fine mapping of qSB-11 LE, the QTL that confers partial resistance to rice sheath blight. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2013, 126, 1257–1272. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Pinson, S.; Fjellstrom, R.; Tabien, R. Phenotypic gain from introgression of two QTL, qSB9-2 and qSB12-1, for rice sheath blight resistance. Mol. Breed. 2012, 30, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizenga, G.; Prasad, B.; Jackson, A.; Jia, M. Identification of rice sheath blight and blast quantitative trait loci in two different O. sativa/O. nivara advanced backcross populations. Mol. Breed. 2013, 31, 889–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goad, D.M.; Jia, Y.; Gibbons, A.; Liu, Y.; Gealy, D.; Caicedo, A.L.; Olsen, K.M. Identification of novel QTL conferring sheath blight resistance in two weedy rice mapping populations. Rice 2020, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Anuradha, G.; Kumar, R.R.; Vemireddy, L.R.; Sudhakar, R.; Donempudi, K.; Venkata, D.; Jabeen, F.; Narasimhan, Y.K.; Marathi, B.; et al. Identification of QTLs and possible candidate genes conferring sheath blight resistance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Zhang, F.; Pinson, S.R.; Edwards, J.D.; Jackson, A.K.; Xia, X.; Eizenga, G.C. Assessment of rice sheath blight resistance including associations with plant architecture, as revealed by genome-wide association studies. Rice 2022, 15, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, A.; Lin, R.; Zhang, D.; Qin, P.; Xu, L.; Ai, P.; Ding, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. The evolution and pathogenic mechanisms of the rice sheath blight pathogen. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Han, X.; Wang, Z.Y.; Ma, L.; Yuan, D.P.; Wu, J.N.; Zhu, X.F.; Liu, J.M.; Li, D.P.; et al. Inhibition of OsSWEET11 function in mesophyll cells improves resistance of rice to sheath blight disease. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 19, 2149–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, B.P.; Yu, R.R.; Lou, M.M.; Wang, Y.L.; Xie, G.L.; Li, H.Y.; Sun, G.C. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of rhizobacterium Burkholderia sp. strain R456 antagonistic to Rhizoctonia solani, sheath blight of rice. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 27, 2305–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Mazumdar, P.; Harikrishna, J.A.; Babu, S. Sheath blight of rice: A review and identification of priorities for future research. Planta 2019, 250, 1387–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Sunder, S.; Kumar, P. Sheath blight of rice: Current status and perspectives. Indian Phytopathol. 2016, 69, 340–351. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Xuan, Y.; Yi, J.; Xiao, G.; Yuan, D.P.; Li, D. Progress in rice sheath blight resistance research. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1141697. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Li, S.; Wei, S.; Sun, W. Strategies to manage rice sheath blight: Lessons from interactions between rice and Rhizoctonia solani. Rice 2021, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbafi, S.S.; Ham, J.H. An overview of rice QTLs associated with disease resistance to three major rice diseases: Blast, sheath blight, and bacterial panicle blight. Agronomy 2019, 9, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Na, D.Y.; Góngora-Canul, C.; Baireddy, S.; Lane, B.; Cruz, A.P.; Fernández-Campos, M.; Kleczewski, N.M.; Telenko, D.E.; Goodwin, S.B.; et al. Contour-based detection and quantification of tar spot stromata using red-green-blue (RGB) imagery. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 675975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Na, D.Y.; Góngora-Canul, C.; Jimenez-Beitia, F.E.; Goodwin, S.B.; Cruz, A.P.; Delp, E.J.; Acosta, A.G.; Lee, J.S.; Falconí, C.E.; et al. Optimizing Corn Tar Spot Measurement: A Deep Learning Approach Using Red-Green-Blue Imaging and the Stromata Contour Detection Algorithm for Leaf-Level Disease Severity Analysis. Plant Dis. 2025, 109, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Lan, Y.; Xu, C.; Liang, D. Detection of rice sheath blight using an unmanned aerial system with high-resolution color and multispectral imaging. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0187470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrad, A.O.; Li, W.; Lee, D.Y.; Wang, G.L.; Rodriguez-Saona, L.; Bonello, P. Machine learning-based presymptomatic detection of rice sheath blight using spectral profiles. Plant Phenomics 2020, 2020, 8954085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Tian, Y.; Yan, L.; Wang, B.; Wang, L.; Xu, J.; Wu, K. Diagnosing the symptoms of sheath blight disease on rice stalk with an in-situ hyperspectral imaging technique. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 209, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizenga, G.C.; Ali, M.L.; Bryant, R.J.; Yeater, K.M.; McClung, A.M.; McCouch, S.R. Registration of the Rice Diversity Panel 1 for Genomewide Association Studies. J. Plant Regist. 2014, 8, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.L.; McClung, A.M.; Jia, M.H.; Kimball, J.A.; McCouch, S.R.; Eizenga, G.C. A rice diversity panel evaluated for genetic and agro-morphological diversity between subpopulations and its geographic distribution. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2011, 159, 136–150. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K.; Tung, C.-W.; Eizenga, G.C.; Wright, M.H.; Ali, M.L.; Price, A.H.; Norton, G.J.; Islam, M.R.; Reynolds, A.; Mezey, J.; et al. Genome-wide association mapping reveals a rich genetic architecture of complex traits in Oryza sativa. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Mathworks, Inc. MATLAB Version 9.7.0.1190202 (R2019b); The Mathworks, Inc.: Natick, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Melnykov, I.; Melnykov, V. On -means algorithm with the use of Mahalanobis distances. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2014, 84, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comaniciu, D.; Meer, P. Mean shift: A robust approach toward feature space analysis. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 24, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peressotti, E.; Duchêne, E.; Merdinoglu, D.; Mestre, P. A semi-automatic non-destructive method to quantify grapevine downy mildew sporulation. J. Microbiol. Methods 2011, 84, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.I.K. A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate reproducibility. Biometrics 1989, 45, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, J.M.; Raghupathy, V.; Veluthambi, K. Enhanced sheath blight resistance in transgenic rice expressing an endochitinase gene from Trichoderma virens. Biotechnol. Lett. 2008, 31, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.; Eizenga, G.C. Rice sheath blight disease resistance identified in Oryza spp. accessions. Plant Dis. 2008, 92, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Ideta, O.; Ando, I.; Kunihiro, Y.; Hirabayashi, H.; Iwano, M.; Miyasaka, A.; Nemoto, H.; Imbe, T. Mapping QTLs for sheath blight resistance in the rice line WSS2. Breed. Sci. 2004, 54, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venu, R.C.; Jia, Y.; Gowda, M.; Jia, M.H.; Jantasuriyarat, C.; Stahlberg, E.; Li, H.; Rhineheart, A.; Boddhireddy, P.; Singh, P.; et al. RL-SAGE and microarray analysis of the rice transcriptome after Rhizoctonia solani infection. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2007, 278, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, D.E. Selection for resistance to rice sheath blight through number of infection cushions and lesion type. Plant Dis. 1992, 76, 721–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellareddygari, S.; Reddy, M.; Kloepper, J.; Lawrence, K.; Fadamiro, H. Rice sheath blight: A review of disease and pathogen management approaches. J. Plant Pathol. Microb. 2014, 5, 241. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Huang, J.; Cui, K.; Nie, L.; Wang, Q.; Yang, F.; Shah, F.; Yao, F.; Peng, S. Sheath blight reduces stem breaking resistance and increases lodging susceptibility of rice plants. Field Crops Res. 2012, 128, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshikawa, K.; Wang, S.B. Studies on lodging in rice plants. I. A general observation on lodged rice culms. Jpn. J. Crop Sci. 1990, 59, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwagi, T.; Sasaki, H.; Ishimaru, K. Factors responsible for decreasing sturdiness of the lower part in lodging of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Prod. Sci. 2005, 8, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Y.Z.; Yang, X.D.; Wang, M.E.; Zhu, Q.S. Effects of lodging at different filling stages on rice yield and grain quality. Rice Sci. 2012, 19, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setter, T.L.; Laureles, E.V.; Mazaredo, A.M. Lodging reduces yield of rice by self-shading and reductions in canopy photosynthesis. Field Crops Res. 1997, 49, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, M.C.; Lee, F. Rice sheath blight: A major rice disease. Plant Dis. 1983, 67, 829–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Chowdhury, S.; Chaudhuri, T.R.; Kundu, S. Differential behaviour of sheath blight pathogen Rhizoctonia solani in tolerant and susceptible rice varieties before and during infection. Plant Pathol. 2016, 65, 1333–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, K.S.; Tzeng, H.L.; Chen, S.; Wu, J.; Chen, T.J. Fuzzy c-means clustering with spatial information for image segmentation. Comput. Med. Imag. Grap. 2006, 30, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achanta, R.; Shaji, A.; Smith, K.; Lucchi, A.; Fua, P.; Süsstrunk, S. SLIC superpixels compared to state-of-the-art superpixel methods. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2012, 34, 2274–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Ma, Y.F.; Zhang, H.J. A spatial constrained K-means approach to image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Information, Communications and Signal Processing (ICICS 2003) and the Fourth Pacific Rim Conference on Multimedia (PCM 2003), Singapore, 15–18 December 2003; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Volume 2, pp. 738–742. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, E.L.; McDonald, B.A. Measuring quantitative virulence in the wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici Using high-throughput automated image analysis. Phytopathology 2014, 104, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| GSOR ID † | Name | Original Providing Country | Region | Subpopulation (Structure) ¶ | Subpopulation (PCA) # | Number of RGB Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 301065 | IR 8 | Philippines | Southeast Asia | Indica | Indica | 20 |

| 301091 | LAC 23 | Liberia | Africa | Tropical japonica | Tropical japonica | 12 |

| 301093 | Lemont | United States | North America | Tropical japonica | Tropical japonica | 26 |

| 301123 | Rathuwee | Sri Lanka | South Asia | Indica | Indica | 14 |

| 301332 | Cenit | Argentina | South America | Tropical japonica | Tropical japonica | 16 |

| 301341 | ARC 10376 | India | South Asia | Aus | Aus | 14 |

| 301351 | Rikuto Norin 21 | Japan | East Asia | Temperate japonica | ADMIX * | 14 |

| 301358 | Santhi Sufaid | Pakistan | South Asia | Aus | Aus | 26 |

| 301402 | LaGrue | United States | North America | Tropical japonica | Tropical japonica | 4 |

| 301406 | Jasmine85 | Philippines | Southeast Asia | Indica | Indica | 22 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| filter kernel | uniform |

| filter size | |

| initial learning rate | 0.001 |

| training option | SGDM with 0.9 momentum |

| maximum epochs | 30 |

| minimum batch size | 100 |

| Disease Severity Measurement | Methods | Location Shift | Scale Shift | Accuracy | Precision | Lin’s Concordance Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute lesion height (cm) | Visual vs. ImageJ | 0.465 | 1.1757 | 0.8919 | 0.9259 | 0.8258 |

| Visual vs. PCC-KMC | 0.3799 | 1.1127 | 0.9278 | 0.9398 | 0.8719 | |

| Visual vs. PCC-KMC-CNN | 0.5623 | 1.0465 | 0.8627 | 0.9026 | 0.7787 | |

|

Proportional lesion height | Visual vs. ImageJ | 0.4664 | 1.1704 | 0.8977 | 0.9339 | 0.8384 |

| Visual vs. PCC-KMC | 0.4072 | 1.0792 | 0.9210 | 0.9415 | 0.8671 | |

| Visual vs. PCC-KMC-CNN | 0.6118 | 1.0311 | 0.8420 | 0.8954 | 0.7539 | |

|

Absolute lesion area (cm2) | ImageJ vs. PCC-KMC | −0.2149 | 0.9799 | 0.9772 | 0.9659 | 0.9439 |

| ImageJ vs. PCC-KMC-CNN | 0.0576 | 1.1022 | 0.9936 | 0.9659 | 0.9598 | |

| PCC-KMC vs. PCC-KMC-CNN | −0.1449 | 0.9876 | 0.9895 | 0.9536 | 0.9437 | |

|

Proportional lesion area | ImageJ vs. PCC-KMC | −0.1449 | 0.9876 | 0.9895 | 0.9536 | 0.9437 |

| ImageJ vs. PCC-KMC-CNN | 0.1483 | 1.1546 | 0.9791 | 0.9689 | 0.9486 |

| Disease Severity Measurement | Methods | Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute lesion height (cm) | ImageJ | 0.8045 |

| vs. | PCC-KMC | 0.8403 |

| Absolute diseased area (cm2) | PCC-KMC-CNN | 0.8577 |

| Proportional lesion height | ImageJ | 0.7855 |

| vs. | PCC-KMC | 0.8173 |

| Proportional diseased area | PCC-KMC-CNN | 0.8209 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, D.-Y.; Na, D.-Y.; Heo, Y.S.; Wang, G.-L. Digital Image Quantification of Rice Sheath Blight: Optimized Segmentation and Automatic Classification. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232478

Lee D-Y, Na D-Y, Heo YS, Wang G-L. Digital Image Quantification of Rice Sheath Blight: Optimized Segmentation and Automatic Classification. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232478

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Da-Young, Dong-Yeop Na, Yong Seok Heo, and Guo-Liang Wang. 2025. "Digital Image Quantification of Rice Sheath Blight: Optimized Segmentation and Automatic Classification" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232478

APA StyleLee, D.-Y., Na, D.-Y., Heo, Y. S., & Wang, G.-L. (2025). Digital Image Quantification of Rice Sheath Blight: Optimized Segmentation and Automatic Classification. Agriculture, 15(23), 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232478