Integrated Morphological, Physicochemical, Metabolomic, and Transcriptomic Analyses Elucidate the Mechanism Underlying Melon (Cucumis melo L.) Peel Cracking

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

2.2. Fruit Peel Structure Observation

2.3. Determination of Cell Wall Components and Cell Wall-Related Enzyme Activities

2.4. Metabolome Analysis

2.5. RNA Extraction and cDNA Library Construction

2.6. RNA-seq Analysis

2.7. Screening and Functional Annotation of DEGs

2.8. Determination of Lignin Monomer Content in Fruit Peels

2.9. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis (RT-qPCR)

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

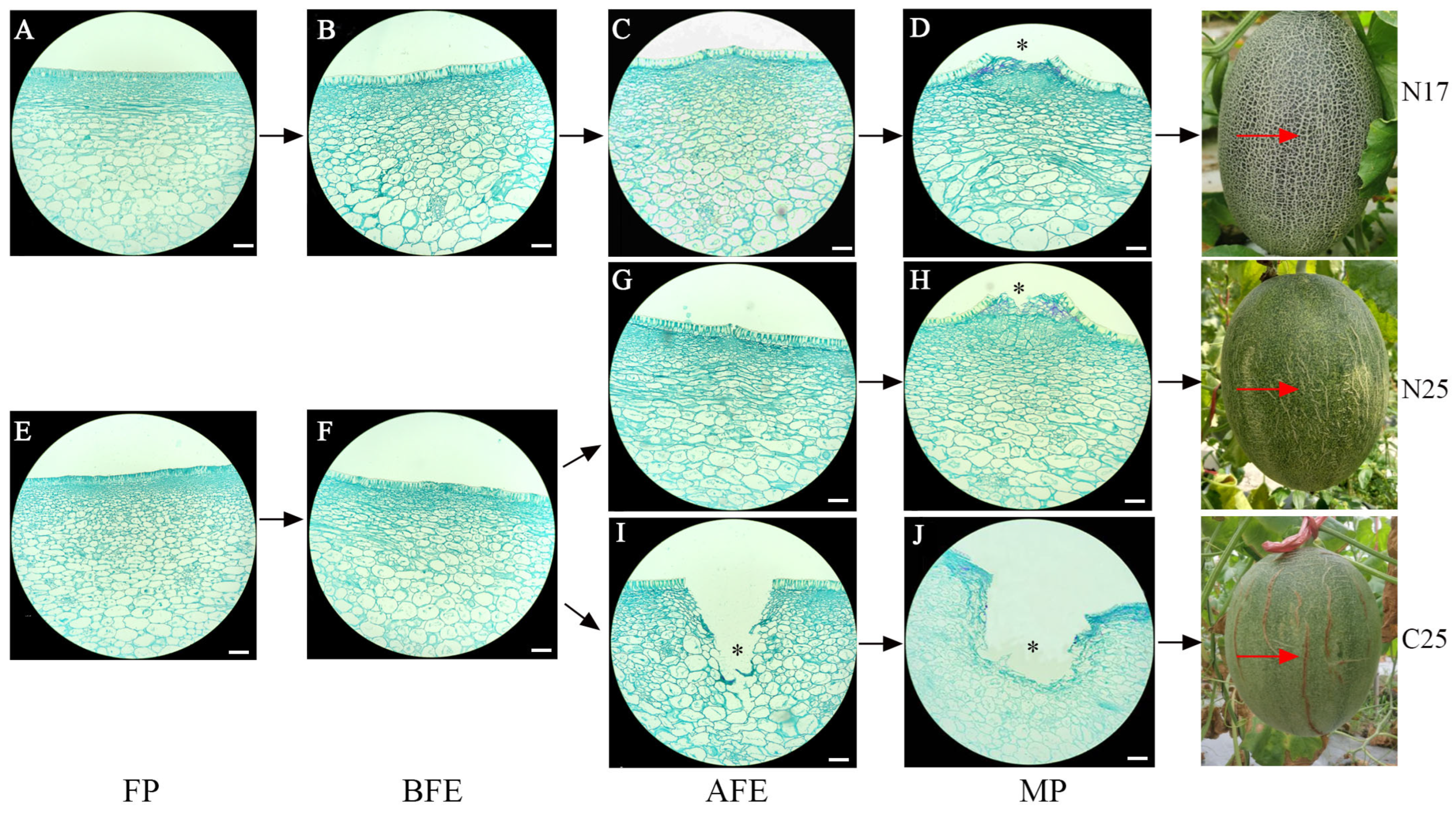

3.1. Changes in Fruit Peel Structure

3.2. Comparison of Fruit Peel Structure Between Cracking and Non-Cracking Fruits

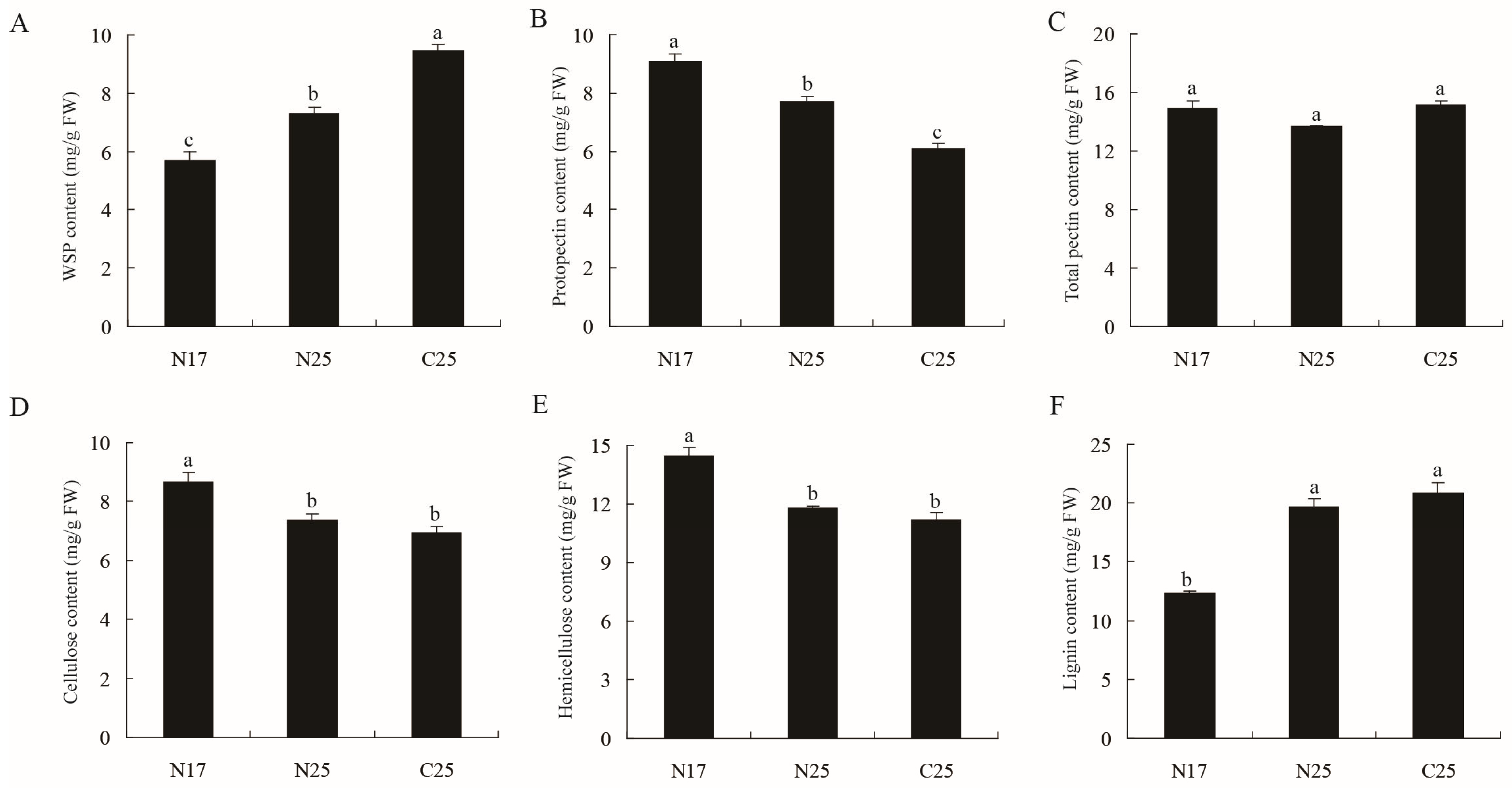

3.3. Determination of Cell Wall Components in Fruit Peels

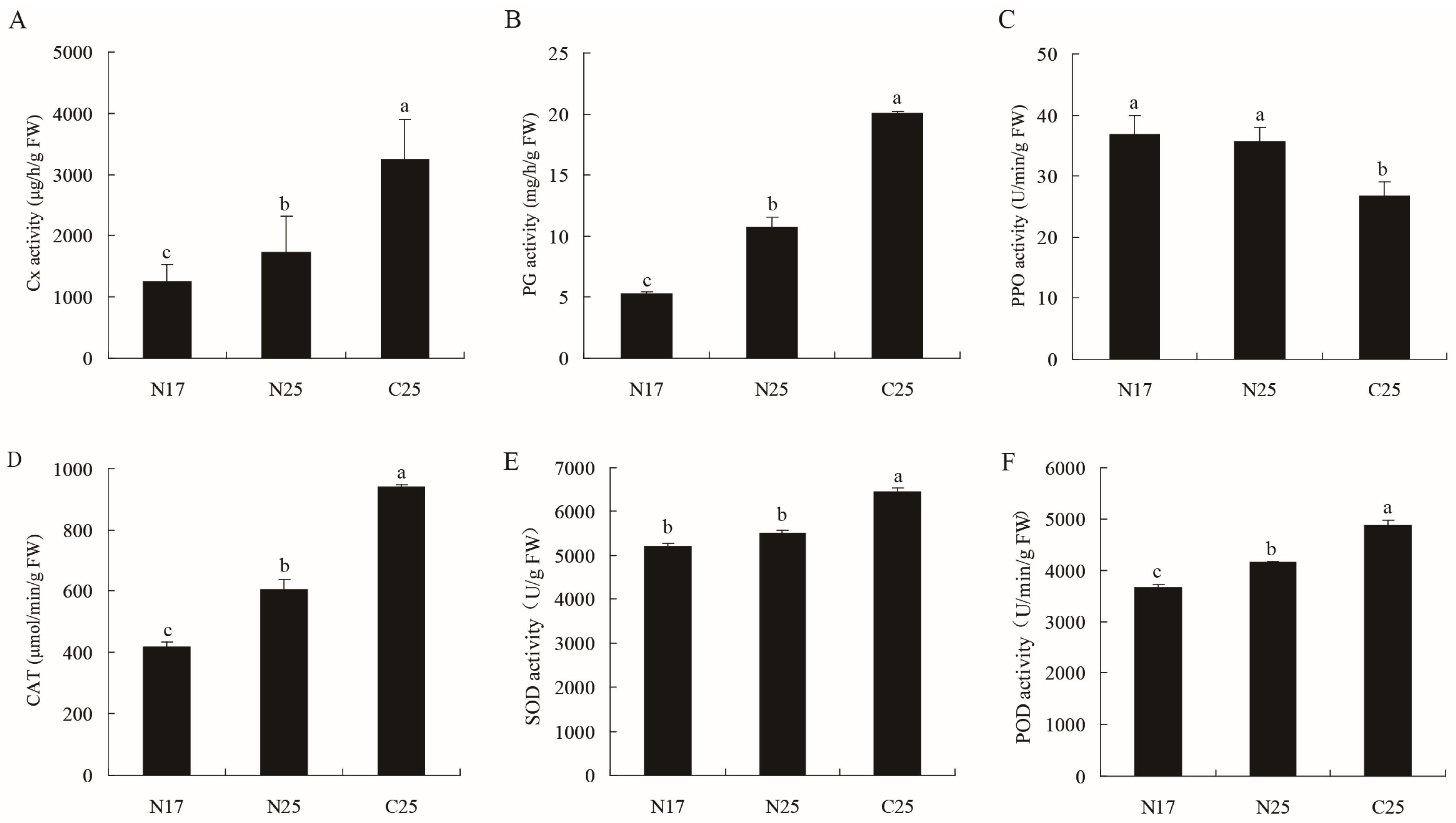

3.4. Analysis of Enzyme Activities in Fruit Peels

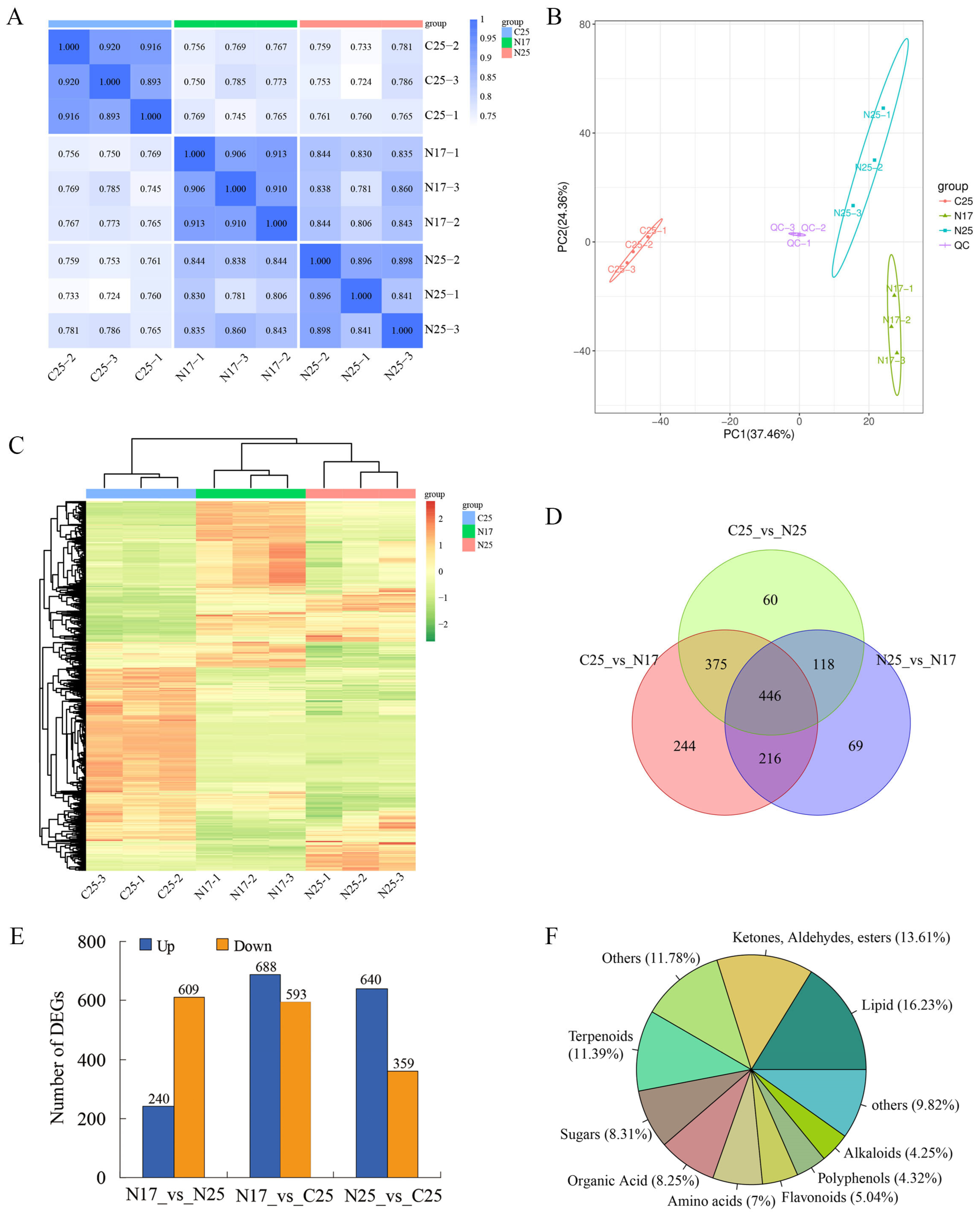

3.5. Metabolomic Analysis of Various Types of Fruit Peels

3.6. Transcriptome Sequencing and Differentially Expressed Genes Analysis

3.7. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

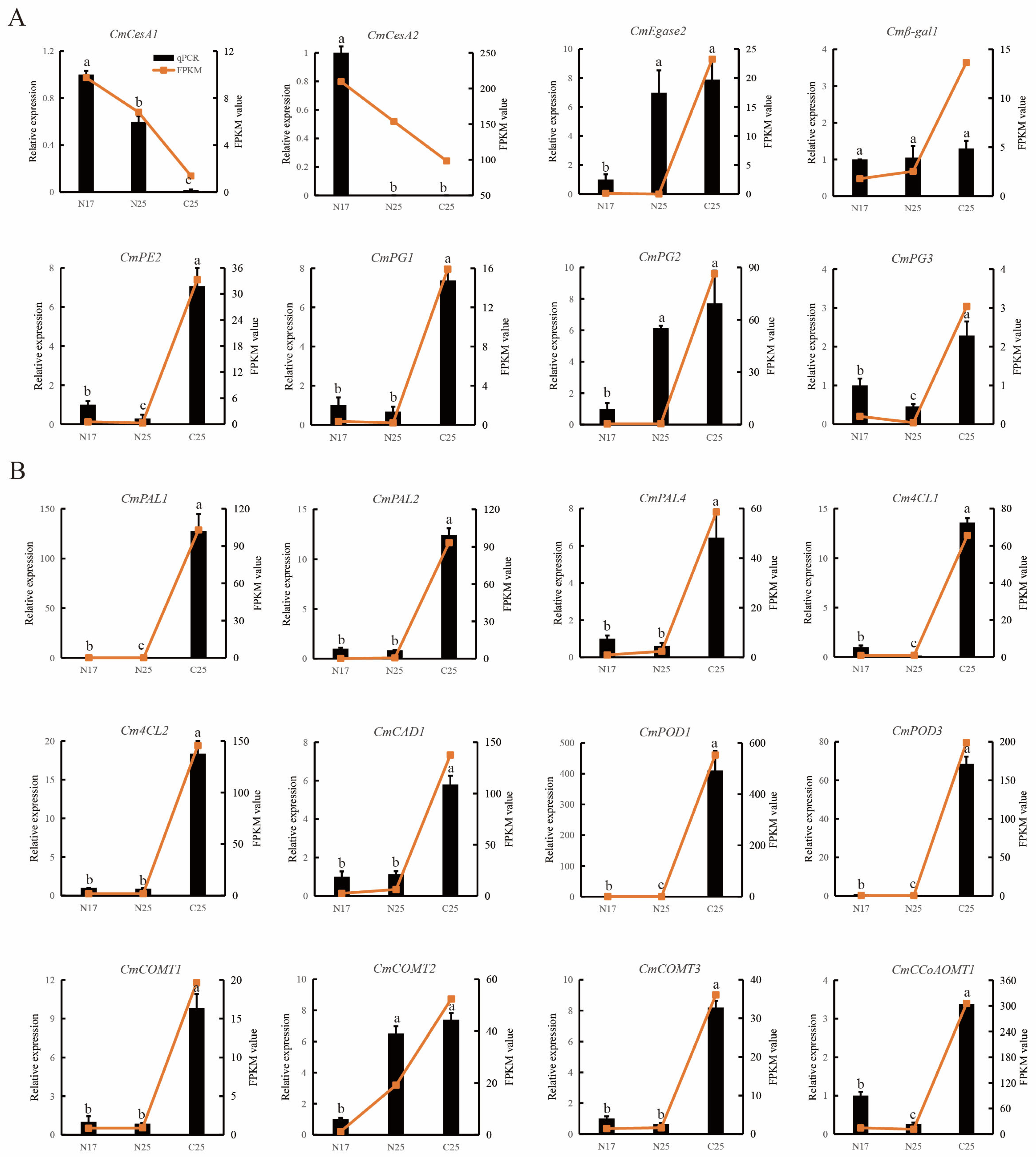

3.8. Expression Analysis of Cell Wall-Related Genes

3.9. Expression Analysis of DEGs Implicated in Lignin Biosynthesis

3.10. RT-qPCR Validation of RNA-seq Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davarpanah, S.; Tehranifar, A.; Davarynejad, G.; Abadia, J.; Khorasani, R. Effects of foliar applications of zinc and boron nano-fertilizers on pomegranate (Punica granatum cv. Ardestani) fruit yield and quality. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 210, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.G.; Gao, X.M.; Ma, Z.L.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.N.; Shi, W.Q. Metabolomic and transcriptomic proffling of three types of litchi pericarps reveals that changes in the hormone balance constitute the molecular basis of the fruit cracking susceptibility of Litchi chinensis cv. Baitangying. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 5295–5308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumann, C.; Knoche, M. Swelling of cell walls in mature sweet cherry fruit: Factors and mechanisms. Planta 2020, 251, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.W.; Zhao, H.Q.; Hou, L.; Zhang, C.X.; Bo, W.H.; Pang, X.M.; Li, Y.Y. HPLC-MS/MS-based and transcriptome analysis reveal the effects of ABA and MeJA on jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.) cracking. Food Chem. 2023, 421, 136155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.E.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Hu, E.M.; Zhou, R.; Jiang, F.L. The composition of pericarp, cell aging, and changes in water absorption in two tomato genotypes: Mechanism, factors, and potential role in fruit cracking. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2016, 38, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Guan, L.; Fan, X.C.; Zhang, T.; Dong, T.; Liu, C.; Fang, J. Anatomical characteristics associated with different degrees of berry cracking in grapes. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 261, 108992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargel, H.; Neinhuis, C. Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) fruit growth and ripening as related to the biomechanical properties of fruit skin and isolated cuticle. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 1049–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjipieri, M.; Georgiadou, E.C.; Drogoudi, P.; Fotopoulos, V.; Manganaris, G.A. The efficacy of acetylsalicylic acid, spermidine and calcium preharvest foliar spray applications on yield efficiency, incidence of physiological disorders and shelflife performance of loquat fruit. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 289, 110439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, C.; Figueroa, C.R.; Turner, A.; Munne-Bosch, S.; Munoz, P.; Schreiber, L.; Zeisler, V.; Marin, J.C.; Balbontin, C. Abscisic acid applied to sweet cherry at fruit set increases amounts of cell wall and cuticular wax components at the ripe stage. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 283, 110097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruggenwirth, M.; Knoche, M. Mechanical properties of skins of sweet cherry fruit of differing susceptibilities to cracking. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2016, 141, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.M.; Yuan, W.Q.; Wang, H.C.; Li, J.G.; Huang, H.B.; Shi, L.; Yin, J. Linking cracking resistance and fruit desiccation rate to pericarp structure in litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2004, 79, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Goukh, A.B.A.; Bashir, H.A. Changes in pectic enzymes and cellulase activity during guava fruit ripening. Food Chem. 2003, 83, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.Z.; Sun, M.T.; Wu, Z.; Yu, L.; Yu, Q.H.; Tang, Y.P.; Jiang, F.L. LncRNA regulates tomato fruit cracking by coordinating gene expression via a hormone-redox-cell wall network. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ma, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Qian, M.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, W.; Fan, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L. Genome-wide analysis of polygalacturonase gene family from pear genome and identification of the member involved in pear softening. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhu, B.; Huang, W.; Chen, J.; Wang, F.; Chen, Y.; Wang, M.; Lai, H.; Zhou, Y. Genome-wide identification of the expansin gene family in netted melon and their transcriptional responses to fruit peel cracking. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1332240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, U.C.; Payyavula, R.S.; Labbé, J.L.; Engle, N.; Bali, G.; Jawdy, S.S.; Sykes, R.W.; Davis, M.; Ragauskas, A.; Tuskan, G.A. Down-regulation of KORRIGAN-like endo-β-1, 4-glucanase genes impacts carbon partitioning, mycorrhizal colonization and biomass production in Populus. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Duan, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, W.; Sun, D.; Hu, H.; Xie, J. Transcriptome analysis of atemoya pericarp elucidates the role of polysaccharide metabolism in fruit ripening and cracking after harvest. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.C.; Wu, J.Y.; Zhang, H.N.; Shi, S.Y.; Liu, L.Q.; Shu, B.; Liang, Q.Z.; Xie, J.H.; Wei, Y.Z. De novo assembly and characterization of pericarp transcriptome and identification of candidate genes mediating fruit cracking in Litchi chinensis Sonn. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 17667–17685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.G.; Gao, X.M.; Ma, Z.L.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.N. Analysis of the molecular basis of fruit cracking susceptibility in Litchi chinensis cv. Baitangying by transcriptome and quantitative proteome profiling. J. Plant Physiol. 2019, 234, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Tian, H.; Yan, C.; Jia, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Jiang, C.; Li, Y.; Jiang, J.; Fang, L.; et al. RNA-seq analysis of watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) to identify genes involved in fruit cracking. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 248, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Zaplana, A.; Garzana, G.; Ding, L.; Chaumount, F.; Carvajal, M. Aquaporins involvement in the regulation of melon (Cucumis melo L.) fruit cracking under different nutrient (Ca, B and Zn) treatments. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 201, 104981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.Y.; Li, J.X.; Raza, M.A.; Zou, X.; Cao, L.; Rao, L.; Chen, L. Inheritance of fruit cracking resistance of melon (Cucumis melo L.) fitting E-0 genetic model using major gene plus polygene inheritance analysis. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 189, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.L.; Lopez, A.; Jeon, S.; de Freitas, S.T.; Yu, Q.H.; Wu, Z.; Labavitch, J.M.; Tian, S.K.; Powell, A.L.T.; Mitcham, E. Disassembly of the fruit cell wall by the ripening-associated polygalacturonase and expansin influences tomato cracking. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, C.; Sitzenstock, S.; Erz, L.; Knoche, M. Decreased deposition and increased swelling of cell walls contribute to increased cracking susceptibility of developing sweet cherry fruit. Planta 2020, 252, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabannes, M.; Barakate, A.; Lapierre, C.; Marita, J.M.; Ralph, J.; Pean, M.; Danoun, S.; Halpin, C.; Grima-Pettenati, J.; Boudet, A.M. Strong decrease in lignin content without significant alteration of plant development is induced by simultaneous downregulation of cinnamoyl CoA reductase (CCR) and cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD) in tobacco plants. Plant J. 2001, 28, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Shaker, K.; Heinzel, N.; Ralph, J.; Gális, I.; Baldwin, I.T. Environmental stresses of field growth allow cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase-deficient Nicotiana attenuata plants to compensate for their structural deficiencies. Plant Physiol. 2012, 159, 1545–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Acker, R.; Dejardin, A.; Desmet, S.; Hoengenaert, L.; Vanholme, R.; Morreel, K.; Laurans, F.; Kim, H.; Santoro, N.; Foster, C.; et al. Different routes for conifer- and sinapaldehyde and higher saccharification upon deficiency in the dehydrogenase CAD1. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 1018–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, H.; Yu, X.; Wang, X.; Shi, Q. Cloning and expression analyzing of one BADH gene CmBADH of muskmelon under abiotic stress. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2013, 40, 905–912. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhu, B.; Liao, D.; Yun, T.; Huang, W.; Chen, Y.; et al. Genome-wide characterization of HSP90 gene family in Chinese pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch.) and their expression patterns in response to heat and cold stresses. Agronomy 2023, 13, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Wall extensibility: Its nature, measurement and relationship to plant growth. New Phytol. 1993, 124, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.; Kaur, N.; Singh, H. Pericarp and pedicel anatomy in relation to fruit cracking in lemon (Citrus limon L. Burm.). Sci. Hortic. 2019, 246, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadivi-Khub, A. Physiological and genetic factors influencing fruit cracking. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2015, 37, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, F.; Wu, Z.; Cui, S.; Lv, H.; Yu, L. Differences of reactive oxygen species metabolism in top, middle and bottom part of epicarp and mesocarp influence tomato fruit cracking. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 95, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, E.; Fernandez, M.D.; Hernandez, J.C.; Parra, J.P.; Espana, L.; Heredia, A.; Cuartero, J. Tomato fruit continues growing while ripening, affecting cuticle properties and cracking. Physiol. Plant. 2012, 146, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, J.; Bres, C.; Just, D.; Garcia, V.; Mauxion, J.P.; Marion, D.; Bakan, B.; Joubès, J.; Domergue, F.; Rothan, C. Analyses of tomato fruit brightness mutants uncover both cutin-deficient and cutin-abundant mutants and a new hypomorphic allele of GDSL lipase. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 888–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Chen, S.Y.; Liu, G.T.; Jia, X.Y.; Haq, S.; Deng, Z.J.; Luo, D.X.; Li, R.; Gong, Z.H. Morphological, physiochemical, and transcriptome analysis and CaEXP4 identification during pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) fruit cracking. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 297, 110982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbontín, C.; Ayala, H.; Rubilar, J.; Cote, J.; Figueroa, C.R. Transcriptional analysis of cell wall and cuticle related genes during fruit development of two sweet cherry cultivars with contrasting levels of cracking tolerance. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2014, 74, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zeng, H.; Zou, M.; Lu, C. An overview of the roles of cell wall modification in fruit pericarp cracking. Chin. J. Trop. Crop. 2011, 32, 1995–1999. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dautt-Castro, M.; Lopez-Virgen, A.G.; Ochoa-Leyva, A.; Contreras-Vergara, C.A.; Sortillon-Sortillon, A.P.; Martinez-Tellez, M.A.; Gonzalez-Aguilar, G.A.; Casas-Flores, J.S.; Sanudo-Barajas, A.; Kuhn, D.N.; et al. Genome-wide identification of mango (Mangifera indica L.) polygalacturonases, expression analysis of family members and total enzyme activity during fruit ripening. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, M.; Kay, P.; Wilson, S.; Swain, S.M. Arabidopsis dehiscence zone polygalacturonase1 (ADPG1), ADPG2, and QUARTET2 are polygalacturonases required for cell separation during reproductive development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, X.; Zhang, R.; Liu, D.; Gao, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Wu, Y.; et al. Hypersensitive ethylene signaling and ZMdPG1 expression lead to fruit softening and dehiscence. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, X.I. Advances in research on the effects of polygalacturonase and cellulase on fruit ripening. J. Fruit Sci. 2005, 22, 532–536. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.M.; Wang, H.C.; Gao, F.; Huang, H.B. A comparative study of the pericarp of litchi cultivars susceptible and resistant to fruit cracking. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 1999, 4, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Bai, M.; Tong, P.; Hu, Y.; Yang, M.; Wu, H. CELLULASE6 and MANNANASE7 affect cell differentiation and silique dehiscence. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 2186–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Cell wall loosening by expansins. Plant Physiol. 1998, 118, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Loosening of plant cell walls by expansins. Nature 2000, 407, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jones, L.; McQueen-Mason, S. Expansins and cell growth. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2003, 6, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.K.C.; Braam, J.; Fry, S.C.; Nishitani, K. The XTH family of enzymes involved in xyloglucan endotransglucosylation and endohydrolysis: Current perspectives and a new unifying nomenclature. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002, 43, 1421–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedes, E.; Zarra, I.; Hoson, T.; Herbers, K.; Sonnewald, U.; Lorences, E.P. Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase and cell wall extensibility. J. Plant Physiol. 2011, 168, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummell, D.A.; Howie, W.J.; Ma, C.; Dunsmuir, P. Postharvest fruit quality of transgenic tomatoes suppressed in expression of a ripening-related expansin. Postharvest Biol. Tec. 2002, 25, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Duan, X.; Song, L. Differential expression of litchi XET genes in relation to fruit growth. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2006, 44, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasai, S.; Hayama, H.; Kashimura, Y.; Kudo, S.; Osanai, Y. Relationship between fruit cracking and expression of the expansin gene MdEXPA3 in ‘Fuji’ apples (Malus domestica Borkh.). Sci. Hortic. 2008, 116, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, W.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y. Differential expression of two expansin genes in developing fruit of cracking-susceptible and –resistant litchi cultivars. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2006, 131, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musel, G.; Schindler, T.; Bergfeld, R.; Ruel, K.; Jacquet, G.; Lapierre, C.; Speth, V.; Schopfer, P. Structure and distribution of lignin in primary and secondary cell walls of maize coleoptiles analyzed by chemical and immunological probes. Planta 1997, 201, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Río, J.C.; Rencoret, J.; Gutíerrez, A.; Elder, T.; Kim, H.; Ralph, J. Lignin monomers from beyond the canonical monolignol biosynthetic pathway: Another brick in the wall. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 4997–5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liang, L.; Jiang, Y.M.; Chen, J.J. Changes in metabolisms of antioxidant and cell wall in three pummelo cultivars during postharvest storage. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chantreau, M.; Sibout, R.; Hawkins, S. Plant cell wall lignification and monolignol metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.G.; Huang, X.M.; Huang, H.B. Comparison of the activity of enzymes related to cell wall metabolism in pericarp between litchi cultivars susceptible and resistant to fruit cracking. J. Plant Physiol. Mol. Biol. 2003, 2, 141–146. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.T.; Yu, J.; Zhao, M.; Wang, M.J.; Yang, G.S. Transcriptome analysis of metabolisms related to fruit cracking during ripening of a cracking-susceptible grape berry cv. Xiangfei (Vitis vinifera L.). Genes Genom. 2020, 42, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ding, G.; Wang, X.; Fu, C.; Qin, G.; Yang, J.; Cang, G.; Wen, P. Changes of histological structure and water potential of huping jujube fruit cracking. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2013, 46, 4558–4568. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Karkonen, A.; Kuchitsu, K. Reactive oxygen species in cell wall metabolism and development in plants. Phytochemistry 2015, 112, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahedi, S.M.; Hosseini, M.S.; Meybodi, N.D.H.; Abadia, J.; Germ, M.; Gholami, R.; Abdelrahman, M. Evaluation of drought tolerance in three commercial pomegranate cultivars using photosynthetic pigments, yield parameters and biochemical traits as biomarkers. Agric. Water. Manag. 2022, 261, 107357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yi, H.; Hu, G. Analysis of cracking resistance and physiological characteristics on Xinjiang muskmelon. Acta Bot. Boreali-Occident. Sin. 2023, 43, 1146–1157. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, C.; Zhu, B.; Tian, L.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Y. Integrated Morphological, Physicochemical, Metabolomic, and Transcriptomic Analyses Elucidate the Mechanism Underlying Melon (Cucumis melo L.) Peel Cracking. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2475. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232475

Hu Y, Li Y, Zhang T, Wang C, Zhu B, Tian L, Wang M, Zhou Y. Integrated Morphological, Physicochemical, Metabolomic, and Transcriptomic Analyses Elucidate the Mechanism Underlying Melon (Cucumis melo L.) Peel Cracking. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2475. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232475

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Yanping, Yuxin Li, Tingting Zhang, Chongchong Wang, Baibi Zhu, Libo Tian, Min Wang, and Yang Zhou. 2025. "Integrated Morphological, Physicochemical, Metabolomic, and Transcriptomic Analyses Elucidate the Mechanism Underlying Melon (Cucumis melo L.) Peel Cracking" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2475. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232475

APA StyleHu, Y., Li, Y., Zhang, T., Wang, C., Zhu, B., Tian, L., Wang, M., & Zhou, Y. (2025). Integrated Morphological, Physicochemical, Metabolomic, and Transcriptomic Analyses Elucidate the Mechanism Underlying Melon (Cucumis melo L.) Peel Cracking. Agriculture, 15(23), 2475. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232475