Research on Accurate Weed Identification and a Variable Application Method in Maize Fields Based on an Improved YOLOv11n Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

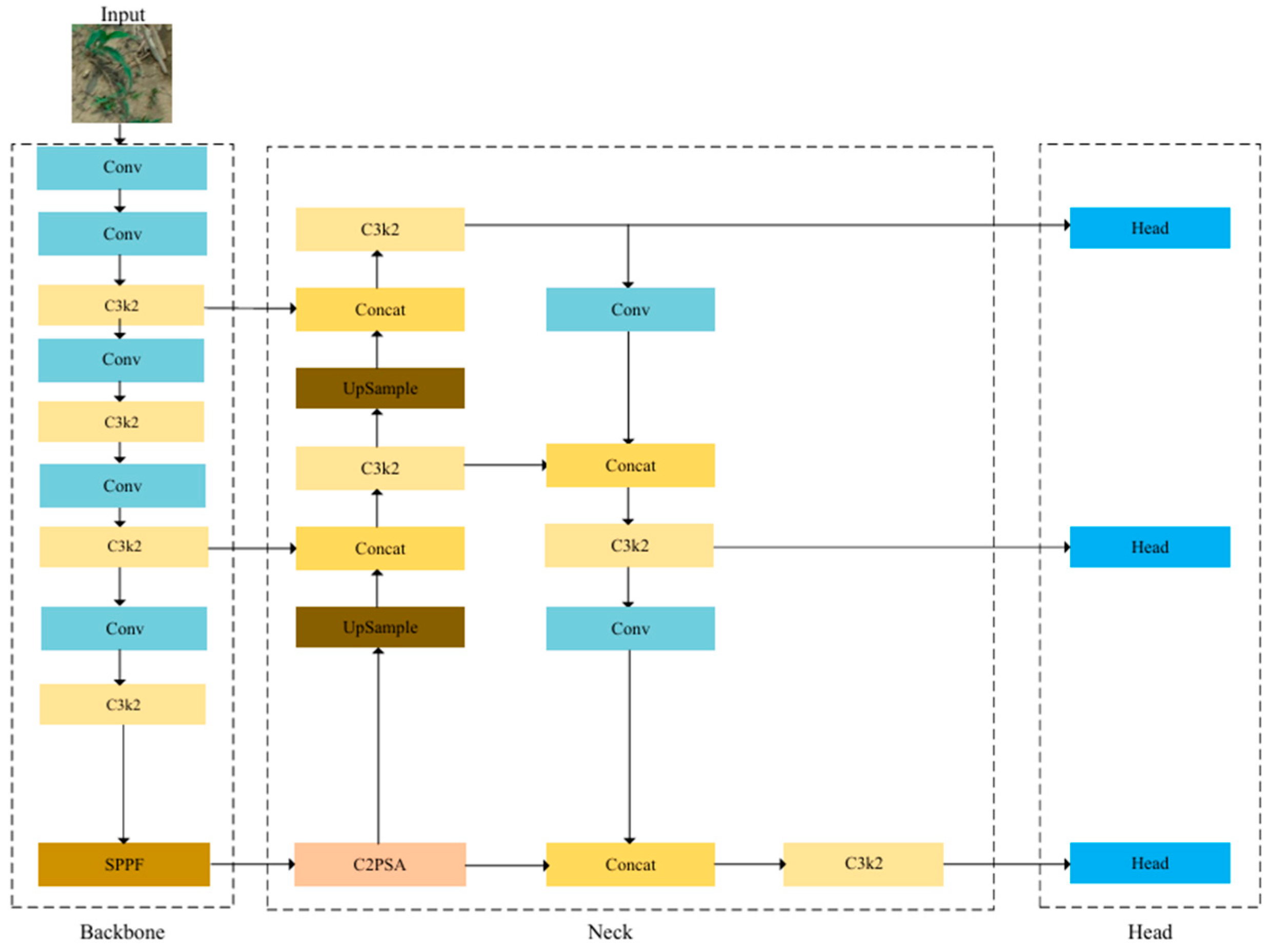

2.1. YOLOv11n Network Architecture

2.2. YOLOv11n-OSAW Network Structure

- (1)

- ODConv is introduced to replace the standard convolution in the C3K2 module, which strengthens multi-scale feature extraction, with a particular focus on small weed targets. This improvement enables the model to capture fine-grained features of tiny weeds that are easily overlooked by conventional convolution.

- (2)

- The SEAM attention mechanism is incorporated to enhance the model’s discriminative capability in scenarios where maize plants and weeds are mutually occluded. By adaptively emphasizing feature channels related to weeds and suppressing irrelevant maize channels, SEAM effectively mitigates occlusion-induced interference.

- (3)

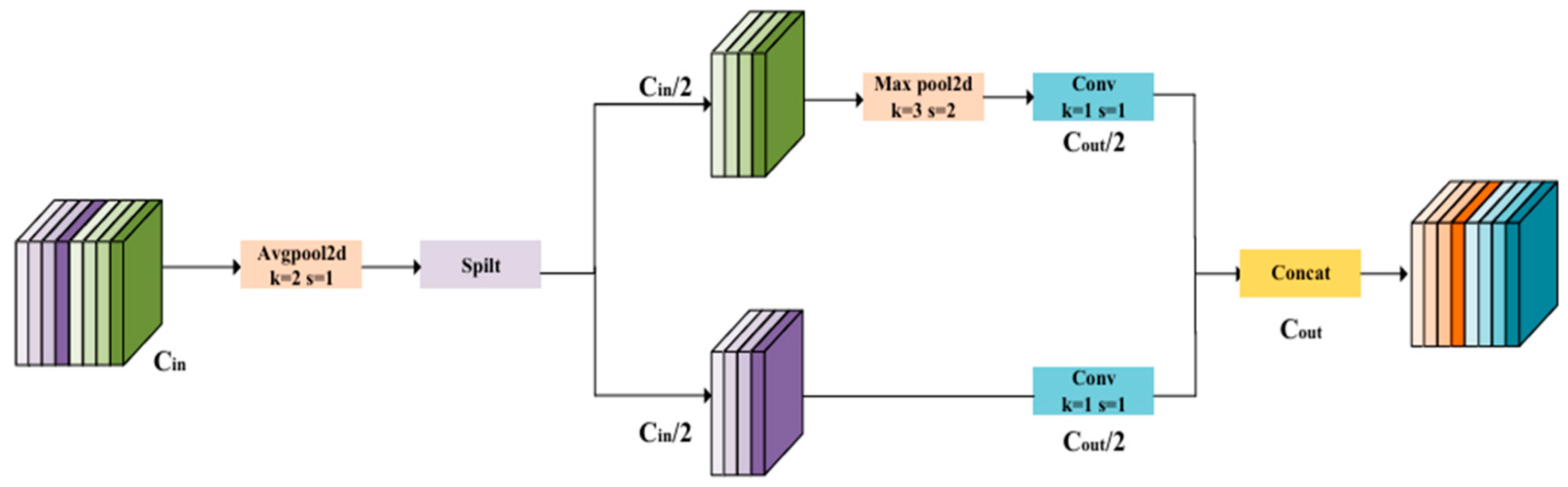

- A lightweight ADown module replaces specific convolutional structures in the baseline model. This modification significantly reduces model complexity and computational cost, facilitating efficient deployment on UAV platforms while preserving the original detection performance.

- (4)

- The original CIoU loss is substituted with WIoU. Leveraging a dynamic, non-monotonic focusing mechanism, WIoU optimizes convergence during training and improves bounding-box regression accuracy, which is crucial for the precise localization of irregularly shaped weeds.

2.2.1. ODConv Module

2.2.2. SEAM Attention Mechanism

2.2.3. ADown Module

2.2.4. WIoU Function

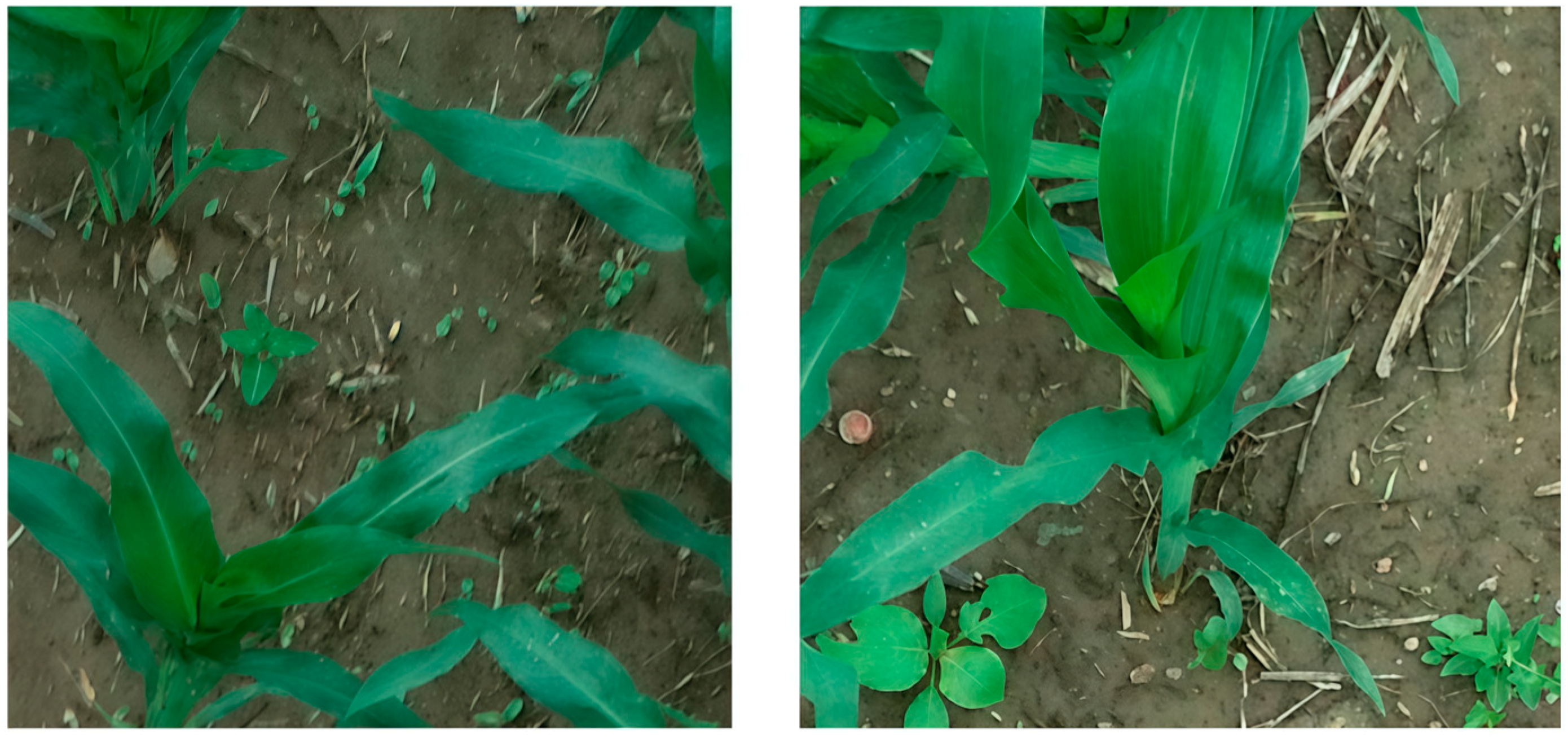

2.3. Dataset Construction

2.4. Model Training

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

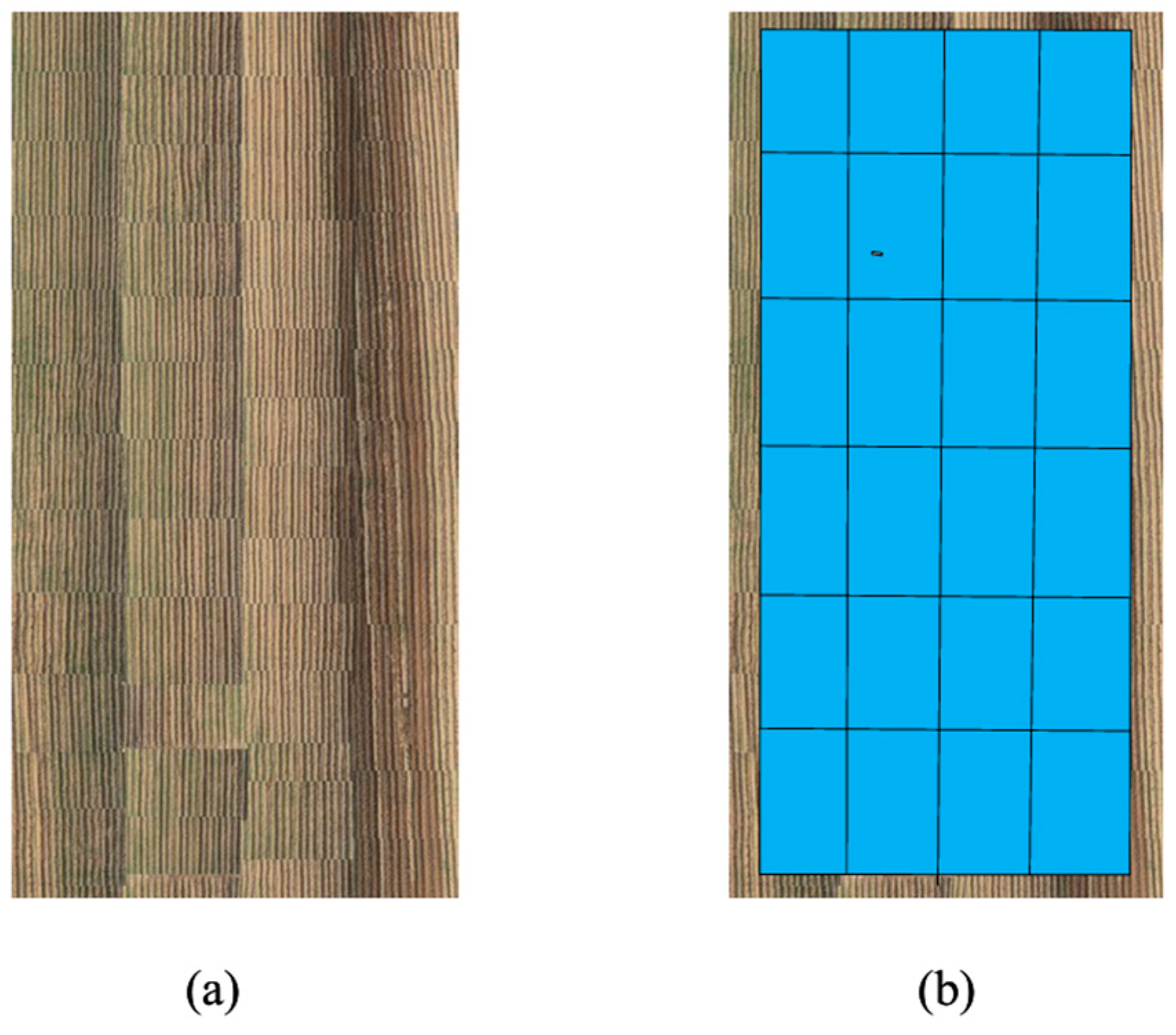

2.6. Prescription Map Generation

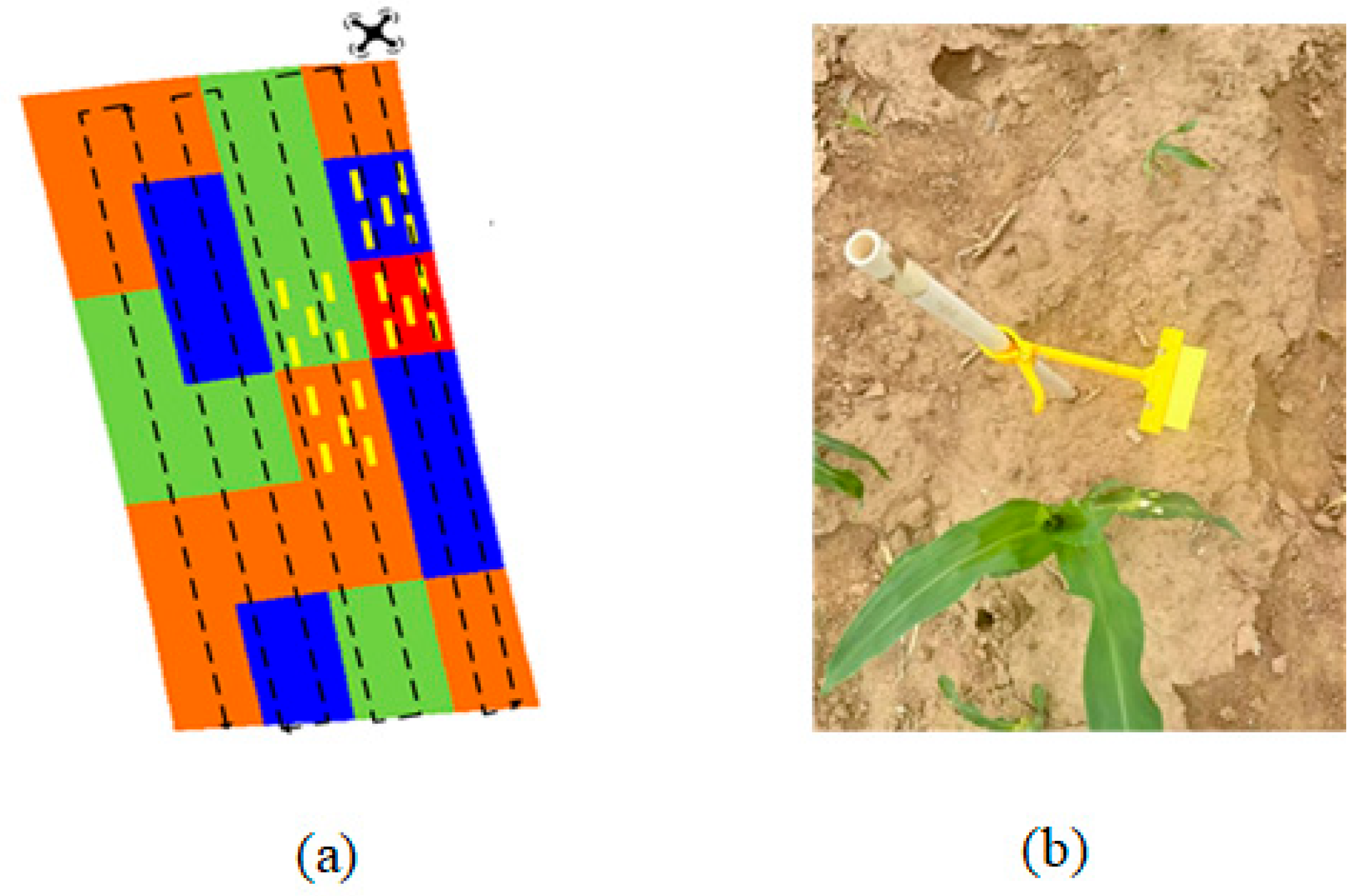

2.7. Variable Spraying Experiment Based on Prescription Maps

2.8. Indicators for Evaluating the Effectiveness of Drone Spraying

2.9. Test Platform Configuration

3. Test Results

3.1. Ablation Experiment

3.2. Cross-Sectional Comparison Test of Attention Mechanisms

3.3. Loss Function Cross-Sectional Comparison Test

3.4. Comparative Tests of Different Models

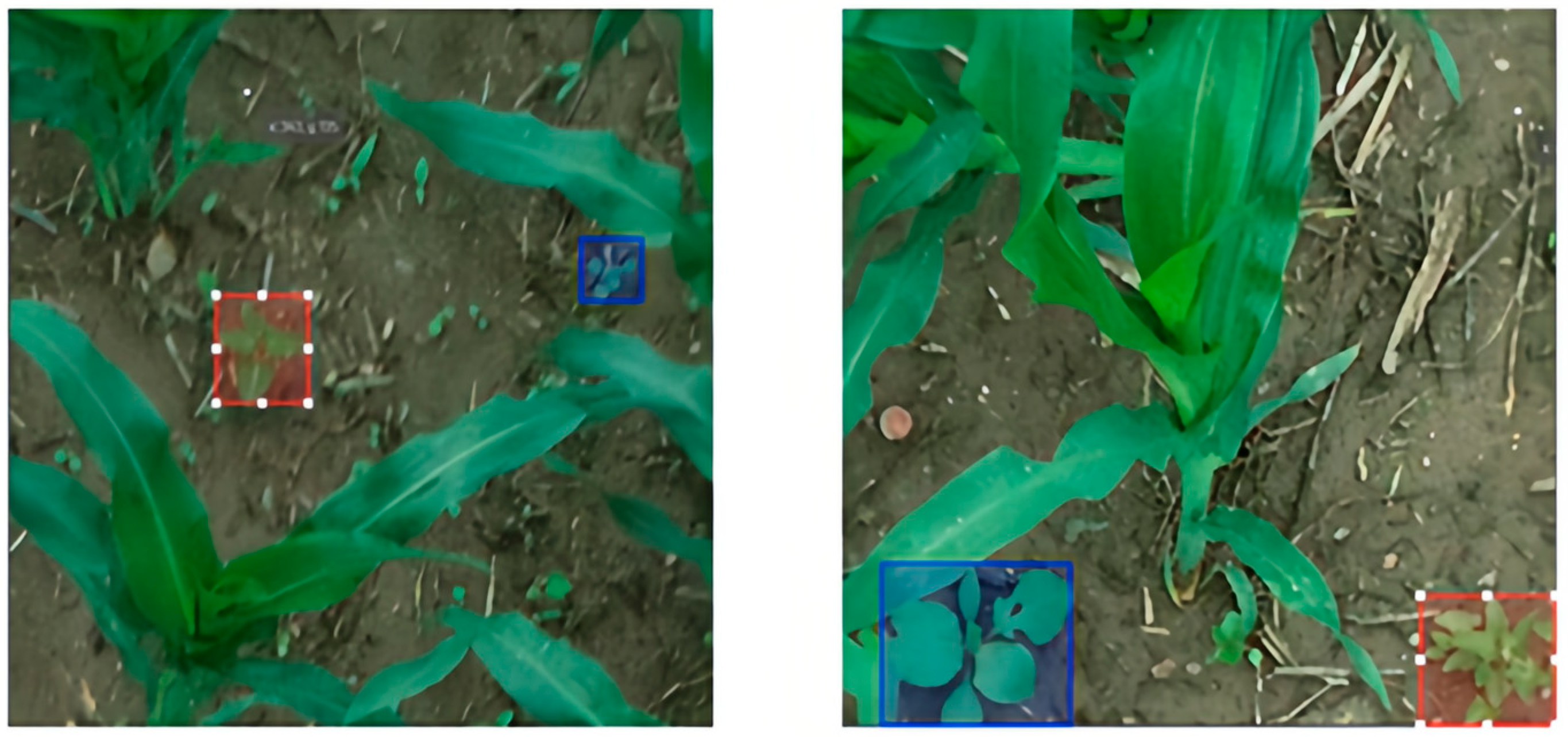

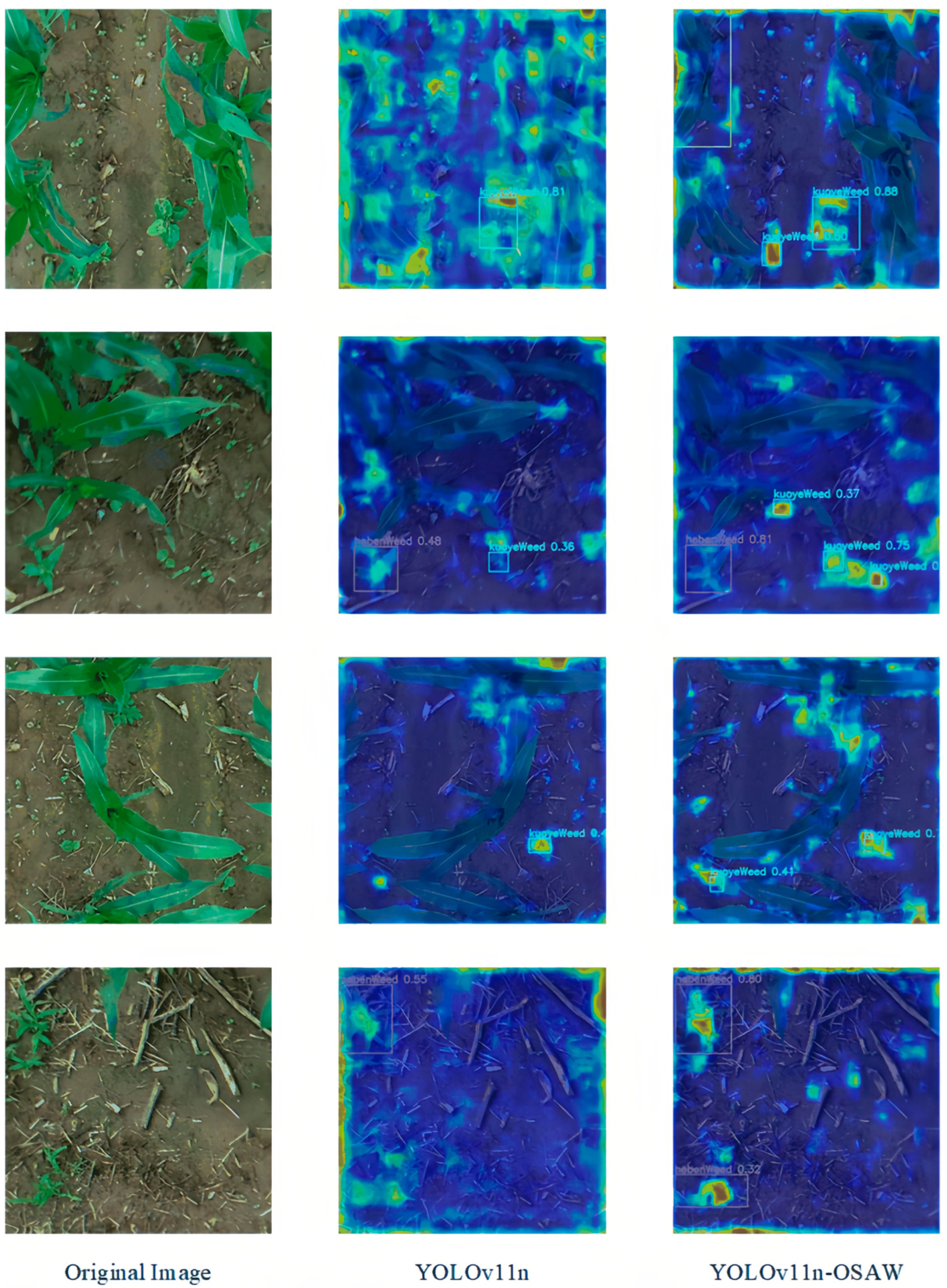

3.5. Visualization and Analysis of Object Detection

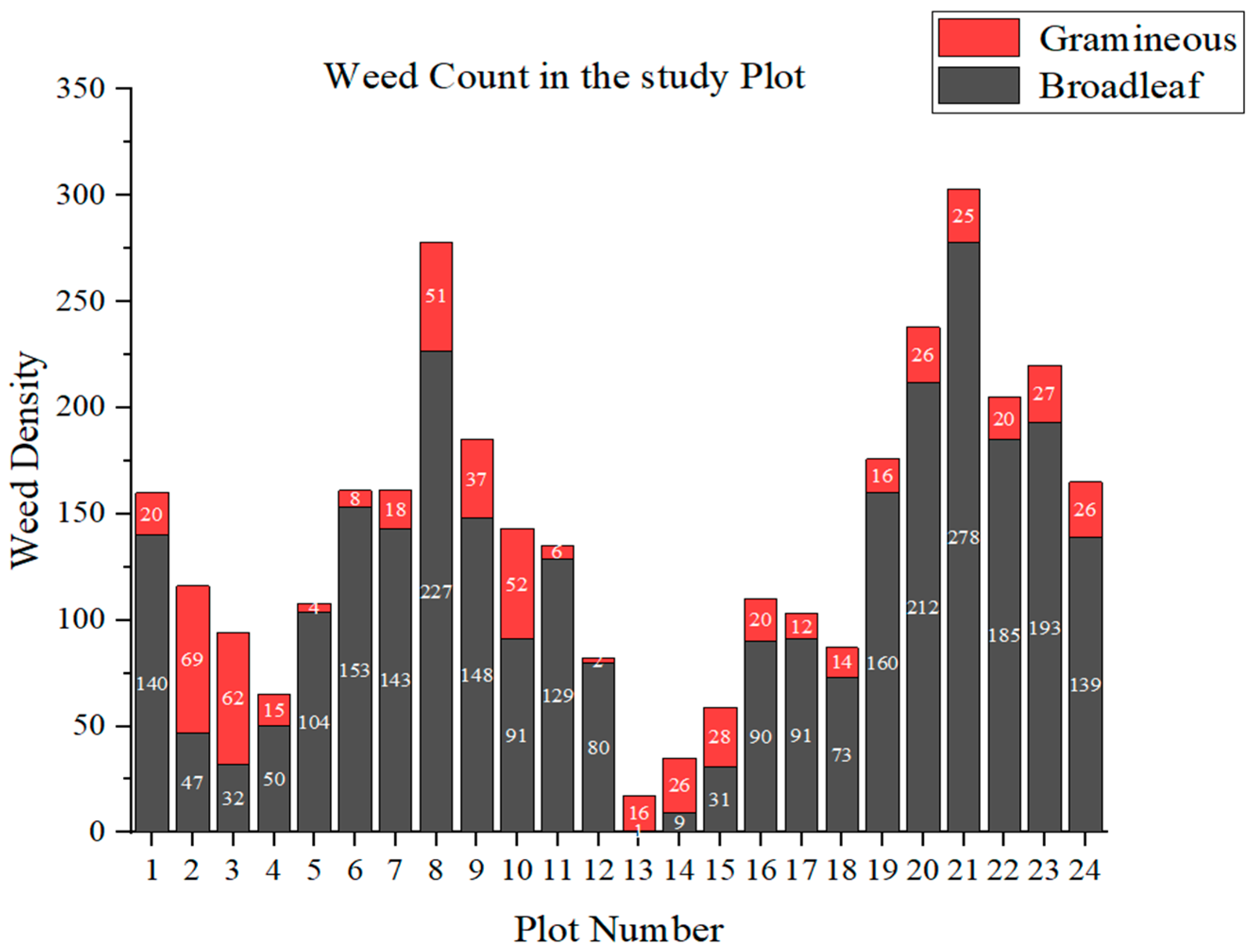

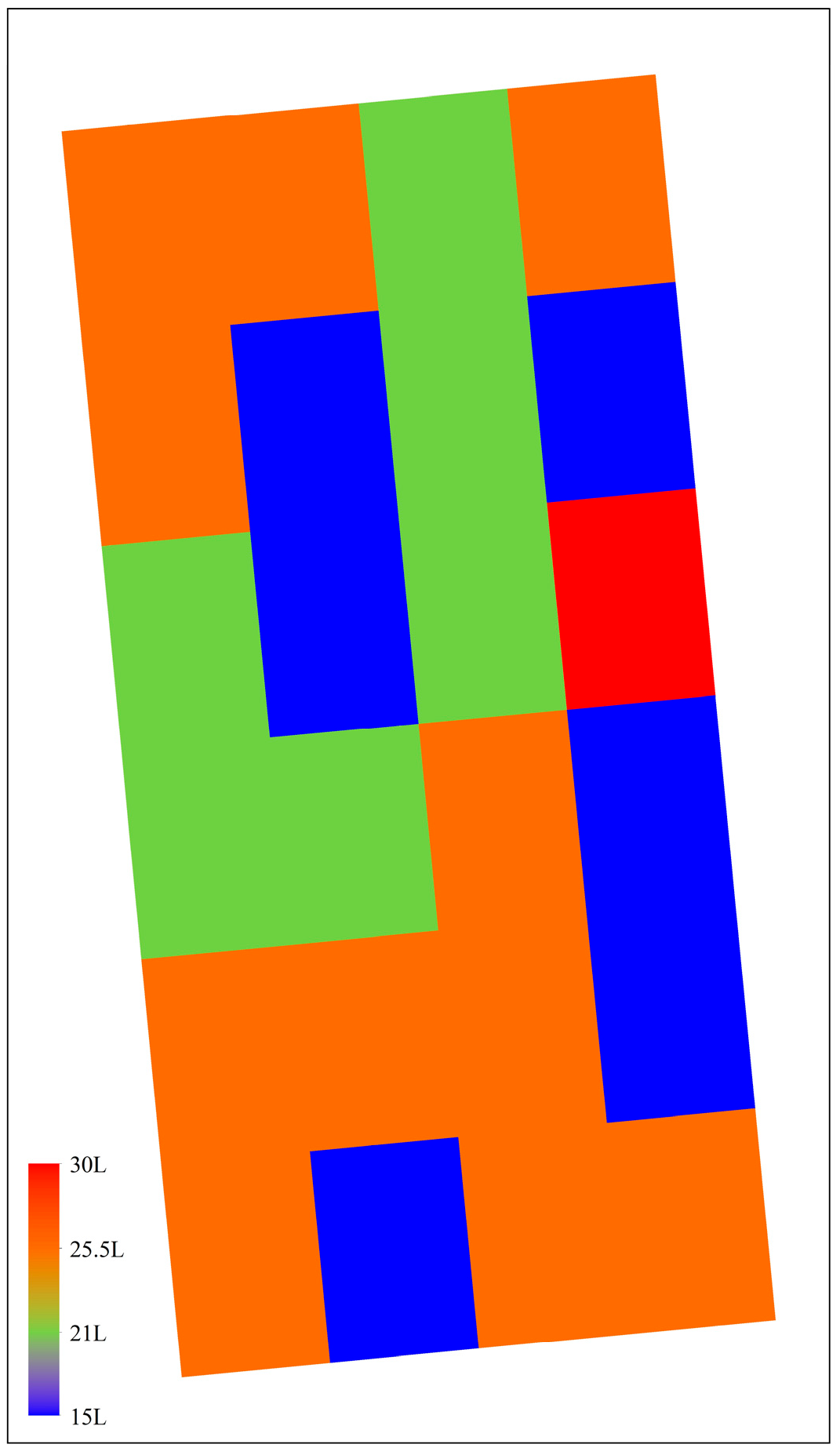

3.6. From Weed Distribution Mapping to Variable-Rate Prescription

- (1)

- Level 1 (Red Zone): Plots with more than 300 weeds received 100% of the baseline rate (30 L/mu).

- (2)

- Level 2 (Orange Zone): Plots with 200 to 300 weeds received 85% of the baseline rate (25.5 L/mu).

- (3)

- Level 3 (Yellow Zone): Plots with 100 to 200 weeds received 70% of the baseline rate (21 L/mu).

- (4)

- Level 4 (Blue Zone): Plots with fewer than 100 weeds received 50% of the baseline rate (15 L/mu).

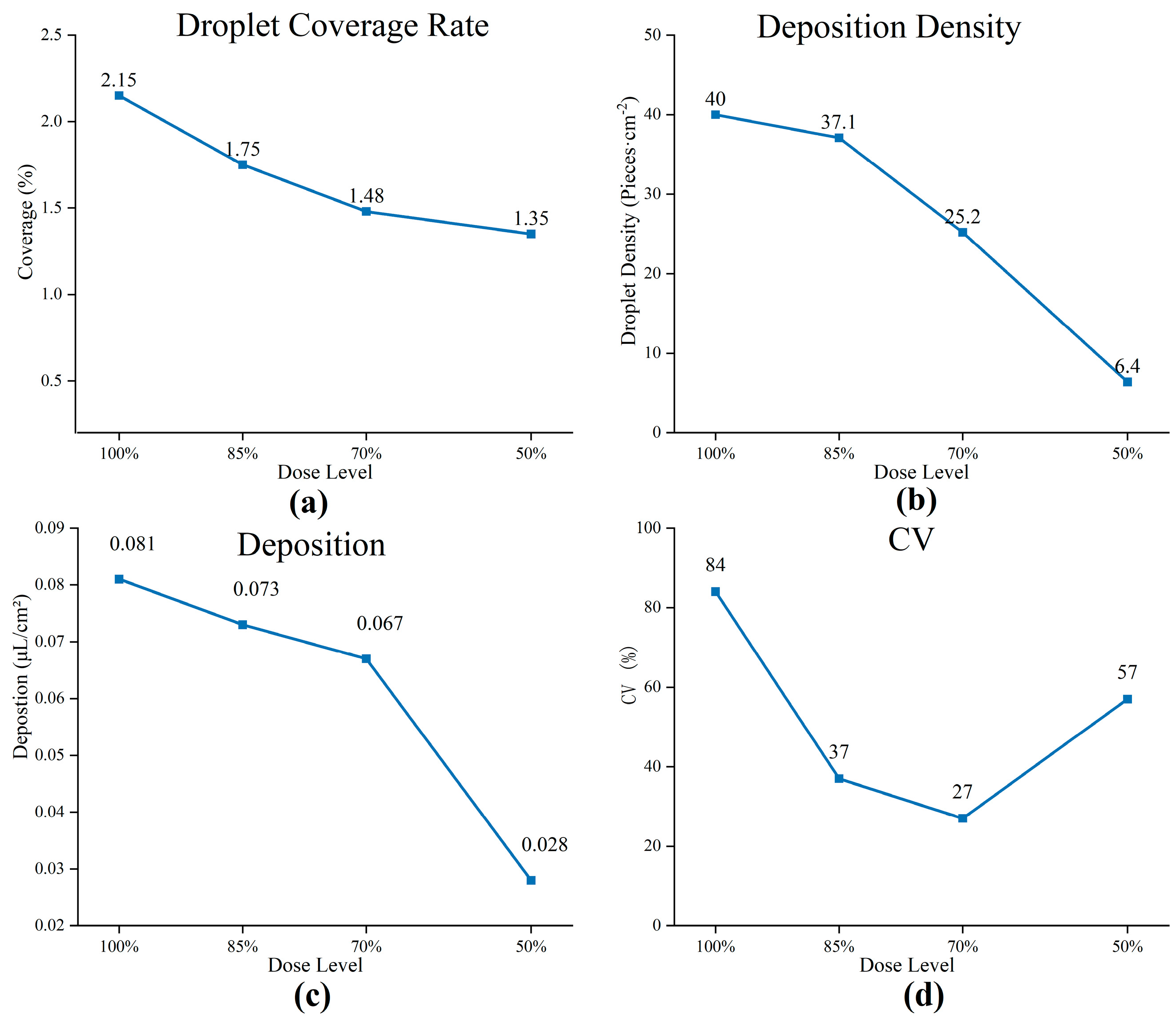

3.7. Evaluation of Spray Application Efficacy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Callo, A.; Mansouri, M. Food Security in Global Food Distribution Networks: A Systems Thinking Approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Systems Conference (SysCon), Montreal, QC, Canada, 15–18 April 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, N.; Akilan, T.; Phalke, A.R. Machine Learning for Global Food Security: A Concise Overview. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Humanitarian Technology Conference (IHTC), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2–4 December 2022; pp. 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, S.; Trollman, H.; Trollman, F.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Parra-López, C.; Duong, L.; Martindale, W.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Hdaifeh, A.; et al. The Russia-Ukraine Conflict: Its Implications for the Global Food Supply Chains. Foods 2022, 11, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Technical Programme on Scientific Prevention and Control of Weeds in Grain Crop Fields. Available online: https://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/2023cg/jszd_29356/202302/t20230220_6420966.htm (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- Yue, Y.; Zhao, A. Soybean Seedling-Stage Weed Detection and Distribution Mapping Based on Low-Altitude UAV Remote Sensing and an Improved YOLOv11n Model. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.L.; Ma, Y.; Chen, J.C. Design and Test of Fog Volume Adjustment for Variable Spray Uniformity. Chin. J. Agric. Mech. Chem. 2025, 46, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, C.; Yang, Z.; Chai, J.; Shi, Y.; Liu, J. Design of Field Real-Time Target Spraying System Based on Improved YOLOv5. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1072631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.G.; Wang, X.; Li, C.L.; Fu, H.; Yang, S.; Zhai, C.Y. Cabbage and weed identification based on machine learning and target spraying system design. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 924973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, I.; Liu, J.Z.; Faheem, M.; Noor, R.S.; Shaikh, S.A.; Solangi, K.A.; Raza, S.M. Different Sensor-Based Intelligent Spraying Systems in Agriculture. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2020, 316, 112265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jin, F.; Ji, M.; Qu, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, C. Hierarchical Dual-Model Detection Framework for Spotted Seals Using Deep Learning on UAVs. Animals 2025, 15, 3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Cao, Y.; Ao, X. A Statistical Method for High-Throughput Emergence Rate Calculation for Soybean Breeding Plots Based on Field Phenotypic Characteristics. Plant Methods 2025, 21, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, J. YOLO-CAM: A Lightweight UAV Object Detector with Combined Attention Mechanism for Small Targets. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Chen, L.; Su, T. Research on Small Object Detection in Degraded Visual Scenes: An Improved DRF-YOLO Algorithm Based on YOLOv11. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Xu, J. Enhanced Blood Cell Detection in YOLOv11n Using Gradient Accumulation and Loss Reweighting. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, P. Research on Wheat Spike Phenotype Extraction Based on YOLOv11 and Image Processing. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Wei, W.; Huang, Z.; Yan, R. Mulch-YOLO: Improved YOLOv11 for Real-Time Detection of Mulch in Seed Cotton. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.; Jiang, Z. SDO-YOLO: A Lightweight and Efficient Road Object Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLOv11. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Wen, Y. OGS-YOLOv8: Coffee Bean Maturity Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLOv8. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Hu, C.; Tan, L.; Liao, H.; Zhang, Q.; Min, F. DCNet: Full waveform inversion with difference convolution. J. Appl. Geophys. 2025, 240, 105762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Dong, L.; Qin, L. Detection of Conveyor Belt Foreign Objects in Coal Mine Underground Occlusion Scene Based on SDGW-YOLOv11. Electron. Meas. Technol. 2025, 48, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Guo, H.; Chen, X.; Li, M.; Fang, B.; Cao, Y. YOLOv8n-SSDW: A Lightweight and Accurate Model for Barnyard Grass Detection in Fields. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, L.; Zhao, L.; Shi, Y.; Wang, F.; Meng, D.; Zhao, J. Method for Lightweight Tomato Leaf Disease Recognition Based on Improved YOLOv11s. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2025, 18, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Nilupal, E.; Yilhamu, Y. Research on Transmission Line Inspection Algorithm Based on YOLOv8. Electron. Meas. Technol. 2025, 48, 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Zhou, X.; Hu, S. Research on Real-Time Obstacle Detection Algorithm for Driverless Electric Locomotive in Mines Based on RSAE-YOLOv11n. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2025, 22, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.J.; Zheng, P.; Qiao, W.W. A Method for Detecting Surface Defects on Worm Gears Based on Improved YOLOv8n. Mach. Tools Hydraul. 2025, 53, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.C.; Zhou, H.; Wu, C.J. Remote Sensing Image Target Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLOv8. Comput. Eng. Des. 2025, 46, 1856–1863. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.S.; Chen, Z.G.; Wang, Y.X. Lightweight Bearing Appearance Defect Detection Algorithm Based on SBSI-YOLOv11. J. Guangxi Norm. Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2025, 43, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tee, J.H.; Solihin, M.I.; Chong, K.S.; Tiang, S.S.; Tham, W.Y.; Ang, C.K.; Lee, Y.J.; Goh, C.L.; Lim, W.H. Advancing Intelligent Logistics: YOLO-Based Object Detection with Modified Loss Functions for X-Ray Cargo Screening. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.E.; Qiu, L.; Ding, W.B.; He, H.L.; Gao, Q.; Gao, H.S.; Li, Y.Z.; Xue, J. Effects of Plant Protection Drone Flight Parameters on Fog Droplet Deposition Distribution on Rice at Different Fertility Stages. China Plant Prot. Guide 2025, 45, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Liao, K.; Xiao, H.; Guo, K.F.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Jin, C.Z.; Ni, X.Z. Effects of Plant Protection Drone Operating Parameters on the Distribution of Fog Droplet Deposition in the Canopy of Citrus Trees. China Plant Prot. Guide 2025, 45, 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X.; Cao, Y. Weed Detection Algorithms in Rice Fields Based on Improved YOLOv10n. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, B.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, Z. GE-YOLO for Weed Detection in Rice Paddy Fields. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Cai, D.; Bai, J.; Xu, T.; Yu, F. Intelligent Rice Field Weed Control in Precision Agriculture: From Weed Recognition to Variable Rate Spraying. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year of the Dataset | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Set | 4425 | 4207 | × |

| Validation Set | 2320 | 1934 | × |

| Test Set | × | × | 116 |

| Dataset Split | Year | Gramineous Weeds | Broadleaf Weeds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Set | 2023 and 2024 | 12,569 | 11,426 |

| Validation Set | 2023 and 2024 | 5520 | 5018 |

| Test Set | 2025 | 487 | 445 |

| ODConv | SEAM | ADown | WIoU | P (%) | R (%) | Maize (%) | Gramineous Weed (%) | Broadleaf Weed (%) | Params/M | FLOPs/G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| × | × | × | × | 94.2 | 86.2 | 98.7 | 94.6 | 95.4 | 2.46 | 6.3 |

| √ | × | × | × | 94.7 | 86.8 | 99.2 | 95.1 | 95.7 | 2.89 | 5.6 |

| √ | √ | × | × | 94.9 | 88.3 | 99.4 | 97.2 | 96.4 | 2.87 | 5.7 |

| √ | √ | √ | × | 95.2 | 89.7 | 99.5 | 97.6 | 96.9 | 2.44 | 5.1 |

| √ | √ | √ | √ | 95.5 | 91.3 | 99.5 | 97.8 | 97.0 | 2.44 | 5.1 |

| Attention | P (%) | R (%) | Maize (%) | Gramineous Weed (%) | Broadleaf Weed (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBAM | 95.2 | 87.8 | 99.6 | 95.9 | 96.1 |

| GAM | 92.8 | 88.0 | 98.6 | 94.8 | 95.7 |

| EMA | 95.5 | 87.9 | 99.5 | 96.9 | 95.9 |

| SEAM | 96.0 | 89.7 | 99.5 | 97.2 | 97.2 |

| Models | P (%) | R (%) | Maize (%) | Gramineous Weed (%) | Broadleaf Weed (%) | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv11 | 94.2 | 86.2 | 98.7 | 94.6 | 95.4 | 212 |

| YOLOv11-CIoU | 95.2 | 87.8 | 99.5 | 94.9 | 95.4 | 221 |

| YOLOv11-EIoU | 92.8 | 88.0 | 98.6 | 95.6 | 95.8 | 217 |

| YOLOv11-SIoU | 95.5 | 87.9 | 99.5 | 95.2 | 95.3 | 225 |

| YOLOv11-WIoU | 96.0 | 89.7 | 99.5 | 96.1 | 95.9 | 224 |

| Model | P (%) | R (%) | Maize (%) | Gramineous Weed (%) | Broadleaf Weed (%) | Params/s | FLOPs/G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faster-RCNN | 83.5 | 73.1 | 88.3 | 81.2 | 78.3 | 332.5 | 136.9 |

| SSD | 86.2 | 75.2 | 90.1 | 86.3 | 80.6 | 264 | 32.6 |

| YOLOv3 | 98.5 | 94.0 | 97.8 | 96.4 | 96.9 | 93.89 | 261.8 |

| YOLOv5 | 89.2 | 73.5 | 92.1 | 86.3 | 88.7 | 2.08 | 5.8 |

| YOLOv6 | 87.5 | 81.0 | 96.8 | 89.8 | 89.8 | 4.03 | 11.8 |

| YOLOv7 | 88.2 | 82.1 | 96.6 | 90.1 | 90.7 | 6.01 | 12.8 |

| YOLOv8 | 94.2 | 81.0 | 95.9 | 92.2 | 93.7 | 2.56 | 6.8 |

| YOLOv9 | 92.1 | 83.0 | 97.9 | 93.5 | 95.0 | 6.02 | 22.6 |

| YOLOv10 | 96.5 | 93.0 | 88.0 | 95.3 | 95.8 | 2.57 | 8.2 |

| YOLOv11 | 93.6 | 83.9 | 98.7 | 94.9 | 95.4 | 2.46 | 5.5 |

| YOLOv12 | 91.8 | 85.7 | 97.8 | 94.2 | 95.2 | 2.43 | 6.3 |

| Ours | 95.5 | 91.3 | 99.5 | 97.8 | 97.0 | 2.44 | 5.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Guo, Z.; Zheng, W.; Cao, Y. Research on Accurate Weed Identification and a Variable Application Method in Maize Fields Based on an Improved YOLOv11n Model. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2456. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232456

Chen X, Zhang H, Liu X, Guo Z, Zheng W, Cao Y. Research on Accurate Weed Identification and a Variable Application Method in Maize Fields Based on an Improved YOLOv11n Model. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2456. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232456

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xiaoan, Hongze Zhang, Xingcheng Liu, Zhonghui Guo, Wei Zheng, and Yingli Cao. 2025. "Research on Accurate Weed Identification and a Variable Application Method in Maize Fields Based on an Improved YOLOv11n Model" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2456. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232456

APA StyleChen, X., Zhang, H., Liu, X., Guo, Z., Zheng, W., & Cao, Y. (2025). Research on Accurate Weed Identification and a Variable Application Method in Maize Fields Based on an Improved YOLOv11n Model. Agriculture, 15(23), 2456. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232456