Abstract

Hydrogen is being increasingly recognized as a promising clean, renewable energy carrier. Among the available production pathways, biological processes, particularly dark fermentation of residual biomasses and agricultural by-products, represent an appealing approach aligned with circular economy principles. These feedstocks are abundant and low cost; however, their relatively low energy density constrains process efficiency. To mitigate this limitation, research efforts have concentrated on optimizing substrate composition and implementing pre-treatment strategies to enhance hydrogen yields. Numerous studies have explored the potential of agricultural and livestock residue, yet reported outcomes are often heterogeneous in terms of units, systems, and experimental conditions, complicating direct comparison. This review consolidates current knowledge and identifies effective strategies to optimize biohydrogen generation. Among the investigated substrates, corn stover emerges as the most promising, with hydrogen yields up to 200 [mL H2/gVS (Volatile Solids)]. Evidence further suggests that inoculum processing, including enrichment or pre-treatment, can substantially improve performance, often more effectively than substrate processing alone. When both inoculum and substrate are treated, hydrogen yields may increase up to fourfold relative to untreated systems. Overall, integrating suitable feedstocks with targeted processing strategies is crucial to advancing sustainable biohydrogen production.

1. Introduction

Hydrogen has been explored as an alternative to fossil fuels, as its use for energy production does not result in pollutant emissions because only heat and water vapour are produced [1]. The two most common approaches for producing hydrogen are steam methane reforming and electrolysis. However, hydrogen can also be produced biologically through biophotolysis (direct and indirect), photo fermentation, and dark fermentation, or by a combination of these processes [2].

Dark fermentation is the preferred biological method for hydrogen production due to its higher yield and lower operational cost [3,4,5]. The available literature on dark fermentation reveals the absence of a standardized methodology for conducting biohydrogen potential tests, leading to extreme variability in both experimental conditions and the measurement of process parameters. Furthermore, the scientific community has tested a wide range of possible inoculum and substrate processing techniques to enhance hydrogen yield (HY).

The development of profitable and environmentally sustainable bioenergy production must be based on the use of waste biomass to reduce costs, generate additional value, and advance toward next-generation biofuels, particularly biomethane [6,7]. The use of these biomasses, and, in particular, of agricultural and livestock by-products, does not conflict with food production, and allows for the exploitation of products that would otherwise have to be disposed of as waste, thus incurring additional costs. However, it is important to consider that by-products generally have a lower energy content and are widely dispersed, which requires evaluating whether the cost of collection allows for a net gain from energy production.

Several types of agricultural by-products can be used for energy production: straw [8], grass [9], pruning residues [10], and livestock manure [11,12]. According to Italian legislation, both agricultural and livestock by-products are raw materials suitable for producing advanced biofuels [13]. The main drawback of these feedstocks is their high lignocellulosic content. In fact, lignocellulosic biomass has a complex structure, requiring a pre-treatment before the fermentation process to increase the number of monomeric sugars needed for hydrogen-producing microorganisms [14].

Pre-treatment technologies employed in dark fermentation are generally classified into substrate and inoculum pre-treatments. While substrate pre-treatments aim to enhance HY by promoting the hydrolysis of complex organic matter and increasing the availability of biodegradable nutrients, inoculum pre-treatments focus on enriching hydrogen-producing microorganisms by suppressing hydrogen-consuming species, such as methanogens, through physical, chemical, or thermal methods. This selective inhibition improves the overall efficiency of biological hydrogen production [3].

The present review aims to frame the current trends in hydrogen production from the most abundant agricultural and livestock by-products in Europe, namely agricultural bioresources of barley, beet, corn, oat, rapeseed, sorghum, sunflower, wheat crops, and livestock by-products from cattle, poultry, and swine farms. The discussion examines the effects of substrate and inoculum processing, along with nutrient supplementation, on HY, with the following objectives:

- To elucidate differences and inconsistencies across studies, highlighting that the absence of standardized protocols for biohydrogen experiments hampers comparability and reproducibility;

- To identify the substrate most likely to achieve the highest HY with minimal variability;

- To determine the key variables and pre-treatments that exert a decisive influence on hydrogen production, as well as the most prominent synergistic interactions among them.

2. Materials and Methods

The first step of the review was to create an inventory of scientific articles suitable for data extraction and subsequent analysis.

The systematic review was conducted in accordance with the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) guidelines [15]. To be included in the inventory, articles had to meet the following criteria: scientific papers with experimental data on hydrogen production through dark fermentation, and substrates considered for dark fermentation tests were included among the research’s target substrates.

In particular, the target substrates of the research were defined consistently, with the most common agricultural and livestock bioresources available in Europe [16,17,18], namely agricultural harvesting by-products (especially for barley, beet, corn, oat, rapeseed, sorghum, sunflower, and wheat crops) and livestock manure from cattle, poultry, and swine farms. Those by-products are also included in the list of raw materials suitable for producing advanced biofuel, according to Italian legislation [13].

Regarding HY, a fixed unit of measurement was set to enable comparison of HY values coming from different sources [mL H2/gVS].

Once the above-stated criteria were established, the Scopus and Web of Science platforms were used to review the literature.

The identification of relevant documents was performed by searching for combinations of terms within the Titles, Abstracts, or Keywords using the operators ‘AND’, ‘OR’, and word proximity (‘W’), structured according to the following two categories:

- Keywords on the process of interest: “dark fermentation” OR “dark-fermentation” OR ((hydrogen) W/15 (production OR yield OR potential)).

- Keywords on the substrate or feedstock: by-product OR byproduct * OR cornstalk OR livestock OR manure OR slurry OR dung OR cattle OR cow OR poultry OR swine OR chicken OR pig OR corn OR straw OR stover OR rapeseed OR sunflower OR beet OR oat OR wheat OR barley OR sorghum OR agriculture *.

The search resulted in 5356 documents. The following filters were applied: document type (article), publication year (2004–2024), and language (English). These articles were analyzed individually, and only those relevant to the review were selected. A two-stage screening procedure was used to assess the relevance of the selected articles.

In the first step, the identified articles underwent a preliminary screening based on their title and abstract. At this stage, a total of 475 articles were identified and selected from the initial pool of 5356.

In the second step, the articles underwent a detailed full-text examination to identify the studies suitable for data extraction.

The following inclusion criteria were applied: HY, expressed in [mL H2/gVS], reported as cumulative hydrogen production for batch tests or as steady-state hydrogen production for continuous experiments. Studies that did not report HY in these units were included only if the original data could be reliably converted without ambiguity. In this second screening, 69 papers out of the previous 475 were selected. Figure 1 summarizes the sequential process used for the literature selection.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the methodology used in the systematic review, developed according to the PRISMA checklist [15].

Papers identified within the literature screening were then subjected to a data extraction procedure. In line with the systematic review’s goal, HY has been selected as the primary output parameter to be collected during data extraction. HY was collected in [mL H2/gVS], and where no HY was reported or when the value was not easily convertible to the selected unit, the paper was not included in the pool.

In addition to HY, other information regarding inoculum and substrate processing, general aspects, and experimental conditions was collected.

Table 1 summarizes all of the variables selected for extraction and provides details on the unit of measurement for the quantitative variables or the alternatives that could arise for the qualitative variables.

Table 1.

Variables extracted during research analysis.

The data analysis phase aimed to identify current trends in hydrogen production through dark fermentation. For this goal, data regarding the general aspects and experimental conditions were elaborated. Additionally, this data provided a range for the achievable HY and an indication of its variability for the target substrates. This range can be achieved by constructing boxplots using the minimum and maximum values reached for each feedstock category, as well as the median, average, and first and third quartiles.

Finally, we describe how inoculum processing, substrate pre-treatment, and the addition of supplements or nutrients affect HY. The influence was evaluated by the analysis of graphical representations. These graphical representations show HYs in relation to both the type of substrate and the different options used by the data categories mentioned above (inoculum processing, substrate treatment, and supplement or nutrient addition).

3. Results

3.1. General Trends

The annual number of publications shows a fluctuating trend, with a significant peak in 2014 and two other peaks in 2011 and 2020 (Figure 2). The orange curve in Figure 2 displays the cumulative number of papers published from 2004 to 2024.

Figure 2.

Distribution of publications by year focusing on studies of dark fermentation processes.

Substrate distribution along the 69 papers is represented in Figure 3. From these studies, a total of 73 substrate records were collected, as four papers examined more than one substrate [19,20,21,22]. Figure 3 clearly shows that specific substrates have been studied much more extensively than others. Corn and wheat residues, along with cattle and swine effluents, are the most researched feedstocks. Few studies have investigated sorghum harvesting [23,24], poultry manure [25,26], cattle wastewater [27], wheat stalk [28], beet residues [29], and only a single study has examined the use of rapeseed harvesting [30].

Figure 3.

Distribution of substrates reported in the selected papers on dark fermentation.

The inoculum used in the 69 analyzed papers is shown in Figure 4; some papers used more than one inoculum. In nearly half of the studies analyzed, the inoculum was collected from already-functioning treatment plants.

Figure 4.

Inoculum origin in dark fermentation studies.

Anaerobic digestion sludge was the most used inoculum, accounting for 42% of total cases. The use of sludge from the digester or treatment ponds makes the system more efficient and better adapted due to similar conditions in the reactor [31,32]. In 19% of the cases, the inoculum was taken from animal effluents, either composted or not. About 7% of the inoculum came from other environmental sectors, such as soil, wood, lake, and river sectors. Nearly 6% of the considered studies used a pure culture as inoculum, whose origin was not specified. Only 3% of the researchers used rumen fluid. Lastly, in 18% of the works, the natural microflora already present in the substrate was used, and no further inoculum was added. In several studies, the inoculum was further treated and refined.

3.2. Process Parameters

The performance and outcomes of dark fermentation experiments are strongly influenced by the process parameters. This section outlines the main parameters used in the reviewed studies, emphasizing how different operational modes impact hydrogen production efficiency.

One of the key elements of the experiments is the reactor; most of the studies, up to 92%, used batch reactors during the experiments. Another 6% used semi-continuous reactors, and just 2% used continuous reactors [33].

No standardized procedure currently exists for conducting hydrogen potential tests, but a very similar procedure to calculate the methane potential through anaerobic digestion requires the use of batch reactors. Some authors state that batch mode improves substrate degradation efficiency and biohydrogen production by 25% compared to continuous mode [34]. Conversely, other authors sustain that the fed-batch mode can reduce the accumulation of soluble metabolite intermediates during acidogenic fermentation because of the fill–draw operation [35]. At the same time, real digesters are more likely to be operated in continuous or semi-continuous modes, making them more indicative for subsequent scale-up.

Continuous and semi-continuous reactors are generally operated at larger volumes. Almost 60% of the research used reactors smaller than 0.5 [1], and only 6% of the cases involved a reactor volume between 5 and 10 [1,36,37,38,39].

A complete overview of the considerations regarding the parameters used to set and to control dark fermentation tests is presented in Table 2. Most of the variables are characterized by significant heterogeneity. Reliable conclusions are difficult to draw when comparing different studies due to the high variability of operating conditions. The core of the discussion has focused on hydrogen production, considering as the main variables the substrate and the inoculum processing, and the nutrient addition. The results may provide recommendations for future research and guidelines for standardizing the biohydrogen potential test, as has already been performed for methane [40].

Table 2.

Overview of non-homogeneous experimental parameters identified in the reviewed studies on dark fermentation.

3.3. Hydrogen Yield Distribution

This section covers the analysis of HY distribution among different feedstock categories.

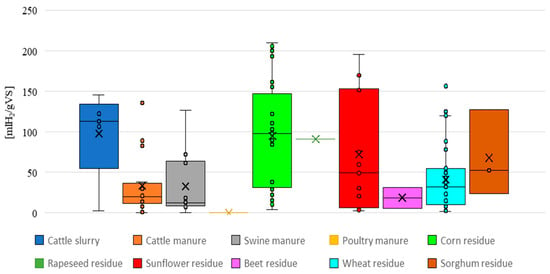

This review evaluated and compared over 130 HYs using boxplot analysis. The “boxplot” is a statistical technique used to summarize and compare groups of data visually. Boxplots use the median, approximate quartiles, and the lowest and highest data points to convey the level, spread, and symmetry of a distribution of data values [51].

In Figure 5, the boxes are enclosed by the first and the third quartiles. The line dividing each box is the second quartile or median, while the cross represents the average value. For boxes in which the minimum and maximum values do not coincide with the first and third quartiles, whiskers start from the edges of the boxes and extend up to the minimum and maximum values. From Figure 5, it is evident that some values are not covered by either the box or the whiskers. Those values are the “outliers”, that is, numbers more than 1.5 times the length of the box away from the lower or upper quartile.

Figure 5.

Boxplot analysis of hydrogen yield [mL/gVS] from dark fermentation across different substrate categories.

At first glance, the HY data appear heterogeneous. For each feedstock category, a different amount of HY values were extracted, and some categories lack enough data to make reliable conclusions (e.g., sorghum, beet, rapeseed residues, and poultry manure).

Furthermore, two categories, namely cattle manure and wheat straw, present outliers. These values may not be suitable for comparison. Corn and wheat residues are the two categories characterized by the highest amount of data.

Regarding the corn boxplot, it is possible to observe that 50% of the data, enclosed by the first and the third quartile, have HY values ranging from 27 to 130 [mL H2/gVS], with the median close to 100 [mL H2/gVS]. Moreover, corn straw shows the highest hydrogen values registered among all the feedstock categories [52]. From the boxplot, corn appears as the most appealing feedstock among agricultural residues.

Regarding sunflower residues, it is challenging to make conclusions, since the box between the first and third quartile is very wide: 50% of the HY values lie in a range between 6 and 153 [mL H2/gVS], with the median being 50 [mL H2/gVS].

Concerning the livestock by-products, cattle slurry appears to perform the best. For this category, the box is enclosed between HY values of 54 and 133 [mL H2/gVS]. Regardless, this boxplot is based on a lower amount of data compared to corn, and therefore the results may not be representative of all situations.

On the other hand, wheat straw, as well as cattle manure and swine slurry, presents a narrower range, placed toward lower HY values compared to corn, sunflower residues, and cattle slurry. This indicates an overall lower yield registered for the aforementioned feedstocks.

Figure 5 provides an initial insight into the collected data; however, it is not easy to define which is the most performing and least variable substrate, due to the high variability between experimental conditions. In any case, cattle slurry and corn harvesting residues seem to be the most promising zootechnical and agricultural residues, respectively.

3.4. Influence of Inoculum Enrichment and Nutrient Addition on Hydrogen Yield

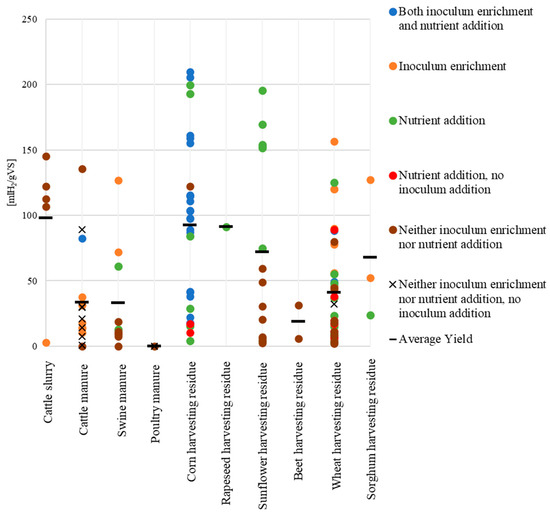

Inoculum enrichment involves selecting a specific bacterium through strain isolation, adding nutrients or optimal substrates, and employing incubation/cultivation strategies. During this process, nutrients are typically supplied alongside an appealing substrate to encourage the growth of hydrogen-producing bacteria. In this method, specific strains may be selected, and several incubation steps may be performed consecutively.

The effect of nutrient addition during the incubation/enrichment could be compared to the effect of adding nutrients directly during the dark fermentation process. Therefore, the synergistic effect of nutrient addition and/or incubation/enrichment was also evaluated.

In Figure 6, the synergistic effect of inoculum enrichment (performed prior to the dark fermentation process) and nutrient supplementation (applied during the process) was evaluated. To enhance clarity, data are grouped by substrate type, with each symbol representing a specific treatment and black bars indicating average hydrogen yields. In general, the lowest HY values are observed when neither inoculum enrichment nor nutrient addition is applied. However, the presence of one or both treatments does not necessarily guarantee high performance.

Figure 6.

Hydrogen yields in dark fermentation under different inoculum enrichment and nutrient addition treatments.

Higher HYs were consistently observed when inoculum enrichment and/or nutrient supplementation were applied. The combination of inoculum enrichment and nutrient addition proved to be particularly effective, resulting in an average HY of nearly 100 [mL H2/gVS] (calculated across all substrates treated with both enrichment and nutrient supplementation). In contrast, when the inoculum was not enriched, nutrient addition alone did not yield average HY values (calculated across all substrates treated with nutrient addition in the absence of inoculum) higher than 50 [mL H2/gVS].

3.5. Influence of Inoculum and Substrate Pre-Treatment on Hydrogen Yield

Inoculum pre-treatment focuses on selecting and enriching hydrogen-producing microorganisms while suppressing hydrogen-consuming species, such as methanogens, through acid, alkali, thermal, ultrasonic, and aerobic treatments.

Figure 7 illustrates the HY across different substrates under various inoculum pre-treatment conditions.

Figure 7.

Hydrogen yield according to inoculum pre-treatment.

Several studies employ pre-treatment of the inoculum, with thermal pre-treatment being the most common method. On average, the highest HY values are associated with pre-treated inoculum; however, considering sunflower residue data, it is clear that pre-treatment alone cannot guarantee the best performance.

Thermal pre-treatment, or heat shock, is the most widely used method for inhibiting hydrogen-consuming microorganisms [3].

This study also highlights that thermal pre-treatment is not effective over the long term; consequently, the treatment must be repeated throughout to keep hydrogen-consuming bacteria inactivated. However, no pre-treatment method can permanently suppress these populations. As a result, the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of repeating pre-treatment during the process need careful assessment.

Generally, optimum inoculum pre-treatment conditions vary among different inoculum types. Furthermore, the effectiveness of pre-treatment is influenced by the substrate and incubation temperature [3]. The strong reliance of HY on these factors—substrate type, inoculum origin, and temperature—explains the significant variability seen in the results (Figure 7).

It is also important to note that severe pre-treatment conditions, particularly high-temperature heat shocks or strong acid shocks, can harm the viability of hydrogen-producing bacteria, potentially leading to lower HY [53].

On the other hand, substrate pre-treatments are designed to enhance the availability of biodegradable nutrients and promote the hydrolysis of complex organic matter, thereby improving HY. Various methodologies have been applied for substrate pre-treatment, which appears to be more effective on agricultural residues than on zootechnical effluents.

The best pre-treatment method for each substrate should be identified based on the HY, the costs associated, the energy requirements, and the sustainability of the process [3]. Unfortunately, comparative analysis between different studies is unreliable due to varying inoculum and operating conditions. Even if conditions were identical, it would be hard to assess which is the most advantageous method. Each approach has its own drawbacks, and the overall choice depends on many factors. High temperatures associated with thermal pre-treatment or microwave irradiation may lead to the formation of inhibitory compounds; furthermore, these methods are highly energy intensive, and the associated costs may be unfavourable.

Acids may result in the corrosion of the reactor. Furthermore, like alkali substances, acids may lead to the formation of inhibitory compounds. Biological treatments are considered the cheapest alternative, but long pre-treatment times may be involved, thus hindering commercial implementation.

Despite the many drawbacks, the effectiveness of substrate pre-treatment is confirmed by elaboration below.

To determine which pre-treatment performs best, only 10 [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63] papers out of the initial 69 were selected [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. The ten chosen papers present more than one value for the HY as the substrate pre-treatment method varies. Please note that, for these papers, the substrate pre-treatment method was the only variable to change. All of the other variables were kept constant, as data were extracted from the same source.

For each of the ten papers, the HY values obtained through substrate pre-treatments were divided by the HY value of the raw substrate to indicate the potential improvement. This ratio, named r, is described by Equation (1):

where

i = corresponds to the ten analyzed papers;

x = represents the n pre-treating methods performed in each i-th paper;

HY(xi) = is the yield obtained with the x-th pre-treatment method in the i-th paper;

HYi = is the yield obtained without pre-treating the substrate in each i-th paper.

Therefore, a value of r equal to “1” indicates either the absence of pre-treatment or no improvement in HY.

Figure 8 reports the dimensionless ratio (r) values, defined in Equation (1), for various pre-treatment methods gathered from ten selected papers. The y-axis represents the r values, while the x-axis lists the ten selected papers. The r coefficient values reflect the relative improvement in HY compared to the untreated substrate. As shown in Figure 8, the application of multiple-combined pre-treatment strategies appears to be the most effective approach for enhancing HY. Noteworthy results for agricultural feedstocks are achieved also by chemical pre-treatment (acid/alkali). Thermal treatment suppresses the naturally occurring methanogenic microflora while simultaneously promoting the growth of hydrogen-producing bacteria.

Figure 8.

Ratio between the hydrogen yield of the pre-treated substrate and the hydrogen yield of the untreated substrate “r”; results expressed according to the substrate kind and the study of provenance [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63].

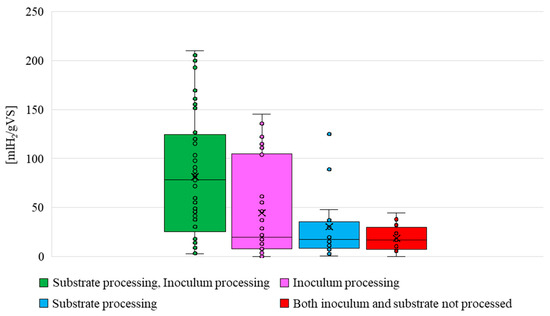

Figure 9 highlights the possible synergies between substrate and inoculum processing. Data are presented with boxplot to illustrate data distribution and variability. To build a boxplot, inoculum enrichment and inoculum pre-treatment were both considered as “inoculum processing” actions, whether only one or both are performed.

Figure 9.

HY values obtained from dark fermentation under different conditions, highlighting the effects of substrate and/or inoculum pre-treatment.

When both inoculum and substrate are treated, hydrogen production increases to higher values. Lower values are registered for just the inoculum or just the substrate processing. Furthermore, the diagrams suggest that inoculum processing is more effective than substrate processing in increasing the HY.

Even if inoculum processing data are quite scattered, the average value was around 44.5 [mL H2/gVS], which is higher than the average value obtained for substrate processing 32 [mL H2/gVS]. On the other hand, an average value of 81.4 [mL H2/gVS] was registered when both the treatments were performed, which is more than four times higher than the average value obtained when no processing actions were carried out.

4. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to assess the potential for producing hydrogen from agricultural and livestock by-products. The most significant challenge encountered during data analysis was the extreme heterogeneity among the studies. Differences in methodologies, measurement units, and experimental settings complicated the process of grouping results and making direct comparisons.

While the adopted search strategy ensured a focused and coherent dataset, it may have excluded studies on hydrogen yields that did not explicitly reference ‘dark fermentation’ or ‘hydrogen production’ in their title, abstract, or keywords. Nevertheless, the body of literature included in this review provides a comprehensive and representative overview of the current state of research, yielding valuable insights into the topic under investigation.

Many valuable studies were excluded from the review due to the incompatibility of units used to express HY. Significant heterogeneity was also observed in the inoculum and substrate pre-treatment methods. For a given treatment, the instruments and reagents used, as well as the execution of the procedure itself, can differ substantially.

Enzymatic treatment offers a clear example, as it can be applied either before or during the fermentation process. Chemical pre-treatments are similarly critical: some studies use the liquid fraction of the pre-treatment for fermentation, others use the solid fraction, and some use the entire mixture. The duration of the experiments also varied widely, ranging from a few hours to several days.

Additional inconsistencies were observed across studies. Some authors did not report results under standardized conditions (temperature and pressure). In certain cases, it was unclear whether the inoculum’s contribution to HY was subtracted to determine the potential of the raw material alone. Lastly, some studies did not specify whether the volatile solids used to express HY referred to the substrate before or after pre-treatment.

The lack of standardized protocols for conducting dark fermentation experiments poses a significant challenge to the interpretation and comparison of results. Moreover, terminological inconsistencies further hinder clarity, as identical terms are often used to describe different processes, while different terms may refer to the same concept. To promote consistency, comparability, and reproducibility across studies, it is important to develop a unified experimental framework supported by clear and shared terminology.

Data on HY were unevenly distributed across feedstocks. While some substrates were well represented, others lacked sufficient data for reliable statistical analysis.

Among agricultural residues, corn stover stands out as the substrate with the highest potential for hydrogen production, while cattle slurry appears to be the most promising livestock by-product.

The dark fermentation process is heavily influenced by both substrate and inoculum treatments. Combining these treatments maximizes hydrogen production, resulting in significantly higher yields than using either treatment alone. While substrate pre-treatment can boost hydrogen production by up to 50%, inoculum processing generally proves to be even more effective in enhancing overall yields.

Notably, multiple combined pre-treatments on the substrate show the most significant improvements, whereas among single treatments, chemical pre-treatment of agricultural residues yield particularly favourable results.

Finally, this review does not address the economic feasibility of the various dark fermentation strategies. Most studies were conducted on a laboratory scale, and some complex procedures may not be viable on an industrial scale. Future research should focus on scalability and cost-effectiveness to support the practical implementation of biohydrogen production technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S., A.P., G.F. and M.C.L.; methodology, F.I., R.S., A.P., G.F. and M.C.L.; software, F.I. and R.S.; validation, A.P., F.M. and M.C.L.; formal analysis, F.I., R.S. and G.F.; investigation, F.I., R.S., A.P. and G.F.; resources, F.M. and M.C.L.; data curation, F.I., R.S. and M.C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, F.I., R.S., A.P., G.F. and M.C.L.; writing—review and editing, F.M. and M.G.; visualization, F.M. and M.G.; supervision, A.P. and M.C.L.; project administration, F.M. and M.C.L.; funding acquisition, F.M. and M.C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funded by the European Union (Grant Agreement number: 101118296). The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) only, and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union; the European Union cannot be held responsible for them. Supported by the Interdepartmental Centre for Energy Economics and Technology “Giorgio Levi Cases”, University of Padova, Italy, under the interdisciplinary project VASE (Valorisation of Agri-food Wastes for Sustainable Energy Production).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Megía, P.J.; Vizcaíno, A.J.; Calles, J.A.; Carrero, A. Hydrogen Production Technologies: From Fossil Fuels toward Renewable Sources. A Mini Review. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 16403–16415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manish, S.; Banerjee, R. Comparison of Biohydrogen Production Processes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieenia, R.; Lavagnolo, M.C.; Pivato, A. Pre-Treatment Technologies for Dark Fermentative Hydrogen Production: Current Advances and Future Directions. Waste Manag. 2018, 71, 734–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallenbeck, P.C.; Abo-Hashesh, M.; Ghosh, D. Strategies for Improving Biological Hydrogen Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 110, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathews, J.; Wang, G. Metabolic Pathway Engineering for Enhanced Biohydrogen Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 7404–7416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statuto, D.; Frederiksen, P.; Picuno, P. Valorization of Agricultural By-Products Within the “Energyscapes”: Renewable Energy as Driving Force in Modeling Rural Landscape. Nat. Resour. Res. 2019, 28, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, G.; Holl, E.; Steinbrenner, J.; Pezzuolo, A.; Lemmer, A. Environmental Assessment of a Two-Stage High Pressure Anaerobic Digestion Process and Biological Upgrading as Alternative Processes for Biomethane Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 360, 127612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosowski, A.; Bill, R.; Thrän, D. Temporal and Spatial Availability of Cereal Straw in Germany Case Study: Biomethane for the Transport Sector. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2020, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, A.; Boscaro, D.; Dalla Venezia, F.; Correale Santacroce, F.; Pezzuolo, A.; Sartori, L.; Bolzonella, D. Biogas from Residual Grass: A Territorial Approach for Sustainable Bioenergy Production. Waste Biomass Valorization 2017, 8, 2747–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pari, L.; Suardi, A.; Santangelo, E.; García-Galindo, D.; Scarfone, A.; Alfano, V. Current and Innovative Technologies for Pruning Harvesting: A Review. Biomass Bioenergy 2017, 107, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finzi, A.; Mattachini, G.; Lovarelli, D.; Riva, E.; Provolo, G. Technical, Economic, and Environmental Assessment of a Collective Integrated Treatment System for Energy Recovery and Nutrient Removal from Livestock Manure. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Ferrari, G.; Pezzuolo, A.; Alengebawy, A.; Jin, K.; Yang, G.; Li, Q.; Ai, P. Evaluation and Analysis of Biogas Potential from Agricultural Waste in Hubei Province, China. Agric. Syst. 2023, 205, 103577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decreto Interministeriale 2 Marzo 2018—Promozione Dell’uso Del Biometano Nel Settore Dei Trasporti. Available online: https://www.mimit.gov.it/index.php/it/normativa/decreti-interministeriali/decreto-interministeriale-2-marzo-2018-promozione-dell-uso-del-biometano-nel-settore-dei-trasporti (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Soares, J.F.; Confortin, T.C.; Todero, I.; Mayer, F.D.; Mazutti, M.A. Dark Fermentative Biohydrogen Production from Lignocellulosic Biomass: Technological Challenges and Future Prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 117, 109484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA Statement. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Scarlat, N.; Martinov, M.; Dallemand, J.-F. Assessment of the Availability of Agricultural Crop Residues in the European Union: Potential and Limitations for Bioenergy Use. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 1889–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agricultural Production—Crops—Statistics Explained—Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Agricultural_production_-_crops (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Scarlat, N.; Fahl, F.; Dallemand, J.-F.; Monforti, F.; Motola, V. A Spatial Analysis of Biogas Potential from Manure in Europe. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 915–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskicioglu, C.; Monlau, F.; Barakat, A.; Ferrer, I.; Kaparaju, P.; Trably, E.; Carrère, H. Assessment of Hydrothermal Pretreatment of Various Lignocellulosic Biomass with CO2 Catalyst for Enhanced Methane and Hydrogen Production. Water Res. 2017, 120, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, G.; Rákhely, G.; Kovács, K.L. Thermophilic Biohydrogen Production from Energy Plants by Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus and Comparison with Related Studies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 3659–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rangel, M.; Barboza-Corona, J.E.; Buitrón, G.; Valdez-Vazquez, I. Essential Nutrients for Improving the Direct Processing of Raw Lignocellulosic Substrates Through the Dark Fermentation Process. Bioenergy Res. 2020, 13, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, C.Y.; Yin, L.L.; Li, W.Z.; Wang, Z.J.; Luo, L.N. Optimization of Hydrogen Production from Agricultural Wastes Using Mixture Design. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2017, 10, 246–254. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Li, W.; Li, C.; Xu, G. Enhanced Biogas Production from Sorghum Stem by Co-Digestion with Cow Manure. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 9153–9158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.-X.; Song, H.-C.; Wang, C.-R.; Tang, R.-S.; Huang, Z.-X.; Gao, T.-R.; Xie, J. Enhanced Bio-Hydrogen Production from Sweet Sorghum Stalk with Alkalization Pretreatment by Mixed Anaerobic Cultures. Int. J. Energy Res. 2009, 34, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Wu, N.; Wei, Y.; Shan, H.; Zhao, H. Co-Production of Biohydrogen and Biomethane from Chicken Manure and Food Waste in a Two-Stage Anaerobic Fermentation Process. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 3706–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan Yusof, T.R.; Abdul Rahman, N.; Ariff, A.; Che Man, H. Evaluation of Hydrogen and Methane Production from Co-Digestion of Chicken Manure and Food Waste. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2019, 28, 3003–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Tang, G.L.; Huang, J.; Sun, Z.J.; Tang, Q.Q.; Yan, C.H.; Liu, G.Q. Biohydrogen Production from Cattle Wastewater by Enriched Anaerobic Mixed Consortia: Influence of Fermentation Temperature and pH. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2008, 106, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Yuan, X.; Shi, X. Bioconversion of Wheat Stalk to Hydrogen by Dark Fermentation: Effect of Different Mixed Microflora on Hydrogen Yield and Cellulose Solubilisation. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 3805–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cieciura-Włoch, W.; Borowski, S. Biohydrogen production from wastes of plant and animal origin via dark fermentation. J. Environ. Eng. Landsc. Manag. 2019, 27, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Talebnia, F.; Karakashev, D.; Xie, L.; Zhou, Q.; Angelidaki, I. Enhanced Bioenergy Recovery from Rapeseed Plant in a Biorefinery Concept. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 1433–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremonez, P.A.; Teleken, J.G.; Weiser Meier, T.R.; Alves, H.J. Two-Stage Anaerobic Digestion in Agroindustrial Waste Treatment: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 281, 111854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeihanipour, A.; Niklasson, C.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Enhancement of Solubilization Rate of Cellulose in Anaerobic Digestion and Its Drawbacks. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 1509–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongjan, P.; Sompong, O.; Angelidaki, I. Performance and Microbial Community Analysis of Two-Stage Process with Extreme Thermophilic Hydrogen and Thermophilic Methane Production from Hydrolysate in UASB Reactors. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 4028–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagelqvist, A. Batchwise Mesophilic Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Secondary Sludge from Pulp and Paper Industry and Municipal Sewage Sludge. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 820–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawoof, S.A.A.; Kumar, P.S.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Subramanian, S. Sequential Production of Hydrogen and Methane by Anaerobic Digestion of Organic Wastes: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1043–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-C.; Dai, Y.; Bai, Y.-X.; Li, Y.-H.; Fan, Y.-T.; Hou, H.-W. Co-Producing Hydrogen and Methane from Higher-Concentration of Corn Stalk by Combining Hydrogen Fermentation and Anaerobic Digestion. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 14204–14211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Jiao, C.; He, W.; Yan, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Li, Z.; Guo, Y.; Liu, X. Comparison of Micro-Aerobic and Anaerobic Fermentative Hydrogen Production from Corn Straw. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 5456–5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.; Rodríguez, M. Hydrogen Production by Anaerobic Digestion of Pig Manure: Effect of Operating Conditions. Renew. Energy 2013, 53, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, S.R.; Chaganti, S.R.; Lalman, J.A.; Heath, D. Using a Statistical Approach to Model Hydrogen Production from a Steam Exploded Corn Stalk Hydrolysate Fed to Mixed Anaerobic Cultures in an ASBR. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 10003–10015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNI/TS 11703:2018—UNI Ente Italiano Di Normazione. Available online: https://store.uni.com/uni-ts-11703-2018 (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Xing, Y.; Li, Z.; Fan, Y.; Hou, H. Biohydrogen Production from Dairy Manures with Acidification Pretreatment by Anaerobic Fermentation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2010, 17, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrellos, G.; Lyberatos, G.; Antonopoulou, G. Does Acid Addition Improve Liquid Hot Water Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass towards Biohydrogen and Biogas Production? Sustainability 2020, 12, 8935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilroyed, B.H.; Li, C.; Reuter, T.; Beauchemin, K.A.; Hao, X.; McAllister, T.A. Influence of Distiller’s Grains and Condensed Tannins in the Diet of Feedlot Cattle on Biohydrogen Production from Cattle Manure. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 6050–6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, H.; Jing, Y.; Tahir, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q. Comparative Study on Bio-Hydrogen Production from Corn Stover: Photo-Fermentation, Dark-Fermentation and Dark-Photo Co-Fermentation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 3807–3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Han, B.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Xing, X.-H. Effects of Operating Parameters on Hydrogen Production from Raw Wet Steam-Exploded Cornstalk and Two-Stage Fermentation Potential for Biohythane Production. Biochem. Eng. J. 2014, 90, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rangel, M.; Barboza-Corona, J.E.; Valdez-Vazquez, I. Effect of the Organic Loading Rate and Temperature on Hydrogen Production via Consolidated Bioprocessing of Raw Lignocellulosic Substrate. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 35907–35918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, G.; Wang, X.; Zhao, J.; Jia, B.; Dai, X. Co-Fermentation of Waste Activated Sludge and Agricultural Waste for Hydrogen Production: Effect of the Carbon-to-Nitrogen Mass Ratio. Desalination Water Treat. 2020, 173, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. A., A.-A.; Longoria, A.; A. U., J.; A. S., S.; L. A., P.; Sebastian, P.J. Optimization of Hydrogen Yield from the Anaerobic Digestion of Crude Glycerol and Swine Manure. Catalysts 2019, 9, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Cheng, J.; Murphy, J.D. Unexpectedly Low Biohydrogen Yields in Co-Fermentation of Acid Pretreated Cassava Residue and Swine Manure. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 151, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilroyed, B.; Chang, C.; Chu, A.; Hao, X. Effect of Temperature on Anaerobic Fermentative Hydrogen Gas Production from Feedlot Cattle Manure Using Mixed Microflora. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 4301–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, D.F.; Parker, R.A.; Kendrick, J.S. The Box Plot: A Simple Visual Method to Interpret Data. Ann. Intern. Med. 1989, 110, 916–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Fan, S.-Q.; Zhang, J.-N.; Fan, Y.-T.; Hou, H.-W. Enhanced Bio-Hydrogen Production from Corn Stalk by Anaerobic Fermentation Using Response Surface Methodology. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 12770–12779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, D.; Pérez-Zapatero, E.; Martín-Marroquín, J.M. Comparative Effect of Acid and Heat Inoculum Pretreatment on Dark Fermentative Biohydrogen Production. Environ. Res. 2023, 239, 117433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Vázquez, A.R.; Sánchez, A.; Valdez-Vazquez, I. Hydration Treatments Increase the Biodegradability of Native Wheat Straw for Hydrogen Production by a Microbial Consortium. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 19899–19904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A.; Umar, H.; Shah, T.A.; Tabassum, R. Fermentation of Simple and Complex Substrates to Biohydrogen Using Pure Bacillus Cereus RTUA and RTUB Strains. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 18, 100704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, M.; Dinsdale, R.; Guwy, A. Mesophilic Biohydrogen Production from Calcium Hydroxide Treated Wheat Straw. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 16891–16901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quéméneur, M.; Bittel, M.; Trably, E.; Dumas, C.; Fourage, L.; Ravot, G.; Steyer, J.-P.; Carrère, H. Effect of Enzyme Addition on Fermentative Hydrogen Production from Wheat Straw. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 10639–10647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasirian, N.; Almassi, M.; Minaei, S.; Widmann, R. Development of a Method for Biohydrogen Production from Wheat Straw by Dark Fermentation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, G.; Vayenas, D.; Lyberatos, G. Ethanol and Hydrogen Production from Sunflower Straw: The Effect of Pretreatment on the Whole Slurry Fermentation. Biochem. Eng. J. 2016, 116, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monlau, F.; Trably, E.; Barakat, A.; Hamelin, J.; Steyer, J.-P.; Carrere, H. Two-Stage Alkaline–Enzymatic Pretreatments to Enhance Biohydrogen Production from Sunflower Stalks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 12591–12599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monlau, F.; Kaparaju, P.; Trably, E.; Steyer, J.P.; Carrere, H. Alkaline Pretreatment to Enhance One-Stage CH4 and Two-Stage H2/CH4 Production from Sunflower Stalks: Mass, Energy and Economical Balances. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 260, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.-L.; Guo, W.-Q.; Wang, A.-J.; Zhao, L.; Xu, C.-J.; Zhao, Q.; Ren, N.-Q. Enhanced Cellulosic Hydrogen Production from Lime-Treated Cornstalk Wastes Using Thermophilic Anaerobic Microflora. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 13161–13166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.-M.; Ma, H.-C.; Fan, Y.-T.; Hou, H.-W. Bioaugmented Cellulosic Hydrogen Production from Cornstalk by Integrating Dilute Acid-Enzyme Hydrolysis and Dark Fermentation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 4852–4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).