Abstract

This study evaluates growth and income distribution targets needed to alleviate poverty and eradicate hunger, and assesses strategies to achieve these goals in rural areas in South Africa. Most development policy studies concentrate on growth, inequality, and poverty reduction, while explicit SDG-related applications receive less attention, especially in Africa. To fill this gap, we apply a framework that combines a recursive dynamic CGE model with a microeconomic simulation model in a top-down and bottom-up fashion. We explore two scenarios: a business-as-usual simulation and an agricultural growth simulation that tests investment, export enhancement, productivity improvements, and social assistance extension. The agriculture policy includes targeted social assistance. Halving poverty and eradicating extreme hunger requires 2.7% annual economic growth and 3.6% agricultural growth from 2018 to 2030. In the business-as-usual scenario, poverty is expected to rise from 55.2% in 2015 to 56.1% by 2030, with 24% still below the food poverty line. The agricultural growth scenario can advance hunger and poverty goals if individual consumption increases by 2.6% annually. Achieving SDG targets for hunger and poverty demands interventions beyond agricultural policy. South Africa can achieve its hunger and poverty SDG goals through a combination of agricultural investments, social assistance, and labour policies.

1. Introduction

Economic development has traditionally been associated with structural transformation. Agriculture has played a pivotal role in this discourse, with the progression from agriculture to manufacturing and services constituting a persistent theme. This has incited a continuous debate regarding the prioritisation of sources of economic growth for developmental purposes: some argue for accelerating the industrialisation process [1,2,3], while others advocate for agriculture-led growth, citing its strong linkages to poverty alleviation [4,5]. The experience of the Green Revolution offered an alternative perspective, suggesting that modern science and technology could enable agriculture to function as a dynamic engine of growth and development. Nevertheless, the optimism surrounding the sector’s potential was mitigated by the suboptimal performance of numerous agricultural development initiatives, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, alongside the transition to export-oriented manufacturing growth in the economies of East Asian nations [6]. More recently, the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations (SDGs or Global Goals) have shifted the focus from the growth–agricultural productivity nexus to reforming the agricultural sector with the objective of enhancing job creation and food (as well as nutritional security), thus reducing high levels of poverty in developing countries. More specifically, as shown in Box 1, the first two SDGs specifically target to reduce poverty and eradicate hunger.

Box 1. Goals 1 and 2 of the SDGs.

- SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS 1 and 2

- GOAL 1.1 TARGETS

- “By 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions.”

- GOAL 2.1 TARGETS

- “By 2030, end hunger and ensure access by all people, in particular the poor and people in vulnerable situations, including infants, to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round.”

- http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html (accessed on 15 May 2025)

This approach is based on the assumption that agricultural activities are the main source of income and economic livelihoods for the majority of poor people in developing countries. Thus, strategies to achieve “pro-poor” or “shared growth” would be more effective if policies and investments targeted growing labour-intensive sectors such as agriculture, where the poor are active participants and important stakeholders. Agriculture is fundamentally related to various sectors, with extensive research supporting its crucial role in enhancing yields, driving economic expansion, creating employment, and mitigating poverty [5,6,7,8]. Although most of these development policy studies focus on growth, inequality, and poverty reduction, applications that are explicit to SDG targets receive much less attention, particularly in Africa.

Within the general equilibrium tradition, computable general equilibrium (CGE) models have emerged as a useful and viable way to study changes related to the attainment of the SDGs, utilizing data from national accounts to depict economic flows. Lofgren and Diaz-Bonilla [9] extended a CGE model to connect income, labour, and education, asserting that more public investment is needed to meet Ethiopia’s Millenium Development Goals (MDGs), while Maisonnave et al. [10] used a CGE model to show the complexities of trade-offs between attaining MDG goals and their financing in South Africa. The World Bank’s MAMS model, made for MDG policy studies by 2015, includes several applications to the SDGs in the developing world [11]. Other uses of CGE models for SDG matters in Africa include studies by Balma et al. [12] for Burkina Faso, Fofana et al. [13] for South Africa, and Karim et al. [14] and Aarich et al. [15] focussing on Morocco, as well as analyses by Roson [16] and Yeshineh and Woldeyes [17] concentrating on Ethiopia. Although these studies have provided a coherent and systematic integration of macro-micro-pathways to help align with the objectives of the SDGs, less attention has been given to evaluating the targets for growth and income (or expenditure) distribution required for attaining the SDGs.

This study aims to address these gaps and has two main goals: first, to assess the growth and income (or spending) distribution targets that are required to achieve the goals to alleviate poverty and eradicate hunger, and second, to pinpoint and evaluate strategies that facilitate the achievement of poverty reduction and hunger elimination targets in rural regions. The latter is through agriculture interventions, since agriculture is a major activity in rural areas (South Africa lacks an official definition of rural areas; most government departments, including Statistics South Africa, define rural areas as “the sparsely populated areas in which people farm or depend on natural resources, including the villages and small towns that are dispersed through these areas. In addition, they include the large settlements in the former homelands, created by the apartheid removals, which depend for their survival on migratory labour and remittances.” (Rural Development Framework of 1997). This is the definition used in the rest of this study. By rural development, we shall take it to mean economic growth that reduces poverty and eliminates hunger in those rural areas.). The study develops and applies a dynamic macro-micro modelling framework that combines a recursive dynamic CGE model with a microeconomic simulation model in a top-down and bottom-up fashion. The economic modelling methodology helps to define and quantify the milestones to be reached to achieve the SDGs. Furthermore, the analysis contributes to the identification and selection of priority areas for public and private investments to achieve the SDGs and targets.

The macro-micro modelling is applied to a case study of South Africa, which is an interesting case test to focus, on for several reasons. Along with the other 193 Member States of the United Nations, South Africa has committed to meet the SDGs by tackling significant issues such as poverty, inequality, and unemployment. Despite being an upper middle-income country, South Africa has the world’s highest income inequality and high poverty rates, particularly affecting rural areas. Stagnant economic growth over the past two decades, increasing public debt, energy crises, and global disruptions, such as climate change [18], the COVID-19 pandemic [19], and conflicts in Ukraine and Russia [20] have exacerbated poverty, inequality, and unemployment. Therefore, achieving “zero hunger” and eliminating poverty, which are key SDGs, will require reviving economic growth and transformative changes in the rural and agricultural sectors of South Africa. Indeed, South Africa’s 2030 National Development Plan Vision, the country’s blueprint for development, makes clear the importance of rural development. Additionally, this focus and commitment to rural development and agriculture has been recognised in the Medium Term Development Plan (2025–2030), which includes medium-term strategies to ensure food security and commitment to rural development. Although these initiatives and pronouncements are commendable, the specific impact of agriculture on economic development and the achievement of the SDGs is still underexplored. In particular, identifying policy actions that have the potential to advance progress requires an evidence-based approach. The models are used to perform ex ante assessments of the likely impacts of policy actions on South Africa’s key development goals over the period 2015–2030. Assessing the impacts of milestones and actions helps create policies to meet SDG goals of eradicating poverty and hunger. Although certain particulars of the model pertain directly to South Africa, the analysis is also applicable to other developing and middle-income nations (see, for example, [21], which applies a similar approach to ten African countries, while [22,23] use a similar approach with an agriculture-rural focus for Senegal.

The subsequent structure of the paper is as follows. Section 2 develops the methodology used to quantitatively assess the SDG milestones, and includes an overview of the South African economy based on the used household and macroeconomic data. Section 3 presents the scenarios and results, with an extended discussion of the results. Section 4 gives an extended discussion of the findings, putting into context and pointing to caveats and fruitful areas for future research. Section 5 concludes the paper and points out caveats and policy directions.

2. Methodology and Data

2.1. Conceptual Framework

Recent studies have developed frameworks to study SDGs, highlighting their connections and interdependencies (see [24,25] for reviews). Model types are key in forming sustainable development policies. Input–output models describe national economies but are limited for long-term scenarios, due to their static nature [26,27]. Macro-econometric models, which have the advantage of being dynamic and which rely on extensive historical data, also have restricted utility for long-term analysis [28,29]. System dynamics models work well for scenario analysis, but pose challenges in setting boundaries and feedback loops [30,31]. Bottom-up optimization and simulation models, with their focused scope and detailed exploration of technologies and alternatives, are beneficial for sector-based planning; nevertheless, they typically lack feedback loops with other sectors in the broader economy [27,29]. Multi-agent models, though promising for sustainable development [32], are experimental and have few applications [33]. Hybrid and integrated assessment models combine different modelling approaches, addressing some shortcomings of the categories mentioned above and offering a more adaptable and customized approach [24,27,34], but they struggle to adequately address issues of poverty and inequality. Dynamic CGE models are advantageous for scenario analysis, utilising a consistent theoretical framework and sectoral feedbacks; however, their theoretical bases may hinder their suitability for modelling sustainable development transitions [35,36].

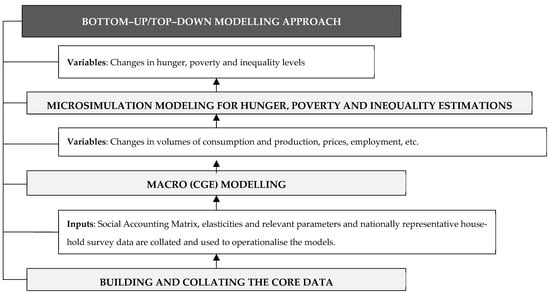

The approach used in this study involves using macro–micro economic simulation models to facilitate the identification and prioritization of effective and efficient policies and investment areas to reduce hunger and poverty, in line with the SDG Agenda. As the name implies, the models combine a macro (CGE) model and a micro (MS) model to address hunger and poverty development goals and targets. Figure 1 summarises in schematic fashion the economic modelling framework, which is in three main iterative yet consistent steps, discussed in the rest of this section, which include data collection and collation, modelling and analysis.

Figure 1.

Economic Modelling Steps. Source: Authors’ compilations.

As shown in Figure 1, a layered micro–macro model for setting the priorities for hunger and poverty reduction is used. Starting with the data collection and its collation, the micro and macro models are interlinked in a top-down fashion. The micro model follows the specifications of [13] and builds on the non-parametric income distribution microsimulation modelling to assess the income (or expenditure) growth targets and their distribution across the population, in order to achieve the nationwide poverty reduction SDG goals. At the same time, because the model distinguishes rural from urban areas, this assessment also contributes to the setting of rural poverty reduction goals. These income or expenditure growth targets are then imposed on the macro model to generate, in turn, the growth and investments targets for the entire economy, and the rural sectors specifically. In so doing, the macro model also contributes to setting productivity growth and external trade growth targets. A major advantage of the layered approach in this study is its ability to project economic development to 2030, and to accommodate a disaggregated production sector structure and multiple individuals at the micro level.

We outline the empirical approach in the rest of this section in three steps. We begin with an outline of the micro-economic simulation model and its analysis. This is followed by a discussion of the CGE model, before concluding with a brief discussion of the underlying data.

2.2. The Micro Model

The micromodel allows for the direct evaluation of poverty and inequality levels, with individual-level assessments grounded in microdata. Poverty levels are linked to income or consumption expenditure levels and their distribution throughout the population, as suggested by Ravallion [37,38]. Our study is innovative in employing a nonparametric microsimulation model to evaluate the target aggregate consumption expenditure (growth) and its distribution necessary to meet the SDG targets on poverty and hunger.

Microsimulation models can be distinguished by various characteristics. The key aspects include the incorporation of agents’ behaviours, the time frame of their decision-making processes, and the inclusion of general equilibrium effects, as noted by Bourguignon and Spadaro [39] and Spadaro [40]. Two categories of such models can be distinguished—behavioural and accounting. Accounting approaches assess what are often referred as ‘morning-after effects’ or the direct first-order effects of interventions [40]. On the other hand, behavioural models seek to uncover second-order effects of interventions, and often rely on mathematical modelling of underlying economic decision processes of individuals. The Lucas critique [41], which points out issues of structural dependence caused by selected parameters within structural modelling, is frequently regarded as a significant challenge. To mitigate these issues, reweighting techniques are recommended (see, for instance, Meagher [42], Devarajan and Go [43], Agénor et al. [44], Ferreira and Horridge [45], Buddelmeyer et al. [46], and Hérault [47]).

This paper uses an SDG micro-model with a non-parametric framework. The approach consists in adjusting the probability distribution of (per capita) income or expenditure consumption to create coherence and consistency with aggregate data. Changes in individual income or consumption expenditure are translated into changes in consumption behaviour occurring within the population through adjustments in the probability distribution of income or consumption expenditure, in response to a (macro) shock or change in aggregate data. Thus, individuals implicitly adjust their behaviour in response to a (macro) shock. The model minimizes the Kullback–Leibler cross-entropy measure of the distance between the posterior (w) and the prior (v) probability distributions of income or consumption expenditure (i), that is

with a specified posterior probability distribution of income or consumption expenditure

which is consistent with the following aggregate data or attributes:

- Population growth and urbanization, where is the urbanization ratio, and u the rural population share ():

- Mean per capita consumption expenditure () by group g, i.e., national and rural; individual (i) consumption expenditure

- Poverty headcount ratio () by poverty line (z), i.e., national, food, and international; individual (i) poverty status according to the poverty line (z):

The first-order condition derivatives , and are Lagrangian parameters associated with constraints related to the posterior probability distribution, population growth and urbanisation, mean consumption expenditures, and poverty headcount ratios, respectively, as follows:

We make use of the of Foster–Greer–Thorbecke (FGT) [48] family of poverty measures. There are three measures, the Poverty Headcount Index , the Poverty Gap Index () and the Poverty Severity Index (). measures the proportion of the population that is poor. However, it does not say anything about the extent of poverty. () then shows the extent of poverty by measuring how far the poor are from the poverty line. In order to understand the inequality among the poor, the square of the poverty gap, (), is used. The formulae are shown below:

where is total population, is expenditure of individual i and is the poverty line.

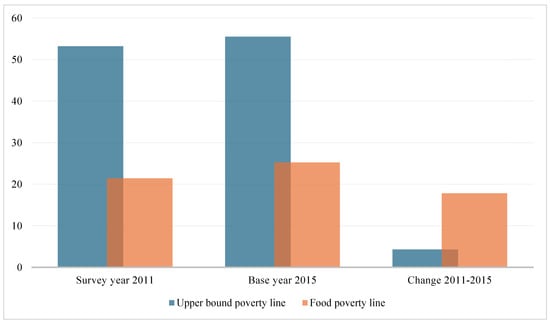

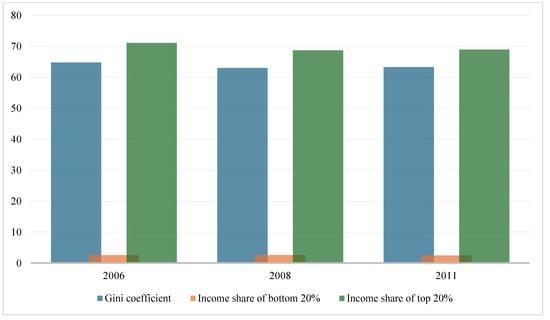

The poverty line measures the minimum expenditure requirement to fulfil basic food and non-food needs. Although there is no international standard for measuring hunger, the standard approach is to compare the number of calories eaten by a person to the number of calories needed (i.e., 2100 calories per person per day). To construct the poverty line, it is necessary to specify a consumption package considered adequate for basic food and non-food consumption needs and then estimate the cost of that package. In general, a number of poverty lines are constructed. The extreme poverty line, also known as the food poverty line, measures the minimum amount of money needed to purchase a food package to meet basic food needs for a given country. The standard poverty line adds to the food poverty line, and includes the basic non-food items to measure the minimum amount of money to satisfy the basic food and non-food needs in a given country. Finally, the empirical strategy for the microsimulation applies the Kullback–Leibler minimum divergence cross-entropy (CE) method in two distinct phases. Initially, the sample weights assigned to households in the Income and Expenditure Survey [49] are converted into a prior probability distribution. Subsequently, the Kullback–Leibler minimum divergence cross-entropy (CE) is employed to derive a posterior probability distribution aligning with household income, categorized by sources such as labour, capital, and transfers, as observed in the CGE model post-shock via the Bourguignon method [50]. This approach ensures that the distribution of consumption expenditures among the population aligns properly (Figure 2). Additionally, compliance with Engel’s law is essential, particularly regarding the increasing share of income spent on food, reflecting the income inequality prevalent in South Africa (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Hunger and Poverty Goals and Targets (%). Source: Computations by the authors using Statistics South Africa [51]. Note: in 2015, the poverty line for overall living expenses was set at ZAR 992, while the threshold for food-related poverty was at ZAR 441 per person, each month.

Figure 3.

Income inequality trend, 2006–2011. Source: Author computations based on World Bank [52].

2.3. The Macro Model

The macro model utilised in our study is a dual economy CGE model for the economy. (The term ‘dual economy’ refers to the existence of traditional and modern sectors within one economy (Lewis [53]). Lewis two-sector model assumptions are that (a) the traditional sector is agriculture and (b) the modern sector is industry.) The model approach is based on the Walrasian approach concerning small open economies. Producers, aiming to maximize their profits, and consumers, striving to maximize their utility, respond to changes in relative prices by adjusting the quantities they supply and demand, ensuring simultaneous market equilibrium. The economy adopts global market prices for exports and imports. The CGE model’s typical features stem from the dynamic CGE model proposed by the Partnership for Economic Policy (PEP), as described by Decaluwe et al. [54]. The PEP model is customised to fit South African realities and data. The CGE model is presented in this section in four major blocks: supply block (production and trade), demand block (income, savings and demand), and macroeconomic block (macroeconomic constraints and closure rules). While the spotlight is on the main mechanisms of the model, the full specification of the equations and definition of parameters, variables, and sets of the model can be provided, upon request, from the authors.

2.3.1. Production, Trade and Labour Markets

Inventory and warehouse management practices have a significant influence. In terms of production, it is assumed that the production technology exhibits constant returns to scale, represented through nested constant elasticity of substitution (CES) functions (Leontief and Cobb–Douglas functional forms are two specific cases of CES function implying zero and one elasticity of substitution, respectively). The aggregate output XSTj is postulated as a Leontief function dependent on value-added VAj and intermediate consumption CIj (Equations (1) and (2)). Employing a Leontief function implies that production activities require a fixed volume of value added and a fixed amount of intermediate consumption, with no substitution possible between them.

Equation (3) describes the activities’ j value added (VAj) as a CES function that integrates the composite labour demand (LDCj) and capital demand (KDj). Equation (4) outlines the activities’ behaviour in maximizing profit (or minimizing cost) by stating that the ratio of LDCj to KDj is equivalent to the inverse ratio of their respective factor prices (Rj to WCj). Activities, j, continue to employ labour and capital until their marginal products match their factor prices, which are the rental rate for capital Rj or the wage rate for labour WCj.

Equations (5) and (6) describe the overall demand for labour within each activity, j. In the Constant Elasticity of Substitution (CES) framework, Equation (5) accounts for the constraints on substituting between the various labour types, l. Meanwhile, Equation (4) posits that labour is hired in a cost-effective manner by equating the ratio between a particular labour type and composite labour (marginal product) to the inverse ratio of that labour type’s wage rate and the composite labour wage rate, as dictated by the first-order condition.

Equation (6), known as the Leontief equation, extracts the aggregate composite activities of intermediate consumptions (CIj) from the activity of intermediate consumption (DIi,j) for each specific commodity i. The input–output coefficients (aij) externally specify the complementary proportions of DIi,j.

2.3.2. Demand Block

The demand block outlines the income, saving, and consumption behaviour of institutions. Here, a household’s total income is the sum of earnings from skilled and unskilled labour, capital returns, and indexed transfer income. The disposable income of households is derived by subtracting income tax and indexed out-transfers from their gross income. A fixed portion of this disposable income is allocated to savings. For firms, income is calculated by adding their portion of capital income to their in-transfers. Once firms pay government taxes and make real-term fixed out-transfers to other agents, what remains becomes their savings. The government receives income from direct taxes on household and firm incomes, as well as export taxes, import tariffs, indirect taxes on imported and domestic goods, production taxes, a share of capital incomes, and indexed transfer receipts, which include dividends, concession sales, and foreign aid. Government savings are derived by deducting consumption and indexed transfer payments from total government income. It is important to note that while government spending is set in real terms, nominal expenditures are variable and depend on price changes.

An extended linear expenditure system (ELES) is utilized to represent demand by illustrating both consumption and labour supply behaviours. This model distinguishes between non-discretionary components, related to autonomous consumption of goods and leisure—which are not influenced by income changes—and a discretionary component tied to induced consumption, which is income-dependent. Autonomous consumption is influenced by factors outside of income, such as social policies, and remains constant, unlike induced consumption, which varies with disposable income.

A unitary household h utility is modelled by an extended Stone–Geary utility function defined over (i) market products and l leisure time (). C and represent the total and subsistence levels of consumption of market products, respectively. and are the total and minimum levels of leisure time by household members. Leisure time is a normal good. For simplicity sake, here the subscripts h, i and l are ignored. and are the marginal budget shares that determine the allocation of household supernumerary income between market products and individual leisure times, with .

The household faces budget and time constraints:

Y is the gross income net of saving, p the commodity market price, w the wage rate, and L the time supplies to market. The full income constraint below is obtained from the above equations:

The following demand and supply function is derived from utility maximization under the full income constraint:

The maximum time available for work and leisure is computed as follows:

Both poor and non-poor households display a non-discretionary component related to autonomous consumption of product () and leisure () and a discretionary component that fluctuates with income and prices. First, changes in consumption and labour supply of poor households resulting from the SDG Push interventions are transmitted from the micro model to the macro model through the non-discretionary consumptions of products and leisure. Second, both poor and non-poor households are affected by the feedback effects of initial shocks through their exposure to markets (e.g., income and price effects). The non-discretionary component of the demand for products and leisure time from household members are calibrated using the Frish parameter.

The Frisch parameter measures the income elasticity of the marginal utility of income, which declines as income increases, and is expressed as follows:

The denominator refers to the supernumerary income, which is the leftover income after the consumer fulfils all basic subsistence requirements. This supernumerary income impacts how much is spent on discretionary activities, like purchasing products and enjoying leisure, with portions α and β allotted to these categories. When the supernumerary income is smaller, the absolute value of the Frisch parameter increases, while the discretionary spending on total consumption and leisure decreases. Hence, a higher Frisch parameter is assigned to lower-income households to emphasize the essential consumption of products and leisure. Conversely, wealthier households receive a lower Frisch parameter to focus more on discretionary spending. The overall household consumption is modelled through a multi-tiered nested Cobb–Douglas function that merges market goods with leisure. On a first level, essential goods form final consumption via a Cobb–Douglas function, while on a broader scale, food and non-food items, along with leisure, are incorporated into final consumption using a Linear Expenditure System (LES) function.

2.3.3. Trade

Within the model, South Africa engages in international trade by importing goods and services while making payments for transfers and capital income. Simultaneously, the nation exports products and receives transfers from other countries. To represent these interactions, we adopt the small-country assumption and incorporate the traditional Armington approach, which postulates that there are well-behaved preferences within a weakly separable product category that comprises similar, but not identical, products (Armington [55]). These products are distinguished by their origin, and a CES (Constant Elasticity of Substitution) is assumed for products within the same category. Similarly, on the export front, the behaviour is modelled via a constant elasticity of transformation (CET) function, reflecting the variations in commodities sold across different markets. We consider world market prices as exogenous, while the domestic prices are dictated by local supply-and-demand equilibrium. This indicates that South Africa acts as a price taker in global markets; hence, to enhance its market share globally, it must increase its competitiveness.

2.3.4. Unemployment

The modelling of labour markets is enriched by empirical data from South Africa, as demonstrated by Kingdon and Knight [56,57]. The labour market segments—unskilled, low-skilled, medium-skilled, and skilled—operate under the assumption of imperfect market conditions. This scenario is examined using the wage curve model proposed by Blanchflower and Oswald [58]. The wage curve captures the relationship between the unemployment rate () and the real wage rate () for a given labour category . The relationship is expressed as follows:

where is the wage rate for labour category ; , the average economywide price level; and , the elasticity of the real wage rate with respect to the changes in the unemployment rate.

In contrast, the high-skilled labour market is presumed to function according to a competitive market clearance pattern, suggesting complete employment. Workers in every skill category are considered to have full mobility among various industries within the nine provinces and the two settlement types (urban and rural). Regarding rural–urban migration and remittances, the model incorporates an exogenous framework for the movement of labour between rural and urban zones and between provinces, specific to each skill category. Additionally, the proportions of labour income allocated to the origin and destination locations as internal remittances are exogenously determined. As labour relocates from one area to another, remittances flow in the reverse path. This external framework implies that a mix of economic and non-economic factors shape urban–rural migration and remittance flows. The model also examines the sensitivity of internal remittance rates.

2.3.5. Macroeconomic Constraints, Closure Rules and Dynamics

All commodity markets, including capital and skilled labour markets, follow the neoclassical market-clearing price system, in which simultaneously determined producer and consumer prices vary only by given tax/subsidy and margins rates. Each market is cleared when composite supply equals demand (final household consumption, final government consumption, intermediate demand, demand for fixed capital formation, and change in stock). Unskilled workers’ unemployment rates clear the supplies and demands in the unskilled labour market. Total investment, i.e., the fixed capital formation and the changes in stocks, is equal to the savings of domestic institutions—household, firm, and government—plus the foreign saving or current account balance converted to the local currency, using the exchange rate. Capital markets and skilled labour markets are cleared. Regarding closure rules, we posit that the nominal exchange rate serves as the numeraire in our model. We then apply the small-country hypothesis, wherein South Africa acts as price taker and international prices are predetermined. Furthermore, we assume that the current account balance and the government’s expenditure on goods and services, alongside all tax rates (which include direct, indirect, import, and producer taxes), remain constant. To construct the model’s reference trajectory over time, it is presumed that the stock of capital increases between periods, due to new sector investments. The distribution of new private investment adheres to the accumulation equation of Jung and Thorbecke [59]. Based on the model’s dynamic framework, derived from [59], both producers and consumers are short-sighted, making decisions to maximize utility and profits within a single period. The transition across periods is governed by the savings and capital accumulation. A typical capital accumulation equation is employed, where savings add to the current capital stock after accounting for depreciation. In this framework, sectors vie for investment, with the allocation of new capital being dictated by the sector-specific costs, returns on capital, and past investment trends.

2.4. The Data and Model Calibration and Implementation

The South African CGE model is implemented using the modified Social Accounting Matrix (SAM) for 2023, building upon the 2015 SAM crafted by van Seventer et al. [60] and further elaborated in van Seventer and Davies [61]. We make several modifications to the SAM to convert it towards an agriculture-focused SAM (Ag-SAM). This Ag-SAM is constructed utilizing the Supply and Use Table (SUT) and the income and expenditure surveys, along with the labour force surveys. Since the data to build the Ag-SAM were derived from various sources and different time periods, the initially constructed SAM contained inconsistencies. We employed the RAS method and the GAMS programme, as outlined in Lemelin et al. [62], to reconcile this information and achieve a balanced SAM. The program minimizes alterations to the original data using multiple optimization techniques, such as cross-entropy and least squares. To update the SAM, we use the adaptation proposed in Robinson et al., [63] which uses prior information (the original balanced SAM) and recent macroeconomic conditions, to estimate a new SAM through cross entropy.

The resulting Ag-SAM includes thirty industries or activities, featuring a disaggregated “Agriculture, forestry, and fishing” and thirty commodities, including a staple for “Agriculture, forestry and fishing”. Ninety labour categories derived from nine provinces (respectively, Western Cape, Eastern Cape, Northern Cape, Free State, KwaZulu-Natal, North West, Gauteng, Mpumalanga, and Limpopo), two settlement types (urban and rural), and five levels of skill category (skill categories (5): based on the highest education level achieved, i.e., Unskilled: no schooling and less than Grade 1, Lower-skilled: grade 2 to 7, Medium-skilled: Grade 12, Skilled: certificate and diploma, High-skilled: degree and postgraduate diploma) using education attainment, are incorporated. There is a single capital factor account and four tax accounts: taxes on production, production subsidies, taxes and duties on products, and current taxes on income and wealth, twenty-one institutional accounts, comprising 18 household segments, and two capital accounts: fixed capital formation and changes in inventory levels. The result is the final balanced Ag-SAM.

The model’s reliability has been validated through sensitivity analysis, examining different closures and parameter choices (see Fofana et al. [13] and Mabugu et al. [64]. Additionally, ref. [13] assessed multiple data series to find that the model’s outcomes are somewhat influenced by the selected series. The MS model is applied using the household survey from the 2017 National Income Dynamics Study and from [49,51].

We end with a brief discussion of key features of the South African economy at the benchmark level of the economy (2015) painted by the SAM. According to the Ag-SAM, and summarised in Table 1, which reflects the composition of the South African economy’s sectors, the service sector accounts for approximately 70.2% of GDP, making it the largest sector, while the agricultural and industrial sectors contribute 2.3% and 17.5%, respectively. These sectors are significant in both exports and imports.

Table 1.

Distribution of the South African economy across key sectors, 2015, %.

The study modifies the South African SAM framework to categorise the labour force into 90 segments by worker and market characteristics, province, settlement type, and skill level. As previously argued in [56,57], in the Ag-SAM in Table 2, high-skilled labour is associated with lower unemployment while unskilled labour faces higher unemployment. Furthermore, unemployment is more common in rural areas (Table 2). Table 3 shows that households mainly rely on low-skilled labour income (Table 3).

Table 2.

Unemployment rates by skill category in South Africa.

Table 3.

Labour earnings distribution (percentages).

3. Simulations and Results

Establishing simulation scenarios is an essential phase, because they help with increasing modelling accuracy and also aid in the meaningful comparison and interpretation of the results. These scenarios are chosen to help address South Africa’s dual development objectives as outlined earlier in the study objectives: firstly, to evaluate the targets for growth and income (or expenditure) distribution aimed at lowering poverty and eliminating hunger in South Africa as outlined by the SDGs, and secondly, to identify and evaluate an intervention strategy that supports achieving poverty reduction targets in rural areas.

Our implementation strategy is in three interrelated steps. First, it is customary to establish a Business-as-Usual (BAU) scenario, serving as a benchmark to evaluate proposed policy modifications. Essentially, the BAU scenario outlines a growth path that the economy would follow in the absence of any significant disruptions during a specified timeframe. For the current study, the BAU scenario is formulated by assuming that the economy will replicate its average growth performance from 2008 to 2023. This average annual growth is projected from 2024 to 2030, to construct the BAU. In addition, the BAU scenario factors in recent trends in per capita final-consumption expenditure, income inequality, and changes in rural and urban demographics and urbanisation patterns. Using data and models discussed previously, the BAU is calibrated. All the model input data including parameters is reported in the Appendix. Second, we use the modelling to work out the milestones for growth and consumption necessary for poverty and hunger reduction. Third, we design a strategy informed by the modelling to eradicate hunger and reduce poverty. We call this the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) scenario, as it aligns with demographic and rural–urbanisation targets, utilising the SDGs concerning poverty and hunger to assess changes in consumption growth and income inequality.

3.1. Milestones for SDG Poverty Reduction and Hunger Eradication Results

The simulations aim to determine the economic changes needed to meet specific targets, focusing on necessary income growth and distribution. Below are the poverty targets for South Africa and its rural regions. Table 4 highlights the poverty shifts required to achieve the SDGs by 2030. Simulating these economic adjustments involves assumptions about the economy’s path to 2030, as detailed in the BAU.

Table 4.

Rural Poverty Status and Goals.

To address the differences in rural and urban dynamics and explore rural strategies effectively, assumptions regarding the growth of population are key. According to calculations based on the United Nations data and reported in Table 5, the total population is expected to rise from 56.7 million in 2017 to 69.3 million by 2030, with an overall annual growth rate of 1.6%. Regionally, urban areas will grow by 2.3% annually, while rural areas expect a growth of only 0.1%. Urbanisation rates are projected to increase from 65.8% in 2017 to 71.5% by 2030, a 10.4% growth over the period, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Population Growth and Urbanisation, 2015–2030.

Table 6 provides the necessary expenditure growth targets for poverty calculation. Between 2017 and 2030, the per capita consumption expenditure must rise by 34.5%, averaging 2.0% annually. The overall consumption expenditure should grow at an annual average rate of 3.6%. These metrics support the calculation of target inequality rates using the Gini and Theil indices. (The Gini index measures overall income inequality, but is not perfectly decomposable (with zero residue), so the Theil index (which is perfectly decomposable) is used for measuring income inequality within rural groups.) The Gini coefficient is expected to decrease by 21.6%, and the Theil index by 41.5%, within the same timeframe. These national targets, designed to halve poverty and eliminate hunger by 2030, are detailed in the upper section of Table 6.

Table 6.

National Poverty Reduction Goals and Targets.

To gain a more detailed understanding of the results, an intermediate sectoral output table is created. Table 7 presents the GDP data divided by sector, including agriculture, industry, and manufacturing. The model is performing as expected: from 2023 to 2030, all sectors are predicted to grow, with economic growth rates projected to rise from 1.65% in 2024 to 2.05% in agriculture, 0.5% to 0.7% in industry, 0.9% to 1.3% in manufacturing, and 2% in services. The mechanism is a decline in domestic prices due to lower producer prices and trade margins, which boosts consumption and stimulates domestic demand. This results in increased production in most sectors, such as agriculture (which sees the highest increase) and related activities, manufacturing (due to its connections with agro-industry sectors like food and beverages), and service sectors, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Percentage change in total domestic production in different sectors.

In Table 8, the micro-simulated projections for rural areas illustrate the ambitious targets of eradicating hunger and halving poverty. To achieve these objectives, a significant reduction of 48.2% in rural headcount poverty is essential. Concurrently, there must be a substantial enhancement of 42.8% in the final household consumption expenditure for rural populations.

Table 8.

Rural Poverty Results.

Finally, discussion turns to the ramifications on needed consumption required for the fulfilment of the hunger and poverty SDG targets. Illustrated in Table 9 are the projected outcomes vis-à-vis the target trajectory for per capita required-consumption escalation. The findings delineate a requisite per capita alimentary-consumption augmentation rate of 17.5% across the entire analytical temporal span, necessitating an annual mean growth of 2.7%.

Table 9.

Food Consumption Growth.

The increase in household consumption expenditure requirement per province is given in Table 10. The increase required tends to be higher in the rural provinces than in the urban ones, which is quite intuitive. In the rural provinces, the annual average growth targets change by more than 3%. In terms of poverty reduction, the resulting numbers of persons impacted are given in Table 11.

Table 10.

Rise in household consumption spending by province and area.

Table 11.

Poverty reduction by province and area, number of persons.

3.2. Strategic Options for Inclusive Growth—SDG Scenario Results

Next, the micro targets are imposed onto the macro model, to inform on household consumption. The prerequisites for meeting the SDGs in 2030 are that (a) household final consumption expenditure, and average annual growth from 2018 to 2030, is 3.6%; and (b) rural household final consumption expenditure, and average annual growth for 2018 to 2030, is 2.5%. The targets for reduction in rural income inequality, through regional income growth targets, are given in Table 12.

Table 12.

Regional rural inequality targets.

The objective is now to use the results to develop step-by-step strategies that enable either the entire nation, or just rural regions, to achieve their specified SDG targets. Initially, a baseline scenario that represents the continuation of current practices is evaluated against these targets. Following this, various agricultural growth scenarios incorporating three policy tools are examined. These tools focus on investment, export enhancement, and productivity improvement strategies, all guided by the country’s National Development Plan 2030 and other agriculture strategy programs. The next phase involves independently evaluating these policy instruments. For each strategy, three distinct agriculture-focused tests are conducted:

- Investment Growth Strategy

- ✓

- Domestic Private Investments increase.

- ✓

- Foreign Investments increase.

- Export Growth Strategy

- ✓

- Agri-food Export Volumes increase.

- ✓

- Agri-food Export Prices increase.

- Productivity Growth Strategy

- ✓

- Food and Beverage Productivity and Production increase.

- ✓

- Agricultural Productivity and Production increase.

In the third step, we amalgamate effective approaches aimed at rural development. From this blend of simulations, we extract the ultimate strategy mix for rural development in South Africa, to achieve the SDGs. Table 13 and Table 14 exhibit the results of the reference scenario, or business-as-usual scenario. These results indicate that without any change, and if the economy continues its current trajectory, national targets remain unmet. Similarly, neither aggregate rural targets nor regional rural targets are achieved in six of the nine provinces. This suggests that for South Africa to fulfil the SDG targets, it must alter its present course and implement particular strategies.

Table 13.

Household Consumption Change, Reference Scenario (%).

Table 14.

Change in Rural Household Consumption by Province (%).

The second set of simulations thus assesses the effectiveness of different policy instruments with regard to rural income growth and distribution. We successively implement a series of tests through one-percent increase in domestic private investments, foreign investments, agri-food export volumes, agri-food export prices, food and beverage productivity and production, and agricultural productivity and production. The results of the tests are quite varied. Some strategies have positive effects on rural development, and thus have a chance to contribute to attaining the SDG targets 1.1 and 2.1. The other three, domestic private investment, agriculture export volumes and agriculture export prices, do not contribute to reaching the targets.

Now that we have a clear understanding of the simulations that support rural development (defined as above), we integrate them into a comprehensive rural development strategy package. This package comprises three key policies: foreign private investments, enhanced productivity and production in the food and beverage sector, and increased agricultural productivity and production. Our goal is to determine the necessary levels of these elements to achieve the hunger and poverty SDGs. The simulation results indicate that the economy requires a 10.5% annual growth rate in foreign investment, a 2.5% average annual growth in agricultural productivity, and a 3.5% average annual increase in agri-food commodity exports, to reach the SDG targets (Table 15). Under these conditions, both national and aggregate rural targets are met, with most regional rural targets achieved as well, except for the provinces Western Cape and Eastern Cape, which fall short, as shown in Table 16.

Table 15.

Household Final Consumption Change, Reference Scenario (%).

Table 16.

Rural Household Final Consumption Change by Province, Reference (%).

We now seek to determine the necessary growth rates for both the agricultural sector and the broader economy, to achieve the desired income and expenditure benchmarks aimed at halving poverty and eradicating extreme poverty and hunger. Simulation results indicate that the economy should expand at an average annual rate of 2.7%, while the agriculture sector needs to advance at a robust 3.6% from 2018 to 2030, as illustrated in Table 17.

Table 17.

Economic Growth, Rural Development Scenario (%).

Based on these results, policy makers in South Africa have multiple pathways available to achieve economic growth objectives, including those recently suggested by the IMF [66], OECD [67] and World Bank [68]). This study now extends these to examine the necessary investment levels to facilitate the targeted growth. According to the simulation outcomes, in order to reach the aforementioned growth objectives, the nation’s average annual investment growth must be 3.6%, with the agriculture sector requiring a growth rate of 2.2% between 2018 and 2030 (Table 18).

Table 18.

Investment Growth, Rural Development Scenario (%).

Despite the effort, the annual growth and expenditure increase is insufficient to raise everyone above the monthly income threshold by 2030, to eradicate hunger. One way that this shortfall could be covered is through extending the country’s social assistance coverage. According to the modelling, the required expansion of social assistance programs is large, aiming to envelop 10% of the population—approximately 7 million individuals—as outlined in Table 19. The anticipated reduction of the Gini index to 0.513 by 2030, 0.673 in 2015, underscores the criticality of income growth strategies in combating hunger. However, it becomes clear that income redistribution emerges not just as a vital, but as the keystone, element in a strategic overhaul aimed at diminishing inequality and extinguishing hunger. The primary focus of the social assistance policy should be on reaching these 7 million poor people. According to the results of our model in Table 19, these people are spread over the urban–rural divide and across the nine provinces, although predominantly in rural areas. Table 19 shows social assistance efforts are targeting six key provinces to support rural and urban poor: rural Limpopo, both rural and urban KwaZulu-Natal, rural and urban Eastern Cape, and urban Gauteng. In view of the fact that South Africa’s debt-to-GDP ratio has been rising over the past 15 years, it is crucial to explore various funding sources, rather than simply expanding the fiscal deficit. Maintaining the continuity of social assistance requires it to be self-financing and not contribute to further debt. In the short term, such a policy will need to be supported by a mix of budget cuts elsewhere, elevated taxes, and increased borrowing. While this task is crucial, it falls outside the purview of our research. Readers interested in the impacts of these financing strategies should refer to [13,20], who have carried out financing options of social grant extension in South Africa.

Table 19.

Number of assisted persons, SDG Scenario.

We next explore the relationship between spending increases and the employment and wage outlooks by skill level in regions targeted by the SDGs. In other words, we want to find out what the modelling can suggest in terms of using labour markets to tackle the social problems (see the IMF [66], OECD [67] and World Bank [68])). Unlike in the IMF [66], OECD [67] and World Bank [68], which are based on a national approach of labour markets and other structural interventions needed to unlock growth, wage expectations are assessed and compared across five skill categories in this study. The rationale is straightforward—the poor are predominantly found in the rural areas in South Africa, so any big contributions towards meeting hunger and poverty SDGs need to focus on addressing poor people in rural areas. Our results in Table 20 show that job and income prospects for skilled and high-skilled individuals are better than for other skill levels in all SDG-focused regions, with the exception of rural Northern Cape. Thus, a focus on upskilling labour in rural areas will increase their prospects of landing a decent job.

Table 20.

Annual wage rate change (%) under Sustainable Development Goals scenario.

In regions identified for achieving SDGs, households primarily depend on employment within unskilled, low-skilled, and medium-skilled labour sectors (Table 21). Consequently, the initiation and broadening of comprehensive skill development programs within these SDG-centric areas possess substantial potential to mitigate widespread income-inequality gaps.

Table 21.

Income distribution by production factor category in rural areas (percentages).

Summing up, rural South Africa hosts the highest poverty and hunger rates, positioning itself to significantly address hunger and extreme poverty through agricultural output and job creation. This issue is crucial for development. The analysis identifies milestones, intervention areas, and outcomes at national, provincial, and regional (urban vs. rural) levels. The main policy focus should be on social assistance, labour market improvements, agricultural productivity, and rural skill development.

4. Discussion

As the deadline for the SDGs approaches, could South Africa potentially capitalise on this opportunity, using agriculture? South Africa is confronted with pronounced income inequality and poverty, predominantly in rural locales. In the face of such challenges, this paper presents a novel framework combining micro- and macro-level models to identify steps for South Africa and similar nations to halve poverty and eradicate hunger by 2030. From an analytical perspective, the study’s innovation lies in employing a nonparametric microsimulation model to evaluate income growth and distribution targets needed to meet the SDG goals on hunger and poverty. The simulations develop strategies to help quantify milestones and achieve SDG targets on hunger and poverty. Beginning with a business-as-usual simulation, various agricultural growth strategies involving investment, export enhancement, and productivity improvements in and for agriculture are tested. This market-orientated agriculture policy intervention is complemented with a targeted social-assistance extension.

Milestones show that to halve poverty and eradicate extreme hunger, the economy must grow by 2.7% annually, and the agricultural sector by 3.6%, from 2018 to 2030. Market-orientated policy increases investments to achieve the economic growth and private consumption goals set by milestone assessments. According to the BAU simulation, the poverty headcount index is projected to rise from 55.2% in 2015 to 56.1% by 2030. This increase is exacerbated by population growth, making it unlikely that the target to halve poverty by 2030 will be achieved in the BAU scenario. Similarly, hunger will continue, with 24% of people below the food poverty line by 2030 under BAU. Conversely, the country can make inroads into the hunger and poverty goals if the individual consumption expenditure grows by an average of 2.6% annually. To reach the consumption expenditure growth target, a reduction in income inequality is essential, potentially through expanding social assistance to cover 10% of the population, thus working towards eradicating hunger by 2030. These findings, taken together, advocate for strategic interventions targeting agricultural expansion in rural areas such as Eastern Cape, Limpopo, Mpumalanga, KwaZulu-Natal and Northern Cape. In this way, South Africa can get on track with its key development agenda under mixed economic and social policies. Long-term development of skills for impoverished households, especially in rural areas, will increase employment and income opportunities necessary for attaining the SDGs.

The paper centres on the national focus with a distinct rural sector bias and on agriculture, which is predominant in these locales. It is, therefore, worthwhile in the discussion to explore how agriculture contributes to pro-poor growth within South Africa. The country’s history of unequal land distribution starkly contrasts with other developing countries where agricultural productivity growth could directly elevate income for impoverished smallholders. In South Africa, farming tends to be more capital intensive compared to many developing nations, which means that even significant growth in commercial farming is unlikely to result in substantial job creation for farmworkers. Additionally, the agricultural GDP contribution, roughly at 2%, is small, suggesting that even rapid growth in agriculture might result in limited economic impact. Given these imposing factors, questions about the relevance and generalization of insights from our numerical analysis are valid; however, we affirm their relevance when correctly interpreted. The principal message to be drawn is the existence of a multiplicative propagation effect stemming from investments in agriculture, as opposed to exact magnitudes of the numbers in the results. Notably, these secondary equilibrium effects are substantial, particularly in a nation where agriculture comprises a minor fraction of GDP. The results hinge on two pivotal, yet resilient, assumptions affirmed by other studies on South Africa: firstly, that productivity improvements in agriculture will mainly aid poorer consumers, through reduced food prices (refer to [69,70,71]). Secondly, that rural zones are populous, with impoverished individuals; most of South Africa’s poor dwell in rural, rather than urban, settings [72,73]. Thus, advancements in agriculture are likely beneficial predominantly to the poor. Despite agriculture’s modest GDP portion, its influence on livelihoods is noteworthy, contributing 15% to 20% of employment opportunities, underscoring its crucial role as an employer, especially for the economically disadvantaged (see [71]). Moreover, subsistence farming serves as a cornerstone for the poor in South Africa, making up 20% and 8% of jobs in the lowest and next-lowest income levels, respectively (see [70,71]).

The usual modelling caveats apply to this work. The results are sensitive to assumptions made and accuracy of the data used. Ultimately, our findings’ robustness hinges on the model’s underlying assumptions. Firstly, the assumptions concerning the substitution elasticities between domestic and foreign good composites, as well as between skilled and unskilled workers, impact commodity and factor demands following shocks. The values used for these elasticities can result in either an overestimation or underestimation of the distributional effects. Secondly, the assumption of an endogenous labour supply that adjusts to income and price variations makes our conclusions sensitive to the selected income elasticities. As these values are sourced from previous studies performed using econometric techniques where available, they might exaggerate or diminish labour market results. Thirdly, the portrayal of domestic production and unpaid care work relies on assumptions about minimum consumption needs and time allocation. If these assumptions are inadequately specified, they can cause underestimation or overestimation of consumption and distributive effects. Fourthly, household behaviour, namely consumption choices, is modelled using an LES (Linear Expenditure System) function, which might not entirely reflect real-world realities. While these simplifications are necessary, and commonly used in applied modelling to operationalise the models, they may restrict the reliability of some micro-level results. To mitigate these limitations, sensitivity analyses were conducted on key parameters, and the results were evaluated for stability under different assumptions [13,64]. This research could be further extended by incorporating (i) more SDGs into the models, (ii) applying the modelling to a larger number of developing countries and (iii) the interlinkages between trade and climate change (Pérez-Peña et al., [74]). More broadly, we have assumed the government can effectively implement policy interventions and strategies suggested by the modelling. Future work should assess actual implementation, considering challenges such as coordination, policy harmonisation, effectiveness, budget adequacy, funding access, monitoring, evaluation, and sustainability of reforms. Understanding these issues is crucial for enhancing policy effectiveness and reducing poverty and hunger. Finally, a thorough analysis of rural and national development linkages requires comprehensive econometric studies on rural–urban and intersectoral factor mobility and production and consumption elasticities, possibly using panel data and advanced methods such as IV and SUR. This analysis is beyond this paper’s scope, due to data quality issues and the need for results that fit into a CGE framework.

5. Conclusions

The results illustrated above have been generated through a recursive dynamic CGE model, which is coupled with a household microsimulation model. The combination of these two modelling approaches enables the simultaneously assessment, in a model-consistent way, of the macroeconomic and distributional (poverty and inequality) effects of policy interventions. The findings, taken together, advocate for strategic interventions targeting agricultural expansion in rural areas, to get the country on track with its key development agenda pertaining to hunger and poverty SDGs.

The work makes three important contributions to the literature. First, the issue of rural development is studied from a perspective of sustainable development goals, including a recursive dynamic analysis of macro and micro variables, to determine milestones for achieving sustainable development goals. The second notable contribution arises from the potentially novel approach of placing the examination of quantified milestones within a general equilibrium framework specific to an African nation. This allows for the evaluation of how investments driven by the agriculture sector might facilitate the achievement of the SDGs related to hunger and poverty in South Africa. The third contribution highlights the importance of a combined policy approach to addressing hunger and poverty. Thus, South Africa is likely to get on track with its key hunger and poverty SDG agenda under a mixed policy strategy of agricultural investments, social assistance, and labour policies. This is important because, while from the literature on growth–poverty links it is evident that the structure of growth matters, it is clear that unless agricultural growth is combined with social assistance and skilling programmes in South Africa, hunger and poverty will not be eradicated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.E.M. and I.F.; methodology R.E.M. and I.F.; software, R.E.M. and I.F.; formal analysis, R.E.M. and I.F.; resources, R.E.M. and I.F.; writing—original draft preparation, R.E.M. and I.F.; writing—review and editing, R.E.M. and I.F.; project administration, R.E.M. and I.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study are available from corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Krueger, A.; Schiff, M.; Valdés, A. Agricultural Incentives in Developing Countries: Measuring the Effects of Sectorial and Economywide Policies. World Bank Econ. Rev. 1988, 2, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, M.; Valdés, A. The Political Economy of Agricultural Pricing Policy. In A Synthesis of the Economics in Developing Countries; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrik, D. Premature deindustrialization. J. Econ. Growth 2016, 21, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, X.; Hazell, P.; Thurlow, J. The Role of Agriculture in African Development. World Dev. 2010, 38, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiaensen, L.; Demery, L.; Kuhl, J. The (evolving) role of agriculture in poverty reduction: An empirical perspective. J. Dev. Econ. 2011, 96, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Assistance to Agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa: An IEG Review (English); World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/643971468198877047 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Cateia, J.V.; Bittencourt, M.V.L.; Carvalho, T.S.; Savard, L. Potential Economic Impacts of Agricultural Growth in Africa: Evidence from Guinea-Bissau. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2023, 55, 492–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukashov, A.; Thurlow, J. Promoting Regional Income Equity Under Structural Transformation and Climate Change: An Economywide Analysis for Senegal. Economic Systems. 2025. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0939362525000408?via%3Dihub (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Lofgren, H.; Diaz-Bonilla, C. MAMS: An Economy-Wide Model for Analysis of MDG Country Strategies. Technical Documentation, DECPG, World Bank. 2006. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/mdg_workshops/training_material/lofgren_and_diazbonilla_2006.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Maisonnave, H.; Mabugu, R.; Chitiga, M. Economywide consequences of attaining Millenium Development Goals in South Africa. Econ. Bull. 2015, 35, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Lofgren, H.; Cicowiez, M.; Diaz-Bonilla, C. MAMS—A Computable General Equilibrium Model for Developing Country Strategy Analysis. In Handbook of Computable General Equilibrium Modelling; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 159–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balma, L.; Ilboudo, W.; Ouattara, A.; Kabore, R.; Zerbo, K.; Kabore, S.T. Public Education Spending and Poverty in Burkina Faso: A Computable General Equilibrium Approach. Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fofana, I.; Mabugu, R.E.; Camara, A.; Abidoye, B. Ending Poverty and Accelerating Growth in South Africa, Through the Expansion of its Social Grant System. J. Policy Model. 2024, 46, 1090–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Moussaouil, M.; Arbia, A.; Yazidi, M. Impact of education on poverty in Morocco: A computable general equilibrium micro-simulation analysis. Afr. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2025, 1, 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Aarich, Z.; Imloui, M.; Kehaimi, H. Assessing the Role of Government Education Spending in Reducing Poverty: A CGE Model for Morocco. Afr. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2025, 1, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roson, R. General Equilibrium Effects of Investments in Education and Changes in the Labor Force Composition European. J. Dev. Stud. 2022, 2, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeshineh, A.; Woldeyes, F. The Economy-Wide Impact of Harnessing Human Capital Development and the Case of Ethiopia: A Dynamic Computable General Equilibrium Model Analysis. Economies 2025, 13, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley Merven, F.B.; Hughes, A.; Marquard, A.; Ranchhod, V. Estimating the economy-wide and redistributive impacts of mitigation in South Africa. Clim. Dev. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitiga, M.; Henseler, M.; Mabugu, R.; Maisonnave, H. The impact of the COVID 19 enforced lockdown and fiscal package on the South African economy and environment: A preliminary analysis. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2022, 27, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitiga-Mabugu, M.; Henseler, M.; Maisonnave, H.; Mabugu, R. Financing the Basic Income Support in South Africa Under Fiscal Constraints. World Dev. Perspect. 2025, 37, 100657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabugu, R.E.; Fofana, I.; Chitiga-Mabugu, M. Evaluating impacts of agriculture-led investments on sub-Saharan African countries’ poverty and growth. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisonnave, H.; Mamboundou, P.N. Agricultural Economic Reforms, Gender Inequality and Poverty in Senegal. J. Policy Model. 2022, 44, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidouemba, P.R.; Traoré, F.; Odjo, S.P. Imperfect competition and asymmetric welfare effects of global price and productivity shocks: A CGE model analysis for Senegal. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2025, 13, 2475160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Metternicht, G.; Wiedmann, T. National pathways to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A comparative review of scenario modelling tools. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 66, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbons, K.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Ambrosio, G.; Kulkarni, S.; Weber, E.; Zapata, V.; Daioglou, V.; Hof, A.F.; Zimm, C. A review of existing model-based scenarios achieving SDGs: Progress and challenges. Glob. Sustain. 2024, 7, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catenazzi, G. Advances in Techno-Economic Energy Modeling; ETH Zurich: Zürich, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, A.; Toro, F.; Reitze, F.; Jochem, E. Introduction to energy systems modelling. Swiss J. Econ. Stat. 2012, 148, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedenus, F.; Johansson, D.; Lindgren, K. A Critical Assessment of Energy-economy-climate Models for Policy Analysis. J. Appl. Econ. Bus. Res. 2013, 3, 118–132. [Google Scholar]

- Pollitt, H.; Barker, A.; Barton, J.; Pirgmaier, E.; Polzin, C.; Lutter, S.; Hinterberger, F.; Stocker, A. A Scoping Study on the Macroeconomic View of Sustainability, Final Report for the European Commission, DG Environment; Cambridge Econometrics: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pedercini, M. Development Policy Analysis in Mali: Sustainable Growth Prospects, Software Engineering and Formal Methods; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 447–463. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, G.M.; Hoffman, R.; McInnis, B.C.; Poldy, F.; Foran, B. A tool for strategic biophysical assessment of a national economy—The Australian Stocks and Flows Framework. Environ. Model. Softw. 2011, 26, 1134–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, P.-M.; Bréchet, T. Models for policy-making in sustainable development: The state of the art and perspectives for research. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 55, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland, V. Model comparison and robustness: A proposal for policy analysis after the financial crisis. In What’s Right with Macroeconomics? Solow, R.M., Touffut, J.-P.L., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Broadheath, UK, 2012; pp. 33–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bazilian, M.; Rogner, H.; Howells, M.; Hermann, S.; Arent, D.; Gielen, D.; Steduto, P.; Mueller, A.; Komor, P.; Tol, R.S. Considering the energy, water and food nexus: Towards an integrated modelling approach. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7896–7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T. The Transition to Sustainability: A Comparison of General Equilibrium and Space–Time–Economics Approaches; Tyndall Centre Working Paper; Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research: Norwich, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, S.C.; Timilsina, G.R. A review of energy system models. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2010, 4, 494–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravallion, M. Pro-Poor Growth: A Primer; World Bank Development Research Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ravallion, M. Inequality Is Bad for the Poor. In Inequality and Poverty Re-Examined; Jenkins, S., Micklewright, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon, F.; Spadaro, A. Les Modèles de Microsimulation dans l’Analyse des Politiques de Redistribution: Une Brève Présentation. Econ. Prévis. 2003, 160–161, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadaro, A. Microsimulation as a Tool for the Evaluation of Public Policies: Methods and Applications; Fundación BBVA: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, L., Jr. Econometric Policy Evaluation: A Critique. In Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1976; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Meagher, G.A. Forecasting Changes in Income Distribution: An Applied General Equilibrium Approach; Preliminary Working Paper No. OP-78; Centre of Policy Studies and The Impact Project, Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Devarajan, S.; Go, D.S. A Macroeconomic Framework for Poverty Reducing Strategy Papers (with an Application to Zambia); Unpublished; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Agénor, P.R.; Izquierdo, A.; Foffack, H. IMMPA: A Macroeconomic Quantitative Framework for the Analysis of Poverty Reduction Strategies; Unpublished; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J.; Horridge, M. The Doha Round, Poverty and Regional Inequality in Brazil. In Putting Development Back into the Doha Agenda: Poverty Impacts of a WTO Agreement; Hertel, T.W., Winters, L.A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan and World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Buddelmeyer, H.; Hérault, N.; Kalb, G.; van Zijll de Jong, M. Disaggregation of CGE Results into Household Level Results Through Micro-Macro Linkage: Analysing Climate Change Mitigation Policies from 2005 to 2030; Melbourne Institute Report No. 9; Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research: Melbourne, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hérault, N. Sequential Linking of Computable General Equilibrium and Microsimulation Models. Int. J. Microsimulat. 2010, 3, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.; Greer, J.; Thorbecke, E. A class of decomposable poverty measures. Econometrica 1984, 52, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South Africa (Republic of). Income and Expenditure Survey 2010/2011 [Database]; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon, F. The Growth Elasticity of Poverty Reduction: Explaining Heterogeneity Across Countries and Time Periods (English); World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. Poverty Trends in South Africa: An Examination of Absolute Poverty between 2006 and 2015; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators [Data File]. 2017. Available online: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Lewis, W.A. Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour. Manch. Sch. 1954, 22, 139–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaluwé, B.; Lemelin, A.; Robichaud, V.; Maisonnave, H. PEP-1-t (Single-Country Dynamic Version). PEP. 2013. Available online: https://www.pep-net.org/research-resources/cge-models (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Armington, P.S. A Theory of Demand for Products Distinguished by Place of Production. Int. Monet. Fund Staff Pap. 1969, 16, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdon, G.; Knight, J. Unemployment in South Africa: The Nature of the Beast. World Dev. 2004, 32, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdon, G.; Knight, J. Unemployment in South Africa, 1995–2003, Causes, Problems, and Policies. J. Afr. Econ. 2007, 16, 813–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.; Oswald, A. Estimating a Wage Curve for Britain 1973–1990; Working Paper 4770; National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER): Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, H.; Thorbecke, E. The impact of public education expenditures on human capital, growth, and poverty in Tanzania and Zambia: A general equilibrium approach. IMF Work. Pap. 2001, WP/01/106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Seventer, D.; Bold, S.; Gabriel, S.; Davies, R. A 2015 Social Accounting Matrix (SAM) for South Africa; SA-TIED Working Paper #35; SA-TIED: Pretoria, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- van Seventer, D.; Davies, R. A 2016 Social Accounting Matrix for South Africa with an Occupationally Disaggregated Labour Market Representation; UNU-WIDER: Helsinki, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lemelin, A.; Fofana, I.; Cockburn, J. Balancing a Social Accounting Matrix: Theory and Application (Revised Edition). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2439868 (accessed on 11 December 2013).

- Robinson, S.; Cattaneo, A.; El-Said, M. Updating and Estimating a Social Accounting Matrix Using Cross Entropy Methods. Econ. Syst. Res. 2001, 13, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabugu, R.; Fofana, I.; Chitiga, M. Pro-Poor Tax Policy Changes in South Africa: Potential and Limitations. J. Afr. Econ. 2015, 24, 73–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision [Database]. 2017. Available online: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- IMF. South Africa: 2024 Article IV Consultation; Country Report No. 25/28; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Economic Surveys: South Africa 2025; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. The World Bank in South Africa. Country Overview. 2022. Available online: www.worldbank.org (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Jafta, K.; Anakpo, G.; Syden, M. Income and poverty implications of COVID-19 pandemic and coping strategies: The case of South Africa. Afr. Growth Agenda 2022, 19, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp, A.; Pieterse, D.; Rycroft, J. Leveraging agriculture for growth: Lessons from innovative joint ventures and international best practice. Dev. S. Afr. 2020, 37, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauw, K.; MacDonald, S.; Punt, C. Agricultural efficiency and welfare in South Africa. Dev. S. Afr. 2007, 24, 309–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, N. The influence of policy on the role of agriculture in South Africa. Dev. S. Afr. 2004, 21, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.; Aliber, M. The Case for Restrategising Spending Priorities to Support Small-Scale Farmers in South Africa. Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, University of the Western Cape: Cape Town, South Africa. 2010. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242657948_The_Case_for_Re-Strategising_Spending_Priorities_to_Support_Small_Scale_Farmers_in_South_Africa (accessed on 25 January 2025).