Abstract

In this article, we present and assess the labor productivity changes that have occurred in Poland’s rural sectors since the country became a member of the European Union. The study is linked with the concept of convergence, which is one of the key goals of European integration. Convergence is when two or more things, ideas, or processes become similar. In an economic sense, convergence is the reduction of development disparities between countries, regions, or economic sectors. The aim of the work was to study the convergence of labor productivity in Poland’s rural economic sectors between 2003 and 2019. Since 2004, when Poland became a member of the European Union, the country has benefited from funds distributed via EU regional policies, aimed at economic and social cohesion, and attaining regional convergence of economic effects in the economies of rural areas. The theoretical background and research methodology of this article are based on the topic’s literature. Two forms of convergence (sigma convergence and beta convergence) were analyzed. Sigma convergence means a decrease in the dispersion and differentiation of labor productivity over time, and the essence of beta convergence is the faster development of less-developed regions, which results in catching up with the better-developed regions. The economic results of convergence processes, measured by the gross value added of agriculture, forestry, hunting, and fisheries, as well as the number of employed persons in these sectors, were obtained from the Local Data Bank. The distribution dynamics (of the gross value added per person working in a Polish rural sector) were assessed for 2003–2019 as well as for selected years and sub-periods. Statistical methods describing the state of differentiation of regions and the function of regression were used for analysis. The results are presented in figures and maps. The flows between the productivity groups of regions in five sub-periods were evidenced. The research confirmed the partial occurrence of labor productivity convergence in Poland’s rural sectors between 2003 and 2014—the period of a sizable flow of European Funds offered to rural areas in Poland, during the first two European Union financial perspectives. In the following years, the convergence process diminished due to different natural and socioeconomic reasons.

1. Introduction

One of the main goals of European integration is to reduce disparities of development between the member states and regions on their territories. At the initial stages of integration development, the differences between countries were small, because five founding countries (coming from the same cultural and civilization circles) were characterized by territorial cohesion and similar levels of economic development. These differences increased along with the successive expansions of communities, first in Denmark, Ireland, and the United Kingdom (1973), then in Greece (1981), Spain, and Portugal (1986), followed by the GDR (1990), Austria, Sweden, and Finland (1995), reaching large sizes after the fifth enlargement of the Union with countries in Central and Southern Europe. Admitting Ireland, Greece, Spain, and Portugal to the community resulted in the introduction of a cohesion policy and a new fund for strengthening territorial-, transport-, economic-, and social cohesion. The current process of expanding the European Union with Balkan countries raises the issue of socioeconomic differences in member states and their regions, creates a greater demand for resources, and complicates approaches to solving problems resulting therefrom. Therefore, it can be concluded that, as the European Union expands to new countries, the problems (regarding regional differentiations) are growing and the number of less-developed regions requiring assistance is increasing. An important feature of these regions is that they are agricultural regions and, thus, often have peripheral locations.

Equalizing development disparities at the levels of the countries/regions that are part of the European Union is called convergence, which, in a general sense, expresses the process of “bringing closer” and “reducing differences” between countries and regions, as well as the phenomenon of weaker areas catching up with more developed areas. Convergence is one of the objectives of European integration, development strategies, and policies [1,2]. It also pertains to agriculture and rural development, which are highly diversified in Polish regions.

The problem of regional variation and increasing the efficiency of resources directed at the development of less-developed regions was noticed in the mid-1980s, when actions were taken to strengthen structural policy instruments, reform the use of regional and structural funds, and introduce structural elements to the Common Agricultural Policy. Strengthening the regional aspects of the Common Agricultural Policy initiated by the MacSharry reform of 1992 was related to the new reform of agricultural funds carried out at that time and the strengthening of the second pillar of the Common Agricultural Policy, directed at the rural development program. The convergence of highly-diversified agriculture and other rural economic sectors can be recognized as an important development goal in Poland’s regional development strategy. Rural economic sector development can be measured by the productivity of economic production factors, among which, the most important is labor productivity.

The objective of the article was to assess the changes in the labor productivity levels in rural sectors (in administrative regions (voivodeships)) in Poland from 2003 to 2019. This should permit assessing the convergence of labor productivity in regions measured by the levels and dynamics of gross value added per person employed in the sectors of section A (agriculture, forestry, hunting, and fishing). It is expected that assessing the dynamics of productivity in regions throughout the whole period (and sub-periods) of the selected years will enable recognition of the convergence processes and their scales. The data for the study were obtained from the Local Data Bank in Poland. The theoretical background and research methodology were based on the selected positions of the literature studies. Two forms of convergence, sigma convergence, and beta convergence, were analyzed.

2. Convergence as the Objective of European Integration

Convergence is a process in which various (initially dissimilar) phenomena become similar, which means the disappearance of inequalities between entities, countries, or regions. The opposite of convergence is divergence, which means the deepening of differences. On economic grounds, the concept of convergence was formulated for the first time in the 1940s by Jan Tinbergen, although Schumpeter and Kondratiev [3] can also be regarded as the precursors of this phenomenon. The processes of socioeconomic development are characterized by uneven courses in time and space, which is expressed by the occurrence of convergence cycles (time system) and the formation of disparities in development (spatial system). The convergence phenomenon is related to the inequality of economic development in spatial systems measured by GDP per capita.

Other measures adapted to the characteristics of the studied phenomenon may also be used to determine the level of achieved development in the spatial system. Nowadays, it is acknowledged that there are considerable differences of opinion in this respect, i.e., excessive differences in the development of spatial systems are not favorable, which is the basis for opposing these processes, and pursuing policies that eliminate territorial developmental differences. This assumption is the basis for European integration. The preamble of the treaty of Rome (of 1957), which established the EEC, stipulated that the purpose of the functioning of the community is harmonious development, i.e., by reducing the differences existing between the various regions and the backwardness of the less favored regions. This provision has been reproduced in successive treaties as one of the most important measures within the framework of community policies, especially structural, regional, and cohesion policies. As integration expanded, these provisions were supplemented. The definition of the cohesion policy principles was of key importance in this respect, which involved the establishment of the Single European Act (SEA) in 1986 and joining relatively poorer countries joining the community, such as Greece, (and later) Spain, and Portugal. The SEA introduced new treaty provisions strengthening economic and social cohesion and the new Cohesion Fund, as well as the Treaty of Lisbon, a new category of territorial cohesion and social cohesion. The structural policy reform carried out in the mid-1980s brought a number of new rules, including multi-annual programming of expenditures for development purposes being allocated to problem areas. Therefore, the phenomena and processes of convergence were recognized as the official objectives of the structural policy, which also influenced the shape of other community policies, including the Common Agricultural Policy. During the 1989–1993 programming period, the EU’s structural policy objectives included provisions regarding support and structural adjustments of economically backward regions, restructuring of economic sectors in border regions and regions affected by industrial decline, adjustment of agrarian structures and support for rural areas as part of reforms of the Common Agricultural Policy implemented (since 1992). From 1988, when European structural funds were reformed, to 2013, there were almost EUR 900 million spent on cohesion and convergence. This was very important for countries of Eastern Europe that became members of the European Union in 2004 and 2007. These new EU members became the main beneficiaries of funds allocated in the frame of cohesion (regional) policy [4]. Research conducted on the effects generated by European funds in national economies of community member countries brought about, at that time, controversial results. Some studies suggested that the cohesion policy contributes to convergence on national and regional levels. Another study attempted to prove that this policy leads to divergence, particularly at the regional level [5].

In the 1994–1999 programming period, apart from development priorities aimed at strengthening the development of regions affected by difficulties in industrial development, there were new provisions on the advisability of supporting agricultural areas, facilitating the development and structural transformation of rural areas, and the promotion of development and structural adjustments in regions with low population densities. Between 2000 and 2006, when the fifth enlargement of the European Union with the Central and Eastern European and Southern European countries took place, three priorities were adopted, two of which were regional, i.e., promoting development and structural adjustment of regions whose developments were lagging, and supporting the economic and social convergence of areas facing structural problems.

In the 2007–2013 programming period, all three priorities of the structural policy included spatial aspects, but formally, the objective referred to as convergence was recognized as a priority. In principle, regional competitiveness and employment, as well as European territorial cooperation, served to accelerate development and eliminate regional differences and, thus, create and strengthen the convergence phenomenon. In 2000–2006, over 70% of structural funds were allocated to convergence; in the next financial perspective, this percentage increased to 80% [4]. The convergent-oriented objective covered the regions at the NUTS 2 level where the gross domestic product per capita, calculated on the basis of data for 2000–2002, was no more than 75% of the average GDP for EU-25. In 2001–2003, this threshold increased to 90%.

The focus of the cohesion policy for 2014–2020 shifted from a regionally oriented way of acting to a more problem-oriented one. Depending on the GDP level, regions are divided into categories of more developed regions, transition regions, or less-developed regions. The coverage of project costs from structural funds (from 50% to 80%) were developed on the basis of this division. The next policy objective was to increase the competitiveness of European regions and cities and to stimulate economic growth and employment. Out of the planned total amount of EUR 351.8 billion of the cohesion policy support, in 2014–2020, almost 52% was allocated to less-developed regions pursuing the convergence objective, about 15% to more developed regions, mainly pursuing the competitiveness objective, 10% for transition regions, and the rest, i.e., around 23%, for the outermost and sparsely populated regions, as well as for technical assistance.

The issue arises as to how agriculture (which is strongly dependent on natural conditions, has a spatial nature, and is characterized by lower productivity of labor than other economic sectors) is incorporated into the implementation of convergence. It seems that in the convergence of agriculture, there are two impact types. The first type consists of strong support for agriculture as an inefficient sector (in terms of income) and is characterized by low labor productivity through the Common Agricultural Policy. In this case, support for agriculture means support for the development of agricultural regions and, therefore, less-developed regions. This is particularly visible by supporting agriculture in areas with natural handicaps. Without funds directed to agriculture, the effects of managing these areas would be weaker. The second type of agricultural convergence support is related to rural area development, i.e., for new forms of non-agricultural activities and multi-purpose farming. Agriculture support, through internal market instruments and foreign trade, was introduced in the 1960s and maintained during various reforms of the Common Agricultural Policy until today. From the beginning, sectoral support for agriculture has been maintained (under the first pillar of the Common Agricultural Policy), and over time, it has been introduced and strengthened by the impact of structural changes in agriculture and enriching non-agricultural sectors of the rural economy through the introduction of the second pillar of the CAP supporting rural development.

A structural policy towards agriculture, initiated in the 1970s, was strengthened during the MacSharry reforms of 1992. This strengthening continued as a result of the reform introduced by Agenda 2000, the Luxembourg reform of 2003, the so-called Health Check of 2007, and the contemporary concept of the Common Agricultural Policy. The implementation of the Rural Development program in 2000–2006 and 2007–2013 made the model of the impact on rural areas by the Common Agricultural Policy similar to actions under the cohesion policy, which from the very beginning was clearly directed at the convergence of countries and regions.

Considering the general transformation of the objectives, solutions, and instruments of the Common Agricultural Policy, and transfers for agriculture resulting from this policy, it should be noted that the amount of support for agriculture and rural areas in countries and regions proceeds in accordance with the convergence processes. The question arises as to whether there is convergence in the amount of support in agricultural policies in selected countries [6] and whether the streams of support flowing through the Common Agricultural Policy contribute to the convergence processes of the level of development of agriculture itself in countries and regions of the European Union. Leaning toward the legitimacy of confirming such an impact, it should be noted that opinions doubting that the implementation of the Common Agricultural Policy is a factor in the convergence of agriculture, strengthening the concept of sustainable development of agriculture on a regional scale, are not isolated [7]. Questions were raised as to what were the results, the convergence, and divergence of the agricultural support regime in Poland (and other countries) by such authors as Czyżewski, Kułyk, Smędzik-Ambroży, and others [6,7,8,9]. They did not support the existence of absolute convergence but only some symptoms of it appeared in short periods or aspects of agricultural development. Research conducted in this paper addresses the existence and scale of the regional convergence of agriculture in Poland.

Regarding the spatial distribution of support through agricultural policy measures (similar to support for regions through a cohesion policy), there is a dilemma between the method ensuring greater competitiveness and efficiency and the objective of increasing convergence (less effectively but mitigating differences of development regionally). The convergence policy on the European Union scale, resulting in the equalization of GDP per capita (in the regions), did not bring about the strengthening of the Union’s competitiveness on an international scale [5]. Due to the economic crisis of the first decade of the 21st century and the failure of the Lisbon strategy, the assumptions of the Europe 2020 strategy paid more attention to the need to increase competitiveness. The priorities for 2014–2020, of structural, agriculture, and rural development policies, should provide a balance between ensuring competitiveness and regional convergence of agriculture and other rural sectors.

3. Materials and Methods

There is significant diversification in the production potential and economic results of agriculture in Poland’s regional arrangement [10,11]. The regional convergence of agriculture was investigated by many authors, such as Czyżewski and Kułyk [6], Brelik and Grzelak [12], Niewiadomski [13], Rezitis [14], Sapa and Baer-Nawrocka [15], Majchrzak and Smędzik-Ambroży [16], Nowak [17], Brath and Ferto [18], and others. It can be assumed that the level of production results achieved was significantly affected by the size of the EU funds directed to agriculture and rural areas under the Common Agricultural Policy and cohesion policy. The question is—does the inflow of such funds become a source of regional convergence of agriculture productivity and other natural sectors in rural areas?

In an attempt to assess the convergence of agriculture in Polish voivodeships from 2003 to 2019, and in light of the use of funds for supporting the development of agriculture and rural areas, it was necessary to settle methodical issues concerning three areas:

- Measuring the level of agricultural development;

- The level of resources from European funds used;

- The adopted definitions of convergence measurement methods.

This paper mainly focuses on the first and third areas.

The level of agricultural development is usually measured by comparing production results per unit of labor, per hectare of land used, or compared to the factor of capital used. While examining the convergence phenomenon, different categories defining the results of farming per head, per hectare, or other factors of production can also be used [15]. In the presented paper, the effects of farming and the level of rural development in voivodeships were determined by the gross value added per person employed (GVA/PE) in section A, which included agriculture, forestry, hunting, and fishing. The adoption of this measure was justified by the role of the labor factor in the production processes in rural sectors. This measure did not take into account the values generated in other sectors, especially in the sector of services provided in rural areas. We assume that this simplification will not distort the picture of convergence in rural areas. In addition, one should keep in mind that the convergence phenomenon and its level cannot only be equated with the adopted measurement indicators because it is a complex phenomenon, dependent on many other socioeconomic, technical, and business conditions [1,19].

Two basic definitions of regional convergence were adopted for the studies: sigma-convergence and beta-convergence. An attempt was also made to determine the correlation between the convergence of the effects of farming in rural areas and the level of inflow of EU funds to these areas.

Sigma (o) convergence defines the dispersion of the studied phenomenon over time. The variance and standard deviation were assumed as the measure of dispersion. The convergence phenomenon is demonstrated by the reduction of differences, i.e., the analyzed variables become assimilated. Regarding increasing differences, the divergence phenomenon will occur.

Beta (fi) convergence characterizes the relation between the pace of change in the level of development of sectors in section A and shows how much its initial values changed while respecting the principles (i.e., that convergence takes place when the growth rate in units, with a lower initial level, is higher than the average). As a result, the phenomenon of catching up with more developed regions by the weaker ones occurs. The occurrence of beta-convergence is considered essential for sigma-convergence [20].

Club convergence (or conditional convergence) occurs when regions with similar initial characteristics approach each other. According to this concept, the development level convergence takes place in groups, despite the polarization of the whole population remaining at an unchanged level.

The formula for the standard deviation of the logarithm of the gross value added per person employed in agriculture was used to verify o-convergence [17,21].

where

- δ(t)—dispersion of the GVA per person employed in agriculture in the group of all regions in year t,

- yi(t)—the GVA per person employed in agriculture in i-th region in period t,

- ȳ(t)—the average GVA per person employed in agriculture in period t.

The decrease in the value of the δ-convergence rate in the analyzed period indicates a decrease in the disproportion in the level of the analyzed feature. In the opposite situation, sigma-divergence will occur [22,23].

The regression of the GVA increase per person employed during the period under study in relation to the constant of the initial level of the formula was used to determine the absolute beta-convergence [24].

where

- y(t)—the GVA in the final year,

- y(0)—the GVA in the initial year,

- t + 1—number of periods,

- ε—random element.

β-convergence occurs when α_1 parameter is negative, while the closer the value is to −1, the greater the convergence. The classic analysis of convergence can be modified and enriched, e.g., through the application of alternative methods using a full distribution of the analyzed feature and its changes over time [20]. The results obtained from the calculations and estimations carried out can be presented in pictorial, numerical, and graphic terms.

4. Convergence of Labor Productivity in Poland’s Rural Sectors

Several factors influence the economic productivity of sectors and the total economy in different countries. This refers to agriculture and other rural sectors as well [25,26,27]. The productivity of agriculture and other natural sectors in rural areas, measured by the gross value added (GVA) per person employed (PE) in section A (agriculture, forestry, hunting, fishing) is strongly differentiated regionally in Poland. At the beginning of the studied period, the difference in the GVA/PE between the Podkarpackie region, which had the lowest ratio of PLN 2800/person in 2003, and the Zachodniopomorskie region, where it amounted to PLN 24,000/person, was PLN 21,000/person. So there was a 7.6-fold difference. In 2019, these differences deepened the Podkarpackie region labor productivity increased to only 4900 GVD/PE and in Zachodniopomorskie to 44,800 GVA/PE, which means a level nine-fold higher than in the Podkarpackie region. This difference in 2019 decreased slightly compared to 2014 when it was ten-fold. The two above-mentioned regions of Poland represent extremely different types of agriculture and extremely different natural conditions of functioning of the rural economy. On average, between 2003 and 2014, the productivity ratio in Poland amounted to PLN 18,700/person in four regions (Podkarpackie, Małopolskie, Lubelskie, Świętokrzyskie), it was below PLN 10,000/person, and in two (Zachodniopomorskie and Lubuskie) it exceeded PLN 30,000/person employed (Table 1). These two groups of regions are characterized by large differences in population density, as well as different agricultural structures, natural conditions, and rural area natures.

Table 1.

Gross value added per person employed in PLN thousand/person in 2003–2019 1.

In order to calculate the size of the convergence phenomenon, it is necessary to convert absolute values into relative values in individual voivodeships and compare them to the GVA/PE at the level of the whole country. This procedure allows comparing data for particular years without using the value-added deflator.

In 2003, the relative gross value added per person employed in agriculture (GVA/PE) reached the highest value in the case of Zachodniopomorskie Voivodeship (240.2%), Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodeship (191.1%) and Lubuskie Voivodeship (181.9%). The lowest value of the GVA/PE in 2003 was recorded by the Podkarpackie (27.7%), Małopolskie (50.9%), and Lubelskie Voivodeships (52.2%). The Łódzkie, Podlaskie, and Świętokrzyskie Voivodeships were also below the national average. In 2014, the highest value of relative GVA/PE was achieved by the same voivodeships as in 2003, i.e., Zachodniopomorskie Voivodeship (216.6%), Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodeship (199.2%), and Lubuskie Voivodeship (196.3%). The lowest value of GVA/PE in 2014 was recorded by the Podkarpackie (20.8%), Małopolskie (33.6%), Świętokrzyskie (55.1%), and Lubelskie Voivodeships (55.9%). The rate was also lower than the national average in the Śląskie Voivodeship. The Łódzkie and Podlaskie Voivodeships raised their rates to the level above the national average (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution dynamics of the gross value added per person working in relation to the country (in %) 1.

Taking into account the initial and final year, the number of voivodeships with productivity lower than the average increased from 6 to 7.

A comparison of individual years from the initial and final period may include a significant number of random elements; a more objective picture may be obtained by using averages from several years. When we use the three-year average, there were 7 voivodeships below the average in the initial period, whereas in the final period, the number of voivodeships decreased to 6. The average gross value added per person employed in relation to the country in 2003–2005 was: 120.5 ± 59.7 and increased in 2012–2014 to the level of 121.2 ± 60.4. The largest increase was recorded in the Mazowieckie Voivodeship (48.9 points), Pomorskie Voivodeship (33.4), and Podlaskie Voivodeship (31.9), and the largest decrease in Śląskie (−4.3), Dolnośląskie (−30.0) and Lubuskie Voivodeships (−21.4). The average increase was 0.7, i.e., 0.6% (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution dynamics of the gross value added per person working in relation to the country 1,2.

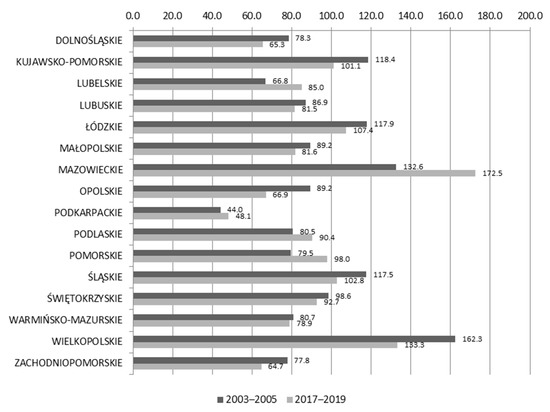

The median of change was −3.4%, which indicates that half of the studied voivodeships recorded a drop in the analyzed indicator by 3.4 pp, from 122.1% to 117.6%. In eight voivodeships, there was a reduction in the GVA/PE in relation to the national average, and in eight, there was an increase in this indicator. In relative terms, the largest relative regress in relation to the average was recorded in the Śląskie (−36.8), Małopolskie (−34.5), and Podkarpackie Voivodeships (−30.6), while the largest increase was recorded in the Mazowieckie (+42.6), Pomorskie (24.6), and Podlaskie Voivodeships (+39.9) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution dynamics of the gross value added per person working in relation to the country (%). (Own study, based on the Local Data Bank).

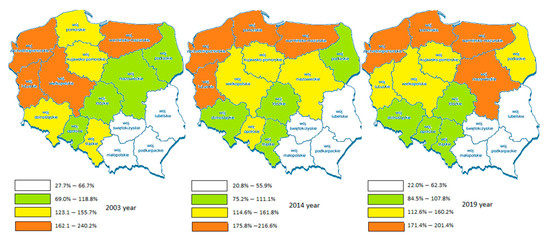

Distribution of the relative gross value added per person working in the initial and final period of the analysis divided into quartiles is presented on two consecutive maps (Figure 2). In 2003, groups of voivodeships forming individual quartiles created complexes that were relatively easy to interpret. The first complex includes the area of southeastern voivodeships of Poland, with traditional, fragmented agriculture, in which the GVA/PE was at a low level, from 28% to 67% of the national average. The second complex includes four voivodeships located diagonally from the southwest to the northeast of Poland. In these areas, the level of the GVA/PE was close to the national average (69–119%). The complex exceeding the average income between 123% and 156% consists of three separate groups of voivodeships: Pomorskie and Kujawsko-Pomorskie, Dolnośląskie, and Śląskie. In this period, the highest productivity of labor was demonstrated by the Zachodniopomorskie, Lubuskie, Wielkopolskie, and Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodeships. This complex includes voivodeships that had a large share of state-owned farms in the past.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the relative gross value added per person employed in section A (agriculture, forestry, hunting, and fishing) for voivodeships in 2003, 2014, and 2019. (Own study, based on the Local Data Bank).

In 2014, the smallest changes (slight decreases) occurred in the southeastern voivodeships. In 2003, three out of four voivodeships with the highest relative values of the GVA/PE maintained their positions in the fourth group constituting 25% of voivodeships with the highest levels of labor productivity. These were the following voivodeships: Zachodniopomorskie (216.6%), Warmińsko-Mazurskie (199.2%), and Lubuskie (196.3%). The GVA/PE in the Wielkopolskie Voivodeship decreased by −8.1 pp, and as a result, this region moved to the third group, and its place was taken by the Pomorskie Voivodeship, which recorded an increase of +30.2. Significant shifts occurred in two central quartiles. The Łódzkie and Podlaskie Voivodeships remained in the second group, the Opolskie and Mazowieckie Voivodeships advanced from the second to the third group, while the Śląskie and Dolnośląskie Voivodeships recorded the highest decrease in the relative GVA/PE, on average by −51.3 pp, which caused them to fall from the third to the second category (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of the relative gross value added per person employed in section A (agriculture, forestry, hunting, and fishing) for voivodeships (in %) in the initial and final years of the analysis 1.

In 2019, all four voivodeships, which in 2003 belonged to the first complex, kept their lowest positions in labor productivity. Two out of four voivodeships with the highest GVA/PE values in 2003 kept their positions in group four, which constituted 25% of voivodeships having the highest labor productivity. These were the voivodeships: Zachodniopomorskie (201%) and Warmińsko-Mazurskie (185.5%). The GVA/PE in Lubuskie and Wielkopolskie decreased by −21.7% pp and −8.3 pp parallelly, which resulted in moving these regions to the third group. Their earlier positions were replaced by Pomorskie and Mazowieckie Voivodeships, which noted spectacle increases in labor productivity. Łódzkie and Opolskie Voivodeships remained in the second group, Podlaskie advanced from the second to the third group, while Dolnośląskie and Śląskie noted the highest decrease by −48,3 pp from the third to the second group (Table 4).

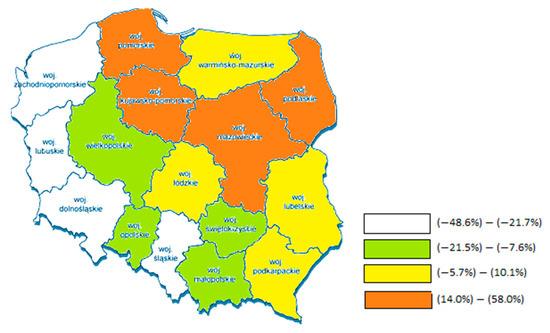

Changes in the distribution, which occurred in the level of the GVA/PE between 2003, 2014, and 2019 are shown in Table 4 and Figure 3. In the first sub-period, relatively strong losses in productivity in the 17–58% range occurred in the Małopolskie, Śląskie, Dolnośląskie, and Zachodniopomorskie Voivodeships. These are regions with different agricultural characteristics. In the second sub-period, comparatively strong falls in productivity (between 21 and 49%) were noted in the western regions: Zachodniopomorskie, Lubuskie, Dolnośląskie, and Śląskie Voivodeships. The highest increase instead, on the level of 14–58%, was noted in Pomorskie, Kujawsko-Pomorskie, Mazowieckie, and Podlaskie Voivodeships. To some extent, this was due to the restructuring and privatization process in the state farm sector having a high share in agriculture in these regions.

Figure 3.

Change in the distribution of the relative gross value added per person employed in section A (agriculture, forestry, hunting, and fishing) for voivodeships in 2003–2019. (Own study, based on the Local Data Bank).

Between 2003 and 2014, there was an average positive change in the relative GVA/PE by +1.2 pp. The highest increase was achieved in the Mazowieckie Voivodeship (+45.6 pp), Podlaskie Voivodeship (+40.5 pp), Kujawsko-Pomorskie Voivodeship (+30.4 pp), and Pomorskie Voivodeship (+30.2 pp). For half of the voivodeships, in 2003–2014, the analyzed rate decreased. Relatively small movements, both down and up, took place in the following voivodeships: Opolskie, Podkarpackie, and Wielkopolskie (slight decrease) and Lubelskie and Warmińsko-Mazurskie (slight increase). The trends described in this period continued in the following years. These changes are illustrated in Figure 3. In 2003–2019, the average decrease of relative GVA/PE at the level of 3.8 pp was noted as a result of changes in six voivodeships. The highest increases of these figures were in voivodeships: Mazowieckie, (+58 pp), Podlaskie (+436 pp), Pomorskie (+25.8 pp), and Kujawsko-Pomorskie (+14.0 pp). In ten regions, this coefficient decreased in 2003–2019. Comparatively small changes were noted in Podkarpackie, Warmińsko-Mazurskie, and Świętokrzyskie (small decreases) and Łódzkie, Lubelskie, Kujawsko-Pomorskie Voivodeships (slight increases).

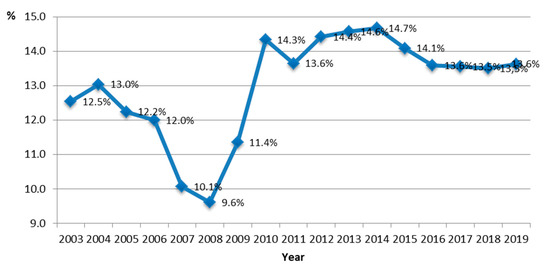

Figure 4 shows the analysis of sigma-convergence/divergence for all regions using the course of changes of the coefficient of variation of the relative value added per person employed in section A in 2003–2019. Four phases can be distinguished from the course of the curve, illustrating changes in the coefficient of variation in the analyzed period: convergence, divergence, and stagnation. Initially, in the analyzed period between 2003 and 2008, the coefficient of variation decreased from 12.5% to 9.6%, which coincides with the first stage of support for Polish agriculture from the EU budget. This period can be treated as the time in which the convergence of voivodeships occurred. In the second stage (2008–2010), an increase in the coefficient of variation of the GVA/PE from 9.6% to 14.3% occurred. This proves the deepening of differences between regions, as a result of which, within two years, the differences between the examined voivodeships increased to a level exceeding the initial value from the period before Poland acceded to the EU. This trend resulted partly from the global financial crisis in 2007–2010. The third period under consideration, namely 2010–2014, except for 2011 when a positive change occurred, was characterized by stability at a high level of variability of 14.3–14.7%. This period can be called a period of “stagnation”—or a time in which the differences between the regions did not increase, but also did not decrease. The next phase of convergence occurred in 2014–2016 (with a decrease from 14.7% to 13.6%); the next period of stagnation returned in the fourth period, at the level of 13.5–13.6%. Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Sigma-convergence analysis of the gross value added per person employed in section A (agriculture, forestry, hunting, and fishing) for voivodeships (Own study, based on the Local Data Bank).

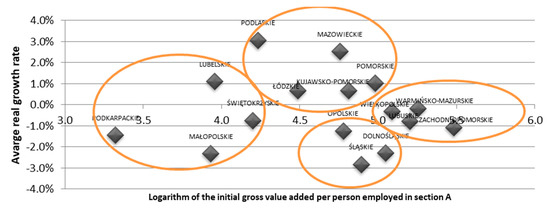

Beta (fi) convergence will be evaluated further in this paper. Figure 5 presents the characteristics concerning the level of dependence between the average productivity growth rate in individual voivodeships (vertical axis) and their initial levels (horizontal axis). It can be noticed that the poorest regions of fragmented agriculture (Podkarpackie, Małopolskie, and Świętokrzyskie Voivodeships), as well as the industrialized regions (Śląskie and Dolnośląskie), recorded relatively low growth, not exceeding 4%. On the other hand, Zachodniopomorskie, Wielkopolskie, and Lubuskie Voivodeships recorded average increases of 4–7%. The Podlaskie and Mazowieckie Voivodeships showed the highest increases, while the Śląskie and Małopolskie Voivodeships showed the lowest. The above analysis does not indicate the occurrences of absolute beta-convergence of voivodeships in 2003–2014. Regions with lower labor productivity did not develop faster than the regions with medium and high levels of GVA/PE.

Figure 5.

Beta-convergence analysis of the gross value added per person employed in section A (agriculture, forestry, hunting, and fishing) for voivodeships in 2003–2019 (own study, based on the Local Data Bank).

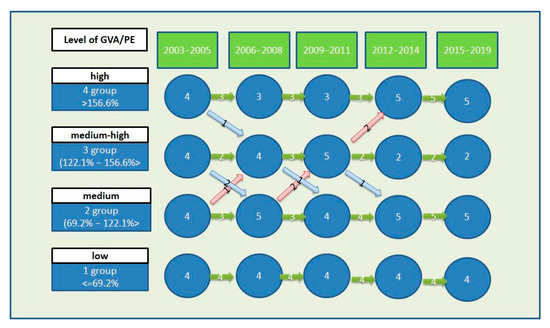

In order to eliminate short-term randomness and highlight the key change tendencies over time, the entire research period was divided into four three-year sub-periods. For each period, the arithmetic mean of the relative gross value added per employee in section A was calculated, and then the limits of the ranges were determined creating four equipotent groups. Four southeastern voivodeships of fragmented agriculture (Podkarpackie, Małopolskie, Lubelskie, and Świętokrzyskie) in each of the four stages remained in the first group, in which the average relative gross value added per employee in section A did not exceed 69.2% of the national average. After the first period, the Wielkopolskie Voivodeship shifted from the fourth to the third category and the Kujawsko-Pomorskie and Śląskie Voivodeships moved from the third to the second category. At the same time, the Mazowieckie Voivodeship shifted from the second to the third category. This period, despite the lack of a major increase in productivity of the poorest voivodeships under the influence of lower productivity of the richest ones (belonging to the third and fourth group), proves the regional convergence.

The next analyzed period (2009–2011) brought a decrease for the Dolnośląskie Voivodeship from the third to the second category and an increase in the Kujawsko-Pomorskie and Opolskie Voivodeships from the second to the third category. In this period, the number of regions with the lowest and highest productivity did not change, while the number of the second group increased and the number of the third group decreased. In the last analyzed period, the third group, the largest in 2009–2011, with a relatively high level of productivity, was broken down. The Opolskie Voivodeship returned to the second category, while the Pomorskie and Mazowieckie Voivodeships advanced to the fourth—the highest category. As a result, a group of five voivodeships with the highest levels of GVA/PE was formed: the Zachodniopomorskie, Warmińsko-Mazurskie, Lubuskie, Pomorskie, and Mazowieckie Voivodeships. Two voivodeships were at the medium-high level of productivity: Kujawsko-Pomorskie and Wielkopolskie. The group with an average GVA/PE included five voivodeships. The category with the lowest productivity was invariably represented by the voivodeships of southeastern Poland. During three transitions between the distinguished periods, five falls to the lower category, and five increases were observed. The Mazowieckie Voivodeship strengthened the most—in 2003–2005 it belonged to the second category, advanced to the third category in 2006–2008, and in the last analyzed period moved to the fourth group with a high level of productivity. In 2006–2008 and 2009–2011, increases and decreases in productivity balanced. In this period, from 2006 to 2011, the second and third groups close to the average included a total of nine voivodeships (56.3%). With the stabilization of the number of voivodeships in the first group with the lowest labor productivity, the number of voivodeships with the highest GVA/PE ratio was limited. This may support the occurrence of rather undesirable region convergences through a relative reduction in labor productivity in the group of the most productive regions. In the period from 2008 to 2014, layered convergence occurred. This means that the regions in the middle groups with the GVA/PE ratio above and below the national average moved up. This resulted in an increase in the number of regions with higher productivity. With the stabilization of the group of regions with low labor productivity, the group with productivity above the national average included seven voivodeships, while the group below the average—nine voivodeships. This situation stabilized in the 2005–2019 period. A decrease in the number of regions close to the average in the group of regions with above average GVA/PE and an increase in the number of voivodeships with a high level of productivity is an indication that the phenomenon of the club convergence of regions occurred (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The flow of regions according to the relative distribution of the gross value added per person employed in section A (agriculture, forestry, hunting, and fishing) for voivodeships in four sub-periods in 2003–2014 (Own study, based on the Local Data Bank).

While analyzing the flows of voivodeships between individual groups in the distinguished periods, it can be noticed that in 2003–2005, convergence as a result of lowering productivity in groups with high and medium-high productivity, dominated. In 2006–2011, this earlier trend was offset by a larger flow from group two to group three. In 2009–2014, regarding the flows of voivodeships, there was a predominance of flows from the medium-high group to high productivity and from the medium-high group to the average level of productivity. We should mention that evident changes in labor productivity in regions occurred mainly in the period between 2003 and 2014. In the last years, a kind of stabilization may be observed. The reason for this stabilization may be linked to the diminishing effects of agriculture and rural area support in the frame of the Common Agricultural Policy. In the entire period, a group of four voivodeships with the lowest productivity (group 1) was characterized by a clear stagnation.

Based on the analysis of data included in Figure 6 and Table 5, it can be said that changes in the productivity of agriculture in the voivodeship in Poland in 2003–2014 are difficult to interpret unequivocally. It can be concluded that there is a clear stratification of voivodeships in terms of changes in productivity. Two groups of regions, the fourth group with high productivity and the second group with medium productivity, increased their number from four to five. The second group of regions with medium-high productivity decreased from four to two regions through outflow to both higher and lower productivity groups. Two groups of average productivity showed typical features of club convergence. The behaviors of voivodeships in the first group, with low levels of productivity, were similar. Changes that took place in this group were small and occurred within the group, which prevented them from moving to a higher level of productivity. Therefore, this group did not show the expected tendency to catch up with regions with higher productivity. These trends occurred in the periods between 2003–2005 and 2012–2014 and were stabilized in the next period until 2017–2019 (Figure 6 and Table 5).

Table 5.

Region flows between four groups of agricultural productivity between the initial and final period of 2003–2019 1.

5. Conclusions

The reduction of development disparities between countries and regions is one of the most important general objectives of European integration. The funds of the community budget directed to individual countries and regions through various European funds and policies serve this purpose. The task of these policies and funds is to support the development of countries and regions that are lagging, which may result in the convergence phenomenon. One of the most supported sectors of the economy is agriculture and other forms of farming in rural areas. In Poland, rural sectors of all regions are differentiated and benefit from the support of the Common Agricultural Policy and cohesion policy. We assume that the scope of EU support for agriculture, forestry, hunting, and fishing, and the effects of this support in Polish regions are different across Poland, and these may constitute an important factor for convergence. In this article, we attempt to reveal the existence of the convergence in labor productivity of rural sectors between all 16 regions in Poland. We used both sigma and beta convergence formulas.

Both the phenomenon of sigma-convergence, indicating a reduction in disproportions and differences in the level of development, and the phenomenon of beta-convergence, indicating a faster rate of development of rural sectors in less-developed regions (catching-up phenomenon), were subjected to studies. Studies showed that in 2003–2008, the coefficient of variation in the level of development of rural sectors decreased. This means the occurrence of the phenomenon of sigma-convergence in this period, as a result of faster development of less-developed regions. On the other hand, in 2008–2010, the coefficient of variation increased and stabilizes at the high level of 25–27% in 2010–2014. The next phase of convergence took place in 2014–2016 (the index decreased from 14.7% to 13.6%); in the last period (from 2016 to 2019) the level of labor productivity went into stagnation. This means that in the final years of the analyzed period, the differences between regions did not deepen (Figure 5).

The analysis of beta-convergence showed that the poorest regions, especially the regions of fragmented agriculture (Małopolskie, Podkarpackie, and Świętokrzyskie), recorded relatively low increases in productivity (up to 4%), while the Zachodniopomorskie, Warmińsko-Mazurskie, Wielkopolskie, and Lubuskie Voivodeships, with favorable agrarian structures, achieved increases of 4–7%. The lowest growth rates were reached by the Śląskie and Dolnośląskie Voivodeships, while the highest by the Mazowieckie, Podlaskie, Pomorskie, and Kujawsko-Pomorskie Voivodeships (Figure 5). Considering these research results, it is hard to see the existence of permanent regional convergence of agricultural development and other rural sectors measured by the level of labor productivity. Periods of convergence occurrence are interwoven with the divergence phenomenon or lack of changes.

One reason for the lack of a permanent, clearly visible phenomenon of convergence with a constant inflow of EU funds may be the significant differences in labor productivity in agriculture resulting from structural differences in agriculture and other rural sectors in the Polish regions. The flow analysis of individual regions between productivity groups confirmed the occurrence of different processes within four groups (clusters) of voivodeships (Table 5). Research showed the stabilization of labor productivity in the group of southeastern voivodeships and stratifications consisting of limiting the group of voivodeships representing medium-high levels of productivity in favor of groups of voivodeships with high and medium levels of productivity. Strengthening of the two groups of voivodeships with high and medium levels of productivity and stabilizing the group with low productivity indicates the occurrence of the so-called club convergence. This may be the reason for diversification and a more regionally-oriented policy for agriculture and rural development in Poland.

The authors are aware that this article has some shortcomings and limitations. The subject of the article focused on presenting the changes in labor productivity as a measure of rural sector development. Labor productivity in agriculture, forestry, and fishery may only be recognized as measures of sector efficiency. The productivity of land and capital also influences the trends in overall productivity and the scale of convergence or divergence in regions. Evidenced trends must be linked not only to the flow of European funds to rural sectors but also to the natural conditions and structural features of the regions. This requires, however, further studies and additional analyses. There is also a need to clarify the relations between sigma and beta convergences as measuring concepts in assessing the development trends in agricultural and rural development in regions and countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and A.S.; methodology, M.A. and A.S.; software, A.S.; validation, A.S.; formal analysis, M.A.; investigation, M.A.; resources, A.S.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.A.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, M.A.; project administration, M.A. and A.S.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by John Paul II University of Applied Sciences in Biala Podlaska, Poland.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adamowicz, M.; Szepeluk, A. Regional convergence of labour productivity in rural sectors in the context of funds obtained for agriculture from the European Union. Probl. Agric. Econ. 2018, 365, 3–31. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowicz, M. European funds for rural areas and regional convergence in agriculture in Poland. Econ. Reg. Stud. 2019, 12, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churski, P. Czynniki rozwoju regionalnego w świetle koncepcji teoretycznych. Zesz. Nauk. WSHE We Włocławku Nauk. Ekon. 2005, 19, 13–31. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Głodowska, A. Znaczenie konwergencji w aktualnej i przyszłej polityce strukturalnej Unii Europejskiej. Nierówności Społeczne Wzrost Gospod. 2012, 24, 174–185. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bodrin, M.; Canova, F. Inequality and convergence in Europe’s regions: Reconsidering European regional policies. Econ. Policy 2021, 16, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Czyżewski, A.; Kułyk, P. Konwergencja czy dywergencja mechanizmów wsparcia sektora rolnego. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW Probl. Rol. Swiat. 2009, 23, 41–51. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Smędzik-Ambroży, K. Konwergencja czy dywergencja rolnictwa w Polsce w latach 2004–2011. In Proceedings of the IX Kongres Ekonomistów Polskich, Warszawa, Poland, 28–29 November 2013. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Czyżewski, A.; Matuszczak, A. Konwergencja czy dywergencja wydatków krajowych i unijnych w budżecie rolnym Polski po 2010 roku. Rocz. Nauk. Stowarzyszenia Ekon. Rol. Agrobiz. 2015, 17, 24–28. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kułyk, P.; Augustowski, Ł. Globalna konwergencja czy globalna dywergencja mechanizmów wsparcia rolnictwa. Rocz. Nauk. Ekon. Rol. I Rozw. Obsz. Wiej. 2017, 104, 44–53. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, J. Zróżnicowanie regionalne potencjału produkcyjnego oraz wyników produkcyjno-ekonomicznych indywidualnych gospodarstw rolnych w Polsce z uwzględnieniem wybranych typów rolniczych. Probl. Rol. Swiat. 2006, 15, 26–35. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kamińska, A.; Nowak, A. Zastosowanie analizy skupień do badania zróżnicowania regionalnego potencjału produkcyjnego rolnictwa w Polsce. Rocz. Nauk. SERiA 2014, 16, 26–35. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Brelik, A.; Grzelak, A. The evaluation of the trends of Polish farms incomes in the FADN regions after the integration with the EU. J. Agribus. Rural. Dev. 2011, 20, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Niewiadomski, K. Ocena konwergencji rolnictwa w Polsce w latach 1998–2005. Wieś Rol. 2009, 144, 49–62. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Rezitis, A.N. Agricultural productivity and convergence. Eur. United States Appl. Econ. 2010, 42, 1029–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapa, A.; Baer-Nawrocka, A. Konwergencja wydajności pracy w rolnictwie a intensywność handlu rolno-żywnościowego w amerykańskich ugrupowaniach handlowych. Gospod. Nar. 2014, 3, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrzak, A.; Smędzik-Ambroży, K. Procesy konwergencji dochodów gospodarstw rolnych w Polsce po 2006 roku. J. Agribus. Rural. Dev. 2014, 31, 89–98. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, A. Przestrzenne zróżnicowanie zmian produktywności całkowitej rolnictwa w Polsce w latach 2005. Rocz. Nauk. SERiA 2017, 19, 131–136. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Barath, L.; Ferto, L. Productivity and convergence in European agriculture. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 68, 228–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łaźniewska, E.; Górecki, T.; Chmielewski, R. Konwergencja Regionalna; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2011. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Wójcik, P. Dywergencja czy konwergencja: Dynamika rozwoju polskich regionów. Stud. Reg. Lokal. 2008, 32, 41–60. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Fiedor, B.; Kociszewski, K. Ekonomia Rozwoju; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego: Wrocław, Poland, 2010. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Barro, R.J.; Sala-i-Martin, X. Convergence. J. Political Econ. 1992, 100, 223–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaga, K. Konwergencja Gospodarcza w Krajach OECD w Świetle Zagregowanych Modeli Wzrostu; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2004. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Próchniak, M.; Rapacki, P. Beta and sigma Convergence in the Post-Socialist Countries. Bank Kredyt 2007, 8–9, 42–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hamulczuk, M. Total factor productivity convergence in the EU agriculture. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference Competitiveness of Agro-Food and Environmental Economy, 12-13th November 2015, Bucharest, Romania; pp. 34–43.

- Markowska-Przybyła, U. Konwergencja regionalna w Polsce w latach 1999–2007. Gospod. Nar. 2010, 244, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.; Kamińska, A.; Różańska-Boczula, M. Przestrzenne zróżnicowanie potencjału produkcyjnego rolnictwa w Polsce. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu Ekon. 2014, 347, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).