Abstract

Background/Objectives: Obesity affects over 40% of solid organ transplant candidates, increasing graft complications. Bariatric surgery remains underutilized in this population due to safety concerns. We sought to evaluate predictors of graft success among patients with and without a history of bariatric surgery. Methods: We utilized the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (2015–2020) to identify adult solid organ transplant recipients with or without a history of bariatric surgery. Propensity score matching (2:1) was performed. The primary outcome was a composite of graft-related complications, including acute or chronic rejection, graft failure, and organ-specific transplant complications. Results: Among 196,871 transplant recipients, 2670 (1.4%) had a bariatric surgery history. After matching, 2530 bariatric surgery patients (age 55.6 ± 11.3 years, 37.5% female, 29.0% obese) were compared with 4817 controls (age 56.3 ± 13.9 years, 36.0% female. 29.1% obese). Bariatric surgery patients had significantly lower composite graft complications (7.7% vs. 10.5%; p < 0.001), driven by reductions in chronic graft rejection (2.1% vs. 3.1%; p = 0.01), kidney complications (6.2% vs. 8.4%; p < 0.001), and pancreas complications (0.2% vs. 0.6%; p = 0.004). Multivariate analysis showed bariatric surgery was independently associated with 23% reduced odds of graft complications (OR 0.77; 95% CI 0.61–0.96; p = 0.02). Conclusions: Bariatric surgery was independently associated with reduced graft-related complications in solid organ transplant recipients, supporting its role in improving post-transplant outcomes. Future studies should define the optimal timing of bariatric surgery relative to transplantation.

1. Introduction

There is still notable stigma concerning bariatric surgery in solid organ transplant candidates and recipients [1]. This stigma is rooted in long-standing concerns regarding excessive perioperative risk and doubts about long-term graft safety. These perceptions have historically made both transplant teams and patients hesitant to consider bariatric surgery as part of routine transplant care.

Patients who are candidates for bariatric surgery are typically more prone to a range of comorbidities, including adipose tissue hyperplasia and dysfunction, metabolic dysregulation, and multiple-organ failure [2,3]. This atypical collection of immune mediators, in addition to adipose tissue hypertrophy damaging capillaries and compromising blood supply, has been mechanistically proven to place bariatric surgery candidates at increased risk of hypoxia, impaired wound healing, and graft infection [4]. These patients also tend to have a more complex body anatomy, and therefore challenges with patient positioning and intraoperative imaging significantly increase operative time [5]. These risk factors often contribute to physician hesitation in offering organ transplantation, despite knowing the heightened health risks associated with unmanaged obesity and organ failure [6,7]. As a result, there is a significant mismatch between the need for surgery in bariatric patients and its availability. Studies have found that among patients awaiting kidney transplantation (KT), their transplant probability declines progressively with increasing body mass index (BMI) [8].

Bariatric surgery is a viable solution to improve transplant outcomes. Weight-loss surgery is proven to mitigate the chronic inflammatory state that causes adverse surgical outcomes and the risk of organ rejection in patients with obesity [9]. Recent studies demonstrate that concurrent liver transplantation and sleeve gastrectomy (SG) in patients who might otherwise not be eligible for transplant is successful in preventing recurrent obesity and mitigating graft failure [10]. However, most of these studies have been performed in sample sizes limited to single centers or without a detailed identification of United States (US) solid organ recipients.

Using a large, national cohort with propensity score–matched controls, we therefore sought to assess graft-related outcomes and identify predictors of graft-related complications in solid organ transplant recipients who did or did not undergo subsequent bariatric surgery. By providing contemporary, real-world estimates of risk, our goal is to challenge persistent stigma and more clearly define the role of bariatric surgery in the care of transplant candidates and recipients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Study Population

This retrospective cohort study evaluated transplant-related outcomes in solid organ transplant recipients, comparing those who underwent bariatric surgery with matched controls who did not undergo bariatric surgery. We utilized the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database, which is the largest publicly accessible, all-payer database of inpatient hospitalizations in the United States. The analysis encompassed admissions between 2015 and 2020. The NIS is part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) managed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and includes data from approximately 20% of US hospitals, encompassing over 7 million hospitalizations each year. Each record is assigned a discharge weight that allows for national estimates, yielding an annual representation of approximately 35 million hospital discharges across the United States.

This database provides detailed demographic, clinical, and hospital-level information, including age, sex, race, household income quartile by ZIP code, hospital region, total charges, and length of stay (LOS). Diagnoses and procedures were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification and Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-CM/PCS).

2.2. Study Group Definitions

Two study groups were defined based on bariatric surgery history following solid organ transplantation. The exposure group (solid transplant plus bariatric surgery) included adult patients with a documented solid organ transplant status code (Z94.0, Z94.1, Z94.2, Z94.4, or Z94.83) and a concurrent diagnosis code indicating history of bariatric surgery (Z98.84). The control group (solid transplant only) included adult patients with a documented solid organ transplant status code, but without any history of bariatric surgery. Bariatric surgery history was identified using ICD-10-CM diagnosis code Z98.84, which captures patients with a personal history of weight-loss surgery including Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), sleeve gastrectomy (SG), adjustable gastric banding, biliopancreatic diversion (with or without duodenal switch), and one-anastomosis gastric bypass. The NIS database does not provide procedure-specific codes that would allow stratification by individual bariatric surgery type; therefore, our analysis encompasses all bariatric procedures collectively.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Our study included adult patients (≥18 years) with a diagnosis code indicating solid organ transplantation status (kidney, liver, heart, lung, or pancreas).

Exclusion criteria included hospitalizations with incomplete demographic data (missing age, sex, or income information), records with missing outcome variables, and patients younger than 18 years. To ensure independence of observations, interhospital transfers were also excluded.

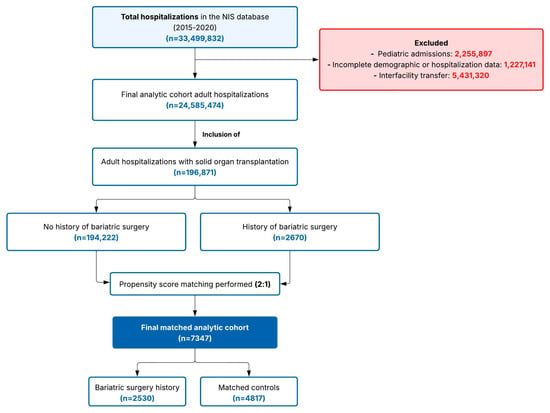

Notably, we did not exclude patients with obesity at admission who also had a history of bariatric surgery. This decision was made to avoid introducing selection bias, as excluding such patients would assume that all individuals remain obese following bariatric surgery throughout all subsequent hospitalizations, which does not reflect the clinical reality of variable weight trajectories post-bariatric surgery. Obesity status (E66.x), however, was considered in the propensity match, achieving perfect balance between the groups, to reduce the bias the condition might introduce. A detailed flow diagram of hospitalization-type selection is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram showing participant selection and propensity score matching process. Selection of study participants from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (2015–2020). In sum, 196,871 adult solid organ transplant hospitalizations were identified: 2670 had bariatric surgery history and 194,222 did not. After 2:1 propensity score matching on key covariates, the final cohort included 7347 patients: 2530 with bariatric surgery history and 4817 matched controls. Abbreviation: NIS, Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

2.4. Covariates

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics included age, sex, race/ethnicity, income quartile by ZIP code, hospital region, and organ type. Comorbidity burden was assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). Specific comorbidities analyzed included coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, liver disease, diabetes, obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, depression, alcohol use, tobacco use, any malignancy, acute kidney injury, urinary tract infection, sepsis, and opportunistic infection. Hospital-level outcomes included LOS and total hospitalization charges.

2.5. Outcomes

Primary outcome: Composite graft-related complications, including acute graft rejection, chronic graft rejection, graft failure, cardiac allograft vasculopathy, or organ-specific transplant complications (kidney, heart, lung, liver, and pancreas).

Secondary outcomes: Individual graft-related complications (acute graft rejection, chronic graft rejection, graft failure, and cardiac allograft vasculopathy), organ-specific transplant complications (kidney, heart, lung, liver, and pancreas), hospitalization burden defined by LOS and total hospitalization charges, and comorbidity prevalence.

2.6. Propensity Score Matching

To minimize selection bias and balance baseline characteristics between the groups, 2:1 propensity score matching was performed. Matching was performed using a nearest-neighbor algorithm without replacement and a caliper width of 0.1 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score. Matching was based on key demographic and clinical covariates, including age, sex, race, zip-code median household income, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and transplanted organ type.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages and compared using Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. Continuous variables are reported as means with standard deviation (SD) and compared using the t test. Standardized mean differences (SMDs) were calculated to assess post-matching balance between groups, with an SMD < 0.1 indicating acceptable balance.

To identify independent predictors of composite graft-related complications, univariate logistic regression was first performed to assess the association between each covariate and the outcome. Variables with clinical relevance or those demonstrating associations on univariate analysis were then included in a multivariate logistic regression model. Covariates included in the multivariate model were bariatric surgery history, age, sex, race/ethnicity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, acute kidney injury, and sepsis. Results are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

All analyses were performed using Stata version 19.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed p value < 0.05.

2.8. Ethical Considerations

The NIS is a de-identified, publicly available dataset. Therefore, this study was exempt from institutional review board approval and the requirement for informed consent.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Propensity Score Matching

The initial study population comprised 196,871 patients with a history of solid organ transplantation, of whom 2670 (1.4%) had a documented history of bariatric surgery and 194,232 (98.6%) did not. Following 2:1 propensity score matching, the final analytic cohort comprised 7347 patients: 2530 patients with a history of bariatric surgery and 4817 matched controls without bariatric surgery (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline and clinical characteristics of the pre- and post-propensity score–matched study cohort.

3.2. Baseline Characteristics of the Matched Cohort

After propensity score matching, the bariatric surgery and control groups demonstrated well-balanced covariate distributions. The mean age at admission was similar between groups: 55.60 (SD 11.30) years in the bariatric surgery group versus 56.26 (SD 13.93) years in controls (p = 0.041; SMD = −0.05). Sex distribution was comparable, with females comprising 37.5% of the bariatric surgery group and 36.0% of controls (p = 0.20; SMD = −0.03). Racial composition was similar between groups, with White patients representing 63.2% and 67.9%, Black patients 21.9% and 18.4%, and Hispanic patients 11.3% and 10.7% in the bariatric surgery and control groups, respectively. Median household income quartile distribution was well balanced across groups (p = 0.504; SMD = 0.04).

Both groups had comparable comorbidity burden, measured by the CCI, with mean scores of 3.27 (SD 1.8) in the bariatric surgery group and 3.28 (SD 1.8) in controls (p = 0.94; SMD = 0). The distribution of transplanted organ type was similar after matching, with kidney transplants being most common in both groups (63.6% vs. 60.7%), followed by liver (26.0% vs. 26.0%), heart (9.3% vs. 8.0%), lung (3.1% vs. 5.7%), and pancreas (4.2% vs. 7.9%). Hospital region distribution showed most patients in both groups were from the South (37.4% vs. 38.2%) and Midwest (27.9% vs. 24.8%) regions (Table 1).

3.3. Comorbidity Comparison

After propensity score matching, several comorbidities differed significantly between groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of comorbidities within the propensity score–matched study cohort.

Patients with a history of bariatric surgery had significantly lower rates of coronary artery disease (20.8% vs. 25.3%, p < 0.001), congestive heart failure (15.8% vs. 19.2%, p < 0.001), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (6.4% vs. 8.2%, p = 0.01), hypertension (75.3% vs. 77.6%, p = 0.03), and sepsis (12.5% vs. 14.4%, p = 0.02) compared to controls.

Conversely, patients in the bariatric surgery group had significantly higher rates of depression (22.8% vs. 16.6%, p < 0.001) and alcohol use (4.7% vs. 2.1%, p < 0.001). No significant differences were observed in the prevalence of peripheral vascular disease, chronic kidney disease, liver disease, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, tobacco use, steroid use, any malignancy, acute kidney injury, urinary tract infection, or opportunistic infection between groups.

3.4. Hospitalization Outcomes

LOS was similar between the bariatric surgery and control groups, with mean values of 5.46 (SD 6.27) days and 5.30 (SD 5.16) days, respectively (p < 0.001; SMD = 0.11). Total hospitalization charges did not differ significantly between groups, with mean charges of USD 75,486 (SD 140,059) in the bariatric surgery group compared to USD 70,722 (SD 142,375) in controls (p = 0.17; SMD = 0.03).

3.5. Graft-Related Complications

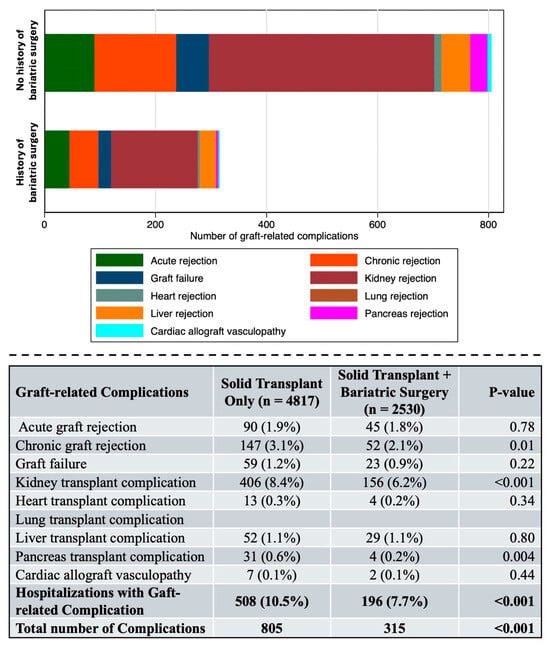

Patients with a history of bariatric surgery experienced significantly fewer composite graft-related complications compared to matched controls (7.7% vs. 10.5%, p < 0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Graft-related complications within the propensity score–matched study cohort. Complications in solid organ transplant recipients by bariatric surgery history. Stacked bar chart (upper panel) and summary (lower panel) displaying graft-related complications in the propensity score–matched cohort. Patients with a history of bariatric surgery (n = 2530) had significantly fewer composite graft-related complications compared to controls (n = 4817) (7.7% vs. 10.5%, p < 0.001). Bold letters indicate the summatory of all the complications. Bariatric surgery was associated with lower rates of chronic graft rejection (2.1% vs. 3.1%, p = 0.01), kidney transplant complications (6.2% vs. 8.4%, p < 0.001), and pancreas transplant complications (0.2% vs. 0.6%, p = 0.004). No significant differences were observed for acute graft rejection, graft failure, heart, lung, or liver transplant complications.

The total number of graft-related complications was also significantly lower in the bariatric surgery group (315 vs. 805 complications, p < 0.001).

Analysis of individual graft-related complications revealed that bariatric surgery was associated with significantly lower rates of chronic graft rejection (2.1% vs. 3.1%, p = 0.01) and kidney transplant complications (6.2% vs. 8.4%, p < 0.001). Pancreas transplant complications were also significantly lower in the bariatric surgery group (0.2% vs. 0.6%, p = 0.004). Rates of acute graft rejection (1.8% vs. 1.9%, p = 0.78), graft failure (0.9% vs. 1.2%, p = 0.22), heart transplant complications (0.2% vs. 0.3%, p = 0.34), liver transplant complications (1.1% vs. 1.1%, p = 0.80), and cardiac allograft vasculopathy (0.1% vs. 0.1%, p = 0.44) were comparable between groups.

3.6. Predictors of Graft-Related Complications

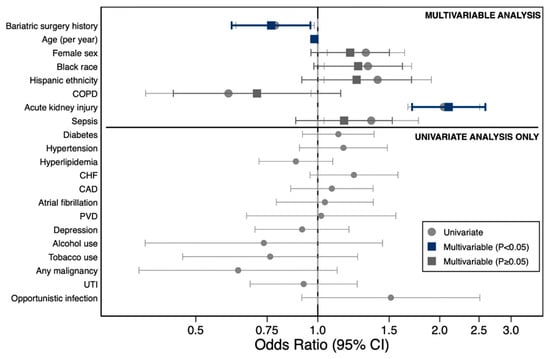

On univariate logistic regression analysis, several factors were significantly associated with graft-related complications (Table 3, Figure 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with graft complications.

Figure 3.

Factors Associated with graft-related complications following liver transplantation. Forest plot displaying odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals for factors associated with graft-related complications. Upper panel: multivariate model (circles, univariate; squares, multivariate adjusted; dark blue, p < 0.05; gray, p ≥ 0.05). Lower panel: univariate analysis only. Acute kidney injury (OR, 2.05) and Black race (OR, 1.35) were independently associated with increased risk, whereas bariatric surgery history (OR, 0.72) and COPD (OR, 0.78) were protective. Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Age was inversely associated with complications (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.97–0.99, p < 0.001), while female sex (OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.05–1.64, p = 0.015), Black race (OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.04–1.70, p = 0.024), Hispanic ethnicity (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.04–1.91, p = 0.029), acute kidney injury (OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.67–2.51, p < 0.001), and sepsis (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.04–1.77, p = 0.027) were positively associated with increased risk. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was associated with reduced risk on univariate analysis (OR 0.60, 95% CI 0.38–0.96, p = 0.034).

On multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, COPD, acute kidney injury, and sepsis, bariatric surgery history was independently associated with a 23% reduction in the odds of graft-related complications (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.61–0.96, p = 0.020). Age remained inversely associated with complications (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.97–0.99, p < 0.001), and acute kidney injury remained the strongest predictor of graft-related complications (OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.71–2.59, p < 0.001). Female sex, Black race, Hispanic ethnicity, COPD, and sepsis were no longer statistically significant in the adjusted model (Table 3, Figure 2).

4. Discussion

In this large, propensity-matched cross-sectional study, our findings indicate that patients with a history of bariatric surgery demonstrated significantly lower rates of metabolic-associated comorbidities, including coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, and hypertension. Notably, bariatric surgery was independently associated with 23% reduced odds of organ graft complications after adjusting for multiple cardiometabolic risk factors. Despite these findings, bariatric surgery continues to be an underutilized resource in patients in need of life-saving organ transplantation.

Bariatric surgery has been identified as the most cost-effective strategy for kidney transplant candidates with obesity at a willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of USD 50,000 per quality-adjusted life year [11]. This cost reduction can be attributed to a lower incidence of post-transplant complications, resulting in reduced use of intensive care services and medications. In contrast, another well-designed study, although with limited sample size, found no significant difference in hospitalization costs among a cohort of 39 liver transplant recipients who had previously undergone bariatric surgery compared to controls. Our study similarly found comparable expenses between patients undergoing and not undergoing bariatric surgery. The variability of the current data on this topic might be explained due to the variable sample size of the studies. However, the population-level sample size in this study strengthens the validity of the findings [12].

Allograft rejection is mediated by both innate and adaptive immune activation, a process that is exacerbated in the context of obesity [13]. Bariatric surgery may therefore attenuate this heightened immune response and reduce the risk of allograft rejection. In the present study, we observed that bariatric surgery was associated with a significant reduction in overall graft complications among solid organ transplant recipients, including chronic graft rejection and organ-specific complications such as in kidney and pancreas grafts. These findings are consistent with those of prior reports that bariatric surgery performed after KT was associated with a 15% reduced risk of all-cause graft failure, predominantly driven by decreases in chronic rejection [14]. In contrast, studies have found no significant differences in graft loss between KT recipients with obesity who underwent laparoscopic SG and BMI-matched controls, underscoring a possible procedure-specific association, though this was limited by small samples [15,16].

Evidence indicates heterogeneity in outcomes by bariatric procedure type. A US study reported that RYGB was associated with higher odds of overall morbidity, surgery-related complications, and hospital readmissions compared to SG among transplant recipients [17]. These differences likely reflect procedure-specific effects. RYGB involves intestinal bypass with significant implications for drug and nutrient absorption, whereas SG preserves intestinal continuity [18,19]. Consequently, emerging evidence suggests that SG has become the preferred bariatric approach in transplant populations, owing to more reliable immunosuppressant absorption and a lower risk of micronutrient deficiencies [18,19].

Nonetheless, like all bariatric procedures, SG carries a risk of micronutrient deficiencies, which typically emerge within 10 years postoperatively [20]. These deficiencies are particularly consequential in transplant recipients given the increased metabolic demands of graft function [21,22]. Notably, vitamin D deficiency has been associated with high odds of acute rejection in KT recipients (OR 1.82; 95% CI 1.29–2.56) [23]. However, evidence indicates that structured supplementation and routine monitoring of hematologic indices, micronutrient levels, and bone density can effectively mitigate these deficiencies [24,25].

Concerns have been raised regarding the potential impact of bariatric surgery on immunosuppressant absorption and subsequent graft function [26,27,28]. A study evaluating the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus, sirolimus, and mycophenolic acid in a cohort of KT recipients and candidates who had undergone RYGB [29] demonstrated reduced area under the concentration–time curve (AUC) for all three drugs, suggesting that higher doses may be required to achieve adequate immunosuppression in this population. In contrast, a US prospective study reported stable immunosuppressive drug levels in transplant recipients who underwent laparoscopic SG or RYGB, with no need for significant dose adjustments and no incidents of graft loss or major complications [19]. Similarly, more evidence has shown no significant changes in tacrolimus blood levels or dosing requirements in transplant recipients following laparoscopic SG or RYGB, indicating that both procedures can maintain effective immunosuppression post-transplant [30]. Our cross-sectional study favors that immunosuppression for transplant recipients is unaffected by bariatric surgery, though further studies supporting its efficacy are still needed.

The timing of bariatric surgery relative to transplantation is a clinically important consideration, as it may influence patient and graft outcomes. Although the benefits of bariatric surgery in solid organ transplantation are well established, the question of the most advantageous timing remains unresolved. A systematic review encompassing 19 studies evaluating patients who underwent bariatric surgery before or after liver transplant reported no 30-day mortality in either group, reinforcing the overall safety and potential benefit of the procedure regardless of timing [31]. Similarly, reductions in all-cause allograft failure and mortality have been seen in KT recipients who underwent bariatric surgery regardless of timing (before or after surgery) [14]. Although we recognize this is a critical question to answer, the cross-sectional nature of the NIS database precluded assessment of the optimal longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery relative to transplantation, and larger, well-designed prospective trials are needed to more definitively address this question.

The most actionable interpretation of our study is that a history of bariatric surgery is independently associated with reduced odds of graft-related complications after adjustment for multiple baseline risk factors. These findings align with the growing body of evidence supporting the safety and potential benefits of bariatric surgery in the transplant population [14]. Regarding comorbidities, we observed significantly lower rates of coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, and hypertension among transplant recipients with a history of bariatric surgery. Studies have shown similar results in a cohort of seven heart transplant candidates, demonstrating higher benefits in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) among those who underwent SG [32]. These findings further underscore the cardiovascular benefits of bariatric surgery in the transplant population, which may contribute to the observed reduction in graft-related complications through attenuation of the chronic inflammatory state and improved metabolic profiles associated with sustained weight loss.

This study has several limitations. First, the NIS only captures inpatient data; therefore, long-term post-discharge outcomes, graft survival beyond hospitalization, readmission rates, and mortality were not available. The database provides an unknown time elapsed between transplant and bariatric surgery, but prior studies have demonstrated comparable safety and efficacy regardless of whether bariatric surgery occurs before or after transplantation. Second, although the database captures multiple bariatric procedures (e.g., RYGB, SG, gastric banding), insufficient procedural granularity precluded stratification of outcomes by specific surgery type. Given emerging evidence that SG and RYGB differ in immunologic impact, nutritional effects, and drug absorption, future procedure-specific analyses are warranted. Third, the NIS does not include information on immunosuppressive regimens, drug levels, adherence, or adjustments following bariatric surgery, limiting interpretation of how these factors may influence graft outcomes. Specifically, we could not assess corticosteroid use, calcineurin inhibitor regimens, or other maintenance immunosuppression protocols that may impact outcomes. Fourth, the NIS database does not include ASA physical status classification scores or other procedure-specific risk stratification tools that allow a more detailed perioperative risk assessment. However, we used the Charlson Comorbidity Index as a validated proxy for overall comorbidity burden, which was well balanced between groups after propensity score matching.

5. Conclusions

In this nationally representative cohort of propensity score–matched solid organ transplant recipients, bariatric surgery was associated with significantly lower rates of composite graft-related complications, driven primarily by reductions in chronic graft rejection, kidney transplant complications, and pancreas transplant complications. Additionally, patients with prior bariatric surgery demonstrated lower prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities, including coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, and hypertension. These findings reinforce the role of bariatric surgery as a safe and potentially immunomodulatory strategy to improve outcomes in a population historically excluded from transplantation due to perceived surgical risk.

Future work should focus on prospective studies that can corroborate our findings and evaluate long-term survival, graft function, and longitudinal quality of life outcomes, stratifying by specific bariatric procedure type. The integration of bariatric surgery and obesity specialists into the multidisciplinary organ transplantation team can help mitigate provider bias and optimize perioperative care of patient candidates for both bariatric surgery and organ transplantation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S. and R.S.-L.; project administration, L.S.; methodology, L.S., S.F., and R.S.-L.; writing—original draft, L.S. and A.C.; visualization, L.S., K.B., and R.P.; writing—review and editing, L.S., K.B., M.O.A., A.K., A.C., R.P., and S.F.; supervision, R.S.-L.; validation, L.S. and R.S.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and the principles of good clinical practice. Ethics approval was not required, as this study used de-identified data from a publicly accessible database.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable because the database used is publicly available, fully de-identified database that contains no patient-level identifiers.

Data Availability Statement

This study utilized the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), a publicly available, de-identified database maintained by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Data can be accessed through the HCUP after completion of the required data use agreement and purchase of the dataset (https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov (accessed on 5 July 2025)).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript.

| AHRQ | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

| AUC | area under the concentration–time curve |

| BMI | body mass index |

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| CI | confidence interval |

| CM | clinical modification |

| COPD | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| HCUP | Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project |

| ICD-10-CM | International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification |

| ICD-10-PCS | International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Procedure Coding System |

| KT | kidney transplantation |

| LOS | length of stay |

| LVEF | left ventricular ejection fraction |

| NIS | Nationwide Inpatient Sample |

| OR | odds ratio |

| PCS | Procedure Coding System |

| RYGB | Roux-en-Y gastric bypass |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SG | sleeve gastrectomy |

| SMD | standardized mean difference |

| US | United States |

| WTP | willingness to pay |

References

- GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanem, O.M.; Pita, A.; Nazzal, M.; Johnson, S.; Diwan, T.; Obeid, N.R.; Croome, K.P.; Lim, R.; Quintini, C.; Whitson, B.A.; et al. Obesity, organ failure, and transplantation: A review of the role of metabolic and bariatric surgery in transplant candidates and recipients. Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 4138–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B.; Sultana, R.; Greene, M.W. Adipose tissue and insulin resistance in obese. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 111315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierpont, Y.N.; Dinh, T.P.; Salas, R.E.; Johnson, E.L.; Wright, T.G.; Robson, M.C.; Payne, W.G. Obesity and surgical wound healing: A current review. ISRN Obes. 2014, 2014, 638936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuette, H.B.; Durkin, W.M.; Passias, B.J.; DeGenova, D.; Bertolini, C.; Myers, P.; Taylor, B.C. The Effect of Obesity on Operative Time and Postoperative Complications for Peritrochanteric Femur Fractures. Cureus 2020, 12, e11720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.I. Obesity—A reluctance to treat? Obes. Facts 2010, 3, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelan, S.M.; Burgess, D.J.; Yeazel, M.W.; Hellerstedt, W.L.; Griffin, J.M.; van Ryn, M. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.S.; Lan, J.; Dong, J.; Rose, C.; Hendren, E.; Johnston, O.; Gill, J. The survival benefit of kidney transplantation in obese patients. Am. J. Transplant. 2013, 13, 2083–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, W.R., Jr.; Oliveira, L.V.F.; Perez, E.A.; Ilias, E.J.; Lottenberg, C.P.; Silva, A.S.; Urbano, J.J.; Oliveira, M.C., Jr.; Vieira, R.P.; Ribeiro-Alves, M.; et al. Systemic inflammation in severe obese patients undergoing surgery for obesity and weight-related diseases. Obes. Surg. 2018, 28, 1931–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, E.L.; Ellias, S.D.; Blezek, D.J.; Klug, J.; Hartman, R.P.; Ziller, N.F.; Bamlet, H.; Mao, S.A.; Perry, D.K.; Nimma, I.R.; et al. Simultaneous liver transplant and sleeve gastrectomy provides durable weight loss, improves metabolic syndrome and reduces allograft steatosis. J. Hepatol. 2025, 83, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puttarajappa, C.M.; Smith, K.J.; Ahmed, B.H.; Bernardi, K.; Lavenburg, L.-M.; Hoffman, W.; Molinari, M. Economic evaluation of weight loss and transplantation strategies for kidney transplant candidates with obesity. Am. J. Transplant. 2024, 24, 2212–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannelli, A.; Bulsei, J.; Debs, T.; Tran, A.; Lazzati, A.; Gugenheim, J.; Anty, R.; Petrucciani, N.; Fontas, E. Clinical and economic impact of previous bariatric surgery on liver transplantation: A nationwide, population-based retrospective study. Obes. Surg. 2022, 32, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucchiari, D.; Podestà, M.A.; Ponticelli, C. Pathophysiology of rejection in kidney transplantation. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2024, 20, 1471–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.B.; Lim, M.A.; Tewksbury, C.M.; Torres-Landa, S.; Trofe-Clark, J.; Abt, P.L.; Williams, N.N.; Dumon, K.R.; Goral, S. Bariatric surgery before and after kidney transplantation: Long-term weight loss and allograft outcomes. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2019, 15, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Jung, A.D.; Dhar, V.K.; Tadros, J.S.; Schauer, D.P.; Smith, E.P.; Hanseman, D.J.; Cuffy, M.C.; Alloway, R.R.; Shields, A.R.; et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy improves renal transplant candidacy and posttransplant outcomes in morbidly obese patients. Am. J. Transplant. 2018, 18, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quante, M.; Iske, J.; Uehara, H.; Minami, K.; Nian, Y.; Maenosono, R.; Matsunaga, T.; Liu, Y.; Azuma, H.; Perkins, D.; et al. Taurodeoxycholic acid and valine reverse obesity-associated augmented alloimmune responses and prolong allograft survival. Am. J. Transplant. 2022, 22, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagenson, A.M.; Mazzei, M.; Swaszek, L.; Edwards, M.A. Is bariatric procedure type associated with morbidity in transplant patients? J. Surg. Res. 2022, 273, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zevallos, A.; Cornejo, J.; Sarmiento, J.; Shojaeian, F.; Mokhtari-Esbuie, F.; Adrales, G.; Li, C.; Sebastian, R. Outcomes of Sleeve Gastrectomy in Patients with Organ Transplant-Related Immunosuppression. J. Surg. Res. 2024, 300, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemini, R.; Nesher, E.; Winkler, J.; Carmeli, I.; Azran, C.; Ben David, M.; Mor, E.; Keidar, A. Bariatric surgery in solid organ transplant patients: Long-term follow-up results of outcome, safety, and effect on immunosuppression. Am. J. Transplant. 2018, 18, 2772–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humięcka, M.; Sawicka, A.; Kędzierska, K.; Binda, A.; Jaworski, P.; Tarnowski, W.; Jankowski, P. Prevalence of nutrient deficiencies following bariatric surgery-long-term, prospective observation. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obinwanne, K.M.; Fredrickson, K.A.; Mathiason, M.A.; Kallies, K.J.; Farnen, J.P.; Kothari, S.N. Incidence, treatment, and outcomes of iron deficiency after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: A 10-year analysis. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014, 218, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarno, G.; Nappi, R.; Altieri, B.; Tirabassi, G.; Muscogiuri, E.; Salvio, G.; Paschou, S.A.; Ferrara, A.; Russo, E.; Vicedomini, D.; et al. Current evidence on vitamin D deficiency and kidney transplant: What’s new? Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2017, 18, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzakhani, M.; Mohammadkhani, S.; Hekmatirad, S.; Aghapour, S.; Gorjizadeh, N.; Shahbazi, M.; Mohammadnia-Afrouzi, M. The association between vitamin D and acute rejection in human kidney transplantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. Transpl. Immunol. 2021, 67, 101410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechanick, J.I.; Apovian, C.; Brethauer, S.; Garvey, W.T.; Joffe, A.M.; Kim, J.; Kushner, R.F.; Lindquist, R.; Pessah-Pollack, R.; Seger, J.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutrition, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of patients undergoing bariatric procedures—2019 update: Cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology, The Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery, Obesity Medicine Association, and American Society of Anesthesiologists. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2020, 16, 175–247. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott, J.; Frank, L.; Rabena, R.; Craggs-Dino, L.; Isom, K.A.; Greiman, L. American Society for Metabolic and bariatric surgery integrated health nutritional guidelines for the surgical weight loss patient 2016 update: Micronutrients. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2017, 13, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sierra, L.; Aitharaju, V.; Prado, R.; Cymbal, M.; Chaterjee, A.; Khurana, A.; Patel, R.; Firkins, S.; Simons-Linares, R. In-Hospital Outcomes of Bariatric Surgery in People Living with HIV: A Nationwide Analysis. Obes. Surg. 2025, 35, 3111–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenackers, N.; Vanuytsel, T.; Augustijns, P.; Tack, J.; Mertens, A.; Lannoo, M.; Van der Schueren, B.; Matthys, C. Adaptations in gastrointestinal physiology after sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angeles, P.C.; Robertsen, I.; Seeberg, L.T.; Krogstad, V.; Skattebu, J.; Sandbu, R.; Åsberg, A.; Hjelmesæth, J. The influence of bariatric surgery on oral drug bioavailability in patients with obesity: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 1299–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.C.; Alloway, R.R.; Alexander, J.W.; Cardi, M.; Trofe, J.; Vinks, A.A. Pharmacokinetics of mycophenolic acid, tacrolimus and sirolimus after gastric bypass surgery in end-stage renal disease and transplant patients: A pilot study. Clin. Transplant. 2008, 22, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A.N.; Wolfe, B. Is Bariatric Surgery an Effective Treatment for Type II Diabetic Kidney Disease? Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 11, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Tian, C.; Lovrics, O.; Soon, M.S.; Doumouras, A.G.; Anvari, M.; Hong, D. Bariatric surgery before, during, and after liver transplantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2020, 16, 1336–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esparham, A.; Mehri, A.; Hadian, H.; Taheri, M.; Moghadam, H.A.; Kalantari, A.; Fogli, M.J.; Khorgami, Z. The Effect of Bariatric Surgery on Patients with Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes. Surg. 2023, 33, 4125–4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.