Anatomical and Systemic Predictors of Early Response to Subthreshold Micropulse Laser in Diabetic Macular Edema: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Image Acquisition and AI-Based Segmentation

- Fluid Volumetrics: Total volume (mm3) of intraretinal fluid (IRF) and subretinal fluid (SRF) within the 6 × 6 macular grid.

- Hyperreflective Foci (HRF): Automatic count of hyperreflective foci (HRF) within the central 3 mm of the linear HR scan.

- Outer Retinal Integrity: Percentage of disruption of the external limiting membrane (ELM) and ellipsoid zone (EZ) within the central 1 mm of the fovea, at 3 mm, and 6 mm, respectively.

- Central Subfield Thickness (CST): defined as the mean retinal thickness within the central 1 mm ETDRS subfield, was extracted from the automated macular map of the OCT device (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany).

2.3. Systemic and Clinical Data Collection

- Demographics: Age, gender.

- Metabolic Control: HbA1c levels (most recent value within 3 months of treatment), type of diabetes, and disease duration.

- Therapeutic History: Previous panretinal photocoagulation (PRP), number of prior intravitreal anti-VEGF injections, and time since the last injection.

2.4. SMPL Treatment Protocol

2.5. Outcomes

- Change in best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA);

- Change in absolute and relative subretinal fluid (SRF) volume;

- Change in hyperreflective foci (HRF) count;

- Change in central subfield thickness (CST), automatically derived from the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study ETDRS grid of the OCT instrument;

- Changes in outer retinal integrity (ELM and EZ disruption) evaluated at 1, 3, and 6 mm.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Demographic and Systemic Characteristics

3.2. Ocular History

3.3. Safety

3.4. Baseline Anatomical Characteristics

3.5. Visual Acuity Outcomes

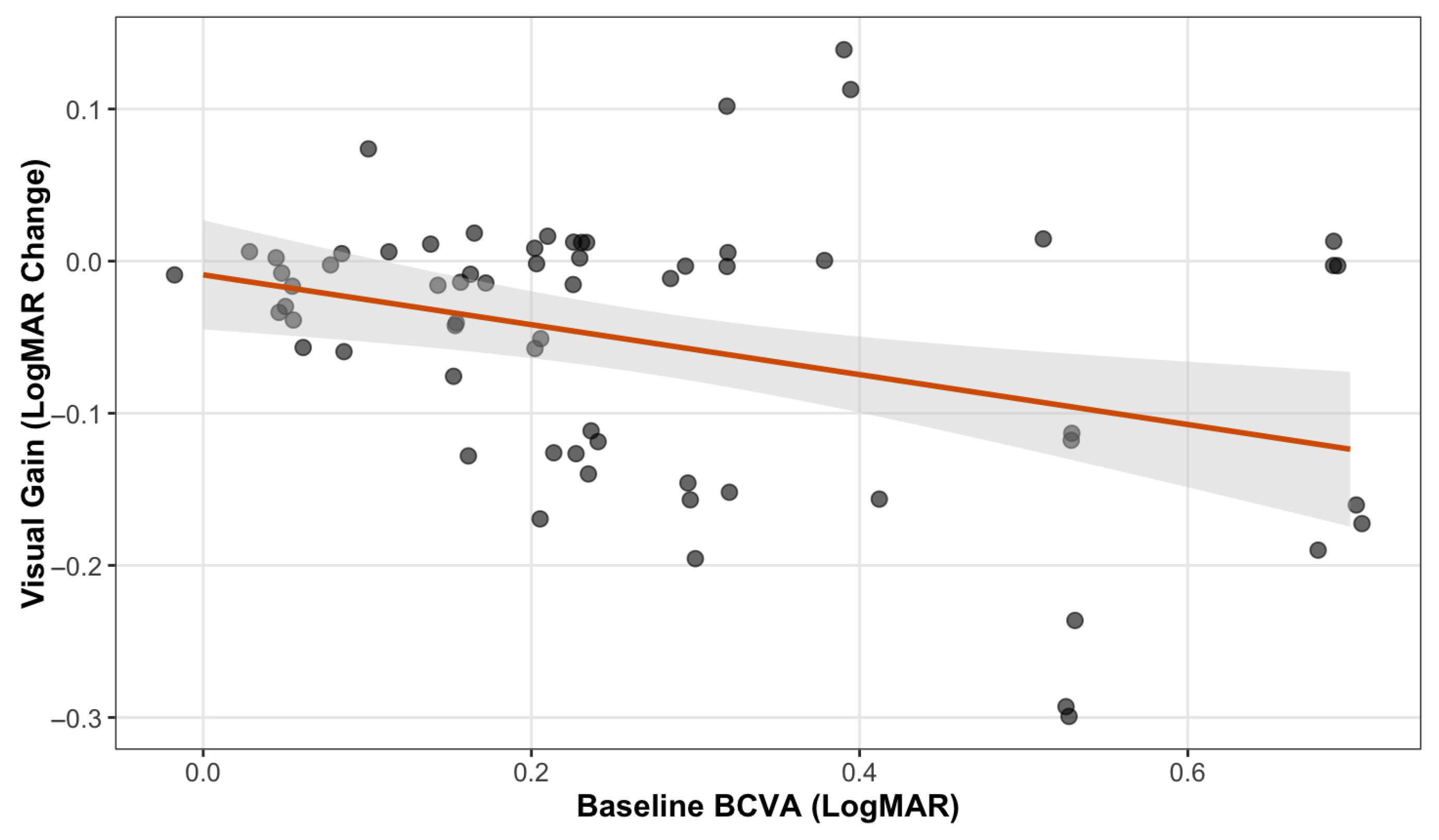

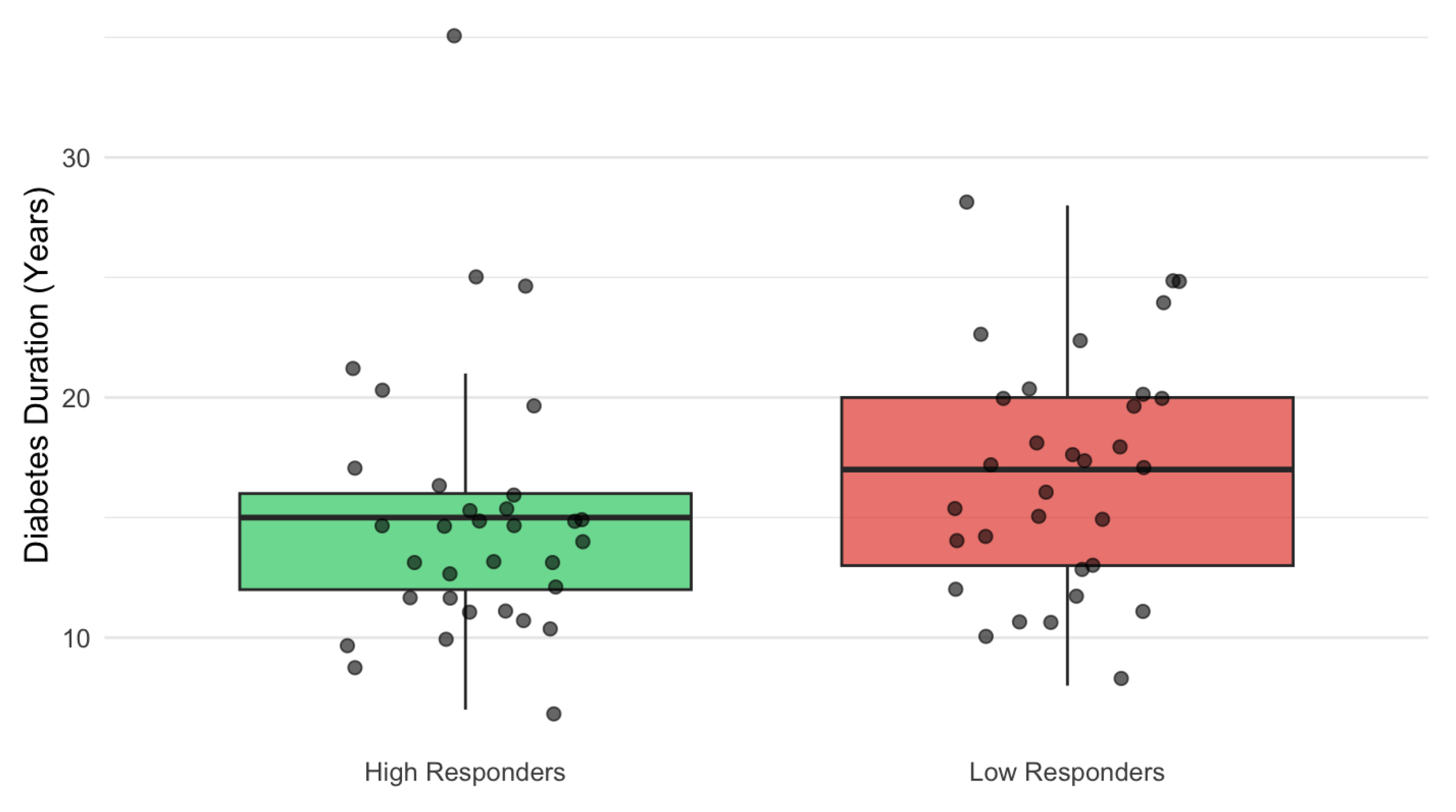

3.6. Predictors of Visual Response

3.7. Anatomical Outcomes

3.8. Predictors of Anatomical Outcomes

3.9. Time–Response Relationship

3.10. Impact of the Number of IVTs and HbA1c

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| BCVA | Best-corrected visual acuity |

| cCSC | Chronic central serous chorioretinopathy |

| CE | Conformité Européenne (European conformity marking) |

| CST | Central subfield thickness |

| DL | Deep learning |

| DME | Diabetic macular edema |

| ETDRS | Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study |

| EZ | Ellipsoid zone |

| FAZ | Foveal avascular zone |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| HRF | Hyperreflective foci |

| IRF | Intraretinal fluid |

| IVT | Intravitreal therapy |

| OCT | Optical coherence tomography |

| PRP | Panretinal photocoagulation |

| RPE | Retinal pigment epithelium |

| SD-OCT | Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography |

| SMPL | Subthreshold micropulse laser |

| SRF | Subretinal fluid |

References

- Daruich, A.; Matet, A.; Moulin, A.; Kowalczuk, L.; Nicolas, M.; Sellam, A.; Rothschild, P.R.; Omri, S.; Gélizé, E.; Jonet, L.; et al. Mechanisms of macular edema: Beyond the surface. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2018, 63, 20–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonder, J.R.; Walker, V.M.; Barbeau, M.; Zaour, N.; Zachau, B.H.; Hartje, J.R.; Li, R. Costs and Quality of Life in Diabetic Macular Edema: Canadian Burden of Diabetic Macular Edema Observational Study (C-REALITY). J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 2014, 939315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Garcia-Arumi, J.; Bandello, F.; Berg, K.; Chakravarthy, U.; Gerendas, B.S.; Jonas, J.; Larsen, M.; Tadayoni, R.; Loewenstein, A. Guidelines for the Management of Diabetic Macular Edema by the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA). Ophthalmologica 2017, 237, 185–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Diabetic Retinopathy: Management and Monitoring; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng242 (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Parravano, M.; Cennamo, G.; Di Antonio, L.; Grassi, M.O.; Lupidi, M.; Rispoli, M.; Savastano, M.C.; Veritti, D.; Vujosevic, S. Multimodal imaging in diabetic retinopathy and macular edema: An update about biomarkers. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2024, 69, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoramnia, R.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Kertes, P.J.; Sararols Ramsay, L.; Vujosevic, S.; Anderesi, M.; Igwe, F.; Eter, N. Exploring the role of retinal fluid as a biomarker for the management of diabetic macular oedema. Eye 2024, 38, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couturier, A.; Wykoff, C.C.; Lupidi, M.; Udaondo, P.; Peto, T.; Pintard, P.J. Anatomic biomarkers as potential endpoints in diabetic macular edema: A systematic literature review with identification of macular volume as a key surrogate for visual acuity. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2025, 70, 1090–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midena, E.; Lupidi, M.; Toto, L.; Covello, G.; Veritti, D.; Pilotto, E.; Cicinelli, M.V.; Lattanzio, R.; Figus, M.; Midena, G.; et al. AI-Assisted OCT Clinical Phenotypes of Diabetic Macular Edema: A Large Cohort Clustering Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooner, K.L.; Guinan, G.; Koller, S.; Hong, T.; Chang, A.A. Burden Of Treatment Among Patients Undergoing Intravitreal Injections For Diabetic Macular Oedema In Australia. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2019, 12, 1913–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Park, S.J.; Yoon, H.; Choi, S.; Mun, Y.; Kim, S.; Yoo, S.; Woo, S.J.; Park, K.H.; Na, J.; et al. Patient-Centered Economic Burden of Diabetic Macular Edema: Retrospective Cohort Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2024, 10, e56741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabano, D.; Watane, A.; Gale, R.; Cox, O.; Hill, S.R.; Longworth, L.; Oluboyede, Y.; Ahmed, A.; Patel, N.A. The Economic Burden of Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor on Patients and Caregivers in the UK, Europe, and North America. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2025, 14, 1869–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edington, M.; Connolly, J.; Chong, N.V. Pharmacokinetics of intravitreal anti-VEGF drugs in vitrectomized versus non-vitrectomized eyes. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2017, 13, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israilevich, R.N.; Mansour, H.; Patel, S.N.; Garg, S.J.; Klufas, M.A.; Yonekawa, Y.; Regillo, C.D.; Hsu, J. Risk of Endophthalmitis Based on Cumulative Number of Anti-VEGF Intravitreal Injections. Ophthalmology 2024, 131, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, S.; Walder, A.; Virani, S.; Biggerstaff, K.; Orengo-Nania, S.; Chang, J.; Channa, R. Systemic Adverse Events Among Patients With Diabetes Treated With Intravitreal Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Injections. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023, 141, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midena, E.; Micera, A.; Frizziero, L.; Pilotto, E.; Esposito, G.; Bini, S. Sub-threshold micropulse laser treatment reduces inflammatory biomarkers in aqueous humour of diabetic patients with macular edema. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabal, B.; Wylęgała, E.; Teper, S. Impact of Subthreshold Micropulse Laser on the Vascular Network in Diabetic Macular Edema: An Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Study. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujosevic, S.; Lupidi, M.; Donati, S.; Astarita, C.; Gallinaro, V.; Pilotto, E. Role of inflammation in diabetic macular edema and neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 2024, 69, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazel, F.; Bagheri, M.; Golabchi, K.; Jahanbani Ardakani, H. Comparison of subthreshold diode laser micropulse therapy versus conventional photocoagulation laser therapy as primary treatment of diabetic macular edema. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 2016, 28, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikushima, W.; Furuhata, Y.; Shijo, T.; Matsumoto, M.; Sakurada, Y.; Viel Tsuru, D.; Kashiwagi, K. Comparison of one-year real-world outcomes between red (670 nm) subthreshold micropulse laser treatment and intravitreal aflibercept injection for treatment-naïve diabetic macular edema. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2025, 51, 104430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; He, W.; Qi, S. Evaluating the efficacy of subthreshold micropulse laser combined with anti-VEGF drugs in the treatment of diabetic macular edema: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1553311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujosevic, S.; Toma, C.; Villani, E.; Brambilla, M.; Torti, E.; Leporati, F.; Muraca, A.; Nucci, P.; De Cilla, S. Subthreshold Micropulse Laser in Diabetic Macular Edema: 1-Year Improvement in OCT/OCT-Angiography Biomarkers. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, K.; Shiraya, T.; Araki, F.; Hashimoto, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Yamanari, M.; Ueta, T.; Minami, T.; Aoki, N.; Sugiyama, S.; et al. Changes in entropy on polarized-sensitive optical coherence tomography images after therapeutic subthreshold micropulse laser for diabetic macular edema: A pilot study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirik, F.; Ersoz, M.G.; Atalay, F.; Akbulut, E.; Kucuk, M.; Koytak, A.; Ozdemir, H. Outer Retinal Layer Deterioration Patterns in Eyes with Diabetic Serous Macular Detachment. Retina, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, L.J.; Auffarth, G.U.; Bagautdinov, D.; Khoramnia, R. Ellipsoid Zone Integrity and Visual Acuity Changes during Diabetic Macular Edema Therapy: A Longitudinal Study. J. Diabetes Res. 2021, 2021, 8117650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muftuoglu, I.K.; Mendoza, N.; Gaber, R.; Alam, M.; You, Q.; Freeman, W.R. Integrity of Outer Retinal Layers after Resolution of Central Involved Diabetic Macular Edema. Retina 2017, 37, 2015–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Luo, D.; Qiu, Q.; Xu, G.T.; Zhang, J. Hyperreflective Foci in Diabetic Macular Edema with Subretinal Fluid: Association with Visual Outcomes after Anti-VEGF Treatment. Ophthalmic Res. 2023, 66, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passos, R.M.; Malerbi, F.K.; Rocha, M.; Maia, M.; Farah, M.E. Real-life outcomes of subthreshold laser therapy for diabetic macular edema. Int. J. Retin. Vitr. 2021, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, A.; Sampat, K.M.; Malik, K.J.; Steiner, J.N.; Glaser, B.M. Efficacy of subthreshold micropulse laser in the treatment of diabetic macular edema is influenced by pre-treatment central foveal thickness. Eye 2014, 28, 1418–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citirik, M. The impact of central foveal thickness on the efficacy of subthreshold micropulse yellow laser photocoagulation in diabetic macular edema. Lasers Med. Sci. 2019, 34, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık, M.U.; Değirmenci, M.F.K.; Sağlık, A. Factors affecting the response to subthreshold micropulse laser therapy used in center-involved diabetic macular edema. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 1865–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parravano, M.; Costanzo, E.; Querques, G. Profile of non-responder and late responder patients treated for diabetic macular edema: Systemic and ocular factors. Acta Diabetol. 2020, 57, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.; Carass, A.; Hauser, M.; Sotirchos, E.S.; Calabresi, P.A.; Ying, H.S.; Prince, J.L. Retinal layer segmentation of macular OCT images using boundary classification. Biomed. Opt. Express 2013, 4, 1133–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.K.; Vogl, W.D.; Gerendas, B.S.; Glassman, A.R.; Bogunovic, H.; Jampol, L.M.; Schmidt-Erfurth, U.M. Quantification of Fluid Resolution and Visual Acuity Gain in Patients With Diabetic Macular Edema Using Deep Learning: A Post Hoc Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020, 138, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicinelli, M.V.; Leonardo, B.; Maiucci, G.; Martino, G.; Ziafati, M.; Bousyf, S.; Frizziero, L.; Lattanzio, R.; Midena, E.; Bandello, F. What Lies beneath Diabetic Macular Edema: Latent Phenotypic Clustering and Differential Treatment Responses to Intravitreal Therapies. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2025, 6, 100975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midena, E.; Toto, L.; Frizziero, L.; Covello, G.; Torresin, T.; Midena, G.; Danieli, L.; Pilotto, E.; Figus, M.; Mariotti, C.; et al. Validation of an Automated Artificial Intelligence Algorithm for the Quantification of Major OCT Parameters in Diabetic Macular Edema. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhablani, J.; SOLS (Subthreshold Laser Ophthalmic Society) Writing Committee. Subthreshold Laser Therapy Guidelines for Retinal Diseases. Eye 2022, 36, 2234–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keunen, J.E.E.; Battaglia-Parodi, M.; Vujosevic, S.; Luttrull, J.K. International Retinal Laser Society Guidelines for Subthreshold Laser Treatment. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frizziero, L.; Calciati, A.; Torresin, T.; Midena, G.; Parrozzani, R.; Pilotto, E.; Midena, E. Diabetic Macular Edema Treated with 577-nm Subthreshold Micropulse Laser: A Real-Life, Long-Term Study. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikushima, W.; Shijo, T.; Furuhata, Y.; Sakurada, Y.; Kashiwagi, K. Comparison of the 1-Year Visual and Anatomical Outcomes between Subthreshold Red (670 nm) and Yellow (577 nm) Micro-Pulse Laser Treatment for Diabetic Macular Edema. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodea, F.; Bungau, S.G.; Bogdan, M.A.; Vesa, C.M.; Radu, A.; Tarce, A.G.; Purza, A.L.; Tit, D.M.; Bustea, C.; Radu, A.F. Micropulse Laser Therapy as an Integral Part of Eye Disease Management. Medicina 2023, 59, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.; Wu, Y.; Shao, C.; Qiu, Q. The Role of Müller Cells in Diabetic Macular Edema. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Long, H.; Hu, Q. Efficacy of Subthreshold Micropulse Laser for Chronic Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: A Meta-Analysis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 39, 102931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Park, Y.G.; Jeon, S.H.; Choi, S.Y.; Roh, Y.J. The Efficacy of Selective Retina Therapy for Diabetic Macular Edema Based on Pretreatment Central Foveal Thickness. Lasers Med. Sci. 2020, 35, 1781–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otani, T.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Kishi, S. Correlation between Visual Acuity and Foveal Microstructural Changes in Diabetic Macular Edema. Retina 2010, 30, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Miyamoto, N.; Ishida, K.; Kurimoto, Y. Association between External Limiting Membrane Status and Visual Acuity in Diabetic Macular Oedema. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 97, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achiron, A.; Kydyrbaeva, A.; Man, V.; Lagstein, O.; Burgansky, Z.; Blumenfeld, O.; Bar, A.; Bartov, E. Photoreceptor Integrity Predicts Response to Anti-VEGF Treatment. Ophthalmic Res. 2017, 57, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujosevic, S.; Frizziero, L.; Martini, F.; Bini, S.; Convento, E.; Cavarzeran, F.; Midena, E. Single Retinal Layer Changes After Subthreshold Micropulse Yellow Laser in Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retin. 2018, 49, e218–e225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissing, T.; Stewart, M.W.; Qian, C.X.; Rittenhouse, K.D. Durability of VEGF Suppression with Intravitreal Aflibercept and Brolucizumab: Using Pharmacokinetic Modeling to Understand Clinical Outcomes. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, J.; Kang, J.; Kang, W. Comparative Ocular Pharmacokinetics of Dexamethasone Implants in Rabbits. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 40, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.P.; Habbu, K.; Ehlers, J.P.; Lansang, M.C.; Hill, L.; Stoilov, I. The Impact of Systemic Factors on Clinical Response to Ranibizumab for Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 1581–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.M.; Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Do, D.V.; Holz, F.G.; Boyer, D.S.; Midena, E.; Heier, J.S.; Terasaki, H.; Kaiser, P.K.; Marcus, D.M.; et al. Intravitreal Aflibercept for Diabetic Macular Edema: 100-Week Results from the VISTA and VIVID Studies. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 2044–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressler, S.B.; Odia, I.; Maguire, M.G.; Dhoot, D.S.; Glassman, A.R.; Jampol, L.M.; Marcus, D.M.; Solomon, S.D.; Sun, J.K. Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Factors Associated With Visual Acuity and Central Subfield Thickness Changes When Treating Diabetic Macular Edema With Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Therapy: An Exploratory Analysis of the Protocol T Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019, 137, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Outcome Measure | Baseline (T0) Median [IQR] | Follow-Up (T1) Median [IQR] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCVA (logMAR) | 0.22 [0.15–0.30] | 0.15 [0.10–0.30] | <0.001 |

| Central Subfield Thickness (CST, µm) | 342.00 [307–392] | 340.00 [298–418] | 0.78 |

| Intraretinal Fluid (IRF, mm3) | 0.326 [0.135–1.091] | 0.283 [0.089–0.806] | 0.034 |

| Subretinal fluid (SRF, mm3) | 0.026 mm3; [0.020–0.046] | 0.00 mm3 [0–0] | 0.031 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gagliardi, O.M.; Gregori, G.; Muzi, A.; Mangoni, L.; Mogetta, V.; Chhablani, J.; Pompucci, G.; Rizzo, C.; Iannetta, D.; Mariotti, C.; et al. Anatomical and Systemic Predictors of Early Response to Subthreshold Micropulse Laser in Diabetic Macular Edema: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 955. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15030955

Gagliardi OM, Gregori G, Muzi A, Mangoni L, Mogetta V, Chhablani J, Pompucci G, Rizzo C, Iannetta D, Mariotti C, et al. Anatomical and Systemic Predictors of Early Response to Subthreshold Micropulse Laser in Diabetic Macular Edema: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):955. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15030955

Chicago/Turabian StyleGagliardi, Oscar Matteo, Giulia Gregori, Alessio Muzi, Lorenzo Mangoni, Veronica Mogetta, Jay Chhablani, Gregorio Pompucci, Clara Rizzo, Danilo Iannetta, Cesare Mariotti, and et al. 2026. "Anatomical and Systemic Predictors of Early Response to Subthreshold Micropulse Laser in Diabetic Macular Edema: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 955. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15030955

APA StyleGagliardi, O. M., Gregori, G., Muzi, A., Mangoni, L., Mogetta, V., Chhablani, J., Pompucci, G., Rizzo, C., Iannetta, D., Mariotti, C., & Lupidi, M. (2026). Anatomical and Systemic Predictors of Early Response to Subthreshold Micropulse Laser in Diabetic Macular Edema: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 955. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15030955