Abstract

Background/Objectives: Thrombotic events represent the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with Philadelphia chromosome-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (Ph− MPNs), particularly in those aged > 60 years. The immature platelet fraction (IPF) reflects the proportion of newly released, reticulated, highly reactive platelets and has emerged as a marker of thrombopoietic activity in various prothrombotic conditions. Methods: We prospectively measured IPF in 45 patients with newly diagnosed Ph− MPNs (24 with essential thrombocythemia, 13 with polycythemia vera, 5 with MPN-unclassified, and 3 with primary myelofibrosis) and 27 controls without MPN. Results: IPF was significantly higher in patients with Ph− MPN than in controls (median 27 vs. 10.9, p < 0.0001). Within the MPN cohort, IPF values differed significantly across subtypes (p = 0.027), being highest in essential thrombocythemia and primary myelofibrosis, intermediate in unclassified MPN, and lowest in polycythemia vera. Patients older than 60 years exhibited higher IPF independently of platelet count (p = 0.021). No significant difference was observed between JAK2V617F-positive and -negative cases. Conclusions: These results indicate that IPF captures accelerated and dysregulated thrombopoiesis characteristics of Ph− MPNs and may provide additional insight into subtype-specific biology and age-related prothrombotic risk beyond conventional complete blood count parameters.

1. Introduction

The Philadelphia chromosome-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (Ph− MPNs) are clonal neoplastic disorders of the myeloid hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). These disorders are classified into polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), primary myelofibrosis (PMF), and rarer entities such as chronic neutrophilic leukemia, chronic eosinophilic leukemia, and unclassified MPN(MPN-U) [1]. The main mutations in the gene for Janus kinase 2 (JAK2V617F), the thrombopoietin receptor (MPL), and calreticulin (CALR) are present in over 90% of patients with MPN and promote the activation of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, resulting in cytokine-independent proliferation of one or more myeloid lineages [2].

Thrombotic events can occur at the time of diagnosis in up to 20% of patients with Ph− MPN and are the most common cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with MPN. Both arterial (myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke) and venous events (deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and splanchnic vein thrombosis) are markedly increased in patients with MPN compared with age-matched populations [3]. A retrospective analysis of patients with MPNs from the Swedish Cancer Registry reported that at 3 months after diagnosis, patients with PV had an approximately 3- and 13-fold higher risk of arterial thrombosis and venous thrombosis, respectively, compared with controls matched for age and sex [3]. In a prospective study from the German SAL-MPN registry that included 455 patients with Ph-negative MPN, 33.6% of patients experienced a vascular event. The most frequent events were deep vein thrombosis (31.5%), acute coronary syndrome (27.7%), stroke (19.3%), and splanchnic vein thrombosis (15.2%) [4]. Ph− MPNs are the most frequent underlying cause of non-cirrhotic Budd Chiari syndrome (~40% of cases) and are identified in approximately one-third of patients with portal vein thrombosis; the JAK2 V617F mutation is present in 80–87% of these patients [5]. Moreover, cardiovascular risk factors and predisposition to thrombosis have been shown to have a positive correlation in Ph− MPN [6].

Despite extensive research, the precise mechanisms driving the prothrombotic state in MPN remain incompletely understood. Thrombosis arises from complex interactions among quantitative and qualitative abnormalities of blood cells, endothelial activation, inflammation, and alterations in the coagulation cascade [7]. The release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), a meshwork of DNA fibers comprising histones and antimicrobial proteins which are extracellular net-like structures composed of modified DNA and associated enzymes such as myeloperoxidase (MPO) and neutrophil elastase among other proteases and lysozymes, has been described as a possible scaffold for thrombus formation [8], with studies suggesting that NET components are present and may contribute to the procoagulant state in these disorders [9] and that platelets and JAK2-V617F neutrophils interact to enhance NET formation [10]. In addition to elevated platelet counts, abnormal platelet function significantly contributes to the prothrombotic state in myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) [11]. Patients with ET and PV exhibit enhanced ADP-induced platelet aggregation and increased thrombin generation, with the most pronounced alterations observed in JAK2 V617F-positive individuals and, paradoxically, in some patients receiving aspirin therapy [12]. An increase in platelet count can be seen in all subtypes of MPN but is particularly present in ET. The level of thrombocytosis has not been proven to significantly correlate with thrombosis risk in essential thrombocythemia [13].

Although the risk of thrombotic complications is evaluated using the current scoring systems, such as in polycythemia vera, which includes age and history of thrombosis, or the IPSET score in essential thrombocythemia, which additionally includes the presence of the JAK2 mutation [14], there remains the question of whether there is room for other markers of hypercoagulability that are easily accessible in everyday clinical practice.

Immature (reticulated) platelets are newly released from megakaryocytes, are larger, contain more dense granules and residual mRNA, and exhibit greater thrombotic potential than mature platelets [15,16].

Elevated immature platelet fraction (IPF) predicts worse outcomes in acute coronary syndromes, ischemic stroke, and after coronary stenting, and correlates with aspirin and clopidogrel resistance [17,18]. Small studies on MPNs have reported increased IPF values, but systematic comparison across subtypes and age groups, and driver mutation status is lacking [19]. The measurement of IPF can help us differentiate platelet destruction conditions, such as ITP or TTP, in comparison to hypoproliferative states [20]. Immature platelets can be measured using supravital dye staining (e.g., new methylene blue) on blood films, or with fluorescent dyes (e.g., thiazole orange) and flow cytometry [21]. Immature platelet fraction measurements obtained using Sysmex automated hematology analyzers show correlation with reticulated platelet counts determined by standard flow cytometry [22].

We therefore conducted a prospective study to characterize IPF in patients newly diagnosed with Ph− MPN, compare it with non-MPN controls, and explore its variation according to subtype, age, and JAK2V617F status in order to evaluate its potential relevance as a marker of hypercoagulability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This prospective observational study was performed at General Hospital Zadar and University Hospital Centre Zagreb, Croatia, between March 2024 and October 2025. All adult patients undergoing diagnostic bone marrow examination for suspected Ph− MPN were eligible. The exclusion criteria comprised previously known MPN, active malignancy, recent surgery/trauma (<4 weeks), acute infection, pregnancy, or any condition known to secondarily elevate IPF (e.g., recent major bleeding).

Diagnoses of PV, ET, PMF, and MPN-unclassified were established in accordance with the International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias [1]. Patients in whom MPN was excluded after a complete work-up constituted the control group. Peripheral blood samples were collected at the time of diagnostic bone marrow biopsy. IPF was measured on Sysmex XN-1000 analyzers (Kobe, Japan) using fluorescent flow cytometry and proprietary RNA-binding polymethine dye. Excellent reproducibility for IPF measurement on the Sysmex XN-1000 was achieved at multiple IPF levels, with coefficients of variation of 3.6% for IPF = 5.3%, 2.0% for IPF = 21.7%, and 1.1% for IPF = 66.2%. Additional laboratory parameters included complete blood count, LDH, urea, creatinine, and D-dimer.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committees of both institutions and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used for the summary presentation of patient characteristics. According to Shapiro–Wilk’s test, the data were not symmetrically distributed; thus, nonparametric statistical tests were used. Continuous variables were compared with the Mann–Whitney U test. Continuous variables were compared across groups using the Kruskal–Wallis test. All analyses were performed using the MedCalc Statistical Software version 23.4.8. (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium). Significant p-values were set at <0.050 for all presented analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Patients Characteristics

Forty-five patients with newly diagnosed Ph− MPN and 27 controls were enrolled.

Among patients with MPN, 24 (53%) patients were diagnosed as having essential thrombocythemia, 13 (28%) patients with polycythemia vera, 5 (11%) with unclassified MPN, and 3 (6%) with primary myelofibrosis. The control group comprised 27 individuals in whom Ph− MPN was excluded. There were 19 (42%) females in the Ph− MPN group and 8 (29%) in the control group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data and patient characteristics.

3.2. Results

Patients with Ph− MPN were significantly older than controls (median 65 vs. 50 years) and had higher platelet counts (median 572 × 109/L vs. 238 × 109/L, p < 0.0001) and LDH (median 226 vs. 178 U/L, p < 0.001). Leukocyte, neutrophil, erythrocyte counts, hemoglobin, and hematocrit did not differ significantly between the groups.

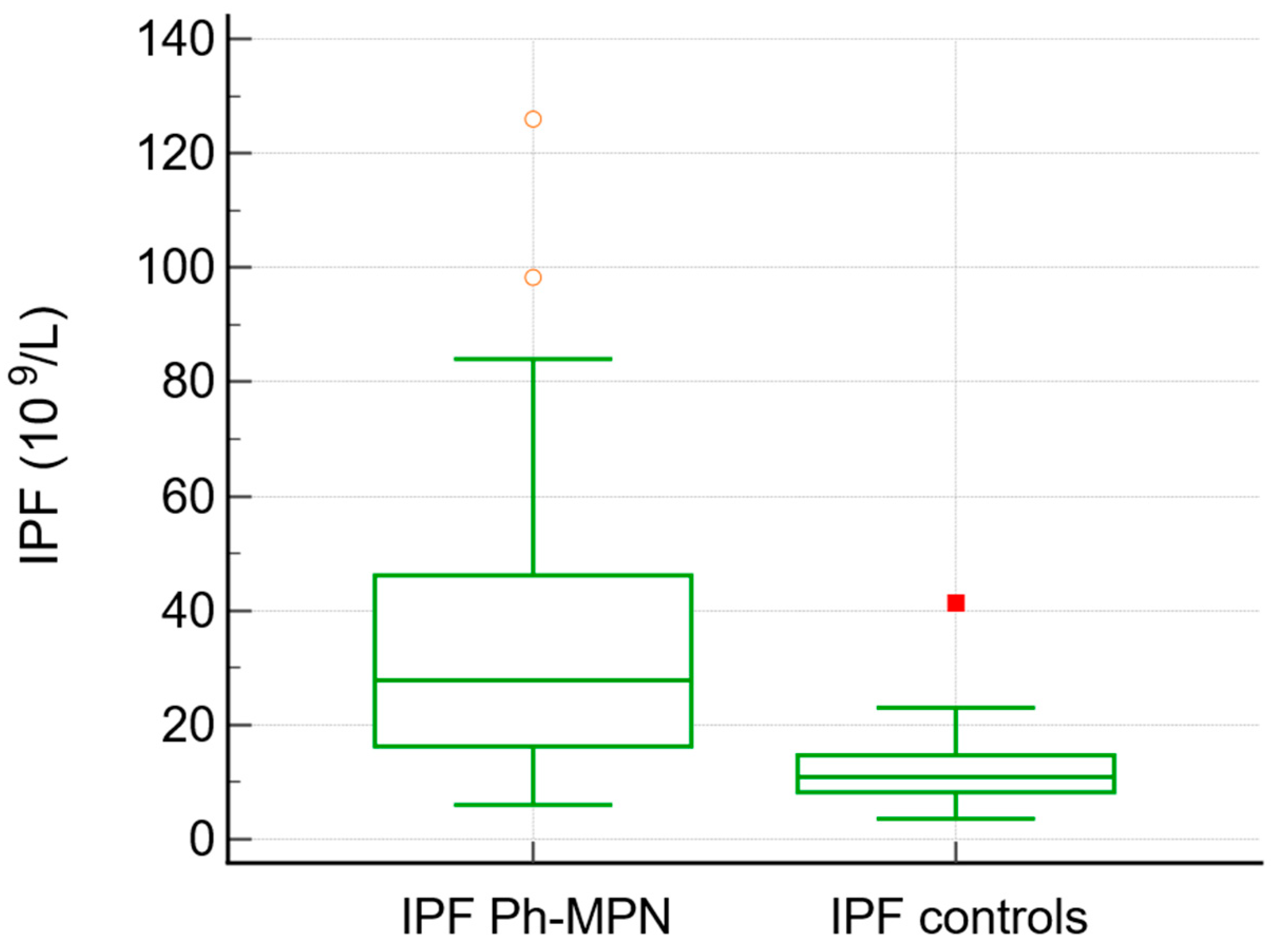

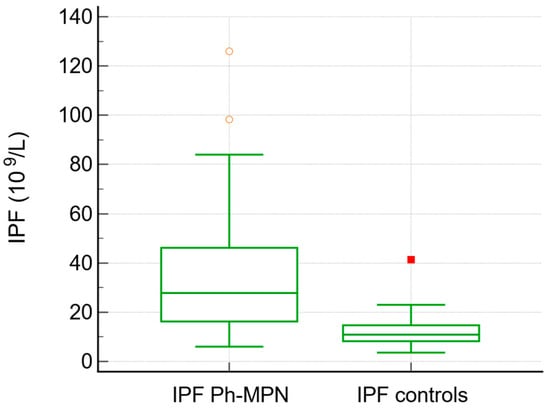

JAK2V617F was positive in 75% of patients with MPN overall (92% of PV, 70% of ET, 66% of PMF, and 80% of unclassified MPN). The IPF values were higher in patients with Ph− MPN (median 27, range 6–126) in comparison to the control group (median 10.9, range 3.6–41, p< 0.0001) (Table 2, Figure 1). Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was significantly higher in patients with MPN compared with controls (median 3.68 vs. 2.68, p = 0.013). Similarly, D-dimer levels were elevated in the MPN group (median 0.50 vs. 0.33, p = 0.048).

Table 2.

Patients with Ph− MPN compared with the control group.

Figure 1.

Box-and-whisker plot. IPF values were higher in patients with Ph− MPN compared to the control group.

No differences were observed in IPF values between JAK2-positive and JAK2-negative patients with MPN (median 26 vs. 40.7, p = 0.25). However, higher values of hematocrit were found among JAK2-positive patients (median 0.47 vs. 0.41, p = 0.032). (Table 3).

Table 3.

JAK2-positive Ph− MPN compared with the JAK2-negative Ph− MPN.

When comparing the patients with Ph− MPN in the age group older than 60 years, we found values of IPF (median 38.8, range 10.2–126) which were higher compared to those in patients with Ph− MPN who were younger than 60 years (median 23.5, range 6–50, p = 0.021), but we did not find any difference in the platelet count between these two age groups (median 572 vs. 604, p = 0.84) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results across age groups of patients with Ph− MPN.

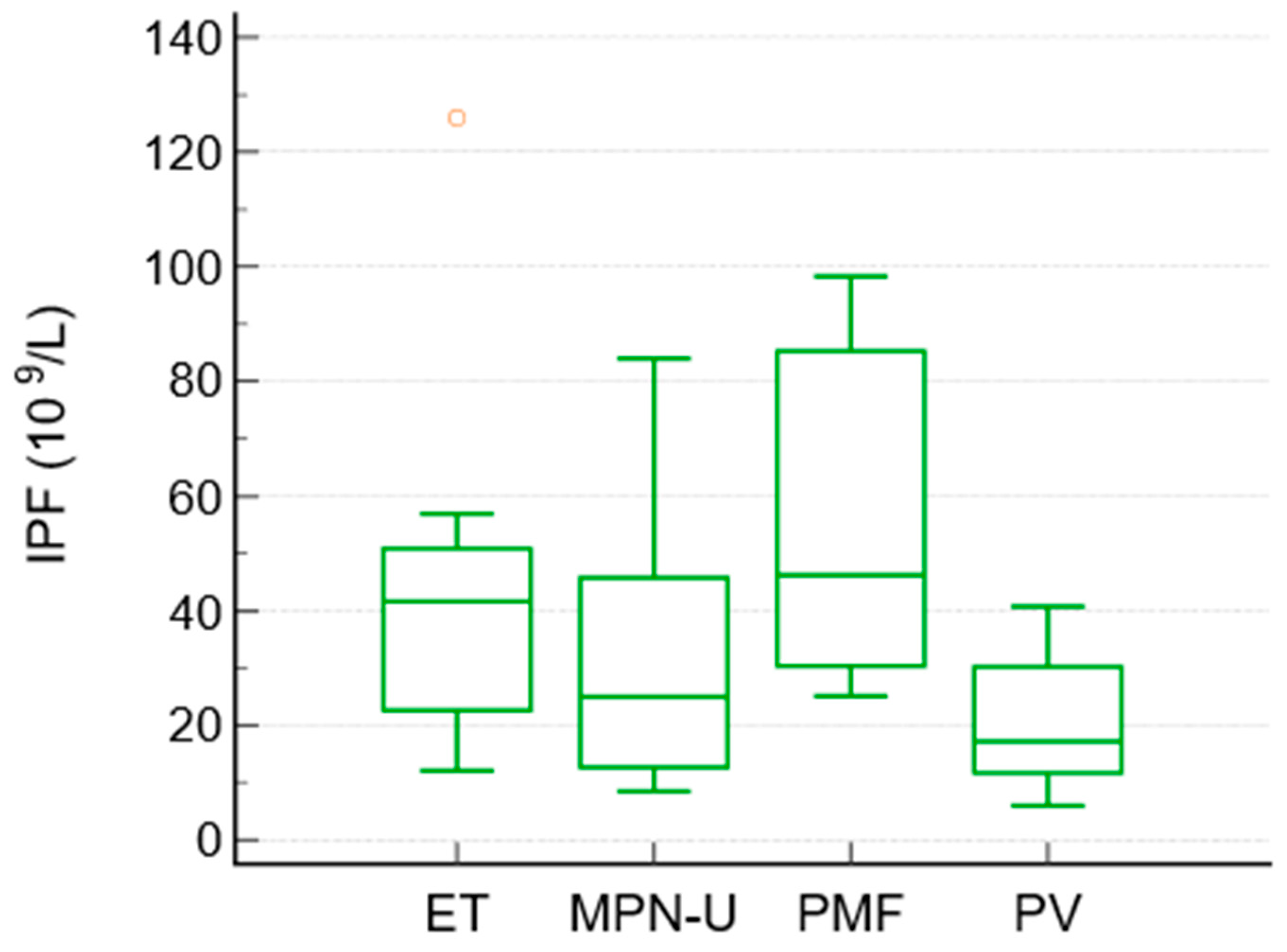

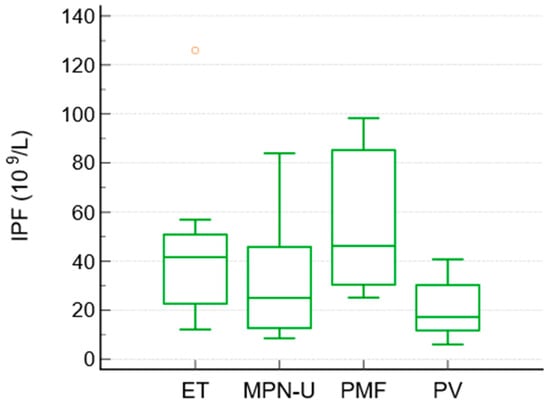

To compare the differences between the subgroups of MPN, a Kruskal–Wallis test was performed. It showed significant differences in IPF between the MPN subgroups (p = 0.027). The median IPF values were highest in essential thrombocythemia and primary myelofibrosis, intermediate in unclassified MPN, and lowest in polycythemia vera. The median IPF values were as follows: ET 41.6, PMF 46.2, MPN-unclassified 25, and PV 17.2 × 109/L. Platelet counts followed the expected pattern (highest in ET and lowest in PV), whereas granulocyte counts were highest in PMF and unclassified MPN.

No other pairwise differences between the subtypes reached statistical significance (Table 5, Figure 2).

Table 5.

IPF values in subtypes of Ph− MPN.

Figure 2.

Box-and-whisker plot. Distribution of IPF among subtypes of Ph− MPN.

4. Discussion

Our study provides a comprehensive analysis of immature platelet fraction in Ph− MPNs. The nearly threefold elevation in IPF in patients with Ph− MPN compared with carefully selected non-MPN controls confirms markedly accelerated thrombopoiesis, even at disease presentation and before cytoreductive therapy.

IPF has shown prognostic relevance in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disorders [17,18], but its role in myeloproliferative neoplasms as a marker of hypercoagulability is not completely understood.

The pathophysiological basis is likely multifactorial. Clonal megakaryocytes in Ph− MPNs exhibit hypersensitivity to thrombopoietin and other cytokines, increased ploidy, and proplatelet formation independent of physiological feedback [23]. The resulting release of young, RNA-rich platelets with heightened metabolic and prothrombotic activities (increased expression of P-selectin, GPIIb/IIIa, and tissue factor, and enhanced response to ADP, thrombin, and shear stress) contributes directly to the hypercoagulable states [24].

Interestingly, the analysis stratified by age revealed that patients with Ph− MPN older than 60 years had significantly higher IPF values than younger patients (median 41.6 vs. 23.6, p = 0.0202). This could suggest that age-related factors, including marrow remodeling and comorbidities, may further amplify dysregulated platelet production in MPN. Importantly, this increase in IPF occurred independently of platelet count, highlighting that conventional platelet numbers may underestimate underlying thrombopoietic activity. Our data could support the concept that IPF reflects qualitative platelet dysfunction better than absolute count alone.

We also identified differences in IPF among MPN subtypes. The Kruskal–Wallis test showed significant heterogeneity, with post hoc analyses demonstrating higher IPF levels in ET and MF compared to PV. In PMF, ineffective hematopoiesis, inflammatory cytokine signaling, and early extramedullary hematopoiesis may further promote the release of immature platelets, while in ET, clonal megakaryocytic proliferation drives increased platelet production [25,26]. The highest platelet count was observed in ET, followed by PMF, and the highest granulocytes values were observed in PMF and unclassified MPN. Among JAK2-positive patients, IPF values differed significantly across the MPN subtypes, with PV showing the lowest values compared with ET and MF.

These findings may reflect the distinct pathophysiology of each MPN subtype. Our findings suggest that IPF could provide additional insight into the biology of platelet production across MPN subtypes and patient subgroups. Elevated IPF in Ph− MPN could support its role as a marker of increased thrombopoietic activity, while the influence of age emphasizes the importance of integrating IPF into broader clinical and biological assessments. Importantly, the lack of correlation with platelet counts could indicate that IPF may capture aspects of platelet dynamics that routine hematology parameters fail to reflect. Previous studies have demonstrated that both JAK2V617F mutational status and hydroxyurea therapy independently influence immature platelet parameters in essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera, which could explain the favorable effect of hydroxyurea therapy on MPN outcome as well as the thrombotic risk [27]. Increased neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was also observed in patients with MPN and could represent either myeloproliferation itself [28] or the degree of chronic inflammation [29], while higher D-dimer levels, particularly in patients older than 60 years, may indicate persistent coagulation activation and endothelial dysfunction characteristic of the prothrombotic MPN phenotype [30].

From a clinical perspective, IPF is measured automatically on widely available hematology platforms without additional cost or phlebotomy. If future longitudinal studies confirm that high IPF identifies patients at increased thrombotic risk, especially within the same conventional risk category, it could refine stratification and guide intensity of cytoreduction or antithrombotic prophylaxis.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. The sample size was relatively small, particularly for the PMF subgroup, which included only three patients, and for the unclassified MPN group, which included only five patients; this limitation restricts the generalizability of the findings within these categories.

The cross-sectional design also precludes conclusions about the prognostic role of IPF. Furthermore, we did not assess correlations between IPF and thrombotic outcomes, which represent a clinically relevant endpoint in MPN. Nevertheless, this study provides novel comparative data on IPF across MPN subtypes and highlights important biological patterns that merit further exploration.

5. Conclusions

IPF is significantly elevated in Philadelphia chromosome-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms and shows subtype- and age-specific patterns. These findings could highlight IPF as a readily available marker of dysregulated thrombopoiesis that may complement conventional hematological parameters. Further studies are warranted to determine whether IPF can improve thrombotic risk stratification in Ph− MPNs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.Z., A.B. (Ana Boban), M.M. (Marija Milos) and T.M.; methodology, I.Z., A.B. (Ana Boban) and J.K.; software, I.Z., A.B. (Ana Boban) and J.K.; validation, I.Z., M.M. (Marija Milos) and A.B. (Ana Boban); formal analysis, I.Z.; investigation, I.Z., T.M., M.M.P., D.Z., A.V., A.B. (Anamarija Bogic), M.M. (Marta Marcinkovic), P.G.P. and L.J.; data curation, I.Z., M.R.A., J.K. and D.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, I.Z., A.B. (Ana Boban) and M.M. (Marija Milos); writing—review and editing, I.Z., A.B. (Ana Boban) and M.M. (Marija Milos); visualization, I.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Ethics Committees of the University Hospital Centre Zagreb (reference number 8.1-24/9-2; 02/013AG, dated 5 February 2024) and General Hospital Zadar (reference number 01-753/24-9/24, dated 2 February 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (Ivan Zekanovic) due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Borowitz, M.J.; Calvo, K.R.; Kvasnicka, H.M.; Wang, S.A.; Bagg, A.; Barbui, T.; Branford, S.; et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: Integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood 2022, 140, 1200–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J. New advances in the role of JAK2 V617F mutation in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Cancer 2024, 130, 4229–4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hultcrantz, M.; Bjorkholm, M.; Dickman, P.W.; Landgren, O.; Derolf, A.R.; Kristinsson, S.Y.; Andersson, T.M.L. Risk for arterial and venous thrombosis in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms: A population-based cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 168, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaifie, A.; Kirschner, M.; Wolf, D.; Maintz, C.; Hänel, M.; Gattermann, N.; Gökkurt, E.; Platzbecker, U.; Hollburg, W.; Göthert, J.R.; et al. Bleeding, thrombosis, and anticoagulation in myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN): Analysis from the German SAL-MPN-registry. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smalberg, J.H.; Arends, L.R.; Valla, D.C.; Kiladjian, J.J.; Janssen, H.L.; Leebeek, F.W. Myeloproliferative neoplasms in Budd-Chiari syndrome and portal vein thrombosis: A meta-analysis. Blood 2012, 120, 4921–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvat, I.; Boban, A.; Zadro, R.; Antolic, M.R.; Serventi-Seiwerth, R.; Roncevic, P.; Radman, I.; Sertic, D.; Vodanovic, M.; Pulanic, D.; et al. Influence of Blood Count, Cardiovascular Risks, Inherited Thrombophilia, and JAK2 V617F Burden Allele on Type of Thrombosis in Patients with Philadelphia Chromosome Negative Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019, 19, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, S.; Falanga, A. Thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms: A clinical and pathophysiological perspective. Thromb. Update 2021, 5, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T.A.; Brill, A.; Duerschmied, D.; Schatzberg, D.; Monestier, M.; Myers, D.D.; Wrobleski, S.K.; Wakefield, T.W.; Hartwig, J.H.; Wagner, D.D. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 15880–15885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin Oyarzún, C.P.; Carestia, A.; Lev, P.R.; Glembotsky, A.C.; Ríos, M.A.C.; Moiraghi, B.; Molinas, F.C.; Marta, R.F.; Schattner, M.; Heller, P.G. Neutrophil extracellular trap formation and circulating nucleosomes in patients with chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, A.; Favre, S.; Labrouche-Colomer, S.; Garcia, G.; Gourdou-Latyszenok, V.; Wolff-Trombini, L.; Josserand, L.; Kimmerlin, Q.; Kilani, B.; Marty, C.; et al. Platelets and neutrophils cooperate to induce increased NETosis in JAK2-V617F MPN. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2024, 22, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, S.; Thompson, C.R.; Belghasem, M.E.; Bekendam, R.H.; Piasecki, A.; Leiva, O.; Ray, A.; Italiano, J.; Yang, M.; Merill-Skoloff, G.; et al. Platelet dysfunction and thrombosis in JAK2(V617F)-mutated primary myelofibrotic mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, e262–e272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panova-Noeva, M.; Marchetti, M.; Russo, L.; Tartari, C.J.; Leuzzi, A.; Finazzi, G.; Rambaldi, A.; Cate, H.T.; Falanga, A. ADP-induced platelet aggregation and thrombin generation are increased in Essential Thrombocythemia and Polycythemia Vera. Thromb. Res. 2013, 132, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, P.J.; MacLean, C.; Beer, P.A.; Buck, G.; Wheatley, K.; Kiladjian, J.-J.; Forsyth, C.; Harrison, C.N.; Green, A.R. Correlation of blood counts with vascular complications in essential thrombocythemia: Analysis of the prospective PT1 cohort. Blood 2012, 120, 1409–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbui, T.; Vannucchi, A.; Buxhofer-Ausch, V.; De Stefano, V.; Betti, S.; Rambaldi, A.; Rumi, E.; Ruggeri, M.; Rodeghiero, F.; Randi, M.L.; et al. Practice-relevant revision of IPSET-thrombosis based on 1019 patients with WHO-defined essential thrombocythemia. Blood Cancer J. 2015, 5, e369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, E.I. Immature Platelets: Clinical Relevance and Research Perspectives. Circulation 2016, 134, 987–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hille, L.; Lenz, M.; Vlachos, A.; Grüning, B.; Hein, L.; Neumann, F.J.; Nührenberg, T.G.; Trenk, D. Ultrastructural, transcriptional, and functional differences between human reticulated and non-reticulated platelets. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 2034–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grove, E.L.; Hvas, A.M.; Kristensen, S.D. Immature platelets in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Thromb. Haemost. 2009, 101, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, T.; Uchiyama, S.; Yamazaki, M.; Okubo, K.; Takakuwa, Y.; Iwata, M. Flow cytometric analysis of reticulated platelets in patients with ischemic stroke. Thromb. Res. 2002, 106, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryningen, A.; Apelseth, T.; Hausken, T.; Bruserud, Ø. Reticulated platelets are increased in chronic myeloproliferative disorders, pure erythrocytosis, reactive thrombocytosis and prior to hematopoietic reconstitution after intensive chemotheapy. Platelets 2006, 17, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, Y.; Wada, H.; Tomatsu, H.; Sakaguchi, A.; Nishioka, J.; Yabu, Y.; Onishi, K.; Nakatani, K.; Morishita, Y.; Oguni, S.; et al. A simple technique to determine thrombopoiesis level using immature platelet fraction (IPF). Thromb. Res. 2006, 118, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.; Robinson, M.S.; Mackie, I.J.; Machin, S.J. Reticulated platelets. Platelets 1997, 8, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, I.; Monteagudo, M.; Lucchetti, G.; Muñoz, L.; Perea, G.; Colomina, I.; Guiu, J.; Obiols, J. Correlation between immature platelet fraction and reticulated platelets. Usefulness in the etiology diagnosis of thrombocytopenia. Eur. J. Haematol. 2010, 85, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briere, J.; Kiladjian, J.J.; Peynaud-Debayle, E. Megakaryocytes and platelets in myeloproliferative disorders. Baillieres Clin. Haematol. 1997, 10, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Soleimani Samarkhazan, H. Immature platelet fraction in cardiology. Clin. Chim. Acta 2026, 579, 120600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tefferi, A. Primary myelofibrosis: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, 801–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefferi, A.; Vannucchi, A.; Barbui, T. Essential thrombocythemia: 2024 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2024, 99, 697–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panova-Noeva, M.; Marchetti, M.; Buoro, S.; Russo, L.; Leuzzi, A.; Finazzi, G.; Rambaldi, A.; Ottomano, C.; Ten Cate, H.; Falanga, A. JAK2V617F mutation and hydroxyurea treatment as determinants of immature platelet parameters in essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera patients. Blood 2011, 118, 2599–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucijanic, M.; Cicic, D.; Stoos-Veic, T.; Pejsa, V.; Lucijanic, J.; Fazlic Dzankic, A.; Vlasac Glasnovic, J.; Soric, E.; Skelin, M.; Kusec, R. Elevated Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte-ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Myelofibrosis: Inflammatory Biomarkers or Representatives of Myeloproliferation Itself? Anticancer Res. 2018, 38, 3157–3163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buonacera, A.; Stancanelli, B.; Colaci, M.; Malatino, L. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio: An Emerging Marker of the Relationships between the Immune System and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 26, 3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falanga, A.; Marchetti, M. Thrombotic disease in the myeloproliferative neoplasms. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2012, 2012, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.