Pilot Exploratory Study of Serum Differential Scanning Calorimetry in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Reveals Preliminary Outcome-Related Proteome-Level Thermodynamic Patterns

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Sampling and Analysis of Investigated Body Fluids

2.3. DSC Measurements

3. Results

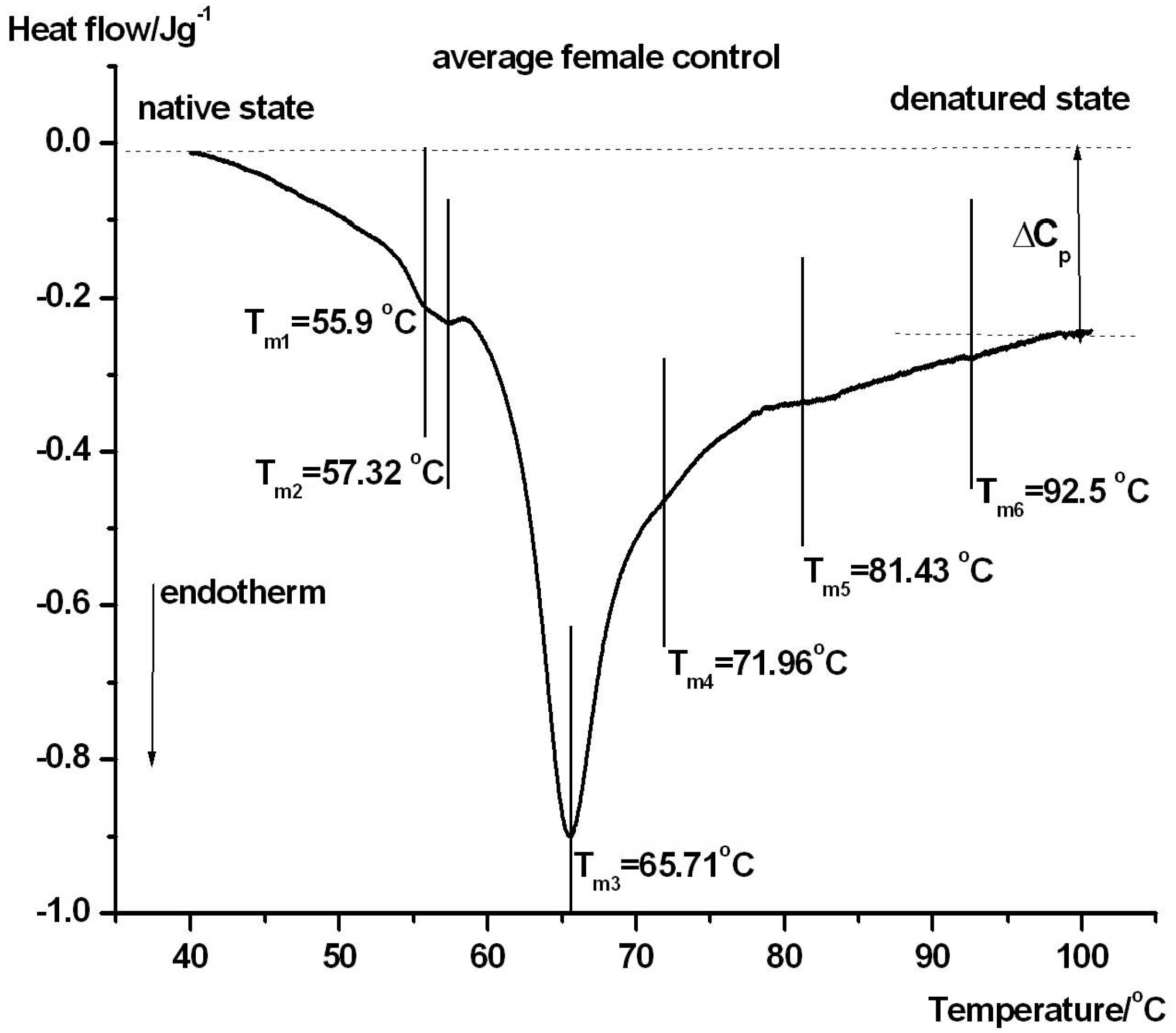

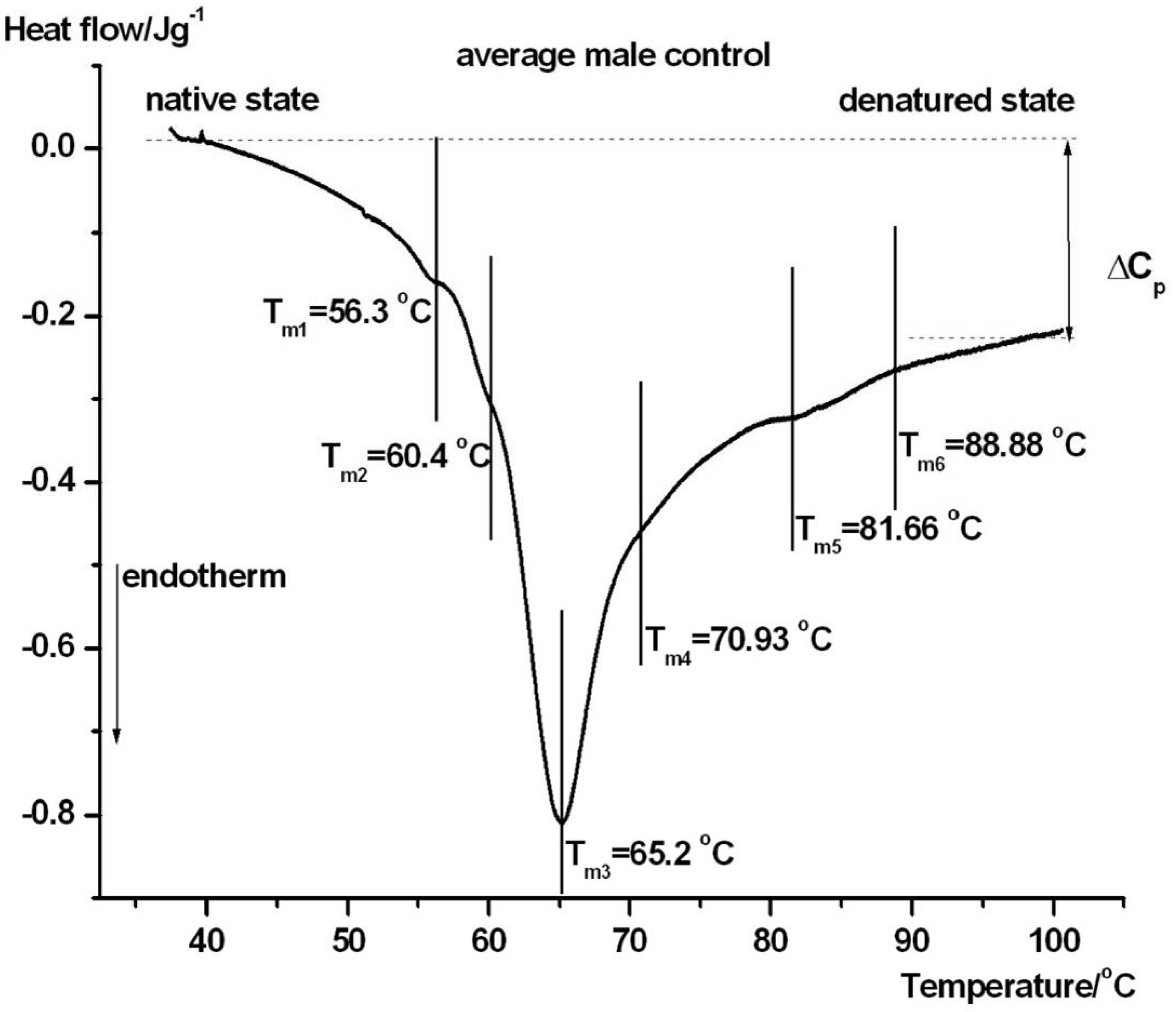

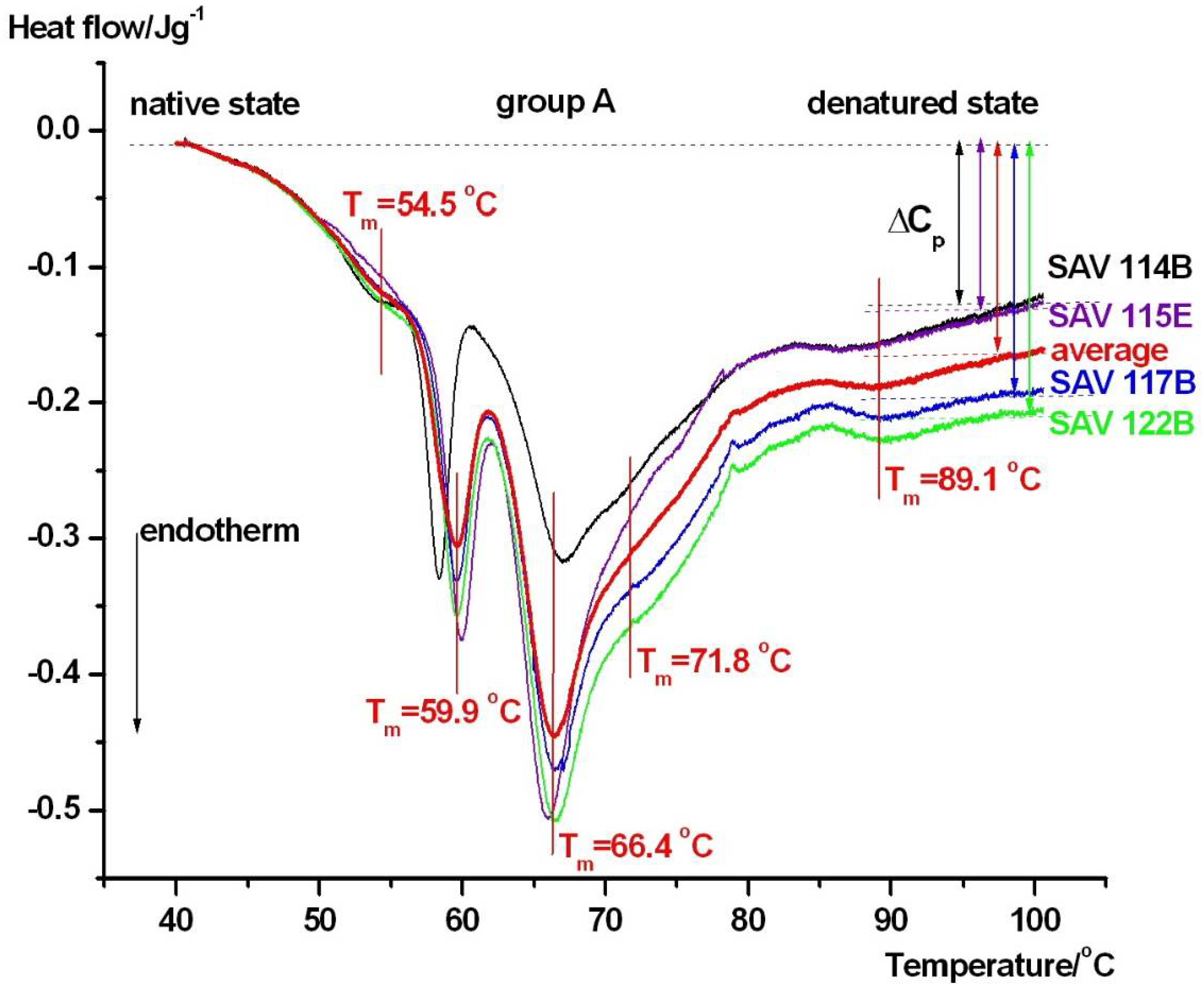

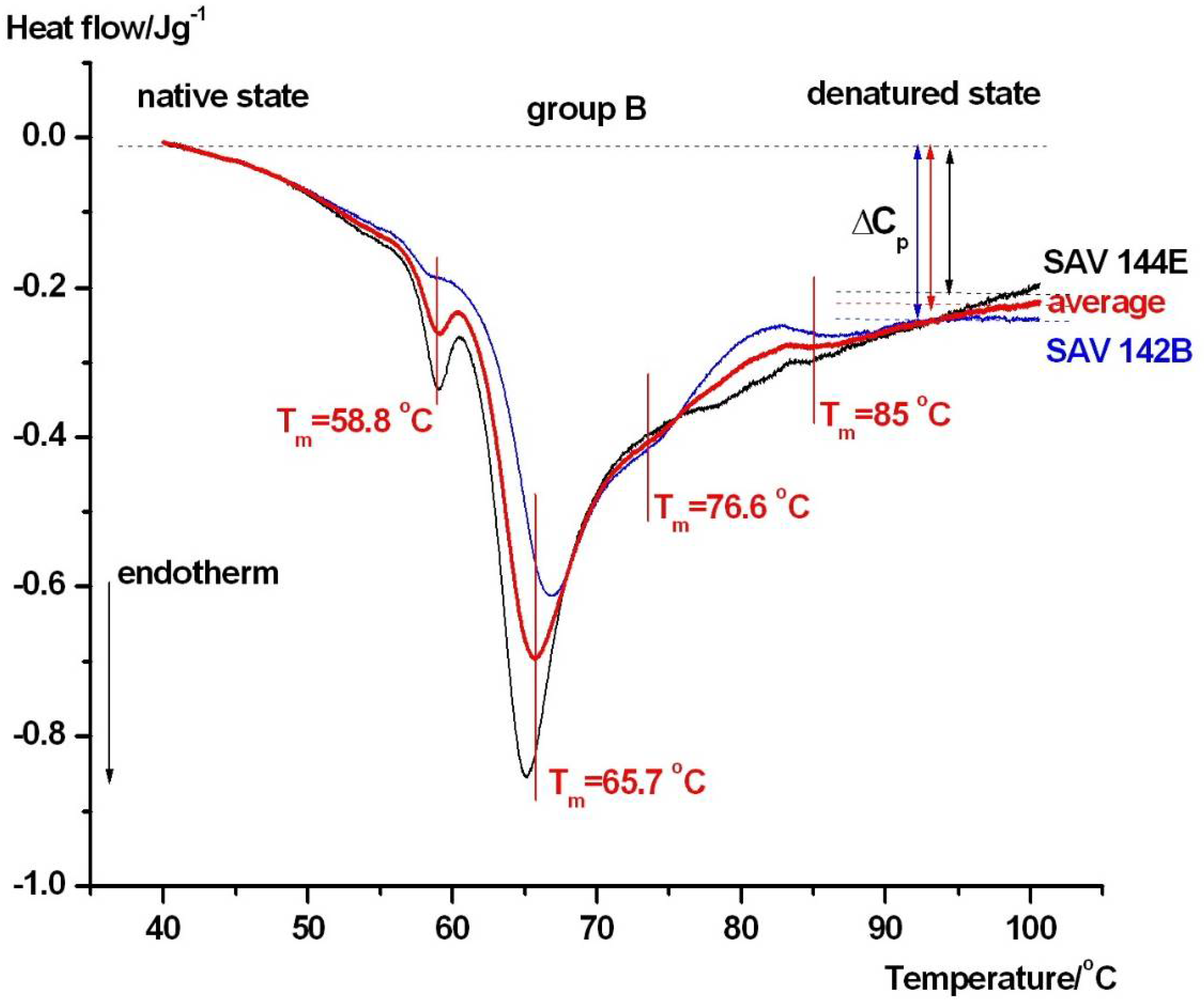

DSC Measurements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aSAH | aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| CT | computed tomography |

| CTA | computed tomography angiography |

| DCI | delayed cerebral ischemia |

| DSA | digital subtraction angiography |

| DSC | differential scanning calorimetry |

| ΔCp | change in heat capacity |

| ΔHcal | calorimetric enthalpy |

| EVD | external ventricular drain |

| HSA | human serum albumin |

| IgA | immunoglobulin A |

| IgG | immunoglobulin G |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| mFisher | modified Fisher score |

| MR | magnetic resonance |

| mRS | modified Rankin Scale |

| SD | standard deviation |

| Tm | melting denaturation temperature |

| WFNS | World Federation of Neurological Societies |

References

- Ziu, E.; Khan Suheb, M.Z.; Mesfin, F.B. Subarachnoid hemorrhage. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441958/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Andreasen, T.H.; Bartek, J., Jr.; Andresen, M.; Springborg, J.B.; Romner, B. Modifiable risk factors for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2013, 44, 3607–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.F.; Qiu, H.C.; Su, J.; Jiang, W.J. Drug treatment of cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage following aneurysms. Chin. Neurosurg. J. 2016, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robba, C.; Busl, K.M.; Claassen, J.; Diringer, M.N.; Helbok, R.; Park, S.; Rabinstein, A.; Treggiari, M.; Vergouwen, M.D.I.; Citerio, G. Contemporary management of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: An update for the intensivist. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 50, 646–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrone, J.C.; Maekawa, H.; Tjahjadi, M.; Hernesniemi, J. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Pathobiology, current treatment and future directions. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2015, 15, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, A.; Ojeda, J.L.; Vega, S.; Sanchez-Gracia, O.; Lanas, A.; Isla, D.; Velazquez-Campoy, A.; Abian, O. Thermal liquid biopsy (TLB): A predictive score derived from serum thermograms as a clinical tool for screening lung cancer patients. Cancers 2019, 11, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annesi, F.; Hermoso-Durán, S.; Rizzuti, B.; Bruno, R.; Pirritano, D.; Petrone, A.; Del Giudice, F.; Ojeda, J.; Vega, S.; Sanchez-Gracia, O.; et al. Thermal liquid biopsy (TLB) of blood plasma as a potential tool for early diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R.R.; Keane, R.W.; Guardiola, B.; López-Lage, S.; Moratinos, L.; Dietrich, W.D.; Perez-Barcena, J.; de Rivero Vaccari, J.P. Inflammasome proteins are reliable biomarkers of the inflammatory response in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cells 2024, 13, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reger, K.C.; Schneider, G.; Line, K.T.; Kaliappan, A.; Buscaglia, R.; Garbett, N.C. Automated baseline-correction and signal-detection algorithms with web-based implementation for thermal liquid biopsy data analysis. Cancers 2026, 18, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaselidze, J.; Kalandadze, Y.; Topuridze, I.; Gadabadze, M. Thermodynamic properties of serum and plasma of patients with cancer. High Temp. Press. 1997, 29, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, K.A. The delayed diagnosis of breast cancer: Medicolegal implications and risk prevention for surgeons. Breast Dis. 2001, 12, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagovetz, A.A.; Jensen, R.L.; Recht, L.; Glantz, M.; Chagovetz, A.M. Preliminary use of differential scanning calorimetry of cerebrospinal fluid for the diagnosis of glioblastoma multiforme. J. Neurooncol. 2011, 105, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagovetz, A.A.; Quinn, C.; Damarse, N.; Hansen, L.D.; Chagovetz, A.M.; Jensen, R.L. Differential scanning calorimetry of gliomas: A new tool in brain cancer diagnostics? Neurosurgery 2013, 73, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumova, S.; Rukova, B.; Todinova, S.; Gartcheva, L.; Milanova, V.; Toncheva, D.; Taneva, S.G. Calorimetric monitoring of the serum proteome in schizophrenia patients. Thermochim. Acta 2013, 572, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikalishvili, L.; Ramishvili, M.; Nemsadze, G.; Lezhava, T.; Khorava, P.; Gorgoshidze, M.; Kiladze, M.; Monaselidze, J. Thermal stability of blood plasma proteins of breast cancer patients: A DSC study. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2015, 120, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danailova, A.; Todinova, S.; Dimitrova, K.; Petkova, V.; Guenova, M.; Mihaylov, G.; Gartcheva, L.; Krumova, S.; Taneva, S. Effect of autologous stem-cells transplantation of patients with multiple myeloma on the calorimetric markers of the serum proteome. Correlation with the immunological markers. Thermochim. Acta 2017, 655, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Campoy, A.; Vega, S.; Sanchez-Gracia, O.; Lanas, A.; Rodrigo, A.; Kaliappan, A.; Hall, M.B.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Brock, G.N.; Chesney, J.A.; et al. Thermal liquid biopsy for monitoring melanoma patients under surveillance during treatment: A pilot study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2018, 1862, 1701–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krumova, S.; Todinova, S.; Taneva, S.G. Calorimetric markers for detection and monitoring of multiple myeloma. Cancers 2022, 14, 3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michnik, A. Thermal stability of bovine serum albumin: A DSC study. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2003, 71, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbett, N.C.; Miller, J.J.; Jenson, A.B.; Chaires, J.B. Calorimetry outside the box: A new window into the plasma proteome. Biophys. J. 2008, 94, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbett, N.C.; Mekmaysy, C.; Helm, C.V.; Jenson, A.B.; Chaires, J.B. Differential scanning calorimetry of blood plasma for clinical diagnosis and monitoring. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2009, 86, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svedung Wettervik, T.; Hånell, A.; Ronne-Engström, E.; Lewén, A.; Enblad, P. Temperature changes in poor-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Relation to injury pattern, intracranial pressure dynamics, cerebral energy metabolism, and clinical outcome. Neurocrit. Care 2023, 39, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Donkelaar, C.E.; Bakker, N.A.; Birks, J.; Veeger, N.J.G.M.; Metzemaekers, J.D.M.; Molyneux, A.J.; Groen, R.J.M.; van Dijk, J.M.C. Prediction of outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2019, 50, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergouwen, M.D.; Ilodigwe, D.; Macdonald, R.L. Cerebral infarction after subarachnoid hemorrhage contributes to poor outcome by vasospasm-dependent and -independent effects. Stroke 2011, 42, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VVergouwen, M.D.; Vermeulen, M.; van Gijn, J.; Rinkel, G.J.; Wijdicks, E.F.; Muizelaar, J.P.; Mendelow, A.D.; Juvela, S.; Yonas, H.; Terbrugge, K.G.; et al. Definition of delayed cerebral ischemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage as an outcome event in clinical trials and observational studies. Stroke 2010, 41, 2391–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, M.; Ferencz, A.; Lőrinczy, D. Evaluation of blood plasma changes by differential scanning calorimetry in psoriatic patients treated with drugs. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2014, 116, 557–562. [Google Scholar]

- Zapf, I.; Moezzi, M.; Fekecs, T.; Nedvig, K.; Lőrinczy, D.; Ferencz, A. Influence of oxidative injury and monitoring of blood plasma by DSC on breast cancer patients. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2016, 123, 2029–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferencz, A.; Lőrinczy, D. DSC measurements of blood plasma on patients with chronic pancreatitis, operable and inoperable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 127, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferencz, A.; Szatmári, D.; Lőrinczy, D. Thermodynamic sensitivity of blood plasma components in patients with skin, breast, and pancreas cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferencz, A.; Moezzi, M.; Lőrinczy, D. Investigation of the efficacy of antipsoriatic drugs by blood plasma thermoanalysis. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2024, 149, 11485–11491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaselidze, J.; Nemsadze, G.; Gorgoshidze, M. Differential Scanning Microcalorimeter Device for Detecting Disease and Monitoring Therapeutic Efficacy. U.S. Patent Application US20190003995A1, 3 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lucke-Wold, B.P.; Logsdon, A.F.; Manoranjan, B.; Turner, R.C.; McConnell, E.; Vates, G.E.; Huber, J.D.; Rosen, C.L.; Simard, J.M. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and neuroinflammation: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.L.; Morgan, W.T. Characterization of hemopexin and its interaction with heme by differential scanning calorimetry and circular dichroism. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 7216–7222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Samples | Tm1/°C | Tm2/°C | Tm3/°C | Tm4/°C | Tm5/°C | Tm6/°C | ΔHcal/Jg−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ctr. male | 56.3 ± 0.4 | 60.4 ± 0.3 | 65.2 ± 0.3 | ~71 ± 0.3 | 81.7 ± 0.2 | 88.9 ± 0.5 | 1.51 ± 0.07 |

| ctr. female | 55.9 ± 0.3 | 57.3 ± 0.5 | 65.7 ± 0.2 | ~72 ± 0.4 | 81.4 ± 0.3 | 92.5 ± 0.4 | 1.35 ± 0.06 |

| group A | 54.5 ± 0.4 | 59.9 ± 0.4 | 66.4 ± 0.2 | 71.8 ± 0.3 | - | 89.1 ± 0.4 | 1.09 ± 0.05 |

| group B | - | 58.8 ± 0.3 | 65.7 ± 0.3 | 76.6 ± 0.5 | - | 85 ± 0.4 | 1.27 ± 0.06 |

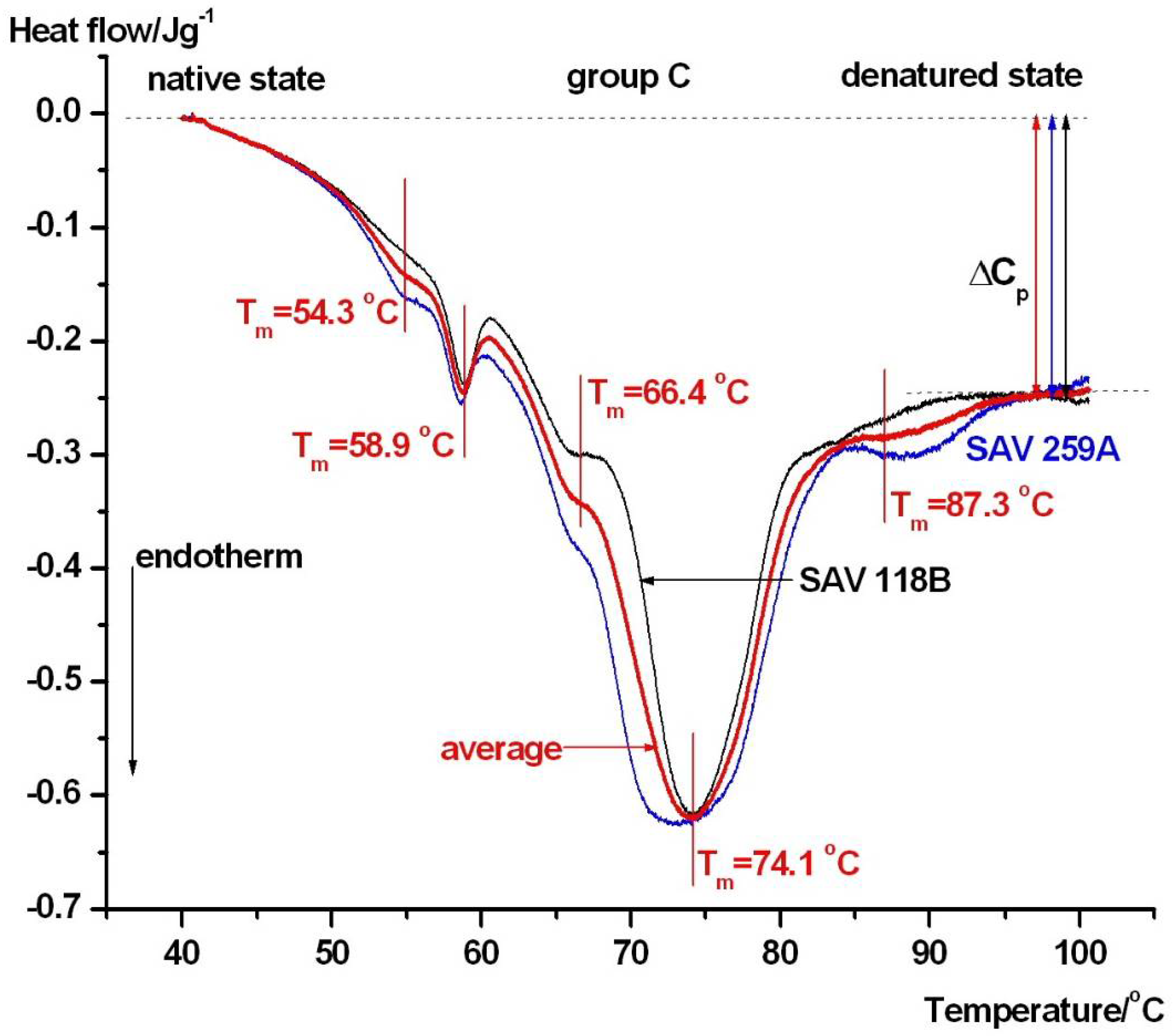

| group C | 54.3 ± 0.4 | 58.9 ± 0.3 | 66.4 ± 0.3 | 74.1 ± 0.4 | - | 87.3 ± 0.05 | 1.41 ± 0.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lőrinczy, D.; Csecsei, P. Pilot Exploratory Study of Serum Differential Scanning Calorimetry in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Reveals Preliminary Outcome-Related Proteome-Level Thermodynamic Patterns. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031139

Lőrinczy D, Csecsei P. Pilot Exploratory Study of Serum Differential Scanning Calorimetry in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Reveals Preliminary Outcome-Related Proteome-Level Thermodynamic Patterns. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031139

Chicago/Turabian StyleLőrinczy, Dénes, and Peter Csecsei. 2026. "Pilot Exploratory Study of Serum Differential Scanning Calorimetry in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Reveals Preliminary Outcome-Related Proteome-Level Thermodynamic Patterns" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031139

APA StyleLőrinczy, D., & Csecsei, P. (2026). Pilot Exploratory Study of Serum Differential Scanning Calorimetry in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Reveals Preliminary Outcome-Related Proteome-Level Thermodynamic Patterns. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031139