Abstract

The acute phase of pulmonary embolism (PE) may be a severe and potentially life-threatening condition. Moreover, long-term consequences following the acute phase can significantly impact a patient’s daily life. A systematic approach to PE follow-up can identify potential complications following acute PE. Post-PE syndrome (PPES) is a common occurrence among survivors experiencing persistent dyspnea and impaired functional status. While the exact definition is evolving, it encompasses a spectrum of disease phenotypes that may occur following an acute PE, which ranges from dyspnea, functional limitation, or cardiac impairment to chronic thromboembolic disease and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. This review will describe the different PPES phenotypes, including their physiological basis, diagnosis and workup, and management following acute PE.

1. Introduction

1.1. Definition

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) affects around 900,000 people yearly in the United States alone, and it is the third leading cause of cardiovascular mortality in the world [1,2,3,4]. In recent years, there has been growing focus on management of acute PE, with advances in diagnostic techniques, sophisticated risk stratification, and increased therapeutic alternatives [5,6]. However, as clinicians become more versed in acute inpatient PE care, it is important to consider the post-acute phase, its long-term outcomes, and its quality of life and morbidity implications.

Approximately half of patients that have had an acute PE will experience some degree of exercise intolerance and dyspnea post PE [6]. Up to 30% of patients have persistent clots, 10–30% have cardiopulmonary limitation, and 0.5–4% will develop chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) [7,8]. While its definition is still evolving, the term post-PE syndrome (PPES) has been used recently to describe a range of subjective symptoms of persistence of dyspnea, exercise limitation, and impaired quality of life (QoL), as well as objective cardiopulmonary limitations following an acute PE [9]. While pathophysiology and management are not well understood, close follow-up is crucial given its implications in morbidity and mortality. PPES encompasses post-PE dyspnea or cardiac impairment, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease (CTEPD), and CTEPH. Herein, we will discuss the evolving phenotypes of PPES, including diagnosis, management, and prognostic implications.

1.2. Pathobiology Post PE

After an acute PE, the principal components of an acute thrombus, namely erythrocytes and fibrin, are naturally degraded. Fibrin degradation into d-dimers starts soon after the formation of a thrombus and is evident in 80% of patients within a week, up to 40% within 1 month, and only 13% at 3 months [10]. Erythrocytes usually expire within 2–4 months and are degraded by circulating macrophages. Impaired fibrinolysis, altered fibrinogen structure and function, increased local or systemic inflammation, and remodeling of the embolic material by neovascularization have been implicated in failure of clot resolution. Inflammation and hypoxia-induced signaling appear to be central to the persistence of thrombotic disease and failure of clot resolution, as evidenced by the elevation in macrophages and T-cell-mediated inflammation, as well as elevated circulating inflammatory mediators such as CRP, TNF-a, CXCL-10, IL-2, IL-4, IL-8, and IL-10.

1.3. Phenotypes of Post-Pulmonary Embolism Syndrome

Table 1 provides the various clinical phenotypes of PPES. Post-PE dyspnea or functional impairment is defined as the persistence of dyspnea, exercise intolerance, or decreased functional status after an acute PE, in the absence of an alternate explanation. It is postulated that decreased physical activity after PE and deconditioning contribute to the persistence of exercise intolerance in most patients [11]. Pain, anxiety, fear of recurrence, and comorbidities, such as obesity and other cardiopulmonary conditions, may also contribute and lead to the avoidance of exercise and reduced quality of life. When compared to patients without a history of venous thromboembolism (VTE), patients with an acute episode of PE are more likely to report NYHA class II (OR 3.6 95%CI 1.4–9.7) and class III or IV (OR 6.5 95%CI 1.7–24) dyspnea, when controlled for gender and age [12,13]. Across multiple studies, survivors of an acute PE report a lower QoL secondary to dyspnea [14].

Table 1.

Phenotypes of post-pulmonary embolism syndrome.

Persistent right ventricular (RV) hypokinesis, dysfunction, or dilation without evidence of pulmonary hypertension (PH), in the absence of an alternate explanation, after 3 months following acute PE is termed post-PE cardiac impairment [15]. Up to 50% of all patients with acute PE may present with cardiac impairment [16], and up to a fourth may have persistent impairment after three months [17]. Despite timely and effective anticoagulation in the acute setting, a combination of initial ischemic insult, inflammation, and structural remodeling has been implicated in this persistent dysfunction [8,18,19,20].

CTEPD refers to persistent thrombosis causing pulmonary vascular obstruction without PH at rest measured on a right heart catheterization (RHC). Complete radiographic resolution of thrombus on a computed tomography angiogram (CTA) was reported in 84% of patients at 6 months post diagnosis. Another study reported persistent perfusion defects on a Ventilation/Perfusion (VQ) scan in 29% of patients after 1 year following adequate anticoagulation. Clot persistence leads to functional dead space, disturbances in gas exchange, and ineffective ventilation. CTEPD symptoms may range from mild dyspnea to severe cardiopulmonary limitations with evidence of PH with exercise. Older age (>65 years), unprovoked PE, a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic respiratory failure, and VTE are independent risk factors for its development [10,11].

The most severe complication following acute PE is CTEPH. It is defined as persistent thrombosis causing resting pulmonary arterial hypertension (mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) above 20 mmHg, pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PCWP) of less than 15 mmHg, and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) equal to or greater than 2, on an RHC). Non-resolving organizing thrombus and microvascular changes in the circulation lead to increased PVR and development of PH. The development of CTEPH ranges from 0.4 to 10% in patients that survived an episode of acute PE.

The FOCUS study, a large prospective multicenter observational study conducted across multiple tertiary care centers in Germany, tracked 1017 patients with acute PE over a two-year follow-up period. The estimated incidence of CTEPH was 2.3%. More notably, the study identified that 116 patients (13.2%) experienced post-PE impairment, characterized by either a worsening or a persistently high severity in echocardiographic findings alongside at least one clinical, functional, or laboratory parameter. These assessments were conducted during follow-up visits at 3, 12, or 24 months, providing a comprehensive view of the patients’ health trajectory post PE [13].

2. Diagnosis

Outpatient follow-up after acute PE with a thorough interview is indispensable to identify PPES and guide the clinician in determining follow-up testing. The timing of follow-up visits depends on the patient’s severity at presentation and hospital resources. The Pulmonary Embolism Response Team (PERT) Consortium consensus guidelines on the treatment and follow-up of acute PE recommends a visit between 2 weeks and 3 months after acute PE, while the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines suggest a visit between 3 and 6 months [5,21].

The initial visit should include symptom evaluation, review of anticoagulation (dosing, possible drug interactions, expected duration), establishment of the need for follow-up testing along with the timeline, and review of indications for additional testing, such as hypercoagulable disorders and age-appropriate cancer screening. Patients should be evaluated for persistent dyspnea, decreased exercise tolerance, chest pain, dizziness, edema, lightheadedness, and/or syncope, and if present, follow-up testing should be pursued. Most patients do not repeat testing before 3 months of effective anticoagulation.

2.1. Symptom Evaluation

Symptom screening, focusing on dyspnea and exercise tolerance, is performed using directed questions, regardless of the PE severity during original presentation. Validated tools such as the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) score [22] help provide a comparison to the pre-PE baseline. The SF-36 questionnaire consists of 36 questions that assess a patient’s perceptions of their physical and mental health over the preceding four weeks [23]. The PE Quality of Life Questionnaire (PEmb-QOL) is a validated forty-question tool that covers six areas, including the frequency and severity of symptoms, and how they affect the patient’s emotions, daily activities, work, and social life [24], that may be useful in the identification of patients requiring further evaluation [25]. A recently developed scale, the post-venous thromboembolism functional status (PVFS) scale [26], includes the level of care a person may require, ability to complete activities of daily living, participation in social roles, and any residual symptoms.

Each tool has its unique characteristics and limitations when used in the identification of PPES. The mMRC score is highly sensitive in the detection of dyspnea severity in symptomatic patients; however, it is limited in identifying patients with objective exercise limitation in the absence of symptoms. The SF-36 is good at capturing generic physical and mental health deficits but is not specific to PPES. PEmb-QoL, however, is PE-specific and is a reliable instrument that can be cumbersome to administer given its 40 scoring items. In contrast, the PVFS is practical and brief but has limited direct validation in PPES.

Routine use of most functional scores may be challenging to implement in clinical practice, but overall, these scores highlight the importance of symptom-based screening for post-PE phenotypes.

2.2. Psychological Sequelae After PE

The psychological impact of PE is a key component of post-PE syndrome and represents an important but underrecognized domain of survivorship. Pulmonary embolism (PE) is increasingly recognized not only as a life-threatening acute event but also as a condition with substantial long-term sequelae. Beyond the well-documented physical consequences such as post-PE dyspnea, exercise limitation, and CTEPH, survivors frequently experience profound psychological effects. These sequelae include anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)-like symptoms, which may persist long after resolution of the acute thrombotic episode. Collectively, these manifestations are encompassed within the framework of post-PE syndrome.

Although ongoing research continues to explore the psychological impact of venous thromboembolism (VTE), significant gaps remain in our understanding of emotional and mental well-being in this population. Multiple studies have demonstrated that patients with PE have higher rates of depression and anxiety compared with the general population [27]. Survivors often report poor mental health as measured by health-related quality of life questionnaires [28], with mood disturbances compounding the physical limitations imposed by the thromboembolic event [29].

PE is frequently described by patients as a “life-changing diagnosis”. Survivors may articulate a sense of lost identity, intrusive thoughts, and the need to adjust to new functional restrictions. Emotional responses often include insecurity about recognizing or managing future symptoms, perceived loss of invincibility, and shifts in self-perception [30]. Many individuals describe living in a state of hypervigilance, characterized by persistent worry or fear of recurrence. The symptoms of hypervigilance and fear of recurrence often lead patients to question whether prescribed medications are working. In addition, the development of symptoms similar to those of initial VTE (dyspnea, leg pain, chest discomfort), for example, may lead to unnecessary imaging and use of resources such as repeated emergency room evaluations.

One specific psychological response increasingly described in the literature is post-thrombotic panic syndrome, defined by hypervigilance to bodily sensations and cyclically triggered emotional distress. Patients report fear of recurrence, flashbacks, and intrusive thoughts related to their initial PE event. These symptoms, in severe forms, may meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD [31].

PTSD following PE is not uncommon and may present with avoidance behaviors, nightmares, hyperarousal, and emotional numbing. If unrecognized, these symptoms can severely impair recovery, social reintegration, and overall quality of life. Early recognition and systematic assessment are therefore critical.

During follow-up visits, clinicians should explicitly inquire about emotional health, including symptoms of anxiety, depression, and PTSD-like features. These symptoms often emerge within the first few months after diagnosis but can persist for years if untreated. Early identification allows for timely referral to supportive interventions. The Pulmonary Embolism Quality of Life (PEmb-QoL) Questionnaire captures both physical and emotional sequelae and can be utilized as a structured screening to help identify patients who may benefit from referral to mental health professionals [32].

In the ELOPE study, a study of 100 consecutive patients that were followed up with post PE, patients had an overall improvement in their mean SF-36 physical and mental components, and PEmb-QoL, over the course of the year following an acute PE.

In addition to dyspnea and functional limitations, psychological complications following acute PE diagnosis are also common. In a recent large German cohort, one in five patients diagnosed with acute PE were also found to have depression or anxiety. Risk factors for its development were older age, higher simplified PE score index (sPESI), higher education level, lower oxygen saturation, and longer hospitalization [33,34], as well as patients’ lack of knowledge on post-PE care [35].

3. Exercise Capacity Evaluation

3.1. Six-Minute Walk Test

The 6 min walk test (6MWT) is a simple measure of exercise capacity utilized in clinical practice and research that has been validated to predict outcomes in pulmonary vascular disease [36]. In a study of 205 patients with intermediate-risk PE, individuals underwent a 6MWT and echocardiography six months after the initial event. Findings revealed that 41% had cardiopulmonary abnormalities at follow-up: 17% showed abnormal RV function, 17% had functional limitations in the 6MWT, and 8% had both. Patients with these abnormalities experienced a significant drop in oxygen saturation (SaO2%) during the 6MWT [8]. Similarly, patients without dyspnea following an acute PE performed better on a 6MWT (488 m vs. 413 m, p < 0.005) and had better HRQoL results when compared to patients that complained of dyspnea [37].

3.2. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing

A cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) is a noninvasive method to assess functional capacity and exercise limitation. During a CPET, gas exchange abnormalities are related to alveolar hypoperfusion relative to ventilation [12,33]. Post-PE functional impairment may be characterized by a normal or near-normal physiologic dead space (VD/VT) and a reduced oxygen uptake (VO2) at an anaerobic threshold, indicating deconditioning as a major contributor to post-PE functional impairment [33,38,39]. A reduced VO2 max, seen typically in left ventricular dysfunction, may not be predictive of RV dysfunction or defects in lung perfusion, but may be indicative of inadequate cardiac contractility to surmount increased pulmonary pressures for chronic vascular obstruction. With exercise, patients with CTEPD may have reduced peak oxygen uptake (VO2), elevated dead space (VD/VT), impaired perfusion (lower end-tidal carbon dioxide (PETCO2)), a reduced anaerobic threshold (AT), inefficient ventilation (increased ⩒e/⩒CO2), and limited ability to increase stroke volume [16].

In the prospective ELOPE cohort of 100 post-PE patients, 47% had exercise limitation measured by peak VO2 < 80% at 1 year. Additionally, these patients had worse 6MWT and QOL metrics compared to those with a predicted VO2 > 80% [27].

In a subgroup of the large prospective cohort FOCUS, patients with acute symptomatic PE, 396 patients underwent CPET at 3 months and 268 patients at 12 months post acute PE. Fifty percent had at least one abnormal parameter indicating cardiopulmonary limitation. Of patients undergoing CPET at both time points, 16.7% had resolving cardiopulmonary limitation and 24.8% developed a new limitation. Of those experiencing post-PE impairment, 79.1% and 78.6% had cardiopulmonary limitation at three and six months, respectively. Definitions of CPET abnormalities in PPES can be found in Table 2 [40].

Table 2.

CPET abnormalities in post-PE syndrome.

3.3. Cardiac Function Evaluation: Echocardiography

Multiple studies have demonstrated structural heart changes, specifically RV dysfunction, following acute PE in previously healthy patients. In 109 previously healthy patients, 27 patients (25%) had abnormal RV function six months after acute PE [8]. Additionally, a large cohort of 845 patients showed residual RV dysfunction in 27% of symptomatic PE survivors six months following acute PE [41].

Severity of PE at diagnosis may also affect RV function at follow-up. In a cohort of 20 patients undergoing CPET after an intermediate- or high-risk PE, 65% continued to show RV dilation or dysfunction one month after acute PE, persisting six months later [38]. The REACH study performed in 2020 demonstrated that in 508 patients, intermediate-risk PE was associated with higher likelihood of persistent RV dysfunction (44%) three months post-PE compared to a standard-risk group (18%) despite a low rate of CTEPH (0.6%) in this cohort [40]. Furthermore, in a prospective cohort of 144 PE survivors, 27% of patients had higher RV systolic pressure (RSVP) six months following the PE diagnosis [18].

Echocardiograms are pivotal for identifying or excluding alternate causes of symptoms. In a study of 555 patients treated for acute PE six months prior, 42 (7.5%) had reduced EF (<50%), 50 (9%) presented with valvular heart disease, and 265 (48%) showed LV diastolic dysfunction [41,42].

Findings of persistent RV dysfunction in the months to years following acute PE are independently associated with symptoms of dyspnea [20] and correlate with worse functional status [43]. A post hoc analysis of the PEITHO trial in 2019 showed that 10% of survivors of intermediate-risk PE experienced echocardiographic evidence of PH and NYHA II-IV symptoms [43].

4. Residual Thrombosis Evaluation: CT Pulmonary Angiography and Ventilation/Perfusion Scan

4.1. CT Pulmonary Angiography (CTA)

Incomplete clot resolution of acute PE may be seen on serial pulmonary imaging following acute PE. Residual clot burden following acute PE has also been studied using serial CTA following 6 months of uninterrupted anticoagulation. In a prospective cohort of 157 patients, complete PE resolution was seen in 84% of the patients. Ten percent of patients experienced recurrent VTE, but interestingly, the presence of residual pulmonary vascular obstruction (RPVO) was not associated with recurrent VTE. Prior VTE showed an increased risk of incomplete resolution [6].

4.2. Ventilation/Perfusion Scan (VQ Scan)

In one study, 647 consecutive patients following the first episode of acute PE on anticoagulation were assessed for RPVO with a VQ scan after 6 months. It showed persistent perfusion defects in 50% of patients. Older age, unprovoked clinical presentation, and worse clinical severity during the acute PE episode were significantly associated with persistence of pulmonary obstruction. Additionally, in this cohort, after 3 years of follow-up, recurrent VTE and/or CTEPH developed in 10% of patients with RPVO and in 4% of patients without RPVO. Here, the presence of RPVO was an independent predictor of recurrent VTE and/or CTEPH [44].

Another prospective observational study of consecutive acute PE patients that had received anticoagulation for at least 3 months showed perfusion defects on a VQ scan in 29% of patients after a median follow-up of 12 months. In the study, 30% of patients were receiving anticoagulation at one year following acute PE. Independent risk factors for RPVO defects included older age, longer time between symptom onset and PE diagnosis, higher levels of initial vascular obstruction, and previous VTE [45].

Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) VQ has a similar sensitivity to planar VQ scan; however, it has a higher specificity in the diagnosis of PE [46]. Therefore, it is a preferable modality by comparison as it is associated with fewer non-diagnostic studies [47]. VQ scans have been shown to be more sensitive than CTA in detecting chronic thromboembolic disease [48,49].

4.3. Summary of Diagnosis

Perfusion defects lead to increased alveolar dead space and VQ mismatching. The combination of these abnormalities in conjunction with persistent RV dysfunction results in CTEPD and/or CTEPH.

Table 3 provides a summary of findings of diagnostic tests in PPES phenotypes. As shown, symptoms in the months to years following acute PE diagnosis are common [50]. There is no single test to diagnose the presence of PPES phenotypes. One could argue for obtaining tests to evaluate exercise capacity, cardiac function, and residual thrombosis in all patients, given the shown increased risk of CTEPH, and its increased mortality. Other clinicians may order selective testing based on symptom severity, clot burden, and RV dysfunction on initial diagnosis. There have been several algorithms proposed for testing following acute PE diagnosis [5,21].

Table 3.

Findings of diagnostic tests in post-PE syndrome phenotypes.

Three notable strategies for post-PE follow-up and PPES screening are (1) the SEARCH algorithm [51], (2) the FOCUS trial [13], and (3) the ESC/ERS algorithm for early CTEPH diagnosis [52].

The SEARCH algorithm (symptom screen, exercise function (CPET), arterial perfusion (VQ scan), resting heart function (echocardiogram), confirmatory imaging (CTA), and hemodynamics) is a stepwise algorithm that sorts patients by a hierarchical series of dichotomous tests into discreet categories of PPES [51]. A study for the validation of the SEARCH algorithm is ongoing [53].

An advantage of the SEARCH algorithm is that it is simple to use, organized in a stepwise fashion, and therefore may avoid unnecessary testing. On the other hand, a challenge may be the widespread availability of CPET testing and interpretation. Additionally, some clinicians may be hesitant to order CPET testing prior to cardiac or imaging evaluation.

Strategies for detection of PPES are discussed in the FOCUS trial. Here, authors did not establish a stepwise algorithm for post-PE follow-up, instead utilizing a composite of testing to better define post-PE impairment. At regular intervals (3, 12, and 24 months) following acute PE diagnosis, the authors suggest performing symptom, functional, laboratory, and echocardiographic testing [13]. Post-PE impairment was defined by deterioration (compared to findings at discharge, or to the previous follow-up visit) in at least one category, persistence of the abnormal finding on an echocardiogram (RV basal diameter, right atrium (RA) end-systolic area, tricuspid annulus plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), LV eccentricity index, estimated RA pressure, systolic tricuspid regurgitation (TR) jet velocity, or pericardial effusion), and/or clinical (progression of existing symptoms, clinical evidence of RV failure, syncope), functional (WHO functional class, 6MWT, CPET), or laboratory parameters (BNP, NT-proBNP) of RV failure. The median follow-up was 2 years. While the estimated cumulative incidence of CTEPH was low (2.3%), the incidence of post-PE impairment was 16% (95% CI 12.8–20.8%). Additionally, post-PE impairment helped identify 15 of the 16 patients diagnosed with CTEPH [13].

A subgroup of patients from the FOCUS cohort (396 of 1017) underwent CPET at 3 and 12 months. The prevalence of cardiopulmonary limitation (defined as ventilatory inefficiency or insufficient cardiocirculatory reserve) was 50% and 44% at 3 and 12 months, respectively, and that of deconditioning (defined as a peak O2 uptake <80%) was 12% and 15% at 3 and 12 months, respectively. The authors concluded that CPET can be considered for selected patients with persisting symptoms after PE [40].

The advantage of using the FOCUS trial for PPES screening is that it engages routine symptoms and testing that are already utilized for most post-PE follow-up. The benefit of the prespecified, standardized follow-up schedule and defined composite criteria to screen for PPES is a higher yield and earlier identification of patients than traditional follow-up methods, leading to flagging of patients at higher risk of rehospitalization, mortality, and worse quality of life, enabling risk stratification for follow-up intensity or interventions.

Here, follow-up testing emphasizes subjective and objective parameters of functional status, rather than the presence of residual thrombosis on imaging. Notably, VQ scans and CTA were not recommended. Additionally, this strategy encourages a longer follow-up period of 2 years, with repeated reassessments.

ESC/ERS guidelines recommend an algorithm for the diagnosis of CTEPH, although not specifically for PPES. Step one of this algorithm includes assessment of symptoms, a physical exam, BNP/NT-proBNP, and resting ECG testing. Step two recommends obtaining echocardiograms and VQ scans as the initial diagnostic tests [50]. A negative VQ scan has a high negative predictive value and can safely exclude CTEPH [49]. Echocardiographic probability of PH is based on tricuspid valve regurgitation (TVR). Patients with low probability of PH without risk factors should be investigated for an alternative etiology for dyspnea. Patients with risk factors and/or intermediate probability for PH should have repeated echocardiography follow-up, and patients with risk factors for PH and high probability of PH should undergo further intervention/RHC if indicated. According to the ESC/ERS algorithm, CPET testing should be performed in cases where echocardiographic testing is without abnormalities [52]. The advantage of the ESC/ERS algorithm strategy is that it recommends both imaging (with VQ scan) and RV function assessment (with echocardiogram) simultaneously. A challenge may be the widespread availability of VQ scans across centers.

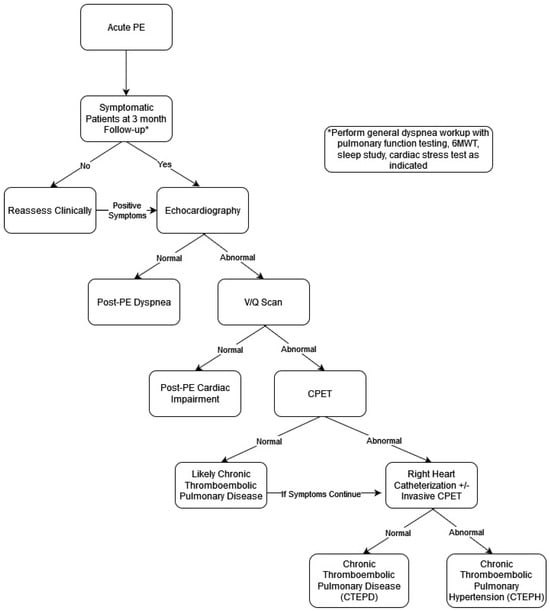

Our proposed schema (Figure 1) for diagnosis of PPES incorporates elements from the mentioned diagnostic models. Patients diagnosed with acute PE should have a follow-up months post diagnosis. Initial screening for PPES should be focused on symptom assessment (with or without a validated questionnaire). Patients without symptoms should be counseled on seeking further care if they are to become symptomatic, especially those with abnormal RV or a large clot burden in the acute phase. Patients who are symptomatic should undergo echocardiography given its widespread availability and clinician comfort with ordering and interpretation. Additionally, at this time, symptomatic patients should also undergo generalized dyspnea workup with pulmonary function testing, a 6MWT, a sleep study, and/or a cardiac stress test, as indicated by their history and physical exam. Patients with normal echocardiography fit into the “Post-PE Dyspnea” phenotype. Patients with abnormal echocardiography should proceed with a VQ scan. Patients with a normal VQ test fit into the “Post-PE Cardiac Impairment” phenotype. Patients with an abnormal VQ scan should then undergo CPET if available. Patients with abnormal CPET should undergo RHC (resting or exercise/invasive, depending on availability and patients’ pre-test probability of having PH). Patients with normal resting RHC fit into the “CTEPD” phenotype. Patients with normal CPET may still fit into the CTEPD phenotype, but strong consideration should be given to exercise/invasive RHC, especially if symptoms continue. Patients with abnormal RHC fit into the “CTEPH” phenotype (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schema for diagnosis of PPES Phenotypes.

5. Management of Post-PE Syndrome

There is no clear treatment paradigm for other phenotypes of post-PE syndrome. Treatment focuses largely on optimizing aspects of the ongoing functional impairment. Pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to improve functional status in non-PE cohorts including following acute exacerbation of COPD and acute myocardial infarction. The utility of high-intensity interval training in an intermediate–high-risk post-PE population was investigated in a 24-patient randomized clinical trial. The group that received 8 weeks of high-intensity interval training recorded significant improvements in estimated maximal oxygen uptake, forced expiratory volume (FEV1), RV/LV ratio diameter, and health-related quality of life using the SF-36 survey [54]. Similarly, a 3-month exercise and weight loss program demonstrated a significant improvement in peak exercise capacity in the intervention group compared to the control group in patients with recent acute VTE. Symptomatic patients following acute PE diagnosis may also benefit from home-based physical therapy. One hundred and forty patients who received home-based physiotherapist-guided therapy showed improvements in the shuttle walk test and quality of life surveys as measured by Pemb-QoL and the EuroQol-5 questionnaire [55].

Patients with persistent psychological symptoms following PE may benefit from psychotherapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to reduce intrusive thoughts, improve coping mechanisms, and restore a sense of safety. Supportive psychotherapy and structured patient education regarding recurrence risk, anticoagulation therapy, and prognosis can further reduce anxiety and improve self-efficacy. Integration of mental health specialists within multidisciplinary pulmonary embolism response teams (PERTs) and dedicated post-PE clinics may optimize patient outcomes. Future research should prioritize elucidating mechanisms, refining screening tools, and evaluating targeted interventions to mitigate long-term psychological morbidity in this vulnerable population.

Post-PE patients have a higher risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) compared to age-matched cohorts [56]. Thus, screening for CAD, especially in symptomatic post-PE patients, should be considered. Successful management via revascularization is likely to improve symptoms and functional status. Proper medical management of existing heart failure regimens and arrhythmias may have been altered during acute inpatient admissions for PE and should be reevaluated as indicated [57].

Despite being the preferred treatment for CTEPH, pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE) has been studied less in the CTEPD population. In 42 patients with image-proven CTEPD with mPAP < 25 mmHg that underwent PTE, there was symptomatic improvement in 95% of patients in NYHA I or II groups at 6 months post procedure. Additionally, there was improvement in the median CAMPHOR score with respect to symptoms, activity, and QOL measurements [58]. These clinical improvements were comparable to CTEPH patients undergoing PTE as seen in the PEACOG trial [59]. PTE was noted to be safe in this group, with a 95% 1-year survival rate; however, risks and benefits should be weighed given the estimated 5-year survival of patients with CTEPD of 95% [58,60].

Balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA) has been an increased treatment option for patients with inoperable CTEPH. The use of BPA in CTEPD patients has been studied in a small cohort of 10 patients with image-proven CTEPD and mPAP < 25 mmHg. In this cohort, the 6MWT improved by an average of 31m (8.5% improvement from baseline) and patients experienced a decrease in PVR. RV function measured by cardiac MRI was unchanged [61]. Similarly, in another small cohort of 15 CTEPD patients, BPA significantly improved hemodynamics and the 6MWT and lowered the prescribed home oxygen therapy [62]. Further studies are needed to assess the utility of BPA in inoperable CTEPD. Currently, there are no published studies on the use of pulmonary vasodilators in PPES.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

At the heart of managing PPES lies the critical task of identifying its defining characteristics: residual clot burden, right ventricular dysfunction, and exercise intolerance. Tackling these aspects necessitates comprehensive, large-scale, long-term cohort studies aimed at uncovering the risk factors for its emergence following the acute phase. Such research is crucial, especially in evaluating how initial acute PE treatments might affect the development of the syndrome. The ongoing clinical trials investigating innovative treatment devices for intermediate- and high-risk acute PE hold promise in this area, particularly the ones with long-term follow-up. Additionally, the availability of diagnostic algorithms provides essential support for clinicians in identifying PPES phenotypes, with an upcoming large-scale observational study expected to validate the SEARCH algorithm, representing a significant leap forward. A push toward standardizing the definitions of PPES will foster a more uniform approach, enhancing patient guidance on symptom management and follow-up.

To conclude, the literature clearly indicates that post-PE impairment is common across a spectrum of manifestations, emphasizing the critical need for physician awareness at all levels. The complex nature of post-PE conditions, coupled with a still-developing understanding of their phenotypes, necessitates an immediate call for expert consensus. This collaborative effort is vital for navigating the current medical landscape and guiding clinical practice effectively, ultimately aiming to confront the challenges of post-PE syndrome and enhance patient care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.H.L. and P.R.; methodology, B.H.L., S.D., B.N.R.-L. and P.R.; software, S.D.; validation, B.N.R.-L. and P.R.; formal analysis, B.H.L. and S.D.; investigation, B.H.L. and S.D.; resources, B.N.R.-L. and P.R., data curation, S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, B.H.L., S.D. and B.H.; writing—review and editing, B.N.R.-L. and P.R.; visualization, B.N.R.-L. and P.R. supervision, B.N.R.-L. and P.R.; project administration, P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| 6MWD | Six-Minute Walk Distance |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BPA | Balloon Pulmonary Angioplasty |

| CTA | Computed Tomography Angiography |

| CTEPD | Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Disease |

| CTEPH | Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension |

| CO | Cardiac Output |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| FEV1 | Forced Expiratory Volume in One Second |

| LV | Left Ventricle |

| mMRC | Modified Medical Research Council |

| mPAP | Mean Pulmonary Artery Pressure |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| PCWP | Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure |

| PE | Pulmonary Embolism |

| PEA | Pulmonary Endarterectomy |

| PEmb-QoL | Pulmonary Embolism Quality of Life |

| PH | Pulmonary Hypertension |

| PPES | Post-Pulmonary Embolism Syndrome |

| PVR | Pulmonary Vascular Resistance |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| RA | Right Atrium |

| RHC | Right Heart Catheterization |

| RV | Right Ventricle |

| RVPO | Residual Pulmonary Vascular Obstruction |

| SF-36 | Short Form 36 |

| SPECT | Single-Positron Emission Computed Tomography |

| TTE | Transthoracic Echocardiogram |

| TRV | Tricuspid Regurgitation Velocity |

| V/Q | Ventilation/Perfusion Scan |

| VD/VT | Dead-Space Fraction |

| VE/VCO2 | Ventilation as a Function of Exhaled CO2 |

| VO2 | Rate of Oxygen Use |

References

- CDC Data and Statistics on Venous Thromboembolism|CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published 16 February 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/blood-clots/data-research/facts-stats/index.html (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Lehnert, P.; Lange, T.; Møller, C.H.; Olsen, P.S.; Carlsen, J. Acute Pulmonary Embolism in a National Danish Cohort: Increasing Incidence and Decreasing Mortality. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 118, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.G.; Tagalakis, V.; Wu, C.; Lazo-Langner, A. Current estimates of the incidence of acute venous thromboembolic disease in Canada: A meta-analysis. Thromb. Res. 2021, 197, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essien, E.O.; Rali, P.; Mathai, S. Pulmonary Embolism. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 103, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinides, S.V.; Meyer, G.; Becattini, C.; Bueno, H.; Geersing, G.-J.; Harjola, V.-P.; Huisman, M.V.; Humbert, M.; Jennings, C.S.; Jiménez, D.; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 54, 1901647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroft, L.J.M.; Erkens, P.M.G.; Douma, R.A.; Mos, I.C.M.; Jonkers, G.; Hovens, M.M.C.; Durian, M.F.; Cate, H.T.; Beenen, L.F.M.; Kamphuisen, P.W.; et al. Thromboembolic resolution assessed by CT pulmonary angiography after treatment for acute pulmonary embolism. Thromb. Haemost. 2015, 114, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klok, F.A.; van der Hulle, T.; den Exter, P.L.; Lankeit, M.; Huisman, M.V.; Konstantinides, S. The post-PE syndrome: A new concept for chronic complications of pulmonary embolism. Blood Rev. 2014, 28, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevinson, B.G.; Hernandez-Nino, J.; Rose, G.; Kline, J.A. Echocardiographic and functional cardiopulmonary problems 6 months after first-time pulmonary embolism in previously healthy patients. Eur. Heart J. 2007, 28, 2517–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, S.C.; Kawut, S.M. The Post–Pulmonary Embolism Syndrome: Real or Ruse? Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019, 16, 811–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnefoy, P.B.; Margelidon-Cozzolino, V.; Catella-Chatron, J.; Ayoub, E.; Guichard, J.; Murgier, M.; Bertoletti, L. What’s next after the clot? Residual pulmonary vascular obstruction after pulmonary embolism: From imaging finding to clinical consequences. Thromb. Res. 2019, 184, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picart, G.; Robin, P.; Tromeur, C.; Orione, C.; Raj, L.; Ferrière, N.; Le Mao, R.; Le Roux, P.-Y.; Le Floch, P.-Y.; Lemarié, C.A.; et al. Predictors of residual pulmonary vascular obstruction after pulmonary embolism: Results from a prospective cohort study. Thromb. Res. 2020, 194, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sista, A.K.; Miller, L.E.; Kahn, S.R.; Kline, J.A. Persistent right ventricular dysfunction, functional capacity limitation, exercise intolerance, and quality of life impairment following pulmonary embolism: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Vasc. Med. 2017, 22, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valerio, L.; Mavromanoli, A.C.; Barco, S.; Abele, C.; Becker, D.; Bruch, L.; Ewert, R.; Faehling, M.; Fistera, D.; Gerhardt, F.; et al. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension and impairment after pulmonary embolism: The FOCUS study. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3387–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sista, A.K.; Klok, F.A. Late outcomes of pulmonary embolism: The post-PE syndrome. Thromb. Res. 2018, 164, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gal, G.; Carrier, M.; Castellucci, L.A.; Cuker, A.; Hansen, J.; Klok, F.A.; Langlois, N.J.; Levy, J.H.; Middeldorp, S.; Righini, M.; et al. Development and implementation of common data elements for venous thromboembolism research: On behalf of SSC Subcommittee on official Communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 19, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, M.; Kolb, P.; Grün, M.; Jany, B.; Hübner, G.; Grgic, A.; Holl, R.; Schaefers, H.-J.; Wilkens, H. Functional Characterization of Patients with Chronic Thromboembolic Disease. Respiration 2016, 91, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ende-Verhaar, Y.M.; Cannegieter, S.C.; Noordegraaf, A.V.; Delcroix, M.; Pruszczyk, P.; Mairuhu, A.T.; Huisman, M.V.; Klok, F.A. Incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after acute pulmonary embolism: A contemporary view of the published literature. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1601792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, J.A.; Steuerwald, M.T.; Marchick, M.R.; Hernandez-Nino, J.; Rose, G.A. Prospective Evaluation of Right Ventricular Function and Functional Status 6 Months After Acute Submassive Pulmonary Embolism: Frequency of Persistent or Subsequent Elevation in Estimated Pulmonary Artery Pressure. Chest 2009, 136, 1202–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.; Lindmarker, P.; Johnsson, H.; Juhlin-Dannfelt, A.; Jorfeldt, L. Pulmonary Embolism. Circulation 1999, 99, 1325–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golpe, R.; Testa-Fernández, A.; Pérez-De-Llano, L.A.; Castro-Añón, O.; González-Juanatey, C.; Pérez-Fernández, R.; Fariñas, M.C. Long-term clinical outcome of patients with persistent right ventricle dysfunction or pulmonary hypertension after acute pulmonary embolism. Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 2011, 12, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Lebron, B.; McDaniel, M.; Ahrar, K.; Alrifai, A.; Dudzinski, D.M.; Fanola, C.; Blais, D.; Janicke, D.; Melamed, R.; Mohrien, K.; et al. Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow Up of Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Consensus Practice from the PERT Consortium. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2019, 25, 1076029619853037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, D.A.; Wells, C.K. Evaluation of Clinical Methods for Rating Dyspnea. Chest 1988, 93, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Es, J.; Exter, P.L.D.; Kaptein, A.A.; Andela, C.D.; Erkens, P.M.; Klok, F.A.; Douma, R.A.; Mos, I.C.; Cohn, D.M.; Kamphuisen, P.W.; et al. Quality of life after pulmonary embolism as assessed with SF-36 and PEmb-QoL. Thromb. Res. 2013, 132, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, D.M.; Nelis, E.A.; Busweiler, L.A.; Kaptein, A.A.; Middeldorp, S. Quality of life after pulmonary embolism: The development of the PEmb-QoL questionnaire. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2009, 7, 1044–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klok, F.A.; Cohn, D.M.; Middeldorp, S.; Scharloo, M.; Büller, H.R.; van Kralingen, K.W.; Kaptein, A.A.; Huisman, M.V. Quality of life after pulmonary embolism: Validation of the PEmb-QoL Questionnaire. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 8, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boon, G.J.A.M.; Barco, S.; Bertoletti, L.; Ghanima, W.; Huisman, M.; Kahn, S.; Noble, S.; Prandoni, P.; Rosovsky, R.; Sista, A.; et al. Measuring functional limitations after venous thromboembolism: Optimization of the Post-VTE Functional Status (PVFS) Scale. Thromb. Res. 2020, 190, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.P.; Li, X.M.; Chen, H.W.; Cui, J.Y.; Niu, L.L.; He, Y.B.; Tian, X.L. Depression, anxiety and influencing factors in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Chin. Med. J. 2011, 124, 2438–2442. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, S.R.; Hirsch, A.M.; Akaberi, A.; Hernandez, P.; Anderson, D.R.; Wells, P.S.; Rodger, M.A.; Solymoss, S.; Kovacs, M.J.; Rudski, L.; et al. Functional and Exercise Limitations After a First Episode of Pulmonary Embolism: Results of the ELOPE Prospective Cohort Study. Chest 2017, 151, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, K.; Kimpton, M.; Carrier, M.; Coyle, D.; Forgie, M.; Wells, P. Estimating quality of life in acute venous thrombosis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, B.; George, R.; Vedder, R. A clinical method for physicians in palliative care: The four points of agreement vital to a consultation; context, issues, story, plan. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2014, 4, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, R.; Lewis, S.; Noble, S.; Rance, J.; Bennett, P.D. “Post-thrombotic panic syndrome”: A thematic analysis of the experience of venous thromboembolism. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klok, F.A.; van Kralingen, K.W.; van Dijk, A.P.J.; Heyning, F.H.; Vliegen, H.W.; Huisman, M.V. Prevalence and potential determinants of exertional dyspnea after acute pulmonary embolism. Respir. Med. 2010, 104, 1744–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luijten, D.; de Jong, C.M.M.; Ninaber, M.K.; Spruit, M.A.; Huisman, M.V.; Klok, F.A. Post-Pulmonary Embolism Syndrome and Functional Outcomes after Acute Pulmonary Embolism. Semin. Thromb Hemost. 2023, 49, 848–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, S.; Meisinger, C.; Linseisen, J.; Berghaus, T.M.; Kirchberger, I. Depression and anxiety up to two years after acute pulmonary embolism: Prevalence and predictors. Thromb. Res. 2023, 222, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etchegary, H.; Wilson, B.; Brehaut, J.; Lott, A.; Langlois, N.; Wells, P.S. Psychosocial aspects of venous thromboembolic disease: An exploratory study. Thromb. Res. 2008, 122, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutchia, J.; McClelland, R.L.; Al-Naamani, N.; Appleby, D.H.; Blank, K.; Grinnan, D.; Holmes, J.H.; Mathai, S.C.; Minhas, J.; Ventetuolo, C.E.; et al. Minimal Clinically Important Difference in the 6-min-walk Distance for Patients with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 207, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavoly, M.; Wik, H.S.; Sirnes, P.A.; Jelsness-Jørgensen, L.-P.; Ghanima, J.P.; Klok, F.A.; Sandset, P.-M.; Ghanima, W. The impact of post-pulmonary embolism syndrome and its possible determinants. Thromb. Res. 2018, 171, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaghdadi, M.S.; Dudzinski, D.M.; Giordano, N.; Kabrhel, C.; Ghoshhajra, B.; Jaff, M.R.; Weinberg, I.; Baggish, A. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Patients Following Massive and Submassive Pulmonary Embolism. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e006841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.; Noble, S.; Lewis, S.; Bennett, P. Long-term psychosocial impact of venous thromboembolism: A qualitative study in the community. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmakis, I.T.; Valerio, L.; Barco, S.; Alsheimer, E.; Ewert, R.; Giannakoulas, G.; Hobohm, L.; Keller, K.; Mavromanoli, A.C.; Rosenkranz, S.; et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing during follow-up after acute pulmonary embolism. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2300059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzikowska-Diduch, O.; Kostrubiec, M.; Kurnicka, K.; Lichodziejewska, B.; Pacho, S.; Miroszewska, A.; Bródka, K.; Skowrońska, M.; Łabyk, A.; Roik, M.; et al. The post-pulmonary syndrome-results of echocardiographic driven follow up after acute pulmonary embolism. Thromb. Res. 2020, 186, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, H.; Fang, W.; Clements, W.; Bloom, J.; McFadyen, J.; Tran, H. Risk Stratification of Acute Pulmonary Embolism and Determining the Effect on Chronic Cardiopulmonary Complications: The REACH Study. TH Open 2020, 4, e45–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barco, S.; Russo, M.; Vicaut, E.; Becattini, C.; Bertoletti, L.; Beyer-Westendorf, J.; Bouvaist, H.; Couturaud, F.; Danays, T.; Dellas, C.; et al. Incomplete echocardiographic recovery at 6 months predicts long-term sequelae after intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. A post-hoc analysis of the Pulmonary Embolism Thrombolysis (PEITHO) trial. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2019, 108, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesavento, R.; Filippi, L.; Palla, A.; Visonà, A.; Bova, C.; Marzolo, M.; Porro, F.; Villalta, S.; Ciammaichella, M.; Bucherini, E.; et al. Impact of residual pulmonary obstruction on the long-term outcome of patients with pulmonary embolism. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1601980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, O.; Helley, D.; Couchon, S.; Roux, A.; Delaval, A.; Trinquart, L.; Collignon, M.; Fischer, A.; Meyer, G. Perfusion defects after pulmonary embolism: Risk factors and clinical significance. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 8, 1248–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collart, J.P.; Roelants, V.; Vanpee, D.; Lacrosse, M.; Trigaux, J.-P.; Delaunois, L.; Gillet, J.-B.; DE Coster, P.; Borght, T.V. Is a lung perfusion scan obtained by using single photon emission computed tomography able to improve the radionuclide diagnosis of pulmonary embolism? Nucl. Med. Commun. 2002, 23, 1107–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemb, M.; Pohlabeln, H. Pulmonary thromboembolism: A retrospective study on the examination of 991 patients by ventilation/perfusion SPECT using Technegas. Nuklearmedizin 2001, 40, 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Cosmi, B.; Nijkeuter, M.; Valentino, M.; Huisman, M.V.; Barozzi, L.; Palareti, G. Residual emboli on lung perfusion scan or multidetector computed tomography after a first episode of acute pulmonary embolism. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2011, 6, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunariu, N.; Gibbs, S.J.R.; Win, Z.; Gin-Sing, W.; Graham, A.; Gishen, P.; Al-Nahhas, A. Ventilation–Perfusion Scintigraphy Is More Sensitive than Multidetector CTPA in Detecting Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Disease as a Treatable Cause of Pulmonary Hypertension. J. Nucl. Med. 2007, 48, 680–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klok, F.A.; Tijmensen, J.E.; Haeck, M.L.A.; van Kralingen, K.W.; Huisman, M.V. Persistent dyspnea complaints at long-term follow-up after an episode of acute pulmonary embolism: Results of a questionnaire. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2008, 19, 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.A.; Fernandes, T.M.; Channick, R.N. Evaluation of Dyspnea and Exercise Intolerance After Acute Pulmonary Embolism. Chest 2023, 163, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.F.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.S.; Escribano-Subias, P.; Ferrari, P.; et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: Developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Endorsed by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) and the European Reference Network on rare respiratory diseases (ERN-LUNG). Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3618–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.A.; Fernandes, T.M.; Chung, J.; E Vintch, J.R.; McGuire, W.C.; Thapamagar, S.; Alotaibi, M.; Aries, S.; Dakaeva, K. Observational cohort study to validate SEARCH, a novel hierarchical algorithm to define long-term outcomes after pulmonary embolism. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e074470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghram, A.; Jenab, Y.; Soori, R.; Choobineh, S.; Hosseinsabet, A.; Niyazi, S.; Shirani, S.; Shafiee, A.; Jalali, A.; Lavie, C.J.; et al. High-Intensity Interval Training in Patients with Pulmonary Embolism: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2021, 53, 2037–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolving, N.; Brocki, B.C.; Bloch-Nielsen, J.R.; Larsen, T.B.; Jensen, F.L.; Mikkelsen, H.R.; Ravn, P.; Frost, L. Effect of a Physiotherapist-Guided Home-Based Exercise Intervention on Physical Capacity and Patient-Reported Outcomes Among Patients With Acute Pulmonary Embolism: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e200064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prandoni, P.; Ghirarduzzi, A.; Prins, M.H.; Pengo, V.; Davidson, B.L.; Sørensen, H.; Pesavento, R.; Iotti, M.; Casiglia, E.; Iliceto, S.; et al. Venous thromboembolism and the risk of subsequent symptomatic atherosclerosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006, 4, 1891–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klok, F.A.; Ageno, W.; Ay, C.; Bäck, M.; Barco, S.; Bertoletti, L.; Becattini, C.; Carlsen, J.; Delcroix, M.; van Es, N.; et al. Optimal follow-up after acute pulmonary embolism: A position paper of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Pulmonary Circulation and Right Ventricular Function, in collaboration with the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Atherosclerosis and Vascular Biology, endorsed by the European Respiratory Society. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada, D.; Pepke-Zaba, J.; Jenkins, D.P.; Berman, M.; Treacy, C.M.; Cannon, J.E.; Toshner, M.; Dunning, J.J.; Ng, C.; Tsui, S.S.; et al. Outcome of pulmonary endarterectomy in symptomatic chronic thromboembolic disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44, 1635–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuylsteke, A.; Sharples, L.; Charman, G.; Kneeshaw, J.; Tsui, S.; Dunning, J.; Wheaton, E.; Klein, A.; Arrowsmith, J.; Hall, R.; et al. Circulatory arrest versus cerebral perfusion during pulmonary endarterectomy surgery (PEACOG): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011, 378, 1379–1387, Erratum in Lancet 2011, 378, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedel, M.; Stanek, V.; Widimsky, J.; Prerovsky, I. Longterm Follow-up of Patients with Pulmonary Thromboembolism: Late Prognosis and Evolution of Hemodynamic and Respiratory Data. Chest 1982, 81, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenroth, C.B.; Olsson, K.M.; Guth, S.; Breithecker, A.; Haas, M.; Kamp, J.; Fuge, J.; Hinrichs, J.B.; Roller, F.; Hamm, C.W.; et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for inoperable patients with chronic thromboembolic disease. Pulm. Circ. 2018, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inami, T.; Kataoka, M.; Kikuchi, H.; Goda, A.; Satoh, T. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for symptomatic chronic thromboembolic disease without pulmonary hypertension at rest. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 289, 116–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.