Abstract

Background/Objectives: Long-term outcomes of patients with left main coronary artery (LMCA) disease and diabetes mellitus (DM) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are incompletely investigated. The aim of this study was to assess the 10-year clinical outcomes after PCI according to diabetic status and antidiabetic therapy in patients with LMCA. Methods: This study represents a pooled analysis of two randomized trials (n = 1257 patients) on LMCA PCI focused on the prespecified subgroups of diabetic patients. Patients were categorized in groups according to the diabetic status and antidiabetic therapy (oral drugs or insulin therapy). The primary endpoint was 10-year all-cause mortality. Results: Overall, 361 patients had DM (246 patients on oral antidiabetic drugs and 115 patients on insulin therapy) and 896 patients had no DM. At 10 years, 477 patients died: 291 nondiabetic patients (35.7%), 111 diabetic patients (49.5%) on oral antidiabetic drugs and 75 diabetic patients (70.0%) on insulin therapy (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.57, 95% confidence interval [1.26–1.96]; p < 0.001 for diabetic patients on oral antidiabetic drugs vs. nondiabetic patients; HR = 2.80 [2.17–3.61]; p < 0.001 for diabetic patients on insulin therapy vs. nondiabetic patients; HR = 1.78 [1.33–2.39]; p <0.001 for diabetic patients on insulin therapy vs. diabetic patients on oral antidiabetic drugs). The 10-year incidence of myocardial infarction was higher in diabetic patients on insulin therapy (10.0%) versus diabetic patients on oral antidiabetic drugs (3.0%). There were no significant differences between the groups regarding the 10-year incidence of definite stent thrombosis, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, repeat PCI or stroke. Conclusions: In patients with LMCA disease undergoing PCI, DM was associated with a higher 10-year incidence of all-cause mortality than patients without DM with the worst outcomes observed in diabetic patients on insulin therapy.

1. Introduction

Critical atherosclerotic lesions in the left main coronary artery (LMCA) are found in 3–5% of patients undergoing coronary angiography and 10–30% of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) [1]. Diabetes mellitus (DM) is an established cardiovascular risk factor that is associated with more severe and diffuse coronary artery disease (CAD), increased platelet reactivity and propensity to vascular thrombosis, higher systemic inflammation, reduced survival and poorer outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or CABG [2,3,4,5,6]. Approximately 25% of patients with LMCA disease have DM, which confers a higher long-term (5-year) risk of death, spontaneous myocardial infarction, stroke and repeat revascularization compared with patients without DM [5]. Historically, CABG has been considered as a preferred revascularization strategy (as compared to PCI) in patients with LMCA disease. Recent advances in the field of coronary interventions have led to a 4-fold rise in PCI procedures for LMCA disease and more favorable subsequent outcomes [7]. A recent meta-analysis of randomized trials that compared PCI with CABG in patients with LMCA disease gave mixed results with no difference between CABG and PCI with respect to 5-year death and stroke and a higher risk of myocardial infarction and revascularization with PCI, albeit without diabetes-by-revascularization strategy interaction [8]. However, studies that have investigated the efficacy of PCI versus CABG in patients with LMCA disease and DM have offered controversial results [9,10]. Since, patients with DM represent a heterogeneous group and the risk conferred by LMCA disease and DM may be additive in case both conditions co-exist, a careful decision-making and a personalized approach in selecting the most appropriate revascularization strategy in these patients are required [11,12]. We undertook this study to assess the 10-year clinical outcomes after PCI in patients with LMCA and DM and to investigate whether clinical outcomes differ according to the type of antidiabetic therapy.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

This study represents a pooled analysis of 2 randomized trials on LMCA PCI focused on the prespecified subgroups of diabetic patients: the Drug-Eluting-Stents for Unprotected Left Main Stem Disease (ISAR-LEFT-MAIN) trial (NCT00133237; n = 607 patients, 176 patients with DM) [13] and the Intracoronary Stenting and Angiographic Results: Drug-Eluting Stents for Unprotected Coronary Left Main Lesions (ISAR-LEFT MAIN-2) trial (NCT00598637; n = 650 patients, 185 patients with DM) [14]. Overall, 1257 patients >18 years of age with ischemic symptoms or documented myocardial ischemia in the presence of ≥50% de novo stenosis located in the LMCA were included in this analysis. Patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction within <48 h from the chest pain onset or those with previous CABG, in-stent restenosis, cardiogenic shock, acute infections, malignancies or other comorbidities with a life expectancy of less than one year, planned elective surgery requiring discontinuation of P2Y12 antithrombotic drugs in the first 6 months following enrollment (in source studies), reported allergy to the study drugs or stent constituents, pregnancy or previous enrollment in the trials were excluded. Patients obtained from the ISAR-LEFT MAIN trial received a paclitaxel-eluting stent or a sirolimus-eluting stent whereas patients obtained from the ISAR-LEFT MAIN 2 trial, received a zotarolimus-eluting stent or an everolimus-eluting stent [13,14]. Written informed consent and institutional ethics committee approval (code: 1339/05; date 28 June 2005 and code: 1975/07; date 18 December 2007) were obtained in all patients. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Study Definitions

All included patients had a ≥50% de novo stenosis located in the LMCA, which encompassed a coronary artery segment from the left main stem ostium to the end of the 5 mm proximal segments of the left anterior descending artery, left circumflex artery and ramus intermedius if the latter had a vessel size of ≥2 mm in diameter. LMCA stenosis was classified as ostial (located within 3 mm of the LMCA ostium), mid-shaft (located in the medial part of LMCA with at least 3 mm of apparently nondiseased artery before bifurcation) or distal (located in the distal part of the LMCA and bifurcation/trifurcation with the proximal left anterior descending artery, proximal left circumflex artery and proximal ramus intermedius if this vessel was present). The stenting technique was left to the discretion of the operators. Coronary angiograms were digitally recorded and analyzed off-line in the quantitative angiographic core laboratory with an automated edge-detection system (CMS version 7.1, Medis Medical Imaging Systems, Leiden, The Netherlands) by independent, experienced operators who were blinded to the treatment allocation. The SYNTAX (SYNergy between PCI with TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery) was defined according to Sianos et al. [15]. Details are provided in the primary studies [13,14]. DM was diagnosed if the patient had an established diagnosis of the disease and was under active treatment with insulin or oral hypoglycemic drugs. For patients with a de novo diagnosis of DM during the index hospitalization, DM was diagnosed according to the World Health Organization criteria: an abnormal fasting blood glucose (≥126 mg/dL or ≥7.0 mmol/L) or abnormal glucose tolerance test (≥200 mg/dL or ≥11.1 mmol/L). Measurements of glucated hemoglobin HbA1c were used to assess stress-induced hyperglycemia. Glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was measured with a turbidimetric inhibition immunoassay method in hemolyzed whole blood anticoagulated with tripotassium-EDTA. Serum creatinine was measured with a kinetic colorimetric assay based on the compensated Jaffe method. Left ventricular ejection fraction was calculated using the area-length method on left ventricular angiograms. Body mass index was calculated using the patient’s weight and height measured during the hospital stay. Other cardiovascular risk factors—arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and smoking were defined as per guideline-recommended criteria at the time of enrollment of patients in the source studies.

Drug therapy at hospital discharge included clopidogrel 75 mg/day or prasugrel 10 mg/day for at least 12 months and aspirin at a dose of 80 to 200 mg daily given indefinitely. Other medications were prescribed at the discretion of the treating physician.

2.3. Study Endpoints and Follow-Up

The primary endpoint of the study was all-cause mortality at 10 years. Cardiac mortality, myocardial infarction, definite stent thrombosis, target lesion revascularization, nontarget lesion revascularization and stroke at 10 years were also analyzed. Cardiac death and definite stent thrombosis were defined according to the Academic Research Consortium criteria [16]. The diagnosis of myocardial infarction was established in the presence of new Q waves on the electrocardiogram and/or documentation of elevated creatine kinase-MB isoform (or creatine kinase) to at least two times the upper limit of reference range in at least two blood samples. Target lesion revascularization was defined as any repeat PCI involving the left main area or CABG surgery in at least one of the main left coronary vessels due to luminal renarrowing in association with symptoms or objective signs of ischemia. Nontarget lesion revascularization was defined as any repeat PCI not involving the LMCA region or CABG of the nontarget vessel due to pre-existing disease, disease progression or other reasons not related to the target lesion. Stroke was defined as an acute neurological event lasting 24 h or longer with focal signs and symptoms and without evidence supporting an alternative explanation. The diagnosis of stroke was confirmed by brain imaging tests or pathological examination.

The follow-up included phone interviews at one month, six months and one year and yearly thereafter up to 10 years. Information on deaths was obtained from the hospital records, death certificates and phone contact with the patient’s relatives or referring physician, the insurance companies and registration-of-address office. The follow-up data were collected and adjudicated by personnel unaware of the clinical data of the patients.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are presented as median with 25–75th percentiles or mean ± standard deviation and compared with the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test or ANOVA, when appropriate. The normality of distribution of continuous data was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Categorical data are shown as counts and proportions (%) and compared with the chi-squared test. The 10-year deaths are shown as cumulative incidences calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method. Other analyzed outcomes are shown as cumulative incidences after accounting for the competing risk of death. Comparison of outcomes in groups according to diabetic status was performed with the univariable Cox proportional hazards model. The association between diabetic status and the study outcomes was adjusted for potential confounders using the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model. The level of multicolinearity among the variables was assessed by calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF). The following variables had a VIF < 5: age, sex, body mass index, arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, current smoking, extent of CAD, clinical presentation (acute coronary syndrome or stable CAD), history of myocardial infarction, history of PCI, serum creatinine, left ventricular ejection fraction, comorbidities, vessel size, SYNTAX score, type of drug-eluting stent, occluded right coronary artery, coronary artery dominance, lesion location, trifurcation morphology and stenting technique. These variables were entered into the Cox proportional hazards model. The proportionality of hazards assumption was tested according to the Grambsch and Therneau method [17]. The statistical analysis was performed using the R 4.1.0 Statistical Software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A two-sided p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Data

The study included 1257 patients who underwent PCI for unprotected LMCA disease. Of them 361 patients had DM. Baseline and angiographic/procedural data of patients with and without DM are shown in Supplemental Table S1 and Supplemental Table S2, respectively. Patients were categorized in groups according to the DM status and type of therapy: a group without DM (n = 896), a group with DM on oral antidiabetic drugs (n = 246) and a group with DM on insulin therapy (n = 115). Baseline data are shown in Table 1. There were significant differences between the groups with respect to the body mass index, proportions of patients with arterial hypertension, extent of CAD, serum creatinine, left ventricular ejection fraction, frequency of peripheral arterial disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the SYNTAX score. Among patients with diabetes, those on insulin therapy had significantly higher levels of glucated hemoglobin A1c than patients on oral antidiabetic drugs. The other variables did not differ significantly between the groups. Angiographic and procedural data are shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences across the groups except for the frequency of use of final kissing balloon. Main cardiovascular drugs prescribed at discharge are shown in Supplemental Table S3.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

Table 2.

Angiographic and procedural characteristics.

3.2. Clinical Outcome

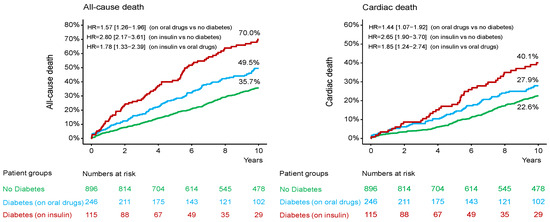

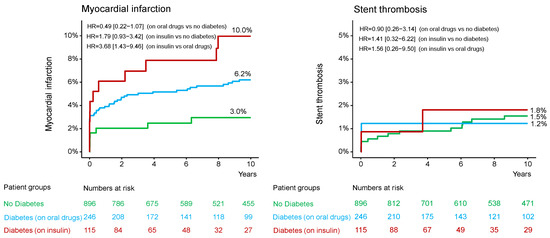

In patients without DM, diabetic patients on oral antidiabetic drug and diabetic patients on insulin therapy, the median [25–75th percentiles] follow-up was 11.3 [10.0–13.5] years, 11.2 [7.8–13.6] years and 11.1 [4.3–12.1] years, respectively (p = 0.392). The 10-year clinical outcome according to diabetic status is shown in the Supplemental Table S4. The 10-year clinical outcome in the study groups is shown in Table 3. Deaths of any cause (the primary endpoint) occurred in 477 patients (38%): 291 patients (35.7%) without DM, 111 diabetic patients (49.5%) on oral antidiabetic drugs and 75 diabetic patients (70.0%) on insulin therapy (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.57, 95% confidence interval [1.26–1.96] for the group with DM on oral antidiabetic drugs vs. the group without DM; HR = 2.80 [2.17–3.61] for the group with DM on insulin therapy vs. the group without DM and HR = 1.78 [1.33–2.39] for the group with DM on insulin therapy vs. the group with DM on oral antidiabetic drugs; Table 3 and Figure 1). Cardiac deaths occurred in 285 patients (60% of deaths): 181 patients (22.6%) without DM, 62 diabetic patients (27.9%) on oral antidiabetic drugs and 42 diabetic patients (40.1%) on insulin therapy (HR = 1.44 [1.07–1.92] for the group with DM on oral antidiabetic drugs vs. the group without DM; HR = 2.65 [1.90–3.70] for the group with DM on insulin therapy vs. the group without DM and HR = 1.85 [1.24–2.74] for the group with DM on insulin therapy vs. the group with DM on oral antidiabetic drugs; Table 3 and Figure 1). The 10-year incidence of myocardial infarction was significantly higher in diabetic patients on insulin therapy compared with diabetic patients on oral antidiabetic drugs (Figure 2; Table 3). There were no significant differences between the groups with respect to the 10-year incidence of definite stent thrombosis (Figure 2) and CABG, repeat PCI or stroke (Table 3). Time-to-event curves of the occurrence of CABG or repeat PCI at 10 years are shown in Supplemental Figure S1. The number, type and location of coronary interventions are shown in Supplemental Table S5. The frequency of coronary interventions in each coronary artery, the time interval to the first repeat PCI and the time intervals between repeat PCIs are shown in Supplemental Table S6.

Table 3.

Ten-year clinical outcome.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves 10-year all-cause (left) panel and cardiac mortality (right) panel. HR = hazard ratio.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of 10-year myocardial infarction and definite stent thrombosis. HR = hazard ratio.

The 10-year clinical outcome according to metabolic control (assessed by hemoglobin A1c level) was analyzed in patients with DM. The median [95% confidence interval] value of hemoglobin A1c was 6.9% [6.3–7.7%]. Patients were categorized in groups according to the hemoglobin A1c < median (n = 146) and ≥median (n = 146). Clinical outcome according to the glucated hemoglobin level is shown in Supplemental Table S7.

The association between diabetic status, antidiabetic therapy and clinical outcome was adjusted in the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model (see Methods for variables entered into the model). The risk for 10-year all-cause mortality was higher in diabetic patients requiring insulin therapy than patients without DM (adjusted HR = 2.10 [1.58–2.78], p < 0.001) or diabetic patients on oral antidiabetic drugs (adjusted HR = 1.71 [1.25–2.32], p < 0.001). The risk for all-cause mortality was higher in diabetic patients on oral antithrombotic therapy than patients without DM but the level of statistical significance was not achieved (adjusted HR = 1.23 [0.98–1.55], p = 0.080). The same pattern of association was observed for cardiac mortality. The adjusted risk for myocardial infarction was significantly higher in diabetic patients on insulin therapy than diabetic patients on oral antidiabetic drugs (adjusted HR = 3.03 [1.09–8.43], p = 0.034). There were no significant associations between diabetic status and/or therapy and the risk for definite stent thrombosis, CABG, repeat PCI, stroke or nontarget lesion revascularization (Table 4).

Table 4.

Hazard ratios (with 95% confidence interval) for 10-year clinical outcomes after adjustment in the Cox proportional hazards model.

4. Discussion

The main findings of the study may be summarized as follows: (1) In patients with LMCA disease undergoing PCI, DM was associated with a significantly higher incidence of 10-year mortality. (2) Patients with DM receiving insulin therapy had significantly higher rates of 10-year all-cause and cardiac mortality compared with patients without DM or diabetic patients on oral antidiabetic drugs. (3) Diabetic patients receiving insulin therapy had a significantly higher 10-year risk of myocardial infarction than diabetic patients on antidiabetic drugs. (4) There were no significant differences according to diabetic status or type of therapy among diabetic patients with respect to the 10-year rates of definite stent thrombosis, repeat PCI, CABG, target lesion revascularization, stroke or nontarget lesion revascularization.

Previous studies have demonstrated worse outcomes in diabetic patients with LMCA disease after PCI or CABG compared with nondiabetic patients. A pooled analysis of 4 randomized trials of patients with LMCA disease and a low-to-intermediate SYNTAX score who underwent PCI or CABG showed that DM was associated with higher 5-year rates of death, myocardial infarction, stroke or repeat revascularization [5]. The 5-year survival did not differ between PCI or CABG regardless of diabetic status [5]. Our study showed that an association between DM and higher risk of all-cause death after PCI for unprotected LMCA disease persists up to 10 years after intervention. However, the crucial finding of our study was the significant association between the type of antidiabetic therapy and 10-year mortality after PCI. The time-to-event curves showed a progressive widening of the difference in mortality between the groups with various types of antidiabetic therapy suggesting that the difference in the risk for mortality according to the type of antidiabetic therapy even may increase over time. The study by Gaba et al. [5]. also demonstrated gradients in the risk for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality across diabetic patients on insulin therapy (highest risk), diabetic patients on oral antidiabetic drugs and patients without DM (lowest risk). Other studies have also reported an association between the type of therapy in diabetic patients and the risk for mortality after PCI. The FAST-MI (French registry of Acute ST elevation or non-ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction) registry that included 1221 diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction discharged alive from the hospital showed that insulin prescription at discharge was associated with 72% higher adjusted risk for mortality at 5 years [18]. A recent study that included 869 patients undergoing PCI for unprotected left main CAD showed that insulin-treated patients but not those treated with oral antidiabetic drugs had significantly higher rates of all-cause death, spontaneous myocardial infarction or major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events at one year [19]. Our study also showed that insulin-treated diabetic patients have an increased risk of mortality up to 10 years compared with patients without DM or diabetic patients on oral antidiabetic drugs. Even though in our study, diabetic patients on oral antidiabetic drugs had a higher risk of all-cause mortality compared with patients without DM, the association was attenuated after adjustment. However, the SYNTAX Extended Survival (SYNTAXES) study showed that both noninsulin and insulin therapy were independent correlates of 10-year mortality in patients with DM [20]. Nevertheless, the risk of mortality was higher in insulin-treated patients.

Our study adds to the existing evidence that insulin therapy signifies an increased risk for long-term mortality in diabetic patients with LMCA disease undergoing PCI. Although the underlying reasons for this finding are not entirely clear, a number of putative mechanisms may be offered. First, insulin therapy might have been initiated in diabetic patients in whom the adequate metabolic control was not achieved using the oral antidiabetic drug therapy. In this regard, insulin therapy may be seen as a marker of advanced and more severe disease, which is associated with a worse prognosis. Higher HbA1c values in patients receiving insulin therapy may denote difficulties in achieving an optimal metabolic control in these patients. Second, compensatory hyperinsulinemia is a hallmark of DM that may be further exacerbated by exogenous insulin [21]. Hyperinsulinemia including iatrogenic hyperinsulinemia, particularly if insulin is inadequately titrated, is associated with adverse events that increase the risk of cardiomyopathy, induce endothelial dysfunction, promote atherosclerosis, cause renal retention of sodium and water and increase vasoreactivity and blood pressure [21]. Cardiovascular effects of insulin therapy in diabetic patients have been recently reviewed [21]. Third, insulin therapy is associated with the risk of hypoglycemia [22,23]. Hypoglycemia, particularly if severe and recurrent, set into motion pathological events that markedly increase the risk for adverse outcomes, particularly in patients with high cardiovascular risk [21,24]. Hypoglycemia activates pro-inflammatory mediators [25,26], increases platelet and coagulation activation [27], increases oxidative stress [21], causes endothelial dysfunction and reduces systemic fibrinolysis [28]. These effects may promote a prothrombotic state that increases the risk of thrombotic events following PCI in diabetic patients. Hypoglycemia causes sympathetic nerve activation and catecholamine release increasing heart rate, systolic blood pressure, myocardial contractility and stroke volume leading to exacerbation of myocardial ischemia [29]. Thus, insulin-therapy-induced hypoglycemia may increase the risk of mortality in diabetic patients following PCI. The Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE) study that included diabetic patients showed that severe hypoglycemia was associated with a higher adjusted risk for major macrovascular events, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality at 5 years [30].

The current study has strengths and limitations. The main strengths consist in including of a relatively large number of patients with LMCA disease, angiographic analysis performed in the centralized core laboratory, stringent criteria for event adjudication and long-term follow-up. The study has also a number of limitations. First, although the study patients were obtained from the randomized studies and the current analysis was prespecified in the setting of source trials, the antidiabetic therapy (and group definition) was prescribed on a nonrandomized basis. The patient categorization in groups according to the antidiabetic therapy was defined at discharge and we have no information with respect to any change in the antidiabetic therapy during the follow-up. Second, conditional on the time of recruitment of patients in the primary trials, the impact of newer generations of coronary stents, antithrombotic drugs and antidiabetic drugs (glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists or sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors) cannot be assessed. In addition, we have no information on the types (or dosis) of oral antidiabetic drugs prescribed or whether these drugs were used concomitantly with insulin in patients receiving insulin therapy. Third, the number of diabetic patients was relatively small. Moreover, in approximately 20% of patients with DM, the hemoglobin A1c values were missing. Thus, the limited number of events due to these factors may have led to an inconclusive analysis with respect to the association of metabolic control of DM with the clinical outcomes. Although we used the World Health Organization criteria for the de novo (during index hospitalization) diagnosis of DM, the impact of stress-induced hyperglycemia cannot be entirely neglected. Fourth, conditional on the time of patient enrollment in the source studies, patients included in this analysis (particularly patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes) may have received a somewhat outdated therapy in terms of drug-eluting stents and antithrombotic therapy [31]. Fifth, although we adjusted for a wide range of demographical and clinical variables, the potential impact of residual confounders on the association between diabetic status (and antidiabetic therapy) and clinical outcome cannot be ignored.

In conclusion, in patients with LMCA disease undergoing PCI, DM was associated with a higher 10-year incidence of all-cause mortality. Diabetic patients with LMCA disease on insulin therapy showed a higher risk of 10-year mortality compared with patients without DM or diabetic patients on oral antidiabetic drugs. Insulin therapy was an independent correlate of an increased risk of 10-year all-cause and cardiac mortality. By showing that patients with DM on insulin therapy did worse compared with other groups of patients, these findings may have implications with respect to the decision-making and a personalized approach in selecting the most appropriate revascularization strategy in diabetic patients with LMCA disease. Specifically designed and well-powered randomized studies are eagerly needed to establish the best management strategy in patients with LMCA disease and DM.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm14248851/s1, Table S1. Baseline characteristics in patients without and with diabetes mellitus; Table S2. Angiographic and procedural characteristics in patients without and with diabetes mellitus; Table S3. Therapy at discharge; Table S4. Ten-year clinical outcome according to diabetic status; Table S5. Number, type and location of repeat percutaneous coronary interventions; Table S6. Number, type, location and timing of repeat percutaneous coronary interventions; Table S7. Ten-year clinical outcome according to hemoglobin A1c in patients with diabetes; Figure S1: Time-to-event curves of coronary artery bypass surgery (left panel) and repeat percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Author Contributions

J.B., A.K., G.N. and J.W. were involved in the conception and design of the work. G.N. and J.W. drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved in the data acquisition and interpretation. All authors have read, revised and approved the manuscript. All authors agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Munich Technical University of Munich approval (code: 1339/05; date 28 June 2005 and code: 1975/07; date 18 December 2007).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent and institutional ethics committee approval were obtained in the setting of primary studies.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests regarding this manuscript. Besides the following disclosures exist: CK received speaker fees from AstraZeneca. SK reports speaker and consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Bentley, speaker fees from Abbott, Boehringer-Ingelheim and Translumina and a research grant from Bentley. HS received consulting fees from AMGEN, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo and Servier, speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer Vital, Novartis, Servier, Sanofi-Aventis, Synlab, Bristol-Myers Squibb and AMARIN, and research grant from AstraZeneca, St. Jude and Boston Scientific. JW reports speaker fees from Abbott Vascular, AstraZeneca, Translumina and Philips and institutional research grant from Abott Vascular. All other authors have no disclosures to declare.

References

- Ielasi, A.; Chieffo, A. Tools & techniques: Left main coronary artery percutaneous coronary intervention. EuroIntervention 2011, 6, 1020–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carson, J.L.; Scholz, P.M.; Chen, A.Y.; Peterson, E.D.; Gold, J.; Schneider, S.H. Diabetes mellitus increases short-term mortality and morbidity in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002, 40, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roffi, M.; Angiolillo, D.J.; Kappetein, A.P. Current concepts on coronary revascularization in diabetic patients. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 2748–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wit, M.A.; de Mulder, M.; Jansen, E.K.; Umans, V.A. Diabetes mellitus and its impact on long-term outcomes after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Acta Diabetol. 2013, 50, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaba, P.; Sabik, J.F.; Murphy, S.A.; Bellavia, A.; O’Gara, P.T.; Smith, P.K.; Serruys, P.W.; Kappetein, A.P.; Park, S.J.; Park, D.W.; et al. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Versus Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting in Patients With Left Main Disease With and Without Diabetes: Findings From a Pooled Analysis of 4 Randomized Clinical Trials. Circulation 2024, 149, 1328–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, L.J.; Cleveland, J.C.; Welt, F.G.; Anwaruddin, S.; Bonow, R.O.; Firstenberg, M.S.; Gaudino, M.F.; Gersh, B.J.; Grubb, K.J.; Kirtane, A.J.; et al. A Practical Approach to Left Main Coronary Artery Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 2119–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, M.A.; Persson, J.; Buccheri, S.; Odenstedt, J.; Sarno, G.; Angeras, O.; Volz, S.; Todt, T.; Gotberg, M.; Isma, N.; et al. Trends in Clinical Practice and Outcomes After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention of Unprotected Left Main Coronary Artery. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e024040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatine, M.S.; Bergmark, B.A.; Murphy, S.A.; O’Gara, P.T.; Smith, P.K.; Serruys, P.W.; Kappetein, A.P.; Park, S.J.; Park, D.W.; Christiansen, E.H.; et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents versus coronary artery bypass grafting in left main coronary artery disease: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet 2021, 398, 2247–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Wei, Y.; Li, X.; Jhummun, V.; Ahmed, M.A. Ten-Year Outcomes of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Versus Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Suffering from Left Main Coronary Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Ther. 2021, 12, 1041–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Ahn, J.M.; Yoon, Y.H.; Kang, D.Y.; Park, S.Y.; Ko, E.; Park, H.; Cho, S.C.; Park, S.; Kim, T.O.; et al. Long-Term (10-Year) Outcomes of Stenting or Bypass Surgery for Left Main Coronary Artery Disease in Patients With and Without Diabetes Mellitus. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e015372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disney, L.; Ramaiah, C.; Ramaiah, M.; Keshavamurthy, S. Left Main Coronary Artery Disease in Diabetics: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention or Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting? Int. J. Angiol. 2021, 30, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kralisz, P.; Dabrowski, E.J.; Dobrzycki, S.; Kozlowska, W.U.; Lipska, P.O.; Nowak, K.; Gugala, K.; Prokopczuk, P.; Mezynski, G.; Swieczkowski, M.; et al. Long-term impact of diabetes on mortality in patients undergoing unprotected left main PCI: A propensity score-matched analysis from the BIA-LM registry. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehilli, J.; Kastrati, A.; Byrne, R.A.; Bruskina, O.; Iijima, R.; Schulz, S.; Pache, J.; Seyfarth, M.; Massberg, S.; Laugwitz, K.L.; et al. Paclitaxel- versus sirolimus-eluting stents for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 53, 1760–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehilli, J.; Richardt, G.; Valgimigli, M.; Schulz, S.; Singh, A.; Abdel-Wahab, M.; Tiroch, K.; Pache, J.; Hausleiter, J.; Byrne, R.A.; et al. Zotarolimus- versus everolimus-eluting stents for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 2075–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sianos, G.; Morel, M.A.; Kappetein, A.P.; Morice, M.C.; Colombo, A.; Dawkins, K.; van den Brand, M.; Van Dyck, N.; Russell, M.E.; Mohr, F.W.; et al. The SYNTAX Score: An angiographic tool grading the complexity of coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention 2005, 1, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Cutlip, D.E.; Windecker, S.; Mehran, R.; Boam, A.; Cohen, D.J.; van Es, G.A.; Steg, P.G.; Morel, M.A.; Mauri, L.; Vranckx, P.; et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: A case for standardized definitions. Circulation 2007, 115, 2344–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grambsch, P.M.; Therneau, T.M. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 1994, 81, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataille, V.; Ferrieres, J.; Danchin, N.; Puymirat, E.; Zeller, M.; Simon, T.; Carrie, D. Increased mortality risk in diabetic patients discharged from hospital with insulin therapy after an acute myocardial infarction: Data from the FAST-MI 2005 registry. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2019, 8, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis, A.; Siasos, G.; Dangas, G.; Power, D.; Sartori, S.; Vavouranakis, M.; Tsioufis, K.; Leone, P.P.; Vogel, B.; Cao, D.; et al. Significance of diabetes mellitus status in patients undergoing percutaneous left main coronary artery intervention. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 104, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Serruys, P.W.; Gao, C.; Hara, H.; Takahashi, K.; Ono, M.; Kawashima, H.; O’Leary, N.; Holmes, D.R.; Witkowski, A.; et al. Ten-year all-cause death after percutaneous or surgical revascularization in diabetic patients with complex coronary artery disease. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 43, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, M.E.; O’Keefe, J.H.; Bell, D.S.H.; Schwartz, S.S. Insulin Therapy Increases Cardiovascular Risk in Type 2 Diabetes. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 60, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, C.J.; Ruderman, N.B.; Prentki, M. Intensive insulin for type 2 diabetes: The risk of causing harm. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013, 1, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chico, A.; Vidal-Rios, P.; Subira, M.; Novials, A. The continuous glucose monitoring system is useful for detecting unrecognized hypoglycemias in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes but is not better than frequent capillary glucose measurements for improving metabolic control. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 1153–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paty, B.W. The Role of Hypoglycemia in Cardiovascular Outcomes in Diabetes. Can. J. Diabetes 2015, 39 (Suppl. 5), S155–S159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandona, P.; Chaudhuri, A.; Dhindsa, S. Proinflammatory and prothrombotic effects of hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1686–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joy, N.G.; Hedrington, M.S.; Briscoe, V.J.; Tate, D.B.; Ertl, A.C.; Davis, S.N. Effects of acute hypoglycemia on inflammatory and pro-atherothrombotic biomarkers in individuals with type 1 diabetes and healthy individuals. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberer, F.; Pferschy, P.N.; Tripolt, N.J.; Sourij, C.; Obermayer, A.M.; Pruller, F.; Novak, E.; Reitbauer, P.; Kojzar, H.; Prietl, B.; et al. Hypoglycaemia leads to a delayed increase in platelet and coagulation activation markers in people with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin only: Results from a stepwise hypoglycaemic clamp study. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2020, 22, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, N.G.; Tate, D.B.; Younk, L.M.; Davis, S.N. Effects of Acute and Antecedent Hypoglycemia on Endothelial Function and Markers of Atherothrombotic Balance in Healthy Humans. Diabetes 2015, 64, 2571–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.J.; Frier, B.M. Vascular disease and diabetes: Is hypoglycaemia an aggravating factor? Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2008, 24, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoungas, S.; Patel, A.; Chalmers, J.; de Galan, B.E.; Li, Q.; Billot, L.; Woodward, M.; Ninomiya, T.; Neal, B.; MacMahon, S.; et al. Severe hypoglycemia and risks of vascular events and death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadafora, L.; Pastena, P.; Cacciatore, S.; Betti, M.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; D’Ascenzo, F.; De Ferrari, G.M.; De Filippo, O.; Versaci, F.; Sciarretta, S.; et al. One-Year Prognostic Differences and Management Strategies between ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Insights from the PRAISE Registry. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2025, 25, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).