Abstract

Background: The management of hard-to-heal wounds poses a major clinical challenge due to heterogeneous etiology and significant global healthcare costs (estimated at USD 148.64 billion in 2022). Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT and Gemini, are emerging as potential decision-support tools. This study aimed to rigorously assess the accuracy and reliability of ChatGPT and Gemini in the visual description and initial therapeutic management of complex wounds based solely on clinical images. Methods: Twenty clinical images of complex wounds from diverse etiologies were independently analyzed by ChatGPT (version dated 15 October 2025) and Gemini (version dated 15 October 2025). The models were queried using two standardized, concise prompts. The AI responses were compared against a clinical gold standard established by the unanimous consensus of an expert panel of three plastic surgeons. Results: Statistical analysis showed no significant difference in overall performance between the two models and the expert consensus. Gemini achieved a slightly higher percentage of perfect agreement in management recommendations (75.0% vs. 60.0% for ChatGPT). Both LLMs demonstrated high proficiency in identifying the etiology of vascular lesions and recognizing critical “red flags,” such as signs of ischemia requiring urgent vascular assessment. Noted divergences included Gemini’s greater suspicion of potential neoplastic etiology and the models’ shared error in suggesting Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT) in a case potentially contraindicated by severe infection. Conclusions: LLMs, particularly ChatGPT and Gemini, demonstrate significant potential as decision-support systems and educational tools in wound care, offering rapid diagnosis and standardized initial management, especially in non-specialist settings. Instances of divergence in systemic treatments or in atypical presentations highlight the limitations of relying on image-based reasoning alone. Ultimately, LLMs serve as powerful, scalable assets that, under professional supervision, can enhance diagnostic speed and improve care pathways.

1. Introduction

Plastic and reconstructive surgeons are routinely confronted with the management of hard-to-heal wounds, a broad category encompassing chronic wounds characterized by delayed, arrested, or disrupted healing due to intrinsic and/or extrinsic factors acting on the patient or the wound itself [1]. Although several definitions have been proposed, no universally accepted temporal threshold currently exists beyond which a wound is unequivocally classified as chronic [2].

The etiology of these wounds is highly heterogeneous and, in many cases, multiple pathogenic mechanisms interact synergistically to promote their onset and hinder normal healing processes [3]. Chronic or hard-to-heal wounds are generally classified into two major groups [4,5]: typical wounds, which account for approximately 80% of all chronic lesions and include pressure, venous, arterial and diabetic foot ulcers, and atypical or rare wounds, such as chronic traumatic, dehiscent or infected surgical, neoplastic and radiation-induced ulcers and other less common entities. The absence of a universally accepted definition complicates efforts to estimate the global prevalence of chronic wounds [6]. However, recent analyses suggest that these conditions affect approximately 1–2% of the world’s population [7], with global healthcare expenditure for their management estimated at around USD 148.64 billion in 2022 [8].

Hard-to-heal wounds constitute a major clinical challenge due to frequent biofilm formation and the absence of standardized diagnostic tools capable of detecting early determinants of chronicity [9,10]. Therapeutic management is further complicated by the poor response to conventional treatments and the growing need for individualized, multimodal therapeutic strategies [11]. It is well established that the delayed initiation of targeted therapy increases the risk of infection, impaired healing, amputation, and escalating healthcare costs [8,12]. Accordingly, early and accurate diagnosis, combined with timely, patient-specific intervention, is essential to optimize healing outcomes and mitigate the clinical and economic burden associated with chronic wounds.

For more than two decades, the TIME framework [13,14] has been recognized as a structured and comprehensive approach to the management of hard-to-heal wounds. The acronym represents the four fundamental components on which the model is based: Tissue (removal of nonviable or necrotic tissue), Infection/Inflammation (identification and control of infection and inflammation), Moisture balance (maintenance of an optimal moisture level within the wound bed), and Edge (stimulation of epithelial edge advancement and wound margin migration). Subsequent adaptations have expanded the model to enhance therapeutic individualization. The TIME Clinical Decision Support Tool (TIME CDST), for instance, incorporates broader assessments of the patient’s overall clinical condition and systemic factors, in addition to local wound-bed parameters [15]. The modified TIME-H model further emphasizes the role of patient comorbidities (H—Health), integrating a scoring system designed to predict both the likelihood and timeframe of wound healing based not only on wound type, but also on patient-specific health status. Its prognostic accuracy ranges from approximately 63% in vascular-origin wounds to 88% in surgical wounds [16].

In this complex scenario, fueled by new therapeutic approaches and increasingly robust knowledge in wound management, Large Language Models (LLMs) are emerging as potentially transformative tools in clinical practice. Their capability to convert heterogeneous data into structured and actionable information, and to extract key elements from provided inputs to suggest an adequate management approach for complex wounds, has been shown to enhance the precision of wound assessments, facilitate early infection detection, and streamline clinical workflows [17]. When integrated with computer vision models (a term validated and used here), as demonstrated by tools like SkinGPT-4, LLMs have proven adept at identifying salient features within wound images, generating differential diagnoses, and proposing therapeutic strategies. This functionality is particularly applicable in remote triage pathways [18]. In routine clinical practice, these technologies could therefore support non-specialist personnel and nursing teams in the early identification of warning signs, suggest up-to-date or equivalent dressing options based on the latest evidence, reduce the time required to initiate appropriate therapy, and limit heterogeneity in initial decision-making [19,20]. Furthermore, LLMs applied in the field of complex wounds could serve as a training tool for junior plastic surgeons or less experienced practitioners, offering a sophisticated platform for diagnostic and therapeutic consultation and comparison [21,22].

These opportunities, however, are counterbalanced by significant safety and reliability limitations. LLMs remain vulnerable to “hallucination,” defined as the generation of plausible but clinically erroneous assertions [23,24]. Additionally, they risk amplifying biases already present in their training data. Errors of this nature can translate into misleading or potentially harmful recommendations, if not adequately controlled through the analysis of authoritative sources and human supervision. Recent studies have also highlighted the risk of “automation bias,” which is the tendency of clinicians to attribute excessive credibility to linguistically coherent, but not always correct AI-generated responses [25,26]. This underscores the need for cautious implementation strategies and systematic monitoring of errors, especially as non-specialists, who benefit most from decision support systems, are often the most susceptible to automation bias.

The currently available literature presents substantial gaps that limit the possibility of a fully informed clinical adoption of LLMs in complex wound care. A large portion of the available results is derived from optimized and synthetic datasets or benchmarks not representative of day-to-day practice. Crucially, there is a lack of studies that rigorously compare the therapeutic plans proposed by AI with those developed by independent expert panels [27]. Consequently, claims regarding the clinical utility of LLMs remain provisional and require extensive validation in representative real-world cohorts.

In view of the aforementioned limitations, the present study was meticulously designed to rigorously assess the accuracy and reliability of two prominent LLMs, ChatGPT and Gemini, in the descriptive analysis and management of complex wounds, based exclusively on a single clinical image. This approach replicates a realistic triage scenario, such as a remote teleconsultation, a community nursing assessment, or an initial emergency department evaluation, where contextual information regarding patient comorbidities and medical history is inherently limited. Furthermore, this setting directly addresses the models’ potential for educational application for trainees and less experienced healthcare providers, serving as a structured tool for decision support.

The primary objective of this study is to determine the degree of concordance between the initial therapeutic plans suggested by the AI and those formulated by an expert panel of plastic surgeons, in a clinically realistic context based solely on images of complex wounds, without access to other patient information. Secondary objectives include evaluating the descriptive accuracy of the models, their ability to identify clinically relevant elements (such as necrosis, maceration, or signs of infection), their decision safety, defined as the absence of potentially harmful recommendations, and the educational value of the responses for non-specialist healthcare personnel.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and current regulations governing scientific research and data protection. Since all wound images used were fully anonymized and obtained from publicly accessible sources, formal approval from an ethics committee was not required. All procedures followed international guidelines for observational research involving public domain visual material.

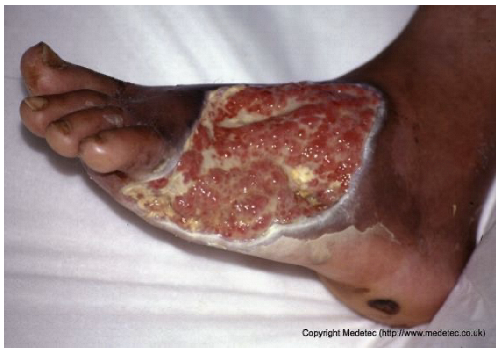

Clinical images of wounds of different etiologies and levels of complexity were selected to represent a broad spectrum of conditions, including traumatic, postoperative, infected, and ulcerative lesions. The images were obtained from the website https://www.medetec.co.uk/files/medetec-image-databases.html (accessed on 9 October 2025), which authorizes the use of its content for research and scientific dissemination purposes. Permission for image use was granted according to the site’s terms, and all images were processed in a completely anonymized form, with the removal of metadata and any identifiable elements.

Each image was analyzed by two large language models (LLMs): ChatGPT (version dated 15 October 2025) and Gemini (version dated 15 October 2025). Both models were queried independently, with no exchange of information or iterative regeneration, using two standardized prompts applied uniformly to all cases: Provide a brief, objective clinical description of the wound. Focus only on visible features and key clinical details (max 3 lines) and state the most appropriate wound dressing or basic management plan. Give only the essential recommendation without explanation (max 2 lines). For each image, each prompt was submitted once to each model and the first complete response was recorded, without repeating or regenerating the query, using the default web interface configuration.

These prompts, reported in full in the manuscript, were designed to obtain from each model a concise clinical description and an essential therapeutic recommendation, replicating a visual triage scenario without access to patient history or additional clinical data.

In parallel, a panel of 3 experienced plastic surgeons analyzed the same images, providing an objective clinical description and a corresponding management plan for each case. Their evaluations were discussed collectively until a unanimous consensus was reached, which was taken as the clinical reference standard for the study. The surgeons reviewed each case together in a structured consensus session, discussing any divergent opinions until a single unanimous diagnosis and initial management plan were agreed. For each AI–surgeon comparison, concordance was rated on a three-level ordinal scale, where 0 indicated a discordant (inaccurate or unsafe) response, 1 a partially concordant (incomplete or partially correct) response, and 2 a fully concordant response (clinically accurate and aligned with the expert consensus).

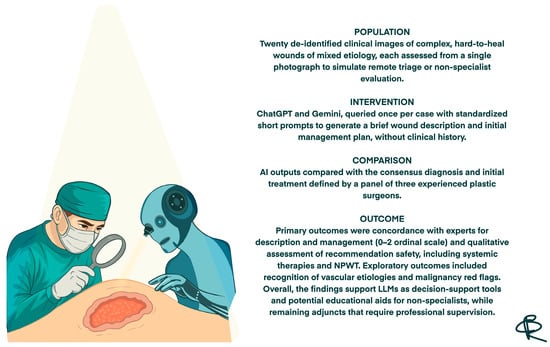

In PICO terms, the Population consisted of de-identified clinical images of complex hard-to-heal wounds of different etiologies and severities; the Intervention corresponded to the assessments generated by the two large language models (ChatGPT and Gemini) in response to standardized prompts; the Comparator was the consensus diagnosis and initial management plan provided by a panel of experienced plastic surgeons; and the primary Outcomes were the degree of concordance between AI and experts for wound description and initial management, together with the safety of the recommendations (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structured summary of the study design and main outcomes based on the PICO framework.

3. Results

All 20 wound cases were processed by both models, and case-by-case descriptive and management outputs are summarized in Table 1. Table 2 reports the visual concordance matrix between each AI model and the surgeons’ consensus for wound description and initial management. As shown in Table 3, for wound description the mean concordance scores with the expert panel were 1.50 (SD 0.51) for ChatGPT and 1.55 (SD 0.69) for Gemini, with fully concordant descriptions in 10/20 (50.0%) and 13/20 (65.0%) cases, respectively. For initial management, mean scores were 1.60 (SD 0.50) for ChatGPT and 1.70 (SD 0.57) for Gemini, with fully concordant management in 12/20 (60.0%) and 15/20 (75.0%) cases; the proportion of fully concordant management decisions was significantly higher than 50% for Gemini (p = 0.041). Inter-model agreement, measured by Cohen’s κ, was 0.000 for wound descriptions and 0.255 for management. Overall performance scores (sum of description and management) were 3.10 (SD 0.64) for ChatGPT and 3.25 (SD 0.97) for Gemini (p = 0.388).

Table 1.

Comparison between AI-generated wound assessments and surgeons’ evaluations. Each case was analyzed by ChatGPT and Gemini using two standardized prompts: Provide a brief, objective clinical description of the wound. Focus only on visible features and key clinical details (max 3 lines). State the most appropriate wound dressing or basic management plan. Give only the essential recommendation without explanation (max 3 lines). The table presents the descriptions and management suggestions generated by both models alongside the corresponding surgeon’s evaluation and recommended treatment.

Table 2.

Visual concordance matrix comparing AI and surgeons’ evaluations. Each case was assessed by ChatGPT and Gemini for wound description and management. The color scale indicates the agreement level with the surgeons’ consensus: Red = discordant (inaccurate or unsafe response); Yellow = partially concordant (incomplete or partially correct); Green = fully concordant (clinically accurate and aligned with expert consensus).

Table 3.

Quantitative performance metrics of ChatGPT and Gemini compared with the expert panel.

4. Discussion

Our study assessed the accuracy and clinical applicability of LLMs, ChatGPT and Gemini, in the visual description and therapeutic management of 20 hard-to-heal wounds, with each evaluated solely from a photographic image. Although statistical analysis did not reveal significant differences in overall performance compared with the gold standard, the qualitative assessment provides critical insights into how these technologies may be integrated into clinical practice. However, these non-significant results should not be interpreted as formal equivalence; with only 20 cases, the study is underpowered to detect modest but potentially relevant differences in performance and should therefore be regarded as exploratory.

A particularly noteworthy finding is the proficiency demonstrated by both models in identifying the etiology of vascular lesions. ChatGPT and Gemini consistently recognized the hallmark clinical features of venous ulcers, like edema, hyperpigmentation, anatomical location, and correctly recommended compression therapy as the cornerstone of management. Similarly, with specific reference to case 8, which presented critical limb ischaemia with dry necrosis, both models demonstrated high diagnostic sensitivity, achieving a perfect agreement (score 2) by appropriately advising urgent vascular evaluation and avoiding unsafe recommendations such as aggressive debridement. These findings align with a recent meta-analysis by Jimenez [28], which highlighted the capability of AI systems to correctly identify chronic wound etiology and propose appropriate treatment plans. This capacity for reliable aetiological discrimination represents a key strength and highlights the potential role of LLMs as first-line screening and decision-support tools, for example, in community-based nursing settings, as suggested by Pressmann and Liang [19,20], facilitating the prompt identification of patients requiring urgent medical management. From a practical perspective, these findings suggest that such tools could be piloted as structured aids for early wound triage in community and emergency settings, and as case-based learning resources that help trainees and non-specialist staff practise systematic description and initial management of complex wounds.

The models diverged substantially in therapeutic planning. Overall, Gemini tended to produce more structured, sequential, and algorithmic management plans; yet this methodical approach was not without pitfalls in complex scenarios, as was evident in cases 3, 8, 13, and 18. By contrast, ChatGPT adopted a more conservative stance and adhered closely to prompt instructions, although it frequently conveyed unwarranted confidence and lacked the probabilistic nuance expected in scenarios with inherent diagnostic uncertainty. This pattern of rigid adherence by ChatGPT versus the broader elaborative freedom exhibited by Gemini aligns with literature, specifically the works of Salbas et al. on brain MRI sequences [29] and Sami et al. within pediatric radiology [30]. In our comparison, Gemini often appeared more attentive to the description and treatment of secondary lesions or the perilesional skin compared to ChatGPT. This discrepancy may stem from ChatGPT’s stricter adherence to the prompt, which likely constrained its field of analysis. Future studies should therefore explore alternative, less restrictive prompting strategies to assess whether differences in output length and structure reflect true reasoning performance or are primarily driven by prompt sensitivity.

An inconsistency was noted regarding systemic antibiotic therapy recommendations. Specifically, in case 2, ChatGPT failed to propose necessary antibiotic treatment. This omission represents a significant risk, particularly if we consider the potential future use of these systems for home-based wound management by non-professionals. However, this was not a systematic failure: the same model correctly suggested systemic antibiotics in other instances of suspected infection (case 5 and 9), aligning with previous findings by Nelson et al. [17] regarding the potential utility of AI in early infection detection. Notably, despite variability in systemic prescribing, both models consistently recommended antimicrobial dressings in suspected infection, demonstrating a reliable understanding of local infection control.

Interestingly, both ChatGPT and Gemini erroneously proposed Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT) in the case of an infected abdominal wound dehiscence (case 10), failing to recognize the potential signs of severe infection which would contraindicate immediate NPWT without prior radical debridement. This error illustrates how a narrowly framed prompt focused on local wound management, without explicitly requesting systemic evaluation, can divert the model’s attention from critical priorities such as sepsis workup and urgent surgical re-exploration. Consequently, the models may have prioritized wound bed preparation over a more urgent and aggressive diagnostic and therapeutic pathway. This finding underscores the fundamental limitation of relying on LLMs for critical decision-making, caveat already emphasized by Aljindan in oculoplastics [31] and Gomez-Cabello in plastic surgery [32]: clinical judgment and systemic evaluation cannot be delegated to image-based reasoning alone. Beyond this example, the discrepancies summarized in Table 1 span a spectrum from benign variability in dressing choice, through conditionally unsafe delays or omissions in systemic therapy, to clearly unsafe recommendations, and were qualitatively considered in our safety assessment.

Another significant shortcoming observed is the difficulty both models exhibited in recognizing the etiology of a lesion when it appeared in an atypical anatomical location. This was evident in case 12 (supposed pressure lesion on the lateral aspect of the first metatarsal head) and case 16 (supposed pressure ulcer on the mandibular area). This deficiency likely reflects the statistical nature of LLM training: when a pathology is strongly associated with a canonical anatomical site in the medical literature, the model may struggle to identify it when it occurs out of context. This finding aligns with evidence from dermatological AI research, where diagnostic accuracy significantly degrades when anatomical priors are missing or when lesions occur in sites historically underrepresented in training datasets, such as acral or mucosal regions [33,34]. This suggests a lack of true pathophysiological reasoning, relying instead on pattern matching that fails when the presentation is non-standard. More broadly, these errors likely reflect biases in the underlying training data distributions and highlight the need for curated, anatomically diverse wound image datasets when developing and deploying LLM-based tools for clinical use.

Despite these weaknesses, an additional strength, particularly for Gemini, warrants emphasis: its feature-extraction ability in atypical wounds. Gemini more readily suspected the potential neoplastic nature of certain complex wounds (e.g., breast ulceration and a scalp lesion) and correctly recommended diagnostic biopsy, whereas ChatGPT more often defaulted to standard wound-care protocols.

This study presents several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the sample size of cases analyzed is relatively small and may not capture the full variability of AI responses across the full spectrum of hard-to-heal wounds, so the present study should be regarded as exploratory and hypothesis-generating. Second, the evaluation was primarily text-based; as visual inspection is the gold standard in plastic surgery, the inability to assess the true multimodal capabilities of the models limits the generalisability of our findings to real-world clinical practice [27]. In particular, relying on single still images without patient history, comorbidities, perfusion data or longitudinal evolution represents a methodological constraint, as real-world wound assessment is inherently multimodal. Additionally, the influence of prompt engineering must be considered: while the input instructions were designed to be targeted and adequate for eliciting comprehensive and non-dispersive answers, further optimization of the prompts could potentially alter the models’ performance. In this regard, a divergence in instruction adherence was also observed: only ChatGPT strictly complied with the limitations regarding response length, whereas Gemini consistently generated outputs exceeding the requested parameters.

More fundamentally, condensing complex wound assessment and triage decisions into very short, three-line prompts inevitably removes much of the clinical context that would normally guide expert judgment. This design likely biases the models toward simplified, pattern-based answers and may underestimate their potential performance in more realistic, context-rich settings. Future studies should therefore test multi-step conversational prompts and multimodal inputs that combine images with structured clinical data, to better approximate real-world clinical workflows. Furthermore, the rapid evolution of LLMs means that the versions evaluated may already have been superseded by newer iterations with different behaviors. Finally, the assessment of “correctness” relied on qualitative expert judgment without a double-blinded review, introducing an element of subjectivity. Future studies should therefore adopt independent, blinded expert ratings and report inter-rater reliability.

Future research should aim to expand upon the foundational findings presented here. While this study intentionally utilized widely accessible, free-to-use AI models to ensure reproducibility and simulate a realistic scenario applicable to daily practice, future investigations could extend this comparison to include other currently available general-purpose LLMs, as well as specialized AI systems specifically trained on wound care datasets. Furthermore, to better approximate complex clinical decision-making, subsequent studies should move beyond isolated visual assessment by integrating complete patient history and clinical metadata alongside wound images; this would verify whether added context improves safety and therapeutic precision. It would also be valuable to increase the statistical robustness of these evaluations by expanding the sample size of lesions analyzed and comparing the AI outputs against multiple distinct panels of experts, to better account for variability in human clinical judgment. Another crucial aspect to explore is the longitudinal assessment of wound management. Monitoring the same lesion over time would allow researchers to verify how AI recommendations adapt to the physical evolution of the wound and whether the models can effectively guide the continuation of therapy, taking into account the outcomes of previously indicated dressings. Finally, looking towards a more distant horizon, prospective studies integrating these tools into real-world clinical workflows, such as community nursing, would be the ultimate test of their practical utility, although the implementation of such trials remains a complex challenge at this stage.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study provide compelling evidence regarding the reliability and clinical potential of Large Language Models in the field of wound care. ChatGPT and Gemini demonstrated a remarkable degree of concordance with the expert panel, exhibiting high sensitivity in the descriptive analysis of lesions and the recognition of critical “red flags,” such as signs of ischemia or infection. These tools can play a supportive role not only in clinical practice but also as potential adjuncts in medical education, for example, as an interactive training platform where students and residents can compare their descriptions and management plans with AI-generated outputs, although this educational role was not formally assessed in the present study.

Furthermore, the ability of these models to rapidly generate coherent management plans highlights their value as effective decision-support systems, particularly in non-specialist settings where they can facilitate the timely triage of complex patients. While instances of divergence regarding systemic treatments, such as in the case of abdominal dehiscence, indicate that visual analysis benefits significantly from the integration of clinical history, they do not diminish the utility of the instrument. Ultimately, LLMs represent a powerful asset for the modern plastic surgeon: they should remain an adjunct rather than a replacement for clinical judgment, and particular caution is needed when non-specialists rely on their suggestions, given the risks of over-reliance and automation bias. When used under professional supervision and within appropriate institutional and regulatory frameworks, they can offer a scalable, always-on resource that helps enhance diagnostic speed, standardize care, and support continuous medical training.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C. and G.M.; methodology, L.C., C.B. and G.M.; software, L.C. and I.S.; validation, L.C., G.M. and W.M.R.; formal analysis, L.C., G.M., C.B. and I.S.; investigation, L.C., G.M. and F.R.G.; data curation, L.C., R.C. and F.R.G.; writing—original draft preparation, L.C. and G.M.; writing—review and editing, I.S., W.M.R., C.B., R.C. and F.R.G.; visualization, L.C. and G.M.; hand-drawn illustrations, G.M. and C.B.; supervision, W.M.R. and R.C.; project administration, L.C. and G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it utilized exclusively fully anonymized images from a publicly accessible database (Medetec), and involved no prospective enrollment of human subjects.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the fact that the study utilized exclusively de-identified images from a third-party database (Medetec). The images do not contain identifiable personal data (such as faces), and permission for their use and publication was obtained directly from the database owner.

Data Availability Statement

No new data sere created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LLMs | Large Language Models |

| TIME | Tissue, Infection/Inflammation, Moisture balance, Edge |

| TIME CDST | TIME Clinical Decision Support Tool |

| TIME-H | TIME Health model |

| NPWT | Negative Pressure Wound Therapy |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| USD | United States Dollar |

References

- Swanson, T.; Ousey, K.; Haesler, E.; Bjarnsholt, T.; Carville, K.; Idensohn, P.; Kalan, L.; Keast, D.H.; Larsen, D.; Percival, S.; et al. IWII Wound Infection in Clinical Practice consensus document: 2022 update. J. Wound Care 2022, 31, S10–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivory, J.D.; Vellinga, A.; O’Gara, J.; Gethin, G. A scoping review protocol to identify clinical signs, symptoms and biomarkers indicative of biofilm presence in chronic wounds [version 2]. HRB Open Res. 2021, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, J.F.; Fuller, G.W.; Vowden, P. Cohort study evaluating the burden of wounds to the UK’s National Health Service in 2017/2018: Update from 2012/2013. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e045253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Janowska, A.; Dini, V.; Oranges, T.; Iannone, M.; Loggini, B.; Romanelli, M. Atypical Ulcers: Diagnosis and Management. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 2137–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frykberg, R.G.; Banks, J. Challenges in the Treatment of Chronic Wounds. Adv. Wound Care 2015, 4, 560–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martinengo, L.; Olsson, M.; Bajpai, R.; Soljak, M.; Upton, Z.; Schmidtchen, A.; Car, J.; Järbrink, K. Prevalence of chronic wounds in the general population: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann. Epidemiol. 2019, 29, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hongying, Z.; Chunmei, H.; Lijuan, C.; Miao, T.; Jingying, X.; Hongmei, J.; Jing, H.; Yang, H.; Min, Y. The current status and influencing factors of quality of life of chronic wound patients based on Wound-QoL scale: A cross-sectional study. Medicine 2025, 104, e42961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sen, C.K. Human Wound and Its Burden: Updated 2025 Compendium of Estimates. Adv. Wound Care 2025, 14, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallo, I.; Sivori, F.; Mastrofrancesco, A.; Abril, E.; Pontone, M.; Di Domenico, E.G.; Pimpinelli, F. Bacterial Biofilm in Chronic Wounds and Possible Therapeutic Approaches. Biology 2024, 13, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mayer, D.O.; Tettelbach, W.H.; Ciprandi, G.; Downie, F.; Hampton, J.; Hodgson, H.; Lazaro-Martinez, J.L.; Probst, A.; Schultz, G.; Stürmer, E.K.; et al. Best practice for wound debridement. J. Wound Care 2024, 33, S1–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Long, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. Biofilm therapy for chronic wounds. Int. Wound J. 2024, 21, e14667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beraja, G.E.; Gruzmark, F.; Pastar, I.; Lev-Tov, H. What’s New in Wound Healing: Treatment Advances and Microbial Insights. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2025, 26, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Falanga, V.; Isaacs, C.; Paquette, D.; Downing, G.; Kouttab, N.; Butmarc, J.; Badiavas, E.; Hardin-Young, J. Wounding of bioengineered skin: Cellular and molecular aspects after injury. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2002, 119, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, G.S.; Sibbald, R.G.; Falanga, V.; Ayello, E.A.; Dowsett, C.; Harding, K.; Romanelli, M.; Stacey, M.C.; Teot, L.; Vanscheidt, W. Wound bed preparation: A systematic approach to wound management. Wound Repair Regen. 2003, 11, S1–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, Z.; Dowsett, C.; Smith, G.; Atkin, L.; Bain, M.; Lahmann, N.A.; Schultz, G.S.; Swanson, T.; Vowden, P.; Weir, D.; et al. TIME CDST: An updated tool to address the current challenges in wound care. J. Wound Care 2019, 28, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarro, G.; Cozzani, F.; Rossini, M.; Bonati, E.; Del Rio, P. The modified TIME-H scoring system, a versatile tool in wound management practice: A preliminary report. Acta Biomed. 2021, 92, e2021226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nelson, S.; Lay, B.; Johnson, A.R., Jr. Artificial Intelligence in Skin and Wound Care: Enhancing Diagnosis and Treatment With Large Language Models. Adv. Ski. Wound Care 2025, 38, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Schellaert, W.; Martínez-Plumed, F.; Moros-Daval, Y.; Ferri, C.; Hernández-Orallo, J. Larger and more instructable language models become less reliable. Nature 2024, 634, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pressman, S.M.; Borna, S.; Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Haider, S.A.; Haider, C.R.; Forte, A.J. Clinical and Surgical Applications of Large Language Models: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lepp, H.; Ji, W.; Zhao, X.; Cao, H.; Liu, S.; He, S.; Huang, Z.; et al. Quantifying large language model usage in scientific papers. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2025, Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcaccini, G.; Corradini, L.; Shadid, O.; Seth, I.; Rozen, W.M.; Grimaldi, L.; Cuomo, R. From Prompts to Practice: Evaluating ChatGPT, Gemini, and Grok Against Plastic Surgeons in Local Flap Decision-Making. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sallam, M. ChatGPT Utility in Healthcare Education, Research, and Practice: Systematic Review on the Promising Perspectives and Valid Concerns. Healthcare 2023, 11, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Asgari, E.; Montaña-Brown, N.; Dubois, M.; Khalil, S.; Balloch, J.; Yeung, J.A.; Pimenta, D. A framework to assess clinical safety and hallucination rates of LLMs for medical text summarisation. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ji, Y.; Ma, W.; Sivarajkumar, S.; Zhang, H.; Sadhu, E.M.; Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Visweswaran, S.; Wang, Y. Mitigating the risk of health inequity exacerbated by large language models. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, J.S.; Baek, S.J.; Ryu, H.S.; Choo, J.M.; Cho, E.; Kwak, J.M.; Kim, J. Using large language models for clinical staging of colorectal cancer from imaging reports: A pilot study. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2025, 109, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zada, T.; Tam, N.; Barnard, F.; Van Sittert, M.; Bhat, V.; Rambhatla, S. Medical Misinformation in AI-Assisted Self-Diagnosis: Development of a Method (EvalPrompt) for Analyzing Large Language Models. JMIR Form. Res. 2025, 9, e66207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Seth, I.; Marcaccini, G.; Lim, B.; Novo, J.; Bacchi, S.; Cuomo, R.; Ross, R.J.; Rozen, W.M. The Temporal Evolution of Large Language Model Performance: A Comparative Analysis of Past and Current Outputs in Scientific and Medical Research. Informatics 2025, 12, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reifs Jiménez, D.; Casanova-Lozano, L.; Grau-Carrión, S.; Reig-Bolaño, R. Artificial Intelligence Methods for Diagnostic and Decision-Making Assistance in Chronic Wounds: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Syst. 2025, 49, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Salbas, A.; Buyuktoka, R.E. Performance of Large Language Models in Recognizing Brain MRI Sequences: A Comparative Analysis of ChatGPT-4o, Claude 4 Opus, and Gemini 2.5 Pro. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Sami, M.; Abdul Samad, M.; Parekh, K.; Suthar, P.P. Comparative Accuracy of ChatGPT 4.0 and Google Gemini in Answering Pediatric Radiology Text-Based Questions. Cureus 2024, 16, e70897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aljindan, F.K.; Shawosh, M.H.; Altamimi, L.; Arif, S.; Mortada, H. Utilization of ChatGPT-4 in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: A Narrative Review. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2023, 11, e5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Borna, S.; Pressman, S.M.; Haider, S.A.; Forte, A.J. Large Language Models for Intraoperative Decision Support in Plastic Surgery: A Comparison between ChatGPT-4 and Gemini. Medicina 2024, 60, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soenksen, L.R.; Kassis, T.; Conover, S.T.; Marti-Fuster, B.; Birkenfeld, J.S.; Tucker-Schwartz, J.; Naseem, A.; Stavert, R.R.; Kim, C.C.; Senna, M.M.; et al. Using deep learning for dermatologist-level detection of suspicious pigmented skin lesions from wide-field images. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabb3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneshjou, R.; Smith, M.P.; Sun, M.D.; Rotemberg, V.; Zou, J. Lack of Transparency and Potential Bias in Artificial Intelligence Data Sets and Algorithms: A Scoping Review. JAMA Dermatol. 2021, 157, 1362–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).