Abstract

Background: Noble gases, such as argon, have been observed to exhibit cytoprotective effects. The non-anesthetic properties, abundance, and cost-effectiveness of argon suggest its clinical potential. While its efficacy in mitigating ischemia–reperfusion injury has been demonstrated in cellular and small animal models, data on its effects in large animals remain limited. This study evaluated the effects of argon inhalation on pulmonary ischemia–reperfusion injury in miniature swine with potential applications in transplantation. Methods: The left bronchial and pulmonary artery and veins were clamped for 90 min, and then the clamps were released to induce lung ischemia–reperfusion injury in 10 CLAWN miniature swine. The argon group (n = 5) inhaled a mixture of 30% oxygen and 70% argon for 360 min, whereas the control group (n = 5) inhaled a mixture of 30% oxygen and 70% nitrogen for an equivalent duration. Lung function was evaluated using chest X-ray, lung biopsies, and blood gas analysis. Results: The PaO2/FiO2 ratio significantly decreased in the control group 2 h post-reperfusion (568 ± 12 to 272 ± 39 mmHg), but was better preserved in the argon group (562 ± 17 to 430 ± 48 mmHg). Blood gas from the left pulmonary vein showed a superior PvO2/FiO2 ratio in the argon group (331 ± 40 vs. 186 ± 17 mmHg at 2 h; 519 ± 19 vs. 292 ± 33 mmHg at 2 days). Chest X-ray revealed reduced infiltration in the left lung. The lung biopsy histological scores improved in the argon group at 2 h and 2 days. Serum superoxide dismutase analysis and tissue TUNEL assays suggested that antioxidant and anti-apoptotic mechanisms, respectively, were involved. Conclusions: Perioperative argon inhalation attenuates ischemia–reperfusion injury in swine lungs, likely via anti-apoptotic and antioxidant effects.

1. Introduction

Organ transplantation is widely recognized as an effective treatment for end-stage organ failure. However, the persistent shortage of donor organs remains a major obstacle [1]. According to the Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation, 172,409 solid organ transplants were performed worldwide in 2023, supported by 45,861 deceased organ donors, including those who donated after brain death and those who donated after circulatory death [2]. However, the demand for transplantation continues to exceed the available supply [3].

To expand the donor pool, organs from marginal donors, such as elderly individuals or those with hypertension or diabetes, are increasingly being utilized [4]. DCD donors are an important source of organs, in addition to conventional brain-dead and living donors. This approach has emerged as a viable strategy to expand the donor pool [5]. However, in DCD donors, the inevitable period of warm ischemia due to circulatory arrest markedly increases the risk of ischemia–reperfusion injury (IRI) [6,7]. IRI involves inflammation, oxidative stress, and tissue damage triggered by the temporary cessation and subsequent restoration of blood flow [8]. It contributes to primary graft dysfunction (PGD) and promotes immune activation, leading to graft rejection and chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) [9]. Despite extensive research, clinically applicable pharmacological strategies for mitigating IRI remain limited.

Given this unmet need, attention has turned to cytoprotective agents, including noble gases. Helium, argon (Ar), and xenon are chemically inert elements, known as noble gases, found in trace amounts in the atmosphere [10] and have been explored in industrial and medical contexts [11,12]. Among these, Ar is relatively abundant, non-anesthetic, and cost-effective, making it particularly attractive for potential therapeutic use. In contrast, helium is scarce and xenon is both expensive and anesthetic [13].

Experimental studies in small animal models have shown that the biological effects of Ar vary across organs. In the heart, Ar exposure reduces infarct size and improves post-ischemic recovery [14,15]. In the kidney, the use of Ar-saturated preservation solutions ameliorated IRI in a transplantation model [16]. In contrast, hepatic studies have yielded less favorable results; inhaled Ar did not protect against liver injury or enhance regeneration in partial hepatectomy or warm IRI models [17,18]. Large animal studies similarly demonstrate organ-dependent variability in the protective effects of Ar. Reported benefits include reduced neuronal death in porcine cerebral ischemia [19] and improved renal function in porcine kidney perfusion models [20], whereas no protective effect was observed in a porcine ex vivo lung perfusion model [21]. Taken together, these findings indicate that the organ-specific responses observed in small animal studies extend to large animal models, and the overall efficacy of Ar across organ systems remains uncertain. Notably, evidence supporting protective effects against pulmonary IRI in clinically relevant large animal settings is still very limited.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of perioperative Ar inhalation in a warm lung IRI model using CLAWN miniature swine. We examined pulmonary oxygenation, radiographic and histological injury, apoptosis, and oxidative stress markers to determine whether Ar inhalation can mitigate acute lung injury following IRI.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Ten CLAWN miniature swine (5–6 months old, 11.9–16.9 kg) were obtained from the Kagoshima Miniature Swine Research Center (Kagoshima, Japan). All procedures complied with the 3Rs principles (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement), emphasizing animal welfare and appropriate housing. To minimize the number of animals used, the study was carefully designed and approved by the Kagoshima University Animal Experiment Committee (Protocol no. MD20016). All handling and procedures followed the Kagoshima University Guidelines for Animal Experimentation, the internationally accepted standards (NIH Publication No. 86-23, revised 1985), and the ARRIVE guidelines (2020 revision).

2.2. Experimental Groups and Gas Inhalation Protocol

Animals were divided into two groups: an Ar inhalation group (Ar group, n = 5) and a control group (n = 5). In the Ar group, a gas mixture containing 70% Ar and 30% O2 was used, whereas the control group received a gas mixture of 70% nitrogen and 30% O2. The concentration of 70% Ar was selected as the highest dose that could be safely administered while maintaining an FiO2 value of 0.30. Gas inhalation was maintained for 360 min to cover the entire peri-reperfusion period, starting from the beginning of the operation and continuing until 2 h post-reperfusion in both groups, based on our previous porcine lung IRI model [22].

2.3. Surgical Procedure

Anesthesia was induced by intramuscular injection of ketamine, midazolam, and medetomidine, followed by tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation (100% O2, 12–15 mL/kg, 12–15 breaths/min). Anesthesia was maintained with 1–3% isoflurane. Catheters were inserted into the internal carotid artery (for blood pressure monitoring and gas analysis) and the external jugular vein (for sampling). The ventilator gas mixture was switched to the designated gas mixtures for each group.

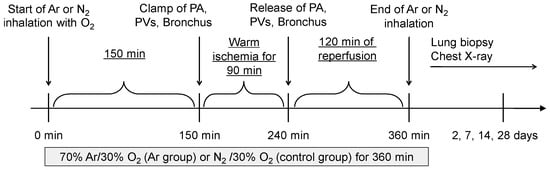

The lung IRI model was established as previously described [22]. Briefly, left fifth intercostal thoracotomy was performed to expose the pulmonary hilum. Then, 150 min after starting gas inhalation, the left pulmonary artery, veins, and main bronchus were clamped for 90 min and released to initiate reperfusion and establish a warm IRI model (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the experimental protocol. Argon (70% Ar/30% O2) or control gas (70% N2/30% O2) inhalation was initiated at the beginning of the operation and maintained for a total of 360 min. At 150 min, the left pulmonary artery (PA), pulmonary veins (PVs), and main bronchus were clamped for 90 min to induce warm ischemia. Reperfusion was started at 240 min by releasing the clamps, followed by a 2 h reperfusion period. Gas inhalation was terminated at 360 min. Lung biopsy and chest radiography were performed 2, 7, 14, and 28 days post-reperfusion.

2.4. Blood Gas Measurements

To evaluate pulmonary function, arterial blood samples were collected from the carotid artery before surgery and 2 h post-reperfusion. Pulmonary venous blood was sampled from the left pulmonary vein 2 h and 2 days post-reperfusion. Blood gas analysis was performed using a blood gas analyzer (IL Japan, Tokyo, Japan).

The left pulmonary vein was selected because it drains blood directly from the reperfused left lung, providing an accurate reflection of the local oxygen exchange without dilution by the contralateral lung. Therefore, the pulmonary venous oxygenation index (PvO2/FiO2 ratio, abbreviated as Pv/F ratio) was calculated to assess regional lung oxygenation.

2.5. Chest X-Ray

Chest X-rays were obtained under general anesthesia on days 2, 7, 14, and 28 post-reperfusion to monitor lung injury.

2.6. Histological Evaluation

Lung tissue samples were collected at 2 h and on days 2, 7, 14, and 28 post-reperfusion, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and embedded in paraffin. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Elastica Masson–Goldner (EMG) for histopathological assessments. Histological injury was assessed using the semiquantitative scoring system previously reported [22], which was adapted from the criteria described by Müller et al. [23]. Briefly, cell infiltration, intra-alveolar edema, fibrin exudation, and hemorrhage were each graded from 0 (normal) to 3 (severe). Apoptotic cells were detected using the Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated UTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay. All histological assessment was conducted by a renal pathologist who was blinded to group allocation (A.S.).

2.7. Renal and Hepatic Function

To assess organ function, the serum creatinine (Cre) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were measured at baseline (pre-ischemia) and on days 2, 7, 14, and 28 post-reperfusion.

2.8. Inflammatory and Oxidative Markers

To evaluate systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, serum levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were measured. Blood was collected from the jugular vein before ischemia and 1, 2, and 6 h post-reperfusion for analysis. Measurements were conducted using ELISA kits (IL-6: R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA; SOD: Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). For quantitative assessment of apoptosis, TUNEL-positive nuclei in lung sections obtained 2 days post-reperfusion were counted in randomly selected high-power fields (400×). The mean number of TUNEL-positive cells per field was calculated for statistical comparison between groups.

2.9. Gene Expression Analysis

To evaluate the gene expression levels of Caspase-3 (apoptosis-related) and IL-6 (inflammatory cytokine), lung biopsy samples were collected 2 h and 2 days post-reperfusion. Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Midi Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit with DNA Eraser (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan). Quantitative PCR was conducted using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara Bio), and amplification was performed with a Thermal Cycler Dice Real-Time System II (Takara Bio). Ribosomal protein L4 (RPL4) was used as the reference gene for relative quantification and analyzed using Multiplate RQ software Ver 6.0.1 (Takara Bio). The relative expression levels were normalized to RPL4 and expressed as fold-changes relative to pre-ischemia values. The primer and probe sequences are as follows: Caspase-3 sense primer, 5′-AAGTTTCTTCAGAGGGGACTGC-3′; antisense primer, 5′-ACTGCTACCTTTCGGTTAACCC-3′; IL-6 sense primer, 5′-AAGCACTGATCCAGACCCTGAG-3′; antisense primer, 5′-TCAGGTGCCCCAGCTACATTAT-3′; RPL4 sense primer, 5′-TTTGTGGTAGGCTATGCCCTTG-3′; and antisense primer, 5′-CAATGGGACTCCAGATGTTTCC-3′.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Comparisons between the two groups at each time point were performed using an unpaired Student’s t-test. For within-group comparisons between baseline and post-reperfusion values, a paired t-test was used, and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Argon Inhalation Preserves Systemic and Pulmonary Oxygenation After Lung IRI

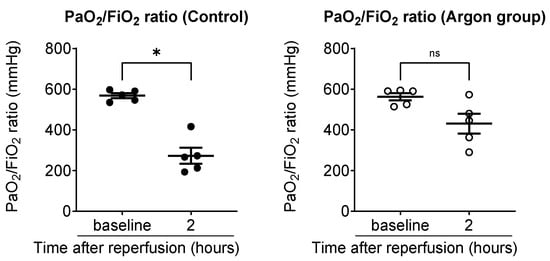

To evaluate systemic oxygenation, arterial blood gas analysis was performed using samples collected from the carotid artery, and the P/F ratio was calculated. In the control group, the P/F ratio significantly declined from 568 ± 12 mmHg pre-ischemia to 272 ± 39 mmHg 2 h post-reperfusion (p < 0.05). In contrast, the Ar group showed a smaller, non-significant decrease from 562 ± 17 to 430 ± 48 mmHg (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of arterial oxygenation between the control and argon (Ar) groups (black dots: control; white circles: Ar group). Arterial blood samples were collected from the carotid artery and the PaO2/FiO2 (P/F) ratio was calculated to assess systemic oxygenation. In the control group, the P/F ratio significantly declined from baseline to 2 h post-reperfusion, whereas the Ar group exhibited a smaller, non-significant decrease. Data are presented as individual values with the mean ± SEM. * p less than 0.05. ns: not significant.

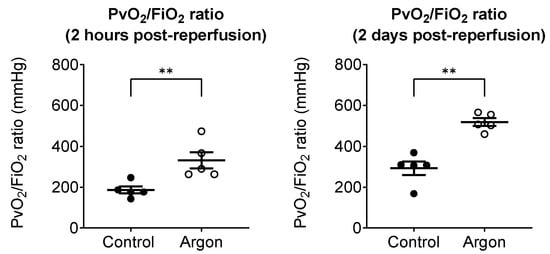

To evaluate the oxygenation of the reperfused left lung, we used the pulmonary venous oxygenation index (Pv/F ratio), as described in the Methods Section. Two hours post-reperfusion, the Pv/F ratio was significantly higher in the Ar group (331 ± 40 mmHg) than in the control group (186 ± 17 mmHg; p < 0.01). A similar trend was observed 2 days post-reperfusion, with Pv/F ratios of 519 ± 19 mmHg in the Ar group and 292 ± 33 mmHg in the control group (p < 0.01), indicating near-complete recovery of oxygenation in the Ar group (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Pulmonary venous oxygenation of the reperfused left lung was assessed using the PvO2/FiO2 (Pv/F) ratio, obtained from blood sampled from the left pulmonary vein. Two hours post-reperfusion, the argon group showed significantly higher Pv/F ratios than the control group (black dots: control; white circles: Ar group). Two days post-reperfusion, the argon group maintained superior oxygenation with near-complete recovery, whereas the control group exhibited persistently impaired values. Data are presented as individual values with the mean ± SEM. ** p less than 0.01.

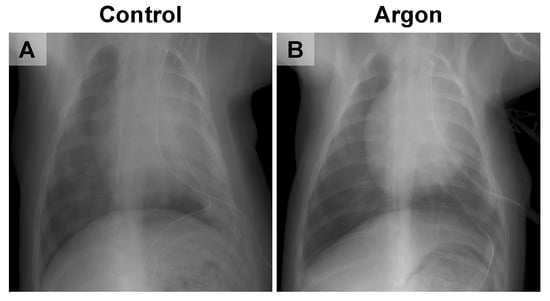

3.2. Argon Inhalation Reduces Pulmonary Infiltrates After IRI

Chest X-rays performed two days post-reperfusion revealed marked pulmonary infiltrates and reduced lung expansion in the control group. In contrast, the Ar group exhibited preserved lung expansion and only minimal infiltration (Figure 4). By day 7, both groups showed signs of recovery and no notable differences were observed. Findings on days 14 and 28 also demonstrated complete radiographic recovery in both groups.

Figure 4.

Representative chest X-ray images from the control (A) and argon (Ar) groups (B). The control group showed marked pulmonary infiltration and reduced lung expansion, whereas the Ar group exhibited preserved lung expansion with only minimal infiltration.

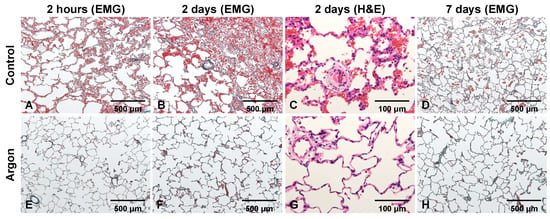

3.3. Argon Inhalation Reduces Histopathological Lung Injury

Histopathological analysis of lung biopsy specimens obtained 2 h post-reperfusion in the control group revealed neutrophil infiltration, alveolar edema, hemorrhage, and fibrin deposition (Figure 5A). These changes worsened by day 2, with pronounced edema, hemorrhage, and neutrophil infiltration in alveolar capillaries and pulmonary arterioles (Figure 5B,C). By day 7, fibrin deposition persisted because of alveolar wall damage (Figure 5D). In contrast, the Ar group showed nearly normal histology at 2 h (Figure 5E), with only mild edema and limited cellular infiltration on day 2 (Figure 5F,G). By day 7, most abnormalities had resolved, with minimal residual fibrin (Figure 5H). Findings on days 14 and 28 likewise showed near-complete histological recovery in both groups; therefore, images from these time points are not presented. The histological scores of the lung biopsies are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 5.

Representative lung sections from the control and argon (Ar) groups 2 h, 2 days, and 7 days post-reperfusion. In the control group (A–D), EMG and H&E staining showed early neutrophil infiltration, edema, hemorrhage, and fibrin deposition, which became more pronounced on day 2. By day 7, the residual fibrin and alveolar wall injuries persisted. In contrast, the Ar group (E–H) displayed nearly preserved architecture at 2 h, with only mild edema and limited cellular infiltration on day 2, and substantial resolution of abnormalities by day 7. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Elastica Masson–Goldner (EMG).

Table 1.

Histological scores of lung biopsies based on light microscopy.

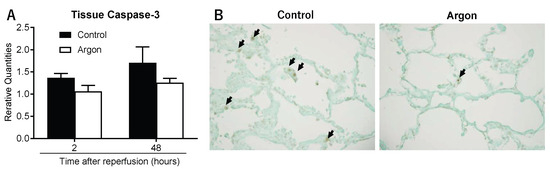

3.4. Argon Inhalation Suppresses Apoptosis in Ischemic Lung Tissue

Caspase-3 mRNA expression was measured to examine apoptosis in tissues. In the control group, expression increased to 1.37 ± 0.10 at 2 h and 1.70 ± 0.36 two days post-reperfusion. Although increases were observed in the Ar group, they were less pronounced (Figure 6A). TUNEL staining at 2 days post-reperfusion indicated a significant reduction in TUNEL-positive cells in the Ar group (Figure 6B). To confirm this finding, we quantified the TUNEL-positive nuclei in the lung tissue 2 days post-reperfusion. The number of apoptotic cells per high-power field (400×) was markedly lower in the Ar group than in the control group (1.7 ± 0.3 vs. 6.6 ± 0.6 cells per field, respectively; p < 0.01), providing quantitative support for the anti-apoptotic effect of Ar in this model.

Figure 6.

(A) Caspase-3 mRNA expression 2 h and 2 days post-reperfusion. Both groups showed increased expression, but the increase was less pronounced in the argon (Ar) group. (B) Representative TUNEL staining 2 days post-reperfusion. The number of apoptotic cells (arrows) per high-power field (400×) was markedly lower in the Ar group than in the control group (1.7 ± 0.3 vs. 6.6 ± 0.6 cells per field, respectively; p < 0.01).

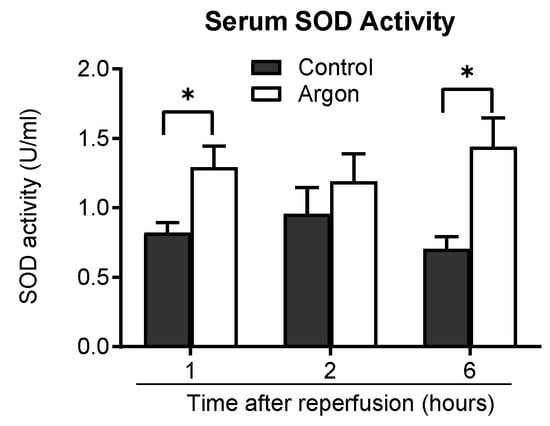

3.5. Argon Inhalation Enhances Antioxidant Response

Serum superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was measured to assess the antioxidant effects. The Ar group consistently exhibited higher SOD activity than the control group 1, 2, and 6 h post-reperfusion, with significant differences at 1 and 6 h (p < 0.05), supporting the antioxidant role of Ar (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Serum superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was measured 1, 2, and 6 h post-reperfusion in the control and argon (Ar) groups. The Ar group exhibited consistently higher SOD activity than the control group at all time points, with statistically significant increases at z1 and 6 h post-reperfusion (* p less than 0.05). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

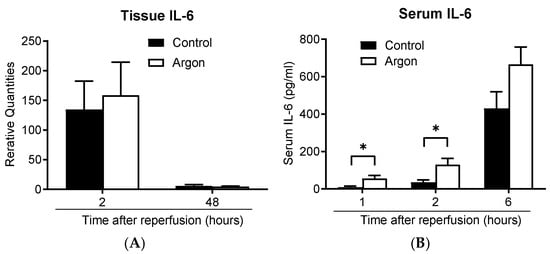

3.6. Argon Inhalation Shows Limited Anti-Inflammatory Effects

IL-6 mRNA expression in lung tissue increased in both groups 2 h post-reperfusion and decreased by day 2 (Figure 8A). Serum IL-6 concentrations also increased over time in both groups (Figure 8B). Interestingly, IL-6 levels were significantly lower in the control group than in the Ar group 1 and 2 h post-reperfusion. These findings suggest that Ar inhalation did not exert an anti-inflammatory effect under these conditions.

Figure 8.

IL-6 mRNA expression in the lung tissue increased 2 h post-reperfusion and declined by 48 h in both groups (A). The serum IL-6 concentration increased over time in both groups (B). IL-6 levels were significantly lower in the control group than in the argon group 1 and 2 h post-reperfusion (* p less than 0.05). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

3.7. Argon Inhalation Causes No Detectable Adverse Effects

To evaluate the potential systemic toxicity of prolonged Ar inhalation (360 min total), the serum Cre and ALT levels were monitored. No significant differences were found between the two groups throughout the study period, and no adverse effects were observed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in kidney and liver function.

4. Discussion

In this clinically relevant swine model of warm lung IRI, perioperative inhalation of a 70% Ar and 30% O2 mixture markedly attenuated acute lung injury and preserved pulmonary function. Ar-treated animals exhibited improved systemic oxygenation, significantly higher Pv/F ratios reflecting regional gas exchange, and reduced radiographic and histological injuries. These protective effects were supported by decreased apoptosis and enhanced antioxidant responses. Collectively, these findings suggest that Ar exerts potent cytoprotective actions during the reperfusion phase, which represents a major unmet target in current lung transplantation management.

Warm ischemia rapidly depletes ATP, leading to hypoxanthine accumulation. Upon reperfusion, xanthine oxidase converts hypoxanthine into superoxide, causing a substantial oxidative burst and disruption of the alveolar–capillary barrier [8]. This process drives PGD and contributes to CLAD [9]. Pharmacological approaches to mitigate IRI remain limited.

Medical gases have gained attention because inhalation enables targeted delivery to the alveolar–capillary interface with minimal systemic toxicity [24]. Noble gases, previously regarded as inert, have demonstrated organ-protective effects, including anti-apoptotic and antioxidant actions [25]. Argon has shown protective efficacy across multiple organs, including improved outcomes in cerebral IRI [26,27,28], attenuated myocardial infarction with intermittent 70% Ar [14], reduced renal IRI with Ar-saturated perfusate [16], and decreased neuronal injury in large-animal cerebral ischemia models [27]. Porcine kidney perfusion studies have demonstrated protective effects [20].

Previous experimental findings in the lung have predominantly reported a lack of benefit. Martens et al. found no protective effect of Ar in porcine EVLP despite high Ar exposure [21,29]. This discrepancy likely reflects fundamental differences between EVLP and in vivo conditions, particularly regarding oxygen concentration, reperfusion timing, and the presence of intact vascular and inflammatory responses. Our results suggest that the protective effects of Ar become apparent only when these physiological components are preserved, as in the in vivo setting.

Multiple strategies exist for mitigating IRI, including donor selection [30], preservation solutions [31], and pharmacological interventions [32]. EVLP is particularly effective for reconditioning marginal donor lungs [33,34,35]; reducing cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8; and decreasing DAMP release. However, EVLP acts exclusively during the pre-transplant phase and does not address the reperfusion injury occurring in the recipient. In contrast, Ar can be administered during EVLP and the reperfusion period, precisely when oxidative burst, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis peak, making it a complementary perioperative adjunct rather than a replacement for EVLP.

The known cytoprotective actions of Ar include both anti-apoptotic and antioxidant mechanisms, and our findings align well with these previously described pathways. Ar has been shown to suppress caspase-3 activation [27], reduce TLR2/4 expression [36], and activate ERK1/2 [28]. Additional studies have demonstrated M2 macrophage polarization [37], SAPK/JNK inhibition and HMGB1 release [15,38], and downregulation of IL-8, which attenuates early neutrophil recruitment [39,40]. Ar may further enhance antioxidant defenses through PI3K–ERK1/2–mTOR signaling and Nrf2-dependent gene induction, including NQO1 and SOD-1 [41]. In this context, the consistently higher SOD levels observed in the Ar group provide experimental support for enhanced antioxidative activity during early reperfusion. As epithelial and endothelial apoptosis drive early lung IRI, the modulation of these pathways offers a mechanistic explanation for the preserved alveolar–capillary integrity and improved Pv/F ratios observed in our study.

In contrast to its anti-apoptotic and antioxidant actions, Ar inhalation did not reduce IL-6 levels; early systemic IL-6 levels were transiently higher in the Ar group. This suggests that the protective effects of Ar in this model predominantly involve antioxidant and anti-apoptotic mechanisms rather than the broad suppression of inflammatory cytokines. The transient rise in IL-6 is consistent with reports that Ar can evoke mild TLR2/4-dependent signaling despite an overall cytoprotective profile [39]. Thus, early cytokine elevation may reflect context-dependent stress signaling rather than harmful inflammation.

Although early systemic IL-6 levels were transiently higher in the Ar group, lung tissue IL-6 mRNA expression did not differ between groups, suggesting that this difference reflects a systemic rather than a lung-restricted response. Importantly, Argon’s protective effects—improved oxygenation, reduced apoptosis, and enhanced antioxidant activity—were preserved despite this cytokine pattern, indicating that its benefits in warm lung IRI are mediated predominantly through anti-apoptotic and antioxidant pathways. Prior reports describing the anti-inflammatory effects of argon were conducted in retinal [36] or neuronal models [40] with localized and barrier-restricted inflammation, whereas the present large-animal lung IRI model evokes a broader systemic inflammatory activation. These organ- and model-dependent differences likely explain the distinct IL-6 kinetics observed in our study.

Argon’s protective effects have been reported to be dose- and time-dependent. In a cardiac arrest model, 70% Ar provided greater neuroprotection than 40% [42]. Similarly, 25–75% Ar showed time- and dose-dependent retinal protection [43], and proper timing and duration were crucial for neuroprotection in a transient middle cerebral artery occlusion mouse model [44]. These findings suggest that optimizing the Ar concentration and exposure remains important for translation.

In this study, we selected 70% Ar because it represents the highest concentration that can be safely administered while maintaining an FiO2 of 0.30. The 360-min inhalation period was chosen to cover the entire peri-reperfusion window and was based on our previous large-animal experiments in which 360 min of carbon monoxide (CO) inhalation effectively attenuated lung IRI [22]. Because the oxidative burst that initiates early reperfusion injury peaks within the first minutes to hours after reperfusion [8,9], continuous exposure throughout this window is considered important. In the present study, antioxidant and anti-apoptotic effects were evident at both 2 h and 2 days after reperfusion, supporting the adequacy of this exposure duration for suppressing ROS-mediated injury. Nevertheless, the optimal combination of Ar concentration and treatment duration remains unknown, and future studies will explore alternative dosing regimens.

A major strength of this study is the use of a clinically relevant large-animal model with a 28-day follow-up, whereas many prior Ar studies assessed only the early time points. Normoxic administration enhances its feasibility. The chemical inertness of Ar provides advantages over gases such as nitric oxide, CO, hydrogen, and hydrogen sulfide, which require strict safety management [45,46,47,48,49]. Ar is non-toxic, non-flammable, and simple to administer, making it suitable for perioperative use and potentially compatible with EVLP circuits. Synergistic combinations with other medical gases have also been explored [50].

This study has some limitations. Cold preservation has not been evaluated [51], although standard graft preservation relies on cold storage with dextran-based solutions and oxygenated cooling [52,53]. Warm and cold IRI differ markedly in inflammatory patterns and metabolic suppression [54,55]; thus, the effects of Ar under cold storage conditions warrant further investigation. Moreover, although early (2 h) and later (48 h) apoptotic changes were assessed, intermediate time points might also provide additional detail regarding the temporal progression of apoptosis. Other limitations include the modest sample size, the assessment of only one Ar concentration and exposure duration, and the absence of transcriptomic or long-term CLAD-like analyses.

5. Conclusions

Perioperative Ar inhalation significantly attenuated warm lung IRI in miniature swine by reducing apoptosis, enhancing antioxidant responses, and preserving pulmonary oxygenation. By targeting the reperfusion phase, which is unaddressed by donor-side strategies such as EVLP, Ar may represent a practical and safe adjunct for lung transplantation. Further mechanistic and translational studies, including validation in large-animal transplantation models, are warranted to determine optimal dosing and timing, which will allow for integration into clinical practice. Such efforts may facilitate the development of strategies to improve graft quality and ultimately expand the pool of transplantable organs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.I., M.O. and H.S.; methodology, T.I., M.O., Y.A., K.T., A.K., M.S. and H.S.; investigation, T.I., A.S., Y.I. and H.S.; formal analysis, T.I. and Y.I.; data curation, T.I., Y.A., K.T., Y.I. and A.S.; writing—original draft, T.I.; writing—review and editing, M.O. and H.S.; visualization, T.I. and A.S.; supervision, M.O. and H.S.; project administration, T.I. and H.S.; funding acquisition, T.I. and H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI, Grant Number 20K09169.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Animal care, housing, and surgery were performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the Committee for Animal Research of Kagoshima University, Japan. All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Kagoshima University (approval number: MD20016; 19 May 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

A blank informed consent form was waived because the study does not involve human participants.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries should be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Akiyuki Iwamoto, Daiki Takei and Kenya Shimizu for their assistance with the experiments. The authors thank all staff members of the Division of Experimental Laboratory Animal Resources and Research, Center for Advanced Science Research and Promotion, Kagoshima University, who provided animal care.

Conflicts of Interest

M.O. received a lecture fee from Astellas Pharma Inc. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Ar | Argon |

| DCD | Donation after circulatory death |

| IRI | Ischemia–reperfusion injury |

| PGD | Primary graft dysfunction |

| CLAD | Chronic lung allograft dysfunction |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| EMG | Elastica Masson–Goldner |

| TUNEL | Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated UTP-biotin nick end labeling |

| Cre | Creatinine |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| cDNA | Complementary DNA |

| RPL4 | Ribosomal protein L4 |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| P/F ratio | PaO2/FiO2 ratio |

| Pv/F ratio | PvO2/FiO2 ratio |

| EVLP | Ex vivo lung perfusion |

| HMGB1 | High-mobility group box-1 |

| CO | Carbon monoxide |

References

- Chen-Yoshikawa, T.F.; Fukui, T.; Nakamura, S.; Ito, T.; Kadomatsu, Y.; Tsubouchi, H.; Ueno, H.; Sugiyama, T.; Goto, M.; Mori, S.; et al. Current trends in thoracic surgery. Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 2020, 82, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation. Available online: https://www.transplant-observatory.org/ (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Wadowski, B.; Chang, S.H.; Carillo, J.; Angel, L.; Kon, Z.N. Assessing donor organ quality according to recipient characteristics in lung transplantation. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2023, 165, 532–543.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, D.; Wang, Y.; Shiiya, H.; Sun, C.B.; Uemura, Y.; Sato, M.; Nakajima, J. Outcomes of marginal donors for lung transplantation after ex vivo lung perfusion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 159, 720–730.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawitz, O.K.; Raman, V.; DeVore, A.D.; Mentz, R.J.; Patel, C.B.; Rogers, J.; Milano, C. Increasing the United States heart transplant donor pool with donation after circulatory death. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 159, e307–e309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, B.F.; de la Morena, M.; Sweet, S.C.; Trulock, E.P.; Guthrie, T.J.; Mendeloff, E.N.; Huddleston, C.; Cooper, J.D.; Patterson, G.A. Primary graft dysfunction and other selected complications of lung transplantation: A single-center experience of 983 patients. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005, 129, 1421–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altun, G.T.; Arslantas, M.K.; Cinel, I. Primary Graft Dysfunction after Lung Transplantation. Turk. J. Anaesthesiol. Reanim. 2015, 43, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeris, T.; Baines, C.P.; Krenz, M.; Korthuis, R.J. Cell biology of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 298, 229–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Yoshikawa, T.F. Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Lung Transplantation. Cells 2021, 10, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christe, K.O. A Renaissance in Noble Gas Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2001, 40, 1419–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollig, A.; Coburn, M. Noble gases and neuroprotection: Summary of current evidence. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2021, 34, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoderick, G.C.; Kelley, M.E.; Gameson, L.; Harris, K.J.; Hodges, J.T. Issues with analyzing noble gases using gas chromatography with thermal conductivity detection. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018, 410, 6247–6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, H.N.; Haelewyn, B.; Chazalviel, L.; Lecocq, M.; Degoulet, M.; Risso, J.J.; Abraini, J.H. Post-ischemic helium provides neuroprotection in rats subjected to middle cerebral artery occlusion-induced ischemia by producing hypothermia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2009, 29, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemoine, S.; Blanchart, K.; Souplis, M.; Lemaitre, A.; Legallois, D.; Coulbault, L.; Simard, C.; Allouche, S.; Abraini, J.H.; Hanouz, J.L.; et al. Argon Exposure Induces Postconditioning in Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 22, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiss, A.; Shu, H.; Hamza, O.; Santer, D.; Tretter, E.V.; Yao, S.; Markstaller, K.; Hallstrom, S.; Podesser, B.K.; Klein, K.U. Argon preconditioning enhances postischaemic cardiac functional recovery following cardioplegic arrest and global cold ischaemia. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2018, 54, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, Y.; Pype, J.L.; Martin, A.R.; Chong, C.F.; Daniel, L.; Gaudart, J.; Ibrahim, Z.; Magalon, G.; Lemaire, M.; Hardwigsen, J. Noble gas (argon and xenon)-saturated cold storage solutions reduce ischemia-reperfusion injury in a rat model of renal transplantation. Nephron Extra 2011, 1, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmer, T.F.; Fragoulis, A.; Dohmeier, H.; Kroh, A.; Andert, A.; Stoppe, C.; Alizai, H.; Klink, C.; Coburn, M.; Neumann, U.P. Argon Delays Initiation of Liver Regeneration after Partial Hepatectomy in Rats. Eur. Surg. Res. 2017, 58, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, S.M.; Dohmeier, H.; Stoppe, C.; Alizai, P.H.; Schipper, S.; Neumann, U.P.; Coburn, M.; Ulmer, T.F. Inhaled Argon Impedes Hepatic Regeneration after Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broad, K.D.; Fierens, I.; Fleiss, B.; Rocha-Ferreira, E.; Ezzati, M.; Hassell, J.; Alonso-Alconada, D.; Bainbridge, A.; Kawano, G.; Ma, D.; et al. Inhaled 45–50% argon augments hypothermic brain protection in a piglet model of perinatal asphyxia. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016, 87, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, A.; Bruzzese, L.; Steinberg, J.G.; Jammes, Y.; Torrents, J.; Berdah, S.V.; Garnier, E.; Legris, T.; Loundou, A.; Chalopin, M.; et al. Effectiveness of pure argon for renal transplant preservation in a preclinical pig model of heterotopic autotransplantation. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, A.; Ordies, S.; Vanaudenaerde, B.M.; Verleden, S.E.; Vos, R.; Verleden, G.M.; Verbeken, E.K.; Van Raemdonck, D.E.; Claes, S.; Schols, D.; et al. A porcine ex vivo lung perfusion model with maximal argon exposure to attenuate ischemia-reperfusion injury. Med. Gas Res. 2017, 7, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahara, H.; Shimizu, A.; Setoyama, K.; Okumi, M.; Oku, M.; Samelson-Jones, E.; Yamada, K. Carbon monoxide reduces pulmonary ischemia-reperfusion injury in miniature swine. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2010, 139, 1594–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, C.; Hoffmann, H.; Bittmann, I.; Isselhard, W.; Messmer, K.; Dienemann, H.; Schildberg, F.W. Hypothermic storage alone in lung preservation for transplantation: A metabolic, light microscopic, and functional analysis after 18 hours of preservation. Transplantation 1997, 63, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapol, W.M.; Charles, H.C.; Martin, A.R.; Sa, R.C.; Yu, B.; Ichinose, F.; MacIntyre, N.; Mammarappallil, J.; Moon, R.; Chen, J.Z.; et al. Pulmonary Delivery of Therapeutic and Diagnostic Gases. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv. 2018, 31, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martusevich, A.; Surovegina, A.; Popovicheva, A.; Didenko, N.; Artamonov, M.; Nazarov, V. Some Beneficial Effects of Inert Gases on Blood Oxidative Metabolism: In Vivo Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 5857979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Zhang, J.; Shang, Y.; Yuan, S.; Meng, C. Argon inhibits reactive oxygen species oxidative stress via the miR-21-mediated PDCD4/PTEN pathway to prevent myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 5529–5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Mitchell, S.; Ciechanowicz, S.; Savage, S.; Wang, T.; Ji, X.; Ma, D. Argon protects against hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in neonatal rats through activation of nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 25640–25651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, F.; Kaufmann, K.B.; Coburn, M.; Lagreze, W.A.; Roesslein, M.; Biermann, J.; Buerkle, H.; Loop, T.; Goebel, U. Neuroprotective effects of Argon are mediated via an ERK-1/2 dependent regulation of heme-oxygenase-1 in retinal ganglion cells. J. Neurochem. 2015, 134, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, A.; Montoli, M.; Faggi, G.; Katz, I.; Pype, J.; Vanaudenaerde, B.M.; Van Raemdonck, D.E.; Neyrinck, A.P. Argon and xenon ventilation during prolonged ex vivo lung perfusion. J. Surg. Res. 2016, 201, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, S.; Barten, M.J.; Topf, C.; Garbade, J.; Dhein, S.; Mohr, F.W.; Bittner, H.B. Donor type impact on ischemia-reperfusion injury after lung transplantation. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2012, 93, 913–919; discussion 919–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Chen, L.; Eguchi, S.; Alam, A.; Cahilog, Z.; Sun, Q.; Wu, L.; et al. Tackling regulated cell death yields enhanced protection in lung grafts. Theranostics 2023, 13, 4376–4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zuurbier, C.J.; Huhn, R.; Torregroza, C.; Hollmann, M.W.; Preckel, B.; van den Brom, C.E.; Weber, N.C. Pharmacological Cardioprotection against Ischemia Reperfusion Injury-The Search for a Clinical Effective Therapy. Cells 2023, 12, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cypel, M.; Keshavjee, S. The clinical potential of ex vivo lung perfusion. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2012, 6, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, J.C.; Zamel, R.; Klement, W.; Bai, X.H.; Machuca, T.N.; Waddell, T.K.; Liu, M.; Cypel, M.; Keshavjee, S. Towards donor lung recovery-gene expression changes during ex vivo lung perfusion of human lungs. Am. J. Transplant. 2018, 18, 1518–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, J.P.; Ball, A.L.; Crichley, W.; Yonan, N.; Liao, Q.; Sjoberg, T.; Steen, S.; Fildes, J.E. Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion Improves the Inflammatory Signaling Profile of the Porcine Donor Lung Following Transplantation. Transplantation 2020, 104, 1899–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, U.; Scheid, S.; Spassov, S.; Schallner, N.; Wollborn, J.; Buerkle, H.; Ulbrich, F. Argon reduces microglial activation and inflammatory cytokine expression in retinal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Neural Regen. Res. 2021, 16, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Qi, M.; She, T.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Xu, L.; Peng, B.; Liu, J.; et al. Argon mitigates post-stroke neuroinflammation by regulating M1/M2 polarization and inhibiting NF-kappaB/NLRP3 inflammasome signaling. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 14, mjac077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Roux, Q.; Lidouren, F.; Kudela, A.; Slassi, L.; Kohlhauer, M.; Boissady, E.; Chalopin, M.; Farjot, G.; Billoet, C.; Bruneval, P.; et al. Argon Attenuates Multiorgan Failure in Relation with HMGB1 Inhibition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheid, S.; Lejarre, A.; Wollborn, J.; Buerkle, H.; Goebel, U.; Ulbrich, F. Argon preconditioning protects neuronal cells with a Toll-like receptor-mediated effect. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, F.; Lerach, T.; Biermann, J.; Kaufmann, K.B.; Lagreze, W.A.; Buerkle, H.; Loop, T.; Goebel, U. Argon mediates protection by interleukin-8 suppression via a TLR2/TLR4/STAT3/NF-kappaB pathway in a model of apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells in vitro and following ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat retina in vivo. J. Neurochem. 2016, 138, 859–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, F.; Goebel, U. The Molecular Pathway of Argon-Mediated Neuroprotection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucken, A.; Kurnaz, P.; Bleilevens, C.; Derwall, M.; Weis, J.; Nolte, K.; Rossaint, R.; Fries, M. Dose dependent neuroprotection of the noble gas argon after cardiac arrest in rats is not mediated by K(ATP)-channel opening. Resuscitation 2014, 85, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulbrich, F.; Schallner, N.; Coburn, M.; Loop, T.; Lagreze, W.A.; Biermann, J.; Goebel, U. Argon inhalation attenuates retinal apoptosis after ischemia/reperfusion injury in a time- and dose-dependent manner in rats. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Xue, K.; Liu, J.; Gu, J.H.; Peng, B.; Xu, L.; Wang, G.; Jiang, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Timely and Appropriate Administration of Inhaled Argon Provides Better Outcomes for tMCAO Mice: A Controlled, Randomized, and Double-Blind Animal Study. Neurocrit. Care 2022, 37, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancock, J.T. Are Protein Cavities and Pockets Commonly Used by Redox Active Signalling Molecules? Plants 2023, 12, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.X.; Zhu, H.W.; Chen, X.; Wei, J.L.; Zhang, X.F.; Xu, M.Y. Inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibition reverses pulmonary arterial dysfunction in lung transplantation. Inflamm. Res. 2014, 63, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Takeuchi, K.; Ariyoshi, Y.; Kondo, A.; Iwanaga, T.; Ichinari, Y.; Iwamoto, A.; Shimizu, K.; Miura, K.; Miura, S.; et al. Carbon Monoxide as a Molecular Modulator of Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury: New Insights for Translational Application in Organ Transplantation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsawa, I.; Ishikawa, M.; Takahashi, K.; Watanabe, M.; Nishimaki, K.; Yamagata, K.; Katsura, K.; Katayama, Y.; Asoh, S.; Ohta, S. Hydrogen acts as a therapeutic antioxidant by selectively reducing cytotoxic oxygen radicals. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekijima, M.; Sahara, H.; Miki, K.; Villani, V.; Ariyoshi, Y.; Iwanaga, T.; Tomita, Y.; Yamada, K. Hydrogen sulfide prevents renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in CLAWN miniature swine. J. Surg. Res. 2017, 219, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, T.; Hayashi, T.; Inamoto, T.; Kato, R.; Ibuki, N.; Takahara, K.; Takai, T.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Uchimoto, T.; Saito, K.; et al. Dual Gas Treatment With Hydrogen and Carbon Monoxide Attenuates Oxidative Stress and Protects From Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Transplant. Proc. 2018, 50, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belzer, F.O.; Southard, J.H. Principles of solid-organ preservation by cold storage. Transplantation 1988, 45, 673–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, J.C.; Krueger, T.; Yasufuku, K.; de Perrot, M.; Pierre, A.F.; Waddell, T.K.; Singer, L.G.; Keshavjee, S.; Cypel, M. Outcomes after transplantation of lungs preserved for more than 12 h: A retrospective study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017, 5, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Okazaki, M.; Yamane, M.; Miyoshi, K.; Otani, S.; Kakishita, T.; Yoshida, O.; Waki, N.; Toyooka, S.; Oto, T.; et al. Peculiar mechanisms of graft recovery through anti-inflammatory responses after rat lung transplantation from donation after cardiac death. Transpl. Immunol. 2012, 26, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Hengst, W.A.; Gielis, J.F.; Lin, J.Y.; Van Schil, P.E.; De Windt, L.J.; Moens, A.L. Lung ischemia-reperfusion injury: A molecular and clinical view on a complex pathophysiological process. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010, 299, H1283–H1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnaiger, E.; Kuznetsov, A.V.; Rieger, G.; Amberger, A.; Fuchs, A.; Stadlmann, S.; Eberl, T.; Margreiter, R. Mitochondrial defects by intracellular calcium overload versus endothelial cold ischemia/reperfusion injury. Transpl. Int. 2000, 13 (Suppl. 1), S555–S557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).