Abstract

Background/Objectives: Although the binarism between type I and II endometrial cancer was dismissed and substituted with molecular classification, histopathological features remain of paramount importance. Hence, analysing survival outcomes according to histological type, our aim is to clarify whether the morphological features of the tumour retain prognostic relevance in the context of advanced disease. Methods: This is a retrospective analysis led within the Thames Valley Cancer Alliance Network. Results: We include 148 FIGO 2009 stage III–IV patients affected by endometrioid endometrial cancer (EEC) G1, G2, and G3, carcinosarcoma (CS), serous carcinoma (SC), and clear cell carcinoma (CCC) of the uterus. Five year overall survival (OS) is distinct among the histological groups (p-value < 0.001), being 73.3% for G2 endometrioid, 49.2% for G3 endometrioid, 8.3% for CS, and 28.4% for SC. The divergence was marked also for 5 year progression-free survival (PFS) (p-value < 0.001) as follows: for G2 endometrioid, was 76.4%; for G3 endometrioid, 52.7%; and for carcinosarcoma, 5.9%. PFS after 18 months for serous carcinoma was 5.7%. The multivariate analysis found G3 endometrioid (HR 2.91, 95% CI 1.20–7.11, p-value 0.018), carcinosarcoma (HR 12.15, 95% CI 5.07–29.11, p-value < 0.001), and serous carcinoma (HR 4.84, 95% CI 2.16–10.83, p-value < 0.001) as independent predictors of poor survival, as well as cervical invasion (HR 1.83, 95% CI 1.10–3.05, p-value 0.020) as the only histopathological feature confirmed. Regarding progression-free only carcinosarcoma (HR 14.91, 95% CI 5.28–41.11) and serous carcinoma (HR 17.68, 95% CI 6.41–48.75) were associated with an increased risk of recurrence. Conclusions: Our findings testify that, beyond the disease stage, histological subtype remains a major determinant of survival outcome. Cervical involvement is associated with a more aggressive disease, possibly correlated to death beyond relapse. Prospective trials involving advanced stage endometrial cancer, stratified by histological subtype and integrated with the molecular classification, are required.

1. Introduction

According to the World Cancer Research Fund [1], endometrial cancer (EC) ranks as the sixth most common malignancy among women, with more than four hundred thousand new cases diagnosed in 2022. The 2023 guidelines of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) [2] classified EC into the following distinct subtypes: low-grade (G1 and G2) endometrioid endometrial carcinoma (EEC) and high-grade tumours, including high-grade (G3) EEC, serous carcinoma (SC), carcinosarcoma (CS), clear cell carcinoma (CCC), mixed carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, and unusual types. Moreover, the traditional dichotomy between type I and II [3] endometrial carcinoma has been abandoned, replaced by the molecular classification introduced by The Genome Cancer Atlas (TGCA) project [4]. Molecular features were already incorporated in the FIGO 2023 [2] staging system, allowing for both disease stage upgrades and downgrades. Nevertheless, the molecular profiling is not solely used for the classification, as the RAINBO (Refining Adjuvant Treatment in Endometrial Cancer Based on Molecular Features) clinical trial programme is currently exploring how to tailor adjuvant therapies to specific molecular subgroups.

Although the binarism between type I and II was dismissed, histopathological features remain of paramount importance. EECs are graded as G1, G2, and G3 based on architecture, texture, and cytological criteria [5]; furthermore, G1 and G2 EECs are the most common subtypes and are associated with well-established risk factors such as obesity, age, family history, late menopause, prolonged oestrogen therapy, and ethnicity. CS, though rare, has a poorer prognosis and is usually diagnosed in an advanced stage, but also early stages have a negative prognosis [6]. Similarly, SC is not a common disease but often presents with metastatic presentation and poor outcome [7], while CCC is even more rare, with an aggressive behaviour and a marked chemoresistant [8].

In this work we focused only on advanced-stage endometrial cancer (FIGO 2009 Stage III–IV) to verify whether the histology of the tumour changes the prognosis or not and to assess the impact of adjuvant therapy on clinical outcomes. Different histological categories exhibit distinct biological behaviour and treatment responses; nevertheless, their prognostic differences in advanced disease are not fully understood. Hence, analysing survival outcomes according to histological type, our aim was to clarify whether the morphological features of the tumour retain prognostic relevance in the context of advanced disease. We believe that understanding these bonds might supply practical tools to be integrated with the molecular classification.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective analysis led within the Thames Valley Cancer Alliance Network, a catchment area of 2.3 million people. Data collection spanned a 10 year period, from January 2010 to December 2020, and was carried out at Churchill Hospital, Oxford University Hospital Foundation Trust. This manuscript is part of a broader research project with the aim to analyse clinical and histopathological patterns of recurrence and survival of endometrial cancers.

Patients were recruited according to the listed inclusion criteria: age over 18 years of age, the diagnosis of endometrial cancer, and suitability for surgical management. Women under 18 years, presence of synchronous tumours, or the absence of clinical and histopathological reports or follow-up data were excluded from the analysis. For the purpose of this study, only stages III and IV, according to The International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 2009, were included.

Data acquisition encompassed medical and surgical history, surgical and histopathological reports, and follow-up information. These variables were subsequently used for the statistical analysis. Histopathological patterns included in the current study were EEC G1, G2, and G3, as well as SC, CS, and CC. Mixed tumours were excluded. All cases were approached at the multidisciplinary team discussion (MDT), both before and after the surgery, to define the operative approach and the feasibility of adjuvant treatment, according to national guidelines.

The Oxford University Hospitals Trust requirements registered the service evaluation protocol (registration number 5832). The conception of the study, data analysis, interpretation, manuscript drafting, and subsequent revisions were carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the recommendations of the Committee on Publication Ethics, and the reporting of studies conducted using observational routinely collected health data (RECORD) guidelines, endorsed by the Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research Network (EQUATOR). All information was pseudoanonymised, due to the observational design of the research, and no personal element that might allow patient identification was collected. Every participant was adequately informed about the procedures and provided written consent for the use of their clinical data for scientific purposes.

The statistical analysis was performed using IBM©SPSS Statistics 22.0. Continuous variables were analysed using Student’s t-test, while survival outcomes were estimated using Kaplan–Meier and compared with the log-rank test. Risk factors that were chosen for the inquiry were assessed with the univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models. A p-value inferior to 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Variables included in the multivariate analysis were those that resulted in statistical significance from previous works of this group [9,10,11].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

One hundred forty-eight (148) patients with FIGO stage III–IV were surgically treated at Churchill Hospital, and the average age at surgery was 68.8 years (SD ± 10.4 years). Histopathological reports confirmed EEC G1 in 14 patients (9.5%), G2 in 31 (20.9%), and G3 in 24 (16.2%), whereas SC and CS were diagnosed in 42 (28.4%) and 32 (21.6%) patients, respectively. At least, only 5 cases of CC (3.4%) were operated on.

Laparoscopic surgery represented the predominant approach, used in 107 cases (72.3%), while the open approach was indicated only for 37 women (25.0%). Surgical lymph node assessment was undertaken in just 79 cases (53.4%), including 16 (10.8%) with groin sampling and 63 (41.2%) who underwent systematic pelvic and/or paraortic dissection. Unfortunately, 4 cases were omitted from the descriptive surgical analysis due to missing operative notes data. Demographic and surgical information, organised by histotype, is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of histotype distribution and surgical reports.

Histopathological description (Table 2) revealed a vast local disease spread across most cases. Deep myometrial invasion (≥50%) and lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) were the most common features; both occurred in 118 patients (79.7%). Cervical stroma invasion was detected in 67 cases (45.3%), uterine serosal invasion in 60 patients (40.5%), and adnexa and parametrial involvement in 52 specimens (35.1%) each.

Table 2.

Local histopathological features.

The distribution of the FIGO 2009 classification for every histopathological variant is represented in Table 3. Stage IIIA was the most prevalent, recognised in 52 patients (35.1%). Noteworthily, stage IIIC1 was more frequent than stage IIIB (24.3% vs. 20.9%), while stages IIIC2 and IVA were rare, viewed in 8 (5.4%) and 1 (0.7%) case, respectively. Stage IVB was observed in 20 patients (13.5%).

Table 3.

FIGO 2009 classification for each histologycal subtype included in the research.

Adjuvant treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, brachytherapy or a combination) was prescribed in 93 cases out of 148 (62.8%), after MDT. Among these, 5 patients (5.4%) with G1 EEC received adjuvant therapy, as well as 17 women (18.3%) with G2 EEC and 16 (17.2%) with G3 EEC. Twenty-nine patients (31.2%) with SC and 26 (28.0%) with CS took in adjuvant therapy. Unfortunately, follow up data for patients with CC were not available.

Recurrences were detected in 60 women (40.5%), with a median recurrence time of 10 months (IQR 25–75% 4–21 months). In 18 (30.0%) cases the metastases were in a single area as vaginal vault, omentum, lymph nodes and lungs, whereas 42 (70%) patients presented multisite relapses. Interesting, all the recurrences for G1, G2 and G3 EEC were locals or at the lungs, while CS and SC show a more widespread pattern for relapses, ranging from locals and pelvic lymph glands, but also involving bladder, bowel, liver, omentum, lungs, bones, kidneys, adrenal glands and paracardic glands. The distribution of the relpse of the disease was as follows: 6 (10.0%), 9 (15.0%) and 8 (13.3%) for G1, G2 and G3 EEC, while 19 (31.7%) and 18 (30.0%) in CS and SC.

3.2. Survival and Univariate Analysis

Due to the small number of events, limited sample size, and missing data, G1 EEC and CC were not included in the survival analysis.

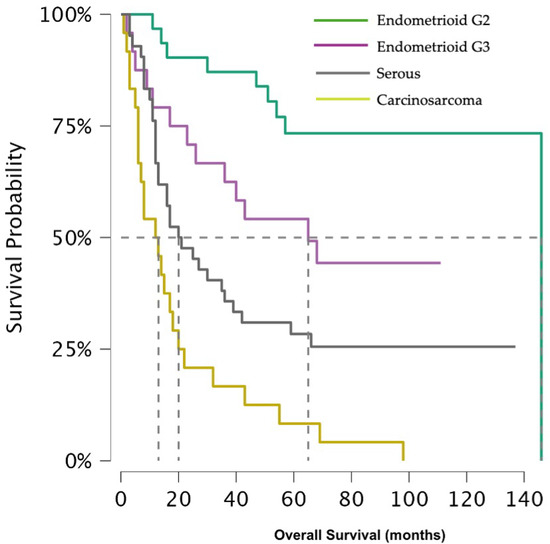

The difference between 5 year overall survival (OS) is distinct among the histological groups (p-value < 0.001) (Figure 1), being 73.3% (95% CI 59.1–91.1%) for G2 EEC and 49.2% (95% CI 32.6–74.4%) for G3 EEC, while a massive decline was observed for CS and SC, with a 5 year OS of 8.3% (95% CI 2.2–31.4%) and 28.4% (95% CI 17.5–46.0%), respectively.

Figure 1.

Shows overall survival across histological subtypes.

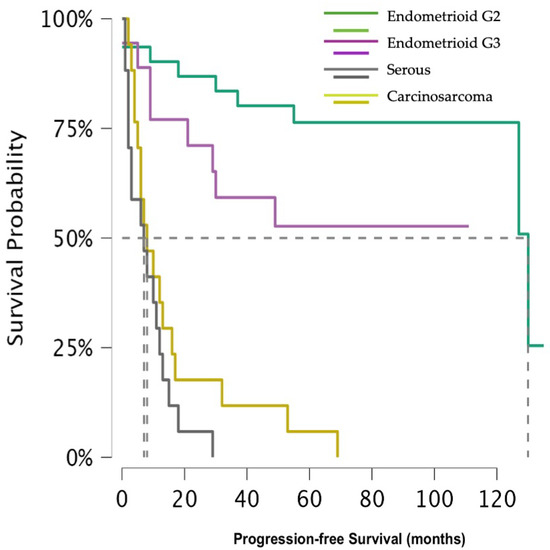

In relation to the 5 year risk of recurrence, the divergence was keen as well (p-value < 0.001) (Figure 2). The 5 year progression-free survival (PFS) for G2 EEC was 76.4% (95% CI 62.4–93.4%), for G3 EEC 52.7% (95% CI 33.4–83.1%), and 5.9% (95% CI 0.9–39.4%) for CS. Due to the small number of events occurring after 18 months, the 5 year PFS for SC could not be calculated, but at that time was 5.7% (95% CI 0.9–39.4%).

Figure 2.

Shows progression-free survival across histological subtypes.

The Cox univariate for OS analysis including only the histotype revealed a worse outcome for G3 EC (p-value 0.028), CS (p-value < 0.001), and SC (p-value < 0.001) compared to G2 EEC, with an hazard ratio (HR) of 2.68 (95% CI 1.11–6.48), 10.52 (95% CI 4.67–23.71) and 4.89 (95% CI 2.23–10.69) for G3 EEC, CS and SC, accordingly. For PFS, G3 EEC had a HR of 2.42 (95% CI 0.87–6.68) than G2 EEC, however this result was not statistically significant (p-value 0.88). In contrast, both CS and SC were associated with a markedly higher risk of recurrence (p-value < 0.001 for both), with a HR notably exceeding those observed for OS. Indeed, CS showed a HR of 11.56 (95% CI 4.64–28.79), while SC of 18.23 (95% CI 6.96–47.73).

A subgroup analysis based on adjuvant treatment revealed a significant difference only in G2 EEC, where the log-rank test indicated a reduce risk of recurrence (p value = 0.039); however, this result was not confirmed in the Cox univariate analysis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis comparing patients who received adjuvant treatment and who did not.

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

In the multivariate analysis we included all the variables that resulted statistically significant in our previous work that treated the single histologies (myometrial invasion equal or more than 50%, LVSI, parametrium, cervical stroma and serosal involvement), assessed across the five histological subgroups included in the present project.

The Cox regression for the OS revealed CS (HR 12.15, 95% CI 5.07–29.11, p-value < 0.001), SC (HR 4.84, 95% CI 2.16–10.83, p-value < 0.001), G3 EEC (HR 2.91, 95% CI 1.20–7.11, p-value 0.018) and cervical involvement (HR 1.83, 95% CI 1.10–3.05, p-value 0.020) as independent predictors of worse survival. Serosal invasion approached statistical significance (p-value 0.058), showing a trend toward an increased risk of death with a HR 1.62 (95% CI 0.98–2.67). All the other factors included were not statistically significant.

With regard to PFS, CS and SC remained strongly associated with an increased risk of recurrence (p-value < 0.001), with a HR of 14.91 (95% CI 5.28–41.11) and 17.68 (95% CI 6.41–48.75), respectively. In this case, G3 EEC was close to significance (p-value 0.055) with a HR for recurrence of 2.75 (95% CI 0.97–7.75).

4. Discussion

Among gynaecological malignancies, uterine cancer has benefited the most from the advent of molecular classification. The new FIGO 2023 staging system not only introduced new stages according to POLE and p53 mutation, but also four risk classes related to histotype and grade, mutations, and FIGO stage [2].

In the present study, we specifically evaluated patients with advanced stage disease (FIGO 2009 stage III–IV) to determine whether histology continues to influence prognosis in this subset. Our findings testify that, beyond the disease stage, histological subtype remains a major determinant of survival outcome. Women affected by G2 and G3 EEC exhibited substantially higher 5 year OS rates (73.3% and 49.2%) compared with those with CS and SC (5 year OS 8.2% and 28.4%). A similar pattern was observed for progression-free survival: 5 year PFS for CS was 5.9%, and at 18 months was 5.7% for SC. These results were also confirmed in the multivariate analysis, which identified cervical involvement as an independent predictor of worse OS, though not of increase recurrence risk. Although adjuvant medical therapy was administered, the small numbers within each specific treatment subgroup rendered further stratified survival analyses statistically underpowered and potentially misleading. For this reason, regimen-specific survival comparisons were not undertaken, as they would not have provided methodologically robust or clinically reliable conclusions.

Our survival results confirm what was previously reported in the literature. A retrospective study [12] including more the two hundred thousand patients comparing survival outcomes across endometrial cancer stages revealed a 5 year OS for stage III G2 EEC of 68.9%, for G3 EEC of 49.6% and for SC of 35.7%. Although, this research did not assess the 5 year PFS nor included CS, its findings corroborate the prognostic hierarchy we observed. Mhawech-Fauceglia et al. [13] described a higher recurrence and mortality rate for SC compared to EEC when considering stage II–III–IV, but when restricting the analysis only to advanced disease the difference did not reach the statistical significance.

This research confirms what our group has previously demonstrated about the correlation between cervical involvement and poorer overall survival [9,10]. Conversely, including different histologies for advanced stage EC, the cervical invasion is not correlated to a worsening of 5 year PFS. Noteworthily, cervical involvement did not affect survival or recurrence in early stage disease when considering CS, CC, and G3 EEC [14]. Specifically, in another research the multivariate analysis failed to confirm the association between cervical stroma involvement and distant metastasis when considering stage I-II endometrioid endometrial cancer [15]. While cervical stroma invasion deteriorates the overall survival in our cohort, this does not happen for the PFS. A possible explanation could be that the cervical involvement is associated with a more aggressive disease, correlated to death beyond relapse. Therefore, women could pass away due to high tumour burden and comorbidities, before manifest a recurrence. Lately, a disease that spread to the cervix could also be less sensitive to adjuvant treatment.

Myometrial invasion has long been recognised as an adverse prognostic factor for both OS and PFS [16]. Zouridis [9] and Smyth et al. [10] confirmed these features in their works on G3 EEC and CS, respectively, as well as Wang et al. [17] did in their work of high grade endometrioid endometrial cancer. Furthermore, the influence of myometrial invasion on survival outcome was also confirmed in other studies including CS [18]. On the other hand, other authors [19] did not confirm this data on G3 EEC and CS in a similar settings.

Parametrial involvement was found to be predictive of higher mortality in G2 EEC [11]. Barquet-Munoz et al. [20] analysed factors associated with parametrial involvement and the effect of lateral invasion on survival considering a population from stage I to IV with endometrial carcinoma, founding the negative effect on OS and PFS. Conversely, when considering only stage III–IV and subtypes like G2 and G3 EEC, CS and SC we did not find any correlation between parametrial invasion and worsening of any outcomes.

Special attention should be given to LVSI, whose importance was emphasised in the latest FIGO 2023 classification [2]. Wang and Zhu [17,19] demonstrated the prognostic role for recurrence and survival of LVSI only in the univariate analysis, while adjusting for other factors they were not be able to confirm the result. This is consistent with our research and those of other investigators [21]. In contrast, a previous retrospective [22] restricted to FIGO 2009 stage III–IV cancer reported LVSI as an independent predictors of poor survival, as well as myometrial invasion, though CS and SC were excluded from that analysis.

Our study is limited by the retrospective design and the lack of molecular classification, which were not yet integrated in the clinical practice during the study period. Molecular classification has been shown to upgrade mainly stage I–II [23], without this substantive effect on advanced stages. However, molecular classification can expand the adjuvant treatment selection with a target therapy, therefore this is an embedded weakness of this study. Nevertheless, the centralization of these women ensured consistent management and reduced surgical variability. Moreover, few studies have focused exclusively on advanced stages, as most include early disease; thus, our cohort size and stage-specific focus represent additional strengths. Overall, our findings may serve as a valuable complement to molecular classification, emphasising that even in the era of genomic classification, tumour stage and histological subtype continue to play a fundamental prognostic role, as confirmed in another recent work [24]. Furthermore, some of our results are aligned with the current literature, however the retrospective nature of both our study and previous reports introduces inherent biases that might explain the inconsistencies reported across studies.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that the prognosis of advanced endometrial cancer is not uniform across histological subtypes. Carcinosarcoma and serous endometrial cancer exhibit the poorest survival outcomes, whereas most conventional prognostic features were not confirmed, apart from cervical invasion, which remained independently associated with reduced overall survival.

This is to say that prospective trials involving advanced stage endometrial cancer, stratified by histological subtype and integrated with the molecular classification, are required to better define prognostic determinants and to refine individualised treatment strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S.M.; methodology, H.S.M. and A.Z.; formal analysis, H.S.M. and A.Z.; data curation, H.S.M., A.Z., C.P., S.L.S., M.A., and S.A.; data collection, A.Z., C.P., M.A., S.L.S., M.A., S.A., N.S., A.K., A.K., A.D., A.S., S.I.N. and S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.M. and J.C.; writing—review and editing, H.S.M., F.F., and J.C.; visualisation, H.S.M., F.F., and A.G.; project administration, H.S.M. and S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Oxford University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (protocol code 5832), on 6 January 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available under reasonable request and after the approval of the corresponding author in order to protect the privacy of our patients.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge all the patients that accepted their data collection and the Oxford University Hospitals to let them develop this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EC | Endometrial cancer |

| FIGO | The International Federation of Gynaecologist and Obstetrics |

| G1/G2 | Low-grade |

| EEC | Endometrioid endometrial carcinoma |

| G3 | High-grade |

| SC | Serous carcinoma |

| CS | Carcinosarcoma |

| CCC | Clear Cell carcinoma |

| TGCA | The Genome Cancer Atlas |

| RAINBO | Refining Adjuvant Treatment in Endometrial Cancer Based on Molecular Features |

| MDT | Multidisciplinary team |

| RECORD | Reporting od studies Conducted using Observational Routinely collected Health Data |

| EQUATOR | Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research Network |

| LVSI | Lymphovascular space invasion |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

- World Cancer Research Fund. Endometrial Cancer Statistics. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/preventing-cancer/cancer-statistics/endometrial-cancer-statistics/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Berek, J.S.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Creutzberg, C.; Fotopoulou, C.; Gaffney, D.; Kehoe, S.; Lindemann, K.-T.; Mutch, D.; Concin, N. Endometrial Cancer Staging Subcommittee; et al. FIGO staging of endometrial cancer: 2023. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 162, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llobet, D.; Pallares, J.; Yeramian, A.; Santacana, M.; Eritja, N.; Velasco, A.; Dolcet, X.; Matias-Guiu, X. Molecular pathology of endometrial carcinoma: Practical aspects from the diagnostic and therapeutic viewpoints. J. Clin. Pathol. 2009, 62, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network; Levine, D.A. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 2013, 497, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höhn, A.K.; Brambs, C.E.; Hiller, G.G.R.; May, D.; Schmoeckel, E.; Horn, L.-C. 2020 WHO Classification of Female Genital Tumors. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2021, 81, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogani, G.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Concin, N.; Ngoi, N.Y.L.; Morice, P.; Caruso, G.; Enomoto, T.; Takehara, K.; Denys, H.; Lorusso, D.; et al. Endometrial carcinosarcoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2023, 33, 147–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogani, G.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Concin, N.; Ngoi, N.Y.L.; Morice, P.; Enomoto, T.; Takehara, K.; Denys, H.; Nout, R.A.; Lorusso, D.; et al. Uterine serous carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 162, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogani, G.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Concin, N.; Ngoi, N.Y.L.; Morice, P.; Enomoto, T.; Takehara, K.; Denys, H.; Lorusso, D.; Vaughan, M.M.; et al. Clear cell carcinoma of the endometrium. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 164, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zouridis, A.; Zarrindej, K.; Rencher, J.; Pappa, C.; Kashif, A.; Smyth, S.L.; Sadeghi, N.; Sattar, A.; Damato, S.; Ferrari, F.; et al. The Prognostic Characteristics and Recurrence Patterns of High Grade Endometrioid Endometrial Cancer: A Large Retrospective Analysis of a Tertiary Center. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth, S.L.; Ripullone, K.; Zouridis, A.; Pappa, C.; Spain, G.; Gkorila, A.; McCulloch, A.; Tupper, P.; Bibi, F.; Sadeghi, N.; et al. Uterine Carcinosarcoma—A Retrospective Cohort Analysis from a Tertiary Centre on Epidemiology, Management Approach, Outcomes and Survival Patterns. Cancers 2025, 17, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zouridis, A.; Kashif, A.; Darwish, A.; Pappa, C.; Ferrari, F.; Smyth, S.L.; Sadeghi, N.; Sattar, A.; Damato, S.; Abdalla, M.; et al. Challenging the Binary Classification of Endometrioid Endometrial Adenocarcinoma: The Evaluation of Grade 2 as an Independent Entity Based on Prognostic Characteristics and Recurrence Patterns. Cancers 2025, 17, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGunigal, M.; Liu, J.; Kalir, T.; Chadha, M.; Gupta, V. Survival Differences Among Uterine Papillary Serous, Clear Cell and Grade 3 Endometrioid Adenocarcinoma Endometrial Cancers: A National Cancer Database Analysis. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2017, 27, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhawech-Fauceglia, P.; Herrmann, R.F.; Kesterson, J.; Izevbaye, I.; Lele, S.; Odunsi, K. Prognostic factors in stages II/III/IV and stages III/IV endometrioid and serous adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2010, 36, 1195–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alektiar, K.M.; McKee, A.; Lin, O.; Venkatraman, E.; Zelefsky, M.J.; McKee, B.; Hoskins, W.J.; Barakat, R.R. Is there a difference in outcome between stage I–II endometrial cancer of papillary serous/clear cell and endometrioid FIGO Grade 3 cancer? Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2002, 54, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuomi, T.; Pasanen, A.; Leminen, A.; Bützow, R.; Loukovaara, M. Prediction of Site-Specific Tumor Relapses in Patients With Stage I-II Endometrioid Endometrial Cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2017, 27, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Hirschowitz, L.; Zaino, R.; Alvarado-Cabrero, I.; Duggan, M.A.; Ali-Fehmi, R.; Euscher, E.; Hecht, J.L.; Horn, L.-C.; Ioffe, O.; et al. Pathologic Prognostic Factors in Endometrial Carcinoma (Other Than Tumor Type and Grade). Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2019, 38, S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Jia, N.; Li, Q.; Wang, C.; Tao, X.; Hua, K.; Feng, W. Analysis of recurrence and survival rates in grade 3 endometrioid endometrial carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 12, 2860–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaal, K.; Kew, F.M.; Tam, K.F.; Lopes, A.; Meirovitz, M.; Naik, R.; Godfrey, K.A.; Hatem, M.H.; Edmondson, R.J. Evaluation of prognostic factors and treatment outcomes in uterine carcinosarcoma. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2009, 143, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wen, H.; Bi, R.; Wu, X. Clinicopathological characteristics, treatment and outcomes in uterine carcinosarcoma and grade 3 endometrial cancer patients: A comparative study. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 27, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquet-Muñoz, S.; Bandala-Jaques, A.; Perez-Montiel, M.D.; Prada, D.; Martínez-Flores, M.; Salcedo-Hernández, R.A.; Pérez-Plasencia, C.; Gonzalez-Enciso, A.; Leon, D.C.-D. Factors Associated with Parametrial Involvement in Endometrial Carcinoma in Patients Treated with Radical Hysterectomy. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2024, 32, 1241–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, S.; Yechieli, R.; Cogan, C.; Hanna, R.; Munkarah, A.; Elshaikh, M.A. The prognostic significance of age in surgically staged patients with Type II endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012, 126, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizzi, V.; Del Vecchio, V.; Pisani, E.; Ranieri, G.; Resta, L.; Cicinelli, E.; Cormio, G. Prognostic factors in endometrial cancer Stages III and IV: A single academic institution experience of 49 patients. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2019, 40, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, F.; Gozzini, E.; Conforti, J.; Giannini, A.; Barra, F.; Fichera, A.; Ferrari, F.A.; Majd, H.S.; Odicino, F. Impact of the FIGO 2023 Staging System on the Adjuvant Treatment of Endometrial Cancer: A Comparative Analysis with FIGO 2009. Cancers 2025, 17, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagher, C.; Mueller, J.J.; Sonoda, Y.; Momeni-Boroujeni, A.; Makker, V.; O’cEarbhaill, R.E.; Alektiar, K.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Leitao, M.M. Prognostic value of ‘aggressive’ histology in surgically staged clinically uterine-confined endometrial carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2025, 35, 102656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).