Abstract

Alopecia areata (AA) is a complex disease with a multifactorial etiology, in which autoimmune mechanisms play a central role. Increasing evidence suggests that AA may be a systemic condition, potentially affecting organs beyond the skin due to shared pathogenic pathways. One proposed mechanism is the breakdown of immune privilege, a protective state that limits immune activity in specific tissues, such as the hair follicle and the eye. Although research on the relationship between AA and ophthalmic comorbidities remains limited, several studies have reported recurrent ocular abnormalities, whether subclinical or symptomatic, appearing at younger ages than typically observed in the general population. This review aims to summarize current knowledge on the association between AA and ocular involvement, exploring shared pathogenic mechanisms, clinical eye manifestations, and practical considerations for addressing ocular symptoms in dermatological practice.

1. Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is an organ-specific autoimmune disease characterized by a variable course, usually of recurrences alternating with remissions, and a wide spectrum of manifestations []. After androgenetic alopecia, it is the second most frequent cause of non-scarring hair loss. It affects 2% of the general population at some point in life, regardless of gender, ethnicity or age [,]. Additionally, this disease is known to have a considerable impact on health-related quality of life [,].

AA is associated with several autoimmune diseases such as thyroid disorders, inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and vitiligo [,,]. Other comorbidities described in the literature are atopy (allergic rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis), iron deficiency anemia, vitamin D deficiency, mental disorders (depression, anxiety, alexithymia, and obsessive–compulsive disorder), diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and hypertension [,,]. Less explored have been ocular and audiological abnormalities, with limited studies demonstrating their presence in the context of AA [,,].

This review synthesizes the existing evidence on ophthalmologic involvement in AA, from its possible etiopathogenic connection, through the ocular clinical manifestations described in patients with this disease in different studies from the 1960s to the present, and concluding with a series of recommendations on the initial approach for dermatologists in clinical practice regarding screening for eye conditions in patients with AA.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a narrative review of the literature in the PubMed, MEDLINE, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar databases, to summarize the literature on the etiopathogenesis of AA and eye diseases, as well as the presence of the latter in AA. We used various combinations of MeSH terms such as “alopecia areata”, “ophthalmology”, “eye”, “eye diseases”, “ocular”, “immune privilege”, as well as the different ocular areas (e.g., eyelids, eyebrows, eyelashes, conjunctiva, cornea, lens, retina, among others). The inclusion criteria were as follows: English and Spanish languages, empirical research and review articles to contextualize and support our findings on immune privilege and other causal factors of AA and ocular diseases, and finally, studies with different methodological designs (e.g., case reports, case series, cross-sectional studies, case–control studies, cohort studies) to document our findings about ophthalmologic comorbidities in AA. The search yielded a total of 82 articles on the etiopathogenesis of AA and eye diseases, and 140 articles on the presence of ocular comorbidities in AA, all published between August 1963 and February 2025, with no duplicate articles. Zotero 7.0.27 was used as the reference management database.

3. Etiopathogenesis of Alopecia Areata and Its Relation to Ocular Involvement

Although the exact cause of alopecia areata is not well understood, immunological factors are considered to play a pivotal role in genetically predisposed individuals, in whom certain environmental factors contribute to triggering the disease [,,,].

3.1. Immunological Factors: What Is Immune Privilege?

Since some organs have a limited capacity to regenerate, even in the setting of minimal inflammation, the human body developed a state of anergy, which means that the detection of antigens is restricted, thus protecting them from damage caused by immune recognition. This adaptive state is known as immune privilege (IP) [].

Organs that have this IP are the eye, the placenta, the liver, the testes, the central nervous system and, thanks to several studies, it has been suggested that the hair follicle is also protected, in particular the bulb during the anagen phase and the bulge throughout the follicular cycle [,,,].

3.1.1. IP in the Hair Follicle

Several mechanisms involved in the generation and preservation of hair follicle IP have been described, which can be grouped into physical barriers, “sequestration” of autoantigens and reduction in immune activity [,,].

As for physical barriers, the epithelial hair bulb lacks lymphatic drainage and is enveloped by a special barrier of extracellular matrix with expression of specific glycosaminoglycans, all of which prevents the trafficking of immune cells to this area [,].

The absent or low expression of classical major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) molecules serves to “sequester” or hide autoantigens associated with melanogenesis and/or the anagen phase and thus prevents their presentation to CD8+ T lymphocytes (CD8+ TL) [,]. Likewise, expression of non-classical MHC-I molecules, such as HLA-E and HLA-G, has been documented to be associated with suppression of CD8+ TL- and natural killer (NK) cell-mediated lysis [].

In relation to the reduction in immune activity, there is local production of potent immunosuppressants such as interleukin-10 (IL-10), transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1), and alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH), among others [,]. These are the so-called IP guardians. Other mechanisms are the production of Fas ligand (FasL) that intervenes to eliminate Fas-expressing autoreactive T cells, and low or absent major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) molecules on Langerhans cells [,,]. In addition, the normal hair follicle suppresses NK activity by these processes: low expression of the activating receptor NKG2D (Natural Killer Group 2D Receptor) along with increased inhibitory receptor KIR (Killer-cell Immunoglobulin-like Receptor) on NK cells, production of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), and decreased or absent expression by the hair follicle of NK cell ligands such as MICA (MHC class I chain-related Chain A) and ULBP3 (UL16-binding protein 3) [,,,].

3.1.2. Ocular IP

The mechanisms of IP in the eye are similar to those described above for the hair follicle. As for the physical barriers, the cornea is avascular, lacks lymphatic vessels, presents a constant regeneration of the epithelium, and a protective layer formed by tight junctions. Similarly, there is a blood–retinal barrier that also has tight junctions formed by retinal pigment epithelial cells [,].

Sequestration or concealment of autoantigens has also been demonstrated, which is achieved by the aforementioned physical barriers, the absence of MHC-II on antigen-presenting cells, and the low expression of classical MHC-I molecules in ocular tissues [,,]. Furthermore, the presence of immature myeloid leukocytes in the cornea facilitates the induction of immune tolerance on the ocular surface [].

In terms of reducing immune activity, aqueous humor and vitreous fluid have anti-inflammatory properties. For example, aqueous humor components suppress antigen-induced lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and inhibit the expression of local delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) responses []. On the other hand, ocular parenchymal cells express FasL which triggers apoptosis of inflammatory cells and, moreover, there is specialized regulatory T-cell (Treg) activity that suppresses Th2 and Th17 lymphocyte-mediated inflammation [,].

Other factors described are inhibition of NK cells and presence of local immunosuppressants such as TGF-β2, α-MSH, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), MIF and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in the aqueous humor [,,].

Two additional mechanisms have been identified: the presence of complement regulatory proteins in the aqueous humor, vitreous fluid and corneal epithelium, and the ACAID [,]. ACAID stands for anterior chamber-associated immune deviation, which is the best studied model of ocular immune tolerance and is regarded as the systemic element of IP, as it involves spleen activity. This phenomenon is characterized by downregulation and suppression of Th1 pathways in response to a foreign protein in the anterior chamber of the eye, and manifests itself in different ways, such as through attenuated systemic DTH responses, stimulation of non-complement-binding IgG1 antibodies, and production of antigen-specific immunomodulatory cells in the spleen (Tregs, marginal zone B cells, γδ Tregs, iNKT, and NK regulatory cells). These cells spread throughout the body and induce antigen-specific immune deviation [,,,,].

It should be noted that IP in hair follicle and eye involves not only specialized local mechanisms that protect against inflammation in situ but also, at least in the case of the eye, includes mechanisms that regulate global immune responses, as we have just seen with the ACAID phenomenon [,,,]. Systemic induction of a tolerogenic response to hair follicle/ocular antigens by induction of Tregs, apoptosis of antigen-specific thymic and peripheral T cell clones, and T cell receptor desensitization are further examples of this [,,,]. All of the aforementioned may also imply that the singular environment at these immunoprivileged sites may impact overall immune responses if tolerance is lost.

A comparative summary of IP in both hair follicle and eye is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative characteristics of immune privilege at the hair follicle and ocular levels.

3.1.3. Loss of IP in AA and Its Connection to Ocular Comorbidities

The main pathophysiological hypothesis of AA is based on the failure of the IP in the anagen hair bulb [,,,,]. However, although this is considered a key condition, it is not sufficient for the development of the disease, and other requirements (autoimmune factors and/or non-immune triggers) must be met for AA to occur [,,]. These circumstances may occur simultaneously or in isolation, as shown in Table 2 [,,,].

Table 2.

Pathogenic conditions necessary for the development of AA.

Induced by all or any of the situations referred to in Table 2, the IP collapses, which means that it loses its ability to induce tolerance and immunoinhibition. This collapse of the IP is required as a final condition for AA to develop, which is characterized by the fact that only hair follicles in anagen III-VI are attacked (period in which mature autoantigens are generated) and, as a consequence, premature termination of the anagen phase ensues, with consequent follicle dystrophy [,,,]. Interestingly, besides causing IP collapse, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) is a potent inducer of catagen in normal human anagen hair follicles [].

It is important to emphasize that IP loss is a complex phenomenon and is therefore not only due to autoimmune factors, but, as described in Table 2, non-immune triggers may also play an important role (e.g., excessive secretion of hair follicle IP collapse inducers in an antigen-non-specific way) [,,,]. Moreover, as previously mentioned, IP is not only a local phenomenon, but also a systemic one, and its collapse could potentially impact the global immune response, affecting both the immunoprivileged organ and probably other tissues [,,,,].

What Is the Phenomenon That Connects AA to Ocular Involvement?

Both the hair follicle and the eye have IP, and the way in which this protection is carried out has similarities (Table 1). Under this premise, it is postulated that IP collapse, usually generated by one or all of the aforementioned pathogenic conditions, is a fundamental factor for the development of AA and ophthalmologic pathologies [,]. Therefore, although more studies are needed in this field, it is considered that in AA the occurrence of ocular comorbidities may be due to pathophysiological phenomena common to both entities, such as TL-mediated autoimmune activity [,,,], or the development of inflammatory events, still considered emerging, of a non-autoimmune nature (e.g., oxidative damage, role of substance P, neurogenic inflammation, dysbiosis) [,,,]. There are several clinical examples of ocular involvement in AA with some autoimmune intervention, such as decreased lacrimal secretion [,], or impairment of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), among others [,,].

Whether the same insult would act to affect different cells in the hair follicle and the eye or whether inflammation in one of these tissues would trigger disease in the other organ remains to be determined [,,]. Likewise, it must be pointed out that the causal correlation between ocular and follicular inflammation has not yet been fully established and therefore remains an area of great interest for further research.

It is crucial to remember that ocular IP is found in several areas such as the cornea, anterior chamber, iris, ciliary body, vitreous humor and retina [,,,,,,,,]. Therefore, IP collapse is a potential factor in the genesis of many of the ocular diseases in AA as will be shown below.

3.2. Other Factors in the Pathogenesis of AA and Ocular Comorbidities

Susceptibility to develop AA is considered to be hereditary, but its occurrence is probably triggered by environmental factors and the same is postulated in the genesis of associated eye diseases [,]. Genome-wide association studies have found that many of the genes involved in AA are also present in other autoimmune conditions, including ocular ones [,]. Consequently, susceptibility loci involving human leukocyte antigen (HLA) regions have been identified, as well as genes associated with functions of innate and adaptive immune responses, such as regulation of self-antigen expression, negative selection of autoreactive TL at the thymic level, Treg differentiation/activity, apoptosis, proinflammatory cytokine production, and chemotaxis, among others [,,].

Regarding systemic inflammation (SI) and its influence on ocular involvement, it is relevant to recognize that IP collapse is not the only feature that could contribute (remember that local and systemic elements intervene in IP). Since SI is multifactorial, it is crucial to highlight that genetic influence, infections, and concomitant autoimmune/non-autoimmune diseases may be implicated in eye abnormalities found in AA [,,,,,,]. In addition, according to several studies, AA is associated with systemic inflammation, as evidenced by increased cardiovascular, atherosclerotic, and peripheral immune biomarkers, and a possible correlation with an increased risk of heart disease and stroke [,,,,].

Among other conditions that can potentially generate ocular compromise in AA is treatment itself. For instance, corticosteroids, commonly used in AA, are able to generate ocular alterations in any of their routes of administration (topical, oral, etc.). The main complications at this level are cataracts and glaucoma [,,]. As for cataracts, they are more likely to be of the posterior subcapsular type, occur with doses higher than 10 mg/day of prednisone or its equivalent for over a year, and children are more susceptible [,,]. Glaucoma is more likely with topical periocular steroid use and with a minimum of 2 weeks of treatment [,,]. On the other hand, topical application of prostaglandin analogs, an alternative in the treatment of eyelash AA [,,], can cause conjunctival hyperemia, dry eye (due to tear film instability), darkening of the iris, pigmentation of the periocular skin, and seldom cystoid macular edema, anterior uveitis, reactivation of herpes simplex keratitis, or iris cysts [,,].

Another factor implicated in the onset and progression of AA and ophthalmologic comorbidities is oxidative stress. Patients with AA have higher levels of lipid peroxidation products and nitric oxide (NO), lower activity of the antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase, and it has been suggested that oxidative stress interferes with follicular cycle [,]. Along the same lines, the lens is under constant photooxidative stress due to its light filtering function, which, coupled with a decrease in the activity of the enzymes glutathione peroxidase and glutathione S-transferase (GST) when exposed to ultraviolet radiation, may increase the likelihood of cataract formation [,]. Given that cataracts have been described in patients with AA with a higher frequency than in the general population, and in some studies independently of other risk factors (e.g., atopy, systemic steroid therapy) [], it would be interesting to clarify the role of oxidative stress in this clinical background.

Furthermore, it should be noted that skin, hair and lens are derived from the ectoderm, so this common embryological origin could also contribute to the development of cataracts in AA [,]. This shared origin also explains why certain conditions, such as ectodermal dysplasias, can manifest with hypotrichosis, eye abnormalities (e.g., dry eyes, cataracts, corneal dysplasia), and other alterations of ectodermal tissues [,].

On the other hand, the role of environmental conditions such as psychological stress seems to play a role in some patients with AA, although this association remains controversial due to disparate results of clinical studies, with some finding no significant relation with the onset of the disease [,,], and others suggesting it as a possible triggering or aggravating circumstance, given that certain patients report stressful events prior to the onset of AA symptoms [,]. In support of the latter theory is the impact of neuroendocrine factors such as substance P (SP), a neuropeptide mentioned above (Table 2), which is released from perifollicular sensory nerve fibers, is recognized for inducing hair follicle IP collapse, and whose production has been linked to psychoemotional stress [,,,,]. Similarly, the participation of substance P in the homeostasis of the corneal epithelium, whose alteration would cause corneal lesions and dry eye disease, as well as in the pathogenesis of uveitis, has been demonstrated in several clinical and experimental trials [,,,].

Another point to consider is the association of AA with other diseases, which in turn will influence the development of ocular pathology. For example, let us look at the relationship between atopic dermatitis and AA [,,,], and also consider that atopic dermatitis has traditionally been associated with keratoconus, blepharitis, and conjunctivitis [,,,]. As we will see below, there is further evidence for the occurrence of these specific eye diseases in AA. Whether atopic dermatitis is the main risk factor for the development of keratoconus, blepharitis, and conjunctivitis in patients with AA or whether AA is an independent condition for these ocular pathologies is a question to be clarified in future research.

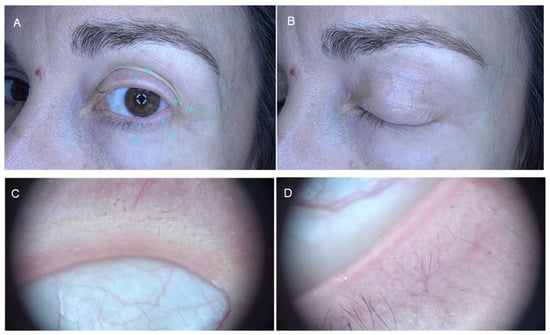

Finally, madarosis in AA can act as a mechanical feature that would add to the etiology of ocular diseases (Figure 1). Madarosis is defined as the total or partial loss of eyebrow or eyelash hair. Milphosis is another term that refers specifically to eyelash loss [,]. Eyebrows and eyelashes provide protection for the ocular area from sweat, microorganisms, dust, irritants, and even light, wind, and water [,]. In alopecia areata, the absence of eyebrows and/or eyelashes is a source of ocular irritation leading to frequent eye rubbing, and the entry of exogenous substances into the ocular surface which, in turn, will participate in the development of blepharitis, dryness, keratoconus and keratitis, including others [,,].

Figure 1.

Eyelash madarosis in alopecia areata. Panels (A,B): Clinical presentation. Panels (C,D): Dermatoscopic images.

4. Clinical Manifestations of Ocular Involvement in AA

Ophthalmologic manifestations in patients diagnosed with AA have been described in numerous studies with various methodological designs, such as case reports, case series, cross-sectional studies, case–control studies or cohorts, with varied findings in both the anterior and posterior segments of the eye.

Table 3 presents the most relevant publications from the 1960s to the present day, ordered by ocular anatomical area, from anterior to posterior segments, accompanied by a section of comments in the third column (see Supplementary Material for this section) on hypotheses about pathogenesis of AA and ophthalmic comorbidities, clinical recommendations (both according to authors of each article) or specific observations regarding the respective study (the latter from our perspective). Some papers are repeated by anatomical area due to findings of more than one clinical manifestation in them. This is only a descriptive table and, therefore, it does not intend to establish etiological associations between AA and ocular findings, so it strictly adheres to what is mentioned in each study by its authors regarding results, causal hypotheses, and patient follow-up.

Table 3.

Main published articles on ocular findings in alopecia areata.

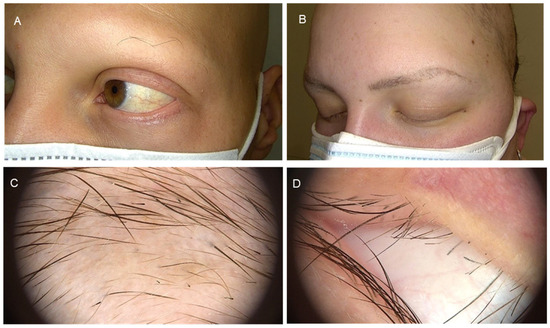

The first part of Table 3 refers to the involvement of eyebrows and eyelashes, which is considered relevant as part of any dermatological and ocular examination. A detailed evaluation of the periocular skin as well as the eyelids is vital in the initial approach, and it is important to be aware that the presence of madarosis can be part of many nosologic entities. Eyebrow and eyelash AA may be underestimated in many cases and has not been widely reported in the literature as a separate entity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Eyebrow and eyelash alopecia areata. Panels (A,B): Clinical presentation. Panels (C,D): Dermatoscopic images.

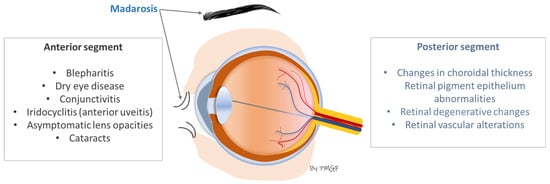

From Table 3, we can see that there are multiple and diverse ophthalmological manifestations described in the literature, based on studies with different methodological designs.

At the periocular level, eyebrow and/or eyelash madarosis is the most frequently observed condition [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,]. Subsequently, if we consider the anterior segment of the eye, we can observe that blepharitis, conjunctivitis, dry eye disease (DED), iridocyclitis, and lens abnormalities are the most common conditions in patients with AA [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,]. With regard to conjunctivitis, in most studies it presented features (conjunctival papillary hypertrophy) or was clearly of the allergic type [,,,]. Furthermore, dry eye symptoms and/or direct evidence of DED based on clinical parameters (ophthalmological examination and miscellaneous tests), was quite common in the AA context, and it is suggested that this condition may be due to alterations in tear stability due to the loss of goblet cells, which in turn arises from the interplay of multiple elements, such as chronic inflammation, autoimmunity, genetic predisposition, and environmental influences [,,,,,].

On the other hand, the most consistently reported lens abnormalities were asymptomatic opacities of various characteristics [,,,,,,,], with punctate opacities being the most common, and cataracts. Regarding this last finding, posterior subcapsular and cortical cataracts were the most frequently encountered [,,,].

It should be noted that, in addition to IP loss, there may be other risk factors involved in the etiology of cataracts in AA, such as oxidative stress, a common embryological origin with the hair follicle (ectoderm), steroid treatment, and atopy [,,,,,,,].

Although it has been described in few studies, it is worth mentioning that there may be an increased risk of keratoconus in patients with AA [,], which may be influenced by factors such as eye rubbing, keratoconjunctivitis, and autoimmune diseases.

Furthermore, when addressing findings in the posterior segment of the eye, it is evident that changes in choroidal thickness, abnormalities of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and degenerative and vascular changes in the retina, were the most consistently reported [,,,,,,,,,,,,,].

In terms of choroidal thickness, it has been observed that in newly diagnosed cases of AA, the choroid is significantly thicker []. However, it is suspected that this thickness could change over time, with the progression of the disease, its severity, and/or the presence of poor prognostic factors (nail involvement, early onset AA, diffuse involvement, positive family history for AA, positive thyroid autoantibodies) [,].

RPE abnormalities are variable and range from hyperplasia to reticular degeneration, pigmentary clumping, and macular changes in the RPE, including others [,,,,,,,,,,,]. Degenerative changes in the retina described in several studies are also prevalent and vary in their presentation: drusen, macular degeneration, and lattice degeneration, to name a few [,,,,,,,,,]. Lastly, retinal vascular changes differ in their manifestations, with hyalinized vessels, acute hemorrhagic retinal vasculitis, and retinal vascular occlusion being reported [,,].

To conclude this overview, we have refractive errors, with myopia and hypermetropia being the most frequently reported [,,,,].

All things considered, it is still pertinent to note that study results are heterogeneous regarding ocular manifestations in AA, and some of them find no significant differences compared to controls in selected clinical features [,,,,]. In the same way, the current evidence has limitations that should be kept in mind when interpreting its results, such as small size of some samples, retrospective designs, and potential confounding factors in certain studies (e.g., atopy, corticosteroid use, associated autoimmune diseases).

As the final part of this clinical section, Figure 3 summarizes the most common ophthalmological manifestations in patients with AA, as explained above.

Figure 3.

Most frequent ocular manifestations in patients with AA.

5. What Would Be the Initial Approach to Ocular Comorbidities in Patients with AA in Dermatological Practice?

Recognition of ophthalmological conditions in patients with AA will only be possible if it is taken into account that such involvement is likely in this context. In follow-up visits for alopecia, a series of “key questions” can be incorporated to detect ocular symptoms, based on which it may be possible to identify the presence of eye conditions that should be evaluated or treated by other specialists.

5.1. General Key Questions Regarding Ocular Symptoms for Dermatologists

It is advisable to start with a broad approach, for which the use of general questions will allow for the more efficient detection of ophthalmological symptoms []:

Do you currently have any problems with your eyes?/Is there anything about your eyes that worries or concerns you?

Is the problem affecting one or both eyes?

Did it start suddenly or gradually?

Have your symptoms improved, worsened, or remained the same since the beginning?

Has your problem been intermittent or seasonal, or does it worsen at any time of day? If so, what makes it better or worse?

Have you had any eye problems in the past?

Have you had any eye surgery?

Are you taking any medications? Do you use any products/medicines for your eyes?

Has anyone in your family been diagnosed with eye diseases?

5.2. Specific Key Questions According to the Eye Condition Reported in AA for Dermatologists

Based on what we have detected in the general questionnaire, we propose to move forward with specific questions, starting with the structures of the anterior segment of the eye and continuing with those that make up the posterior segment.

Consequently, we have relied on the most common ophthalmological manifestations in patients with AA, as reported in the scientific literature cited in Table 3 and summarized in Figure 3, to organize these specific key questions that should be asked during the dermatological consultation, as shown in Table 4 and Table 5 [,,,,,,,,].

Table 4.

Key questions about ocular anterior segment involvement for dermatologists.

Table 5.

Key questions about ocular posterior segment involvement for dermatologists.

5.3. Another Assessment Worth Considering Regarding the Evaluation of Ocular Involvement in AA

A valuable contribution to the comprehensive approach to eye disorders in AA would be to assess disease burden caused specifically by such involvement. In this context, patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are tools that could contribute not only to the detection of ophthalmic diseases (for example, through the reporting of symptoms) but also to timely treatment and improved quality of life. PROs are defined as outcomes reported by the patient where there is no clinical interpretation []. Simple descriptions of symptoms or composite outcomes, such as patient satisfaction or health-related quality of life, are ways to assess PROs [,]. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), Skindex-29, and Skindex-16 are some examples of validated PROs in dermatology [,]. Some of the specific PROs for alopecia areata that have been validated are the Alopecia Areata Patient Priority Outcomes (AAPPO) and the Alopecia Areata Symptom Impact Scale (AASIS) [,,].

Several studies in AA have incorporated PROs into the initial examination and follow-up of these patients, and some of them have evaluated ocular findings using these measures [,,,,,,]. Therefore, it would be a fundamental contribution if, in addition to the general and specific anamnesis proposed above, some PROs focused on eye symptoms in AA patients were included, mainly in new research and, hopefully, in the future and, as far as possible, in daily clinical practice.

5.4. Recommendations on Initial Ophthalmological Management, Multidisciplinary Approach, and Follow-Up

In this section, we include guidance on conditions affecting the ocular surface (blepharitis, dry eye disease and keratitis), which cause symptoms such as dryness, irritation, redness, and discomfort. Other common eye conditions reported in AA (e.g., cataracts, retinal disorders) should be finally confirmed and treated directly by an ophthalmologist, as their management exceeds the scope of this article.

In cases where there are mild ocular surface symptoms and no red flags, dermatologists may initiate treatment as part of the overall management plan. However, for more complex or severe cases, coordination with ophthalmology is essential to ensure comprehensive care.

For first-line management of ocular surface disease, eyelid hygiene is essential. Regular cleaning of the eyelid margin is recommended to remove debris, crusts, and bacteria. Warm compresses and gentle eyelid scrubs with products such as baby shampoo or commercial eyelid cleansers are effective options [,,]. As for lubricants, preservative-free artificial tears should be used regularly to alleviate dryness and prevent ocular surface damage. In cases of persistent dryness, gel lubricants or ointments applied at night can provide longer-lasting relief [,]. Regarding environmental measures, patients should avoid dry, windy, or air-conditioned environments, and the use of humidifiers in dry settings may be beneficial [,]. In cases where conservative measures are insufficient, especially in patients with moderate to severe dry eye or those who do not respond to topical lubricants, topical treatments including cyclosporine, insulin or, autologous serum can be considered, although these must be prescribed by an ophthalmologist [,,].

It is important to coordinate early involvement of ophthalmology when initiating systemic therapies for AA, such as corticosteroids, JAK inhibitors, or immunosuppressants, as these treatments may exacerbate or predispose patients to eye disease [,,]. In this way, the onset of potential complications, such as elevated intraocular pressure, cataracts, or ocular surface diseases, can be monitored.

Concerning follow-up schedules, a comprehensive ocular surface examination should be performed at the start of systemic therapy to establish a baseline for the patient’s eye health. A follow-up visit should be scheduled 1 to 2 months after initiating systemic therapy to assess any changes. Once systemic therapy has stabilized, follow-up every 6–12 months may be appropriate, although any significant changes in eye symptoms or signs should prompt earlier reevaluation. Continued coordination between dermatology, ophthalmology, and other specialists is essential for comprehensive care, especially for patients undergoing long-term systemic therapy.

6. Conclusions

Patients with AA appear to be at higher risk of developing ocular involvement in different anatomical areas, as has been demonstrated in various studies. These manifestations range from madarosis, blepharitis, dry eye disease (DED), and conjunctivitis, to cataracts, choroidal thickness alterations, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) abnormalities, and retinal degeneration or vascular changes. Some of these conditions, whether acute or chronic, may, in rare cases, lead to permanent visual impairment.

The relationship between ophthalmological disorders and AA has not been fully elucidated; however, the evidence to date supports a shared immunological basis (collapse of immune privilege) in genetically susceptible patients exposed to environmental triggers. In view of the above and as a precautionary measure, we recommend that dermatologists include a history of ocular symptoms, both through anamnesis and other measurements (e.g., PROs), preferably in all patients with AA. This would enable early detection of comorbidities and prevention of disease progression, ensuring referral to ophthalmology when appropriate.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm14238409/s1, Table S1: Main published articles on ocular findings in alopecia areata.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M.G.F., D.S.-C. and S.V.-G.; Methodology, P.M.G.F., D.B.-C., D.S.-C. and S.V.-G.; Validation, D.B.-C., Á.H.-G., B.B.-B., P.B.-B., D.S.-C. and S.V.-G.; Writing—original draft preparation, P.M.G.F.; Writing—review and editing, P.M.G.F., D.B.-C., Á.H.-G., B.B.-B., P.B.-B., D.S.-C. and S.V.-G.; Visualization, P.M.G.F.; Supervision, D.S.-C., B.B.-B. and S.V.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Further inquiries should be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AA | Alopecia areata |

| IP | Immune privilege |

| MHC-I | Major histocompatibility complex class I |

| MHC-II | Major histocompatibility complex class II |

| CD8+ TL | CD8+ T lymphocytes |

| NK | Natural killer cell |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor β1 |

| α-MSH | Alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| FasL | Fas ligand |

| NKG2D | Natural Killer Group 2D Receptor |

| KIR | Killer-cell Immunoglobulin-like Receptor |

| MIF | Macrophage migration inhibitory factor |

| MICA | MHC class I chain-related Chain A |

| ULBP3 | UL16-binding protein 3 |

| DTH | Delayed-type hypersensitivity |

| Treg | Regulatory T-cell |

| Th2 | Type 2 helper T cell |

| Th17 | Type 17 helper T cell |

| VIP | Vasoactive intestinal peptide |

| CGRP | Calcitonin gene-related peptide |

| ACAID | Anterior chamber-associated immune deviation |

| Th1 | Type 1 helper T cell |

| IgG1 | Immunoglobulin G1 |

| γδ Tregs | Gamma-delta regulatory T cells |

| iNKT | Invariant natural killer cell |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| SP | Substance P |

| HLA | Human leukocyte antigen |

| SI | Systemic inflammation |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| GST | Glutathione S-transferase |

| AU | Alopecia universalis |

| AT | Alopecia totalis |

| TL | T lymphocytes |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| PRO | Patient-reported outcomes |

| DLQI | Dermatology Life Quality Index |

| DED | Dry eye disease |

| VKH | Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada |

| IU | Intermediate uveitis |

| CT | Choroidal thickness |

| RPE | Retinal pigment epithelium |

| RNFL | Retinal nerve fiber layer |

| THS | Tolosa–Hunt Syndrome |

| SLE | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| IOP | Intraocular pressure |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| n | Number |

| aHR | Adjusted hazard ratio |

| AAPO | Alopecia Areata Patient Priority Outcomes |

| AASIS | Alopecia Areata Symptom Impact Scale |

References

- Pratt, C.H.; King, L.E.; Messenger, A.G.; Christiano, A.M.; Sundberg, J.P. Alopecia areata. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterkens, A.; Lambert, J.; Bervoets, A. Alopecia areata: A review on diagnosis, immunological etiopathogenesis and treatment options. Clin. Exp. Med. 2021, 21, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J. Alopecia areata: An update on etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 61, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rencz, F.; Gulácsi, L.; Péntek, M.; Wikonkál, N.; Baji, P.; Brodszky, V. Alopecia areata and health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2016, 175, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.Y.; King, B.A.; Craiglow, B.G. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) among patients with alopecia areata (AA): A systematic review. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 806–812.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.P.; Mullangi, S.; Guo, Y.; Qureshi, A.A. Autoimmune, atopic, and mental health comorbid conditions associated with alopecia areata in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2013, 149, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egeberg, A.; Anderson, S.; Edson-Heredia, E.; Burge, R. Comorbidities of alopecia areata: A population-based cohort study. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 46, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senna, M.; Ko, J.; Tosti, A.; Edson-Heredia, E.; Fenske, D.C.; Ellinwood, A.K.; Rueda, M.J.; Zhu, B.; King, B. Alopecia areata treatment patterns, healthcare resource utilization, and comorbidities in the US population using insurance claims. Adv. Ther. 2021, 38, 4646–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conic, R.Z.; Tamashunas, N.L.; Damiani, G.; Fabbrocini, G.; Cantelli, M.; Young Dermatologists Italian Network; Bergfeld, W.F. Comorbidities in pediatric alopecia areata. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 2898–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, W.-S. Comorbidities in alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 466–477.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucak, H.; Soylu, E.; Ozturk, S.; Demir, B.; Cicek, D.; Erden, I.; Akyigit, A. Audiological abnormalities in patients with alopecia areata. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014, 28, 1045–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recupero, S.M.; Abdolrahimzadeh, S.; De Dominicis, M.; Mollo, R.; Carboni, I.; Rota, L.; Calvieri, S. Ocular alterations in alopecia areata. Eye 1999, 13, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simakou, T.; Butcher, J.P.; Reid, S.; Henriquez, F.L. Alopecia areata: A multifactorial autoimmune condition. J. Autoimmun. 2019, 98, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, F.; Drake, L.A.; Senna, M.M.; Rezaei, N. Alopecia areata: A review of disease pathogenesis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 179, 1033–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, C.F.; Billingham, R.E. Analysis of local anatomic factors that influence the survival times of pure epidermal and full-thickness skin homografts in guinea pigs. Ann. Surg. 1972, 176, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Ito, N.; Saatoff, M.; Hashizume, H.; Fukamizu, H.; Nickoloff, B.J.; Takigawa, M.; Paus, R. Maintenance of hair follicle immune privilege is linked to prevention of NK cell attack. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 1196–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petukhova, L.; Duvic, M.; Hordinsky, M.; Norris, D.; Price, V.; Shimomura, Y.; Kim, H.; Singh, P.; Lee, A.; Chen, W.V.; et al. Genome-wide association study in alopecia areata implicates both innate and adaptive immunity. Nature 2010, 466, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolini, M.; McElwee, K.; Gilhar, A.; Bulfone-Paus, S.; Paus, R. Hair follicle immune privilege and its collapse in alopecia areata. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 29, 703–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paus, R.; Ito, N.; Takigawa, M.; Ito, T. The hair follicle and immune privilege. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2003, 8, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paus, R.; Bertolini, M. The role of hair follicle immune privilege collapse in alopecia areata: Status and perspectives. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2013, 16, S25–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Aristizábal, I.; Mera, J.J.; Giraldo, J.D.; Lopez-Arevalo, H.; Tobón, G.J. From ocular immune privilege to primary autoimmune diseases of the eye. Autoimmun. Rev. 2022, 21, 103122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mölzer, C.; Heissigerova, J.; Wilson, H.M.; Kuffova, L.; Forrester, J.V. Immune privilege: The microbiome and uveitis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 608377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederkorn, J.Y. Mechanisms of immune privilege in the eye and hair follicle. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2003, 8, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Alemi, H.; Dohlman, T.; Dana, R. Immune regulation of the ocular surface. Exp. Eye Res. 2022, 218, 109007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gery, I.; Caspi, R.R. Tolerance induction in relation to the eye. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keino, H.; Horie, S.; Sugita, S. Immune privilege and eye-derived T-regulatory cells. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 1679197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masli, S.; Vega, J.L. Ocular immune privilege sites. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 677, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janeway, C.A., Jr.; Travers, P.; Walport, M.; Shlomchik, M.J. Self-tolerance and its loss. In Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease, 5th ed.; Lawrence, E., Austin, P., Eds.; Garland Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 531–543. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, T.; Zhang, T.; Miao, F.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Tai, Z.; He, Z. Alopecia areata: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapies. MedComm 2025, 6, e70182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, S.J.; Jabbari, A. The current state of knowledge of the immune ecosystem in alopecia areata. Autoimmun. Rev. 2022, 21, 103061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paus, R.; Bulfone-Paus, S.; Bertolini, M. Hair follicle immune privilege revisited: The key to alopecia areata management. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2018, 19, S12–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilhar, A.; Paus, R.; Kalish, R.S. Lymphocytes, neuropeptides, and genes involved in alopecia areata. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 2019–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilhar, A.; Laufer-Britva, R.; Keren, A.; Paus, R. Frontiers in alopecia areata pathobiology research. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 144, 1478–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Ito, N.; Saathoff, M.; Bettermann, A.; Takigawa, M.; Paus, R. Interferon-gamma is a potent inducer of catagen-like changes in cultured human anagen hair follicles. Br. J. Dermatol. 2005, 152, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilhar, A. Collapse of immune privilege in alopecia areata: Coincidental or substantial? J. Investig. Dermatol. 2010, 130, 2535–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Caspi, R.R. Ocular immune privilege. F1000 Biol. Rep. 2010, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinori, M.; Kloepper, J.E.; Paus, R. Can the hair follicle become a model for studying selected aspects of human ocular immune privilege? Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 4447–4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paus, R.; Nickoloff, B.J.; Ito, T. A “hairy” privilege. Trends Immunol. 2005, 26, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ergin, C.; Acar, M.; Kaya Akış, H.; Gönül, M.; Gürdal, C. Ocular findings in alopecia areata. Int. J. Dermatol. 2015, 54, 1315–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmer, O.; Karadag, R.; Cakici, O.; Bilgili, S.G.; Demircan, Y.T.; Bayramlar, H.; Karadag, A.S. Ocular findings in patients with alopecia areata. Int. J. Dermatol. 2016, 55, 814–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandhi, D.; Singal, A.; Gupta, R.; Das, G. Ocular alterations in patients of alopecia areata. J. Dermatol. 2009, 36, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oltulu, P.; Oltulu, R.; Turk, H.B.; Turk, N.; Kilinc, F.; Belviranli, S.; Mirza, E.; Ataseven, A. The ocular surface findings in alopecia areata patients: Clinical parameters and impression cytology. Int. Ophthalmol. 2022, 42, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bron, A.J.; de Paiva, C.S.; Chauhan, S.K.; Bonini, S.; Gabison, E.E.; Jain, S.; Knop, E.; Markoulli, M.; Ogawa, Y.; Perez, V.; et al. TFOS DEWS II pathophysiology report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 438–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosti, A.; Colombati, S.; De Padova, M.P.; Guidi, S.G.; Tosti, G.; Maccolini, E. Retinal pigment epithelium function in alopecia areata. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1986, 86, 553–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadeja, S.D.; Tobin, D.J. Autoantigen discovery in the hair loss disorder, alopecia areata: Implication of post-translational modifications. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 890027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Hill, L.J.; Downie, L.E.; Chinnery, H.R. Neuroimmune crosstalk in the cornea: The role of immune cells in corneal nerve maintenance during homeostasis and inflammation. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2022, 91, 101105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, T.; Lam, E.; Alvarez, D.; Sun, Y. Ocular vascular diseases: From retinal immune privilege to inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.-F.; Brown, M.A. Progress in the genetics of uveitis. Genes Immun. 2022, 23, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, K.K.-H.; Marson, A.; Zhu, J.; Kleinewietfeld, M.; Housley, W.J.; Beik, S.; Shoresh, N.; Whitton, H.; Ryan, R.J.H.; Shishkin, A.A.; et al. Genetic and epigenetic fine mapping of causal autoimmune disease variants. Nature 2015, 518, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, V.E.; Faniel, M.L.; Kamili, N.A.; Krueger, L.D.; Zhu, C. Immune-mediated alopecias and their mechanobiological aspects. Cells Dev. 2022, 170, 203793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Wei, W.B.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.X. Systemic inflammation and eye diseases. The Beijing Eye Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Rao, N.A. Grand challenges in ocular inflammatory diseases. Front. Ophthalmol. 2022, 2, 756689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glickman, J.W.; Dubin, C.; Renert-Yuval, Y.; Dahabreh, D.; Kimmel, G.W.; Auyeung, K.; Estrada, Y.D.; Singer, G.; Krueger, J.G.; Pavel, A.B.; et al. Cross-sectional study of blood biomarkers of patients with moderate to severe alopecia areata reveals systemic immune and cardiovascular biomarker dysregulation. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 84, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.H.; Santos, L.; Li, X.Y.; Tran, A.; Kim, S.S.Y.; Woo, K.; Shapiro, J.; McElwee, K.J. Alopecia areata is associated with increased expression of heart disease biomarker cardiac troponin I. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2018, 98, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-H.; Lin, H.-C.; Kao, S.; Tsai, M.-C.; Chung, S.-D. Alopecia areata increases the risk of stroke: A 3-year follow-up study. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-W.; Kang, T.; Lee, J.S.; Kang, M.J.; Huh, C.-H.; Kim, M.-S.; Kim, H.J.; Ahn, H.S. Time-dependent risk of acute myocardial infarction in patients with alopecia areata in Korea. JAMA Dermatol. 2020, 156, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgos-Blasco, P.; Gonzalez-Cantero, A.; Hermosa-Gelbard, A.; Jiménez-Cahue, J.; Buendía-Castaño, D.; Berna-Rico, E.; Abbad-Jaime de Aragón, C.; Vañó-Galván, S.; Saceda-Corralo, D. Subclinical atherosclerosis in alopecia areata: Usefulness of arterial ultrasound for disease diagnosis and analysis of its relationship with cardiometabolic parameters. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, B.; Kumar, H.M.; Palaniswami, S.; Lakshman, B.H. Ocular side effects of systemic drugs used in dermatology. Indian J. Dermatol. 2019, 64, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strazzulla, L.C.; Wang, E.H.C.; Avila, L.; Lo Sicco, K.; Brinster, N.; Christiano, A.M.; Shapiro, J. Alopecia areata: An appraisal of new treatment approaches and overview of current therapies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phulke, S.; Kaushik, S.; Kaur, S.; Pandav, S.S. Steroid-induced glaucoma: An avoidable irreversible blindness. J. Curr. Glaucoma Pract. 2017, 11, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, B.; Hu, J.K.; Tosti, A. Eyebrow and eyelash alopecia: A clinical review. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2023, 24, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, A.; Bergfeld, W. Treatment for facial alopecia areata: A systematic review with evidence-based analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, A.; Grierson, I.; Shields, M.B. Side effects associated with prostaglandin analog therapy. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2008, 53, S93–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, M.; Kaštelan, S.; Soldo, K.M.; Salopek-Rabatić, J. Influence of BAK-preserved prostaglandin analog treatment on the ocular surface health in patients with newly diagnosed primary open-angle glaucoma. Biomed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 603782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Huang, B.; Yang, J. Ocular surface changes in prostaglandin analogue-treated patients. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 2019, 9798272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koca, R.; Armutcu, F.; Altinyazar, C.; Gürel, A. Evaluation of lipid peroxidation, oxidant/antioxidant status, and serum nitric oxide levels in alopecia areata. Med. Sci. Monit. 2005, 11, CR296–CR299. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel Fattah, N.S.A.; Ebrahim, A.A.; El Okda, E.S. Lipid peroxidation/antioxidant activity in patients with alopecia areata. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2011, 25, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadat, M.; Farvardin-Jahromi, M. Occupational sunlight exposure, polymorphism of glutathione S-transferase M1, and senile cataract risk. Occup. Environ. Med. 2006, 63, 503–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamari, F.; Hallaj, S.; Dorosti, F.; Alinezhad, F.; Taleschian-Tabrizi, N.; Farhadi, F.; Aslani, H. Phototoxicity of environmental radiations in human lens: Revisiting the pathogenesis of UV-induced cataract. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2019, 257, 2065–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itin, P.H.; Fistarol, S.K. Ectodermal dysplasias. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2004, 131C, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russiello, F.; Arciero, G.; Decaminada, F.; Corona, R.; Ferrigno, L.; Fucci, M.; Pasquini, M.; Pasquini, P. Stress, attachment and skin diseases: A case-control study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 1995, 5, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picardi, A.; Pasquini, P.; Cattaruzza, M.S.; Gaetano, P.; Baliva, G.; Melchi, C.F.; Papi, M.; Camaioni, D.; Tiago, A.; Gobello, T.; et al. Psychosomatic factors in first-onset alopecia areata. Psychosomatics 2003, 44, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brajac, I.; Tkalcic, M.; Dragojević, D.M.; Gruber, F. Roles of stress, stress perception and trait-anxiety in the onset and course of alopecia areata. J. Dermatol. 2003, 30, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolache, L.; Benea, V. Stress in patients with alopecia areata and vitiligo. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2007, 21, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manolache, L.; Petrescu-Seceleanu, D.; Benea, V. Alopecia areata and relationship with stressful events in children. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2009, 23, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina Ayuso, V.; Pott, J.W.; de Boer, J.H. Intermediate uveitis and alopecia areata: Is there a relationship? Report of 3 pediatric cases. Pediatrics 2011, 128, e1013–e1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E.M.J.; Liotiri, S.; Bodó, E.; Hagen, E.; Bíró, T.; Arck, P.C.; Paus, R. Probing the effects of stress mediators on the human hair follicle: Substance P holds central position. Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 171, 1872–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzawi, S.; Penzi, L.R.; Senna, M.M. Immune privilege collapse and alopecia development: Is stress a factor. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018, 4, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Smet, M.D.; Chan, C.C. Regulation of ocular inflammation—What experimental and human studies have taught us. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2001, 20, 761–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taketani, Y.; Marmalidou, A.; Dohlman, T.H.; Singh, R.B.; Amouzegar, A.; Chauhan, S.K.; Chen, Y.; Dana, R. Restoration of regulatory T-cell function in dry eye disease by antagonizing substance P/neurokinin-1 receptor. Am. J. Pathol. 2020, 190, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.; Kong, D. Bilateral association between atopic dermatitis® and alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatitis 2024, 35, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyssen, J.P.; Toft, P.B.; Halling-Overgaard, A.-S.; Gislason, G.H.; Skov, L.; Egeberg, A. Incidence, prevalence, and risk of selected ocular disease in adults with atopic dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 77, 280–286.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govind, K.; Whang, K.; Khanna, R.; Scott, A.W.; Kwatra, S.G. Atopic dermatitis is associated with increased prevalence of multiple ocular comorbidities. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 298–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravn, N.H.; Ahmadzay, Z.F.; Christensen, T.A.; Larsen, H.H.P.; Loft, N.; Rævdal, P.; Heegaard, S.; Kolko, M.; Egeberg, A.; Silverberg, J.I.; et al. Bidirectional association between atopic dermatitis, conjunctivitis, and other ocular surface diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 85, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Huang, T.; Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, D. Causal association between atopic dermatitis and keratoconus: A mendelian randomization study. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vij, A.; Bergfeld, W.F. Madarosis, milphosis, eyelash trichomegaly, and dermatochalasis. Clin. Dermato.l 2015, 33, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starace, M.; Cedirian, S.; Alessandrini, A.M.; Bruni, F.; Quadrelli, F.; Melo, D.F.; Silyuk, T.; Doroshkevich, A.; Piraccini, B.M.; Iorizzo, M. Impact and management of loss of eyebrows and eyelashes. Dermatol. Ther. 2023, 13, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, J.V. The biology, structure, and function of eyebrow hair. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2014, 13 (Suppl. S1), s12–s16. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, B.P.; Eisman, S.; Yip, L. Acquired causes of eyebrow and eyelash loss: A review and approach to diagnosis and treatment. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2023, 64, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insler, M.S.; Helm, C.J. Alopecia areata including the cilia and brows of two sisters. Ann. Ophthalmol. 1989, 21, 451–453. [Google Scholar]

- Offret, H.; Venencie, P.Y.; Gregoire-Cassoux, N. [Madarosis and alopecia areata of eyelashes]. J. Fr. Ophtalmol. 1994, 17, 486–488. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, K.H.; Lee, S.H.; Ahn, S.K.; Lee, W.S. A case of alopecia universalis without the involvement of scalp hairs. Yonsei Med. J. 1995, 36, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, M.C.; Cohen, P.R.; Grossman, M.E. Acquired eyelash trichomegaly and alopecia areata in a human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient. Dermatology 1996, 193, 52–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elston, D.M. What is your diagnosis? Alopecia areata of the eyelashes. Cutis 2002, 69, 15, 19–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mehta, J.S.; Raman, J.; Gupta, N.; Thoung, D. Cutaneous latanoprost in the treatment of alopecia areata. Eye 2003, 17, 444–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandhe, N.P.; Kanwar, A.J. Alopecia areata of eyelashes: A subset of alopecia areata. Dermatol. Online J. 2004, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazareth, M.R.; Bunimovich, O.; Rothman, I.L. Trichomegaly in a 3-year-old girl with alopecia areata. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2009, 26, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droubi, D.; Nazareth, M.R.; Rothman, I.L. Long-term follow-up of previously reported case of trichomegaly associated with alopecia areata in a 3-year-old girl. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2012, 29, 234–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modjtahedi, B.S.; Kishan, A.U.; Schwab, I.R.; Jackson, W.B.; Maibach, H.I. Eyelash alopecia areata: Case series and literature review. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 47, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrade, F.A.; Giavedoni, P.; Keller, J.; Sainz-de-la-Maza, M.T.; Ferrando, J. Ocular findings in patients with alopecia areata: Role of ultra-wide-field retinal imaging. Immunol. Res. 2014, 60, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrwich, K.W.; Kitchen, H.; Knight, S.; Aldhouse, N.V.J.; Macey, J.; Nunes, F.; Dutronc, Y.; Mesinkovska, N.A.; Ko, J.M.; King, B.A. The role of patients in alopecia areata endpoint development: Understanding physical signs and symptoms. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2020, 20, S71–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, Y.M.F.; Nymand, L.; DeLozier, A.M.; Burge, R.; Edson-Heredia, E.; Egeberg, A. Patient characteristics and disease burden of alopecia areata in the Danish Skin Cohort. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e053137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atış, G.; Sarı, A.Ş.; Güneş, P.; Sönmez, C. Isolated hair loss on the eyebrow: Five cases with trichoscopic features. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2022, 97, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, C.; Blasco, M.C.; McCabe, M.; Therianou, A.; Watchorn, R.E. Segmental alopecia areata affecting the scalp, eyebrow, and lash line: A novel presentation. JAAD Case Rep. 2022, 29, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foad, E.G.A.; Rabea, M.A.; Yusef, N.M.; Amer, M.A.E. Ocular manifestations associated with alopecia areata. Al-Azhar Int. Med. J. 2023, 4, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kissouni, A.; Hali, F.; Chiheb, S. Alopecia areata of eyelashes: A rare and unrecognized subset of alopecia areata. Int. J. Dermatol. 2023, 62, e589–e590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Xu, X.; Chen, P. Nine-year-old boy with goitre, blepharoptosis and alopecia areata. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2022, 58, 721–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thatiparthi, A.; Martin, A.; Suh, S.; Yale, K.; Atanaskova Mesinkovska, N. Inflammatory ocular comorbidities in alopecia areata: A retrospective cohort study of a single academic center. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 88, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.C.; Pollard, Z.F.; Jarrett, W.H. Ocular and testicular abnormalities in alopecia areata. Arch. Dermatol. 1982, 118, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak Altintas, A.G.; Gül, U.; Duman, S. Bilateral keratoconus associated with hashimoto’s disease, alopecia areata and atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 1999, 9, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, E.; Fong, K.S.; Al Jajeh, I.; Nassiri, N.; Rootman, J. The association of lacrimal gland inflammation with alopecia areata. Orbit 2015, 34, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Blasco, B.; Burgos-Blasco, P.; Rodriguez-Quet, O.; Arriola-Villalobos, P.; Fernandez-Vigo, J.I.; Saceda-Corralo, D.; Vaño-Galvan, S.; García-Feijóo, J. Alterations in corneal sensitivity, staining and biomechanics of alopecia areata patients: Novel findings in a case-control study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chachin, M.; Hirose, T.; Nakamura, K.; Shi, N.; Hiro, S.; Imafuku, S. Prevalence and incidence of comorbidities in patients with atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, alopecia areata, and vitiligo using a Japanese claims database. J. Dermatol. 2025, 52, 841–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, W.M.; Mir, M.R.; Hsu, S. Vogt-Koyanagi-harada syndrome: Association with alopecia areata. Dermatol. Online J. 2009, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, S.A.; Brunsting, L.A. Cataracts in alopecia areata. Report of five cases. Arch. Dermatol. 1963, 88, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerly, R.; Watson, D.M.; Monckton, P.W. Alopecia areata and cataract. Arch. Dermatol. 1966, 93, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosti, A.; Colombati, S.; Caponeri, G.M.; Ciliberti, C.; Tosti, G.; Bosi, M.; Veronesi, S. Ocular abnormalities occurring with alopecia areata. Dermatologica 1985, 170, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orecchia, G.; Bianchi, P.E.; Malvezzi, F.; Stringa, M.; Mele, F.; Douville, H. Lens changes in alopecia areata. Dermatologica 1988, 176, 308–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, T.; Öztekin, A. Choroidal thickness in patients with alopecia areata: Is it a sign for poor prognosis? J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 5098–5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, B.; Aksoy Aydemir, G.; Duzayak, S.; Kızıltoprak, H. Evaluation of retinal layers and choroidal structures using optical coherence tomography in alopecia areata. Medeni. Med. J. 2023, 38, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, C.L.; Grimes, P.E.; Chakrabarti, S.; Minus, H.R.; Kenney, J.A. Retinitis pigmentosa associated with hearing loss, thyroid disease, vitiligo, and alopecia areata: Retinitis pigmentosa and vitiligo. Retina 1982, 2, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Randhawa, S. Hemorrhagic ischemic retinal vasculitis and alopecia areata as a manifestation of HLA-B27. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retin. 2018, 49, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, H.-C.; Ma, S.-H.; Tai, Y.-H.; Dai, Y.-X.; Chang, Y.-T.; Chen, T.-J.; Chen, M.-H. Association between alopecia areata and retinal diseases: A nationwide population-based cohort study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 87, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, P.A. Doubling of the papilla. Acta Ophthalmol. 1969, 47, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoepf, M.; Laby, D.M. Optic neuropathy in a child with alopecia. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2010, 87, E787–E789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierro-Arias, L.; De la Fuente-García, V.; Cortés-Rodrigo, M.D.; Baños-Segura, C.; Ponce-Olivera, R.M. Alteraciones oculares en pacientes con diagnóstico de alopecia areata. Dermatol. Rev. Mex. 2016, 60, 203–209. Available online: https://dermatologiarevistamexicana.org.mx/article/alteraciones-oculares-en-pacientes-con-diagnostico-de-alopecia-areata/ (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Nilofar, F.; Mohanasundaram, K.; Kumar, M.; T, G. Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome as the initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus. Cureus 2024, 16, e61692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Jia, X.; Xiao, X.; Li, S.; Long, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Q. An early diagnostic clue for COL18A1- and LAMA1-associated diseases: High myopia with alopecia areata in the cranial midline. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 644947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofny, E.R.M.; Omar, A.F.; Megeed, W.M.A.; Mahran, A.M. Ocular comorbidities and its relation to clinical and dermoscopic features in patients with alopecia areata: A case-control study. J. Egypt. Women’s Dermatol. Soc. 2024, 21, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophthalmology, A.A.O. History taking. In Practical Ophthalmology: A Manual for Beginning Residents, 8th ed; American Academy of Ophthalmology: St. Francisco, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, K.; Bourque, L.B.; Hays, R.D. Development and evaluation of a measure of patient-reported symptoms of blepharitis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korb, D.R.; Herman, J.P.; Greiner, J.V.; Scaffidi, R.C.; Finnemore, V.M.; Exford, J.M.; Blackie, C.A.; Douglass, T. Lid wiper epitheliopathy and dry eye symptoms. Eye Contact Lens 2005, 31, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traipe, L.; Gauro, F.; Goya, M.C.; Cartes, C.; López, D.; Salinas, D.; Cabezas, M.; Zapata, C.; Flores, P.; Matus, G.; et al. [Validation of the Ocular Surface Disease Index Questionnaire for Chilean patients]. Rev. Med. Chil. 2020, 148, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.J.; Lundy, D.C. Ocular manifestations of autoimmune disease. Am. Fam. Physician 2002, 66, 991–998. [Google Scholar]

- Gueudry, J.; Muraine, M. Anterior uveitis. J. Fr. Ophtalmol. 2018, 41, e11–e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feltgen, N.; Walter, P. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment—An ophthalmologic emergency. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2014, 111, 12–21, quiz 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, D.S.; Larsen, D.; Nattis, A.S. Primary care approach to eye conditions. Osteopath. Fam. Physician 2019, 11, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilha, V.L. Age and disease-related structural changes in the retinal pigment epithelium. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2008, 2, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparrow, J.R.; Hicks, D.; Hamel, C.P. The retinal pigment epithelium in health and disease. Curr. Mol. Med. 2010, 10, 802–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, E.; Jagdeo, J. Patient-Reported Outcomes in dermatology research and practice. G. Ital. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 154, 106–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvert, M.; Kyte, D.; Mercieca-Bebber, R.; Slade, A.; Chan, A.-W.; King, M.T.; The SPIRIT-PRO Group; Hunn, A.; Bottomley, A.; Regnault, A.; et al. Guidelines for inclusion of Patient-Reported Outcomes in clinical trial protocols: The SPIRIT-PRO extension. Jpn. Automob. Manuf. Assoc. 2018, 319, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattinson, R.L.; Trialonis-Suthakharan, N.; Gupta, S.; Henry, A.L.; Lavallée, J.F.; Otten, M.; Pickles, T.; Courtier, N.; Austin, J.; Janus, C.; et al. Patient-Reported Outcome measures in dermatology: A systematic review. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2021, 101, adv00559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, A.M.; Chen, S.C.; Chren, M.-M.; Ferris, L.K.; Edwards, L.D.; Swerlick, R.A.; Flint, N.D.; Cizik, A.M.; Hess, R.; Kean, J.; et al. Patient-Reported Outcome measures and their clinical applications in dermatology. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2023, 24, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darchini-Maragheh, E.; Moussa, A.; Yoong, N.; Bokhari, L.; Jones, L.; Sinclair, R. Alopecia areata-specific Patient-Reported Oucome Measures: A systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2025, 161, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrwich, K.W.; Winnette, R.; Bender, R.; Gandhi, K.; Williams, N.; Harris, N.; Nelson, L. Validation of the Alopecia Areata Patient Priority Outcomes (AAPPO) questionnaire in adults and adolescents with alopecia areata. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, T.R.; Osei, J.; Duvic, M. The utility and validity of the Alopecia Areata Symptom Impact Scale in measuring disease-related symptoms and their effect on functioning. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2018, 19, S41–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrwich, K.W.; Kitchen, H.; Knight, S.; Aldhouse, N.V.J.; Macey, J.; Nunes, F.P.; Dutronc, Y.; Mesinkovska, N.; Ko, J.M.; King, B.A. Development of Clinician-Reported Outcome (ClinRO) and Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) measures for eyebrow, eyelash and nail assessment in alopecia areata. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2020, 21, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, J.; Kitchen, H.; Aldhouse, N.V.J.; Edson-Heredia, E.; Burge, R.; Prakash, A.; King, B.A.; Mesinkovska, N. A Qualitative interview study to explore adolescents’ experience of alopecia areata and the content validity of sign/symptom Patient-Reported Outcome measures. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022, 186, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, J.; Kitchen, H.; Aldhouse, N.V.J.; Burge, R.T.; Edson-Heredia, E.; McCollam, J.S.; Isaka, Y.; Torisu-Itakura, H. Dermatologist and patient perceptions of treatment success in alopecia areata and evaluation of clinical outcome assessments in Japan. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 11, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.; Downie, L.E.; Korb, D.; Benitez-Del-Castillo, J.M.; Dana, R.; Deng, S.X.; Dong, P.N.; Geerling, G.; Hida, R.Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. TFOS DEWS II management and therapy report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 575–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messmer, E.M. The pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of dry eye disease. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2015, 112, 71–81, quiz 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, M.; Fonseca, E.C.; Alves, M.F.; Malki, L.T.; Arruda, G.V.; Reinach, P.S.; Rocha, E.M. Dry eye disease treatment: A systematic review of published trials and a critical appraisal of therapeutic strategies. Ocul. Surf. 2013, 11, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, A.; Bozkurt, B.; Silva, D.; Mortz, C.G.; Baudouin, C.; Atanaskovic-Markovic, M.; Sharma, V.; Doan, S.; Agarwal, S.; Pérez-Formigo, D.; et al. Drug-induced periocular and ocular surface disorders: An EAACI position paper. Allergy 2025, 80, 2953–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).