Abstract

Background: Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease that substantially impairs health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Comorbid mental health conditions, particularly depression and anxiety, may further exacerbate this burden, yet evidence from large, population-based studies remains limited. Therefore, this study examined the association between comorbid depression and anxiety and HRQoL among adults with RA using nationally representative data from the United States. Methods: Data were drawn from the 2017–2022 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Adults aged ≥18 years with self-reported RA were included. HRQoL was assessed using the Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-12) physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) component summary scores. Multiple linear regression models were used to evaluate associations between depression, anxiety, and HRQoL, adjusting for sociodemographic, behavioral, and health-related covariates. Results: Comorbid depression and anxiety were significantly associated with lower HRQoL scores compared with RA alone. Participants with both conditions exhibited the poorest PCS and MCS scores, indicating a disease burden. Lower income, unemployment, and limited physical activity were also linked to poorer HRQoL, whereas better self-rated health and physical activity were positive predictors. Conclusions: Depression and anxiety independently and jointly contribute to poorer HRQoL among adults with RA, even after controlling for key confounders. These findings highlight the importance of integrated care models that address both psychological and physical health, alongside interventions promoting physical activity to enhance overall well-being.

1. Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disease that primarily affects the joints, leading to inflammation, pain, stiffness, and progressive disability [1]. It has also been defined as synovitis in at least one joint with no better alternative diagnosis and a scoring ≥ 6 (out of 10) across involved joints, serologic markers, acute-phase response and symptom duration, under the ICD-11-CM codes [2]. RA affects approximately 0.5% to 1% of the global population and occurs more frequently in women than in men [3,4]. RA represents a major cause of morbidity among adults worldwide, resulting in substantial physical, psychological, and social burden throughout the life course [5]. The chronic pain and fatigue characteristic of RA, combined with its unpredictable flares and potential for irreversible joint damage, can severely impair functional capacity and emotional well-being [6]. Moreover, RA contributes significantly to humanistic and economic burden through reduced productivity, work disability, diminished quality of life, and increased healthcare costs and utilization [7,8].

Beyond physical disability, RA is strongly associated with psychological comorbidities, particularly depression and anxiety, and the links between depression and RA appear to be bidirectional [9]. Previous studies have demonstrated that between 13% and 47% of individuals with RA experience depressive symptoms [10]. These mental health conditions not only exacerbate physical symptoms but also influence treatment adherence, perception of pain, and overall disease progression [10]. Depression and anxiety are also linked to disability, reduced work productivity, higher healthcare utilization and costs, and increased mortality among RA patients [11,12,13,14,15]. Consequently, assessing HRQoL in the context of mental health comorbidities is vital to understanding the full burden of RA.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) refers to “how well a person functions in their life and his or her perceived well-being in physical, mental, and social domains of health” [16]. In rheumatoid arthritis, HRQoL is a key outcome measure that reflects the broader impact of the disease beyond clinical symptoms or laboratory markers. Previous research has consistently demonstrated that poor mental health, particularly depression and anxiety, is strongly associated with reduced HRQoL among individuals with RA [15,17,18,19,20]. Multiple interrelated factors contribute to impaired HRQoL in this population, including chronic pain, disease severity, fatigue, and functional disability, all of which can exacerbate psychological distress and diminish overall well-being [20,21,22,23]. Furthermore, lower HRQoL has been linked to increased healthcare utilization, higher medical costs, and greater dependence on health services [24].

Despite growing recognition of the importance of HRQoL in RA management, previous studies examining its determinants have been limited by small, non-representative samples, cross-sectional designs, and a lack of control for key confounders. Moreover, most investigations have focused on depression alone, neglecting the frequent coexistence and interactive effects of depression and anxiety on HRQoL [15,17,18,19,20]. The present study aims to address these gaps by utilizing data from the 2017–2022 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), a nationally representative dataset of the U.S. noninstitutionalized population. By employing a large, diverse sample and controlling for multiple sociodemographic, behavioral, and clinical covariates known to influence HRQoL, this study provides a more rigorous and generalizable assessment of the relationship between comorbid depression and anxiety and HRQoL in adults with RA. Generating nationally representative evidence on these interrelationships will enhance understanding of the mental–physical health interface in RA.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data

This study used a retrospective longitudinal design with data drawn from the 2017–2022 cycle of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), a national survey of the U.S. population administered by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS collects information from households across two consecutive years through a stratified, multistage probability sampling framework. Data are gathered in multiple rounds using computer-assisted personal interviews. MEPS provides comprehensive data on demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, chronic health conditions, healthcare use and expenditures, health insurance, income, and employment. Medical conditions including depression and anxiety are self-reported by participants during interviews and then coded into the International Classification of Diseases Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes, the tenth revision, by trained professional coders.

2.2. Study Population

Participants were eligible for inclusion if they were 18 years old and above, had a documented diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, were alive during the study period, and had complete HRQoL data. RA cases were identified in the MEPS dataset using the ICD-10-CM code “M06” (other RA) [25].

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Study Outcome: Health-Related Quality of Life

To assess health-related quality of life (HRQoL), participants in MEPS completed the Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-12©), a widely used and validated patient-reported outcome measure [26,27,28]. The VR-12 captures eight dimensions of health: general health, physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health, bodily pain, vitality, role limitations due to emotional problems, mental health, and social functioning [23]. From these domains, two composite scores are generated: the Physical Component Summary (PCS), which reflects general health, physical functioning, role physical, and bodily pain; and the Mental Component Summary (MCS), which reflects vitality, role emotional, mental health, and social functioning [29].

2.3.2. Independent Variables

The primary independent variable in this study was rheumatoid arthritis (RA) groups, classified into four mutually exclusive groups: RA only, RA with anxiety, RA with depression, and RA with both anxiety and depression. Other independent variables were included based on the existing evidence of their impact on HRQoL in adults with RA. These encompassed sociodemographic factors (age group, gender, education level, household income, employment status, marital status, and region of residence). Health insurance was included as a proxy for healthcare access, which may directly influence HRQoL outcomes. Health behavior, such as physical activity, and self-rated health were also considered. In addition, chronic comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, asthma, COPD, GERD) were accounted for, as they are highly prevalent among individuals with RA and contribute to overall disease burden and diminished quality of life.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the baseline characteristics of RA sample, including frequencies, and percentages. Differences in baseline characteristics across the RA groups were evaluated using bivariate analysis, (chi-square tests). Variations in mean HRQoL scores by RA groups were examined using ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests to determine which specific groups differed significantly. To evaluate the association between RA groups and HRQoL, multivariable linear regression model was conducted, adjusting for all relevant covariates. All estimations accounted for the complex survey design of MEPS, incorporating variance adjustment weights (strata and primary sampling unit) along with person-level weights. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Rheumatoid Arthritis Sample

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study sample (n = 2324), and stratified by RA with and without comorbid depression and anxiety. Overall, 69.6% of participants had RA only, while 11.8% had RA with depression, 10.7% had RA with anxiety, and 7.9% had RA with both depression and anxiety. Age was significantly associated with RA groups (p < 0.001), with younger adults (22–39 years) more likely to present with depression and/or anxiety, compared to older adults (>64 years). Women were overrepresented in the RA with depression and/or anxiety groups compared with men (p < 0.001). Regional variation was observed (p = 0.013), with participants from the Northeast more likely to have RA with depression and/or anxiety compared to other regions. Socioeconomic characteristics were also associated with RA groups. Employment status (p = 0.021) and poverty status (p = 0.022) showed significant relationships, as unemployed and poor participants were more likely to have RA with depression and/or anxiety compared to those employed or with high income. Insurance coverage was also important: participants with public insurance had higher rates of RA with depression/anxiety compared to those private insurance (p = 0.013). Poorer general health was strongly associated with comorbid depression and/or anxiety (p < 0.001); nearly 40% of those reporting fair or poor health were in these groups. Similarly, physical activity was significant (p = 0.001), with those not exercising more likely to have RA with depression. Several comorbid conditions were significantly associated with RA with depression and/or anxiety. These included asthma (p = 0.001), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (p < 0.001), osteoarthritis (p = 0.002), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Description of the Study Sample (n = 2324), Number and weighted Row Percentage of Baseline Characteristics by Rheumatoid Arthritis Groups.

Overall, effect size estimates indicated that most associations between rheumatoid arthritis group status and demographic, socioeconomic, and health-related characteristics were of small to moderate magnitude, suggesting meaningful but not large differences across groups (Supplementary Materials, Table S1).

3.2. Health-Related Quality of Life and Rheumatoid Arthritis Groups

Table 2 displays the weighted means and standard errors of HRQoL scores by RA groups. Both the physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores differed significantly across groups (p < 0.0001). Participants with RA only had the highest mean PCS (38.53, SE = 0.46) compared to those with RA and comorbid conditions, while those with RA, depression, and anxiety had the lowest mean PCS (33.99, SE = 1.26). A similar gradient was observed for MCS. The RA-only group reported the highest MCS score (51.15, SE = 0.33), followed by those with RA and anxiety (43.85, SE = 0.92), RA and depression (42.74, SE = 1.05), and the lowest among participants with RA, depression, and anxiety (38.55, SE = 1.01).

Table 2.

Weighted Means and Standard Errors of HRQoL Scores by Rheumatoid Arthritis Groups.

The one-way ANOVA effect size results indicate that RA groups had a significant effect on both PCS and MCS (Supplementary Materials, Table S2). The effect of RA group on PCS was statistically significant (F(3, 2320) = 15.79, p < 0.0001), but the effect size was small (partial η2 = 0.0199; ω2 = 0.0189). This suggests that while there are measurable differences in physical health across the groups, RA comorbidity status explains only about 2% of the variance in PCS scores. The effect of RA group on MCS was highly significant (F(3, 2320) = 164.22, p < 0.0001), with a large effect size (partial η2 = 0.175; ω2 = 0.175). This indicates that RA comorbidity status explains approximately 17.5% of the variance in mental QoL scores, reflecting a substantial impact of depression and/or anxiety on mental well-being among RA patient conditions (Supplementary Materials, Table S2). Post hoc results indicate that comorbid depression and anxiety were associated with substantial reductions in both PCS and MCS among individuals with RA, with the greatest decline observed in those reporting both conditions (Supplementary Materials, Table S3).

3.3. Health-Related Quality of Life Among Rheumatoid Arthritis Groups from Linear Regression Analysis

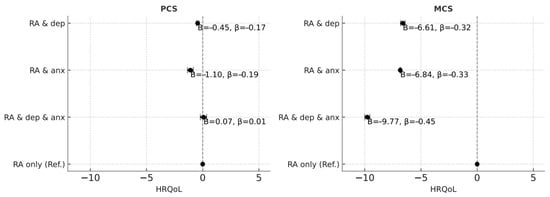

Table 3 presents the adjusted multivariable linear regression estimates for predictors of HRQoL among adults with RA. Significant differences were observed across RA subgroups. Compared to participants with RA only, those with RA and depression, RA and anxiety, and RA with both depression and anxiety had significantly lower MCS scores (B = −6.61, −6.84, and −9.77, respectively; all p < 0.001). For the PCS, RA with depression (B = −0.45, p < 0.001) and RA with anxiety (B = −1.10, p < 0.001) were associated with lower scores, whereas RA with both depression and anxiety did not significantly differ from RA only. Figure 1 illustrates the forest plot of adjusted regression coefficients of RA groups on HRQoL.

Table 3.

Factors Related to Physical and Mental HRQoL among Adults with Rheumatoid Arthritis from Adjusted Multivariate Linear Regressions Analysis.

Figure 1.

Forest plot of adjusted regression coefficients of RA groups on HRQoL.

Age, gender, race/ethnicity, and marital status were also significant predictors of HRQoL. Younger adults (22–39 years) had higher PCS scores but lower MCS scores compared with older adults (>65 years) (p < 0.001). Men reported slightly better PCS (B = 0.20, p < 0.05) and MCS (B = 0.09, p < 0.001) scores compared with women. African American, Latino, and “other” race groups all showed higher PCS scores relative to Whites, but MCS scores varied, with Latinos (B = −0.67, p < 0.001) and “others” (B = −2.04, p < 0.001) reporting significantly lower MCS. Married participants reported better MCS scores compared with never-married adults.

Socioeconomic status and access to resources were strongly associated with HRQoL. Employment was linked with substantially higher PCS (B = 4.44, p < 0.001) and MCS (B = 0.94, p < 0.001). Compared to high-income participants, those who were poor, near-poor, or middle-income reported significantly lower PCS and MCS scores (all p < 0.001). Prescription drug insurance was associated with lower PCS (B = −1.32, p < 0.001) and MCS (B = −2.14, p < 0.001). Regional differences were also noted: residents of the Midwest had higher PCS and MCS scores compared with those in the West, while those in the South reported lower PCS.

Health and lifestyle factors contributed strongly to HRQoL. Better self-rated general health was associated with higher PCS and MCS, with excellent/very good health yielding the largest positive associations (PCS: B = 12.32; MCS: B = 5.12; p < 0.001). Engaging in physical activity at least three times per week was associated with better PCS (B = 3.44, p < 0.001) and MCS (B = 1.25, p < 0.001). Several comorbidities were linked to lower HRQoL. Heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, asthma, COPD, and GERD all negatively predicted PCS. Similarly, diabetes, asthma, GERD, and cancer were linked with lower MCS. Effect sized results are shown in (Supplementary Materials, Table S4), the regression analyses revealed that depression and anxiety remained significant predictors of lower physical and mental HRQoL even after adjusting for sociodemographic and clinical covariates. The overall model fit corresponded to large effect sizes (Cohen’s f2 = 0.70 for the PCS and f2 = 0.46 for the MCS), suggesting that the predictors accounted for a meaningful proportion of variability in HRQoL outcomes. These results underscore the substantial practical impact of psychological comorbidities on perceived health among adults with rheumatoid arthritis.

4. Discussion

This study extends previous research by quantifying the magnitude and clinical relevance of comorbid depression and anxiety on HRQoL among adults with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) using nationally representative data. While prior studies have demonstrated that these mental health conditions worsen HRQoL, the present analysis is among the first to incorporate formal effect size measures, providing insight into the clinical significance of these associations beyond statistical significance alone. The results indicate that comorbid depression and anxiety exert a large and meaningful impact on mental HRQoL, explaining approximately 17% of the variance in mental component scores, whereas their effect on physical functioning is smaller but still significant. The large effect sizes observed in the multivariate models further demonstrate that psychosocial, demographic, and health-related variables collectively account for a substantial proportion of HRQoL variability. By jointly examining depression and anxiety rather than treating them as isolated factors, this study highlights the compounding burden of mental health comorbidities, particularly when coupled with socioeconomic disadvantage and limited physical activity, underscoring the multifactorial nature of well-being among individuals with RA.

Our results align with prior research conducted in diverse settings, which consistently show that psychiatric comorbidities impart the quality of life in RA [15,17,18,19,20]. Our findings corroborate this evidence and extend it to a broader U.S. adult population, highlighting the population-level implications of comorbid mental illness in RA. Importantly, our results highlight the compounded effect of coexisting depression and anxiety. Participants with both conditions exhibited the lowest HRQoL scores particularly in the mental health domain, suggesting a synergistic rather than additive burden. This observation aligns with previous evidence that depression and anxiety often co-occur in chronic illnesses and interact to amplify symptom perception, fatigue, and functional limitations. Such comorbidity may also hinder treatment adherence and self-management, further compromising long-term outcomes.

Beyond mental health, this study reinforces the substantial influence of social and behavioral determinants on HRQoL. Lower income, unemployment, and public insurance coverage were all associated with poorer HRQoL, reflecting the socioeconomic disparities that shape both disease experience and access to care. These findings echo prior research indicating that patients with limited financial resources face greater functional impairment and reduced treatment satisfaction.

Consistent with a recent systematic review that examined 21 studies and identified 70 determinants of HRQoL in RA, our results emphasize the multifactorial nature of quality of life in this population [30]. That review classified determinants into sociodemographic, RA-related, comorbidity, behavioral, and psychosocial domains, and found that poorer physical function, and the presence of comorbidities were consistently associated with reduced HRQoL. Among behavioral factors, exercise and sleep were the only determinants significantly linked to better HRQoL, while anxiety and depression emerged as the most prominent psychosocial factors predicting poorer HRQoL. Our findings reinforce and extend this evidence, showing that comorbid depression and anxiety remain significant predictors of diminished HRQoL even after controlling for these broader determinants.

Importantly, the identification of exercise as a key behavioral determinant of better HRQoL is supported by growing interventional evidence. A comprehensive synthesis of systematic reviews and meta-analyses has demonstrated that aerobic and structured exercise training are both safe and effective for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, leading to significant improvements in functional capacity, aerobic fitness, pain reduction, fatigue, vitality, psychological well-being, and overall HRQoL [31,32]. These findings collectively suggest that promoting physical activity alongside psychological support may represent an integrated, patient-centered approach to improving both physical and mental health outcomes in RA.

4.1. Study Strengths and Limitations

The present study makes several important contributions to the existing literature. First, it is among the few analyses to jointly examine depression and anxiety in relation to HRQoL in RA using a large, nationally representative U.S. sample. Second, the use of a validated HRQoL instrument (VR-12) and rigorous adjustment for multiple confounders enhances the validity and generalizability of the findings. Third, by quantifying the differential impact of comorbid mental health conditions, this research provides actionable insights for clinicians and policymakers to prioritize integrated care approaches that address both physical and psychological dimensions of RA. In addition, the present study advances the field by quantifying and interpreting effect size measures, an important step toward enhancing the interpretability and clinical relevance of statistical findings. However, certain limitations should be acknowledged. MEPS lacked data on RA disease duration, severity, treatment regimen, and disease activity measures, all of which are important determinants of quality of life in RA patients. The absence of these variables may have introduced unmeasured confounding. In addition, self-reported HRQoL may also be subject to recall or reporting bias.

4.2. Clinical, Public Health, and Research Implications

From a clinical perspective, these results of high mental health prevalence and impact HRQoL in Ra population highlight the importance of integrating mental health assessment into standard RA care pathways. Routine screening and timely referral to psychological services could improve disease management and overall quality of life. On a public health level, programs that promote physical activity can help alleviate the humanistic burden of RA. Future research should explore longitudinal relationships between disease activity, psychological distress, and HRQoL. Additionally, intervention studies that measure changes in effect sizes over time can help determine the real-world clinical impact of integrating mental health support into RA treatment protocols.

5. Conclusions

This nationally representative study demonstrates that comorbid depression and anxiety are strongly associated with poorer HRQoL among adults with rheumatoid arthritis, even after adjusting for key sociodemographic and clinical factors. The combined burden of these mental health conditions highlights the need for integrated management approaches that address both physical and psychological aspects of care. Additionally, socioeconomic disadvantage and low physical activity further contribute to reduced well-being, emphasizing the role of social and behavioral determinants. Interventions focused on mental health support and lifestyle modification may improve overall quality of life and should be prioritized in comprehensive rheumatoid arthritis care.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm14227940/s1, Table S1: Characteristics of the Study Sample, Number and Row Percentage of Characteristics by Rheumatoid Arthritis Groups; Table S2: Weighted Means and Standard Error Health-related Quality of Life Scores by Rheumatoid Arthritis Groups; Table S3: Tukey’s HSD Post Hoc Results; Table S4: Intercept and Parameter Estimates from Adjusted Multivariate Linear Regressions on HRQoL among Adults with Rheumatoid Arthritis.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ongoing Research Funding Program, (ORF-2025-1128), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No ethical approval was needed as we have utilized a public data available, the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) database.

Informed Consent Statement

MEPS database is a publicly available secondary data; therefore, patient consent was not required for this research.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study is available from the MEPS database at this URL: https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data_files.jsp (accessed on 15 September 2025).

Acknowledgments

We extend our appreciation to the Ongoing Research Funding Program, (ORF-2025-1128), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The author affirms that there are no conflicts of interest related to the publication of this paper.

References

- Smith, M.H.; Berman, J.R. What is rheumatoid arthritis? JAMA 2022, 327, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, J.; Upchurch, K.S. ACR/EULAR 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria. Rheumatology 2012, 51, vi5–vi9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, K.; Nossent, J.; Preen, D.; Keen, H.; Inderjeeth, C. The global prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis based on a systematic review. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 863–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, S.E. The Epidemiology of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 27, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlig, T.; Moe, R.H.; Kvien, T.K. The Burden of Disease in Rheumatoid Arthritis. PharmacoEconomics 2014, 32, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergne-Salle, P.; Pouplin, S.; Trouvin, A.P.; Bera-Louville, A.; Soubrier, M.; Richez, C.; Javier, R.M.; Perrot, S.; Bertin, P. The burden of pain in rheumatoid arthritis: Impact of disease activity and psychological factors. Eur. J. Pain 2020, 24, 1979–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Agarwal, S.K. Economic and Humanistic Burden of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Results from the US National Survey Data 2018–2020. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2024, 6, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.C.; Moore, A.; Vasilescu, R.; Alvir, J.; Tarallo, M. A structured literature review of the burden of illness and unmet needs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A current perspective. Rheumatol. Int. 2016, 36, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gettings, L. Psychological well-being in rheumatoid arthritis: A review of the literature. Musculoskelet. Care 2010, 8, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakra, E.; Marotte, H. Rheumatoid arthritis and depression. Jt. Bone Spine 2021, 88, 105200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Khubchandani, J.; Noonan, L.; Batra, K.; Pai, A.; Schwab, M. Risk of mortality among people with rheumatoid arthritis and depression. Egypt. Rheumatol. 2024, 46, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchon, C.A.; Walld, R.; Peschken, C.A.; Bernstein, C.N.; Bolton, J.M.; El-Gabalawy, R.; Fisk, J.D.; Katz, A.; Lix, L.M.; Marriott, J.; et al. Impact of Psychiatric Comorbidity on Health Care Use in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Population-Based Study. Arthritis Care Res. 2021, 73, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.M.; Lan, J.L.; Huang, W.L.; Wu, C.S. Estimation of life expectancy and healthcare cost in rheumatoid arthritis patients with and without depression: A population-based retrospective cohort study. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1221393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, S.; Piercy, J.; Blackburn, S.; Sullivan, E.; Karyekar, C.S.; Li, N. The multifaceted impact of anxiety and depression on patients with rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Rheumatol. 2019, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, A.; Dwibedi, N.; LeMasters, T.; Hornsby, J.A.; Wei, W.; Sambamoorthi, U. Burden of Depression among Working-Age Adults with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis 2018, 2018, 8463632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Brazier, J. Health, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Quality of Life: What is the Difference? PharmacoEconomics 2016, 34, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tański, W.; Szalonka, A.; Tomasiewicz, B. Quality of Life and Depression in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Treated with Biologics—A Single Centre Experience. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiRenzo, D.D.; Craig, E.T.; Bingham Iii, C.O.; Bartlett, S.J. Anxiety impacts rheumatoid arthritis symptoms and health-related quality of life even at low levels. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2020, 38, 1176–1181. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Al-Fadl, E.M.; Ismail, M.A.; Thabit, M.; El-Serogy, Y. Assessment of health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Egypt. Rheumatol. 2014, 36, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Katchamart, W.; Narongroeknawin, P.; Chanapai, W.; Thaweeratthakul, P. Health-related quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Rheumatol. 2019, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.W.; He, H.-G.; Mak, A.; Lahiri, M.; Luo, N.; Cheung, P.P.; Wang, W. Health-related quality of life and its predictors among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2016, 30, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroon, N.; Aggarwal, A.; Lawrence, A.; Agarwal, V.; Misra, R. Impact of rheumatoid arthritis on quality of life. Mod. Rheumatol. 2007, 17, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alishiri, G.H.; Bayat, N.; Salimzadeh, A.; Salari, A.; Hosseini, S.M.; Rahimzadeh, S.; Assari, S. Health-related quality of life and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2011, 16, 897–903. [Google Scholar]

- Ethgen, O.; Kahler, K.H.; Kong, S.X.; Reginster, J.-Y.; Wolfe, F. The effect of health related quality of life on reported use of health care resources in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: A longitudinal analysis. J. Rheumatol. 2002, 29, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey HC-231: 2021 Medical Conditions File. 2023. Available online: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h231/h231doc.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Maslak, J.P.; Jenkins, T.J.; Weiner, J.A.; Kannan, A.S.; Patoli, D.M.; McCarthy, M.H.; Hsu, W.K.; Patel, A.A. Burden of Sciatica on US Medicare Recipients. JAAOS—J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2020, 28, e433–e439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, A.J.; Rothendler, J.A.; Qian, S.X.; Bailey, H.M.; Kazis, L.E. The History and Applications of the Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-12). J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2022, 45, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazis, L.E.; Rogers, W.H.; Rothendler, J.; Qian, S.; Selim, A.; Edelen, M.O.; Stucky, B.D.; Rose, A.J.; Butcher, E. Outcome Performance Measure Development for Persons with Multiple Chronic Conditions; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cheak-Zamora, N.C.; Wyrwich, K.W.; McBride, T.D. Reliability and validity of the SF-12v2 in the medical expenditure panel survey. Qual. Life Res. 2009, 18, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, N.; Moolooghy, K.; Kopec, J.; Xie, H.; Khan, K.M.; Lacaille, D. Determinants of health-related quality of life in adults living with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2025, 73, 152717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athanasiou, A.; Papazachou, O.; Rovina, N.; Nanas, S.; Dimopoulos, S.; Kourek, C. The Effects of Exercise Training on Functional Capacity and Quality of Life in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Weng, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, Q.; Xu, G. Effectiveness and safety of aerobic exercise for rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).