Rectus Abdominis Fascia Plication Within DIEP Flap Breast Reconstruction: Impact on Abdominal Wall Morbidity and Patient Satisfaction Evaluated with the BREAST-Q

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DIEP | Deep inferior epigastric artery perforator |

| PAP | Profunda artery perforator |

| TRAM | Transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous |

References

- Woolston, C. Breast cancer. Nature 2015, 527, S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkhorst, K.; Castanov, V.; Li, E.A.; Farrokhi, K.; Jaszkul, K.M.; AlGhanim, K.; DeLyzer, T.; Simpson, A.M. Alternatives to the Gold Standard: A Systematic Review of Profunda Artery Perforator and Lumbar Artery Perforator Flaps for Breast Reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2024, 92, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Mota, P.G.F.; Pascoal, A.G.B.A.; Carita, A.I.A.D.; Bø, K. Prevalence and risk factors of diastasis recti abdominis from late pregnancy to 6 months postpartum, and relationship with lumbo-pelvic pain. Man. Ther. 2015, 20, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radhakrishnan, M.; Ramamurthy, K. Efficacy and Challenges in the Treatment of Diastasis Recti Abdominis-A Scoping Review on the Current Trends and Future Perspectives. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, B.; Salzillo, R.; Tenna, S.; Cagli, B.; Coppola, M.M.; Petrucci, V.; Camilloni, C.; Zhang, Y.X.; Persichetti, P. Total autologous breast reconstruction with the Kiss Latissimus Dorsi Flap. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic. Surg. JPRAS 2022, 75, 3673–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozen, W.M.; Ashton, M.W.; Kiil, B.J.; Grinsell, D.; Seneviratne, S.; Corlett, R.J.; Taylor, G.I. Avoiding denervation of rectus abdominis in DIEP flap harvest II: An intraoperative assessment of the nerves to rectus. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2008, 122, 1321–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.; Salingaros, S.; Wright, M.A.; Black, G.G.; Otterburn, D.M. Complications After Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator Flap Breast Reconstruction for Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy: A Series of 380 Flaps. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2025, 94 (Suppl. S4), S283–S290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, D.P.; Plonczak, A.M.; Reissis, D.; Henry, F.P.; Hunter, J.E.; Wood, S.H.; Jallali, N. Factors that predict deep inferior epigastric perforator flap donor site hernia and bulge. J. Plast. Surg. Hand Surg. 2018, 52, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortada, H.; AlNojaidi, T.F.; AlRabah, R.; Almohammadi, Y.; AlKhashan, R.; Aljaaly, H. Morbidity of the Donor Site and Complication Rates of Breast Reconstruction with Autologous Abdominal Flaps: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Breast J. 2022, 2022, 7857158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Murariu, D.; Chen, B.; Bailey, E.; Nelson, W.; Fortunato, R.; Nosik, S.; Moreira, A. Transabdominal Robotic Harvest of Bilateral DIEP Pedicles in Breast Reconstruction: Technique and Interdisciplinary Approach. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2024, 41, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrickson, S.A.; Dusseldorp, J.R. The Medial Paramuscular Approach to DIEP Flap Pedicle Dissection: Incorporating Rectus Diastasis Repair into Routine Donor-Site Closure. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2025, 156, 481e–484e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmeshwar, N.; Lem, M.; Dugan, C.L.; Piper, M. Evaluating mesh use for abdominal donor site closure after deep inferior epigastric perforator flap breast reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Microsurgery 2023, 43, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, L.; Kim, P.; Dunn, E.; Churchill, I.; Yuan, M.; Avram, R.; McRae, M.; Thoma, A.; Coroneos, C.J.; Voineskos, S.H. Closed-Incision Negative Pressure Therapy Compared to Conventional Dressing Following Autologous Abdominal Tissue Breast Reconstruction: The MACVAC Pilot Randomized Control Trial. Plast. Surg. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Phuyal, D.; Mordukhovich, I.; Gaston, J.; Rios-Diaz, A.J.; Darras, O.; Obeid, R.; Djohan, R.; Schwarz, G.; Gurunian, R.; Bishop, S.N. Optimizing Donor Site Morbidity in DIEP Flap Reconstruction: Advancements in Minimizing Anterior Fascial Defects: A Systematic Review. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucher, F.; Tamulevicius, M.; Dastagir, N.; Milewski, M.; Dietz, L.J.; Vogt, P.M.; Dastagir, K. Comparing Minimally Invasive and Conventional Approaches to DIEP Flap Harvest: A Matched-Pair Analysis from a High-Volume Center. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santanelli Di Pompeo, F.; Barone, M.; Salzillo, R.; Cogliandro, A.; Brunetti, B.; Ciarrocchi, S.; Alessandri Bonetti, M.; Tenna, S.; Sorotos, M.; Persichetti, P. Predictive Factors of Satisfaction Following Breast Reconstruction: Do they Influence Patients? Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2022, 46, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atisha, D.; Alderman, A.K. A systematic review of abdominal wall function following abdominal flaps for postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2009, 63, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenna, S.; Salzillo, R.; Brunetti, B.; Coppola, M.M.; Barone, M.; Cagli, B.; Cogliandro, A.; Franceschi, F.; Persichetti, P. Effects of latissimus dorsi (LD) flap harvest on shoulder function in delayed breast reconstruction. A long-term analysis considering the acromiohumeral interval (AHI), the WOSI, and BREAST-Q questionnaires. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. JPRAS 2020, 73, 1862–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, R.M.; Dickinson, B.P.; Fastekjian, J.H.; Watson, J.P.; DaLio, A.L.; Crisera, C.A. Risk factors for abdominal donor-site morbidity in free flap breast reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2008, 121, 1519–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Kim, S.; Farrokhi, K.; Deng, D.; Laurignano, L.; Box, D.; Grant, A.; Appleton, S.; DeLyzer, T. Donor Site Outcomes Following Autologous Breast Reconstruction with DIEP Flap: A Retrospective and Prospective Study in a Single Institution. Plast. Surg. 2024, 30, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Group 1, Value n = 37 | Group 2, Value n = 25 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 52.2± 9.0 | 50.9 ± 9.9 | 0.6181 |

| BMI | 25.7 ± 5.5 | 23.9 ± 5.6 | 0.1302 |

| Smoking | 13.5% | 16.0% | >0.9999 |

| Previous pregnancies | 94.6% | 96.0% | >0.9999 |

| Previous miscarriages | 21.6% | 20.0% | >0.9999 |

| Previous RT | 70.3% | 76.0% | 0.7736 |

| Timing: delayed | 94.6% | 84.0% | 0.2097 |

| Perforator row: medial | 86.5% | 84.0% | >0.9999 |

| More than one perforator included (always same row) | 35.1% | 32.0% | >0.9999 |

| Insetting: external | 73.0% | 64.0% | 0.5761 |

| Insetting: buried | 27.0% | 36.0% | 0.5761 |

| Preoperative diastasis (cm) | 2.7 ± 1.3 | 4.1 ± 1.7 | 0.0012 * |

| Abdominal bulge | 16.2% | 0% | 0.07268 |

| Total flap loss | 0% | 4.2% | 0.4032 |

| Partial flap loss | 8.1% | 8.0% | >0.9999 |

| Liponecrosis | 8.1% | 4.2% | 0.6418 |

| Abdominal dehiscence | 18.9% | 8.0% | 0.2916 |

| Infection | 16.2% | 4.2% | 0.2254 |

| Group 1 Value | Group 2 Value | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial well-being | 63.0 ± 24.3 | 61.6 ± 18.9 | 0.8354 |

| Sexual well-being | 55.2 ± 20.3 | 49.8 ± 24.4 | 0.4520 |

| Satisfaction with breast | 58.6 ± 21.9 | 57.1 ± 13.7 | 0.7803 |

| Physical well-being: chest | 36.3 ± 26.8 | 32.5 ± 22.0 | 0.7332 |

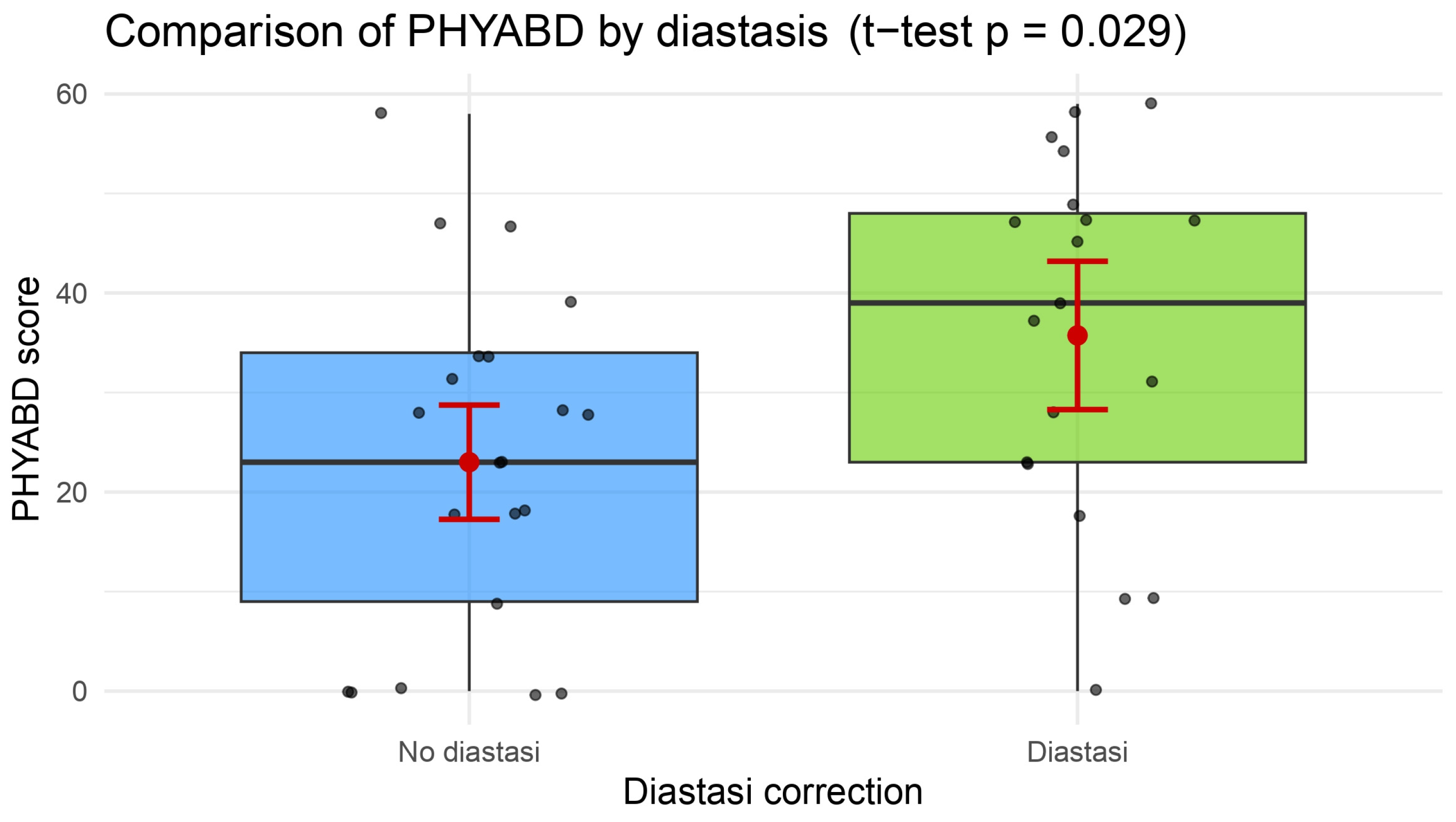

| Physical well-being: abdomen | 23.0 ± 17.2 | 35.7 ± 18.0 | 0.0316 * |

| Satisfaction with surgeon | 90.2± 14.6 | 94.4 ± 8.8 | 0.5124 |

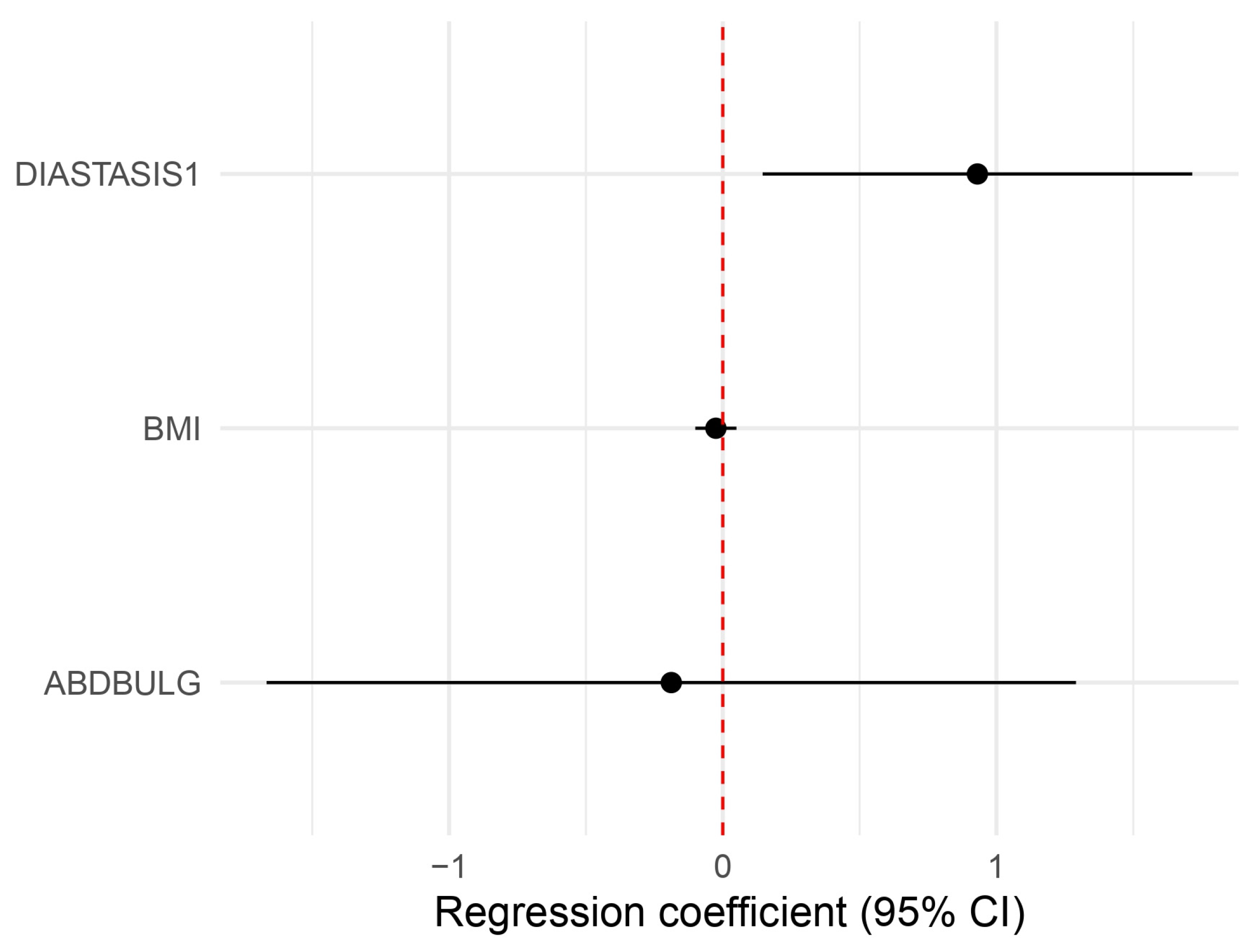

| Physical Well-Being: Abdomen | p | CI | Beta Coef |

| Diastasis plication | 0.02609 | 1.1566914 5.558957 | 2.5357440 * |

| BMI | 0.51578 | 0.9045022 1.051272 | 0.9751298 |

| Abdominal Bulge | 0.80461 | 0.1888424 3.635329 | 0.8285556 |

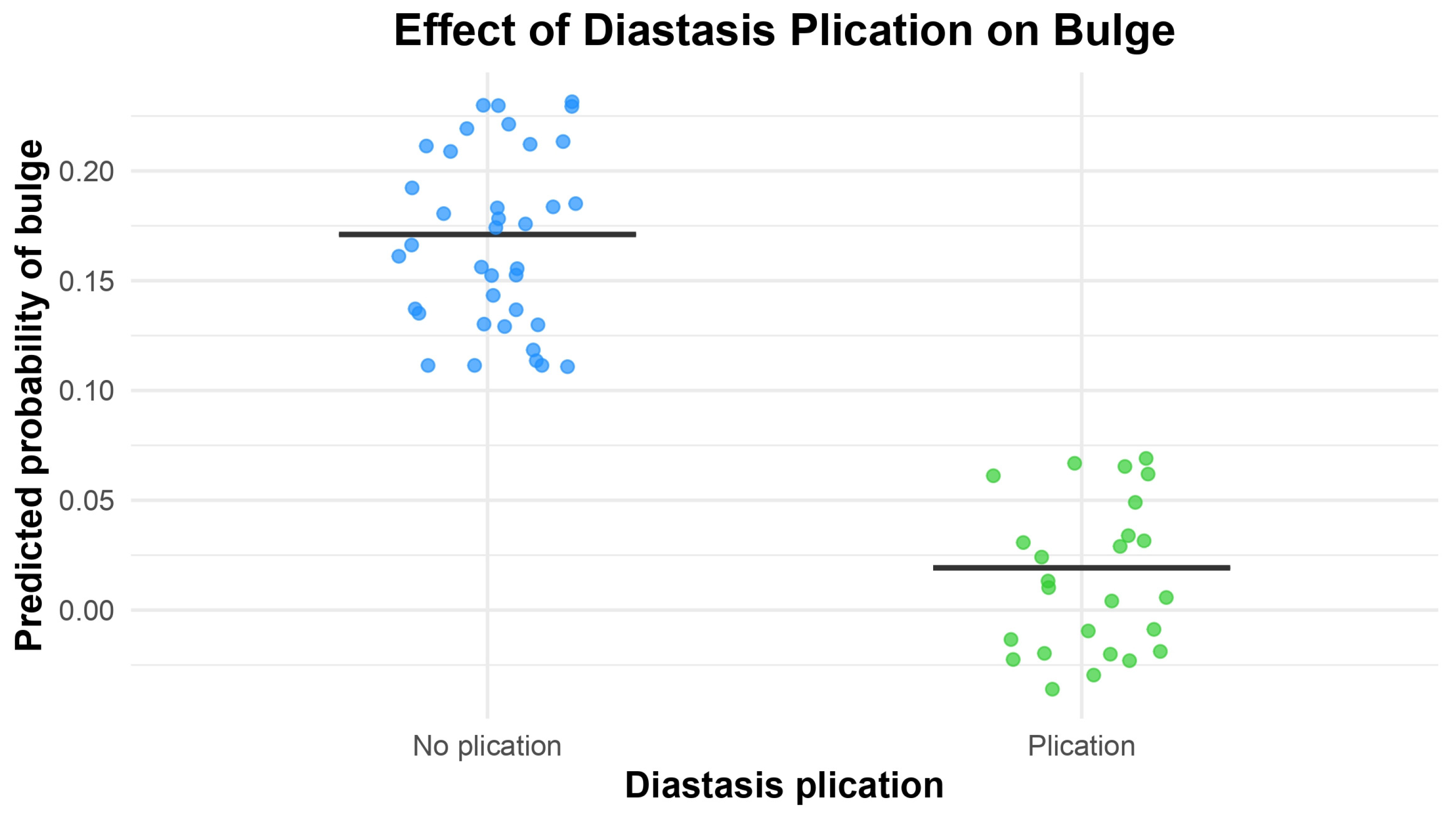

| Abdominal Bulge | p | CI | OR |

| Diastasis plication | 0.03121 | 0.0006948 0.8388511 | 0.0921519 * |

| Number of perforators | 0.86855 | 0.1770843 6.5591235 | 1.1578344 |

| Lateral row | 0.13784 | 0.5982644 29.481968 | 4.3247184 |

| Surgeon 1, Mean ± SD | Surgeon 2, Mean ± SD | p Value | |

| Group 1 | 3.93 ± 0.91 | 3.35 ± 0.90 | 0.112 |

| Group 2 | 3.50 ± 1.10 | 3.62 ± 0.92 | 0.507 |

| Control Group | Study Group | p Value | |

| Surgeon global score | 3.64 ± 0.83 | 3.56 ± 0.96 | 0.550 |

| Spearman’s rank correlation | Rho = 0.716 | p < 0.0001 * | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brunetti, B.; Salzillo, R.; Lombardo, G.A.G.; Camilloni, C.; Pazzaglia, M.; Morelli Coppola, M.; Petrucci, V.; Barone, M.; Tenna, S.; Persichetti, P. Rectus Abdominis Fascia Plication Within DIEP Flap Breast Reconstruction: Impact on Abdominal Wall Morbidity and Patient Satisfaction Evaluated with the BREAST-Q. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7939. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227939

Brunetti B, Salzillo R, Lombardo GAG, Camilloni C, Pazzaglia M, Morelli Coppola M, Petrucci V, Barone M, Tenna S, Persichetti P. Rectus Abdominis Fascia Plication Within DIEP Flap Breast Reconstruction: Impact on Abdominal Wall Morbidity and Patient Satisfaction Evaluated with the BREAST-Q. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):7939. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227939

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrunetti, Beniamino, Rosa Salzillo, Giuseppe A. G. Lombardo, Chiara Camilloni, Matteo Pazzaglia, Marco Morelli Coppola, Valeria Petrucci, Mauro Barone, Stefania Tenna, and Paolo Persichetti. 2025. "Rectus Abdominis Fascia Plication Within DIEP Flap Breast Reconstruction: Impact on Abdominal Wall Morbidity and Patient Satisfaction Evaluated with the BREAST-Q" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 7939. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227939

APA StyleBrunetti, B., Salzillo, R., Lombardo, G. A. G., Camilloni, C., Pazzaglia, M., Morelli Coppola, M., Petrucci, V., Barone, M., Tenna, S., & Persichetti, P. (2025). Rectus Abdominis Fascia Plication Within DIEP Flap Breast Reconstruction: Impact on Abdominal Wall Morbidity and Patient Satisfaction Evaluated with the BREAST-Q. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 7939. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227939